Published online Feb 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.108614

Revised: July 30, 2025

Accepted: November 11, 2025

Published online: February 19, 2026

Processing time: 219 Days and 23.2 Hours

Superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is a common skin cancer for which surgical treatment is currently the primary clinical approach. However, due to the large surgical incision, noticeable scarring can easily occur postoperatively, affecting the patient’s facial aesthetics. As such, providing appropriate nursing support during the perioperative period is essential.

To investigate the impact of psychological nursing on anxiety, depression, wound healing rates, and satisfaction in patients with superficial BCC.

Clinical data from 87 patients with superficial facial BCC, who were treated at the Central Hospital of Enshi Prefecture Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture be

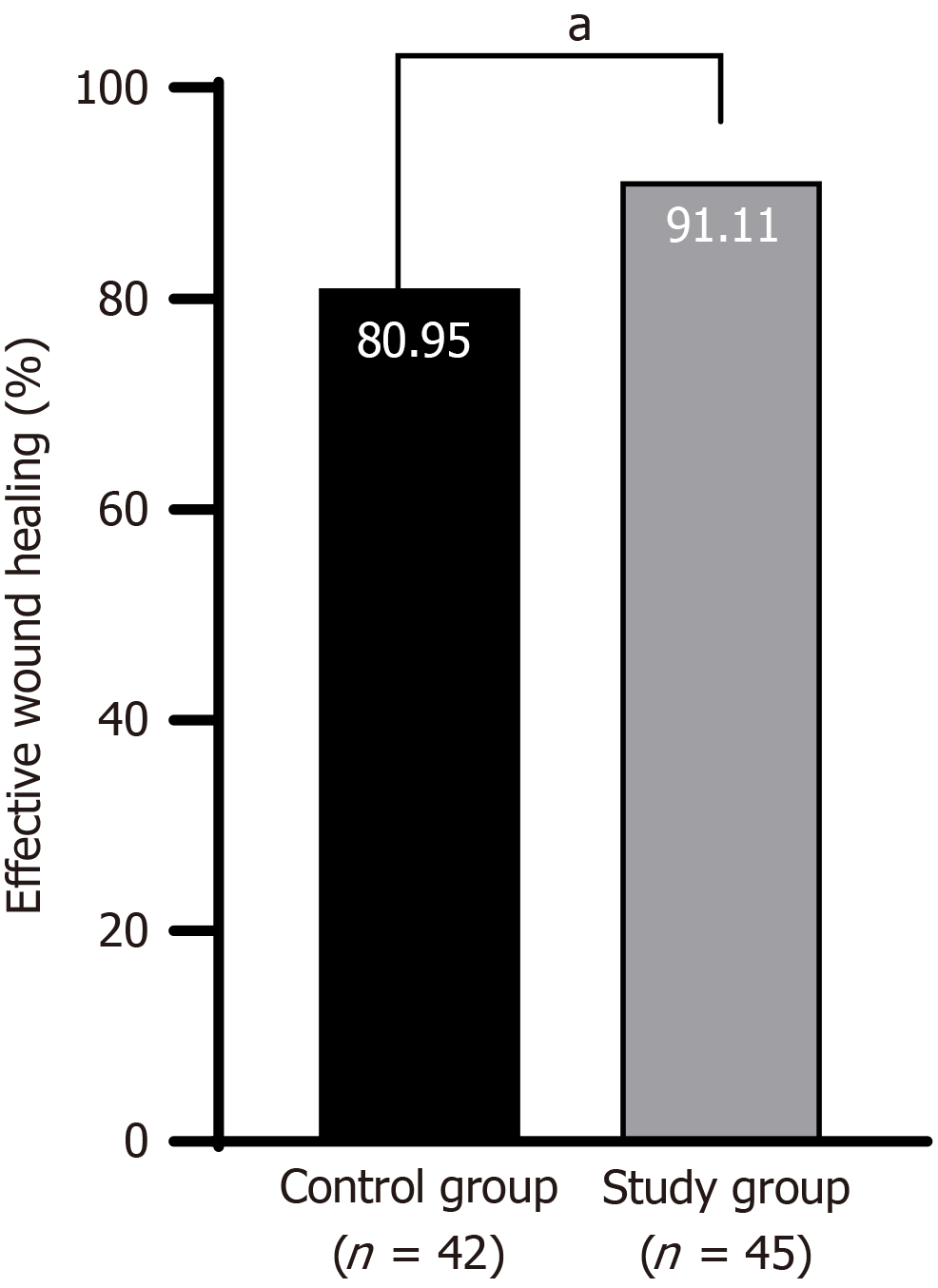

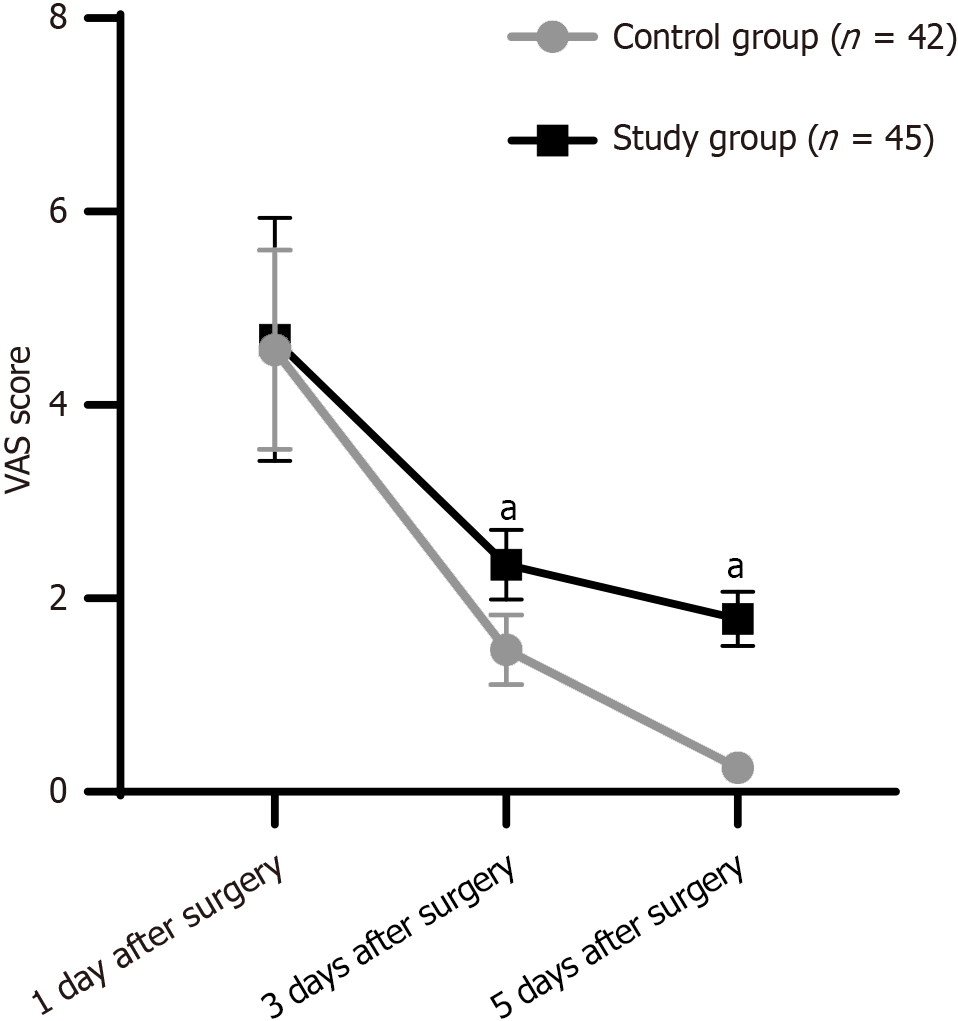

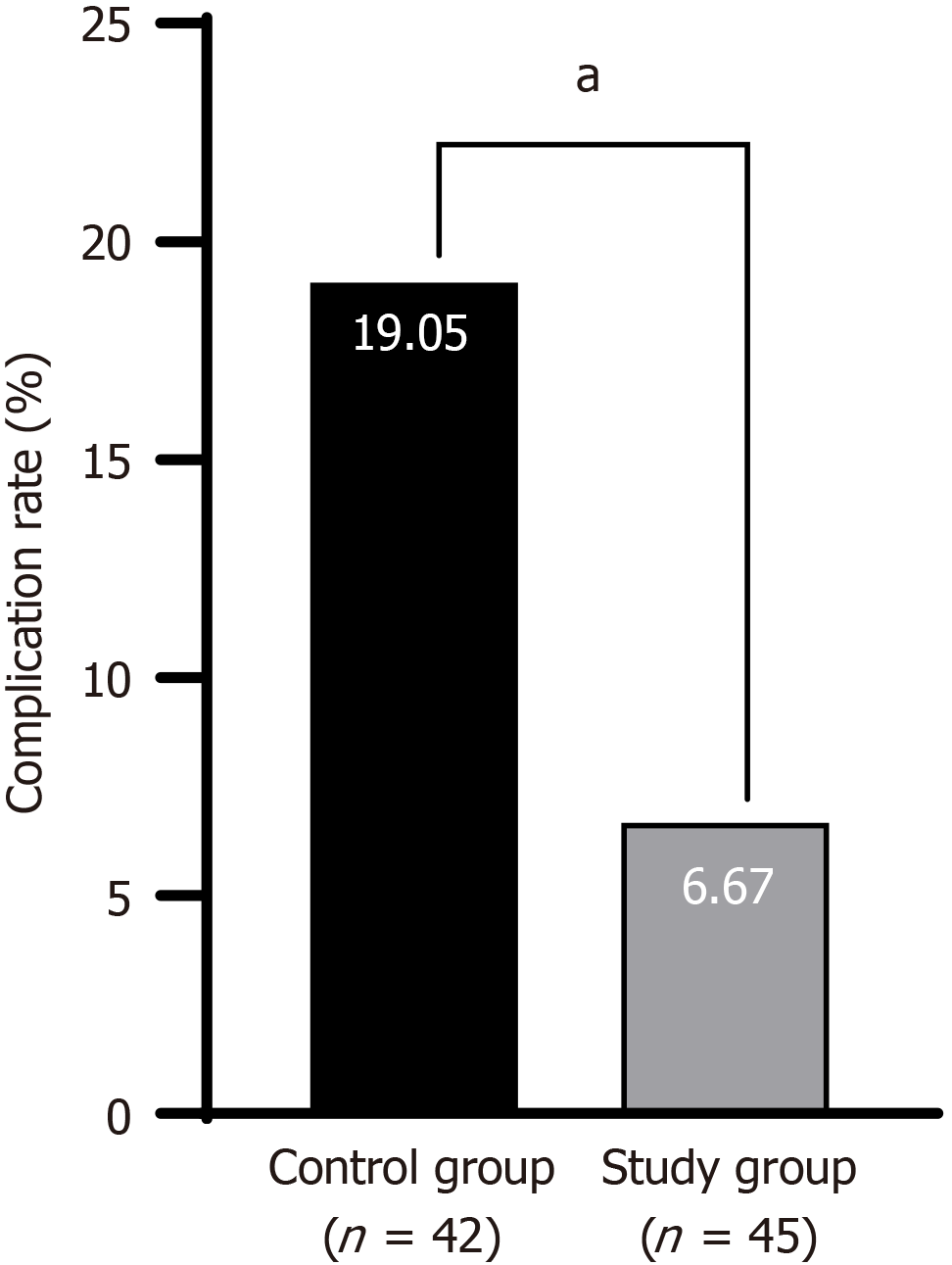

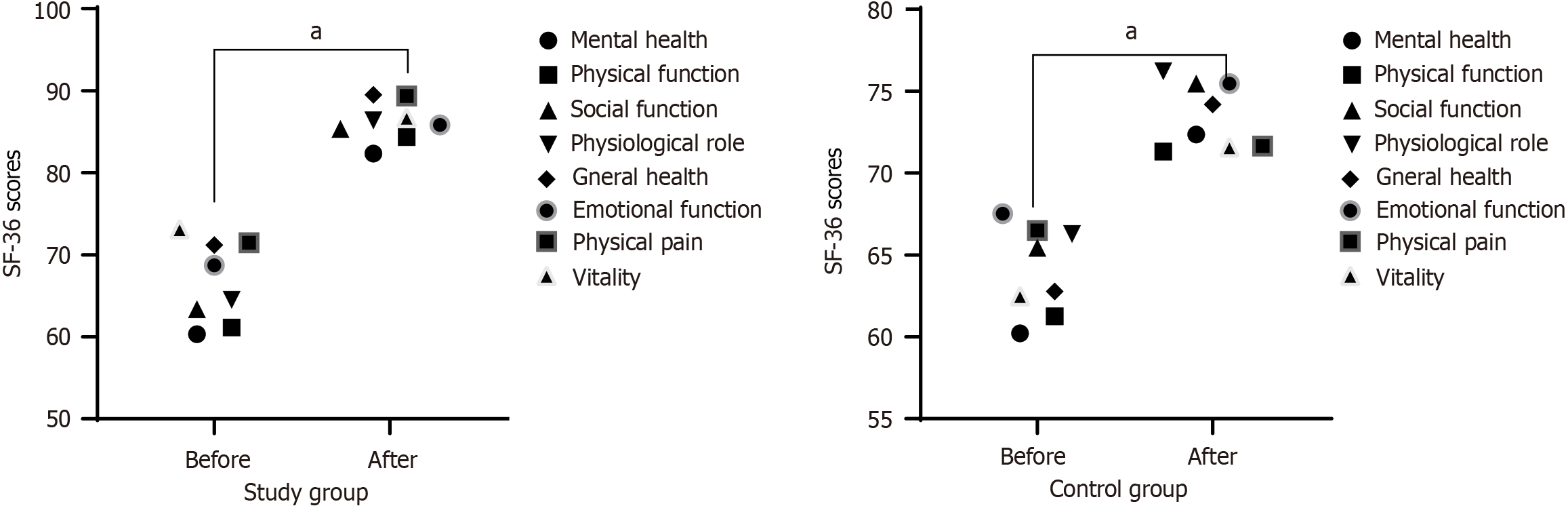

After the nursing intervention, the study group exhibited significantly lower Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Scale scores than the control group (P < 0.05). The wound healing rate in the intervention group (91.11%) was significantly higher than that in the control group (80.95%) (P < 0.05), and the visual analog scale score was lower in the intervention group (P < 0.05). The total incidence of complications in the intervention group (6.67%) was lower than that in the control group (19.05%) (P < 0.05). Postoperative quality of life and satisfaction with nursing were higher in the intervention group (P < 0.05).

Psychological nursing intervention(s) effectively alleviated negative emotions, promoted wound healing, reduced pain, improved satisfaction, and reduced postoperative complications in patients with superficial facial BCC.

Core Tip: This study investigated the impact of psychological nursing care on anxiety, depression, wound-healing rates, and satisfaction with nursing in patients diagnosed with superficial basal cell carcinoma. After the nursing intervention, the study group exhibited significantly lower Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Scale scores than the control group (P < 0.05), a better wound healing rate (91.11% vs 80.95%) (P < 0.05), a lower visual analog scale score (P < 0.05), a lower incidence of complications (6.67% vs 19.05%) (P < 0.05), and better postoperative quality of life and satisfaction with nursing (P < 0.05). These results support the effectiveness of psychological nursing care in patients with superficial facial basal cell carcinoma.

- Citation: Zhu J, Zhu YH, Yang Y. Impact of psychological nursing on anxiety, depression, wound healing, and satisfaction in patients with superficial basal cell carcinoma. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(2): 108614

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i2/108614.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.108614

Non-melanoma skin cancer results from the abnormal proliferation of skin cells caused by DNA mutations or genetic defects[1]. Malignant melanoma is the leading cause of skin cancer-related death and its incidence is increasing faster than that of other types of cancer[2,3]. Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common type of malignancy within the non-melanoma skin cancer category, representing approximately 80% of these tumors globally, with an annual incidence of almost 10%[4,5]. Originating from keratinocytes, BCCs are commonly localized skin cancers with low malignancy rates[6]. BCC typically occurs in areas exposed to ultraviolet radiation, particularly the head and face, and can severely affect an individual’s appearance[7,8].

BCC is generally associated with good prognosis. Although the mortality rate associated with BCC is low, it can easily cause local tissue damage, leading to a high probability of disfigurement[9]. Surgical excision is the preferred treatment for BCC affecting the head and face[10]. BCC commonly occurs in areas exposed to ultraviolet radiation, such as the perioral region, eyelids, and nose[11]. Patients with lesions in these specific areas often have high functional and aesthetic needs[12]. Mohs micrographic surgery can ensure complete tumor removal with minimal tissue damage; however, it is difficult to implement widely in primary hospitals because of its complexity, length of the procedure(s), need for intraoperative frozen section capabilities, and close collaboration with pathologists[13]. As such, standard surgical excision is the most widely used procedure[14,15]. Although surgery can remove tumors to a greater extent, surgery performed on the face inevitably removes some tissue, often leaving visible scars. Patients usually have a longer life expectancy due to the low malignancy of BCC; however, these permanent scars can be a burden on the patient and lead to long-term suffering. Routine nursing measures lack comprehensive content, fail to emphasize the psychological needs of patients and the importance of facial aesthetics, and may threaten other organs and tissues as the disease progresses and worsens[16]. This causes great psychological distress because anxiety and depression in patients with BCC are not only due to concerns about the disease itself, but also long-term social integration, self-image, and quality of life, which can persist even after wound healing. Psychological care interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and supportive counseling, aim to alleviate persistent psychological issues by addressing social inclusion fears and improving self-image perception, which are extremely important for the mental health of those diagnosed with BCC. To minimize functional deficits and maximize aesthetic appearance, standard surgical excision aims to preserve key adjacent tissues and organ structures; however, this can lead to the development of residual tumors[17]. Although postoperative psychological nursing interventions have yielded positive effects in patients with other cancers, their effect on wound healing and satisfaction with nursing in patients diagnosed with BCC remains unclear.

As such, the present study investigated the impact of psychological nursing on anxiety, depression, incision healing, and satisfaction with nursing in patients with superficial BCC to provide evidence supporting the development of nursing care strategies.

Clinical data from 87 patients diagnosed with superficial facial BCC, who were treated at the Central Hospital of Enshi Prefecture, Tujia, and Miao Autonomous Prefecture between February 2023 and February 2025, were retrospectively analyzed. Patients were divided into 2 groups according to type of nursing care: Control (routine nursing care, n = 42); and intervention (psychological nursing in addition to routine nursing care, n = 45).

The inclusion criteria were diagnosis of superficial BCC of the face, surgical treatment, and availability of complete clinical data. The exclusion criteria were concurrent keratoacanthoma, melanoma, nevus, seborrheic keratosis, pregnancy or breastfeeding, current HIV disease, and recent treatment with immunomodulatory drugs.

Data were retrospectively collected from the hospital’s electronic medical records system and nursing documentation. The collected information included the following: Demographic and clinical characteristics (age, gender, lesion location, tumor size, disease duration, and surgical details); nursing intervention records (type, frequency, and duration of psychological nursing measures in the intervention group; details of routine nursing in both groups); outcome measures data [Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A), Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D), visual analog scale (VAS) and 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) score], and a questionnaire addressing satisfaction with nursing; wound healing status; and occurrence of postoperative complications at baseline (preoperatively), 1 week postoperatively, and 1 month post-discharge. Two trained research nurses independently extracted the data; any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a senior researcher.

Given the retrospective design of the present study and the use of anonymized patient data, the requirement for informed consent was waived by the hospital ethics committee, approval No. LL20240149. To ensure patient privacy, all data were processed and stored in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and local data-protection regulations.

Control group: Routine nursing measures were administered until discharge, with a 1-month follow-up after discharge: (1) Preoperative examination: The patient’s facial skin condition was tested and vital signs were closely monitored. Each patient was comprehensively assessed to determine whether the surgical criteria were fulfilled; (2) Health education: Proactive communication and interaction with patients, and clear education about relevant precautions during surgery and the postoperative recovery period; (3) Preoperative preparation: Preparation for disinfection, draping, and anes

Intervention group: The study group received psychological nursing based on routine nursing until discharge, with a 1-month follow-up after discharge.; (1) Preoperative nursing: After admission, the ulcerated area was cleaned using a 0.9% sodium chloride solution, and a wet dressing with ethacridine lactate solution was applied locally. The area of the tumor lesion was banded (local treatment); (2) Preoperative preparation: One to 3 days before the operation, nursing staff removed hair from the affected area and cleaned the underlying skin. If skin grafting was required, the routine donor site, either the abdomen or the inner thigh, was prepared and cleaned simultaneously; (3) Preoperative examination: In addition to testing the patient’s facial skin condition, instructions were provided to complete routine blood and urine tests and electrocardiograms to avoid errors in preliminary examination results that could affect the surgical outcome; and (4) Psychological counseling: Most patients lack an understanding of their own disease and medical procedures, and are prone to negative emotions such as fear, apprehension, or anxiety when facing surgical treatment. As such, nursing staff provided health education through appropriate communication and easily understandable language to help patients fully understand surgery-related matters and reduce psychological stress. This included individual counseling sessions (20-30 minutes per session, 2-3 times preoperatively) and the provision of educational materials. Nurses used active listening techniques to identify patients’ specific concerns (regarding scarring and social acceptance) and addressed them using evidence-based information.

Intraoperative nursing: Nursing staff assisted physicians in performing skin flap transplantation surgery, strengthened patient vital sign monitoring during the operation, and placed a urinary catheter depending on operative duration: (1) Body position intervention: For 24 hours postoperatively, the nursing staff instructed patients to maintain absolute bed rest, adjust to a healthy lateral or supine position, and elevate the head of the bed by approximately 30° to relieve dis

Within 3 days after surgery, the nursing staff conducted daily follow-up conversations (15-20 minutes each) to assess patients’ emotional states, provided positive feedback on wound healing progress, and addressed concerns regarding scarring and appearance. For patients with persistent anxiety or depression (HAM-A score > 14 or HAM-D score > 17), additional counseling sessions (twice weekly) were conducted in collaboration with a clinical psychologist.

Psychological status[18,19]: The HAM-A includes 14 items rated from 0 to 4, on which higher scores signify greater anxiety. The HAM-D consists of 17 items with a hierarchical scoring method. Items 1, 2, 3, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 15, and 17 are scored from 0 to 4, whereas items 4, 5, 6, 12, 13, 14, and 16 are rated from 0 to 2. Higher total HAM-D scores indicate more severe depression. HAM-D score ≤ 7, non-depression; HAM-D score 8-17, mild depression; no anxiety: HAM-A score ≤ 7; mild anxiety: HAM-A score 8-14; moderate anxiety: HAM-A score 15-23; and severe anxiety: HAM-A score ≥ 24. HAM-D score 18-24, moderate depression; HAM-D score > 24, severe depression.

Wound healing efficiency: Wound healing was classified into the following categories: Complete recovery (full healing with the scab falling off), significant effect (wound reduced in size but not fully healed, no secretions with healthy granulation), effective effect (decreased secretion and exudate without noticeable enlargement), and ineffective effect (poor healing with pale granulation). Healing efficiency was calculated using the following equation: (Number of significant and effective wounds/total number of wounds) × 100.

VAS score[20]: A VAS was used to evaluate pain levels in the 2 groups. Patients marked their pain on a 10 cm line, with 0 representing no pain and 10 representing the worst pain imaginable.

Postoperative complications: This includes statistics regarding the occurrence of postoperative issues such as incision infections, bleeding, redness and swelling, and blood seepage in the surgical area.

Quality of life[21]: The SF-36 assessed 8 health domains: Physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health. The validated Dutch version of the Medical Outcomes Study SF-36, with a reference timeframe of the past week, was used. Each domain score was computed if 50% of the questions were answered. All scores were linearly converted to a scale of 0-100, with higher scores reflecting better health status.

Satisfaction with nursing was assessed using a tailored questionnaire that focused on the following 5 aspects: Basic care, nursing knowledge, attitude, skills, and skin care. Satisfaction was reported as a percentage (0%-100%), with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction. The thresholds for interpretation were as follows: Scores < 60% indicated dissatisfaction; 60%-80% indicated satisfaction, and scores > 80% indicated high satisfaction. The overall satisfaction rate was calculated as follows: (Very satisfied + satisfied)/total number of cases × 100.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Quantitative data with normal distribution are expressed as mean ± SD, and comparisons between the intervention and control groups were performed using the t-test and Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data are reported as frequency and percentage, with comparisons made using the χ² test for four-grid tables or row × list formats. Differences with P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Data from 87 patients were divided into 2 groups: Intervention (n = 45, 55.56% male, 44.4% female); and control (n = 42, 57.14% male, 42.86% female). The mean ± SD ages of the study and control groups were 65.3 ± 11.2 years and 64.9 ± 10.8 years, respectively. Skin phototype III was predominant in both the intervention (46.67%) and control (47.62%) groups. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in terms of sex, age, skin phototype, sun exposure, or lesion location (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

| Patients | Study group (n = 45) | Control group (n = 42) | P value |

| Gender | - | 0.139 | - |

| Male | 25 (55.56) | 24 (57.14) | - |

| Female | 20 (44.44) | 18 (42.86) | - |

| Age (year), mean ± SD | 65.3 ± 11.2 | 64.9 ± 10.8 | 0.715 |

| Phototype | - | 0.381 | - |

| I | 5 (11.11) | 6 (14.29) | - |

| II | 4 (8.89) | 4 (9.52) | - |

| III | 21 (46.67) | 20 (47.62) | - |

| IV | 15 (33.33) | 12 (28.57) | - |

| Maximal diameter (cm), mean ± SD | 1.56 ± 0.82 | 1.59 ± 0.85 | 0.374 |

| Regarding sun exposure | 0.458 | ||

| Sun exposed patients | 30 (66.67) | 27 (64.29) | |

| Not sun exposed patients | 15 (33.33) | 15 (35.71) | |

| Sites of the lesions | 0.683 | ||

| Nose | 18 (36.0) | 15 (33.33) | |

| Scalp | 12 (24.0) | 11 (24.44) | |

| Ear | 10 (20.0) | 8 (17.78) | |

| Forehead | 8 (16.0) | 6 (13.33) | |

| Medial canthus | 2 (4.0) | 5 (11.11) | |

Before implementation of the nursing interventions, there were no statistically significant differences between the 2 groups in terms of HAM-A scores (study group: 22.78 ± 2.43; control group: 21.96 ± 2.02) and HAM-D scores (intervention group: 21.93 ± 1.57; control group: 22.74 ± 1.75) (P > 0.05). However, after the intervention, both groups exhibited significant reductions in HAM-A and HAM-D scores compared with pre-nursing levels, with the intervention group exhibiting significantly lower scores than the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

| Index | Control group (n = 42) | Study group (n = 45) | P value |

| HAM-A | 16.32 ± 2.79 | 10.16 ± 3.05 | < 0.001 |

| HAM-D | 16.96 ± 3.18 | 12.35 ± 2.63 | < 0.001 |

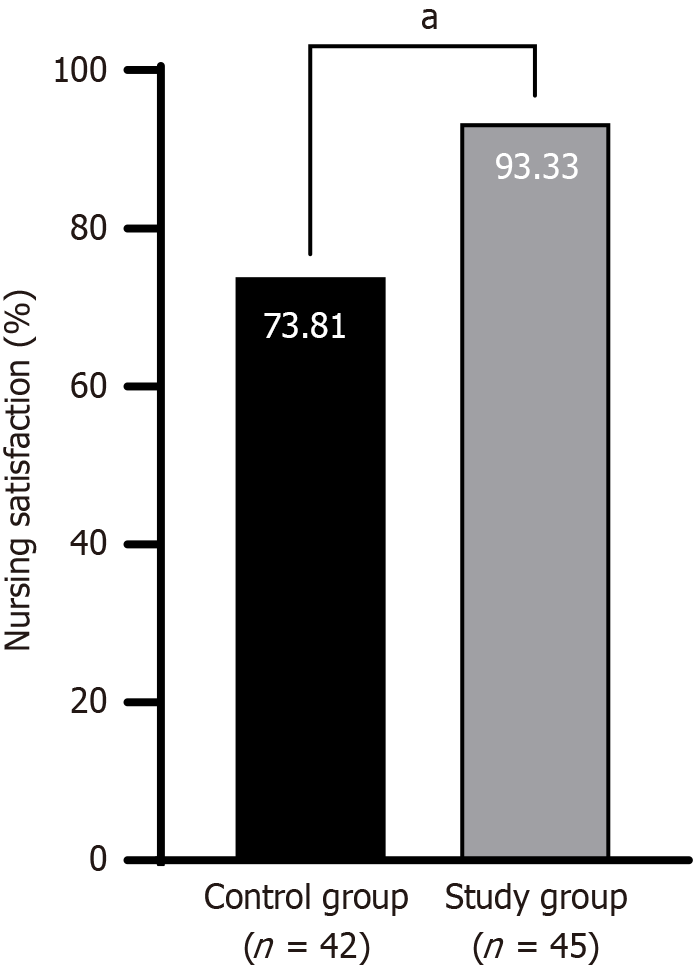

After 4 weeks of nursing intervention, wound healing efficiency in the intervention group was 91.11% (41/45) compared with 80.95% (34/42) in the control group, and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Figure 1).

Mean VAS scores for the intervention group were 4.57 ± 1.03, 1.47 ± 0.36, and 0.25 ± 0.13, measured at 1 days, 3 days, and 5 days postoperatively, respectively. In contrast, the control group reported respective mean VAS scores of 4.68 ± 1.26, 2.35 ± 0.36, and 1.79 ± 0.28. Differences in VAS scores between the 2 groups were statistically significant (P < 0.001) (Figure 2).

The complication rate in the intervention group was 6.67% (3/45), which was significantly lower than that in the control group (19.05%, 8/42) (P < 0.001) (Figure 3).

There were no statistically significant differences in SF-36 scores between the 2 groups before care (P > 0.05). However, the post-intervention SF-36 score was significantly higher in the intervention group than that in the control group (P < 0.05) (Figure 4).

Patient satisfaction with nursing care was 93.33% (42/45) in the study group, which was markedly higher than that in the control group (73.81%, 31/42) (P < 0.05) (Figure 5). Representative cases are presented in Figure 6.

Superficial BCC of the face is a common skin malignancy characterized by the presence of stroma-dependent pluripotent basal-like cells. It is a low-grade malignant tumor that differentiates into the epidermis or appendages, and is primarily derived from primitive epithelial germ cells[22]. In recent years, the diagnostic rate of facial BCC has improved with the continuous progress in medical technology in China. After disease onset, the skin tissues of the patients contain various cytokines[23]. Changes in cell expression and interactions between cells lead to abnormal cell proliferation, gradually decreasing apoptosis rates and, in severe cases, even local soft tissue damage[24]. Although surgical treatment has the most profound effects, surgical resection can cause defects in the face and nose, directly impacting facial aesthetics[25]. Therefore, scientifically based and rational nursing interventions are crucial for improving skin lesions in patients with BCC.

Results of the present study revealed that the total incidence of complications in the intervention group was lower than that in the control group (P < 0.05), suggesting that psychological nursing can effectively prevent postoperative complications. This may be because the content of routine nursing includes vital sign monitoring, dietary interventions, and medication guidance. Although these can meet the basic nursing needs of patients, the auxiliary effects of surgical treatment(s) are not always ideal. Psychological nursing standardizes the nursing process by providing psychological care before, during, and after surgery, thereby improving the overall quality of nursing services. It comprehensively considers the patients’ cognitive, medication, dietary, pain, and psychological nursing needs and the timely adjustment of their physical and mental state, which can ensure the smooth progress of surgery and improve treatment safety, thus having an ideal preventive effect on postoperative complications. This finding is consistent with those reported in previous studies[26,27]. Studies have indicated that active participation in health management is closely associated with increased satisfaction with recovery outcomes and reduced functional limitations[28]. This engagement extends beyond physical health maintenance to include effective emotional and social functioning, which collectively contributes to comprehensive patient rehabilitation. In cancer care, the integration of psychological and social factors is essential for high-quality nursing. Psychological interventions can significantly improve patient quality of life, reduce emotional distress, and enhance adherence[29].

Results of this study revealed statistically lower HAM-A and HAM-D scores in the intervention group than those in the control group (P < 0.05), demonstrating that the intervention group achieved significantly better therapeutic outcomes in alleviating anxiety and depression than the control group. The wound healing rate in the intervention group (91.11%) was significantly higher than that in the control group (80.95%) (P < 0.05), and lower than that in the control group (P < 0.05). Postoperative quality of life and satisfaction with nursing were higher in the intervention group than in the control group (P < 0.05). This finding is consistent with those of the previous studies[30]. For example, one study investigating the impact of high-quality nursing combined with psychological interventions on stress responses and negative postoperative emotions in patients undergoing surgery under general anesthesia reported that patients who received psychological interventions demonstrated significant improvements in postoperative stress indicators, anxiety levels, and depression scores[31]. Similarly, another study revealed that psychological care interventions effectively alleviated anxiety and depression in patients with rectal cancer undergoing postoperative chemotherapy, and enhanced treatment compliance and immune function, thereby promoting recovery[32]. This may be because psychological nursing has stronger humanistic characteristics than routine nursing. Improving preoperative preparation, providing rehabilitation guidance, and focusing on adjusting patient psychological state can help meet their physiological and psychological needs, thereby alleviating negative emotions.

Psychological nursing is crucial for patients with superficial facial BCC because of the aesthetic sensitivity of the area affected by disease. Because patients often worry about the effects of postoperative recovery, some experience adverse psychological events, such as anxiety, worry, and insomnia, which makes appropriate nursing care so crucial in these cases. Forming a good nurse-patient relationship between the nursing staff and patient, enabling the patient to feel warm psychologically, and developing a sense of dependence on the nursing staff are the foundations of successful psychological nursing. If a patient experiences postoperative discomfort, the nursing staff should take timely measures to help the patient address the problem and inform them that surgical recovery requires a process to reduce psychological issues during the image disturbance period.

Reducing anxiety and depression through psychological intervention(s) effectively decreases cortisol secretion, improves neuroinflammatory interactions, and reduces oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, thereby accelerating wound healing. Understanding this mechanism provides a theoretical foundation for developing new therapeutic strategies, and underscores the importance of psychological care in clinical practice[33-35].

The present study had some limitations. The first was its retrospective design, which may have introduced selection bias with potential differences in patients’ clinical characteristics and baseline data. Although the patients were randomly divided into control and intervention groups, the relatively small sample size may limit the broad applicability and generalizability of the results. Future prospective randomized controlled designs will be used to reduce bias and expand the sample size through multicenter collaboration. Second, the implementation methods and intervention intensity of psychological nursing may vary among patients, which may have affected the evaluation of intervention effects. In addition, the effect of psychological nursing may vary according to patients’ subjective feelings; however, this study mainly relied on scale evaluation and did not fully consider qualitative data. Future large-scale prospective studies are needed to comprehensively evaluate the effects of psychological nursing on this patient population to optimize nursing practices. Therefore, in future clinical practice, group psychoeducation can be led by standardized trained nurses, and research can be promoted from 4 aspects. First, randomized controlled trials and blinded outcome assessments should be implemented to reduce bias. Second, depending on patient age, baseline anxiety level, and other characteristics, a personalized intervention plan should be developed through an adaptive design. Third, biological markers, such as cortisol and inflammatory cytokines, should be introduced to quantify the physiological effects of psychological care. Fourth, a cost-benefit analysis should be performed to clarify the economic value of the intervention promote its application in resource-constrained environments.

In summary, psychological nursing interventions can effectively mitigate negative emotions in patients diagnosed with superficial facial BCC, promote wound healing, reduce pain, improve satisfaction with nursing, and reduce postoperative complications. In the treatment and nursing process, various psychological characteristics of patients should be considered to provide the most appropriate psychological support and guidance, establish a good nurse-patient relationship, and provide patients with a comfortable ward environment, thereby strengthening the nursing effect.

| 1. | Słowińska M, Czarnecka I, Czarnecki R, Tatara P, Nasierowska-Guttmejer A, Lorent M, Kania J, Owczarek W. Characteristics of patients with melanoma with nonmelanoma skin cancer comorbidity: Practical implications based on a retrospective study. Oncol Lett. 2025;29:214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Micha JP, Bohart RD, Goldstein BH. A review of sunscreen in the prevention of skin cancer. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2025;31:1145-1149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang T, Wu Z, Bi Y, Wang Y, Zhao C, Sun H, Wu Z, Tan Z, Zhang H, Wei H, Yan W. PARVB promotes malignant melanoma progression and is enhanced by hypoxic conditions. Transl Oncol. 2024;42:101861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | El-Ammari S, Elloudi S, Baybay H, Soughi M, Douhi Z, Mernissi FZ, Omari M, El Fakir S, Tahiri L. Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Clinico-Dermoscopic and Histological Correlation: About 72 Cases. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2024;14:e2024042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zambrano-Román M, Padilla-Gutiérrez JR, Valle Y, Muñoz-Valle JF, Guevara-Gutiérrez E, Martínez-Fernández DE, Valdés-Alvarado E. PTCH1 gene variants rs357564, rs2236405, rs2297086 and rs41313327, mRNA and tissue expression in basal cell carcinoma patients from Western Mexico. J Clin Lab Anal. 2024;38:e25010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kgokolo MCM, Malinga NZ, Steel HC, Meyer PWA, Smit T, Anderson R, Rapoport BL. Transforming growth factor-β1 and soluble co-inhibitory immune checkpoints as putative drivers of immune suppression in patients with basal cell carcinoma. Transl Oncol. 2024;42:101867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Slominski AT, Slominski RM, Raman C, Chen JY, Athar M, Elmets C. Neuroendocrine signaling in the skin with a special focus on the epidermal neuropeptides. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2022;323:C1757-C1776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 8. | Godinho D, Ferreira C, Lourenço A, de Oliveira Araújo S, Quilhó T, Diamantino TC, Gominho J. The behavior of thermally modified wood after exposure in maritime/industrial and urban environments. Heliyon. 2024;10:e25020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Usatine RP, Heath CR. Basal Cell Carcinoma. Cutis. 2022;109:339-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Heath MS, Bar A. Basal Cell Carcinoma. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:13-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kaur H, de Mesy Bentley KL, Rahman SM, Cohen PR, Smoller BR. Cutaneous Superficial Basal Cell Carcinoma is a Basal Cell Carcinoma In Situ: Electron Microscopy of a Case Series of Basal Cell Carcinomas. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024;14:1359-1366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cohen PR. Superficial Basal Cell Carcinoma of the Skin Is a Cutaneous Basal Cell Carcinoma In Situ. Skinmed. 2024;22:165-167. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Chen Yin Lua A, Ai Qun Oh D, See Tow HX, Por RH, Yi Koh H, Chiat Oh C. Mohs micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinoma in Singapore: A retrospective review. JAAD Int. 2024;17:167-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Meretsky CR, Schiuma AT. Comparative Analysis of Slow Mohs Surgery in Melanoma and Mohs Micrographic Surgery in Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Basal Cell Carcinoma. Cureus. 2024;16:e59693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Brown AC, Brindley L, Hunt WTN, Earp EM, Veitch D, Mortimer NJ, Salmon PJM, Wernham A. A review of the evidence for Mohs micrographic surgery. Part 2: basal cell carcinoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:1794-1804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Work Group; Invited Reviewers, Kim JYS, Kozlow JH, Mittal B, Moyer J, Olencki T, Rodgers P. Guidelines of care for the management of basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:540-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 38.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Amici JM. Prise en charge chirurgicale du carcinome basocellulaire: Surgical management of basal cell carcinoma. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2018;145 Suppl 5:VS12-VS29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6169] [Cited by in RCA: 7038] [Article Influence: 105.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21041] [Cited by in RCA: 23402] [Article Influence: 354.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 20. | Liu M, Zhang D, Shi B. Comparison of the Post-Total Knee Arthroplasty Analgesic Effect of Intraoperative Periarticular Injection of Different Analgesics. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2019;29:1169-1172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, O'Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Usherwood T, Westlake L. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 1992;305:160-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2852] [Cited by in RCA: 3371] [Article Influence: 99.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | García Ruiz R, Mateu Puchades A, Alegre de Miquel V. [Translated article] Basal Cell Carcinoma: Incidence and Trends in Valencia, Spain. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2024;115:T943-T947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Khalil AA, Enezei HH, Aldelaimi TN, Mohammed KA. Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment of Basal Cell Carcinoma. J Craniofac Surg. 2024;35:e204-e208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Cutaneous Basal Cell Carcinoma In Situ: A Review of the World Literature. Cureus. 2024;16:e69691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lam MW, Wells H, Zhao A, Gibbs H, Tso S, Wernham A. Natural progression of basal cell carcinomas in patients awaiting surgical intervention. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2025;50:632-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yang X, Yin D, Chen SQ. Effect of nursing on postoperative respiratory function and mental health of lung cancer patients. World J Clin Cases. 2024;12:922-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Raheel MFS, Snoubar Y, Mosbah WS. Being female with vitiligo disease in traditional societies within North Africa. Biopsychosoc Med. 2024;18:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jayakumar P, Teunis T, Vranceanu AM, Williams M, Lamb S, Ring D, Gwilym S. The impact of a patient's engagement in their health on the magnitude of limitations and experience following upper limb fractures. Bone Joint J. 2020;102-B:42-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Grassi L. Psychiatric and psychosocial implications in cancer care: the agenda of psycho-oncology. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zaorsky NG, Zhang Y, Tuanquin L, Bluethmann SM, Park HS, Chinchilli VM. Suicide among cancer patients. Nat Commun. 2019;10:207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 29.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wu G, Shi F, Fu G. Effect of High-quality Nursing Care Combined with Psychological Intervention on Stress Response in Surgery and Postoperative Negative Emotions of Patients Undergoing General Anesthesia. Altern Ther Health Med. 2025;31:176-181. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Sun X, Zhong W, Lu J, Zhuang W. Influence of Psychological Nursing Intervention on Psychological State, Treatment Compliance, and Immune Function of Postoperative Patients with Rectal Cancer. J Oncol. 2021;2021:1071490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Robinson H, Norton S, Jarrett P, Broadbent E. The effects of psychological interventions on wound healing: A systematic review of randomized trials. Br J Health Psychol. 2017;22:805-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Broadbent E, Koschwanez HE. The psychology of wound healing. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25:135-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Basu S, Goswami AG, David LE, Mudge E. Psychological Stress on Wound Healing: A Silent Player in a Complex Background. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2024;23:365-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/