Published online Oct 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i30.108934

Revised: May 19, 2025

Accepted: August 15, 2025

Published online: October 26, 2025

Processing time: 168 Days and 21.8 Hours

Obesity remains a significant global health concern, and intragastric balloons (IGBs) offer a minimally invasive weight loss option for patients who fail lifestyle and pharmacotherapy interventions. IGBs can cause complications ranging from mild symptoms to severe issues like gastric outlet obstruction (GOO). This report discusses a 39-year-old woman who presented with clinical and radiological features of GOO post Silimed IGB placement.

A 39-year-old woman presented to our institution with two-week history of abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting post prandially. This was in the context of a Silimed IGB placement two weeks prior to presentation for weight loss in the context of obesity. A computed tomography of the abdomen demonstrated the IGB device in the body and prepyloric region, with proximal dilatation of the body and fundus of the stomach which contained gastric contents. Due to con

This is the first reported case of GOO caused by Silimed IGB. While effective for weight reduction, IGB-related GOO is a rare but serious complication, usually requiring endoscopic retrieval. Future research should aim to identify patient factors linked to this complication to enhance clinical-decision making and outcomes.

Core Tip: Gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) secondary to intragastric balloon (IGB) insertion for obesity management is a rare and severe complication with significant patient morbidity. The onset of symptoms of GOO secondary to IGB is variable with the management usually endoscopic. We present the case of a 39-year-old woman who presented with clinical and radiological features of GOO secondary to Silimed IGB insertion which was successfully managed with endoscopic removal. The article reveals a predilection for this complication in women with endoscopic removal being the most co

- Citation: O’Neill RS, Goh LH, Lee C, Jia K, Feller R. Endoscopic management of intragastric balloon related gastric outlet obstruction: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(30): 108934

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i30/108934.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i30.108934

Obesity is a complex, chronic disease and is a leading yet largely preventable cause of morbidity and mortality world

Lifestyle modification (LM) is the first-line treatment for obesity. Despite intensive LM that includes calorie restriction, increased physical activity and structured behavioural programs, weight loss is typically minimal to moderate[5]. Most patients struggle to maintain a long-term weight loss of at least 5%[6]. Newer anti-obesity medications, particularly the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, have shown superior outcomes compared to older therapies and are in

These factors have prompted further research into less-invasive alternatives that could potentially be more acceptable to the general population, notably endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies (EBMTs). These therapies have been developed and refined over the past three decades and are now increasingly performed worldwide[14,15]. Examples of EBMTs are intragastric balloons (IGBs), endoscopic gastric remodelling, and endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty[16]. IGBs have emerged as an effective yet minimally invasive, temporary method of inducing weight loss, with previous studies demonstrating a mean absolute weight loss of 6.12 kg and mean percentage of excess weight loss of 17.98%[17]. Since their inception, IGBs have evolved and with this, the complication rate associated with their insertion has reduced dramatically. Although IGBs offer a less invasive approach to weight loss, complications can still occur. The reported complication rates are approximately 0.7% and 6.37% for major and minor complications respectively, with early removal (before 6 months) required in 3.62% of cases[18]. Common adverse events include abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. Significant complications, namely spontaneous deflation and IGB migration, and gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) are relatively rare entities with the literature only limited to case reports. Regarding IGB related intestinal or gastric obstruction, it is reported that approximately 0.8% of balloons insertion results in this complication[19]. Although the incidence of this complication is low, early recognition and timely intervention are crucial to reduce the risk of gastric ulceration and subsequent perforation.

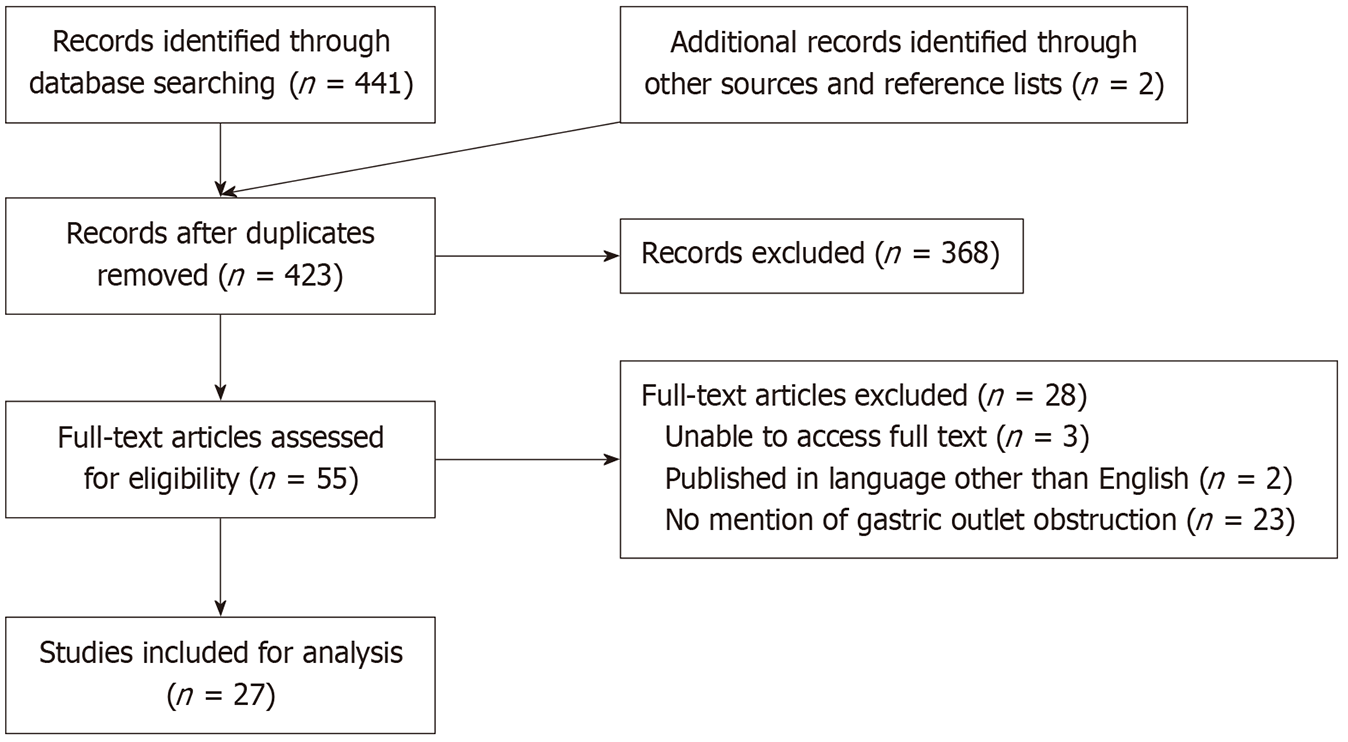

Here, we present a case of a 39-year-old woman who presented to our institution with clinical and radiological features suggestive of a GOO two weeks after the insertion of a Silimed IGB. Additionally, the article was conducted to further characterize and analyse this complication in the context of IGB insertion. To investigate the incidence of GOO with IGB insertion, we conducted a literature search to identify studies relevant to the article. A PubMed literature search was conducted using the search strategy {[“balloon” (All Fields)] AND [“gastric” (All Fields)] AND [“obstruction” (All Fields)]}. We subsequently performed a more focused search on Web of Science with the search strategy [All = (Intragastric balloon) AND (Gastric outlet obstruction)]. The search was performed by two of the authors (O’Neill RS and Goh LH). All article types discussing GOO resulting from IGB insertion were considered for inclusion in the article. The time frame for inclusion extended from inception until the August 26, 2024. The inclusion criteria required the articles to be published in English, either as full texts or abstracts, and fall within the specified date range. Moreover, each article had to document at least one case of GOO in relation to IGB placement. Any articles where the abstract or full text was unavailable for review were excluded from the analysis. Articles that were not published in English, or did not reference both GOO and IGB placement were also excluded. After applying these criteria, the selected articles were carefully examined to extract relevant data, including the number of cases reported and detailed information pertaining to each case. Additionally, the reference lists of the included articles were thoroughly reviewed, and any additional cases that met the inclusion criteria were added to the analysis.

An initial literature search on PubMed identified 414 articles. After reviewing article titles and abstracts, 368 articles were excluded. Of the 46 remaining articles, 28 were further excluded due to being non-English publications or lacking relevant information on GOO in the full-text review. A more targeted search using the Web of Science yielded 27 additional articles. After removing duplicates, seven additional articles were added to the analysis. Further analysis of article reference lists revealed an additional two articles which were included for analysis. Figure 1 depicts the search algorithm implemented for the study. A total of 27 articles[20-46] (Table 1) were included in the final analysis, identifying 29 cases of GOO secondary to IGB insertion. The vast majority of these cases were female (92.3%), with most having a history of obesity necessitating IGB insertion. Other common comorbidities included dyslipidaemia, pre-diabetes, iron deficiency anaemia, and hiatus hernia. All patients presented with gastrointestinal symptoms, primarily nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. The onset of symptoms following IGB insertion varied widely, ranging from as early as three days to as late as 18 months. The median BMI on insertion was 35 kg/m2, while the median age was 44 years old. The most implicated IGB was the Orbera IGB (38.1%) followed by the Allurion IGB (28.6%). The most frequently used diagnostic tool was an abdominal computed tomography (78.3%), which typically revealed a dilated stomach proximal to the balloon. In most cases, endoscopic removal of the balloon was the standard treatment (93.1%), however, there were two notable exceptions. A congress reported a case in which GOO caused by an Allurion-Elipse IGB that was successfully resolved through percutaneous aspiration of the balloon’s contents, allowing it to pass naturally without the need for endoscopic or surgical intervention[36]. An article described a case where endoscopic removal failed, necessitating laparoscopic intervention to remove the IGB[37]. After removal, symptoms and electrolyte abnormalities resolved in most patients, with minimal complications. The most common complication was gastric ulceration at the site of IGB insertion. More serious complications included two cases of esophageal perforation associated with the use of an overtube during IGB removal[27,28]. In these cases, the patients developed odynophagia and fever within a day of the procedure. Both were managed conservatively with intravenous antibiotics.

| Ref. | Case | Age | Sex | Time post IGB insertion | Balloon brand | Comorbidities | BMI (kg/ | Diagnostic modality | Removal method | Endoscopic findings | Outcome | Complication |

| [20] | 1 | NR | NR | 30 months | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| [21] | 2 | 43 | F | 7 months | Orbera | Obesity | 36 | CT | Endoscopic | IGB occupying the entire gastric fundus and body causing obstruction | NR | NR |

| [22] | 3 | NR | NR | 15 days | Allurion-Elipse | NR | 36.5 | X-ray | Endoscopic | IGB impaction in antrum | SR | Nil |

| [23] | 4 | 42 | F | 7 weeks | Orbera | Obesity | 31 | X-ray | Endoscopic | Hyperinflated IGB with pyloric obstruction; fluid culture positive Candida parapsilosis | SR | Nil |

| [24] | 5 | 43 | F | 3 weeks | Allurion-Elipse | Nil | NR | CT | Endoscopic | Appropriate placement; no features of hyperinflation | SR | Nil |

| [25] | 6 | 68 | F | 2 weeks | BioEnterics | NR | NR | CT | Endoscopic | NR | SR | Nil |

| [26] | 7 | NR | NR | NR | Allurion-Elipse | NR | NR | Endoscopic | NR | NR | NR | |

| [27] | 8 | 59 | F | 2 months | BioEnterics | Obesity, GORD, sickle cell disease | 35 | CT | Endoscopic | IGB in fundus; small hiatal hernia | Odynophagia | Esophageal perforation |

| [28] | 9 | 59 | F | 9 weeks | BioEnterics | Obesity, GORD, cholecystectomy | 35 | X-ray | Endoscopic | NR | SR | Esophageal perforation |

| [29] | 10 | 35 | F | 2 weeks | NR | Obesity, leiomyoma, hiatus hernia | 34 | CT | Endoscopic | NR | SR | Nil |

| [30] | 11 | 43 | F | 2 months | MedSil | Obesity | NR | CT | Endoscopic | NR | SR | Nil |

| [31] | 12 | 42 | F | 6 months | Orbera | Obesity | 36 | CT | Endoscopic | Fluid stasis; superficial gastric ulceration | SR | Nil |

| [32] | 13 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Endoscopic | NR | NR | NR |

| [33] | 14 | 53 | F | 1 week | NR | Obesity | 39 | CT | Endoscopic | NR | SR | Nil |

| [34] | 15 | 45 | F | 2.5 weeks | Orbera | Obesity | NR | CT | Endoscopic | Normal | SR | Nil |

| [35] | 16 | 42 | M | 10 days | NR | T2DM, obesity, MASLD | NR | CT | Endoscopic | NR | SR | Nil |

| [36] | 17 | 29 | F | 2 months | Allurion-Elipse | Obesity | 29 | US | Percutaneous aspiration | NR | SR | Nil |

| [37] | 18 | 44 | F | 18 months | NR | Obesity, hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis | 50.6 | NR | Failed endoscopy; proceeded to laparoscopy | NR | SR | Nil |

| [38] | 19 | 52 | F | NR | NR | Obesity | NR | CT | Endoscopic | Gastric body ulceration | SR | Gastric ulceration |

| 20 | 43 | F | NR | NR | IDA, uterine fibroids, limited SSc, obesity | NR | CT | Endoscopic | Hyperinflated IGB, solid debris in fundus and gastric body | SR | Nil | |

| [39] | 21 | 49 | F | 4 months | Orbera | Obesity, dyslipidaemia, prediabetes, hypertension | 35.5 | CT | Endoscopic | Hyperinflated IGB, gastric body erythema, ulceration and erosions | SR; new IGB inserted | Nil |

| [40] | 22 | 67 | F | 3 days | Orbera | Obesity | NR | CT | Endoscopic | Grade D esophagitis; balloon present in body/antrum. Unable to pass gastroscope | SR | Grade D esophagitis |

| [41] | 23 | 39 | F | 2 months | Orbera | Obesity | 33.6 | CT | Endoscopic | Hyperinflated IGB | SR | Nil |

| [42] | 24 | 63 | M | 2 months | Bioenterics | Hypertension, T2DM, CAD, gout | NR | X-ray | Endoscopic | Erosive oesphagitis, IGB lodged in gastric antrum | SR | Nil |

| [43] | 25 | 46 | F | 3 months | Orbera | Obesity | 31.6 | X-ray | Endoscopic | Gastric residue; IGB hyperinflation | SR | Nil |

| [44] | 26 | 51 | F | 2 weeks | Allurion-Elipse | Nil | NR | CT | Endoscopic | NR | SR | Nil |

| [45] | 27 | 44 | F | 5 days | Spatz3 system | NR | NR | NR | Endoscopic | Linear gastric erosions and mild esophagitis | SR | Nil |

| 28 | 51 | F | 3 weeks | Allurion-Elipse | NR | NR | NR | Endoscopic | NR | SR | Nil | |

| [46] | 29 | 41 | F | NR | Spatz3 system | Obesity | 25.8 | CT | Endoscopic | NR | SR | Nil |

A 39-year-old Spanish woman presented to our institution with a two-week history of abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting post-prandially to both liquids and solids.

This was following the insertion of a Silimed IGB two weeks earlier for weight loss. She had an office job and led a sedentary lifestyle. She was obese with a BMI of 32 kg/m2.

She had no medical issues and was not on any regular medications.

She had no medical history nor significant family history.

Her initial examination demonstrated epigastric tenderness with an obvious palpable mass consistent with the recently inserted IGB.

Initial biochemical assessment was unremarkable.

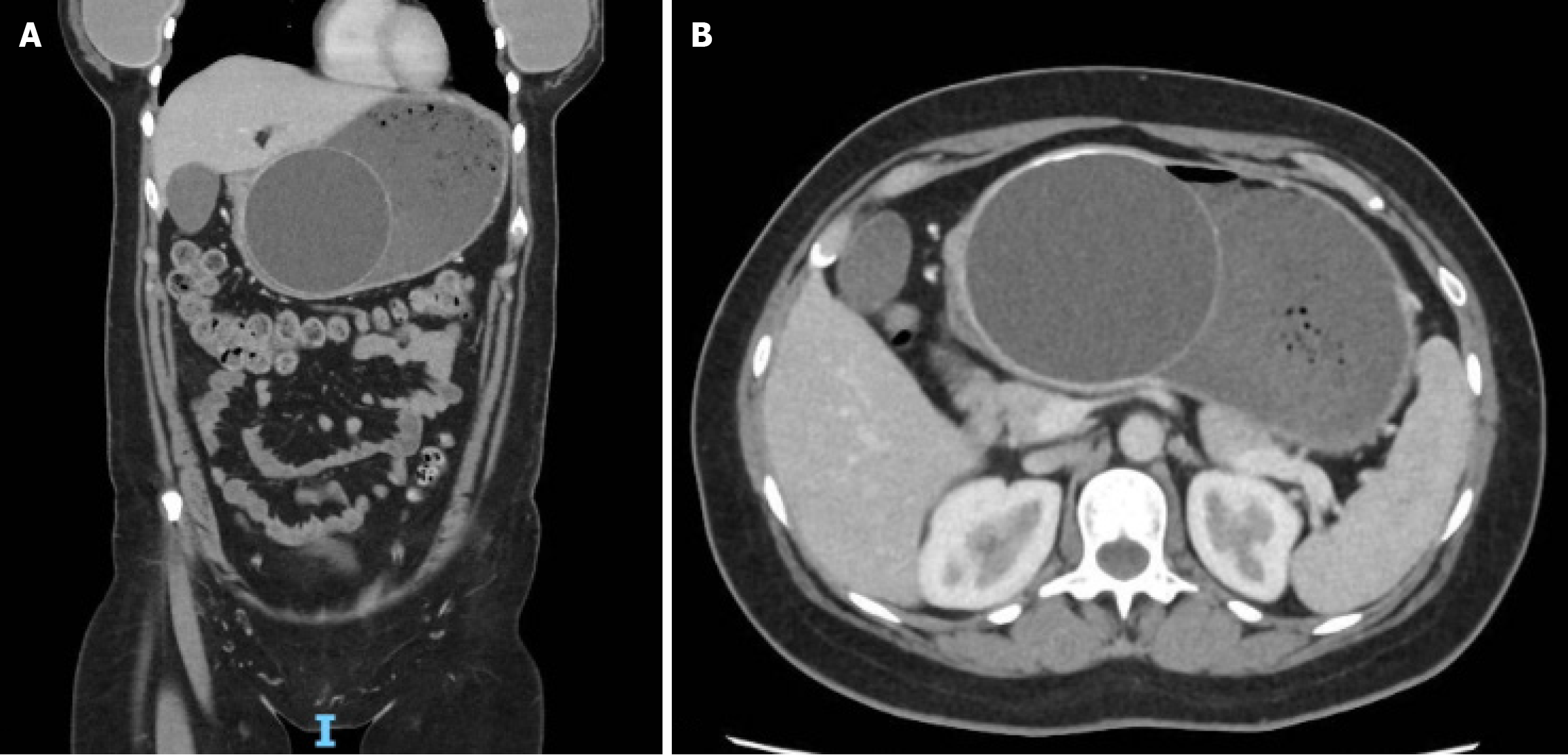

A computed tomography of the abdomen demonstrated the IGB device in the body and prepyloric region, with proximal dilatation of the body and fundus of the stomach which contained gastric contents. Thickening of the pylorus was also noted (Figure 2).

The clinical and radiological findings were consistent with a GOO secondary to IGB insertion.

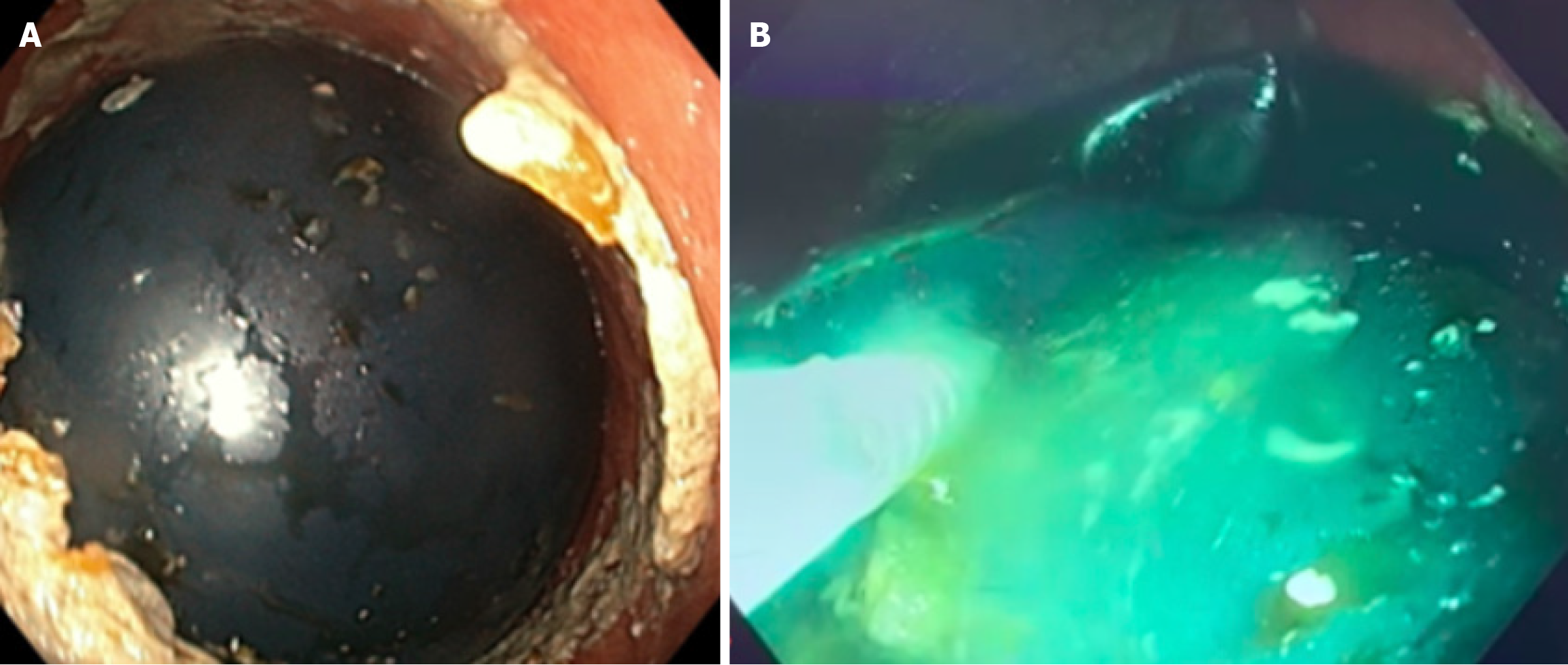

Attempted external manipulation of the IGB via abdominal palpation was unsuccessful, and due to clinical features consistent with a GOO, the patient proceeded to have an urgent endoscopy. Endoscopic evaluation revealed a food bezoar in the proximal body of the stomach and fundus, accompanied by a dilated proximal stomach (Figure 3A). Distally, the IGB was visualized in the prepyloric region and distal antrum of the stomach. Passage of the adult gastroscope beyond the IGB to access the pylorus was not successful, reaffirming the clinical suspicion of a GOO. Using an injector needle, fenestrations were made in the IGB, and suction was applied, leading to decompression. Approximately five hundred millilitres of methylene blue solution was removed, successfully deflating the balloon (Figure 3B). The deflated IGB was then retrieved endoscopically using raptor grasping forceps. Post-retrieval examination of the distal antrum and prepyloric region revealed no ulceration or perforation.

The patient’s symptoms resolved following the procedure with no further complications. She was monitored overnight and was discharged home in a stable condition.

Obesity is a global epidemic affecting approximately 760 million adults, with numbers expected to rise further[3]. The disease is a chronic, relapsing disease driven by a complex interplay between genetic predisposition, physiological, psychological, sociocultural and economic factors. It is associated with a range of morbidities, including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, liver disease, certain cancers, osteoarthritis, and depression[47,48]. Obesity is particularly stark in developing countries, with these communities often faced with the burden of undernutrition, a heavy reliance on inexpensive, calorie-dense processed foods, and a lack of awareness about obesity’s health implications[3]. Coupled with limited healthcare resources, this only serves the rising prevalence of the disease and further increases the strain on the already fragile healthcare systems. On the other hand, the key contributor of obesity in high-income countries stems from an abundance of food supplies, sedentary lifestyles, and, in some cases, cultural attitudes that associate higher weight with wealth and affluence, despite significantly better access to healthcare education[3,49]. This highlights the need for context-specific, comprehensive interventions that address socioeconomic inequities, cultural perceptions, and the broader determinants of health.

As obesity becomes more common, and its associated health risks are better understood, there is a growing emphasis on exploring weight loss strategies beyond LM and pharmacological treatments. This has led to the rising popularity of bariatric surgery, including sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. While these surgical options are effective, they are not without limitations. Many patients face barriers to access bariatric surgery due to financial constraints, limited availability, and the potential for significant complications[50]. Furthermore, the fear of undergoing invasive surgery often deters individuals, especially when non-surgical alternatives are available. As such, EBMT procedures such as IGB and endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty have emerged as an attractive option for weight loss given their minimally invasive nature and perceived lower complication rates compared to traditional bariatric surgery. They can also serve as an adjuvant therapy prior to bariatric surgery. Unfortunately, for the majority of individuals with obesity, socioeconomic constraints limit their access to pharmacotherapy, bariatric surgery and endoscopic bariatric procedures. The most recent guidelines published by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy made a conditional recommendation (based on low quality evidence) that in those with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, with or without an obesity-related comorbidity, or a BMI of 27 to 29.9 kg/m2, with at least one obesity-related comorbidity, should pursue EBMT alongside LMs rather than relying on LMs alone[16]. With these recommendations, it is likely that adoption of these approaches will increase among clinicians, which may subsequently lead to a rise in procedural-related complications.

IGBs were initially introduced in the 1980s as a novel, minimally invasive option for weight loss. It was inspired by the observation that bezoars, or foreign objects in the stomach could induce a sensation of satiety and reduce food intake. The utility of early iterations of the IGBs were unfortunately limited due to the high rates of complications such as gastric ulcers, balloon deflation and migration. Subsequent advancements in materials and designs lead to a resurgence in their popularity in the 2000s. Newer devices such as the Orbera, Spatz3 and Allurion-Elipse balloons were designed to be more durable, with enhanced biocompatibility and better patient tolerance[51,52]. IGBs rely upon a soft balloon that is filled with either saline, methylene blue or air and placed in the stomach[51,52]. The mechanism through which IGBs promote weight loss is by restriction of stomach volume and likely by a change in gut motility[53]. It is typically inserted endoscopically. Alternatively, the device can be swallowed, negating the need for endoscopic placement. In terms of efficacy, newer IGB models can achieve a BMI reduction of 5-9 points during the six-month period they remain in place; however, there is a risk of rebound in weight gain after removal[54].

Whilst the perception is that IGBs are well tolerated, more than 90% of patients develop nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia and abdominal pain, and approximately 6% of patients require early removal due to intolerance. Less frequent but more severe complications include balloon leakage, gas production, migration, GOO, pancreatitis and visceral perforation[55]. These severe complications are low, ranging from approximately 1%-6%[18,19]. GOO is the mechanical blockage of gastric emptying and presents with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, distension, early satiety and weight loss[56]. It is a relatively uncommon complication associated with IGB insertion with the literature only limited to isolated case reports. The timing of this complication is unpredictable, with cases published demonstrating diagnosis within three days of insertion or up to 18 months. However, it is important to note that in cases where GOO occurred after six months, inadequate patient follow up could be cited as an explanation for the complication rather than the device or procedure itself. Review of the literature demonstrates that GOO occurs more frequently in women, with the most frequently implicated IGB being the Orbera IGB. Complications associated with GOO secondary to IGB are mainly gastric ulceration and erosions secondary to pressure necrosis, while electrolyte abnormalities secondary to vomiting have been previously reported in the literature. All four Food and Drug Administration - approved IGBs required endoscopic removal after 6 months due to the risk of spontaneous deflation and migration.

Endoscopic removal is the most effective and commonly pursued modality with regards to management of GOO secondary to IGB. Percutaneous aspiration and spontaneous passage of the IGB have also been published in the past along with laparoscopic removal post endoscopic failure[36,37]. The advantage of endoscopic removal of IGB causing GOO allows for inspection of the surrounding gastric mucosa to assess for localised complications, namely erosions and ulceration. These complications may be missed in the case of surgical or percutaneous removal, subsequently resulting in significant morbidity to the patient. Effective removal of an impacted IGB results in rapid symptom amelioration. However, complications after removal, namely esophageal perforation have been documented, particularly in cases where an endoscopic overtube was used during IGB extraction[27,28]. Although IGBs are effective at inducing weight loss, patients must remain highly motivated to sustain their weight loss through regular exercise and a healthy diet upon removal of the balloon. However, many individuals struggle to maintain these LMs, often regaining weight and reverting to their original BMI[57-59]. To support long-term success, education and a strong awareness about the health risks associated with obesity are critical. In many developing countries, socioeconomic challenges exacerbate the issue. Addressing these underlying factors is essential to achieving sustainable weight management in these population[3].

Our case resembles previous literature, particularly regarding patient demographics and the timing of removal. Notably, this is the first published case documenting GOO secondary to the use of the Silimed IGB. A potential explanation for this could be the less frequent use of the Silimed IGB compared to other IGBs namely the Orbera, Spatz3 and Allurion-Elipse, which are more commonly employed in clinical practice[60]. Although the incidence of GOO secondary to IGB is reported as low, several factors may contribute to this finding. There is likely an element of reporting bias in the published literature regarding outcomes following IGB insertion. In the presented case, proximal dilatation on cross sectional imaging along with endoscopic visualisation of a food bezoar proximal to the IGB with upstream gastric dilatation affirmed the presence of an iatrogenic GOO. Future studies should judiciously document imaging and endoscopic findings in patients presenting with this perceived “intolerance” following IGB insertion to ensure accurate reporting of complications, including but not limited to GOO. This allows clinicians to be informed in their clinical practice, and more importantly, allows patients to make informed decisions regarding endobariatric procedures.

A major limitation of this study lies in the selection of studies included for analysis. Due to the rarity of this complication, most of the studies were case reports, highlighting a distinct lack of robust evidence for analysis. Among the included studies, two were prospective observational studies[22,26], and two were retrospective cohort studies[20,32]. Despite their inclusion in this article, it should be noted that details pertaining to the cases of GOO secondary to IGB were limited in the published articles, thus limiting their value with reference to inclusion for qualitative and quantitative analysis. Additionally, the heterogeneity of study designs, patient populations, and reporting criteria further complicates the ability to draw definitive conclusions. Moreover, reporting bias is likely a significant factor affecting the literature. Many studies classify “patient intolerance” as a reason for early IGB removal without fully elucidating an underlying complication such as a GOO or partial GOO. This misclassification may lead to an underestimation of the true incidence of GOO. Standardised reporting criteria for IGB-related complications, including detailed imaging and endoscopic findings, are essential to enhance the accuracy and reliability of future studies. The limited availability of long-term follow-up data further constrains the understanding of IGB efficacy and safety. Most studies focus on short-term outcomes, neglecting the potential for delayed complications or the sustainability of weight loss. Based on the findings of this review that women more frequently present with GOO post IGB insertion, they should be closely monitored following insertion to ensure timely recognition of this complication if it were to occur. This observation however may be influenced by a higher prevalence of obesity in women and therefore a higher proportion of women opting for EBMT including IGB insertion compared to men[3]. This potentially reflects a selection bias or sociocultural factors influencing the pursuit of weight-loss interventions.

Prospective studies should be conducted in centres specializing in EBMT to identify patient demographic and clinical characteristics that increase the risk of developing GOO following IGB insertion. Additionally, future studies should also focus on assessing long-term outcomes in those with IGB insertion to inform about delayed complications and the sustainability of the weight reduction. Such data would be instrumental in redefining clinical guidelines and optimising the safe and effective use of IGBs to enhance their overall success. In addition to this, future studies should aim to determine what method of surveillance can be implemented in patients post IGB insertion to ensure complications do not arise, or in the event where they do, can be addressed in a timely manner. Abdominal ultrasound has previously been implemented in the case of IGB insertion to assess the status of the IGB along with monitor for complications[61]. Given the recommendation that IGBs remain in situ for up to 6 months and the wide variation in time to GOO secondary to IGB insertion, time points for surveillance imaging have not been established. Future studies should aim to determine whether intensive surveillance with abdominal ultrasound in patients post IGB insertion has any clinical utility or is indeed cost effective.

Obesity is a complex and chronic disease with a wide range of serious complications, and requires a comprehensive management. While LM remains the first line of treatment for obesity, many patients often require additional interventions, such as pharmacotherapy, endobariatric procedures or bariatric surgery to achieve a reasonable and sustainable weight reduction. IGB insertion is an endobariatric procedure that is effective in weight reduction and is increasing in popularity. However, IGB insertion resulting in GOO is a concerning complication associated with sig

| 1. | Vranian M, Blaha M, Silverman M, Michos E, Minder C, Blumenthal R, Nasir K, de Carvalho JM, Santos R. The interaction of fitness, fatness, and cardiometabolic risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:E1754. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, McPherson K, Finegood DT, Moodie ML, Gortmaker SL. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378:804-814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2895] [Cited by in RCA: 3050] [Article Influence: 203.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ataey A, Jafarvand E, Adham D, Moradi-Asl E. The Relationship Between Obesity, Overweight, and the Human Development Index in World Health Organization Eastern Mediterranean Region Countries. J Prev Med Public Health. 2020;53:98-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pi-Sunyer X. The medical risks of obesity. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:21-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 630] [Cited by in RCA: 825] [Article Influence: 51.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, Hu FB, Hubbard VS, Jakicic JM, Kushner RF, Loria CM, Millen BE, Nonas CA, Pi-Sunyer FX, Stevens J, Stevens VJ, Wadden TA, Wolfe BM, Yanovski SZ, Jordan HS, Kendall KA, Lux LJ, Mentor-Marcel R, Morgan LC, Trisolini MG, Wnek J, Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Bozkurt B, Brindis RG, Curtis LH, DeMets D, Hochman JS, Kovacs RJ, Ohman EM, Pressler SJ, Sellke FW, Shen WK, Smith SC Jr, Tomaselli GF; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129:S102-S138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1717] [Cited by in RCA: 2134] [Article Influence: 164.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Look AHEAD Research Group; Wing RR. Long-term effects of a lifestyle intervention on weight and cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus: four-year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1566-1575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 621] [Article Influence: 38.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, Davies M, Van Gaal LF, Lingvay I, McGowan BM, Rosenstock J, Tran MTD, Wadden TA, Wharton S, Yokote K, Zeuthen N, Kushner RF; STEP 1 Study Group. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:989-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 699] [Cited by in RCA: 2878] [Article Influence: 575.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, Eliaschewitz FG, Jódar E, Leiter LA, Lingvay I, Rosenstock J, Seufert J, Warren ML, Woo V, Hansen O, Holst AG, Pettersson J, Vilsbøll T; SUSTAIN-6 Investigators. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1834-1844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5185] [Cited by in RCA: 4540] [Article Influence: 454.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Grunvald E, Shah R, Hernaez R, Chandar AK, Pickett-Blakely O, Teigen LM, Harindhanavudhi T, Sultan S, Singh S, Davitkov P; AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee. AGA Clinical Practice Guideline on Pharmacological Interventions for Adults With Obesity. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:1198-1225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 46.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kalas MA, Galura GM, McCallum RW. Medication-Induced Gastroparesis: A Case Report. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2021;9:23247096211051919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Peterli R, Wölnerhanssen BK, Peters T, Vetter D, Kröll D, Borbély Y, Schultes B, Beglinger C, Drewe J, Schiesser M, Nett P, Bueter M. Effect of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy vs Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass on Weight Loss in Patients With Morbid Obesity: The SM-BOSS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;319:255-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 693] [Cited by in RCA: 922] [Article Influence: 115.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Grönroos S, Helmiö M, Juuti A, Tiusanen R, Hurme S, Löyttyniemi E, Ovaska J, Leivonen M, Peromaa-Haavisto P, Mäklin S, Sintonen H, Sammalkorpi H, Nuutila P, Salminen P. Effect of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy vs Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass on Weight Loss and Quality of Life at 7 Years in Patients With Morbid Obesity: The SLEEVEPASS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:137-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 30.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Campos GM, Khoraki J, Browning MG, Pessoa BM, Mazzini GS, Wolfe L. Changes in Utilization of Bariatric Surgery in the United States From 1993 to 2016. Ann Surg. 2020;271:201-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 41.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jirapinyo P, Thompson CC. Endoscopic Bariatric and Metabolic Therapies: Surgical Analogues and Mechanisms of Action. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:619-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hadefi A, Arvanitakis M, Huberty V, Devière J. Metabolic endoscopy: Today's science-tomorrow's treatment. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8:685-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jirapinyo P, Hadefi A, Thompson CC, Patai ÁV, Pannala R, Goelder SK, Kushnir V, Barthet M, Apovian CM, Boskoski I, Chapman CG, Davidson P, Donatelli G, Kumbhari V, Hayee B, Esker J, Hucl T, Pryor AD, Maselli R, Schulman AR, Pattou F, Zelber-Sagi S, Bain PA, Durieux V, Triantafyllou K, Thosani N, Huberty V, Sullivan S. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy-European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on primary endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies for adults with obesity. Gastrointest Endosc. 2024;99:867-885.e64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kotinda APST, de Moura DTH, Ribeiro IB, Singh S, da Ponte Neto AM, Proença IM, Flor MM, de Souza KL, Bernardo WM, de Moura EGH. Efficacy of Intragastric Balloons for Weight Loss in Overweight and Obese Adults: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Obes Surg. 2020;30:2743-2753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Espinet-Coll E, Del Pozo-García AJ, Turró-Arau R, Nebreda-Durán J, Cortés-Rizo X, Serrano-Jiménez A, Escartí-Usó MÁ, Muñoz-Tornero M, Carral-Martínez D, Bernabéu-López J, Sierra-Bernal C, Martínez-Ares D, Espinel-Díez J, Marra-López Valenciano C, Sola-Vera J, Sanchís-Artero L, Domínguez-Jiménez JL, Carreño-Macián R, Juanmartiñena-Fernández JF, Fernández-Zulueta A, Consiglieri-Alvarado C, Galvao-Neto M; Collaborators for the “Spanish Bariatric Endoscopy Group (GETTEMO) of the Spanish Society of Digestive Endoscopy (SEED)”. Evaluating the Safety of the Intragastric Balloon: Spanish Multicenter Experience in 20,680 Cases and with 12 Different Balloon Models. Obes Surg. 2024;34:2766-2777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Imaz I, Martínez-Cervell C, García-Alvarez EE, Sendra-Gutiérrez JM, González-Enríquez J. Safety and effectiveness of the intragastric balloon for obesity. A meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2008;18:841-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lew D, Thampy C, Hawasli A. Lack of efficacy of dual intragastric balloon therapy on weight loss and patient dissatisfaction. Am J Surg. 2021;221:581-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tirumanisetty P, Sotelo JW. S3897 Spontaneous Hyperinflation of an Intragastric Balloon Causing Gastric Outlet Obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:S2486-S2487. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Tønnesen CJ, Hjelmesæth J, Hofsø D, Tonstad S, Hertel JK, Heggen E, Johnson LK, Mathisen TE, Kalager M, Wieszczy P, Medhus AW, Løberg M, Aabakken L, Bretthauer M. A novel intragastric balloon for treatment of obesity and type 2 diabetes. A two-center pilot trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2022;57:232-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lopez-Nava G, Asokkumar R, Bautista I, Negi A. Spontaneous hyperinflation of intragastric balloon: What caused it? Endoscopy. 2020;52:411-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ciprian G, Khoury J, Ramirez L, Miskovsky J. Endoscopy Management of Complete Gastric Outlet Obstruction Secondary to Elipse™ Intragastric Balloon. Cureus. 2021;13:e17542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Redondo-Cerezo E, Martos-Ruiz V, Matas-Cobos A, Ojeda-Hinojosa M, Martínez-Cara JG, Sánchez-Capilla AD, López-de-Hierro-Ruiz M, de-Teresa J. Gastric outlet obstruction after the insertion of a fully filled intragastric balloon. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2013;105:116-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ienca R, Al Jarallah M, Caballero A, Giardiello C, Rosa M, Kolmer S, Sebbag H, Hansoulle J, Quartararo G, Zouaghi SAS, Juneja G, Murcia S, Turro R, Pagan A, Badiuddin F, Dargent J, Urbain P, Paveliu S, di Cola RS, Selvaggio C, Al Kuwari M. The Procedureless Elipse Gastric Balloon Program: Multicenter Experience in 1770 Consecutive Patients. Obes Surg. 2020;30:3354-3362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ruiz D, Vranas K, Robinson DA, Salvatore L, Turner JW, Addasi T. Esophageal perforation after gastric balloon extraction. Obes Surg. 2009;19:257-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sansone NS, Salvatore L. Intragastric Balloon for Obesity Causing Gastric Outlet Obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:S351. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Bolaji O, Oriaifo O, Adabale O, Dilibe A, Wilkinson CC, Graham S, Oluya M. Emergent Management of Gastric Outlet Obstruction Post-Intragastric Balloon: A Case Report Highlighting the Importance of Preoperative Assessments and Postoperative Monitoring in Obesity Management. Am J Case Rep. 2024;25:e942938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kool N, Müggler SA. Gastric outlet obstruction: a rare complication in patients with intragastric balloon treatment for obesity. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Basile P, Marre C, Le Mouel JP. Gastric Obstruction Secondary to an Unexplained Hyperinflation of an Intragastric Balloon. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:A16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jense MTF, Palm-Meinders IH, Sanders B, Boerma EG, Greve JWM. The Swallowable Intragastric Balloon Combined with Lifestyle Coaching: Short-Term Results of a Safe and Effective Weight Loss Treatment for People Living with Overweight and Obesity. Obes Surg. 2023;33:1668-1675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Jotwani PM, Patel AV. Woman With Nausea and Vomiting. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;73:18-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Koek SA, Hammond J. Gastric outlet obstruction secondary to orbera intragastric balloon. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:rjy284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Chapman TP, Taj-Aldeen W, MacFaul G. An unexpected cause of vomiting. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:e9-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | 24(th) IFSO World Congress. Obes Surg. 2019;29:347-1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 37. | Sharroufna M, Hassan A, Alabdrabalmeer M, Alshomimi S. Laparoscopic removal of gastric balloon after failure of endoscopic retrieval. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019;55:210-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Flynn DJ, Soltani AK, Singh A. Spontaneous Intragastric Balloon Hyperinflation: Two Cases and Outcomes. Obes Surg. 2024;34:3087-3090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Craig MA, Kay CL, Stilwell KT, Quiles JG. Weight Loss Success With Repeat Intragastric Balloon Placement After Hyperinflation and Removal of the Index Balloon. ACG Case Rep J. 2023;10:e01071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Fayad L, Simsek C, Khashab MA, Kalloo AN, Kumbhari V. Gastrointestinal: Intragastric balloon: Gastric outlet obstruction or resting in the antrum? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Bomman S, Sanders D, Larsen M. Spontaneous Hyperinflation of an Intragastric Balloon Causing Gastric Outlet Obstruction. Cureus. 2021;13:e15962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Khalaf NI, Rawat A, Buehler G. Intragastric balloon in the emergency department: an unusual cause of gastric outlet obstruction. J Emerg Med. 2014;46:e113-e116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | de Quadros LG, Dos Passos Galvão Neto M, Grecco E, de Souza TF, Kaiser RL Jr, Campos JM, Teixeira A, Filho AC, Macedo G, Silva M. Intragastric Balloon Hyperinsufflation as a Cause of Acute Obstructive Abdomen. ACG Case Rep J. 2018;5:e69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Martins MF, De la Hoz Gomez A, Manivannan A, Shapira-Daniels A, Campbell Reardon CL. Gastric outlet obstruction due to an intragastric balloon in a patient returning from the Caribbean. Clin Case Rep. 2024;12:e8509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Trovato A, Custodio MJ, Ding J, Haff M, Lichtenstein D, Chiu L. S4157 A Case Series: Early Gastric Outlet Obstruction Secondary to Intragastric Balloon Placement. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:S2631. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 46. | Xie J, Patel M, Aquilina G, Kaspar M. S2919 A Novel Case of Gastric Outlet Obstruction From Spatz 3 Adjustable Intragastric Balloon. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:S1209. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 47. | Okunogbe A, Nugent R, Spencer G, Powis J, Ralston J, Wilding J. Economic impacts of overweight and obesity: current and future estimates for 161 countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7:e009773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 86.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1223-1249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6495] [Cited by in RCA: 5846] [Article Influence: 974.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 49. | Brewis A, SturtzSreetharan C, Wutich A. Obesity stigma as a globalizing health challenge. Global Health. 2018;14:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Mathus-Vliegen EM. Endoscopic treatment: the past, the present and the future. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;28:685-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 51. | Moura D, Oliveira J, De Moura EG, Bernardo W, Galvão Neto M, Campos J, Popov VB, Thompson C. Effectiveness of intragastric balloon for obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on randomized control trials. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:420-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Saber AA, Shoar S, Almadani MW, Zundel N, Alkuwari MJ, Bashah MM, Rosenthal RJ. Efficacy of First-Time Intragastric Balloon in Weight Loss: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Obes Surg. 2017;27:277-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Vargas EJ, Bazerbachi F, Calderon G, Prokop LJ, Gomez V, Murad MH, Acosta A, Camilleri M, Abu Dayyeh BK. Changes in Time of Gastric Emptying After Surgical and Endoscopic Bariatrics and Weight Loss: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:57-68.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Mathus-Vliegen EM. Intragastric balloon treatment for obesity: what does it really offer? Dig Dis. 2008;26:40-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Fittipaldi-Fernandez RJ, Zotarelli-Filho IJ, Diestel CF, Klein MRST, de Santana MF, de Lima JHF, Bastos FSS, Dos Santos NT. Intragastric Balloon: a Retrospective Evaluation of 5874 Patients on Tolerance, Complications, and Efficacy in Different Degrees of Overweight. Obes Surg. 2020;30:4892-4898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Koop AH, Palmer WC, Stancampiano FF. Gastric outlet obstruction: A red flag, potentially manageable. Cleve Clin J Med. 2019;86:345-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Dastis NS, François E, Deviere J, Hittelet A, Ilah Mehdi A, Barea M, Dumonceau JM. Intragastric balloon for weight loss: results in 100 individuals followed for at least 2.5 years. Endoscopy. 2009;41:575-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Tai CM, Lin HY, Yen YC, Huang CK, Hsu WL, Huang YW, Chang CY, Wang HP, Mo LR. Effectiveness of intragastric balloon treatment for obese patients: one-year follow-up after balloon removal. Obes Surg. 2013;23:2068-2074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Abbitt D, Choy K, Kovar A, Jones TS, Wikiel KJ, Jones EL. Weight regain after intragastric balloon for pre-surgical weight loss. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2024;16:2040-2046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 60. | Stavrou G, Shrewsbury A, Kotzampassi K. Six intragastric balloons: Which to choose? World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;13:238-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 61. | Francica G, Giardiello C, Iodice G, Cristiano S, Scarano F, Delle Cave M, Sarrantonio G, Troiano E, Cerbone MR. Ultrasound as the imaging method of choice for monitoring the intragastric balloon in obese patients: normal findings, pitfalls and diagnosis of complications. Obes Surg. 2004;14:833-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/