Published online Nov 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i33.110976

Revised: July 19, 2025

Accepted: October 21, 2025

Published online: November 26, 2025

Processing time: 154 Days and 17.2 Hours

Intensive care unit (ICU) acquired sarcopenia and myosteatosis are increasingly recognized complications of critical illness, characterized by a rapid loss of ske

Core Tip: The growing recognition of intensive care unit (ICU)-acquired sarcopenia and myosteatosis underscores their profound impact on both short-term and long-term patient outcomes. They result from a convergence of metabolic, inflammatory, endocrine, and neuromuscular disturbances. These conditions lead to prolonged ventilation, extended ICU stays, higher mortality, and increased healthcare costs. With advancements in diagnostic technologies, such as computed tomography imaging and ultrasound, the link between ICU-related factors (e.g., mechanical ventilation, sepsis, and systemic inflammation) and muscle loss has become clearer. Early identification and management of these conditions are crucial for improving recovery rates and reducing the risk of disability. Current best practices emphasize a “bundled” approach: Optimize protein and calorie delivery, avoid deep sedation, when possible, mobilize early and often, and address deliriogenic and inflammatory factors that impede participation in rehab. These interventions, when implemented together, act synergistically to preserve muscle.

- Citation: Kataria S, Vinjamuri S, Juneja D. Muscle matters: Transforming the care of intensive care unit acquired sarcopenia and myosteatosis. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(33): 110976

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i33/110976.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i33.110976

Sarcopenia is traditionally understood as the progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and function associated with aging[1]. However, in the context of critical illness, a distinct form of muscle wasting occurs known as intensive care unit (ICU) acquired sarcopenia. Myosteatosis, often seen alongside ICU-acquired sarcopenia, involves the infiltration of fat into muscle tissue, which impairs muscle quality and function[1]. The growing recognition of ICU-acquired sarcopenia and myosteatosis underscores their profound impact on both short-term and long-term patient outcomes. These conditions lead to prolonged ventilation, extended ICU stays, higher mortality, and increased healthcare costs, while significantly impairing long-term function and quality of life, and are key contributors to post-ICU syndrome. With advancements in diagnostic technologies, such as computed tomography (CT) imaging and ultrasound (US), the link between ICU-related factors (e.g., mechanical ventilation, sepsis, and systemic inflammation) and muscle loss has become clearer[2]. Early identification and management of these conditions are crucial for improving recovery rates and reducing the risk of disability. This article seeks to synthesize current evidence on ICU-acquired sarcopenia and myosteatosis, exploring their pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, clinical assessment, epidemiology, prognostic impact, and emerging management strategies. By understanding the mechanisms and outcomes of ICU-related muscle wasting, critical care teams can better identify high-risk patients and implement comprehensive interventions to reduce long-term disability. The mini-review also addresses the challenges in managing ICU sarcopenia and outlines future directions for improving patient recovery.

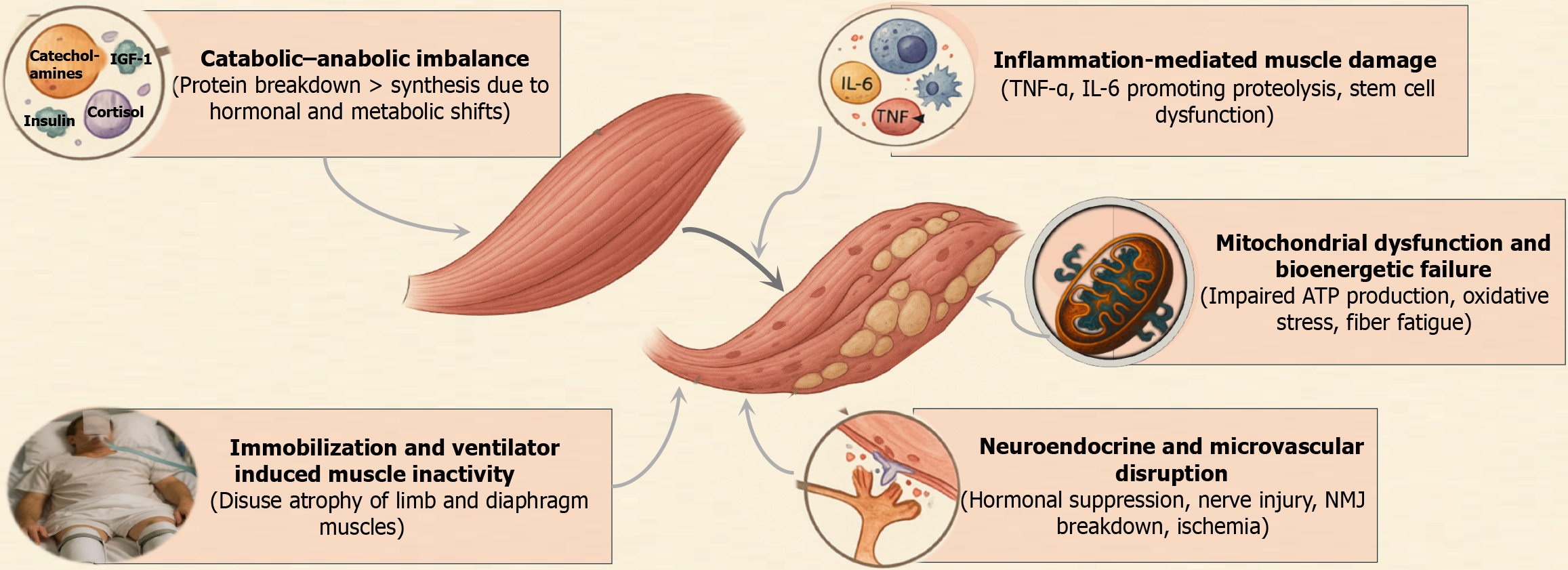

ICU-acquired sarcopenia and myosteatosis result from a convergence of metabolic, inflammatory, endocrine, and neuromuscular disturbances. The underlying mechanisms form a complex, interlinked cycle that accelerates muscle degradation and impairs recovery (Figure 1).

Critical illness initiates a profound metabolic shift toward catabolism, wherein muscle protein breakdown rapidly exceeds synthesis[3,4]. This imbalance is driven by elevated stress hormones (cortisol, catecholamines), insulin resistance, and suppression of anabolic signals. Muscle protein synthesis becomes markedly blunted within hours of ICU admission, while proteolytic pathways such as the ubiquitin – proteasome and autophagy systems are upregulated. One study demonstrated persistently elevated muscle protein breakdown throughout the first ICU week, despite nutritional support[5].

Amino acids are diverted from muscle to sustain gluconeogenesis and acute-phase protein production, leading to net muscle loss[6]. Simultaneously, anabolic hormones such as insulin, insulin growth factor-1, and testosterone are either suppressed or rendered ineffective due to receptor resistance, compounding the deficit in protein synthesis. This leads to a sustained negative nitrogen balance and drives significant muscle atrophy.

Mitochondrial health is critical for muscle function, especially in type I, fatigue-resistant fibres. In ICU patients, mitochondrial content and enzymatic activity in muscle fibres are significantly reduced due to sepsis and multi-organ failure. Muscle biopsies from patients with ICU-acquired weakness (AW) consistently show impaired mitochondrial respiration, reduced density, and evidence of bioenergetic crisis[7].

An experimental sepsis study demonstrated that persistent muscle weakness was more closely associated with mitochondrial dysfunction than with muscle mass loss alone[8]. Disruption of mitochondrial fission-fusion dynamics, accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and impaired adenosine triphosphate synthesis further damage muscle cells, limiting their regenerative capacity. Even after the resolution of acute illness, these defects can hinder muscle recovery and contribute to chronic weakness.

ICU-AW has long been recognized as a major sequela of systemic inflammatory response syndrome in critically ill patients, with inflammation serving as the predominant pathogenic driver[9]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α are central mediators of muscle wasting in critical illness. They activate muscle catabolic pathways by stimulating the ubiquitin–proteasome system and upregulating E3 ligases like atrogin-1 and MuRF-1[10,11]. IL-6 infusion has been shown to directly induce muscle protein degradation and fiber atrophy in experimental models.

In sepsis or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), a cytokine storm results in persistent systemic inflammation, marked by high circulating levels of IL-6 and TNF-α. These cytokines not only promote proteolysis but also impair satellite cell-mediated muscle regeneration. Infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages into muscle tissue further exacerbates degradation through the release of ROS and proteolytic enzymes. Elevated IL-6 levels on ICU admission have been correlated with reduced skeletal muscle area and density, as well as poor endurance and mortality[12].

Immobilization is nearly universal in critically ill patients and is a potent, independent contributor to muscle atrophy. Without mechanical loading, skeletal muscles undergo rapid disuse atrophy, characterized by decreased protein synthesis and shrinkage of muscle fibres.

Sedation, neuromuscular blockade, and bed confinement reduce stimulation of limb muscles, while mechanical ventilation causes diaphragm inactivity. Controlled ventilation, in particular, leads to ventilator induced diaphragmatic dystrophy (VIDD), marked by diaphragm fibre atrophy and reduced contractile strength. One study showed a 32% reduction in diaphragm thickness within 72 hours of full ventilator support[4]. Similarly, limb muscle wasting occurs at a rate of approximately 2% quadriceps loss per day in the first ICU week[4].

Immobilization also induces insulin resistance in muscle tissue and promotes intramuscular fat accumulation, contributing to myosteatosis. As such, physical inactivity not only reduces muscle quantity but also deteriorates muscle quality, reinforcing the importance of early mobilization (EM).

Critical illness alters the normal crosstalk between the immune and endocrine systems. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis becomes dysregulated, initially showing hyperactivity (excess cortisol) and later progressing to relative adrenal insufficiency. Excess glucocorticoids promote muscle breakdown and inhibit protein synthesis, a phenomenon evident in steroid myopathy.

Additionally, growth hormone (GH) resistance develops – leading to low insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) bioavailability in muscle tissues, despite elevated serum GH levels[13]. Hypogonadism is also common; critically ill men frequently exhibit suppressed testosterone levels, removing another anabolic stimulus. Myokine signalling, normally triggered by active muscle contraction, is impaired in bed-bound patients. As a result, the anti-inflammatory effects of myokines like IL-10 are absent, while pro-inflammatory cytokines persist unchecked.

Immune cell infiltration into muscle tissues and persistent systemic inflammation exacerbate myocyte injury. Thyroid hormone dysregulation (euthyroid sick syndrome) and catecholamine surges further disrupt muscle metabolism. Collectively, these endocrine and immune disturbances drive a catabolic environment unfavourable to muscle preservation.

Sepsis and shock impair skeletal muscle perfusion via endothelial dysfunction, capillary leak, and coagulopathy[1]. Inadequate delivery of oxygen and nutrients contributes to localized ischemia and metabolic stress, particularly in metabolically active muscle fibers. This accelerates bioenergetic failure and tissue injury.

Concurrently, neuromuscular dysfunction arises from peripheral nerve injury (critical illness polyneuropathy), muscle fibre pathology [critical illness myopathy (CIM)], and neuromuscular junction (NMJ) impairments. Denervation results in rapid fibre atrophy, especially in type I fibres. Disruption at the NMJ, including reduced acetylcholine receptor density and morphological degeneration, impairs excitation-contraction coupling, reducing voluntary and reflexive muscle activation.

Biopsy studies in long-stay ICU patients have revealed focal muscle fibre necrosis in more than 50% of cases[5]. These structural disruptions underscore that weakness is not merely a matter of muscle loss but also of impaired neuromuscular integration.

Gender influences the pathophysiology of sarcopenia through distinct hormonal, metabolic, and molecular mechanisms that differentially affect muscle mass, strength, and quality. Age related declines in sex hormones such as testosterone in men and estrogen and progesterone in women drive sex specific muscle wasting through divergent effects on protein synthesis, mitochondrial function, and inflammation[14]. In men, higher myostatin and testosterone deficiency impair anabolic IGF-1/protein kinase B/mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) signalling, while in women, lower IGF-1, malnutrition, and estrogen deficiency after menopause disrupt mitochondrial quality control and protein synthesis. Muscle fiber composition also differs, with women having more type I fibers and men larger type II fibers, contributing to sex specific patterns of strength and mass loss[15]. In the ICU, female sex independently predicts ICU-AW, with women exhibiting greater insulin resistance, faster atrophy, and slower recovery than men.

Sarcopenia has been classically defined in aging populations and adapted for ICU settings. The European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2) in 2018 defined sarcopenia as a muscle disease (muscle insufficiency) with low muscle strength as the primary criterion, plus low muscle quantity/quality to confirm diagnosis, and poor physical performance to denote severe sarcopenia. In practice, EWGSOP2 recommends cut-off values such as handgrip strength < 27 kg (men) or < 16 kg (women) for low strength, and appendicular lean mass index < 7.0 kg/m2 (men) or < 5.5 kg/m2 (women) for low muscle mass [by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA)][16]. Physical performance is often assessed by gait speed (< 0.8 m/second) or the Short Physical Performance Battery. The Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS 2019) provides similar criteria tailored to Asian populations: (1) Low muscle mass (e.g. < 7.0 kg/m2 in men, < 5.4 kg/m2 in women by DEXA); (2) Plus low strength (grip < 28 kg men, < 18 kg women); and (3) Low usual gait speed (≤ 0.8 m/second)[17].

Both EWGSOP2 and AWGS now recognize “acute sarcopenia” as sarcopenia developing over less than 6 months, which would include ICU-acquired cases. In the ICU setting, however, standard measures like handgrip or gait speed are often not feasible in the acute phase as the patients may be unconscious or too ill to stand/walk. Therefore, ICU-specific definitions of sarcopenia rely on objective muscle mass measurements. While no universal ICU sarcopenia definition exists in guidelines, researchers commonly use imaging-based cut-offs derived from population studies. For example, low skeletal muscle index (SMI) on CT (cross-sectional muscle area at L3 vertebra normalized for height2) is often used to define sarcopenia in ICU patients[1]. Cut-off values around < 52 cm2/m2 in men and < 38 cm2/m2 in women at L3 have been applied (these values were originally derived from oncology cohorts as indicating low muscle mass)[18]. US measurements of quadriceps muscle may also define sarcopenia acutely – e.g. a small rectus femoris cross-sectional area (CSA) or rapid loss (> 10% in a week) suggests significant muscle catabolism[5].

Importantly, ICU sarcopenia definitions emphasize muscle quantity (since direct strength testing is limited), and often assume any ICU-acquired muscle mass loss is accompanied by functional impairment (ICU-AW). Clinically, ICU-AW is defined by medical research council (MRC) muscle strength score < 48/60 (averaged across 6 muscle groups) when the patient can cooperate. ICU-AW overlaps with sarcopenia but also includes neuropathic injury; still, it highlights the functional consequence of ICU muscle loss.

Myosteatosis is defined by excess intramuscular fat and reduced muscle fiber quality. On CT, skeletal muscle radiation attenuation is the key metric – lower attenuation [in Hounsfield units (HU)] indicates more fat infiltration in muscle. There is no single consensus cutoff for myosteatosis across all settings, but commonly used definitions (from oncology and hepatology literature) are mean muscle attenuation < 30 HU (often for obese patients) or < 41 HU (in normal body mass index patients) on a CT slice at L3[2,19]. Essentially, any value significantly below the typical approximately 50 HU of lean muscle suggests myosteatosis[20]. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), myosteatosis can be quantified by proton density fat fraction or T2 mapping, but MRI is seldom used in ICU. US can qualitatively assess echogenicity: Increased muscle echogenicity (appearing whiter on US) correlates with intramuscular fat and fibrosis, thus serving as a bedside indicator of myosteatosis when comparing to normative references[21].

Historically, electrophysiological evaluation [nerve conduction studies and electromyography (EMG)] was the definitive diagnostic approach for ICU-acquired neuromuscular impairment, as shown by Bolton et al[9]. However, practical constraints (edema, sedation, specialized expertise) limit routine use of EMG in critically ill patients. Clinicians have therefore turned to a combination of imaging-based techniques, biomarkers, and functional assessments to evaluate muscle mass and function. This multimodal strategy is essential because muscle loss and weakness develop early, often within the first week of ICU stay, and their severity varies widely with patient factors such as age, illness severity, and comorbidities[4].

CT and ultrasonography are the most utilized techniques for quantifying skeletal muscle. High-resolution axial CT scans (often at the third lumbar vertebra, L3) precisely measure muscle CSA and can characterize muscle quality via attenuation (HU). Specialized software or semi-automated analysis can quantify the CSA of muscle (in cm2) and calculate the SMI (SMI = area/height2)[19]. Its use in ICU research has revealed that a significant proportion of critically ill patients (up to approximately 60%-70%) have pre-existing muscle depletion on admission. CT-based metrics also have strong prognostic value with low L3 muscle area and density on admission being associated with higher mortality and longer ICU stays[22]. The advantages of CT are its accuracy and ability to assess muscle quality. It can differentiate muscle from fat pre

By contrast, US is a portable, radiation-free imaging modality that permits repeated bedside muscle measurements. Ultrasonography can readily visualize peripheral and respiratory muscles, making it invaluable for tracking ICU muscle changes over time. The most common targets are peripheral muscles like the quadriceps (rectus femoris and vastus intermedius) or the forearm muscles, and the diaphragm (for respiratory muscle assessment). Ultrasonography can measure muscle thickness or CSA and can also qualitatively assess muscle echogenicity (brightness). Notably, thickness measurements alone may underestimate muscle loss compared to full CSA, because a muscle can thin in one dimension but also shrink in width. Therefore, whenever feasible, CSA or muscle layer thickness (e.g. sum of quad muscle thick

Dynamic muscle ultrasonography appears superior to static CT morphometry. In a recent prospective cohort study, day-1 biceps thickness measured by bedside US predicted inhospital mortality with an area under the curve of 0.84 and 100% sensitivity, whereas admission L3SMI on CT showed no link to frailty or survival. This supports real-time US as the more practical and prognostically powerful metric in the ICU[24].

Other imaging modalities have more limited roles. MRI provides exquisite detail on muscle volume and composition and is considered a research gold-standard alongside CT for body composition analysis. However, MRI is rarely feasible in ICU patients due to cost, time, and safety constraints. DEXA can accurately measure lean body mass but requires transporting the patient to a DEXA scanner, which is impractical during critical illness. Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) devices offer a bedside estimate of lean mass by measuring body water compartments; while appealing in concept (non-invasive, rapid), BIA’s accuracy in ICU patients is poor due to fluid shifts and edema that alter impedance readings. Thus, CT and US remain the dominant imaging techniques in practice, CT for one-time definitive assessments of muscle mass and US for repeated monitoring (Table 1).

| Technique | Parameters measured | Advantages | Limitations | Clinical utility |

| CT scan | Skeletal muscle CSA; muscle attenuation (density) | Accurately quantifies muscle/adipose tissue, visualizes muscle quality, and serves as the reference standard for sarcopenia diagnosis | Requires radiation and ICU transport, unsuitable for frequent reassessments, costly, and limited to opportunistic snapshots | Baseline risk stratification using CT-derived low muscle mass predicts worse outcomes and has been correlated with mortality and ICU length of stay |

| Ultrasound | Muscle thickness; CSA; echo-intensity (grayscale) | Bedside, portable, radiation-free, low-cost, repeatable for monitoring, and assesses limb and respiratory muscles in real time | Operator-dependent, limited to specific muscles, and affected by edema or obesity | Enables monitoring of muscle wasting, early detection of ICU-acquired loss, and assessment of diaphragm and peripheral muscles to guide rehabilitation |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | Muscle volume; detailed anatomy and composition | Provides highly accurate muscle volume and fat measurement without radiation | Infeasible in critically ill due to transport, time, cost, and contraindications with ICU devices or instability | Used in research to study muscle architecture; rarely applied clinically in ICU due to logistical constraints |

| Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scan | Lean body mass; appendicular muscle mass via dual X-ray absorption | Gold standard for body composition and precise in diagnosing chronic sarcopenia | Requires transport, affected by fluid shifts, involves low radiation, and unsuitable for ICU monitoring | Useful for nutritional assessment post-ICU or in research; impractical during acute ICU stay |

| Bioelectrical impedance analysis | Total body water, estimated fat-free mass (via electrical impedance) | Bedside, quick, non-invasive, and portable | Assumes normal hydration; inaccurate with fluid imbalance, vasopressors, edema, or position changes | Limited in ICU; useful for trend tracking by nutrition teams but confounded by fluid shifts |

Biochemical markers for muscle loss in critical illness are an area of active investigation. Unlike imaging, no single biomarker provides a direct, reliable measure of skeletal muscle mass. However, several surrogate markers can reflect muscle protein breakdown or anabolic state.

One classic indicator is 3-methylhistidine (3-MH), an amino acid released during actin-myosin protein degradation. Elevated 3-MH excretion in urine signifies accelerated myofibrillar protein breakdown, which has been observed in cachectic states. In the ICU, 3-MH could theoretically gauge the intensity of muscle catabolism, but its clinical use is limited as dietary meat intake and renal function influence levels, and specialized assays are required.

Another related measure is the creatinine height index, based on the concept that creatinine production is proportional to muscle mass. Critically ill patients often have low creatinine generation relative to body size, consistent with muscle wasting; however, acute kidney injury or fluid shifts confound this metric, making it unreliable in ICU practice. However, the creatinine-to-cystatin C ratio serves as a non-invasive biomarker of muscle mass. While creatinine originates from muscle metabolism, cystatin C reflects glomerular filtration independently of muscle mass. A low creatinine-to-cystatin C ratio indicates muscle depletion relative to renal function. In ICU patients, low ratios on admission correlate with higher frailty, ICU-AW, prolonged ventilation, and increased 90-day mortality. A threshold < 0.67 has been associated with adverse outcomes, independent of illness severity[25,26].

In routine critical care, muscle enzyme levels are sometimes monitored, for example, creatine kinase. However, their utility for chronic atrophy is poor. Creatine kinase is typically normal or only mildly elevated in ICU-AW. A large rise in creatine kinase primarily indicates acute muscle injury (rhabdomyolysis) rather than the insidious atrophy of CIM. Inflammatory markers and acute-phase proteins provide indirect evidence of the catabolic milieu affecting muscle. Elevated C-reactive protein and IL-6 reflect systemic inflammation which drives proteolysis; persistent inflammation has been linked to prolonged muscle wasting and delayed functional recovery in ICU survivors[27]. Nevertheless, these markers are non-specific, as they signal overall illness severity rather than quantifying muscle loss per se.

Certain hormonal and growth factors have also been studied: Low levels of IGF-1 and testosterone, or high levels of myostatin and cortisol, are associated with muscle atrophy in critical illness, aligning with the suppressed anabolic signalling seen in ICU patients. These endocrine markers reinforce our pathophysiological understanding but are not used clinically to monitor muscle status. Myostatin [growth differentiation factor-8 (GDF-8)] is a powerful autocrine brake on satellite cell activation and protein synthesis. In ICU models, it follows a biphasic course; initial upregulation of proteolytic genes, then a sharp fall in myostatin transcripts as wasting advances[28,29]. In septic mice, genetic deletion or antibody blockade of GDF-8 conserves lean mass and even improves survival, underscoring its clinical relevance[30]. By contrast, GDF-5 drives myogenesis and supports neuromuscular integrity; prolonged recombinant GDF-5 reverses age related muscle loss, boosts maximal force, and stabilises NMJs[31]. A phenotype of high GDF-8 and low GDF-5 may suggests impaired regeneration and active muscle loss, warranting early anabolic or rehabilitative interventions.

In summary, while biomarkers can support the assessment of muscle wasting – especially by indicating ongoing catabolism or anabolic deficits – they cannot replace imaging or functional testing at present. Table 2 outlines key biomarkers studied in ICU-acquired muscle weakness.

| Biomarker | What it measures | Advantages | Limitations | Clinical utility |

| 3-MH (urine) | Myofibrillar protein breakdown (release of 3-MH from muscle proteins) | Specific marker of skeletal muscle catabolism and quantifies muscle protein breakdown | Affected by diet and renal function; not routinely available in clinical laboratories | Used in research to quantify muscle breakdown; rarely clinical due to confounders and complexity |

| Creatinine-based indices (e.g., creatinine height index) | Muscle mass proxy based on creatinine production (muscle-derived creatinine per 24 hours or per body size) | Simple, historically used in nutrition assessment; based on urine or blood creatinine | Assumes stable renal function, confounded by fluid shifts, and insensitive to acute changes | Limited in ICU; low creatinine may indicate low muscle mass but requires caution without renal failure |

| Muscle enzymes (e.g., CK) | Muscle fiber damage or necrosis (CK leaks into blood with muscle membrane injury) | Widely available; elevated CK indicates acute muscle injury (e.g., rhabdomyolysis) | Not a marker of chronic atrophy; normal CK can mask wasting, while elevations may reflect other injuries | Detects acute muscle injury but not ICU sarcopenia; normal CK with weakness suggests critical illness myopathy over necrosis |

| Inflammatory markers (CRP, interleukin-6, tumour necrosis factor-α) | Systemic inflammatory response driving catabolic state | Easily measured (e.g., CRP); elevated levels reflect illness severity and catabolic drive | Non-specific; do not assess muscle directly; sustained inflammation promotes muscle breakdown and organ dysfunction | Helps identify patients at risk of muscle loss from catabolic inflammation; highlights need for anti-inflammatory and nutritional strategies, but not a direct muscle metric |

| Hormonal signals (e.g., IGF-1, cortisol, myostatin) | Anabolic vs catabolic hormonal milieu (IGF-1 promotes muscle synthesis; myostatin inhibits it; cortisol catabolic) | Reflect muscle growth pathway activity; low IGF-1 or high myostatin associate with atrophy in research | Research-only, with specialized assays, complex interactions, and no ICU-specific reference ranges | Studied as therapeutic targets (e.g., myostatin inhibitors, growth hormone axis) in ICU trials; not for routine monitoring |

Functional testing remains the clinical cornerstone for diagnosing ICU-AW. MRC sum score, assessing six bilateral muscle groups, defines ICU-AW when < 48/60 in cooperative patients. For rapid, objective assessment, handgrip dynamometry provides numeric strength values and is independently associated with ICU mortality (e.g., grip < 11 kg in men or < 7 kg in women)[25]. In unresponsive patients, neuromuscular electrophysiology (e.g., nerve conduction studies, EMG) can helps detect early polyneuropathy or myopathy. As patients recover, functional performance tests such as the 5-time sit-to-stand, timed up and go, or 6-minute walk test assess mobility and predict long-term outcomes (Table 3)[5,30]. A tiered approach is used in clinical practice, employing volitional tests if the patient is alert, otherwise relying on imaging or electrophysiology. Combining modalities provides a comprehensive picture of neuromuscular function.

| Assessment method | Description and parameters | Advantages | Limitations | Clinical utility |

| MRC sum score (manual muscle testing) | Clinician-performed manual strength exam of 6 muscle groups bilaterally (scored 0–5 each; max score 60). ICU-AW defined by MRC < 48 | No equipment needed; bedside clinical exam. Standardized scoring system with prognostic significance. Validated for diagnosing ICU-AW when patient is awake | Feasible only in conscious, cooperative patients (often < 50% of ICU patients early on). Subjective effort can vary; inter-rater variability in scoring. Cannot detect subclinical weakness in sedated patients | Primary diagnostic tool for ICU-AW once patient can participate. Identifies patients requiring rehab interventions; a score < 48 correlates with difficulty in weaning and prolonged ICU stay |

| Handgrip dynamometry | Patient squeezes a handheld dynamometer to measure grip strength (kg force). Typically, the best of 2-3 attempts is recorded for each hand | Objective, numeric measure of strength. Quick (< 1 minute) and reproducible. Can be done in bed; minimal patient movement required (just hand squeeze) | Requires patient arousal and minimal cognitive function. Assesses primarily forearm/hand strength (may not reflect leg weakness). Grip may be impaired by local hand issues (arthritis, injury) | Useful surrogate for global strength; prognostic indicator (low grip strength on ICU admission associated with higher mortality). Can track strength improvements over ICU stay and guide nutrition/physio needs |

| Electrophysiological studies (nerve conduction studies and EMG) | Nerve conduction studies: Stimulate motor nerves and record muscle action potentials; EMG: Needle electrodes measure muscle electrical activity at rest and contraction. Detects CIP or CIM | Does not require patient cooperation or movement. Can diagnose the presence of neuropathy vs myopathy, aiding etiologic understanding. Highly sensitive to electrical changes in muscle/nerve function | Specialized personnel and equipment needed (not available in all ICUs). Time-consuming and somewhat uncomfortable (needle EMG). Edema and electrical noise in ICU can interfere with signals. Primarily diagnostic, not for routine monitoring of recovery | Confirms ICU-AW and differentiates CIP vs CIM in patients with unexplained or severe weakness. Often employed if weakness is profound or prolonged and other causes need exclusion. Helps prognostication (e.g., pure CIP has different recovery profile than CIM) |

| Functional mobility tests (e.g., sit-to-stand, 6-minute walk, etc.) | Performance-based tests of muscle function and endurance administered when patient is ambulatory. 5 × sit-to-stand: Time to rise from chair 5 times; 6-minute walk test: Distance walked in 6 minutes, etc. | Directly assesses integrated muscle function, balance, and endurance. Relates to real-world functional outcomes and independence. Useful for discharge planning and rehab goals | Not applicable during acute ICU phase (requires patient to be awake, off most support, and able to stand/walk). Influenced by cardiopulmonary fitness and motivation in addition to muscle strength. Safety concerns if patient is frail (risk of falls) | Employed at ICU discharge or step-down to evaluate recovery. For example, a very low 5 × sit-to-stand performance at ICU discharge indicates ongoing weakness and high rehab needs. These tests connect ICU-acquired muscle deficits to patient-centered outcomes like mobility and quality of life after critical illness |

An optimal assessment of ICU muscle health uses a multimodal approach, leveraging the strengths of each modality while mitigating their individual limitations. Early in an ICU course (when many patients are sedated), imaging and biomarkers can signal muscle loss before clinical examination is possible. US tracking of muscle size, combined with monitoring of catabolic markers (e.g. nitrogen balance or inflammatory indices), may identify patients at risk for ICU-AW so that preventive strategies (nutritional support, EM) are implemented. Once patients awaken, formal strength testing and functional assessments confirm the diagnosis and guide rehabilitation. Figure 1 illustrates this multimodal strategy. For instance, a patient with low muscle mass on CT/US, elevated proteolysis markers, and poor volitional strength would be promptly diagnosed with ICU-acquired sarcopenia and enrolled in aggressive therapy. Conversely, discordant findings (e.g. preserved muscle mass on imaging but low strength) might prompt investigation for NMJ issues or critical illness neuropathy. Ultimately, combining imaging, biochemical, and functional modalities provides the most comprehensive evaluation of ICU-acquired muscle weakness, helping clinicians stratify risk, tailor interventions, and improve outcomes for critically ill patients.

ICU-acquired sarcopenia and myosteatosis significantly influence both short-term clinical outcomes and long-term recovery trajectories. During the acute phase, reduced muscle mass and quality directly impact mechanical ventilation outcomes. Weakness of respiratory musculature, particularly due to VIDD, undermines the patient’s ability to breathe spontaneously. A meta-analysis demonstrated that sarcopenic patients required an average of 1.2 additional days on mechanical ventilation compared to non-sarcopenic counterparts[32]. Moreover, spontaneous breathing trials are more likely to fail in those with low skeletal muscle area or diaphragmatic contractility, as shown in a cohort study where low diaphragm thickness or impaired contractile indices were linked with weaning failure. Yan et al[33] proposed that dynamic compliance-normalized mechanical power, a measure integrating respiratory load and muscle capacity, outperformed the traditional rapid shallow breathing index in predicting weaning success – highlighting how sarcopenia blunts the predictive value of static parameters.

Muscle wasting also contributes to longer ICU and hospital stays. Jiang et al’s meta-analysis[32] found that sarcopenia increased ICU length of stay by approximately 1.3 days, and similar trends were noted for overall hospitalization duration. Patients with ICU-AW, defined by an MRC score < 48, frequently require prolonged rehabilitation before ICU discharge due to persistent functional limitations. Furthermore, sarcopenic patients are more prone to immobility-related complications, such as pneumonia, pressure ulcers, and urinary tract infections, which further delay recovery.

Beyond hospitalization, the long-term consequences of ICU-acquired sarcopenia are profound. Persistent physical disability is a dominant feature of post-intensive care syndrome. In longitudinal studies such as the ARDSNet Long-Term Outcomes Study and the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group’s 5-year ARDS cohort, ICU-AW at discharge was associated with markedly reduced 6-minute walk distances and diminished return-to-work rates, with many survivors’ requiring long-term rehabilitation or assisted living. Quality of life scores in these patients remained significantly impaired in physical domains up to one year post-ICU[34].

The impact extends to survival outcomes as well. Hermans et al[35] demonstrated a strong association between ICU-AW and increased 1-year mortality, independent of acute severity scores. Similarly, Herridge et al[36] reported late mortality in ARDS survivors persisting years after discharge, partially attributable to residual muscle dysfunction and frailty. Sarcopenia also drives greater healthcare utilization: Readmissions are more frequent due to functional deconditioning, and the need for long-term acute care facilities or skilled nursing homes is higher in this population[34,35]. In the EPaNIC trial’s 2-year follow-up, physical functioning remained impaired in both early and late parenteral nutrition groups, underscoring that muscle recovery is often incomplete regardless of nutritional strategies during ICU stay[37].

The MEND-ICU study, which followed patients mechanically ventilated for over one week, found that muscle strength and mass showed only partial recovery at six months, while the National Institutes of Health ARDS Network reported that survivors had, on average, only 75% of predicted 6-minute walk distance at five years[36]. Together, these findings establish ICU-acquired sarcopenia not just as an acute complication but as a persistent determinant of morbidity and mortality. In clinical terms, muscle mass and quality at ICU discharge should be viewed as vital prognostic markers, with implications for discharge planning, rehabilitation referrals, and long-term survivorship care.

It is also important to mention that research consistently shows a strong association between sarcopenia and depressive symptoms. A systematic review and meta-analysis reported a 28% prevalence of depression in individuals with sarcopenia[38]. Longitudinal studies confirm this relationship, with sarcopenia independently predicting depressive symptoms and showing a stronger predictive value for later depression than the reverse. Although less studied, anxiety also appears linked to sarcopenia. In a study of 407 elderly patients, sarcopenia was marginally associated with anxiety symptoms. Among hemodialysis patients those with sarcopenia had significantly higher anxiety scores compared to those without[39].

Management of ICU-acquired sarcopenia necessitates a multimodal strategy targeting both catabolic drivers and anabolic deficits. While no singular intervention reverses muscle loss during critical illness, the integration of early nutrition, physical rehabilitation, and select pharmacologic strategies has shown promise in attenuating severity and improving recovery outcomes.

Optimizing protein intake remains foundational. Guidelines from ESPEN recommend 1.3–2.0 g/kg/day of protein, initiated early in the ICU course to mitigate catabolism. High-protein enteral nutrition, even when delivered alongside moderate caloric deficits (permissive underfeeding), may preserve lean body mass more effectively than standard regimens[40]. The EPaNIC trial, while showing no long-term functional difference between early and late parenteral nutrition groups, underscored the complexity of nutrition timing, indicating that early amino acid provision – rather than total caloric load – might be more critical for muscle outcomes[41].

Amino acid formulations enriched with leucine or its metabolite β-hydroxy β-methyl butyrate (HMB) may provide additional anabolic stimulus by activating mTOR pathways[42]. Trials in elderly and chronically ill populations suggest that HMB supplementation improves lean body mass and function, though large-scale ICU trials remain pending[43,44]. Omega-3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic/docosahexaenoic acids), recognized for their anti-inflammatory effects, have also been evaluated. While enteral immunonutrition failed to show benefit in the OMEGA trial[45], meta-analyses of parenteral omega-3 lipid emulsions have demonstrated reductions in infection risk and ICU length of stay, suggesting a potential indirect role in muscle preservation[46].

Micronutrient optimization is also important. Vitamin D deficiency, prevalent in ICU patients, has been linked to weakness, although the VITdAL-ICU trial did not demonstrate functional benefit from high-dose repletion. Magnesium and phosphate repletion are critical in addressing respiratory muscle weakness and impaired energy metabolism; observational studies confirm improved weaning outcomes with correction of these deficiencies[47,48].

Physical rehabilitation is increasingly recognized as a critical component of comprehensive ICU management. Prolonged immobility, sedation, and mechanical ventilation contribute to the rapid onset of ICU-AW, characterized by profound skeletal muscle atrophy, impaired neuromuscular function, and delayed recovery. Early implementation of structured rehabilitation strategies has emerged as a key intervention to mitigate these deleterious effects.

EM, defined as initiating physical activity (including passive or active-assisted movement) within 48-72 hours of ICU admission, is now considered standard of care in many ICUs. A landmark randomized controlled trial by Schweickert et al[49] demonstrated that combining daily sedation interruption with EM in mechanically ventilated patients significantly improved functional independence at hospital discharge and reduced the duration of delirium. Mechanistically, EM provides mechanical loading to muscle fibers, which helps counteract disuse atrophy, preserves motor unit recruitment, and improves neuromuscular coordination. However, EM may not completely reverse the anabolic resistance or catabolic milieu driven by systemic inflammation, endocrine dysfunction, and mitochondrial abnormalities associated with critical illness[50]. Furthermore, feasibility remains contingent on hemodynamic stability, sedation minimization, and mul

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) serves as a valuable adjunct to early rehabilitation, particularly for patients unable to engage in active exercise due to sedation, delirium, or hemodynamic instability. NMES involves the application of surface electrodes over major muscle groups to induce involuntary contractions, mimicking active move

The diaphragm is particularly vulnerable to disuse atrophy during mechanical ventilation, often resulting in VIDD, which can prolong weaning. Inspiratory muscle training (IMT) is a targeted intervention designed to strengthen the inspiratory muscles using threshold-resistance devices that impose graded inspiratory loads. Controlled studies have shown that IMT increases diaphragm thickness and improves maximal inspiratory pressure, leading to enhanced weaning success and faster liberation from mechanical ventilation[54]. IMT is typically initiated once patients can participate in spontaneous breathing trials and may be continued post-extubation as part of structured pulmonary rehabilitation. Importantly, early IMT has been associated with better long-term functional outcomes in survivors of critical illness, especially those with underlying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or heart failure.

Although anabolic steroids and testosterone are not routinely used in the ICU, they have shown benefit in specific populations such as burn or COPD patients. Oxandrolone, for instance, improved lean mass and wound healing in burn patients, but its broader application is limited due to concerns about hepatotoxicity and thrombosis[55]. Selective androgen receptor modulators, currently under investigation, offer the potential for targeted muscle anabolic effects with reduced side effects[56].

Anti-inflammatory therapies targeting IL-6 (e.g., tocilizumab) and TNF-α have been explored, particularly in coronavirus disease 2019. While IL-6 blockade improved survival in cytokine storm syndromes, its direct impact on muscle outcomes remains speculative[57-59]. Similarly, beta-agonists like salbutamol may provide anabolic effects via IGF-1 upregulation but lack strong ICU-specific data[60].

Creatine supplementation has a theoretical benefit by enhancing adenosine triphosphate regeneration, supporting mitochondrial function, and reducing oxidative stress. Although data are limited, studies in post-stroke and COPD populations have demonstrated improved muscle mass and performance with creatine supplementation[61,62]. How

Myostatin inhibitors (targeting GDF-8 or activin receptors) are under active investigation in cachexia syndromes. In early-phase trials, agents such as angiotensin converting enzyme-031 and anti-myostatin antibodies increased muscle volume, though translation into functional gains was inconsistent[63]. These agents offer future potential for ICU application, especially for chronically critically ill patients with persistent sarcopenia.

Recent technological innovations are poised to transform the early identification and management of ICU-acquired sarcopenia and myosteatosis. One of the most significant advancements is the application of artificial intelligence (AI) to radiologic imaging. AI-assisted segmentation of CT scans enables automated quantification of skeletal muscle mass and radiodensity at standardized anatomical landmarks, such as the third lumbar vertebra. This facilitates rapid, reproducible risk stratification without the need for labor-intensive manual analysis.

Similarly, muscle US, a bedside modality increasingly used for serial muscle monitoring, is now being augmented with machine learning algorithms to improve interobserver reliability and enable real-time assessment of muscle thickness and echogenicity trends. These developments are particularly valuable in resource-limited or high-acuity environments where advanced imaging may not be feasible.

Beyond imaging, predictive analytics derived from electronic health record data are under investigation for their potential to identify patients at elevated risk of ICU-AW. Algorithms integrating variables such as illness severity scores, nutritional intake, inflammatory biomarkers, and medication profiles have shown promise in pilot studies to guide early intervention strategies – such as mobilization consults, tailored nutrition plans, or pharmacologic evaluation – at the point of care[64].

In parallel, novel bedside tools are emerging to facilitate non-invasive, continuous assessment of muscle status. BIA devices and wearable sensors are being evaluated for their capacity to estimate lean body mass and physical activity levels in real time, thereby offering dynamic insights into muscle trajectory during ICU stay[65,66].

ICU-acquired sarcopenia and myosteatosis are now recognized as clinically significant complications of critical illness, associated with increased mortality, prolonged mechanical ventilation, delayed rehabilitation, and long-term functional impairment. Their pathophysiology is multifactorial – spanning inflammation, endocrine dysregulation, immobility, nutritional deficits, and neural dysfunction – necessitating a multifaceted, interdisciplinary management approach.

Despite growing recognition, these conditions remain underdiagnosed and inconsistently managed in routine clinical practice. Early identification using available tools – such as CT-based muscle area, US measurements, or manual muscle testing – should become standard of care. Equally critical is the integration of targeted interventions: (1) Individualized nutrition; (2) Progressive mobilization protocols; and (3) Potential pharmacologic adjuncts.

Importantly, the consequences of ICU-acquired muscle loss extend well beyond hospital discharge. Survivorship programs should prioritize longitudinal muscle health through structured rehabilitation, body composition monitoring, and functional assessments during outpatient follow-up.

While emerging technologies and therapeutic modalities offer promising avenues for improving patient outcomes, several gaps persist. These include the absence of universally accepted diagnostic thresholds, limited multicenter data on intervention efficacy, and a need for standardized post-ICU care models. Future research must focus on validating risk prediction models, defining biomarker-driven treatment pathways, and integrating digital health tools into critical care workflows.

Ultimately, addressing ICU-acquired sarcopenia as a core ICU syndrome – akin to sepsis or ARDS – may redefine outcome priorities and catalyze a shift toward muscle-preserving, recovery-focused critical care. By prioritizing functional outcomes alongside survival, we may improve not only how patients leave the ICU – but how they live afterward.

| 1. | Akan B. Influence of sarcopenia focused on critically ill patients. Acute Crit Care. 2021;36:15-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Boutin RD, Kaptuch JM, Bateni CP, Chalfant JS, Yao L. Influence of IV Contrast Administration on CT Measures of Muscle and Bone Attenuation: Implications for Sarcopenia and Osteoporosis Evaluation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;207:1046-1054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | van Gassel RJJ, Baggerman MR, van de Poll MCG. Metabolic aspects of muscle wasting during critical illness. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2020;23:96-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fazzini B, Märkl T, Costas C, Blobner M, Schaller SJ, Prowle J, Puthucheary Z, Wackerhage H. The rate and assessment of muscle wasting during critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2023;27:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 75.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Puthucheary ZA, Rawal J, McPhail M, Connolly B, Ratnayake G, Chan P, Hopkinson NS, Phadke R, Dew T, Sidhu PS, Velloso C, Seymour J, Agley CC, Selby A, Limb M, Edwards LM, Smith K, Rowlerson A, Rennie MJ, Moxham J, Harridge SD, Hart N, Montgomery HE. Acute skeletal muscle wasting in critical illness. JAMA. 2013;310:1591-1600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1118] [Cited by in RCA: 1429] [Article Influence: 109.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 6. | Sabatino A, Cuppari L, Stenvinkel P, Lindholm B, Avesani CM. Sarcopenia in chronic kidney disease: what have we learned so far? J Nephrol. 2021;34:1347-1372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 55.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Klawitter F, Ehler J, Bajorat R, Patejdl R. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Intensive Care Unit-Acquired Weakness and Critical Illness Myopathy: A Narrative Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:5516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Owen AM, Patel SP, Smith JD, Balasuriya BK, Mori SF, Hawk GS, Stromberg AJ, Kuriyama N, Kaneki M, Rabchevsky AG, Butterfield TA, Esser KA, Peterson CA, Starr ME, Saito H. Chronic muscle weakness and mitochondrial dysfunction in the absence of sustained atrophy in a preclinical sepsis model. Elife. 2019;8:e49920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bolton CF, Gilbert JJ, Hahn AF, Sibbald WJ. Polyneuropathy in critically ill patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1984;47:1223-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 381] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ogawa S, Yakabe M, Akishita M. Age-related sarcopenia and its pathophysiological bases. Inflamm Regen. 2016;36:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Xie T, Lv T, Zhang T, Feng D, Zhu F, Xu Y, Zhang L, Gu L, Guo Z, Ding C, Gong J. Interleukin-6 promotes skeletal muscle catabolism by activating tryptophan-indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1-kynurenine pathway during intra-abdominal sepsis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2023;14:1046-1059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chauvot de Beauchene R, Souweine B, Bonnet B, Evrard B, Boirie Y, Cassagnes L, Dupuis C. Sarcopenia, myosteatosis and inflammation are independent prognostic factors of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia patients admitted to the ICU. Sci Rep. 2025;15:4373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Preiser JC, Ichai C, Orban JC, Groeneveld AB. Metabolic response to the stress of critical illness. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:945-954. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Kim YJ, Tamadon A, Park HT, Kim H, Ku SY. The role of sex steroid hormones in the pathophysiology and treatment of sarcopenia. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 2016;2:140-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | de Jong JCBC, Attema BJ, van der Hoek MD, Verschuren L, Caspers MPM, Kleemann R, van der Leij FR, van den Hoek AM, Nieuwenhuizen AG, Keijer J. Sex differences in skeletal muscle-aging trajectory: same processes, but with a different ranking. Geroscience. 2023;45:2367-2386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bahat G, Tufan A, Tufan F, Kilic C, Akpinar TS, Kose M, Erten N, Karan MA, Cruz-Jentoft AJ. Cut-off points to identify sarcopenia according to European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) definition. Clin Nutr. 2016;35:1557-1563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung TW, Chou MY, Iijima K, Jang HC, Kang L, Kim M, Kim S, Kojima T, Kuzuya M, Lee JSW, Lee SY, Lee WJ, Lee Y, Liang CK, Lim JY, Lim WS, Peng LN, Sugimoto K, Tanaka T, Won CW, Yamada M, Zhang T, Akishita M, Arai H. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update on Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:300-307.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2739] [Cited by in RCA: 4594] [Article Influence: 765.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bannan B, Zia Z, Ashour M. L3 skeletal muscle index (L3SMI) definition of sarcopenia: Defining the imaging biomarker standard in a Middle East population. Clin Radiol. 2022;77:e31. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kim HK, Kim KW, Kim EH, Lee MJ, Bae SJ, Ko Y, Park T, Shin Y, Kim YJ, Choe J. Age-related changes in muscle quality and development of diagnostic cutoff points for myosteatosis in lumbar skeletal muscles measured by CT scan. Clin Nutr. 2021;40:4022-4028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Garcia-Diez AI, Porta-Vilaro M, Isern-Kebschull J, Naude N, Guggenberger R, Brugnara L, Milinkovic A, Bartolome-Solanas A, Soler-Perromat JC, Del Amo M, Novials A, Tomas X. Myosteatosis: diagnostic significance and assessment by imaging approaches. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2024;14:7937-7957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | De Rosa S, Umbrello M, Pelosi P, Battaglini D. Update on Lean Body Mass Diagnostic Assessment in Critical Illness. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Looijaard WG, Dekker IM, Stapel SN, Girbes AR, Twisk JW, Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Weijs PJ. Skeletal muscle quality as assessed by CT-derived skeletal muscle density is associated with 6-month mortality in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2016;20:386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Grimm A, Teschner U, Porzelius C, Ludewig K, Zielske J, Witte OW, Brunkhorst FM, Axer H. Muscle ultrasound for early assessment of critical illness neuromyopathy in severe sepsis. Crit Care. 2013;17:R227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Skoczynski R, Hansen J, Adhikary SD, Lehman E, Bonavia AS. Point-of-Care Ultrasound as a Prognostic Tool in Critically Ill Patients: Insights Beyond Core Muscle Mass. medRxiv. 2025;2025.03.19.25324253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sim M, Dalla Via J, Scott D, Lim WH, Hodgson JM, Zhu K, Daly RM, Duque G, Prince RL, Lewis JR. Creatinine to Cystatin C Ratio, a Biomarker of Sarcopenia Measures and Falls Risk in Community-Dwelling Older Women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2022;77:1389-1397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tang T, Zhuo Y, Xie L, Wang H, Yang M. Sarcopenia index based on serum creatinine and cystatin C is associated with 3-year mortality in hospitalized older patients. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Buendgens L, Yagmur E, Bruensing J, Herbers U, Baeck C, Trautwein C, Koch A, Tacke F. Growth Differentiation Factor-15 Is a Predictor of Mortality in Critically Ill Patients with Sepsis. Dis Markers. 2017;2017:5271203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Grunow JJ, Reiher K, Carbon NM, Engelhardt LJ, Mai K, Koch S, Schefold JC, Z'Graggen W, Schaller SJ, Fielitz J, Spranger J, Weber-Carstens S, Wollersheim T. Muscular myostatin gene expression and plasma concentrations are decreased in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2022;26:237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Llano-Diez M, Gustafson AM, Olsson C, Goransson H, Larsson L. Muscle wasting and the temporal gene expression pattern in a novel rat intensive care unit model. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kobayashi M, Kasamatsu S, Shinozaki S, Yasuhara S, Kaneki M. Myostatin deficiency not only prevents muscle wasting but also improves survival in septic mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2021;320:E150-E159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Traoré M, Noviello C, Vergnol A, Gentil C, Halliez M, Saillard L, Gelin M, Forand A, Lemaitre M, Guesmia Z, Cadot B, Caldas de Almeida Araujo E, Marty B, Mougenot N, Messéant J, Strochlic L, Sadoine J, Slimani L, Jolly A, De la Grange P, Hogrel JY, Pietri-Rouxel F, Falcone S. GDF5 as a rejuvenating treatment for age-related neuromuscular failure. Brain. 2024;147:3834-3848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jiang T, Lin T, Shu X, Song Q, Dai M, Zhao Y, Huang L, Tu X, Yue J. Prevalence and prognostic value of preexisting sarcopenia in patients with mechanical ventilation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2022;26:140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yan Y, Xie Y, Du Z, Wang X, Liu L, Li M, Li X. [Correlation analysis between mechanical power normalized to dynamic lung compliance and weaning outcomes and prognosis in mechanically ventilated patients: a prospective, observational cohort study]. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2025;37:36-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Morgan A. Long-term outcomes from critical care. Surgery (Oxf). 2021;39:53-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Hermans G, Van Mechelen H, Clerckx B, Vanhullebusch T, Mesotten D, Wilmer A, Casaer MP, Meersseman P, Debaveye Y, Van Cromphaut S, Wouters PJ, Gosselink R, Van den Berghe G. Acute outcomes and 1-year mortality of intensive care unit-acquired weakness. A cohort study and propensity-matched analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:410-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 402] [Cited by in RCA: 378] [Article Influence: 31.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 36. | Herridge MS, Moss M, Hough CL, Hopkins RO, Rice TW, Bienvenu OJ, Azoulay E. Recovery and outcomes after the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in patients and their family caregivers. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:725-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (13)] |

| 37. | Casaer MP, Stragier H, Hermans G, Hendrickx A, Wouters PJ, Dubois J, Guiza F, Van den Berghe G, Gunst J. Impact of withholding early parenteral nutrition on 2-year mortality and functional outcome in critically ill adults. Intensive Care Med. 2024;50:1593-1602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | van Ruijven IM, Abma J, Brunsveld-Reinders AH, Stapel SN, van Etten-Jamaludin F, Boirie Y, Barazzoni R, Weijs PJM. High protein provision of more than 1.2 g/kg improves muscle mass preservation and mortality in ICU patients: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin Nutr. 2023;42:2395-2403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Li Z, Tong X, Ma Y, Bao T, Yue J. Prevalence of depression in patients with sarcopenia and correlation between the two diseases: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13:128-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 37.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Yogesh M, Dave A, Kagathara J, Gandhi R, Lakkad D. Prevalence of Sarcopenia and Its Association with Mental Health Status in Elderly Patients: A Comparative Cross-sectional Study. J Midlife Health. 2025;16:51-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Casaer MP, Mesotten D, Hermans G, Wouters PJ, Schetz M, Meyfroidt G, Van Cromphaut S, Ingels C, Meersseman P, Muller J, Vlasselaers D, Debaveye Y, Desmet L, Dubois J, Van Assche A, Vanderheyden S, Wilmer A, Van den Berghe G. Early versus late parenteral nutrition in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:506-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1145] [Cited by in RCA: 1092] [Article Influence: 72.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Drummond MJ, Rasmussen BB. Leucine-enriched nutrients and the regulation of mammalian target of rapamycin signalling and human skeletal muscle protein synthesis. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11:222-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Oktaviana J, Zanker J, Vogrin S, Duque G. The Effect of β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate (HMB) on Sarcopenia and Functional Frailty in Older Persons: A Systematic Review. J Nutr Health Aging. 2019;23:145-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Wittholz K, Bongetti AJ, Fetterplace K, Caldow MK, Karahalios A, De Souza DP, Elahee Doomun SN, Rooyackers O, Koopman R, Lynch GS, Ali Abdelhamid Y, Deane AM. Plasma beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate availability after enteral administration during critical illness after trauma: An exploratory study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2024;48:421-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, deBoisblanc BP, Steingrub J, Rock P; NIH NHLBI Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network of Investigators. Enteral omega-3 fatty acid, gamma-linolenic acid, and antioxidant supplementation in acute lung injury. JAMA. 2011;306:1574-1581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 430] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 24.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Pradelli L, Klek S, Mayer K, Omar Alsaleh AJ, Rosenthal MD, Heller AR, Muscaritoli M. Omega-3 fatty acid-containing parenteral nutrition in ICU patients: systematic review with meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis. Crit Care. 2020;24:634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Gravelyn TR, Brophy N, Siegert C, Peters-Golden M. Hypophosphatemia-associated respiratory muscle weakness in a general inpatient population. Am J Med. 1988;84:870-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Laddhad DS, Hingane V, Patil TR, Laddhad DD, Laddhad AD, Laddhad SD. An assessment of serum magnesium levels in critically ill patients: A prospective observational study. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2023;13:111-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, Nigos C, Pawlik AJ, Esbrook CL, Spears L, Miller M, Franczyk M, Deprizio D, Schmidt GA, Bowman A, Barr R, McCallister KE, Hall JB, Kress JP. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1874-1882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2077] [Cited by in RCA: 2205] [Article Influence: 129.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Bonorino KC, Cani KC. Early mobilization in the time of COVID-19. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2020;32:484-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Nakanishi N, Yoshihiro S, Kawamura Y, Aikawa G, Shida H, Shimizu M, Fujinami Y, Matsuoka A, Watanabe S, Taito S, Inoue S. Effect of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation in Patients With Critical Illness: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Crit Care Med. 2023;51:1386-1396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Nonoyama T, Shigemi H, Kubota M, Matsumine A, Shigemi K, Ishizuka T. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation in the intensive care unit prevents muscle atrophy in critically ill older patients: A retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e29451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Li L, Li F, Zhang X, Song Y, Li S, Yao H. The effect of electrical stimulation in critical patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Neurol. 2024;15:1403594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | El Naggar T, Obaya H, Ismail A, Azzam R, El Naggar A. Inspiratory Muscle Training Prevents Diaphragmatic Atrophy in Mechanically Ventilated COVID-19 Patients. Int J Med Arts. 2021;3:1761-1771. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 55. | Hart DW, Wolf SE, Ramzy PI, Chinkes DL, Beauford RB, Ferrando AA, Wolfe RR, Herndon DN. Anabolic effects of oxandrolone after severe burn. Ann Surg. 2001;233:556-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Palmieri C, Linden H, Birrell SN, Wheelwright S, Lim E, Schwartzberg LS, Dwyer AR, Hickey TE, Rugo HS, Cobb P, O'Shaughnessy JA, Johnston S, Brufsky A, Tilley WD, Overmoyer B. Activity and safety of enobosarm, a novel, oral, selective androgen receptor modulator, in androgen receptor-positive, oestrogen receptor-positive, and HER2-negative advanced breast cancer (Study G200802): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, multinational, parallel design, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2024;25:317-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Gokhale Y, Mehta R, Kulkarni U, Karnik N, Gokhale S, Sundar U, Chavan S, Kor A, Thakur S, Trivedi T, Kumar N, Baveja S, Wadal A, Kolte S, Deolankar A, Pednekar S, Kalekar L, Padiyar R, Londhe C, Darole P, Pol S, Gokhe SB, Padwal N, Pandey D, Yadav D, Joshi A, Badgujar H, Trivedi M, Shah P, Bhavsar P. Tocilizumab improves survival in severe COVID-19 pneumonia with persistent hypoxia: a retrospective cohort study with follow-up from Mumbai, India. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Karampitsakos T, Malakounidou E, Papaioannou O, Dimakopoulou V, Zarkadi E, Katsaras M, Tsiri P, Tsirikos G, Georgiopoulou V, Oikonomou I, Davoulos C, Velissaris D, Sampsonas F, Marangos M, Akinosoglou K, Tzouvelekis A. Tocilizumab improves 28-day survival in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19: an open label, prospective study. Respir Res. 2021;22:317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Al-Baadani A, Eltayeb N, Alsufyani E, Albahrani S, Basheri S, Albayat H, Batubara E, Ballool S, Al Assiri A, Faqihi F, Musa AB, Robert AA, Alsherbeeni N, Elzein F. Efficacy of tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19: Survival and clinical outcomes. J Infect Public Health. 2021;14:1021-1027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Hostrup M, Reitelseder S, Jessen S, Kalsen A, Nyberg M, Egelund J, Kreiberg M, Kristensen CM, Thomassen M, Pilegaard H, Backer V, Jacobson GA, Holm L, Bangsbo J. Beta(2) -adrenoceptor agonist salbutamol increases protein turnover rates and alters signalling in skeletal muscle after resistance exercise in young men. J Physiol. 2018;596:4121-4139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Souza JT, Minicucci MF, Ferreira NC, Polegato BF, Okoshi MP, Modolo GP, Leal-Pereira FW, Phillips BE, Atherton PJ, Smith K, Wilkinson DJ, Gordon AL, Tanni SE, Costa VE, Fernandes MF, Bazan SG, Zornoff LM, Paiva SR, Bazan R, Azevedo PS. Influence of CReatine Supplementation on mUScle Mass and Strength After Stroke (ICaRUS Stroke Trial): A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2024;16:4148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Fuld JP, Kilduff LP, Neder JA, Pitsiladis Y, Lean ME, Ward SA, Cotton MM. Creatine supplementation during pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2005;60:531-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Lee SJ, Bhasin S, Klickstein L, Krishnan V, Rooks D. Challenges and Future Prospects of Targeting Myostatin/Activin A Signaling to Treat Diseases of Muscle Loss and Metabolic Dysfunction. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2023;78:32-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Fuentes-Aspe R, Gutierrez-Arias R, González-Seguel F, Marzuca-Nassr GN, Torres-Castro R, Najum-Flores J, Seron P. Which factors are associated with acquired weakness in the ICU? An overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Intensive Care. 2024;12:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Myatchin I, Abraham P, Malbrain MLNG. Bio-electrical impedance analysis in critically ill patients: are we ready for prime time? J Clin Monit Comput. 2020;34:401-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Deana C, Gunst J, De Rosa S, Umbrello M, Danielis M, Biasucci DG, Piani T, Cotoia A, Molfino A, Vetrugno L; Nutriti Study Group. Bioimpedance-assessed muscle wasting and its relation to nutritional intake during the first week of ICU: a pre-planned secondary analysis of Nutriti Study. Ann Intensive Care. 2024;14:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/