INTRODUCTION

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are monoclonal antibodies that induce or amplify anti-tumor T-cell responses by blocking inhibitory immune-regulatory pathways such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), and their ligands (PD-L1). By antagonizing ligand-receptor pairs that physiologically restrain T-cell activation, ICIs convert immunologically “cold” tumors into “hot” ones, thereby enabling durable immune-mediated tumor control. The advent of ICIs that target PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 has irrevocably altered the therapeutic landscape for microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or deficient mismatch repair colorectal cancers (CRC). Groundbreaking trials have established pembrolizumab and nivolumab (both of which are anti-PD-1 antibodies) and ipilimumab (an anti-CTLA-4 antibody) - either alone or in combination - as superior to traditional chemotherapy for metastatic CRC, with significantly improved progression-free and overall survival and more favorable toxicity profiles[1-3]. This success has propelled ICIs into earlier disease settings (including as a neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced tumors) where they have demonstrated remarkable pathological complete response (pCR) rates exceeding 60% in some studies[4-6]. A pCR is defined as the absence of any viable tumor cells in surgical specimens following treatment (ypT0N0). The allure of non-operative management or organ-sparing surgery following a deep clinical response is understandably strong[7,8]. However, an extraordinary case reported by Lee et al[9] (which details a spontaneous colonic transection during surgery after pCR to pembrolizumab) sounds a crucial alarm. This unprecedented complication forces us to confront the sobering reality that the immune system’s ability to eradicate cancer can simultaneously inflict profound, potentially catastrophic damage on normal tissue architecture. Such effects may remain hidden until surgical intervention or a catastrophic clinical crisis ensues.

THE CASE: A PARADIGM-SHIFTING COMPLICATION

Lee et al[9] presented a meticulously documented case of a 44-year-old male with bulky, locally advanced MSI-H transverse colon cancer and synchronous liver metastases. Following a diverting ileostomy, he received 36 cycles of pembrolizumab over approximately two years, showing a sustained clinical and radiological complete response. A subsequent laparoscopic right hemicolectomy (intended as a curative resection) revealed a startling finding, namely, a complete spontaneous transection of the colon at the original tumor site. Histopathology confirmed a pCR with extensive transmural fibrosis, calcification, microvascular damage, and chronic inflammation, but no residual tumor. This structural discontinuity occurred despite a lack of evidence of any impending perforation or obstruction on recent radiological scans. This represents the first documented case of complete bowel wall discontinuity following an ICI-induced pCR beyond any previously reported obstructions or fibrotic strictures[10].

BEYOND TUMOR KILLING: THE DOUBLE-EDGED SWORD OF IMMUNE-MEDIATED TISSUE REMODELING

The pathological findings in this case point toward intense and sustained immune activity within the bowel wall. ICIs work by activating latent anti-tumor T-cell responses. However, this activation is not tumor-specific. T-cell activation and its associated inflammatory cascade (which involves cytokines such as interferon-gamma, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin-17) can indiscriminately target stromal and endothelial cells within the tumor microenvironment and adjacent normal tissue[11,12]. While acute immune-related adverse events (irAEs) such as colitis are highly recognizable and often manageable via immunosuppression, the case reported by Lee et al[9] reveals a more insidious, long-term consequence: Chronic, immune-driven tissue remodeling.

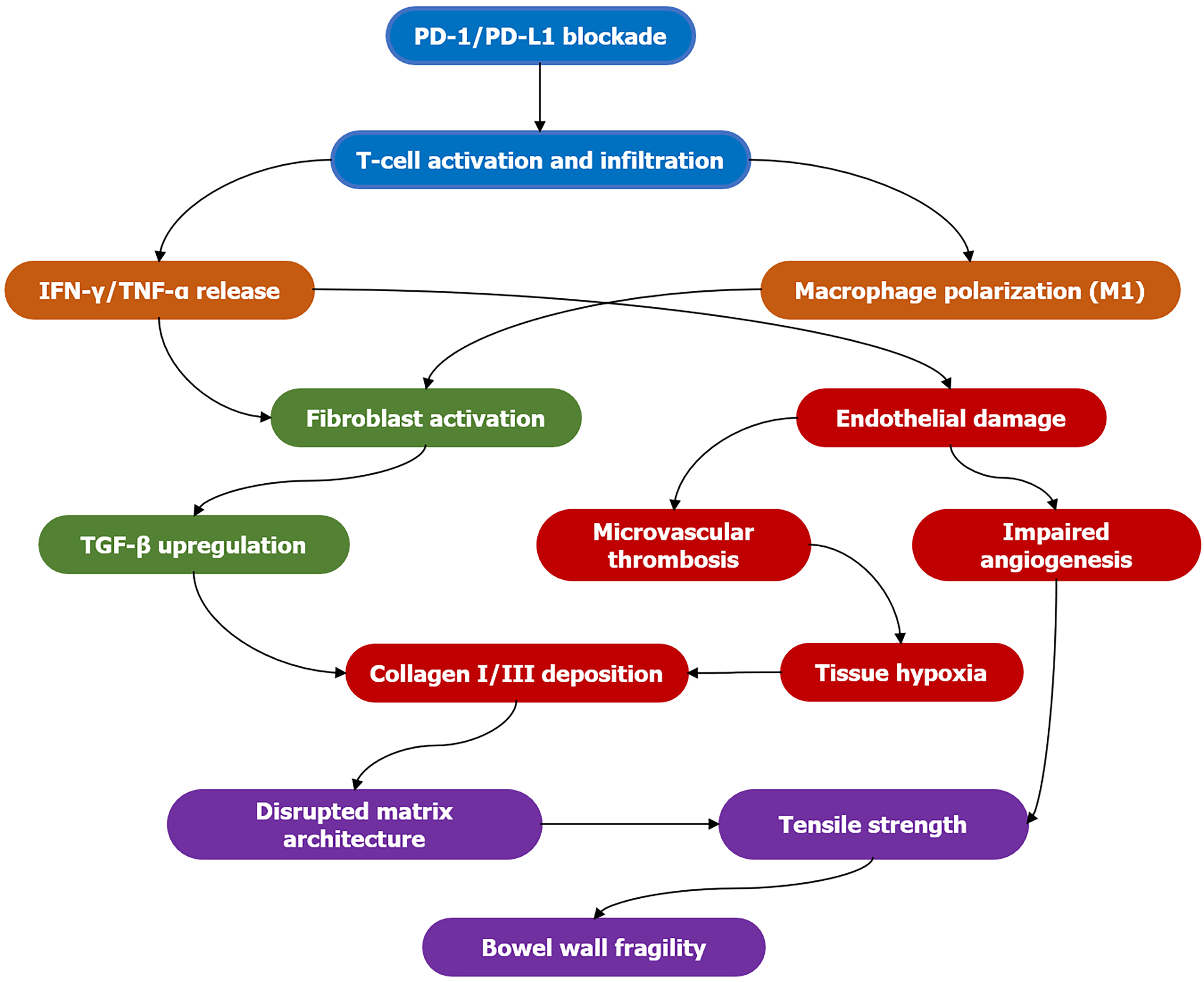

This remodeling involves complex biological processes (Figure 1), including: (1) Fibrosis: Persistent inflammation triggers fibroblast activation and excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition[13]. Although this is initially a reparative response, dysregulated fibrosis replaces functional tissue with stiff, acellular collagen, which compromises tensile strength and elasticity. Transforming growth factor-beta is a key driver of this process[14]; (2) Microvascular damage: Immune-mediated endothelial injury disrupts the microvasculature, resulting in ischemia and hypoxia[15]. These further fuel inflammation and fibrosis in a vicious cycle. Angiogenesis is often impaired in these scenarios[16]; (3) Altered matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity: Immune cells secrete MMPs that degrade ECM components. An imbalance between MMPs and their inhibitors can lead to excessive matrix breakdown, thereby weakening the tissue scaffold[17]; and (4) Impaired healing: In combination with these processes, chronic inflammation continually disrupts normal tissue repair mechanisms, resulting in the formation of structurally unsound scar tissue[18].

Figure 1 Pathogenesis of immune-mediated bowel wall remodeling.

Stage 1 (blue): Immune checkpoint inhibition is lifted, activating and infiltrating T cells; stage 2 (orange): Activated T cells and M1-type macrophages release large amounts of interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor alpha; stage 3 (green): Fibroblasts are activated and upregulate transforming growth factor beta, initiating the fibrosis program; stage 4 (red): Transforming growth factor beta promotes the deposition of type I/III collagen; simultaneously, inflammatory mediators cause vascular endothelial damage, microthrombosis formation, tissue hypoxia, and impaired angiogenesis; stage 5 (purple): Disordered collagen deposition disrupts the matrix structure, leading to reduced tissue tension and ultimately increased intestinal wall fragility. PD: Programmed death; IFN-γ: Interferon-gamma; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor alpha; TGF-β: Transforming growth factor beta.

These processes can architecturally compromise the bowel wall, rendering it fragile and failure-prone (despite it being tumor-free). This condition cannot be adequately detected using current standard imaging modalities, such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging, or even positron emission tomography-CT. These imaging techniques primarily assess tumor burden and gross morphology rather than the microscopic integrity or mechanical strength of the organ tissue[19]. It is critical to acknowledge the potential contributory role of prior chemotherapy, a common sequence in many cancer treatments. Although this particular patient received pembrolizumab as a primary treatment, many patients with MSI-H CRC receive chemotherapy before immunotherapy is considered. Cytotoxic chemotherapy agents are known to cause direct damage to the gastrointestinal mucosa and alter the tumor microenvironment by inducing stromal injury, promoting a pro-fibrotic state, and increasing epithelial permeability[20]. This chemotherapy-induced “priming” of the tissue could potentially lower the threshold for or exacerbate subsequent immune-mediated injury upon ICI administration, leading to more severe remodeling and fragility. The interaction between chemotherapy-induced damage and immunotherapy-driven inflammation warrants further mechanistic investigation.

SURGICAL PLANNING IN THE ICI ERA: A CALL FOR REASSESSMENT

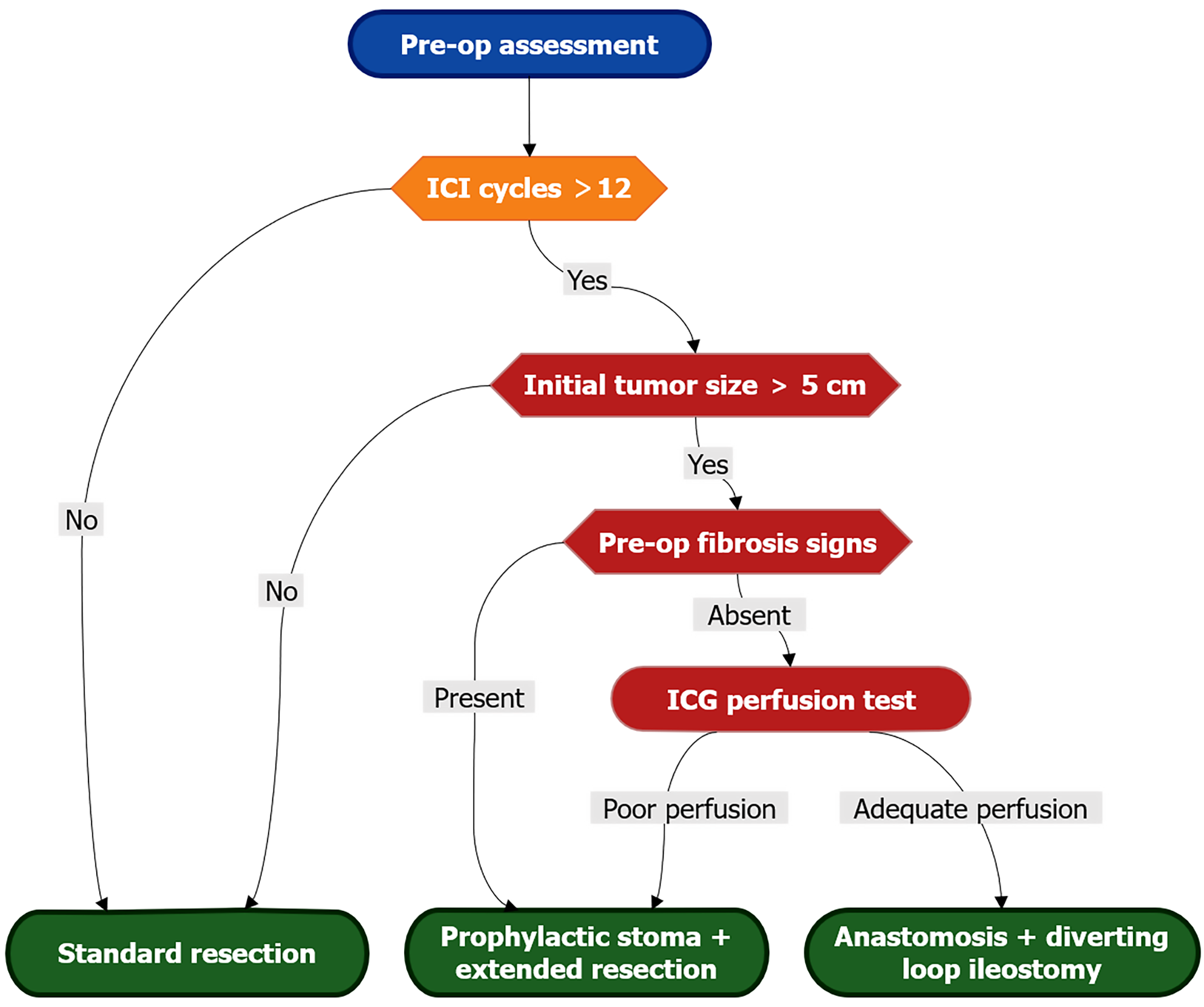

The United States Food and Drug Administration approved ipilimumab in 2011 as the first CTLA-4 inhibitor for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. The ICI era is not merely a temporal label, but a systemic transformation in cancer treatment. It marks a shift from purely cytotoxic paradigms to immune-centric treatment sequencing, introduces novel response patterns that challenge conventional radiographic and pathologic endpoints, and necessitates the recalibration of surgical timing based on immune-related toxicities and more favorable survivability. This landmark case necessitates an urgent reevaluation of surgical strategies for patients exhibiting major responses to neoadjuvant or definitive ICI therapies, particularly in MSI-H CRC (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Surgical risk stratification algorithm.

Evidence-based decision pathway for resection planning in immune checkpoint inhibitor-treated patients. High-risk criteria (red) include: > 12 immune checkpoint inhibitor cycles, initial tumor > 5 cm, or radiologic fibrosis signs (loss of mural stratification, SUVmax 2-4 on fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography, or elastography stiffness > 8 kPa). Mandatory intraoperative indocyanine green perfusion assessment guides anastomotic safety: Segments with perfusion delay > 30 seconds or bursting pressure < 25 mmHg require diversion. Prophylactic stoma is indicated when ≥ 2 major risk factors coexist. ICI: Immune checkpoint inhibitor; ICG: Indocyanine green.

The reassessment of surgical planning should include: (1) Heightened preoperative suspicion: Surgeons must be acutely aware that radiological evidence of clinical complete response and the disappearance of all visible tumors don’t necessarily equate to a structurally normal bowel wall and may not be predictive of pCR. A history of prolonged ICI therapy (such as the 36 cycles reported in this case), prior irAEs (especially colitis), or bulky initial tumors causing significant desmoplasia should raise concern about potential bowel wall fragility[10,21]; (2) Reconsidering surgical timing and the necessity of resection: Although organ preservation is desirable, this case highlights that leaving a heavily pretreated, potentially fibrotic bowel segment in situ is associated with an undetermined risk of delayed perforation or stricture. Surgery itself also poses risks to fragile tissue. The optimal timing of surgery post-ICI cessation remains unknown and requires thorough investigation. However, resection should typically be performed earlier in responders to mitigate the risks associated with prolonged tissue remodeling[22]; (3) Intraoperative vigilance and technique: Laparoscopic entry and dissection near the tumor site warrant extreme caution, and gentle tissue handling is paramount. Surgeons should meticulously inspect the bowel segment that harbored the initial tumor for any signs of thinning, fibrosis, or discontinuity before surgical mobilization. A wider margin of apparently normal bowel tissue proximal and distal to the fibrotic segment should be considered for resection to ensure anastomotic security. Techniques such as indocyanine green perfusion assessment may be valuable in this assessment[23]; (4) Prophylaxis: In high-risk scenarios (e.g., evidence of extensive fibrosis on preoperative imaging, long ICI treatment duration, prior obstruction/irAE, or intraoperative signs of significant bowel wall fragility), prophylactic stoma formation should be strongly considered even when anastomosis appears technically feasible. This provides a critical safety net should anastomotic failure occur due to poor tissue quality. Temporary diversion may be preferable to catastrophic leaks[24]; and (5) Pathology: Close communication with pathologists is essential. Beyond tumor staging, a detailed histological assessment of the resected bowel wall is crucial to characterize the extent of fibrosis, inflammation, and vascular changes. Special stains (e.g., trichrome for collagen, CD31/CD34 for vasculature) and molecular analysis (e.g., immune cell profiling, fibrosis markers) can provide insight into the mechanisms of the tissue damage[25].

MORE THAN THE SCALPEL: MULTIDISCIPLINARY IMPERATIVES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

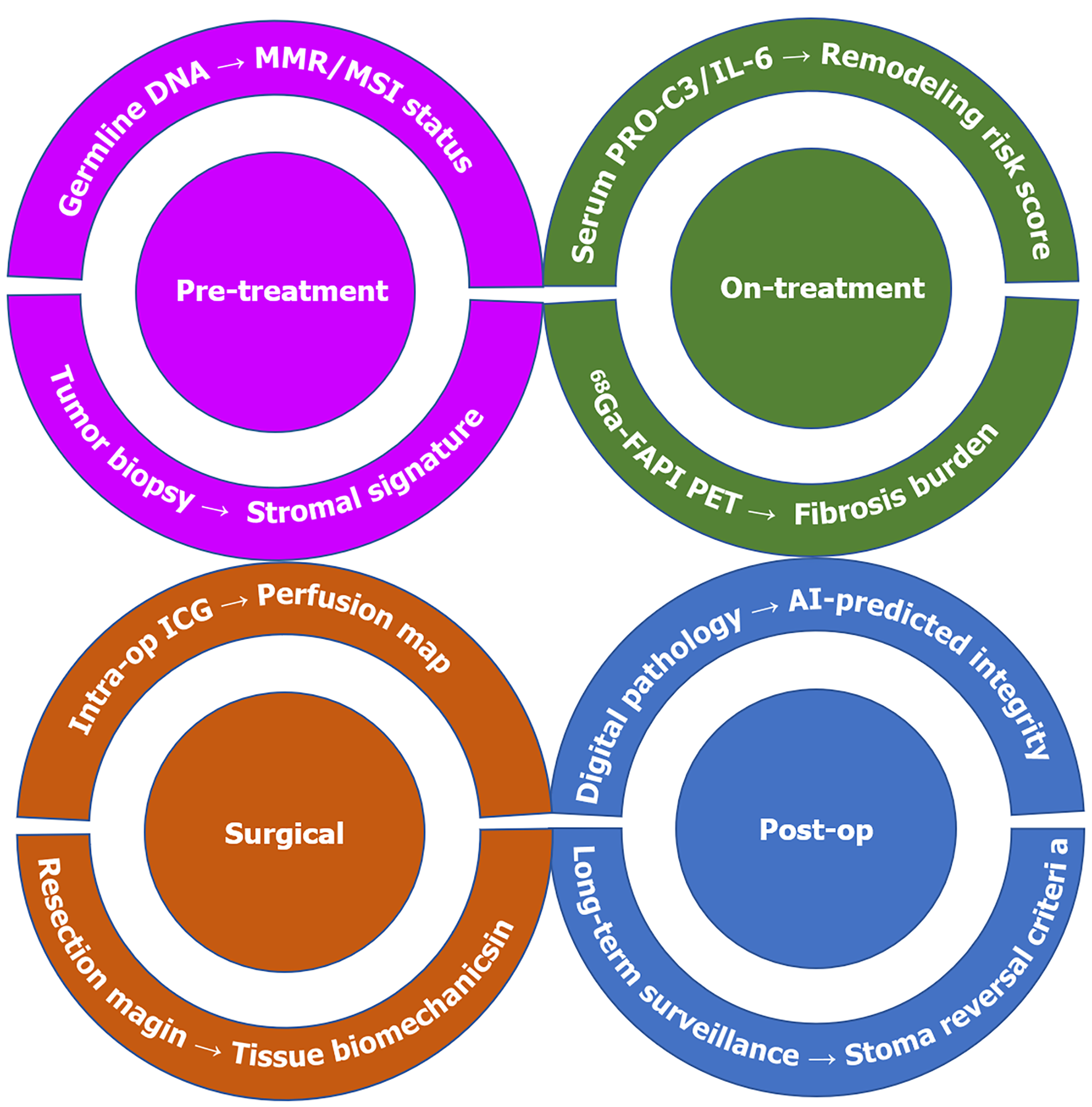

Addressing this emerging challenge extends well beyond the operating room and demands a concerted multidisciplinary effort (Figure 3). First, there is an urgent need for biomarkers to identify patients at high risk for severe tissue remodeling to avoid catastrophic events. Potential biomarker candidates include: (1) Circulating markers: Serum/plasma levels of ECM turnover products (e.g., N-terminal type III collagen, C-terminal type VIa3 collagen), inflammatory cytokines (e.g., interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha), or markers of endothelial damage (e.g., vascular cellular adhesion molecule-1, angiopoietin-2)[26,27]; (2) Imaging biomarkers: Advanced magnetic resonance imaging techniques (e.g., magnetization transfer imaging, diffusion kurtosis imaging) or positron emission tomography tracers that target fibrosis (e.g., 68Ga-FAPI-04) or inflammation could be used to detect microstructural changes that precede catastrophic failure[28,29]; and (3) Tissue-based biomarkers: Analyzing pretreatment biopsies for specific immune cell infiltrates (e.g., high CD8+/Treg ratios, macrophage polarization) or stromal signatures could predict the severity of subsequent tissue remodeling[30].

Figure 3 Multidisciplinary risk mitigation framework.

Translational framework for predicting and mitigating bowel wall fragility across treatment phases. Pre-treatment: Stromal gene signatures (Type III collagen/Matrix metallopeptidase 7 ratio) from biopsies predict remodeling propensity. On-treatment: Serum N-terminal type III collagen (type III collagen fragment) > 25 ng/mL and 68Ga-FAPI positron emission tomography SUVmax > 6 signal active fibrosis. Surgical: Assess the biological resilience of intestinal wall tissue. Post-op: AI-powered digital pathology (collagen orientation index) informs stoma reversal timing. MMR: Mismatch repair; MSI: Microsatellite instability; PRO-C3: N-terminal propeptide of collagen type 3; IL-6: Interleukin-6; PET: Positron emission tomography; ICG: Indocyanine green; AI: Artificial intelligence.

Second, imaging surveillance strategies need to be refined. The standard response evaluation criteria for solid tumors are insufficient. Radiologists require specific training and protocols for scrutinizing the bowel wall at the initial tumor site for subtle signs of wall thickening, fat stranding, loss of mural stratification, or pneumatosis - even in the absence of residual mass - that might indicate fragility[19].

Third, mitigating strategies should be explored thoroughly. Research is needed to confirm whether concurrent or sequential therapies can modulate fibrosis without compromising anti-tumor efficacy. Potential approaches include short courses of antifibrotics (e.g., pirfenidone, nintedanib) after a tumor response is achieved, or the use of agents that target specific fibrotic pathways (e.g., transforming growth factor-beta inhibitors)[31]. The role of microbiome modulation in preventing chronic inflammation also warrants investigation[32].

Fourth, the roles of alternative immune checkpoints such as lymphocyte-activation gene 3, T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3, and T-cell immunoreceptor with Ig and immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif domains must be evaluated[33]. Primary and acquired resistance to PD-1/CTLA-4 blockade is often mediated by the compensatory upregulation of these alternative immune checkpoints. Novel agents that target these pathways are currently entering clinical practice to address immune checkpoint blockade resistance and enhance anti-tumor immunity. However, the impact of these agents on immune-mediated tissue remodeling remains unknown. Dual checkpoint blockade could potentially amplify off-target tissue damage. Conversely, more precise targeting could potentially reduce it. Therefore, future research should concurrently evaluate the efficacy and tissue-specific toxicity profiles of these next-generation immunotherapies.

Finally, there is a need for prospective registries and trials involving a systematic collection of data on surgical complications, tissue pathology, and long-term outcomes in patients treated with ICI as they undergo surgery. Dedicated clinical trials are needed to compare different surgical approaches (e.g., resection vs watchful waiting in clinical complete response, either with or without diversion) and to evaluate potential protective pharmacologic interventions.

CONCLUSION

This remarkable case of spontaneous colonic transection following pembrolizumab-induced pCR is not merely an anomaly; rather, it is a sentinel event that reveals a previously underappreciated dimension of ICI toxicity. It shatters the assumption that tumor regression equates to restored organ integrity. Potent immune activation that drives tumor cell death can also induce parallel processes (i.e., fibrosis, vascular damage, and impaired healing) that silently undermine the mechanical strength of the bowel wall. Current imaging modalities provide an alarmingly incomplete picture of this risk. As ICIs become a standard neoadjuvant therapy for MSI-H CRC with organ preservation as an enticing goal, this case imposes a critical mandate for caution and adaptation. Surgeons must therefore approach post-ICI bowel surgery with heightened suspicion for fragility, modify their techniques accordingly, and embrace prophylactic stomas when elevated risk is established. The broader oncology community must prioritize the development of biomarkers to predict tissue vulnerability and novel imaging techniques to visualize it. Multidisciplinary collaboration is essential to achieve this goal. The benefits of immunotherapy should not be overshadowed by preventable structural complications. Recognizing and mitigating the delayed consequences of immune-mediated tissue remodeling represents the next frontier in improving safety and long-term outcomes for patients who benefit from these groundbreaking agents. Although the eradication of tumors is a triumph, the integrity of the surviving organ remains paramount.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author’s Membership in Professional Societies: Chinese Medical Education Association Committee for the Promotion of Basic and Clinical Research, CPBCR-0195; Member of the Digestive Endoscopy Branch of the Cross-Strait Medical and Health Exchange Association, ZXHNJ-1-163.

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade B

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: Tahri A, Post Doctoral Researcher, Italy S-Editor: Bai SR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG