Published online Jan 6, 2026. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v14.i1.112021

Revised: October 13, 2025

Accepted: December 16, 2025

Published online: January 6, 2026

Processing time: 173 Days and 22.2 Hours

Therapy discontinuation in inflammatory bowel disease, particularly involving immunomodulators, biologics, and small molecules, remains a controversial and evolving topic. This letter reflects on developments following the publication by Meštrović et al, emphasizing the complex balance between risks of relapse, anti-drug antibody formation, and potential complications of long-term immunosuppression. Recent evidence underscores high relapse rates following withdrawal - especially of anti-tumor necrosis factor agents - and highlights the lack of robust data for newer biologics. Updated guidelines from European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization, British Society of Gastroenterology, and American College of Gas

Core Tip: Discontinuation of advanced therapies in inflammatory bowel diseases remains a high-stakes decision, with relapse, immunogenicity, and long-term complications all weighing heavily. Despite updated international guidelines and emerging therapies, a personalized, closely monitored approach remains essential to ensure safe and effective treatment de-escalation in both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

- Citation: Greco S, Campigotto M, Fabbri N. Discontinuation of advanced therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: Updated evidence, guidelines, and personalized decision-making one year later. World J Clin Cases 2026; 14(1): 112021

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v14/i1/112021.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v14.i1.112021

We read with great interest the article by Meštrović et al[1] concerning the discontinuation of therapy in subjects with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Therapeutic de-escalation or discontinuation, particularly for immunomodulators, biologics, or small molecules, has gained increasing interest in the scientific community. This is partly due to the availability of new drug classes in the past decade, which aim to overcome the “therapeutic ceiling” in IBD, and the growing focus on personalized medicine[2].

Both strategies, in fact, are burdened with a series of associated risks. Frequent relapse rates, potential development of drug immunogenicity, lack of response in case of drug restart or surgery needy evolutions are fundamental factors to consider when therapy withdrawal after sustained remission is considered[3].

At the same time, as the authors of the article correctly highlighted, long-term immunosuppressive therapy might lead to adverse events, as infectious or neoplastic ones; similarly, other drugs such as 5-aminosalicylates have been proven to be ineffective in case of prolonged use in Crohn’s disease (CD) subjects, requiring therapeutic modifications[4].

The harmful effects of therapeutic discontinuation are multiple and deserve to be mentioned carefully. In 2016, a group of researchers from United Kingdom observed clinical relapse rates ranging from 36% within 1 year to 56% within 2 years after anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents’ discontinuation in a cohort of 166 patients (146 with CD[5]), while already in 2012, a prospective study on 115 patients with CD by Louis et al[6] underlined how the 1-year relapse rate after in

Moreover, up to one-third of patients who restart biologics tend to have reduced response to therapies due to anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) production, even if differences in analytical methods in ADAs detection hamper comparison of their true rates or, in some cases, their real clinical meaning[7].

In these cases, combination therapy could be an effective strategy to reduce ADAs positivity, such as it happens with anti-TNF alpha agents or with other drug classes-associated with low or absent immunological potential.

Silent disease progression, possibly leading to irreversible bowel damage (it can be avoided with closer follow-up), healthcare costs increase (relapses often require hospitalization) or psychosocial distress also must be mentioned as possible discontinuation complications[8].

Finally, patients discontinuing effective therapies are at higher risk of presenting with advanced disease requiring surgery, due to fibrostenosing stricture development or fistulizing complications, often with increased perioperative morbidity due to active disease or emergency surgery associated risks[9-11].

In essence, every attempt at therapy discontinuation must be grounded in a careful risk-benefit analysis: On the one hand, an effective de-escalation of treatment inevitably leads to reduced drug-related toxicity and lower public healthcare expenditure[12]; on the other hand, though, an increase in relapses may worsen the clinical condition of patients with IBD, resulting in greater use of “rescue” medications such as corticosteroids, more frequent hospitalizations and/or surgical interventions, as well as a substantial rise in the aforementioned healthcare costs. These are, in general, the worst consequences of therapeutic cycling, and clinician should be strongly aware of them.

At the time of publication, the authors reported the updated version of the CD topical review of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization (ECCO)[13], which suggested to consider anti-TNF agents’ withdrawal in patients with deep remission for at least 12 months, to be confirmed by laboratory (fecal calprotectin < 150-200 μg/g, C-reactive protein (CRP) < 3 mg/L, and absence of ADAs) and endoscopic tests (CD Index of Severity). Evidence about the risk of relapse and re-treatment success after ustekinumab or edolizumab discontinuation in patients with CD were scarcely described and those after Upadacitinib discontinuation not mentioned. However, this ECCO topical review underlined the need to periodically monitor such patients with biochemical and eventually endoscopic tests, to anticipate any kind of possible complication.

Further specific guidelines have been later released by other two international organizations in 2024 and 2025, respectively: The British society of Gastroenterology (BSG)[14], and the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG)[15]. Table 1 summarizes their suggestions, together with the ones by the ECCO[16].

| Organization | Supports withdrawal? | Prerequisites | Monitoring post-withdrawal | Notes |

| ECCO (2023) | In patients with CD, in deep remission. Not mentioned for patients with UC. | Endoscopic + biochemical remission, ≥ 12 months | Quarterly labs, endoscopy within 6-12 months | Encourage shared decision-making |

| ACG (2025) | Rarely, cautious approach for patients with CD. Not mentioned for patients with UC. | Sustained deep remission, low-risk profile | Intensive follow-up, FC + CRP | Not routine; relapse risk emphasized |

| BSG (2024) | Yes, in selected patients with both CD and UC. | Negative FC, CRP, mucosal healing | FC quarter 2-3 months, clinical review | Suggests dose tapering over abrupt stop |

ACG guidelines support drug withdrawal only in a minority of cases and overall suggest a cautious approach to patients and an intensive laboratory follow-up; conversely[15], BSG supports withdrawal in selective patients presenting with negative fecal calprotectin and CRP levels as well as mucosal healing, suggesting post-withdrawal monitoring bimonthly or quarterly[14].

Regarding ulcerative colitis (UC), BSG Guidelines underline the high risk of relapse in case of thiopurines or anti-TNF withdrawal: They both state that histological evidence of inflammation (defined as a Nancy score of > 1) and a raised CRP at the time of drug withdrawal could be associated with an increased risk of relapse. Of note, no specific statements regarding “therapeutic cycling” in patients with UC are included in the latest versions of the ECCO guidelines or recent topical reviews; similarly, the most recent ACG guidelines do not address this issue[13,17].

In general, regarding UC, the issues seem to be manifold: First, the heterogeneity of patients and study populations must be considered, as most studies group together IBD s, making it difficult to extrapolate data specifically for patients with UC. Often, researchers refer to remission as either complete clinical healing or endoscopic/histological healing, while the term “relapse” can refer to clinical, endoscopic outcomes or the need for intensive or surgical treatment. This variability inevitably alters the reported relapse rates, making comparisons between studies complex. Many studies are primarily observational, often retrospective, whereas well-structured randomized clinical trials specifically addressing patients with IBD (and even more so those with UC) are very few. Furthermore, the duration of follow-up is often short (12-24 months) or variable from study to study, with obvious and significant differences among the various works.

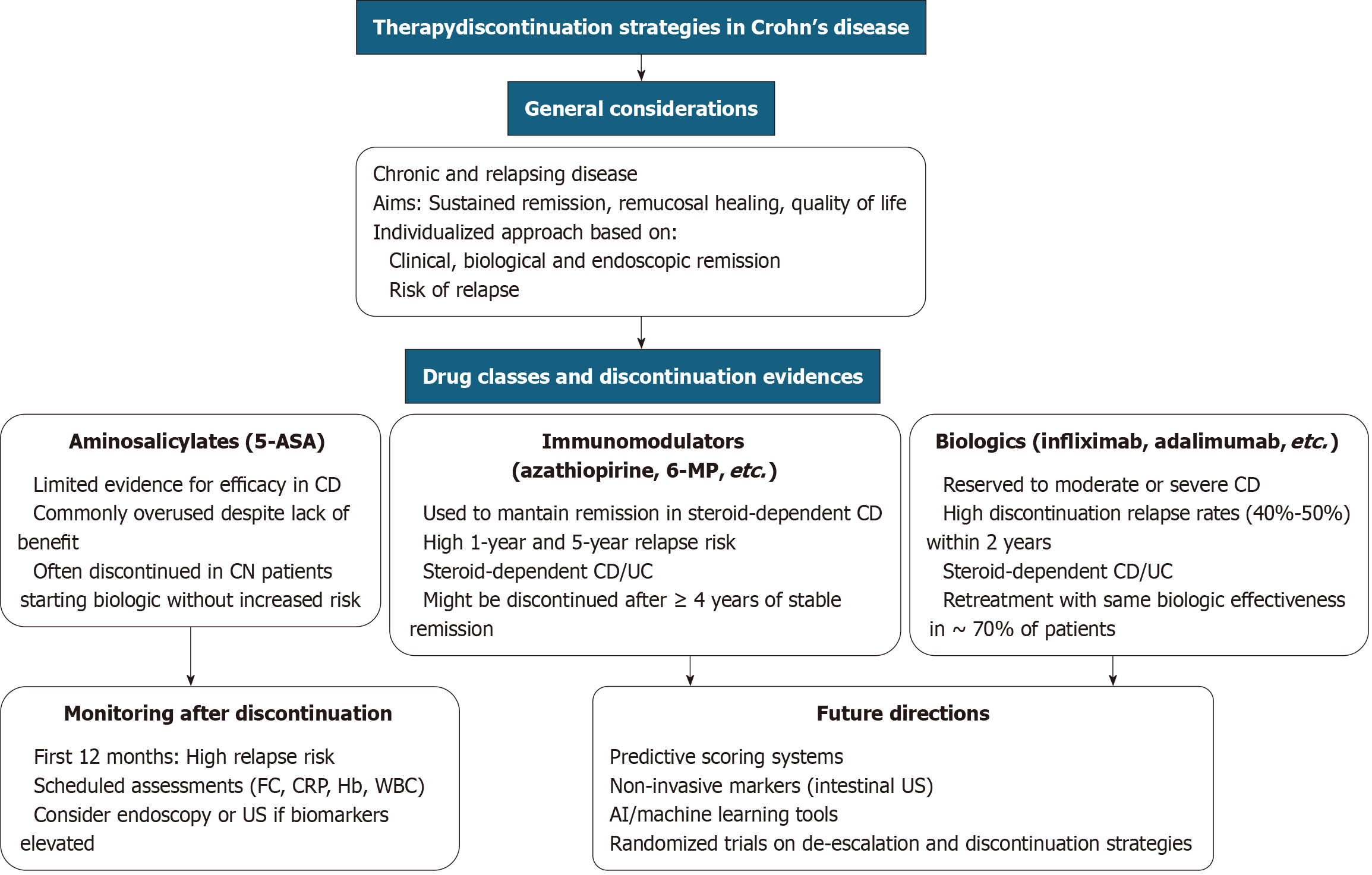

A concise flowchart has been developed to guide decision-making in the assessment of patients with IBD for potential therapy discontinuation (Figure 1).

Regarding Table 1, it is to underline that all medical societies recommend a cautious approach to advanced therapy withdrawal, an observation that remains valid even 1 year after the publication of the article by Meštrović et al[1] and despite the advent of new drug classes such as anti-interleukin 23 agents or sphingosine 1-phosphate modulators.

Some real-world data were also published in this sense, either in adult or pediatric cohorts, showing how patients with UC or CD (UC only in the study evaluating pediatric subjects) experiencing TNF failure due to delayed loss of response or intolerance usually meet better outcomes when switching to a non-anti-TNF biologic, rather than a second anti-TNF[18,19]. As discontinuation of advanced therapies in patients with both UC and CD remains controversial, each case should be carefully evaluated by clinicians using rigorous criteria and close follow-up. Shared decision-making and continued patient monitoring are, in fact, essential for safe implementation and, at present, cannot still be replaced by rigid or generalized protocols[20].

For this reason, future directions are moving toward a personalized, multimodal, and dynamic approach that goes beyond the binary choice of “continue or stop,” and instead considers a spectrum of de-escalation options (dose re

In parallel, the development of pragmatic clinical trials and well-designed prospective studies will be crucial to establish shared and validated algorithms capable of guiding clinicians in withdrawal decisions. Emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, by integrating large sets of clinical and biological data, may help stratify the individual risk of relapse with greater accuracy.

One year after publication of the article by Meštrović et al[1], the availability of new drug-classes makes personalized approach even more essential to guarantee economic sustainability and availability of all licensed therapies for patients with IBD, so that current therapeutic ceiling will be overcome.

| 1. | Meštrović A, Kumric M, Bozic J. Discontinuation of therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: Current views. World J Clin Cases. 2024;12:1718-1727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Feng Z, Kang G, Wang J, Gao X, Wang X, Ye Y, Liu L, Zhao J, Liu X, Huang H, Cao X. Breaking through the therapeutic ceiling of inflammatory bowel disease: Dual-targeted therapies. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;158:114174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Velikova T, Sekulovski M, Peshevska-Sekulovska M. Immunogenicity and Loss of Effectiveness of Biologic Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients Due to Anti-Drug Antibody Development. Antibodies (Basel). 2024;13:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Isaacs KL, Regueiro MD, Gerson LB, Sands BE. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Crohn's Disease in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:481-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 612] [Cited by in RCA: 1028] [Article Influence: 128.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kennedy NA, Warner B, Johnston EL, Flanders L, Hendy P, Ding NS, Harris R, Fadra AS, Basquill C, Lamb CA, Cameron FL, Murray CD, Parkes M, Gooding I, Ahmad T, Gaya DR, Mann S, Lindsay JO, Gordon J, Satsangi J, Hart A, McCartney S, Irving P; UK Anti-TNF withdrawal study group, Lees CW. Relapse after withdrawal from anti-TNF therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: an observational study, plus systematic review and meta-analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:910-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Louis E, Mary JY, Vernier-Massouille G, Grimaud JC, Bouhnik Y, Laharie D, Dupas JL, Pillant H, Picon L, Veyrac M, Flamant M, Savoye G, Jian R, Devos M, Porcher R, Paintaud G, Piver E, Colombel JF, Lemann M; Groupe D'etudes Thérapeutiques Des Affections Inflammatoires Digestives. Maintenance of remission among patients with Crohn's disease on antimetabolite therapy after infliximab therapy is stopped. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:63-70.e5; quiz e31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 437] [Cited by in RCA: 469] [Article Influence: 33.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Bots SJ, Parker CE, Brandse JF, Löwenberg M, Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Jairath V, D'Haens G, Vande Casteele N. Anti-Drug Antibody Formation Against Biologic Agents in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BioDrugs. 2021;35:715-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Frøslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, Vatn MH; IBSEN Group. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:412-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 834] [Cited by in RCA: 890] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Ge L, Liu S, Li S, Yang J, Hu G, Xu C, Song W. Psychological stress in inflammatory bowel disease: Psychoneuroimmunological insights into bidirectional gut-brain communications. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1016578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lewis RT, Maron DJ. Efficacy and complications of surgery for Crohn's disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2010;6:587-596. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Mignini I, Blasi V, Termite F, Esposto G, Borriello R, Laterza L, Scaldaferri F, Ainora ME, Gasbarrini A, Zocco MA. Fibrostenosing Crohn's Disease: Pathogenetic Mechanisms and New Therapeutic Horizons. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:6326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Papamichael K, Cheifetz AS. Therapeutic drug monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease: for every patient and every drug? Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2019;35:302-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Noor NM, Sousa P, Bettenworth D, Gomollón F, Lobaton T, Bossuyt P, Casanova MJ, Ding NS, Dragoni G, Furfaro F, van Rheenen PF, Chaparro M, Gisbert JP, Louis E, Papamichail K. ECCO Topical Review on Biological Treatment Cycles in Crohn's Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:1031-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Moran GW, Gordon M, Sinopolou V, Radford SJ, Darie AM, Vuyyuru SK, Alrubaiy L, Arebi N, Blackwell J, Butler TD, Chew T, Colwill M, Cooney R, De Marco G, Din S, Din S, Feakins R, Gasparetto M, Gordon H, Hansen R, Kok KB, Lamb CA, Limdi J, Liu E, Loughrey MB, McGonagle D, Patel K, Pavlidis P, Selinger C, Shale M, Smith PJ, Subramanian S, Taylor SA, Tun GSZ, Verma AM, Wong NACS; IBD guideline development group. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on inflammatory bowel disease in adults: 2025. Gut. 2025;74:s1-s101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 52.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Afzali A, Long MD, Barnes EL, Isaacs KL, Ha CY. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Crohn's Disease in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025;120:1225-1264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gordon H, Minozzi S, Kopylov U, Verstockt B, Chaparro M, Buskens C, Warusavitarne J, Agrawal M, Allocca M, Atreya R, Battat R, Bettenworth D, Bislenghi G, Brown SR, Burisch J, Casanova MJ, Czuber-Dochan W, de Groof J, El-Hussuna A, Ellul P, Fidalgo C, Fiorino G, Gisbert JP, Sabino JG, Hanzel J, Holubar S, Iacucci M, Iqbal N, Kapizioni C, Karmiris K, Kobayashi T, Kotze PG, Luglio G, Maaser C, Moran G, Noor N, Papamichael K, Peros G, Reenaers C, Sica G, Sigall-Boneh R, Vavricka SR, Yanai H, Myrelid P, Adamina M, Raine T. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn's Disease: Medical Treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18:1531-1555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 93.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Raine T, Bonovas S, Burisch J, Kucharzik T, Adamina M, Annese V, Bachmann O, Bettenworth D, Chaparro M, Czuber-Dochan W, Eder P, Ellul P, Fidalgo C, Fiorino G, Gionchetti P, Gisbert JP, Gordon H, Hedin C, Holubar S, Iacucci M, Karmiris K, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Lakatos PL, Lytras T, Lyutakov I, Noor N, Pellino G, Piovani D, Savarino E, Selvaggi F, Verstockt B, Spinelli A, Panis Y, Doherty G. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Ulcerative Colitis: Medical Treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16:2-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 584] [Cited by in RCA: 665] [Article Influence: 166.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Kapizioni C, Desoki R, Lam D, Balendran K, Al-Sulais E, Subramanian S, Rimmer JE, De La Revilla Negro J, Pavey H, Pele L, Brooks J, Moran GW, Irving PM, Limdi JK, Lamb CA; UK IBD BioResource Investigators, Parkes M, Raine T. Biologic Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Real-World Comparative Effectiveness and Impact of Drug Sequencing in 13 222 Patients within the UK IBD BioResource. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18:790-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Patel PV, Zhang A, Bhasuran B, Ravindranath VG, Heyman MB, Verstraete SG, Butte AJ, Rosen MJ, Rudrapatna VA; ImproveCareNow Pediatric IBD Learning Health System. Real-world effectiveness of ustekinumab and vedolizumab in TNF-exposed pediatric patients with ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2024;78:1126-1134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bretto E, Ribaldone DG, Caviglia GP, Saracco GM, Bugianesi E, Frara S. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Emerging Therapies and Future Treatment Strategies. Biomedicines. 2023;11:2249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lutz M, Horst S, Caldera F. Applying Biomarkers in Treat-to-target Approach for IBD. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2025;27:41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Clough J, Colwill M, Poullis A, Pollok R, Patel K, Honap S. Biomarkers in inflammatory bowel disease: a practical guide. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2024;17:17562848241251600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/