Published online Jan 6, 2026. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v14.i1.114043

Revised: October 20, 2025

Accepted: December 22, 2025

Published online: January 6, 2026

Processing time: 117 Days and 14 Hours

Gallstones and gallbladder wall thickening (GBWT) are frequent findings in patients with cirrhosis, reflecting the critical interplay between hepatobiliary dysfunction and portal hypertension.

To assess the prevalence of gallstones and asymptomatic GBWT in patients with cirrhosis.

Hospitalized patients with cirrhosis who had undergone abdominal imaging stu

A total of 128 patients were included. The patients had a mean age of

This study underlines the high prevalence of radiologic gallbladder findings in patients with cirrhosis while simultaneously serving as a reminder to clinicians to refrain from accrediting these findings to a diagnosis of acute cholecystitis in the absence of symptoms.

Core Tip: Gallbladder pathology is encountered in many patients with cirrhosis. The pathophysiology of such findings is not clearly understood, yet they are significantly correlated with the presence of portal hypertension and decompensated cirrhosis. Furthermore, their clinical impact is relatively small. Clinicians should be able to recognize common gallbladder imaging findings in patients with cirrhosis and avoid misdiagnosing these patients with acute biliary disease.

- Citation: Tsankof A, Protopapas AA, Kyritsi V, Gogou C, Kyziroglou M, Papathanasiou E, Chatzikosma C, Michalopoulos A, Savopoulos C, Protopapas AN. Gallstones and gallbladder wall thickening in patients with cirrhosis: Prevalence and clinical impact. World J Clin Cases 2026; 14(1): 114043

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v14/i1/114043.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v14.i1.114043

Recent studies have consistently demonstrated a higher prevalence of gallstones and asymptomatic gallbladder wall thickening (aGBWT) among patients with cirrhosis than the general population, highlighting the multifactorial nature of the gallbladder pathophysiology in this patient group[1,2]. However, these conditions often remain asymptomatic in patients with cirrhosis, necessitating a deeper understanding of their etiology and clinical implications.

Gallstone formation in cirrhosis is driven by several interconnected mechanisms. Patients with cirrhosis are pre

The intricate relationship between cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and gallbladder pathophysiology underscores the unique challenges posed by gallbladder diseases in this patient population. Our study aimed to shed light on the pre

This retrospective observational study was conducted in the 1st Propaedeutic Internal Medicine Ward of the University Hospital AHEPA Thessaloniki, Greece, following approval from the Institutional Review Board of the University Hospital AHEPA. We enrolled patients with a confirmed diagnosis of cirrhosis who were hospitalized from 2019 to 2022. All patients with a confirmed diagnosis of cirrhosis admitted during this period were screened for inclusion. Only those who underwent at least one imaging modality, abdominal ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic re

Cirrhosis was diagnosed based on the clinical, laboratory, radiological, and/or histopathological criteria. Patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of acute biliary disease (e.g., right upper quadrant pain, fever, jaundice) or a known biliary etiology of cirrhosis (e.g., primary biliary cholangitis and sclerosing cholangitis) were excluded from the study. All enrolled patients underwent imaging studies during hospitalization, including abdominal ultrasound, CT, and/or MRI, as part of routine clinical care. Gallbladder wall thickening (GBWT) was measured using these imaging modalities, and GBWT > 3 mm was defined as abnormal. Demographic data, clinical history, laboratory results (e.g., liver function tests, coagulation profile, and albumin levels), and markers of cirrhosis severity (Child-Pugh classification and model for end-stage liver disease scores) were collected. Additional data on complications of cirrhosis (e.g., ascites, esophageal varices, and splenomegaly) and radiological findings related to the gallbladder (e.g., gallstones and pericholecystic fluid) were also documented.

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29. Continuous variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and are presented as mean ± SD. Categorical variables are expressed as n (%). For comparisons between groups (e.g., decompensated vs compensated cirrhosis), χ2 tests were applied for categorical variables, while t-tests were used for continuous variables with normal distribution. When comparisons involved more than two subgroups, one-way analysis of variance was employed, followed by post-hoc pairwise testing where appropriate. Correlation analyzes between gallbladder findings (presence of gallstones or wall thickening) and clinical parameters (Child-Pugh classification, etiology, presence of ascites) were performed using χ2 tests for categorical associations. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In total, 128 patients were included in this study. During the same period, only one patient was excluded because of acute biliary disease with a diagnosis of cholangitis. The mean age was 64 ± 12.2 years, and most were male (n = 94, 73.4%). The majority of the patients studied had decompensated liver cirrhosis (DeCi) (n = 100, 78.1%), and 28 patients (21.9%) presented with compensated cirrhosis. The leading etiologies of cirrhosis were alcohol-associated liver disease (n = 61, 47.7%) followed by metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (n = 21, 16.4%) and hepatitis B (n = 21, 16.4%), hepatitis C (n = 6, 4.7%) and other (n = 19, 14.8%). The Child-Pugh classification distribution was A: 19 (14.8%), B: 68 (53.1%), and C: 41 (32%). Baseline demographics are shown in Table 1.

| Variable | Value |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 64 ± 12 |

| Sex, male | 94 (73.4) |

| Cirrhosis status | |

| Compensated | 28 (21.9) |

| Decompensated | 100 (78.1) |

| Etiology of cirrhosis | |

| Alcohol-associated liver disease | 61 (47.7) |

| Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis | |

| Hepatitis B | 21 (16.4) |

| Hepatitis C | 21 (16.4) |

| Other | 19 (14.8) |

| Child-Pugh classification | |

| A | 19 (14.8) |

| B | 68 (53.1) |

| C | 41 (32.0) |

| Cholelithiasis | 51 (39.8) |

| Compensated | 6 (21.4) |

| Decompensated | 45 (45) |

| Asymptomatic gallbladder wall thickening | 42 (32.8) |

| Compensated | 3 (10.7) |

| Decompensated | 39 (39) |

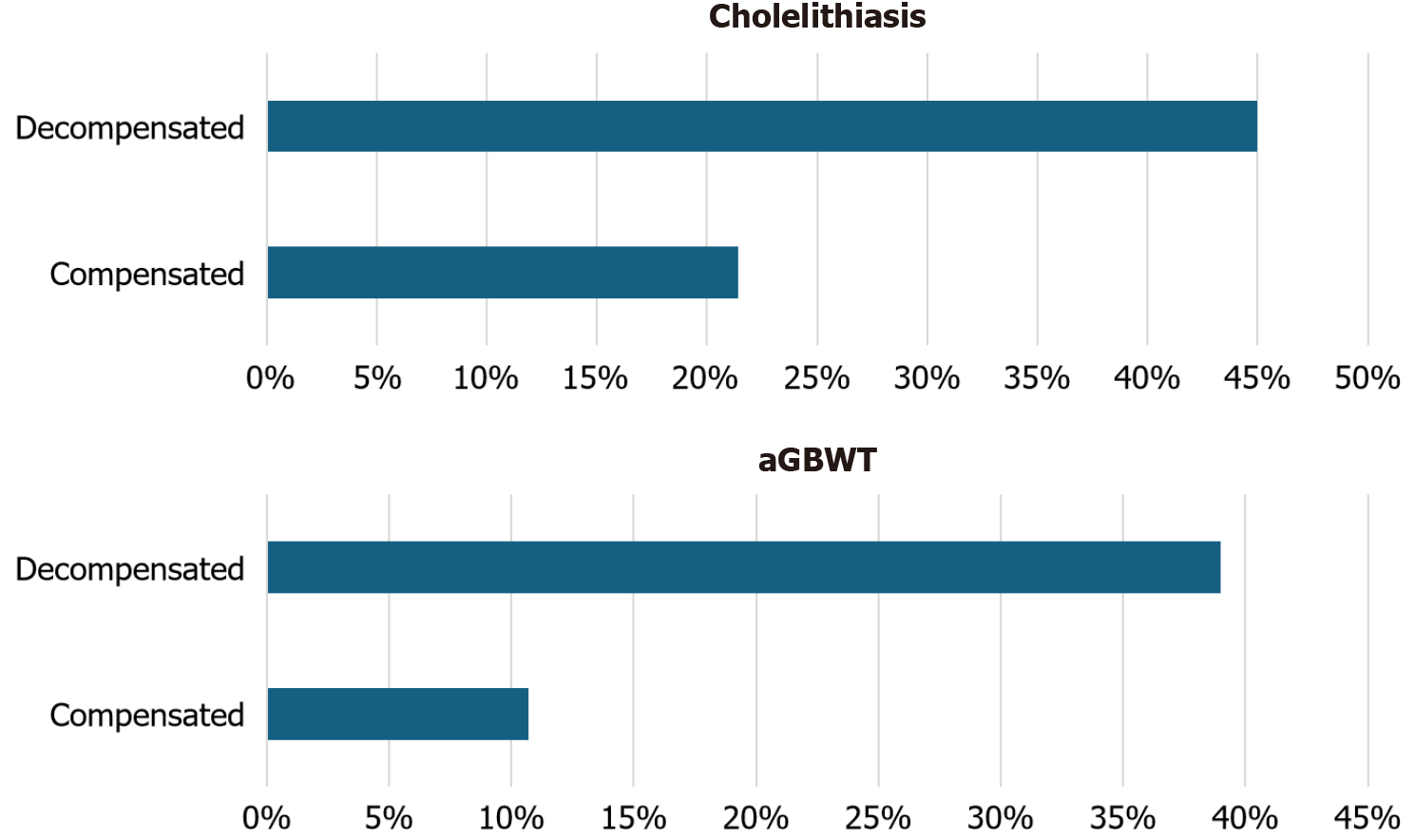

A significant percentage of patients had cholelithiasis (n = 51, 39.8%), and DeCi patients were more likely to have gallstones (45%) than compensated patients (21.4%) (P = 0.024). Furthermore, a significant number of patients presented aGBWT (n = 42, 32.8%), and nearly half of them (n = 18, 42.9%) had no concurrent gallstones. Patients with DeCi were significantly more likely to have aGBWT (39%) than those with compensated disease (10.7%, P = 0.005). No statistically significant correlations were found between cirrhosis etiology and cholelithiasis or aGBWT. Furthermore, our study showed no association between the presence of ascites or the Child-Pugh classification and aGBWT. However, the presence of gallstones was strongly correlated with the Child-Pugh stage (P = 0.008). The prevalence of gallstones and aGBWT according to the decompensation status is shown in Figure 1. Finally, no correlation was found between the presence of gallstones or aGBWT and in-hospital mortality.

Our study demonstrated a significant prevalence of gallstones (39.8%) and GBWT (32.8%) among patients with cirrhosis. In particular, DeCi patients exhibited a higher likelihood of both conditions, with 45% of DeCi patients having gallstones compared to 21.4% of those with compensated cirrhosis. Our findings are supported by those of previous studies suggesting that cirrhosis, particularly DeCi, predisposes patients to gallstone formation. While classic studies have described the pathophysiology of gallbladder changes in cirrhosis, recent studies (2020-2024) using modern imaging modalities and non-invasive portal hypertension markers provide updated prevalence data and confirm the association with disease severity[7,8]. Our study contributes contemporary evidence from a Greek cohort and underscores the clinical importance of interpreting these findings in context, rather than attributing them to primary biliary disease. This study confirms that the presence of gallbladder abnormalities is more strongly associated with decompensation than with etiology. This finding has not been consistently reported in previous studies, thereby providing new insight into the relationship between cirrhosis severity and incidental gallbladder findings. The underlying mechanisms likely involve changes in bile composition, altered gallbladder motility, and impaired bile flow, which are frequently observed in patients with cirrhosis. Portal hypertension, which is common in DeCi, can exacerbate these changes, leading to both GBWT and gallstone formation.

GBWT in patients with cirrhosis may be indicative of venous congestion due to portal hypertension and resulting fluid retention or increased capillary permeability. This thickening is often further exacerbated by hypoalbuminemia, which is very common in liver cirrhosis. Hypoalbuminemia reduces oncotic pressure and promotes transudation of fluid into the gallbladder wall[9]. GBWT is commonly associated with the severity of liver disease (Child-Pugh Class, model for end-stage liver disease score, etc.), as well as cirrhosis markers (ascites, splenomegaly, esophageal varices, etc.)[8-10]. Table 2 summarizes the key mechanisms contributing to the high prevalence of gallbladder disease in patients with cirrhosis.

| Patients with cirrhosis | Pathophysiologic mechanisms |

| Altered bile composition | Impaired bile acid synthesis and secretion; supersaturation of bile with cholesterol; hypersplenism/chronic hemolysis |

| Gallbladder hypomotility/bile stasis | Autonomic dysfunction-impaired gallbladder emptying |

| Portal hypertension | Impaired venous outflow; bacterial translocation; ascites |

| Hypoalbuminemia | Reduced oncotic pressure |

| Cause of cirrhosis | HCV; MASLD |

Interestingly, our study did not find any statistical correlation between the etiology of cirrhosis (alcohol consumption, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or other causes) and the presence of cho

Despite the well-established link between portal hypertension and gallbladder changes, our study did not find a significant correlation between ascites and the presence of gallstones or the GBWT. This lack of correlation suggests that while the ascites stage reflects the severity of liver dysfunction, it does not directly influence the formation of gallstones or the degree of GBWT. Other factors, such as hepatic artery flow or bile stasis, may play a more prominent role in the pathogenesis of these conditions. Additionally, the absence of this correlation could be related to the study’s retrospective nature and the potential for residual confounding by other unmeasured factors, such as gallbladder motility or medi

Our study has several limitations. First, its retrospective design limits its ability to establish causality between cirrhosis severity and gallbladder abnormalities. Additionally, no formal sample size calculation or power analysis was conducted, as the study population was defined by the number of eligible patients meeting the inclusion criteria within the specified period. Furthermore, the study was conducted at a single institution, which may have limited the generalizability of the findings. Future prospective studies with larger sample sizes and more diverse patient populations are needed to better understand the complex relationship between cirrhosis, gallbladder disease, and the specific etiologies of liver dysfunction. Additionally, exploring the role of factors such as gallbladder motility, medication use, and other clinical variables could provide further insights into the pathogenesis of GBWT and gallstone formation in patients with cirrhosis.

The present study was designed to investigate gallbladder changes exclusively within the cirrhotic population, focusing on the influence of disease decompensation rather than direct comparison with non-cirrhotic individuals. This approach aligns with our clinical objective, to assist clinicians in interpreting gallbladder findings in patients already known to have cirrhosis. The high frequency of aGBWT and gallstones observed in our cohort reinforces that such findings are often secondary manifestations of portal hypertension and hepatic dysfunction, rather than primary biliary pathology requiring intervention. These findings strengthen the evidence that gallbladder abnormalities in cirrhosis are primarily manifestations of advanced disease rather than independent pathologic entities. The multivariate analysis further supports that decompensation, rather than etiology or ascites alone, predicts both gallstones and GBWT. Clinicians should therefore interpret such findings within the broader context of liver function and portal hypertension, rather than as indicators of primary gallbladder disease.

Gallbladder abnormalities, including gallstones and aGBWT, are frequently observed in patients with cirrhosis, particularly in those with decompensated disease. These findings, however, are often incidental and do not necessarily indicate acute cholecystitis. Clinicians should interpret radiologic gallbladder changes in the context of liver disease severity and avoid attributing nonspecific imaging findings to acute biliary pathology. Awareness of the high prevalence of these incidental findings can help prevent unnecessary interventions and guide appropriate clinical decision-making in patients with advanced cirrhosis.

| 1. | Maggi A, Solenghi D, Panzeri A, Borroni G, Cazzaniga M, Sangiovanni A, De Fazio C, Salerno F. Prevalence and incidence of cholelithiasis in patients with liver cirrhosis. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;29:330-335. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Acalovschi M. Gallstones in patients with liver cirrhosis: incidence, etiology, clinical and therapeutical aspects. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7277-7285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Li CP, Hwang SJ, Lee FY, Chang FY, Lin HC, Lu RH, Chu CJ, Lee SD. Evaluation of gallbladder motility in patients with liver cirrhosis: relationship to gallstone formation. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:1109-1114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Acalovschi M, Dumitrascu DL, Nicoara CD. Gallbladder contractility in liver cirrhosis: comparative study in patients with and without gallbladder stones. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:17-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Alvaro D, Angelico M, Gandin C, Ginanni Corradini S, Capocaccia L. Physico-chemical factors predisposing to pigment gallstone formation in liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1990;10:228-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Saverymuttu SH, Grammatopoulos A, Meanock CI, Maxwell JD, Joseph AE. Gallbladder wall thickening (congestive cholecystopathy) in chronic liver disease: a sign of portal hypertension. Br J Radiol. 1990;63:922-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bremer SCB, Knoop RF, Porsche M, Amanzada A, Ellenrieder V, Neesse A, Kunsch S, Petzold G. Pathological gallbladder wall thickening is associated with advanced chronic liver disease and independent of serum albumin. J Clin Ultrasound. 2022;50:367-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Emara MH, Zaghloul M, Amer IF, Mahros AM, Ahmed MH, Elkerdawy MA, Elshenawy E, Rasheda AMA, Zaher TI, Haseeb MT, Emara EH, Elbatae H. Sonographic gallbladder wall thickness measurement and the prediction of esophageal varices among cirrhotics. World J Hepatol. 2023;15:216-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang TF, Hwang SJ, Lee EY, Tsai YT, Lin HC, Li CP, Cheng HM, Liu HJ, Wang SS, Lee SD. Gall-bladder wall thickening in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;12:445-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Son JY, Kim YJ, Park HS, Yu NC, Ko SM, Jung SI, Jeon HJ. Diffuse gallbladder wall thickening on computed tomography in patients with liver cirrhosis: correlation with clinical and laboratory variables. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2011;35:535-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/