INTRODUCTION

Hypophosphatasia (HPP) is a rare inherited disorder caused by loss-of-function mutations in the alkaline phosphatase (ALP) gene, which encodes tissue-nonspecific ALP (TNSALP)[1]. Deficiency of TNSALP leads to accumulation of substrates such as inorganic pyrophosphate, phosphoethanolamine, and pyridoxal 5’-phosphate (vitamin B6), which interfere with bone and dental mineralization[1].

HPP is sometimes confused with hypophosphatemia due to shared features of impaired bone mineralization; however, they are distinct conditions. HPP arises from deficient TNSALP activity and low serum ALP[2,3], whereas hypophosphatemia is characterized by low serum phosphate resulting from renal phosphate wasting, gastrointestinal loss, or nutritional deficiency and is typically associated with normal or elevated ALP levels[4-6].

HPP presents differently depending on age. In adults, common features include musculoskeletal pain, recurrent or poorly healing fractures, premature loss of permanent teeth, and fatigue[3,7]. Functional limitations and reduced quality of life are common. However, diagnosis is frequently delayed, in part due to low clinical suspicion and symptom overlap with other chronic pain conditions such as fibromyalgia[8-10].

These challenges were illustrated in a recently published case report in the World Journal of Clinical Cases, which described diagnostic delays and psychiatric consequences following misclassification of HPP as fibromyalgia[11]. Far from isolated, this case reflects patterns that are increasingly substantiated by epidemiologic data. Severe perinatal or infantile forms of HPP occur in approximately 1 individual in 100000 individuals, whereas milder adult forms may occur as frequently as 1 in 6300. The estimated carrier frequency of pathogenic ALP mutations ranges from 1 in 150 to 1 in 275 in North American and European populations[12].

This diagnostic vulnerability is compounded by the clinical overlap between HPP and more commonly diagnosed conditions, such as fibromyalgia. Fibromyalgia, by contrast, is a clinical diagnosis characterized by widespread pain, fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and nonrestorative sleep[13-15]. Fibromyalgia affects an estimated 0.8% to 5% of the adult population worldwide, with prevalence varying depending on region, diagnostic criteria, and method of ascertainment[16,17]. It is typically diagnosed by exclusion, as no confirmatory biomarkers exist. Although research has explored potential mechanisms such as pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., interleukin-6, interleukin-8) and mitochondrial dysfunction that may contribute to fibromyalgia pathophysiology[17,18], these findings have not resulted in clinically validated diagnostic tools. The broad diagnostic criteria and nonspecific symptomatology of fibromyalgia increase the risk of misdiagnosis in patients with other underlying disorders, including HPP[9,15].

CURRENT DIAGNOSTIC LANDSCAPE

A growing body of evidence suggests that HPP is frequently misdiagnosed as fibromyalgia, particularly in adult patients presenting with chronic, treatment-resistant pain. In a single center study, up to 19% of patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia were shown to exhibit biochemical findings consistent with HPP[9], representing potential misdiagnosis. However, this 19 percent figure is limited by the external validity of single-center data and has not been validated in multicenter or population-based studies. The generalizability of this finding remains uncertain. These observations highlight the urgent need for broader international, multicenter epidemiologic research to more accurately establish the true prevalence of HPP misdiagnosis.

Additional studies have supported this diagnostic overlap. In a retrospective study of adults with fibromyalgia and persistently low ALP, 44% had a history of fractures, raising concern for undiagnosed HPP. Despite this, none had undergone vitamin B6 testing or genetic evaluation, suggesting that HPP had not been considered in their diagnostic workup[19]. These findings highlight how patients with HPP may be misclassified when symptoms such as chronic pain and fatigue are attributed to more common diagnoses without adequate metabolic evaluation.

Despite these findings, standard workups for chronic pain and fibromyalgia do not regularly include an evaluation of ALP, even though persistently low levels can point toward a diagnosis of HPP. Many patients with chronic pain or fibromyalgia are started on neuropathic agents, including serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, or tricyclic antidepressants, yet report minimal or no relief[20]. In many cases, symptoms persist despite treatment, delaying further investigation and allowing an underlying metabolic condition such as HPP to remain unrecognized, if present.

GENDER BIAS AND THE CONSEQUENCES OF MISDIAGNOSIS

The problem of missed HPP diagnosis is not gender-neutral. Fibromyalgia is more commonly diagnosed in women, with studies estimating a female-to-male ratio of approximately 3:1[21].

This disparity may reflect both sex-based biological predispositions, such as hormonal or neurological differences, and gendered sociocultural factors, including provider expectations and diagnostic stereotypes. Growing evidence suggests that the diagnostic process itself may reinforce these patterns by attributing nonspecific symptoms such as chronic pain, fatigue, and diffuse tenderness to fibromyalgia without adequately considering alternative explanations[16,22]. It also reflects a broader pattern in which women’s symptoms are more likely to be interpreted as emotional or attributed to stress in the absence of objective findings[23].

Gender bias in pain care has been well documented. A theory-guided review identified how gendered norms shape provider expectations, often leading clinicians to interpret women’s pain as emotional or psychosomatic. This contributes to perceptions of women with chronic pain as exaggerating, emotional, or difficult to treat, particularly when symptoms lack clear imaging or laboratory correlates[24]. Qualitative research further shows that women with pain often feel they must work to appear credible in clinical encounters[25]. In the context of HPP, this dynamic can be especially harmful. Women with vague, multifocal pain and persistently low ALP may be labeled with fibromyalgia or another diagnosis based primarily on symptom patterns, without adequate investigation of potential metabolic causes.

These disparities are magnified for patients at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities. For example, non-White patients with fibromyalgia reported greater symptom burden and reduced treatment response[26]. Racial and ethnic minorities also remain underrepresented in fibromyalgia clinical trials[27]. Additional studies describe how credibility in clinical pain narratives is racialized[28], and how structural barriers limit access to appropriate pain care[29]. Together, these studies highlight the importance of addressing intersectional bias in the diagnosis and management of chronic pain.

Gender bias in pain management remains deeply entrenched. Women with chronic pain are more frequently perceived as exaggerating, emotional, or difficult to treat, reflecting gendered biases in provider judgments that can influence both pain estimates and treatment recommendations[30]. These patterns reflect gendered norms that frame women’s pain as less credible. Recent studies reinforce this: Medical students have been shown to underestimate women’s pain and recommend less aggressive management[31]. In response, some researchers have called for gender-sensitive diagnostic frameworks that integrate both biological and psychosocial factors[32,33]. These issues are particularly concerning in conditions such as HPP, where vague symptoms and limited provider familiarity increase diagnostic uncertainty. In these cases, gendered biases may further delay accurate recognition and appropriate care.

This bias becomes especially harmful in conditions like HPP, where diagnostic uncertainty may reinforce existing bias and further delay appropriate recognition and treatment.

PSYCHIATRIC TOLL AND EROSION OF TRUST

Some patients with chronic pain may exhibit signs of central sensitization, a process in which the nervous system amplifies pain signals, resulting in heightened sensitivity to normally non-painful stimuli[13]. Neuroimaging studies in fibromyalgia, for example, have demonstrated altered brain activity in response to sensory input, supporting a role for central mechanisms in pain processing[34].

However, when clinical features such as persistently low alkaline phosphatase or premature tooth loss are present, attributing symptoms to a diagnosis of exclusion without investigating potential metabolic or structural causes can result in misdiagnosis. This may delay appropriate evaluation and prolong suffering. A mixed-methods study involving qualitative interviews and quantitative surveys of 48 patients misdiagnosed with psychosomatic illness more than 80% reported lasting harm to their self-worth, and 72% remained emotionally distressed by the experience. Many reported avoiding care or under-reporting symptoms due to fear of being dismissed[35]. A separate study of adults with HPP found significantly elevated scores for depression, anxiety, and stress compared to population norms[36]. These psychiatric outcomes may reflect the emotional toll of diagnostic delays and misattribution of symptoms, rather than a direct effect of the underlying disease itself.

REFRAMING LOW ALP: A DIAGNOSTIC CLUE, NOT A LAB ANOMALY

Serum ALP is included in standard comprehensive metabolic panels, but its diagnostic relevance is often overlooked when values are low in adults[10,36]. Unlike fibromyalgia, which is thought to arise from central sensitization and altered central pain processing, HPP has a clearly defined metabolic etiology caused by TNSALP deficiency[1,9]. Low ALP is not pathognomonic for HPP, but in adults with chronic pain, non-healing fractures, or premature tooth loss, it should prompt further evaluation, including measurement of pyridoxal 5’-phosphate[10,36].

This mechanistic distinction underscores the clinical utility of ALP: While fibromyalgia lacks confirmatory biomarkers, persistently low ALP is a specific, underrecognized clue that may help differentiate HPP from other causes of musculoskeletal pain[19]. Current diagnostic frameworks for fibromyalgia, including the 2010 and 2016 American College of Rheumatology criteria, are based entirely on symptom reporting and do not incorporate laboratory evaluation, such as ALP[37,38]. As a result, patients with chronic musculoskeletal symptoms and persistently low ALP may be misdiagnosed.

Although fibromyalgia remains a diagnosis of exclusion, we propose that in patients with chronic musculoskeletal symptoms and persistently low ALP, clinicians consider metabolic screening. This may include measurement of pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (vitamin B6), genetic testing for ALP mutations, and clinical assessment for features suggestive of HPP, such as non-healing fractures or premature tooth loss. Persistently low ALP is often overlooked in patients with musculoskeletal symptoms suggestive of a metabolic disorder, leading to delayed diagnoses of HPP[36]. Greater consideration of HPP in the differential diagnosis could enhance diagnostic precision and reduce unnecessary morbidity.

CONCLUSION

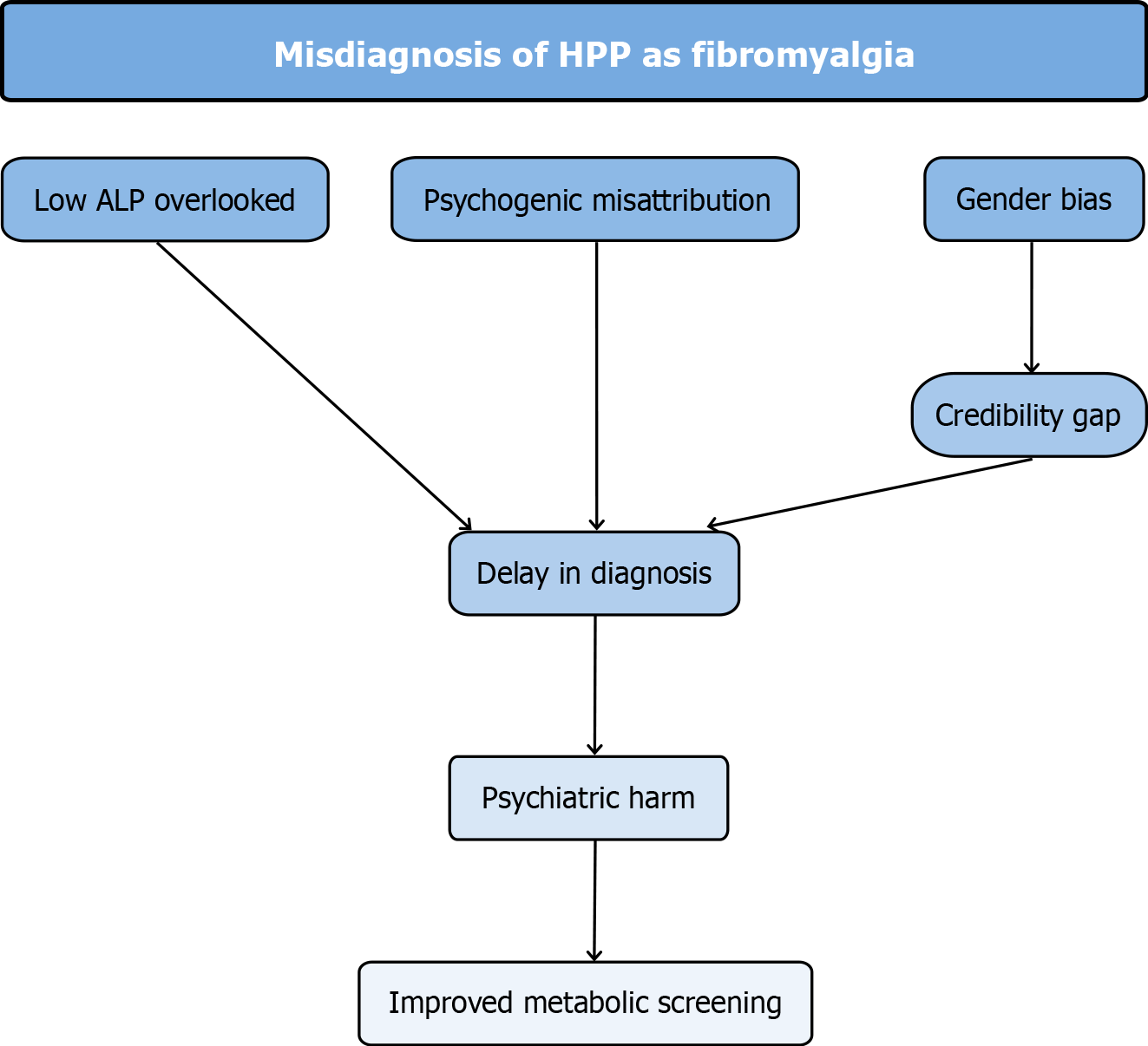

HPP should be considered early in the diagnostic process for patients with unexplained musculoskeletal symptoms and persistently low ALP. When symptoms are misattributed to fibromyalgia, delayed recognition can lead to prolonged suffering and psychological harm. These dynamics are illustrated in Figure 1, which outlines how persistently low ALP, gender bias, and psychogenic misattribution contribute to diagnostic delay and psychiatric harm in HPP.

Figure 1 Flowchart of key concepts contributing to the misdiagnosis of hypophosphatasia as fibromyalgia.

Overlooked low alkaline phosphatase, psychogenic misattribution, and gender bias, particularly the credibility gap faced by women, contribute to delayed diagnosis. This delay can result in psychiatric harm, including erosion of trust, depression, and anxiety, and highlights the importance of improved metabolic screening in chronic pain evaluation. HPP: Hypophosphatasia; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase.

These intersecting factors highlight the need for targeted interventions at both the clinical and systems levels. In light of the diagnostic challenges outlined in Figure 1 and the need to reduce diagnostic delays and improve outcomes, we recommend: (1) Improved clinician education about the clinical presentation of HPP and its overlap with fibromyalgia; (2) Routine consideration of low ALP as a meaningful diagnostic clue in patients with chronic pain; (3) Implementation of electronic decision tools that flag persistently low ALP for metabolic evaluation; (4) Development of an international, multicenter registry to better define the prevalence of HPP misdiagnosis and to inform future guidelines; (5) Inclusion of low-ALP metabolic screening in future consensus statements on chronic pain assessment by the American College of Rheumatology, the International Association for the Study of Pain, and the World Institute of Pain; and (6) Collaboration with patient organizations to incorporate qualitative interviews and first-person narratives into future work.

These strategies could facilitate earlier diagnosis, reduce gender- and condition-based diagnostic inequities, and reduce the emotional consequences of clinical mislabeling. More broadly, addressing diagnostic disparities will require institutional focus on both clinical data and the sociocultural dynamics that shape how patients are heard, investigated, and treated. Incorporating these efforts into continuing education, electronic health records, and diagnostic guidelines may help advance system-level change.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the patients whose clinical journeys inspired this work.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade C, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: Pavón L, MD, Professor, Mexico; Zhou JH, MD, Associate Chief Physician, China S-Editor: Bai Y L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xu J