Published online Nov 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i33.113312

Revised: September 12, 2025

Accepted: November 4, 2025

Published online: November 26, 2025

Processing time: 91 Days and 22.7 Hours

Submucosal tumors arise from the subepithelial layer anywhere along the gastr

A 23-year-old male patient presented with a gastric subepithelial tumor. The medical history included CD. Diagnostic workup revealed a 3-cm mucosal lesion with a central ulceration on the posterior wall of the distal antrum. The patient underwent laparoscopic wedge resection of stomach, and the postoperative cour

Despite its rarity, upper gastrointestinal CD can present as a gastric subepithelial tumor, warranting consideration in young patients with CD.

Core Tip: Given the increasing incidence of Crohn’s disease (CD) and its decreasing age of onset, upper gastrointestinal involvement is expected to become more frequent. Although gastric CD typically presents as gastritis, erosions, atypical ulcers, a cobblestone appearance of the mucosa, or strictures, it can (albeit rarely) manifest as a subepithelial tumor, as demonstrated in this case. Therefore, when a gastric subepithelial lesion is detected-particularly in young patients with CD-endoscopic ultrasonography and histological assessment are essential to distinguish upper gastrointestinal involvement of CD from other etiologies.

- Citation: Park YE. Gastric Crohn’s disease presenting as a subepithelial tumor: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(33): 113312

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i33/113312.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i33.113312

A subepithelial tumor (SET) is defined as a lesion arising beneath the epithelial layer of the gastrointestinal tract and can occur anywhere from the esophagus to the anus[1]. Among these, gastric SETs are the most common, with a reported prevalence of approximately 0.4%-1.9% in patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal (UGI) endoscopy[2]. Various lesions may appear as gastric SETs, ranging from benign tumors such as lipomas, leiomyomas, ectopic pancreas, and neurogenic tumors to malignant lesions including gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), lymphomas, gastric adenocarcinomas, and metastatic cancers[3].

Crohn’s disease (CD) is an inflammatory bowel disease that can involve any region of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus, similar to SETs; however, CD primarily affects the terminal ileum and colon[4]. Involvement of the UGI tract in CD is uncommon, and even when the stomach is affected, typical manifestations include gastritis, erosions, atypical ulcers, a cobblestone appearance of the mucosa, or strictures. Thus, gastric CD is generally not considered in the differential diagnosis of gastric SETs[4].

Herein, we present a rare instance of gastric CD manifesting as an SET, incidentally detected during endoscopic surveillance in a patient with established CD. The lesion was resected via laparoscopic wedge resection, and histopathological examination revealed non-caseating granulomas, confirming the diagnosis of gastric CD presenting as an SET.

A 23-year-old male patient was referred from the Department of Gastroenterology to the Department of Surgery for surgical resection of a gastric SET, primarily to rule out a GIST. The patient was asymptomatic.

The patient reported no UGI symptoms, including epigastric discomfort, pain, nausea, vomiting, dysphagia, weight loss, or anorexia. During surveillance colonoscopy for CD, concurrent screening esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) incidentally identified a 3-cm SET in the distal antrum. Notably, this lesion had not been observed on EGD or computed tomography (CT) conducted 2 years earlier at another hospital; this suggested that the SET had newly developed and enlarged to over 3 cm during that interval. Owing to its rapid growth and size, surgical resection was planned under strong clinical suspicion of GIST.

The patient had a history of CD, was diagnosed at 21 years of age, and was being treated with azathioprine (125 mg once daily), rifaximin (300 mg thrice daily), mesalazine (1000 mg twice daily), and rabeprazole (10 mg once daily). Five years prior, he had undergone fistulectomy for anal fissures and abscesses.

There was no family history of inflammatory bowel disease, including CD or ulcerative colitis, or any family history of gastric cancer or other gastrointestinal malignancies.

At the time of admission, his vital signs and physical examination were unremarkable.

Laboratory findings were unremarkable.

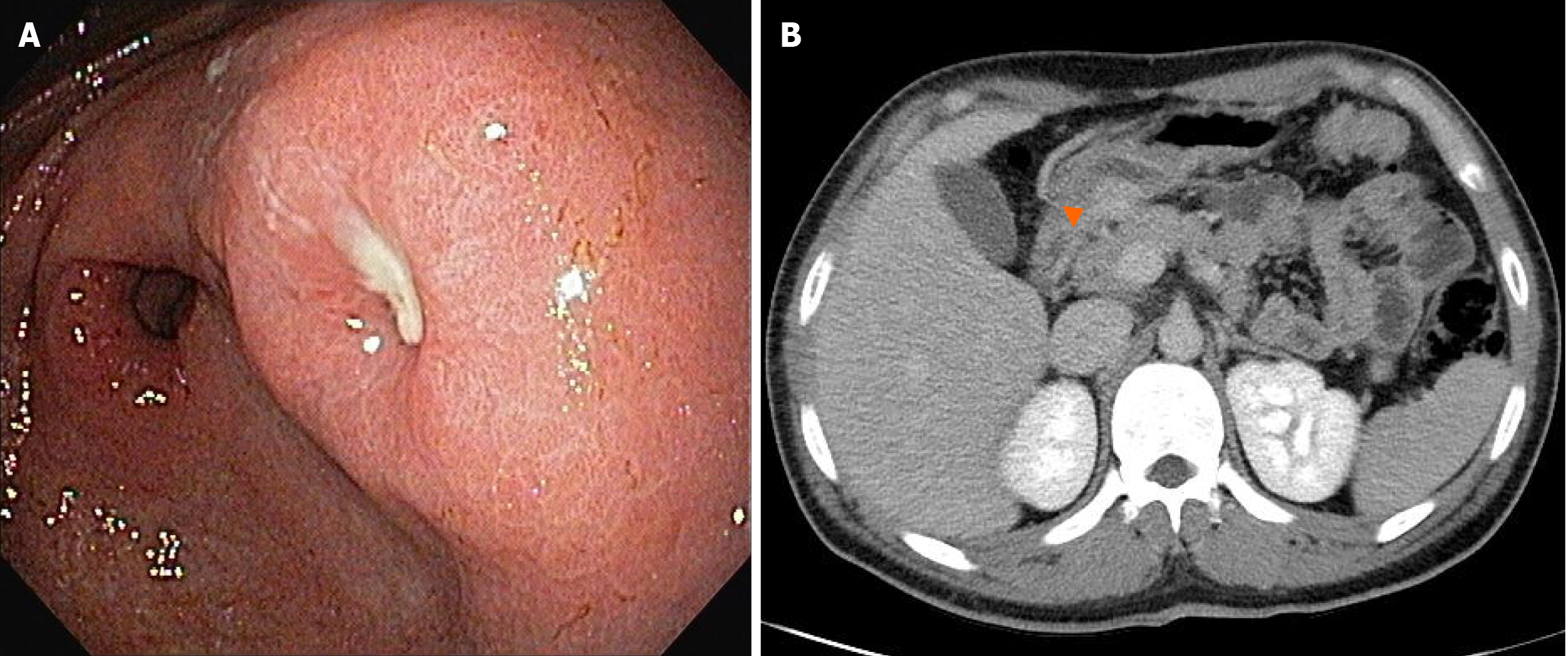

EGD revealed a 3-cm mucosal bulge with central ulceration on the posterior wall of the distal antrum (Figure 1A). Abdominal CT showed a hypervascular submucosal mass in the same location (Figure 1B).

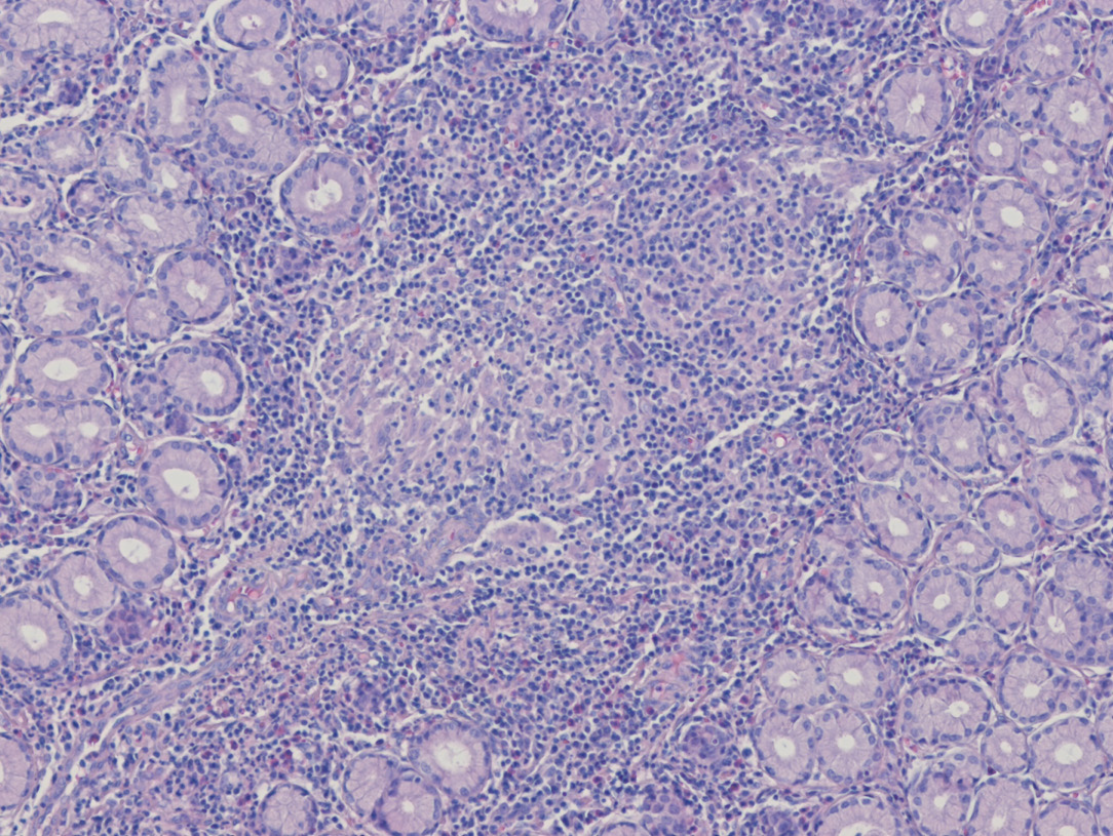

Immunohistochemical staining of the resected specimen showed negativity for CD117, DOG1, and CD34, effectively excluding GIST and arguing against an inflammatory fibroid polyp. The lack of CD1a expression, together with CD68positive histiocytes and only focal S100 reactivity, favored an inflammatory granulomatous process rather than Langerhans cell histiocytosis, gastrointestinal schwannoma, or granular cell tumor. Histopathological examination revealed chronic active gastritis with ulceration and non-caseating granulomas (hematoxylin–eosin stain, Figure 2). Together with the clinical context of CD, these findings indicated UGI involvement of CD presenting as a gastric SET (Table 1).

| Entity | Prototypical IHC profile | Findings in the presented case | Interpretation |

| GIST | KIT (CD117)+, DOG1+, often CD34+ | KIT (CD117)-, DOG1-, CD34- | Effectively rules out GIST |

| Gastrointestinal schwannoma | Diffuse S100+ (± SOX10+); CD34 usually negative | Focal S100 positivity; SOX10 staining not performed | Not supportive of schwannoma |

| IFP | CD34+; KIT (CD117)/DOG1-; may harbor PDGFRA mutation | CD34- | Argues against IFP |

| GCT | Diffuse S100+; SOX10+; CD68+ in tumor cells | Focal S100 positivity; CD68 highlights non-neoplastic histiocytes | Pattern not compatible with GCT |

| Leiomyoma | SMA+, desmin+, hcaldesmon+; KIT (CD117)/DOG1- | No features of a smooth muscle tumor; SMA/desmin staining not performed | Unlikely |

| LCH | CD1a+, Langerin (CD207)+, S100+ | CD1a-; Langerin (CD207) staining not performed; focal S100 positivity | Rules out LCH |

| Upper gastrointestinal Crohn’s disease | Noncaseating granulomas; CD68+ histiocytes; typically CD1a- | Chronic active gastritis with ulceration and noncaseating granulomas; CD68+ histiocytes; CD1a- | Favored diagnosis |

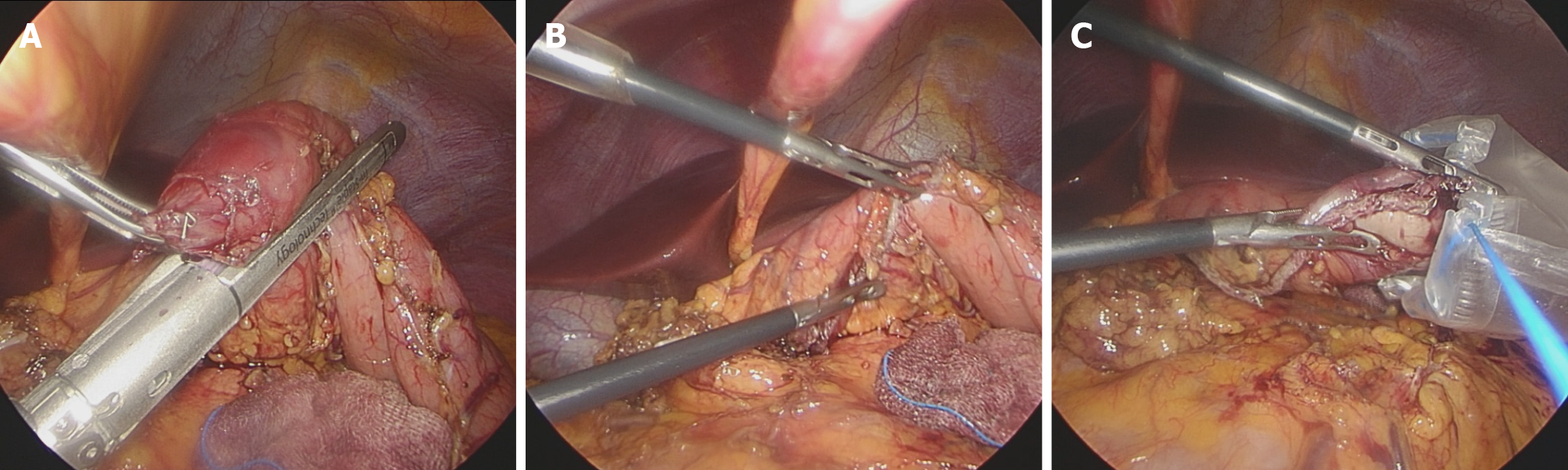

Laparoscopic wedge resection of stomach was commenced for diagnosis and treatment of gastric SET. Under general anesthesia, the patient was placed in the supine position. Three trocars (umbilical, right upper, and right middle) were inserted. The patient was then repositioned in the reverse Trendelenburg position, and laparoscopic exploration of the abdominal cavity was performed. The lesion was identified on the posterior wall of the distal antrum, with margins extending toward the greater curvature. Therefore, in preparation for wedge resection, the vessels surrounding the lesion were dissected and ligated using Hem-o-lok clips (Teleflex Medical, United States) and the LigaSure vessel-sealing system (Medtronic, United States). To avoid injury to the pyloric sphincter and prevent lesion rupture, minimal margins were obtained. Subsequently, a wedge resection was performed using the Signia stapler (Medtronic, United States) (Figure 3). The patient was allowed to drink water on postoperative day 1, and a soft diet was initiated on postoperative day 2.

The patient was discharged on postoperative day 4 without complications. One week after discharge, the histopathology results were reviewed in the outpatient clinic, and it was explained to the patient that the gastric SET represented a form of UGI involvement of CD. The patient has since been followed by the Department of Gastroenterology for ongoing medical management and surveillance of CD. At the time of writing this report, the patient had remained diseasefree for 36 months postoperatively, with surveillance EGD showing no evidence of recurrent UGI involvement of CD or any gastric SETlike lesion.

UGI involvement in CD is relatively rare, reported in approximately 0.5%-4% of all patients with CD[5]. However, the incidence is considerably higher in pediatric and adolescent populations, with rates as high as 30%-50%[6]. The diagnosis of UGI involvement in CD generally follows the same criteria as those for CD elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract, and it relies on a combination of clinical symptoms, endoscopic findings, and histopathological features, as outlined in Table 2[7]. However, when diagnosing UGI involvement, greater emphasis is placed on specific endoscopic characteristics and careful differential diagnosis, and histological identification of non-caseating granulomas plays a more decisive role than it does in typical presentations of CD[8]. In the present case, although the patient underwent surgical resection of a presumed SET, the final diagnosis of UGI involvement in CD was confirmed based on the presence of non-caseating granulomas on pathological examination (Figure 2).

| Category | Key features/findings |

| Clinical symptoms | Epigastric discomfort, epigastric pain, vomiting, dysphagia, weight loss, anorexia |

| Endoscopic findings | Aphthous ulcers, linear ulcers, cobblestone appearance of the mucosa, erosions, esophageal stricture, gastric outlet obstruction, duodenal stricture |

| Histopathological features | Noncaseating granulomas, chronic active inflammation, lymphoid follicular hyperplasia |

| Differential diagnoses | Esophagus-reflux esophagitis, eosinophilic esophagitis, viral esophagitis, tuberculous esophagitis, Stomach-Helicobacter pylori gastritis, NSAID-induced gastritis, tuberculous gastritis, Ménétrier’s disease, gastric lymphoma, Duodenum-peptic ulcer disease, celiac disease, tuberculous duodenitis, Brunner’s gland hyperplasia, duodenal lymphoma |

As noted earlier, UGI involvement in CD occurs more frequently in younger patients than in older individuals. Given the rising incidence of CD and the observed trend toward earlier onset, the prevalence of UGI involvement is also expected to increase[6,9]. Nevertheless, major societies such as the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization and the American Gastroenterological Association are yet to establish formal guidelines for routine UGI endoscopic surveillance in patients with CD[10,11]. In this case, follow-up UGI endoscopy was performed 2 years after the diagnosis of CD because the patient exhibited no UGI symptoms. However, if annual surveillance endoscopy had been conducted irrespective of symptom presence, UGI involvement might have been identified at an earlier stage, possibly presenting as a different type of lesion before progressing to an SET > 3 cm.

Given the anticipated increase in UGI involvement in CD, there is a clear need to develop specific and standardized guidelines for UGI endoscopic surveillance, particularly for younger patients. Such guidelines are essential for preventing complications and ensuring early detection of UGI manifestations in this vulnerable population.

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is highly useful for evaluating SETs as it allows assessment of the layer of origin, lesion margins, homogeneity, echogenicity, surrounding invasion, lymphadenopathy, and vascularity using Doppler[3]. These features are instrumental in distinguishing between benign and malignant SETs and estimating the histological nature of the lesion[3]. In patients with CD, EUS can reveal characteristic findings such as bowel wall thickening, loss of normal layer structure, hypoechoic or hyperechoic lesions, regional lymphadenopathy, fistulas, and abscesses[12]. Such findings are valuable not only for monitoring therapeutic response and evaluating complications but also for differentiating CD from ulcerative colitis or other mass-forming lesions, such as SETs[12]. Therefore, when SET-like lesions are detected on UGI endoscopy in patients with CD, EUS should be proactively performed to clarify the differential dia

In summary, this case illustrates a rare presentation of UGI CD as a rapidly enlarging gastric SET requiring surgical resection in a young patient with established CD. The absence of symptoms and lack of preoperative EUS contributed to delayed recognition, leading to surgery under the suspicion of GIST. This highlights the limitations of symptom-based surveillance and underscores the need for heightened clinical awareness of atypical manifestations of CD. Routine upper endoscopic surveillance and early application of adjunctive tools such as endoscopic ultrasonography should be considered in the long-term management of young patients with CD. Incorporating structured protocols for UGI monitoring into future clinical guidelines may facilitate earlier diagnosis, reduce misdiagnosis, and prevent unnecessary surgical interventions.

This case highlights a rare presentation of UGI CD as a gastric SET, in a young patient without UGI symptoms, underscoring the need to include UGI involvement in the differential diagnosis of gastric SETs in patients with est

The author thanks Dr. Hyun Dong Chae at the Catholic University of Daegu for advice.

| 1. | Kim SY, Kim KO. Management of gastric subepithelial tumors: The role of endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;8:418-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hu J, Sun X, Ge N, Wang S, Guo J, Liu X, Wang G, Sun S. The necessarity of treatment for small gastric subepithelial tumors (1-2 cm) originating from muscularis propria: an analysis of 972 tumors. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vasilakis T, Ziogas D, Tziatzios G, Gkolfakis P, Koukoulioti E, Kapizioni C, Triantafyllou K, Facciorusso A, Papanikolaou IS. EUS-Guided Diagnosis of Gastric Subepithelial Lesions, What Is New? Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:2176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kim ES, Kim MJ. Upper gastrointestinal tract involvement of Crohn disease: clinical implications in children and adolescents. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2022;65:21-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pimentel AM, Rocha R, Santana GO. Crohn's disease of esophagus, stomach and duodenum. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2019;10:35-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Putniković D, Jevtić J, Ristić N, Milovanovich ID, Đuknić M, Radusinović M, Popovac N, Đorđić I, Leković Z, Janković R. Pediatric Crohn's Disease in the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract: Clinical, Laboratory, Endoscopic, and Histopathological Analysis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024;14:877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Graca-Pakulska K, Błogowski W, Zawada I, Deskur A, Dąbkowski K, Urasińska E, Starzyńska T. Endoscopic findings in the upper gastrointestinal tract in patients with Crohn's disease are common, highly specific, and associated with chronic gastritis. Sci Rep. 2023;13:703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kővári B, Pai RK. Upper Gastrointestinal Tract Involvement in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Histologic Clues and Pitfalls. Adv Anat Pathol. 2022;29:2-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chin YH, Ng CH, Lin SY, Jain SR, Kong G, Koh JWH, Tan DJH, Ong DEH, Muthiah MD, Chong CS, Foo FJ, Leong R, Chan WPW. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The prevalence, risk factors and outcomes of upper gastrointestinal tract Crohn's disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53:1548-1558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Isaacs KL, Regueiro MD, Gerson LB, Sands BE. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Crohn's Disease in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:481-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 612] [Cited by in RCA: 1032] [Article Influence: 129.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Maaser C, Sturm A, Vavricka SR, Kucharzik T, Fiorino G, Annese V, Calabrese E, Baumgart DC, Bettenworth D, Borralho Nunes P, Burisch J, Castiglione F, Eliakim R, Ellul P, González-Lama Y, Gordon H, Halligan S, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Kotze PG, Krustinš E, Laghi A, Limdi JK, Rieder F, Rimola J, Taylor SA, Tolan D, van Rheenen P, Verstockt B, Stoker J; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO] and the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology [ESGAR]. ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 1: Initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:144-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1242] [Cited by in RCA: 1325] [Article Influence: 189.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Statie RC, Florescu DN, Gheonea DI, Ungureanu BS, Iordache S, Rogoveanu I, Ciurea T. The Use of Endoscopic Ultrasonography in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Review of the Literature. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/