Published online Dec 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i36.114472

Revised: October 20, 2025

Accepted: December 11, 2025

Published online: December 26, 2025

Processing time: 96 Days and 18.3 Hours

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute systemic vasculitis in young children that may cause coronary aneurysms, thrombosis, myocardial infarction, and sudden death if diagnosis is delayed.

We report a 19-month-old male patient who presented after 25 days of progre

This case underscores the challenges of recognizing atypical KD and highlights the importance of early suspicion, rapid resuscitation, and multimodal therapies, including Continuous renal replacement therapy and therapeutic plasma exchange, in improving survival and neurological outcomes.

Core Tip: Kawasaki disease (KD) is a childhood illness that can damage the heart if not recognized early. We describe a 19-month-old boy who developed fever, cough, and rash for almost a month, but was repeatedly treated as having infections. He suddenly went into cardiac arrest and was found to have severe heart vessel damage with clots from undiagnosed KD. He required prolonged resuscitation, advanced life support, and multiple treatments including cooling therapy, combined interventions of continuous renal replacement and plasma exchange. Remarkably, he recovered with good heart and brain function, showing the importance of early recognition and aggressive care in severe KD.

- Citation: Truong DMT, Bui LT, Nguyen TK, Pham HT, Vo BQ, Nguyen TT. Cardiac arrest as initial presentation of Kawasaki disease with giant coronary aneurysms: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(36): 114472

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i36/114472.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i36.114472

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute systemic vasculitis of unknown etiology that predominantly affects children under five years of age and is now recognized as the leading cause of acquired pediatric heart disease in developed countries[1]. It has been reported globally, with an incidence varying from 10 per 100000 to 20 per 100000 in North America and Europe to over 300 per 100000 in Northeast Asia, where the rates continue to rise[2]. Emerging data from China and India suggest an increasing incidence, raising concerns that KD may surpass rheumatic heart disease as the most common acquired cardiac disorder in children[3]. Variability in diagnostic practices and surveillance further complicates the accurate estimation of its global burden. KD is diagnosed clinically in the absence of pathognomonic tests, relying on distinct characteristics and the exclusion of conditions that mimic it. The hallmark of KD is a high fever persisting for ≥ 5 days, accompanied by at least four of the following five criteria: Bilateral non-purulent conjunctivitis, oropharyngeal changes, polymorphous rash, extremity changes (edema followed by desquamation), and non-purulent cervical lymphadenopathy[1,4]. The most severe complication of KD is coronary artery involvement, with aneurysm formation occurring in approximately 25% of untreated cases[5]. Timely intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy reduces the incidence of coronary artery aneurysms from approximately 25% to 4%; however, up to 20% of patients remain refractory and require add

A 19-month-old male weighing 11 kg, with no prior history of cardiovascular disease or allergies, had received appro

Cardiac arrest and prolonged resuscitation.

His clinical disease manifestations and progression are summarized as follows.

Onset phase (days 1-6): The child presented with high fever (39 °C), cough, and rhinorrhea. A local clinic initially diagnosed viral fever and pneumonia and offered supportive treatment with prescribed antipyretics.

Progressive phase (days 7-18): The patient experienced recurrent fever and developed a generalized rash, non-purulent conjunctivitis, and desquamation of the fingertips and toes. Hence, the patient’s parents sought medical care at a tertiary Children’s Hospital in Ho Chi Minh City. He was clinically diagnosed with pneumonia and acute urticaria, treated for 10 days in the hospital, and discharged after the clinical resolution of fever and rash.

Complication phase (days 19-25): On days 19-20 of illness, the patient developed high fever (39 °C), cough, and wheezing and was diagnosed with bronchitis. Treatment was initiated with amoxicillin-clavulanate at a dosage of 70 mg/kg/day. On day 21, fever persisted, accompanied by frequent coughing and mild chest retraction. The patient was admitted to a local hospital, where bronchopneumonia was clinically diagnosed. Laboratory findings revealed a white blood cell count of 20 × 109/L and a C-reactive protein level of 20 mg/L. The patient was started on intravenous ceftriaxone (100 mg/kg/day). Between days 22 and 24, the fever remained continuous with progressive respiratory distress. The patient required supplemental oxygen via a nasal cannula, with a pulse rate of 140 beats per minute and oxygen saturation of 95%. During this period, the infant appeared irritable, had poor feeding, and exhibited desquamation of the skin on the extremities. On day 25, the patient became agitated, exhibited tonic posturing, and experienced cardiorespiratory arrest. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was performed for 45 minutes until the return of spontaneous circulation was achieved. He was intubated, and pink frothy sputum from the endotracheal tube indicated acute pulmonary edema. The patient was administered vasopressors (adrenaline 0.1 μg/kg/minute, noradrenaline 0.1 μg/kg/minute) and transferred to a tertiary Children’s Hospital.

He had no underlying disease before this admission. Family history revealed normal findings.

On admission to the Emergency Department at our hospital, the patient was comatose (Glasgow Coma Scale score of 4 points, E1V1M2), cyanotic, had a weak pulse (30 beats/minute), cold extremities, capillary refill time > 3 seconds, pupil diameters of 2 mm on both eyes with sluggish light reflex, and periungual desquamation.

Laboratory findings revealed severe metabolic acidosis (pH = 7.14, blood lactate > 13.3 mmol/L) and multiorgan injury, as indicated by aspartate transaminase 385 IU/L, alanine transaminase 175 IU/L, CK-MB enzyme 106 IU/L, cardiac enzyme-hs-cTnI 2.3 ng/mL, and systemic inflammation (serum procalcitonin > 100 ng/mL, serum ferritin > 1676 μg/L) (Table 1).

| Clinical status | Laboratory findings | Imaging | Interventions | |

| Local hospital | Cardiac arrest, CPR for 45 minutes and return of spontaneous circulation, pink frothy sputum, GCS 4 points | WBC: 20.5 × 109/L, AST: 385 IU/L, ALT: 175 IU/L, hs-cTnI: 2.3 ng/mL | Echocardiography: Coronary artery aneurysm (LMCA: 4.8 mm, LAD: 8 mm, RCA: 7.5 mm), RCA thrombus; chest X-ray: Acute pulmonary edema | CPR, intubation, vasopressors (adrenaline, noradrenaline) |

| Emergency Department | GCS 4 points, shock status, VIS 210, CRT > 3 seconds | pH = 7.14, serum lactate > 13.3 mmol/L, troponin I > 50 μg/L, serum ferritin > 1676 μg/L, INR = 8.03 | ECG: ST depression in leads-DI, aVL. Echocardiography: Giant coronary artery aneurysm (LMCA diameter = 1.6 mm, LAD: 7.5 mm, RCA diameter = 8.1 mm), thrombus in RCA | Mechanical ventilation, IVIG (2 g/kg), vasopressors, intravenous antibiotic (cefepime) and heparin |

| Before CRRT and TPE | Shock status, respiratory failure, GCS 4 points, acute kidney injury | AST: 3670 IU/L, ALT: 1029 IU/L, serum ferritin > 1676 μg/L, INR = 8.03 | Echocardiography: Giant coronary artery aneurysm, EF 55%-60% | Vasopressors, IVIG, methylprednisolone 10 mg/kg/day, CRRT, anti-cerebral edema therapy (NaCl 3%) |

| After CRRT and TPE | Hemodynamic stability (VIS 47) | AST: 222 IU/L, ALT: 32 IU/L, serum ferritin: 1784 μg/L, INR = 1.32 | Chest X-ray: Improvement in pulmonary injury; echocardiography: Coronary artery aneurysm, absence of thrombus | Combined CRRT and TPE, intravenous heparin and corticosteroids |

| At PICU discharge | Alert (GCS 14 points), extubation and enteral feeding | AST: 54 IU/L, ALT: 75 IU/L, serum ferritin: 776 μg/L | Echocardiography: Coronary artery aneurysm, EF 62%; brain magnetic resonance imaging: Normal findings | Aspirin, ceasing vasopressors, transferred to the Cardiology Unit for further sustained therapies |

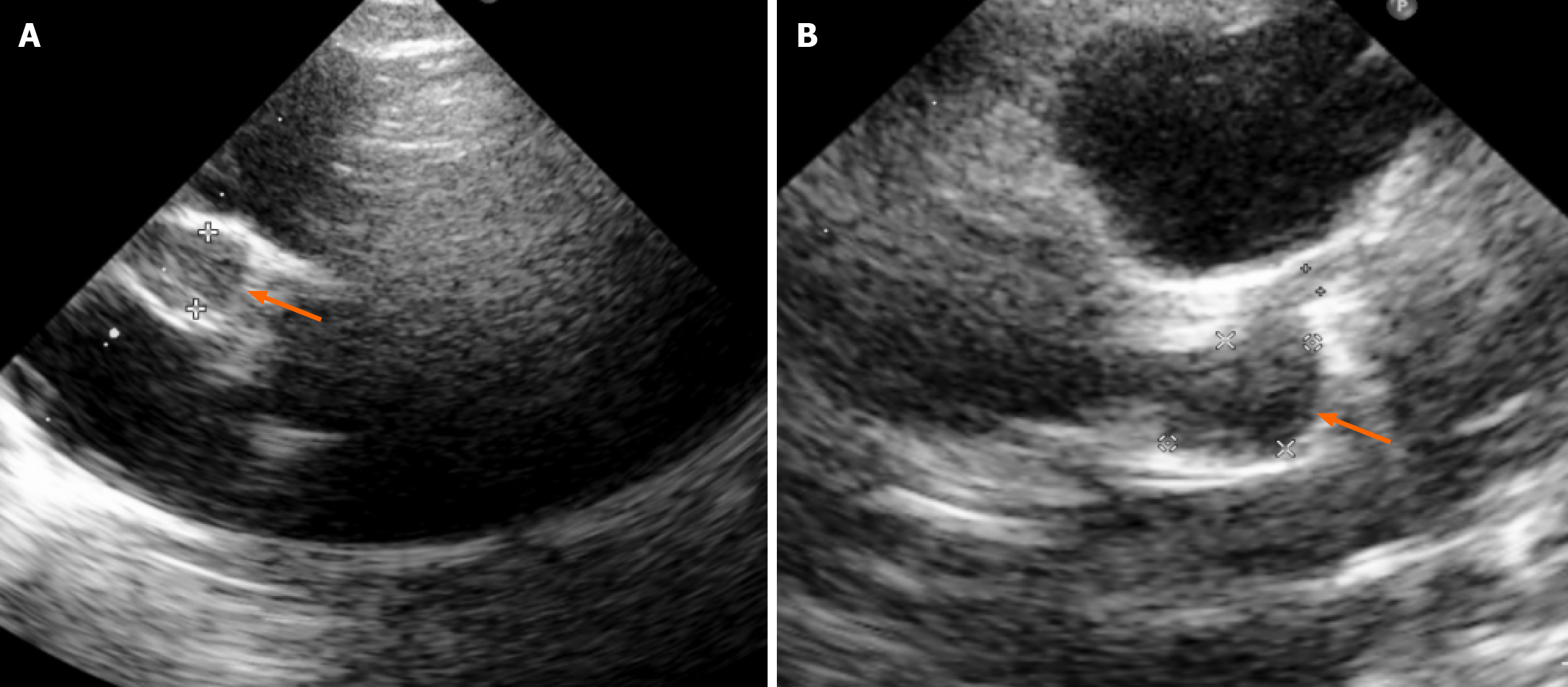

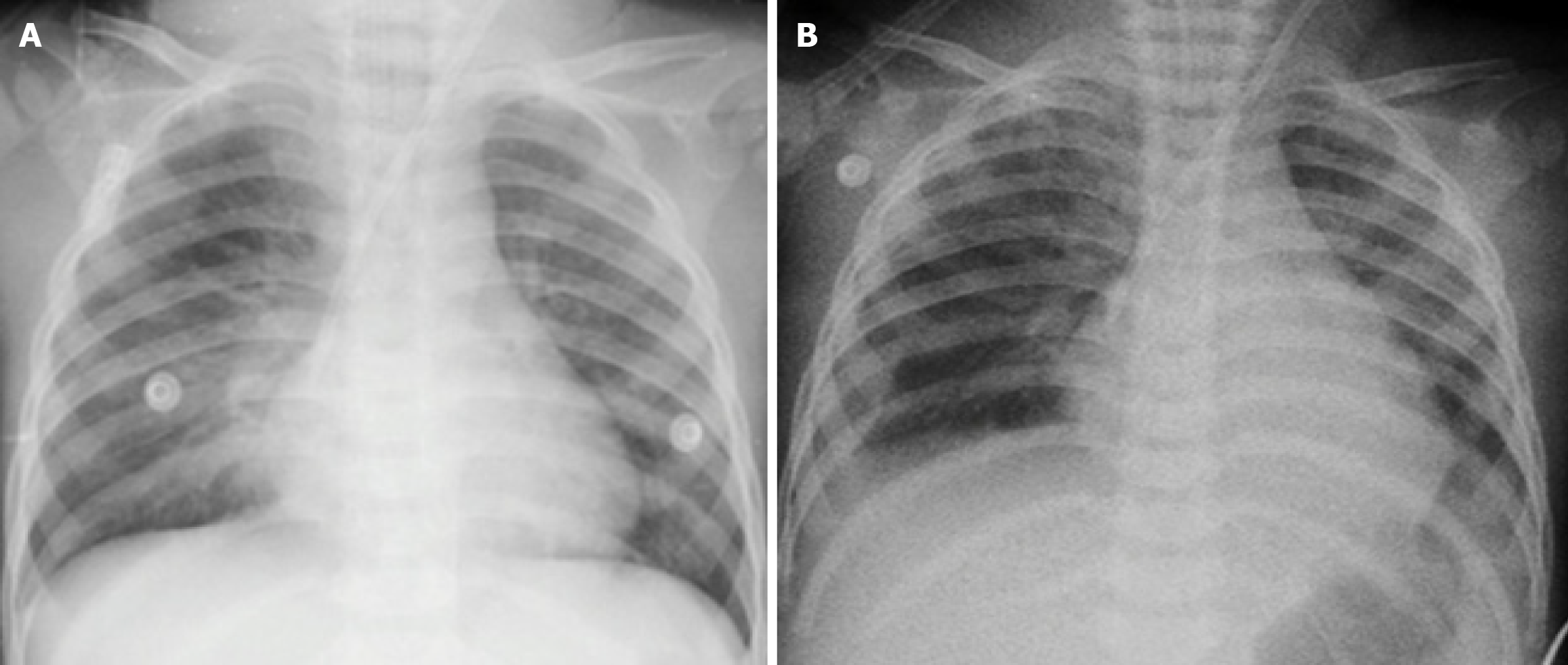

Bedside echocardiography revealed giant bilateral coronary artery aneurysms [right coronary artery (RCA): 8.1 mm, Z-score = +19] with a thrombus in the RCA, left main coronary artery: 1.6 mm, left anterior descending artery: 7.5 mm × 10.3 mm, Z-score = +15 (Figure 1). The left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was preserved (55%-60%), and the right ventricle was mildly dilated with reduced contractility. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia with ST-segment depression in leads DI and aVL, suggestive of acute myocardial infarction (Figure 2). Chest radiograph confirmed acute pulmonary edema (Figure 3).

The multidisciplinary consultations were performed by intensivists and cardiologists.

He was diagnosed with sudden cardiac arrest caused by KD complicated with giant coronary aneurysms.

The patient was then transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit. The patient was mechanically ventilated (tidal volume 6 mL/kg) and treated with high-dose vasopressors (adrenaline, noradrenaline, milrinone; vasoactive-inotropic score: 210), IVIG at a dose of 2 g/kg, methylprednisolone (10 mg/kg/day), unfractionated heparin, and cefepime (150 mg/kg/day). His post-admission laboratory test results indicated a cytokine storm. Therefore, continuous veno-venous hemodiafiltration was initiated soon after, combined with targeted temperature management (35-36 °C). In addition to the continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) was indicated and started on day 3 to manage the cytokine storm and progressive multiorgan failure. The TPE was performed with 1.5 fold of plasma volume per cycle for three subsequent cycles.

CRRT was performed using the GambroPrismaflex® system (Baxter, France) with an oXiris® heparin-grafted AN69 filter (endotoxin/cytokine adsorption capacity). A Balton double-lumen dialysis catheter (Balton, Warsaw, Poland) was inserted into the right internal jugular vein, with catheter size determined by patient weight. Continuous veno-venous hemodiafiltration mode was employed, combining convective and diffusive clearance. The blood flow rate was set at 5 mL/kg/minute, with PrismasolB0® solution (Gambro Dasco S.p.A., Sondalo, Italy) used as the dialysate. Targeted temperature management was integrated within the CRRT system, maintaining a rectally monitored core temperature of 35-36 °C.

TPE was performed using the Gambro Prismaflex® system (Baxter, United States). A Balton® double-lumen dialysis catheter (Balton, Warsaw, Poland) was inserted into the right internal jugular vein. The blood flow rate was maintained at 4-6 mL/kg/minute. The plasma exchange volume was estimated using the formula: 0.07 × body weight (kg) × (1 - hematocrit), and standard TPE was performed 1.5 times the calculated plasma volume[9]. The system was primed with normal saline (NaCl 0.9%) and heparin. Unfractionated heparin was administered restrictively at 10-20 IU/kg/hour during the procedure. Fresh-frozen plasma was used as the replacement fluid. Vital signs were monitored closely throughout the procedure. To mitigate the risks of hypocalcemia and allergic reactions, patients received 10% intravenous calcium chloride supplementation along with prophylactic diphenhydramine and methylprednisolone.

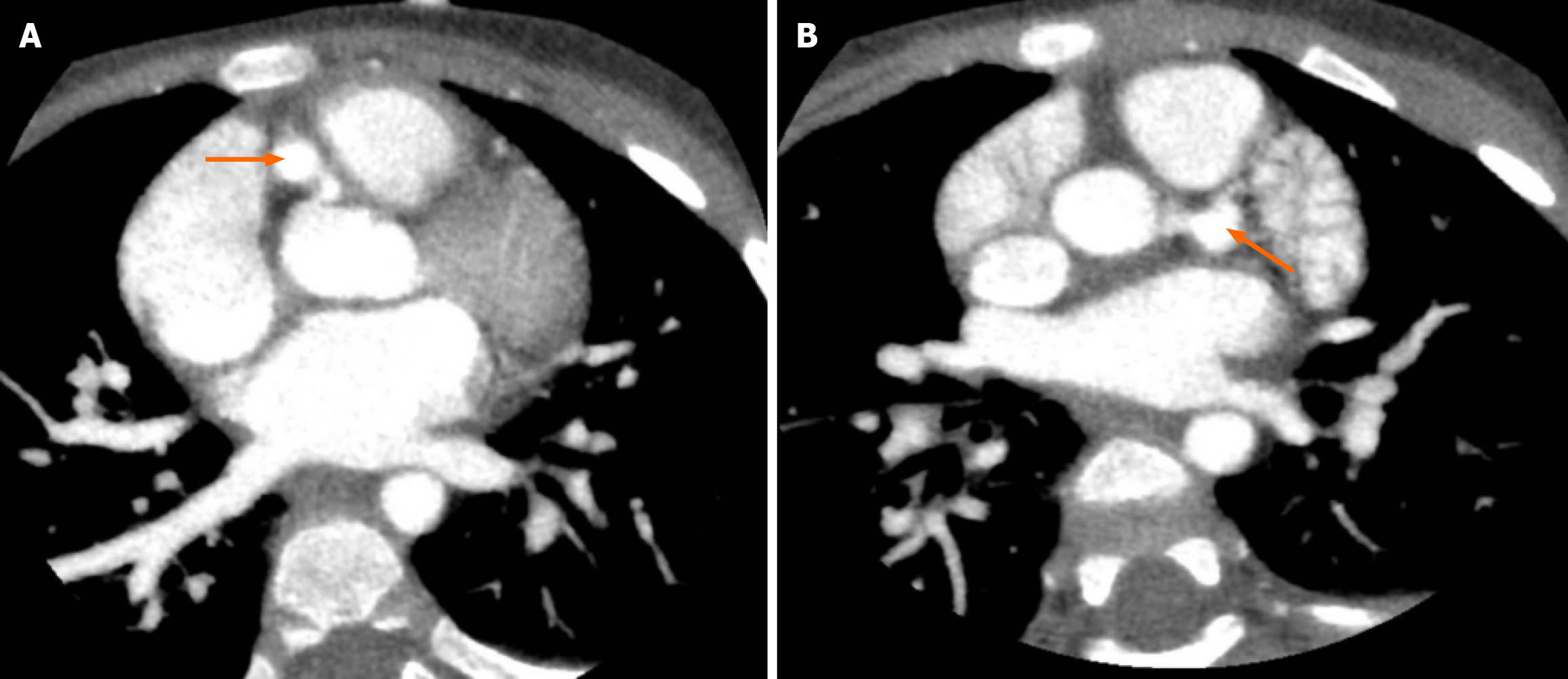

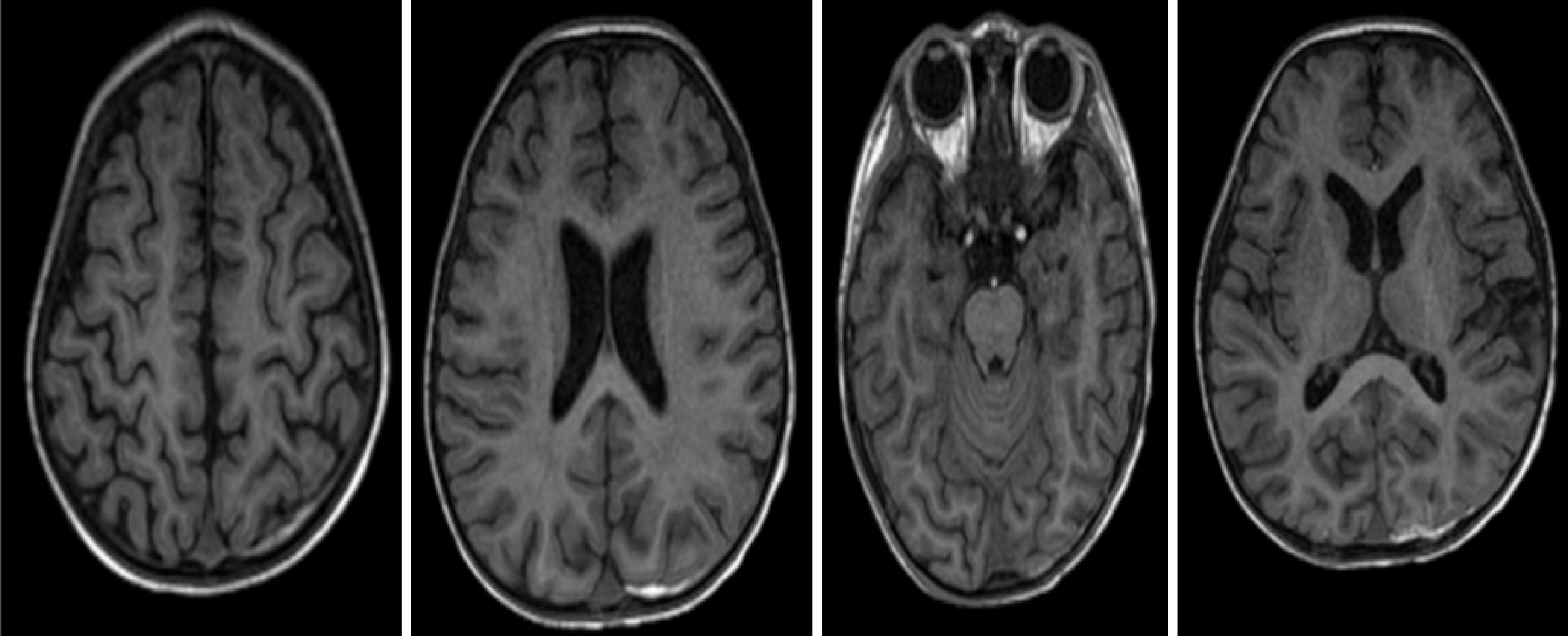

After 6 days of treatment in the pediatric intensive care unit, the patient’s hemodynamic status was stabilized (reduced vasoactive-inotropic score of 47), pulmonary function improved (PaO2/FiO2 ratio 110), and consciousness significantly improved (Glasgow Coma Scale 14 points, E4V5M5). He was weaned off mechanical ventilation after 12 days and transferred to the Cardiology Department for continued KD treatment. Rechecked contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan of coronary arteries revealed dilated coronary artery (Figure 4). Repeated echocardiography revealed persistent coronary artery aneurysms, absence of thrombus, and LVEF of 62%. In addition, brain magnetic resonance imaging was performed to examine the presence of potential neurological injury, which showed no intracranial structural damage (Figure 5).

At two months post-discharge, the infant was alert, with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15, heart rate of 120 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation of 98%. There was no evidence of muscle weakness or symptoms indicative of heart failure in this patient. The patient remained on dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel in combination with apixaban, and continued to undergo monthly cardiovascular evaluations. The most recent echocardiographic assessment demonstrated a LVEF of 60%, absence of intracardiac thrombus, and persistent but improved coronary artery dilation (left main coronary artery: 3.7 mm; left anterior descending artery: 6.6 mm; RCA: 3.4 mm) compared with prior mea

This case report describes a rare presentation of undiagnosed KD in a 19-month patient who suffered a sudden cardiac arrest resulting from a myocardial infarction. The infarction was secondary to thrombosis within giant coronary artery aneurysms, a complication of KD. Notably, the patient exhibited exceptional neurological recovery, with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 14 and normal brain magnetic resonance imaging findings after prolonged CPR. This outcome highlights the effectiveness of a prompt, aggressive, and multimodal treatment approach.

In this patient, resuscitation was performed in accordance with the Pediatric Advanced Life Support protocols, including ventilation, chest compressions, and vasopressor administration. Post-return of spontaneous circulation care was pivotal; early echocardiography revealed coronary artery aneurysms and thrombosis, thereby guiding the initiation of KD-directed therapies, including IVIG, high-dose corticosteroids, and anticoagulation with heparin. Although robust evidence supporting IVIG administration beyond the 10th day of illness is limited[10], its use in the subacute phase is recommended for patients with persistent fever, systemic inflammation, or coronary artery abnormalities[11,12]. Coronary thrombectomy was considered but ultimately deferred, given the technical challenges in a 19-month-old patient and the limited evidence supporting its efficacy in pediatric acute myocardial infarction[13,14]. Instead, clinical stabilization was prioritized and accomplished by aggressive resuscitation, combined CRRT and TPE, serial monitoring with bedside echocardiography, and troponin I measurements. Favorable neurological recovery may be attributed to early recognition of cardiac arrest, high-quality CPR, rapid diagnosis, CRRT to maintain homeostasis, and TPE to attenuate the effect of cytokine storm. Targeted temperature management (35-36 °C), combined with comprehensive neuroresuscitation, preserved cerebral perfusion in accordance with the established post-cardiac arrest care guidelines[15-17]. Notably, prolonged CPR time has raised concerns about neurological injury; nevertheless, no neurological sequelae were detected on brain magnetic resonance imaging.

The specific treatment of KD is directed at attenuating systemic inflammation and preventing coronary artery complications, which are the most serious KD sequelae. Early initiation of therapy, ideally within the first 10 days of fever, is critical for reducing the risk of coronary artery aneurysms[1]. IVIG remains the standard first-line treatment, with a single infusion shown to reduce the incidence of coronary artery aneurysms from approximately 30% in untreated patients to < 5% when administered promptly[6]. In cases where fever persists beyond 36 hours after IVIG, a repeat infusion may be indicated[12]. Aspirin is administered for both anti-inflammatory and antiplatelet effects, typically in high doses during the acute febrile phase, followed by a transition to low-dose therapy to mitigate the risk of thrombosis in the subacute phase[1]. Although aspirin use in children is generally limited due to the risk of Reye’s syndrome, the cardiovascular benefits of KD outweigh this concern under careful medical supervision[18]. Corticosteroids are increasingly employed in high-risk patients or those refractory to IVIG, their adjunctive use has been associated with shorter symptom duration, reduced hospitalization, and decreased risk of coronary complications[19]. Post-treatment follow-up with echocardiography and pediatric cardiology evaluation is essential to monitor coronary abnormalities and guide long-term manage

In addition, we conducted a medical review of case reports of severe KD complicated by sudden cardiac arrest (Table 2)[20-29]. The high mortality rate is notable in most cases due to the rupture of inflamed aneurysms of the coronary arteries. Our study also showed a similar clinical scenario; however, our patient had a distinct clinical manifestation of experiencing a cytokine storm. In this regard, the combination of TPE and CRRT combined with intensive resuscitation and IVIG administration significantly improved survival outcomes, as observed in this patient. Based on the reviewed case reports, several potential risk factors for sudden cardiac arrest in patients with KD were identified. Incomplete or atypical KD was more frequently reported in young infants, particularly those under one year of age, than in older children. This age group appears to be at an increased risk of developing giant coronary artery aneurysms, which may predispose them to fatal cardiac events. Additional risk factors associated with severe KD complications include prolonged fever of unknown etiology and unexplained, markedly elevated inflammatory bio

| Ref. | Clinical features | Interventions | Patients’ outcomes |

| Maresi et al[20], 2001 | A 2-month-old male infant diagnosed of rhinitis and coughing without fever for a week before admission, presented with conjunctival hyperemia and allergic exanthema on the chest and arms. Laboratory findings: Leukocytosis (WBC: 15.37 × 109/L), elevated CRP; and thrombocytosis (476 × 109/L) | Ceftriaxone | The patient died suddenly on the 7th day of hospitalization. Autopsy findings: Cause of death (cardiac tamponade); underlying cause (rupture of an inflamed aneurysm in the LAD coronary artery) |

| Imai et al[21], 2006 | A 5-year-old Japanese male, diagnosed of KD on the 5th day since disease onset. Laboratory findings: WBC 29.4 × 109/L; CRP 16.61 mg/dL; platelet 324 × 109/L. Echocardiography (on the day 12 since disease onset): A giant LAD artery aneurysm (diameter = 18 mm) | CPR, IVIG, aspirin, propranolol, nifedipine, and warfarin | On the 13th day of illness, cardiac arrest developed abruptly and the patient died one hour later |

| Ashrafi et al[22], 2007 | A 4-month-old Caucasian male, recurring fever for three weeks, maculopapular rash, edema of upper extremities, erythema of oral mucosa and conjunctival injection. Laboratory findings: Leukocytosis and thrombocytosis | IVIG, aspirin | The infant suddenly developed spasmodic movements, followed by shallow breathing and cardiac arrest. Autopsy findings: Cause of death (prominent aneurysmal dilatation involving, LAD, circumflex artery, posterior descending artery, right coronary artery) |

| A 9-year-old Caucasian girl, developed KD with coronary artery involvement and revealed an immunodeficiency of unknown etiology, steatohepatitis, and interstitial pneumonitis | The patient developed gastrointestinal bleeding and cardiac arrest | ||

| Pucci et al[23], 2008 | A 3-month-old female infant, with 8-day history of intermittent fever, presented with oral and lip fissures and a diffuse maculopapular eruption. Laboratory tests: WBC 29 × 109/L; thrombocytemia 771 × 109/L; CRP 142 mg/L. Echocardiogram: Two small aneurysms (diameter = 3.5 mm) at the origin of the RCA, proximal dilatation in the LAD and circumflex coronary (LCx) arteries | IVIG, aspirin, corticosteroids and heparin | The patient experienced sudden cardiac arrest and died on the seventh day of treatment. Cause of death: Occlusive coronary thrombosis with a giant aneurysm |

| Pucci et al[24], 2012 | A 3-month-old male experienced intermittent fever for 6 days, skin rash, conjunctivitis, respiratory symptoms, and remitting enteritis, was diagnosed with bronchiolitis and hospitalized on day 17 after disease onset. Laboratory tests: WBC 13.2 × 109/L, platelet count 921 × 109/L, CRP 90 mg/dL | Betamethasone | The child suddenly died at home. Autopsy findings: Cause of death (giant aneurysm of the RCA with subocclusive thrombosis) |

| Dionne et al[25], 2015 | A 3-month-old infant was initially diagnosed with a urinary tract infection. Twelve days later, he presented with persistent fever, vomiting, conjunctivitis and discharged with a diagnosis of viral gastroenteritis. Being febrile for 21 days, he was admitted to the emergency due to shock. Laboratory tests: WBC 30 × 109/L, platelet count 494 × 109/L, CRP 200 mg/L, increased cardiac enzyme-troponin I 59.0 μg/L. Echocardiogram: LVEF of 14% with diffuse coronary artery dilatation | IVIG, aspirin, heparin, inotropes, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator therapy, methylprednisolone, infliximab, cyclophosphamide and anakinra | The patient died in-hospital. Cause of death: Multi-vessel obstruction and aneurysms |

| Argo et al[26], 2016 | A 7-month-old infant, apparently well-nourished and without fever or exanthem was admitted to the emergency unit. Laboratory tests: Significantly increased platelet count (651 × 109/L), cardiac enzyme troponin-T 196 ng/mL | He died two hours after being admitted to the hospital. Autopsy findings: Cause of death (aneurysmatic and thrombotic in RCA) | |

| Yajima et al[27], 2016 | A 5-month-old male was hospitalized for suppuration at the injection site following BCG vaccination at 1.5 months of age. He presented with fever (38 °C) for 7 consecutive days, bilateral edema of the inferior limbs and polymorphous exanthemas on his thoracoabdominal regions. Laboratory tests: WBC 10.9 × 109/L, platelet count 534 × 109/L, CRP 4.78 mg/dL | Antibiotics | Four days after discharge, he refused breastfeeding and died suddenly after readmission. Autopsy findings: Cause of death myocardial infarction was due to thrombus emboli in the coronary arteries |

| Zhang et al[28], 2018 | A 5-year-old male admitted with fever (38.5 °C) for 3 days, bilateral conjunctival congestion, erythematous lips, diffuse erythema in the face, neck, and torso, swelling and pain below the right earlobe. He was initially diagnosed with mumps and suspected scarlet fever. Laboratory tests: Procalcitonin 0.71 ng/mL, CRP 51.05 mg/mL, and interleukin 6 = 15.03 pg/mL | Ribavirin, intravenous cefixime | The patient died on day 8 after hospitalization. Autopsy findings: Cause of death (pericardial tamponade due to a rupture of inflamed aneurysm of the LAD) |

| Salzillo et al[29], 2025 | A 6-year-old male presented with high fever and bilateral lymphadenopathy, was initially diagnosed with classic-type Hodgkin lymphoma. Two weeks later he was readmitted because of mild precordial chest pain, a rapidly progressive cardiac failure, unresponsive to inotropic support. Echocardiography: LVEF of 30%, dramatically increased cardiac enzyme-troponin and NT-pro-BNP | CPR | The child died at 24 hours after admission due to acute heart failure. Autopsy findings: A huge aneurysm filled with large organized thrombi of the RCA and left coronary artery |

The delayed diagnosis of KD, reported in approximately 9.9% of cases in a Malaysian cohort, is often attributable to atypical or incomplete KD presentations[30]. To improve early recognition, strategies such as initiating evaluation on the fourth day of fever if four of five clinical features are present, lowering diagnostic thresholds in infants, and applying criteria for incomplete KD have been proposed[31]. In limited-resource hospitals, preventive strategies should prioritize the early recognition and diagnosis of KD to reduce the risk of life-threatening complications, such as sudden cardiac arrest. Clinicians should be trained to consider KD in any child presenting with persistent fever lasting more than five days, especially when associated with mucocutaneous signs or unexplained inflammation, even in the absence of all the classic diagnostic criteria. Establishing simplified diagnostic checklists and ensuring access to basic laboratory tests (including full blood count, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate). Promoting the early use of echocardiography, where available, is critical. Strengthening referral systems to tertiary care centers for timely IVIG administration and specialist evaluations can further improve outcomes. Preventive strategies should be emphasized to avoid similar events in the future, particularly in resource-limited settings.

This case highlights the diagnostic challenges of atypical KD, in which manifestations may appear asynchronously or in subtle forms, leading to misclassification as other febrile illnesses. In our patient, the delayed initiation of IVIG facilitated the progression of ongoing vasculitis, resulting in giant coronary artery aneurysms with a low probability of regression and a high risk of long-term complications, such as stenosis, calcification, and thrombosis[18]. Failure to promptly diagnose and treat KD can precipitate severe cardiac sequelae, as observed in this case. Nevertheless, survival and favorable neurological recovery were likely facilitated by high-quality CPR, early integration of CRRT with TPE to support multiorgan failure and mitigate the cytokine storm, and timely management of cerebral edema. Notably, combined interventions of CRRT with TPE have been shown to be effective in managing dengue-associated acute liver failure with cytokine storm and multiorgan dysfunction at our institution[32]. However, evidence of its role in post-cardiac arrest care after experiencing KD remains limited. Therefore, this case underscores the potential of multidisciplinary, early goal-directed therapy to improve outcomes, while also highlighting the need for larger multicenter studies to validate these observations and inform future pediatric resuscitation protocols.

This case demonstrates the catastrophic consequences of a delayed diagnosis of KD and the need for specific treatment, with cardiac arrest as a rare initial manifestation of myocardial infarction due to coronary artery thrombosis. Multidisciplinary interventions, including CRRT, TPE, and targeted temperature management, enabled survival with favorable neurological recovery. Vigilance for atypical KD and early echocardiography are essential to optimize outcomes and guide long-term follow-up of coronary complications. Lifelong follow-up is essential to monitor persistent aneurysms and to prevent recurrent thrombosis.

The authors sincerely grateful to the patient and his family for their cooperation and for providing consent for the publication of this case. We would like to acknowledge the dedicated efforts of the Emergency, Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, and Cardiology teams involved in the management of this patient. We are grateful to the patients, research staffs, particularly Dr Tuong TTH and nurses for their support in this study.

| 1. | McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, Burns JC, Bolger AF, Gewitz M, Baker AL, Jackson MA, Takahashi M, Shah PB, Kobayashi T, Wu MH, Saji TT, Pahl E; American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Diagnosis, Treatment, and Long-Term Management of Kawasaki Disease: A Scientific Statement for Health Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e927-e999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1586] [Cited by in RCA: 2618] [Article Influence: 290.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Elakabawi K, Lin J, Jiao F, Guo N, Yuan Z. Kawasaki Disease: Global Burden and Genetic Background. Cardiol Res. 2020;11:9-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Singh S, Vignesh P, Burgner D. The epidemiology of Kawasaki disease: a global update. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100:1084-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jone PN, Tremoulet A, Choueiter N, Dominguez SR, Harahsheh AS, Mitani Y, Zimmerman M, Lin MT, Friedman KG; American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Lifelong Congenital Heart Disease and Heart Health in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; and Council on Clinical Cardiology. Update on Diagnosis and Management of Kawasaki Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;150:e481-e500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 49.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kato H, Koike S, Yamamoto M, Ito Y, Yano E. Coronary aneurysms in infants and young children with acute febrile mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome. J Pediatr. 1975;86:892-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 350] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zeng YY, Zhang M, Ko S, Chen F. An Update on Cardiovascular Risk Factors After Kawasaki Disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:671198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zamojska J, Kędziora P, Januś A, Kaczmarek K, Smolewska E. Cardiac Arrest During Exertion as a Presentation of Undiagnosed Kawasaki Disease: A Case Report. J Clin Med. 2024;13:6380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sliem A, Siu A, Zheng J, Magana S, Alagha Z, Ghallab M, Lopez M. Cardiac Arrest as the Initial Presentation of Undiagnosed Kawasaki Disease: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus. 2023;15:e40855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hunt EA, Jain NG, Somers MJ. Apheresis therapy in children: an overview of key technical aspects and a review of experience in pediatric renal disease. J Clin Apher. 2013;28:36-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Oates-Whitehead RM, Baumer JH, Haines L, Love S, Maconochie IK, Gupta A, Roman K, Dua JS, Flynn I. Intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of Kawasaki disease in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2003:CD004000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, Gewitz MH, Tani LY, Burns JC, Shulman ST, Bolger AF, Ferrieri P, Baltimore RS, Wilson WR, Baddour LM, Levison ME, Pallasch TJ, Falace DA, Taubert KA; Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; American Heart Association; American Academy of Pediatrics. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004;110:2747-2771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1268] [Cited by in RCA: 1305] [Article Influence: 62.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Saguil A, Fargo M, Grogan S. Diagnosis and management of kawasaki disease. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:365-371. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Ten CW, Chang YF, Hung WL, Chen MR. Optical Coherence Tomography in a 9-Year-Old Kawasaki Disease Patient with Giant Coronary Artery Aneurysms and Acute Myocardial Infarction. Am J Case Rep. 2023;24:e939788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Stidham T, McKee J, Vogt J, Siomos AK. Successful Intervention for a Thrombosed Giant Coronary Artery Aneurysm in Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children. JACC Case Rep. 2022;4:945-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kernan KF, Berger RP, Clark RSB, Scott Watson R, Angus DC, Panigrahy A, Callaway CW, Bell MJ, Kochanek PM, Fink EL, Simon DW. An exploratory assessment of serum biomarkers of post-cardiac arrest syndrome in children. Resuscitation. 2021;167:307-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Morgan RW, Kirschen MP, Kilbaugh TJ, Sutton RM, Topjian AA. Pediatric In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in the United States: A Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:293-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Holmberg MJ, Wiberg S, Ross CE, Kleinman M, Hoeyer-Nielsen AK, Donnino MW, Andersen LW. Trends in Survival After Pediatric In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest in the United States. Circulation. 2019;140:1398-1408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pilania RK, Bhattarai D, Singh S. Controversies in diagnosis and management of Kawasaki disease. World J Clin Pediatr. 2018;7:27-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kobayashi T, Saji T, Otani T, Takeuchi K, Nakamura T, Arakawa H, Kato T, Hara T, Hamaoka K, Ogawa S, Miura M, Nomura Y, Fuse S, Ichida F, Seki M, Fukazawa R, Ogawa C, Furuno K, Tokunaga H, Takatsuki S, Hara S, Morikawa A; RAISE study group investigators. Efficacy of immunoglobulin plus prednisolone for prevention of coronary artery abnormalities in severe Kawasaki disease (RAISE study): a randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoints trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1613-1620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 459] [Cited by in RCA: 482] [Article Influence: 34.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Maresi E, Passantino R, Midulla R, Ottoveggio G, Orlando E, Becchina G, Meschis L, Amato G. Sudden infant death caused by a ruptured coronary aneurysm during acute phase of atypical Kawasaki disease. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:1407-1409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Imai Y, Sunagawa K, Ayusawa M, Miyashita M, Abe O, Suzuki J, Karasawa K, Sumitomo N, Okada T, Mitsumata M, Harada K. A fatal case of ruptured giant coronary artery aneurysm. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165:130-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ashrafi AH, Wang J, Stockwell CA, Lloyd D, McAlvin JB, Russo P, Shehata BM. Kawasaki disease: four case reports of cardiopathy with an institutional and literature review. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2007;10:491-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pucci A, Martino S, Celeste A, Linari A, Tibaldi M, Camosso E, Muscio M, Barattia G, Riva C, Bartoloni G. Angiogenesis, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and procoagulant factors in coronary artery giant aneurysm of a fatal infantile Kawasaki disease. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2008;17:186-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pucci A, Martino S, Tibaldi M, Bartoloni G. Incomplete and atypical Kawasaki disease: a clinicopathologic paradox at high risk of sudden and unexpected infant death. Pediatr Cardiol. 2012;33:802-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dionne A, Kokta V, Chami R, Morissette G, Dahdah N. Fatal Kawasaki disease with incomplete criteria: Correlation between optical coherence tomography and pathology. Pediatr Int. 2015;57:1174-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Argo A, Zerbo S, Maresi EG, Rizzo AM, Sortino C, Grassedonio E, Midiri M. Utility of post mortem MRI in definition of thrombus in aneurismatic coronary arteries due to incomplete Kawasaki Disease in infants. J Forensic Radiol Imaging. 2016;7:17-20. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Yajima D, Shimizu K, Oka K, Asari M, Maseda C, Okuda K, Shiono H, Ohtani S, Ogawa K. A Case of Sudden Infant Death Due to Incomplete Kawasaki Disease. J Forensic Sci. 2016;61 Suppl 1:S259-S264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zhang J, Tuokan T, Shi Y. Sudden Death as a Sequel of Ruptured Giant Coronary Artery Aneurysm in Kawasaki Disease. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2018;39:375-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Salzillo C, De Gaspari M, Basso C, Francavilla M, De Leonardis F, Marzullo A. Sudden cardiac death caused by Kawasaki coronary artery vasculitis in a child with Hodgkin's lymphoma. Case report and literature review. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2025;74:107700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mat Bah MN, Alias EY, Sapian MH, Abdullah N. Delayed diagnosis of Kawasaki disease in Malaysia: Who is at risk and what is the outcome. Pediatr Int. 2022;64:e15162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Suda K, Iemura M, Nishiono H, Teramachi Y, Koteda Y, Kishimoto S, Kudo Y, Itoh S, Ishii H, Ueno T, Tashiro T, Nobuyoshi M, Kato H, Matsuishi T. Long-term prognosis of patients with Kawasaki disease complicated by giant coronary aneurysms: a single-institution experience. Circulation. 2011;123:1836-1842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Vo LT, Do VC, Trinh TH, Vu T, Nguyen TT. Combined Therapeutic Plasma Exchange and Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy in Children With Dengue-Associated Acute Liver Failure and Shock Syndrome: Single-Center Cohort From Vietnam. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2023;24:818-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/