Published online Feb 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.110880

Revised: August 26, 2025

Accepted: November 12, 2025

Published online: February 19, 2026

Processing time: 184 Days and 22.8 Hours

Depression and insomnia are highly prevalent mental disorders with a significant comorbidity rate, each exacerbating the severity and course of the other in a bidirectional relationship. Current clinical interventions, including pharmacotherapy and traditional cognitive-behavioral therapy, primarily focus on alle

To explore the effect of PERMA theory-based cognitive intervention on depressive mood, sleep quality and quality of life in patients with depression complicated with insomnia.

A total of 106 patients with depression combined with insomnia who received treatment in Ganzhou People’s Hospital from January 2022 to January 2024 were selected for the study. According to the blind selection method, 106 patients were evenly divided into the control group and the observation group. The control group received conventional cognitive intervention, and the observation group was based on the PERMA theory. After 2 months of continuous intervention in both groups, the following were assessed: depression severity (17-item Hamilton Depression Scale, Self-rating Dep

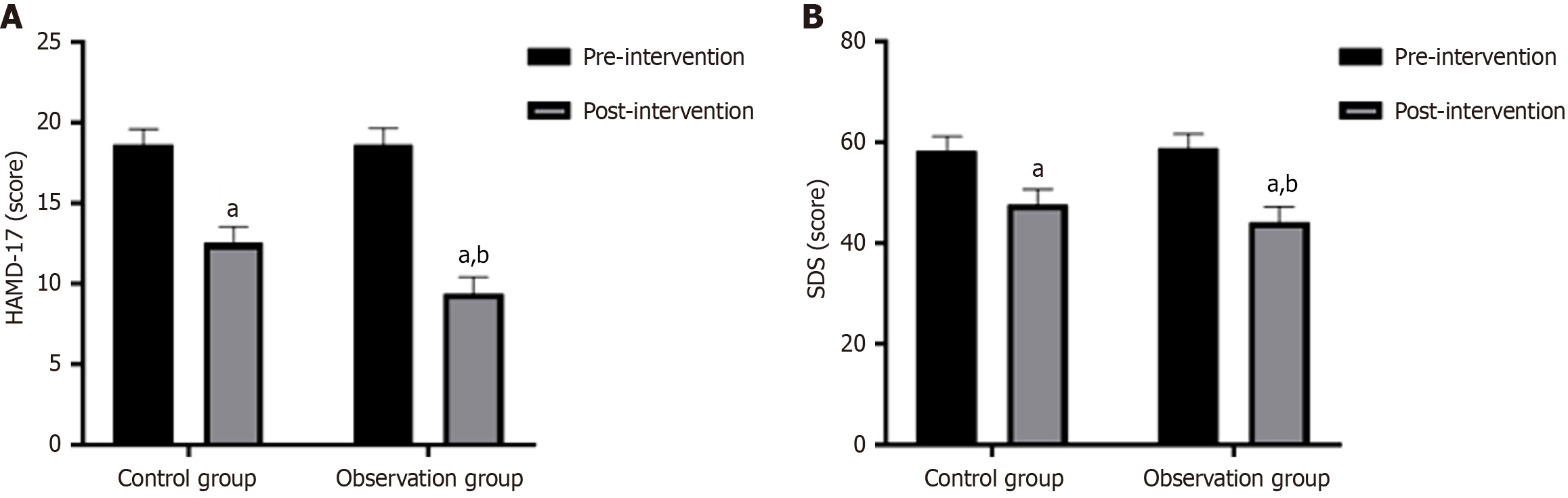

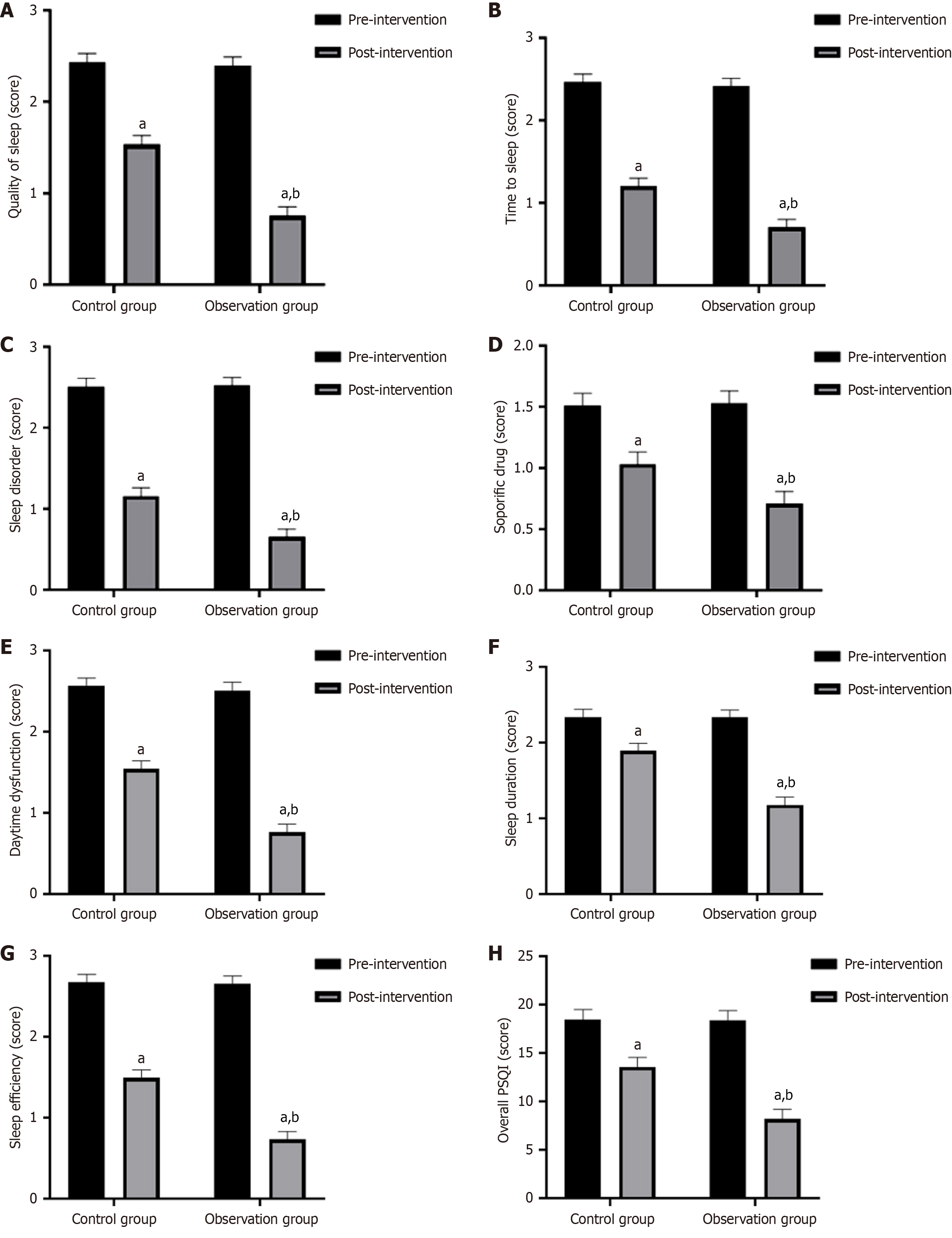

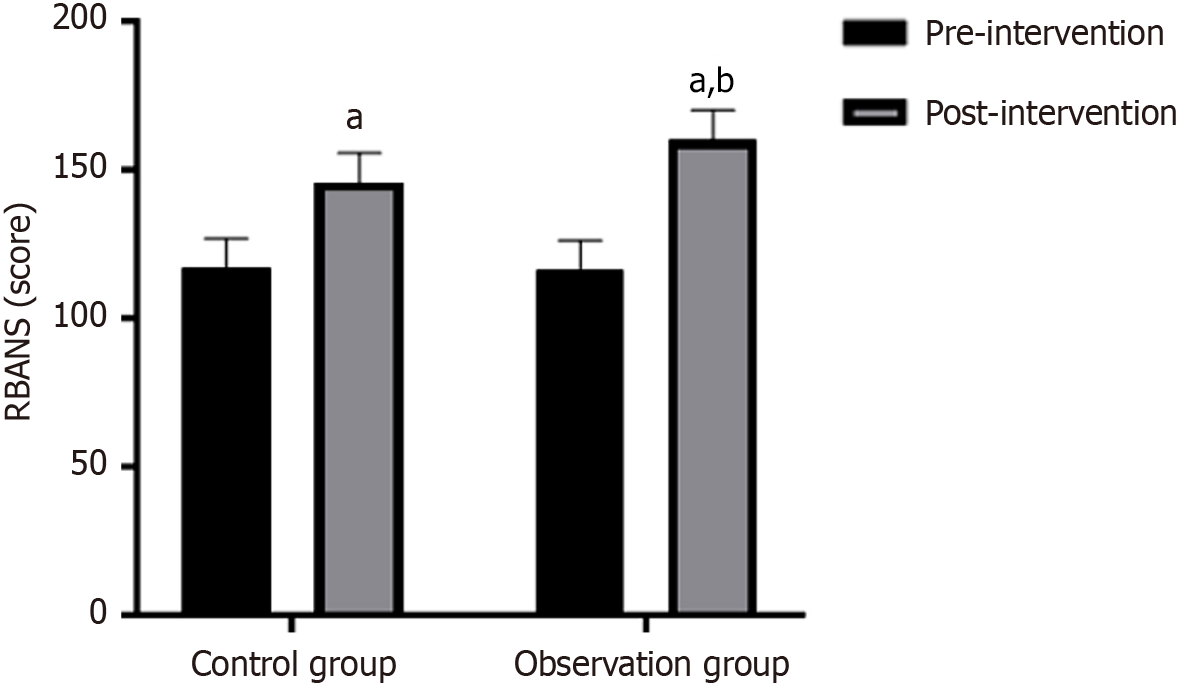

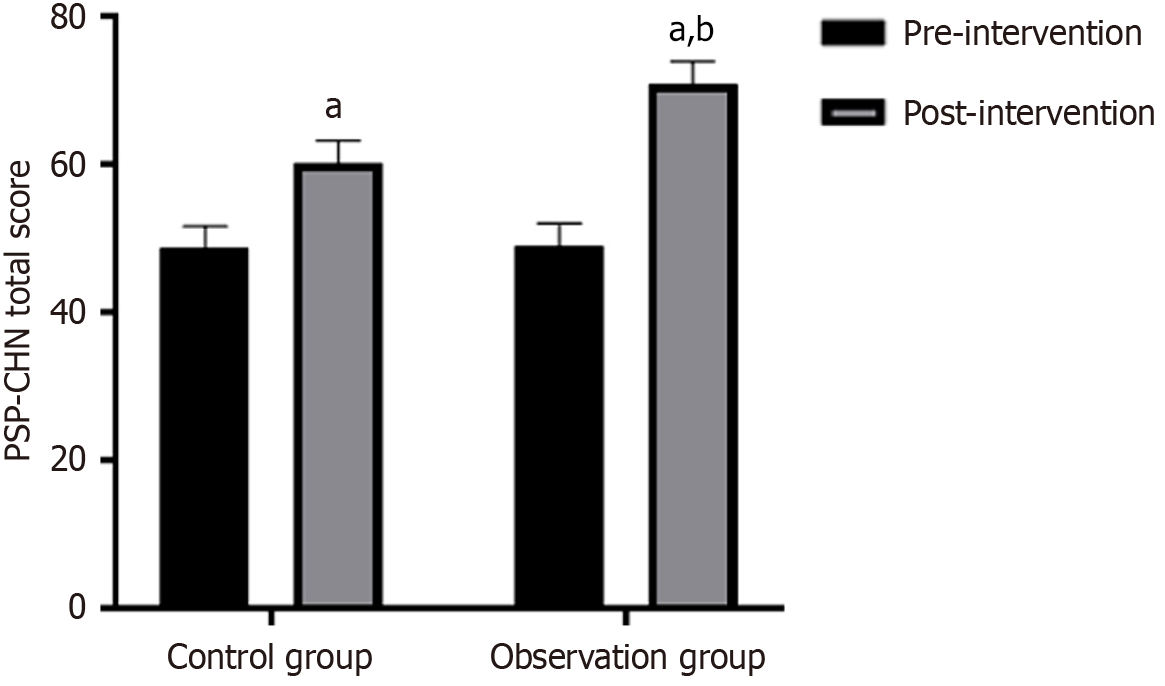

Following the intervention, the observation group demonstrated significantly reduced scores on both the 17-item Hamilton Depression Scale (9.41 ± 2.80) and Self-rating Depression Scale (44.25 ± 2.71) compared with the control group (P < 0.05). All domain scores and the total score of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index were markedly lower after treatment in the observation group than in the control group (P < 0.05). After intervention, the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status scores in the observation group (160.21 ± 15.17) were significantly higher than those in the control group (145.69 ± 12.58) (P < 0.05). After intervention, the observation group had a significantly higher total score on the Chinese version of the Personal and Social Functioning Scale (70.86 ± 6.92) compared with the control group (60.14 ± 11.52) (P < 0.05). Similarly, the observation group demon

PERMA-based cognitive intervention demonstrates superior effectiveness in patients with depression and como

Core Tip: This randomized controlled trial demonstrates that cognitive intervention based on the Positive Emotion, En

- Citation: Li SY, Rao P. Cognitive intervention based on Positive Emotion-Engagement Relationship-Meaning-Achievement theory in patients with depression and insomnia: Application value. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(2): 110880

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i2/110880.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.110880

In the past three decades, the incidence of depression in China has increased 20-30 times[1]. Despite the growing number of available mental health treatment approaches, the global incidence of depression continues to rise each year[2]. In recent years, relevant studies have found that most patients with depression have problems of interrupted sleep co

At present, the clinical treatment of depression primarily involves drug intervention and individualized cognitive-behavioral interventions[5]. Cognitive behavioral therapy, as a targeted approach, can help patients develop a more accurate understanding of the illness and its treatment by modifying maladaptive cognitions and behavioral patterns[6]. However, traditional interventions primarily address negative emotions, such as fear and distress, from a psychological perspective, while overlooking the crucial role of patients’ positive psychological resources. The Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, Achievement (PERMA) theory guides patients to focus on the beautiful aspects of life from five core aspects: Positive emotion, Engagement, Relationship, Meaning and Achievement. By applying psychological therapy methods, it further promotes the positive growth and subjective experience of patients, maximizing their inner positive potential[7], and significantly improves the insufficient exploration of psychological resources in traditional intervention. However, the application research of this model in patients with depression complicated with insomnia is still insufficient.

Therefore, this study seeks to further examine the application of PERMA theory-based cognitive intervention in patients with comorbid depression and insomnia and to evaluate its effects on reducing negative emotions and improving quality of life. The findings are presented below.

A study was conducted on 106 patients with depression and insomnia who received treatment at Ganzhou People’s Hospital from January 2022 to January 2024. This study has been approved by the in-house ethics committee.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Meets the diagnostic criteria for depression[8]; (2) Meets the diagnostic criteria for compound primary insomnia[9]; (3) Age > 18 years old and able to communicate normally; (4) No intellectual disabilities, able to complete questionnaire filling; and (5) All patients comply with the principle of informed consent and voluntarily sign the informed consent form.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Presence of other types of mental and physical illnesses; (2) Individuals with depression or anxiety symptoms caused by medication or other reasons; (3) Alcohol and drug abusers; (4) Presence of olfactory and auditory impairments; (5) Individuals who commit suicide or self-harm; and (6) History of using antidepressants or sleep-im

According to the blind selection method, the patients were evenly divided into the observation group and the control group, with 53 cases in each group. There was no significant difference in the general data between the two groups of patients (P > 0.05), which provided a basis for the research to be carried out (Table 1). Both groups of patients received routine nursing interventions, which mainly included health education, disease risk assessment, medication guidance, and daily life care.

| Intervention content | Concrete implementation process |

| Positive self-perception | Understand patients’ awareness of depression and encourage them to speak their minds |

| Use a professional perspective to clearly explain the knowledge of depression and insomnia for patients | |

| To patiently answer the doubts raised by the patient, and correct the patient’s misunderstanding of the disease | |

| Positive emotion | Psychological counselors guide patients to view the current state of the disease from a positive perspective and make them aware of the importance of positive cognition |

| Nursing staff guide patients to use positive language to motivate themselves and give timely recognition to their positive performance | |

| Recommend patients to watch movies that enhance their confidence, while also asking them to pay attention to events that cause negative emotions and list their thoughts after the event, and find ways to refute negative views | |

| Nursing staff should provide appropriate recognition and support when patients exhibit any positive emotions | |

| Input activity importance | Introduce the positive effects of “Fuliu” on patients, and guide them to actively participate in healthy entertainment activities, such as painting and listening to music, based on their condition and personal interests |

| At the same time, encourage patients to cultivate their interests and hobbies | |

| Build good relationships | By organizing role-playing activities with four different response types: Proactive, proactive, passive, and passive, we aim to enhance patients’ awareness of family, friendship, and social responsibility |

| Understand the patient’s interpersonal relationships, guide them to reflect on grateful moments in their life, motivate them to pay attention to warm moments in their daily lives, and suggest that they record them through writing a diary or sharing on social media | |

| Introduce communication skills to patients and guide them to practice actively responding to interpersonal communication | |

| Meaning of human life | Understand patients’ understanding of the meaning of life, and help them form a positive outlook on life by guiding them to delve into the deeper meaning and intrinsic value of life |

| Assist patients in discovering their inner growth significance, and based on the actual progress of their condition, jointly set practical and feasible life goals, encourage patients to look forward to the future with an optimistic attitude, and continuously strengthen their determination to recover | |

| At the same time, guide them to recognize their own value and help enhance their sense of social responsibility | |

| Achievements and goals | Based on the different stages of the patient’s condition, work together with the patient to develop detailed short-term and long-term personal development goals from two aspects: Dynamic exercise and emotional management |

| Closely track the progress of each patient’s goals and provide timely encouragement for every point of improvement | |

| Actively encourage patients to engage in activities they are good at and love |

Control group: Patients received cognitive intervention, including: (1) A comprehensive assessment of the patient’s specific condition, accompanied by correction of misconceptions regarding depression; (2) Targeted guidance delivered through group lectures, multimedia resources, video materials, and images to educate patients and their families, helping them develop a more positive attitude toward the illness; (3) Support in establishing healthy lifestyle habits, such as avoiding caffeinated beverages and vigorous exercise before bedtime, encouraging warm milk or warm-water foot soaking, and creating a quiet and comfortable sleep environment; and (4) encouraging family members to increase interaction and communication with the patient, offer them respect and understanding, and help the patient experience emotional warmth and support.

Observation group: Patients received PERMA-based cognitive intervention, including: (1) An intervention team, where the department head nurse serves as the team leader, while one attending physician, one psychological counselor, and three ward nurses form the team members. The group members jointly participate in the patient’s ward round process, and through communication and exchange with the patient, understand the patient’s actual situation and provide targeted intervention measures; (2) a personalized intervention plan for the patient; (3) Implementation of the inter

| Groups | Gender | Age, mean ± SD | Disease duration, mean ± SD | Education level | |||

| Male | Female | Primary school | Junior/senior high | College | |||

| Control group (n = 53) | 31 (58.49) | 22 (41.51) | 46.21 ± 2.96 | 4.33 ± 0.89 | 11 (20.75) | 27 (50.94) | 15 (28.31) |

| Observation group (n = 53) | 30 (56.60) | 23 (53.40) | 46.30 ± 2.94 | 4.51 ± 0.86 | 12 (22.64) | 26 (49.06) | 15 (28.30) |

| χ2/t | 0.039 | 0.157 | 1.059 | 0.062 | |||

| P value | 0.844 | 0.875 | 0.292 | 0.969 | |||

Depression level: Depression severity was assessed before and after intervention using the 17-item Hamilton depression Scale (HAMD-17)[10] and the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS)[11]. The HAMD-17 scale evaluated patients across 17 items, with a total score ranging from 0 to 52. A score less than 7 is considered normal, a score of 7 to 17 may indicate mild depression, a score of 18 to 24 may indicate moderate depression, and a score of 24 or above may indicate severe depression. The SDS scale consists of 20 items and takes 53 points as the critical value. A score of 53 or above indicates that the patient is experiencing depression. Both scales indicated that the higher the score, the more severe the depression. Among them, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the HAMD-17 scale was 0.714, and the Cronbach’s α value of the SDS scale was 0.73.

Sleep quality: The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)[12] was used to assess the sleep status of the two patient groups before and after intervention. The index consists of seven dimensions and 18 items, including sleep time, efficiency, and quality, and each item is evaluated using a four-point rating system ranging from 0 point to 3 points, with a maximum total score of 21 points. The patient’s score is inversely proportional to their sleep quality. The Cronbach’s alpha of PSQI scale is 0.791.

Cognitive function: Patients’ cognitive function before and after intervention was evaluated by the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS)[13], which contains 12 items. That is, five core levels: Attention, immediate memory, visual-spatial/structural ability, language function, and delayed memory. The total score of the scale ranges from 40 points to 160 points. A higher score indicated better cognitive function performance. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the RBANS scale was 0.90.

Social function: The social function of the two patient groups was assessed before and after intervention using the Chinese version of the Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP-CHN)[14]. This scale is an effective tool for assessing the social function of patients with mental disorders. It analyzes from four aspects: Maintenance of personal and social relationships, self-care, anti-interference ability, and aggressive behavior, comprehensively reflecting the social function status of patients. The maximum total possible score is 100 points, and the patient’s score is directly proportional to their social function status. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the PSP-CHN scale was 0.71.

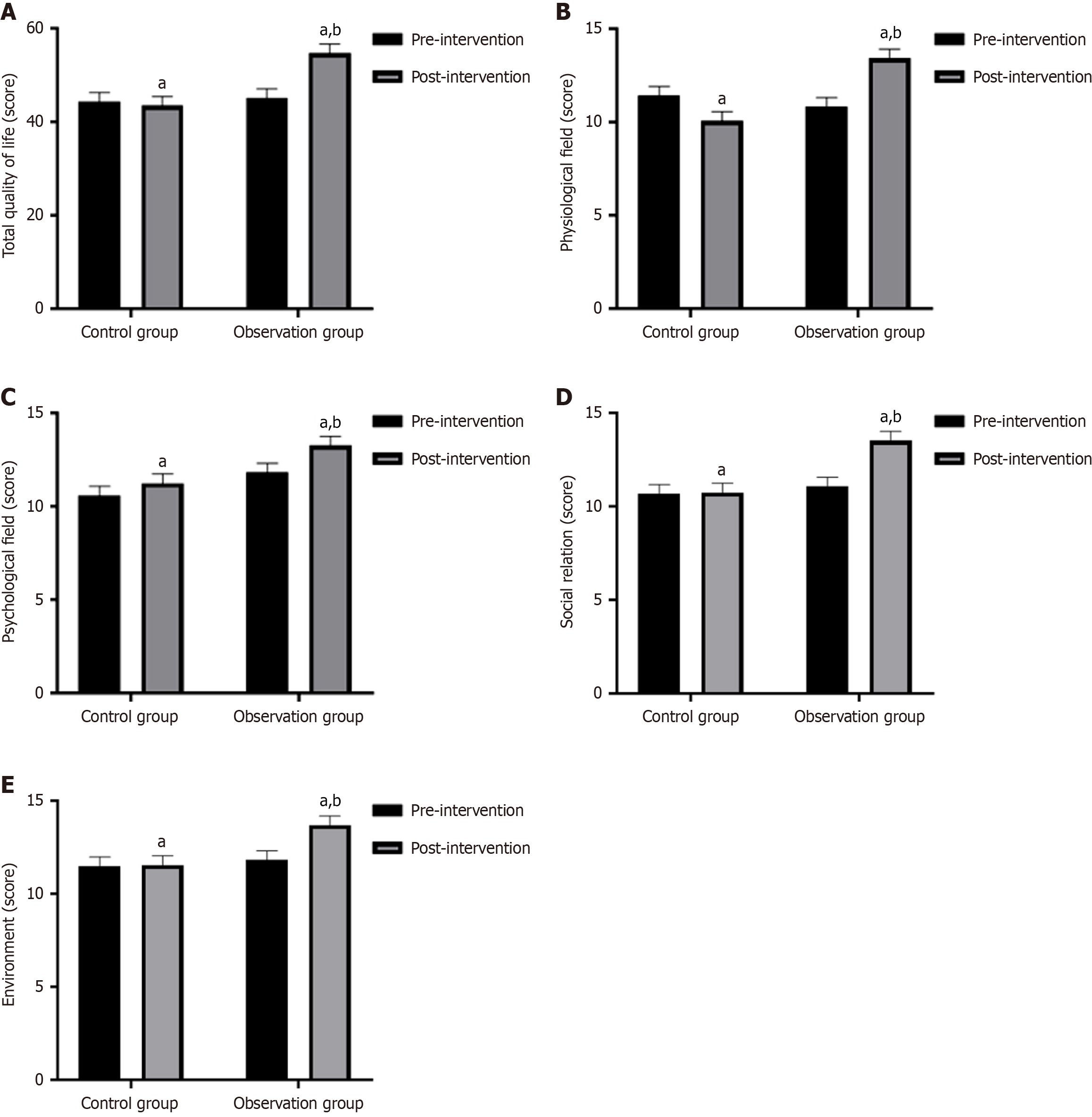

Quality of life: The World Health Organization Quality of Life BREF (WHOQOL-BREF)[15] was used to evaluate patient quality-of-life before and after intervention from four levels (24 items): Physiological field, psychological field, social, and environmental. The scale score was proportional to their quality-of-life. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of WHOQOL-BREF scale is ≥ 0.7.

All the data in this study were analyzed using SPSS 27.0, while GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 was used to generate plots. All measurement data conform to normal distribution after normality test, are expressed in the form of mean ± SD, and are compared between groups and within groups by independent t and paired t tests, respectively. All statistical data were expressed in the form of “n (%)” and compared between groups with χ2. Bilateral tests were performed on all results, and the significance of statistical results was set as P < 0.05.

In this study, the scales were guided by uniformly trained researchers to patients in the same environment to ensure the consistency of the assessment process and the repeatability of the results.

At baseline, there were no statistically significant differences in HAMD-17 or SDS scores between the two patient groups (P > 0.05). Following intervention, both patient groups showed improvement in the above scale scores. However, the observation group had significantly lower HAMD-17 and SDS scores compared to the control group (P < 0.05) (Figure 1).

Prior to the intervention, there were no significant differences in any PSQI dimension or in the total score between the two patient groups (P > 0.05). Following intervention, both groups showed a significant reduction in all assessed indicators; moreover, the total PSQI scores in the observation group were significantly lower than those in the control group (P < 0.05) (Figure 2).

There were no significant baseline differences in RBANS scores between the two groups prior to the intervention (P > 0.05). Following treatment, both groups exhibited improved RBANS performance; however, the observation group demonstrated significantly greater improvement compared to the control group (P < 0.05) (Figure 3).

At baseline, the two groups demonstrated comparable total PSP-CHN scores (P > 0.05). Post-intervention, significant improvements in PSP-CHN scores were observed in both groups; however, the observation group achieved a significantly higher total score compared to the control group (P < 0.05) (Figure 4).

Prior to the intervention, the two groups showed no statistically significant differences in any domain of the WHOQOL-BREF scale (P > 0.05). Following intervention, both groups exhibited a significant increase in WHOQOL-BREF scores; however, the observation group displayed significantly higher scores compared to the control group (P < 0.05) (Figure 5).

Insomnia and depression are the two most common mental illnesses, with prevalence rates of approximately 10%[16] and 5% to 10%[17], respectively. Meanwhile, comorbidities between insomnia and depression are very common, with approximately two-thirds of depression patients suffering from insomnia at the same time[18]. For patients with depression combined with insomnia, a single treatment for depression is usually not sufficient to reduce comorbid insomnia. At the same time, residual insomnia after depression treatment can further increase the risk of depression recurrence. Therefore, insomnia intervention is a key method for preventing disease development in patients with depression and insomnia. Multiple studies have shown that cognitive intervention has a good therapeutic effect on insomnia and can enhance patients’ self-well-being to a certain extent to treat comorbid depression[19,20]. However, patients still lack under

Recent advances in positive psychology have placed greater emphasis on enhancing patients’ subjective well-being as a core component of personalized care. The PERMA model, which outlines five fundamental elements of well-being, serves as a foundation for designing structured psychological interventions. These programs encourage patients to focus on positive aspects of life, constructively engage with their health status, gradually reframe negative thoughts, and strengthen overall happiness while coping with challenges[21]. Clinical evidence indicates that the PERMA approach relies primarily on self-management, reduces the need for intensive therapist involvement, minimizes resistance, and effectively engages both patients and their families in the therapeutic process, thereby improving acceptance and adherence[22].

This study demonstrated that following intervention, the observation group exhibited significantly lower HAMD-17 and SDS scores than the control group, suggesting that the PERMA theory-based cognitive intervention was more effective in reducing depressive symptoms compared to conventional approaches. This outcome is consistent with data reported by Yao et al[23].

The main reason for the analysis is that cognitive intervention based on PERMA theory, on the one hand, explores good emotions, cultivates gratitude and positive qualities through disease cognitive conversation and cognitive behavior intervention, enriches patients’ reflection on life, and helps to enhance their understanding of the disease. On the other hand, through peer support, communication, and role-playing, it help patients build confidence in overcoming the disease. At the same time, practicing positive language can transform patients’ negative emotions into positive emotions, promote the development of their positive qualities, and transcend ingrained patterns of thought, emotion, and behavior, instilling positive beliefs at a deeper psychological level. This process assists patients in rediscovering their identity, transforming maladaptive emotions and cognitions, strengthening their confidence in disease management, and faci

Secondly, results from this study showed that the observation group achieved significantly higher RBANS scores post-intervention than the control group, suggesting that the PERMA-based cognitive intervention is more effective at en

In summary, PERMA theory-based cognitive intervention has a more significant effect on patients with depression and insomnia. It can effectively alleviate patients’ depressive emotions, improve their sleep quality, enhance their cognitive and social functions, and improve their quality of life. It is worth promoting and applying in clinical practice. However, this study also has certain shortcomings: (1) The limited sample size may reduce the generalizability of the findings; (2) The observation indicators in this study were evaluated using scales, and the scoring results may be influenced by subjective factors of the patients; (3) This study has not yet conducted follow-up work on patients after intervention and cannot clarify the long-term effects of cognitive intervention based on PERMA theory on patients; and (4) This study only explored the application effect of nursing intervention mode in patients with depression and insomnia and has not yet explored the specific mechanism of action. Therefore, future studies should incorporate multi-center designs with larger sample sizes and multiple assessment indicators, complemented by long-term follow-up, to enhance the reliability and validity of the finding. Meanwhile, further analysis of the possible mechanisms of action will be conducted through basic experiments to ensure the scientific validity of the research results.

The authors would like to thank all the patients who participated in this study. We also extend our gratitude to the medical staff of the Department of Psychiatry at Ganzhou People’s Hospital for their support and assistance throughout the intervention and data collection process.

| 1. | Lu J, Xu X, Huang Y, Li T, Ma C, Xu G, Yin H, Xu X, Ma Y, Wang L, Huang Z, Yan Y, Wang B, Xiao S, Zhou L, Li L, Zhang Y, Chen H, Zhang T, Yan J, Ding H, Yu Y, Kou C, Shen Z, Jiang L, Wang Z, Sun X, Xu Y, He Y, Guo W, Jiang L, Li S, Pan W, Wu Y, Li G, Jia F, Shi J, Shen Z, Zhang N. Prevalence of depressive disorders and treatment in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:981-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 477] [Cited by in RCA: 529] [Article Influence: 105.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9:137-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 436] [Cited by in RCA: 3516] [Article Influence: 879.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Blanken TF, Borsboom D, Penninx BW, Van Someren EJ. Network outcome analysis identifies difficulty initiating sleep as a primary target for prevention of depression: a 6-year prospective study. Sleep. 2020;43:zsz288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Raman S, Hyland P, Coogan AN. Temporal associations between insomnia and depression symptoms in adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-lagged path modelling analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022;312:114533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Blom K, Forsell E, Hellberg M, Svanborg C, Jernelöv S, Kaldo V. Psychological Treatment of Comorbid Insomnia and Depression: A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2024;93:100-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sampogna G, Toni C, Catapano P, Rocca BD, Di Vincenzo M, Luciano M, Fiorillo A. New trends in personalized treatment of depression. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2024;37:3-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nie YZ, Zhang X, Hong NW, Zhou C, Huang QQ, Cao SY, Wang C. Psychometric validation of the PERMA-profiler for well-being in Chinese adults. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2024;246:104248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Choi KW, Kim YK, Jeon HJ. Comorbid Anxiety and Depression: Clinical and Conceptual Consideration and Transdiagnostic Treatment. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1191:219-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Benca RM, Buysse DJ. Assessing and Treating Insomnia in Patients With Psychiatric Disorders, Part 2. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79:ME17008PD3C. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wagner S, Helmreich I, Lieb K, Tadić A. Standardized rater training for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD₁₇) and the Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (IDS(C30)). Psychopathology. 2011;44:68-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chagas MH, Tumas V, Loureiro SR, Hallak JE, Trzesniak C, de Sousa JP, Rodrigues GG, Santos Filho A, Crippa JA. Validity of a Brazilian version of the Zung self-rating depression scale for screening of depression in patients with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16:42-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Popević MB, Milovanović APS, Milovanović S, Nagorni-Obradović L, Nešić D, Velaga M. Reliability and Validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index-Serbian Translation. Eval Health Prof. 2018;41:67-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wilk CM, Gold JM, Bartko JJ, Dickerson F, Fenton WS, Knable M, Randolph C, Buchanan RW. Test-retest stability of the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:838-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tianmei S, Liang S, Yun'ai S, Chenghua T, Jun Y, Jia C, Xueni L, Qi L, Yantao M, Weihua Z, Hongyan Z. The Chinese version of the Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP): validity and reliability. Psychiatry Res. 2011;185:275-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dalky HF, Meininger JC, Al-Ali NM. The Reliability and Validity of the Arabic World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF Instrument Among Family Caregivers of Relatives With Psychiatric Illnesses in Jordan. J Nurs Res. 2017;25:224-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Baglioni C, Altena E, Bjorvatn B, Blom K, Bothelius K, Devoto A, Espie CA, Frase L, Gavriloff D, Tuuliki H, Hoflehner A, Högl B, Holzinger B, Järnefelt H, Jernelöv S, Johann AF, Lombardo C, Nissen C, Palagini L, Peeters G, Perlis ML, Posner D, Schlarb A, Spiegelhalder K, Wichniak A, Riemann D. The European Academy for Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Insomnia: An initiative of the European Insomnia Network to promote implementation and dissemination of treatment. J Sleep Res. 2020;29:e12967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yang CH, Lv JJ, Kong XM, Chu F, Li ZB, Lu W, Li XY. Global, regional and national burdens of depression in adolescents and young adults aged 10-24 years, from 1990 to 2019: findings from the 2019 Global Burden of Disease study. Br J Psychiatry. 2024;225:311-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Vargas I, Perlis ML. Insomnia and depression: clinical associations and possible mechanistic links. Curr Opin Psychol. 2020;34:95-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hertenstein E, Trinca E, Wunderlin M, Schneider CL, Züst MA, Fehér KD, Su T, Straten AV, Berger T, Baglioni C, Johann A, Spiegelhalder K, Riemann D, Feige B, Nissen C. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in patients with mental disorders and comorbid insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2022;62:101597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 55.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Lin W, Li N, Yang L, Zhang Y. The efficacy of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PeerJ. 2023;11:e16137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Heshmati S, Kibrislioglu Uysal N, Kim SH, Oravecz Z, Donaldson SI. Momentary PERMA: An Adapted Measurement Tool for Studying Well-Being in Daily Life. J Happiness Stud. 2023;24:2441-2472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wang D, Li B, Xin H, Wu X, Xia J. A study of a PERMA-based positive psychological intervention programme in subthreshold depressed patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer: formulation and application. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1437025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yao Y, Wang CJ, Yin SY, Xu GZ, Cheng YF, Huang QQ, Jin Y. Effects of positive psychology intervention based on the PERMA model on psychological status and quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease. Heliyon. 2024;10:e36902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shan J, Qi X. Effects of Music Therapy in the Context of Positive Emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning and Accomplishment (PERMA) on Negative Emotions in Patients with Mild-to-Moderate Depression. Noise Health. 2024;26:363-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dong L, Xie Y, Zou X. Association between sleep duration and depression in US adults: A cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord. 2022;296:183-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 54.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sokołowski A, Morawetz C, Folkierska-Żukowska M, Łukasz Dragan W. Brain activation during cognitive reappraisal depending on regulation goals and stimulus valence. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2022;17:559-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | de Kloet ER. Brain mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptor balance in neuroendocrine regulation and stress-related psychiatric etiopathologies. Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res. 2022;24:100352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/