Published online May 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i15.4911

Peer-review started: September 18, 2021

First decision: October 27, 2021

Revised: November 7, 2021

Accepted: April 3, 2022

Article in press: April 3, 2022

Published online: May 26, 2022

Processing time: 248 Days and 5.8 Hours

The indwelling nasogastric tube is commonly used for supplying enteral nutrition to patients who are unable to feed themselves, and accurate positioning is essential in the indwelling nasogastric tube in the body of the aforementioned patients. In clinical practice, abdominal radiography, auscultation, and clinical determination of the pH of the gastric juice are routinely used by medical personnel to determine the position of the tube; however, those treatments have proved limitations in specific cases. There are few case reports on the precise positioning of the nasogastric tube in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), for whom a supply of necessary nutrition support is significant throughout the process of treatment.

A 79-year-old patient, diagnosed with COVID-19 at the stage of combined syndromes with severe bacterial lung infection, respiratory failure, multiple co-morbidities, and a poor nutritional status, was presented to us and required an indwelling nasogastric tube for enteral nutrition support. After pre-treatment assessments including observation of the patient’s nasal feeding status and examination of the nasal septal deviation, inflammation, obstruction, nasal leakage of cerebrospinal fluid, and other disorders that might render intubation inappropriate, we measured and marked the length of the nasogastric tube to be placed and delivered the tube to the intended length in the standard manner. Then further scrutiny was conducted to ensure that the tube was not coiled in the mouth, and gentle movements were made to avoid damage to the esophageal mucosa. However, back draw of the gastric juice using an empty needle failed, and the stethoscope could not be used for auscultation due to the specific condition presented by the internal organs of the patient, and the end of the tube was placed in saline with no bubbles spilling out. Therefore, it was not possible to determine whether the nasogastric tube was placed exactly in the stomach and no nutrient infusion was performed for the time being. Subsequently, the ultrasound probe was utilized to view the condition of the patient’s stomach, where the nasogastric tube was found to be translucent and running parallel to the esophagus shaped as “=”. The pre-conditions were achieved and 100 mL nutritional fluid was fed to the patient, who did not experience any discomfort throughout the procedure. His vital signs were stable with no adverse effects.

We achieved successfully used ultrasound to position the nasogastric tube in a 79-year-old patient with COVID-19. The repeatable ultrasound application does not involve radiation and causes less disturbance in the neck, making it advantageous for rapid positioning of the nasogastric tube and worthy of clinical promotion and application.

Core Tip: External nutrition supply via nasogastric tube is crucial for patients who are unable to feed themselves to sustain physical functions. The traditional methods of indwelling nasogastric tube in a patient’s body has limitations in medical treatment. Herein, we present a rare case of application of ultrasonic localization of a nasogastric tube in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019, in whom traditional methods failed to indicate successful indwelling. This case highlights the importance of appropriate application of ultrasonic localization as a supplementary method to ensure that the nasogastric tube has been properly placed in the patient’s stomach.

- Citation: Zhu XJ, Liu SX, Li QT, Jiang YJ. Bedside ultrasonic localization of the nasogastric tube in a patient with severe COVID-19: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(15): 4911-4916

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i15/4911.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i15.4911

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a novel acute respiratory infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. COVID-19 is characterized by a rapid rate of transmission and susceptibility of the population. The disease usually manifests with symptoms of fever, dry cough, and fatigue. In severe cases, patients may experience dyspnea and/or hypoxemia in the week following onset. Severe COVID-19 can rapidly progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome, septic shock, irreversible metabolic acidosis, coagulation dysfunction, and multiple organ failure[1-2]. Due to reduced food intake, increased energy consumption, and impaired anabolic functioning, the incidence of malnutrition in these patients can reach 25% to 65%[3], and may adversely affect patient outcomes. Early enteral nutrition is considered one of the active treatment measures for critically ill patients as it can reduce the severity of the disease and the incidence of complications, as well as shorten hospitalization and improve patient prognosis[4-6].

The indwelling nasogastric tube is the most commonly used method for supplying enteral nutrition. The tube requires accurate positioning. Traditional methods include extraction and examination of the patient’s gastric juice, followed by determination of the sound of air passing through the liquid. The tube can also be positioned via using ultrasound and X-rays. Under COVID-19 and Level 3 protection requirements, the use of bedside ultrasound is advantageous in situations where the stethoscope cannot be used, and it does not require extensive human and material resources.

A 79-year-old patient was admitted to the Department of Critical Care Medicine, the COVID-19 Specialist Hospital of Wuhan Taikang Tongji Hospital (Wuhan, China), with severe COVID-19, coronary atherosclerotic heart disease, and cerebral infarction in March 2020.

The patient had developed fever without obvious inducement 7 wk prior, with a body temperature reaching 38.5 °C, fatigue and anorexia. The body temperature then fluctuated between 36.5 °C and 38 °C. Since the onset of the disease, the patient had had no contact with COVID-19 patients. At the time of admission, the patient was severely ill, complicated by pulmonary bacterial infection, respiratory failure, co-morbid diseases, and poor nutrition. The patient required a nasogastric tube for enteral nutritional support, which was inserted in the hospital under medical supervision.

The patient had a history of cerebral infarction and recovered through drug treatment without obvious impairment of either action or speech.

There was no history of COVID-19 or other medical issues in the patient‘s family.

On arrival in the department, the nutritional status of the patient and the feasibility of nasal feeding of the patient were assessed. In addition, the patient was investigated for nasal septum deviation, nasal inflammation, obstruction, cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea, and other conditions that would render indwelling unsuitable.

After admission, laboratory examinations were conducted and the patient received anti-infection and antiviral treatment, together with treatments for improving cardiac function, blood transfusions, and other symptomatic treatments.

An initial imaging evaluation with brain computed tomography (CT) scan suggested multiple small punctate hypodense foci next to the lateral ventricles bilaterally, with ischemic changes and a high probability of acute ischemic stroke; the chest CT revealed scattered patches and cloudy fuzzy shadows in both lungs, and the patient was considered to have been infected with COVID-19.

The patient was severely ill, complicated by pulmonary bacterial infection, respiratory failure, co-morbid diseases, and poor nutrition. The patient required a nasogastric tube for enteral nutritional support.

The required length of the nasogastric tube was determined and marked during physical examination. Then the tube was inserted to the predetermined length by the routine procedure. The nasogastric tube was gently placed to avoid damaging the esophageal mucosa and to ensure that the tube was not coiled in the mouth.

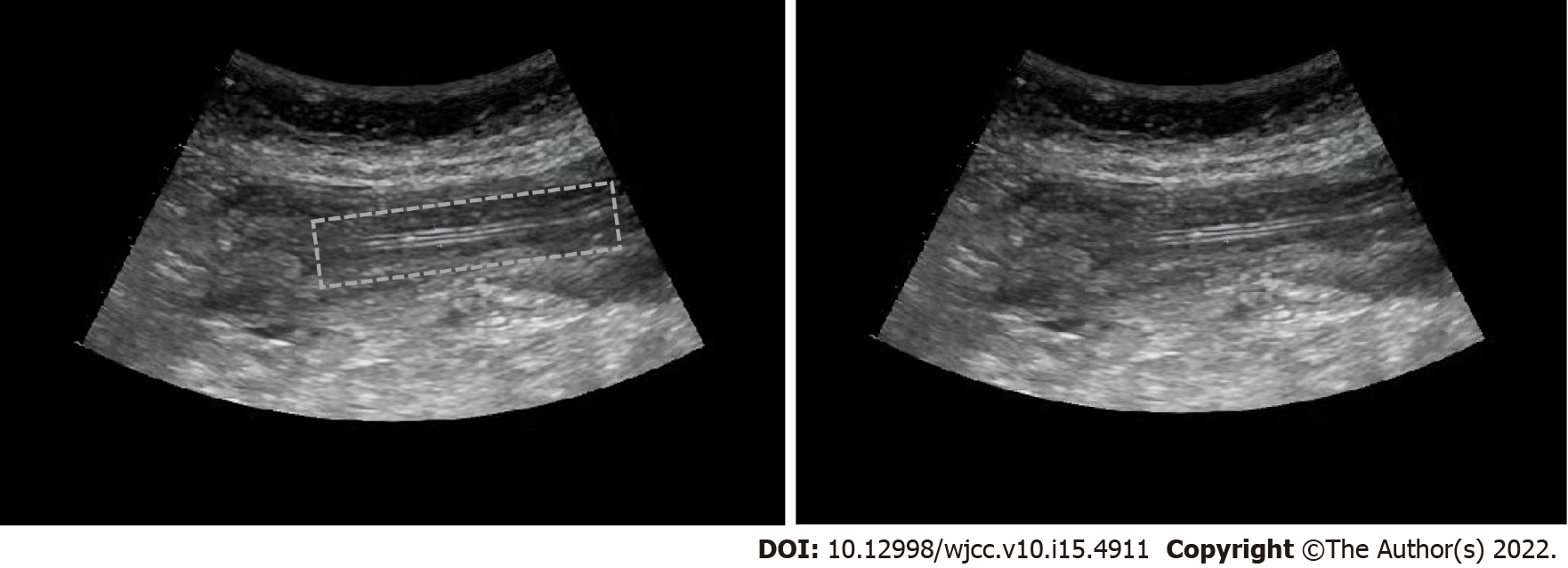

The gastric juice was not able to be extracted using an empty needle. Meanwhile, due to the particular circumstances, the stethoscope could not be used for auscultation. The end of the nasogastric tube was placed in normal saline solution without bubble overflow. As a result, it was unknown whether the tube was in the stomach, and no nutrient solution was injected. The tube position was then examined via ultrasound. The ultrasonic probe could clearly identify the circular nasogastric tube and comet tail sign through the cross-section after the esophageal inlet. On examination of the longitudinal section of the esophagus, it was observed that the nasogastric tube was running parallel in the esophagus, seen as two parallel transparent hyperechoic images in the shape of “=” (Figure 1). This indicated the position of the nasogastric tube, and then 100 mL nutrient solution was injected. The patient suffered no discomfort and the vital signs were stable without adverse reactions.

Conventional auscultation: Conventionally, a stethoscope with a 50 mL disposable syringe is used for auscultation. Initially, 20 to 30 mL of air is rapidly injected, followed by repeated auscultation in the abdomen. Detection of a high-profile sound of air passing through the liquid indicates that the tube is located in the stomach.

Extraction of gastric juice: A sterile syringe is connected to the end of the tube to determine whether gastric juice can be extracted.

Overflowing bubbles: The end of the tube is placed in a bowl filled with cold boiled water or normal saline to determine the presence of bubbles.

Plain X-ray abdominal radiograph examination: A bedside X-ray film is taken within 2 h after insertion of the nasogastric tube, and mobile digital radiography is performed. The radiologist obtains anterior-posterior chest images according to the specifications and completes the film reading and the report.

Ultrasonic localization: The gas status in the patient's stomach should be identified. If a strong echo appears with too much gas, this may affect the judgment of the result. Thus, it is necessary to extract the gas before exploration. After inserting the nasogastric tube, the circular tube and the comet tail sign were clearly seen in the transverse section after the ultrasonic probe passed through the esophageal inlet. In the longitudinal section, the nasogastric tube was found to run parallel in the esophagus, seen as two parallel transparent hyperechoic images in the shape of “=”.

Auscultation: When air is injected into the nasogastric tube, the sound of air passing through liquid is strongly discernable on auscultation. The sound of air injected into the trachea and pleural cavity is not easy to distinguish from that injected into the stomach. Therefore, it is not easy to accurately distinguish the location of the nasogastric tube by auscultation, and some patients may present with clinical manifestations such as choking and decreased oxygen saturation[7]. Given that COVID-19 is a Class B infectious disease and can be transmitted by contact and droplets, medical personnel need Level 3 protection when entering the Red zone to reduce the risk of infection. Additionally, a stethoscope used in the Red zone becomes a contaminated object, and viruses and other pollutants may attach to the surface. Because of this, the stethoscope should not come into direct contact with the body surface of the medical personnel. In addition, the senses, including sensation in the limbs, and especially hearing, are greatly weakened, which adversely affect the accuracy of judgment and auscultation. Therefore, conventional auscultation in patients with COVID-19 increases the risk of exposure of medical personnel to the virus and is also difficult to implement.

Extraction of gastric juice: Clinically, we found that most critical patients with COVID-19 are unable to eat. After insertion of the nasogastric tube, adhesion and reverse folding of the tube may occur, resulting in too little liquid in the stomach. As a result, it is impossible to locate and extract the nasogastric contents accurately, thus limiting the efficacy of the gastric juice extraction method.

Bubble overflow method: The end of the tube is placed in a bowl filled with normal saline to determine overflow of the bubbles. However, bubble overflow may only indicate that the tube is in the airway and is not able to detect whether it is in the stomach. It is also not recommended for routine use as it may increase the risk of inadvertent aspiration when the patient is aspirating[8].

Plain abdominal X-ray examination: The determination of nasogastric tube positioning by bedside radiography is the gold standard for determining accurate positioning; however, this has the disadvantages of high levels of radiation and the length of the procedure, making it unsuitable for repeated use[9-10]. In addition, with COVID-19, all medical personnel are required to use Grade 3 protection, and the removal of instruments from the radiology department not only increases the workload for the radiology personnel but also affects the timing and efficiency of the treatment. Also, when performing abdominal plain X-rays for severely ill patients, usually at least three medical personnel are required to move and place the body in position, resulting in increased physical exertion. Furthermore, when moving, the radius of action would tend to increase, as would the amount of perspiration from the medical personnel, which would tend to reduce the effectiveness of the protective clothing and thus increase the risk of exposure. For patients with severe disease, there are usually many tubes attached. The risk of tube slippage would increase and thus the quality of nursing would tend to be reduced during movement.

Ultrasonic localization: Studies have reported a 100% accuracy rate of bedside ultrasound in determining the success of gastric tube placement[11].Ultrasound is a non-invasive procedure with the advantages of repeatability and a lack of radiation[12]. For unconscious patients, bedside ultrasound positioning is safe and can be carried out with other diagnostic and treatment measures without affecting mechanical ventilation, delaying treatment, and transferring risk. Furthermore, bedside ultrasound has been reported to intuitively indicate the patient's condition and pathology, improve the precision of clinical diagnosis, guide the positioning of intubation and puncture operation and therefore reduces damage to the laryngeal mucosa caused by repeated manipulation[13]. Moreover, given its intuitive, fast, accurate, and convenient features, bedside ultrasound has been applied as a standard tool for monitoring and evaluating severely ill patients and positioning of punctures in intensive care unit, anesthesia, and emergency departments in numerous countries[14-16]. It is not difficult to locate the position of the nasogastric tube if the thyroid and tracheal positions are located. In addition, there is less disturbance to the neck. If the position of the nasogastric tube cannot be determined due to pseudo-interference or other causes, about 20 mL of air should be quickly injected into the tube. This would result in the formation of a prominent gas reflection plane, and the position of the tube would be visible as a strong strip echo under ultrasound. The intensive care unit of our department has an ultrasound machine to reduce the increased workload caused by repeated demand. This instrument is always available to facilitate the timely diagnosis and treatment of patients.

Accurate positioning of the nasogastric tube in severely ill patients with COVID-19 using bedside ultrasound could reduce both the risk of viral exposure to medical personnel and the clinical workload, as well as avoid X-ray radiation. Bedside ultrasound localization of the nasogastric tube produces immediate accurate results, thus gaining valuable time for clinical treatment and effectively improving both the potential success of the treatment and prognosis of the patient. It is thus worthy of clinical promotion and application.

The authors would like to thank the patient and his family for their cooperation in relation to this case report.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Nursing

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ilkafah I, Indonesia; Ullah K, Pakistan S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239-1242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11409] [Cited by in RCA: 11601] [Article Influence: 1933.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review. JAMA. 2020;324:782-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2691] [Cited by in RCA: 3235] [Article Influence: 539.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zhu M, Wu WR. Enteral nutrition. Beijing: People’s Health Publishing House, 2002: 377-380.. |

| 4. | Guo YB, Liu Y, Ma J, Cai Y, Jiang XM, Zhang H. Effect of early enteral nutrition support for the management of acute severe pancreatitis: A protocol of systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e21569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ge W, Wei W, Shuang P, Yan-Xia Z, Ling L. Nasointestinal Tube in Mechanical Ventilation Patients is More Advantageous. Open Med (Wars). 2019;14:426-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jiang Z, Wen C, Wang C, Zhao Z, Bo L, Wan X, Deng X. Plasma metabolomics of early parenteral nutrition followed with enteral nutrition in pancreatic surgery patients. Sci Rep. 2019;9:18846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tsung JW, Fenster D, Kessler DO, Novik J. Dynamic anatomic relationship of the esophagus and trachea on sonography: implications for endotracheal tube confirmation in children. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:1365-1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Roberts S, Echeverria P, Gabriel SA. Devices and techniques for bedside enteral feeding tube placement. Nutr Clin Pract. 2007;22:412-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Motz P, Von Saint Andre Von Arnim A, Iyer RS, Chabra S, Likes M, Dighe M. Point-of-care ultrasound for peripherally inserted central catheter monitoring: a pilot study. J Perinat Med. 2019;47:991-996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Telang N, Sharma D, Pratap OT, Kandraju H, Murki S. Use of real-time ultrasound for locating tip position in neonates undergoing peripherally inserted central catheter insertion: A pilot study. Indian J Med Res. 2017;145:373-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zatelli M, Vezzali N. 4-Point ultrasonography to confirm the correct position of the nasogastric tube in 114 critically ill patients. J Ultrasound. 2017;20:53-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Heidegger CP, Graf S, Perneger T, Genton L, Oshima T, Pichard C. The burden of diarrhea in the intensive care unit (ICU-BD). A survey and observational study of the caregivers' opinions and workload. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;59:163-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hirose T, Shimizu K, Ogura H, Tasaki O, Hamasaki T, Yamano S, Ohnishi M, Kuwagata Y, Shimazu T. Altered balance of the aminogram in patients with sepsis - the relation to mortality. Clin Nutr. 2014;33:179-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lichtenstein D. Fluid administration limited by lung sonography: the place of lung ultrasound in assessment of acute circulatory failure (the FALLS-protocol). Expert Rev Respir Med. 2012;6:155-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang G, Ji X, Xu Y, Xiang X. Lung ultrasound: a promising tool to monitor ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2016;20:320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Xirouchaki N, Kondili E, Prinianakis G, Malliotakis P, Georgopoulos D. Impact of lung ultrasound on clinical decision making in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:57-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |