Published online Feb 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.111012

Revised: September 12, 2025

Accepted: November 11, 2025

Published online: February 19, 2026

Processing time: 181 Days and 23.5 Hours

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by pronounced behavioral heterogeneity and individual variability. Growing evidence indicates a strong association between gut microbiota and ASD; how

To investigate the effects of the gut microbiome in MZs with ASD using 16S ribo

Participants were recruited from the Chinese MZs with autism spectrum disorder (MZCo-ASD) cohort and stratified into mild MZCo-ASD and severe MZCo-ASD (MZCo-ASD-H) groups based on their Childhood Autism Rating Scale scores. Fecal samples were collected and analyzed using 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing.

Although overall microbial diversity did not differ significantly between the groups, gut microbiota composition was notably altered. At the genus level, Por

Despite similar overall diversity, children with severe ASD exhibited distinct gut microbiota structures and fun

Core Tip: Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a highly heritable and heterogeneous neurodevelopmental disorder. Diagnostic and treatment options remain limited. Researchers are increasingly investigating the relationship between gut dysbiosis and ASD. This study examined gut microbiota composition and functions in monozygotic twins with varying ASD severity levels. Enrichment of Porphyromonas and reduced expression of genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism and stress responses were observed, suggesting a correlation between gut microbial dysbiosis and ASD severity.

- Citation: Huang YY, Li CY, Li Y, Fang H, Ke XY. Characteristics and functions of the gut microbiome in monozygotic twins with autism spectrum disorders of varying severity. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(2): 111012

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i2/111012.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.111012

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a highly heritable and heterogeneous neurodevelopmental disorder, primarily characterized by impairments in social interaction and communication, as well as restricted or repetitive behaviors, interests, or activities[1-3]. Some individuals with ASD also experience gastrointestinal, immune, and sleep disorders, suggesting systemic dysregulation. Currently, diagnostic and treatment options remain limited[2]. A comprehensive understanding of the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms and heterogeneity of ASD will facilitate the de

Several clinical studies have indicated significant differences in the gut microbiota of individuals with ASD compared to healthy controls[5-7]. Specifically, individuals with ASD exhibit a decreased abundance of beneficial bacteria and an increased abundance of harmful bacteria in their intestines. This dysbiosis may substantially influence neurodevelopment and behavioral performance through modulation of the gut-brain axis[8,9]. For example, the metabolic products of the gut microbiota, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), can influence neurodevelopment and immune responses[6,10,11]. Dysbiosis may also increase intestinal permeability, allowing endogenous or exogenous neurotoxins to enter the central nervous system, thereby exacerbating ASD pathology[8]. Several studies have systematically examined the gut mic

In studies of monozygotic twins (MZs), gut microbiota dysbiosis-shaped by both shared factors (e.g., the intrauterine environment, postnatal upbringing) and nonshared factors (e.g., individual experiences, health status, dietary habits, and antibiotic exposure) - has been associated with heterogeneous phenotypic expressions of ASD among genetically identical individuals[19,20]. The expression of comorbid conditions in MZs may be influenced by both shared environmental and genetic factors[21,22]. However, previous studies have reported a broad spectrum of diagnostic concordance for ASD in MZs, with rates ranging from 36% to 96%. These variations are influenced not only by gender but also by heterogeneous environmental factors[23-25]. Overall, these findings suggest that gut microbiota dysbiosis likely interacts in complex ways with the severity of ASD.

In this study, we examined the composition and functional profiles of the gut microbiota in individuals with ASD across different severity levels in MZs. We further explored the role of gut microbiota as an environmental factor in shaping variations in ASD severity during early development, providing insights into potential avenues for prevention and management.

We recruited 20 pairs of MZs aged 2-6 years, with at least one twin diagnosed with ASD. The diagnosis was made by two senior psychiatrists (at least associate professor level) in accordance with the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Participants were included if: (1) At least one twin in the pair was diagnosed with ASD; (2) Both twins were aged between 2 and 6 years; (3) Monozygosity was confirmed by deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) analysis of blood samples; and (4) Parents or legal guardians provided written informed consent for their children’s participation.

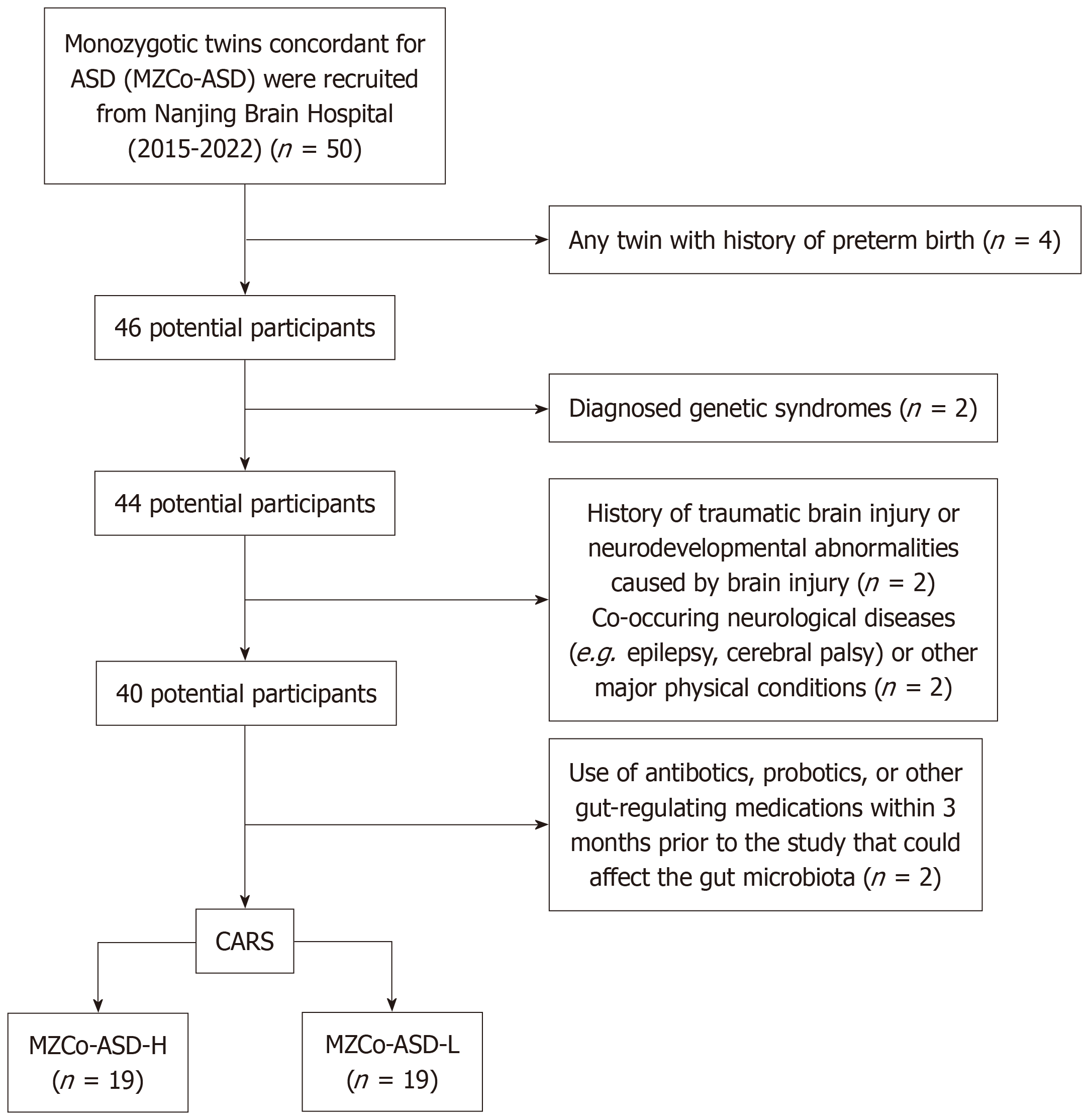

Participants were excluded if either twin had: (1) A history of preterm birth (gestational age < 37 weeks); (2) A diagnosed genetic syndrome (e.g., Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome); (3) A history of traumatic brain injury or neurodevelopmental abnormalities caused by brain injury; (4) Co-occurring neurological diseases (e.g., epilepsy, cerebral palsy) or other major physical conditions (e.g., severe cardiovascular or metabolic diseases); or (5) Used antibiotics, probiotics, or other gut-regulating medications within the 3 months prior to enrollment, as these could affect the gut microbiota.

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Nanjing Brain Hospital, affiliated with Nanjing Medical University (approval No. 2017-KY021), and was conducted in strict adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant ethical standards. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants’ guardians before the study commenced.

The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS)[13] was used to assess ASD symptom severity. CARS is a widely used tool that measures multiple dimensions, including social interaction, communication, and repetitive behaviors. It consists of 15 items, each rated on a 1-4 scale, with total scores ranging from 15 to 60; higher scores indicate greater ASD symptom severity. The scale has shown high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.94) and good test-retest reliability (r = 0.88) across studies[16]. The Chinese version has also shown good reliability and validity[17]. For this study, twins were grouped by clinical severity: The twin with the higher CARS score was designated the “H” twin, and the twin with the lower score was designated the “L” twin. Accordingly, the severe MZs with ASD (MZCo-ASD-H) group consisted of H twins, and the MZs with ASD-mild (MZCo-ASD-L) group consisted of L twins (Figure 1).

The Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R)[18] was also administered to assess core ASD features. The ADI-R is a standardized tool involving semi-structured caregiver interviews conducted by trained assessors. It assesses three domains - social interaction impairments, communication deficits, and repetitive stereotyped behaviors - across 93 items. Scoring reflects the individual’s typical behavior at ages 4-5 years, with higher scores indicating greater impairments in each dimension. The ADI-R has shown high internal consistency (α = 0.92) and excellent test-retest reliability (r = 0.94)[19]. It is widely used in clinical assessments and research on ASD.

Fecal sample collection: Fecal samples were collected from all 20 twin pairs during the recruitment phase. Participants were instructed to collect approximately 1 g of fresh feces using a sterile cotton swab within 5 minutes of defecation. Samples were immediately placed in microbial DNA preservation solution, delivered to the clinical assistant within 24 hours, and stored at -80 °C until further processing.

DNA extraction and quality control: Total bacterial DNA was extracted from the fecal samples using the sodium dodecyl sulfate lysis buffer freeze-thaw method. DNA integrity was confirmed using agarose gel electrophoresis, ensuring a distinct band of approximately 15 kb. DNA quality was assessed using a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer. Samples were considered suitable for downstream analysis if they met the following criteria: Concentration ≥ 20 ng/μL; total amount ≥ 500 ng; optical density260/optical density280 ratio of 1.8-2.0.

The V4 region of the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) gene was amplified using the forward primer 515F (5’-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3’) and the reverse primer 806R (5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’). Primers were diluted to 1 μM, and genomic DNA was diluted to 5 ng/μL. Each 50 μL polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reaction contained 25 μL of high-fidelity enzyme (Phusion high-fidelity PCR Master Mix with high-fidelity Buffer), 3 μL of each forward and reverse primer (10 μM), 10 μL of DNA template, and 6 μL of double distilled water. The amplification conditions were as follows: An initial denaturation at 98 °C for 30 seconds; 30 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 15 seconds, annealing at 58 °C for 15 seconds, and extension at 72 °C for 15 seconds; a final extension at 72 °C for 1 minute; and a hold at 4 °C. The PCR products were purified and quantified using AMPure XP beads and the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit. The purified V4 Library was sequenced on the Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform.

Raw sequencing data were demultiplexed for each sample. Barcodes and primer sequences were removed, and paired-end reads were merged using Vsearch v2.4.4 to obtain raw tag data. Strict quality control and filtering were applied to ensure the production of high-quality sequences. Low-quality sequences were filtered out based on the following criteria: Sequence length < 150 bp, average quality score < 20, and the presence of ambiguous bases. Additionally, mononucleotide repeat sequences and chimeric sequences were removed to obtain the final valid data.

Operational taxonomic unit (OTU) analysis was performed using Vsearch software, with sequences sharing > 97% similarity grouped into a single OTU. Duplicate sequences were removed, clustering and chimera checking were conducted, and representative sequences were selected using the default parameters. OTUs were taxonomically annotated against the SILVA128 database. An OTU list was generated, and the community composition was assessed across taxonomic levels, from kingdom to species. OTUs representing < 0.001% of total sequences across all samples were excluded.

Sequence data were analyzed primarily using QIIME2 and R (v3.2.0). QIIME2 software was used to compute OTU levels, alpha diversity indices (Chao1, abundance-based coverage estimator, Shannon, and Simpson indices), and inter-group differences in these indices, which reflect OTU richness and evenness across samples. Beta diversity was analyzed using QIIME2 by calculating UniFrac distance metrics and visualizing the microbial community structure through principal component analysis, principal coordinate analysis, and non-metric multidimensional scaling plots. Differences in UniFrac distances between groups were evaluated using the t-test and a Monte Carlo permutation test, and the results were illustrated using boxplots. Shared and unique OTUs between samples or groups were visualized using Venn diagrams generated with the R package “VennDiagram”. The Kruskal-Wallis method in the R stats package was used to compare differences at various taxonomic levels (phylum, class, order, family, genus).

Linear discriminant analysis Effect Size (LEfSe), developed by professor Curtis Huttenhower at Harvard University in 2011, was applied to identify biomarkers with significant differential abundance between groups. LEfSe first employs nonparametric (Kruskal-Wallis) and rank-based tests to identify significant differences in abundance between groups and then applies linear discriminant analysis (LDA) to estimate the influence of species abundance on group separation. LEfSe software uses the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum test to detect biomarkers that differ significantly between two or more groups. Functional prediction based on 16S rRNA/internal transcribed spacer sequencing was performed using Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States, enabling the prediction of microbial functions.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0. continuous variables with a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± SD and compared between two groups using the t-test. Non-normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as median (interquartile range) [median (25th percentile, 75th percentile)] and compared between groups using the rank-sum test. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

This study included 38 participants, comprising 19 pairs of MZs with ASD. One pair was excluded because of the poor-quality fecal sample. None of the participants had used antibiotics or other medications that could influence gut microbiota within the 3 months before sample collection, thereby minimizing potential external confounding factors. Based on CARS scores, the twins were divided into two subgroups: The MZCo-ASD-H group (high-severity; n = 19) with higher CARS scores, and the MZCo-ASD-L group (low severity; n = 19), with lower CARS scores. Overall, 73.7% were male (n = 28) and 26.3% were female (n = 10). Ages ranged from 24 months to 69 months, with a mean age of 47.47 ± 13.73 months. No significant differences were observed between the two groups regarding age or sex distribution. Scores on the Autism Diagnostic Interview (ADI) were as follows: ADI-A (language/communication), 15.50 ± 5.47; ADI-B (social interaction), 11.03 ± 4.80; ADI-C (repetitive behaviors), 4.05 ± 2.45; and total CARS score, 34.00 ± 3.80 (Table 1). These results confirmed differences in ASD symptom severity between the groups, consistent with our aim of grouping by behavioral characteristics in MZs. Notably, the MZCo-ASD-H group exhibited significantly higher CARS scores and greater impairments in social interaction and stereotyped behaviors compared with the MZCo-ASD-L group (Table 2).

| Group | Sample | Sex | Age (month age) | Diagnosis | Antibiotic use in the past three months | ADI-A | ADI-B | ADI-C | CARS |

| MZCo-ASD-H | 1 | Male | 69.00 | ASD | None | 20 | 12 | 4 | 36 |

| 2 | Female | 64.00 | ASD | None | 19 | 18 | 4 | 33 | |

| 3 | Male | 60.00 | ASD | None | 9 | 8 | 3 | 32 | |

| 4 | Male | 42.00 | ASD | None | 18 | 22 | 6 | 34 | |

| 5 | Male | 62.00 | ASD | None | 22 | 16 | 9 | 39 | |

| 6 | Male | 63.00 | ASD | None | 12 | 18 | 9 | 38 | |

| 7 | Male | 36.00 | ASD | None | 23 | 11 | 5 | 35 | |

| 8 | Male | 56.00 | ASD | None | 20 | 13 | 5 | 39 | |

| 9 | Male | 42.00 | ASD | None | 20 | 7 | 8 | 35 | |

| 10 | Male | 56.00 | ASD | None | 18 | 12 | 2 | 34 | |

| 11 | Female | 32.00 | ASD | None | 24 | 14 | 3 | 42 | |

| 12 | Male | 24.00 | ASD | None | 16 | 13 | 6 | 35 | |

| 13 | Female | 64.00 | ASD | None | 12 | 2 | 2 | 34 | |

| 14 | Male | 43.00 | ASD | None | 20 | 10 | 3 | 36 | |

| 15 | Female | 41.00 | ASD | None | 11 | 5 | 4 | 33 | |

| 16 | Male | 42.00 | ASD | None | 14 | 9 | 7 | 34 | |

| 17 | Male | 41.00 | ASD | None | 16 | 16 | 6 | 30 | |

| 18 | Male | 28.00 | ASD | None | 23 | 14 | 6 | 45 | |

| 19 | Female | 35.00 | ASD | None | 20 | 14 | 3 | 38 | |

| MZCo-ASD-L | 1 | Male | 69.00 | ASD | None | 20 | 11 | 3 | 33 |

| 2 | Female | 68.00 | ASD | None | 17 | 16 | 9 | 31 | |

| 3 | Male | 60.00 | ASD | None | 7 | 2 | 3 | 31 | |

| 4 | Male | 42.00 | ASD | None | 13 | 16 | 2 | 31 | |

| 5 | Male | 62.00 | ASD | None | 16 | 14 | 8 | 33 | |

| 6 | Male | 63.00 | ASD | None | 6 | 11 | 5 | 30 | |

| 7 | Male | 36.00 | ASD | None | 22 | 11 | 4 | 33 | |

| 8 | Male | 56.00 | ASD | None | 15 | 8 | 3 | 33 | |

| 9 | Male | 42.00 | ASD | None | 13 | 6 | 2 | 32 | |

| 10 | Male | 56.00 | ASD | None | 0 | 1 | 0 | 30 | |

| 11 | Female | 32.00 | ASD | None | 20 | 12 | 2 | 34 | |

| 12 | Male | 24.00 | ASD | None | 17 | 11 | 4 | 33 | |

| 13 | Female | 64.00 | ASD | None | 12 | 2 | 2 | 31 | |

| 14 | Male | 43.00 | ASD | None | 8 | 8 | 0 | 30 | |

| 15 | Female | 41.00 | ASD | None | 6 | 9 | 2 | 30 | |

| 16 | Male | 42.00 | ASD | None | 14 | 9 | 4 | 31 | |

| 17 | Male | 41.00 | ASD | None | 15 | 16 | 2 | 28 | |

| 18 | Male | 28.00 | ASD | None | 15 | 12 | 4 | 43 | |

| 19 | Female | 35.00 | ASD | None | 16 | 10 | 0 | 33 | |

| Total, mean ± SD | 38 | 28/10 | 47.47 ± 13.73 | ASD | None | 15.50 ± 5.47 | 11.0 ± 4.80 | 4.05 ± 2.45 | 34.00 ± 3.80 |

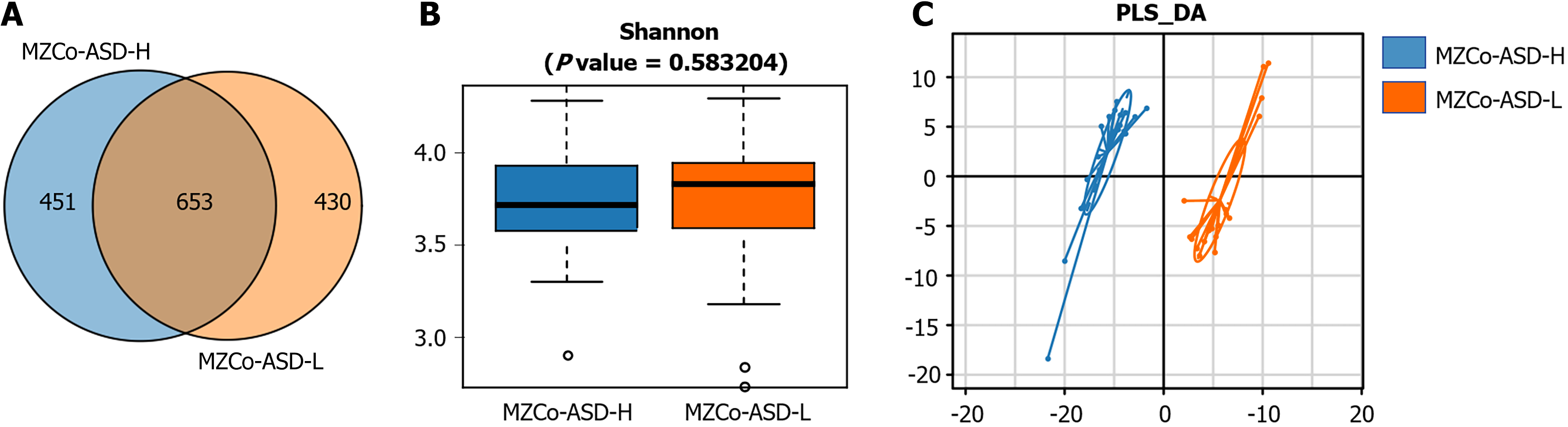

Species composition analysis of the MZCo-ASD-H and MZCo-ASD-L groups OTU clustering analysis was conducted using 16S rRNA sequencing data from all fecal samples. At a sequence similarity threshold of 97%, 1534 valid OTUs were identified, representing the overall gut microbiota composition of the participants. To investigate differences in microbial composition associated with ASD severity, OTU distribution was compared between the MZCo-ASD-H and MZCo-ASD-L groups. As shown in Figure 2A, the MZCo-ASD-H group comprised 1104 OTUs, whereas the MZCo-ASD-L group comprised 1083 OTUs. The two groups shared 653 OTUs, with 451 unique to the MZCo-ASD-H group and 430 unique to the MZCo-ASD-L group. Although many OTUs were shared - indicating high similarity in microbial composition - each group also harbored distinct OTUs. These group-specific microbial features suggest that variations in the abundance of specific bacterial taxa may be linked to ASD symptom severity, even with a shared genetic background. The Shannon index measures both species richness and evenness within a community, serving as a key indicator of microbial community complexity. In this study, it was used to assess species diversity in the gut microecosystem of twins with varying ASD severity by analyzing α diversity in the MZCo-ASD-H and MZCo-ASD-L groups. As shown in Figure 2B, the distribution of Shannon index values was similar between the two groups, with a median of approximately 3.75 in both groups. The nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test revealed no significant differences, indicating comparable α diversity of gut microbiota across groups. To further investigate structural differences in microbial composition, partial least squares discriminant analysis was used to visualize β diversity. Figure 2C shows the two-dimensional distribution of samples within the partial least squares discriminant analysis model. Although explanatory rates were relatively low, a clear separation trend was observed between the MZCo-ASD-H and MZCo-ASD-L groups, suggesting differences in overall gut microbiota composition. These findings indicate that, despite shared genetic backgrounds, variations in ASD severity may be associated with structural changes in gut microecology. Such differences provide a basis for identifying key differential genera in future analyses.

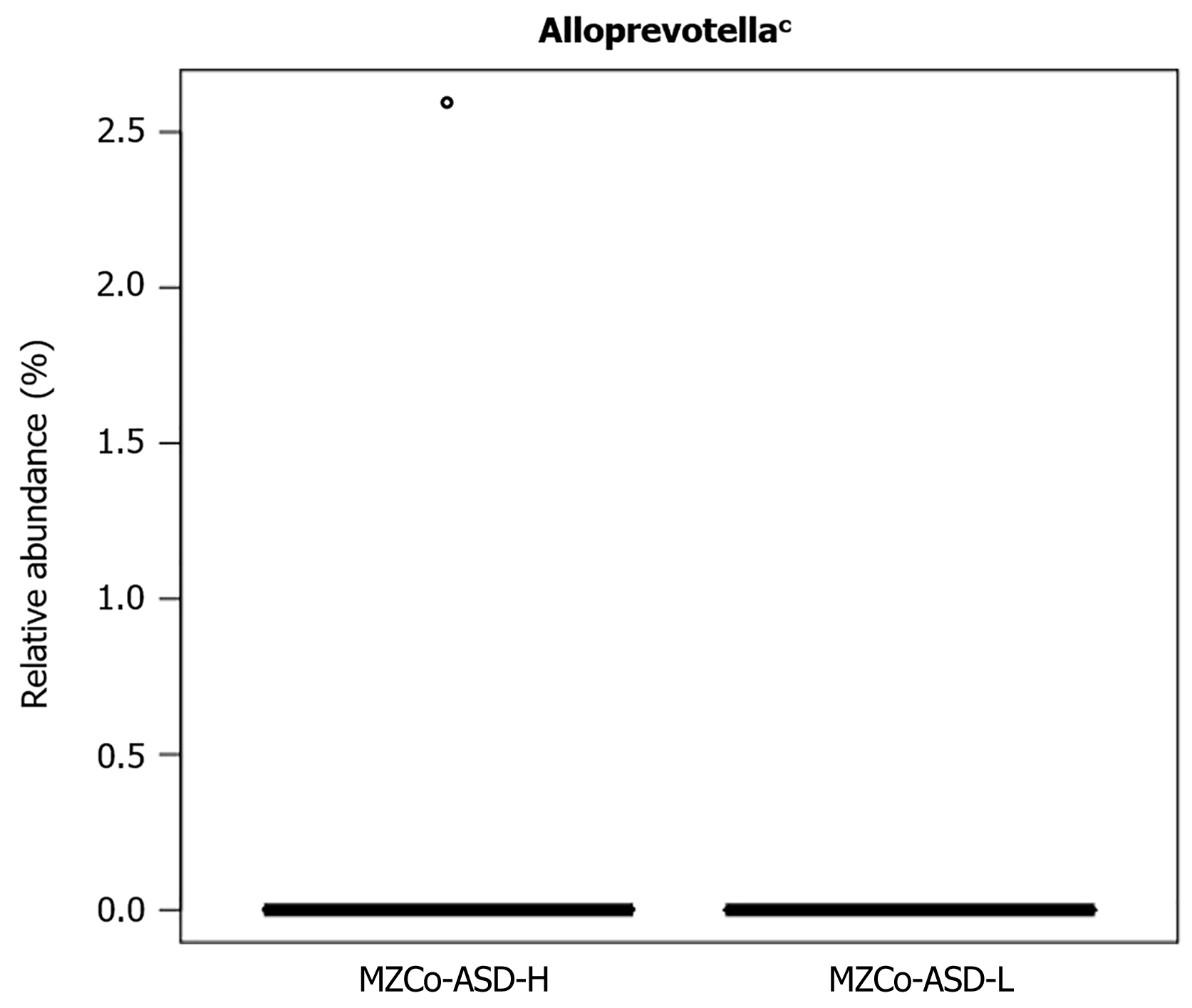

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to evaluate differences in relative abundance between groups. To adjust for multiple comparisons, we applied the false discovery rate (FDR) correction to compute q-values, providing more stringent control of false positives. Only the genus Alloprevotella exhibited a statistically significant difference between the groups (Table 3, Figure 3), suggesting a potential association with ASD symptom severity. Belonging to the phylum Bacteroidota, Alloprevotella has been implicated in host immune regulation, mucosal barrier function, and metabolic processes. These findings support further investigation of its role in ASD.

| Gut microbiota | MZCo-ASD-H | MZCo-ASD-L | P value | q value |

| Alloprevotella | 0.001366 ± 0.000035 | 0 ± 0 | 0.000999 | 0.019 |

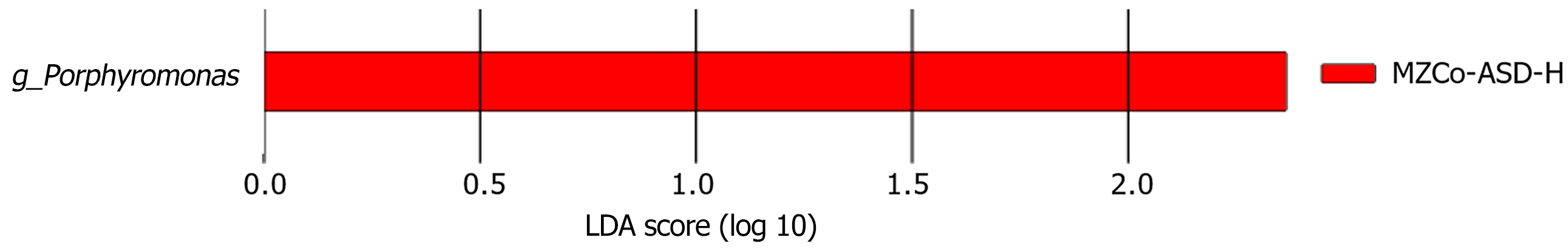

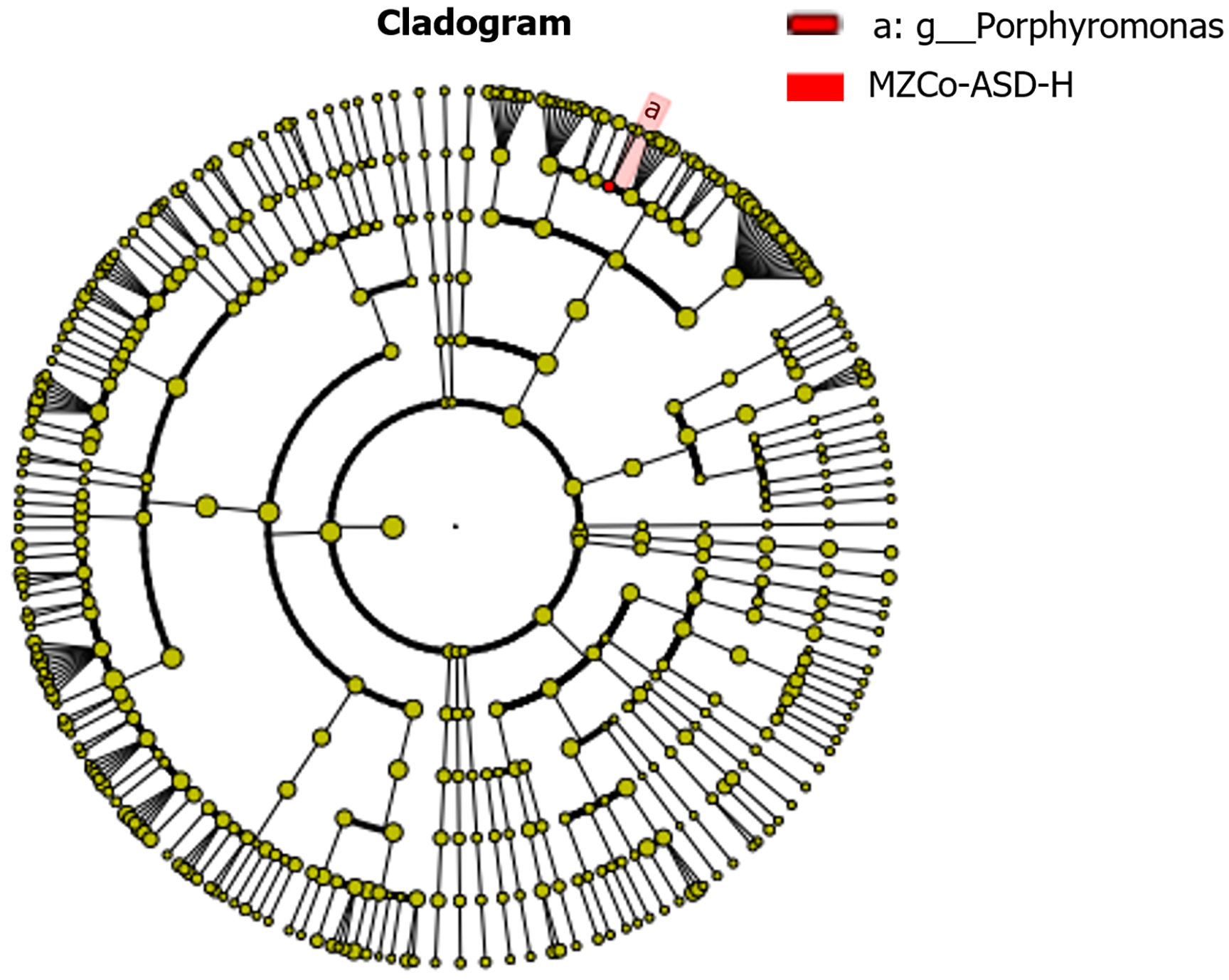

LEfSe was applied to identify key gut microbes with differential abundance across ASD severity levels. This approach integrates LDA scoring with statistical testing and classification-specific phylogenetic screening, focusing on “representative discriminatory taxa” rather than global statistical significance after FDR correction. As shown in Figure 4, only the MZCo-ASD-H group demonstrated statistically significant enrichment of the genus Porphyromonas, indicating a higher abundance compared with the MZCo-ASD-L group. Although Porphyromonas did not achieve FDR-adjusted significance in the Wilcoxon test, it exhibited strong discriminatory power between the groups and consistent phy

Further analysis showed that the MZCo-ASD-H group was significantly enriched in Porphyromonas and its higher-level taxa, including phylum (Bacteroidetes), class (Bacteroidia), order (Bacteroidales), and family (Porphyromonadaceae). These findings suggest consistent accumulation of Porphyromonas across multiple taxonomic levels, implying that this genus may contribute to shaping the gut microbiome of individuals with severe ASD, as shown in Figure 5.

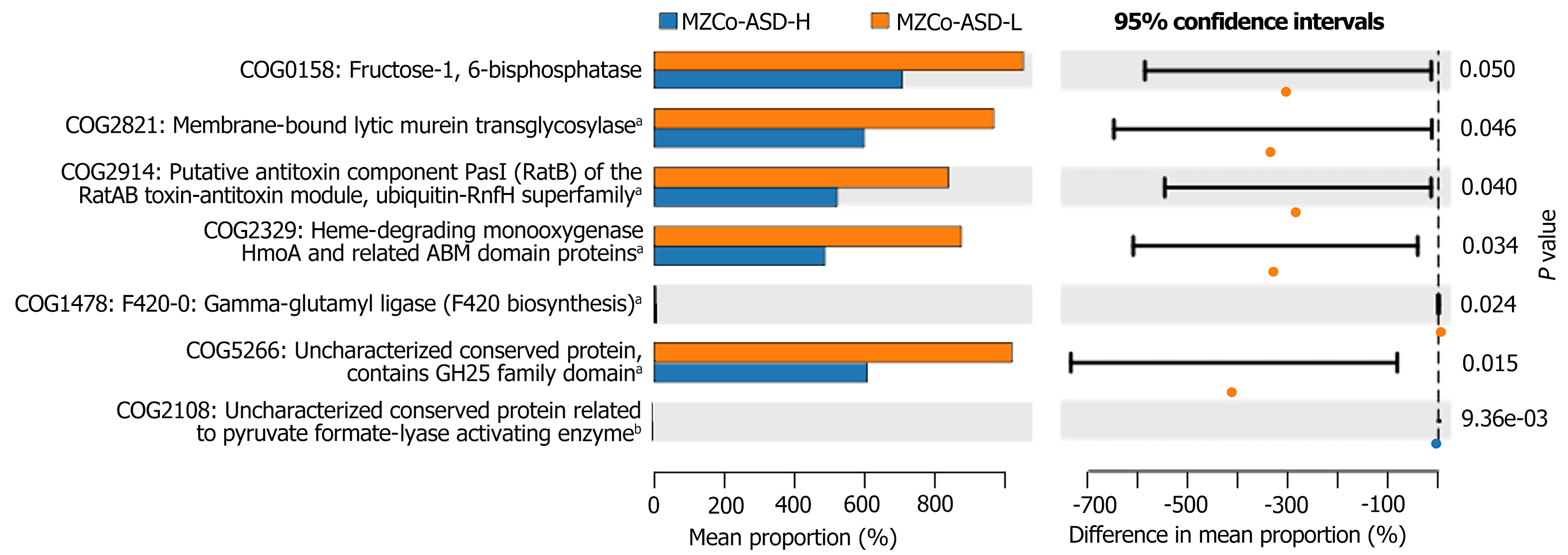

Functional differences in gut microbiota between the MZCo-ASD-H and MZCo-ASD-L groups were predicted using Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States, based on 16S rRNA sequencing data and the Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) functional classification database. As shown in Figure 6, five COG categories differed significantly between groups: COG1658 fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBP), which is associated with gluconeogenesis, more abundant in the MZCo-ASD-L group, and potentially linked to energy metabolism regulation; COG2821 (membrane-bound lytic murein transglycosylase), which is involved in bacterial cell wall remodeling and lysis and also enriched in the MZCo-ASD-L group; COG2914 (putative antitoxin component PasI of the RatAB toxin-antitoxin module), which is related to the toxin-antitoxin system, part of the ubiquitin family, and significantly higher in the MZCo-ASD-L group; COG2329 (heme-degrading monooxygenase HmoA), associated with heme degradation and significantly enriched in the MZCo-ASD-L group; and COG5286 (uncharacterized conserved protein containing a glycoside hydrolase family 25 family domain), which is potentially involved in glycoside hydrolase function and more abundant in the MZCo-ASD-L group. These findings suggest that, even after accounting for genetic background and environmental factors, individuals with differing ASD severity levels exhibit notable differences in the functional potential of their gut microbiota.

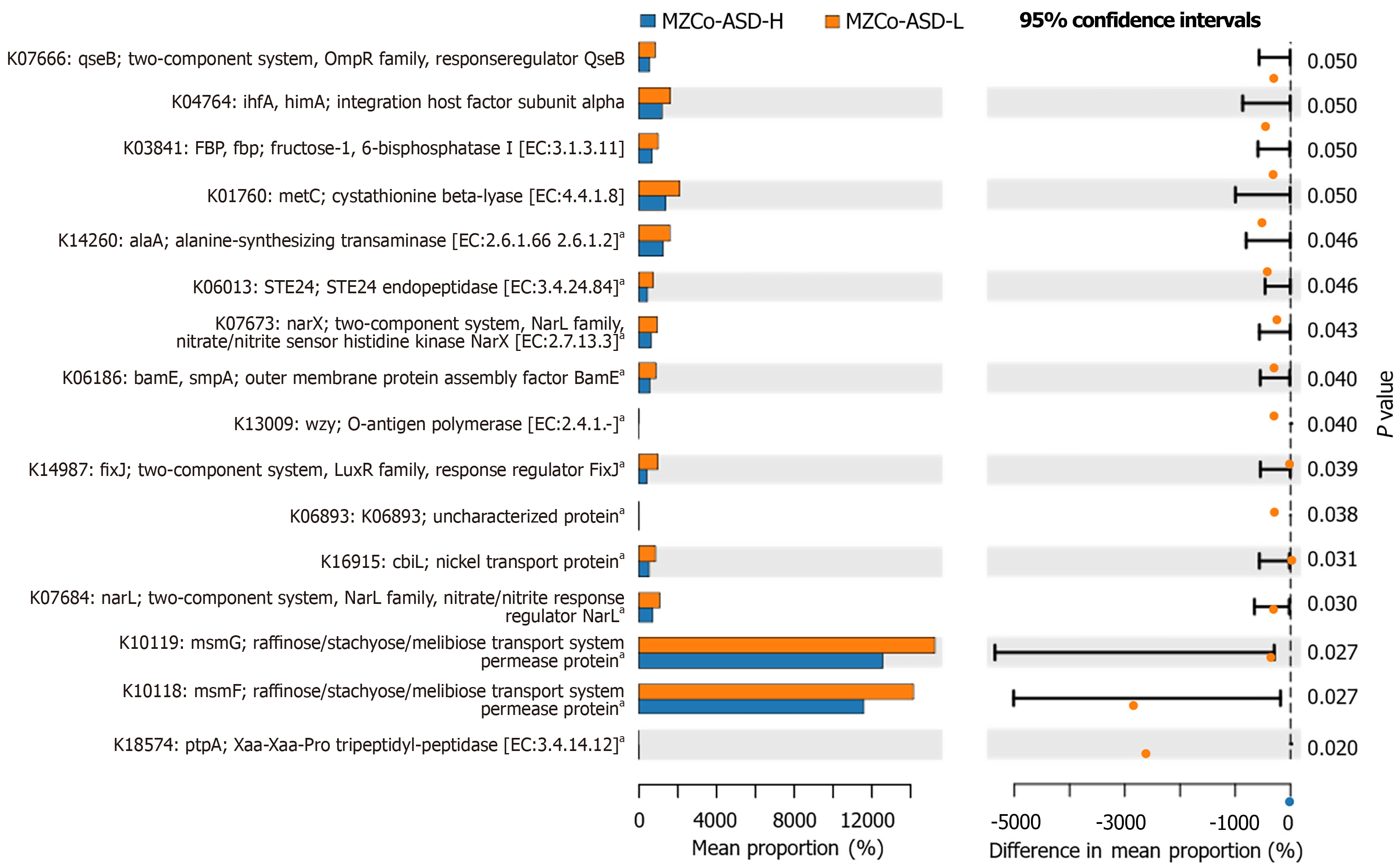

Next, we identified 16 statistically significant KO functions spanning key biological processes, including signal transduction, amino acid metabolism, cell wall biosynthesis, and substance transport (Figure 7). The most significant differences between the groups were observed in K10118 (msmF) and K10119 (msmG), both permease proteins of the raffinose/stachyose/melibiose transport system, which were significantly elevated in the MZCo-ASD-H group. This pattern may indicate altered efficiency of oligosaccharide uptake. Additional notable differences were observed in a two-component regulatory system (OmpR family response proteins, nitrate/nitrite sensing), functions associated with carbohydrate metabolism and transport (FBP), amino acid metabolic enzymes and protease functions (cystathionine β-lyase, alanine synthase), and membrane structure assembly and ion transport functions (BamE, CbiL). Overall, these KO predictions highlight pronounced differences in metabolic and regulatory pathways between the MZCo-ASD-H and MZCo-ASD-L groups. The gut microbiota of the MZCo-ASD-L group demonstrated greater potential for signal recognition, nutrient uptake, metabolic regulation, and membrane stability, reflecting a balanced ecological structure and metabolism. In contrast, the gut microbiota of the MZCo-ASD-H group exhibited diminished functionality in these areas.

This study examined the gut microbiome of MZs with ASD, focusing on microbiome composition and functional characteristics in twins with varying symptom severity, namely the MZCo-ASD-H (high-severity) and the MZCo-ASD-L (low severity) groups. We first compared the gut microbiota profiles of these groups. β-diversity analysis revealed substantial differences in microbiota structure, indicating distinct clustering patterns, whereas α-diversity indices showed no significant differences with symptom severity. These findings suggest that the overall gut microbiota composition may contribute to variations in ASD phenotype severity. The observed differences among MZs sharing an identical genetic background highlight the potential role of environmental factors - particularly the gut microbiome - in ASD symptom heterogeneity.

Compositional analysis revealed significant differences in the abundance of several genera. Notably, Porphyromonas was markedly enriched in the high-severity group. This genus, which includes species such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, comprises gram-negative anaerobic bacteria that produce lipopolysaccharides and other virulence factors that activate mucosal immune responses. This activation triggers the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1 beta, and interleukin-8, which contribute to increased intestinal permeability, commonly referred to as “leaky gut”[26,27]. These cytokines and toxic metabolites may also enter systemic circulation, influencing the development and behavior of the central nervous system[28,29]. Therefore, the elevated abundance of Porphyromonas in children with high-severity ASD may exacerbate clinical symptoms by activating chronic low-grade inflammatory pathways.

Further analysis revealed a reduction in the metabolic potential of the gut microbiota in the high-severity group, particularly in carbohydrate transport and amino acid metabolism. The most pronounced changes were observed in genes associated with carbohydrate transport, specifically K10118 (msmF) and K10119 (msmG). These genes encode permease proteins of the raffinose/stachyose/melibiose transport system, which is essential for the bacterial utilization of plant-derived oligosaccharides. This system belongs to the adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporter family, where permeases mediate the transmembrane transport of substrates for metabolic use[30,31]. Previous studies have shown that carbohydrate transport functions in the gut microbiota of children with ASD are frequently dysregulated, potentially affecting the production of SCFAs[32]. SCFAs, particularly propionate and acetate, play critical roles in regulating neurodevelopment across the blood-brain barrier, and animal studies have suggested that elevated propionate levels may contribute to ASD-like behaviors[33-35]. Additionally, several genes involved in the degradation of complex carbohydrates were significantly downregulated in the MZCo-ASD-H group. One notable example is K03841 (FBP), whose downregulation may indicate reduced microbial capacity to metabolize complex substrates such as dietary fiber. Furthermore, reduced expression of enzymes involved in amino acid metabolism was identified, including K01760 (cystathionine β-lyase, critical for methionine and cysteine metabolism) and K14260 (alanine synthase, alaA). Previous studies have shown that the gut microbiota in individuals with ASD often exhibits alterations in metabolic pathways related to complex carbohydrates, including dietary fiber and SCFA metabolism, as well as amino acid metabolism[36]. These alterations are often linked to the overgrowth of potentially harmful bacteria such as members of the genus Clostridium; however, probiotic interventions can help restore a more balanced microbial composition[37].

This study has several limitations. First, it was a single-center study restricted to MZs aged 2-6 years, with at least one twin diagnosed with ASD, resulting in a small sample size. Second, the lack of experimental validation limited the mechanistic investigation to association-level analyses. We did not conduct in vitro experiments to test whether Porphyromonas activates inflammatory pathways through lipopolysaccharides production to disrupt intestinal barrier permeability, nor did we measure key metabolites such as SCFAs, making it impossible to confirm the regulatory chain of the “gut microbiota-metabolite-brain axis”. Third, this study did not employ multiomics approaches, such as metagenomic sequencing or metabolomics, which could further clarify the predictive functions of microbial networks. Fourth, the dietary patterns of the twins were not analyzed as potential confounding factors, which may have introduced bias. Fifth, we did not examine in depth the associations between differences in microbial communities and the clinical phenotypes of ASD. Consequently, whether these microbial differences influence ASD severity or serve as biomarkers for severity was not explored. Future studies should therefore adopt a multicenter design with larger sample sizes and integrate multiomics with experimental validation to substantiate these findings.

In conclusion, our study identified significant alterations in the composition and functional potential of the gut microbiota in children with high-severity ASD. In particular, reduced SCFA production and impaired carbohydrate transport functions may exacerbate ASD behaviors through the gut-brain axis. These findings provide valuable insights into the ecological mechanisms underlying ASD symptom severity and highlight specific metabolic pathways or microbial genera as potential targets for future ASD interventions.

| 1. | Reiner O, Karzbrun E, Kshirsagar A, Kaibuchi K. Regulation of neuronal migration, an emerging topic in autism spectrum disorders. J Neurochem. 2016;136:440-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lord C, Elsabbagh M, Baird G, Veenstra-Vanderweele J. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet. 2018;392:508-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1136] [Cited by in RCA: 1363] [Article Influence: 170.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ducloy M, Tabet AC, Bouvard M, Bourgeron T, Delorme R. [Autism spectrum disorders: heterogeneous genetic etiologies]. Rev Prat. 2015;65:1179-1182. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Guevara-Ramírez P, Tamayo-Trujillo R, Ruiz-Pozo VA, Cadena-Ullauri S, Paz-Cruz E, Zambrano AK. Mechanistic Links Between Gut Dysbiosis, Insulin Resistance, and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:6537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Li J, Wang H, Qing W, Liu F, Zeng N, Wu F, Shi Y, Gao X, Cheng M, Li H, Shen W, Meng F, He Y, Chen M, Li Z, Zhou H, Wang Q. Congenitally underdeveloped intestine drives autism-related gut microbiota and behavior. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;105:15-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Taniya MA, Chung HJ, Al Mamun A, Alam S, Aziz MA, Emon NU, Islam MM, Hong SS, Podder BR, Ara Mimi A, Aktar Suchi S, Xiao J. Role of Gut Microbiome in Autism Spectrum Disorder and Its Therapeutic Regulation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:915701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Li Y, Luo ZY, Hu YY, Bi YW, Yang JM, Zou WJ, Song YL, Li S, Shen T, Li SJ, Huang L, Zhou AJ, Gao TM, Li JM. The gut microbiota regulates autism-like behavior by mediating vitamin B(6) homeostasis in EphB6-deficient mice. Microbiome. 2020;8:120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yu R, Hafeez R, Ibrahim M, Alonazi WB, Li B. The complex interplay between autism spectrum disorder and gut microbiota in children: A comprehensive review. Behav Brain Res. 2024;473:115177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yang C, Xiao H, Zhu H, Du Y, Wang L. Revealing the gut microbiome mystery: A meta-analysis revealing differences between individuals with autism spectrum disorder and neurotypical children. Biosci Trends. 2024;18:233-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhong JG, Lan WT, Feng YQ, Li YH, Shen YY, Gong JH, Zou Z, Hou X. Associations between dysbiosis gut microbiota and changes of neurotransmitters and short-chain fatty acids in valproic acid model rats. Front Physiol. 2023;14:1077821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jones J, Reinke SN, Mousavi-Derazmahalleh M, Palmer DJ, Christophersen CT. Changes to the Gut Microbiome in Young Children Showing Early Behavioral Signs of Autism. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:905901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Abuljadayel D, Alotibi A, Algothmi K, Basingab F, Alhazmi S, Almuhammadi A, Alharthi A, Alyoubi R, Bahieldin A. Gut microbiota of children with autism spectrum disorder and healthy siblings: A comparative study. Exp Ther Med. 2024;28:430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bonnechère B, Amin N, van Duijn C. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Neuropsychiatric Diseases - Creation of An Atlas-Based on Quantified Evidence. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:831666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Alamoudi MU, Hosie S, Shindler AE, Wood JL, Franks AE, Hill-Yardin EL. Comparing the Gut Microbiome in Autism and Preclinical Models: A Systematic Review. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:905841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu F, Li J, Wu F, Zheng H, Peng Q, Zhou H. Altered composition and function of intestinal microbiota in autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9:43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Qing L, Qian X, Zhu H, Wang J, Sun J, Jin Z, Tang X, Zhao Y, Wang G, Zhao J, Chen W, Tian P. Maternal-infant probiotic transmission mitigates early-life stress-induced autism in mice. Gut Microbes. 2025;17:2456584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Agrawal S, Rath C, Rao S, Whitehouse A, Patole S. Critical Appraisal of Systematic Reviews Assessing Gut Microbiota and Effect of Probiotic Supplementation in Children with ASD-An Umbrella Review. Microorganisms. 2025;13:545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Qiu Z, Luo D, Yin H, Chen Y, Zhou Z, Zhang J, Zhang L, Xia J, Xie J, Sun Q, Xu W. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum N-1 improves autism-like behavior and gut microbiota in mouse. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1134517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Vinberg M, Ottesen NM, Meluken I, Sørensen N, Pedersen O, Kessing LV, Miskowiak KW. Remitted affective disorders and high familial risk of affective disorders associate with aberrant intestinal microbiota. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;139:174-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hohlfeld R, Wekerle H. [Multiple sclerosis and microbiota. From genome to metagenome?]. Nervenarzt. 2015;86:925-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Karatzas PS, Gazouli M, Safioleas M, Mantzaris GJ. DNA methylation changes in inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Gastroenterol. 2014;27:125-132. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Gómez-Vallejo S, Leoni M, Ronald A, Colvert E, Happé F, Bolton P. Autism spectrum disorder and obstetric optimality: a twin study and meta-analysis of sibling studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;62:1353-1362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rosenberg RE, Law JK, Yenokyan G, McGready J, Kaufmann WE, Law PA. Characteristics and concordance of autism spectrum disorders among 277 twin pairs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:907-914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wong CC, Meaburn EL, Ronald A, Price TS, Jeffries AR, Schalkwyk LC, Plomin R, Mill J. Methylomic analysis of monozygotic twins discordant for autism spectrum disorder and related behavioural traits. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:495-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nordenbæk C, Jørgensen M, Kyvik KO, Bilenberg N. A Danish population-based twin study on autism spectrum disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23:35-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sato Y, Noguchi H, Kubo S, Kaku K, Okabe Y, Onishi H, Nakamura M. Modulation of allograft immune responses by Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide administration in a rat model of kidney transplantation. Sci Rep. 2024;14:13969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sugiyama N, Uehara O, Morikawa T, Paudel D, Ebata K, Hiraki D, Harada F, Yoshida K, Kato S, Nagasawa T, Miura H, Abiko Y, Furuichi Y. Gut flora alterations due to lipopolysaccharide derived from Porphyromonas gingivalis. Odontology. 2022;110:673-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Franciotti R, Pignatelli P, D'Antonio DL, Mancinelli R, Fulle S, De Rosa MA, Puca V, Piattelli A, Thomas AM, Onofrj M, Sensi SL, Curia MC. The Immune System Response to Porphyromonas gingivalis in Neurological Diseases. Microorganisms. 2023;11:2555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zhang J, Yu C, Zhang X, Chen H, Dong J, Lu W, Song Z, Zhou W. Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide induces cognitive dysfunction, mediated by neuronal inflammation via activation of the TLR4 signaling pathway in C57BL/6 mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Li J, Jing Q, Li J, Hua M, Di L, Song C, Huang Y, Wang J, Chen C, Wu AR. Assessment of microbiota in the gut and upper respiratory tract associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Microbiome. 2023;11:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Jamshad M, De Marco P, Pacheco CC, Hanczar T, Murrell JC. Identification, mutagenesis, and transcriptional analysis of the methanesulfonate transport operon of Methylosulfonomonas methylovora. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:276-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lagod PP, Naser SA. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Altered Microbiota Composition in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:17432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Sharma AR, Batra G, Saini L, Sharma S, Mishra A, Singla R, Singh A, Singh RS, Jain A, Bansal S, Modi M, Medhi B. Valproic Acid and Propionic Acid Modulated Mechanical Pathways Associated with Autism Spectrum Disorder at Prenatal and Neonatal Exposure. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2022;21:399-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | He Y, Zhang B, Xin Y, Wang W, Wang X, Liu Z, She Y, Guo R, Jia G, Wu S, Liu Z. Synbiotic combination of 2'-fucosyllactose and Bifidobacterium mitigates neurodevelopmental disorders and ASD-like behaviors induced by valproic acid. Food Funct. 2025;16:2703-2717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Hernández-Martínez C, Canals J, Voltas N, Martín-Luján F, Arija V. Circulating Levels of Short-Chain Fatty Acids during Pregnancy and Infant Neurodevelopment. Nutrients. 2022;14:3946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Deng W, Wang S, Li F, Wang F, Xing YP, Li Y, Lv Y, Ke H, Li Z, Lv PJ, Hao H, Chen Y, Xiao X. Gastrointestinal symptoms have a minor impact on autism spectrum disorder and associations with gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acids. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:1000419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Mohammad FK, Palukuri MV, Shivakumar S, Rengaswamy R, Sahoo S. A Computational Framework for Studying Gut-Brain Axis in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front Physiol. 2022;13:760753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/