Published online Dec 16, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i35.112585

Revised: August 20, 2025

Accepted: December 10, 2025

Published online: December 16, 2025

Processing time: 138 Days and 14.2 Hours

Pituitary neuroendocrine tumors (PitNETs), formerly referred to as pituitary adenomas, are prevalent intracranial neoplasms that, although often benign histologically, can demonstrate invasive growth, therapeutic resistance, and recur

To study the molecular markers, signaling pathways, research models, and phe

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and Ovid MEDLINE in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Thirty-four studies were included based on predefined eligibility criteria. Data were extracted regarding PASC isolation methods (e.g., neurosphere formation, side population sorting), marker expression [e.g., SRY-related HMG-box transcription factor (SOX) 2, octamer-binding transcription factor 4, CD133, Nestin], pathway involvement (e.g., Wnt/beta-catenin, Notch, Sonic hedgehog), and functional behaviors such as self-renewal, differentiation, tumorigenicity, and therapy resistance.

Following duplicate removal, 315 unique articles were screened, with 47 full texts assessed for eligibility. Ultimately, 34 studies published between 2007 and 2025 met the inclusion criteria. The majority utilized human PitNET samples (83%), with a subset employing rat-derived cell lines (28%) or murine models (15%). PASCs were identified and characterized using various in vitro and in vivo approaches. Commonly reported stemness markers included SOX2 (59%), CD133 (38%), Nestin (35%), and octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (26%), with others such as SOX9, paired-like homeobox 1, and C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 also frequently cited. Wnt/beta-catenin (18%) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin (9%) signaling pathways were most implicated, followed by Notch, Sonic hedgehog, and janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription cascades. Functional assays revealed consistent findings of tumor initiation (44%), self-renewal (35%), and tumor progression or invasion (35%). Notably, a minority of studies explored therapeutic interventions targeting PASCs, including gamma-secretase inhibitors and possible novel combinations of mo

The accumulating evidence on PASCs highlights their pivotal role in PitNET tumorigenesis, progression, and therapy resistance. Their molecular and functional overlap with normal pituitary stem cells underscores the need for further lineage-tracing and in vivo validation.

Core Tip: Pituitary adenoma stem cells are a functionally distinct subpopulation within pituitary neuroendocrine tumors, exhibiting stem-like traits such as self-renewal, multipotency, and resistance to dopamine agonists and somatostatin analogs. This systematic review consolidates evidence from 34 studies, highlighting the expression of key markers like SRY-related HMG-box transcription factor 2, CD133, and Nestin, and the involvement of dysregulated pathways including Wnt/beta-catenin, Notch, Sonic hedgehog. Pituitary adenoma stem cells are implicated in tumorigenesis, invasion, and recurrence, making them compelling targets for future therapies aimed at overcoming resistance and preventing relapse in pituitary neuroendocrine tumors.

- Citation: Agosti E, Gelmini L, Panciani PP, Fiorindi A, Fontanella MM, Tengattini F, Denaro L, Gagliano C, Tognetto D, Zeppieri M. Phenotypic and functional characteristics of pituitary adenoma stem cells. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(35): 112585

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i35/112585.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i35.112585

Pituitary adenomas (PAs), now more accurately termed pituitary neuroendocrine tumors (PitNETs)[1], are among the most common intracranial neoplasms, accounting for approximately 10%-15% of all diagnosed brain tumors[2]. These epithelial-origin tumors arise from the adenohypophysis and are classified immunohistochemically based on their expression of pituitary hormones (i.e., follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, adrenocorticotropic hormone, growth hormone, prolactin, and thyroid-stimulating hormone) and the associated pituitary lineage-specific transcription factors (i.e., steroidogenic factor 1, T-box brain protein 1, and pituitary-specific transcription factor 1)[1]. Clinically, PitNETs are further characterized by their functionality. Roughly half of them are clinically non-functioning PitNETs, meaning they do not produce hormone-related symptoms despite possible immunohistochemical hormone expression[3,4]. These non-functioning tumors are typically diagnosed due to compression-related symptoms, such as visual im

The biological mechanisms underlying the development and progression of PitNETs, particularly their variable clinical behavior, remain incompletely understood. Unlike many other tumors, PitNETs are rarely associated with well-defined oncogenic mutations, although germline mutations in genes such as AIP or MEN1 have been implicated in a minority of cases[7]. Most PitNETs arise sporadically, with no clear genetic driver[8], highlighting the importance of exploring alter

The potential existence of stem-like cells within benign tumors, such as PitNETs, challenges traditional classifications and assumptions. Although benign by histological standards, many PitNETs behave in clinically aggressive ways, raising the possibility that they may harbor a stem-like subpopulation capable of initiating and sustaining tumor growth[17-18]. Supporting this, both human and murine studies have postulated the presence of adult stem cells in the normal pituitary gland, where they are believed to maintain tissue homeostasis and contribute to the plasticity of hormone-producing cells[19-21]. This has led to the hypothesis that similar populations, termed pituitary adenoma stem cells (PASCs), might also exist within adenomas and contribute to their pathophysiology[22-25].

Evidence for PASCs has emerged from various experimental approaches, including the isolation of cells expressing stem cell-associated markers such as SRY-related HMG-box transcription factor (SOX) 2, SOX9, and paired-like homeobox 1 (PROP1), particularly in non-functioning PitNETs[26-29]. Some studies have demonstrated the nuclear co-expression of these transcription factors in subpopulations of tumor cells, suggesting a potential stem-like phenotype[30-33]. Advanced techniques such as single-cell RNA sequencing have further revealed overlapping transcriptomic signatures between normal pituitary stem cells and cells found in adenomas[34-36]. However, whether these cells directly give rise to tumor cells or exert their influence via paracrine mechanisms remains under debate.

Despite growing interest, our understanding of the role of PASCs in pituitary tumorigenesis remains limited. The identification and characterization of these cells have been hindered by the heterogeneity of experimental models and methodologies, and there remains no consensus on definitive markers or functional assays. Moreover, the precise contribution of PASCs to tumor initiation, progression, therapeutic resistance, and recurrence is yet to be clearly delineated. Given these gaps in knowledge, this systematic review aims to critically evaluate the current literature on PASCs, with a focus on their phenotypic features, proposed roles in tumorigenesis, and potential implications for diagnosis and therapy.

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Two reviewers (Agosti E and Gelmini L) independently performed a comprehensive search of the PubMed, Scopus, and Ovid MEDLINE databases. The initial search was conducted on March 21, 2025, with a final update on June 20, 2025. The search strategy employed combinations of keywords and MeSH terms related to pituitary tumors and stem cells, including: “Pituitary Neoplasms” (Mesh), “pituitary adenoma”, “PitNETs”, “Stem Cells”, “stem cells”, “cancer stem cells”, “CSCs”, “pituitary adenoma stem cells”, “PASCs”, “tumorigenesis”, “self-renewal”, “cell proliferation”, “invasion”, “aggressiveness”, “pathway”, “drug resistance”, “drug sensitivity”, “treatment response”, “therapeutic resistance”, and “outcome”. Boolean operators were used to construct the following query: (“Pituitary Neoplasms” OR “pituitary adenoma” OR “PitNETs”) AND (“Stem Cells” OR “stem cells” OR “cancer stem cells” OR “CSCs”) OR “pituitary adenoma stem cells” OR “PASCs”) AND (“tumorigenesis” OR “self-renewal” OR “cell proliferation” OR “invasion” OR “aggressiveness” OR “pathway” OR “drug resistance” OR “drug sensitivity” OR “treatment response” OR “therapeutic resistance” OR “outcome”). Specific search strings used for databases are available in Supplementary material. Additional relevant articles were identified through manual screening of the references of included studies.

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) Published in English; (2) Contained original experimental or clinical data; (3) Focused on the identification, characterization, or functional role of PASCs or stem-like cells in PitNETs; and (4) Investigated their association with key tumorigenic features such as proliferation, invasion, recurrence, drug resistance, or treatment outcomes. Studies were excluded if they were review articles, editorials, conference abstracts, non-English publications, or if they lacked sufficient detail on methodology or findings relevant to PASCs. All citations were managed using EndNote X9, and duplicates were removed prior to screening. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers (Agosti E and Gelmini L), and discrepancies were resolved through consensus with a third reviewer (Panciani PP). Full-text review was performed for all studies meeting the initial inclusion criteria.

Data were systematically extracted from each eligible study using a standardized data collection template. The following variables were recorded: (1) Cell lines (in vitro or patient-derived models used); (2) Identification markers (molecular or phenotypic markers used to define stem-like cells, e.g., SOX2, SOX9, PROP1); (3) Pathways (associated signaling pathways or gene networks, e.g., Wnt, Notch, Hedgehog); (4) Molecular agents (biomolecular agent investigated, pharmacological compounds or biological inhibitors used in the studies); and (5) Effects on tumor behavior (e.g., self-renewal, invasion, proliferation, therapeutic resistance).

The primary outcome was to synthesize and critically evaluate the current evidence on the existence, identification, and functional role of PASCs in the context of PitNET tumorigenesis. Secondary outcomes included the characterization of associated signaling pathways, identification of key stem cell markers, assessment of tumorigenic potential (e.g., self-renewal, invasion), and responsiveness to targeted molecular agents or conventional therapies. The goal was to assess the biological and clinical relevance of PASCs as potential drivers of tumor initiation, progression, and treatment failure, thereby identifying novel diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets.

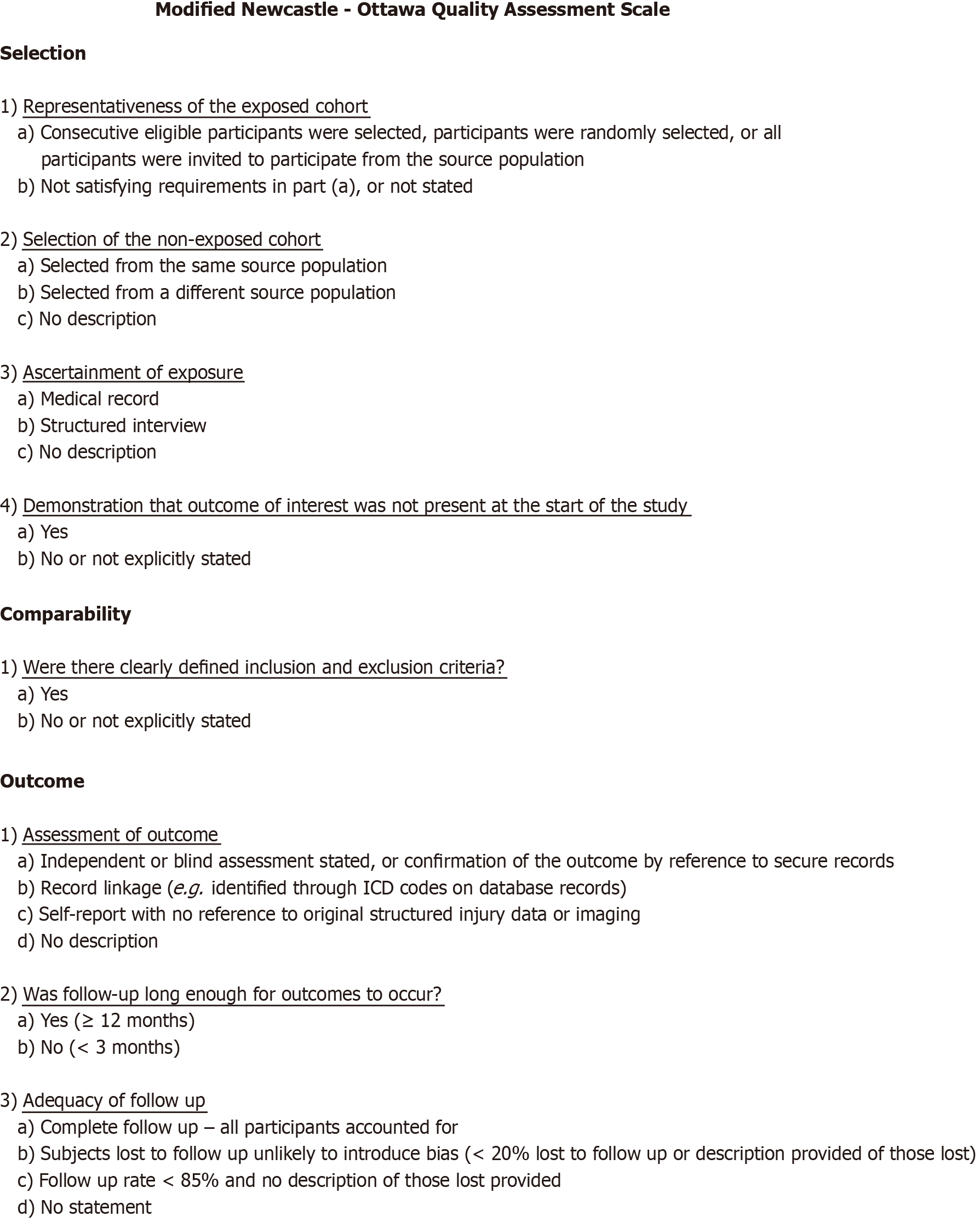

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was employed to assess the methodological quality of the included observational and experimental studies (Figure 1). The NOS evaluates studies based on three domains: Selection, comparability, and outcome assessment, with a maximum score of nine points. Studies scoring less than seven were of low quality and excluded from quantitative synthesis, although key findings from all eligible studies were included in the qualitative analysis and narrative discussion. Specific NOS scores for each study are listed in Supplementary material.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize findings across studies, including trends in marker expression, pathway involvement, and treatment effects. Data were presented in tabular and narrative form. All data processing and visual representation were carried out using R statistical software (version 4.2.0).

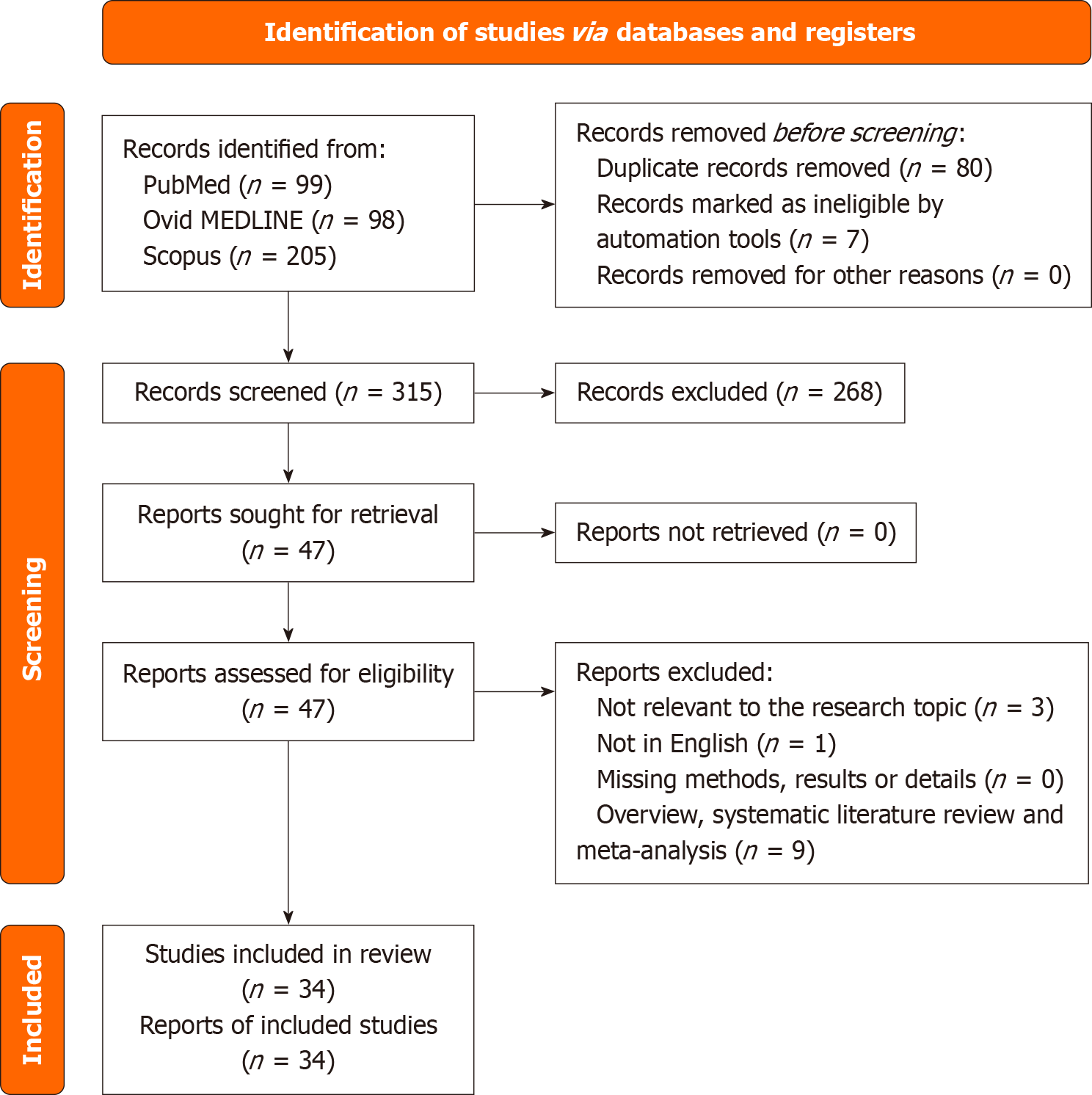

Following the removal of duplicates, 315 unique articles were identified. Screening of titles and abstracts narrowed this down to 47 articles for full-text review. Of these, 34 met the inclusion criteria. Thirteen studies were excluded due to the following reasons: Lack of relevance to the research question (3 articles), not in English (1 article), and being review or meta-analysis publications (9 articles). All included studies reported at least one relevant outcome for one or more patient cohorts. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses -compliant flow diagram summarizing the selection process is presented in Figure 2.

A total of 34 studies, published between 2007 and 2025, were included in this systematic review. Various in vitro and in vivo models were used, with human PA samples being the most common (28 studies, 83%), followed by rat-derived cell lines such as MMQ and GH3 (8 studies, 28%) and mouse PA cell lines like AtT-20 (5 studies, 15%). Several studies used more than one model. In terms of identification markers, a wide range of stemness-related and lineage-associated markers were reported. The most frequently cited were SOX2 (19 studies, 59%), CD133 (13 studies, 38%), Nestin (11 studies, 35%), and octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (OCT4) (9 studies, 26%). Other recurrent markers included SOX9 (4 studies, 12%) and NANOG (3 studies, 8%). Additional markers investigated were S100β and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor family receptor alpha 2 (GFRa2), each reported in 2 studies (6%). These markers were typically identified through immunohistochemistry, quantitative polymerase chain reaction, or flow cytometry-based methods to characterize PASCs in functional and non-functional adenomas.

Regarding signaling pathways, Wnt/beta-catenin signaling was the most frequently involved (6 studies, 18%), followed by phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/AKT/mTOR) (3 studies, 9%), while Notch, SHH (Sonic Hedgehog), and Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathways were each reported in 2 studies (6%). Additional pathways included HIPPO, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), nuclear factor kappaB, transforming growth factor-beta/bone morphogenetic protein, and histone methylation, reflecting the broad molecular heterogeneity of PASCs. In terms of molecular agents, SOX2 itself was cited not only as a marker but also as a molecular target in 4 studies (12%), while others explored agents such as delta-like non-canonical Notch ligand 1, GFRa2, sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1, lysine methyltransferase 5A, and developmental pluripotency associated 4. Notably, dopamine agonists and somatostatin analogs were explored in 6 studies (18%). Three studies proposed potential therapies: One tested gamma-secretase inhibitors to block Notch signaling, while two studies proposed combined therapies to increase therapeutic response.

Species variations have constituted a significant source of heterogeneity in PASC research. Although some markers, including SOX2, OCT4, and Nestin, have been reliably identified in both human and rodent PitNET samples, some molecules exhibit species-specific expression or differing functional roles. CD133 serves as a consistent stemness marker in human PitNETs; however, its expression varies in murine models, possibly indicating disparities in pituitary embryology. Similarly, GFAP expression has been more pronounced in mouse folliculo-stellate cell-derived niches compared to human malignancies. The disparities emphasize the necessity for meticulous interpretation when ex

Concerning effects on tumor behavior, tumorigenesis or tumor initiation were the most frequently reported phenotypes (15 studies, 44%), followed by self-renewal (12 studies, 35%), tumor progression or invasion (12 studies, 35%), and chemoresistance (4 studies, 12%). Recurrence, EMT, and angiogenesis were also noted as functional consequences in a smaller subset of studies. Multiple studies confirmed that PASCs may contribute to therapy resistance, support tumor regrowth post-treatment, or influence the tumor microenvironment via paracrine signaling (Table 1)[23-60].

| Ref. | Cell lines | Identification marker | Pathway | Molecular agent | Effects on tumor behavior |

| Yokoyama et al[37], 2007 | MtT/S and MtT/E cells derived from rat prolactinoma | NA | GH-IGF1 | IGF-1 | Paracrine IGF-1 from GH+ cells promotes progenitor proliferation |

| Xu et al[23], 2009 | Human PA samples | Nestin, CD133 | NA | NA | Tumorigenesis, self-renewal, chemoresistance |

| Yunoue et al[24], 2011 | Human PA samples | CD133 | NA | CD133, CD34, VEGFR2, nestin | CD133+ cells are implicated as endothelial progenitors in PAs |

| Ma et al[38], 2013 | Human PA samples | NA | Nucleostemin-p53; ASPP2-p53 | Nucleostemin and ASPP2 | Tumorigenesis, tumor progression, self-renewal |

| Zhao et al[39], 2015 | Human PA samples | Nestin, CD133 | NA | NA | Sphere-formation, self-renewal, chemoresistance |

| Mathioudakis et al[40], 2015 | Human PA samples | GFRa2 | GFRa2-RET | GFRa2 | Tumorigenesis |

| Lampichler et al[30], 2015 | Human PA samples; mouse pituitary adenoma cell line AtT-20 | SOX2, TP53, MKI67, SOD1 | Hh signaling | GLI1 | Tumorigenesis |

| Manoranjan et al[31], 2016 | Human PA samples | CD15, CD133, SOX2 | NA | Pax7, SOX2 | Tumorigenesis, self-renewal, tumor progression |

| Peverelli et al[32], 2017 | Human PA samples | SOX2, POU5F1/OCT4, KLF4 and EGR1 | DRD2 and SSTR2 associated inhibitory pathways | DA, SSA | Sphere-formation, tumor proliferation and invasion of CS |

| Mezzomo et al[41], 2017 | Human PA samples | Underexpressed TP63 isoforms (TAp63, ∆Np63) | NA | NA | Tumorigenesis, tumor progression |

| Orciani et al[42], 2017 | Human PA samples | OCT4, NANOG, KLF4, SOX2, TGFbRII, E-CADHERIN | EMT, Somatostatin signaling | SST, SSA | EMT |

| Gao et al[43], 2017 | MMQ cells (rat), human PA samples | CD133, Nestin, OCT4, SOX2, D2R | D2R | DA | DA resistance |

| Würth et al[27], 2017 | Human PA samples | SOX2, Oct4, CD133, Nestin, NANOG. | SSTR2, SSTR5, D2R | Somatostatin/dopamine chimera BIM-23A760 | Tumorigenesis, self-renewal, angiogenesis |

| Horiguchi et al[44], 2018 | Rat anterior pituitary CD9+ cells | CD9, SOX2, S100β | BMP signaling | NA | Self-renewal |

| Tamura et al[45], 2019 | Human PA samples | PITX2, SNAIL1 | NA | PITX2 | Tumor progression, invasion of CS |

| Tang et al[26], 2019 | HP75 cells | SOX2 | Wnt/beta-catenin, SHH | SOX2 | Tumor proliferation |

| Zubeldía-Brenner et al[46], 2019 | GH3 (rat) | NA | Notch | γ-secretase inhibitor (Notch blockade) | Sphere-formation |

| Soukup et al[47], 2020 | Human PA samples | SOX2 | NA | SOX2 | NA |

| Taniguchi-Ponciano et al[48], 2020 | Human PA samples | NR5A1, TBX19, POU1F1 | NA | NA | Tumorigenesis |

| Cai et al[49], 2021 | MMQ cells (rat) | CD133, Nestin, HCAM, OCT4, SCA1 | D2R | CD133 | DA resistance |

| Chen et al[50], 2020 | Human PA samples, GH3 (rat), MMQ cells (rat), mouse pituitary adenoma cell line AtT-20 | DLK1/MEG3 | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | DLK1 | Tumorigenesis, self-renewal, tumor progression, angiogenesis |

| Guido et al[33], 2021 | Rat (F344) | GFRa2, SOX2, SOX9, Nestin, CD133, CD44 | NA | NA | Self-renewal |

| Xiao et al[51], 2021 | Human PA samples, MMQ cells (rat) | CD133, Nestin, SOX2S | JAK2/STAT5 | DA, Pimozine | Tumorigenesis, DA resistance |

| Nys et al[52], 2022 | Human PA samples, Mouse PA samples (DRD2-/-) | SOX2, SOX9, TACSTD, KRT8, KRT18 | NF-κB, IFN-γ, JAK/STAT | IL-6 | Tumorigenesis |

| Saksis et al[53], 2023 | GH3 (rat), Human PA samples | OCT4, CD133, Nestin, SOX2, CXCR4 | NA | NA | Self-renewal, chemoresistance |

| Yuan et al[54], 2023 | Human PA samples | SOX2, OCT4, Nestin, CD133 | NA | ANXA2 | Tumorigenesis, self-renewal, angiogenesis |

| Zhang et al[34], 2023 | Human PA samples | SOX2, S100β, SOX9, VIM, CLDN4 | NA | SREBF1 | Tumorigenesis, recurrence |

| Li et al[55], 2024 | Human PA samples, GH3 (rat). | NA | Wnt/beta-catenin | KMT5A | Apoptosis, tumor progression |

| Jotanovic et al[56], 2024 | Human PA samples | NA | NF-κB, WnT/EMT, mTOR | NA | Bone invasion, tumor progression |

| Øystese et al[29], 2024 | Human PA samples | SOX2, SOX9, PROP1 | Wnt/beta-catenin, Notch, FGF, SHH, TGF- β/BMP | SOX2, SOX9, PROP1 | Self-renewal |

| Lenders et al[57], 2024 | Human PA samples | SF-1, PIT-1, T-PIT, SOX2, Nestin, CD133 | NA | NA | Tumorigenesis of WLDL tumors |

| Peng et al[58], 2024 | Human PA samples | Nestin, CD133, SOX2, OCT4 | PI3K/Akt, Wnt/beta-catenin, calcium signaling, cAMP signaling, RAS | NA | Tumorigenesis, self-renewal, chemoresistance |

| Lang et al[59], 2025 | Human PA samples | PIT-1, CK8/18 | NA | NA | Tumor progression |

| Chaudhary et al[60], 2025 | Human and mouse PA samples | DPPA4, SOX2, OCT4, NANOG | Wnt/beta-catenin, Histone methylation | DPPA4 | Tumor progression, cell migration, EMT |

The systematic review provides a comprehensive synthesis of 34 studies that collectively highlight the relevance of PASCs in the context of PitNETs. These findings confirm that PASCs are not only identifiable within both functional and non-functional PAs but also actively participate in critical processes such as self-renewal, tumorigenesis, resistance to therapy, and recurrence. The reviewed studies underscore the complexity of PitNET biology, challenging traditional perceptions of these tumors as merely benign and emphasizing the necessity to address PASCs when considering therapeutic strategies.

One of the pivotal aspects of the review is the extensive profiling of stemness-related markers in PASCs. Xu et al[23] and Zhao et al[39] identified Nestin and CD133 as key markers associated with PASCs, supporting their self-renewing capacity and resistance to conventional treatments. Similarly, studies by Würth et al[27] and Chen et al[50] confirmed the expression of OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG in sphere-forming cells isolated from PitNETs, aligning with the phenotypic characteristics of CSCs found in other tumor types. The presence of SOX2+ cells emphasizes the potential overlap between normal pituitary stem cells and tumorigenic PASCs. This connection is reinforced by the discovery that GPS cells express GFRa2, RET, and PROP1 in both human and murine models[61]. Interestingly, CD133 and C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4), as reported by Yunoue et al[24], were found predominantly in aggressive tumor subtypes, suggesting a correlation between marker expression and tumor invasiveness.

In our statistical synthesis, the frequency of molecular citations has been utilized as an indicator of research interest rather than a direct assessment of biological significance. We have stated that citation proportion corresponds to the quantity of existing research, but the extent of molecular function is contingent upon the particular assays and models utilized. For instance, SOX2 has undergone functional validation using clonogenic assays and tumorigenicity models, while other molecules like CD44 have predominantly been shown in descriptive immunohistochemistry studies. We have analyzed the quantitative distribution of molecules within the framework of methodological background and experimental validation, advising against excessive interpretation of frequency statistics in isolation.

PASCs demonstrate hallmark properties of stem cells, including the ability to form neurospheres, a key indicator of self-renewal. As shown by Ma et al[38], these spheres not only proliferate but also exhibit multilineage differentiation potential, indicating a multipotent phenotype. Würth et al[27] further substantiated the functional potential of PASCs through in vivo models, including xenografts in mice and zebrafish, where selected cells initiated tumor growth. Of note is the evidence that PASCs, like their glioma counterparts described by Bao et al[62] and Nadkarni et al[63], display chemoresistance. This parallels findings from the broader literature on CSCs and resistance mechanisms, as reported by Zhao et al[39], Manoranjan et al[31], and Carreno et al[64], who demonstrated that CD133+ cells were particularly recalcitrant to standard treatments.

The review also highlights the aberrant activation of key developmental pathways in PASCs, such as Wnt/beta-catenin, Notch, and SHH, all of which are crucial for stem cell maintenance and differentiation. As noted by Würth et al[27] and Caffarini et al[65], elevated expression of Notch receptors and ligands (e.g., Notch1-4, Jagged1) was detected in PASC populations. This is consistent with studies by Ulasov et al[66] in glioblastoma models, where Notch signaling inhibition decreased tumorigenic potential. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling, extensively characterized by Chen et al[50], plays a pivotal role in sustaining stemness and promoting PASC-mediated tumor growth. The SHH pathway, emphasized by Orciani et al[42], was similarly implicated, with dysregulation promoting proliferation and survival of stem-like cells. These findings resonate with broader developmental biology studies by Øystese et al[29] and Cai et al[49], which underscore the involvement of these pathways in normal pituitary development and maintenance.

The EMT has emerged as a hallmark of cancer progression and metastasis, and its activation in PASCs may signify enhanced motility and invasiveness. Chaudhary et al[60], Jotanovic et al[56], and Orciani et al[42] reported upregulation of EMT markers such as zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1, twist family bHLH transcription factor 1, and snail family transcriptional repressor 2 inside populations of PASCs, suggesting that these cells possess mesenchymal features conducive to migration and invasion. These results mirror those of Hide et al[67] in glioma models, where stem-like cells contributed to tumor microenvironment remodeling and resistance. The expression of chemoresistance-associated markers in PASCs, including Nestin as discussed by Saksis et al[53] and Xiao et al[51], further illustrates their ability to evade standard cytotoxic therapies. Moreover, Øystese et al[29] and Yuan et al[54] reported the expression of DNA repair proteins and anti-apoptotic markers in PASCs, indicating an intrinsic resilience that contributes to tumor recurrence.

The interaction between PASCs and the tumor microenvironment is another focal point of the review. As demonstrated by Nys et al[52] and Kuwajima et al[25], PASCs are capable of reprogramming surrounding stromal and immune cells to support tumorigenesis. This crosstalk, involving pathways such as PI3K/AKT/mTOR and the CXCR4/C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 axis, mirrors the interactions observed in glioma models and described by Liu et al[68] wherein GSCs recruit tumor-associated macrophages to enhance survival and therapy resistance. The studies by Yunoue et al[24] and Vamvoukaki et al[69] affirm the relevance of the C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12/CXCR4 system in PAs, correlating with increased invasiveness and proliferation. Moreover, the role of RET/pituitary-specific positive transcription factor 1/Arf/p53 signaling in regulating cell turnover, proposed by Garcia-Lavandeira et al[70], introduces an additional layer of control that may influence PASCs’ behavior and persistence.

The identification of PASCs opens avenues for the development of targeted therapies aimed at eradicating the tu

Cellular heterogeneity is an inherent characteristic of PitNETs, notably pronounced in the stem-like compartment. The emergence of single-cell transcriptomic and proteomic methodologies has revealed that PASCs express a diverse range of stemness-associated markers. Nevertheless, not all of these compounds possess equivalent biological significance. Functional validation has identified molecules such as SOX2, OCT4, and NANOG as primary regulators of self-renewal and multipotency, while others, such as CD133 and Nestin, have functioned as supplementary markers of stem-like populations. Prioritizing markers with established causative roles in tumor development and resistance, rather than those with merely correlative expression, has thus become a crucial step for future translational investigations and therapeutic targeting.

Regarding dopamine agonists and somatostatin analogs therapeutic effects, there was no complete agreement among the studies investigating this issue: While Orciani et al[42], Peverelli et al[32], and Würth et al[27] found PASCs’ sensitivity to dopamine agonists and somatostatin analogues (SST), Gao et al[43], Xiao et al[51], and Cai et al[49], demonstrated dopamine agonists resistance. Concerning possible new therapeutic strategies, Xiao et al[51] proposed the combination of pimozide and bromocriptine as a novel therapeutic strategy. In the current therapeutic landscape for PitNETs, various contemporary clinical datasets have established definitive foundations for implementing PASC-relevant pathways in practice. In acromegaly, once-daily oral paltusotine, a selective SST2 agonist, has sustained biochemical and symptomatic control following a transition from injectable somatostatin receptor ligands, as demonstrated in a peer-reviewed phase 3 study. It has also exhibited rapid and enduring responses in supplementary phase 3/extension presentations, thereby facilitating somatostatin-axis suppression in a convenient oral format that may enhance the prolonged pathway mo

Similarly, oral octreotide capsules have received approval for long-term maintenance medication and have shown sustained efficacy and positive patient-reported outcomes, thereby reinforcing the viability of chronic SST signaling regulation in suitable patients[75-77]. Long-term studies of osilodrostat in Cushing’s disease have resulted in the normalization of cortisol biomarkers and concomitant enhancements in clinical outcomes. Pooled and extension reports have bolstered the evidence for sustained steroidogenesis inhibition, establishing a foundation for logical combinations that simultaneously target survival and stress-response pathways involved in PASC, such as PI3K/AKT/mTOR and janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription. The selective glucocorticoid receptor modulator relacorilant has achieved its primary endpoint in the randomized-withdrawal phase 3 Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment study, with reports from the company, congress, and trial registry indicating significant cardiometabolic advantages and regulatory advancement, thereby facilitating the mitigation of GR-driven stemness programs in combination strategies[78].

Collectively, these advancements have established a readily implementable framework for prospective testing of PASC-directed interventions (e.g., gamma-secretase/Notch, Wnt/HH, or PI3K/AKT/mTOR modulators) alongside conventional endocrine therapies, with biomarker enrichment (SOX2/CD133 expression, EMT-skewed signatures) suggested to enhance translational efficacy. To consolidate the various components examined in this study, Table 2 provides a conceptual summary that categorizes the markers, models, pathways, phenotypes, and translational targets of PASC in PitNETs. This synthesis aims to provide readers with a clear framework that highlights the interaction between fundamental molecular mechanisms and novel clinical applications.

| Domain | Key elements | Representative examples/notes | Translational implications |

| Markers of stemness | Transcription factors; surface markers | SOX2, OCT4, NANOG; CD133, Nestin | Facilitate the identification of PASC and the prospective categorization of patients based on biomarkers |

| Experimental models | In vitro; in vivo; ex vivo | Sphere-forming assays, organoids, xenografts | Simulate tumor-propagating cell dynamics and evaluate pathway inhibitors |

| Signaling pathways | Core developmental cascades | Wnt/beta-catenin, Notch, SHH-GLI, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, JAK/STAT | Facilitate self-renewal, plasticity, invasion, and therapeutic resistance |

| Associated phenotypes | Cellular functions | Self-renewal, multipotency, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), drug resistance | Phenotypic characteristics of aggressive PitNETs |

| Therapeutic targets | Current and emerging strategies | Somatostatin receptor ligands (SRLs), dopamine agonists, temozolomide, PRRT; experimental Notch or Wnt inhibitors | Integrate endocrine regulation with therapies aimed at stemness |

| Clinical context | Disease entities and therapies | Acromegaly: Oral SST2 agonist paltusotine, oral octreotide capsules; Cushing’s: Osilodrostat, relacorilant; Aggressive PitNETs: TMZ, PRRT, ICIs | Exhibit the expanding translational pipeline and justification for combinatorial approaches |

The therapeutic application of PASC indicators remains in its early stages; however, the systematic assessment of their phenotypic and functional significance has established a crucial foundation for translational research. We have hi

First, significant heterogeneity exists among the included studies in terms of experimental models, PASC isolation techniques, and marker panels used for characterization, which limits the comparability and generalizability of findings. Second, many studies relied on in vitro assays without validating tumorigenic potential through robust in vivo models, which remains the gold standard for defining true CSC behavior. Third, a lack of standardized definitions and functional assays for PASCs introduces ambiguity in the interpretation of their stem-like properties. Additionally, the predominance of non-randomized, small-sample observational studies increases the risk of bias and overestimation of effects. Lastly, most available data are derived from non-functioning PitNETs or growth-hormone-secreting pituitary adenomas, with limited representation of other PitNET subtypes, thereby constraining the scope of conclusions across the full spectrum of PAs.

PASCs embody a critical component of PitNET biology, contributing to tumorigenesis, therapeutic resistance, and recurrence. Their characterization aligns with findings from both human and animal models and is supported by complementary evidence from developmental biology and CSC research. Future strategies must integrate our growing understanding of PASCs into clinical practice, aiming to disrupt their niche and molecular circuitry to achieve sustained tumor control and improved patient outcomes.

| 1. | Asa SL, Mete O, Perry A, Osamura RY. Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of Pituitary Tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2022;33:6-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 357] [Article Influence: 89.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ezzat S, Asa SL, Couldwell WT, Barr CE, Dodge WE, Vance ML, McCutcheon IE. The prevalence of pituitary adenomas: a systematic review. Cancer. 2004;101:613-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 821] [Cited by in RCA: 887] [Article Influence: 40.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Agustsson TT, Baldvinsdottir T, Jonasson JG, Olafsdottir E, Steinthorsdottir V, Sigurdsson G, Thorsson AV, Carroll PV, Korbonits M, Benediktsson R. The epidemiology of pituitary adenomas in Iceland, 1955-2012: a nationwide population-based study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173:655-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Tjörnstrand A, Gunnarsson K, Evert M, Holmberg E, Ragnarsson O, Rosén T, Filipsson Nyström H. The incidence rate of pituitary adenomas in western Sweden for the period 2001-2011. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;171:519-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | AlMalki MH, Ahmad MM, Brema I, AlDahmani KM, Pervez N, Al-Dandan S, AlObaid A, Beshyah SA. Contemporary Management of Clinically Non-functioning Pituitary Adenomas: A Clinical Review. Clin Med Insights Endocrinol Diabetes. 2020;13:1179551420932921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Casar-Borota O, Burman P, Lopes MB. The 2022 WHO classification of tumors of the pituitary gland: An update on aggressive and metastatic pituitary neuroendocrine tumors. Brain Pathol. 2025;35:e13302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Melmed S. Pituitary-Tumor Endocrinopathies. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:937-950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 66.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Spada A, Mantovani G, Lania AG, Treppiedi D, Mangili F, Catalano R, Carosi G, Sala E, Peverelli E. Pituitary Tumors: Genetic and Molecular Factors Underlying Pathogenesis and Clinical Behavior. Neuroendocrinology. 2022;112:15-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Skvortsova I. Cancer Stem Cells: What Do We Know about Them? Cells. 2021;10:1528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nassar D, Blanpain C. Cancer Stem Cells: Basic Concepts and Therapeutic Implications. Annu Rev Pathol. 2016;11:47-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 677] [Cited by in RCA: 622] [Article Influence: 62.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Agosti E, Antonietti S, Ius T, Fontanella MM, Zeppieri M, Panciani PP. Glioma Stem Cells as Promoter of Glioma Progression: A Systematic Review of Molecular Pathways and Targeted Therapies. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:7979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim JK, Jeon HY, Kim H. The molecular mechanisms underlying the therapeutic resistance of cancer stem cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2015;38:389-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Akbar Samadani A, Keymoradzdeh A, Shams S, Soleymanpour A, Elham Norollahi S, Vahidi S, Rashidy-Pour A, Ashraf A, Mirzajani E, Khanaki K, Rahbar Taramsari M, Samimian S, Najafzadeh A. Mechanisms of cancer stem cell therapy. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;510:581-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lathia JD, Liu H. Overview of Cancer Stem Cells and Stemness for Community Oncologists. Target Oncol. 2017;12:387-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Agosti E, Zeppieri M, Ghidoni M, Ius T, Tel A, Fontanella MM, Panciani PP. Role of glioma stem cells in promoting tumor chemo- and radioresistance: A systematic review of potential targeted treatments. World J Stem Cells. 2024;16:604-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Muzyka L, Goff NK, Choudhary N, Koltz MT. Systematic Review of Molecular Targeted Therapies for Adult-Type Diffuse Glioma: An Analysis of Clinical and Laboratory Studies. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:10456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Vankelecom H. Non-hormonal cell types in the pituitary candidating for stem cell. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:559-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Vankelecom H. Stem cells in the postnatal pituitary? Neuroendocrinology. 2007;85:110-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pérez Millán MI, Cheung LYM, Mercogliano F, Camilletti MA, Chirino Felker GT, Moro LN, Miriuka S, Brinkmeier ML, Camper SA. Pituitary stem cells: past, present and future perspectives. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2024;20:77-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Florio T. Adult pituitary stem cells: from pituitary plasticity to adenoma development. Neuroendocrinology. 2011;94:265-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mariniello K, Ruiz-Babot G, McGaugh EC, Nicholson JG, Gualtieri A, Gaston-Massuet C, Nostro MC, Guasti L. Stem Cells, Self-Renewal, and Lineage Commitment in the Endocrine System. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | de Almeida JP, Sherman JH, Salvatori R, Quiñones-Hinojosa A. Pituitary stem cells: review of the literature and current understanding. Neurosurgery. 2010;67:770-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Xu Q, Yuan X, Tunici P, Liu G, Fan X, Xu M, Hu J, Hwang JY, Farkas DL, Black KL, Yu JS. Isolation of tumour stem-like cells from benign tumours. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:303-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yunoue S, Arita K, Kawano H, Uchida H, Tokimura H, Hirano H. Identification of CD133+ cells in pituitary adenomas. Neuroendocrinology. 2011;94:302-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kuwajima A, Abe T, Tanioka D, Sasaki A, Yamamoto T, Tachikawa T. Genetic analysis of stem cell-specific markers in pituitary adenomas. J Showa Med Assoc. 2011;71:84-91. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Tang J, Chen L, Wang Z, Huang G, Hu X. SOX2 mediates crosstalk between Sonic Hedgehog and the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway to promote proliferation of pituitary adenoma cells. Oncol Lett. 2019;18:81-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Würth R, Barbieri F, Pattarozzi A, Gaudenzi G, Gatto F, Fiaschi P, Ravetti JL, Zona G, Daga A, Persani L, Ferone D, Vitale G, Florio T. Phenotypical and Pharmacological Characterization of Stem-Like Cells in Human Pituitary Adenomas. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:4879-4895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Würth R, Thellung S, Corsaro A, Barbieri F, Florio T. Experimental Evidence and Clinical Implications of Pituitary Adenoma Stem Cells. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Øystese KA, Olarescu NC, Lindskog C, Xheka F, Berg-Johnsen J, Berg JP, Bollerslev J, Casar-Borota O. Stem cell-associated transcription factors in non-functioning pituitary neuroendocrine tumours. Free Neuropathol. 2024;5:5-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lampichler K, Ferrer P, Vila G, Lutz MI, Wolf F, Knosp E, Wagner L, Luger A, Baumgartner-Parzer S. The role of proto-oncogene GLI1 in pituitary adenoma formation and cell survival regulation. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2015;22:793-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Manoranjan B, Mahendram S, Almenawer SA, Venugopal C, McFarlane N, Hallett R, Vijayakumar T, Algird A, Murty NK, Sommer DD, Provias JP, Reddy K, Singh SK. The identification of human pituitary adenoma-initiating cells. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2016;4:125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Peverelli E, Giardino E, Treppiedi D, Meregalli M, Belicchi M, Vaira V, Corbetta S, Verdelli C, Verrua E, Serban AL, Locatelli M, Carrabba G, Gaudenzi G, Malchiodi E, Cassinelli L, Lania AG, Ferrero S, Bosari S, Vitale G, Torrente Y, Spada A, Mantovani G. Dopamine receptor type 2 (DRD2) and somatostatin receptor type 2 (SSTR2) agonists are effective in inhibiting proliferation of progenitor/stem-like cells isolated from nonfunctioning pituitary tumors. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:1870-1880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Guido CB, Sosa LDV, Perez PA, Zlocoswki N, Velazquez FN, Gutierrez S, Petiti JP, Mukdsi JH, Torres AI. Changes of stem cell niche during experimental pituitary tumor development. J Neuroendocrinol. 2021;33:e13051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Zhang Q, Yao B, Long X, Chen Z, He M, Wu Y, Qiao N, Ma Z, Ye Z, Zhang Y, Yao S, Wang Y, Cheng H, Chen H, Ye H, Wang Y, Li Y, Chen J, Zhang Z, Guo F, Zhao Y. Single-cell sequencing identifies differentiation-related markers for molecular classification and recurrence prediction of PitNET. Cell Rep Med. 2023;4:100934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Su W, Ye Z, Liu J, Deng K, Liu J, Zhu H, Duan L, Shi C, Wang L, Zhao Y, Gong F, Zhang Y, Hou B, You H, Feng F, Ling Q, Xiao Y, Guo Y, Fan W, Zhang S, Zhang Z, Hu X, Yao Y, Zheng C, Lu L. Single-cell and spatial transcriptome analyses reveal tumor heterogeneity and immune remodeling involved in pituitary neuroendocrine tumor progression. Nat Commun. 2025;16:5007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Cui Y, Li C, Jiang Z, Zhang S, Li Q, Liu X, Zhou Y, Li R, Wei L, Li L, Zhang Q, Wen L, Tang F, Zhou D. Single-cell transcriptome and genome analyses of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23:1859-1871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Yokoyama K, Mogi C, Miura K, Kuroda K, Inoue K. Somatotropes maintain their immature cells through Insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I). Endocr Pathol. 2007;18:174-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ma L, Chen ZM, Li XY, Wang XJ, Shou JX, Fu XD. Nucleostemin and ASPP2 expression is correlated with pituitary adenoma proliferation. Oncol Lett. 2013;6:1313-1318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Zhao Y, Xiao Z, Chen W, Yang J, Li T, Fan B. Disulfiram sensitizes pituitary adenoma cells to temozolomide by regulating O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase expression. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:2313-2322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Mathioudakis N, Sundaresh R, Larsen A, Ruff W, Schiller J, Guerrero-Cázares H, Burger P, Salvatori R, Quiñones-Hinojosa A. Expression of the pituitary stem/progenitor marker GFRα2 in human pituitary adenomas and normal pituitary. Pituitary. 2015;18:31-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Mezzomo LC, Pesce FG, Marçal JM, Haag T, Ferreira NP, Lima JF, Leães CG, Oliveira MC, da Fonte Kohek MB. Decreased TAp63 and ΔNp63 mRNA Levels in Most Human Pituitary Adenomas Are Correlated with Notch3/Jagged1 Relative Expression. Endocr Pathol. 2017;28:13-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Orciani M, Caffarini M, Sorgentoni G, Ricciuti RA, Arnaldi G, Di Primio R. Effects of somatostatin and its analogues on progenitor mesenchymal cells isolated from human pituitary adenomas. Pituitary. 2017;20:251-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Gao Z, Cai L, Lu J, Wang C, Li Q, Chen J, Song X, Chen X, Zhang L, Zheng W, Su Z. Expression of Stem Cell Markers and Dopamine D2 Receptors in Human and Rat Prolactinomas. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:1827-1833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Horiguchi K, Fujiwara K, Yoshida S, Nakakura T, Arae K, Tsukada T, Hasegawa R, Takigami S, Ohsako S, Yashiro T, Kato T, Kato Y. Isolation and characterisation of CD9-positive pituitary adult stem/progenitor cells in rats. Sci Rep. 2018;8:5533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Tamura R, Ohara K, Morimoto Y, Kosugi K, Oishi Y, Sato M, Yoshida K, Toda M. PITX2 Expression in Non-functional Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumor with Cavernous Sinus Invasion. Endocr Pathol. 2019;30:81-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Zubeldía-Brenner L, De Winne C, Perrone S, Rodríguez-Seguí SA, Willems C, Ornstein AM, Lacau-Mengido I, Vankelecom H, Cristina C, Becu-Villalobos D. Inhibition of Notch signaling attenuates pituitary adenoma growth in Nude mice. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2019;26:13-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Soukup J, Česák T, Hornychová H, Michalová K, Michnová Ľ, Netuka D, Čáp J, Gabalec F. Stem Cell Transcription Factor Sox2 Is Expressed in a Subset of Folliculo-stellate Cells of Growth Hormone-Producing Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumours and Its Expression Shows No Association with Tumour Size or IGF1 Levels: a Clinicopathological Study of 109 Cases. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31:337-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Taniguchi-Ponciano K, Andonegui-Elguera S, Peña-Martínez E, Silva-Román G, Vela-Patiño S, Gomez-Apo E, Chavez-Macias L, Vargas-Ortega G, Espinosa-de-Los-Monteros L, Gonzalez-Virla B, Perez C, Ferreira-Hermosillo A, Espinosa-Cardenas E, Ramirez-Renteria C, Sosa E, Lopez-Felix B, Guinto G, Marrero-Rodríguez D, Mercado M. Transcriptome and methylome analysis reveals three cellular origins of pituitary tumors. Sci Rep. 2020;10:19373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Cai L, Chen J, Lu J, Li Q, Chen X, Zhang L, Wu J, Zheng W, Wang C, Su Z. Tumor stem-like cells isolated from MMQ cells resist to dopamine agonist treatment. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2021;535:111396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Chen Y, Gao H, Liu Q, Xie W, Li B, Cheng S, Guo J, Fang Q, Zhu H, Wang Z, Wang J, Li C, Zhang Y. Functional characterization of DLK1/MEG3 locus on chromosome 14q32.2 reveals the differentiation of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;13:1422-1439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Xiao Z, Liang J, Deng Q, Song C, Yang X, Liu Z, Shao Z, Zhang K, Wang X, Li Z. Pimozide augments bromocriptine lethality in prolactinoma cells and in a xenograft model via the STAT5/cyclin D1 and STAT5/BclxL signaling pathways. Int J Mol Med. 2021;47:113-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Nys C, Lee YL, Roose H, Mertens F, De Pauw E, Kobayashi H, Sciot R, Bex M, Versyck G, De Vleeschouwer S, Van Loon J, Laporte E, Vankelecom H. Exploring stem cell biology in pituitary tumors and derived organoids. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2022;29:427-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Saksis R, Rogoza O, Niedra H, Megnis K, Mandrika I, Balcere I, Steina L, Stukens J, Breiksa A, Nazarovs J, Sokolovska J, Konrade I, Peculis R, Rovite V. Transcriptome of GH-producing pituitary neuroendocrine tumours and models are significantly affected by somatostatin analogues. Cancer Cell Int. 2023;23:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Yuan L, Li P, Li J, Peng J, Zhouwen J, Ma S, Jia G, Jia W, Kang P. Identification and gene expression profiling of human gonadotrophic pituitary adenoma stem cells. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2023;11:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Li J, Song H, Chen T, Zhang S, Zhang C, Ma C, Zhang L, Wang T, Qian Y, Deng X. Lysine Methyltransferase 5A Promotes the Progression of Growth Hormone Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors through the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Neuroendocrinology. 2024;114:589-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Jotanovic J, Tebani A, Hekmati N, Sivertsson Å, Lindskog C, Uhlèn M, Gudjonsson O, Tsatsaris E, Engström BE, Wikström J, Pontén F, Casar-Borota O. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Distinct Patterns Between the Invasive and Noninvasive Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors. J Endocr Soc. 2024;8:bvae040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Lenders NF, Thompson TJ, Chui J, Low J, Inder WJ, Earls PE, McCormack AI. Pituitary tumours without distinct lineage differentiation express stem cell marker SOX2. Pituitary. 2024;27:248-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Peng J, Yuan L, Kang P, Jin S, Ma S, Zhou W, Jia G, Zhang C, Jia W. Comprehensive transcriptomic analysis identifies three distinct subtypes of pituitary adenomas: insights into tumor behavior, prognosis, and stem cell characteristics. J Transl Med. 2024;22:892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Lang Y, Guo S, Tuo Y, Tian T, Wang Y, Li Q, Chen Y, Chen W, Zhu Y, Liu D. Immature PIT1-lineage Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors/Adenomas, a Morphologically Unique Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors/Adenomas Commonly With Cytologic Atypia Features and a Predilection for Aggressive Clinical Potential. Am J Surg Pathol. 2025;49:243-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Chaudhary S, Das U, Jabbar S, Gangisetty O, Rousseau B, Hanft S, Sarkar DK. Developmental pluripotency-associated 4 increases aggressiveness of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors by enhancing cell stemness. Neuro Oncol. 2025;27:123-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Garcia-Lavandeira M, Saez C, Diaz-Rodriguez E, Perez-Romero S, Senra A, Dieguez C, Japon MA, Alvarez CV. Craniopharyngiomas express embryonic stem cell markers (SOX2, OCT4, KLF4, and SOX9) as pituitary stem cells but do not coexpress RET/GFRA3 receptors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E80-E87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, Hao Y, Shi Q, Hjelmeland AB, Dewhirst MW, Bigner DD, Rich JN. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444:756-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4467] [Cited by in RCA: 4847] [Article Influence: 242.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Nadkarni A, Shrivastav M, Mladek AC, Schwingler PM, Grogan PT, Chen J, Sarkaria JN. ATM inhibitor KU-55933 increases the TMZ responsiveness of only inherently TMZ sensitive GBM cells. J Neurooncol. 2012;110:349-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Carreno G, Gonzalez-Meljem JM, Haston S, Martinez-Barbera JP. Stem cells and their role in pituitary tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017;445:27-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Caffarini M, Orciani M, Trementino L, Di Primio R, Arnaldi G. Pituitary adenomas, stem cells, and cancer stem cells: what's new? J Endocrinol Invest. 2018;41:745-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Ulasov IV, Nandi S, Dey M, Sonabend AM, Lesniak MS. Inhibition of Sonic hedgehog and Notch pathways enhances sensitivity of CD133(+) glioma stem cells to temozolomide therapy. Mol Med. 2011;17:103-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Hide T, Komohara Y, Miyasato Y, Nakamura H, Makino K, Takeya M, Kuratsu JI, Mukasa A, Yano S. Oligodendrocyte Progenitor Cells and Macrophages/Microglia Produce Glioma Stem Cell Niches at the Tumor Border. EBioMedicine. 2018;30:94-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Liu K, Jiang L, Shi Y, Liu B, He Y, Shen Q, Jiang X, Nie Z, Pu J, Yang C, Chen Y. Hypoxia-induced GLT8D1 promotes glioma stem cell maintenance by inhibiting CD133 degradation through N-linked glycosylation. Cell Death Differ. 2022;29:1834-1849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Vamvoukaki R, Chrysoulaki M, Betsi G, Xekouki P. Pituitary Tumorigenesis-Implications for Management. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59:812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Garcia-Lavandeira M, Diaz-Rodriguez E, Bahar D, Garcia-Rendueles AR, Rodrigues JS, Dieguez C, Alvarez CV. Pituitary Cell Turnover: From Adult Stem Cell Recruitment through Differentiation to Death. Neuroendocrinology. 2015;101:175-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Yi Y, Hsieh IY, Huang X, Li J, Zhao W. Glioblastoma Stem-Like Cells: Characteristics, Microenvironment, and Therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Venugopal C, Hallett R, Vora P, Manoranjan B, Mahendram S, Qazi MA, McFarlane N, Subapanditha M, Nolte SM, Singh M, Bakhshinyan D, Garg N, Vijayakumar T, Lach B, Provias JP, Reddy K, Murty NK, Doble BW, Bhatia M, Hassell JA, Singh SK. Pyrvinium Targets CD133 in Human Glioblastoma Brain Tumor-Initiating Cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:5324-5337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Gadelha MR, Casagrande A, Strasburger CJ, Bidlingmaier M, Snyder PJ, Guitelman MA, Boguszewski CL, Buchfelder M, Shimon I, Raverot G, Tóth M, Mezősi E, Doknic M, Fan X, Clemmons D, Trainer PJ, Struthers RS, Krasner A, Biller BMK. Acromegaly Disease Control Maintained After Switching From Injected Somatostatin Receptor Ligands to Oral Paltusotine. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024;110:228-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Gadelha MR, Gordon MB, Doknic M, Mezősi E, Tóth M, Randeva H, Marmon T, Jochelson T, Luo R, Monahan M, Madan A, Ferrara-Cook C, Struthers RS, Krasner A. ACROBAT Edge: Safety and Efficacy of Switching Injected SRLs to Oral Paltusotine in Patients With Acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108:e148-e159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Fleseriu M, Biller BMK, Bertherat J, Young J, Hatipoglu B, Arnaldi G, O'Connell P, Izquierdo M, Pedroncelli AM, Pivonello R. Long-term efficacy and safety of osilodrostat in Cushing's disease: final results from a Phase II study with an optional extension phase (LINC 2). Pituitary. 2022;25:959-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Fleseriu M, Newell-Price J, Pivonello R, Shimatsu A, Auchus RJ, Scaroni C, Belaya Z, Feelders RA, Vila G, Houde G, Walia R, Izquierdo M, Roughton M, Pedroncelli AM, Biller BMK. Long-term outcomes of osilodrostat in Cushing's disease: LINC 3 study extension. Eur J Endocrinol. 2022;187:531-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Newell-Price J, Fleseriu M, Pivonello R, Feelders RA, Gadelha MR, Lacroix A, Witek P, Heaney AP, Piacentini A, Pedroncelli AM, Biller BMK. Improved Clinical Outcomes During Long-term Osilodrostat Treatment of Cushing Disease With Normalization of Late-night Salivary Cortisol and Urinary Free Cortisol. J Endocr Soc. 2024;9:bvae201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Pivonello R, Bancos I, Feelders RA, Kargi AY, Kerr JM, Gordon MB, Mariash CN, Terzolo M, Ellison N, Moraitis AG. Relacorilant, a Selective Glucocorticoid Receptor Modulator, Induces Clinical Improvements in Patients With Cushing Syndrome: Results From A Prospective, Open-Label Phase 2 Study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:662865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/