INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a pervasive yet under-treated and commonly undiagnosed chronic illness. Characterized by a prolonged chronic stage, it can lead to both hepatic and extrahepatic health issues. According to the World Health Organization, chronic HCV infection affects an estimated 57 million individuals globally[1], and these individuals have a 25%-32% increased risk of cardiovascular complications - including coronary artery disease, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease - compared to uninfected controls, independent of traditional risk factors[2,3]. In the United States, an estimated 3.7 million individuals are affected by this virus, making it the most common blood-borne infection in the country as well as the most common cause of end-stage liver disease, prompting liver transplant[4]. Worldwide, however, fewer than 5% of individuals infected with HCV have been diagnosed, and under 1% have undergone treatment. Nevertheless, the World Health Organization has been implementing different approaches to reduce HCV incidence rates, including broader screening efforts, improved access to appropriate healthcare services, and the implementation of effective and efficient direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapies[5].

HCV, identified in 1989, is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus classified within the Flaviviridae family. The HCV life cycle is intricately associated with hepatocyte lipid metabolism[6]. Viral replication induces extensive rearrangements of intracellular membranes, resulting in the formation of a specialized cytoplasmic structure termed the “membranous web”. Additionally, HCV assembly is closely linked to the biogenesis of very-low-density lipoproteins, with viral propagation dependent on lipid metabolic pathways. These pathways include cholesterol transfer via lipoprotein receptors during cellular entry, lipid-mediated regulation of viral genome replication, and the involvement of both cytosolic and luminal lipid droplets in viral particle formation[7].

In the United States, around 60% of acute HCV infections are linked to injection drug use, with additional risk factors including men who have sex with men [particularly those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)], perinatal transmission, tattoo placement, vertical transmission, hemodialysis, occupation in healthcare, and exposure to blood products prior to 1992[4]. Medical and cosmetic procedures pose a lower risk when appropriate infection-control practices are followed. Most individuals with acute HCV infection are asymptomatic, though some may develop symptoms such as jaundice, fatigue, and abdominal pain within a few weeks of exposure[5].

Chronic HCV infection is defined by the persistence of the viral RNA for over six months and is often clinically silent, although some patients exhibit gastrointestinal, neuropsychiatric, and algesic manifestations. Long-term complications of chronic HCV include hepatic fibrosis, cirrhosis, hepatocellular decompensation, and hepatocellular carcinoma, with 20%-30% of infected individuals developing cirrhosis over a 25-year to 30-year period. Established risk factors for cirrhosis include male sex, age over 50 years, co-infection with hepatitis B or HIV, immunosuppressive therapy, alcohol consumption, obesity, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis[8]. Up to 74% of patients experience extrahepatic manifestations that negatively impact quality of life, including an increased prevalence of diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease, many of which may be ameliorated through DAA therapy[5].

Although traditional existing literature often characterizes cirrhosis as a hypocoagulable state, emerging evidence supports the concept of a precariously rebalanced hemostatic system, rather than a primary bleeding diathesis. Additionally, extrahepatic manifestations of HCV - particularly those involving vascular and coagulation pathways - are increasingly acknowledged for their clinical relevance, paralleling growing interest in the systemic effects of chronic HCV infection[9]. Chronic HCV infection promotes a pro-inflammatory state that results in increased levels of thrombogenicity. Consequently, this inflammatory state is linked to an elevated risk of cardiovascular complications and related adverse events. The purpose of this review article is to explore the interplay of thrombotic risk in hepatitis C with hepatic and cardiovascular dysfunction and to assess the novel shift from the traditional view of cirrhosis as an anticoagulated state to a fragile rebalanced hemostasis.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF THROMBOTIC RISK IN HCV

HCV infection, long recognized for its hepatotropic nature and progression to cirrhosis, is now increasingly acknowledged as a systemic disease with significant thrombotic potential. While cirrhosis is classically associated with thrombocytopenia and reduced synthesis of coagulation factors, recent evidence suggests that liver disease - particularly when caused by HCV - can promote a prothrombotic state. A combination of chronic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, direct activation of the coagulation cascade, enhancement of platelet aggregation, and HCV-driven suppression of endogenous anticoagulant pathways contributes to an increased risk of both venous and arterial thrombotic events, including portal vein thrombosis (PVT), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), myocardial infarction, and stroke[10]. Understanding the underlying mechanisms and prevalence of these events is critical for guiding clinical suspicion and management in HCV-infected populations.

Thrombotic complications in HCV infection are believed to result from a constellation of interrelated mechanisms. Chronic inflammation is thought to enhance procoagulant activity by promoting activation of the coagulation cascade via inflammatory cytokines. A meta-analysis shows that in patients with HCV infection, this thrombotic tendency may be further amplified by endothelial dysfunction, which is partly driven by oxidative stress associated with persistent inflammation[11]. Furthermore, dysregulation of fibrinolysis and enhanced thrombin generation - partially mediated by tissue factor expression on virally infected endothelium - contribute to a prothrombotic state. The presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, frequently observed in HCV-infected patients, may further promote hypercoagulability. Additionally, circulating immune complexes, particularly in the context of mixed cryoglobulinemia, have been implicated in triggering vascular inflammation and thrombotic phenomena[10].

PVT is a significant complication in HCV-related cirrhosis. In a cohort of 1000 Egyptian cirrhotic patients, PVT was identified in 21.6% of cases, with complete portal vein occlusion observed in 70.4% of those affected. Clinically, half of these patients experienced at least one episode of portal hypertensive bleeding, while others presented with abdominal pain or jaundice. The presence of PVT was significantly associated with advanced liver disease, ascites, male sex, and focal hepatic lesions[11]. These data reflect the substantial thrombotic burden in HCV cirrhosis and reinforce the need for routine vascular imaging and risk stratification in this population.

Beyond the portal circulation, HCV infection has been linked to systemic venous thromboembolism (VTE), including PE and DVT. A retrospective cohort study showed an increased incidence of PE and DVT in patients aged 64 years or younger and in those without traditional risk factors or comorbidities, suggesting HCV itself may serve as an independent prothrombotic trigger[12]. Several mechanisms may account for this association. Chronic systemic inflammation in HCV can cause vasculopathy and impaired blood flow. Additionally, the prothrombotic state often observed in chronic liver disease includes a reduction in natural anticoagulants - such as antithrombin III, protein C, and protein S - alongside elevated levels of procoagulant factors, including factor VIII and von Willebrand factor. These alterations collectively shift the hemostatic balance toward hypercoagulability, increasing the risk of thrombotic events[13]. These findings suggest that HCV should be considered a potential underlying etiology in cases of VTE of unknown origin[12].

Chronic HCV infection is also associated with an increased risk of thrombotic cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, including coronary artery disease, acute coronary syndromes, and ischemic stroke. The underlying mechanisms are multifactorial but primarily stem from persistent systemic inflammation, which promotes endothelial dysfunction, accelerates atherosclerotic plaque formation, and enhances thrombin generation - processes that occur independently of serum lipid levels. HCV-infected individuals are also susceptible to cardiomyopathies, such as dilated and hypertrophic forms, which carry poor prognoses and may contribute to intracardiac thrombosis due to disrupted blood flow in the heart and stasis of blood in chambers. Lipid-lowering therapies have been shown to reduce the incidence of myocardial infarction in this population, likely due to their anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic properties rather than effects on lipid profiles alone[14]. These findings further support the systemic thrombotic risk posed by chronic HCV infection.

Chronic HCV infection elevates thrombotic and cardiovascular risk through mechanisms that are distinct from, but also overlap with, those of traditional risk factors such as diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension[15]. The unique contribution of HCV lies in its ability to act as a nontraditional, modifiable risk factor for thrombosis, independent of metabolic syndrome, and to potentiate cardiovascular risk even in the absence of classic risk factors[16]. Viral eradication with DAAs reverses many of these pathogenic processes, underscoring the importance of HCV-specific mechanisms in cardiovascular risk[17].

HEPATIC DYSFUNCTION AND COAGULATION IMBALANCE

Hemostatic alterations are frequently encountered in patients with cirrhosis. Historically, the bleeding tendency observed in this population was attributed to impaired hepatic synthesis of procoagulant factors and thrombocytopenia, which were also thought to confer relative protection against thrombotic events. Consequently, invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures were traditionally considered to pose a high risk for bleeding in this population. However, emerging evidence has challenged this paradigm, demonstrating concurrent reductions in anticoagulant factors. These parallel changes result in a rebalanced, yet inherently unstable, hemostatic system. As a result, patients with cirrhosis remain vulnerable to both hemorrhagic and thrombotic complications, depending on the clinical context and precipitating factors[18].

In cirrhosis, reduced activity of several procoagulant factors is offset by increased levels of factor VIII, synthesized by liver sinusoidal endothelial cells, along with decreased concentrations of natural anticoagulants. As mentioned previously, chronic liver disease is frequently associated with a prothrombotic state characterized by a decline in natural anticoagulant proteins, including antithrombin III, protein C, and protein S, along with elevated concentrations of procoagulant factors such as factor VIII and von Willebrand factor. This imbalance in the hemostatic system promotes a hypercoagulable state, thereby heightening the risk of thrombotic complications[11]. Additional prothrombotic influences include alterations in circulating microparticles, cell-free DNA, and neutrophil extracellular traps. Together, these changes promote a shift toward a pro-coagulant state[18].

Fibrinolytic balance is also disrupted in cirrhosis. Elevated levels of tissue-type and urokinase-type plasminogen activators, combined with reductions in α2-antiplasmin, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, and thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor, are somewhat counterbalanced by decreased plasminogen availability and reduced fibrin clot permeability. The net impact of these opposing forces on fibrinolysis remains uncertain. Nonetheless, current evidence supports the concept that patients with cirrhosis exhibit a rebalanced, yet procoagulant-leaning, hemostatic profile[18].

Cirrhosis develops because of chronic hepatic inflammation, leading to progressive replacement of normal parenchyma with fibrotic tissue and regenerative nodules. This distortion of hepatic structures increases the resistance in the vasculature, which results in the development of portal hypertension. The interplay between portal hypertension and the procoagulant shift of cirrhosis may contribute to the risk of PVT, a frequent and clinically significant complication in advanced liver disease. Variceal bleeding is a life-threatening sequela of cirrhosis and is primarily driven by portal hypertension[19]. The most common sites of bleeding are esophageal and gastric varices, while rectal variceal bleeding occurs less frequently[20]. This phenomenon may seem paradoxical considering the procoagulant state that these patients are in, but it is important to note that variceal bleeding is primarily driven by portal pressure and not related to failure of the hemostatic system[21].

In the context of chronic hepatitis C, impaired hepatic synthesis of thrombopoietin contributes to the development of thrombocytopenia[22]. Thrombopoietin, a key regulator of thrombopoiesis, is predominantly produced by hepatocytes. It exerts its effects by binding to receptors on megakaryocyte progenitors and mature megakaryocytes, initiating signaling pathways that drive their proliferation and maturation. Nevertheless, reductions in platelet count are compensated by increased levels of the platelet adhesive protein von Willebrand factor, while decreases in procoagulant and antifibrinolytic proteins are offset by parallel declines in anticoagulant and profibrinolytic factors[18]. These findings emphasize the delicate equilibrium between platelet production and coagulation factors in preserving vascular integrity despite liver impairment.

INFLAMMATION, CRYOGLOBULINEMIA, AND ENDOTHELIAL DYSFUNCTION

The liver is an essential part of the immune system through surveillance and maintenance of homeostasis. It is responsible for metabolizing gut pathogen-derived molecules, including lipopolysaccharides, as noted in a cross-sectional study[23]. When the liver is not functioning properly due to chronic inflammation and fibrosis caused by chronic HCV infection, it fails to adequately clear lipopolysaccharides, allowing this pathogenic molecule to accumulate and stimulate the immune system to release interleukin-6 (IL-6) and other pro-inflammatory molecules. This persistent stimulation of the immune system will eventually result in immune senescence and T cell exhaustion. T cells will express inhibitory markers and T cell immunoglobulins, which represent T cell exhaustion, as well as CD-57 expression and killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily G, which represent senescent T cells[24]. This exhaustion results from the extensive proliferation of the T cells, which is caused by the pro-inflammatory byproducts of impaired liver function and immune system dysfunction, as mentioned in a longitudinal study[24]. This chronic systemic inflammatory state will cause increased incidence of extrahepatic manifestations, including cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease[25].

Furthermore, HCV is a lymphotropic virus that promotes B-cell proliferation. This can cause the development of lymphoproliferative disorders, such as cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and monoclonal gammopathies (Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia, multiple myeloma, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance)[25,26]. Cryoglobulins are immunoglobulins that precipitate at temperatures below 37 °C and then redissolve at body temperature[26]. These immune complexes deposit within small and medium-sized vessels, leading to vascular injury, resulting in skin and organ involvement[26]. This phenomenon is known as cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, which presents with a wide array of presentations, including purpura, Raynaud’s phenomenon, skin ulceration, arthralgia, and many other systemic manifestations[26].

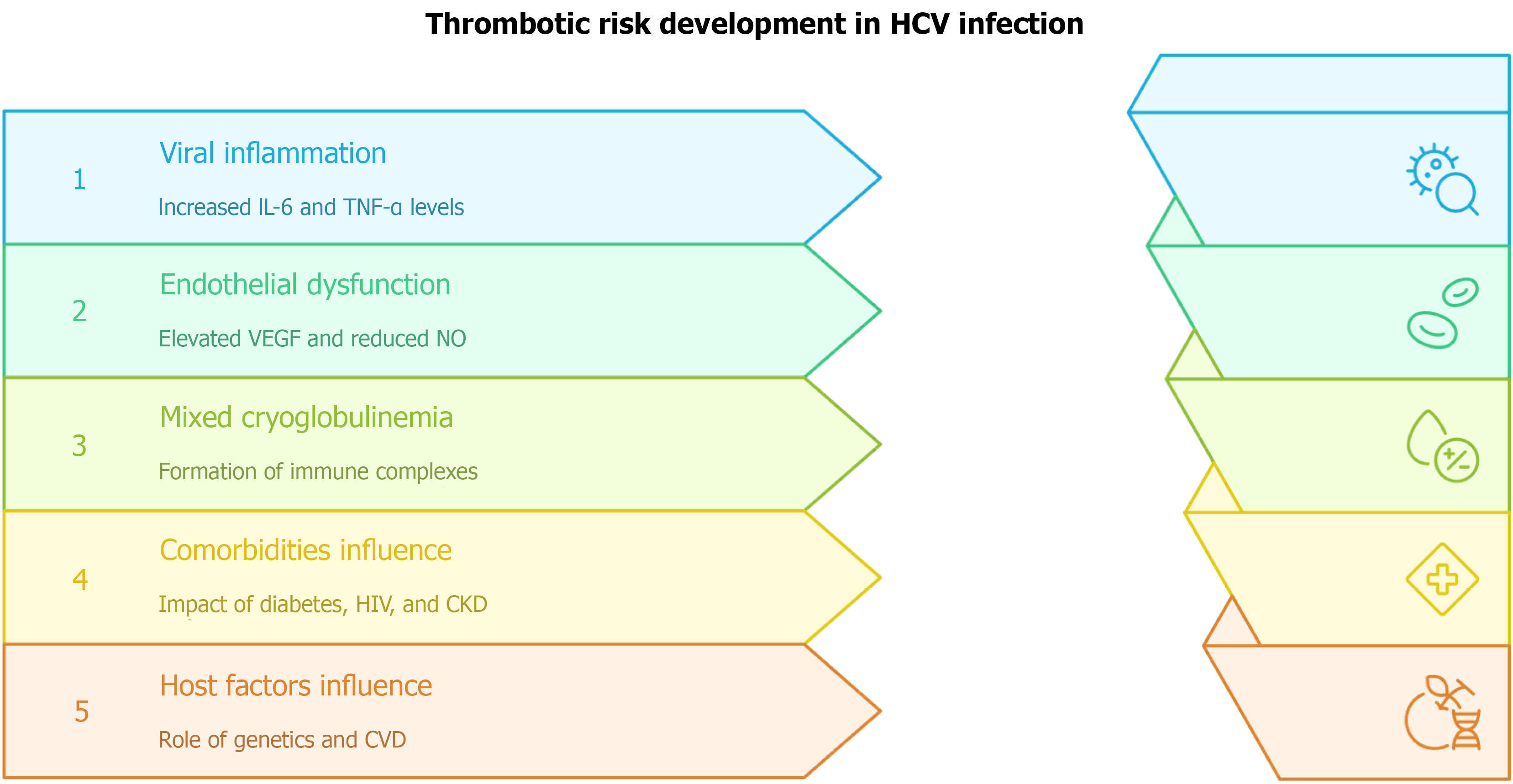

In the setting of HCV-induced cirrhosis and the development of lymphotropic disorders, there is an increased production of reactive oxygen species within diseased cells. In patients with HCV, elevated reactive oxygen species, antioxidants, and glutathione levels have been identified, especially within lymphocytes, which increases the correlation between HCV and oxidative stress. Additionally, patients with chronic hepatitis C have lower levels of antioxidant defense enzymes, including superoxide dismutase, glutathione reductase, and glutathione peroxidase. This oxidative stress perpetuates the cycle of worsening viral infection and thus viral-associated disorders, specifically through the upregulation of the genome translation of HCV, placing stress on other organelles (endoplasmic reticulum) that are normally protective against reactive oxygen species[27]. Elevated oxidative stress within the body from HCV promotes steatosis, fibrosis, and cirrhosis in the liver, leading to proinflammatory markers that favor insulin resistance and the accumulation of fatty acids, as noted in a prospective cohort study. These deposits within the walls of arteries increase the incidence of atherosclerosis. Endothelial dysfunction (in this case caused by atherosclerosis) causes systemic manifestations such as peripheral artery disease, coronary artery disease, stroke, etc.[28]. Endothelial activation upregulates vascular endothelial growth factor, an independent risk factor for stroke and coronary artery disease and a recognized extrahepatic manifestation of HCV infection[28]. During viremia, endothelial cells - which normally regulate coagulation - remain persistently activated, promoting a procoagulant state and correlating positively with thrombus formation[29]. Figure 1 illustrates these pathways, highlighting how chronic endothelial activation links HCV infection to increased vascular risk.

Figure 1 Thrombotic risk development in hepatitis C virus infection.

Viral inflammation is driven by elevated interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α, promoting immune activation. Endothelial dysfunction results from increased vascular endothelial growth factor and reduced nitric oxide bioavailability, favoring a procoagulant state. Mixed cryoglobulinemia contributes through immune complex deposition and vascular injury. Comorbidities, including diabetes, human immunodeficiency virus, and chronic kidney disease, further amplify risk. Host factors, such as genetic predisposition and baseline cardiovascular disease, modulate susceptibility. HCV: Hepatitis C virus; IL-6: Interleukin-6; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α; VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor; NO: Nitric oxide; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; CKD: Chronic kidney disease; CVD: Cardiovascular disease.

IMPACT OF DAA THERAPY

DAA therapy is essential for preventing further manifestations of chronic HCV. DAAs improve endothelial dysfunction and its sequelae (atherosclerosis and thrombogenesis)[28]. This improvement occurs through the reduction and reversal of systemic inflammation, which drives liver injury and lymphotropic disease. By decreasing this proinflammatory, hypercoagulable state, DAAs help reduce oxidative stress, endothelial activation, and thrombogenesis[28].

Sustained virological response (SVR) refers to the absence of detectable HCV RNA after completion of DAA treatment and correlates with treatment success. SVR is directly associated with decreased mortality, reduced liver damage, and less severe extrahepatic manifestations. DAAs decrease systemic inflammation and hypercoagulability, thereby lowering the risk of atherosclerosis and thrombosis[28]. According to an observational study, SVR is positively correlated with improved endothelial function, which can be demonstrated clinically by an elevated ankle-brachial index one year after DAA therapy[28]. The ankle-brachial index is a clinical test used to assess the severity of peripheral artery disease caused by atherosclerosis.

DAA therapy and prolonged SVR are strongly associated with reduced endothelial dysfunction, decreased vascular damage, and improved cardiovascular outcomes, including lower rates of thrombotic events such as stroke and coronary artery disease[28]. However, patients with extensive fibrosis remain at elevated risk for HCV sequelae despite virologic cure with DAAs[30]. This includes both hepatocellular carcinoma secondary to fibrosis and extrahepatic manifestations such as lymphotropic disorders, atherosclerosis, and thrombotic complications[30]. A large cohort study of HIV-infected veterans receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy showed that HCV seropositivity was independently associated with an increased risk of mortality. This demonstrates that although DAA therapy lowers cardiovascular disease incidence, the risk remains higher than in uninfected populations[31].

Furthermore, patients with advanced fibrosis despite viral clearance via DAAs continue to experience higher rates of cardiovascular events and thrombotic complications than those without fibrosis or the general population. HCV infection and interferon-based treatments cause continuous epigenetic alterations, including DNA methylation and histone modifications, in hepatocytes and vascular cells. These changes persist following viral clearance and are linked to impaired immune function and a continued risk of vascular and neoplastic complications[32]. Patients with advanced fibrosis may also experience persistent low-level inflammation, changes in cytokine levels, and immune system imbalances, which together promote a tendency for blood clot formation[33]. Additionally, chronic HCV infection causes endothelial dysfunction and vascular remodeling that may persist despite viral clearance, especially in patients with established fibrosis or cirrhosis[34]. Therefore, individuals with advanced liver fibrosis who achieve HCV eradication through DAAs remain at a persistent, though attenuated, risk of cardiovascular and prothrombotic complications. This risk is attributable to irreversible vascular injury, enduring epigenetic modifications, and sustained immune activation.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL MECHANISMS: A MULTIFACTORIAL MODEL

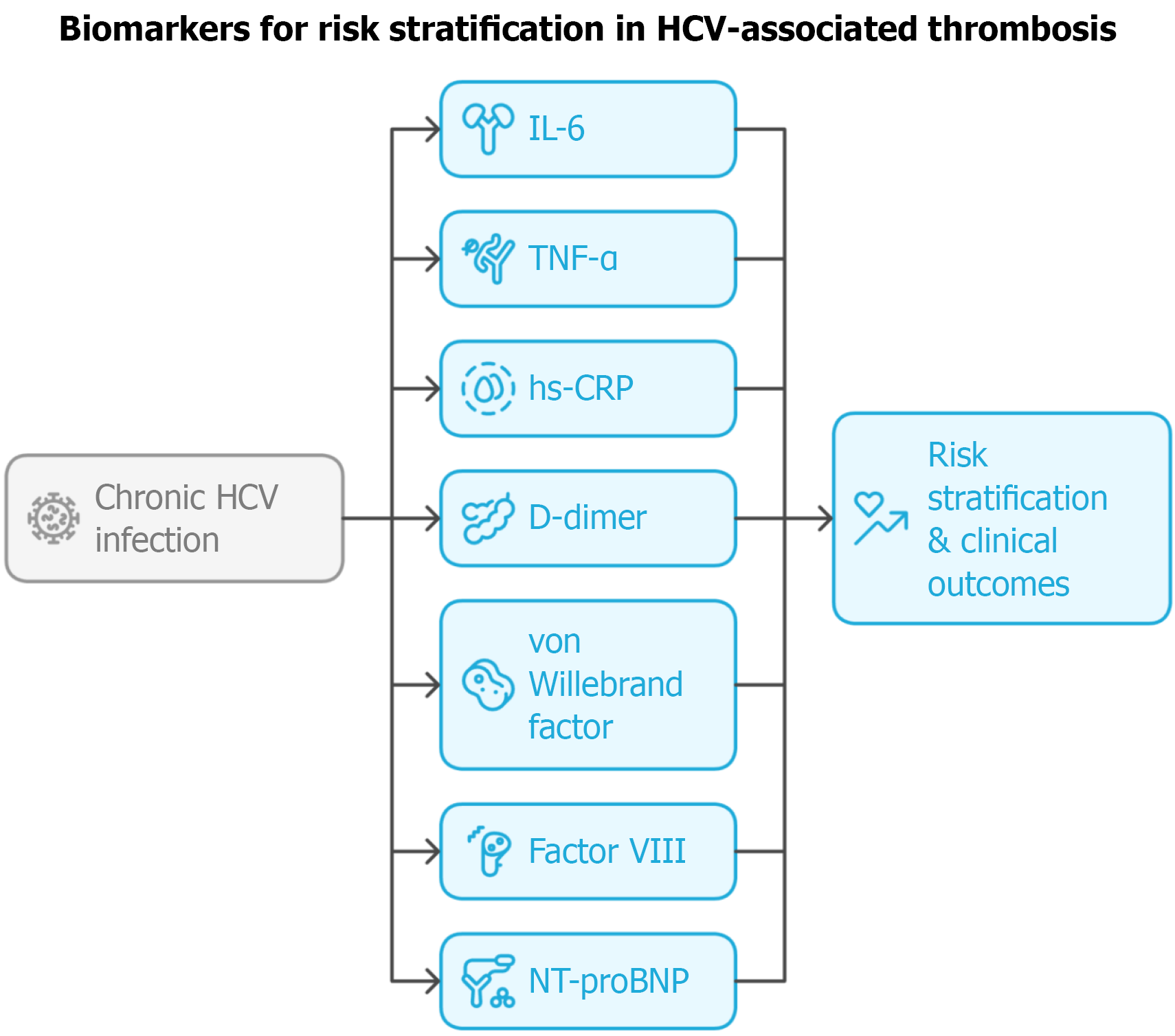

Several studies disagree on whether there is a correlation between HCV viral load and liver disease severity. It has been speculated that higher HCV titers are observed in patients with active hepatitis infection, which is more strongly correlated with increased liver damage and inflammation[35]. Prolonged infection may further elevate viral load, as seen in chronic hepatitis[35]. However, other retrospective cohort studies suggest that liver disease severity is independent of viral load and that there are similar incidences of HCV-related liver disease in patients with both high and low viral load levels[36]. Elevated viral load does increase the severity of the infection itself, but does not result in progression of hepatic dysfunction[36]. This is important to delineate that the severity of liver injury associated with HCV is less likely to be caused directly by the HCV itself, but by the immune system-mediated damage that we have presented here. In these cases, liver injury is thought to result directly from systemic inflammation and the viral-induced cytopathic effects of an overactive immune response, particularly through HCV-specific T-cell activation (Figure 2)[36,37]. Additionally, other confounding risk factors may be more relevant to the increased risk of HCV-related chronic liver disease and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma, including age of HCV infection, gender, alcohol use, and coinfection with HBV and HIV[37].

Figure 2 Biomarkers and risk stratification in hepatitis C virus-associated thrombosis.

Candidate biomarkers - including interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, D-dimer, von Willebrand factor, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, and factor VIII - may provide prognostic value for assessing cardiovascular and thrombotic risk in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. HCV: Hepatitis C virus; IL-6: Interleukin-6; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α; hs-CRP: High-sensitivity C-reactive protein; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptid.

UNRESOLVED QUESTIONS AND RESEARCH GAPS

Although several studies and meta-analyses have demonstrated a significant association between chronic HCV infection and thrombotic events[11,38], these associations have not been proven to be causal. Chronic HCV infection induces a prothrombotic state by promoting systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and alterations in coagulation pathways. Direct viral effects and immune-mediated injury led to increased expression of endothelial adhesion molecules, local vascular inflammation, and enhanced production of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), all of which contribute to endothelial activation and a procoagulant environment[39].

A multicenter retrospective cohort study demonstrated that individuals with chronic hepatitis C treated with DAAs experienced reduced rates of cardiovascular events compared to untreated patients, with the most notable reduction observed in VTE[40]. Similarly, Jeong et al[41] reported a reduced incidence of stroke following antiviral therapy. While such studies support a potential causal link between HCV eradication and reduced thrombotic risk, further research is needed to definitively establish causality, as confounding factors such as comorbid conditions may influence outcomes[38]. Prospective cohort studies and Mendelian randomization analyses are warranted to address this gap.

Currently, there are no established risk assessment scores specifically developed or validated for evaluating thrombotic risk in HCV infection. Existing tools, such as the CHA2DS2-VASc score, have limited applicability in this population, as mentioned in a comparative study[42]. Given the dynamic alterations in coagulation balance seen in cirrhosis, with simultaneous procoagulant and anticoagulant changes[43], there is a need for liver-specific thrombotic risk tools that integrate hepatic function (e.g., model for end-stage liver disease, Child-Pugh, platelet dynamics). Such tools could guide decisions regarding surveillance imaging and the use of prophylactic anticoagulation.

For hospitalized patients, the American Gastroenterological Association recommends general VTE risk assessment models, such as the Padua prediction score[44,45] and the International Medical Prevention Registry on Venous Thromboembolism VTE risk assessment model[46], to guide anticoagulation decisions[47]. However, no validated risk stratification tools currently exist for patients outside the hospital setting, underscoring the need for an HCV-specific risk assessment model.

Genetic predisposition and comorbidities also play significant roles in the development of thrombotic events in patients with HCV. Poujol-Robert et al[48] noted that genetic thrombophilias - such as protein C deficiency, elevated factor VIII, and hyperhomocysteinemia - are more frequently observed in HCV patients with advanced cirrhosis, and their coexistence markedly increases the risk of intrahepatic and systemic thrombotic events. A case-control study notes that prothrombotic genetic factors were also associated with extensive fibrosis and early cirrhosis, suggesting a synergistic effect between genetic predisposition and HCV-related hepatic injury in promoting thrombosis[48].

Comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, HIV, and cardiovascular disease are common in HCV-infected individuals and further amplify thrombotic risk. Diabetes mellitus is frequent in HCV and independently promotes vascular inflammation, endothelial activation, and atherosclerosis, thereby increasing thrombotic risk. HCV itself induces insulin resistance and metabolic disturbances, compounding this effect[49]. HIV infection has been associated with chronic immune activation, elevated levels of procoagulant markers (e.g., D-dimer, factor VIII), and reduced natural anticoagulants, which together create a hypercoagulable state[50]. As noted in a meta-analysis, patients with HCV/HIV co-infection have higher rates of thrombotic and cardiovascular events compared with either infection alone[50,51].

CONCLUSION

Chronic HCV infection is increasingly recognized as a prothrombotic condition. In clinical practice, thrombotic risk assessment in HCV largely relies on identifying conventional risk factors and applying clinical judgment, as no HCV-specific risk score exists. Epidemiological data indicate that older age and male sex, which are non-modifiable factors, significantly increase the risk of VTE in HCV-infected patients, suggesting these variables may be incorporated into future scoring tools[38]. Furthermore, HCV infection has been associated with elevated inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP)[52], TNF-α, IL-6, and endothelial dysfunction markers[16], all of which are linked to cardiovascular disease and may have predictive value in risk modeling. IL-6 is a proinflammatory cytokine that facilitates lymphocyte activation and proliferation, as well as the induction of hepatic synthesis of acute-phase reactants. TNF-α is another proinflammatory cytokine that promotes hepatic synthesis of acute-phase proteins, which in turn leads to activation of lymphocytes and endothelial cells. TNF-mediated signaling pathways are upregulated and activated in chronic hepatitis C, with TNF-α mRNA being widely expressed at elevated levels in hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, and infiltrating mononuclear cells of HCV patients. CRP is an acute-phase protein primarily synthesized by hepatocytes, with its production regulated mainly by both IL-6 and TNF-α. Elevated CRP levels are linked to underlying atherosclerosis and thus are an established marker for assessing cardiovascular disease risk in the general population. It also correlates with survival and mortality in both non-hepatitis C and cirrhotic hepatitis C patients. However, CRP levels are frequently lower than expected in chronic HCV infections, despite elevated IL-6 concentrations. This paradox is likely attributable to HCV-induced inhibition of hepatic CRP synthesis. Multiple studies have demonstrated that individuals with HCV exhibit reduced CRP levels compared to uninfected controls, even in the context of increased IL-6 and advanced liver fibrosis[53,54].

Currently, risk assessment in HCV-positive patients is performed using general VTE and cardiovascular risk models, as no HCV-specific tools exist. Standard VTE risk assessment in hospitalized patients relies on validated models such as the Padua prediction score[45], which incorporates age, comorbidities, and immobility but does not include HCV status as an independent variable. For cardiovascular risk, traditional calculators are used, though these may underestimate risk in HCV populations due to the additional inflammatory and metabolic burden of infection. Future directions include developing risk tools that integrate HCV-specific factors and biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction[16]. Such models could be incorporated into clinical guidelines to inform decisions on anticoagulation initiation and duration.

Historically, cirrhosis was considered a “naturally anticoagulated” state due to thrombocytopenia and reduced hepatic synthesis of clotting factors. This paradigm has shifted with recognition of a rebalanced but fragile hemostatic system, where declines in anticoagulant proteins (e.g., antithrombin III, protein C, protein S) and increases in procoagulant drivers (e.g., factor VIII, Willebrand factor) create vulnerability to both thrombosis and bleeding[18].

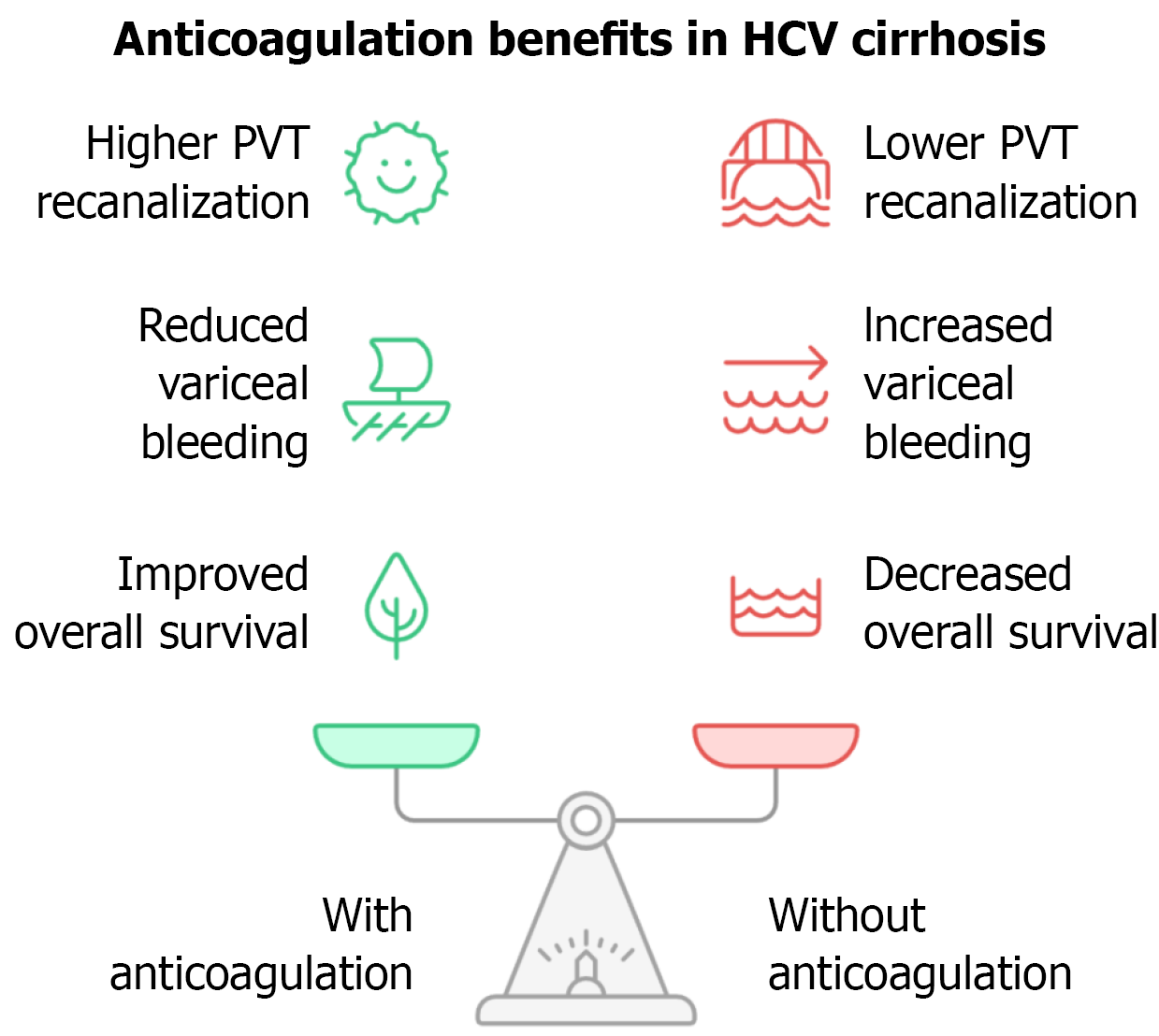

Modern guidelines recommend weighing thrombotic risk (e.g., atrial fibrillation, VTE, PVT) against bleeding risk, which is elevated in cirrhosis due to coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia[47]. A systematic review and meta-analysis found that PVT recanalization rates were significantly higher in anticoagulated patients compared with untreated patients (71% vs 42%, P < 0.0001), with no increase in overall bleeding risk and a reduced risk of variceal hemorrhage (P = 0.04; Figure 3).

Figure 3 Potential benefits of anticoagulation in hepatitis C virus cirrhosis.

Anticoagulation in patients with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis may reduce portal vein thrombosis, limit hepatic decompensation, and improve survival. HCV: Hepatitis C virus; PVT: Portal vein thrombosis.

The severity of liver disease (Child-Turcotte-Pugh class), presence of clinically significant coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia, and indication for anticoagulation (e.g., CHAD2S2-VASc score in atrial fibrillation) should all be considered. In compensated cirrhosis (Child-Pugh A or B) with a clear indication, anticoagulation is generally favored, while in advanced cirrhosis (Child-Pugh C), bleeding risk may outweigh benefits, requiring individualized decision-making[47].

Despite reduced antithrombin III levels in cirrhosis, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) remains the preferred agent[55]. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are effective and may be superior to warfarin for treating PVT in compensated cirrhosis[56]. The choice of anticoagulant is influenced by hepatic metabolism and the degree of liver dysfunction. DOACs are generally safe in Child-Pugh A and select Child-Pugh B cirrhosis but are contraindicated in Child-Pugh C due to impaired hepatic clearance and increased drug exposure[57]. Thus, anticoagulant choice (DOAC, LMWH, or vitamin K antagonist) should be individualized based on liver function, renal function, and patient preference[58].

Patients with cirrhosis are at elevated risk for VTE, with PVT occurring in approximately 8% annually among those on the liver transplant waitlist[59]. Anticoagulation, particularly in patients with more extensive mesenteric thrombosis, is associated with improved one-year outcomes[60]. Despite this, thromboprophylaxis - pharmacologic or mechanical - is often underutilized[61]. In a single-center, non-blinded randomized controlled trial, prophylactic LMWH reduced the risk of PVT (relative risk 0.05; P = 0.048) without increasing bleeding or mortality[60]. While bleeding concerns are prominent in advanced cirrhosis, studies suggest that upper gastrointestinal bleeding outcomes are more closely tied to the severity of organ failure and comorbidities than to anticoagulation itself[62].

Development of risk stratification tools would better equip clinicians to safely offer anticoagulation and thromboprophylaxis to select patients, even in advanced cirrhosis. A risk stratification tool for patients with HCV infection should integrate clinical, hemostatic, and inflammatory biomarkers to assess the ongoing risk of thrombogenesis. Perhaps interventional trials centered around anticoagulation in DAA-treated patients and untreated patients could shed light on this matter. The primary objectives of these trials would involve systematic monitoring of major bleeding episodes and thromboembolic events at 12-month intervals. Additionally, the studies would evaluate longitudinal changes in key coagulation biomarkers, including factor VIII, protein C, von Willebrand factor, and D-dimer levels. Endothelial function would be assessed through flow-mediated dilation measurements, and the incidence of PVT would be carefully documented to elucidate the vascular complications associated with the patient population under investigation. The potential mechanisms and clinical benefits of anticoagulation in HCV cirrhosis are summarized in Figure 3.

Future studies are needed to clarify the mechanistic and clinical links between HCV and thrombogenesis, with particular focus on the role of biomarkers and prospective clinical trials. Key priorities include large, prospective cohort studies that longitudinally measure inflammatory, endothelial, and coagulation biomarkers (e.g., CRP, IL-6, D-dimer, thrombin generation markers, and markers of endothelial dysfunction) in HCV populations, to assess their predictive value for venous and arterial thrombotic events, and their changes with antiviral therapy and HCV clearance[16,63].

There is also a need for prospective trials evaluating whether biomarker-guided risk stratification can improve outcomes by identifying high-risk HCV patients for targeted preventive interventions[16,63]. Mechanistic studies are warranted to dissect the pathways by which HCV-induced inflammation, immune activation, and endothelial injury drive hypercoagulability, and to determine whether distinct biomarker profiles are associated with specific thrombotic phenotypes[46]. Finally, randomized controlled trials are required to test whether interventions such as DAA therapy or anticoagulation reduce thrombotic risk in biomarker-defined high-risk populations[63]. Current evidence highlights the importance of integrating biomarker research with prospective clinical trials to advance risk prediction and management of thrombosis in HCV infection[16,63].

All in all, these novel scientific findings necessitate the translation of evidence into clinical practice, outlining specific responsibilities for physicians. Key clinical recommendations for hepatologists, cardiologists, and primary care providers include: Implementing universal HCV screening for all adults and high-risk populations, initiating DAA therapy promptly in all patients with confirmed chronic HCV infection, especially those with coexisting cardiovascular disease, evaluating and managing conventional cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with HCV, and fostering multidisciplinary collaboration to identify extrahepatic manifestations and enhance cardiovascular risk mitigation strategies[64]. With the increasing ability of primary care providers to manage HCV treatment, access to care has expanded, enabling earlier intervention - an essential step in reducing both hepatic and thrombotic complications[65].

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

Specialty type: Virology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade B

Novelty: Grade B, Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: Baltacı S, MD, Türkiye; Zhang JL, MD, PhD, Academic Fellow, FASCRS, China S-Editor: Hu XY L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xu ZH