Published online May 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i15.4904

Peer-review started: September 27, 2021

First decision: October 18, 2021

Revised: November 1, 2021

Accepted: April 3, 2022

Article in press: April 3, 2022

Published online: May 26, 2022

Processing time: 239 Days and 11.3 Hours

Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems (LNG-IUSs) gradually release levonorgestrel into the uterus and is effective against hypermenorrhoea and dysmenorrhea. Complications associated with the insertion include expulsion, displacement, and uterine perforation. Ultrasonic identification of copper intrauterine devices (IUDs) is possible due to echogenicity from the copper coils. However, the barium sulfate coatings of LNG-IUSs do not always provide hyperechoic images. Both barium sulfate and copper are radiopaque and clearly identifiable on X-ray. Thus, X-ray imaging is required to locate LNG-IUSs.

A 46-year-old woman with hypermenorrhoea due to submucosal myomas was treated with LNG-IUS at another hospital. Three LNG-IUS insertions had apparently been followed by spontaneous expulsion, although objective con

CONCLUSION

Plain abdominal X-rays facilitate the determination of whether an LNG-IUS is in the uterine cavity. Therefore, it is important to confirm a device’s location, regardless of whether spontaneous expulsion is suspected, prior to inserting another device.

Core Tip: Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems (LNG-IUS) is the effective against hypermenorrhea and dysmenorrhea. In many cases, like previous devices, we misunderstand that the device can be recognized by ultrasound. In this case, the diagnosis was that there was no device in the uterus, however, there were two devices that were displaced and caused myometrium damage. Plain abdominal X-ray is important to confirm the position of LNG-IUS.

- Citation: Maebayashi A, Kato K, Hayashi N, Nagaishi M, Kawana K. Importance of abdominal X-ray to confirm the position of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(15): 4904-4910

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i15/4904.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i15.4904

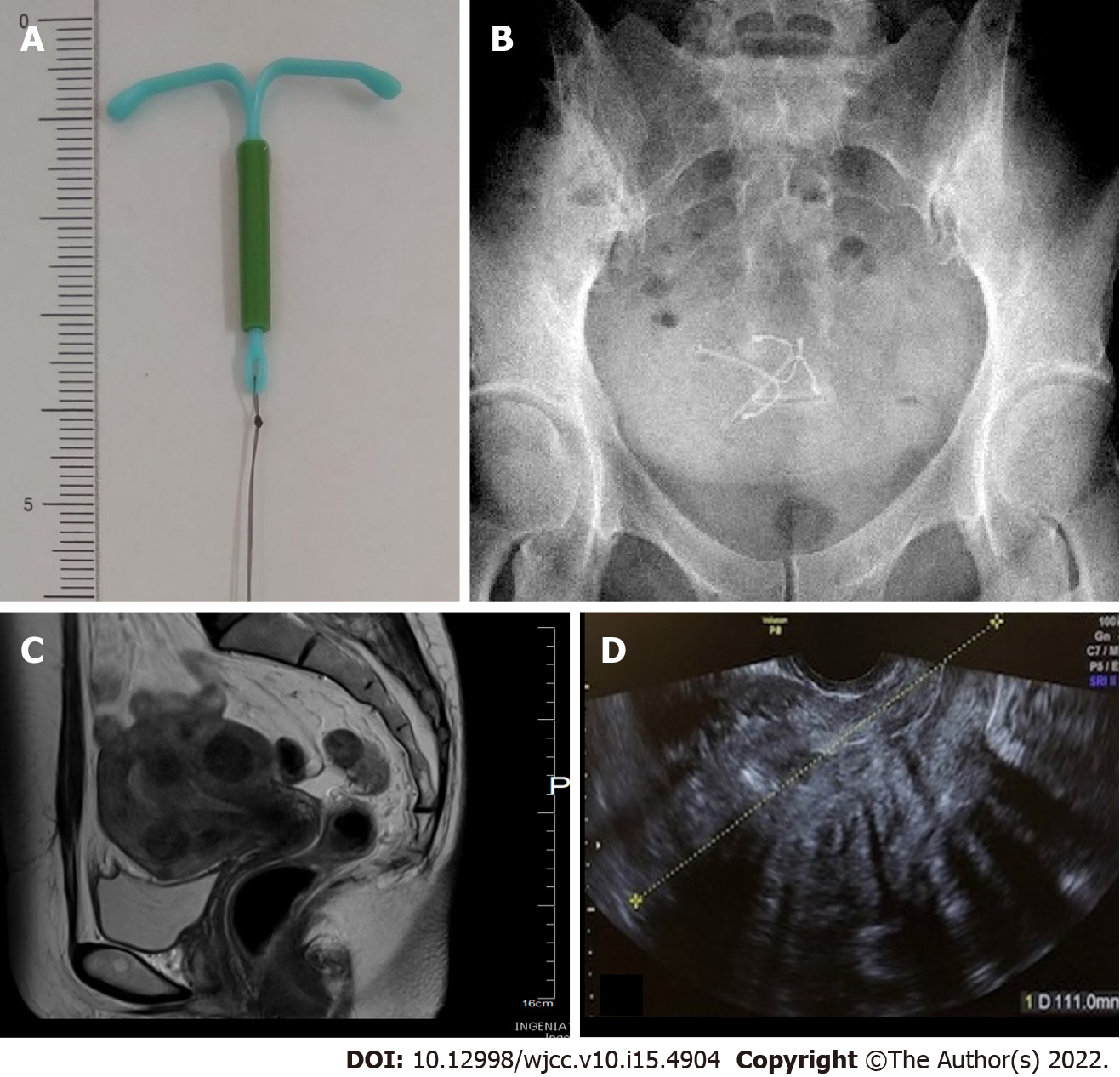

Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) is a T-shaped device matching the morphology of the uterine cavity (Figure 1A). Levonorgestrel contained in the frame is gradually released into the uterus at a rate of 20 μg per day. The released levonorgestrel exerts a local progestin action in the uterus. These devices are now widely available as a treatment for hypermenorrhoea and dysmenorrhea[1,2]. The rate of hypermenorrhoea improvement is reportedly 84%[1]. The rate of dysmenorrhea improved on the visual analog scale from 7.7 ± 1.3 before use to 3.5 ± 1.8 one year after use[2]. LNG-IUS can be inserted into the uterine cavity without anaesthesia in an outpatient setting, and a single application is effective for approximately 5 years. In addition, indications for hypermenorrhoea and dysmenorrhea were approved, insurance coverage was authorized in 2014, and the demand has since been rapidly increasing. However, whether medical personnel have up-to-date knowledge regarding proper use and complications has raised concerns. Uterine perforation is one of the serious complications associated with intrauterine devices (IUDs). The incidence of LNG-IUS uterine perforation is 1.4 per 1000 insertions[3]. Partial perforation is rare but is regarded as an associated risk. Multiple imaging modalities can be used to assess IUDs. Ultrasound is excellent for the initial evaluation. Structurally, an IUD is a T-shaped polyethylene frame with a copper wire or LNG around the stem. Copper wires are opaque and hyperechoic on ultrasound. Ultrasonic identification of copper IUDs is possible due to echogenicity from the copper coils. However, LNG-IUS coated with barium sulfate does not always provide a high echo image. Thus, LNG-IUS can be difficult to detect by ultrasound[4]. In addition, the ultrasound image is unclear in the presence of myoma and intestinal gas artefacts. On X-rays, both barium sulfate and copper are radiopaque and clearly identifiable[5]. The location of the LNG-IUS can thus be confirmed by X-ray. Almost half (48%) of patients with uterine perforation were asymptomatic. IUS were discovered incidentally or following a clinical work-up for symptoms[6]. Case reports have described the appearance of clear symptoms corresponding to IUS perforation of the uterus and entry into the abdominal cavity, which in turn leads to adhesions, intestinal obstruction, and abscess formation. To date, no reports have presented images showing how the displaced device affects the muscle layer or demonstrating partial perforation using a hysteroscope, which may illustrate the process leading to complete uterine perforation. We present a case with partial perforation of the myometrium, which was thought to have been caused by the insertion of a second LNG-IUS, without objective confirmation of the status of the first LNG-IUS by imaging, in response to the patient's self-report of spontaneous expulsion.

The patient was 46 years old and gravida 2, para 2 (2g2p). The patient had been treated for multiple submucosal uterine myomas, hypermenorrhoea, and anaemia by a previous physician starting two years prior to the current presentation.

The previous physician was aware that the patient had undergone prior LNG-IUS insertions and that these devices had been spontaneously expulsed three times over a two-year period. At the time of referral, a third LNG-IUS was inserted; however, the patient was immediately referred to our institution for surgery after both she and the medical professional became aware that spontaneous expulsion along with massive haemorrhage had occurred. Since the previous physician was aware that the LNG-IUS had been inserted and that there had been three prior expulsions of the device, the patient was referred to us based on the assumption that no devices were present in the uterus.

The patient had a medical history of breast cancer at the age of 45, which had been treated by total mastectomy. Postoperative adjuvant therapy was not administered, and the patient is currently receiving follow-up and has not developed recurrence.

There is no family history.

The findings at the time of scheduled hospitalization were as follows: height 168 cm, weight 61 kg, body mass index 21, blood pressure 139/89 mmHg, pulse rate 82 beats/min, respiration rate 20 times/min, and body temperature 36.0 °C. The patient had no abdominal pain and no abnormal bleeding.

Blood test findings were as follows: WBC, 4600/uL; Hb, 11.6 g/dL; Plt, 335000/uL, T-bil, 0.39 mg/dL; AST, 16 U/L; ALT, 13 U/L; LDH, 169 U/L; BUN, 10.2 mg/dL; Cr, 0.65 mg/dL; Na, 141 mEq/L; K, 4.1 mEq/L; Cl, 104 mEq/L; and CRP, 0.01 mg/dL.

During examination at our institution for initial diagnosis, the uterine cavity length was 10 cm, and on transvaginal ultrasound images, multiple uterine myomas were identified, including submucosal uterine myomas up to 4 cm in size (Figure 1C and D). Ultrasound images of the uterine cavity were unclear due to the presence of multiple myomas, and the LNG-IUS could not be visualized inside the uterus. During the speculum examination, the thread for pulling out the LNG-IUS was not found. During pelvic examination and ultrasound, no device was visualized in the uterus+ADs- however, two LNG-IUSs were observed in the pelvis on abdominal plain X-rays prior to surgery (Figure 1A and B), such that both intrauterine LNG-IUSs were suspected to be located in the uterus.

Partial perforation of the uterine myometrium, duplicate insertion of LNG-IUS.

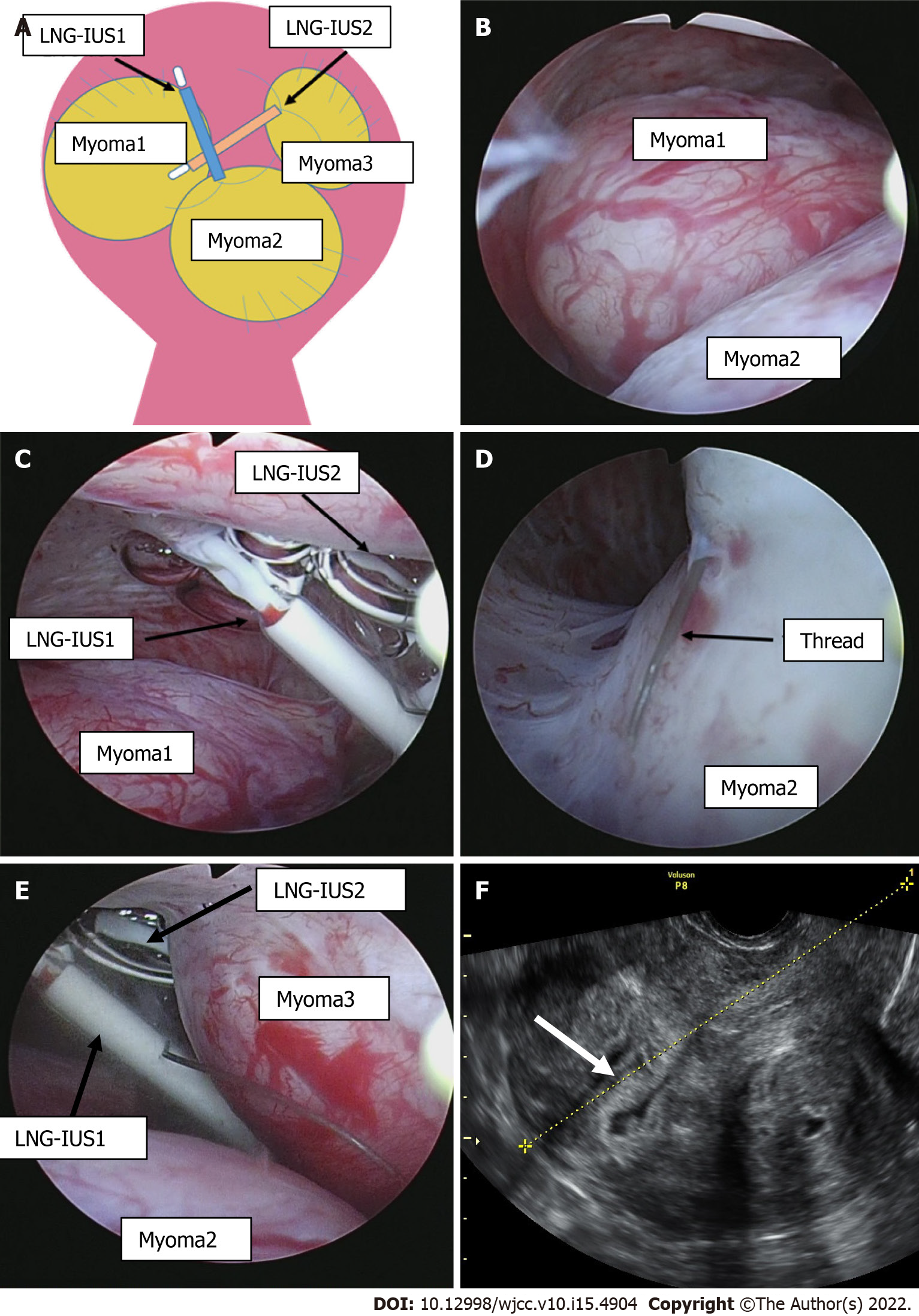

Intrauterine findings at the time of hysteroscopic surgery included an enlarged 4-cm submucosal myoma in the upper right side of the uterine body at a protrusion rate of 70% and an enlarged 4-cm submucosal myoma at a protrusion rate of 90% in the lower part of the uterine body (Figure 2A, B, D and E). In addition, spaces between the uterine myomas and the two LNG-IUS devices and the torn device threads were observed in the fundus of the uterus. The devices had partially perforated the myometrium of the uterine fundus (Figure 2C). The devices were safely removed during surgery using intraoperative biopsy forceps. Then, hysteroscopic myomectomy was performed, and the submucosal myomas were removed. Subsequent hysteroscopy confirmed the absence of bleeding from the perforated section of the myometrium, and the depth was minimal; therefore, a repair operation was not required.

The postoperative course was favourable, and the patient was discharged the day after surgery. Hypermenorrhoea and anaemia showed improvement postoperatively.

LNG-IUS complications include menstrual disorders, ovarian cysts, and pelvic inflammatory diseases, including uterine perforation, which is a very rare complication. At the time of perforation, 48% of patients are asymptomatic. Unexpected pregnancy and abdominal pain are often reported. Because symptoms are mild, the time of onset is unknown for many patients. In those with a clear onset, most symptoms manifest soon after insertion[6]. Some risk factors that are known to be associated with uterine perforation include breastfeeding, recent childbirth, and inappropriate insertion techniques[3], none of which were applicable to this patient. When uterine perforation is suspected because no threads can be found, transvaginal ultrasound is nearly always used. X-rays are required in 75% of patients[7]. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also be options. In most patients, the diagnosis can easily be made using transvaginal ultrasound or X-ray. CT is the optimal method for assessing complications associated with intra-abdominal IUDs, such as visceral perforation, abscess formation, and intestinal obstruction. MRI is rarely used for such evaluations, although this imaging modality can be performed safely[5]. As a result of searching for LNG-IUS, perforation, and migration, there were 6 similar case reports, including this case (Table 1)[8-12]. At the time of diagnosis, 3 patients were asymptomatic, and 3 patients had lower abdominal pain. Ultrasound was performed in 5 cases, and in 4 cases, the patients were diagnosed with an unclear or incorrect LNG-IUS position. Therefore, it was considered that the position of the LNG-IUS could not be determined only by ultrasound. For complete perforation, due to the potential for adhesions, the World Health Organization recommends that perforating IUDs be removed as soon as possible after the diagnosis is confirmed regardless of their type and location[13]. IUDs implanted in the myometrium can be removed during hysteroscopic surgery[14]. In most cases with perforation, the IUD is removed laparoscopically, and laparotomy is rarely performed[3]. Expulsion of IUDs from the uterus is a relatively common complication, occurring in up to 10% of patients[7]. If an IUD is not confirmed by ultrasound and expulsion is suspected, an abdominal pelvic X-ray should be performed to ensure that the IUD is not in the abdominal cavity. Until confirmation, a new IUD should not be inserted[15]. We evaluated the condition of the endometrium by transvaginal ultrasound three months after surgery (Figure 2F). No defects were found in the endometrium, and it was considered that the injury had no effects. In this case, the patient did not wish to become pregnant in the future and did not wish to have a second-look hysteroscope. A second look is recommended within a few months after surgery, especially for patients who wish to become pregnant[16]. The LNG-IUS is a 32-mm T-shaped structure that fits well into normal-sized uterine cavities. However, the arm may slip out without reaching the cornual wedge in patients with an enlarged uterine fundus. In addition, in patients with uterine malformations or submucosal uterine myomas, the arm may hit the myomas, thereby preventing normal insertion. In particular, in patients with multiple submucosal uterine myomas, such as our patient, the device is considered to be aberrantly positioned between myomas or easily expulsed since it is not fixed to the cornual wedge. The length of the uterine cavity increases with exacerbation of uterine myomas and adenomyosis. The thread to remove the LNG-IUS is pulled into the cervix, complicating visualization of the thread during pelvic examination. The same conditions apply to patients with prior gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonist treatment. In these patients, the thread was 2 cm-3 cm longer than usual when a cut was required when inserting LNG-IUSs. The development of products with a greater size selection, including new LNG-IUSs, is expected.

| Author | Year reported | Age (yr) | Para | Indication | Symptom of perforation | Ultrasound finding for LNG-IUS position | Actual position of LNG-IUS | Risk factor |

| Our case | 2021 | 46 | 2 | Hypermenorrhea | None | Location cannot be diagnosed due to myomas | In the uterus (partial perforation) | Submucosal myomas |

| Pappas et al[8] | 2009 | 33 | 2 | Hypermenorrhea | Abdominal pain | Unknown | In the anterior abdominal wall with omentum | After endometrial ablation |

| Ferson et al[9] | 2016 | 46 | 1 | Contraception | None | In the upper endometrial cavity | The straight arm in the uterus, T sharped arms in the abdominal cavity | Prolonged steroid use |

| Howard et al[10] | 2017 | 31 | 2 | Contraception | None | In the uterus | In the cul-de-sac | Insertion at 6 wk after vaginal delivery |

| Saeki et al[11] | 2019 | 29 | 1 | Dysmenorrhea | Abdominal pain | Unknown | In the retroperitoneum | After conization |

| Makena et al[12] | 2021 | 34 | 1 | Contraception | Abdominal pain | No devices in the uterus | In the left tube | Insertion at 8 wk after vaginal delivery |

Plain X-rays are recommended if the thread for removal cannot be detected during the examination of patients with LNG-IUSs. In particular, the indications, insertion techniques, contraindications, and follow-up methods are often poorly understood and executed in countries where LNG-IUSs have only recently been introduced, and thus, caution should be exercised.

The authors thank Bierta B for her contribution to the language editing of this manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Le A, China; Tuo BG, China S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Kaunitz AM, Bissonnette F, Monteiro I, Lukkari-Lax E, Muysers C, Jensen JT. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system or medroxyprogesterone for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:625-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lockhat FB, Emembolu JO, Konje JC. The efficacy, side-effects and continuation rates in women with symptomatic endometriosis undergoing treatment with an intra-uterine administered progestogen (levonorgestrel): a 3 year follow-up. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:789-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, Minh TD. Risk of uterine perforation with levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices. Contraception. 2015;91:274-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Moschos E, Twickler DM. Does the type of intrauterine device affect conspicuity on 2D and 3D ultrasound? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:1439-1443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Boortz HE, Margolis DJ, Ragavendra N, Patel MK, Kadell BM. Migration of intrauterine devices: radiologic findings and implications for patient care. Radiographics. 2012;32:335-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mosley FR, Shahi N, Kurer MA. Elective surgical removal of migrated intrauterine contraceptive devices from within the peritoneal cavity: a comparison between open and laparoscopic removal. JSLS. 2012;16:236-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mülayim B, Mülayim S, Celik NY. A lost intrauterine device. Guess where we found it and how it happened? Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2006;11:47-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pappas A, Shambhu S, Phillips K, Guthrie K. A levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system embedded in the omentum in a woman with abdominal pain: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:9301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ferguson CA, Costescu D, Jamieson MA, Jong L. Transmural migration and perforation of a levonorgestrel intrauterine system: a case report and review of the literature. Contraception. 2016;93:81-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Howard DL, Beasley LM. Pregnant with a perforated levonorgestrel intrauterine system and visible threads at the cervical os. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shinichiro S, Wakimoto Y, Kamei H, Fukui A, Shibahara H. Removal of a Retroperitoneal Foreign Body by Laparoscopic Surgery. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2019;8:86-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Makena D, Gichere I, Warfa K. Levonorgestrel intrauterine system embedded within tubal ectopic pregnancy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2021;15:107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mechanism of action, safety and efficacy of intrauterine devices. Report of a WHO Scientific Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1987;753:1-91. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Soydinc HE, Evsen MS, Caça F, Sak ME, Taner MZ, Sak S. Translocated intrauterine contraceptive device: experiences of two medical centers with risk factors and the need for surgical treatment. J Reprod Med. 2013;58:234-240. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Zakin D, Stern WZ, Rosenblatt R. Complete and partial uterine perforation and embedding following insertion of intrauterine devices. II. Diagnostic methods, prevention, and management. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1981;36:401-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sebbag L, Even M, Fay S, Naoura I, Revaux A, Carbonnel M, Pirtea P, de Ziegler D, Ayoubi JM. Early Second-Look Hysteroscopy: Prevention and Treatment of Intrauterine Post-surgical Adhesions. Front Surg. 2019;6:50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |