Published online Jan 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i1.113130

Revised: September 9, 2025

Accepted: October 17, 2025

Published online: January 19, 2026

Processing time: 134 Days and 20.8 Hours

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is common among adolescents with depressive disorders and poses a major public health challenge. Rumination, a key cognitive feature of depression, includes different subtypes that may relate to NSSI through distinct psychological mechanisms. However, how these subtypes interact with specific NSSI behaviors remains unclear.

To examine associations between rumination subtypes and specific NSSI beha

We conducted a cross-sectional study with 305 hospitalized adolescents diag

The network analysis revealed close connections between rumination subtypes and NSSI behaviors. Brooding was linked to behaviors such as hitting objects and burning. Scratching emerged as the most influential NSSI symptom. Symptom-focused rumination served as a key bridge connecting rumination and NSSI.

Symptom-focused rumination and scratching were identified as potential inter

Core Tip: For the first time, we applied network analysis to map symptom-level links between rumination subtypes and specific non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) behaviors in adolescents with depressive disorders. Symptom-focused rumination emerged as the most influential bridge connecting cognitive and behavioral symptoms, while self-scratching was the most central NSSI behavior. These findings including: (1) Identify precise cognitive and behavioral targets; and (2) Offer a novel framework for developing tailored interventions that integrate cognitive restructuring with behavioral strategies to reduce NSSI in this vulnerable population.

- Citation: Zhang FF, Guo R, Chen SL, Yang W, Liang XL, Ma MF. Network perspective on rumination and non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents with depressive disorders. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(1): 113130

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i1/113130.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i1.113130

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), defined as the deliberate destruction of one’s own body tissue without suicidal intent, has become a major public health concern among adolescents. Common methods include cutting, hitting, biting, and burning[1]. A global meta-analysis reported a lifetime prevalence of 22% among adolescents[2], consistent with estimates in China (22.38%)[3]. NSSI frequently co-occurs with psychiatric disorders. Among adolescents without formal psychiatric diagnoses, the prevalence ranges from 8% to 25%[4]; however, among those with diagnosed mental disorders, the prevalence is much higher (44%-83%), with the highest rates observed in adolescents with depressive disorders[5]. Although NSSI is not inherently life-threatening, it is a strong predictor of suicidal ideation and attempts[6]. Moreover, persistent engagement in NSSI can lead to long-term psychosocial difficulties and increased healthcare burden[7,8].

Rumination, a core cognitive feature of depression, refers to repetitive focus on negative thoughts and emotions[9]. Rumination comprises three primary subtypes[10]: (1) Symptom-focused rumination; (2) Brooding; and (3) Reflective pondering. The emotional cascade model[11] suggests that rumination amplifies negative affect, which may trigger NSSI as a maladaptive coping strategy, creating a vicious cycle of distress and self-injury. Empirical evidence supports this pathway. For example, Gromatsky et al[12] identified rumination as a significant risk factor for NSSI; Barrocas et al[13] confirmed its role as a key risk factor in the developmental trajectory of NSSI during adolescence. Different subtypes of rumination have been shown to influence NSSI through distinct pathways[14].

However, prior studies based on traditional statistical methods have primarily focused on overall associations, leaving several important unanswered questions, including: How do rumination subtypes interact with one another? Which specific subtypes are linked to particular NSSI behaviors? Which symptoms act as central hubs sustaining the rumination-NSSI cycle? Network analysis can quantify these associations and identify central nodes for targeted intervention. Recent studies have demonstrated the utility of network approaches in this field. For example, Wang et al[15] conducted a network analysis on a sample of 2184 adolescents and found that symptom-focused rumination demonstrated the strongest centrality across a broad range of emotional symptoms, highlighting its role as a transdiagnostic core node. Similarly, Jia et al[16] employed a temporal network model and observed a bidirectional reinforcement loop between NSSI and negative affect, with somatic symptoms identified as a key bridging node.

Accordingly, in this study, we applied network analysis to a clinical sample of adolescents with depressive disorders to: (1) Construct and visualize associations between rumination subtypes and NSSI behaviors; (2) Identify central and bridging nodes; and (3) Explore direct links between distinct rumination subtypes and individual NSSI behaviors. The analysis results clarify cognitive-behavioral mechanisms and provide precise intervention targets for adolescents with depression and NSSI.

Participants were recruited using convenience sampling approach from a single tertiary psychiatric hospital between October 2023 and February 2025. This approach ensured feasibility and adequate sample size; however, the reliance on a convenience sample from a single site may limit the representativeness of the findings and potentially introduce selection bias. The inclusion criteria were: (1) A clinical diagnosis of depressive episode or recurrent depressive disorder according to the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision; (2) Age between 12 and 18 years; (3) Absence of serious physical illness; and (4) Willingness to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Comorbid psychiatric disorders other than depression; (2) Inability to comprehend the questionnaire or psychometric tools; and (3) Discontinuation during the questionnaire process. These exclusion criteria were intended to reduce potential confounding influences; however, they may also reduce ecological validity given the high prevalence of comorbidities in adolescent depression.

According to network analysis sampling requirements, the minimum sample size must exceed the total number of parameters to be estimated, where total parameters = threshold parameters + pairwise association parameters. Speci

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University (Approval No. XJTU1AF2021 LSK-029). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their legal guardians.

General information questionnaire: A self-developed questionnaire was used to collect participants’ demographic and background information, including age, gender, only-child status, academic performance, school grade, and left-behind child status.

Adolescent NSSI Assessment Questionnaire: Developed by Wan et al[18] in 2018, the Adolescent NSSI Assessment Questionnaire comprises two subscales: (1) Behavioral component; and (2) Functional component. In the current study, only the behavioral subscale was used because our focus was on specific NSSI behaviors (not functions or motivations). This subscale has demonstrated robust psychometric properties in adolescent populations, supporting its suitability for network analysis in the present study. The behavioral subscale consists of 12 items assessing NSSI behaviors across two domains: (1) Behaviors without obvious tissue damage; and (2) Those involving evident tissue damage. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always), with higher scores indicating greater severity of NSSI behavior. The original Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.921, and Cronbach’s alpha in the present sample was 0.932. Following the DSM-5 criteria, participants were identified as having engaged in NSSI if they reported five or more self-injury episodes within the past year.

Ruminative Response Scale: The Ruminative Response Scale used in this study was a revised version adapted by Han and Yang[19] in 2009 based on the original scale developed by Nolen-Hoeksema. The scale consists of 22 items measuring three subtypes of rumination: (1) Symptom-focused rumination; (2) Reflective pondering; and (3) Brooding. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The score for each subtype is calculated by summing the scores of its respective items and dividing by the number of items within that subtype. The original scale demon

Descriptive statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, n (%), and continuous variables with normal distribution were expressed as mean ± SD. Network analysis was conducted using R software version 4.4.3.

Network estimation: A partial correlation network model was constructed to examine the associations between rumination subtypes and NSSI behaviors using the qgraph package in R. To reduce spurious associations, the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator algorithm was employed to estimate a regularized network and visualize its structure[20]. In the network, each rumination subtype and each NSSI item was represented as a node, with edges indicating the strength of association between nodes. In the visualization, thicker edges represent stronger associations. Positive associations are depicted as solid red lines, while negative associations are shown as dashed blue lines.

Computation of centrality indices: Centrality indices including strength, closeness, betweenness, and expected influence (EI) were calculated to assess the importance of each node in the network[21]. Closeness and betweenness centrality have been shown to yield unreliable results and are therefore not recommended as primary indicators of node importance in psychological networks[17]. Strength centrality does not differentiate between positive and negative edges, which may limit its interpretability in networks with mixed associations. EI, defined as the sum of all edge weights connected to a given node, is particularly well-suited for evaluating nodes in networks that contain both positive and negative connections[22]. Accordingly, EI (standardized as z-scores) was used as the primary centrality metric in this study.

The network tools package was used to compute bridge centrality metrics: Bridge strength, bridge closeness, bridge betweenness, and bridge EI (BEI)[23]. BEI was adopted as the key indicator to identify nodes that serve as connectors between communities within the network. Higher BEI values indicate a greater likelihood that a node activates cross-community interactions. The results were reported as standardized z-scores[23].

Assessment of network accuracy and stability: The accuracy and stability of the estimated network were evaluated using the boot net package. First, the accuracy of edge weights was assessed by computing 95% confidence intervals (CI) through nonparametric bootstrap sampling (nBoots = 1500), with narrower CI indicating higher precision of the edge weight estimates. Second, the stability of centrality indices (i.e., EI and BEI) was evaluated using case-dropping subset bootstrapping (nBoots = 1500) to calculate the correlation stability (CS) coefficient. A CS coefficient above 0.25 is considered acceptable, a CS coefficient exceeding 0.50 is considered good, and a CS coefficient greater than 0.70 is considered optimal. Finally, bootstrapped difference tests for edge weights and paired comparisons of node centralities were conducted to examine whether differences between specific edges and centrality metrics were statistically significant. In the CI plots, a wider shaded area in indicates a greater magnitude of difference[17].

A total of 305 adolescents with depression were included (mean age = 15.68 years, SD = 1.70; 29.18% male). Detailed demographic information is shown in Table 1. Among the included adolescents, 234 (76.72%) reported engaging in at least one form of NSSI, underscoring its high prevalence in this clinical population.

| Variable | Category | n (%) |

| Gender | Male | 89 (29.18) |

| Female | 216 (70.82) | |

| Only child | Yes | 92 (30.16) |

| No | 213 (69.84) | |

| Academic performance | Poor | 63 (20.66) |

| Average | 178 (58.36) | |

| Good | 64 (20.98) | |

| Grade | 7th grade (middle school year 1) | 23 (7.54) |

| 8th grade (middle school year 2) | 42 (13.77) | |

| 9th grade (middle school year 3) | 49 (16.07) | |

| 10th grade (middle school year 1) | 50 (16.39) | |

| 11th grade (high school year 2) | 60 (19.67) | |

| 12th grade (high school year 3) | 48 (16.74) | |

| Dropped out | 13 (4.26) | |

| On leave | 20 (6.56) | |

| Left-behind children | Yes | 20 (6.60) |

| No | 285 (93.44) |

Table 2 presents the mean scores for the three rumination subtypes and 12 NSSI behaviors. Among rumination subtypes, reflective pondering (mean = 2.97, SD = 0.69) showed the highest mean score. For NSSI, cutting (mean = 1.85, SD = 1.60) and pinching (mean = 1.64, SD = 1.40) were the most frequently reported behaviors, whereas burning (mean = 0.38, SD = 0.93) was relatively rare. These descriptive patterns indicate variability in both rumination styles and NSSI behaviors among adolescents with depression.

| Variables | mean ± SD |

| Rumination | |

| R1: Symptom-focused rumination | 2.92 ± 0.63 |

| R2: Brooding | 2.56 ± 0.69 |

| R3: Reflective pondering | 2.97 ± 0.69 |

| NSSI | |

| NSSI1: Deliberately pinching oneself | 1.64 ± 1.40 |

| NSSI2: Deliberately scratching oneself | 1.48 ± 1.39 |

| NSSI3: Intentionally banging one’s head against objects | 1.36 ± 1.33 |

| NSSI4: Intentionally punching walls, tables, windows or the ground | 1.46 ± 1.39 |

| NSSI5: Striking oneself with fists, slaps or hard objects | 1.46 ± 1.39 |

| NSSI6: Deliberately biting oneself | 1.32 ± 1.44 |

| NSSI7: Pulling out one’s own hair intentionally | 1.00 ± 1.35 |

| NSSI8: Stabbing or piercing oneself deliberately | 1.33 ± 1.48 |

| NSSI9: Deliberately cutting oneself | 1.85 ± 1.60 |

| NSSI10: Burning or scalding oneself intentionally | 0.38 ± 0.93 |

| NSSI11: Rubbing the skin with objects to cause bleeding or bruising | 0.90 ± 1.28 |

| NSSI12: Carving words or symbols into the skin | 0.60 ± 1.12 |

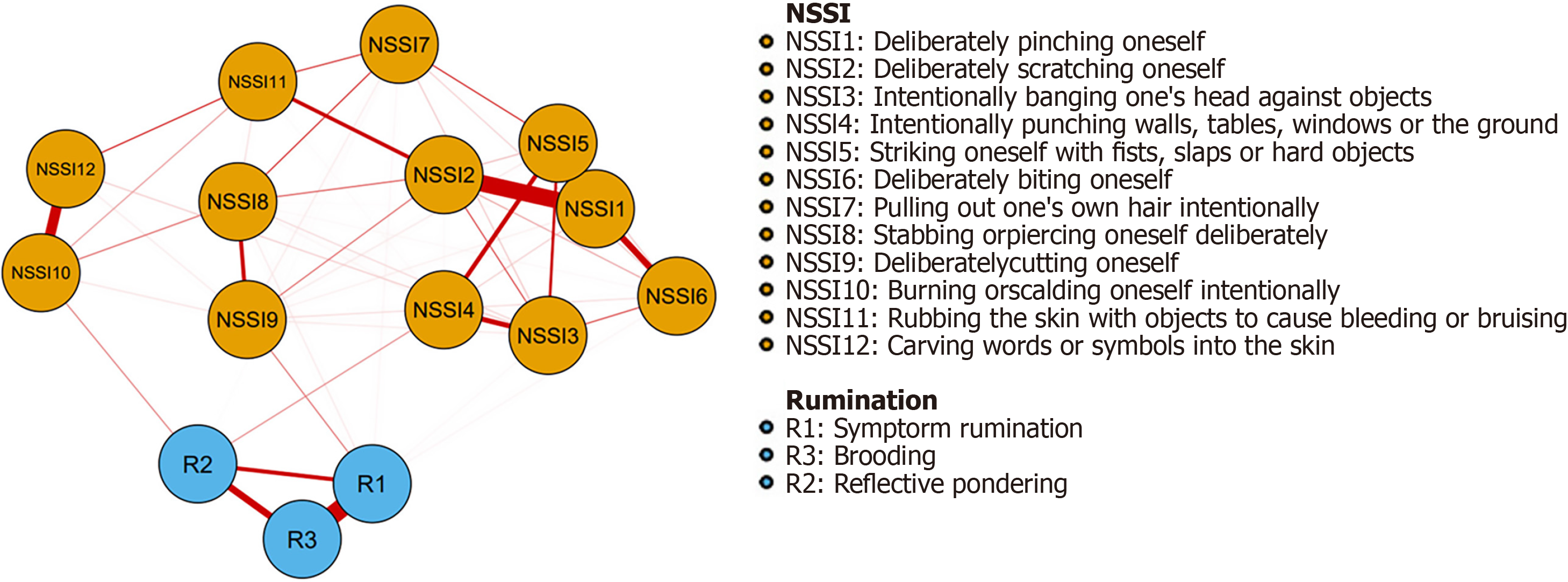

The estimated network contained 105 possible edges, of which 64 (60.95%) had non-zero weights, indicating a densely interconnected system (Figure 1).

Within the rumination subnetwork, symptom-focused rumination (R1) and reflective pondering (R3) were strongly linked (weight = 0.49), reflecting their conceptual overlap as forms of repetitive, self-focused thought. In the NSSI subnetwork, the strongest connection was between deliberately pinching oneself (NSSI1) and scratching oneself (NSSI2) (weight = 0.48). This connection suggests that these behaviors may cluster together as lower-severity, more common forms of self-injury.

Across domains, brooding (R2) was associated with both hitting hard objects (NSSI4) and burning oneself (NSSI10) (weights = 0.10). Although modest in size, these cross-links suggest that brooding-a maladaptive rumination style-may bridge cognitive vulnerability with both frequent (hitting) and severe (burning) forms of NSSI. All edge weights are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

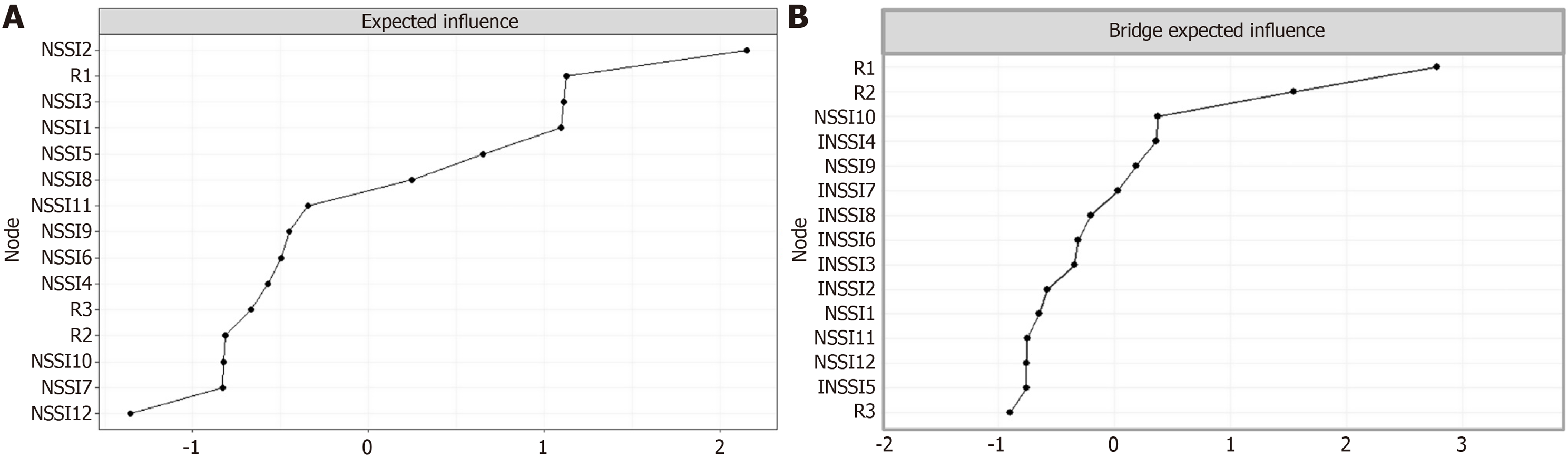

As shown in Figure 2A, scratching oneself (NSSI2) emerged as the most influential behavior (EI = 2.14) in the network. This indicates that scratching may be a central behavior that sustains or propagates other forms of NSSI. Thus, scratching can be considered as a potential clinical marker for early detection and intervention.

Bridge centrality analysis (Figure 2B) further highlighted symptom-focused rumination (R1) as the most prominent bridging node (BEI = 2.78). This suggests that symptom-focused rumination links cognitive processes with self-injurious behaviors. Thus, targeting symptom-focused rumination could disrupt maladaptive cognitive–behavioral cycles in depressed adolescents.

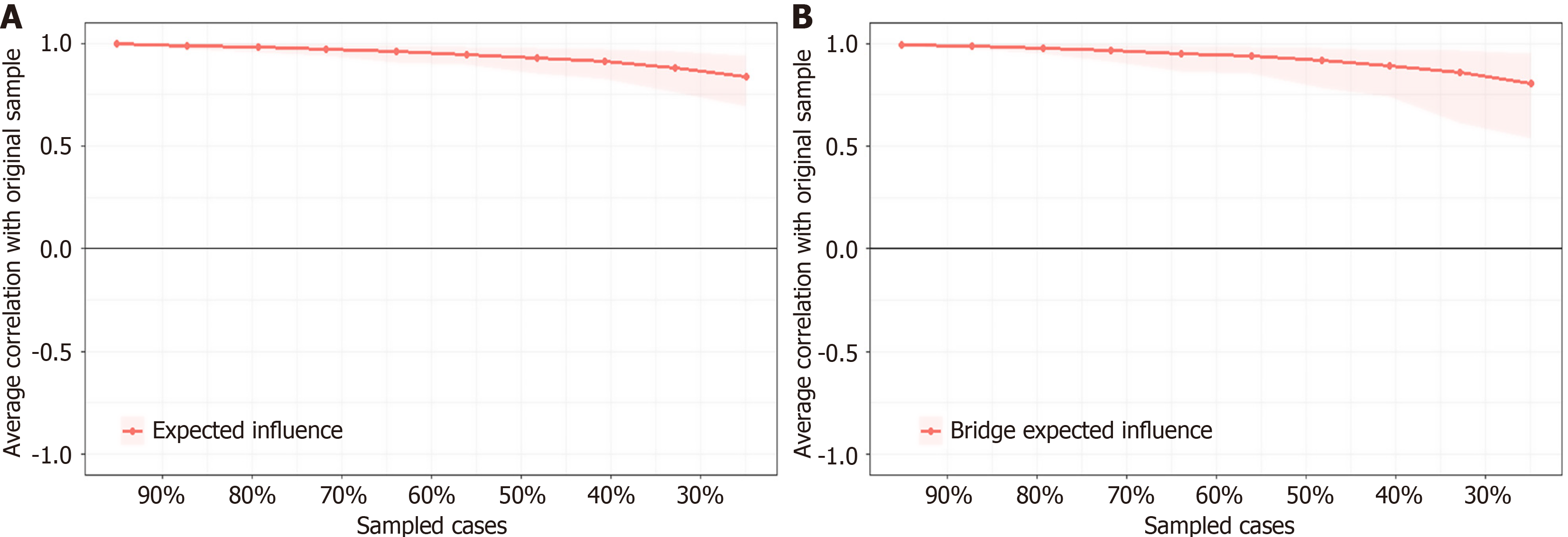

Nonparametric bootstrap analyses showed narrow 95%CI for edge weights, supporting their accuracy (Supplementary Figure 1). Stability analyses indicated acceptable robustness, with centrality stability coefficients of 0.67 for both EI and BEI (Figure 3). Difference tests further confirmed significant variability across edge weights and centrality indices (Supplementary Figures 2-4). These findings provide confidence in the reliability of the observed network patterns.

This study is the first to apply network analysis to examine associations between specific subtypes of rumination (symptom-focused rumination, brooding, and reflective pondering) and individual NSSI behaviors among adolescents with depression. The findings reveal underlying connectivity patterns, identify central hub nodes, and highlight potential clinical implications. Importantly, although symptom-focused rumination and scratching emerged as central nodes, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference; all results should be interpreted as observed associations rather than direct causal effects.

The network comprised 105 possible edges, with 64 (60.95%) exhibiting non-zero weights. This network structure indicates a densely interconnected system of rumination subtypes and NSSI behaviors. The high interconnectivity suggests that rumination and NSSI are not isolated phenomena but components of a mutually reinforcing system of symptom maintenance. Although these findings support the potential value of integrated clinical interventions, longitudinal studies are required to clarify the temporal directionality of these associations.

Within the rumination subnetwork, the strongest connection occurred between symptom-focused rumination (R1) and reflective pondering (R3) (weight = 0.49). This indicates a cognitive synergy between excessive focus on negative symptoms and repeated attempts to analyze one's emotional state, despite limited effectiveness. These processes may contribute to a cognitive loop that sustains or exacerbates depressive affect. This interpretation aligns with Nolen-Hoeksema’s response styles theory[24], which posits that excessive attention to depressive symptoms (e.g., “Why do I always feel exhausted?”) may lead to overanalysis of emotional origins (e.g., “Is my depression due to personal failure?”), creating a “cognitive vortex”. In this context, NSSI has been conceptualized as a maladaptive dissociation strategy, whereby physical pain temporarily redirects attention away from uncontrollable rumination[25]. Nevertheless, given the reliance on self-reported questionnaires, potential measurement bias should be acknowledged, and future studies incorporating multi-method assessment are warranted.

Within the NSSI network, the strongest connection was observed between deliberately pinching oneself (NSSI1) and scratching oneself (NSSI2) (weight = 0.48), consistent with prior findings[26]. This suggests a clustering of behaviors involving superficial skin injury. Possible explanations include functional similarity (e.g., rapid relief from intense emotional distress), practical convenience (e.g., easily accessible tools, discreet implementation), or behavioral habituation (i.e., a tendency toward fixed behavioral patterns). Although we have proposed exploratory alternatives (e.g., non-injurious sensory substitution), these remain speculative and lack empirical validation. Our suggestions should therefore be regarded as hypotheses for future intervention research rather than evidence-based recommendations.

Cross-network analysis revealed that brooding (R2) was associated with both hitting hard objects (NSSI4) and burning oneself (NSSI10) (weight = 0.10). This suggests that adolescents engaged in abstract and passive ruminative states may be more prone to severe or impulsive self-injury. Our findings support the avoidance theory of rumination, which posits that brooding may amplify emotional distress and feelings of detachment from reality, thereby increasing the likelihood of using more extreme bodily methods to regulate or interrupt aversive internal states[27]. Clinically, adolescents exhibiting high levels of brooding may warrant close monitoring. However, the interpretations should be considered with caution; cultural context, developmental stage, and comorbid conditions may shape the observed associations. Future research should examine whether these patterns generalize across different cultural backgrounds, early vs late adole

It is important to note that all participants were Chinese adolescents, and cultural factors may influence the expression, meaning, and reporting of NSSI[28]. Cultural norms, stigma associated with mental health, and social attitudes toward self-injury in Chinese adolescents may differ substantially from Western populations[29]. For example, adolescents in China may underreport NSSI due to fear of social disapproval or family repercussions, and the motivations or symbolic meanings of self-injury may vary culturally[30]. Therefore, caution is warranted when generalizing these findings to adolescents from other cultural contexts. Future research should explicitly examine cultural influences on NSSI networks and symptom expression.

Centrality analysis identified scratching oneself (NSSI2) as the node with the highest EI = 2.14. This indicates that scratching occupies a central position within the NSSI spectrum and is broadly connected to other self-injurious behaviors and rumination subtypes. Although this connectivity pattern suggests that NSSI2 is particularly influential, this interpretations remains tentative. Further longitudinal research is needed to clarify whether changes in NSSI2 affect the broader network. Symptom-focused rumination (R1), characterized by persistent focus on depressive symptoms such as low mood, fatigue, and worthlessness, emerged as the most important bridge node (BEI = 2.78). Rather than implying direct causality, this finding highlights R1 as a cognitive mechanism associated with NSSI behaviors and underscores its potential role in linking cognitive and behavioral processes.

Taken together, these results highlight scratching oneself (NSSI2) and symptom-focused rumination (R1) as potential intervention targets. Approaches such as cognitive restructuring, attentional redirection, and mindfulness (for R1) and behavioral skills training and environmental management (for NSSI2) appear theoretically relevant, although they remain exploratory at this time. These exploratory intervention strategies requires further empirical validation to validate their clinical efficacy and solidify them as established, evidence-based interventions.

Despite providing novel insights, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged.

As the network analysis was based on cross-sectional data, it could not determine the directionality of causal rela

The adolescent subjects were recruited exclusively from a single tertiary hospital in China, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Adolescents in inpatient settings may present with higher symptom severity, greater behavioral dysregulation, and more acute risk profiles than those in outpatient or community settings, potentially influencing both the network structure and centrality of certain nodes. Therefore, our results may not reflect the broader population of adolescents with depression or NSSI behaviors. Future studies should replicate these analyses in community-based, outpatient, and cross-cultural samples to assess whether the observed network patterns hold across different settings, cultural backgrounds, and clinical severities.

All variables were assessed via self-reported questionnaires, which may be subject to recall bias, underreporting (particularly for sensitive behaviors such as NSSI), and social desirability effects. To strengthen the validity and reliability of the findings, future studies should consider integrating multi-method assessments such as clinician-rated measures, behavioral tasks, ecological momentary assessment, and collateral reports from caregivers or teachers.

Adolescence is a heterogeneous stage. The rumination–NSSI network may vary across early and late adolescence, requiring subgroup analyses in future research.

The current network model included only rumination subtypes and NSSI behaviors, omitting other important correlates such as trauma history, family functioning, peer relationships, emotion regulation, and biological markers. The exclusion of these variables may limit the comprehensiveness of the network and obscure potential pathways influencing NSSI. Future studies should consider building more complex, multidimensional network models that integrate these psy

The study was conducted in a single cultural context (Chinese adolescents), The cultural norms, stigma, and meanings of NSSI in this cultural context may differ from other populations. This may affect both reporting and network structure, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Future studies should examine cross-cultural samples to explore whether observed patterns hold in different cultural contexts.

We constructed an association network between rumination subtypes and NSSI items, revealing complex, densely interconnected relationships between cognitive (rumination) and behavioral (NSSI) symptoms among adolescents with depression. Symptom-focused rumination (R1) served as a core bridge node linking cognitive and behavioral processes, and scratching oneself (NSSI2) emerged as the most influential NSSI behavior, while brooding (R2) showed specific connections with high-intensity NSSI behaviors (hitting and burning). These results highlight potential targets for further research, although the findings should be interpreted cautiously due to the cross-sectional, single-site design and reliance on self-reported measures. Future longitudinal, multi-center studies are warranted to clarify causal mechanisms, temporal dynamics, and generalizability across diverse adolescent populations.

| 1. | He S, Li C, Zhang S, Hu Y, Wen J, Liu L, Gao J, Wu J, Huang G. The complexity of associations between emotion regulation, interpersonal sensitivity, cognitive insight, and non-suicidal self-injury: a study based on network analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2025;25:846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Xiao Q, Song X, Huang L, Hou D, Huang X. Global prevalence and characteristics of non-suicidal self-injury between 2010 and 2021 among a non-clinical sample of adolescents: A meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:912441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 38.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lang J, Yao Y. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in chinese middle school and high school students: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Muehlenkamp JJ, Brausch AM, Littlefield A. Concurrent changes in nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide thoughts and behaviors. Psychol Med. 2023;53:4898-4903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mars B, Heron J, Klonsky ED, Moran P, O'Connor RC, Tilling K, Wilkinson P, Gunnell D. Predictors of future suicide attempt among adolescents with suicidal thoughts or non-suicidal self-harm: a population-based birth cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:327-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 48.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Richmond-Rakerd LS, Caspi A, Arseneault L, Baldwin JR, Danese A, Houts RM, Matthews T, Wertz J, Moffitt TE. Adolescents Who Self-Harm and Commit Violent Crime: Testing Early-Life Predictors of Dual Harm in a Longitudinal Cohort Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176:186-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang YJ, Li X, Ng CH, Xu DW, Hu S, Yuan TF. Risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescents: A meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;46:101350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 37.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Paris J. Social contagion, the psychiatric symptom pool and non-suicidal self-injury. BJPsych Bull. 2025;49:329-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Watkins ER, Roberts H. Reflecting on rumination: Consequences, causes, mechanisms and treatment of rumination. Behav Res Ther. 2020;127:103573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 424] [Article Influence: 70.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zou M, Liu B, Ren L, Mu D, He Y, Yin M, Yu H, Liu X, Wu S, Wang H, Wang X. The association between aspects of expressive suppression emotion regulation strategy and rumination traits: a network analysis approach. BMC Psychol. 2024;12:501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hasking PA, Di Simplicio M, McEvoy PM, Rees CS. Emotional cascade theory and non-suicidal self-injury: the importance of imagery and positive affect. Cogn Emot. 2018;32:941-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gromatsky MA, He S, Perlman G, Klein DN, Kotov R, Waszczuk MA. Prospective Prediction of First Onset of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in Adolescent Girls. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59:1049-1057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Barrocas AL, Giletta M, Hankin BL, Prinstein MJ, Abela JR. Nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescence: longitudinal course, trajectories, and intrapersonal predictors. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2015;43:369-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Polanco-Roman L, Jurska J, Quiñones V, Miranda R. Brooding, Reflection, and Distraction: Relation to Non-Suicidal Self-Injury versus Suicide Attempts. Arch Suicide Res. 2015;19:350-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang J, Wang T, Cheng Y. Longitudinal Dynamics of Anxiety and Depression in Adolescents With a History of Childhood Maltreatment: A Cross-Lagged Panel Network Analysis. Stress Health. 2025;41:e70076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jia Q, Wu Z, Liu B, Feng Y, Liang W, Liu D, Song L, Li C, Yang Q. Exploring the longitudinal relationships between non-suicidal self-injury and depressive symptoms in adolescents: a cross-lagged panel network analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2025;25:358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Epskamp S, Borsboom D, Fried EI. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behav Res Methods. 2018;50:195-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1902] [Cited by in RCA: 3023] [Article Influence: 377.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wan YH, Liu W, Hao JH, Tao FB. [Development and evaluation on reliability and validity of Adolescent Non-suicidal Self-injury Assessment Questionnaire]. Zhongguo Xuexiao Weisheng Zazhi. 2018;39:170-173. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Han X, Yang HF. [Chinese Version of Nolen-Hoeksema Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS) Used in 912 College Students: Reliability and Validity]. Zhongguo Linchuang Xinlixue Zazhi. 2009;17:550-551+549. |

| 20. | Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol. 1996;58:267-288. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8558] [Cited by in RCA: 7072] [Article Influence: 884.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Robinaugh DJ, Millner AJ, McNally RJ. Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. J Abnorm Psychol. 2016;125:747-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 331] [Cited by in RCA: 1021] [Article Influence: 102.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bringmann LF, Elmer T, Epskamp S, Krause RW, Schoch D, Wichers M, Wigman JTW, Snippe E. What do centrality measures measure in psychological networks? J Abnorm Psychol. 2019;128:892-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jones PJ, Ma R, McNally RJ. Bridge Centrality: A Network Approach to Understanding Comorbidity. Multivariate Behav Res. 2021;56:353-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 910] [Article Influence: 182.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:569-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nock MK. Why do People Hurt Themselves? New Insights Into the Nature and Functions of Self-Injury. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18:78-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 797] [Cited by in RCA: 725] [Article Influence: 42.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Xie X, Li Y, Liu J, Zhang L, Sun T, Zhang C, Liu Z, Liu J, Wen L, Gong X, Cai Z. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents with depressive disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2024;331:115638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gordon KH, Holm-Denoma JM, Troop-Gordon W, Sand E. Rumination and body dissatisfaction interact to predict concurrent binge eating. Body Image. 2012;9:352-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chen X, Zhou Y, Li L, Hou Y, Liu D, Yang X, Zhang X. Influential Factors of Non-suicidal Self-Injury in an Eastern Cultural Context: A Qualitative Study From the Perspective of School Mental Health Professionals. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:681985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Brown RC, Witt A. Social factors associated with non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2019;13:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wang L, Zou H, Yang Y, Hong J. Adolescents' attitudes toward non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and their perspectives of barriers to seeking professional treatment for NSSI. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2023;45:26-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/