Published online Dec 25, 2025. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v14.i4.112590

Revised: October 25, 2025

Accepted: December 16, 2025

Published online: December 25, 2025

Processing time: 147 Days and 14.9 Hours

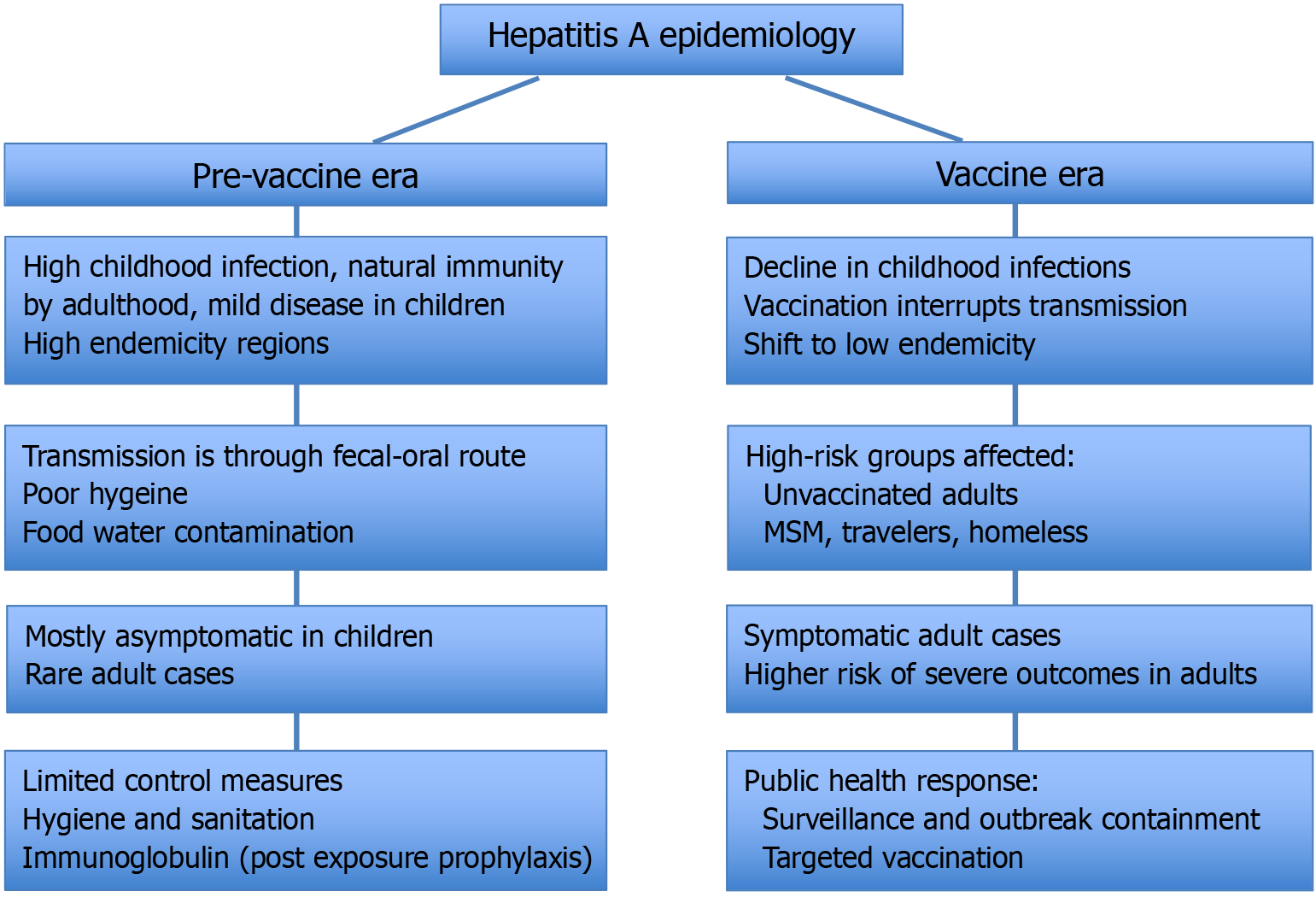

Hepatitis A, a vaccine-preventable liver infection caused by the hepatitis A virus, is undergoing significant epidemiological shifts worldwide. Traditionally con

Core Tip: The epidemiology of hepatitis A is undergoing a profound shift, driven by changing socioeconomic conditions, living standards worldwide and ongoing viral evolution. This has resulted in a shift in epidemiology, with decreasing exposure to the virus among children, leaving adolescent and adult populations susceptible to more clinically significant disease. This change leads to more severe disease in older populations, highlighting the need for updated vaccination guidelines targeting susceptible adults, vigilant surveillance to monitor viral evolution and antigenic variation, and strengthened public health measures including enhanced hygiene and outbreak prevention strategies.

- Citation: Majeed AA, Sarfraz M, Butt AS. Evolving trends in hepatitis A epidemiology: Shifting patterns, emerging risks, and future strategies. World J Virol 2025; 14(4): 112590

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3249/full/v14/i4/112590.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5501/wjv.v14.i4.112590

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) affects tens of millions of people and continues to be a significant global health concern, with recent estimates indicating approximately 14 million cases and 28000 deaths annually, according to a 2024 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Health Organization (WHO) review of viral foodborne diseases[1]. This marks a notable rise from the 7134 deaths reported in 2016, highlighting the enduring and possibly increasing burden of HAV in both developing and developed settings[2]. Despite the availability of an effective vaccine for several decades now and ability to control viral spread with simple measures such as providing access to sanitation and food hygiene measures, one review estimates an increase in global incident cases from 1990 to 2019 by 13.9%, from 139.54 million to 158.94 million, with persistence of high endemicity levels in certain parts of the developing world and sporadic outbreaks occurring even in the developed world, even as the world transforms in other ways with medical and scientific breakthroughs[3]. The goal of eliminating viral hepatitis by 2030 was put forward by WHO in 2016, and much needs to be done to achieve this[4].

HAV is a non-enveloped, icosahedral virus with a linear, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome, classified under the Picornaviridae family[5]. The Picornaviridae family includes several medically important viruses such as poliovirus, echovirus, rhinovirus, and coxsackievirus[6]. It is transmitted via the fecal-oral route, often through contaminated shellfish which includes oysters, clams and other filter feeding molluscan shellfish[7]. Although seafood continues to be a common source, a growing number of cases are now associated with imported frozen products such as fruits, vegetables, and ready-to-eat meals[3]. International travellers from low-endemic regions are at increased risk of hepatitis A infection when visiting high-endemic areas, particularly if they lack prior immunity to the virus[8]. Additionally, person-to-person transmission is prominent in high-risk settings such as nursing homes, prisoners and among men who have sex with men[9,10]. Laboratory diagnosis relies on the detection of anti-HAV immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies, which indicate recent infection. Anti-HAV IgG antibodies appear soon after and confer lifelong immunity[11]. In suspected cases with initially negative results, repeat testing after 7-10 days is recommended to exclude delayed seroconversion. In selected cases, HAV RNA detection by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction in serum or stool can provide early confirmation of infection, especially during the seronegative window period, and is also useful for outbreak tracing and identifying transmission chains. Molecular assays further allow genotype determination most commonly genotypes IA, IB, and IIIA in human infections which contributes to understanding viral origin, regional circulation, and epidemiologic links. False-positive IgM results may occasionally occur in autoimmune or other viral conditions, so molecular confirmation may be warranted in equivocal cases[12]. HAV infection is typically asymptomatic in children but often presents with symptoms in adults which includes fever, malaise, anorexia, abdominal discomfort and jaundice[13]. After an incubation period of about 28 days (range 15-50 days), the illness typically progresses through prodromal, icteric, and convalescent phases. The clinical spectrum ranges from mild, anicteric illness to severe acute hepatitis, with most patients achieving complete recovery[14]. However, in 15%-20% of individuals, a cholestatic or relapsing form may develop, characterized by prolonged jaundice, pruritus, and recurrent elevations of aminotransferases after apparent recovery[15]. In rare cases, especially among individuals with pre-existing chronic liver diseases or co-infection with hepatitis B virus, HAV can lead to fulminant hepatic failure[16]. Extrahepatic manifestations, though uncommon, have been reported and include vasculitis, cryoglobulinemia, and thrombocytopenia[17]. Table 1 clearly demonstrates clinical course and manifestations of HAV Infection[14].

| Phase | Approximate duration | Key clinical manifestations | Laboratory/virological findings |

| Incubation | 2-6 weeks (mean 28 days) | Asymptomatic | HAV replication in liver; high virus in stool and blood; normal ALT |

| Prodromal (pre-icteric) | 3-10 days | Fatigue, anorexia, nausea, low-grade fever, right upper quadrant discomfort, diarrhea in children | Rapid ALT/AST rise (> 1000 IU/L); HAV in stool; start of IgM anti-HAV appearance |

| Icteric phase | 1-3 weeks | Jaundice, dark urine, pale stools, pruritus; fever and malaise subside | Peak ALT/AST; elevated bilirubin; IgM anti-HAV positive |

| Convalescent/recovery | Several weeks-months | Gradual improvement; residual fatigue | Enzyme levels normalize; IgM declines; IgG persists lifelong |

The case fatality rate of acute hepatitis A varies significantly with age with approximately 0.1% in children and reaching 2.1% in adults aged 40 years and older. In Africa, however, the case fatality rate tends to be higher in adults aged 50 years and above, it increases substantially, ranging from 1.8% to 5.4%. These age-related disparities in mortality highlight the increased vulnerability of older adults and the critical importance of early vaccination and targeted public health interventions, especially in regions with limited healthcare infrastructure[18,19]. In the United States, between 2016 and 2022, more than 44600 cases and over 400 deaths were recorded during large-scale HAV outbreaks across multiple states[20]. This underscores the continued threat posed by communicable diseases, including hepatitis A, which remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality especially in resource-limited settings[21]. This review explores the changing global epidemiology of hepatitis A, recent outbreak patterns, key risk factors, critical need for improved surveillance, expanded vaccination programs, emergence of new viral strains and targeted preventive stratergies.

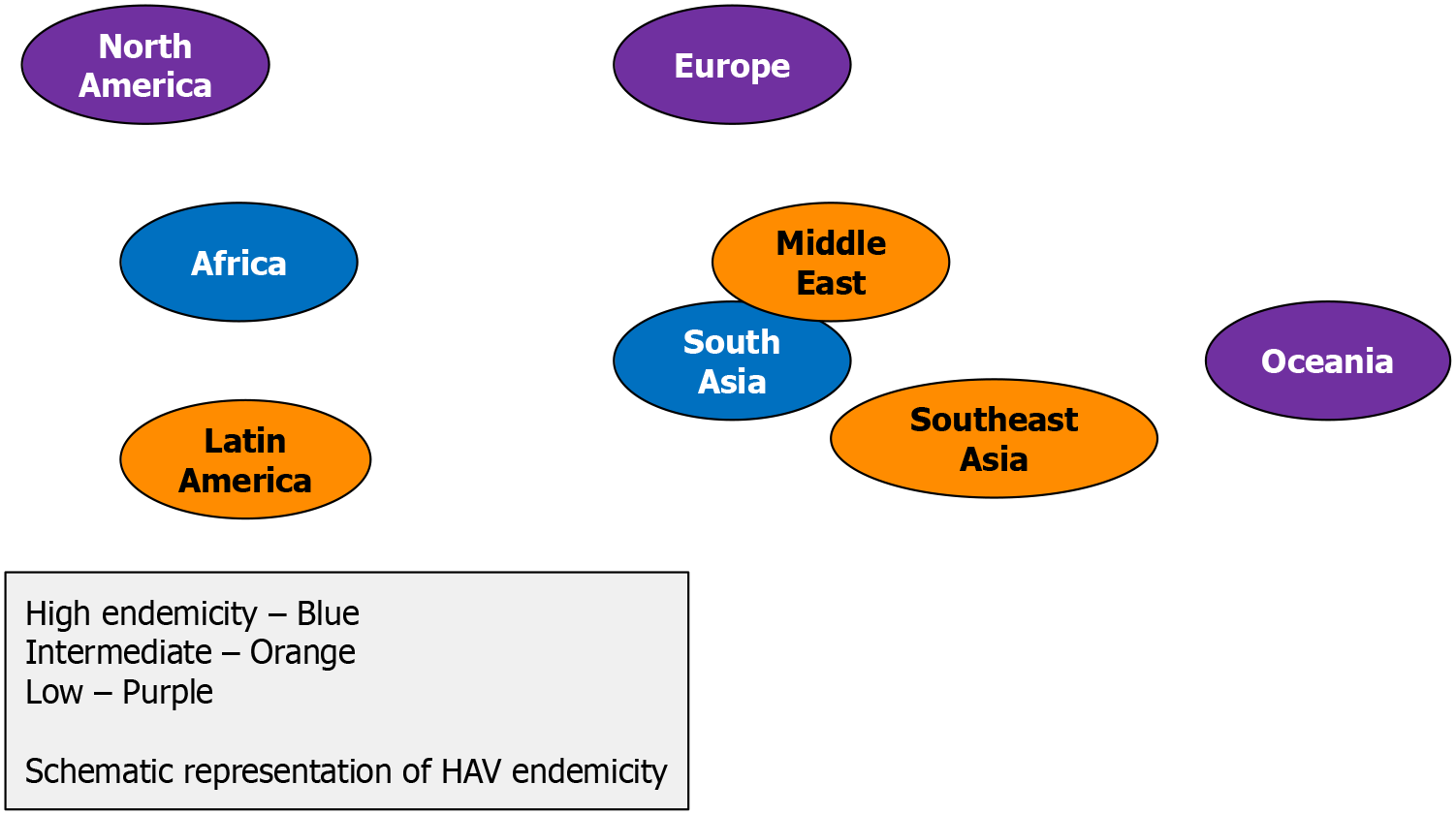

Hepatitis A existed worldwide, with endemicity levels correlating with socioeconomic status and sanitation[22]. The geographical distribution for hepatitis A was split into high, intermediate, low, and very low endemicity areas according to seroprevalence rates of hepatitis A. The WHO classifies endemicity levels based on the age-specific seroprevalence of HAV in the general population (Table 2)[23].

| Endemicity level | Age-specific seroprevalence |

| High | 90% by 10 years of age |

| Intermediate | 50% by 15 years, with < 90% by 10 years |

| Low | 50% by 30 years |

| Very low | < 50% by 30 years |

In areas of high endemicity, lower overall disease rates and rare outbreaks of HAV have been reported in adult populations since most infections occur in early childhood when asymptomatic infection predominates, with almost the entire population having been infected before reaching adolescence[24,25]. Less frequent infection rates were observed in regions of moderate endemicity, due to improved sanitation and living standards, increasing in average age of infection[26]. Paradoxically, these regions would face a heightened risk of large hepatitis A outbreaks because of a larger po

The first hepatitis A vaccines, licensed for use in the United States in 1992 and 1993 respectively, were the following inactivated single antigen vaccines: (1) HAVRIX (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium); and (2) VAQTA (Merck and Company Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ, United States)[33,34]. Subsequently, more inactivated and live hepatitis vaccines have been developed and licensed[35]. In addition, combination vaccines containing hepatitis A and B (Twinrix™ and Bilive™) and another containing typhoid and hepatitis A (Viatim®) have also been licensed[36]. Strategies have included targeted vaccination among high-risk groups, regional childhood vaccination, and universal childhood vaccination[35]. A dynamic modelling study demonstrated that universal hepatitis A vaccination is cost-effective in both developed (United States) and developing (Rio de Janeiro) settings, significantly reducing disease incidence and increasing quality-adjusted life years. These findings support the adoption and expansion of universal vaccination policies globally[37]. As of May 2019, 28 countries had introduced routine universal hepatitis A vaccination in children, with two more countries planning the inclusion according to a WHO report[38]. These include 10 countries in the Americas, 5 in the Eastern Mediterranean, 8 in Europe, and 5 in the Western Pacific[38]. According to WHO position paper in October 2022, hepatitis A vaccination strategies should be tailored based on a country's endemicity level, with universal childhood vaccination recommended in transitioning countries, targeted vaccination in low-endemic areas, and thorough risk benefit analyses before implementation in highly endemic regions. High-risk groups including travellers, men who have sex with men, people who inject drugs, migrants, and those with chronic liver disease should be prio

| Vaccine policy | Cost coverage | Equity/operational notes | Ref. |

| Routine childhood vaccination; targeted adult vaccination (VFC program) | Free under VFC; OOP for adults without insurance | Outbreaks in PEH and drug-using adults; gaps in adult uptake | Nelson et al[41], United States |

| Targeted (indigenous, travelers, PEH) | Provincial programs; partial coverage | Uneven uptake across provinces | Palaisy[42], Canada |

| Universal childhood vaccination (≥ 12 months) | Government-funded | High coverage; regional disparities in remote areas | Brito and Souto[43], Brazil |

| Integrated in national schedule (since 2023) | Free public sector | Rapid rollout post-urban outbreaks | Guzman-Holst et al[44], Mexico |

| Universal single-dose schedule | Government-funded | Successful herd immunity; sustained low incidence | Flichman et al[45], Argentina |

| Targeted (travelers, men who have sex with men, PEH) | National Health Service covers high-risk groups | Limited adult awareness | Johnson et al[46], United Kingdom |

| Recommended (travelers, men who have sex with men, laboratory staff) | Reimbursed by insurance | Stable low incidence; high cost limits universal rollout | Szucs[47], Germany |

| Universal since 2003 in several regions | Government-funded | Decline in hepatitis A virus cases; regional autonomy causes inconsistency | Bechini et al[48], Italy |

| Targeted vaccination | Regional funding | Good outbreak response; inequity across regions | Urbiztondo et al[49], Spain |

| Included in routine childhood schedule in 2008 | Government-funded | High coverage; rare outbreaks | Ryani[50], Saudi Arabia |

| Universal childhood (since 2011) | Fully subsidized | Excellent coverage nationwide | Yigit and Kalayci[51], Turkey |

| Targeted vaccination (private market) | Mostly OOP | High-cost limits uptake; growing private sector use | Shah et al[52], India |

| Targeted; not yet universal | OOP except high-risk groups | Declining seroprevalence; debate on adding to National Immunisation Programme | Poovorawan et al[53], Thailand |

| Universal childhood vaccination since 2008 | Government-funded | Dramatic incidence decline; urban-rural gap remains | Yan et al[54], China |

| Targeted (travelers, men who have sex with men) | OOP | Low uptake; periodic import-linked outbreaks | Kanda et al[12], Japan |

| Targeted (travelers, laboratory staff) | OOP | Low uptake due to cost; increasing adult outbreaks | Patterson et al[55], South Africa |

| Not routine; private market only | OOP | High endemicity; vaccine not prioritized | Ahmed and Nashwan[56], Pakistan |

With the introduction of childhood vaccinations for hepatitis A and improved sanitation, there has been a global trend of decrease in average seroprevalence rates, particularly among children[57]. The seroprevalence rates correlate with socioeconomic status and access to clean water and sanitation[57]. With the implementation of routine childhood hepatitis A vaccination since 1999 in high-risk United States areas significantly reduced infection rates[58]. Notably, Poovorawan et al[59] observed a declining HAV seroprevalence among Thai youth, reflecting increased susceptibility due to reduced natural exposure highlighting the risk of outbreaks in unvaccinated cohorts. As sanitation improved, several countries began transitioning to intermediate endemicity, delaying exposure to adolescence or adulthood when sym

Jacobsen et al[62] demonstrated that older ages indicate less childhood exposure and a lower endemicity level by refining the use of AMPI. AMPI indicates the age by which 50% of a population has HAV antibodies[62]. Table 4 de

| Country | Overall seroprevalence | Age at midpoint of population immunity (years) | Endemicity level | Key findings | Ref. |

| Iran | 86% | 21 | High to intermediate | Declining natural immunity in younger cohorts due to improved sanitation | Lankarani et al[63] |

| Jordan | 38.3% | 21-30 | Intermediate to low | Introduction of HAV vaccine resulted in epidemiological shift of HAV seroprevelance | Kareem et al[64] |

| Turkey | 67.23% over all; 35.9% in 15-18 years | Estimated 25-30 | Intermediate | Low seroprevelance in youth is due to the fact that these individuals were not included in routine vaccination | Karabey et al[65] |

| Vietnam | 69.2% (total), 57.9% (urban), 80.7% (rural) | 29 | High to intermediate | Socio-economic disparities and unsafe drinking water contribute to geographic difference | Cam Huong et al[66] |

Universal childhood immunization substantially reduces incidence, hospitalization and outbreak-related costs. Several recent studies reinforce the cost-effectiveness of hepatitis A vaccination, particularly in settings transitioning from high to intermediate endemicity. A modeling analysis by Abimbola et al[67] in 2023 estimated an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of United State dollar 48000 for full two-dose vaccination in their setting, highlighting that expanded vaccination must be justified by disease burden and budget constraints. In contrast, in India, Gurav et al[68] in 2024 demonstrated that routine vaccination of children aged 1 year is cost-saving both from societal and payer perspectives. Moreover, a systematic review by Gurav et al[69] found that 81.8% of economic evaluations in middle-income countries supported universal vaccination without screening as cost-effective. Across studies, sensitivity analyses often show vaccine unit cost, outpatient care costs, hospital costs, and productivity losses as key drivers of cost-effectiveness[70]. These recent results underscore that as endemicity shifts and adult susceptibility grows (reflected by rising AMPI), vaccine cost-effectiveness becomes more favorable and strategic choices (dose schedule, target age groups) matter even more.

With improved sanitation and food hygiene, fewer children are exposed to hepatitis A in childhood. The lack of exposure to HAV during childhood leads to higher susceptibility and a shift in the incidence of disease later in life, resulting in increases in symptomatic cases since age is a risk factor for the severity of HAV infections[22,71]. This was seen pre

In addition to the change in average age and symptom severity of cases, there is a change in classification of regions with high endemicity to intermediate endemicity, such as countries in Latin America and Middle East and North Africa region as shown by reviews of seroprevalence data[79,80]. With this change, the susceptible population of adolescents and young adults who may develop symptomatic illness increases, leading to a paradoxical increase in reported incidence. A socioeconomic and rural-urban divide can also be seen in the shift in epidemiology. These factors present a complex and heterogeneous picture of hepatitis exposure among different populations in the same countries. A significant increase in seroprevalence associated with a lower socioeconomic status was seen in a study from Egypt, Vietnam and Tunisia[66,81,82].

The incidence of hepatitis A presents a complex global picture, with both increases and decreases in different regions and demographics. The overall global declining seroprevalence rates are paralleled by a seemingly paradoxical increase in clinical incident cases of hepatitis A[83]. One explanation for this may be due to increased population growth, especially in low-income and middle-income countries, with China and India accounting for a third of global cases in 2019[22]. Another explanation for the increase is that the reported incidence of hepatitis A can increase in low-endemicity areas due to an increase in the average number of infections resulting in symptomatic illness[84]. In many low-income countries, the endemic levels of hepatitis A remain high, with poor sanitation and food hygiene being a major reason[22]. High-income countries, despite showing decreasing seroprevalence rates and low endemicity, have also seen sporadic outbreaks particularly among unvaccinated high-risk groups such as men who have sex with men, people who inject drugs, or those experiencing homelessness amplified by imported contaminated food[85-87]. Overall, the data shows persistent high levels of hepatitis A in hyperendemic regions and the emergence of frequent outbreaks in low-endemic regions[57]. A recent meta-analysis showed that hospitalization rate related to foodborne outbreak has shown a significant upward trend over time (P = 0.002)[88]. Table 5 demonstrates examples of HAV outbreaks[89-108].

| Group | Region | Key details | Ref. |

| Men who have sex with men | Europe, United States, Israel, Chile, Poland, Barcelona | 1400 cases in 16 European Union/European Economic Area countries; three HAV strains; linked outbreaks in Israel/Chile; mostly non-immune men who have sex with men engaging in high-risk sexual behaviour, increase risk with concomitant HIV infection | Ndumbi et al[89], Enkirch et al[90], Raczyńska et al[91], Dabrowska et al[92] |

| Patient who inject drugs | California, Michigan, Kentucky, Utah, London, Ontario | Increased HAV cases among persons who inject drugs or homelessness due to low vaccination coverage, syndemic involving concomitant HIV, HCV, HAV and group A streptococcal infection | Foster et al[93], Turner[94] |

| Foodborne | Europe, Italy, Sweden, Austria, United States, Michigan | Large European Union and Italy outbreak from frozen berries; Sweden, Austria, Michigan linked to imported strawberries; outbreaks from contaminated food or infected food handlers | Fallucca et al[95], Authority[96], Hutin et al[97], Greig and Ravel[98] |

| Travelers/migration | France, United States of America (United States) | Travel-related cases account for approximately 30%-46% of HAV cases in United States/Europe; 254 cases of hepatitis A in international travellers, with most cases occurring in unvaccinated individuals | Migueres et al[99], Balogun et al[100] |

| Homelessness | San Diego (United States), San Francisco (United States) | People experiencing homelessness had 3.3 × higher odds of infection, higher hospitalization and death rates; prevalence increased with years of homelessness, injection drug use, and foreign-born status | Peak et al[101], Hennessey et al[102] |

| Community transmission | Brazil, Germany | Person-to-person transmission common in enclosed spaces; 34.3% of household contacts infected; outbreak among Ukrainian war refugees and volunteer caregiver | Lima et al[103], Krumbholz et al[104] |

| HIV positive patients | Iran, Warsaw, Poland | 97.7% HAV seroprevelance; outbreaks in HIV positive men who have sex with men | Dabrowska et al[92], Omidifar et al[105] |

| Chronic liver disease (HBV and HCV) | Italy, Argentenia | HAV superinfection causes severe disease, fulminant hepatitis; higher fatality in coinfected patients; HAV outbreaks among men who have sex with men show high rates of HIV, syphilis and HBV co-infection | Vento et al[106], Marciano et al[107] |

| Metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease | United States | Increase odds of liver fibrosis | Vassilopoulos et al[108] |

HAV is characterized by a single serotype, which supports the continued efficacy of existing vaccines, and categorized into six genotypes (I-VI), with human disease mainly caused by genotypes I, II, and III, each further subdivided into subgenotypes such as IA, IB, IC, IIA, IIB, IIIA, and IIIB[109]. Recent evidence points to the emergence of antigenic variants. These are strains with minor genetic mutations, particularly in the viral protein 1 (VP1) region. Genomic comparisons indicate greater quasispecies diversity and a higher frequency of non-synonymous mutations in VP1 among vaccinated individuals, suggesting vaccine-driven selective pressure[110]. A molecular analysis of HAV isolates from Tunisia (2003) found two novel antigenic variants within sub-genotype IA: (1) One with a 38 amino acid deletion in a known neutralization region; and (2) Another with a unique amino acid substitution linked to fulminant hepatitis[111]. From 2018 to 2022, Florida reported 5491 hepatitis A cases, with genotyping showing predominance of subgenotype IB (69%) which carries over fourfold higher mortality risk, highlighting the importance of molecular surveillance in outbreak management[112]. While most analyses rely on partial VP1/2A sequences, whole-genome sequencing offers greater accuracy and resolution to detect antigenic variants and vaccine escape mutations[113].

In the recent position paper on hepatitis A vaccination, WHO recommends that vaccination against HAV be introduced into national immunization schedules for individuals aged ≥ 12 months, based on: (1) An increasing trend over time of acute hepatitis A disease, including severe disease, among older children, adolescents or adults; (2) Changes in the endemicity of the region from high to intermediate; and (3) Cost-effectiveness. In this position paper, WHO does not recommend childhood vaccination in areas with very high endemicity as most individuals are asymptomatically infected with HAV in childhood, which prevents clinical hepatitis A in adolescents and adults. In areas with low and very low endemicity, the WHO recommends targeted vaccinations in high-risk groups[39]. Following this phenomenon of decreasing endemicity leading to increased incidence of clinical disease, the WHO recommends the implementation of universal childhood vaccination in regions with changes in endemicity from high to intermediate[39]. This underscores the need for incidence and seroprevalence surveillance to recognize this shift, especially in low-income and middle-income countries that have been previously classified as high-endemicity regions. The role of urbanization and so

The incidence of hepatitis A presents a complex global picture, with both increases and decreases in different regions and demographics. The overall global declining seroprevalence rates are paralleled by a seemingly paradoxical increase in clinical incident cases of hepatitis A among adults necessitating adult vaccination and measures to mitigate the risk of HAV transmission in communities by strengthening surveillance programs including genomic and food-supply traceability combined with public education and environmental hygiene measures to meet the WHO 2030 hepatitis-elimination target.

| 1. | Henderson B. FAO/WHO Experts Rank Foodborne Viruses of Greatest Public Health Significance. 2024. Available from: https://www.food-safety.com/articles/10011-fao-who-experts-rank-foodborne-viruses-of-greatest-public-health-significance. |

| 2. | Wasley A, Fiore A, Bell BP. Hepatitis A in the era of vaccination. Epidemiol Rev. 2006;28:101-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Xiao W, Zhao J, Chen Y, Liu X, Xu C, Zhang J, Qian Y, Xia Q. Global burden and trends of acute viral hepatitis among children and adolescents from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Hepatol Int. 2024;18:917-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | World Health Organization. Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis 2016-2021. Towards ending viral hepatitis. 2016. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HIV-2016.06. |

| 5. | O'Shea H, Blacklaws BA, Collins PJ, McKillen J, Fitzgerald R. Viruses associated with foodborne infections. In: Reference Module in Life Sciences. Netherlands: Elsevier, 2019. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yin-Murphy M, Almond JW. Picornaviruses. In: Baron S, editor. Medical Microbiology. 4th ed. Galveston: University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, 1996. |

| 7. | Pintó RM, Costafreda MI, Bosch A. Risk assessment in shellfish-borne outbreaks of hepatitis A. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7350-7355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Khuroo MS. Viral hepatitis in international travellers: risks and prevention. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21:143-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | McFarland N, Dryden M, Ramsay M, Tedder RS, Ngui SL; 2008 Winchester HAV Outbreak Team. An outbreak of hepatitis A affecting a nursery school and a primary school. Epidemiol Infect. 2011;139:336-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Henning KJ, Bell E, Braun J, Barker ND. A community-wide outbreak of hepatitis A: risk factors for infection among homosexual and bisexual men. Am J Med. 1995;99:132-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Positive test results for acute hepatitis A virus infection among persons with no recent history of acute hepatitis--United States, 2002-2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:453-456. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Kanda T, Sasaki-Tanaka R, Ishii K, Suzuki R, Inoue J, Tsuchiya A, Nakamoto S, Abe R, Fujiwara K, Yokosuka O, Li TC, Kunita S, Yotsuyanagi H, Okamoto H; AMED HAV and HEV Study Group. Recent advances in hepatitis A virus research and clinical practice guidelines for hepatitis A virus infection in Japan. Hepatol Res. 2024;54:4-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nainan OV, Xia G, Vaughan G, Margolis HS. Diagnosis of hepatitis a virus infection: a molecular approach. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:63-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shin EC, Jeong SH. Natural History, Clinical Manifestations, and Pathogenesis of Hepatitis A. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8:a031708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Glikson M, Galun E, Oren R, Tur-Kaspa R, Shouval D. Relapsing hepatitis A. Review of 14 cases and literature survey. Medicine (Baltimore). 1992;71:14-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Keeffe EB. Hepatitis A and B superimposed on chronic liver disease: vaccine-preventable diseases. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2006;117:227-37; discussion 237. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Webb GW, Kelly S, Dalton HR. Hepatitis A and Hepatitis E: Clinical and Epidemiological Features, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 2020;42:171-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | World Health Organization. Hepatitis A: Vaccine Preventable Diseases Surveillance Standards. 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/vaccine-preventable-diseases-surveillance-standards-hepa. |

| 19. | Patterson J, Abdullahi L, Hussey GD, Muloiwa R, Kagina BM. A systematic review of the epidemiology of hepatitis A in Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hofmeister MG, Gupta N; Hepatitis A Mortality Investigators. Preventable Deaths During Widespread Community Hepatitis A Outbreaks - United States, 2016-2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:1128-1133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | IHME Pathogen Core Group. Global burden associated with 85 pathogens in 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024;24:868-895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 70.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cao G, Jing W, Liu J, Liu M. The global trends and regional differences in incidence and mortality of hepatitis A from 1990 to 2019 and implications for its prevention. Hepatol Int. 2021;15:1068-1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | World Health Organization. The immunological basis for immunization series: module 18: Hepatitis A. 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/97892516327. |

| 24. | Coursaget P, Leboulleux D, Gharbi Y, Enogat N, Ndao MA, Coll-Seck AM, Kastally R. Etiology of acute sporadic hepatitis in adults in Senegal and Tunisia. Scand J Infect Dis. 1995;27:9-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tsega E, Mengesha B, Hansson BG, Lindberg J, Nordenfelt E. Hepatitis A, B, and delta infection in Ethiopia: a serologic survey with demographic data. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;123:344-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cianciara J. Hepatitis A shifting epidemiology in Poland and Eastern Europe. Vaccine. 2000;18 Suppl 1:S68-S70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Green MS, Block C, Slater PE. Rise in the incidence of viral hepatitis in Israel despite improved socioeconomic conditions. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:464-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bell BP, Shapiro CN, Alter MJ, Moyer LA, Judson FN, Mottram K, Fleenor M, Ryder PL, Margolis HS. The diverse patterns of hepatitis A epidemiology in the United States-implications for vaccination strategies. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1579-1584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Prodinger WM, Larcher C, Sölder BM, Geissler D, Dierich MP. Hepatitis A in Western Austria--the epidemiological situation before the introduction of active immunisation. Infection. 1994;22:53-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gil A, González A, Dal-Ré R, Ortega P, Dominguez V. Prevalence of antibodies against varicella zoster, herpes simplex (types 1 and 2), hepatitis B and hepatitis A viruses among Spanish adolescents. J Infect. 1998;36:53-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Shapiro CN, Coleman PJ, McQuillan GM, Alter MJ, Margolis HS. Epidemiology of hepatitis A: seroepidemiology and risk groups in the USA. Vaccine. 1992;10 Suppl 1:S59-S62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Böttiger M, Christenson B, Grillner L. Hepatitis A immunity in the Swedish population. A study of the prevalence of markers in the Swedish population. Scand J Infect Dis. 1997;29:99-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Peetermans J. Production, quality control and characterization of an inactivated hepatitis A vaccine. Vaccine. 1992;10 Suppl 1:S99-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Armstrong ME, Giesa PA, Davide JP, Redner F, Waterbury JA, Rhoad AE, Keys RD, Provost PJ, Lewis JA. Development of the formalin-inactivated hepatitis A vaccine, VAQTA from the live attenuated virus strain CR326F. J Hepatol. 1993;18 Suppl 2:S20-S26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zhang L. Hepatitis A vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16:1565-1573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | López-Gigosos R, Segura-Moreno M, Díez-Díaz R, Plaza E, Mariscal A. Commercializing diarrhea vaccines for travelers. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10:1557-1567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Ghildayal N. Cost-effectiveness of Hepatitis A vaccination in a developed and developing country. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2019;32:1175-1199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | WHO position paper on hepatitis A vaccines: June 2012-recommendations. Vaccine. 2013;31:285-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | World Health Organization. WHO position paper on hepatitis A vaccines, October 2022. 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/policies/position-papers/hepatitis-a. |

| 40. | Doshani M, Weng M, Moore KL, Romero JR, Nelson NP. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for Use of Hepatitis A Vaccine for Persons Experiencing Homelessness. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:153-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Nelson NP, Weng MK, Hofmeister MG, Moore KL, Doshani M, Kamili S, Koneru A, Haber P, Hagan L, Romero JR, Schillie S, Harris AM. Prevention of Hepatitis A Virus Infection in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69:1-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Palaisy D. Hepatitis A immunization and high-risk populations in Canada and internationally. National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases. 2022. |

| 43. | Brito WI, Souto FJD. Universal hepatitis A vaccination in Brazil: analysis of vaccination coverage and incidence five years after program implementation. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2020;23:e200073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Guzman-Holst A, Luna-Casas G, Burguete Garcia A, Madrid-Marina V, Cervantes-Apolinar MY, Andani A, Huerta-Garcia G, Sánchez-González G. Burden of disease and associated complications of hepatitis a in children and adults in Mexico: A retrospective database study. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0268469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Flichman DM, Ridruejo E, Grosso F, Ramírez E, Martínez AP, Baré P, Di Lello FA. Seroprevalence of hepatitis A virus among people born before and after implementation of universal vaccination in Argentina. Infect Dis (Lond). 2024;56:983-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Johnson KD, Lu X, Zhang D. Adherence to hepatitis A and hepatitis B multi-dose vaccination schedules among adults in the United Kingdom: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Szucs T. Cost-effectiveness of hepatitis A and B vaccination programme in Germany. Vaccine. 2000;18 Suppl 1:S86-S89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Bechini A, Boccalini S, Del Riccio M, Pattyn J, Hendrickx G, Wyndham-Thomas C, Gabutti G, Maggi S, Ricciardi W, Rizzo C, Costantino C, Vezzosi L, Guida A, Morittu C, Van Damme P, Bonanni P. Overview of adult immunization in Italy: Successes, lessons learned and the way forward. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2024;20:2411821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Urbiztondo L, Pérez-Martin JJ, Borràs-López E, Navarro-Alonso JA, Limia A. Immunization recommendations against hepatitis A in Spain: Effectiveness of immunization in MSM and selection of antigenic variants. EBioMedicine. 2019;45:19-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Ryani MA. Hepatitis Management in Saudi Arabia: Trends, Prevention, and Key Interventions (2016-2025). Medicina (Kaunas). 2025;61:1509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Yigit M, Kalayci F. Vaccination status and hepatitis A immunity in children: insights from a large-scale study in Turkey. BMC Infect Dis. 2025;25:61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Shah N, Faridi MMA, Bhave S, Ghosh A, Balasubramanian S, Arankalle V, Shah R, Chitkara AJ, Wadhwa A, Chaudhry J, Srinivasan R, Surendranath M, Sapru A, Mitra M. Expert consensus and recommendations on the live attenuated hepatitis A vaccine and immunization practices in India. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2025;21:2447643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Poovorawan Y, Kanokudom S, Inma P, Nilyanimit P, Wanlapakorn N. Current Epidemiological Trends and Public Health Challenges of Hepatitis A Virus Infection in Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2025;113:724-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Yan BY, Lv JJ, Liu JY, Feng Y, Wu WL, Xu AQ, Zhang L. Changes in seroprevalence of hepatitis A after the implementation of universal childhood vaccination in Shandong Province, China: A comparison between 2006 and 2014. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;82:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Patterson J, Cleary S, Norman JM, Van Zyl H, Awine T, Mayet S, Kagina B, Muloiwa R, Hussey G, Silal SP. Modelling the Cost-Effectiveness of Hepatitis A in South Africa. Vaccines (Basel). 2024;12:116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Ahmed S, Nashwan AJ. Rising adult hepatitis A in Pakistan: Shifting trends and public health solutions. World J Virol. 2025;14:102519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Jacobsen KH, Koopman JS. Declining hepatitis A seroprevalence: a global review and analysis. Epidemiol Infect. 2004;132:1005-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Daniels D, Grytdal S, Wasley A; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surveillance for acute viral hepatitis - United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58:1-27. [PubMed] |

| 59. | Poovorawan Y, Theamboonlers A, Sinlaparatsamee S, Chaiear K, Siraprapasiri T, Khwanjaipanich S, Owatanapanich S, Hirsch P. Increasing susceptibility to HAV among members of the young generation in Thailand. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2000;18:249-253. [PubMed] |

| 60. | Chakravarti A, Bharara T. Epidemiology of Hepatitis A: Past and Current Trends. In: Streba CT, Vere CC, Rogoveanu I, Tripodi V, Lucangioli S, editors. Hepatitis A and Other Associated Hepatobiliary Diseases. London: IntechOpen, 2020. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 61. | Mantovani SA, Delfino BM, Martins AC, Oliart-Guzmán H, Pereira TM, Branco FL, Braña AM, Filgueira-Júnior JA, Santos AP, Arruda RA, Guimarães AS, Ramalho AA, Oliveira CS, Araújo TS, Arróspide N, Estrada CH, Codeço CT, da Silva-Nunes M. Socioeconomic inequities and hepatitis A virus infection in Western Brazilian Amazonian children: spatial distribution and associated factors. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Jacobsen KH. Globalization and the Changing Epidemiology of Hepatitis A Virus. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8:a031716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 63. | Lankarani KB, Honarvar B, Molavi Vardanjani H, Kharmandar A, Gouya MM, Zahraei SM, Baneshi MR, Ali-Akbarpour M, Kazemi M, Seif M, Fard SAZ, Emami A. Immunity to Hepatitis-A virus: A nationwide population-based seroprevalence study from Iran. Vaccine. 2020;38:7100-7107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Kareem N, Al-Salahat K, Bakri FG, Rayyan Y, Mahafzah A, Sallam M. Tracking the Epidemiologic Shifts in Hepatitis A Sero-Prevalence Using Age Stratification: A Cross-Sectional Study at Jordan University Hospital. Pathogens. 2021;10:1081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Karabey M, Alacam S, Karabulut N, Uysal H, Gunduz A, Aydina OA. Hepatitis A virus infection and seroprevalence, Istanbul, Turkey, 2020-2023. Ann Saudi Med. 2024;44:386-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Cam Huong NT, Van Tri D, Luan NH, Thinh NH, Ngoc Chau TS, Thi Vo TL, Tran DK, Nguyen M, Guzman-Holst A. Seroprevalence of hepatitis A virus infection in urban and rural areas in Vietnam. PLoS One. 2025;20:e0323139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Abimbola TO, Van Handel M, Tie Y, Ouyang L, Nelson N, Weiser J. Cost-effectiveness of expanded hepatitis A vaccination among adults with diagnosed HIV, United States. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0282972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Gurav YK, Bagepally BS, Chitpim N, Sobhonslidsuk A, Gupte MD, Chaikledkaew U, Thakkinstian A, Thavorncharoensap M. Cost-effective analysis of hepatitis A vaccination in Kerala state, India. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0306293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Gurav YK, Bagepally BS, Thakkinstian A, Chaikledkaew U, Thavorncharoensap M. Economic evaluation of hepatitis A vaccines by income level of the country: A systematic review. Indian J Med Res. 2022;156:388-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Hayajneh WA, Daniels VJ, James CK, Kanıbir MN, Pilsbury M, Marks M, Goveia MG, Elbasha EH, Dasbach E, Acosta CJ. Public health impact and cost effectiveness of routine childhood vaccination for hepatitis a in Jordan: a dynamic model approach. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Jacobsen KH, Wiersma ST. Hepatitis A virus seroprevalence by age and world region, 1990 and 2005. Vaccine. 2010;28:6653-6657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 394] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 72. | Asratian AA, Melik-Andreasian GG, Mkhitarian IL, Aleksanian IuT, Shmavonian MV, Kazarian SM, Mkhitarian RG, Kozhevnikova LK. [Seroepidemiological characterization of virus hepatitis in the Republic of Armenia]. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 2005;93-96. [PubMed] |

| 73. | Victor JC, Surdina TY, Suleimeova SZ, Favorov MO, Bell BP, Monto AS. The increasing prominence of household transmission of hepatitis A in an area undergoing a shift in endemicity. Epidemiol Infect. 2006;134:492-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Mathur P, Arora NK. Epidemiological transition of hepatitis A in India: issues for vaccination in developing countries. Indian J Med Res. 2008;128:699-704. [PubMed] |

| 75. | Grover M, Gupta E, Samal J, Prasad M, Prabhakar T, Chhabra R, Agarwal R, Raghuvanshi BB, Sharma MK, Alam S. Rising trend of symptomatic infections due to Hepatitis A virus infection in adolescent and adult age group: An observational study from a tertiary care liver institute in India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2024;50:100653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Lim DH, Sohn W, Jeong JY, Oh H, Lee JG, Yoon EL, Kim TY, Nam S, Sohn JH. The chronological changes in the seroprevalence of anti-hepatitis A virus IgG from 2005 to 2019: Experience at four centers in the capital area of South Korea. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e31639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Peng H, Wang Y, Wei S, Kang W, Zhang X, Cheng X, Bao C. Trends and projections of Hepatitis A incidence in eastern China from 2007 to 2021: an age-period-cohort analysis. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1476748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Shahid Y, Butt AS, Jamali I, Ismail FW. Rising incidence of acute hepatitis A among adults and clinical characteristics in a tertiary care center of Pakistan. World J Virol. 2025;14:97482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Tapia-Conyer R, Santos JI, Cavalcanti AM, Urdaneta E, Rivera L, Manterola A, Potin M, Ruttiman R, Tanaka Kido J. Hepatitis A in Latin America: a changing epidemiologic pattern. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:825-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Melhem NM, Talhouk R, Rachidi H, Ramia S. Hepatitis A virus in the Middle East and North Africa region: a new challenge. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21:605-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Al-Aziz AM, Awad MA. Seroprevalence of hepatitis A virus antibodies among a sample of Egyptian children. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14:1028-1035. [PubMed] |

| 82. | Rezig D, Ouneissa R, Mhiri L, Mejri S, Haddad-Boubaker S, Ben Alaya N, Triki H. [Seroprevalences of hepatitis A and E infections in Tunisia]. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2008;56:148-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Lemon SM, Ott JJ, Van Damme P, Shouval D. Type A viral hepatitis: A summary and update on the molecular virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis and prevention. J Hepatol. 2017;S0168-8278(17)32278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Shapiro CN, Margolis HS. Worldwide epidemiology of hepatitis A virus infection. J Hepatol. 1993;18 Suppl 2:S11-S14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Hu X, Collier MG, Xu F. Hepatitis A Outbreaks in Developed Countries: Detection, Control, and Prevention. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2020;17:166-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Foster MA, Hofmeister MG, Kupronis BA, Lin Y, Xia GL, Yin S, Teshale E. Increase in Hepatitis A Virus Infections - United States, 2013-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:413-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Di Cola G, Fantilli AC, Pisano MB, Ré VE. Foodborne transmission of hepatitis A and hepatitis E viruses: A literature review. Int J Food Microbiol. 2021;338:108986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Gandhi AP, Al-Mohaithef M, Aparnavi P, Bansal M, Satapathy P, Kukreti N, Rustagi S, Khatib MN, Gaidhane S, Zahiruddin QS. Global outbreaks of foodborne hepatitis A: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2024;10:e28810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Ndumbi P, Freidl GS, Williams CJ, Mårdh O, Varela C, Avellón A, Friesema I, Vennema H, Beebeejaun K, Ngui SL, Edelstein M, Smith-Palmer A, Murphy N, Dean J, Faber M, Wenzel J, Kontio M, Müller L, Midgley SE, Sundqvist L, Ederth JL, Roque-Afonso AM, Couturier E, Klamer S, Rebolledo J, Suin V, Aberle SW, Schmid D, De Sousa R, Augusto GF, Alfonsi V, Del Manso M, Ciccaglione AR, Mellou K, Hadjichristodoulou C, Donachie A, Borg ML, Sočan M, Poljak M, Severi E; Members of the European Hepatitis A Outbreak Investigation Team. Hepatitis A outbreak disproportionately affecting men who have sex with men (MSM) in the European Union and European Economic Area, June 2016 to May 2017. Euro Surveill. 2018;23:1700641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Enkirch T, Severi E, Vennema H, Thornton L, Dean J, Borg ML, Ciccaglione AR, Bruni R, Christova I, Ngui SL, Balogun K, Němeček V, Kontio M, Takács M, Hettmann A, Korotinska R, Löve A, Avellón A, Muñoz-Chimeno M, de Sousa R, Janta D, Epštein J, Klamer S, Suin V, Aberle SW, Holzmann H, Mellou K, Ederth JL, Sundqvist L, Roque-Afonso AM, Filipović SK, Poljak M, Vold L, Stene-Johansen K, Midgley S, Fischer TK, Faber M, Wenzel JJ, Takkinen J, Leitmeyer K. Improving preparedness to respond to cross-border hepatitis A outbreaks in the European Union/European Economic Area: towards comparable sequencing of hepatitis A virus. Euro Surveill. 2019;24:1800397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Raczyńska A, Wickramasuriya NN, Kalinowska-Nowak A, Garlicki A, Bociąga-Jasik M. Acute Hepatitis A Outbreak Among Men Who Have Sex With Men in Krakow, Poland; February 2017-February 2018. Am J Mens Health. 2019;13:1557988319895141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Dabrowska MM, Nazzal K, Wiercinska-Drapalo A. Hepatitis A and hepatitis A virus/HIV coinfection in men who have sex with men, Warsaw, Poland, September 2008 to September 2009. Euro Surveill. 2011;16:19950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Foster M, Ramachandran S, Myatt K, Donovan D, Bohm S, Fiedler J, Barbeau B, Collins J, Thoroughman D, McDonald E, Ballard J, Eason J, Jorgensen C. Hepatitis A Virus Outbreaks Associated with Drug Use and Homelessness - California, Kentucky, Michigan, and Utah, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1208-1210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Turner S. Numerous outbreaks amongst homeless and injection drug-using populations raise concerns of an evolving syndemic in London, Canada. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Fallucca A, Restivo V, Sgariglia MC, Roveta M, Trucchi C. Hepatitis a Vaccine as Opportunity of Primary Prevention for Food Handlers: A Narrative Review. Vaccines (Basel). 2023;11:1271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | European Food Safety Authority. Outbreak of Hepatitis A virus infection in residents and travellers to Italy. United States: Wiley Online Library, 2013: 2397-8325. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 97. | Hutin YJ, Pool V, Cramer EH, Nainan OV, Weth J, Williams IT, Goldstein ST, Gensheimer KF, Bell BP, Shapiro CN, Alter MJ, Margolis HS. A multistate, foodborne outbreak of hepatitis A. National Hepatitis A Investigation Team. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:595-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Greig JD, Ravel A. Analysis of foodborne outbreak data reported internationally for source attribution. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009;130:77-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Migueres M, Lhomme S, Izopet J. Hepatitis A: Epidemiology, High-Risk Groups, Prevention and Research on Antiviral Treatment. Viruses. 2021;13:1900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Balogun O, Brown A, Angelo KM, Hochberg NS, Barnett ED, Nicolini LA, Asgeirsson H, Grobusch MP, Leder K, Salvador F, Chen L, Odolini S, Díaz-Menéndez M, Gobbi F, Connor BA, Libman M, Hamer DH. Acute hepatitis A in international travellers: a GeoSentinel analysis, 2008-2020. J Travel Med. 2022;29:taac013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Peak CM, Stous SS, Healy JM, Hofmeister MG, Lin Y, Ramachandran S, Foster MA, Kao A, McDonald EC. Homelessness and Hepatitis A-San Diego County, 2016-2018. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:14-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Hennessey KA, Bangsberg DR, Weinbaum C, Hahn JA. Hepatitis A seroprevalence and risk factors among homeless adults in San Francisco: should homelessness be included in the risk-based strategy for vaccination? Public Health Rep. 2009;124:813-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Lima LR, De Almeida AJ, Tourinho Rdos S, Hasselmann B, Ximenez LL, De Paula VS. Evidence of hepatitis A virus person-to-person transmission in household outbreaks. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Krumbholz A, Marcic A, Valentin M, Schemmerer M, Wenzel JJ. Hepatitis A outbreak in a refugee shelter in Kiel, northern Germany. J Med Virol. 2023;95:e29185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Omidifar N, Bagheri Lankarani K, Aghazadeh Ghadim MB, Khoshdel N, Joulaei H, Keshani P, Saghi SA, Nikmanesh Y. The Seroprevalence of Hepatitis A in Patients with Positive Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2023;15:196-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Vento S, Garofano T, Renzini C, Cainelli F, Casali F, Ghironzi G, Ferraro T, Concia E. Fulminant hepatitis associated with hepatitis A virus superinfection in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:286-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 580] [Cited by in RCA: 457] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Marciano S, Arufe D, Haddad L, Mendizabal M, Gadano A, Gaite L, Anders M, Garrido L, Martinez AA, Conte D, Barrabino M, Rovey L, Aubone MDV, Ratusnu N, Tanno H, Fainboim H, Oyervide A, de Labra L, Ruf A, Dirchwolf M. Outbreak of hepatitis A in a post-vaccination era: High rate of co-infection with sexually transmitted diseases. Ann Hepatol. 2020;19:641-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Vassilopoulos S, Vassilopoulos A, Benitez G, Kaczynski M, Shehadeh F, Kalligeros M, Mylonakis E. 2509. Association of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease with HBV, HAV, and HEV Exposure. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10:ofad500.2127. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Gholizadeh O, Akbarzadeh S, Ghazanfari Hashemi M, Gholami M, Amini P, Yekanipour Z, Tabatabaie R, Yasamineh S, Hosseini P, Poortahmasebi V. Hepatitis A: Viral Structure, Classification, Life Cycle, Clinical Symptoms, Diagnosis Error, and Vaccination. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2023;2023:4263309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Sabrià A, Gregori J, Garcia-Cehic D, Guix S, Pumarola T, Manzanares-Laya S, Caylà JA, Bosch A, Quer J, Pintó RM. Evidence for positive selection of hepatitis A virus antigenic variants in vaccinated men-having-sex-with men patients: Implications for immunization policies. EBioMedicine. 2019;39:348-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Gharbi-Khelifi H, Sdiri K, Harrath R, Fki L, Hakim H, Berthomé M, Billaudel S, Ferre V, Aouni M. Genetic analysis of HAV strains in Tunisia reveals two new antigenic variants. Virus Genes. 2007;35:155-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Doyle TJ, Buck BH, Locksmith TJ, McGruder-Rawson BM, Khudyakov Y, Blackmore C. Genomic Epidemiology of Resurgent Hepatitis A in Florida, 2018-2022. J Infect Dis. 2025;232:943-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Sicilia P, Fantilli AC, Cuba F, Di Cola G, Barbás MG, Poklepovich T, Ré VE, Castro G, Pisano MB. Novel strategy for whole-genome sequencing of hepatitis A virus using NGS illumina technology and phylogenetic comparison with partial VP1/2A genomic region. Sci Rep. 2025;15:6375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Inma P, Nilyanimit P, Wanlapakorn N, Aeemjinda R, Korkong S, Wihanthong P, Thawinwisan N, Puedkuntod P, Tinnaitorn W, Foonoi M, Meechin P, Poovorawan Y. Significant Reduction in Seroprevalence of Antibodies Against Hepatitis A across Thailand, 2024. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2025;112:1329-1334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Trucchi C, Del Puente F, Piccinini C, Roveta M, Sartini M, Cristina ML. Determining the burden of foodborne hepatitis A spread by food handlers: suggestions for a targeted vaccination? Front Public Health. 2025;13:1617004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Kankam M, Griffin R, Price J, Michaud J, Liang W, Llorens MB, Sanz A, Vince B, Vilardell D. Polyvalent Human Immune Globulin: A Prospective, Open-Label Study Assessing Anti-Hepatitis A Virus (HAV) Antibody Levels, Pharmacokinetics, and Safety in HAV-Seronegative Healthy Subjects. Adv Ther. 2020;37:2373-2389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Nicholls M, Bruce M, Thomas J. Management of hepatitis A in a food handler at a London secondary school. Commun Dis Public Health. 2003;6:26-29. [PubMed] |

| 118. | Fortin A, Milord F. Hepatitis A in restaurant clientele and staff--Quebec. Can Commun Dis Rep. 1998;24:53-59. [PubMed] |

| 119. | Jones AE, Smith JL, Hindman SH, Fleissner ML, Judelsohn R, Englender SJ, Tilson H, Maynard JE. Foodborne hepatitis A infection: a report of two urban restaurant-associated outbreaks. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;105:156-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 120. | Beshearse E, Bruce BB, Nane GF, Cooke RM, Aspinall W, Hald T, Crim SM, Griffin PM, Fullerton KE, Collier SA, Benedict KM, Beach MJ, Hall AJ, Havelaar AH. Attribution of Illnesses Transmitted by Food and Water to Comprehensive Transmission Pathways Using Structured Expert Judgment, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:182-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 121. | Menezes A, Razafimahatratra SL, Wariri O, Graham AL, Metcalf CJE. Strengthening serological studies: the need for greater geographical diversity, biobanking, and data-accessibility. Trends Microbiol. 2025;33:1155-1162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 122. | Yeo D, Jung S, Yoon D, Hwang S, Lim DJ, Jin S, Choi J, Hong KH, Choi C. Development of a direct whole genome sequencing for hepatitis A virus from serum and analysis of genetic characteristics. Sci Rep. 2025;15:25005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 123. | Braunfeld JB, Dao BL, Buendia J, Amiling R, LeBlanc C, Jewell MP, Henry H, Cosentino G, Gounder P. Notes from the Field: Genomic and Wastewater Surveillance Data to Guide a Hepatitis A Outbreak Response - Los Angeles County, March 2024-June 2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2025;74:66-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 124. | World Health Organization. Hepatitis A. 2025. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-a/. |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/