Published online Feb 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.111050

Revised: September 3, 2025

Accepted: November 27, 2025

Published online: February 19, 2026

Processing time: 198 Days and 21.8 Hours

This study aimed to analyse the relationship between motor anxiety and rehabilitation outcomes in elderly stroke patients during the rehabilitation period, and to identify the key factors affecting motor anxiety.

To determine the impact of motor anxiety on rehabilitation outcomes in elderly stroke patients and to identify independent risk factors contributing to motor anxiety.

A retrospective analysis was conducted on stroke patients who underwent rehabilitation at our hospital from March 2021 to January 2024. Patients were divided into an exercise anxiety group [Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) ≥ 50, n = 139] and a non-exercise anxiety group (SAS < 50, n = 67) based on their SAS scores after rehabilitation training. Compare baseline data across the two patient groups and examine differences in the Modified Rankin Scale (mRS), Self-Efficacy for Exercise Scale (SEE), Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK), and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS). Correlations between the scores of the analysis functions were analysed. A logistic regression analysis was performed to identify inde

The mRS score (P < 0.001), TSK score (P < 0.001), and SDS score (P < 0.001) of patients in the exercise anxiety group were significantly higher than those of patients in the non-exercise anxiety group. In comparison, the SEE score (P < 0.001) was substantially lower than that of the non-exercise anxiety group. SAS was positively correlated with mRS (P = 0.015) and TSK (P < 0.01), and negatively correlated with SEE (P < 0.001). Logistic regression analysis showed that SEE score [P = 0.028, odds ratio (OR) = 8.94], TSK score (P = 0.027, OR = 8.7), SDS score (P = 0.012, OR = 9.727), educational level (P = 0.034, OR = 11.462), and monthly per capita income (P = 0.028, OR = 8.95) were independent risk factors affecting patients’ motor anxiety. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis showed that the model’s area under the curve for predicting patients’ motor anxiety was 0.887, and the externally validated model’s area under the curve was 0.646.

This study identified a significant negative relationship between motor anxiety and rehabilitation outcomes in elderly stroke patients during the rehabilitation period. The SEE, TSK, and SDS scores, along with lower edu

Core Tip: This retrospective study examines the impact of motor anxiety on rehabilitation outcomes in elderly stroke patients. Patients with higher anxiety levels showed poorer functional recovery, increased fear of movement, and lower self-efficacy. Using validated scales (Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, Modified Rankin Scale, Self-Efficacy for Exercise Scale, Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia, and Self-Rating Depression Scale), the study identified five independent risk factors for motor anxiety, including low self-efficacy, kinesiophobia, depression, and lower education and income. A predictive nomogram was developed and externally validated to evaluate motor anxiety risk. These findings emphasise the importance of psychological screening and personalised interventions during stroke rehabilitation to enhance functional outcomes and quality of life in elderly patients.

- Citation: Yang YB, Tang LP, Yu CY, Fu CL, Yang JP. Impact of motor anxiety on rehabilitation in elderly stroke patients: A retrospective study. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(2): 111050

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i2/111050.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.111050

According to the Global Burden of Disease Study, stroke is the second leading cause of death worldwide[1]. In China, stroke is the leading cause of death and disability among adults. Among people aged ≥ 40 years, the number of people with current or previous stroke is about 17.04 million[2]. Meanwhile, China’s disability-adjusted life years due to stroke are also significantly higher than the levels in developed countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States and Japan during the same period[3]. Among stroke survivors, about 70% of patients have varying degrees of disability, which not only seriously affects their quality of life but also poses significant safety issues[4].

Evidence-based medicine shows that stroke rehabilitation is the best way to reduce disability rates[5]. The fundamental aim of early stroke rehabilitation is to prevent complications, minimise impairments, and maximise functional recovery, so that patients can return to their families and society[6]. Studies have shown that stroke patients recover most quickly in the first three months of early rehabilitation, and that the pace of recovery begins to slow between three and six months[7]. Most patients reach their maximum recovery within six months. Exercise rehabilitation is a valuable part of stroke rehabilitation. Research shows that exercise rehabilitation can not only improve the motor function of stroke patients, but also enhance their cardiopulmonary function and promote the recovery of neurological function, thereby improving their quality of life[8].

However, many patients experience motor anxiety during the rehabilitation process. This anxiety may stem from uncertainty about the rehabilitation process, fear of re-injury, and doubts about their own ability to recover[9]. Exercise anxiety not only affects the patient’s motivation to recover, but it can also lead to a weakening of the recovery effect and even trigger other psychological problems[10]. This anxiety not only affects the patient’s psychological state but can also lead to a series of adverse conditions. For example, exercise anxiety can increase the patient’s heart rate and blood pressure fluctuations, resulting in excessive fatigue or an increased risk of cardiovascular events during exercise[11]. In addition, anxiety can also cause patients to experience sleep disorders, loss of appetite, and other problems, which further weaken their body’s ability to recover[12]. Research reports that persistent motor anxiety may lead to symptoms such as stiffness of movement, poor coordination, and delayed response in patients during rehabilitation training, which affects the rehabilitation effect[13,14].

This study aimed to analyse the relationship between motor anxiety and rehabilitation outcomes in elderly stroke patients during the rehabilitation period. Through a single-centre retrospective study, we hope to identify the specific impact of motor anxiety on rehabilitation outcomes and provide a reference for clinical treatment and intervention.

Retrospective analysis of stroke patients who received rehabilitation treatment at our hospital from March 2021 to January 2023, as the subject of this study, as the training group; in addition, stroke patients who received rehabilitation treatment at our hospital from February 2023 to January 2024 were collected as the verification group for the study. The hospital’s Medical Ethics Committee approved this study (approval No. 202401027).

Inclusion criteria: Diagnosis according to the stroke guidelines[15]; diagnosis of stroke by a doctor based on a computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the head; onset of symptoms within the last 6 months; age ≥ 55 years; complete clinical data.

Exclusion criteria: Severe chronic diseases combined: Heart failure, respiratory failure, severe malnutrition, etc.; motor dysfunction caused by other neurological diseases or lower limb fractures; combined malignant tumours and other diseases; patients who have been pregnant, preparing for pregnancy or suspected pregnancy within the past 6 months.

Core muscle strength training programme: This includes sit-ups and intentional contraction exercises for the internal and external abdominal oblique muscles to strengthen the abdominal muscles. At the same time, single- and double-bridge training are alternated to gradually guide the patient through the transition between open- and closed-chain movements. Each training session lasts 15 minutes and aims to comprehensively activate the core muscles and improve muscle coordination and stability.

Torso control strengthening training programme: Using the Bobath handshake turning technique, supplemented by abdominal breathing, to stimulate the engagement and contraction of the abdominal muscles. Each session lasts 15 minutes and aims to enhance the patient’s control over the torso and further strengthen the abdominal muscles through breathing.

Balanced standing strengthening training programme: Training on a special balance mat involves gradually progressing from standing with eyes open to standing with eyes closed, and from standing on one foot on the healthy side to standing on one foot on the affected side. Training for 10 minutes a day improves the patient’s sense of balance and standing stability.

Intensive walking training programme: Patients are gradually guided out of bed for systematic walking training, with the intensity gradually increasing. Professionals accompany them throughout the process to ensure safety. The intensity of training is adjusted according to the patient’s tolerance.

Good limb activity therapy: A professional team assists the patient in extending the elbow joint and dorsiflexing the wrist joint, while maintaining a 90° flexion of the shoulder joint of the good limb in the supine position, and ensuring wrist extension at the same time.

Lifting and strengthening training plan: Patients are encouraged to repeatedly lift their hands above their heads while crossing their arms. At the same time, the biceps and deltoids are massaged and pressed to promote muscle relaxation and relief.

Joint rehabilitation training programme: Including exercises for the trunk muscles such as turning over, sitting up, crossing legs, swinging the shoulders, shrugging the shoulders, etc., sitting balance training, dorsiflexion and knee flexion exercises, sitting and standing balance training, loading training of the affected lower limb, walking, going up and down stairs and wheelchair use exercises, and guidance on training of daily living skills. Each training session lasts 30 minutes, twice a day for 4 weeks.

The Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) was used to assess the patient’s anxiety state after 4 weeks of rehabilitation exercises[16]. The SAS is used to determine the symptoms and severity of anxiety in patients. The score ranges from 20 to 80, with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety. A score of 50-59 indicates mild anxiety, 60-69 indicates moderate anxiety, and a score of 70 or higher indicates severe anxiety.

A total of 206 eligible cases were collected from the training group according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patients with a score ≥ 50 were assessed as the exercise anxiety group (n = 139), and those with a score < 50 were evaluated as the non-exercise anxiety group (n = 67). A total of 97 cases were collected in the validation group, including 61 exercise anxiety patients and 36 non-exercise anxiety patients.

Modified Rankin Scale: The Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) is used to assess the degree of disability and functional recovery in stroke patients. The score ranges from 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating more severe disability[17].

Self-Efficacy for Exercise Scale: The Self-Efficacy for Exercise Scale (SEE) assesses the patient’s confidence and sense of self-efficacy in performing the exercises. The score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater confidence in adhering to the exercises[18].

Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia: The Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK) is used to assess the patient’s fear of movement, especially the fear that movement may cause pain or re-injury. The score ranges from 17 to 68, with higher scores indicating greater fear of movement[19].

Self-Rating Depression Scale: The Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) is used to assess the symptoms and severity of depression in patients. The score ranges from 20 to 80, with higher scores indicating more severe depression[20].

Patient-related information is obtained through electronic medical records and outpatient review records. Mainly includes age, gender, body mass index, history of diabetes, history of hypertension, educational level, monthly per capita income, medical insurance payment method, marital status, work status, type of stroke, number of discomfort symptoms, number of strokes, comorbidities, history of falls and heart insufficiency. Functional scores include SAS, SDS, mRS, SEE, and TSK for patients after 4 weeks of motor rehabilitation.

Outcome measurement: (1) Compare the differences in baseline information between patients in the exercise anxiety group and the non-exercise anxiety group; (2) Compare the difference in SDS, mRS, SEE, and TSK scores between patients in the exercise anxiety group and the non-exercise anxiety group; (3) Correlations between SAS scores and SDS, mRS, SEE, and Pearson’s test were analysed for TSK scores; (4) Logistics regression was used to analyse the risk factors affecting patients’ exercise anxiety; (5) A nomogram was used to construct a visualisation model of motion anxiety, and in addition, a dynamic prediction model was constructed by the online tool shinyapps.io; and (6) Validate the value of the model with external data.

SPSS 26.0 statistical software was used, and the measurement information was expressed as mean ± SD, and an independent samples t-test was used for comparison between groups. Count data were expressed as a percentage or rate (%), and the χ2 test was performed. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to analyse the diagnostic value of SDS, mRS, SEE, and TSK in patients with exercise anxiety. Logistic regression was used to analyse the independent risk factors affecting exercise anxiety in patients. Nomograms were plotted and calibration curves analysed using the rms package in the R software (4.3.2), ROC curves were analysed using pROC, decision curve analysis (DCA) curves were analysed using the Decision Curve package, and visualisation of all images was performed by ggplot2. When P < 0.05, the difference is statistically significant.

The current study compared the baseline data of patients with and without exercise anxiety. The results showed that age (P = 0.003), literacy (P = 0.026), and monthly household income (P = 0.008) differed between patients in the exercise anxiety group and those in the non-exercise anxiety group (Table 1).

| Factors | Exercise anxiety group (n = 139) | Non-exercise anxiety group (n = 67) | χ2 | P value | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| ≤ 60 | 49 | 32 | 11.478 | 0.003 | |

| 61-69 | 69 | 17 | |||

| ≥ 70 | 21 | 18 | |||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 86 | 48 | 1.899 | 0.168 | |

| Female | 53 | 19 | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||

| ≥ 25 | 39 | 15 | 0.751 | 0.386 | |

| < 25 | 100 | 52 | |||

| History of diabetes | |||||

| Yes | 31 | 11 | 0.964 | 0.326 | |

| No | 108 | 56 | |||

| History of hypertension | |||||

| Yes | 43 | 17 | 0.678 | 0.410 | |

| No | 96 | 50 | |||

| Educational level | |||||

| ≤ Junior high school | 63 | 21 | 7.322 | 0.026 | |

| High school | 61 | 30 | |||

| ≥ University | 15 | 16 | |||

| Per capita monthly income (CNY) | |||||

| < 3000 | 63 | 24 | 9.744 | 0.008 | |

| 3000-4500 | 62 | 25 | |||

| > 4500 | 14 | 18 | |||

| Medical insurance type | |||||

| Employee insurance | 70 | 34 | 0.400 | 0.819 | |

| Rural/urban insurance | 56 | 25 | |||

| Self-pay | 13 | 8 | |||

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 124 | 62 | 0.571 | 0.450 | |

| Other | 15 | 5 | |||

| Employment status | |||||

| Employed | 95 | 48 | 0.231 | 0.630 | |

| Retired | 44 | 19 | |||

| Stroke type | |||||

| Hemorrhagic | 39 | 15 | 0.751 | 0.386 | |

| Ischemic | 100 | 52 | |||

| Number of symptoms | |||||

| ≥ 2 | 95 | 50 | 0.856 | 0.355 | |

| < 2 | 44 | 17 | |||

| Stroke occurrence | |||||

| First occurrence | 108 | 46 | 1.958 | 0.162 | |

| Recurrence | 31 | 21 | |||

| Comorbidities | |||||

| ≥ 2 | 97 | 46 | 0.027 | 0.869 | |

| < 2 | 42 | 21 | |||

| Fall history | |||||

| ≥ 2 | 124 | 57 | 0.725 | 0.395 | |

| < 2 | 15 | 10 | |||

| Heart failure | |||||

| Yes | 49 | 19 | 0.972 | 0.324 | |

| No | 90 | 48 | |||

In this study, we compared mRS, SEE, TSK, and SDS scores in patients with and without exercise anxiety. It was found that exercise anxiety group patients had significantly higher mRS scores (P < 0.001), TSK scores (P < 0.001), and SDS scores (P < 0.001) than non-exercise anxiety group patients, and exercise anxiety group patients had significantly higher SEE scores (P < 0.001), which were statistically lower than non-exercise anxiety group patients (Table 2).

| Functionality scores | Exercise anxiety group (n = 139) | Non-exercise anxiety group (n = 67) | Z/t | P value |

| mRS score, median (IQR) | 2.00 (2.00, 2.00) | 2.00 (1.00, 2.00) | 2.454 | < 0.001 |

| SEE score | 35.70 ± 16.22 | 53.58 ± 14.05 | -8.128 | < 0.001 |

| TSK score | 61.34 ± 4.89 | 54.15 ± 5.65 | 8.923 | < 0.001 |

| SDS score | 40.19 ± 5.49 | 37.51 ± 4.90 | 3.542 | < 0.001 |

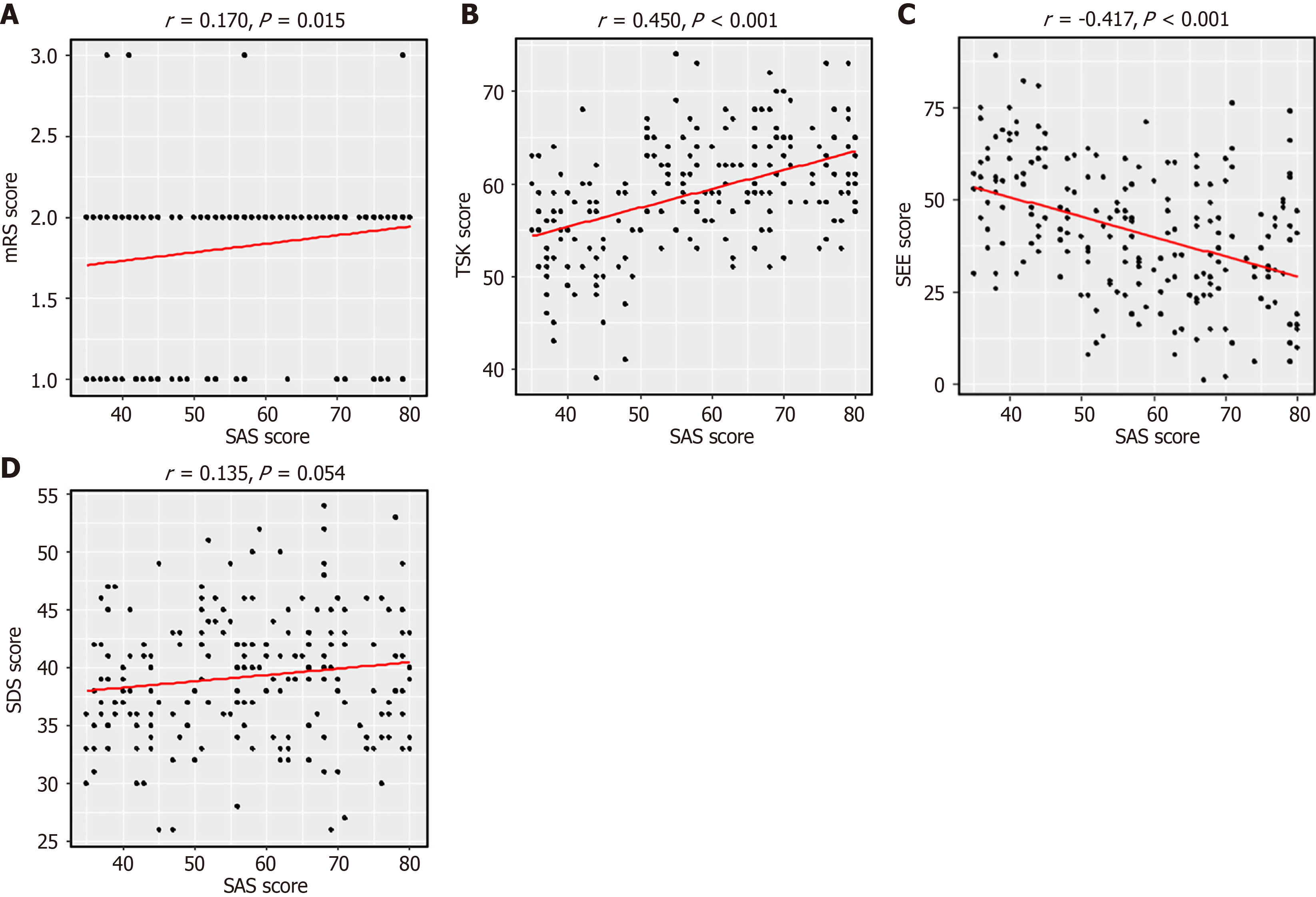

In the current study, the correlations among SAS, mRS, SEE, TSK, and SDS were analysed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. It was found that SAS was positively correlated with mRS (r = 0.170, P = 0.015; Figure 1A) and TSK (r = 0.450, P < 0.01; Figure 1B), whereas it was negatively correlated with SEE (r = -0.417, P < 0.001; Figure 1C). There was no correlation with SDS (P > 0.05; Figure 1D).

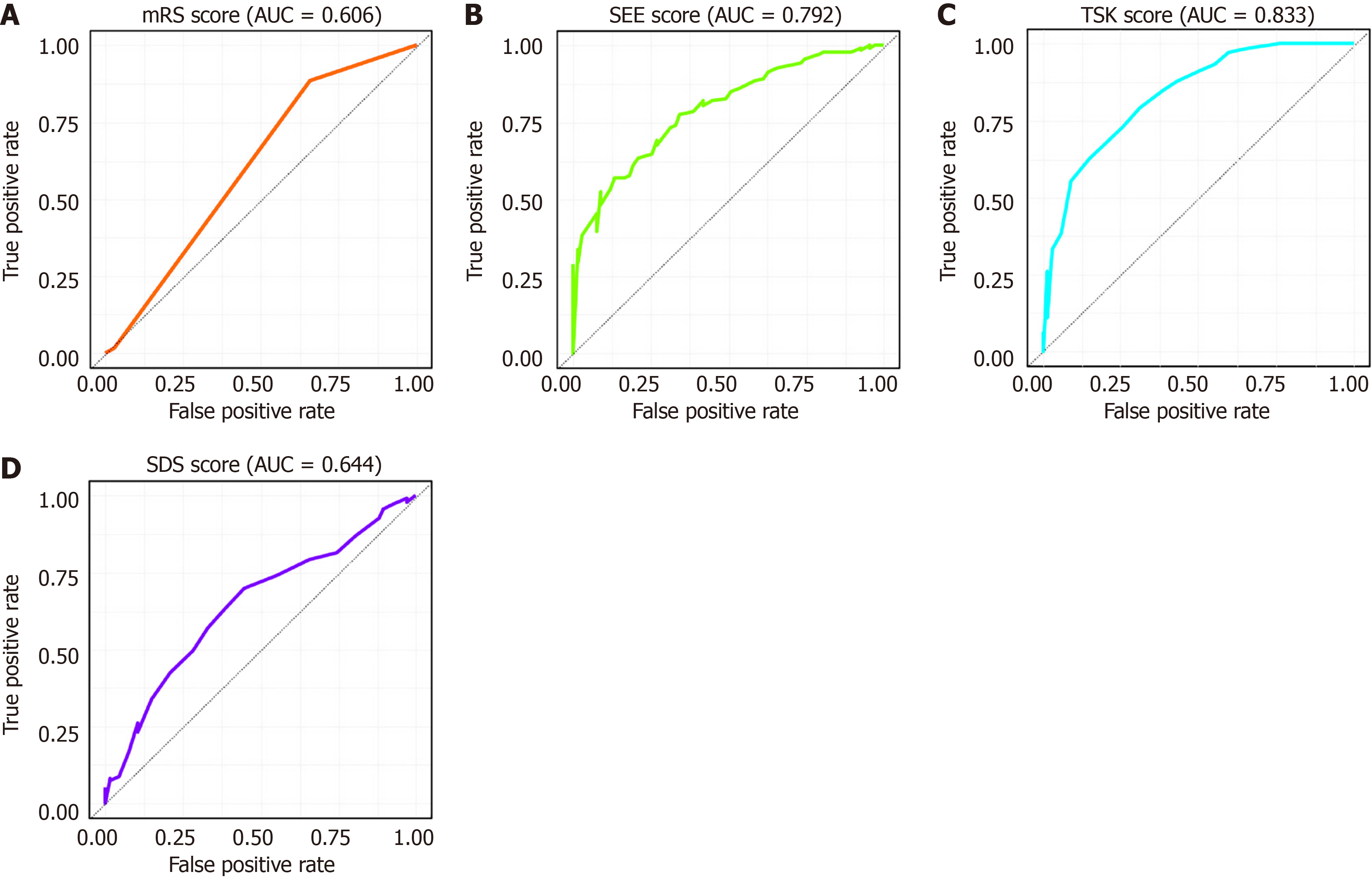

To further identify the risk factors influencing patients' exercise anxiety, we analysed these factors using logistic regression. Since logistic regression is more appropriate for analysing categorical data, we performed a binary transformation of mRS, SEE, TSK, and SDS, using the ROC cut-off values as thresholds for categorisation (Figure 2, Table 3). We then assigned values to each factor (Table 4). A multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that SEE score [P = 0.028, odds ratio (OR) = 8.94], TSK score (P = 0.027, OR = 8.7), SDS score (P = 0.012, OR = 9.727), educational level (P = 0.034, OR = 11.462), and per capita monthly income (P = 0.028, OR = 8.95) were independent risk factors affecting patients’ exercise anxiety (Table 5).

| Markers | AUC | 95%CI | Specificity | Sensitivity | Cut off |

| mRS score | 0.606 | 0.539-0.673 | 34.33% | 88.49% | 1.5 |

| SEE score | 0.792 | 0.731-0.854 | 91.04% | 52.52% | 35.5 |

| TSK score | 0.833 | 0.775-0.891 | 68.66% | 79.14% | 57.5 |

| SDS score | 0.644 | 0.565-0.722 | 55.22% | 69.78% | 37.5 |

| Factors | Content of the assignments |

| Age (years) | ≤ 60 = 1, 61-69 = 2, ≥ 70 =3 |

| Educational level | ≤ Junior high school = 1, high school = 2, ≥ university = 3 |

| Per capita monthly income | < 3000 = 1, 3000-4500 = 2, > 4500 = 3 |

| mRS score | ≤ 1.5 = 0, > 1.5 = 1 |

| SEE score | ≤ 35.5 = 0, > 35.5 = 1 |

| TSK score | ≤ 57.5 = 0, > 57.5 = 1 |

| SDS score | ≤ 37.5 = 0, > 37.5 = 1 |

| Anxiety status | Exercise anxiety = 1, non-exercise anxiety group = 0 |

| Factors | β | SD | χ2 | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| mRS score | 0.919 | 0.485 | 3.584 | 0.058 | 2.507 | 0.968-6.491 |

| SEE score | -2.270 | 0.528 | 18.462 | < 0.001 | 0.103 | 0.037-0.291 |

| TSK score | 2.038 | 0.410 | 24.739 | < 0.001 | 7.672 | 3.437-17.124 |

| SDS score | 0.896 | 0.407 | 4.847 | 0.028 | 2.45 | 1.103-5.440 |

| Age (years) | 0.262 | 0.258 | 1.032 | 0.310 | 1.300 | 0.784-2.156 |

| Educational level | -0.793 | 0.293 | 7.347 | 0.007 | 0.452 | 0.255-0.803 |

| Per capita monthly income | -0.82 | 0.294 | 7.792 | 0.005 | 0.441 | 0.248-0.783 |

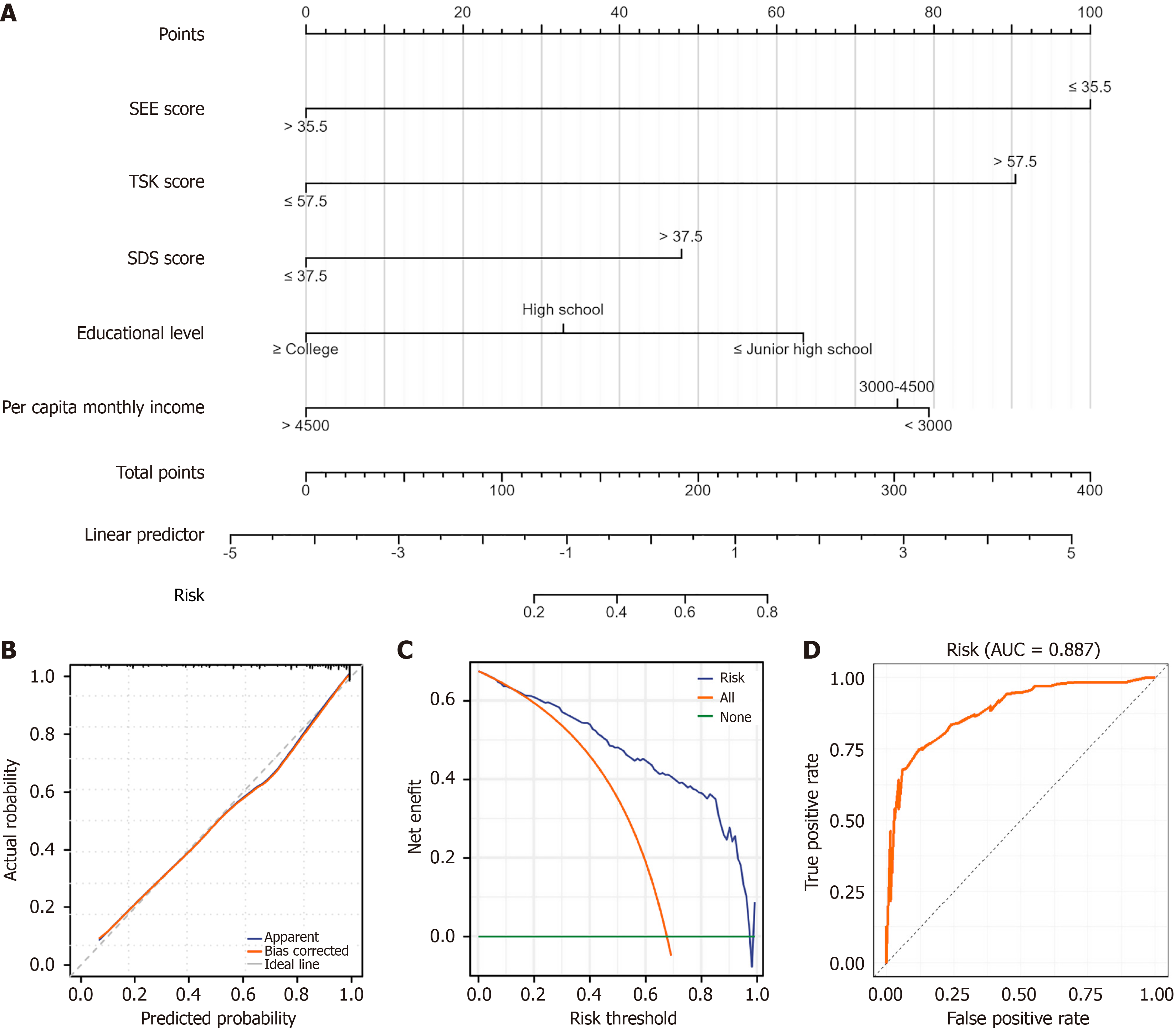

The study concluded with the construction of an exercise anxiety prediction model. The nomogram model contains five independent risk factors, with SEE scores having the largest share, followed by TSK, per capita monthly income, educational level, and SDS scores. This order also indicates the strength of the correlation between each indicator and exercise anxiety (Figure 3A). Subsequently, we evaluated the model’s stability, clinical benefit, and predictive value using calibration, DCA, and ROC curves, respectively. The calibration curves showed that the model curve (red) nearly overlaps the ideal curve (grey), indicating that the model is stable (Figure 3B). And DCA curve analysis found that the model was beneficial in 0%-99%, and its highest benefit rate was 67.47% (Figure 3C). And the ROC curve analysis found that the model’s area under the curve (AUC) for predicting patients’ exercise anxiety was 0.887, with an accuracy of 79.13%, specificity of 88.06%, and sensitivity of 74.82% (Figure 3D). To make the model more clinically applicable, we used the online tool shinyapps.io to construct a dynamic prediction model that directly calculates the incidence of exercise anxiety in patients by outputting various indicators (https://Laoniannaozuzhongyundongjiaolv.shinyapps.io/DynNomapp/).

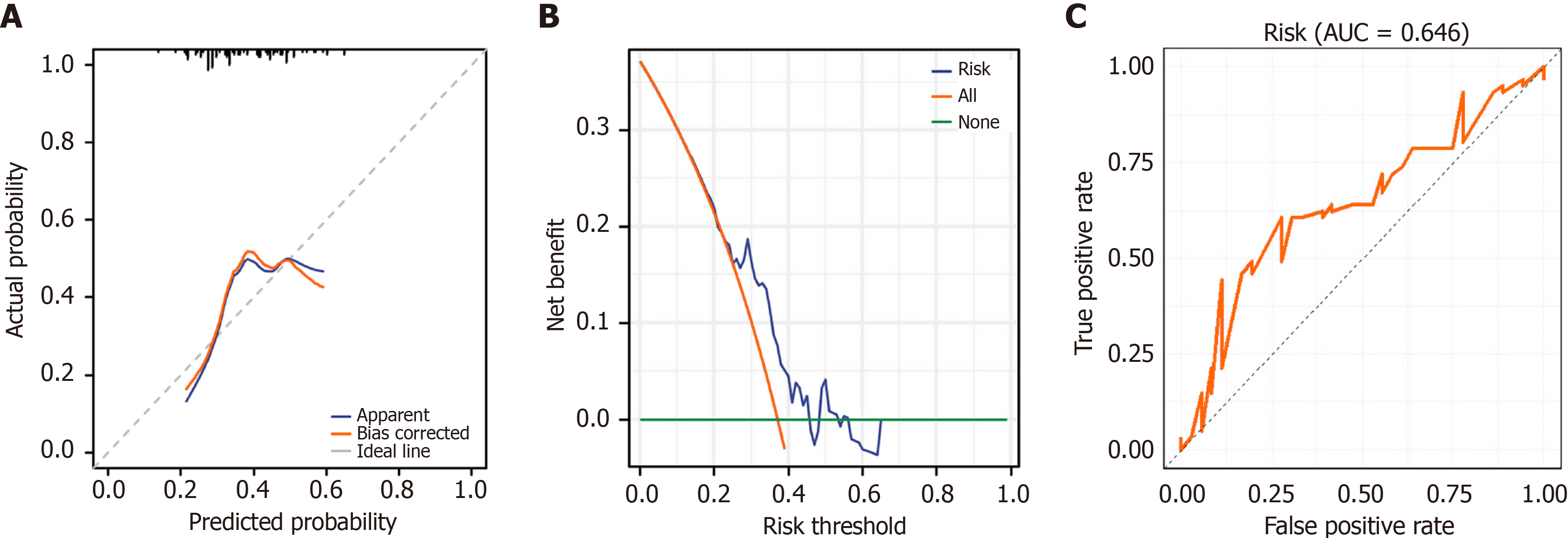

To assess the model’s value in this study, we used a validation group. First, we compared the differences in 5 risk factors between the training and validation groups. The results showed that there was no statistically significant difference in SEE score (P = 0.370), TSK score (P = 0.687), SDS score (P = 0.833), education level (P = 0.936), and per capita monthly income (P = 0.908) between the patients in the training group and those in the validation group (Table 6). A risk score was then calculated for each patient based on the risk modelling formula: 1.243 + SEE score ≤ 35.5 × 2.331 + TSK score ≤ 57.5 × (-2.109) + SDS score > 37.5 × 1.115 + educational level, high school × (-0.714) + educational level ≥ college × (-1.478) + per capita monthly income > 4500 × (-1.756) + per capita monthly income < 3000 × 0.094. The intersection of the model curve (red) with the ideal curve (grey) was determined by curve calibration (Figure 4A). The DCA curve analysis showed that the model was beneficial across 0%-64%, with a maximum benefit of 37.10% (Figure 4B). The DCA curve analysis showed that the model was beneficial across 0%-64%, with a maximum benefit of 37.10% (Figure 4B). Discrimination in the validation cohort was modest (ROC AUC = 0.646; Figure 4C).

| Factor | Training group (n = 206) | Validation group (n = 97) | Statistics | P value |

| SEE score, median (IQR) | 42.00 (29.00, 55.00) | 35.00 (28.00, 55.00) | Z = 1.021 | 0.307 |

| TSK score, mean ± SD | 59.00 ± 6.15 | 58.70 ± 5.96 | t = 0.403 | 0.687 |

| SDS score, median (IQR) | 39.00 (35.25, 43.00) | 39.00 (32.00, 49.00) | Z = -0.205 | 0.838 |

| Educational level | χ2 = 0.131 | 0.936 | ||

| ≤ Junior high school | 84 (40.8) | 38 (39.2) | ||

| High school | 91 (44.2) | 43 (44.3) | ||

| ≥ University | 31 (15.0) | 16 (16.5) | ||

| Per capita monthly income (CNY) | χ2 = 0.193 | 0.908 | ||

| < 3000 | 84 (40.8) | 38 (39.2) | ||

| 3000-4500 | 91 (44.2) | 43 (44.3) | ||

| > 4500 | 31 (15.0) | 16 (16.5) |

Stroke is one of the major diseases that seriously affects the health of the elderly population worldwide. It is particularly prominent in China, where the incidence of stroke is increasing with the ageing of the population[21]. Rehabilitation is crucial for the functional recovery of stroke patients, but during the rehabilitation process, exercise anxiety becomes one of the critical factors affecting the patient’s rehabilitation outcomes[22]. Studies have shown that exercise anxiety significantly reduces patients’ motivation and adherence to rehabilitation, leading to poor training outcomes[23]. Exercise anxiety can arise from a variety of factors, including uncertainty about the rehabilitation process, fear of re-injury, and doubts about one’s ability to recover[24]. These psychological factors not only affect the patient’s mental health, but may also trigger a range of physiological problems such as fluctuating heart rate and blood pressure, sleep disturbances and loss of appetite, which can further undermine rehabilitation outcomes. The psychological mechanisms underlying exercise anxiety in stroke rehabilitation may share similarities with “catastrophizing” phenomena observed in chronic pain research. Catastrophizing, characterised by patients’ exaggerated cognitive appraisal of movement-related threats, has been extensively studied in pain management[25]. In stroke rehabilitation, similar mechanisms may lead patients to avoid exercise due to fear of re-injury, which could be closely related to elevated TSK scores observed in our study. Furthermore, exercise anxiety often co-occurs with other post-stroke psychological conditions, such as post-stroke fatigue and apathy, which may collectively impede rehabilitation engagement. Future research should explore the interactive effects of these psychological factors to develop more comprehensive intervention strategies.

In the present study, we found that the mRS, TSK, and SDS scores of patients in the exercise anxiety group were significantly higher than those of the non-exercise anxiety group. In contrast, the SEE scores were substantially lower than those of the non-exercise anxiety group. Specifically, high mRS scores in exercise anxiety group patients indicate a higher level of disability, high TSK scores show a higher level of fear of exercise, and high SDS scores reflect the presence of severe depressive symptoms in these patients. Conversely, low SEE scores indicate that exercise anxiety group patients have less confidence in performing exercise independently. Although our correlation analysis revealed a significant association between SAS and mRS (r = 0.170, P < 0.05), the relatively weak correlation suggests that exercise anxiety accounts for only a small proportion of disability variance. This indicates that other unmeasured factors, such as lesion location, stroke severity, or pre-morbid physical fitness, may have a greater influence on functional outcomes. Moreover, the relationship between exercise anxiety and disability may be bidirectional: While anxiety may impair recovery by reducing rehabilitation adherence, severe functional limitations could equally exacerbate anxiety, creating a vicious cycle that further compromises rehabilitation outcomes. This is mainly because exercise anxiety leads to low adherence to rehabilitation and psychological stress, which in turn affects rehabilitation outcomes and increases disability[26]. Fear of pain and re-injury and lack of knowledge about exercise safety lead to increased fear of exercise; chronic psychological stress and social isolation increase the risk of depression; and lack of past successes and negative self-appraisal weaken the sense of self-efficacy for exercise[27]. By providing psychological support, enhancing education on exercise safety, and improving self-efficacy, it is possible to reduce exercise anxiety and improve rehabilitation outcomes effectively. In a previous study by Farris et al[28], patients undergoing cardiovascular and pulmonary rehabilitation were found to avoid aerobic exercise due to fear of exercise-induced sensations. That fear and avoidance behaviours towards exercise are prevalent amongst rehabilitating patients, and that these behaviours are associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression, lower health-related quality of life, and stronger beliefs about the utility of anxiety treatments. In addition, a study by Kraemer et al[29] found that anxiety leads to decreased exercise adherence in cardiopulmonary rehabilitation patients.

Identifying risk factors in patients with exercise anxiety can help in early detection and intervention, thus preventing problems such as low adherence and psychological stress during the rehabilitation process, which in turn affects rehabilitation outcomes. In the present study, we found that the SEE, TSK, and SDS scores, educational level, and per capita monthly income were independent risk factors for exercise anxiety, as determined through analysis. However, it should be noted that our study did not include objective motor function assessments (e.g., Fugl-Meyer scores), which may limit our ability to evaluate the independence of psychological factors, such as SEE and TSK, from physical limitations. Future research could strengthen these findings by adjusting for objective motor impairments to verify whether these psychological factors persist independently of physical constraints. Patients with low SEE scores were less motivated and engaged in rehabilitation, which significantly affected rehabilitation outcomes. In addition, low SEE is not only directly related to patients’ exercise anxiety, but also further exacerbates their anxiety by affecting their psychological state[30]. Chen et al[31] in their study suggested that the incidence of kinesiophobia was higher in patients with stroke hemiplegia and that anxiety was an independent risk factor leading to the development of kinesiophobia in patients. Patients with high TSK scores often exhibit resistance and avoidance behaviours towards exercise during rehabilitation, resulting in poor training outcomes. It is essential to distinguish whether high TSK scores reflect irrational anxiety or realistic concerns about falls and re-injury risk. Some patients’ fear of movement may stem from legitimate safety concerns rather than purely psychological barriers. Future studies could employ supplementary assessments or interviews to differentiate between these factors. For example, Bąk et al[32] found in a survey of elderly patients after ischaemic stroke in Poland that more than 78% of the population had kinesiophobia and they emphasised that kinesiophobia was strongly associated with debilitating syndromes, anxiety and disease acceptance. High SDS scores indicate the presence of more severe depression, which not only affects the quality of their daily life but also significantly reduces their motivation and adherence to participate in rehabilitation training. Bermudez et al[33], who proposed that exercise rehabilitation for hospital admissions due to cardiac disease should be screened for symptoms of depression and anxiety, found in their study that anxiety and depression were negatively correlated with patients’ exercise rehabilitation.

Patients with lower educational levels usually lack rehabilitation knowledge and skills and have increased uncertainty about the rehabilitation process, leading to anxiety[34]. At the same time, these patients have limited access to information, find it difficult to understand the rehabilitation advice and materials provided by doctors, have a low sense of self-efficacy, and have little confidence in their ability to recover. At the same time, these patients have limited access to information, find it difficult to understand the rehabilitation advice and materials provided by doctors, have a low sense of self-efficacy, and have little confidence in their ability to recover. In addition, patients with low educational levels often have limited social support and a lack of support from peers or the community, which further aggravates their sense of isolation and helplessness[35]. Patients with lower per capita monthly incomes face greater financial pressures, and the issue of the cost of rehabilitation treatment may trigger anxiety, limiting their access to high-quality rehabilitation counselling and support, with a lower quality of life and a weaker sense of wellness[36]. These factors combine to make low-income patients feel more isolated in their recovery, creating a cycle of negative emotions and increasing the inci

Identifying and understanding these factors can help clinicians and rehabilitation specialists identify high-risk patients early, implement effective interventions, and improve rehabilitation outcomes. By performing multivariate logistic regression analyses on these factors, we found that they had significant independent predictive value for exercise anxiety prevalence. Through ROC curve analysis, we found that the model’s AUC for predicting patients’ exercise anxiety was 0.887, and the DCA and calibration curves also indicated that the model has a clinically meaningful benefit rate and stability. Nevertheless, our externally validated AUC was only 0.646, mainly due to the small sample size. In addition, we did not use data from the same time period to split into two groups; instead, we used samples collected in a new time period, which may also have led to larger differences in the results. Therefore, future studies need larger, more diverse samples to validate further and optimise the model’s predictive performance. While our nomogram offers a potential tool for identifying high-risk patients, its clinical effectiveness requires multicenter external validation and adaptation across different clinical settings. The model should be tested across diverse populations and healthcare systems to ensure its generalizability. Future research could explore integrating this predictive model into existing rehabilitation assessment workflows or developing simplified versions suitable for mobile devices to facilitate clinical implementation.

There are still some limitations to this study. Firstly, the sample size is relatively small, limiting the broad applicability and statistical significance of the results. Secondly, the study was conducted in a single centre and lacked multicentre data, which may affect the generalisability and external validity of the results. The retrospective design of our study limits causal inferences about the relationship between exercise anxiety and functional outcomes. Unmeasured confounding factors may influence the observed associations, and we cannot definitively establish whether exercise anxiety directly impairs recovery or whether poor functional outcomes exacerbate anxiety. Finally, the lack of long-term follow-up data prevents us from assessing the changes and effects of exercise anxiety and related factors during long-term rehabilitation. Future studies should increase sample size to include more patients from diverse geographical areas and healthcare institutions, and conduct multicentre studies to improve the external validity of the results. There is also a need to reduce information bias and selection bias, and to monitor changes in exercise anxiety and rehabilitation effects through long-term follow-up. Future research should employ longitudinal or interventional designs, such as randomised controlled trials, to test whether psychological interventions (e.g., cognitive-behavioural therapy or graded exposure therapy) can effectively reduce exercise anxiety and directly improve rehabilitation outcomes.

This study revealed a significant negative correlation between exercise anxiety and rehabilitation outcome in elderly stroke patients during rehabilitation. SEE, TSK and SDS scores, as well as lower literacy and per capita monthly income, were independent risk factors for exercise anxiety during rehabilitation in elderly stroke patients.

| 1. | Prust ML, Forman R, Ovbiagele B. Addressing disparities in the global epidemiology of stroke. Nat Rev Neurol. 2024;20:207-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wu S, Wu B, Liu M, Chen Z, Wang W, Anderson CS, Sandercock P, Wang Y, Huang Y, Cui L, Pu C, Jia J, Zhang T, Liu X, Zhang S, Xie P, Fan D, Ji X, Wong KL, Wang L; China Stroke Study Collaboration. Stroke in China: advances and challenges in epidemiology, prevention, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:394-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 645] [Cited by in RCA: 1133] [Article Influence: 188.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zhu Y, Wang Y, Shrikant B, Tse LA, Zhao Y, Liu Z, Wang C, Xiang Q, Rangarajan S, Li S, Liu W, Li M, Han A, Tang J, Hu B, Yusuf S, Li W; PURE-China Investigators. Socioeconomic disparity in mortality and the burden of cardiovascular disease: analysis of the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE)-China cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2023;8:e968-e977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Isaacs-Itua A, Wong S. Stroke rehabilitation and recovery. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2021;82:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Oral A. Are implementation interventions effective in promoting the adoption of evidence-based practices in stroke rehabilitation? A Cochrane Review summary with commentary. NeuroRehabilitation. 2022;50:255-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Afridi A, Malik AN, Rathore FA. Task Oriented Training For Stroke Rehabilitation: A Mini Review. J Pak Med Assoc. 2023;73:2295-2297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Boyne P, Billinger SA, Reisman DS, Awosika OO, Buckley S, Burson J, Carl D, DeLange M, Doren S, Earnest M, Gerson M, Henry M, Horning A, Khoury JC, Kissela BM, Laughlin A, McCartney K, McQuaid T, Miller A, Moores A, Palmer JA, Sucharew H, Thompson ED, Wagner E, Ward J, Wasik EP, Whitaker AA, Wright H, Dunning K. Optimal Intensity and Duration of Walking Rehabilitation in Patients With Chronic Stroke: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2023;80:342-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hao M, Fang Q, Wu B, Liu L, Tang H, Tian F, Chen L, Kong D, Li J. Rehabilitation effect of intelligent rehabilitation training system on hemiplegic limb spasms after stroke. Open Life Sci. 2023;18:20220724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | O'Neill CD, Vidal-Almela S, Terada T, Kamiya K, Tulloch HE, Pipe AL, Reed JL. Sex and Age Differences in Anxiety and Depression Levels Before and After Aerobic Interval Training in Cardiac Rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2022;42:15-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cheng C, Liu X, Fan W, Bai X, Liu Z. Comprehensive Rehabilitation Training Decreases Cognitive Impairment, Anxiety, and Depression in Poststroke Patients: A Randomized, Controlled Study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27:2613-2622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shirdel Z, Behzad I, Manafi B, Sahebi M. The Effect of Home Care Training on Anxiety and Vital Signs Levels in Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Perianesth Nurs. 2021;36:393-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xiao M, Huang G, Feng L, Luan X, Wang Q, Ren W, Chen S, He J. Impact of sleep quality on post-stroke anxiety in stroke patients. Brain Behav. 2020;10:e01716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lee JH, Kim EJ. The Effect of Diagonal Exercise Training for Neurorehabilitation on Functional Activity in Stroke Patients: A Pilot Study. Brain Sci. 2023;13:799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shih PC, Steele CJ, Hoepfel D, Muffel T, Villringer A, Sehm B. The impact of lesion side on bilateral upper limb coordination after stroke. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2023;20:166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Barkas F, Anastasiou G, Liamis G, Milionis H. A step-by-step guide for the diagnosis and management of hyponatraemia in patients with stroke. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2023;14:20420188231163806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Campo-Arias A, Blanco-Ortega JD, Pedrozo-Pupo JC. Brief Spanish Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale: Dimensionality, Internal Consistency, Nomological Validity, and Differential Item Functioning Among Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients in Colombia. J Nurs Meas. 2022;30:407-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Broderick JP, Adeoye O, Elm J. Evolution of the Modified Rankin Scale and Its Use in Future Stroke Trials. Stroke. 2017;48:2007-2012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 574] [Article Influence: 63.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Benbow R. Multidimensional Self-Efficacy Scale for Exercise. Home Healthc Now. 2023;41:228-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kortlever JTP, Tripathi S, Ring D, McDonald J, Smoot B, Laverty D. Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia Short Form and Lower Extremity Specific Limitations. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2020;8:581-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cheng L, Gao W, Xu Y, Yu Z, Wang W, Zhou J, Zang Y. Anxiety and depression in rheumatoid arthritis patients: prevalence, risk factors and consistency between the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Zung's Self-rating Anxiety Scale/Depression Scale. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2023;7:rkad100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sun L, Clarke R, Bennett D, Guo Y, Walters RG, Hill M, Parish S, Millwood IY, Bian Z, Chen Y, Yu C, Lv J, Collins R, Chen J, Peto R, Li L, Chen Z; China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group; International Steering Committee; International Co-ordinating Centre, Oxford; National Co-ordinating Centre, Beijing; Regional Co-ordinating Centres. Causal associations of blood lipids with risk of ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage in Chinese adults. Nat Med. 2019;25:569-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 35.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wang J. Application Prospects of Specific Rehabilitation Task Training in Upper Limb Function Rehabilitation of Stroke Sequelae Patients. Altern Ther Health Med. 2024;AT10286. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Herring MP, Meyer JD. Resistance exercise for anxiety and depression: efficacy and plausible mechanisms. Trends Mol Med. 2024;30:204-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chen YC, Chen C, Martínez RM, Etnier JL, Cheng Y. Habitual physical activity mediates the acute exercise-induced modulation of anxiety-related amygdala functional connectivity. Sci Rep. 2019;9:19787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sütçü Uçmak G, Kılınç M. The effects of kinesiophobia, fatigue, and quality of life on physical activity in patients with stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2024;31:788-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Anderson E, Shivakumar G. Effects of exercise and physical activity on anxiety. Front Psychiatry. 2013;4:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kandola A, Stubbs B. Exercise and Anxiety. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1228:345-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Farris SG, Abrantes AM, Bond DS, Stabile LM, Wu WC. Anxiety and Fear of Exercise in Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation: PATIENT AND PRACTITIONER PERSPECTIVES. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2019;39:E9-E13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kraemer KM, Carroll AJ, Clair M, Richards L, Serber ER. The role of anxiety sensitivity in exercise tolerance and anxiety and depressive symptoms among individuals seeking treatment in cardiopulmonary rehabilitation. Psychol Health Med. 2021;26:1100-1107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Picha KJ, Lester M, Heebner NR, Abt JP, Usher EL, Capilouto G, Uhl TL. The Self-Efficacy for Home Exercise Programs Scale: Development and Psychometric Properties. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2019;49:647-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Chen X, Yang X, Li Y, Zhang X, Zhu Y, Du L, Cai J, Xu X. Influencing factors of kinesiophobia among stroke patients with hemiplegia: A mixed methods study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2024;240:108254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Bąk E, Młynarska A, Marcisz C, Kadłubowska M, Marcisz-Dyla E, Sternal D, Młynarski R, Krzemińska S. Kinesiophobia in Elderly Polish Patients After Ischemic Stroke, Including Frailty Syndrome. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2022;18:707-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bermudez T, Bierbauer W, Scholz U, Hermann M. Depression and anxiety in cardiac rehabilitation: differential associations with changes in exercise capacity and quality of life. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2022;35:204-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chlapecka A, Wolfová K, Fryčová B, Cermakova P. Educational attainment and anxiety in middle-aged and older Europeans. Sci Rep. 2023;13:13314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Samudio-Cruz MA, Toussaint-González P, Estrada-Cortés B, Martínez-Cortéz JA, Rodríguez-Barragán MA, Hernández-Arenas C, Quinzaños-Fresnedo J, Carrillo-Mora P. Education Level Modulates the Presence of Poststroke Depression and Anxiety, But It Depends on Age. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2023;211:585-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Zhang M, Zhang W, Liu Y, Wu M, Zhou J, Mao Z. Relationship between Family Function, Anxiety, and Quality of Life for Older Adults with Hypertension in Low-Income Communities. Int J Hypertens. 2021;2021:5547190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Sun Y, Liu C, Zhang N, Yang D, Ma J, Ma C, Zhang X. Effect of self-management of stroke patients on rehabilitation based on patient-reported outcome. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:929646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/