Published online Nov 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i33.110641

Revised: June 26, 2025

Accepted: October 22, 2025

Published online: November 26, 2025

Processing time: 163 Days and 6.1 Hours

This study investigates the impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) on the risk of interstitial lung disease (ILD) and its subtypes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). RA is often complicated by ILD. T2DM has systemic proinflammatory effects, but its impact on RA-related ILD is unclear. This research aims to elucidate the interplay between these conditions to inform clinical management and patient care strategies.

To determine if RA patients with T2DM have a higher occurrence of ILD compar

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the 2019-2020 National Inpa

Among 199380 RA inpatients, ILD was more common in those with T2DM (2.25%) vs without (1.11%). After matching (n = 121046), ILD remained higher in RA + T2DM [odds ratio (OR) = 2.02, 95%CI: 1.84-2.22, P < 0.001], with an absolute risk increase of about 1.14%. T2DM was associated with higher odds of ILD subtypes including usual interstitial pneumonia (OR = 3.20) and non-specific interstitial pneumonia (OR = 3.50). Other subtypes showed elevated ORs; eosinophilic pneumonia showed an inverse association (OR = 0.23). PAH and pneumothorax were also more common in RA + T2DM (OR = 1.40 and 1.85, respectively). Acute respiratory distress syn

T2DM increases ILD risk in RA and is linked to higher rates of pulmonary hypertension and pneumothorax, suggesting a role in exacerbating RA-related lung complications.

Core Tip: In this large inpatient study, we found that rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients with type 2 diabetes have about twice the odds of developing interstitial lung disease compared to those without diabetes. This novel association remained significant after adjusting for numerous confounders. Diabetic RA patients also showed more pulmonary hypertension and pneumothorax. These results highlight the “diabetic lung” as a potential new consideration in RA care. Clinicians should be aware that co-morbid diabetes might heighten pulmonary risks in RA, although prospective studies are needed to confirm if controlling diabetes can improve lung outcomes.

- Citation: Sutton J, Khattar G, Saliba F, Mourad O, Aoun L, Jdaidani J, Qandil H, Kaspar C, Abu-Baker S, Almardini S, Haddadin F, Bou Sanayeh E, Slobodnick A. Impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus on interstitial lung disease risk in rheumatoid arthritis. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(33): 110641

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i33/110641.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i33.110641

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common rheumatic disease, affecting around 0.5%-1% of the adult population worldwide[1]. It is an autoimmune and inflammatory disease that causes swelling, pain, and eventual damage to the joints. With the increasing incidence of RA, physicians are now seeing increasing numbers of extra-articular complications.

Pulmonary complications, including RA-related interstitial lung disease (ILD), contribute significantly to mortality and morbidity, with a lifetime risk of around 10%[2]. RA's most common ILD pattern is the usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern on high-resolution computed tomography (CT)[3]. However, non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) also occurs and may overlap with the UIP pattern, rendering the differentiation between both entities hard, especially in the setting of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)[4]. Subclinical or asymptomatic ILD is being detected more with increased use of CT scanning. Up to 30% of early RA patients may show signs of ILD[5]. Known risk factors for ILD include male gender, older age, smoking, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, high rheumatoid factor levels, and genetic factors[6,7]. However, endocrine and metabolic disorders haven’t been investigated as a risk factor for ILD in the RA population.

Diabetes mellitus (DM), a prevalent metabolic condition, has been increasingly recognized for its systemic effects beyond glucose metabolism[8]. Research indicates that the risk of type 2 DM (T2DM) is increased in RA by approximately 50%-70% after accounting for risk factors such as obesity[9]. Proinflammatory cytokines secreted in RA, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6, induce insulin resistance by inhibiting insulin signaling pathways and impaired glucose metabolism[10-12]. Additionally, glucocorticoids, which are frequently prescribed for RA management, can worsen insulin sensitivity and increase the risk of diabetes, particularly with long-term use[13].

The relationship between DM and pulmonary outcomes is complex and varies across studies. A study of IPF patients found higher rates of DM, with 17.8% of IPF patients having concurrent DM. IPF patients with DM exhibited more severe radiological and clinical manifestations[14]. In contrast, a separate large prospective study of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) found a negative correlation between DM and lung disease. In this study, DM was associated with a 24% lower risk of developing ARDS compared to nondiabetics, even after adjusting for potential confounding factors such as medications[15]. Considering this conflicting evidence regarding the general population, our study, the first of its kind, aims to clarify the impact of DM on pulmonary outcomes by focusing on the unique RA cohort. This approach is taken due to RA's distinct clinical profile, marked by chronic inflammation and the common use of glucocorticoids. These factors potentially affect both DM and lung health in ways not seen in the general population.

The primary objective of this study was to compare the prevalence of ILD in RA patients with vs. without T2DM. Secondary objectives included evaluating differences in ILD subtypes (UIP, NSIP, etc.) and other pulmonary complications (ARDS), pneumothorax, pleural effusion, and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) between the groups. By leveraging the United States National Inpatient Sample (NIS)-a large hospitalization database-and applying robust matching methods, we aimed to isolate the association of T2DM with ILD in RA. We also discuss potential mechanisms (e.g., chronic hyperglycemia-induced lung changes) and highlight that our findings are associative and hypothesis-generating, not proof of causation.

We performed a retrospective cohort study to explore the association of T2DM with ILD and its subclasses, as well as secondary pulmonary outcomes such as ARDS, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, and PAH in patients with RA. Hospitalization outcomes, including length of stay (LOS), were also examined. The study utilized the NIS database for 2019 and 2020, which is recognized as the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient healthcare database in the United States. This study was exempt from institutional review board approval because the NIS contains de-identified patient data.

We identified adult inpatients (≥ 18 years) with RA by querying records for International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes M05.00-M06.9 (RA categories) as either the principal or a secondary diagnosis during the admission. Patients were included if RA was present in any diagnosis field, not only primary, to capture all RA patients hospitalized for any reason. We excluded patients with type 1 diabetes (E10.x codes) to focus on T2DM and avoid conflating different diabetes types. We also excluded those with other connective tissue diseases, history of certain ILD-causing exposures (e.g., radiation therapy), or conditions strongly associated with ILD (e.g., sarcoidosis, listed in Supplementary Table as exclusion codes). These exclusions were intended to reduce confounding from other ILD etiologies (Supplementary Table 1).

The study population was then stratified into two cohorts: RA with T2DM (RA+DM) and RA without T2DM (RA-DM). T2DM status was determined by presence of ICD-10 codes E11.0-E11.9 in any diagnosis field. We did not have data on duration of diabetes or glycemic control in NIS. Baseline characteristics and comorbidities were compared between RA+DM and RA-DM groups before matching.

To control for confounding, we considered a broad range of covariates known or suspected to influence ILD or to differ by DM status. These included age, sex, race, median household income by ZIP code, insurance type, hospital characteristics, and the following comorbidities: Hypertension, smoking history, obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, heart failure, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease (CKD), GERD (gastroesophageal reflux), alcohol abuse, and others (full list in Table 1). We also included steroid use (ICD-10 code Z79.52 for long-term glucocorticoid therapy) and immunosuppressant use (Z79.5-) as binary covariates, acknowledging that we lacked dosage/duration details. These variables were chosen a priori based on clinical relevance to RA or ILD risk.

| Baseline characteristics | RA+DM (n = 60523) | RA-DM (n = 138848) | P value |

| Age | 69.06 (11.56) | 68.25 (14.41) | < 0.001 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 42031 (69.45) | 102277 (73.66) | < 0.001 |

| Race | |||

| White | 40840 (67.48) | 108904 (78.43) | < 0.001 |

| Black | 10059 (16.62) | 14765 (10.63) | < 0.001 |

| Hispanic | 6368 (10.52) | 9481 (6.83) | < 0.001 |

| Asian | 1375 (2.27) | 2718 (1.96) | < 0.001 |

| Native | 1196 (1.98) | 1999 (1.44) | < 0.001 |

| Other | 685 (1.13) | 990 (0.71) | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Gastro-esophageal reflux disease | 21363 (35.3) | 46663 (33.61) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 7849 (12.97) | 16699 (12.03) | < 0.001 |

| Asthma | 6271 (10.36) | 12672 (9.13) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking | 5780 (9.55) | 15831 (11.4) | < 0.001 |

| Heart failure | 29061 (48.02) | 38053 (27.4) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 20373 (33.66) | 23650 (17.03) | < 0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 9868 (16.3) | 19183 (13.81) | < 0.001 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 1065 (1.76) | 1996 (1.44) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 53568 (88.51) | 99210 (71.45) | < 0.001 |

| Obesity | 19604 (32.39) | 25059 (18.05) | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol use | 1132 (1.87) | 4936 (3.55) | < 0.001 |

| Steroids use | 5767 (9.53) | 15274 (11.0) | < 0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 21901 (36.19) | 31360 (22.58) | < 0.001 |

Initial assessment of confounders revealed a significant imbalance, prompting the use of propensity score matching to create comparable cohorts (Table 1). Logistic regression was employed to calculate propensity scores, followed by 1:1 matching using the nearest neighbors' ball tree algorithm without replacement. Following matching, multivariate logistic regression was conducted to evaluate the association of T2DM with primary and secondary outcomes while adjusting for residual confounding factors. Statistical significance was defined as a P value < 0.05.

An independent t-test was used to compare the characteristics of the two groups for continuous parametric variables. The Mann-Whitney U test was employed for continuous nonparametric variables. To assess the differences in categorical variables, the χ2 and Fisher exact tests were utilized. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Importantly, any missing data on key variables (< 5% for race, < 1% for others) led to those records being dropped (complete-case approach), which still left > 99% of cases.

From the 13798325 patients sampled in the NIS 2019 and 2020 cohorts, we identified 214453 patients with RA. After applying exclusion criteria, our final pre-match cohort included 199380 patients.

The RA+DM group had a slightly higher mean age (69.06 years with a standard deviation of 11.56) than the RA-DM group (68.25 years with a standard deviation of 14.41). However, this difference was not statistically significant. Females were more prevalent in both groups, with significantly more females in the RA-DM group compared to the RA+DM group. Both samples consisted of predominantly white subjects, with significantly more white subjects in the RA-DM group than in the RA+DM group (Table 1). The RA+DM group had a significantly higher prevalence of most com

Using propensity score matching to account for baseline confounders, our analysis resulted in a matched sample of 121046 patients. The success of the matching process was confirmed by the standard mean differences for all confounders being less than 0.01. Additionally, the P-values associated with these confounders were non-significant, further validating the efficacy of the matching (Table 2).

| Baseline characteristics | RA+DM (n = 60523) | RA-DM (n = 60523) | P value |

| Age | 69.06 (11.56) | 69.1 (11.60) | 0.986 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 42031 (69.45) | 41985 (69.37) | 0.774 |

| Race | |||

| White | 40840 (67.48) | 40910 (67.59) | 0.667 |

| Black | 10059 (16.62) | 9997 (16.51) | 0.632 |

| Hispanic | 6368 (10.52) | 6391 (10.55) | 0.830 |

| Asian | 1375 (2.27) | 1384 (2.28) | 0.862 |

| Native | 1196 (1.98) | 1149 (1.89) | 0.327 |

| Other | 685 (1.13) | 692 (1.14) | 0.850 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Gastro-esophageal reflux disease | 21363 (35.30) | 21363 (35.30) | 1.000 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 7849 (12.97) | 7833 (12.94) | 0.898 |

| Asthma | 6271 (10.36) | 6268 (10.36) | 0.985 |

| Smoking | 5780 (9.55) | 5761 (9.52) | 0.860 |

| Heart failure | 29061 (48.02) | 29049 (48.00) | 0.950 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 20373 (33.66) | 20348 (33.62) | 0.884 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 9868 (16.30) | 9863 (16.30) | 0.975 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 1065 (1.76) | 1059 (1.75) | 0.913 |

| Hypertension | 53568 (88.51) | 53525 (88.44) | 0.705 |

| Obesity | 19604 (32.39) | 19580 (32.35) | 0.888 |

| Alcohol use | 1132 (1.87) | 1129 (1.87) | 0.966 |

| Steroids use | 5767 (9.53) | 5760 (9.52) | 0.953 |

| Coronary artery disease | 21901 (36.19) | 21890 (36.17) | 0.952 |

The least common ILD variants, including desquamative interstitial pneumonia (n = 3), lymphoid interstitial pne

In the matched sample, the prevalence of ILD in the RA+DM group was significantly higher, with 1360 patients (2.25%) compared to 672 patients (1.11%) in the RA-DM group, yielding an odds ratio (OR) of 2.023 (95%CI: 1.843-2.219, P < 0.001). Subgroup analysis revealed that pulmonary fibrosis, including UIP, had an OR of 3.200 (95%CI: 2.800-3.700, P < 0.001), indicating a strong association with T2DM. Similarly, NSIP was significantly associated with T2DM, with an OR of 3.500 (95%CI: 2.900-4.100, P < 0.001). These ORs are high, but it should be noted that baseline prevalence of UIP/NSIP in RA-DM was low (about 0.3% or less).

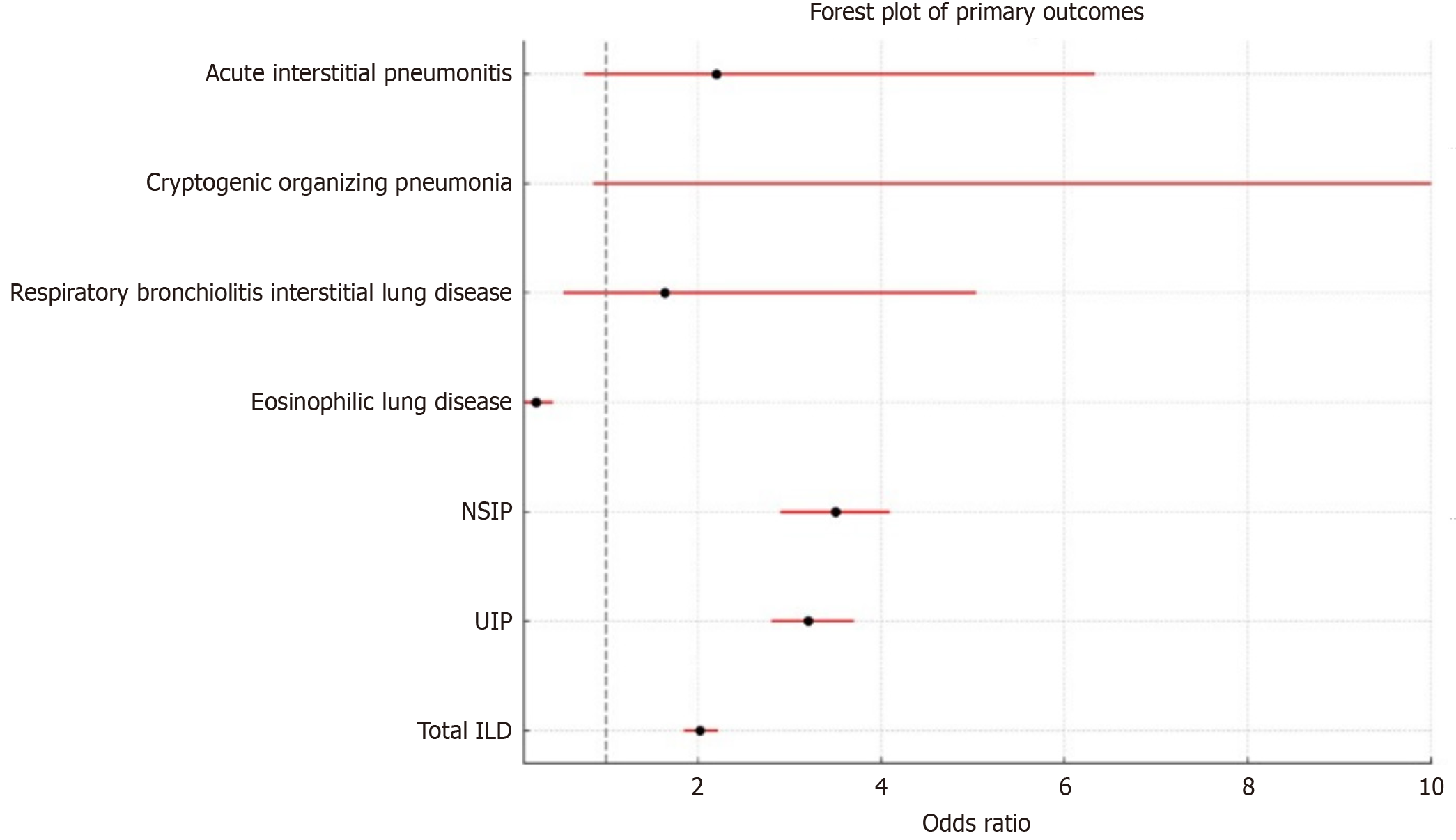

Other ILD subtypes, such as respiratory bronchiolitis ILD and Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia (COP), also displayed significant associations with T2DM, with ORs of 1.636 (95%CI: 0.531-5.036, P = 0.002) and 96.040 (95%CI: 0.860-1072, P = 0.06), respectively (Figure 1). However, the association for COP did not reach statistical significance due to the small sample size. Additionally, acute interstitial pneumonitis (AIP) had an OR of 2.201 (95%CI: 0.764-6.335, P < 0.001). Conversely, eosinophilic lung disease showed an inverse association with DM, with an OR of 0.232 (95%CI: 0.112-0.415, P < 0.001) (Tables 3 and 4).

| Outcomes | RA+DM (n = 50423) | RA-DM (n = 50423) | P value |

| Interstitial lung diseases | 1360 (2.25) | 672 (1.11) | < 0.001 |

| Usual interstitial pneumonia/pulmonary fibrosis | 840 (1.67) | 227 (0.45) | < 0.001 |

| Non-specific interstitial pneumonia | 494 (0.98) | 133 (0.26) | < 0.001 |

| Eosinophilic lung disease | 18 (0.04) | 78 (0.15) | < 0.001 |

| Respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease | 8 (0.02) | 5 (0.01) | < 0.001 |

| Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia | 17 (0.03) | 1 (< 0.01) | 0.057 |

| Acute interstitial pneumonitis | 11 (0.02) | 5 (0.01) | < 0.001 |

| Outcomes | Odds ratio | P value | 95%CI |

| Interstitial lung diseases | 2.203 | < 0.001 | 1.843-2.219 |

| Usual interstitial pneumonia/pulmonary fibrosis | 3.200 | < 0.001 | 2.800-3.700 |

| Non-specific interstitial pneumonia | 3.500 | < 0.001 | 2.900-4.100 |

| Eosinophilic lung disease | 0.232 | < 0.001 | 0.112-0.415 |

| Respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease | 1.636 | 0.002 | 0.531-5.036 |

| Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia | 96.040 | 0.06 | 0.860-1072 |

| Acute interstitial pneumonitis | 2.201 | < 0.001 | 0.764-6.335 |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 1.116 | 0.260 | 0.921-1.353 |

| Pneumothorax | 1.848 | < 0.001 | 1.465-2.332 |

| Pleural effusion | 1.028 | 0.49 | 0.959-1.101 |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension | 1.397 | < 0.001 | 1.331-1.467 |

As for the secondary outcomes, Pneumothorax was significantly more prevalent in the RA+DM group (203 patients, 0.40%) compared to the RA-DM group (110 patients, 0.22%), with an OR of 1.848 (95%CI: 1.465-2.332, P < 0.001). PAH also had a higher prevalence in the RA+DM group (4141 patients, 8.21%) compared to the RA-DM group (2964 patients, 5.88%), with an OR of 1.397 (95%CI: 1.331-1.467, P < 0.001). In contrast, ARDS and pleural effusion did not show sig

| Outcomes | RA+DM (n = 50423) | RA-DM (n = 50423) | P value |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 221 (0.44) | 198 (0.39) | 0.260 |

| Pneumothorax | 203 (0.40) | 110 (0.22) | < 0.001 |

| Pleural effusion | 1694 (3.36) | 1648 (3.27) | 0.49 |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension | 4141 (8.21) | 2964 (5.88) | < 0.001 |

This study investigated the relationship between T2DM and pulmonary outcomes-mainly ILD and its subtypes-in pat

Moreover, the results indicated an association of DM with increased incidences of PAH, pneumothorax, and AIP in RA patients. The large sample size provided by the NIS database lends credibility to our findings and suggests they may be applicable to the broader RA patient population. As one of the first studies to examine this relationship with such a comprehensive data set, it contributes to a more nuanced understanding of the interplay between RA, DM, and ILD. Furthermore, the matching process allowed us to compare the RA+DM and RA-DM groups on an equal footing by accounting for more than 15 confounding factors within the baseline characteristics and comorbidities.

The demographic characteristics observed in this study, including the predominance of white female subjects in the RA population, are consistent with findings from prior studies on RA. These trends have been reported in various epidemiological studies, reinforcing the notion that RA predominantly affects individuals of certain demographic backgrounds[16]. The prevalence of ILD and its subtypes in the RA population in our study correlated with the range of 4% to 8%, documented in the literature[3,4].

Moreover, we found that the RA+DM group had a higher prevalence of comorbidities before matching, such as HTN, CKD, asthma, and COPD, which is consistent with the broader understanding of the increased burden of comorbidities in patients with DM, which aligns with previous research and highlight the complexity of these patients[17]. The higher incidence of comorbidities could potentially influence the incidence, management, and severity of ILD and other pulmonary outcomes such as pulmonary hypertension[18]. However, the impact of these comorbidities was potentially nullified after matching.

Our study results suggest that individuals who had both RA and DM are twice as likely to develop any ILD, as well as three times more likely to develop pulmonary fibrosis, whether UIP or NSIP patterns. Numerous studies have indicated a link between type 2 diabetes and the development of restrictive lung diseases, mostly IPF[19-23]. Studies also showed that the prevalence of diabetes is higher in patients with pulmonary fibrosis compared to the general population or those with other lung diseases[24,25]. Interestingly, The SAKU study, involving 1028 diabetic individuals aged 40-69, found that those with poor glycemic control (HbA1c ≥ 8.0%) had a 2.42 times higher likelihood of restrictive lung impairment compared to those with good control (HbA1c < 6.9%), a statistically significant finding (P = 0.002)[26]. However, the subtype of restrictive lung disease the patients developed was not mentioned.

Multiple intertwined mechanisms, such as microangiopathy, chronic inflammation, and non-enzymatic glycation in diabetes, can be postulated to worsen RA’s already harmful effects on the lungs, potentially explaining our results[17]. NSIP often manifests with diffuse, uniform inflammation/fibrosis. The systemic inflammation and oxidative stress caused by T2DM (due to hyperglycemia) may exacerbate lung inflammation, leading to the diffuse alveolar damage seen in NSIP[4]. Additionally, diabetes-related microangiopathy-small vessel damage akin to that in diabetic nephropathy and retinopathy-could occur in lung microvasculature. This could thicken alveolar walls and pulmonary capillaries, impair gas exchange, and promote the uniform fibrotic response typical of NSIP. There is some support for this: Studies of diabetic lung tissue show capillary basement membrane thickening and reduced capillary counts which parallel changes in NSIP pathology[27,28]. Moreover, reduced pulmonary capillary blood flow and consequent hypoxia can trigger pro-fibrotic pathways.

UIP, a histopathological pattern seen in IPF and most commonly in RA, is characterized by heterogeneous lung fibrosis with areas of normal lung interspersed with fibrotic regions and honeycombing. Several diabetes-related mechanisms align more closely with the pathophysiology of UIP/IPF. The autonomic neuropathy and impaired respiratory muscle function in diabetes reduce lung volumes and can accelerate restrictive lung changes, contributing to the patchy fibrotic changes observed in UIP. Hyperglycemia-induced stiffening of the lung parenchyma and pleura through the glycation of proteins such as collagen and elastin can lead to the structural lung changes characteristic of UIP[28].

This stiffening can also explain the significant increase in the incidence of pneumothorax, as the altered lung mechanics make the lung parenchyma more susceptible to rupture. Additionally, hyperglycemia-driven oxidative stress and inflammation further exacerbate fibroproliferative responses, promoting the focal fibrotic lesions in UIP. Studies have shown that diabetic patients, particularly those with poor glycemic control, have a higher prevalence of IPF, suggesting a link between metabolic dysregulation and the development of UIP[21-23]. Since this previous finding wasn’t explored previously in the literature, it is recommended that a correlation between the conditions be established and the un

In our analysis of secondary outcomes, we revealed an increasing incidence of PAH in the RA+DM group. PAH is associated with connective tissue disorders, influenced by factors such as autoimmunity, vascular changes, and chronic inflammation. In the context of RA, PAH may be induced through mechanisms including chronic pulmonary embolism, vasculopathy, and pulmonary fibrosis[29]. Additionally, DM has been identified not only as a factor that increases the incidence and severity of PAH in patients with chronic lung disease but also as an independent factor contributing to the development of PAH[30]. Understanding these associations provides valuable insights into the complex interplay between RA, DM, and PAH.

It must be stressed, however, that these mechanistic explanations are hypotheses. We did not directly investigate the biological pathways in this administrative data study. The mechanisms by which T2DM could exacerbate ILD are speculative and drawn from prior literature on “diabetic lung” changes[28]. Our findings do not prove causation; it is possible that RA patients who develop ILD have some underlying predisposition that also makes them more likely to develop T2DM (for instance, a shared genetic or environmental factor, or RA severity leading to steroid use causing DM). Also, chronic RA inflammation could contribute to developing T2DM (through cytokine-induced insulin resistance), highlighting a bidirectional relationship. Untangling cause and effect requires longitudinal studies.

There are several limitations to acknowledge. First, this was an observational study using hospital discharge data, and causality cannot be established. We report associations: T2DM is associated with higher ILD odds in RA, but we cannot confirm T2DM causes ILD. Unmeasured factors (e.g., RA duration, specific medications, or unrecorded pulmonary risk factors) could confound results. We did not have data on RA disease activity (like DAS28 scores) or seropositivity, which are risk factors for ILD. We also lacked granular data on RA treatments such as methotrexate or biologics. This is important because methotrexate, for example, can cause pneumonitis or affect ILD risk, and its use might differ between diabetics and non-diabetics. Without these variables, residual confounding is possible. We did include a proxy for immunosuppressant use (Z79.52, long-term steroid, and Z79.5, immunosuppressant therapy), but these are crude indicators. Similarly, we did not have metrics of glycemic control - a patient with well-controlled DM might have dif

Our study’s majority-female cohort reflects RA demographics but had fewer males than some RA-ILD case series, possibly because women with RA are more likely to be hospitalized for other comorbidities including DM. Thus, caution is needed in extrapolating to, say, male RA patients or non-white populations. We noted a significant proportion of Black patients in RA+DM (16.6%) vs RA-DM (10.6%) pre-match, consistent with higher DM rates among Black Americans. We matched on race, but some residual differences could still subtly influence results (e.g., if Black patients have different ILD risk). However, given ILD is often more common in male smokers (and Black RA patients in the United States may have lower smoking rates than whites), it’s hard to guess direction of any bias there.

The study period coincided partly with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (2020). We did not specifically exclude or adjust for COVID-related ILD or ARDS. It is possible some ILD diagnoses in 2020 were influenced by post-COVID pulmonary fibrosis. We suspect this impact is minimal on our results for a few reasons: (1) We required an RA diagnosis in the admission, which is less common in pure COVID pneumonia admissions; and (2) Our ILD codes were specific, and likely clinicians would distinguish acute COVID pneumonitis from chronic ILD. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that the pandemic could have altered hospital utilization and coding. For example, some RA patients with respiratory issues might have been coded differently or avoided hospitals in early 2020. We mention this as a limitation and an area to interpret carefully.

Despite these limitations, our study has notable strengths. The use of a very large nationwide database increases statistical power and diversity of the sample. Our propensity score matching rigorously controlled for many confounders, making the RA+DM vs RA-DM groups as comparable as possible given observed data. The primary findings remained robust in sensitivity analyses. We also examined a range of outcomes to build a consistent story (DM associated not just with ILD but also with related complications like PH and pneumothorax, which triangulates with the ILD finding). To our knowledge, this is the first report quantifying the link between T2DM and ILD in RA patients. It opens the door for further research into metabolic interventions in RA-ILD.

If our findings are confirmed, they suggest that RA patients with T2DM might warrant closer monitoring for ILD. For instance, clinicians managing RA patients who also have diabetes might consider a lower threshold for pulmonary evaluation (e.g., pulmonary function tests or HRCT scans) when patients present with respiratory symptoms, even mild ones. This is speculative, but given ILD’s impact on RA outcomes (RA-ILD significantly shortens survival), an awareness that T2DM could be a risk factor might encourage more vigilant screening in that subgroup. Additionally, our results raise the question of whether better diabetes management could improve lung outcomes in RA. Optimal glycemic control might hypothetically slow fibrotic processes (since high glucose can drive AGEs and oxidative stress).

There is some evidence from non-RA studies that diabetes medications (like metformin or pioglitazone) have anti-fibrotic effects in lung models[31,32]. Future prospective studies or clinical trials could explore if treating insulin resistance (with drugs or lifestyle) in RA patients reduces ILD incidence or progression. We caution that such re

Additionally, a more proactive approach to pulmonary screening for this patient subgroup is needed. Implementing more frequent and detailed assessments, such as high-resolution CT scans, could be crucial in early identification and potential mitigation of disease progression. Additionally, more studies are needed to determine whether a more proactive approach to screening for both ILD and PAH would benefit this subgroup.

In conclusion, the autoimmune and inflammatory nature of RA, along with the frequent use of steroids, elevate the risk of developing T2DM. The literature currently lacks a comprehensive understanding of how DM in RA patients influences the occurrence of ILD, a common complication of RA. Our retrospective cohort study, following confounder matching, revealed a twofold increase in the risk of ILD in RA patients with T2DM. Additionally, it demonstrated an elevated risk of pulmonary fibrosis, PAH, and pneumothorax. Further research is needed to unravel the mechanisms through which DM amplifies the risk of these pulmonary complications in RA patients, raising questions about whether stringent blood sugar control or specific medical interventions can prevent early pulmonary involvement.

| 1. | Finckh A, Gilbert B, Hodkinson B, Bae SC, Thomas R, Deane KD, Alpizar-Rodriguez D, Lauper K. Global epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022;18:591-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Alivernini S, Firestein GS, McInnes IB. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Immunity. 2022;55:2255-2270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 65.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bongartz T, Nannini C, Medina-Velasquez YF, Achenbach SJ, Crowson CS, Ryu JH, Vassallo R, Gabriel SE, Matteson EL. Incidence and mortality of interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1583-1591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in RCA: 621] [Article Influence: 38.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lee HK, Kim DS, Yoo B, Seo JB, Rho JY, Colby TV, Kitaichi M. Histopathologic pattern and clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Chest. 2005;127:2019-2027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 307] [Cited by in RCA: 307] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yoshinouchi T, Ohtsuki Y, Fujita J, Yamadori I, Bandoh S, Ishida T, Ueda R. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia pattern as pulmonary involvement of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2005;26:121-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gochuico BR, Avila NA, Chow CK, Novero LJ, Wu HP, Ren P, MacDonald SD, Travis WD, Stylianou MP, Rosas IO. Progressive preclinical interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:159-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 329] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhang Y, Li H, Wu N, Dong X, Zheng Y. Retrospective study of the clinical characteristics and risk factors of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:817-823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | O'Dwyer DN, Armstrong ME, Cooke G, Dodd JD, Veale DJ, Donnelly SC. Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) associated interstitial lung disease (ILD). Eur J Intern Med. 2013;24:597-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim YJ, Park JW, Kyung SY, Lee SP, Chung MP, Kim YH, Lee JH, Kim YC, Ryu JS, Lee HL, Park CS, Uh ST, Lee YC, Kim KH, Chun YJ, Park YB, Kim DS, Jegal Y, Lee JH, Park MS, Jeong SH. Clinical characteristics of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients with diabetes mellitus: the national survey in Korea from 2003 to 2007. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:756-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Solomon DH, Love TJ, Canning C, Schneeweiss S. Risk of diabetes among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:2114-2117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science. 1993;259:87-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5334] [Cited by in RCA: 5517] [Article Influence: 167.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 12. | Gonzalez-Gay MA, De Matias JM, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Garcia-Porrua C, Sanchez-Andrade A, Martin J, Llorca J. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade improves insulin resistance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24:83-86. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Solomon DH, Massarotti E, Garg R, Liu J, Canning C, Schneeweiss S. Association between disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and diabetes risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. JAMA. 2011;305:2525-2531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dessein PH, Joffe BI, Stanwix AE, Christian BF, Veller M. Glucocorticoids and insulin sensitivity in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:867-874. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Yu S, Christiani DC, Thompson BT, Bajwa EK, Gong MN. Role of diabetes in the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:2720-2732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gabriel SE. The epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2001;27:269-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 445] [Cited by in RCA: 473] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yip K, Navarro-Millán I. Racial, ethnic, and healthcare disparities in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2021;33:117-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Iglay K, Hannachi H, Joseph Howie P, Xu J, Li X, Engel SS, Moore LM, Rajpathak S. Prevalence and co-prevalence of comorbidities among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:1243-1252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Goldman MD. Lung dysfunction in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1915-1918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pitocco D, Fuso L, Conte EG, Zaccardi F, Condoluci C, Scavone G, Incalzi RA, Ghirlanda G. The diabetic lung--a new target organ? Rev Diabet Stud. 2012;9:23-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Enomoto T, Usuki J, Azuma A, Nakagawa T, Kudoh S. Diabetes mellitus may increase risk for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2003;123:2007-2011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bai L, Zhang L, Pan T, Wang W, Wang D, Turner C, Zhou X, He H. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Respir Res. 2021;22:175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Abernethy AD, Stackhouse K, Hart S, Devendra G, Bashore TM, Dweik R, Krasuski RA. Impact of diabetes in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2015;5:117-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Klein OL, Krishnan JA, Glick S, Smith LJ. Systematic review of the association between lung function and Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2010;27:977-987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ehrlich SF, Quesenberry CP Jr, Van Den Eeden SK, Shan J, Ferrara A. Patients diagnosed with diabetes are at increased risk for asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary fibrosis, and pneumonia but not lung cancer. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:55-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sonoda N, Morimoto A, Tatsumi Y, Asayama K, Ohkubo T, Izawa S, Ohno Y. The association between glycemic control and lung function impairment in individuals with diabetes: the Saku study. Diabetol Int. 2019;10:213-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rajasurya V, Gunasekaran K, Surani S. Interstitial lung disease and diabetes. World J Diabetes. 2020;11:351-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Xin WX, Fang L, Fang QL, Zheng XW, Ding HY, Huang P. Effect of hypoglycemic agents on survival outcomes of lung cancer patients with diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e0035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Li CY, Erickson SR, Wu CH. Metformin use and asthma outcomes among patients with concurrent asthma and diabetes. Respirology. 2016;21:1210-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hitchings AW, Lai D, Jones PW, Baker EH; Metformin in COPD Trial Team. Metformin in severe exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2016;71:587-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | El-Naa MM, El-Refaei MF, Nasif WA, Abduljawad SH, El-Brairy AI, El-Readi MZ. In-vivo antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of rosiglitazone, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-γ) agonists in animal model of bronchial asthma. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2015;67:1421-1430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Viby NE, Isidor MS, Buggeskov KB, Poulsen SS, Hansen JB, Kissow H. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) reduces mortality and improves lung function in a model of experimental obstructive lung disease in female mice. Endocrinology. 2013;154:4503-4511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Han Y, Cho YE, Ayon R, Guo R, Youssef KD, Pan M, Dai A, Yuan JX, Makino A. SGLT inhibitors attenuate NO-dependent vascular relaxation in the pulmonary artery but not in the coronary artery. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;309:L1027-L1036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/