Published online Nov 16, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i32.111796

Revised: August 14, 2025

Accepted: September 30, 2025

Published online: November 16, 2025

Processing time: 126 Days and 4.5 Hours

Groove pancreatitis (GP) is a rare focal chronic pancreatitis of the pancreatico

A 68-year-old man presented to our institution with severe gastric outlet obstru

In this case of GP, pancreatoduodenectomy safely treated severe gastric outlet obstruction when a cancer diagnosis could not be excluded.

Core Tip: Groove pancreatitis is a rare form of chronic pancreatitis, but cases continue to be reported. Total gastric outlet obstruction, as in our case, is extremely uncommon. The anatomical complexity of the groove area makes accurate diagnosis challenging, especially when a mass involves the pancreas, duodenum, or biliary tract. Treatment options range from conservative care to surgery, and accurate differentiation from malignancy is critical. However, discordant findings across imaging, laboratory findings, and biopsy results often hinder decision-making. In select cases, aggressive surgical intervention may provide definitive diagnosis, shorten treatment duration, and reduce recurrence, as demonstrated in our patient.

- Citation: Kim N, Lee H, Park D. Challenging diagnosis of groove pancreatitis with severe gastric outlet obstruction: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(32): 111796

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i32/111796.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i32.111796

Groove pancreatitis (GP) is a rare type of focal chronic pancreatitis that affects the “pancreaticoduodenal groove”, the area between the head of the pancreas, duodenum, and common bile duct[1]. It most commonly affects men in their 40-year-old and 50-year-old and is usually associated with chronic alcohol abuse[2,3]. The accurate prevalence of GP is still difficult to determine, but previous studies have shown that it is present in 3%-24% of patients undergoing surgery for chronic pancreatitis[4]. Despite advances in imaging, a definitive diagnosis remains difficult, and failure to clearly differentiate between GP and periampullary malignancies often leads to the performance of a pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD)[5]. Herein, we report the case of a patient with GP accompanied by the rare symptom of severe gastric outlet obstruction with life threatening conditions. We report this case with the purpose of addressing the scarcity of reported GP cases and showing the efficacy of PD in these patients when the symptoms are severe and a cancer diagnosis cannot be ruled out.

A 68-year-old male patient with chronic heavy alcoholic and current smoking habits presented to the Department of Emergency in our institution with general weakness and a poor mental status.

The patient had a history of recurrent vomiting for 3 days prior to presentation at the hospital and complained of abdominal distension and pain.

The patient was being treated for diabetes and insomnia. Additionally, the patient had been taking medication for schizophrenia for 30 years, however, disease was well-controlled and no communication problems were apparent.

The patient’s older sister denied any family history of malignant hepatobiliary pancreatic tumors.

A clinical examination revealed abdominal distension and epigastric tenderness. The patient had a body temperature of 37.8 °C, blood pressure of 109/89 mmHg, heart rate of 80 beats/minute, and respiratory rate of 20 breaths/minute. The patient’s drowsy mental status persisted; however, neurological examination and brain imaging were otherwise unremarkable.

Laboratory tests showed a severe serum electrolyte imbalance, with a sodium level of 119 mmol/L, potassium level of 2.3 mmol/L, chloride level of < 60 mmol/L, and creatinine level of 4.45 mg/dL, suggesting acute kidney injury.

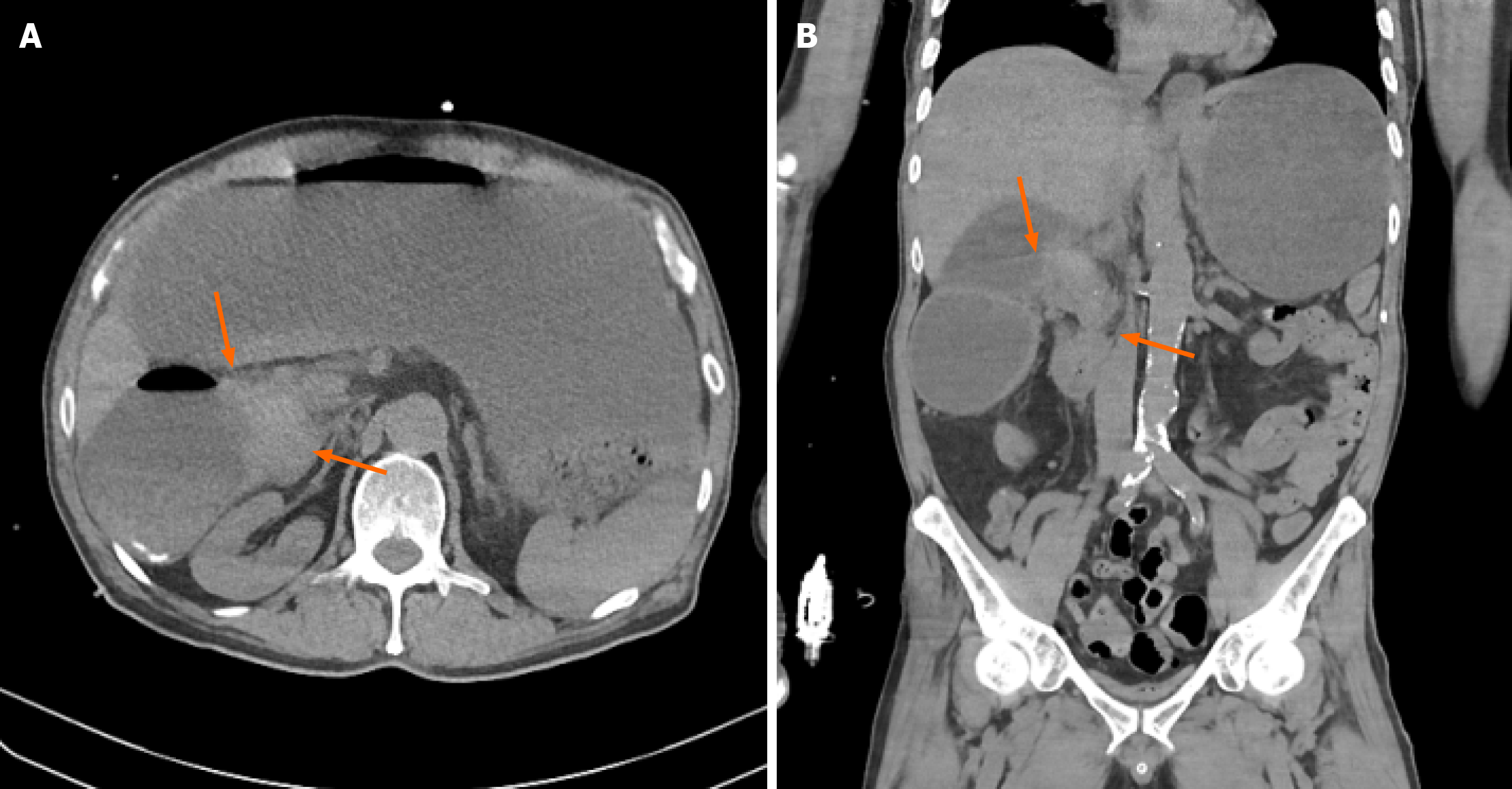

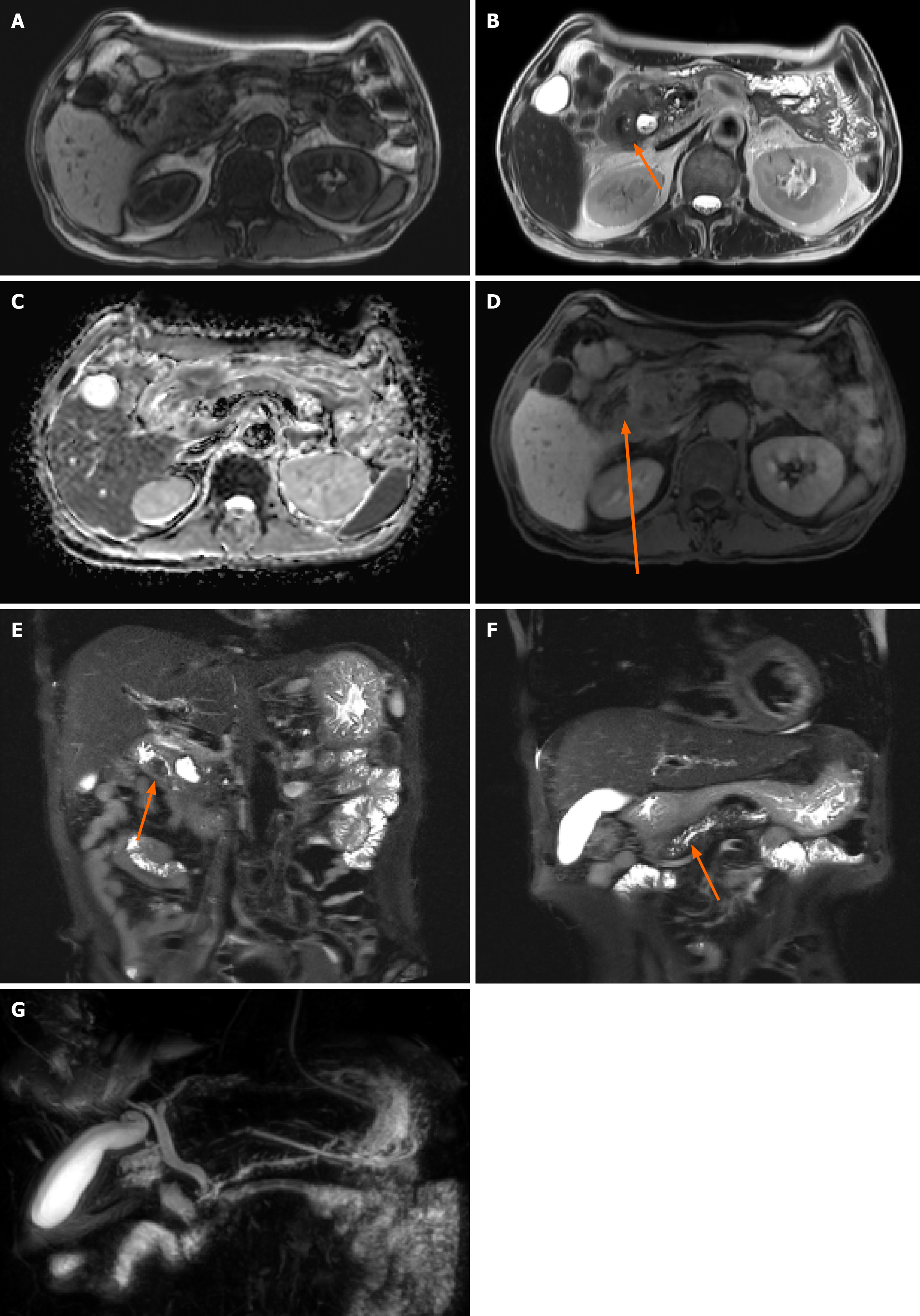

Non-contrast computed tomography (CT) imaging (Figure 1) initially showed severe gastric distension and a mass that was suspicious for malignancy in the second portion. However, without contrast enhancement, the information that can be obtained from CT imaging is limited; therefore, additional pancreatic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed. This MRI revealed prominent enhancement in the ampulla of Vater (AoV) which was suggestive of cancer (Figure 2).

In the emergency room, the patient underwent drainage of 1500 mL of gastric content after the insertion of a Levin tube. Correction of the electrolyte imbalance was then performed in the intensive care unit. Subsequently, despite the oxygen supply, the dyspnea worsened and cardiac arrest occurred with repeated premature ventricular complex showing on the echocardiogram. The cardiac rhythm recovered 4 minutes after intubation and cardiac compression. At the time of intubation, the airway was filled with gastric contents, suggesting respiratory arrest due to aspiration.

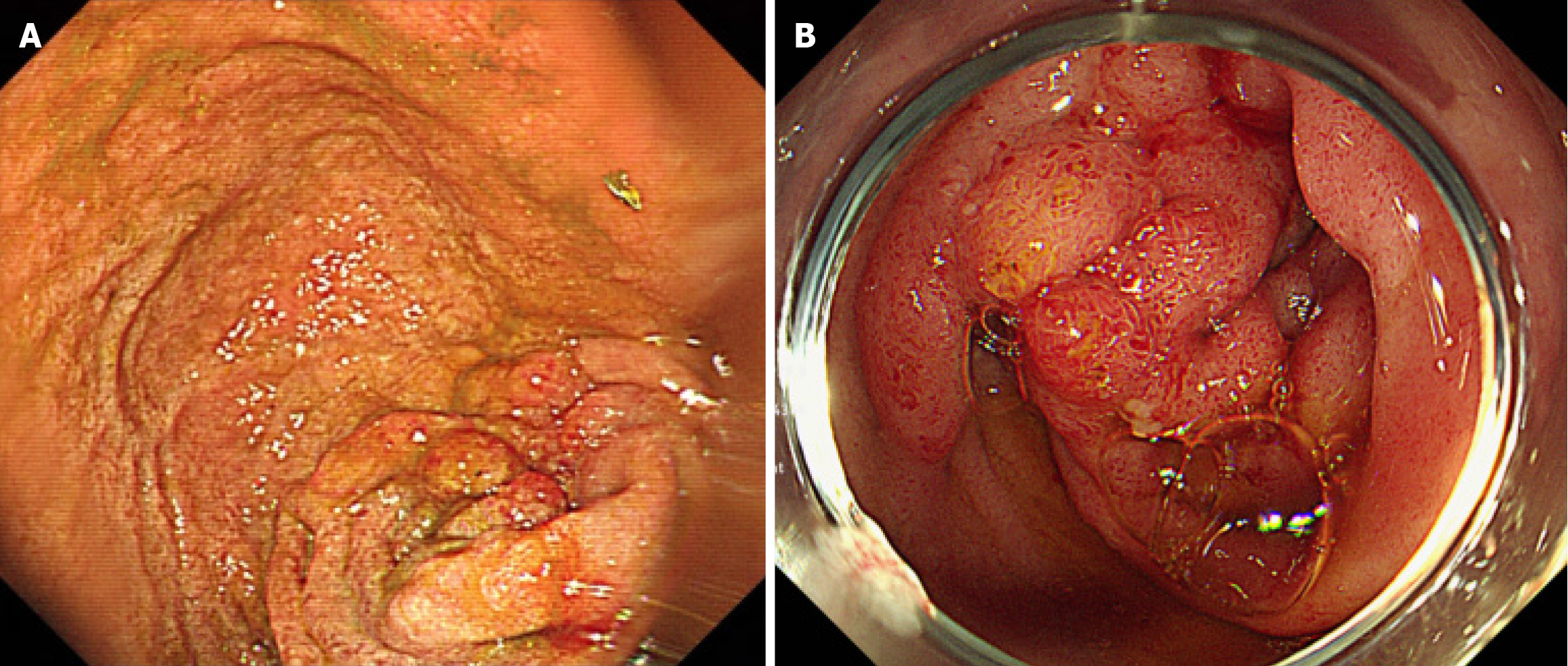

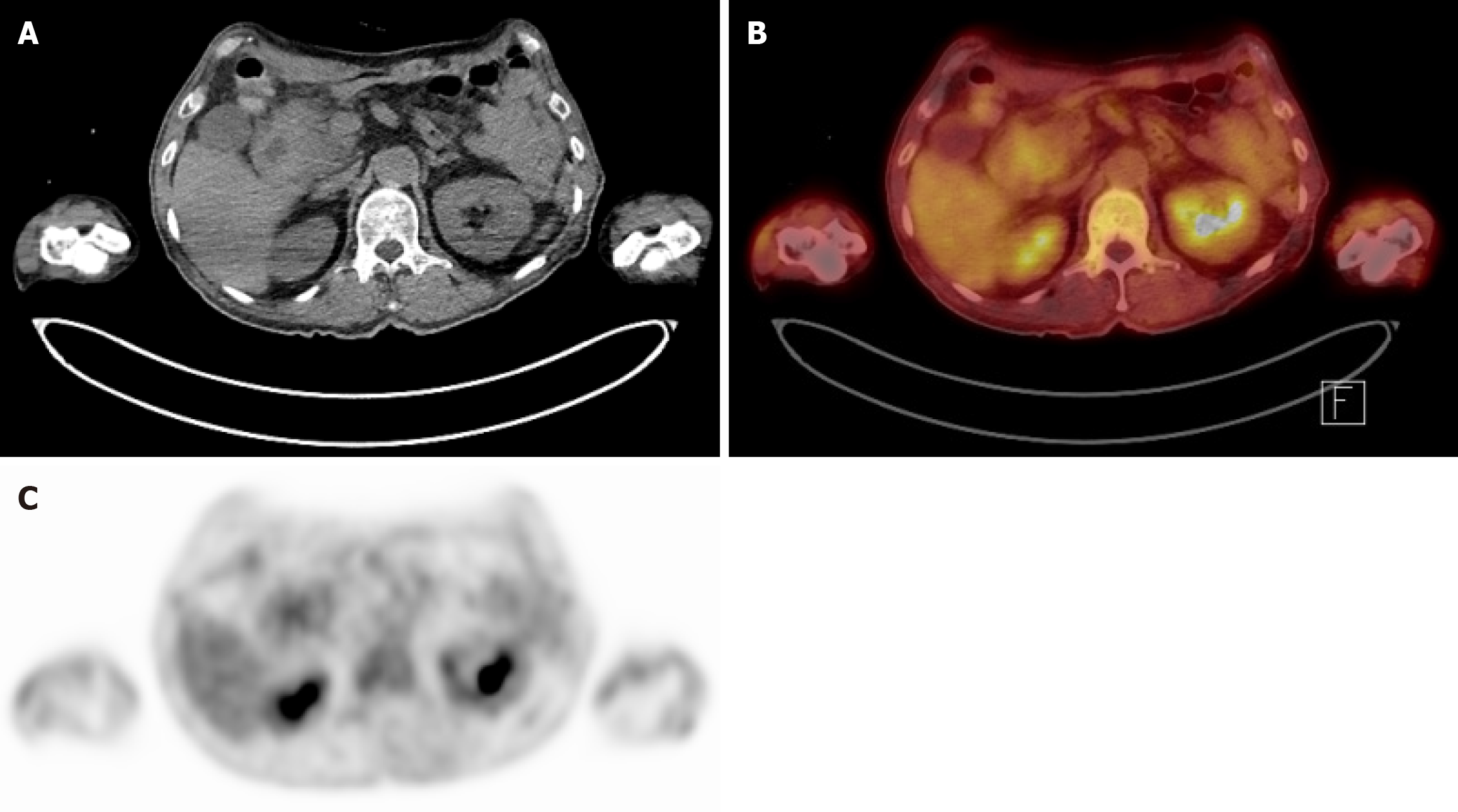

After the patient was stabilized post-arrest, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed and a mass-like lesion was identified at the transition from the duodenal bulb (Figure 3A) to the second segment. Consequently, biopsy was performed on the lesion; however, EGD was unable to scope beyond the second segment due to obstruction by the lesion. The EGD biopsy revealed a hyperplastic polyp with granulation tissue and lymphangiectasia. However, upon endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, no mass was observed at the AoV (Figure 3B). Therefore, re-biopsy was performed at the suspicious mass-like lesion of the duodenal bulb mass, revealing Brunner’s gland hyperplasia. Further laboratory tests revealed a serum amylase level of 91 IU/L and a lipase level within the normal range at 59 IU/L. The tumor marker carcinoembryonic antigen was mildly elevated at 10.7 ng/mL, whereas the carbohydrate antigen 19-9 Level remained within the normal range. Positron emission tomography-CT was also performed, revealing a mild hypermetabolic mass-like lesion in the second portion of the duodenum near the AoV (standardized uptake value 2.9) of unknown clinical significance (Figure 4). Given these findings, complete exclusion of malignancy was not possible, and surgical intervention was considered necessary for definitive diagnosis and treatment.

Preoperatively, AoV or duodenal cancer was suspected, however, no cancer cells were found in the biopsy. Therefore, there was also a possibility of benign duodenal stricture. Postoperatively, histological inspection of the specimen revealed multiple cystic lesions in the duodenal wall, involving the adjacent pancreatic parenchyma, heterotopic pancreas in the duodenal wall, and Brunner’s gland hyperplasia. These were collectively diagnosed as GP.

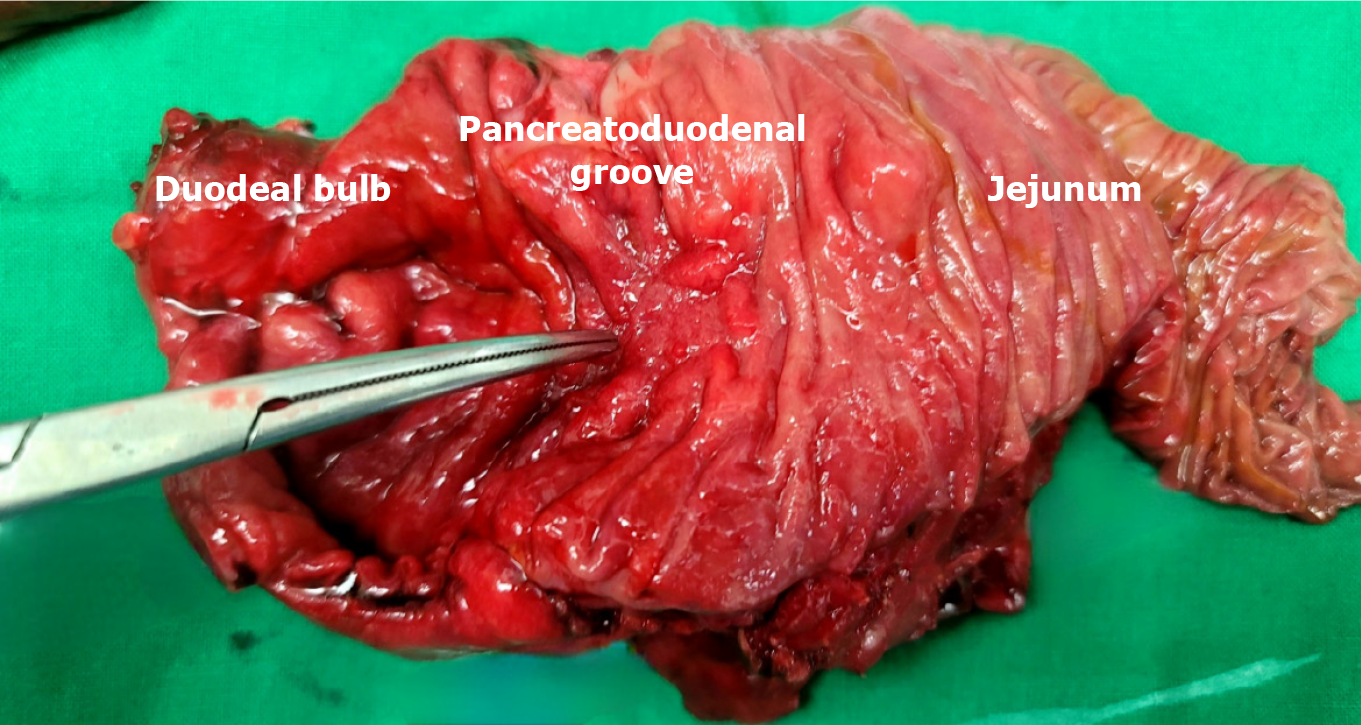

Although the imaging and biopsy findings were inconsistent, the obstruction persisted for more than 2 weeks, resulting in a daily drainage of 700-1000 mL of gastric content through the patient’s Levin tube. Since it was difficult to completely exclude cancer from the differential diagnosis, a pylorus-resecting PD was performed. Intraoperatively, we observed a hard pancreas with severe fibrosis and fibrosis of surrounding duodenal tissue, indicating that the patient had chronic pancreatitis. Moreover, upon inspection of the specimen observed through an incision along the duodenum, the mass that was suspected to be cancer upon preoperative imaging was not observed in the duodenal bulb or AoV (Figure 5).

Postoperatively, the patient did not vomit after the removal of the Levin tube and was discharged after slowly building up a diet without any major problems. The patient was followed up in the outpatient clinic 3 years postoperatively and was found to be doing well on the diet, with no postoperative sequelae (Figure 6). Laboratory tests performed at that time showed an amylase level of 29 IU/L, a lipase level of 7 IU/L, and normal liver function tests. However, as the patient’s alcohol abstinence was not well maintained, continuous counseling and education were provided.

GP is a rare form of focal chronic pancreatitis involving the head of the pancreas, duodenum, and the space enclosed by the common bile duct[6]. In previous studies, GP has been divided into two types based on the extent of inflammation: The “pure” form, which is limited to the pancreaticoduodenal groove, and the “segmental” or “diffuse” form, which involves the main pancreatic duct (p-duct) - including the adjacent pancreas - causing upstream dilatation and obstructive chronic pancreatitis[1,7]. In rare cases, GP can also harbor pancreatic cancer or be accompanied by precancerous lesions such as pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasm or intraductal papillary neoplasm[8]. In the present case, GP was of the diffuse type, with main p-duct dilatation, and was accompanied by low-grade pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasm.

The etiological factors of GP remain controversial, however, internal and external factors are both involved. Internal factors include the presence of pancreatic tissue at the level of the minor papilla within the duodenal wall due to abnormal migration of the dorsal pancreatic bud, whereas external factors include alcohol abuse and smoking[7]. Additionally, secondary changes in local anatomy such as gastric ulcers, duodenal ulcers, and gastrectomy can cause GP[3,9]. In particular, alcohol abuse has been reported to have a significant impact on GP because it increases the viscosity of pancreatic juice, causing retention and interference with outflow[7]. This long-term irritation leads to fibrosis and calcification of the Santorini duct and minor papilla and causes inflammation of the pancreaticoduodenal groove[9].

In most cases of GP, an accurate diagnosis can be made after surgery, and the differential diagnosis of pancreatic, distal bile duct, duodenal, and AoV cancers is important, but difficult[7,10]. Laboratory findings are generally unremarkable but may occasionally be accompanied by elevated amylase and lipase levels[9]. Moreover, the carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 Levels are not commonly elevated, which is useful in the differential diagnosis of periampullary cancer[10].

Diagnostic imaging modalities for GP include CT, MRI, and endoscopic sonography[10,11]. Notably, a contrast-enhanced CT scan for GP shows soft tissue with delayed enhancement between the duodenum and the pancreatic head[6]. Other CT findings include duodenal wall thickening and, occasionally, paraduodenal cyst, moreover, in diffuse-type GP, non-enhancing lesions may be observed in the pancreas head, making differentiation from pancreatic cancer more difficult[12]. Furthermore, MRI findings can assist in the differential diagnosis of GP when multiple hyperintense fi

There are several options for the treatment of GP, the first being to stop drinking, followed by conservative treatment with pain control and pancreatic rest with total parenteral nutrition[17]. This approach reduces pancreatic inflammation and promotes improvement in nutritional status prior to surgical intervention[7]. In addition, if pseudocysts or p-duct stenosis exist, endoscopic treatments such as cystogastrostomy, p-duct stent insertion and bile duct stent insertion can be performed[4,17,18]. However, surgical treatment is indicated when the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cancer or periampullary cancer is very difficult and obstructive symptoms are sometimes severe or do not improve[15,16]. The most commonly performed surgery in these cases is PD - sometimes with bypass surgery[18,19] due to duodenal ob

Despite two separate endoscopic biopsies and positron emission tomography-CT evaluation, malignancy could not be entirely excluded; therefore, PD was performed for both definitive diagnosis and treatment. While conservative treatment may be effective in mild or nonspecific GP, in this case, complete gastric outlet obstruction and persistent high-volume nasogastric drainage made non-surgical management impossible. Given the inability to rule out periampullary cancer, PD provided both symptom relief and a conclusive pathological diagnosis. However, as this is a single case report, treatment recommendations should be interpreted with caution. Extensive procedures such as PD carry substantial postoperative risks and must be undertaken only after thorough evaluation.

GP can be diagnosed based on a combination of histological, imaging, and laboratory findings. If the cancer is clearly differentiated or the obstruction is not severe, conservative or endoscopic treatment can be performed. However, if cancer cannot be completely excluded or is accompanied by uncommon total gastric outlet obstruction, PD is considered a safe and important treatment option for symptom management and a clear pathological diagnosis.

| 1. | Aguilera F, Tsamalaidze L, Raimondo M, Puri R, Asbun HJ, Stauffer JA. Pancreaticoduodenectomy and Outcomes for Groove Pancreatitis. Dig Surg. 2018;35:475-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gábos G, Nicolau C, Martin A, Moșteanu O. Groove Pancreatitis-Tumor-like Lesion of the Pancreas. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Adsay NV, Zamboni G. Paraduodenal pancreatitis: a clinico-pathologically distinct entity unifying "cystic dystrophy of heterotopic pancreas", "para-duodenal wall cyst", and "groove pancreatitis". Semin Diagn Pathol. 2004;21:247-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ukegjini K, Steffen T, Tarantino I, Jonas JP, Rössler F, Petrowsky H, Gubler C, Müller PC, Oberkofler CE. Systematic review on groove pancreatitis: management of a rare disease. BJS Open. 2023;7:zrad094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Berral Santana AM, Cedrún Sitges I. Groove pancreatitis and how to differentiate it from pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Radiologia (Engl Ed). 2023;65:81-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Triantopoulou C, Dervenis C, Giannakou N, Papailiou J, Prassopoulos P. Groove pancreatitis: a diagnostic challenge. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:1736-1743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | de Pretis N, Capuano F, Amodio A, Pellicciari M, Casetti L, Manfredi R, Zamboni G, Capelli P, Negrelli R, Campagnola P, Fuini A, Gabbrielli A, Bassi C, Frulloni L. Clinical and Morphological Features of Paraduodenal Pancreatitis: An Italian Experience With 120 Patients. Pancreas. 2017;46:489-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lugo-Fagundo E, Weisberg EM, Fishman EK. Pancreatic cancer in patient with groove pancreatitis: Potential pitfalls in diagnosis. Radiol Case Rep. 2022;17:4632-4635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | DeSouza K, Nodit L. Groove pancreatitis: a brief review of a diagnostic challenge. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:417-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Patel BN, Brooke Jeffrey R, Olcott EW, Zaheer A. Groove pancreatitis: a clinical and imaging overview. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2020;45:1439-1446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kalb B, Martin DR, Sarmiento JM, Erickson SH, Gober D, Tapper EB, Chen Z, Adsay NV. Paraduodenal pancreatitis: clinical performance of MR imaging in distinguishing from carcinoma. Radiology. 2013;269:475-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Nanjaraj C, Basavaraj B, Manupratap N, Shashikumar M, Rajendrakumar N, PraveenKumar M, Rashmi T. Groove pancreatitis-a great mimicker. BJR Case Rep. 2016;2:20150316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Raman SP, Salaria SN, Hruban RH, Fishman EK. Groove pancreatitis: spectrum of imaging findings and radiology-pathology correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:W29-W39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Balaban M, Balaban DV, Mănucu G, Bucurică SN, Costache RS, Ioniță-Radu F, Jinga M, Gheorghe C. Groove Pancreatitis in Focus: Tumor-Mimicking Phenotype, Diagnosis, and Management Insights. J Clin Med. 2025;14:1627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Monrabal Lezama M, Angeramo CA, Nazar ME, Capitanich P, Schlottmann F. Groove Pancreatitis and Gastric Outlet Obstruction. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;25:3001-3003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang YL, Tong CH, Yu JH, Chen ZL, Fu H, Yang JH, Zhu X, Lu BC. Complete duodenal obstruction induced by groove pancreatitis: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:4106-4110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kager LM, Lekkerkerker SJ, Arvanitakis M, Delhaye M, Fockens P, Boermeester MA, van Hooft JE, Besselink MG. Outcomes After Conservative, Endoscopic, and Surgical Treatment of Groove Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:749-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Louis M, Grabill N, Ayinde B, Gibson B. Gastric Outlet Obstruction Secondary to Groove Pancreatitis Mimicking Pancreatic Cancer. Cureus. 2025;17:e77590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhang Y, Cheng HH, Fan WJ. Duodenojejunostomy treatment of groove pancreatitis-induced stenosis and obstruction of the horizontal duodenum: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;15:2945-2953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ooka K, Singh H, Warndorf MG, Saul M, Althouse AD, Dasyam AK, Paragomi P, Phillips AE, Zureikat AH, Lee KK, Slivka A, Papachristou GI, Yadav D. Groove pancreatitis has a spectrum of severity and can be managed conservatively. Pancreatology. 2021;21:81-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Agarwal L, Rathore KS, Varshney VK, Soni S, Selvakumar B, Varshney P, Agarwal A, Verma V, Sureka B, Yadav T. Surgical Management of Groove Pancreatitis: Lessons Learnt and Long-Term Experience. Dig Dis Sci. 2025;70:2521-2533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/