Published online Nov 6, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i31.109584

Revised: June 28, 2025

Accepted: August 22, 2025

Published online: November 6, 2025

Processing time: 168 Days and 2.1 Hours

Lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis, with nil or minor nasal extensions, rarely presents as an acquired cutaneous fistula in the periocular area. The correct diagnosis in such cases can be challenging, leading to repeated failure of conservative or surgical interventions.

A 39-year-old female presented with a 6-year history of swelling in the periocular area, specifically in the left lacrimal sac area. Symptoms were limited to epiphora and constant mucoid discharge from the fistula, clinically mimicking chronic lacrimal sac fistula. She had a history of treatment with multiple antibiotic courses and dacryocystectomy in the past, with no or transient symptomatic relief. On surgical exploration of the site, a large pedunculated polypoidal vascular mass, suspicious of rhinosporidiosis, was noted. En bloc resection of the mass with cauterization of the base and fistulectomy was performed. Histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis. The patient was further evaluated and treated for the nasal extension of rhinosporidiosis. The patient has been frequently followed up for the last 3 years with a good clinical outcome and no recurrence.

Lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis, in isolated or limited nasal extension cases, can rarely mimic a chronic discharging fistula. Patients with this disease often face distress due to misdiagnosis and repeated failure of conservative or surgical interventions. A high index of suspicion is needed for early diagnosis. Proper surgical intervention at the right time can lead to an excellent prognosis in such patients.

Core Tip: Lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis can rarely present as a chronic discharging fistula. We report the case of a 39-year-old female with a 6-year history of epiphora and mucoid discharge from a left lacrimal sac fistula, clinically mimicking chronic dacryocystitis. Surgical exploration revealed a large pedunculated vascular mass, which was confirmed on histopathology as lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis. She was treated for nasal extension, remaining recurrence-free over 3 years of follow-up. This case highlights the importance of keeping rhinosporidiosis as a differential for any patient with lacrimal sac area swelling, with or without discharging fistula.

- Citation: Panda BB, Kar A, Koppalu Lingaraju T, Ayyanar P. Acquired cutaneous fistula in the periocular area: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(31): 109584

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i31/109584.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i31.109584

Rhinosporidiosis is a chronic granulomatous disease caused by an aquatic protistan parasite, Rhinosporidium seeberi[1]. The disease has high endemicity in certain Southeast Asian countries, including India[2]. This parasite most commonly infects the mucosa of the nose and nasopharynx, acquired through contaminated stagnant water[2,3]. The most common site for ocular infestation is the conjunctiva, followed by the lacrimal sac[4,5]. Lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis is commonly an extension of nasal infection by the parasite. However, in rare instances of minor nasal involvement or isolated lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis, symptoms may only be ocular, mimicking chronic dacryocystitis or even a chronic discharging lacrimal sac fistula.

We report a rare case of lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis presenting as a discharging lacrimal sac fistula, highlighting the diagnostic challenges and the need for a high index of suspicion in endemic areas.

A 39-year-old female from south-eastern India presented to the ophthalmology outpatient clinic with complaints of a swelling below the medial canthus of the left eye for 6 years, along with mucus discharge from the overlying skin opening for the past 7 months.

The swelling was small to start with and gradually increased in size, and was associated with epiphora and discharge from the overlying skin. The discharge was mostly mucoid and occasionally serosanguinous. There was no associated fever, epistaxis, or pain during the recurrent episodes.

The patient was a known diabetic and hypertensive for the past 5 years, on oral medication. She had a history of treatment with multiple courses of topical and systemic antibiotics during the disease course with no symptomatic relief. She had also undergone left-sided dacryocystectomy with fistulectomy 2 years prior, which resulted in a transient decrease in the size of the swelling, but was followed by worsening of symptoms for the last 7 months.

The patient lives in an urban residential area with no history of pond bathing. There have been no complaints of a similar illness among family members.

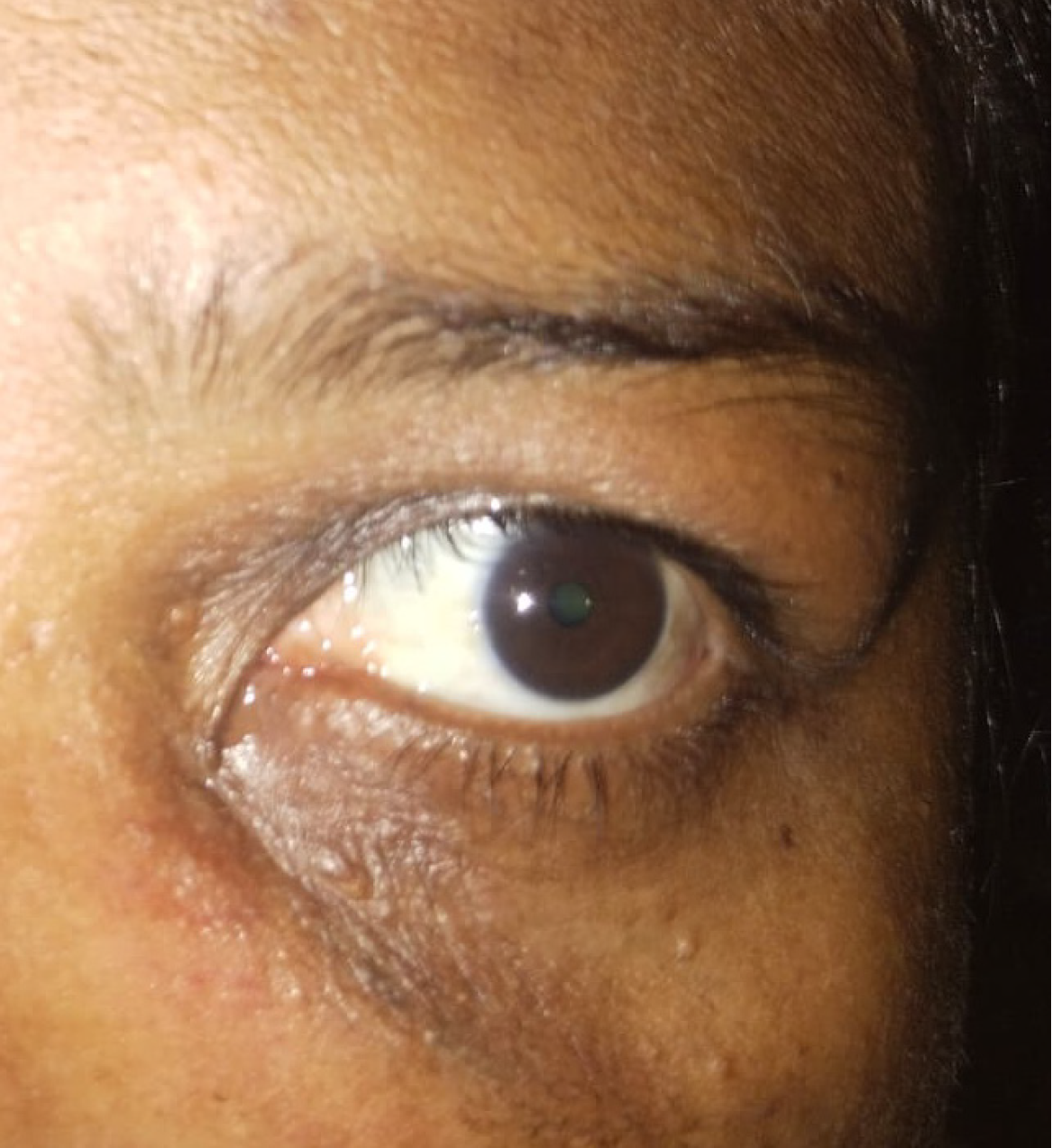

On ocular examination, a diffuse, soft, and non-tender swelling was noted in the medial canthal area, extending below, measuring around 5 cm × 3 cm in greatest dimension. Overlying skin showed puckered appearance along with white comedones (suggestive of chronicity) and a single fistulous opening (Figure 1). Reddish mucoid discharge from the fistula was noted on applying pressure over the mass. On syringing, regurgitation of clear fluid from the upper punctum was noted, while probing showed a soft stop. The best corrected visual acuity in both eyes was 6/6. The rest of the anterior and posterior segments of both eyes were normal.

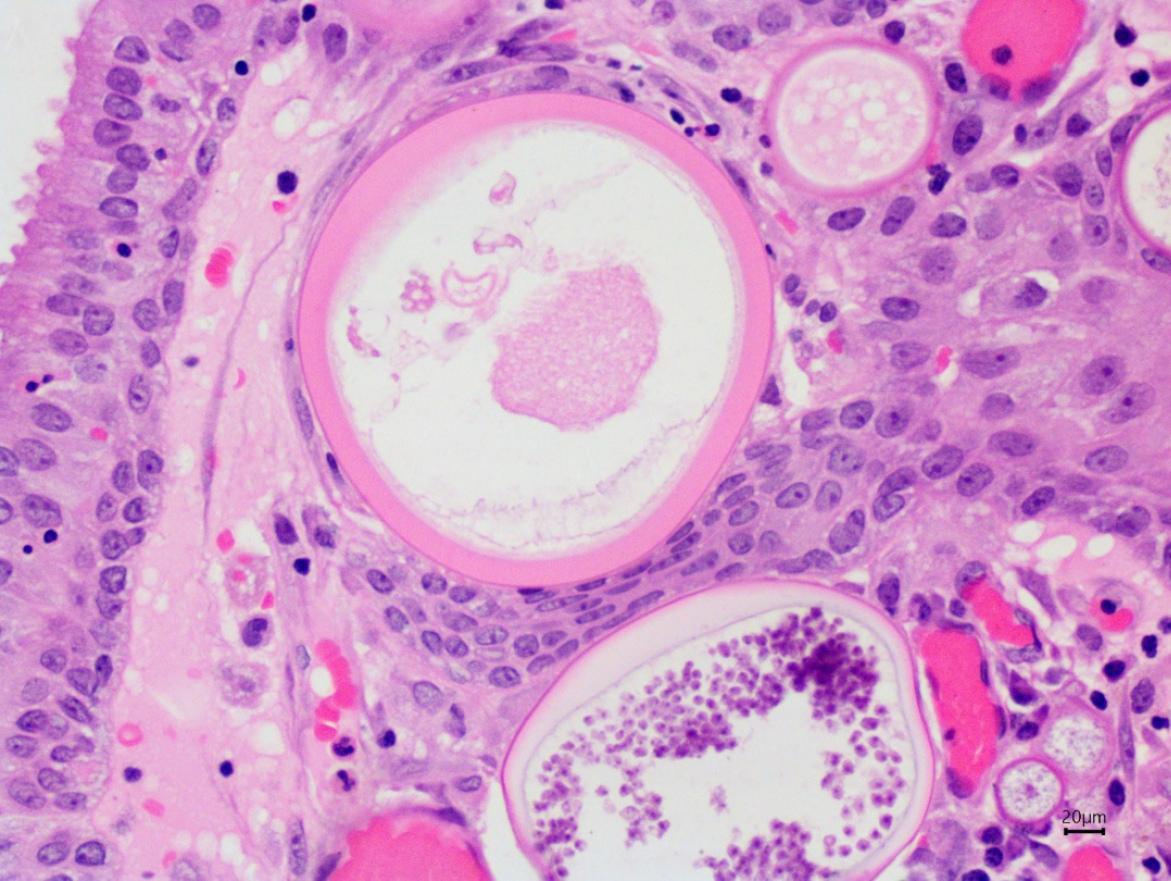

Complete blood count showed mild eosinophilia, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate was mildly elevated, reflecting chronic inflammation. Histopathology showed multiple sporangia of various sizes, with intact or ruptured thick eosinophilic walls. Each sporangium contained many endospores, which were released into the stroma through ruptured walls. Thus, the presence of rhinosporidiosis was confirmed (Figure 2).

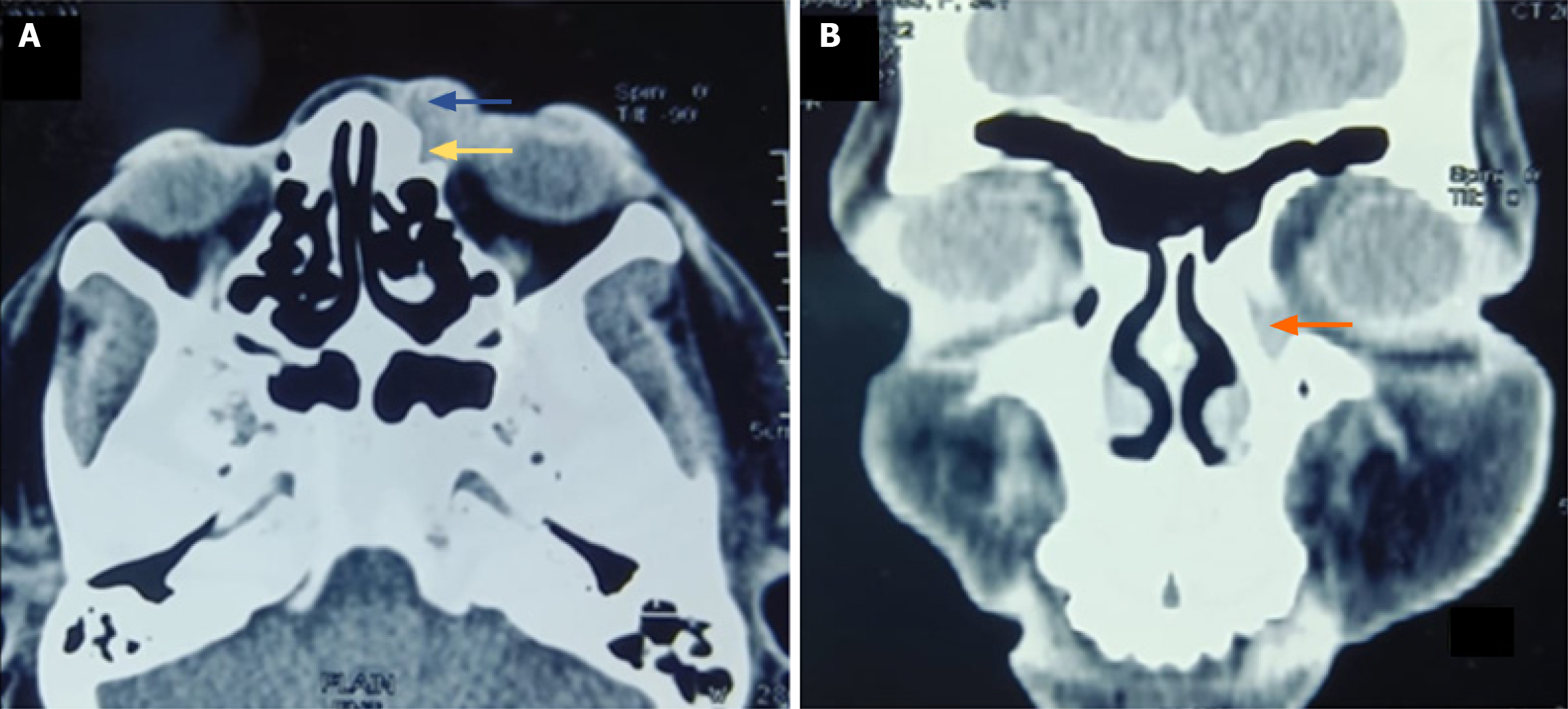

Axial section of computed tomography scan showed an isodense mass lesion within the left inferior aspect of the preseptal compartment, filling the lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct of the left side. There was no orbital extension or bony erosion (Figure 3).

Left-sided chronic discharging lacrimal fistula due to rhinosporidiosis infestation was made.

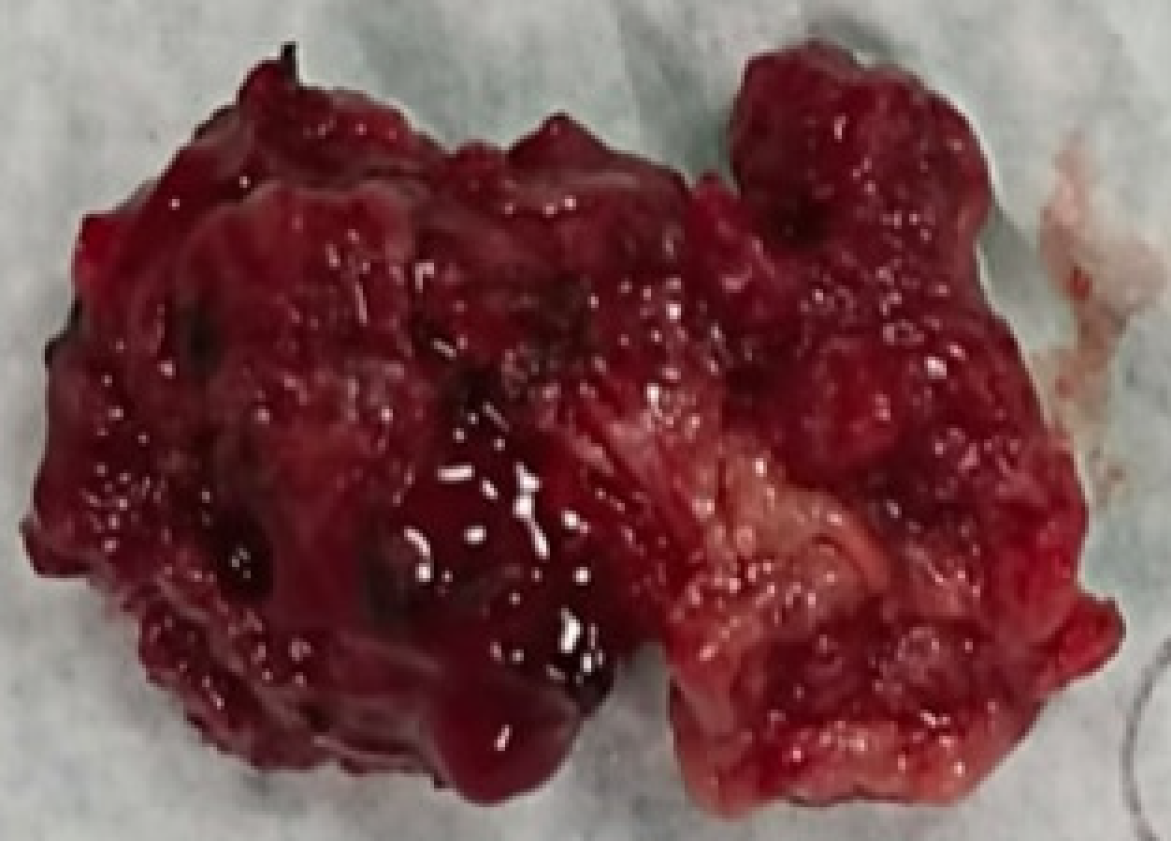

The patient was planned for lacrimal sac area exploration and fistulectomy under local anesthesia. Intraoperatively, the fistula was explored, and a large pedunculated, friable, strawberry-like polypoidal vascular mass, with multiple papillary excrescences, was found in the lacrimal sac area with extension to the nasal cavity through the nasolacrimal duct, suggestive of lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis (Figure 4). During surgical excision, meticulous dissection was performed to avoid rupture of the lesion and spillage of endospores, with en bloc removal of the mass and thorough cauterization of the base to minimize the risk of local contamination and recurrence. Fistulectomy was then performed. The extension to the nasal cavity was cauterized properly, and the rest of the excised mass was sent for histopathological and microbiological examination. The wound was then closed in layers.

Postoperatively, direct nasal endoscopy revealed a pinkish, soft tissue mass at the left inferior meatus that bled on contact. A planned endoscopic excision of the nasal lesion was performed in a second surgical setting under general anesthesia, following confirmation of rhinosporidiosis on histopathology. The procedure involved careful endoscopic visualization and complete excision of the polypoidal mass arising from the lateral wall of the nasal cavity, with meticulous cauterization of the base to minimize the risk of recurrence. Intraoperative findings were consistent with typical features of nasal rhinosporidiosis, and the patient had an uneventful postoperative recovery. The patient has been under regular follow-up for the past 3 years, with an excellent postoperative outcome, namely, complete resolution of the lacrimal sac swelling, absence of fistulous discharge, nasal symptoms, or any evidence of recurrence (Figure 5).

Rhinosporidiosis is a chronic mucocutaneous infection caused by Rhinosporidium seeberi, a protistan parasite within the Mesomycetozoea clade[1,2]. While historically its taxonomic classification oscillated between fungi and parasites, recent genomic studies have definitively placed it closer to aquatic protistan parasites[3,4]. The disease is endemic in South Asia, especially in India, Sri Lanka, and parts of Nepal and Bangladesh, and is associated with exposure to stagnant water bodies[5,6]. Ocular rhinosporidiosis typically involves the conjunctiva, with the lacrimal sac being a relatively less common site. When the lacrimal sac is involved, it is often due to direct extension from the nasal cavity[7]. However, as presented in our case, isolated lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis without significant nasal symptoms is rare and may mimic chronic dacryocystitis or a recurrent lacrimal sac fistula, often leading to misdiagnosis. In the series by Nuruddin et al[8], two patients presented with lacrimal sac fistulas, managed successfully with modified dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) and fistulectomy. The chronicity of the patient’s symptoms, history of failed dacryocystectomy, and presence of a fistula raised suspicion for an underlying persistent pathology. In endemic areas, rhinosporidiosis should be considered in cases of recurrent or atypical dacryocystitis, even in the absence of classical risk factors such as pond bathing or nasal symptoms[4,9]. Our patient’s residence in an urban setting and lack of direct exposure to traditional risk factors, such as pond bathing, suggest that rhinosporidial infection may occur even in the absence of classical environmental exposures. While most cases are associated with rural settings and aquatic exposure, particularly to stagnant water bodies, sporadic urban cases have been documented, possibly reflecting under-recognized transmission pathways. However, the precise environmental reservoirs and transmission dynamics in such atypical settings remain unclear and warrant further investigation[4,6].

Imaging (computed tomography scan) typically reveals a mass in the lacrimal sac or nasolacrimal duct without bony erosion, as seen in our case. However, definitive diagnosis hinges on histopathology, which shows characteristic sporangia containing endospores with thick eosinophilic walls[10]. These findings are pathognomonic and remain the gold standard for diagnosis. Surgical management remains the mainstay of treatment for lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis. The principle is complete en bloc excision of the involved sac and fistulous tract with electrocauterization of the base to reduce the risk of recurrence due to residual spores. Intraoperative care to avoid spillage is critical, as dissemination of endospores can lead to local recurrence. Traditionally, dacryocystectomy has been considered the standard approach due to concerns about residual disease in rhinostomy tracts. However, recent studies have proposed that external DCR, when combined with adequate clearance and cauterization, can be a viable alternative in cases with isolated sac involvement. Bothra et al[11] reported successful outcomes with external DCR in such patients, emphasizing its potential in preserving lacrimal drainage while ensuring disease eradication. Behera et al[10] analyzed a series of lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis cases and emphasized the need for individualized surgical planning based on the extent of disease, advocating for preoperative nasal endoscopy to assess synchronous nasal lesions. Additionally, Rajesh Raju and Sandeep[12] demonstrated that trans nasal endoscopic excision of lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis is feasible and safe, particularly when nasal extension is present, and offers better visualization with minimal morbidity.

In our case, external en bloc excision of the sac and fistulous tract was performed, followed by secondary endoscopic clearance of residual nasal disease. The absence of recurrence over three years of follow-up suggests that a staged surgical approach combining external and endonasal techniques is effective when guided by intraoperative and postoperative endoscopic findings. Despite reports of high recurrence rates (10%-70%) due to incomplete excision or spore dissemination[13], our patient has shown no recurrence over three years of follow-up. This supports the efficacy of meticulous surgical planning and execution. Some reports suggest adjunctive therapy with dapsone (100 mg daily for three months) may help prevent recurrence, but its use remains controversial due to limited evidence and potential toxicity[5,14]. This case adds to the limited literature describing isolated lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis presenting as a chronic discharging fistula, emphasizing the need for a high index of suspicion, especially in recurrent or atypical dacryocystitis in endemic areas. It underscores the importance of histopathological confirmation and highlights the value of a multidisciplinary surgical approach, particularly when nasal or orbital extensions are present.

Lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis can mimic a chronic discharging fistula. Such patients often face distress due to misdiagnosis and repeated failure of conservative or surgical interventions. A high index of suspicion is needed in isolated or limited nasal extension cases for early diagnosis. Histopathology gives a definitive diagnosis. Early diagnosis, timely surgical intervention, and frequent postoperative follow-ups are the key steps for the best prognosis.

| 1. | Arseculeratne SN. Rhinosporidiosis: what is the cause? Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005;18:113-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fredricks DN, Jolley JA, Lepp PW, Kosek JC, Relman DA. Rhinosporidium seeberi: a human pathogen from a novel group of aquatic protistan parasites. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6:273-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Töz S. Rhinosporidium seeberi: Is It a Fungi or Parasite? Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2020;44:258-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Prakash M, Johnny JC. Rhinosporidiosis and the pond. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7:S59-S62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Arias AF, Romero SD, Garcés CG. Case Report: Rhinosporidiosis Literature Review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;104:708-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Karthikeyan P, Vijayasundaram S, Pulimoottil DT. A Retrospective Epidemiological Study of Rhinosporidiosis in a Rural Tertiary Care Centre in Pondicherry. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:MC04-MC08. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shrestha SP, Hennig A, Parija SC. Prevalence of rhinosporidiosis of the eye and its adnexa in Nepal. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:231-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nuruddin M, Mudhar HS, Osmani M, Roy SR. Lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis: clinical profile and surgical management by modified dacryocystorhinostomy. Orbit. 2014;33:29-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Basu SK, Bain J, Maity K, Chattopadhyay D, Baitalik D, Majumdar BK, Gupta V, Kumar A, Dalal BS, Malik A. Rhinosporidiosis of lacrimal sac: An interesting case of orbital swelling. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2016;7:98-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Behera S, Chowdhury RK, Dora J. Rhinosporidiosis of the lacrimal sac in a tertiary care hospital of India - A retrospective case study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70:1732-1735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bothra N, Rath S, Mittal R, Tripathy D. External dacryocystorhinostomy for isolated lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis - A suitable alternative to dacryocystectomy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67:665-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rajesh Raju G, Sandeep S. Lacrimal Sac Rhinosporidiosis and Surgical Management by Transnasal Endoscopic Excision: A Case Series. Laryngoscope. 2018;128:2693-2696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Arseculeratne SN. Recent advances in rhinosporidiosis and Rhinosporidium seeberi. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2002;20:119-131. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Job A, Venkateswaran S, Mathan M, Krishnaswami H, Raman R. Medical therapy of rhinosporidiosis with dapsone. J Laryngol Otol. 1993;107:809-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/