Published online Dec 16, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i35.112965

Revised: September 16, 2025

Accepted: December 10, 2025

Published online: December 16, 2025

Processing time: 127 Days and 7.6 Hours

Celiac disease (CD) is an autoimmune disorder associated with an increased risk of pancreatitis, yet large-scale studies examining long-term risk and specific etio

To assess the long-term risk of pancreatitis in CD patients.

We conducted a population-based cohort study with consecutive patients dia

A total of 160228 patients were identified to have CD, and the remaining 250725 individuals without CD were considered as controls. At 7-year follow-up, CD patients exhibited a significantly higher risk of acute pancreatitis (HR = 2.05; 95%CI: 1.93-2.17) and chronic pancreatitis (HR = 1.42; 95%CI: 1.31-1.54) compared to controls. Elevated risks for alcohol-induced (HR = 1.35), biliary (HR = 1.37), and idiopathic pancreatitis (HR = 1.49) were also observed. Findings remained robust across all follow-up intervals and sensitivity analyses.

Patients with CD have a substantially increased long-term risk of acute and chronic pancreatitis, including alcohol-related, biliary, and idiopathic subtypes. These findings support the routine surveillance of pancreatitis in CD management and highlight the need for further research into disease-specific risk factors and mitigation ap

Core Tip: Celiac disease (CD) is an immune-mediated disorder with well-recognized gastrointestinal and extraintestinal manifestations. However, limited large-scale studies have evaluated its association with pancreatic disease. We investigated the long-term risk of acute and chronic pancreatitis in a large, propensity score-matched cohort of patients with CD. CD was associated with a significantly higher risk of pancreatitis, including alcohol-related, biliary, and idiopathic subtypes, com

- Citation: Krishnan A, Teran D, Mukherjee D. Risk of incident pancreatitis in patients with celiac disease: A population-based matched retrospective cohort study. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(35): 112965

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i35/112965.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i35.112965

Celiac disease (CD) is a chronic, immune-mediated disorder precipitated by the ingestion of gluten-derived peptides, which trigger an aberrant immune response in genetically susceptible individuals[1]. Current estimates indicate that CD affects approximately 0.5% to 1% of the global population, with an increasing prevalence noted in recent years, particularly in the United States[2-5]. This rise has been attributed to heightened vigilance in screening and the advent of more sensitive and specific diagnostic modalities, such as serologic assays and duodenal biopsies[6,7]. Extraintestinal complications of CD, especially pancreatic complications, are a major area of concern because of their severity and impact on quality of life[8-10]. The growing incidence of CD brings new challenges, notably an expanded spectrum of extraintestinal complications. Among these, pancreatic manifestations - including acute pancreatitis (AP) and chronic pancreatitis (CP) - pose significant clinical concern due to their impact on patient morbidity and quality of life[8-10]. Global epidemiological data reveal a steady increase in the prevalence of AP and CP, with CP rising by 52.1 cases per 100000 individuals between 1996 and 2016[11]. Although gallstones and alcohol misuse remain primary etiological factors for pancreatitis, emerging evidence implicates CD as an independent risk factor for both AP and CP[9,12-15]. Previous studies linking CD and pancreatitis have generally been limited by small sample sizes, single-center designs, and short observation periods, reducing their generalizability[14,15].

A recently published large-scale cohort study demonstrated significantly higher rates of pancreatitis among patients with CD compared to controls, supporting the hypothesis of an association between CD and pancreatic disease[15]. However, robust, population-based investigations evaluating long-term outcomes remain sparse. Therefore, the present study aims to address this gap by systematically examining the long-term risk of AP and CP, as well as their specific etiologies, among individuals with CD in a large, multicenter cohort. By leveraging comprehensive, real-world data, the present study aimed to investigate the long-term risk of AP and CP among CD patients, as well as to identify the frequency of various etiologies of pancreatitis in this population and to clarify disease associations and inform clinical decision-making for patient management.

A population-based, multicenter retrospective cohort study was performed using data from the TriNetX research net

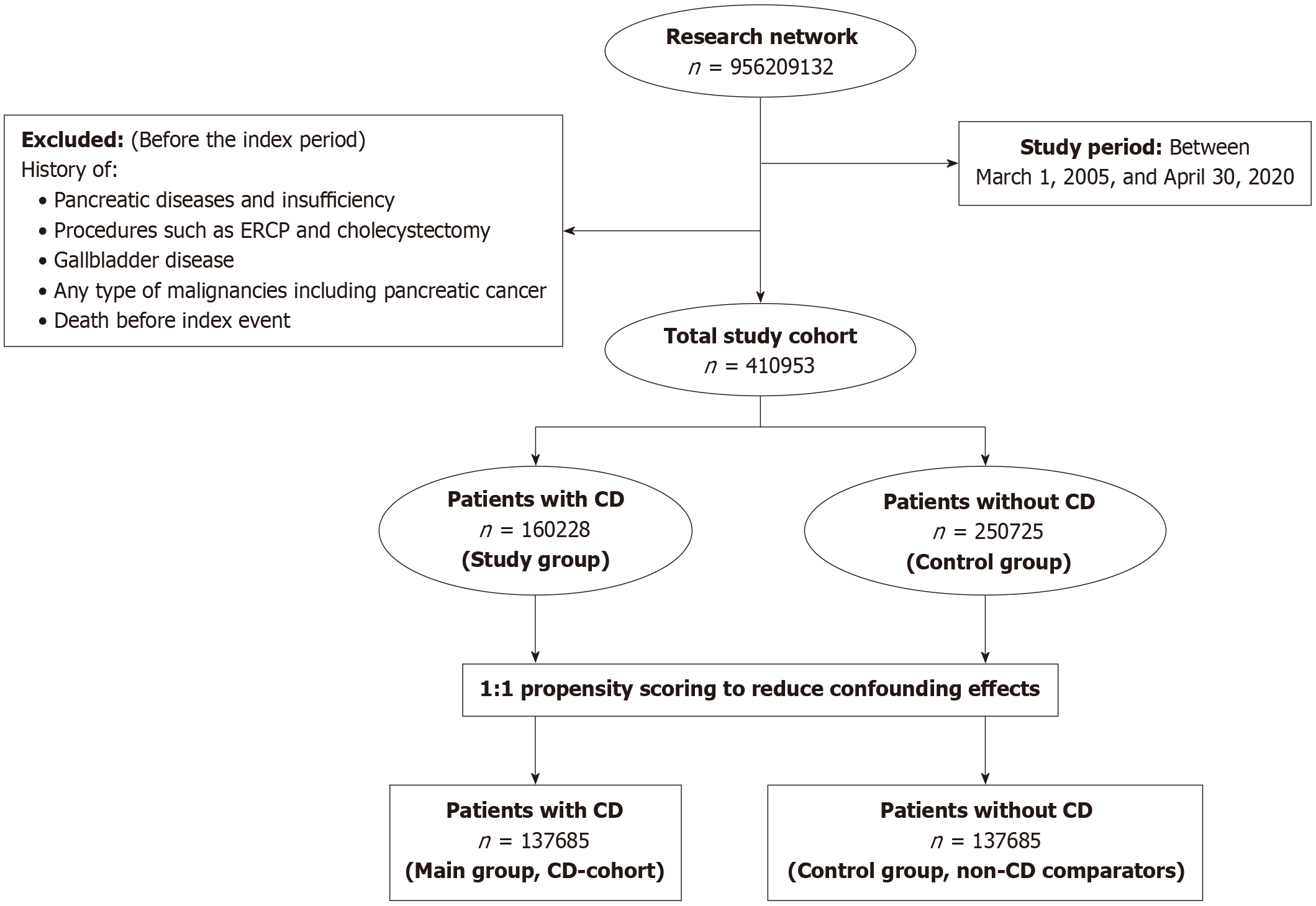

The cohort comprised all patients with a diagnosis of CD between March 2005 and April 2022, identified using validated ICD codes. Details of the codes, selection algorithm, and quality controls are provided in the Supplementary material. For the control group, individuals without CD from the same time frame were selected from the general population. Individuals with prior diagnoses of pancreatic or gallbladder disorders, those who had undergone procedures such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or cholecystectomy, and patients with any malignancy, including pancreatic cancer, before the index date (defined as the CD diagnosis date or equivalent reference date for controls) were excluded (Figure 1).

Each participant with CD was paired with a control from the non-celiac cohort through 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM) to minimize potential confounding. The propensity score model incorporated predefined covariates recognized as possible confounders, including age, sex, race or ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, or non-Hispanic other), nicotine dependence, alcohol-related conditions, body mass index, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyper

| Variables | Before propensity matching | After propensity matching | ||||

| CD (n = 160228) | Non-CD (n = 250725) | SMD | CD (n = 137685) | Non-CD (n = 137685) | SMD | |

| Age, mean ± SD | 39.1 ± 22 | 47.2 ± 18.9 | 0.3959 | 42.9 ± 21.1 | 43.8 ± 20.2 | 0.0462 |

| Age by categories | ||||||

| < 18 years | 33862 (21.1) | 18691 (7.5) | 0.3985 | 18650 (13.5) | 15394 (11.2) | 0.0300 |

| 18 years to < 40 years | 49079 (30.6) | 18691 (7.5) | 0.0825 | 42014 (30.5) | 43884 (31.9) | < 0.0001 |

| 40 years to < 60 years | 43112 (26.9) | 67446 (26.9) | 0.2202 | 42978 (31.2) | 43884 (31.9) | 0.0142 |

| ≥ 60 years | 34175 (21.3) | 93062 (37.1) | 0.1670 | 34043 (24.7) | 34523 (25.1) | 0.0081 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 113373 (70.8) | 182852 (72.9) | 0.0483 | 99033 (71.9) | 100461 (72.9) | 0.0223 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 7885 (4.9) | 22051 (8.8) | 0.0602 | 7463 (5.4) | 6616 (4.8) | 0.0279 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 131627 (82.2) | 169727 (67.7) | 0.3382 | 110190 (80.0) | 110461 (80.2) | 0.0049 |

| Black or African American | 6385 (4.0) | 41009 (16.4) | 0.4181 | 6385 (4.6) | 6306 (4.6) | 0.0027 |

| Asian | 1795 (1.1) | 5213 (2.1) | 0.0765 | 1743 (1.3) | 1633 (1.2) | 0.0073 |

| Others | 19865 (12.4) | 33341 (13.3) | 0.0765 | 18860 (13.7) | 18805 (13.7) | 0.0012 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 25.8 ± 7.4 | 28.8 ± 7.3 | 0.4132 | 26.6 ± 7.2 | 28 ± 7.4 | 0.1974 |

| Nicotine dependence | 9288 (5.8) | 27951 (11.1) | 0.1931 | 9118 (6.6) | 8873 (6.4) | 0.0072 |

| Alcohol related disorders | 2801 (1.7) | 8911 (3.6) | 0.1126 | 2777 (2.0) | 2672 (1.9) | 0.0055 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 16210 (10.1) | 50025 (20.0) | 0.2778 | 16152 (11.7) | 16568 (12.0) | 0.0093 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 13489 (8.4) | 32412 (12.9) | 0.1464 | 11912 (8.7) | 12108 (8.8) | 0.0015 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 7367 (4.6) | 18577 (7.4) | 0.1186 | 7139 (5.2) | 7394 (5.4) | 0.0083 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 1397 (0.9) | 3712 (1.5) | 0.0565 | 1348 (1.0) | 1488 (1.1) | 0.0101 |

| Hypercalcemia | 1072 (0.7) | 3313 (1.3) | 0.0658 | 1046 (0.8) | 1087 (0.8) | 0.0034 |

| Autoimmune diseases | ||||||

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus | 6694 (4.2) | 6943 (2.8) | 0.0770 | 4590 (3.3) | 2862 (2.1) | 0.0774 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2569 (1.6) | 17670 (7.0) | 0.2701 | 2565 (1.9) | 2530 (1.8) | 0.0019 |

| Gallbladder diseases | ||||||

| Cholecystitis | 1312 (0.8) | 2525 (1.0) | 0.0198 | 1181 (0.9) | 1150 (0.8) | 0.0025 |

| Cholelithiasis | 3241 (2.0) | 8548 (3.4) | 0.0854 | 3138 (2.3) | 3048 (2.2) | 0.0044 |

| Other diseases of the gallbladder | 1598 (1.0) | 3271 (1.3) | 0.0284 | 1483 (1.1) | 1423 (1.0) | 0.0043 |

| Other diseases of the biliary tract | 1520 (0.9) | 3121 (1.2) | 0.0284 | 1426 (1.0) | 1374 (1.0) | 0.0038 |

| Family history | ||||||

| Familial hypercholesterolemia | 100 (0.1) | 295 (0.12) | 0.0044 | 100 (0.1) | 68 (0.0) | 0.0094 |

| Procedure | ||||||

| ERCP | 407 (0.3) | 896 (0.4) | 0.0256 | 393 (0.3) | 344 (0.3) | 0.0013 |

Propensity scores for all participants in both cohorts were generated using logistic regression applied to the input matrices. The analysis was conducted in Python version 3.6.5 (Python Software Foundation), utilizing standard libraries such as NumPy and sklearn. To verify the consistency of results, parallel analyses were conducted in R version 3.4.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A greedy nearest-neighbor algorithm with a caliper of 0.1 pooled standard deviations was used for matching. Balance was assessed using standardized mean differences, with an a priori threshold of 0.10 for acceptable balance. The order of the rows in the covariate matrix was randomized before matching to further mitigate bias.

The primary outcomes were the incidence of AP and CP among CD patients. Secondary outcomes included the incidence of specific etiologic subtypes: Biliary, alcohol-induced, and idiopathic pancreatitis. Definitions for each outcome utilized validated ICD-9/10 codes, as detailed in the Supplementary material.

All statistical analyses were performed in real-time using the TriNetX platform. Continuous data were described as mean ± SD or as median and interquartile range, depending on the distribution. Categorical data were reported as counts and percentages. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each outcome. Proportionality was verified analytically, and these analyses were performed using the survival package in R version 3.2.3. Baseline-adjusted HRs were calculated for all comparisons. Results were validated by cross-checking outputs from SAS v9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute). Statistical significance was defined by a two-sided alpha ≤ 0.05.

A prespecified secondary analysis assessed time-dependent risk for pancreatitis, estimating HRs at distinct follow-up intervals, specifically, initiating follow-up at 1 and 3 years post-CD diagnosis. Sensitivity analyses further evaluated the robustness of results by excluding cases diagnosed within the first year after CD diagnosis, accounting for potential diagnostic misclassification and disease heterogeneity.

This study analyzed data from a total of 410953 individuals. Of these, 160228 had a documented history of CD and were assigned to the primary cohort. The remaining 250725 participants, who had no prior diagnosis of CD, formed the comparison group. Detailed baseline characteristics for those in the CD cohort are presented in Table 1. The majority of CD patients were white (n = 131627, 82.2%) and female (n = 113373, 70.8%). 49079 (30.6%) patients were between the ages of 18 years and 40 years. Rates of common comorbidities were lower in the CD group compared to the non-CD patients, including hyperlipidemia (n = 16210, 10.1%), type 2 diabetes mellitus (n = 13489, 8.4%), and familial hypercholesterolemia (n = 100, 0.1%). Notably, type 1 diabetes prevalence was higher in the CD cohort (n = 6694, 4.2%). Substance use measures, such as nicotine dependence (5.8%) and alcohol-related disorders (1.7%), were less frequent among CD patients. Parallel demographic and comorbidity trends were observed in the control group, with a higher proportion of individuals ≥ 60 years (37.1%) and higher rates of metabolic and cardiovascular comorbidities. Furthermore, although slightly higher in the non-CD cohort, both cohorts had a similar percentage of cholecystitis, gallbladder disease, and biliary tract disease. There was also a similar percentage of patients with a history of ERCP procedures in the CD and non-CD cohorts.

Results of laboratory findings for CD and non-CD patients are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Serologic and laboratory findings revealed CD-associated immunoreactivity: Serum gliadin peptide immunoglobulin A and immunoglobulin G were markedly elevated in CD patients compared to controls (Immunoglobulin A: 22 units/volume vs 7.75 units/volume; immunoglobulin G: 25.7 units/volume vs 7.6 units/volume). Several liver function tests for CD patients were lower compared to those for non-CD patients, including alanine aminotransferase (29.2 U/L vs 31.8 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (28.8 U/L vs 30.7 U/L), total bilirubin (0.557 mg/dL vs 0.593 mg/dL), and gamma-glutamyl transferase (54.3 U/L vs 93.4 U/L). However, CD patients had higher levels of alkaline phosphatase (99.2 U/L vs 88.4 U/L) and albumin (4.14 g/dL vs 4.02 g/dL) compared to the non-CD cohort. Markers of inflammation, specifically sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, were reduced in CD patients vs controls. No statistically significant differences were detected for lipid parameters.

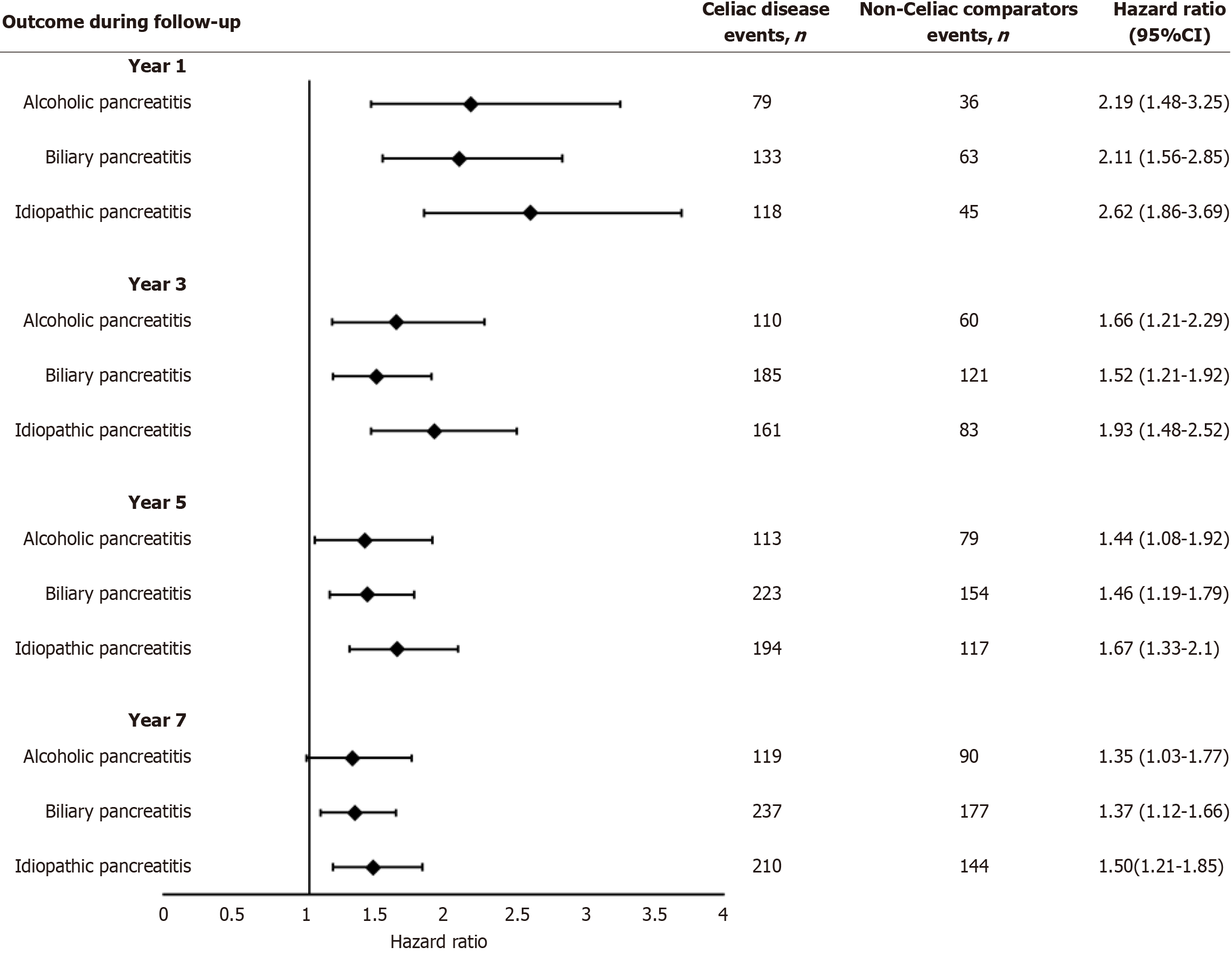

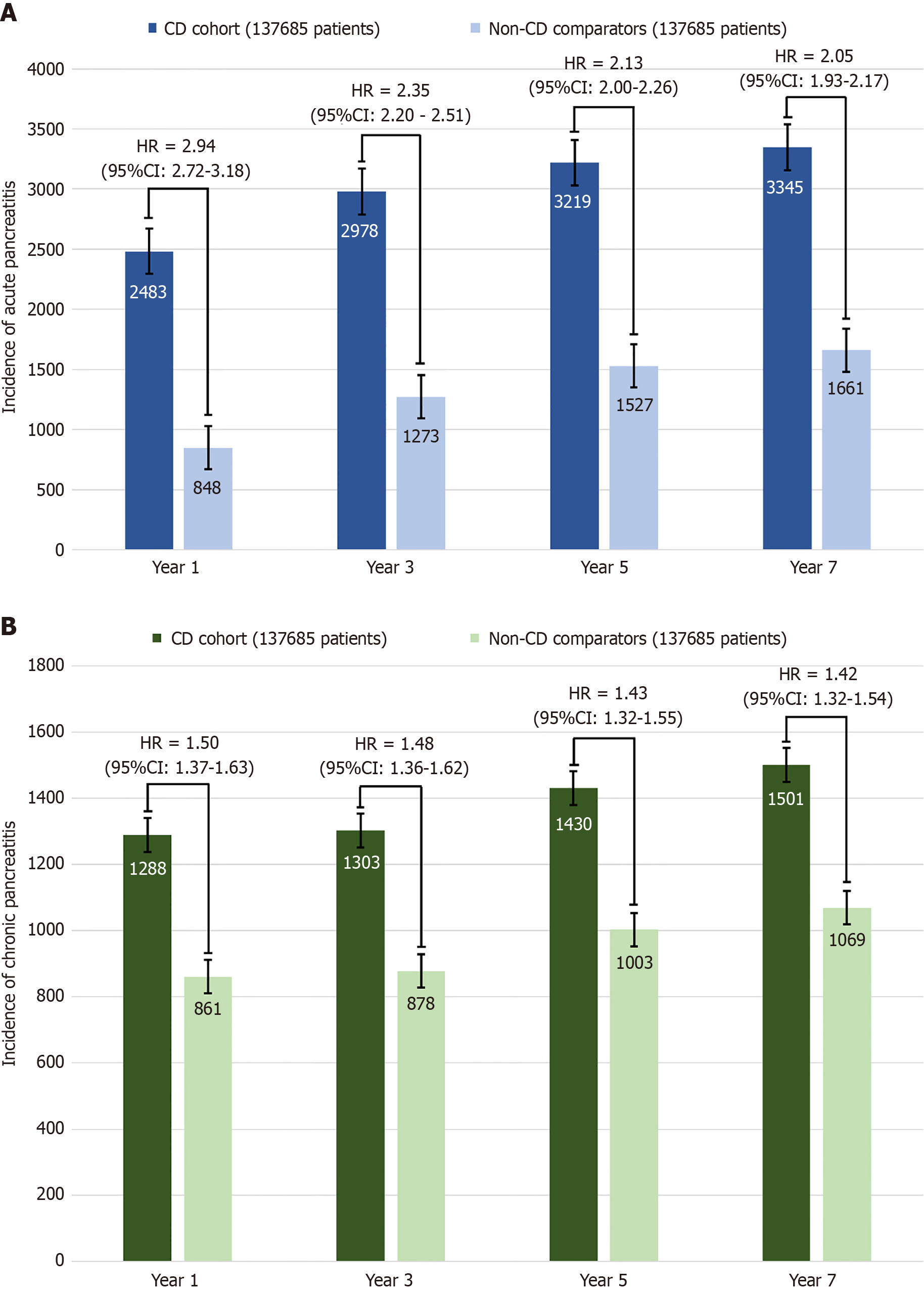

At the 1-year follow-up, 2483 CD patients and 848 non-CD patients developed AP, while 1288 CD and 861 non-CD patients developed CP Patients with CD had a significantly higher risk of AP (HR = 2.94; 95%CI: 2.72-3.18), CP (HR = 1.50; 95%CI: 1.37-1.63) (Figure 2), alcohol-induced pancreatitis (HR = 2.19; 95%CI: 1.48-3.25), biliary pancreatitis (HR = 2.10; 95%CI: 1.56-2.84), and idiopathic pancreatitis (HR = 2.62; 95%CI: 1.86-3.69) (Figure 2) compared to non-CD patients. At the 3-year follow-up, 2978 CD and 1273 non-CD patients developed AP, while 1303 CD and 878 non-CD patients developed CP In comparison to non-CD patients, CD patients continued to have a higher risk of AP (HR = 2.35; CI: 2.20-2.50), CP (HR = 1.48; CI: 1.36-1.62) (Figure 3), alcohol-induced pancreatitis (HR = 1.66; CI: 1.21-2.29), biliary pancreatitis (HR = 1.52; CI: 1.21-1.92), and idiopathic pancreatitis (HR = 1.93; CI: 1.48-2.52).

At the 5-year follow-up, 3219 CD patients and 1527 non-CD patients developed AP. 1430 CD and 1003 non-CD patients developed CP. The higher risk of AP (HR = 2.13; CI: 2.00-2.26), CP (HR = 1.43; CI: 1.32-1.55) (Figure 3), alcohol-induced pancreatitis (HR = 1.44; CI: 1.08-1.92), biliary pancreatitis (HR = 1.45; CI: 1.19-1.79), and idiopathic pancreatitis (HR = 1.67; CI: 1.33-2.10) continued in CD patients compared to non-CD patients. At the 7-year follow-up, 3345 CD and 1661 non-CD patients developed AP, while 1501 CD and 1069 non-CD patients developed CP. CD patients had a higher risk of AP (HR = 2.05; CI: 1.93-2.17), CP (HR = 1.42; CI: 1.31-1.54), alcohol-induced pancreatitis (HR = 1.35; CI: 1.03-1.77), biliary pancreatitis (HR = 1.37; CI: 1.12-1.66), and idiopathic pancreatitis (HR = 1.49; CI: 1.21-1.84) continued in CD patients compared to non-CD patients.

The findings remained robust in sensitivity analyses, which initiated follow-up one year post-CD diagnosis, thereby excluding events occurring within the first year after the index date. The HR associated with CD was comparable in magnitude to that observed in the primary analysis (Figure 3).

Our multi-institutional population-based study shows that patients with CD have a significantly higher risk of deve

Our findings are consistent with several previous studies. Autopsy studies in patients with CD exhibit pancreatic fibrosis and acinar atrophy - pathological hallmarks of CP, pointing towards a history of recurrent AP episodes, ul

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting a higher risk of AP and CP in CD patients from a large population-based dataset with a long follow-up period. Furthermore, our finding of an increased risk of alcohol-related pancreatitis among CD patients (despite accounting for common alcohol-related comorbidities, e.g., cirrhosis) has never been reported previously. Our large sample size and detailed data in TriNetX allowed for a robust analysis to detect the association between CD and pancreatitis, including a subgroup analysis. The multicenter nature of the TriNetX database facilitated a representative study population from centers across the United States, increasing the generalizability of our findings. A PSM analysis helped ensure well-matched cohorts, strengthening the validity of our findings. From a clinical and policy standpoint, these findings underscore the importance of emphasizing AP and CP prevention measures, particularly in patients newly diagnosed with or actively managing CD.

This study offers several notable strengths. It features a well-defined control group and a thorough organ-specific evaluation centered on the pancreas. Adjustments were made for a wide range of lifestyle-related risk factors, as well as baseline variables and potential confounders that could influence the observed relationship between CD and pancreatitis risk. The large sample size used in the propensity score-matched analysis contributed to narrow CIs and enabled the detection of a substantial number of outcome events, thereby reinforcing the validity of our conclusions. Additionally, the inclusion of sensitivity analyses further supports the robustness of our findings.

However, the study is not without limitations. Its retrospective nature and reliance on electronic medical record data introduce the possibility of selection bias due to documentation and coding inaccuracies. Moreover, residual confounding from factors such as alcohol consumption, smoking habits, medication use, and other lifestyle variables cannot be entirely excluded. Notably, patients included in the study, as part of their recruitment, have a new or current diagnosis of CD; therefore, our findings on the incidence and risk of pancreatic complications may not be generalizable to patients with treated CD. Given the retrospective design of this study, it was not possible to investigate the underlying pathoph

In summary, our study showed that patients with CD have a significantly increased risk of developing acute and CP, including alcohol-related, biliary, and idiopathic subtypes, over at least seven years of follow-up. These findings un

| 1. | Dieli-Crimi R, Cénit MC, Núñez C. The genetics of celiac disease: A comprehensive review of clinical implications. J Autoimmun. 2015;64:26-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Krishnan A, Hadi YB, Shabih S, Mukherjee D, Patel RA, Patel R, Singh S, Thakkar S. Risk of pancreatic cancer in individuals with celiac disease in the United States: A population-based matched cohort study. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2023;15:523-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | King JA, Jeong J, Underwood FE, Quan J, Panaccione N, Windsor JW, Coward S, deBruyn J, Ronksley PE, Shaheen AA, Quan H, Godley J, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S, Lebwohl B, Ng SC, Ludvigsson JF, Kaplan GG. Incidence of Celiac Disease Is Increasing Over Time: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:507-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 49.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rubio-Tapia A, Ludvigsson JF, Brantner TL, Murray JA, Everhart JE. The prevalence of celiac disease in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1538-44; quiz 1537, 1545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 496] [Cited by in RCA: 540] [Article Influence: 38.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Lebwohl B, Rubio-Tapia A. Epidemiology, Presentation, and Diagnosis of Celiac Disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:63-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chou R, Bougatsos C, Blazina I, Mackey K, Grusing S, Selph S. Screening for Celiac Disease: Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2017;317:1258-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Marafini I, Monteleone G, Stolfi C. Association Between Celiac Disease and Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:4155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Singh VK, Haupt ME, Geller DE, Hall JA, Quintana Diez PM. Less common etiologies of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:7059-7076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 9. | Ludvigsson JF, Montgomery SM, Ekbom A. Risk of pancreatitis in 14,000 individuals with celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1347-1353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Collin P, Reunala T, Pukkala E, Laippala P, Keyriläinen O, Pasternack A. Coeliac disease--associated disorders and survival. Gut. 1994;35:1215-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Olesen SS, Mortensen LH, Zinck E, Becker U, Drewes AM, Nøjgaard C, Novovic S, Yadav D, Tolstrup JS. Time trends in incidence and prevalence of chronic pancreatitis: A 25-year population-based nationwide study. United European Gastroenterol J. 2021;9:82-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lankisch PG, Apte M, Banks PA. Acute pancreatitis. Lancet. 2015;386:85-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 880] [Cited by in RCA: 880] [Article Influence: 80.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Sadr-Azodi O, Sanders DS, Murray JA, Ludvigsson JF. Patients with celiac disease have an increased risk for pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1136-1142.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Osagiede O, Lukens FJ, Wijarnpreecha K, Corral JE, Raimondo M, Kröner PT. Acute Pancreatitis in Celiac Disease: Has the Inpatient Prevalence Changed and Is It Associated With Worse Outcomes? Pancreas. 2020;49:1202-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Alkhayyat M, Saleh MA, Abureesh M, Khoudari G, Qapaja T, Mansoor E, Simons-Linares CR, Vargo J, Stevens T, Rubio-Tapia A, Chahal P. The Risk of Acute and Chronic Pancreatitis in Celiac Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:2691-2699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Low-Beer TS, Harvey RF, Davies ER, Read AF. Abnormalities of serum cholecystokinin and gallbladder emptying in celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:961-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wang HH, Liu M, Li X, Portincasa P, Wang DQ. Impaired intestinal cholecystokinin secretion, a fascinating but overlooked link between coeliac disease and cholesterol gallstone disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2017;47:328-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nousia-Arvanitakis S, Fotoulaki M, Tendzidou K, Vassilaki C, Agguridaki C, Karamouzis M. Subclinical exocrine pancreatic dysfunction resulting from decreased cholecystokinin secretion in the presence of intestinal villous atrophy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:307-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Patel RS, Johlin FC Jr, Murray JA. Celiac disease and recurrent pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:823-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pink IJ, Creamer B. Response to a gluten-free diet of patients with the coeliac syndrome. Lancet. 1967;1:300-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Moon SH, Kim J, Kim MY, Park do H, Song TJ, Kim SA, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. Sensitization to and Challenge with Gliadin Induce Pancreatitis and Extrapancreatic Inflammation in HLA-DQ8 Mice: An Animal Model of Type 1 Autoimmune Pancreatitis. Gut Liver. 2016;10:842-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kumar S, Gress F, Green PH, Lebwohl B. Chronic Pancreatitis is a Common Finding in Celiac Patients Who Undergo Endoscopic Ultrasound. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53:e128-e129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/