Published online Dec 25, 2025. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v14.i4.111810

Revised: August 28, 2025

Accepted: September 17, 2025

Published online: December 25, 2025

Processing time: 168 Days and 22.6 Hours

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) recency testing provides data that can be used to monitor the trend of new HIV infections. The effectiveness of using people identified with recent infection to identify partners with new HIV infection through partner notification services (PNS) is not well documented.

To determine the pooled prevalence of recency testing coverage, recent infection, reclassification (recent to long-term infection) and PNS cascade among newly diagnosed people living with HIV.

PubMed, Cochrane Library and Embase were searched for articles published between January 2018 and November 2024. Studies were included if they reported recency coverage and/or PNS among people newly diagnosed with HIV and used recent infection testing algorithm (RITA). Recency coverage was defined as proportion of people tested using rapid testing for recent infection (RTRI) among those newly diagnosed with HIV. RITA further classifies RTRI results using viral load results (≥ 1000 copies/mL vs < 1000 copies/mL) to confirm recency status. For studies with PNS, we evaluated the cascade: Number of partners elicited, successfully contacted, eligible for HIV testing, tested and HIV diagnosis. PNS effectiveness was measured by proportion of new HIV diagnoses from tested partners. Using random effects models, we computed the pooled estimate of recency outcomes and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

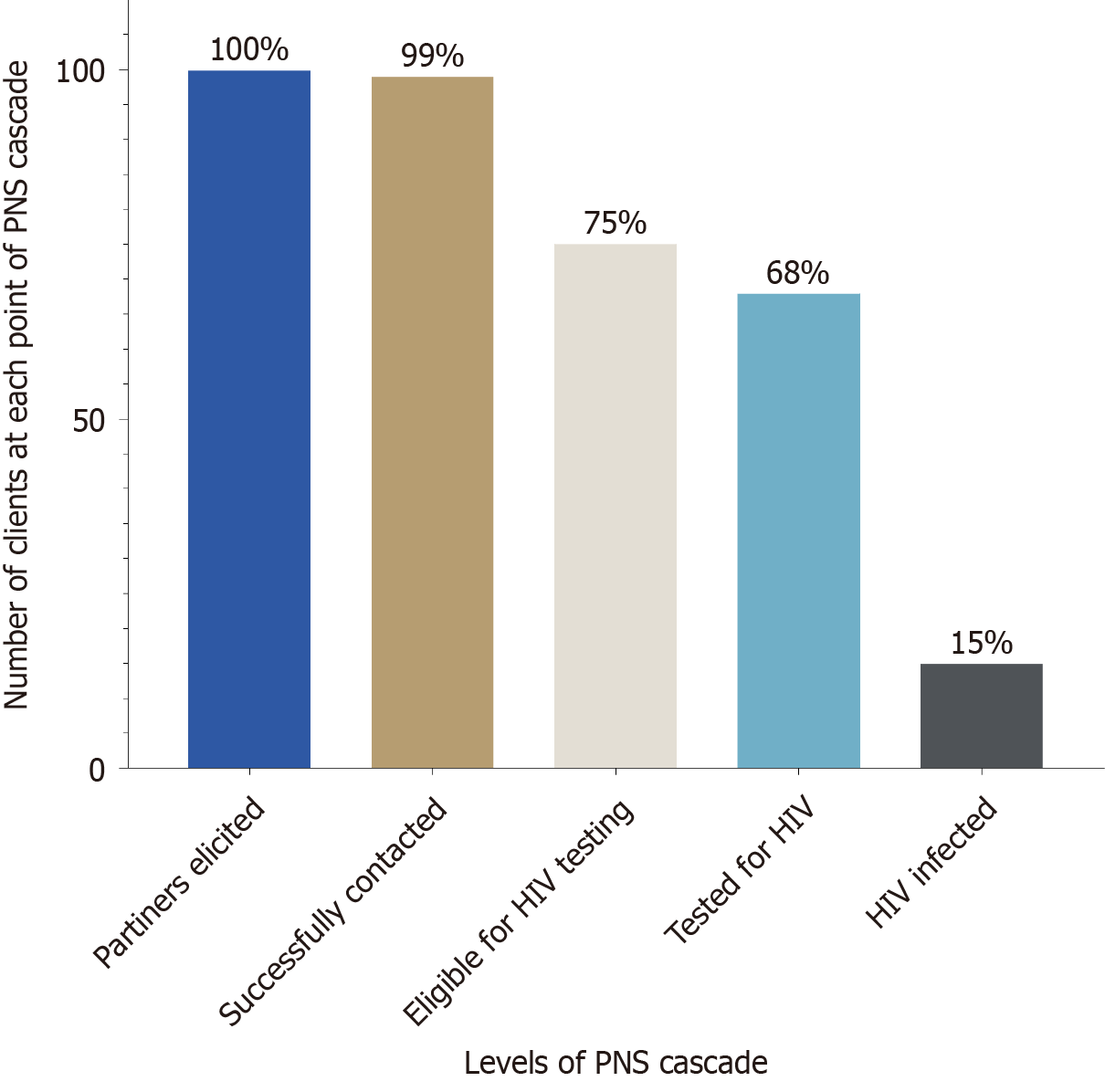

Twenty-five studies from 17-low- and middle-income countries were included. Of 276315 newly diagnosed people living with HIV, 79864 underwent RTRI with an overall pooled recency coverage of 87% (95%CI: 67-96). The pooled prevalence of RTRI and RITA recency were 12% (95%CI: 9-16) and 7% (95%CI: 4-10), respectively. Pooled prevalence of RTRI reclassification was 34% (95%CI: 22-49). Of the recent cases who agreed to PNS, 253 partners were elicited with an estimated elicitation ratio of 1:1.6. Among partners elicited, 99% were successfully contacted, 75% were eligible for testing, 68% tested for HIV, and 15% were diagnosed with HIV.

High recency testing coverage among newly diagnosed individuals demonstrates the feasibility of monitoring new HIV infections in LMIC. While PNS yielded moderate HIV diagnoses, its targeted approach remains a critical strategy for identifying undiagnosed cases.

Core Tip: This systematic review and meta-analysis synthesizes evidence from low- and middle-income countries on the implementation of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-recency testing and its integration with partner notification services (PNS). The findings highlight high but uneven rapid testing for recent infection (RTRI) coverage, moderate RTRI-recent prevalence, and substantial diagnostic misclassification. One in every three recent infections was reclassified as long-term following a viral load confirmatory testing. While PNS demonstrated strong partners contact rates and high HIV yield, critical attrition occurred throughout the cascade. These results highlight the value of RITA-confirmed recency testing and suggest that recency-informed PNS could enhance HIV surveillance and epidemic control when guided by standardized protocols and supported by confirmatory testing.

- Citation: El-Imam IA, Peter TA, Fussi HF, Ally ZM, Bakari HM, Mbwana MS, Chenya UK, Mpimo BK, Ally HM, Ramadhani HO. Human immunodeficiency virus recency testing coverage and partner-notification-services among people-living with human immunodeficiency virus in low- and middle-income countries. World J Virol 2025; 14(4): 111810

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3249/full/v14/i4/111810.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5501/wjv.v14.i4.111810

The global human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic remains a major public health challenge, with an estimated 39.9 million people living with HIV (PLWH) in 2022, disproportionately affecting low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)[1]. Although progress has been made towards the UNAIDS 95-95-95 targets - improving diagnoses, expanding antiretroviral therapy (ART) coverage, and achieving viral suppressions - significant gaps persist, particularly in the timely diagnosis of new infections and interrupt ongoing transmission[1-3]. Strengthening HIV surveillance and implementing targeted interventions are essential to identifying new infections and halting transmission, especially in high-incidence settings where health care access and prevention programs face systematic challenges.

HIV recency testing, designed to differentiate recent infection (acquired within the past 6-12 months) from long-standing infections, offers a promising tool to address these challenges[4-7]. By identifying individuals with recent infection at diagnosis, recency testing enabled public health program to target sub-populations and geographical areas where transmission is most active, thereby informing more effective public health intervention[3,4,8,9]. When integrated with partner notification services (PNS), recency testing can amplify the detection of undiagnosed infections, interrupt transmission chain and accelerate progress towards epidemic control[10-12].

Several LMIC’s have introduced recent infection surveillance within routine HIV testing services, often as part of national case-based surveillance systems[13-15]. However, the success and utility of recency-informed strategies depend heavily on achieving adequate recency testing coverage, accurately estimating the proportion of recent infections, and applying confirmatory tests to reduce misclassification. These operational metrics vary widely across programs and settings[13,14]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends using a recent infection testing algorithm (RITA), which combines a rapid test for recent infection (RTRI) with supplementary viral load testing to minimize false recent results and ensure reliable estimates, particularly in LMIC’s where ART coverage is expanding[4,6,10].

A critical application of recent testing lies in optimizing PNS outcomes[10,11]. Individuals with recent infections often have high viral loads and are unaware of their status, increasing their risk of transmitting HIV[8,13]. Identifying such index cases allows programs to prioritize partners elicitation and testing, leading to earlier diagnosis, linkage to care, and prevention intervention for partners[11,16,17]. This integration has been shown to improve efficacy along the entire PNS Cascade, from partner elicitation through HIV positivity yield[18,19], which is critical for maximizing limited resource in high-burden resource-constrained low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Despite increasing implementation of recency testing and PNS in LMIC’s, no comprehensive synthesis has pooled quantitative outcomes across diverse settings. This systematic review and meta-analysis address this gap by estimating pooled prevalence of recency testing coverage, recent infection rates, reclassification from recent to long-term infection, and PNS cascade outcomes among newly diagnosed PLWH in LMIC. Our findings will inform national HIV strategies, guide targeted prevention programs, and optimize resource allocation in LMICS to achieve epidemic control.

The protocol for this systematic review was registered in the International Prospective Register of systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under registration number CRD420251081733. The review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.

As this study involved secondary analysis of published studies and programmatic reports ethical approval was not required.

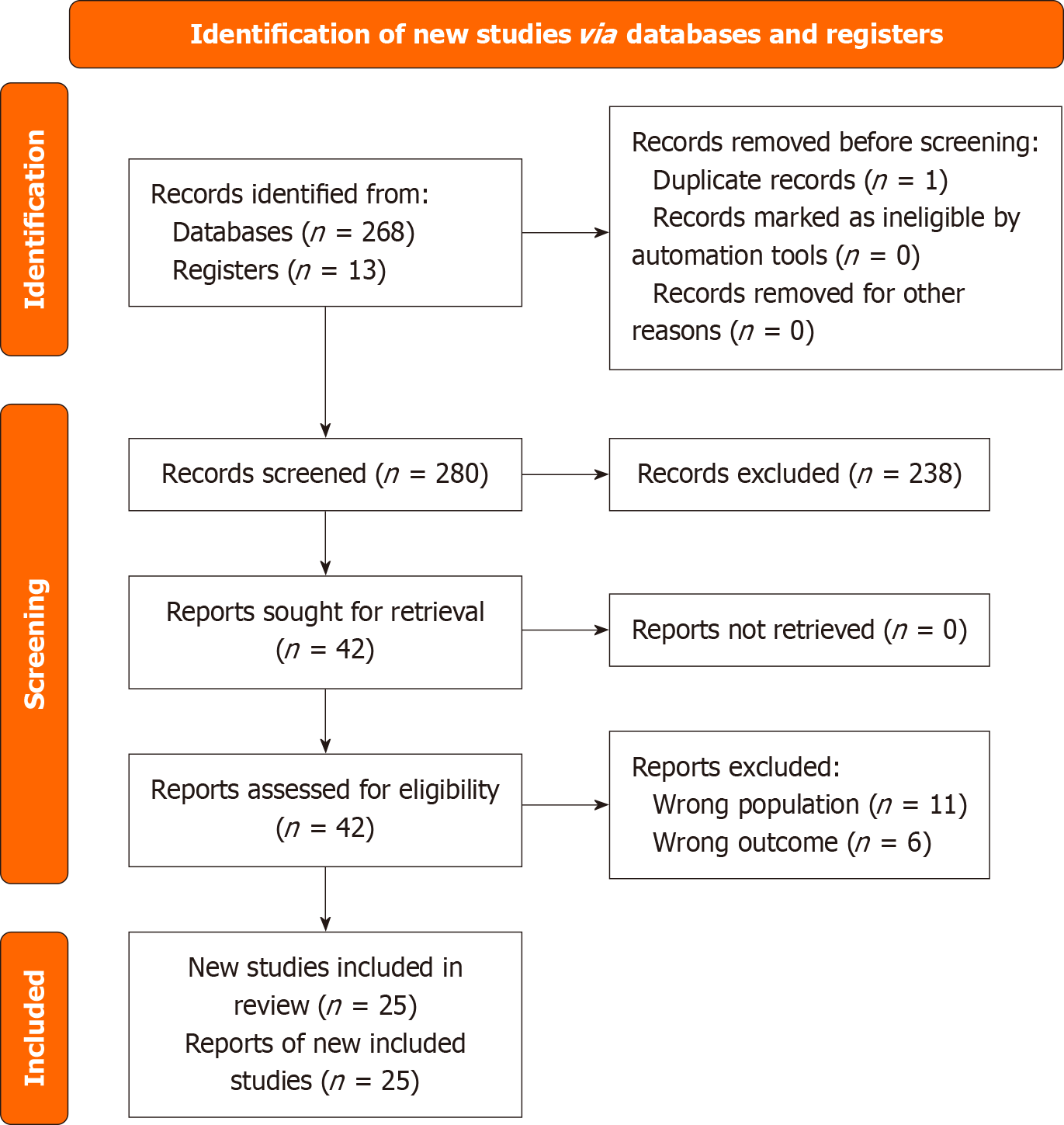

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library for studies published between January 1, 2018, and November 30, 2024, using combinations of keywords and MeSH terms related to HIV recency testing, the RITA RTRI and PNS including index testing, contact tracing, and elicitation. The search strategy focused on LMIC’s and included only English-language publications. The databases search yielded 268 records. We also identified 13 additional records through manual searches of conference abstracts and grey literature sources, bringing the total to 281 records. The full search was conducted on May 13, 2025.

We uploaded the records from electronic data bases into Rayyan software for deduplication and screening. Of the 281 records, we identified two duplicates manually removed one and ultimately included 280 records before initiating the screening process detail. Search strategies are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

We included studies that reported on any component of the HIV recency testing cascade or the PNS cascade among newly diagnosed PLWH in LMICs. Eligible recency cascade elements included initial testing for recent infection, classification, or reclassification to long-term infections, and confirmatory viral load results. Recency testing coverage was defined as the proportion of newly diagnosed individuals who received RTRI at the point of HIV diagnosis. Studies were required to have implemented RITA which combines an initial recency assay (such as RTRI, Lag avidity EIA, or another validated serological method) with confirmatory viral load testing (≥ 1000 copies/mL) in accordance with WHO guidance to be considered for reclassification from recent to long-term infection[4].

Studies were also eligible if they reported on PNS outcomes including the number of sexual/needle sharing partners elicited, successfully contacted, found eligible for testing, tested for, and diagnosed with HIV. Only studies conducted in LMICS among newly diagnosed PLWH were included. We excluded studies that did not report any relevant recency testing or PNS data, studies that were non-primary (e.g., reviews, editorials, commentaries), those conducted in ineligible population and those lacking sufficient quantitative data for extraction.

Two reviewers independently screened all 280 records for eligibility using Rayyan. After title and abstract screening, we excluded 238 records. We sought full texts for the remaining 42 records, all of which were successfully retrieved. We assessed these 42 full-text articles for eligibility and excluded 17 articles, 11 due to inclusion of the wrong population and six due to irrelevant outcomes.

At each stage of review, discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus. Ultimately, we included 25 studies in the final analysis. These included both peer-reviewed publication and high-quality conference abstracts that met all inclusion criteria despite the absence of full manuscripts. The PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (Figure 1) summarizes the selection process.

Data were independently extracted by two reviewers using a pre-defined Excel template. Extracted data included study author and year of publication, country and setting, study design, and sample characteristics. Recency testing indicators included the number of newly diagnosed individual, number tested with RTRI, coverage of RTRI testing, number of cases reclassified from recent to long-term infection, and details of the reclassification process. For PNS, extracted outcomes include the number of partners elicited, successfully contacted, tested for HIV, found eligible for HIV testing, and diagnosed with HIV. PNS effectiveness was measured as the proportion of newly diagnosed HIV positive partners among those tested. Any discrepancies in data extraction were discoursed and resolved by consensus.

The methodological quality of included studies was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tools for observational studies. The tool consists of nine questions with four responses: (Yes, No, Not clear, Not applicable). We assigned a score of 1 to a “Yes” response and 0 to a “No” response. Each scored question was totaled and classified into three categories. Studies with (0-3), (4-6) and (7-9) scores were regarded as being of low, medium and high quality respectively. Two pairs of reviewers (Beatrice Kelvin Mpimo and Haji Mbwana Ally) and (Hassan Fredrick Fussi and Upendo Kayeke Chenya) independently performed and rated the quality of the studies using the JBI tools. Discrepancies of the scores between the two pairs were sorted by a third pair of reviewers (Habib Ramadhani Omari and Hafidha Mhando Bakari).

The primary outcomes of interests were recency testing coverage at point-of-care, prevalence of RTRI-recent infection, prevalence of RITA-recent infection, and the proportion of RTRI-recent cases reclassified as long-term infections based on confirmatory viral load results. Furthermore, we also reported the proportion of individuals successfully reached across the PNS Cascade including elicitation ratio, prevalence of partners of recent HIV cases who were successfully contacted, prevalence of partners of recent HIV cases who were eligible for HIV testing, prevalence of partners of recent HIV cases who tested for HIV, and prevalence of partners of recent HIV cases who were diagnosed with HIV. The secondary outcome was the effectiveness of partner notification, measured as the proportion of tested partners who were newly diagnosed with HIV.

Using random and fixed effects models, we computed pooled prevalence of HIV recency testing uptake, RTRI-recent infection, RITA-recent and reclassification from recent to long-term HIV infections. Additionally, we also evaluated PNS cascade by quantifying several components of the cascade including elicitation ratio, prevalence of partners of recent HIV cases who were successfully contacted, prevalence of partners of recent HIV cases who were eligible for HIV testing, prevalence of partners of recent HIV cases who tested for HIV, and prevalence of partners of recent HIV cases who were diagnosed with HIV. Subgroup analysis on the pooled estimates of RTRI and RITA prevalence were performed to compare studies conducted from surveys/Laboratory samples vs those conducted from HIV programs using χ2 tests. Studies heterogeneity was assessed by computing the I2 statistic and Cochran’s Q. The score values of I2 statistics were categorized at 75%, 50% and 25% to signify the presence of high, moderate and low heterogeneity respectively as previously described[20]. To assess publication bias, the Egger regression asymmetry test was used. To declare the presence of either heterogeneity or publication bias, a P value threshold of < 0.05 was used. For the prevalence outcome that showed either moderate or high degree of heterogeneity, we assessed its possible sources by conducting an influential analysis using the leave-one-out method[21]. In addition, we conducted a meta regression analysis to discern the variation of the HIV recency testing uptake. Using trim-and-fill method, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess possible small-study. All statistical tests were performed using R version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Australia).

Our search identified a total of 281 records comprising 268 from databases and 13 from manual sources. After dedup

Assessment of study quality showed that all studies were of high quality, with scores ranging from 7-9. Those with scores less than 9, the common reasons were smaller sample size and a response rate of less than 80%. Neither study was of low nor medium quality (Table 1).

| Ref. | Country | Data source | Number of newly diagnosed | Number of people received RTRI test | RTRI coverage | Prevalence of RTRI recent infection | Prevalence of RITA recent infection | Prevalence of Reclassification from recent to long-term infection | Quality scores |

| Truong et al[14], 2022 | Eswatini, Nigeria, Rwanda, Thailand, Uganda, Vietnam, Zambia | HIV program | 231410 | 41688 | 18.0 | 8 | |||

| Aungkulanon et al[22], 2022 | Bangkok | HIV program | 1291 | 694 | 53.8 | 8.5 | 7.8 | 8.5 | 8 |

| Simanovong et al[23], 2022 | Thailand | HIV program | 196 | 153 | 78.1 | 4.6 | 3.9 | 14.3 | 7 |

| Okiror et al[37], 20241 | Uganda | HIV program | - | - | - | - | - | - | 7 |

| Herce et al[28], 2024 | Zambia | HIV program | 344 | 322 | 93.6 | - | 3.2 | - | 9 |

| Mochama et al[17], 20241 | Kenya | HIV program | - | - | - | - | - | - | 8 |

| Ouk et al[18], 20221 | Cambodia | HIV program | - | - | - | - | - | - | 7 |

| Lerdtriphop et al[19], 20221 | Thailand | HIV program | - | - | - | - | - | - | 8 |

| Rice et al[12], 2020 | Kenya and Zimbabwe | HIV program | 1582 | 1269 | 80.2 | 16.9 | 7.2 | 5.9 | 9 |

| Negedu-Momoh et al[29], 2021 | Nigeria | Survey | - | - | - | 5.1 | 3.0 | 4.2 | 9 |

| Welty et al[16], 2020 | Kenya | HIV program | 628 | 532 | 84.7 | 11.7 | 9.4 | 19.4 | 9 |

| Voetsch et al[5], 2021 | ≥ 10 countries2 | Survey | - | - | - | 10.3 | 1.5 | - | 9 |

| Rwibasira et al[24], 2021 | Rwanda | HIV program | 10701 | 7919 | 74.0 | 9.5 | 6.0 | 36.4 | 8 |

| Mohloanyane et al[35], 2023 | Lesotho | Survey | - | - | - | 9.9 | 7.4 | 25.0 | 9 |

| Alemu et al[25], 2022 | Ethiopia | HIV program | 5689 | 3129 | 55.0 | - | 14.2 | - | 8 |

| Parmley et al[30], 2022 | Zimbabwe | Survey | - | - | - | 8.6 | 1.1 | 87.5 | 7 |

| Young et al[31], 2023 | Kenya | Survey | - | - | - | 11.8 | 5.6 | 86.6 | 8 |

| Telford et al[8], 2022 | Malawi | HIV program | 9295 | 9168 | 98.6 | 6.1 | 3.3 | 45.3 | 9 |

| Ang et al[32], 2021 | Singapore | Survey | - | - | - | 25.7 | 19.0 | 26.1 | 8 |

| Msukwa et al[26], 2020 | Malawi | HIV program | 14022 | 13838 | 98.7 | 6.3 | 3.2 | 43.1 | 9 |

| Agyeman et al[33], 2022 | Malawi | HIV program | - | - | - | 19.7 | 13.9 | 29.3 | 8 |

| Singh et al[34], 2023 | South Africa | Laboratory | - | - | - | 43.0 | 38.6 | 10.3 | 8 |

| Zhou et al[36], 2023 | China | HIV program | - | - | - | - | 19.5 | - | 7 |

| Saito et al[11], 20231 | Rwanda | HIV program | - | - | - | - | - | - | 7 |

| Zhu et al[27], 2020 | China | HIV program | 1157 | 1152 | 99.6 | 17.9 | 15.1 | 15.1 | 9 |

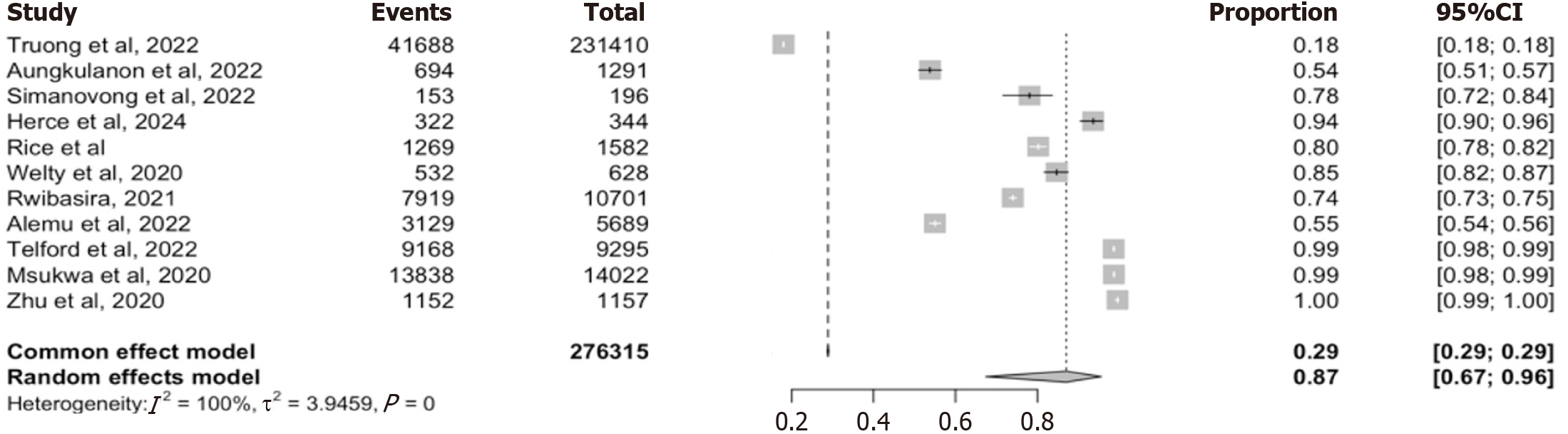

We included 11 studies reporting on HIV recency testing coverage using RTRI at point-of -care[8,12,14,16,22-28]. The studies spanned diverse geographic and programmatic settings within low- and middle-income countries and repre

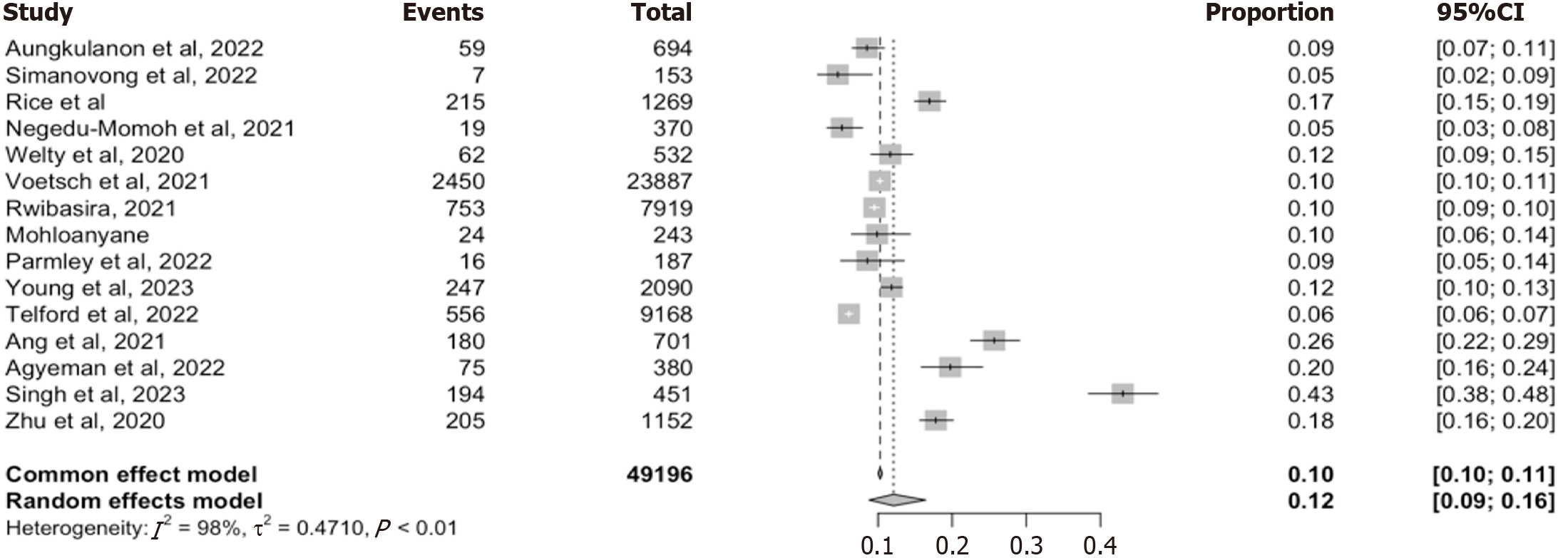

We included 15 studies that reported the proportion of individuals testing recent for HIV infection using either RTRI, or other validated recency assays, such as limiting antigen avidity immunoassay (Lag-Avidity)[5,8,12,16,22-24,27,29-35]. These studies together represented a combined sample size of 49196 newly diagnosed PLWH across diverse, LMICs settings.

The pooled estimate from the random-effect model was 12% (95%CI: 9-16), while the fixed effect model produced a slightly lower estimate of 10% (95%CI: 10-11). The point estimate from individual studies varied widely, ranging from 5% to 4.3% (Figure 3). There was substantial heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 98%. τ2 = 0.4710, P < 0.01) suggesting considerable variability in testing approaches and populations.

To assess the robustness of this finding, we conducted a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis, which showed no significant deviation in the pooled estimates when each study was omitted in turn (range: 0.1 to 0.11; Supplementary Figure 2). This indicates that the summary estimate was not driven by any single influential study. We further stratified the analysis by data source, distinguishing between programmatic- (n = 8 studies) and laboratory/survey-based (n = 7 studies) data and the pooled estimates were 11% (95%CI: 8%-15%) and 14% (95%CI: 8%-23%) respectively. Nonetheless, the test for subgroup differences using the random effect model was not statistically significant (χ2 = 0.43, df = 1, P = 0.51) (Table 2), indicating no meaningful differences between the two data sources. Thus, indicating a moderate but consistent burden of RTRI-recent infection among newly diagnosed individual in LMIC’s with variation by study context other than data source.

| Sources of data | P value | ||

| HIV program, % (95%CI) | Laboratory/surveys, % (95%CI) | ||

| RTRI-recent HIV infection | 11 (8-10) | 14 (8-23) | 0.510 |

| RITA-recent HIV infection | 6 (5-6) | 5 (2-13) | 0.440 |

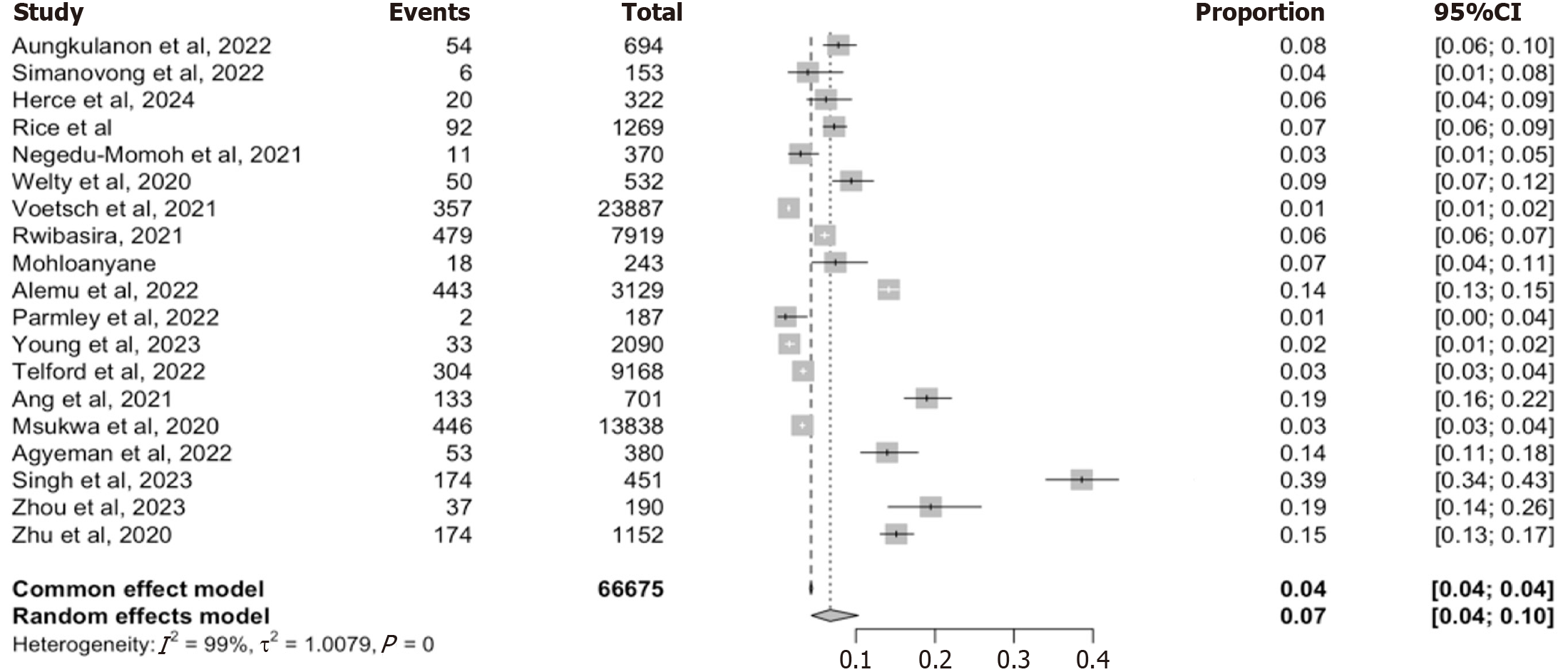

Eighteen studies reported on the prevalence of recent infection using a WHO-defined RITA, which incorporated an initial recency assay with a confirmatory viral load testing (≥ 1000 copies/mL)[5,8,12,16,22-36]. These studies collectively evaluated 66675 individuals. RITA-recent prevalence from individual study ranged from 1% to 39%, with an overall pooled prevalence of 7% (95%CI: 4-10) from the random-effect model and 4 (95%CI: 0.04-0.04) from the fixed effects model. High heterogeneity among the included studies was observed (I2 = 99%. τ2 = 1.0079, P < 0.001) reflecting that the variation observed across studies could not be explained by chance alone (Figure 4).

To assess the robustness of this pooled estimate, we conducted an influential analysis using a leave-one-out approach (Supplementary Figure 3). The pooled prevalence remained consistently between 4% and 6%, regardless of which study was omitted, suggesting that no single study exerted undue influence on the overall estimate. Heterogeneity measures remain unchanged across iterations (I2 = 99%, τ2 = 1.0079) reinforcing the stability of the model. A subgroup analysis was further performed to explore whether the source of data contributed to the observed heterogeneity. Among the 7 programmatic studies the pooled prevalence was 6% (95%CI: 5-6), while the 7 Laboratory/survey-based studies yielded a slightly lower estimate of 5% (95%CI: 2-13) (Table 2). However, the test for subgroup differences using the random effect model failed to reach statistical significance (χ2 = 0.60, df = 1, P = 0.44), implying that the data source alone does not explain the heterogeneity. Together, this analysis confirm that while the pooled prevalence of RITA-recent infection is approximately 7%, substantial variability exists across studies, likely due to differences in population characteristics, implementation fidelity and recency assay protocol.

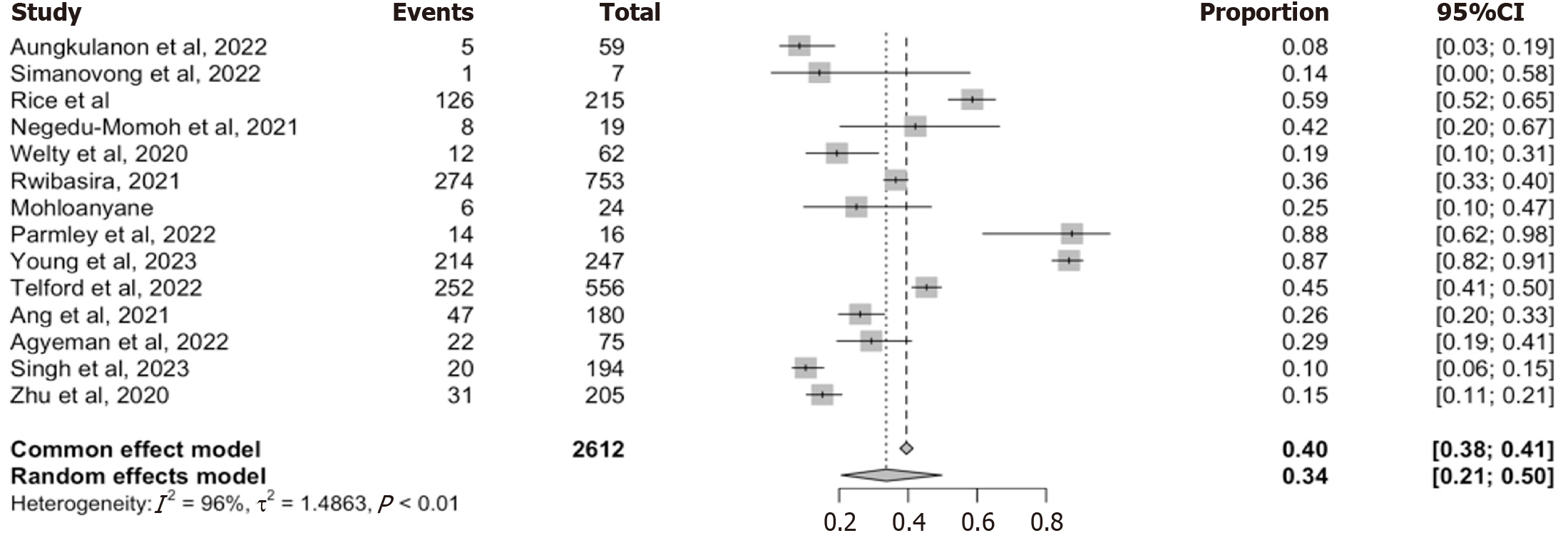

Fourteen studies reported on the proportion of individuals initially classified as recent who were reclassified as long-term after confirmatory viral load testing. Together, these studies encompass a total of 2612 individuals identified as recent prior to viral load confirmation, with a reclassification rate ranging from 8% to 88% (Figure 5). The random-effect pooled estimate was 34% (95%CI: 21-50), while the fixed-effects model yielded a slightly higher and more precise estimate of 0.40 (95%CI: 38-41). Heterogeneity across studies was high (I2 = 96%, τ2 = 1.4863, P < 0.01) reflecting differences in ART exposure, testing timing, and viral load suppression.

To assess whether any single study disproportionately influenced the pooled estimates, we performed a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Figure 4). The pooled reclassification estimates remain relatively stable, ranging between 38% and 42% when individual studies were excluded one at a time. All recalculated heterogeneity statistics remain high, reinforcing the robustness of the pooled estimates while also underscoring persistent heterogeneity in the data. These findings confirm that approximately one-third of the individuals initially identified as recent are ultimately reclassified as long-term infections. This high reclassification rate underscores the critical role of viral load confirmation in RITA and may signal gaps in identifying true recent infection in high-ART coverage settings.

Proportion of partners successfully contacted: Five studies reported this indicator[17-19,28,37], with a pooled random-effect estimate of 99% (95%CI: 67-100) and fixed-effects estimates of 96% (95%CI: 93-98). Heterogeneity was low (I2 = 11%, τ2 = 11.2974, P = 0.34) suggesting high and consistent success in partners contacts (Figure 6).

Proportion of partners eligible for HIV testing: The pooled random-effects estimates across five studies was 75% (95%CI: 59-86) (Figure 6), while the fixed effects estimates was 76% (95%CI: 70-0.81). Heterogeneity was moderate-to-high (I2 = 84%, τ2 = 0.5361, P < 0.01), likely reflecting differing definitions and population characteristics.

Proportion of eligible partners tested for HIV: Among partners eligible for testing, the pooled random-effect estimate was 68% (95%CI: 56-79) (Figure 6). The fixed effects estimates was 69% (95%CI: 63-75), with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 75%, τ2 = 0.2507, P < 0.01).

Prevalence of HIV among tested partners: Across five studies, the pooled HIV prevalence among tested partners was 15% (95%CI: 10-22) (Figure 6) using a random-effects model and 15% (95%CI: 11-20) using a fixed effect-model. Heterogeneity was low (I2 = 39%, τ2 = 0.0906, P = 0.16).

Collectively, these results demonstrate variable performance across the HIV recency testing and PNS Cascades, with strong partner tracing outcome, but more modest testing uptake and case detection.

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to synthesize current evidence on the implementation and performance of HIV recency testing and its integration with PNS among newly diagnosed individuals in LMICs. Our findings provide critical insights into testing coverage, diagnostic accuracy, and programmatic impacts, while identifying key gaps that must be addressed to strengthen epidemic control efforts.

The high RTRI coverage of 87% across 11 studies demonstrates substantial integration of recency testing into routine HIV services in many LMICs. High RTRI uptake is crucial for implementing real-time surveillance and response to ongoing HIV transmission. However, the wide range in coverage estimates (range: 18%-100%) raise concerns about programmatic consistency and scalability. This finding is in line with earlier reports from programs in Kenya, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Rwanda[10,12,16,24,28], where coverage was influenced by policy adoption, training quality and test kits availability. The results suggest that while national programs may report high RTRI uptake, subnational heterogeneity remains a key challenge. Programs must therefore strengthen coverage equity across districts, improving training and addressing logistical constraints to maximize the utility of recent infection surveillance.

Our meta-analysis reveals critical insights about HIV recency testing’s utility and limitations in LMICs. The pooled prevalence of 12% based on RTRI results from 15 studies encompassing over 49000 newly diagnosed individuals across LMICs highlights a moderate but epidemiologically meaningful burden of likely incidents infections, consistent with reports from Kenya, Malawi and Rwanda (> 10%)[5,12,16,24]. However, when restricted to studies using the WHO-recommended RITA, the pooled prevalence declined to 7% across 18 studies with 66675 individuals. This 42% reduction demonstrates the critical role of viral load confirmation in excluding false-recent cases, and exposes RTRI vulnerability to misclassification, particularly in high-ART coverage settings where early treatments and rapid viral suppression are common[8,24,29-31,33].

The discrepancy between RTRI and RITA estimates is further clarified by our pooled reclassification rate of 34% across 14 studies, including 2612 individuals, indicating that nearly one in three individuals initially classified as recent were ultimately deemed long-term after VL testing. These findings reinforce previous observations from Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda and Nigeria, where unconfirmed recency testing led to overestimation of recent infections and misdirected prevention efforts[8,24,29-31]. High heterogeneity observed in all three analyses likely reflects contextual and operational variability, including diverse recency assays, ART coverage levels, differences in VL suppression rates, implementation fidelity of VL testing, and variation in data type (Facility vs community-based). Notably, our sensitivity analysis revealed that no single study unduly influenced the pooled estimates, and that there were no significant prevalence differences between programmatic and research settings. These findings further affirm that real-world data, when rigorously collected, can yield reliable surveillance estimates[10-12], which supports the WHO endorsement of recency testing for dynamic surveillance, but underscores that its accuracy hinges on confirmatory testing infrastructure[7,10].

For public health programs, these findings carry important implications - while RTRI provide an accessible tool for transmission hotspots identification, its stand-alone use possess substantial misclassification risks in high-ART-coverage setting potentially distorting resource allocation[28,38]. In contrast, despite RITA's superior accuracy, implementation barriers persist - particularly VL processing delays and decentralized testing infrastructures that hinder timely recency classification[30,39]. National programs must therefore prioritize fidelity to RITA protocols, ensuring timely VL-testing and results return and integrate recent infection surveillance with partner services and outbreak response mechanisms[40]. Emerging solutions like multi-assay algorithm (Sedia HIV recency assay) and machine learning approaches in

Our meta-analysis highlights both the strengths and persistent gaps in PNS implementation across LMIC, with impli

The substantial 15% HIV prevalence among tested partners - nearly triple typical general population testing yields[47-49], confirms PNS as a high value case-finding strategy. This prevalence closely corresponds with our finding of 12% RTRI-recent infections among index cases, suggesting PNS effectively captures active transmission networks. However, the 34% RTRI-RITA reclassification rates introduce a critical programmatic consideration: Partners of virally suppressed index cases (likely long-term infection) may represent established rather than acute infections, potentially diluting PNS’s outbreak interception value[5,17,30]. To optimize impact, programs should prioritize integrating RTRI-screening with confirmatory RITA testing to strategically direct PNS resources towards truly viremic index cases most likely to yield recent partner infection[10,11]. Concurrently, standardizing eligibility criteria and testing protocols could substantially reduce the observed cascade attrition while improving cross-program comparability. Finally, given the elevated trans

This study provides the most comprehensive evaluations to date of integrated HIV recency testing and partner notification services across LMIC’s, synthesizing data from 25 studies encompassing tens of thousands of newly diagnosed individuals. Its principal strength lies in the novel integration of recency and PNS cascade analysis, revealing critical intersections between diagnostic accuracy and intervention effectiveness that previous studies have addressed separately. The applications of both random- and fixed-effect models with rigorous sensitivity analysis enhance the robustness of findings, while the consistent HIV prevalence among tested partners across diverse settings validates the epidemiological utility of well implemented PNS programs. Furthermore, our inclusion of both programmatic and research data provides unique insights into real-world implementation challenges and best practices.

We acknowledged several limitations in the study including substantial heterogeneity (I2 = up to 100%) across many analyses despite subgroup explorations, reflecting unavoidable variations in recency assay performance, PNS eligibility criteria, and program maturity levels. While our modeling approaches accounted for this variability, residual con

Based on these findings, we propose 3 priority actions for programs: (1) Implementation of tiered recency testing protocols that prioritize RITA-confirmed cases for PNS resource allocation; (2) Standardizations of PNS eligibility criteria and quality metrics across programs to reduce cascade attrition; and (3) Investments in point of care viral load platforms to minimize confirmation delays. Future research should focus on the following key areas, cost effectiveness analysis of integrated recency PNS models, validation of next generation multi-assay algorithms in routine care settings, and implementation science studies to optimize approaches for key populations currently underrepresented in recent infection surveillance (particularly Men who have Sex with Men & People Who Inject Drugs). This meta-analysis demon

| 1. | UNAIDS. 2024 global AIDS report - The Urgency of Now: AIDS at a Crossroads | UNAIDS [Internet]. 2024 [cited June 24, 2025]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2024/global-aids-update-2024. |

| 2. | Frescura L, Godfrey-Faussett P, Feizzadeh A A, El-Sadr W, Syarif O, Ghys PD; on and behalf of the 2025 testing treatment target Working Group. Achieving the 95 95 95 targets for all: A pathway to ending AIDS. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0272405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 65.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Stephens R, Mfungwe H, Chalira D, Luhanga M, Theu J, Thawi R, Chapman K, Singano V, Jere J, Blair C, O'Malley G, Patel M, Ernst A, Hassan R, Kabaghe A, Arons MM. Notes from the Field: Public Health Response to Surveillance for Recent HIV Infections - Malawi, May 2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2025;74:355-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | World Health Organization. Using recency assays for HIV surveillance: 2022 technical guidance [Internet]. 2022 [cited June 24, 2025]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240064379. |

| 5. | Voetsch AC, Duong YT, Stupp P, Saito S, McCracken S, Dobbs T, Winterhalter FS, Williams DB, Mengistu A, Mugurungi O, Chikwanda P, Musuka G, Ndongmo CB, Dlamini S, Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha H, Pasipamire M, Tegbaru B, Eshetu F, Biraro S, Ward J, Aibo D, Kabala A, Mgomella GS, Malewo O, Mushi J, Payne D, Mengistu Y, Asiimwe F, Shang JD, Dokubo EK, Eno LT, Zoung-Kanyi Bissek AC, Kingwara L, Junghae M, Kiiru JN, Mwesigwa RCN, Balachandra S, Lobognon R, Kampira E, Detorio M, Yufenyuy EL, Brown K, Patel HK, Parekh BS. HIV-1 Recent Infection Testing Algorithm With Antiretroviral Drug Detection to Improve Accuracy of Incidence Estimates. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;87:S73-S80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sedia Biosciences Corporation. Asanté® HIV-1 Rapid Recency® - Sedia Biosciences [Internet]. [cited June 24, 2025]. Available from: https://www.sediabio.com/asante-hiv-1-rapid-recency/. |

| 7. | Yufenyuy EL, Detorio M, Dobbs T, Patel HK, Jackson K, Vedapuri S, Parekh BS. Performance evaluation of the Asante Rapid Recency Assay for verification of HIV diagnosis and detection of recent HIV-1 infections: Implications for epidemic control. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2022;2:e0000316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Telford CT, Tessema Z, Msukwa M, Arons MM, Theu J, Bangara FF, Ernst A, Welty S, O'Malley G, Dobbs T, Shanmugam V, Kabaghe A, Dale H, Wadonda-Kabondo N, Gugsa S, Kim A, Bello G, Eaton JW, Jahn A, Nyirenda R, Parekh BS, Shiraishi RW, Kim E, Tobias JL, Curran KG, Payne D, Auld AF. Geospatial Transmission Hotspots of Recent HIV Infection - Malawi, October 2019-March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:329-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Srithanaviboonchai K, Yingyong T, Tasaneeyapan T, Suparak S, Jantaramanee S, Roudreo B, Tanpradech S, Chuayen J, Kanphukiew A, Naiwatanakul T, Aungkulanon S, Martin M, Yang C, Parekh B, Northbrook SC. Establishment, Implementation, Initial Outcomes, and Lessons Learned from Recent HIV Infection Surveillance Using a Rapid Test for Recent Infection Among Persons Newly Diagnosed With HIV in Thailand: Implementation Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2024;10:e65124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rwanda Biomedical Center I at CU. HIV recency testing, positivity yield, and intimate partner violence among persons newly diagnosed with HIV: Findings from the Rwanda HIV recency evaluation study. Kigali, Rwanda; 2024 Jan [Internet]. [accessed June 24, 2025]. In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): U.S. National Library of Medicine. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05063487. |

| 11. | Saito S, Reid G, Poirot E, Irabona JC, Kamanzi C, Mugisha V, Sangwayire B, Remera E, Oluoch T, Mwesigwa R, Tuyishime E, Lee K, Miller DA, Suthar AB, Rwibasira GN. HIV recency testing with index testing can identify new infections earlier in Rwanda. Top Antiviral Med [Internet]. 2023; 31: 82. U2-L641190195. Available from: https://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&id=L641190195&from=export. |

| 12. | Rice BD, de Wit M, Welty S, Risher K, Cowan FM, Murphy G, Chabata ST, Waruiru W, Magutshwa S, Motoku J, Kwaro D, Ochieng B, Reniers G, Rutherford G. Can HIV recent infection surveillance help us better understand where primary prevention efforts should be targeted? Results of three pilots integrating a recent infection testing algorithm into routine programme activities in Kenya and Zimbabwe. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23 Suppl 3:e25513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim AA, Behel S, Northbrook S, Parekh BS. Tracking with recency assays to control the epidemic: real-time HIV surveillance and public health response. AIDS. 2019;33:1527-1529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Truong H, AM, SM, PM, AG, HA, TY, FN, GC, WKN, PD, BA, PI, AM, AG, KI, MS, KC, M. Progress in scaling up HIV recent infection surveillance in 13 countries: October 1, 2019 - June 30, 2021. Abstract presented at: AIDS 2022; 2022 Jul-Aug; Montreal, Canada. In Montreal; 2022 [cited June 25, 2025]. Available from: https://www.aids2022.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/AIDS2022_abstract_book.pdf. |

| 15. | Holmes JR, Dinh TH, Farach N, Manders EJ, Kariuki J, Rosen DH, Kim AA; PEPFAR HIV Case-Based Surveillance Study Group; PEPFAR HIV Case-based Surveillance Study Group. Status of HIV Case-Based Surveillance Implementation - 39 U.S. PEPFAR-Supported Countries, May-July 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1089-1095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Welty S, Motoku J, Muriithi C, Rice B, de Wit M, Ashanda B, Waruiru W, Mirjahangir J, Kingwara L, Bauer R, Njoroge D, Karimi J, Njoroge A, Rutherford GW. Brief Report: Recent HIV Infection Surveillance in Routine HIV Testing in Nairobi, Kenya: A Feasibility Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;84:5-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mochama G, AZ. Increasing HIV case identification from safe index testing of recent HIV acquisition: Experiences from Laikipia County, Kenya. In: IAS 2023 - The 12th IAS Conference on HIV Science [Internet]. Brisbane, 2023 [cited 2025 Jul 6]. Available from: https://www.iasociety.org/conferences/ias2023. |

| 18. | Ouk V, Soch K, Ngauv B, Samreth S, Eng B, Ly V, Yang C, Suthar A, Sulpizio CL, Ernst A, Rutherford G. HIV infection surveillance and partner testing outcomes in Cambodia from March 2020 through September 2021. In: AIDS 2022 - 24th International AIDS Conference. Montréal, Canada: IAS; 2022. Available from: https://www.aids2022.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/AIDS2022_abstract_book.pdf. |

| 19. | Lerdtriphop K, Visavakum P, Tanpradech S, Kanphukiew A, Chaiphosri P, Kittinunvorakoon C, Palakawong Na Ayuthaya T, Brukesawan C, Thanasit N, Manopaiboon C, Northbrook S. Index partner testing among recency testing clients in BMA health facilities in Bangkok, Thailand, 2020-2021. Abstract presented at: AIDS 2022; July 29, 2022-August 2, 2022; Montreal, Canada. In Montreal, Canada. Available from: https://programme.aids2022.org/Abstract/Abstract/?abstractid=3512. |

| 20. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39087] [Cited by in RCA: 48574] [Article Influence: 2111.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 21. | Bakari HM, Alo O, Mbwana MS, Salim SM, Ludeman E, Lascko T, Ramadhani HO. Same-day ART initiation, loss to follow-up and viral load suppression among people living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pan Afr Med J. 2023;46:92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Aungkulanon S, Kittinunvorakoon C, Tasaneeyapan T, Tanpradech S, Nookhai S, Pattarapayoon N, Mookleemas P, Vittangkrun A, Chaiphosri P, Naiwatanakul T, Northbrook S. Use of a robust health information system to improve accuracy of recent HIV infection testing in Bangkok, Thailand, 2020-2021. In: AIDS 2022 - 24th International AIDS Conference. Montréal, Canada: IAS; 2022. Available from: https://www.aids2022.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/AIDS2022_abstract_book.pdf. |

| 23. | Simanovong B, Southalack P, Xangsayarath P, Thongkham K, Somoulay V, Sadettanh L, Xayadeth S, Siamong C, Koummalasy K, Sulpizio CL, Monkongdee P, Tasaneeyapan T, Nookhai S, Aungkulanon S, Northbrook S. First national HIV recent infection surveillance in Lao PDR. In Montréal, Canada: AIDS 2022 - 24th International AIDS Conference; 2022. Available from: https://www.aids2022.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/AIDS2022_abstract_book.pdf. |

| 24. | Rwibasira GN, Malamba SS, Musengimana G, Nkunda RCM, Omolo J, Remera E, Masengesho V, Mbonitegeka V, Dzinamarira T, Kayirangwa E, Mugwaneza P. Recent infections among individuals with a new HIV diagnosis in Rwanda, 2018-2020. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0259708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Alemu T, Ayalew M, Haile M, Amsalu A, Ayal A, Wale F, Belay A, Desta B, Taddege T, Lankir D, Bezabih B. Recent HIV infection among newly diagnosed cases and associated factors in the Amhara regional state, Northern Ethiopia: HIV case surveillance data analysis (2019-2021). Front Public Health. 2022;10:922385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Msukwa MT, MacLachlan EW, Gugsa ST, Theu J, Namakhoma I, Bangara F, Blair CL, Payne D, Curran KG, Arons M, Namachapa K, Wadonda N, Kabaghe AN, Dobbs T, Shanmugam V, Kim E, Auld A, Babaye Y, O'Malley G, Nyirenda R, Bello G. Characterising persons diagnosed with HIV as either recent or long-term using a cross-sectional analysis of recent infection surveillance data collected in Malawi from September 2019 to March 2020. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e064707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhu Q, Wang Y, Liu J, Duan X, Chen M, Yang J, Yang T, Yang S, Guan P, Jiang Y, Duan S, Wang J, Jin C. Identifying major drivers of incident HIV infection using recent infection testing algorithms (RITAs) to precisely inform targeted prevention. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;101:131-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Herce M, Mwila C, Pry J, Moono M, Frimpong C, Kapesa H, Nanyangwe M, Phiri L, Ngandu R, Sakanya P, Mwansa S, Phiri T, Haciwa M, Maritim P, Arons M, Aholou T, Savory T, Iyer S. Integrating point-of-care recency testing into routine index testing does not increase HIV positivity among traced contacts in Lusaka, Zambia: A prospective cohort study [Conference abstract]. In Munich, Germany: AIDS 2024 - 24th International AIDS Conference; 2024.. |

| 29. | Negedu-Momoh OR, Balogun O, Dafa I, Etuk A, Oladele EA, Adedokun O, James E, Pandey SR, Khamofu H, Badru T, Robinson J, Mastro TD, Torpey K. Estimating HIV incidence in the Akwa Ibom AIDS indicator survey (AKAIS), Nigeria using the limiting antigen avidity recency assay. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24:e25669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Parmley LE, Harris TG, Hakim AJ, Musuka G, Chingombe I, Mugurungi O, Moyo B, Mapingure M, Gozhora P, Samba C, Rogers JH. Recent HIV Infection Among Men Who Have Sex with Men, Transgender Women, and Genderqueer Individuals with Newly Diagnosed HIV Infection in Zimbabwe: Results from a Respondent-Driven Sampling Survey. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2022;38:834-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Young PW, Musingila P, Kingwara L, Voetsch AC, Zielinski-Gutierrez E, Bulterys M, Kim AA, Bronson MA, Parekh BS, Dobbs T, Patel H, Reid G, Achia T, Keter A, Mwalili S, Ogollah FM, Ondondo R, Longwe H, Chege D, Bowen N, Umuro M, Ngugi C, Justman J, Cherutich P, De Cock KM. HIV Incidence, Recent HIV Infection, and Associated Factors, Kenya, 2007-2018. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2023;39:57-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ang LW, Low C, Wong CS, Boudville IC, Toh MPHS, Archuleta S, Lee VJM, Leo YS, Chow A, Lin RT. Epidemiological factors associated with recent HIV infection among newly-diagnosed cases in Singapore, 2013-2017. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Agyemang EA, Kim AA, Dobbs T, Zungu I, Payne D, Maher AD, Curran K, Kim E, Kwalira H, Limula H, Adhikari A, Welty S, Kandulu J, Nyirenda R, Auld AF, Rutherford GW, Parekh BS. Performance of a novel rapid test for recent HIV infection among newly-diagnosed pregnant adolescent girls and young women in four high-HIV-prevalence districts-Malawi, 2017-2018. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0262071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Singh B, Mthombeni J, Olorunfemi G, Goosen M, Cutler E, Julius H, Brukwe Z, Puren A. Evaluation of the accuracy of the Asanté assay as a point-of-care rapid test for HIV-1 recent infections using serum bank specimens from blood donors in South Africa, July 2018 - August 2021. S Afr Med J. 2023;113:42-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Tsepang M. Assessing the recency of HIV infections and estimating HIV incidence in two rural districts of Lesotho. [Bloemfontein]: Central University of Technology, Free State; 2022. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/11462/2585. |

| 36. | Zhou Y, Cui M, Hong Z, Huang S, Zhou S, Lyu H, Li J, Lin Y, Huang H, Tang W, Sun C, Huang W. High Genetic Diversity of HIV-1 and Active Transmission Clusters among Male-to-Male Sexual Contacts (MMSCs) in Zhuhai, China. Viruses. 2023;15:1947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Okiror PP. The role of finance and administration in supporting children living with HIV in shelter homes under the care of elderly mothers in Buikwe District in Uganda, East Africa. In Montréal, Canada: AIS2022; 2022. Available from: https://www.aids2022.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/AIDS2022_abstract_book.pdf. |

| 38. | Facente SN, Grebe E, Maher AD, Fox D, Scheer S, Mahy M, Dalal S, Lowrance D, Marsh K. Use of HIV Recency Assays for HIV Incidence Estimation and Other Surveillance Use Cases: Systematic Review. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022;8:e34410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | de Wit MM, Rice B, Risher K, Welty S, Waruiru W, Magutshwa S, Motoku J, Kwaro D, Ochieng B, Reniers G, Cowan F, Rutherford G, Hargreaves JR, Murphy G. Experiences and lessons learned from the real-world implementation of an HIV recent infection testing algorithm in three routine service-delivery settings in Kenya and Zimbabwe. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Offie DC, Akpan L, Okoh F, Femi O, Eke O, Tomori M, Ariyo AO, Omisakin C. Impacts of Recent Infection Testing Integration into HIV Surveillance in Ekiti State, South West Nigeria: A Retrospective Cross Sectional Study. World J AIDS. 2022;12:183-193. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 41. | Fieggen J, Smith E, Arora L, Segal B. The role of machine learning in HIV risk prediction. Front Reprod Health. 2022;4:1062387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Nethi AK, Karam AG, Alvarez KS, Luque AE, Nijhawan AE, Adhikari E, King HL. Using Machine Learning to Identify Patients at Risk of Acquiring HIV in an Urban Health System. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2024;97:40-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kassanjee R, Pilcher CD, Busch MP, Murphy G, Facente SN, Keating SM, Mckinney E, Marson K, Price MA, Martin JN, Little SJ, Hecht FM, Kallas EG, Welte A; Consortium for the Evaluation and Performance of HIV Incidence Assays (CEPHIA). Viral load criteria and threshold optimization to improve HIV incidence assay characteristics. AIDS. 2016;30:2361-2371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Sharma M, Ong JJ, Celum C, Terris-Prestholt F. Heterogeneity in individual preferences for HIV testing: A systematic literature review of discrete choice experiments. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29-30:100653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Thapa S, Hannes K, Cargo M, Buve A, Peters S, Dauphin S, Mathei C. Stigma reduction in relation to HIV test uptake in low- and middle-income countries: a realist review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Katz DA, Wong VJ, Medley AM, Johnson CC, Cherutich PK, Green KE, Huong P, Baggaley RC. The power of partners: positively engaging networks of people with HIV in testing, treatment and prevention. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22 Suppl 3:e25314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Dalal S, Johnson C, Fonner V, Kennedy CE, Siegfried N, Figueroa C, Baggaley R. Improving HIV test uptake and case finding with assisted partner notification services. AIDS. 2017;31:1867-1876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Mahachi N, Muchedzi A, Tafuma TA, Mawora P, Kariuki L, Semo BW, Bateganya MH, Nyagura T, Ncube G, Merrigan MB, Chabikuli ON, Mpofu M. Sustained high HIV case-finding through index testing and partner notification services: experiences from three provinces in Zimbabwe. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22 Suppl 3:e25321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Tih PM, Temgbait Chimoun F, Mboh Khan E, Nshom E, Nambu W, Shields R, Wamuti BM, Golden MR, Welty T. Assisted HIV partner notification services in resource-limited settings: experiences and achievements from Cameroon. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22 Suppl 3:e25310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/