Published online Nov 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i33.109866

Revised: June 2, 2025

Accepted: October 28, 2025

Published online: November 26, 2025

Processing time: 181 Days and 15.5 Hours

Mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) is a rare autoimmune disorder characterized by overlapping features of systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sc

We report a 35-year-old Pakistani female presenting with oral ulcers, body rash, worsening dyspnea, and a history of joint pains initially treated as rheumatoid arthritis. She was on antituberculous therapy (ATT) for presumed pulmonary TB. Laboratory findings revealed anemia, leukopenia, raised erythrocyte sedimen

This case highlights the diagnostic complexity when autoimmune diseases coexist with TB, particularly in TB-endemic regions. Early recognition and integrated management of both conditions are crucial to improving outcomes. Clinicians should maintain a broad differential diagnosis and perform comprehensive immunological workup in patients with overlapping symptoms.

Core Tip: Mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) can mimic infectious diseases like tuberculosis (TB), complicating diagnosis especially in TB-endemic regions. This case highlights the importance of comprehensive immunological testing to differentiate MCTD from TB. Early recognition and tailored treatment improve patient outcomes significantly.

- Citation: Sial F, Basit A, Ghafoor N, Sial W, Basil AM. Mixed connective tissue disease and tuberculosis coexistence as a diagnostic dilemma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(33): 109866

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i33/109866.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i33.109866

Mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) is a rare and complex systemic autoimmune disorder marked by elevated levels of anti-U1 ribonucleoprotein (anti-RNP) autoantibodies. It is characterized by overlapping symptoms of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma and polymyositis[1]. It has been reported that patients with MCTD occasionally show an association with tuberculosis (TB)[2-4]. Tuberculosis is a serious, infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, mainly affecting lungs. Patients of pulmonary tuberculosis present with persistent cough, fever, weight loss and fatigue[5]. We present a rare and complex case of overlap syndrome featuring SLE and tuber

A 35-year-old Pakistani female presented to the emergency department of a tertiary care hospital with complaints of oral ulcers, body rash, and worsening shortness of breath.

Now, 3 weeks back she developed shortness of breath with exertion which was gradual in onset and progressive in nature. It was associated with dry cough. She was diagnosed with reactivation (secondary) tuberculosis by her GP and had been taking rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for this for 10 days. 10 days back she developed painless ulcers on lips, angles of mouth and inner surface of oral cavity, which started bleeding three days back. 3 days ago, she also developed purpuric rash involving both the extremities and trunk which was non-pruritic.

Before the presentation, the patient had been diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis due to history of bilateral swelling, redness and pain in small joints of hands and wrists and large joints i.e. elbows and knees for which she had been taking methotrexate 10 mg daily along with folic acid supplementation for 8 months.

Insignificant.

General physical examination revealed pallor, non-tender oral ulcers with bleeding surface, pinched nose, thinning of lips, and partial skin tightening of distal and middle phalanges. There were reduced breath sounds on right infrascapular region with stony dull percussion note.

Lab investigations showed decreased white blood cells, haematocrit, platelet count, reticulocytes, liver function tests were mildly deranged. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was raised too, C-reactive protein was not evaluated at this moment. She was found to be hepatitis C virus positive and TB positive. Urine C/E revealed leukocyte esterase 1+, blood 3+, many red blood cells, 6-8 pus cells (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5).

| Test | Reference value, % | Result, % |

| WBC | 4-11 × 109/L | 2.3 × 109/L |

| RBC | 3.5-5.5 × 1012/L | 2.31 × 1012/L |

| HGB | 12-15 g/dL | 5.1 g/dL |

| Hct | 36-46 | 17.8 |

| MCH | 76-96 pg | 22.3 pg |

| MCHC | 31.5-34.5 g/L | 29.9 g/L |

| Platelets | 150-450 × 109/L | 35 × 109/L |

| MPV | 40-80 | 9.6 |

| Neutrophils | 20-40 | 42.7 |

| Lymphocytes | 2-8 | 18.7 |

| Eosinophils | 1-5 | 0.2 |

| MCV | 27-31 fL | 77.4 fL |

| Reticulocyte count | 12.2-16.1 | 1 |

| ESR | 0-20 mm/hours | 79 mm/hours |

| Test | Reference | Result |

| AST | 10-40 IU/L | 131 IU/L |

| ALT | 10-40 IU/L | 51 IU/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 44-147 IU/L | 427 IU/L |

| Total bilirubin | 0.1-1.20 mg/dL | 0.36 mg/dL |

| Renal function panel RFTs | ||

| Serum urea | 10-50 mg/dL | 18 mg/dL |

| Serum creatinine | 0.7-1.20 mg/dL | 0.89 mg/dL |

| Electrolytes | ||

| Sodium | 135-145 mEq/L | 137 mEq/L |

| Potassium | 3.5-5.2 mEq/L | 3.6 mEq/L |

| Chloride | 96-106 mEq/L | 116 mEq/L |

| Albumin | ||

| Albumin | 3.5-5.5 g/dL | 2 g/dL |

| Physical examination | ||

| Test | Reference | Result |

| Colour | Normal/pale yellow | Pale yellow |

| Turbidity | Clear | - |

| Chemical examination | ||

| pH | 6.0 | |

| Specific gravity | 1.003-1.030 | 1.010 |

| Leukocytes esterase | - | + |

| Nitrite | Negative | - |

| Protein | Negative | - |

| Ketone | Negative | - |

| Bilirubin | Negative | - |

| Glucose | Nil | - |

| Blood | Nil | +++ |

| Urobilinogen | Nil | - |

| Microscopic examination | ||

| Pus cell | Negative | 6-8 |

| Crystals | Negative | - |

| Casts | Negative | - |

| Epithelial cells | Negative | - |

| RBC | Nil | Many |

| Bacteria | Nil | - |

| Yeast | Nil | - |

| Test | Result |

| pH | 7.407 |

| pO2 | 70 |

| pCO2 | 23 |

| K+ | 3.8 |

| HCO3- | 14.5 |

| SpO2 | 94.4% |

| RA factor | Negative | U/mL | |

| ANA | Positive | 1:5120 | Speckled pattern |

| Anti-nucleosome | Positive | 84 | SLE |

| Anti-dsDNA | Positive | 86 | |

| Anti-histones | Positive | 21 | |

| Anti-Sm | Positive | 90 | |

| Anti-Sm/RNP | Positive | 93 | MCTD |

| Anti-SSA/Ro 60kD | Positive | 92 | Sjogren syndrome |

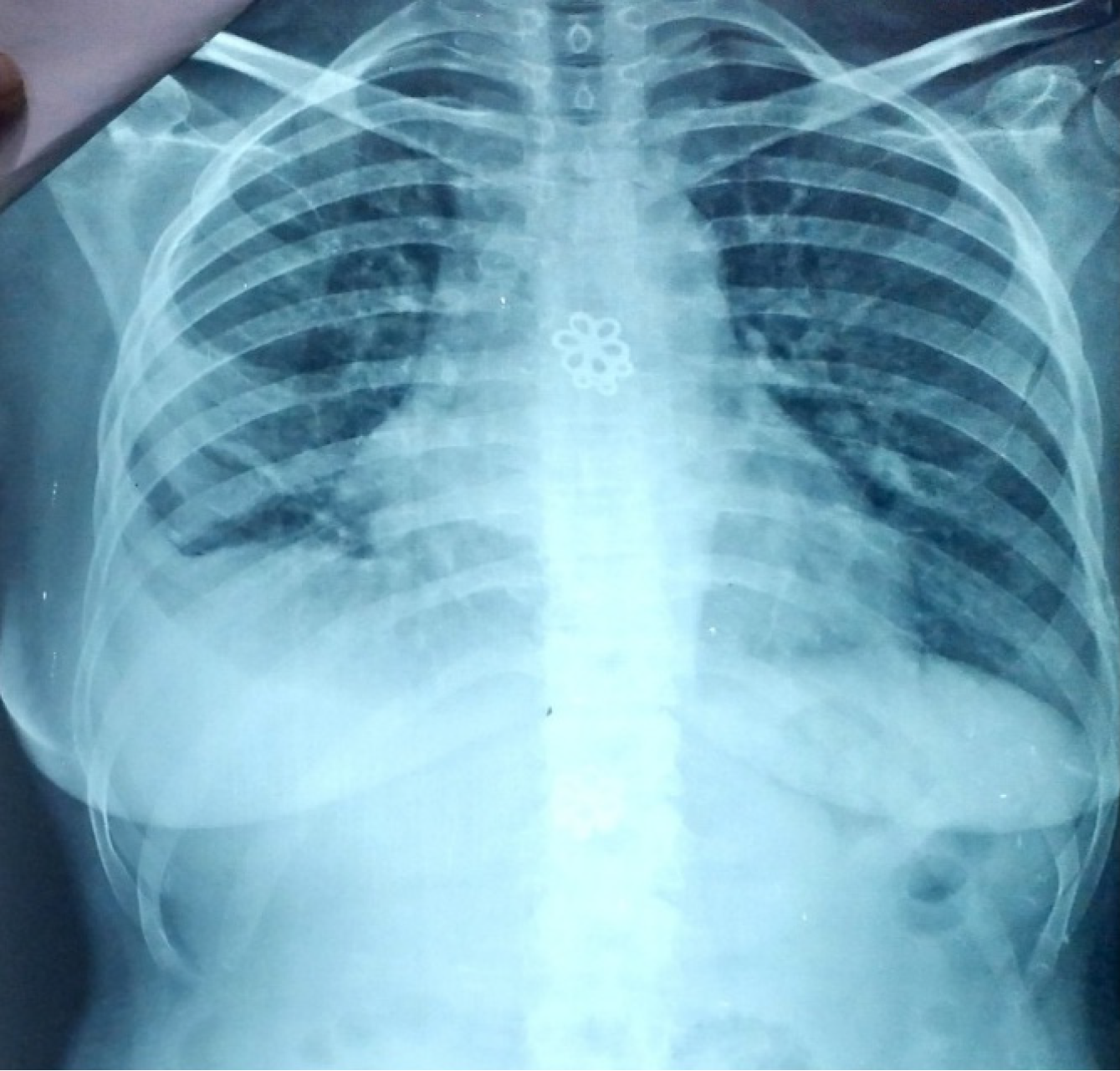

Chest X-ray showed right sided pleural effusion and right lower zone homogenous opacity (Figure 1). Ultrasound chest showed 150 mL of fluid on right side. Her ABG’s revealed respiratory alkalosis with metabolic compensation.

Based on all these findings she was diagnosed with mixed connective tissue disease (Systemic lupus erythematous, Sjogren, systemic sclerosis) with coexistence of TB.

She was admitted in ward and her treatment was started. The patient was thoroughly informed about her condition. Education regarding the treatment and its side effects was provided to the patient. She was encouraged to follow the recommended treatment plan to manage the symptoms effectively. She was given injection methylprednisolone 1 g IV once daily (OD) for 3 days, tab potassium chloride, oral vitamin D and calcium supplements, inf dextrose, sodium chloride 1 L IV OD, nebulization with ipratropium bromide and beclomethasone, tab folic acid 5 mg OD, miconazole oral gel, Tab betamethasone in water gargles, inj. calcium folinate 12.5 mg QID (4 times a day), Injection meropenem 500 mg IV TDS (three times a day), Tab prednisolone 40 mg daily along with continuation of a combination of rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol and pyrazinamide.

Patient stayed in ward for 12 days, during this time her platelet count and haemoglobin levels improved. Her ESR levels and C-reactive protein decreased. Oral ulcers, dyspnoea and haematuria settled. Patient was discharged after 12 days on Tab Hydroxychloroquine, prednisolone and Anti-Tuberculous regimen with follow-up on outpatient department basis. At the time of discharge, she was again encouraged to follow her treatment plan, and educated about the lifestyle modifications that should be made in order to manage her symptoms effectively. Initially the patient was followed up monthly then after 6 months. She was compliant and adhered to her medication and had good tolerability for it. She had no flare-ups till the last follow-up.

MCTD is a complex autoimmune condition with overlapping features of systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, and polymyositis, which often leads to diagnostic dilemmas, particularly in patients with comorbidities such as pulmonary TB. This overlap can complicate both the clinical presentation and the diagnostic process, as seen in our patient who presented with chronic respiratory symptoms. Pulmonary involvement in MCTD commonly manifests as interstitial lung disease, which shares clinical and radiological features with TB, including dyspnoea, chronic cough, and lung infiltrates[6,7]. The potential for these features to be mistaken for TB, especially in regions where TB is endemic, underscores the diagnostic challenge[8].

Pakistan ranks among the top five countries globally with the highest burden of TB, including multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB). A population-based study in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa reported that TB prevalence increases significantly with age, and Pakistan is the 4th highest globally in MDR-TB cases, indicating a growing public health concern[8]. Additionally, a study among livestock farmers in Lahore revealed a high prevalence of zoonotic tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex), especially among abattoir workers and animal handlers, emphasizing occupational risk and the need for One Health interventions[8,9].

The interaction between MCTD and TB extends beyond clinical similarities, as TB can exacerbate underlying autoimmune symptoms and complicate treatment protocols. For instance, immunosuppressive therapies used in MCTD, such as corticosteroids and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), can suppress the immune response, increasing susceptibility to TB reactivation. This was evident in our case, where the patient had a previous misdiagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis and was treated with methotrexate, a DMARD known to increase TB risk[10,11]. The patient’s worsening respiratory symptoms initially led to a presumptive TB diagnosis, yet further investigation revealed a strong immunological profile indicative of MCTD, with specific antibodies such as anti-Sm/RNP, which is a hallmark of this disease[7,12].

The misdiagnosis of MCTD as TB or other infectious diseases is not uncommon in the literature, as autoimmune manifestations in MCTD patients can resemble infections, particularly TB. For example, it is reported that MCTD patients presenting with lung symptoms are frequently misdiagnosed with respiratory infections, as clinical overlap and similar radiological findings create challenges in differential diagnosis[13]. Additionally, in a study by Pratap et al[14], approximately 20% of MCTD patients with pulmonary involvement were initially treated for respiratory infections before MCTD was identified, suggesting that routine TB treatment may delay appropriate immunosuppressive therapy and worsen prognosis.

This case underscores the critical importance of comprehensive immunological workup when standard TB treatment fails to resolve symptoms. Specific autoantibody profiles, including anti-Sm/RNP, play a crucial role in confirming MCTD in cases where clinical presentation alone may be misleading[6,12]. Further, serological markers are valuable in distinguishing MCTD from other autoimmune conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, which can present with similar initial symptoms like joint pain and swelling. The misdiagnosis of MCTD as rheumatoid arthritis or systemic sclerosis occurs frequently, further complicating the course of disease in the absence of targeted treatment[15].

Treatment strategies in cases of suspected MCTD should be carefully balanced, particularly when TB is part of the differential. Current guidelines for MCTD management emphasize corticosteroids and hydroxychloroquine, both of which led to significant improvement in our patient’s symptoms once the correct diagnosis was made[11,16]. Studies support that corticosteroids reduce systemic inflammation effectively, while hydroxychloroquine manages skin and joint manifestations, as seen in our case[9,11]. However, clinicians must remain cautious, as immunosuppressive therapies can increase TB susceptibility, making it essential to rule out or concurrently treat TB in endemic regions[14].

Our case demonstrates the importance of a broad differential diagnosis in patients with overlapping autoimmune and infectious disease features. Recognizing the potential for misdiagnosis between MCTD and TB, especially in endemic areas, is essential. This case adds to the literature supporting comprehensive serological testing and a nuanced approach to treatment, considering the risks associated with immunosuppression in TB-endemic regions.

| 1. | Reiseter S, Gunnarsson R, Corander J, Haydon J, Lund MB, Aaløkken TM, Taraldsrud E, Hetlevik SO, Molberg Ø. Disease evolution in mixed connective tissue disease: results from a long-term nationwide prospective cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kusaka K, Nakano K, Iwata S, Kubo S, Nishida T, Tanaka Y. Two patients with mixed connective tissue disease complicated by pulmonary arterial hypertension showing contrasting responses to pulmonary vasodilators. Mod Rheumatol Case Rep. 2020;4:253-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Khot RS, Patil A, Rathod BD, Patidar M, Joshi PP. Uncovering the Unusual: A Case of Mixed Connective Tissue Disease With Rare Presentation, Atypical Complications, and Therapeutic Dilemmas. Cureus. 2023;15:e36298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fujita M, Arakawa K, Mizuno S, Wakabayashi M, Totani Y, Demura Y, Ameshima S, Miyamori I, Ishizaki T, Sawai T. [A case of cutaneous tuberculosis under steroid & immunosuppressant therapy for dermatomyositis]. Kekkaku. 2002;77:465-470. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sehrish S, Liu XT, Lou WB, Zhang SY, Ata EB, Yang GG, Wang Q, Zeng FL, Leng X, Shi K, Azeem RM, Gong QL, Song YH, Du R. Prevalence of tuberculosis in bovines in Pakistan during 2000-2024: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Vet Sci. 2025;12:1525399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sharp GC, Irvin WS, Tan EM, Gould RG, Holman HR. Mixed connective tissue disease--an apparently distinct rheumatic disease syndrome associated with a specific antibody to an extractable nuclear antigen (ENA). Am J Med. 1972;52:148-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1268] [Cited by in RCA: 1157] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bennett RM, O'Connell DJ. Mixed connective tisssue disease: a clinicopathologic study of 20 cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1980;10:25-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Haq Z, Afaq S, Ibrahim M, Zala, Asim M. Prevalence of communicable, non-communicable diseases, disabilities and related risk factors in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Pakistan: Findings from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Integrated Population and Health Survey (2016-17). PLoS One. 2025;20:e0308209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ramos-Casals M, Roberto-Perez-Alvarez, Diaz-Lagares C, Cuadrado MJ, Khamashta MA; BIOGEAS Study Group. Autoimmune diseases induced by biological agents: a double-edged sword? Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:188-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nimelstein SH, Brody S, McShane D, Holman HR. Mixed connective tissue disease: a subsequent evaluation of the original 25 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1980;59:239-248. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Aringer M, Steiner G, Smolen JS. Does mixed connective tissue disease exist? Yes. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2005;31:411-420, v. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hoffman RW, Greidinger EL. Mixed connective tissue disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000;12:386-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gunnarsson R, Molberg O, Gilboe IM, Gran JT; PAHNOR1 Study Group. The prevalence and incidence of mixed connective tissue disease: a national multicentre survey of Norwegian patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1047-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pratap U, Ravindrachari M, RamyaPriya A, Toi PC, Manju R. Tuberculosis heralding connective tissue disorder. Trop Doct. 2021;51:261-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tardif ML, Mahone M. Mixed connective tissue disease in pregnancy: A case series and systematic literature review. Obstet Med. 2019;12:31-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Alarcón-Segovia D, Cardiel MH. Comparison between 3 diagnostic criteria for mixed connective tissue disease. Study of 593 patients. J Rheumatol. 1989;16:328-334. [PubMed] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/