Published online Dec 6, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i34.110925

Revised: August 12, 2025

Accepted: November 14, 2025

Published online: December 6, 2025

Processing time: 169 Days and 22 Hours

Posterior shoulder dislocation is a rare injury. It accounts for only 1%-4% of all shoulder dislocation cases. However, this injury is often underdiagnosed. Massive rotator cuff tears associated with posterior shoulder dislocation are exceptionally rare. Early diagnosis and surgical management are crucial for restoring shoulder function and preventing long-term disability.

A 60-year-old male with no previous shoulder injuries presented to our hospital with severe right shoulder pain and immobility after a motorcycle accident. He reported that he braced his fall with his right hand. Initial imaging examination revealed posterior shoulder dislocation with minimal glenoid bone loss. Six days after the injury, the patient exhibited pseudoparalysis and active forward flexion limited to 10°. Two weeks after the injury, magnetic resonance imaging revealed complete tears of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and subscapularis muscles as well as dislocation of the long head of the biceps tendon. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair was performed 6 weeks after injury. The tendon quality was acceptable with minimal fatty infiltration. At the 12-month surgical follow-up, the patient had recovered full strength and complete range of motion.

Early diagnosis and tailored repair of massive rotator cuff tears after dislocation are crucial for restoring shoulder function in older patients.

Core Tip: We have highlighted a case in which a 60-year-old male experienced a massive rotator cuff tear after posterior shoulder dislocation. He was successfully treated with arthroscopic repair, emphasizing the importance of early diagnosis, appropriate imaging evaluation, and timely surgical intervention. This case demonstrates that even in older adults, prompt recognition and repair can lead to excellent healing and complete functional recovery.

- Citation: Liu MY, Lin CH, Chen SH, Ding YS, Chiang CH. Acute massive rotator cuff tear and biceps tendon dislocation following posterior shoulder dislocation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(34): 110925

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i34/110925.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i34.110925

Posterior shoulder dislocation is a rare injury, accounting for only 1%-4% of shoulder dislocation cases. It often remains underdiagnosed more than 60% of cases with a missed diagnosis after initial evaluation[1,2]. The mechanisms underlying posterior shoulder dislocation include axial loading of the adducted and internally rotated arm, violent muscle con

Cuff tears in anterior dislocation are well documented, particularly in the elderly population. However, massive rotator cuff tears (RCTs) in posterior shoulder dislocation are rare across all age groups[6,7]. The incidence of RCTs in posterior shoulder dislocation is 2%-19% with massive tears being exceedingly rare[5]. The relatively low incidence of massive RCTs in posterior shoulder dislocation is due to the injury primarily stressing the subscapularis tendon rather than the supraspinatus or infraspinatus tendon and reducing the likelihood of massive cuff involvement. However, in cases involving high-energy trauma or preexisting degenerative changes, posteriorly displaced humeral heads may compress and tear the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons against the posterior glenoid rim, causing a massive RCT. The rarity of this clinical condition has hindered the development of optimal evidence-based guidelines for its diagnosis and management.

The delayed or missed diagnosis of posterior shoulder dislocation and RCT results in complications such as tendon retraction, muscle atrophy, and capsular laxity[8]. Early diagnosis and surgical management are crucial for restoring function and stability[9,10]. To date, only 8 cases of massive RCT following posterior shoulder dislocation have been reported, with considerable heterogeneity in patient characteristics [e.g., patient ages ranged from young (< 30 years)[2,5,10,11] to older adult[3,6,12] (30-55 years)]. Consequently, evidence-based guidelines are unavailable to support clinical suspicion, biomechanical interpretation, and therapeutic strategy. Herein, we present the case of a 60-year-old patient with an acute massive RCT following posterior shoulder dislocation. This article describes the clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, surgical techniques, and treatment outcomes in our case, offering valuable insights into this rare pathology.

A 60-year-old male presented with severe right shoulder pain and immobility following a motorcycle accident.

The patient reported no symptoms in the right shoulder before sustaining an injury in a motorcycle accident in which he braced his fall with his right hand. He was immediately transported to the emergency department of our hospital. The patient presented with an isolated right shoulder injury and no other systemic involvement. The posterior dislocation was promptly diagnosed in the emergency department and reduced under conscious sedation. The shoulder was immobilized in a sling, and the patient was instructed to restrict shoulder motion. No anesthesia-related complications occurred during reduction.

The patient had no history of shoulder pain, previous injuries, nor comorbidities.

The patient worked in an office setting and had no other remarkable history.

Upon arrival, the patient reported severe pain and experienced complete loss of active range of motion (ROM) in the right shoulder. The elbow and distal joints were unaffected, with intact circulation and no nerve damage. Six days after the injury, active forward flexion was limited to 10°, whereas passive ROM was preserved. This presentation was consistent with the symptoms of pseudoparalysis (active forward flexion < 45°).

Routine laboratory examination results were unremarkable with no signs of infection or inflammation.

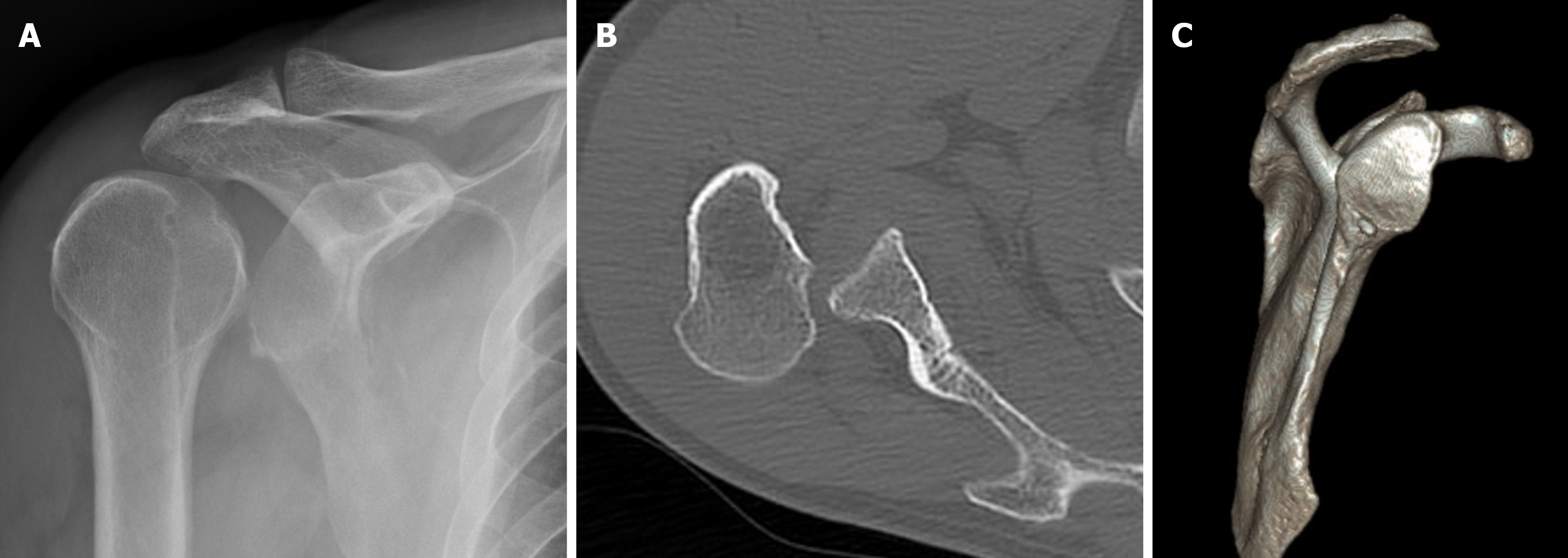

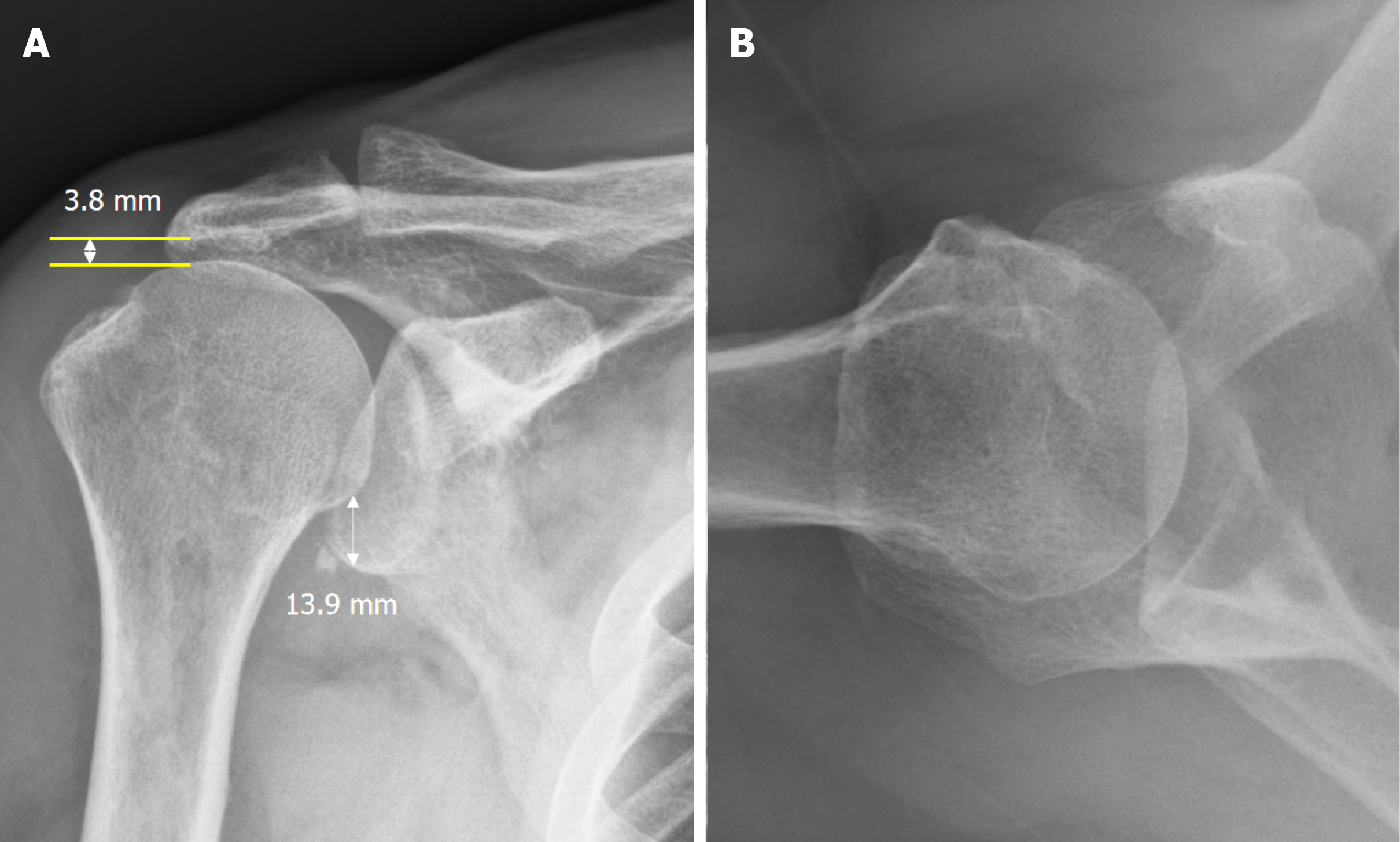

Initial radiographs and computed tomography (CT) indicated posterior shoulder dislocation with minimal glenoid bone loss (< 10%, Figure 1). Radiographs immediately after reduction confirmed successful joint alignment as well as superior humeral migration that was evidenced by a narrowed acromiohumeral interval of 3.8 mm and a wide inferior glen

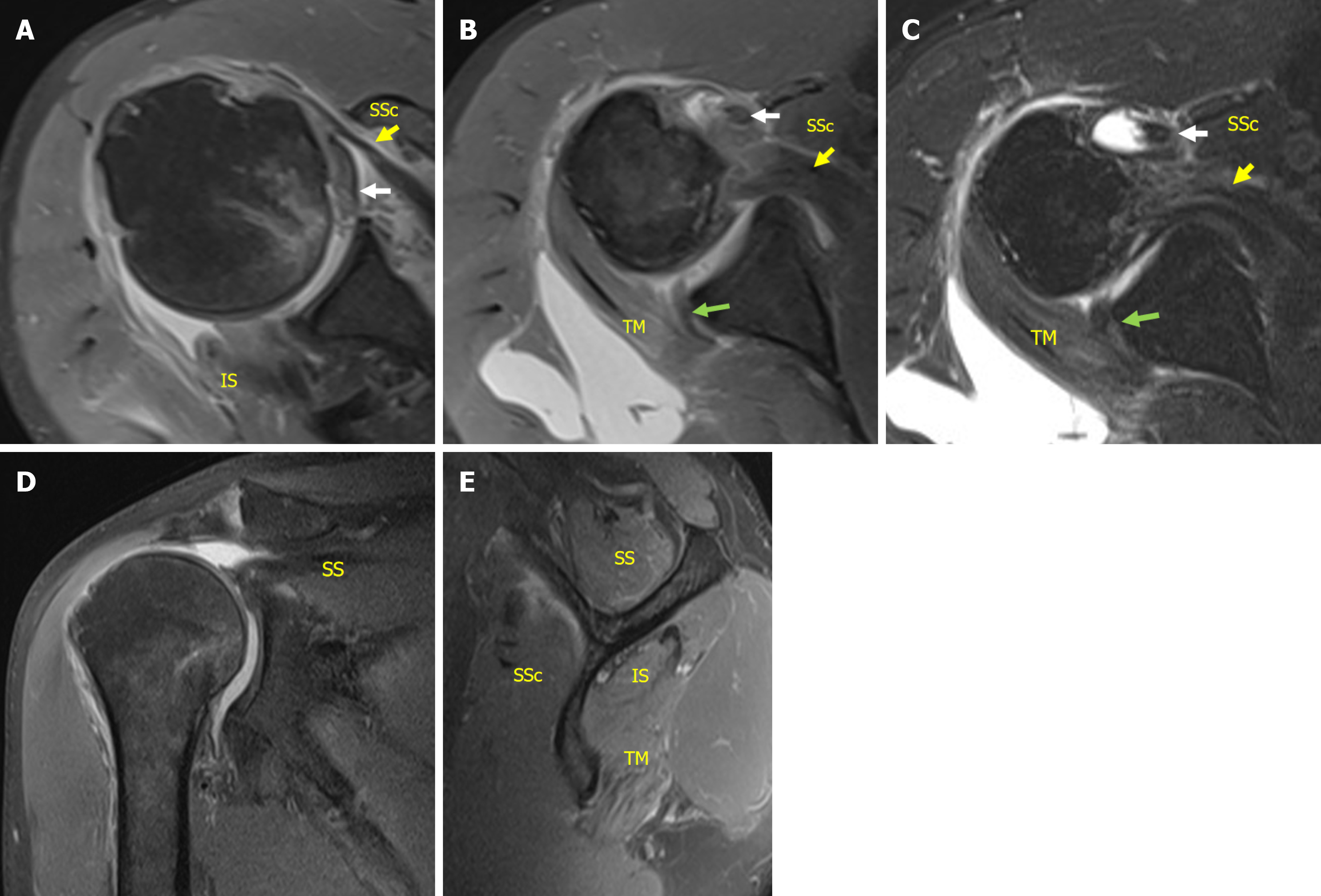

The RCT was classified as the most severe topographic type (involved segment 6 in the sagittal plane) with sup

Massive RCT involving complete tears of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons and a two-thirds tear of the subs

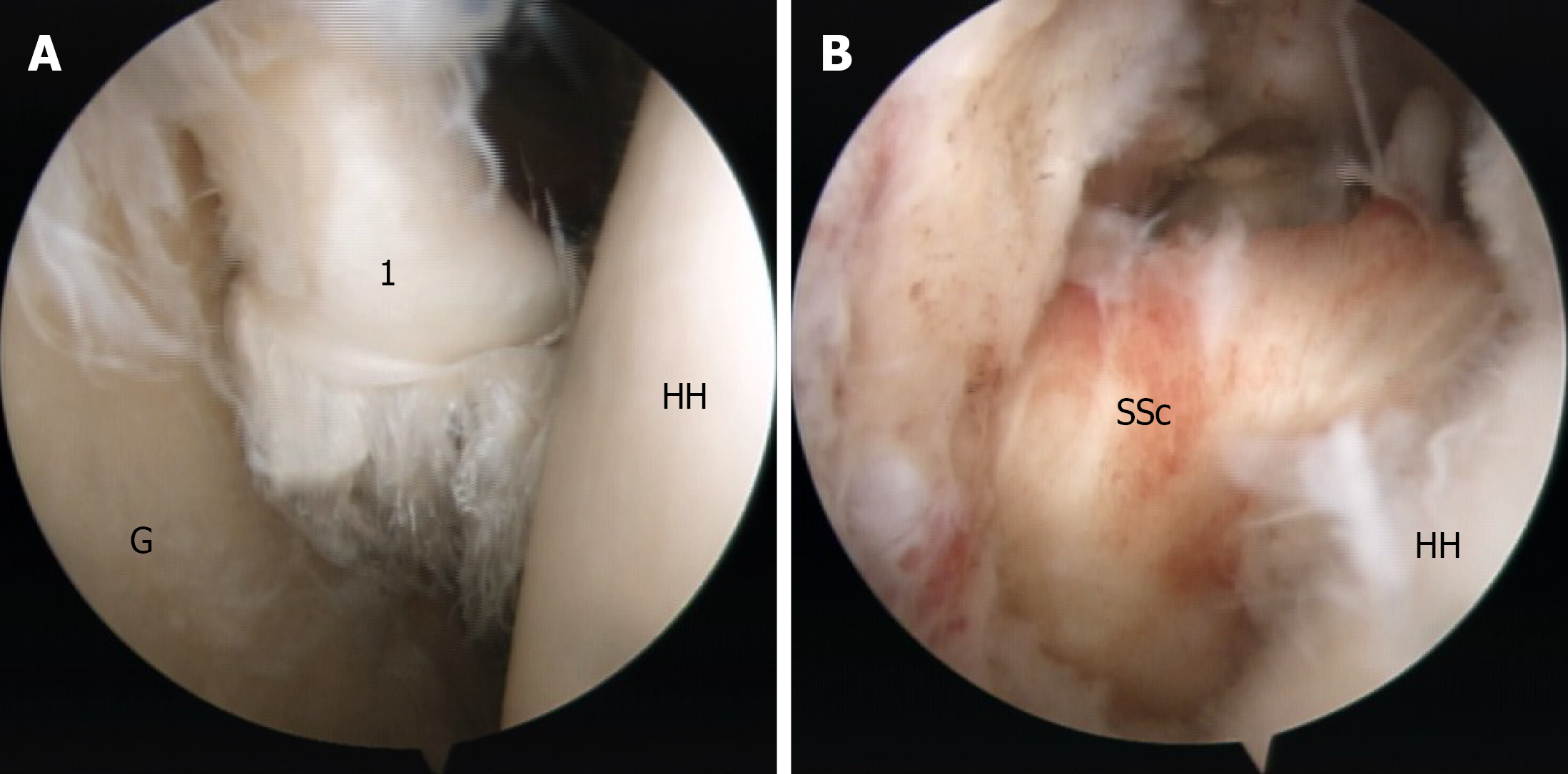

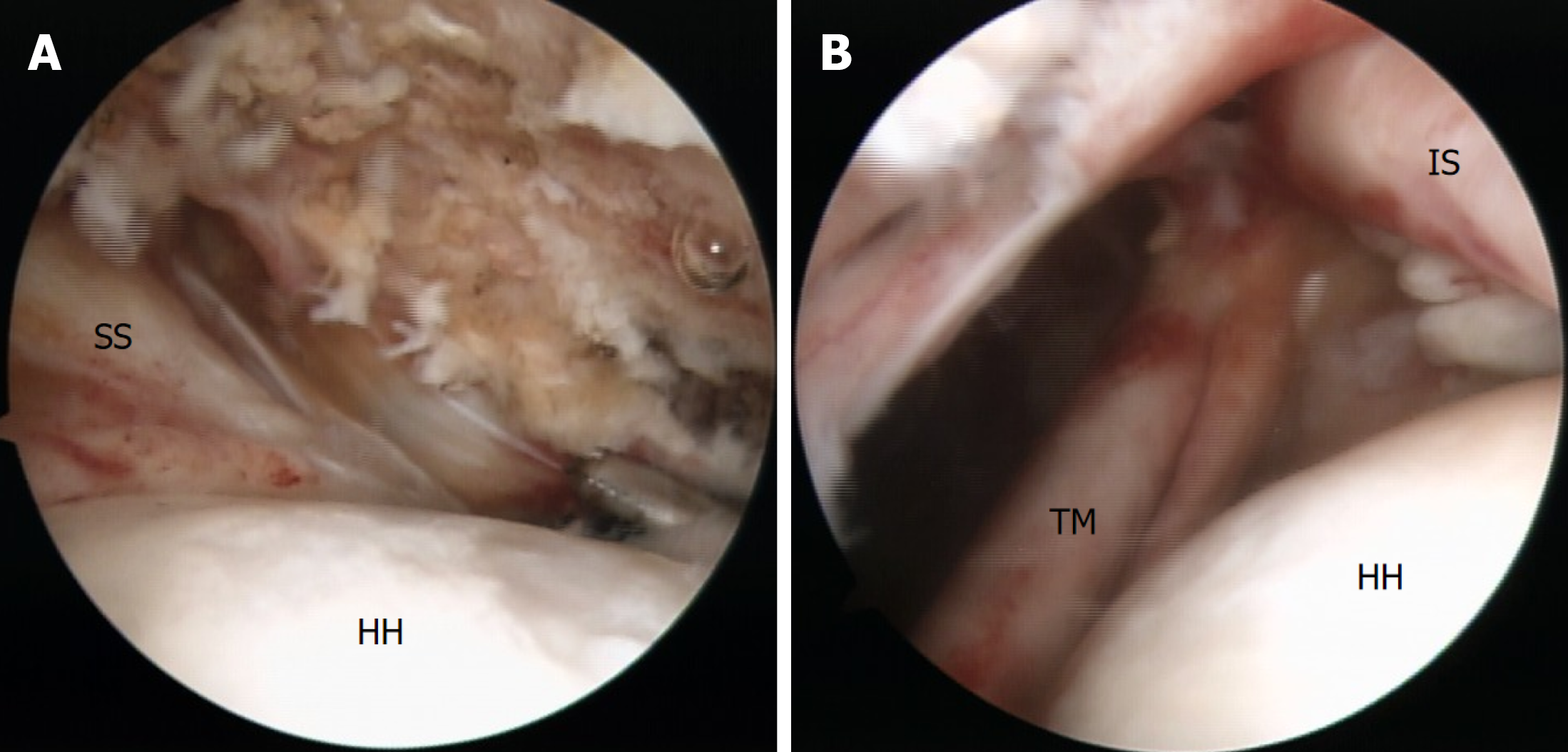

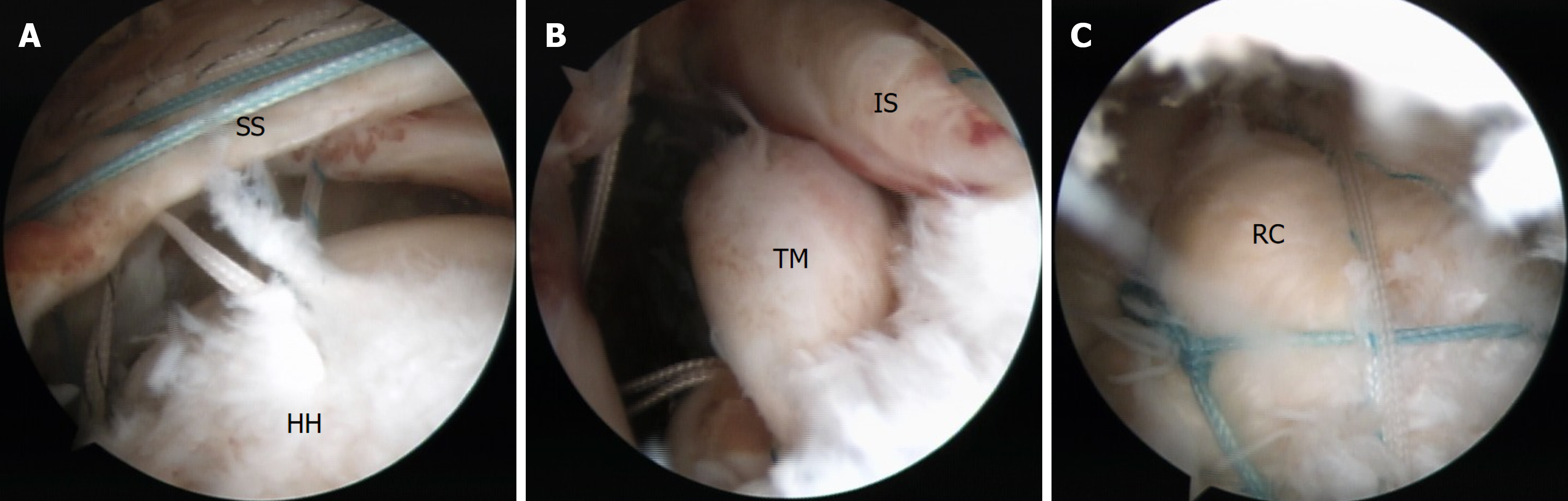

Surgery was performed 6 weeks after the injury, following confirmation of the absence of shoulder instability, fractures, avascular necrosis, and joint adhesions. After the administration of general anesthesia, the patient was positioned in the beach-chair position. Arthroscopic examination revealed an intact posterior-inferior labrum. However, a near-complete intra-articular tear and complete medial dislocation of the LHBT from the bicipital groove was observed. An upper two-thirds tear of the subscapularis (LaFosse stage 3) was also noted. Therefore, complete tenotomy of the LHBT and single-row repair of the subscapularis were performed. We utilized a double-loaded suture anchor (5.0-mm Twin-fix Ti Suture Anchor; Smith and Nephew, London, United Kingdom) with a modified Mason-Allen technique to restore anatomical continuity (Figure 4).

Acromioplasty, bursectomy, footprint preparation, debridement, and release of the torn rotator cuff were performed in the subacromial space through the lateral portal. The procedure unveiled a massive tear (Figure 5) measuring > 6 cm anteroposteriorly and 3 cm mediolaterally (determined by a laser-marked probe). The rotator cuff was repaired using a double-row suture bridge technique. Three double-loaded suture anchors were used for the medial row. All sutures were crossed and secured with two PopLoks (4.5 mm; ConMed, Largo, FL, United States) to form the lateral row (Figure 6).

Postoperatively, the shoulder was immobilized in an abduction brace for 4 weeks. Active movement of the elbow, wrist, and hand was permitted during this time. No additional physiotherapy or rehabilitation interventions were provided. After 4 weeks, passive shoulder motion was initiated under outpatient physiotherapy supervision. The primary focus was forward flexion and external rotation within a protected range to avoid stress on the repaired tendons.

Three months after the surgery, rotator cuff and scapular muscle strengthening exercises began under supervised guidance. The patient started with isometric training and gradually advanced to isotonic strengthening. Six months after the surgery, the patient was allowed to resume overhead movement or heavy work. A home-based functional training program was continued at this point. The goal of this program was to maintain shoulder ROM through gentle forward flexion and external rotation exercises, to strengthen the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers with isometric and light resistance band exercises, and to improve functional activities such as reaching and lifting. Exercises were performed independently at home without formal physiotherapy supervision.

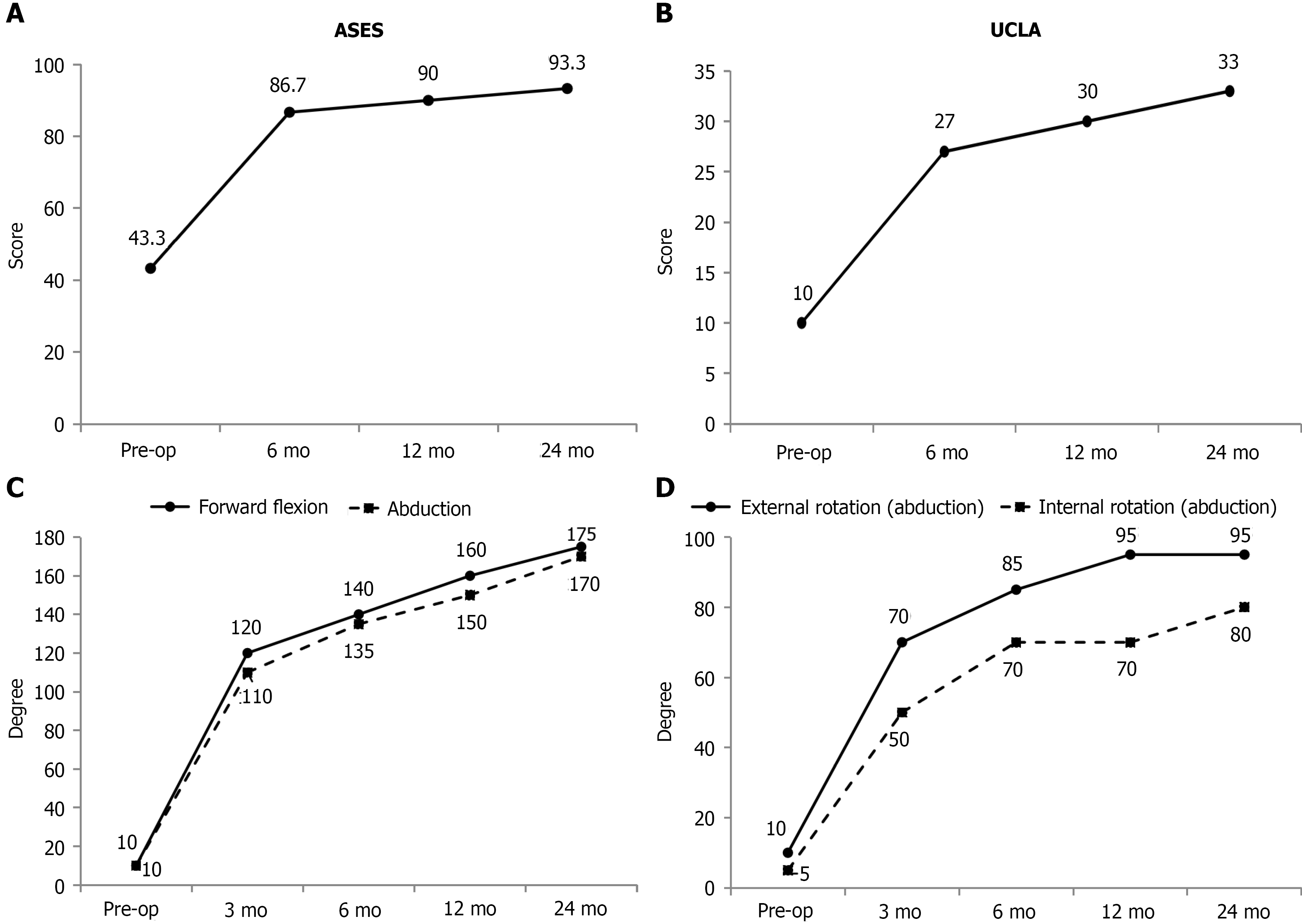

Pain, function, and ROM improved over the follow-up period (Figure 7). The American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons score, which ranges from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating better shoulder function, improved from a preoperative value of 43.3 to 93.3 at 24 months after surgery. Similarly, the University of California, Los Angeles shoulder score, which ranges from 0 to 35 with higher scores reflecting better function, increased from 10 before surgery to 33 at 24 months after surgery. The clinically important cutoff scores for the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons score and the University of California, Los Angeles shoulder score were 6.4 and 2.9, respectively[13].

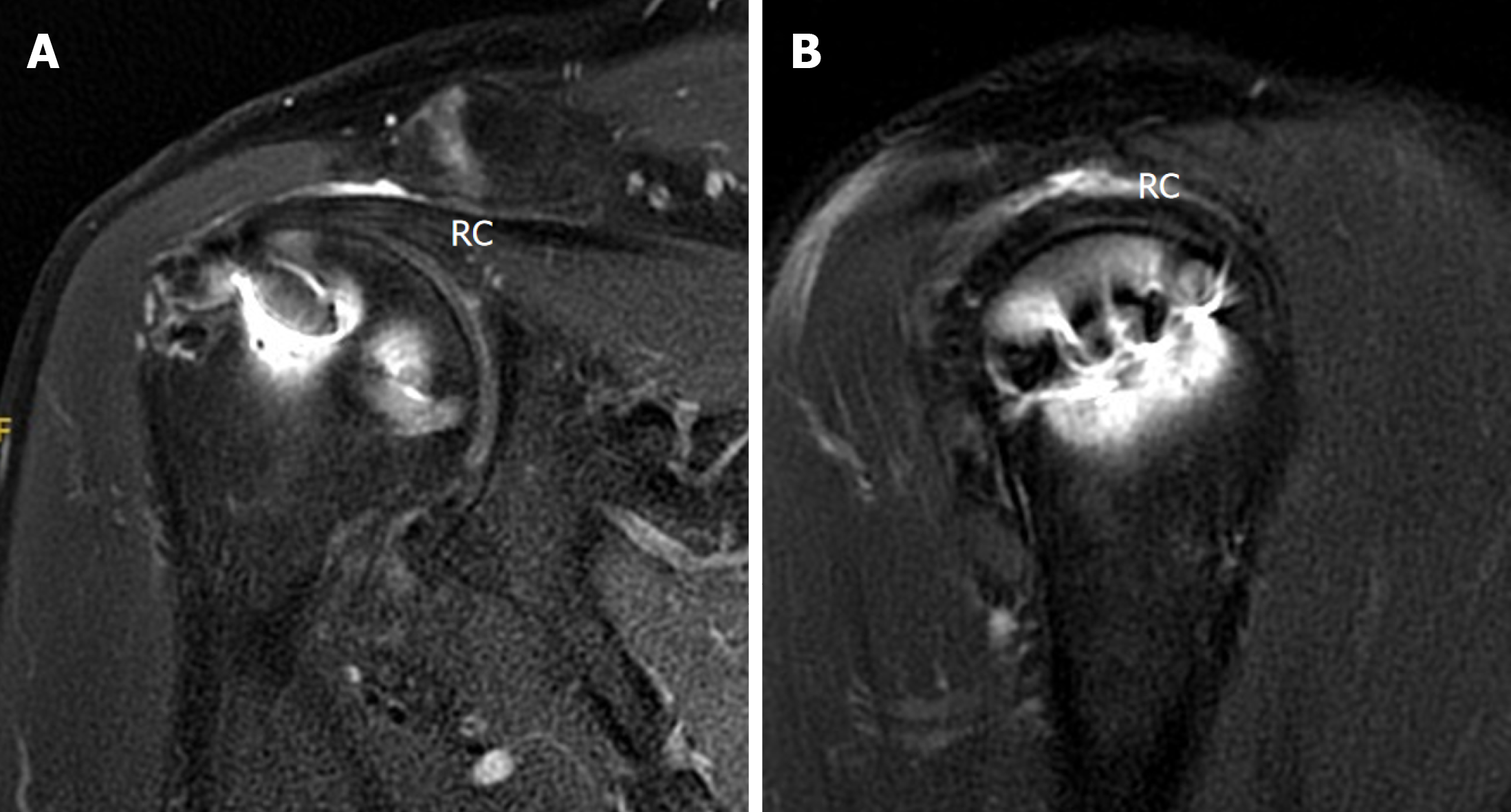

All measurements showed marked improvement in ROM at the 24-month follow-up. Forward flexion increased from 10° preoperatively to 175°, abduction from 10° to 170°, external rotation (abduction) from 10° to 95°, and internal rotation (abduction) from 10° to 80°. Follow-up MRI performed at 12 months postoperatively confirmed rotator cuff healing (Sugaya stage 1 or 2, Figure 8).

Anterior shoulder dislocation is more commonly associated with an RCT than a posterior dislocation, particularly in individuals older than 50 years. Massive RCT after posterior shoulder dislocation is exceptionally rare, with only eight well-documented cases in the literature (Table 1). Differentiating an acute rotator cuff pathology from a chronic pathology is essential for timely surgical intervention. In our case several clinical features indicated an acute tear: No previous symptoms; normal preinjury shoulder function; limited fatty infiltration indicated by MRI; and associated capsular and biceps tendon disruption. These findings align with traumatic cuff failure due to posterior loading on an adducted and internally rotated arm as described in other reports[3,6].

| Ref. | Age (years) and sex | Trauma episode and injury type | Clinical features and examination findings | Imaging findings | Treatment | Outcomes |

| Moeller[12], 1975 | 32, Male | Car accident (fell asleep at the wheel) | Open posterior dislocation with humeral head extrusion and through the skin. Supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and subscapularis muscle insertion avulsed; biceps tendon dislocation from bicipital groove | X-ray: Posterior shoulder dislocation; no fracture. Direct visualization: RCT involving supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and biceps tendon | Debridement, humeral head open reduction, rotator cuff and capsule open repair, biceps tenodesis, and skin defect management | ROM partial recovery, 70° abduction. Voluntary activity of the infraspinatus and deltoid muscles was overall reduced at 2 years |

| Steinitz et al[2], 2003 | 27, Male | Football injury | Severe pain; complete loss of passive external rotation; gross weakness in abduction and external rotation at 1 week; biceps tendon subluxation; transverse ligament tear | X-ray: Posterior dislocation, CT: No fracture, MRI: Massive global tear (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis), biceps tendon displaced but intact | Open repair with suture anchors and biceps tendon reposition and sheath repair | Full ROM; resumed contact sports in 3 months; returned to games next season |

| Schoenfeld and Lippitt[5], 2007 | 22, Male | Motorcycle accident | Shoulder pain; limited passive external rotation; weakness in supraspinatus and external rotation; developing atrophy; no neurovascular deficits | X-ray: Posterior shoulder dislocation; small reverse Hill-Sachs lesion. CT: Confirmed posterior dislocation; reverse Hill-Sachs lesion involving < 5% humeral head. MRI: Full-thickness tear of supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons; intact long head of biceps, subscapularis, and teres minor | Diagnostic arthroscopy followed by open rotator cuff repair using transosseous sutures | Full ROM and strength at 6 months; no residual pain or instability; returned to regular work at 4 months; satisfied at 1 year |

| Bhatia et al[11], 2007 | 22, Male | Contact sports injury (rugby) | Posterior shoulder dislocation with weakness and paresthesia; complete tears of supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and subscapularis tendons; disruption of anterior and posterior joint capsules; injury to inferior glenohumeral ligament; dislocation of long head of biceps tendon; associated axillary nerve and lower brachial plexus injuries | X-ray: Posterior subluxation of humeral head; “empty glenoid” sign. MRI: Full-thickness tears of supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis; biceps tendon dislocation; anterior capsule tear; inferior glenohumeral ligament injury; osteochondral lesion on humeral head; persistent posterior subluxation (approximately 75% humeral head posterior to glenoid rim) | Open surgical repair of rotator cuff tendons, joint capsule, glenohumeral ligaments, and tenodesis of the long head of the biceps tendon | Full return to professional rugby at 14 months post-surgery; near-normal strength and ROM achieved at 2 years |

| Luenam and Kosiyatrakul[3], 2013 | 36, Male | Motor vehicle collision (steering wheel) | Shoulder posterior dislocation; limited active and passive abduction and external rotation due to pain; no neurovascular deficits; shoulder unstable with posterior subluxation on exam under anesthesia | X-ray and CT: Posterior dislocation of glenohumeral joint; no osseous glenoid rim lesion, no reverse Hill-Sachs lesion, no proximal humeral fracture. MRI: Posterior subluxation of humeral head; massive RCT involving supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons; glenohumeral capsule avulsed | Open repair via posterior approach: Rotator cuff reattached by double-row technique with bone anchors; glenohumeral capsule re-approximated and sutured | At 1 year, full function with no pain or instability; status maintained at 2 years post-surgery |

| 55, Male | Motorcycle accident | Shoulder posterior dislocation; significant pain and loss of active shoulder motion; weakness in abduction, external and internal rotation; no neuro deficits; superior migration of humeral head | X-ray: Posterior dislocation confirmed; superior humeral head migration, narrowed acromio-humeral interval. MRI: Massive global RCT involving subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor; small reverse Hill-Sachs lesion | Open repair of the rotator cuff and ligaments; biceps tenodesis; combined posterior and deltopectoral approaches | Satisfactory recovery with slight shoulder stiffness; returned to full work duties; no pain or instability at 24-month follow-up | |

| Soon et al[6], 2017 | 34, Male | Bicycle fall | Failed closed reduction due to interposed long head of biceps tendon; avulsion of glenohumeral capsule | X-ray: Posterior dislocation. MRI: Massive full-thickness tear of supraspinatus and subscapularis; LHBT interposed in joint; capsular avulsion | Open reduction and cuff repair with suture anchors | Full ROM and strength at 6 months after surgery as well as full return to work |

| Quiceno et al[10], 2021 | 20, Male | Car accident | Pseudoparesis and weakness; posterior capsule detachment and LHBT dislocation | X-ray: Posterior shoulder dislocation. MRI: RCT (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis); posterior capsule detachment; medial biceps tendon dislocation | Arthroscopic repair of the rotator cuff and capsule; biceps tenodesis | Full recovery by 3 months and return to regular work at 6 months after surgery |

| Present case | 60, Male | Motorcycle accident | Severe pain and pseudoparalysis; preserved passive ROM; no neurovascular deficit | X-ray/CT: Posterior shoulder dislocation with minimal glenoid bone loss (< 10%), reduced joint space (acromiohumeral interval 3.8 mm). MRI: Complete tears of supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and subscapularis; Patte stage 3 retraction; LaFosse stage 3 subscapularis tear; medial LHBT dislocation and rupture; mild fatty infiltration (Goutallier 2/1/1/0) | Arthroscopic double-row bridge repair with LHBT tenotomy | Full ROM recovery by 12 months after surgery, excellent ASES/UCLA scores at 1- and 2-year follow-ups |

Early detection of pseudoparalysis, persistent weakness, and subtle radiographic findings, including a narrowed acromiohumeral interval and wide inferior glenohumeral distance, should prompt further advanced imaging to detect underlying rotator cuff pathology[3,6,8]. Acute traumatic tears (even in older individuals) retain superior tissue quality compared with chronic degenerative tears, allowing for anatomical repair and favorable outcomes[7,9,10]. Successful cases reported by Steinitz et al[2], Luenam and Kosiyatrakul[3], and Jaramillo Quiceno et al[10] have underscored the importance of early intervention to achieve favorable outcomes.

Notably, our patient represents the oldest documented patient at 60-year-old with complete tears of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and subscapularis tendons as well as dislocation of the LHBT following posterior shoulder dislocation who was successfully managed with arthroscopic double-row suture bridge cuff repair and biceps tenotomy. Despite the age of our patient and the extent of his injury, the relatively preserved tendon quality enabled complete anatomical repair. Therefore, age should not preclude surgical intervention, particularly when there is an acute traumatic etiology and reparable tissue quality is evident[10,12].

Awareness of the injury pattern and timely MRI are critical to avoid missed diagnoses and ensure optimal recovery. While MRI provides crucial diagnostic and preoperative information, its accuracy may be limited in acute trauma due to soft tissue edema, pain-related motion artifacts, or coexisting degenerative changes that obscure acute findings. In the elderly population this is relevant because differentiating traumatic from degenerative tears is often challenging. In our case the superior migration observed on the anteroposterior radiograph after reduction may be attributed to the acute massive RCT that disrupted the superior stabilizers of the shoulder. Axial MRI sequences showed that the posterior-inferior labrum was torn but remained attached to the scapular periosteum and partially to the glenoid and that the glenoid bone loss was minimal.

Additionally, the patient showed no clinical signs of recurrent dislocation and instability during the preoperative assessments. Therefore, no additional labral nor glenoid procedure was required. These evaluations adequately guided surgical planning, ruled out significant bony lesions, and did not alter the surgical plan despite the absence of CT images after reduction. They also served as a teaching point for recognizing subtle soft tissue injuries even when radiographs suggested potential instability. Ultimately, intraoperative assessment of the tendon mobility, tissue quality, and reparability played a decisive role in guiding the treatment strategy.

RCTs with Patte stage 3 on preoperative imaging are associated with a higher risk of irreparability[14]. Arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction is currently a reasonable alternative in cases where direct repair is unattainable. However, intraoperative findings may reveal that sufficient tendon quality will allow a tension-free anatomic repair. Dukan et al[15] reported favorable outcomes in Patte stage 3 tears treated with a knotless suture bridge technique. They found no correlation between the degree of retraction and retear risk. Therefore, direct repair is a valid option even in advanced tendon retraction. Although the supraspinatus tendon was classified as Patte stage 3 in our case, intraoperative assessment revealed sufficient tendon mobility, minimal fatty infiltration (Goutallier ≤ 2), and preserved tissue quality. These factors allowed anatomical repair using standard arthroscopic techniques without the need for augmentation. Nonetheless, it is essential to evaluate each case individually and consider alternative approaches, including arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction when tendon reparability is uncertain.

In patients with acute massive RCTs, early surgical intervention yields superior outcomes compared with delayed repair. Tendon retraction, muscle atrophy, and fatty degeneration, which can compromise reparability, progress rapidly over time[9,10]. Arthroscopic repair at 6 weeks after our patient’s injury resulted in substantial functional improvement that was characterized by recovery from pseudoparalysis to nearly full ROM and strength within 12 months.

A review of the literature revealed several common clinical features. Most patients were male, sustained high-energy trauma, and had pseudoparalysis or failed reduction attempts. Supraspinatus and infraspinatus tears were noted in all cases, and subscapularis involvement occurred more frequently in more severe injuries. Moreover, biceps tendon pathology, particularly tendon interposition, was frequently identified as a potential mechanical barrier to closed reduction[5,6,11]. We suspected a massive RCT in our patient due to persistent pseudoparalysis that was confirmed by MRI. Night pain, functional weakness, and a narrowed acromiohumeral interval should prompt advanced imaging examinations[3,8,10].

The goal of early treatment for massive RCTs is anatomical tendon repair as well as shoulder stability restoration. Unlike young athletes with recurrent posterior instability, most patients with massive RCTs due to traumatic posterior shoulder dislocation do not require bony augmentation if the rotator cuff is successfully restored. In contrast anterior dislocations frequently involve disruption of the anterior capsulolabral structures or glenoid bone loss. In these cases, static stabilizers such as the labrum, capsule, or even bone-block procedures may be necessary to restore stability[16]. Posterior dislocations are often attributed to failure of dynamic stabilizers, particularly the rotator cuff. Restoration of cuff function alone may re-establish glenohumeral stability without the need for additional capsular or osseous intervention as demonstrated in our case and in a previous report[17]. Rotator cuff repair alone successfully stabilized the joint in our patient even in the presence of an injured posterior-inferior labrum with minor glenoid bone loss. Similar outcomes have also been reported in previous studies[5,10].

While our case supports early arthroscopic repair of massive RCTs after posterior shoulder dislocation in elderly patients with good tendon quality, alternative strategies such as reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) should be considered for patients with irreparable RCTs or poor tissue quality. RSA has favorable outcomes for managing massive, irreparable RCTs by restoring shoulder function and alleviating pain. A recent systematic review comparing outcomes of primary RSA vs RSA following prior rotator cuff repair demonstrated that patients undergoing RSA after failed or prior rotator cuff repair exhibited a higher risk of complications and revision surgeries although functional results were largely comparable between groups[18]. These findings indicate the benefit of early anatomical repair when tissue quality permits, potentially reducing the need for more invasive procedures such as RSA. However, RSA is a reliable alternative in cases in which repair is not feasible. Therefore, treatment should be individualized based on patient age, reparability of the tendon, and functional demands.

This case report had several limitations. First, as a single case the findings cannot be generalized to broader populations. Second, CT imaging after reduction was not obtained, potentially limiting the ability to detect subtle bony lesions (e.g., reverse Bankart injuries, posterior glenoid rim fractures). However, axial MRI sequences and clinical assessments provided sufficient information to assess soft tissue injury and guide surgical planning. Third, postoperative mana

Acute posterior shoulder dislocation accompanied by a massive RCT remains an exceedingly rare injury, particularly in the elderly population. Our case report added to the limited body of literature on this pathology by illustrating successful arthroscopic management in a 60-year-old male with a reparable three-tendon tear and biceps tendon rupture. Despite the severity of the soft tissue injury, a prompt diagnosis and early surgical intervention facilitated full functional recovery in our patient.

The authors thank the Clinical Data Center, Ditmanson Medical Foundation Chia-Yi Christian Hospital for providing administrative and technical support. This study was based in part on data from the Ditmanson Research Database provided by Ditmanson Medical Foundation Chia-Yi Christian Hospital. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent the position of Ditmanson Medical Foundation Chia-Yi Christian Hospital.

| 1. | Rouleau DM, Hebert-Davies J. Incidence of associated injury in posterior shoulder dislocation: systematic review of the literature. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26:246-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Steinitz DK, Harvey EJ, Lenczner EM. Traumatic posterior dislocation of the shoulder associated with a massive rotator cuff tear: a case report. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:1010-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Luenam S, Kosiyatrakul A. Massive rotator cuff tear associated with acute traumatic posterior shoulder dislocation: report of two cases and literature review. Musculoskelet Surg. 2013;97:273-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rockwood CA, Matsen F, Wirth M. Glenohumeral instability. In: The Shoulder. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2004: 655-794. |

| 5. | Schoenfeld AJ, Lippitt SB. Rotator cuff tear associated with a posterior dislocation of the shoulder in a young adult: a case report and literature review. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21:150-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Soon EL, Bin Abd Razak HR, Tan AHC. A Rare Case of Massive Rotator Cuff Tear and Biceps Tendon Rupture with Posterior Shoulder Dislocation in a Young Adult - Surgical Decision-making and Outcome. J Orthop Case Rep. 2017;7:82-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Neviaser RJ, Neviaser TJ, Neviaser JS. Concurrent rupture of the rotator cuff and anterior dislocation of the shoulder in the older patient. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:1308-1311. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Hottya GA, Tirman PF, Bost FW, Montgomery WH, Wolf EM, Genant HK. Tear of the posterior shoulder stabilizers after posterior dislocation: MR imaging and MR arthrographic findings with arthroscopic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:763-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Krishnan SG, Harkins DC, Schiffern SC, Pennington SD, Burkhead WZ. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff in patients younger than 40 years. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:324-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jaramillo Quiceno GA, Arroyave Rivera SA, Ortiz MM. Acute massive rotator cuff rupture with posterior shoulder dislocation: arthroscopic novel repair of a rare injury. A case report. J ISAKOS. 2021;6:375-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bhatia DN, de Beer JF, van Rooyen KS, du Toit DF. The reverse terrible triad of the shoulder: circumferential glenohumeral musculoligamentous disruption and neurologic injury associated with posterior shoulder dislocation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:e13-e17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Moeller JC. Compound posterior dislocation of the glenohumeral joint. Case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57:1006-1007. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Chiang CH, Shaw L, Chih WH, Yeh ML, Ting HH, Lin CH, Chen CP, Su WR. Modified Superior Capsule Reconstruction Using the Long Head of the Biceps Tendon as Reinforcement to Rotator Cuff Repair Lowers Retear Rate in Large to Massive Reparable Rotator Cuff Tears. Arthroscopy. 2021;37:2420-2431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hsu KL, Kuan FC, Velasquez Garcia A, Hong CK, Chen Y, Shih CA, Su WR. Factors associated with reparability of rotator cuff tears: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2024;33:e465-e477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dukan R, Ledinot P, Donadio J, Boyer P. Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair With a Knotless Suture Bridge Technique: Functional and Radiological Outcomes After a Minimum Follow-Up of 5 Years. Arthroscopy. 2019;35:2003-2011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Longo UG, Loppini M, Rizzello G, Ciuffreda M, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Management of primary acute anterior shoulder dislocation: systematic review and quantitative synthesis of the literature. Arthroscopy. 2014;30:506-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Paul J, Buchmann S, Beitzel K, Solovyova O, Imhoff AB. Posterior shoulder dislocation: systematic review and treatment algorithm. Arthroscopy. 2011;27:1562-1572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ardebol J, Menendez ME, Narbona P, Horinek JL, Pasqualini I, Denard PJ. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for massive rotator cuff tears without glenohumeral arthritis can improve clinical outcomes despite history of prior rotator cuff repair: A systematic review. J ISAKOS. 2024;9:394-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/