Published online Nov 6, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i31.109113

Revised: May 29, 2025

Accepted: August 25, 2025

Published online: November 6, 2025

Processing time: 182 Days and 22.7 Hours

Herbal supplements are increasingly used to manage menopausal symptoms. Physta® is a commercial herbal ingredient containing Eurycoma longifolia standardized water extract, traditionally used for vitality. Its adaptogenic and anti-inflammatory properties promote hormonal balance, physical function, and sexual health, supporting its potential benefits for menopausal health.

To investigate Physta®’s role in improving menopausal quality of life, mood states, and overall safety profile compared with placebo.

In this 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 138 females aged 40–55 with menopausal symptoms were randomly assigned to receive Physta® 50 mg, Physta® 100 mg, or placebo. MENQOL and POMS were assessed at baseline, week 6, and week 12. Safety outcomes were evaluated through biochemical tests, vital signs, and female reproductive hormonal profile.

Physta® 100 mg significantly reduced total MENQOL scores by 33.9% from baseline to week 12 (P = 0.049) with notable improvements in the physical (-36.4%, P = 0.046) and sexual (-36.3%, P = 0.043) domains. Total mood disturbance also declined more in the Physta® 100 mg group (-38.6%) compared with placebo (-30.1%), although not statistically significant. No significant changes were observed in the vital signs and biochemical parameters, indicating the safety and tolerability of Physta®. No significant alterations were found in the female reproductive hormone profile, supporting its hormonal neutrality.

Physta® 100 mg improved menopausal quality of life and mood without adverse effects, supporting its potential as a safe herbal therapy. Further studies with higher doses and longer durations are needed.

Core Tip: Physta® supplementation, particularly at the 100 mg dosage, showed potential in improving quality of life, sexual function, and physical function among menopausal females without significantly altering their vital signs, biochemical parameters, and reproductive hormone levels.

- Citation: Muniandy S, Yahya HM, Shahar S, Kamisan Atan I, Mahdy ZA, Rajab NF, Mohd Rasdi HF, George A, Chinnappan SM. Effect of Eurycoma longifolia water extract (Physta®) on menopausal quality of life and mood states. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(31): 109113

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i31/109113.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i31.109113

Menopause is an inevitable growth phase experienced by females typically from the ages of 45 to 55 years. It is caused by a decline in ovarian hormones, estrogen, and progesterone[1,2]. With 3.763 billion of the world’s female population, there are around 1.2 billion women in the perimenopausal and postmenopausal transition phase at any given time worldwide[3]. This trend is undeniably influenced by the rise in global life expectancy, leading to females spending a significant one-third of their lives in the postmenopausal phase. Menopause is more than just the end of their ability to procreate; it also causes several physical, sexual, and psychological symptoms. These symptoms include headaches, fatigue, weight gain, hot flashes, sleep disturbances, joint pain, mood swings, poor memory, vaginal dryness, and decreased muscle mass[2,4,5]. The presence, duration, and severity of menopausal symptoms can vary prominently from person to person and potentially influence the day-to-day quality of life (QOL) of females[6]. These variations are due to factors such as genetics, lifestyle, culture, socioeconomic status, education level, and dietary habits[7].

Given that menopause is an inevitable phase of life for all females, the scientific community must look at the different aspects of menopausal symptoms and how they affect QOL as a whole[8]. Although hormone therapy is effective for managing menopausal symptoms, its long-term usage is a subject of debate due to possible adverse effects like cancer, cardiovascular disease, and stroke[9]. As a result, research on using herbal food supplements as phytochemicals to reduce menopausal symptoms is ongoing all over the world. Menopausal symptoms may be alleviated by taking dietary supplements containing black cohosh, red clover, black seeds, ashwagandha, garlic, dong quai, fennel, cardamom, flex seeds, licorice, soy, sea buckthorns, and evening primrose oil, among other medicinal herbs[10,11].

In Malaysia, local herbs like Pucuk sendup (Arcypteris irregularis), Tongkat Ali [Eurycoma longifolia (EL)], Bunga pakma (Rafflesia hasseltii), and Kacip Fatimah (Labisia pumila) are commonly utilized in rural areas to relieve menopausal symptoms[11]. Since not all herbal supplements are proven for safety to be consumed over an extended period of time, more clinical research is required to validate their efficacy, safety and the proper dosage.

To date, many randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessing herbal and dietary supplements have relied predominantly on self-reported questionnaires to evaluate outcomes, particularly psychological symptoms[12]. However, subjective symptom assessment alone is insufficient to comprehensively determine these interventions' physiological effectiveness. The inclusion of objective biomarkers, specifically hormonal measurements such as progesterone, testosterone, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and estradiol, is crucial for a more robust evaluation of treatment efficacy[13]. These hormone levels provide direct insight into endocrine function and the biological impact of the supplements, allowing for more accurate conclusions about their therapeutic potential.

EL Jack has been an important medicinal plant utilized by traditional healers, particularly in native communities of Malaysia. Referred to as ‘Tongkat Ali’ in Malaysia, infusion of its roots has been traditionally used among locals to enhance male vitality and as a postpartum energy tonic for females after delivery[14]. EL is commonly consumed for energy and strength, improved mood and libido, sports performance, stress management, and hormonal imbalances[15-17]. Notably, the roots of EL constitute 66 bioactive compounds such as eurycomanone, 13α (21)- epoxyeurycomanone, eurycomanol, eurycomanol-2-O-β-ᴅdglucopyranoside, and 13, 21-dihydroeurycomanone, which play a huge role in treating various ailments, including sexual dysfunction, dysentery, aging, anxiety, osteoporosis, and glandular swelling, apart from serving as a general health supplement[18,19].

In a study by Talbott et al[15] involving adults with moderate stress, EL supplementation improved the stress hormone profiles and mood aspects[15]. Moreover, the active compounds such as alkaloids and triterpenes in EL possess antioxidant properties that could reduce bone loss and sustain bone formation rates[20]. Furthermore, EL has shown potential in regulating reproductive hormones and bone biomarkers among ovariectomized rats, offering a possible avenue for managing hormonal imbalances and menopausal symptoms in women[21].

Due to its extensive history of usage as a traditional therapeutic herb, its safety profile has been demonstrated through various animal and human studies, as well as its adaptogenic or anti-inflammatory properties[16,22-24]. This three-arm, placebo-controlled, 12-week study aimed to determine the efficacy of Physta®, a standardized water extract of EL, at a dosage of 50 mg and 100 mg, on menopausal QOL and mood states of menopausal females from the Klang Valley region, Selangor, Malaysia. This study ensured a comprehensive assessment as it incorporated both subjective measures, such as self-reported questionnaires on mood and QOL and objective measures, including hormonal profiling, to evaluate the physiological impact of the intervention. We hypothesized that Physta® supplementation would significantly improve menopause-specific QOL (MENQOL) and mood states compared with placebo without adverse effects on safety parameters.

The detailed study protocol of this entire RCT study was published elsewhere in 2023[11]. Out of all the primary and secondary outcome measures outlined in the study protocol, MENQOL, profile of mood states (POMS), anthropometric and vital measurements, reproductive hormone profiling and biochemical parameters were discussed in this article.

Physta® is a standardized water extract of EL manufactured, packaged, and registered under the National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Agency by the study sponsor, Biotropics Malaysia Berhad. Finished products are in the form of capsules containing either 50 mg of Physta® with 300 mg maltodextrin (registration number MAL18056060T), 100 mg of Physta® extract with 250 mg maltodextrin (registration number MAL09051452T), or 280 mg of maltodextrin, which acts as a look-alike placebo that was indistinguishable in size, color, and shape.

This was a 12-week randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, three-arm parallel group study (1:1:1) conducted among females aged 40 to 55 residing in the Klang Valley region of Selangor, Malaysia. The official study site was at the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Clinic, Hospital Canselor Tuanku Muhriz, a teaching hospital of the National University of Malaysia. The study was conducted from November 30, 2022 to May 15, 2024.

The sample size for the study was calculated using G-power software[25]. Utilizing the software’s F-test with repeated measures within-between interaction, the following parameters were inputted: Effect size (f) = 0.25; alpha error probability = 0.05; power = 0.8; number of study groups = 3; and number of measures = 4. The total sample size calculated was 113 participants. To account for a prospective drop-out (20%), 135 participants were set as the target sample size for the study. Hence, 138 participants were enrolled and randomized, and 112 completed the study.

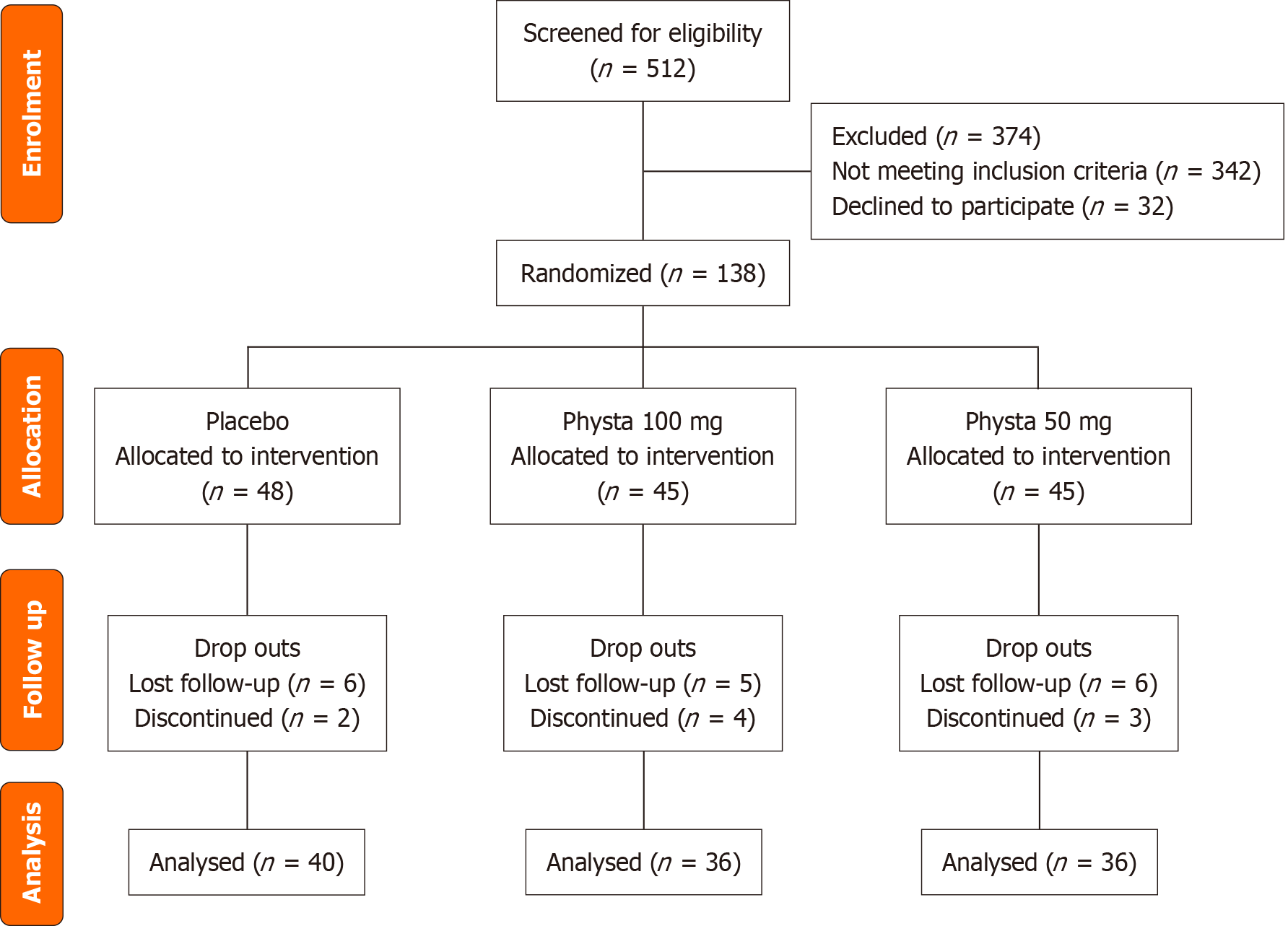

Using the purposive sampling method, females aged 40 to 55 years with intact uterus and ovaries and a body mass index (BMI) range from 18-29.9 kg/m2 were included in the study. The presence and severity of the menopausal symptoms experienced by the participants were assessed using a self-administered MENQOL questionnaire. Participants scoring more than or equal to 61 in the MENQOL assessment were included in the study[26]. The study excluded females who were pregnant, nursing, had undergone major surgery within the previous year, had a medical history of hysterectomy, induced menopause, mental illness, uncontrolled hyperlipidemia, uncontrolled diabetes, uncontrolled hypertension, or who were receiving hormonal therapy. This study's inclusion and exclusion criteria were detailed in the study protocol paper[16]. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram is illustrated in Figure 1.

Each participant gave their informed consent before being enrolled in the study, guaranteeing the privacy and confidentiality of their information. Comprehensive information that included sociodemographic details, medical history, and anthropometric measurements, including vital signs, was reviewed at the baseline. Each participant was randomized into one of the three study groups using a computer-generated randomization list prepared in advance by an independent researcher. No stratification based on menopausal status or other variables was used. The investigational products were dispensed as a daily dietary herbal supplement (one capsule daily after breakfast) for 12 weeks. This was a double-blind study where participants and investigators were blinded to the treatment allocation throughout the trial to minimize bias and the influence of placebo effects. The capsules for all three groups (Physta® 50 mg, Physta® 100 mg, and placebo) were identical in size, color, shape, texture, and taste to ensure indistinguishability. A unique blinding code was assigned and maintained securely by the study sponsor. This blinding code was not revealed until data collection and statistical analysis were completed.

The primary outcome measures, the POMS and MENQOL questionnaires, were administered at baseline and during follow-up visits at week 6 and week 12, along with compliance checking by performing a capsule count. Compliance was calculated as the percentage of capsules taken relative to dispensed, and participants with less than 70% adherence were considered non-compliant. Adverse events were monitored throughout the study by participant self-report and investigator inquiry at each visit. All events were recorded, including their severity and possible relation to the study supplement. For secondary safety outcome measures, blood and urine samples were collected at all visits for commercial laboratory analysis to assess complete blood count, liver function, fasting glucose level, renal function, lipid profile, and reproductive hormone profile. Participants who did not attend the follow-up visits were excluded from the study.

MENQOL assessment: MENQOL is a self-administered tool developed by Hilditch[19], comprising 29 Likert-scale items distributed across four domains: “Vasomotor” (3 items); “psychosocial” (7 items); “physical” (16 items); and “sexual” (3 items)[19]. The scoring of this widely utilized questionnaire adheres to an eight-point Likert scale during data collection. For data entry, a score of 1 is given for ‘no’, indicating that the specific symptom was not experienced at all in the past month. A score of ‘yes’ signified the presence of the symptom, and the score range for ‘yes’ was 2 to 8, implying the severity of the distress associated with the presence of the specific symptom in the past month. The scores of each domain were obtained by calculating the average (mean) scores of the items in each domain. The systematic scoring for each of the four domains was identical. The level of QOL based on menopausal symptoms severity was assessed based on the mean scores of each domain, where 0-1 indicated no symptom and decline in QOL, 2-4 indicated mild symptoms and decline in QOL, 5-6 indicated moderate symptoms and decrease in QOL, and 7-8 indicated severe symptoms and decline in QOL[7,20].

POMS assessment: The POMS, a self-administered tool, was used to assess the six main psychological characteristics (tension, depression, anger, fatigue, vigor, and confusion) often linked to mood. It is a well-known assessment tool for its validity with almost 3000 studies having utilized it. POMS employs 65 adjective-based intensity scales on a hedonic scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). These 65 adjective responses were classified, tabulated, scored, and analyzed as six mood domains (tension, depression, anger, fatigue, vigor, and confusion).

All blood samples were collected in the morning (between 8:00-10:00 AM) following an overnight fast to minimize diurnal variation. A qualified phlebotomist collected 14 mL of peripheral venous blood from the antecubital fossa: 10 mL in a yellow tube and 4 mL in an EDTA purple tube. Tubes were labelled with participant details, gently rotated eight times, and stored at 4 °C in a portable chiller. Urine samples were collected in labelled sterile containers and placed in biohazard bags. All samples were promptly sent to a commercial clinical laboratory for automated analysis, including complete blood count, liver and renal function tests, fasting glucose, urine analysis, and lipid profiling. Female reproductive hormone profile analysis was carried out using serum samples. Progesterone levels were quantified with immunoassay techniques, whereas serum testosterone, FSH, LH and estradiol levels were determined using chemiluminescent immunoassays.

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS version 23.0 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, IBM Corp. Released 2015. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0 Armonk, NY, United States). Data normality and homogeneity of variance were assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test before analysis. The analyzed data were reported as mean ± SD, frequency or percentage with 95% confidence interval. The effects of Physta® supplementation across visits and group comparisons were analyzed using a mixed one-way analysis of variance. An independent t-test was conducted to study the variation between groups, while a paired t-test was used for within-group effects across each visit. All tests were two-tailed, with P values less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Out of the 512 participants screened, 138 participants were recruited into the study. They were randomized and assigned to the Physta® 100 mg (n = 45), Physta® 50 mg (n = 45), and placebo (n = 48) groups (Figure 1). Throughout the 12 weeks, 26 participants dropped out and were excluded from the study for either loss of follow-up (n = 17) or discontinued the study for personal reasons (n = 9). The 112 participants completing the 12-week study reflected a 19% dropout rate. This was within the anticipated 20% attrition accounted for during sample size calculation. The baseline characteristics were comparable across groups, and no significant differences were found between completers and non-completers, minimizing the likelihood of systematic bias affecting the outcomes. No adverse events were reported by the participants throughout the study. The compliance with treatment was 98.3%.

For the analysis of the results, data from 112 participants [Physta® 100 mg (n = 36), Physta® 50 mg (n = 36), and placebo (n = 40)] who completed the 12-week study were included, and their baseline sociodemographic characteristics are reported in Table 1. The majority ethnic group in all three groups (94% in the Physta® 100 mg group, 100% in the Physta® 50 mg group, and 96% in the placebo group) was Malay. Most participants worked (85%) and had various fixed monthly incomes.

| Characteristic | Placebo (n = 40) | Physta® 50 mg (n = 36) | Physta® 100 mg (n = 36) | Total (n = 112) |

| Age | ||||

| 40-44 | 8 (20) | 12 (33) | 11 (31) | 31 (28) |

| 45-49 | 24 (60) | 14 (39) | 16 (44) | 54 (48) |

| 50-55 | 8 (20) | 10 (28) | 9 (25) | 27 (24) |

| Ethnicity Malay | 38 (95) | 36 (100) | 34 (94) | 108 (96) |

| Chinese | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Indian | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) |

| Others | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Education level | 5 (12) | 9 (25) | 4 (11) | 18 (16) |

| Certificate/diploma | 16 (40) | 11 (31) | 10 (28) | 37 (33) |

| Degree | 19 (48) | 16 (44) | 22 (61) | 57 (51) |

| Working status | ||||

| Not working | 3 (7) | 9 (25) | 5 (13) | 17 (15) |

| Working | 37 (93) | 27 (75) | 31 (87) | 95 (85) |

The mean scores of MENQOL by domains at baseline, week 6 and week 12 for all study groups are shown in Table 2. No significant group effect or interaction (group and time) effect was observed. However, the total MENQOL score showed a greater reduction from baseline to week 12 in the Physta® 100 mg group (119.11 ± 35.52 to 78.75 ± 37.64) compared with the Physta® 50 mg (104.67 ± 33.39 to 78.58 ± 38.15) and placebo (104.95 ± 35.48 to 80.45 ± 37.27) groups. The total MENQOL mean score reduction at week 12 from baseline was more evidently and significantly seen in the Physta® 100 mg group (-40.64 ± 34.76, -33.9%) compared with placebo (-24.50 ± 36.46, -23.3%), P = 0.049, η² = 0.097, power = 0.516, whereas Physta® 50 mg (-26.08 ± 49.61, -24.9%) compared with the placebo group (-24.50 ± 36.46, -23.3%) was insignificant at P = 0.874.

| Parameter | Placebo (n = 40) | Physta® 50 mg (n = 36) | Physta® 100 mg (n = 36) | ||||||

| Baseline | Week 6 | Week 12 | Baseline | Week 6 | Week 12 | Baseline | Week 6 | Week 12 | |

| MENQOL | |||||||||

| Vasomotor | 3.12 ± 1.80 | 2.59 ± 1.60b | 2.41 ± 1.27c | 3.35 ± 2.12 | 2.43 ± 1.32b | 2.51 ± 1.49 | 3.68 ± 2.09 | 2.94 ± 1.74b | 2.45 ± 1.67d |

| Psychosocial | 3.12 ± 1.36 | 2.49 ± 1.33b | 2.61 ± 1.22d | 3.00 ± 1.48 | 2.53 ± 1.34b | 2.51 ± 1.43d | 3.62 ± 1.60 | 2.75 ± 1.22b | 2.65 ± 1.47d |

| Physical | 3.98 ± 1.27 | 2.91 ± 1.22b | 2.93 ± 1.48d | 3.94 ± 1.18 | 2.96 ± 1.14b | 2.85 ± 1.37d | 4.45 ± 1.15 | 2.99 ± 1.12b | 2.83 ± 1.33d,f |

| Sexual | 3.38 ± 1.94 | 2.58 ± 1.44b | 2.69 ± 1.46c | 3.53 ± 1.76 | 2.81 ± 1.34a | 2.65 ± 1.46d | 3.94 ± 1.86 | 2.69 ± 1.51b | 2.51 ± 1.46d,f |

| Total MENQOL | 104.95 ± 35.48 | 79.53 ± 33.43b | 80.45 ± 37.27d | 104.67 ± 33.39 | 80.72 ± 31.25b | 78.58 ± 38.15d | 119.11 ± 35.52 | 83.92 ± 32.42b | 78.75 ± 37.64d,f |

| POMS | |||||||||

| Tension | 9.03 ± 4.81 | 8.10 ± 5.10 | 8.33 ± 4.69 | 10.14 ± 5.69 | 9.44 ± 5.02 | 9.03 ± 5.17 | 10.89 ± 6.34 | 9.92 ± 6.61 | 8.53 ± 5.19c |

| Depression | 9.05 ± 8.16 | 7.85 ± 10.47 | 8.03 ± 9.37 | 10.28 ± 11.55 | 10.97 ± 10.96 | 9.72 ± 9.60 | 13.17 ± 12.98 | 11.39 ± 12.08 | 8.97 ± 9.60d |

| Anger | 9.45 ± 6.98 | 8.08 ± 8.49 | 8.25 ± 6.92 | 10.36 ± 8.33 | 10.36 ± 8.28 | 9.33 ± 8.11 | 12.50 ± 9.14 | 10.83 ± 10.00 | 10.78 ± 11.85 |

| Vigor | 17.70 ± 3.98 | 18.25 ± 4.87 | 19.20 ± 4.86 | 19.00 ± 5.74 | 18.83 ± 6.10 | 19.22 ± 5.35 | 17.06 ± 5.24 | 18.38 ± 4.96 | 18.03 ± 4.97 |

| Fatigue | 8.73 ± 4.97 | 6.30 ± 5.45b | 6.20 ± 5.36d | 9.14 ± 5.91 | 7.58 ± 5.28 | 6.25 ± 5.14c | 11.36 ± 6.07 | 7.50 ± 5.80b | 7.17 ± 8.17d |

| Confusion | 7.97 ± 4.18 | 6.55 ± 4.15a | 6.95 ± 3.86 | 7.36 ± 4.28 | 7.50 ± 4.14 | 6.64 ± 3.87 | 8.42 ± 4.80 | 7.36 ± 5.03 | 6.69 ± 4.28c |

| Total mood disturbance | 26.53 ± 27.30 | 18.63 ± 31.63 | 18.55 ± 28.88 | 28.28 ± 34.66 | 27.03 ± 31.50 | 21.75 ± 30.06 | 39.28 ± 37.61 | 28.72 ± 37.12a | 24.11 ± 35.48d |

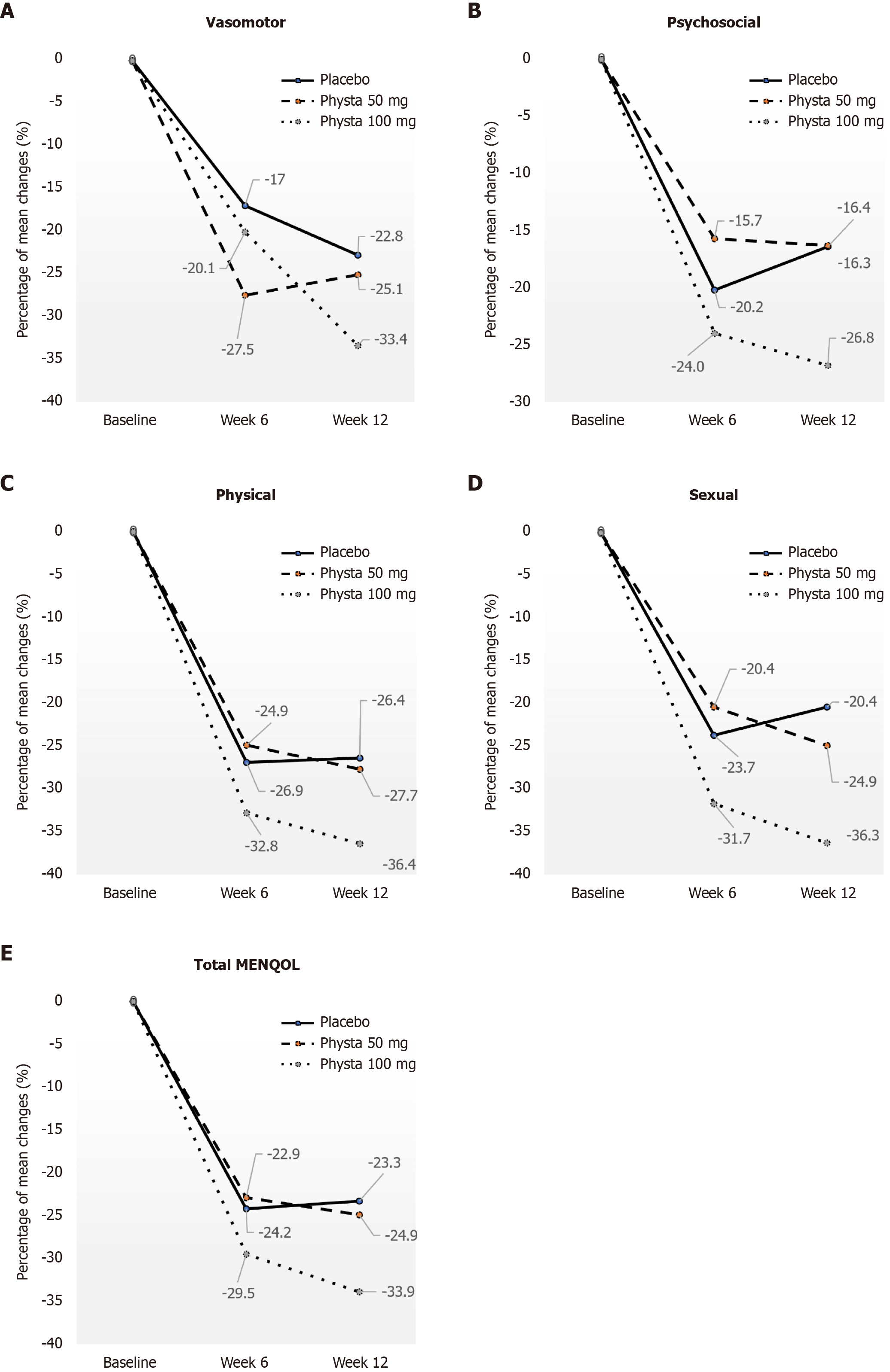

In the physical domain, the mean scores for the Physta® 100 mg group compared with the placebo from baseline to week 12 were statistically significant (-36.5%, P = 0.046, η² = 0.067, power = 0.612), implying there was a significant improvement in the physical domain in the Physta® 100 mg group. Likewise, the sexual domain demonstrated a significant change in mean score between the placebo and Physta® 100 mg groups from baseline to week 12 (-36.3%, P = 0.043, η² = 0.101, power = 0.544), denoting a significant improvement of the sexual domain in the Physta® 100 mg group. The percentage of MENQOL mean score changes across the domains for all three groups at different time points is illustrated in Figure 2.

When comparing the within-group effects, the MENQOL mean scores for all four domains significantly decreased from baseline to week 6 and to week 12 across all groups, including placebo (Table 2). The between-group comparisons indicated a higher reduction of mean scores in the Physta® 100 mg group compared with the other groups for all the domains from baseline to week 6 and then to week 12. The percentage of MENQOL mean score changes at week 12 compared with baseline for the Physta® 100 mg group showed more than a 30% reduction for all MENQOL domains, vasomotor (-33.4%) and psychosocial (-26.8%) with physical (-36.4%) and sexual (-36.3%) domains particularly reaching significance compared with placebo at P = 0.046 and P = 0.043, respectively (Figure 2). The week 12 mean scores were compared with the baseline for all domains of Physta® 50 mg, and the placebo group also showed a reduction. Still, the percentage of change of the mean score of Physta® 50 mg was greater than placebo [vasomotor (-25.1% vs -22.8%), psychosocial (-16.4% vs -16.3%), physical (-27.7% vs -26.4%), and sexual (-24.9% vs -20.4%)].

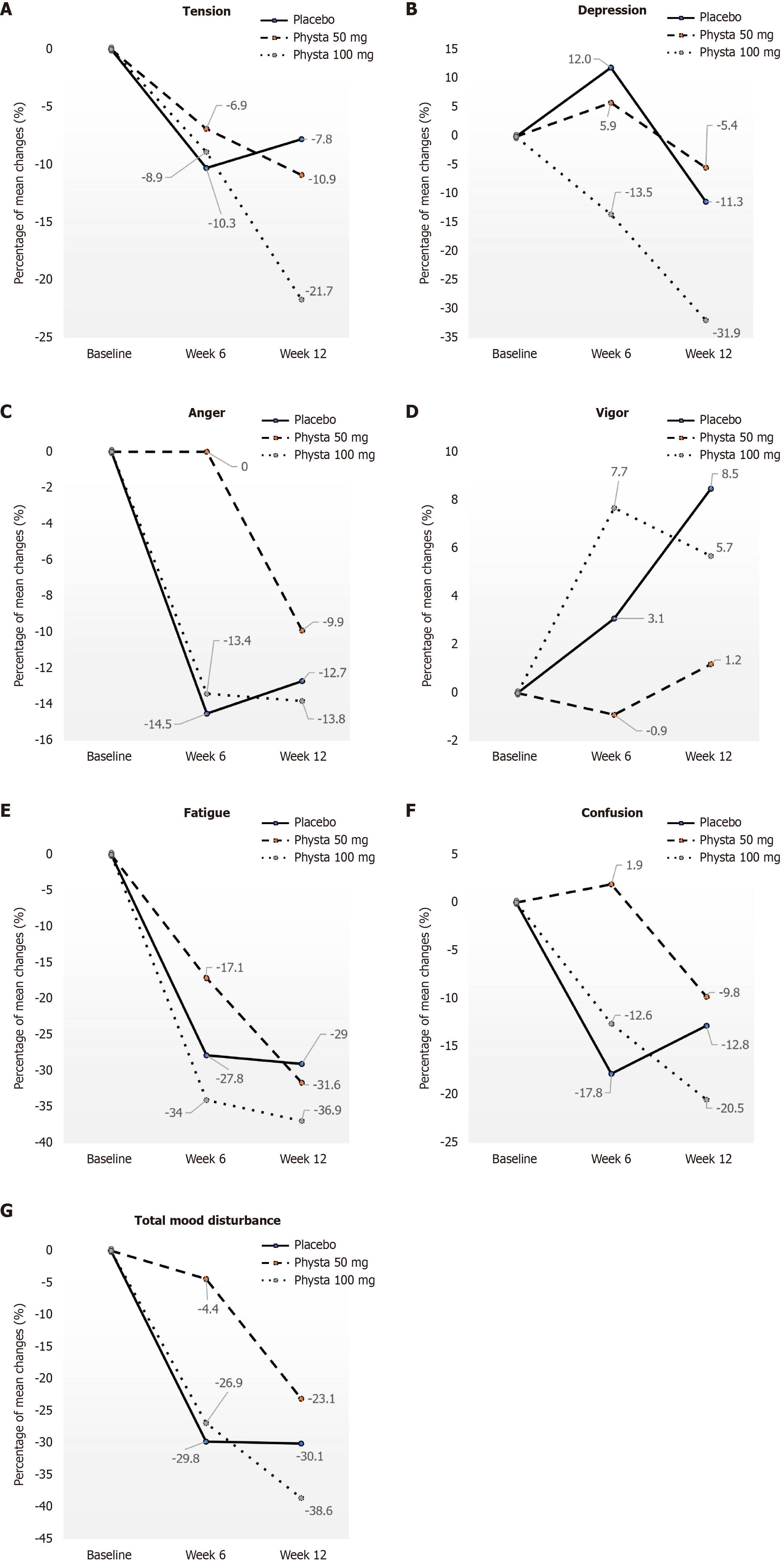

No significant intervention effect or between-group effects were observed. However, a decreasing trend was observed in terms of the mean scores of POMS by visit and some significant within-group effects (Table 2). The total mood disturbance score decreased more from baseline to week 12 in the Physta® 100 mg group (39.28 ± 37.61 to 24.11 ± 35.48) compared with the Physta® 50 mg (28.28 ± 34.66 to 21.75 ± 30.06) and placebo (26.52 ± 27.30 to 18.55 ± 28.88) groups. The percentage of change of POMS mean scores observed among all three groups at different weeks is illustrated in Figure 3. The total mood disturbance scores showed reduction at week 12 from baseline was more evidently seen in the Physta® 100 mg group (-15.17 ± 24.84, -38.6%) compared with placebo (-7.98 ± 27.30, -30.1%, P = 0.235) and Physta® 50 mg (-6.53 ± 31.22, -23.1%) and placebo (-7.97 ± 27.30, -30.1%, P = 0.830) groups.

The mean scores of all six domains of POMS showed a reduction from baseline to week 6 and then week 12 in the Physta® 100 mg group compared with the other groups. The percentage of mean score changes observed at week 12 compared with baseline for the Physta® 100 mg group showed a reduction in tension (-21.7%), depression (-31.9%), anger (-13.8%), fatigue (-36.9%), and confusion (-20.5%), and vigor increased by 5.7% (Figure 3). Moreover, all domains of Physta® 50 mg showed a reduction in the percentage of changes of mean scores at week 12 compared with baseline in tension (-10.9%), depression (-5.4%), anger (-9.9%), fatigue (-31.6%), and confusion (-9.8%), and vigor increased by 1.2%. These percentage changes of Physta® 50 mg were less than those of Physta® 100 mg. Furthermore, the placebo group showed a reduction in percentage for vigor (-22.7%) while increasing in the Physta® 100 mg (5.7%) and Physta® 50 mg (1.2%) groups. Within-group effects showed a significant reduction in fatigue mean score for all groups, indicating reduced fatigue among participants over the 12-week study [placebo (P = 0.003), Physta® 100 mg (P = 0.001) and Physta® 50 mg (P = 0.019)].

Table 3 shows a summary of symptoms reported during the study period. No serious adverse events occurred during the study. At the week 6 follow-up, some participants reported temporary symptoms like bloating, headache, breast tenderness, flatulence, and abdominal discomfort experienced initially when taking the study supplements. These issues were reported as resolved on their own without any treatment after a couple of weeks of consumption. None of the adverse events were recorded as “related” to the investigational products. Hence, no participants needed medical treatment or hospitalization during the study period.

| Adverse event | Placebo (n = 40) | Physta® 50 mg (n = 36) | Physta® 100 mg (n = 36) | Total (n = 112) | Severity | Outcome | Related to product |

| Bloating | 2 (5.0) | 3 (8.3) | 4 (11.1) | 9 (8.0) | Mild | Resolved | No |

| Headache | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5.6) | 2 (5.6) | 5 (4.5) | Mild | Resolved | No |

| Breast tenderness | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.8) | 2 (5.6) | 3 (2.7) | Mild | Resolved | No |

| Flatulence | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5.6) | 2 (5.6) | 5 (4.5) | Mild | Resolved | No |

| Abdominal discomfort | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.8) | 2 (5.6) | 4 (3.6) | Mild | Resolved | No |

| Total events | 5 (12.5) | 9 (25.0) | 12 (33.3) | 26 (23.2) | - | - | - |

To the best of our knowledge, no RCT has been conducted to date to assess the efficacy of EL as a single herbal preparation in treating menopausal symptoms. A previous RCT using the herbal formulation Nu-femme™, comprising Labisia pumila and EL, demonstrated improving trends in mitigating the severity of hot flush as well as hormone and lipid profiles, bone health markers, sleep, and vitality parameters in healthy perimenopausal and postmenopausal females compared with placebo, though achieving limited statistical significance. This is due to confounding factors and a high placebo effect usually common in menopausal studies[21]. Moreover, the usage of two different dosages of Physta® in this study can add research evidence for the dosage-dependent efficacy of EL in improving menopausal symptoms and pave the way for alternative treatment opportunities.

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study was the first three-armed study conducted to date to evaluate the efficacy of Physta® on MENQOL and mood states of menopausal females along with the safety biochemical parameters and reproductive hormone profiling. Although there was no statistical significance when comparing mean scores at week 6 or week 12 of intervention, reductions in the total mean score of MENQOL (decreased symptoms of menopause) at each visit compared with baseline subsequently showed a trend of improved QOL among participants by the end of the study. Notably, this decrease was statistically significant in the Physta® groups compared with the placebo group, especially the reduction of mean scores of the Physta® 100 mg group from baseline to week 12 in the total MENQOL scores (P = 0.049), physical domain (P = 0.046), and sexual domain (P = 0.043) compared with placebo (Figure 2).

While all groups generally showed improvements in MENQOL scores, including a 23.3% reduction in the placebo group, our findings suggested that the observed effects in the Physta® 100 mg group meaningfully exceeded the placebo response. The Physta® 100 mg group achieved a 33.9% significant reduction in total MENQOL score and statistically significant improvements in the physical (P = 0.046) and sexual (P = 0.043) domains compared with placebo. These differences indicate a potential actual treatment effect beyond expectation or placebo influence.

The pronounced improvements in mood domains and overall symptom reduction in the Physta® 100 mg group reinforce its therapeutic potential. Although the decrease in total MENQOL scores with 100 mg Physta® reached statistical significance, the power analysis (0.516) indicated low statistical power. This reduces confidence in the stability of this finding and highlights the need for replication with larger sample sizes to confirm the observed effect. Hence, it underscores the importance of larger sample sizes, longer follow-up durations, and inclusion of objective biomarkers in future trials to further differentiate specific treatment efficacy.

Several previous RCTs on elucidating EL supplementation as a potential adaptogen demonstrated improvement in serum total testosterone levels, proving this medicinal herb in boosting sexual and physical health[16,17]. As EL contains a wide range of bioactive phytochemicals, particularly in its roots, such as quassinoids like eurycomanone, other compounds such as eurycomalactone, tirucallane-type triterpenes and peptides[19-28]. Among these, eurycomanone and a 4.3 kDa peptide are the primary phytochemicals in standardized extracts like Physta®. They influence testosterone regulation, reduce cortisol, and exert adaptogenic and anti-inflammatory effects[27,28]. These mechanisms may underlie the improvements observed in the sexual and physical domains of MENQOL, particularly in the Physta® 100 mg group.

The analysis of the POMS questionnaire has demonstrated that all three groups, Physta® 100 mg, 50 mg, and placebo, showed reductions in the total mood disturbance score of POMS. The percentage of reduction in total mood disturbance scores was displayed more evidently in the Physta® 100 mg group compared with Physta® 50 mg and placebo (Figure 3). Simultaneously, POMS scores for all domains showed a greater percentage of score reduction among participants in the Physta® 100 mg group compared with placebo. Compared with a decrease in placebo, an improved trend in the POMS-vigor domain was observed in the Physta® 100 mg and Physta® 50 mg groups.

Between the placebo and Physta® 50 mg, some mood parameters showed mixed trends that could be due to the placebo effect. Similarly, in an RCT of Physta® water extract plus multivitamins on QOL, mood, and stress among moderately stressed individuals, a large placebo effect was reported in POMS total mood disturbance, resulting in the absence of significance in the between-group difference[22]. This may be due to the lower dose of EL (50 mg/day) employed in a small population size, similar to this study of the Physta® 50 mg group. This is in contrast with the clinical benefits attained with a higher dose (200 mg/day) used in a previous human trial conducted in the United States to study the stress relief ability of EL among moderately stressed participants[29]. Intake of Physta® at 200 mg/day for 4 weeks has shown significant improvements in tension, anger, and confusion with EL supplementation.

Notably, the maximum dosage used in this study (100 mg) is half of the dosage used in the previous trial (200 mg). The current study dosage was an initial investigation to assess tolerability and efficacy at moderate doses. The population of the previous study involved moderately stressed participants, which differed from the population of our research. Therefore, it was postulated that the dosage optimization and characteristics of study participants could have been the reasons for the insignificant group and time interaction results of the mood states of menopausal females in current study.

The effect of a placebo on decreasing the symptoms of menopause and consequently improving QOL has also been reported elsewhere[24,25]. The placebo effect amplified in a smaller population may have obscured the statistically significant efficacy of lower dosage Physta® in improving MENQOL and mood states of females. We intentionally limited this trial to 50 mg and 100 mg doses as initial safety and efficacy assessments in a menopausal cohort. Higher doses were not included to minimize potential safety concerns in a new population. Future trials should investigate 200 mg to determine whether higher doses produce larger effect sizes without compromising safety.

Apart from its efficacy in elevating the QOL and mood state of menopausal females, the safety aspect of Physta® consumption was also unveiled through this study. The self-reported medical history of participants at baseline showed that the majority of them were predominantly healthy without any non-communicable diseases like cardiovascular diseases, thyroid disorders, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, autoimmune conditions, or cancer. Stringent exclusion criteria ensured that the study only included females with stable medical conditions. This justified the baseline biochemical characteristics that showed that almost all blood parameters fell within identical ranges across all the study groups, with no statistically significant differences. The 12-week Physta® intervention displayed no significant abnormality on vital signs such as blood pressure and pulse rate, indicating that Physta® is well-tolerated (Table 4). Similarly, stable metabolic, liver enzymes (alanine transaminase, gamma-glutamyl transferase), renal function, and kidney function parameters were all within the normal ranges, indicating that Physta® does not exert adverse effects on metabolic, hepatic, or renal function after 12 weeks of consumption. The safety and tolerability of EL are consistent with previous clinical studies reported[16,17,23,24]. This comprehensive 12-week follow-up on the safety parameters further established the safety in using and consumption of Physta® as a dietary supplement.

| Parameter | Placebo (n = 40) | Physta® 50 mg (n = 36) | Physta® 100 mg (n = 36) | ||||||

| Baseline | Week 6 | Week 12 | Baseline | Week 6 | Week 12 | Baseline | Week 6 | Week 12 | |

| Anthropometry | |||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.35 ± 2.59 | 26.77 ± 2.92 | 26.91 ± 3.12a | 26.05 ± 2.95 | 26.48 ± 3.29 | 26.49 ± 3.20 a | 26.71 ± 2.71 | 27.00 ± 2.81 | 26.93 ± 2.73a |

| Height (cm) | 157.25 ± 4.85 | 157.22 ± 4.93 | 157.14 ± 4.92 | 155.74 ± 6.27 | 155.30 ± 6.30 | 155.65 ± 6.25 | 156.20 ± 4.96 | 156.00 ± 4.95 | 156.10 ± 5.05 |

| Weight (kg) | 65.33 ± 8.62 | 66.35 ± 9.41 | 66.66 ± 9.91a | 63.29 ± 9.09 | 63.94 ± 9.40 | 64.31 ± 9.60 a | 65.24 ± 7.94 | 65.78 ± 8.07 | 65.67 ± 7.69a |

| Vitals and safety | |||||||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 123.80 ± 16.33 | 120.02 ± 15.85 | 122.98 ± 14.43 | 121.53 ± 13.38 | 121.19 ± 14.34 | 121.47 ± 12.39 | 126.36 ± 11.47 | 124.72 ± 14.70 | 123.11 ± 12.59 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 79.83 ± 9.11 | 76.85 ± 8.82 | 77.90 ± 9.12a | 80.44 ± 11.27 | 78.47 ± 9.11 | 79.92 ± 9.40a | 82.53 ± 7.86 | 79.03 ± 8.94 | 79.00 ± 10.15a |

| Pulse rate | 73.73 ± 10.09 | 74.75 ± 12.15 | 77.90 ± 12.60 | 74.53 ± 7.17 | 71.75 ± 11.95 | 72.50 ± 7.88 | 72.78 ± 7.08 | 72.58 ± 7.66 | 73.58 ± 9.86 |

| Urea | 3.66 ± 0.84 | 3.68 ± 0.99 | 3.60 ± 0.81 | 3.68 ± 0.71 | 3.60 ± 0.79 | 3.73 ± 0.82 | 3.56 ± 1.01 | 3.56 ± 0.77 | 3.43 ± 0.85 |

| Creatinine | 65.08 ± 11.70 | 64.26 ± 12.52 | 66.05 ± 13.00 | 60.06 ± 8.22 | 62.03 ± 10.84 | 59.17 ± 10.02 | 58.94 ± 12.30 | 61.83 ± 13.22 | 59.89 ± 13.32 |

| eGFR | 99.24 ± 14.35 | 100.13 ± 14.03 | 98.76 ± 14.83 | 104.43 ± 8.57 | 101.86 ± 11.74 | 105.51 ± 9.79 | 105.86 ± 12.62 | 101.75 ± 14.45 | 104.58 ± 13.09 |

| Uric acid | 0.30 ± 0.06 | 0.30 ± 0.06 | 0.30 ± 0.05 | 0.29 ± 0.05 | 0.28 ± 0.06 | 0.28 ± 0.06 | 0.28 ± 0.06 | 0.29 ± 0.06 | 0.28 ± 0.07 |

| Calcium | 2.27 ± 0.08 | 2.25 ± 0.08 | 2.26 ± 0.08 | 2.32 ± 0.08 | 2.29 ± 0.11 | 2.27 ± 0.08 | 2.29 ± 0.08 | 2.27 ± 0.08 | 2.24 ± 0.09 |

| Phosphate | 1.11 ± 0.18 | 1.13 ± 0.16 | 1.25 ± 0.43 | 1.15 ± 0.17 | 1.16 ± 0.16 | 1.28 ± 0.52 | 1.08 ± 0.17 | 1.10 ± 0.15 | 1.18 ± 0.46 |

| Total protein | 75.40 ± 3.66 | 74.84 ± 2.63 | 74.71 ± 3.25 | 75.54 ± 4.08 | 74.26 ± 3.24 | 73.40 ± 3.04 | 75.78 ± 3.80 | 74.92 ± 3.57 | 73.97 ± 3.60 |

| Albumin | 44.53 ± 2.62 | 43.90 ± 2.35 | 44.21 ± 1.71 | 44.94 ± 2.30 | 44.80 ± 2.90 | 44.49 ± 2.25 | 44.78 ± 1.88 | 44.92 ± 2.43 | 44.81 ± 2.41 |

| Globulin | 30.87 ± 3.32 | 30.95 ± 3.11 | 30.50 ± 2.76 | 30.60 ± 3.30 | 29.46 ± 3.33 | 28.91 ± 2.76 | 31.00 ± 2.87 | 30.00 ± 3.63 | 29.17 ± 2.97 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 77.26 ± 26.84 | 78.82 ± 48.10 | 74.50 ± 19.22 | 73.63 ± 18.26 | 70.83 ± 17.94 | 72.06 ± 20.16 | 68.22 ± 12.74 | 66.11 ± 12.39 | 67.42 ± 14.98 |

| Total bilirubin | 8.58 ± 2.84 | 8.58 ± 2.33 | 8.71 ± 3.15 | 9.83 ± 4.59 | 9.66 ± 5.14 | 9.91 ± 4.33 | 8.97 ± 3.38 | 9.03 ± 3.44 | 8.39 ± 2.98 |

| GGT | 34.74 ± 36.10 | 34.84 ± 44.10 | 33.90 ± 27.06 | 25.77 ± 15.65 | 24.80 ± 17.52 | 24.94 ± 14.72 | 27.64 ± 25.97 | 24.06 ± 18.53 | 25.56 ± 28.09 |

| ALT | 26.32 ± 32.76 | 27.50 ± 45.75 | 22.03 ± 15.88 | 18.89 ± 15.45 | 18.06 ± 14.55 | 19.57 ± 12.61 | 19.78 ± 14.29 | 19.42 ± 13.90 | 19.39 ± 13.26 |

| C-Reactive Protein | 3.58 ± 2.84 | 3.07 ± 2.23 | 4.05 ± 3.77 | 2.37 ± 2.11 | 2.92 ± 3.37 | 3.09 ± 3.33 | 2.71 ± 2.13 | 2.38 ± 1.71 | 3.65 ± 3.81 |

| Total cholesterol | 5.72 ± 1.26 | 5.78 ± 1.10 | 5.73 ± 1.07 | 5.77 ± 0.93 | 5.47 ± 0.82 | 5.43 ± 0.81 | 5.60 ± 0.75 | 5.60 ± 0.77 | 5.59 ± 0.84 |

| Triglyceride | 1.32 ± 1.02 | 1.22 ± 0.77 | 1.32 ± 0.99 | 1.05 ± 0.38 | 1.35 ± 1.59 | 0.98 ± 0.32 | 1.15 ± 0.49 | 1.09 ± 0.59 | 1.16 ± 0.52 |

| HDL cholesterol | 1.61 ± 0.41 | 1.58 ± 0.36 | 1.63 ± 0.41 | 1.68 ± 0.35 | 1.61 ± 0.33 | 1.64 ± 0.32 | 1.68 ± 0.42 | 1.61 ± 0.34 | 1.60 ± 0.32 |

| LDL cholesterol | 3.58 ± 1.03 | 3.63 ± 1.08 | 3.48 ± 1.07 | 3.61 ± 0.96 | 3.37 ± 0.80 | 3.33 ± 0.85 | 3.40 ± 0.73 | 3.49 ± 0.72 | 3.46 ± 0.85 |

| Non-HDL cholesterol | 4.11 ± 1.14 | 4.19 ± 1.06 | 4.10 ± 1.05 | 4.09 ± 1.06 | 3.86 ± 0.88 | 3.78 ± 0.91 | 3.93 ± 0.79 | 3.99 ± 0.82 | 3.99 ± 0.93 |

| Total cholesterol/HDL | 3.73 ± 1.10 | 3.80 ± 1.00 | 3.71 ± 1.10 | 3.60 ± 1.06 | 3.55 ± 0.93 | 3.45 ± 0.98 | 3.53 ± 0.89 | 3.61 ± 0.89 | 3.63 ± 0.93 |

| Hormone profile | |||||||||

| Progesterone | 15.47 ± 10.11 | 12.95 ± 10.16 | 15.15 ± 9.23a | 18.21 ± 11.80 | 20.09 ± 12.94 | 16.03 ± 15.47a | 13.33 ± 7.10 | 19.14 ± 11.58b | 19.05 ± 10.50a |

| Serum testosterone | 0.45 ± 0.27 | 0.49 ± 0.30 | 0.51 ± 0.36 | 0.67 ± 0.54 | 0.65 ± 0.46 | 0.64 ± 0.48 | 0.61 ± 0.35 | 0.69 ± 0.36 | 0.57 ± 0.34 |

| Follicle stimulating hormone | 25.66 ± 27.96 | 22.18 ± 26.13 | 22.91 ± 26.52 | 35.18 ± 34.78 | 35.25 ± 35.52 | 30.87 ± 32.03 | 30.13 ± 30.14 | 29.89 ± 31.10 | 28.39 ± 32.47 |

| Luteinizing hormone | 15.06 ± 15.29 | 16.28 ± 18.04 | 18.79 ± 21.44 | 25.16 ± 20.66 | 24.68 ± 23.19 | 22.71 ± 20.24 | 20.17 ± 17.03 | 22.48 ± 16.68 | 18.93 ± 15.99 |

| Estradiol | 357.39 ± 472.23 | 433.14 ± 388.06 | 424.91 ± 279.29 | 435.48 ± 392.41 | 323.45 ± 312.32 | 470.97 ± 565.94 | 328.50 ± 331.87 | 546.54 ± 622.99 | 385.71 ± 401.61 |

Furthermore, this study was primarily exclusive in determining the effectiveness of Physta® on the female reproductive hormone profile among menopausal females. A drastic shift in reproductive hormonal balance happens during the perimenopause phase. During this inevitable transitional phase, the estrogen levels decrease as the FSH and LH hormones increase to promote a decline in progesterone levels[30] eventually. These hormonal changes cumulatively cause permanent cessation of menstruation or menopause. The female reproductive hormone profile assessed in this study included progesterone, testosterone, estradiol, FSH, and LH. These hormones were selected to reflect the hormonal functional status of females during the menopausal transition. These reproductive hormones were collected to determine whether EL (Physta®) supplementation had any modulatory effects on reproductive hormones.

Testosterone was measured in this study to assess the potential androgenic effects of EL in females. Testosterone plays key roles in female sexual function, mood, and vitality[31]. As it decreases during menopause, evaluating testosterone helps determine whether Physta® may support these functions through neuroendocrine modulation. In this study, the female reproductive hormone profiling revealed no significant changes in hormone levels across the study groups from baseline to week 12. A statistically significant group effect was noted for progesterone at week 6 (P = 0.026) with a transient increase observed in the Physta® 100 mg group compared with placebo (P = 0.022). However, this effect was not sustained at week 12 (P = 0.076), and no significant changes were observed in the 50 mg group. The transient increase in progesterone in the 100 mg group may be biologically plausible, potentially reflecting the adaptogenic and hormone-modulating effects of EL[15,16].

The inclusion of perimenopausal females, whose menstrual cycles are often irregular and hormonally unstable, raises the possibility of unmeasured confounding factors. Natural fluctuations in progesterone due to undetected ovulation or varying cycle phases could have influenced this transient rise, particularly with 77% of the females still in a premenopausal and perimenopausal status with irregular menstruation. Future studies should incorporate menstrual cycle tracking or stratify analyses by menopausal status to minimize this confounding effect and clarify any hormonal mechanisms. While this study focused on total hormone concentrations, future research may incorporate free hormone indices and sex hormone-binding globulin to accurately measure bioavailable hormone modulation and activity.

The limitation of this study was that the study sampling was performed only in a few locations around Klang Valley (an urbanized city dwelling). This area may not inclusively represent the entire population of females. Moreover, the vast majority of participants were Malay (96%). This contradicts the Malaysian ethnic composition that comprises 67.4% Malays and Bumiputera, 24.6% Chinese, 7.3% Indians, and 0.7% others[32]. Hence, the findings of this study do not directly represent Malaysia’s ethnic distribution, and the cultural and ethnic factors may influence how menopausal symptoms are perceived, reported, and managed, potentially affecting the response to Physta®. Future studies should include more diverse ethnic groups to understand these variations better.

Additionally, the observed placebo effect, a common feature in RCT studies, may have masked the real impact of Physta® on the mood and QOL of menopausal females in this study. A recent meta-analysis article on the factors associated with high placebo response in clinical studies of females with hot flashes identified three main individual factors with high placebo response, including the treatment period duration, number of treatment arms, and participants’ BMI[33]. As our study was a three-arm study with BMI ranging from normal (18 to 24.9 kg/m2) to overweight (25 to 29.9 kg/m2) with a study duration of only 12 weeks, the placebo effect is fairly possible.

Nevertheless, the physical activity and level of exercise among participants could contribute to the placebo effect observed in clinical studies. A review in Sports Medicine found that placebo interventions could enhance sports and exercise performance, suggesting that participants’ beliefs and behaviors significantly impact outcomes[34]. Similarly, a balanced diet rich in essential nutrients, such as fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and whole grains, may independently improve physical health and mental well-being[35]. Variations in total caloric intake, whether through reduced consumption or improved nutritional quality, can also positively influence metabolic health and QOL, further enhancing the placebo effect[36].

To deeply understand the potential of EL as a therapeutic herbal dietary supplement in alleviating menopausal symptoms, future studies shall include a broad number of parameters, such as confounding lifestyle factors, such as diet, food intake, physical activity and stress levels, female hormone profile, and inflammatory biomarkers. Moreover, a higher dose of Physta® supplementation with a more extended intervention period and larger sample sizes would offer a more comprehensive evaluation to assess the efficacy of EL in managing menopausal symptoms along with both subjective (questionnaires) and objective (hormone and biomarker) measures. These strategies can indirectly contribute to scientific research on tropical herbs as an alternative therapeutic option to ease menopausal symptom severity and improve the menopausal QOL of middle-aged females.

Although menopause is an inevitable biological transition in every female’s life, it can be eased by reducing the bothersome menopausal symptoms. The present research has provided a prior understanding of the potential of Physta® as a dietary supplement to alleviate menopausal symptoms. Physta® was well-tolerated in the study population and did not adversely affect liver or renal function after 12 weeks of consumption. Additionally, the study found no serious adverse events associated with Physta® throughout the study period, indicating the safety of Physta® for consumption among females as a daily dietary supplement. The results of female reproductive hormones deduced that no significant changes were attributable to Physta®. Comparing the two dosages of Physta® (50 mg and 100 mg) in the study, results showed that Physta® 100 mg improved the menopausal QOL, especially the physical and sexual function in 12 weeks. While short-term improvements were evident, extended studies are necessary to assess the sustained benefits and potential long-term side effects. To achieve a comprehensive understanding of the benefits of Physta®, the underlying biochemical pathways and mechanisms responsible for the functionality of Physta® should be studied in depth in the future.

We thank all the authors for contributing their time, ideas, and suggestions in designing the study. We thank all our study participants for their commitment towards the study.

| 1. | Smail L, Jassim G, Shakil A. Menopause-Specific Quality of Life among Emirati Women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;17:40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Adhikari B, Biswas R. Quality of life among menopausal women in an urban area of Siliguri, West Bengal, India. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2019;6:4964. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Geraghty P. History and Overview of the Menopause Experience. Each Woman’s Menopause: An Evidence Based Resource. Cham: Springer, 2022: 3-28. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Whiteley J, DiBonaventura Md, Wagner JS, Alvir J, Shah S. The impact of menopausal symptoms on quality of life, productivity, and economic outcomes. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013;22:983-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rathnayake N, Lenora J, Alwis G, Lekamwasam S. Prevalence and Severity of Menopausal Symptoms and the Quality of Life in Middle-aged Women: A Study from Sri Lanka. Nurs Res Pract. 2019;2019:2081507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ray S, Dasgupta A. An assessment of QOL and its determining factors of postmenopausal women in a rural area of West Bengal, India: A multivariate analysis. Int J Med Public Health. 2012;2:12-19. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ibrahim ZM, Ghoneim HM, Madny EH, Kishk EA, Lotfy M, Bahaa A, Taha OT, Aboelroose AA, Atwa KA, Abbas AM, Mohamed ASI. The effect of menopausal symptoms on the quality of life among postmenopausal Egyptian women. Climacteric. 2020;23:9-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Loutfy I, Abdel Aziz F, Dabbous NI, Hassan MH. Women's perception and experience of menopause: a community-based study in Alexandria, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2006;12 Suppl 2:S93-106. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Zhang GQ, Chen JL, Luo Y, Mathur MB, Anagnostis P, Nurmatov U, Talibov M, Zhang J, Hawrylowicz CM, Lumsden MA, Critchley H, Sheikh A, Lundbäck B, Lässer C, Kankaanranta H, Lee SH, Nwaru BI. Menopausal hormone therapy and women's health: An umbrella review. PLoS Med. 2021;18:e1003731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kenda M, Glavač NK, Nagy M, Sollner Dolenc M, On Behalf Of The Oemonom. Herbal Products Used in Menopause and for Gynecological Disorders. Molecules. 2021;26:7421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Manipriya K, Mallika DBL, Dixit AS, Goud UK. Promising Herbs as Alternatives for Women with Symptoms of Menopause: A Review. J Drug Vigil Alterna Ther. 2021;01:46-64. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Mehrnoush V, Darsareh F, Roozbeh N, Ziraeie A. Efficacy of the Complementary and Alternative Therapies for the Management of Psychological Symptoms of Menopause: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Menopausal Med. 2021;27:115-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Park EJ, Baek SE, Kim M, Kim AR, Park HJ, Kwon O, Lee JH, Yoo JE. Effects of herbal medicine (Danggwijagyaksan) for treating climacteric syndrome with a blood-deficiency-dominant pattern: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial. Integr Med Res. 2021;10:100715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vejayan J, Mohamed AN, Zulkifli AA, Yahya YAC, Munir N, Yusoff MM. Marker to Authenticate <i>Eurycoma Longifolia</i> (Tongkat Ali) Containing Aphrodisiac Herbal Products. Curr Sci. 2018;115:886. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Talbott SM. Human Performance and Sports Applications of Tongkat Ali (Eurycoma longifolia). Nutrition and Enhanced Sports Performance. San Diego: Academic Press, 2013: 501-505. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Leisegang K, Finelli R, Sikka SC, Panner Selvam MK. Eurycoma longifolia (Jack) Improves Serum Total Testosterone in Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58:1047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Leitão AE, Vieira MCS, Pelegrini A, da Silva EL, Guimarães ACA. A 6-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial to evaluate the effect of Eurycoma longifolia (Tongkat Ali) and concurrent training on erectile function and testosterone levels in androgen deficiency of aging males (ADAM). Maturitas. 2021;145:78-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bhat R, Karim AA. Tongkat Ali (Eurycoma longifolia Jack): a review on its ethnobotany and pharmacological importance. Fitoterapia. 2010;81:669-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Farag MA, Ajayi AO, Taleb M, Wang K, Ayoub IM. A Multifaceted Review of Eurycoma longifolia Nutraceutical Bioactives: Production, Extraction, and Analysis in Drugs and Biofluids. ACS Omega. 2023;8:1838-1850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mohd Effendy N, Mohamed N, Muhammad N, Naina Mohamad I, Shuid AN. Eurycoma longifolia: Medicinal Plant in the Prevention and Treatment of Male Osteoporosis due to Androgen Deficiency. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:125761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | M Chinnappan S, George A, Ashok G, Choudhary YK. Effect of herbal extract Eurycoma longifolia (Physta(®)) on female reproductive hormones and bone biochemical markers: an ovariectomised rat model study. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020;20:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Thu HE, Mohamed IN, Hussain Z, Jayusman PA, Shuid AN. Eurycoma Longifolia as a potential adoptogen of male sexual health: a systematic review on clinical studies. Chin J Nat Med. 2017;15:71-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Talbott SM. Human Performance and Sports Applications of Tongkat Ali (Eurycoma longifolia). Nutrition and Enhanced Sports Performance. Academic Press, 2019: 729-734. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Varghese CP, C A, Jin SC, Lim YJ, Keisaban T. Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Activity of Eurycoma Longifolia Jack, A Traditional Medicinal Plant in Malaysia. PCI- Approved-IJPSN. 2013;5:1875-1878. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26400] [Cited by in RCA: 37773] [Article Influence: 1988.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Muniandy S, Yahya HM, Shahar S, Kamisan Atan I, Mahdy ZA, Rajab NF, George A, Chinnappan SM. Effects of Eurycoma longifolia Jack standardised water extract (Physta) on well-being of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: protocol for a randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, parallel group study. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e073323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Segaran A, Chua LS, Mohd Ismail NI. A narrative review on pharmacological significance of Eurycoma longifolia jack roots. Longhua Chin Med. 2021;4:35-35. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Sambandan TG, Rha CK, Kadir AA, Aminudim N, Saad J, Mohammed M. Bioactive fraction of Eurycoma longifolia. United States Patent. 2006;7132117 B2. |

| 29. | Talbott SM, Talbott JA, George A, Pugh M. Effect of Tongkat Ali on stress hormones and psychological mood state in moderately stressed subjects. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2013;10:28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ogbuagu EO, Airaodion AI, Uche CL, Ogbuagu U, Ezirim EO, Nweke IN, Unekwe PC. Alterations in Female Reproductive Hormones of Wistar Rats Sequel to the Administration of Xylopia aethiopica Fruit. Asian Res J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;7:47-57. |

| 31. | Chinnappan SM, George A, Pandey P, Narke G, Choudhary YK. Effect of Eurycoma longifolia standardised aqueous root extract-Physta(®) on testosterone levels and quality of life in ageing male subjects: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre study. Food Nutr Res. 2021;65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Chai ST, Hamid D, Aizan T. Population ageing and the Malaysian Chinese: Issues and challenges. Malaysia J Chinese Studies. 2024;4:1. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Miyazaki K, Kaneko M, Narukawa M. Factors associated with high placebo response in clinical studies of hot flashes: a meta-analysis. Menopause. 2021;29:239-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chhabra B, Szabo A. Placebo and Nocebo Effects on Sports and Exercise Performance: A Systematic Literature Review Update. Nutrients. 2024;16:1975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Głąbska D, Guzek D, Groele B, Gutkowska K. Fruit and Vegetable Intake and Mental Health in Adults: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2020;12:115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 43.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Most J, Redman LM. Impact of calorie restriction on energy metabolism in humans. Exp Gerontol. 2020;133:110875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/