Published online Dec 6, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i34.111438

Revised: September 4, 2025

Accepted: November 21, 2025

Published online: December 6, 2025

Processing time: 159 Days and 3.7 Hours

Acyclovir (ACV)-resistant herpes simplex virus (HSV) strains have emerged and gradually increased in number. Prolonged treatment, such as for immunocompromised patients, has been observed on many occasions to lead to the develop

A 58-year-old man with a fever of 38°C had tremors. Evaluation revealed 14 po

ARHE recurred in the patient following remission; therefore, it is necessary to discuss the length of the treatment period.

Core Tip: Acyclovir (ACV)-resistant herpes simplex virus strains have emerged and gradually increased in number. We report the first case of ACV-resistant herpes encephalitis (ARHE) recurring in an immunocompromised adult patient without neurosurgical interventions. Clinicians should recognize this condition because treatment for ARHE is limited, and it often develops into severe herpes disease that is refractory to antiviral drug therapy. In addition, ARHE recurred in the patient following remission; therefore, it is necessary to discuss the length of the treatment period. There is no established standard treatment for recurrence cases; therefore, accumulation of evidence is needed.

- Citation: Usuda D, Furukawa D, Imaizumi R, Ono R, Kaneoka Y, Nakajima E, Kato M, Sugawara Y, Shimizu R, Inami T, Kawai K, Matsubara S, Tanaka R, Suzuki M, Shimozawa S, Hotchi Y, Osugi I, Katou R, Ito S, Mishima K, Kondo A, Mizuno K, Takami H, Komatsu T, Nomura T, Sugita M. Recurrence of acyclovir-resistant herpes encephalitis in an immunocompromised patient: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(34): 111438

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i34/111438.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i34.111438

Globally, herpes simplex virus (HSV) is the most common double-stranded DNA virus, representing serious dangers to human health through sporadic focal encephalitis, meningitis, genital herpes, cold sores, herpes stromal keratitis, and cancer[1-5]. Millions globally are affected by diseases caused by HSV HSV-1 and HSV-2[2,6]. Estimates put the prevalence of HSV-1 infection worldwide at ~67%, although estimates can be as low as 49% or as high as 87%[4,7]. For HSV-2, estimates suggest that it has infected 20%–25% of the general adult population, and most commonly causes only mild symptoms[2,4,8]. However, depending on immunological state, HSV-1 and HSV-2 can potentially cause severe conditions and systemic infections[8].

HSV makes up nearly 50% of all confirmed encephalitis cases, making it the most common infectious encephalitis pathogen[9]. Encephalitis is more commonly caused by HSV-1 than by HSV-2; while HSV-1 can be the cause of cases of herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) posing a risk to patients’ lives, there is also a significant amount of overlap[10,11]. HSV-1 is primarily the cause of HSE, which accounts for 5%–15% of both pediatric and adult infectious encephalitis[12]. HSE is a reactivation of a latent herpes virus, enabling the virus to directly lead to viral neurotoxicity[13]. Recurring infections are another characteristic trait[14]. The characteristic course of HSE is short and monophasic, but patients may also experience, a few weeks later, neurological relapses or deficit worsening, after terminating viral therapy and when there is apparent stabilization of the signs and symptoms of damage to the central nervous system[15].

Acyclovir (ACV) arrived on the market in 1977 as the first drug specifically to treat HSV[4,5]. Viral thymidine kinase (TK) phosphorylates it, forming ACV monophosphate, which is in turn phosphorylated by cellular kinases, taking on its active form of ACV triphosphate[4,5]. ACV-triphosphate serves as a competitive inhibitor of viral DNA polymerase[5]. It is the predominant therapeutic drug used for suppressing HSV-1 in clinical interventions, and ACV analogs serve as the reference drugs for herpetic infections[4,8]. ACV is the exclusive antiviral medication used for treating the rarely seen, yet potentially fatal, viral infection HSE[5,16,17]. Indeed, widespread adoption of ACV led to a decrease in HSE-related mortality[5]. HSV DNA polymerase is selectively inhibited by the first- and second-line antiviral drugs used for treating HSV infections (ACV and related compounds), and by foscarnet and cidofovir[14]. However, there has been an emer

A 58-year-old Japanese man was transported to our hospital by ambulance with a complaint of a fever of 39°C, fatigue, and rigors.

Twelve hours prior, he had developed a fever of 39°C, fatigue, and rigors. He took an antipyretic, but the symptoms persisted.

The patient’s medical history included pneumonia when he was 51 years old. At the time, he underwent antibiotic treatment for 10 days.

The patient had a 38-year history as a heavy smoker, averaging roughly 20 cigarettes daily, and was a social drinker. He did not undergo regular medical check-ups. He worked at a clerical job and was allergic to penicillin. He was married and had a family of four. The patient could engage in everyday activities without assistance, and had no known family history of hereditary or malignant diseases.

The patient was 180 cm tall and weighed 70 kg. At the emergency department (ED), he showed abnormal vital signs, with a blood pressure of 177/102 mmHg, heart rate of 116 regular beats/min, body temperature of 39.0°C, oxygen saturation of 95% under 1 L/min oxygen on nasal canula, respiratory rate of 30/min, and a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 14 points (E4V4M6). Nothing abnormal was detected upon physical examination, including skin or neurological findings, such as nuchal rigidity or jolt accentuation.

Upon the patient’s arrival at the ED, a routine laboratory examination was undertaken, and it found raised levels of fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products, blood sugar, glycosylated hemoglobin A1c, and serum osmolality, as well as low levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone and free triiodothyronine (Table 1). A urine qualitative test revealed negative results for urinary tract infection. Two rapid urinary antigen detection kits, BinaxNOW™ Streptococcus pneumoniae (Abbott, USA) and BinaxNOW™ Legionella pneumophila (Abbott), both tested negative. He also tested negative on a rapid antigen test to check for influenza, Quick Chaser Flu A, B (S type) (Mizuho Medy, Japan), and on an ID NOW™ coronavirus disease 2019 assay (Abbott); a near-patient isothermal nucleic acid amplification test that, according to marketing, gives a qualitative result of positive, negative, or invalid within 15 min.

| Parameter | Measured value | Normal value |

| White blood cells (103/µL) | 8.2 | 3.9-9.7 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 79 | 37-72 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 17 | 25-48 |

| Monocytes (%) | 3 | 2-12 |

| Eosinophils (%) | 0 | 1-9 |

| Basophils (%) | 1 | 0-2 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 15.9 | 13.4-17.1 |

| Platelets (103/µL) | 190 | 153-346 |

| Aspartate transaminase (IU/L) | 19 | 5-37 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 20 | 6-43 |

| Lactic acid dehydrogenase (U/L) | 192 | 124-222 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 83 | 38-113 |

| γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase (IU/L) | 31 | 0-75 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.9 | 0.4-1.2 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 7.7 | 6.5-8.5 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.7 | 3.8-5.2 |

| Creatine kinase (U/L) | 59 | 57-240 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 13 | 9-21 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.79 | 0.6-1 |

| Amylase (IU/L) | 112 | 43-124 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 136 | 135-145 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.3 | 3.5-5 |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 99 | 96-107 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 8.8 | 8.5-10.2 |

| Inorganic phosphorus (mg/dL) | 3.1 | 2-4.5 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 0.03 | 0-0.29 |

| Plasma glucose (mg/dL) | 238 | 65-109 |

| Glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (NGSP) (%) | 11 | 4.6-6.2 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (seconds) | 24.8 | 23-36 |

| Prothrombin time (International normalized ratio) | 1 | 0.85-1.15 |

| Fibrinogen and fibrin degradation products (μg/mL) | 8.9 | 0-10 |

| D-dimer (μg/mL) | 1 | 0-1 |

| Ammonia (μg/dL) | 31 | 28-70 |

| Serum osmolality (mOsm) | 295 | 275-290 |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone | 0.16 | 0.56-4.3 |

| Free triiodothyronine (pg/mL) | 1.08 | 2.4-4.5 |

| Free thyroxine (ng/dL) | 1.52 | 1-1.7 |

| Lactic acid (mmol/L) | 1.3 | 0.44-1.78 |

Head and thoracoabdominal computed tomography revealed negative results. An electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia.

We established a diagnosis of infection with unknown origin.

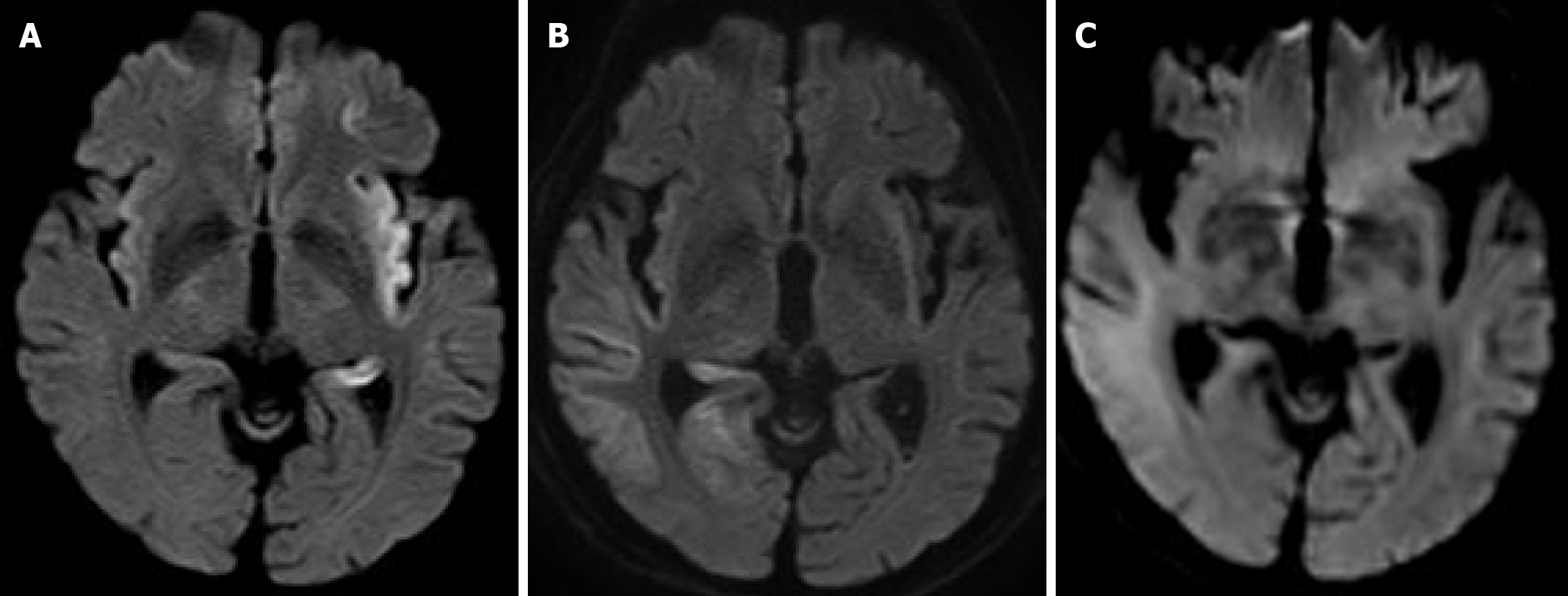

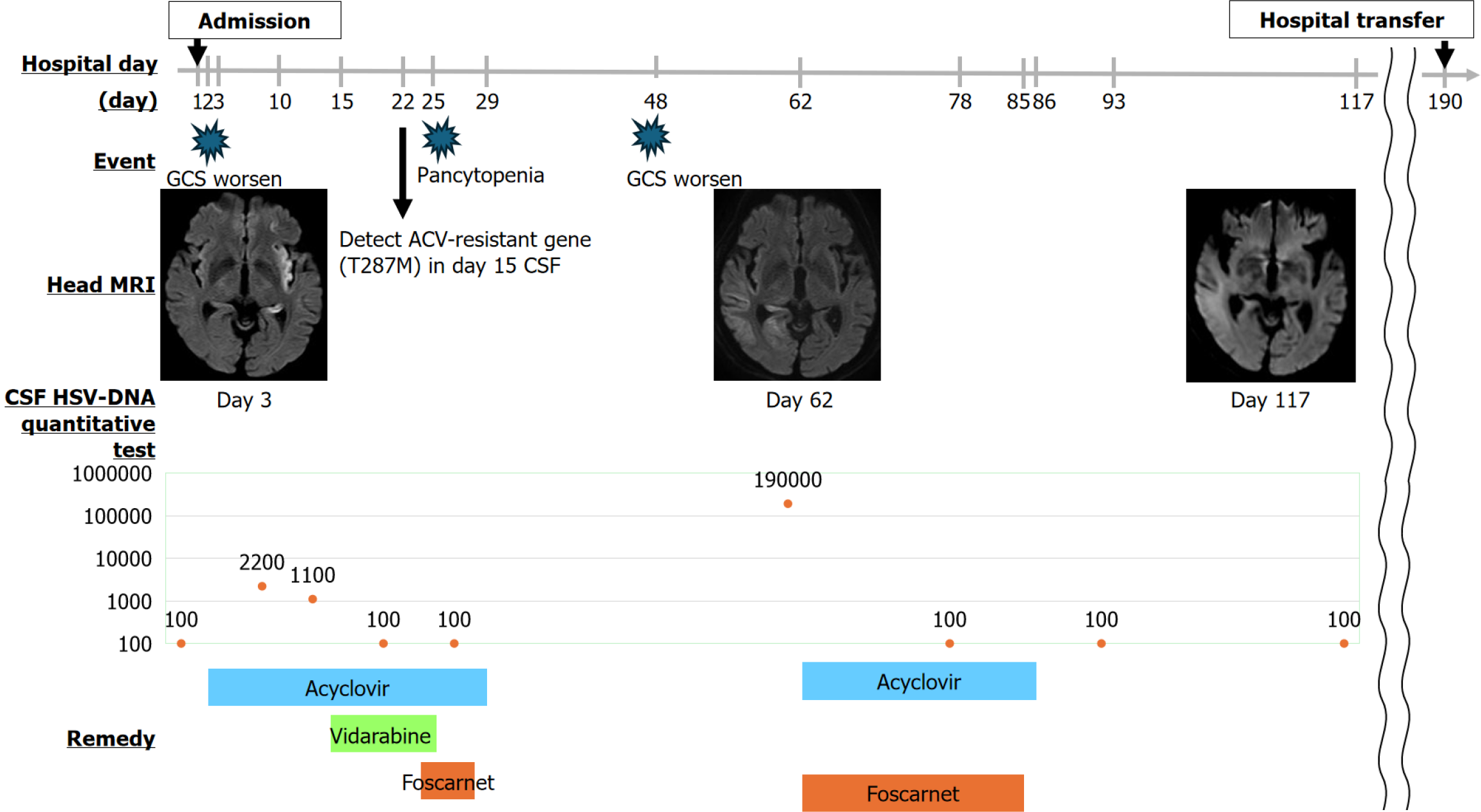

With the patient’s consent, we admitted him for treatment. The patient was treated with symptoms as they appeared. However, on hospital day 2, the fever continued, the Glasgow Coma Scale worsened to 8, and nuchal rigidity was confirmed. Continuous electroencephalography revealed spikes one or two times per second. A lumbar puncture performed to rule out cerebromeningitis showed colorless, transparent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and an initial pressure of 16 cmH2O, cell count of 2/µL (mononuclear cell advantage), protein of 48.9 mg/dL, and glucose of 146 mg/dL (plasma glucose: 231 mg/dL). Based on this result, we ruled out bacterial meningitis (Table 2). Diffusion-weighted image (DWI) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on hospital day 3 showed a high-intensity area between the left temporal lobe and insular cortex, suggesting HSE (Figure 1A). We started 2250 mg/day intravenously administered ACV on the same day, with the intention of continuing it for ≥ 7 days. Despite intravenous administration of 1000 mg/day levetiracetam, spike waves were still observed on electroencephalogram readings. We determined that the patient had status epilepticus and started invasive mechanical ventilation on the same day. In addition, continuous infusion of fentanyl was administered for analgesia, and continuous infusion of propofol was administered for sedation. Nutritional management was provided via enteral feeding, and blood glucose was controlled with continuous insulin infusion. We also administered continuous heparin infusion to prevent deep vein thrombosis, as well as an intravenous proton pump inhibitor to prevent peptic ulcers. CSF taken on hospital day 2 tested positive for HSV DNA, confirming the diagnosis (Table 2). However, un

| Parameter (Unit) | Measured value | Normal value |

| Appearance | Clear | Clear |

| pH | 7.4 | 7.4-7.6 |

| Initial pressure (cmH2O) | 16 | 50-180 |

| Cell count (/µL) | 2 | ≤ 5 |

| Mononuclear cell | 2 | ≤ 5 |

| Neutrophilic cell | 0 | 0 |

| Total protein (mg/dL) | 48.9 | ≤ 45 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 146 | 45-80 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 145 | 143-154 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 2.8 | 2.7-3 |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 120 | 120-130 |

| VZV DNA quantitative | < 1.0 × 102 | 0 |

| HSV DNA quantitative | < 1.0 × 102 | 0 |

| VZV DNA qualitative | Negative | Negative |

| HSV DNA qualitative | Positive | Negative |

Although the patient’s disease no longer recurred, prolonged bed rest and prolonged disuse of the muscles of this type can result in muscular atrophy. The patient was transferred to another hospital for continuous treatment, including ventilator weaning on hospital day 190. Afterwards, the recurrence of HSE did not occur. During the hospital stay, treatment was provided in accordance with the wishes of the patient and his family, and at the time of transfer, the family expressed their gratitude. The patient’s clinical course can be seen in Figure 2.

We report the first case of ARHE recurring in an immunocompromised adult patient without neurosurgical interventions. In this case, there are several points that are incompatible with previous reporting. First, the patient had no history of prolonged treatment with ACV or occurrence of ARHE. Second, HSE relapses occurred without any neurosurgical interventions. Consequently, there is value in reporting this event. When immunocompetent patients encounter HSV, the host’s immune system rapidly brings it under control, and the recurrent lesions that develop are both small and short-lived in nature[20]. Patients treated with antiviral agents generally tend not to develop resistance to the drugs[20]. Immunocompromised patients, in contrast, may not have the ability to bring HSV infections under control on their own[20]. Consequently, immunocompromised patients are susceptible to frequent, severe reactivations of HSV, and infections can ultimately result in fatal herpetic encephalitis or disseminated HSV infections[20].

In this case, the patient was found to be suffering from uncontrolled glycemia (glycosylated hemoglobin A1c 11%) at the ED, which may have led to his immunocompromised status. This may have led in turn to severe reactivation and finally to HSE, together with the emergence of HSV resistance to ACV. Therefore, we could propose hypotheses that an immunocompromised metabolic state independently drives emergence of ACV resistance. More specifically, ACV resistance is likely due to a combination of lost TK activity, altered TK substrate specificity, and altered DNA polymerase activity[5]. By far the most common causes of ACV resistance (95% of cases) are mutations in the viral UL23 gene encoding for the ACV-targeted TK protein, and TK mutations[5,21,22]. In this case, we detected the T287M mutation gene. As for the TK genotype of strains of HSV-1 resistant to ACV, resistance is known to be related to strain number No. 264-12, and substitutions and frameshifts from the natural genes N23, K36E, and A265T to the mutation gene T287M are related to resistance[23]. Therefore, this case is compatible with the previous article. In contrast, the mechanism or pathogenesis between immunocompromised status and the emergence of HSV resistance to ACV has yet to be fully elucidated.

In some cases, replicative recurrence has been associated with the innate immune response of neuronal cells being altered by genetic defects[12]. Additionally, there has been scant reporting of HSE recurrence: Only a handful of cases, which occurred after neurosurgical interventions[24]. HSV reactivation is seen in Japan only extremely rarely[13]. However, it is important for neurologists to learn to recognize this condition, as this disorder will become more prevalent as epilepsy surgery becomes more common[13]. In this case, HSE recurred without neurosurgical interventions, making it incompatible with previous reporting. Therefore, it could be said to constitute a new finding.

Treatment options for ACV-resistant HSV patients are comparatively constrained, due to the frequent development of severe herpes disease refractory to antiviral drug therapy in immunocompromised hosts[20]. As a direct consequence, physicians need to develop regimens to address not only receptive but also refractory HSV disease[20]. One alternative is foscarnet, which directly acts upon viral DNA polymerase[5,18]. When encountering a patient with a deteriorating clinical condition under ACV treatment, even if there is seemingly no increase in CSF HSV viral load, it can be beneficial to consider the possibility of ACV-resistant HSE, and consequently add foscarnet to the ACV treatment[5]. In one case report, an ACV-resistant HSE patient was ultimately treated successfully with a combination treatment of ACV and foscarnet[5]. In another case, a patient’s HSE was resolved after being treated with foscarnet for an unknown duration[25]. This is the only known case to date of ACV-resistant HSE occurring in an immunocompetent adult who had been, to that point, therapy-naïve[25]. In another case, an ACV-resistant HSE patient had their therapeutic regimen modified in its fifth week, to add vidarabine (15 mg/kg/day)[26]. In this case, antiviral drug treatment was discontinued after HSV DNA in the CSF eventually decreased to such a point that it became undetectable[26]. Another case report has covered a case of ACV-resistant HSE being successfully treated with adalimumab, an anti-tumor necrosis factor-α monoclonal antibody[27]. In this case being reported, we successfully treated ACV-resistant HSE with combined ACV and foscarnet. We found no articles regarding the standard treatment for cases involving recurrence. Based on this, an insufficient period of initial treatment with foscarnet may have led to recurrence. It is well established that viral replication, combined with overzealous inflammatory response, causes the cerebral damage that can result from HSE[11]. Ideally, adjunctive immunomodulatory drugs should first be administered during the increase in the inflammatory response, with a limited duration of administration to limit undesirable side effects[11]. Therefore, we should have administered the adjunctive immunomodulatory drugs to prevent the inflammatory response.

This case report has some limitations. First, it is limited to only one case report and case series of ARHE; as a result, it is possible that reporting bias has affected results, and that the actual situation surrounding, and nature of, the disease may be inconsistent with our results. Further evaluation of the impact of clinical presentation, laboratory, virology, imaging examinations, and treatment patterns, as well as outcomes, will necessitate carrying out further studies. Second is the impossibility of fully ruling out the potential involvement of any organisms not identified through culturing, as microbiological examinations lack 100% sensitivity or specificity.

Clinicians should always be aware of ARHE when treating HSE, especially in immunocompromised patients. In addition, ARHE recurred in the patient following remission; therefore, it is necessary to discuss the length of treatment periods. Managing infectious and postinfectious complications will require the development of new antiviral therapies and vaccines, as well as therapies targeting the host’s immune response and/or metabolic dysfunction.

| 1. | Bai L, Xu J, Zeng L, Zhang L, Zhou F. A review of HSV pathogenesis, vaccine development, and advanced applications. Mol Biomed. 2024;5:35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hussain MT, Stanfield BA, Bernstein DI. Small Animal Models to Study Herpes Simplex Virus Infections. Viruses. 2024;16:1037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hao C, Xu Z, Xu C, Yao R. Anti-herpes simplex virus activities and mechanisms of marine derived compounds. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1302096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu Y, You Q, Zhang F, Chen D, Huang Z, Wu Z. Harringtonine Inhibits Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Infection by Reducing Herpes Virus Entry Mediator Expression. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:722748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gayretli Aydin ZG, Tanir G, Genc Sel C, Tasci Yıldız Y, Aydin Teke T, Kaman A. Acyclovir Unresponsive Herpes Simplex Encephalitis in a child successfully treated with the addition of Foscarnet: Case report. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2019;117:e47-e51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Stanfield BA, Kousoulas KG, Fernandez A, Gershburg E. Rational Design of Live-Attenuated Vaccines against Herpes Simplex Viruses. Viruses. 2021;13:1637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Campos MA, Zolini GP, Kroon EG. Impact of Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs) and TLR Signaling Proteins in Trigeminal Ganglia Impairing Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1) Progression to Encephalitis: Insights from Mouse Models. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2024;29:102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ribelato EV, Wouk J, Celestino GG, Rodrigues BCD, Darido MLG, Barboza MGL, Botura TJ, de Oliveira MC, de Andrade FG, Lonni AASG, de Mello JCP, da Rocha SPD, Faccin-Galhardi LC. Topical formulations containing Trichilia catigua extract as therapeutic options for a genital and an acyclovir-resistant strain of herpes recurrent infection. Braz J Microbiol. 2023;54:1501-1511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhang L, Zhang L, Li F, Liu W, Tai Z, Yang J, Zhang H, Tuo J, Yu C, Xu Z. When herpes simplex virus encephalitis meets antiviral innate immunity. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1118236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kazanji N, Benvenuto A, Rizk D. Understanding Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Versus Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 Encephalitis After Neurosurgery: A Case Series and Literature Review. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2023;24:583-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Piret J, Boivin G. Immunomodulatory Strategies in Herpes Simplex Virus Encephalitis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2020;33:e00105-e00119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rozenberg F. [Herpes simplex virus and central nervous system infections: encephalitis, meningitis, myelitis]. Virologie (Montrouge). 2020;24:283-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shimada T, Tsunemi T, Iimura Y, Sugano H, Hattori N. [Reactivation of latent viruses in Neurology]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2022;62:697-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Krasnov VP, Andronova VL, Belyavsky AV, Borisevich SS, Galegov GA, Kandarakov OF, Gruzdev DA, Vozdvizhenskaya OA, Levit GL. Large Subunit of the Human Herpes Simplex Virus Terminase as a Promising Target in Design of Anti-Herpesvirus Agents. Molecules. 2023;28:7375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Esposito S, Autore G, Argentiero A, Ramundo G, Principi N. Autoimmune encephalitis after herpes simplex encephalitis: A still undefined condition. Autoimmun Rev. 2022;21:103187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Aboelezz A, Mahmoud SH. Acyclovir dosing in herpes encephalitis: A scoping review. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2024;64:102040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bautista L, Sirimanotham C, Espinoza J, Cheng D, Tay S, Drayman N. A drug repurposing screen identifies decitabine as an HSV-1 antiviral. Microbiol Spectr. 2024;12:e0175424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rozenberg F, Deback C, Agut H. Herpes simplex encephalitis : from virus to therapy. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2011;11:235-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lasanen T, Frejborg F, Lund LM, Nyman MC, Orpana J, Habib H, Alaollitervo S, Levanova AA, Poranen MM, Hukkanen V, Kalke K. Single therapeutic dose of an antiviral UL29 siRNA swarm diminishes symptoms and viral load of mice infected intranasally with HSV-1. Smart Med. 2023;2:e20230009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mitterreiter JG, Titulaer MJ, van Nierop GP, van Kampen JJ, Aron GI, Osterhaus AD, Verjans GM, Ouwendijk WJ. Prevalence of Intrathecal Acyclovir Resistant Virus in Herpes Simplex Encephalitis Patients. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0155531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zheng S, Verjans GMGM, Evers A, van den Wittenboer E, Tjhie JHT, Snoeck R, Wiertz EJHJ, Andrei G, van Kampen JJA, Lebbink RJ. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing of the thymidine kinase gene in a clinical HSV-1 isolate identifies F289S as novel acyclovir-resistant mutation. Antiviral Res. 2024;228:105950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Schmidt S, Bohn-Wippert K, Schlattmann P, Zell R, Sauerbrei A. Sequence Analysis of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Thymidine Kinase and DNA Polymerase Genes from over 300 Clinical Isolates from 1973 to 2014 Finds Novel Mutations That May Be Relevant for Development of Antiviral Resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:4938-4945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mantero V, Cossu M, Rigamonti A, Fiumani A, Basilico P, Tassi L, Salmaggi A. HSV-1 encephalitis relapse after epilepsy surgery: a case report and review of the literature. J Neurovirol. 2020;26:138-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Schulte EC, Sauerbrei A, Hoffmann D, Zimmer C, Hemmer B, Mühlau M. Acyclovir resistance in herpes simplex encephalitis. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:830-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kakiuchi S, Nonoyama S, Wakamatsu H, Kogawa K, Wang L, Kinoshita-Yamaguchi H, Takayama-Ito M, Lim CK, Inoue N, Mizuguchi M, Igarashi T, Saijo M. Neonatal herpes encephalitis caused by a virologically confirmed acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus 1 strain. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:356-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Schepers K, Hernandez A, Andrei G, Gillemot S, Fiten P, Opdenakker G, Bier JC, David P, Delforge ML, Jacobs F, Snoeck R. Acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex encephalitis in a patient treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α monoclonal antibodies. J Clin Virol. 2014;59:67-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/