INTRODUCTION

Major depressive disorder (MDD), a prevalent psychiatric condition characterized by a persistent depressed mood, diminished interest or pleasure, and cognitive-behavioral impairments, typically emerges during late adolescence or early adulthood[1]. The World Health Organization[2] estimates a global prevalence of MDD affecting approximately 300 million individuals, positioning it as a primary contributor to disability burden globally. Notably, MDD is a leading cause of disability in adolescents, with incidence rates rising markedly during this developmental period[3].

Suicide represents the second leading cause of death among adolescents worldwide, with depressive disorders constituting a predominant risk factor for suicidality in this population[4]. Common risk factors for suicide include substance misuse, depression, hopelessness, stressful life events, social and environmental influences, and flawed personal cognitive patterns[5]. Research has indicated that adolescent suicide risk is usually caused by a confluence of societal, familial, interpersonal, and personal factors[6]. Epidemiological evidence suggests a lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts in approximately 25% of adolescents diagnosed with MDD[7]. Glenn et al[8] demonstrated a marked escalation in suicide attempt incidence across the developmental trajectory from early to late adolescence. Notably, adolescents with MDD exhibit heightened rates of depression recurrence and suicidal ideation relative to adult counterparts[9]. These findings collectively underscore the imperative to elucidate the neurobiological mechanisms underlying suicidal behavior in adolescents with MDD.

As an important part of the limbic system of the brain, the amygdala plays a key role in processing threats and regulating complex emotional and physiological responses[10]. Accumulating evidence implicates a strong link between functional and structural aberrations in the amygdala and MDD pathophysiology and suicidal behavior. Zhu et al[11] identified altered resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) between the left amygdala and left parahippocampal gyrus (PHG) in individuals with bipolar II disorder and a history of suicide attempts. One study[12] noted that the amygdala of depressed adolescents showed significantly greater activation during emotional self-regulation compared with controls. Zhang et al[13] found abnormal functional connectivity between the amygdala and the brain to be associated with suicidal behavior in patients with mood disorders. Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies further revealed right amygdala enlargement in female MDD patients with suicidal behavior compared to non-suicidal counterparts[14]. In addition, relevant studies have shown that low self-esteem is one of the psychosocial factors that induce suicidal behavior, and that depression and low self-esteem are significantly correlated with suicidal ideation in adolescents[15].

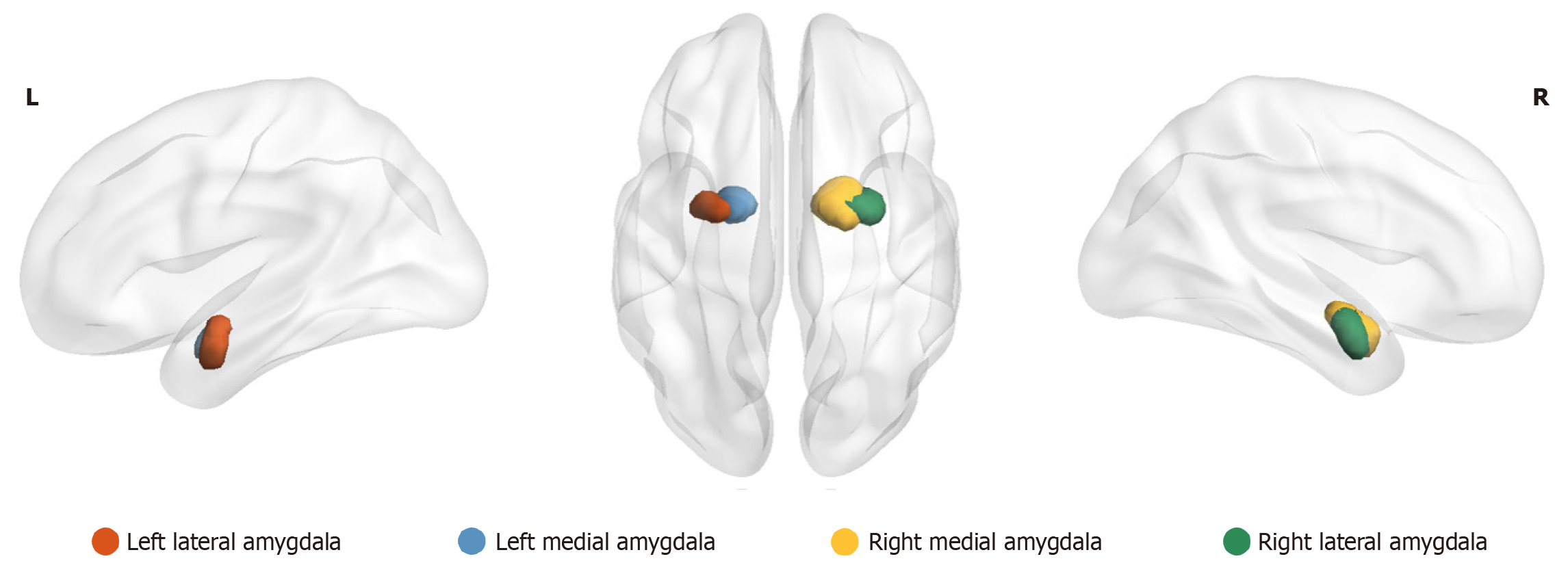

Currently, most resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) studies focus on the functional connectivity analysis of the amygdala as a whole, overlooking the heterogeneity of its internal subregions and thereby neglecting potential abnormal connectivity patterns within these subregions. A previous study[16] developed a connectivity-based delineation framework, the Human Brainnetome Atlas, to identify two amygdala subregions – the medial amygdala (MeA) and the lateral amygdala (LA), and elucidated the distinct functional connectivity profiles of these subregions. Research[17] has also demonstrated that the MeA plays a critical role in behavior, physiological regulation, and cognition, while also serving as a key node in social behavioral networks. The LA is pivotal in threat detection and fear response regulation, exhibiting heightened activity during exposure to threat-like stimuli to generate adaptive emotional responses[18]. Therefore, in this study, we selected LA and MeA as regions of interests (ROIs) to conduct a whole-brain rsFC analysis to determine their differences between depressed adolescents with and without suicide attempts, as well as healthy individuals (Figure 1), which may provide potential research directions and a basis for exploring biomarkers and clinical treatment of high-risk individuals for suicide in the future. We hypothesized that there was a specific rsFC pattern between the four subregions of the amygdala and the brain in those with MDD and a history of suicide attempts (sMDD) group, compared to those with MDD but without suicide attempts (nsMDD) group and the healthy control (HC) group.

Figure 1 Subregions of the medial and lateral amygdala in the right and left hemispheres.

L: Left; R: Right.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Sixty-nine adolescent patients with depression hospitalized in The Affiliated Guangji Hospital of Soochow University from October 2022 to July 2023 were included. Based on clinical suicide records and interviews with study participants and their families, and with reference to the Columbia Classification Algorithm for Suicide Assessment criteria for the “attempted suicide” definition[19]: “An individual who has the intention to end his or her life and has taken action that did not ultimately result in death” was used to categorize the patients into the sMDD group and the nsMDD group. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Age: 11-18 years; (2) Han Chinese, right-handed; (3) Using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)[20], patients were assessed in a structured manner by 2 trained psychiatrists at the attending or higher level, and met the diagnostic specifications of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition in the United States[21]; (4) Primary school education or above; (5) 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) score ≥ 5 points[22]; and (6) No systemic antidepressant medication was administered prior to admission. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Previous history of other psychiatric disorders; (2) Presence of substance dependence or abuse; (3) Contraindications for MRI examination; (4) History of electroconvulsive therapy in the month prior to enrollment; and (5) Comorbidities such as organic brain diseases or head trauma. Thirty-eight HCs matched with the general characteristics of the patient group were recruited from the community, and the inclusion criteria were: (1) Not meeting the diagnostic criteria of any mental disorder; (2) No family history of mental illness; (3) No suicidal behavior or family history of suicide; (4) No contraindications to the MRI examination; and (5) No serious organic lesions in the body, and no drug dependence or abuse. Also, gender, age, years of education, and the PHQ-9, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES), and MINI suicide subscales were recorded in these subjects. After preprocessing the MRI data, subjects with head motion displacement greater than 2 mm and offset angle greater than 2° were excluded from the sMDD group, 2 subjects were excluded from the nsMDD group, and 4 subjects were excluded from the HC group. Finally, 32 subjects were enrolled in the sMDD group, 33 subjects in the nsMDD group, and 34 subjects in the HC group. All participants and their legal guardians provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of The Affiliated Guangji Hospital of Soochow University, No. 2019-054.

Data acquisition

All subjects were scanned using a Siemens Skyra 3.0T MRI scanner equipped with a 20-channel head-neck coil. Prior to scanning, participants were instructed to keep their eyes closed, remain motionless, stay awake, and minimize active thinking as much as possible. During scanning, participants were placed in the supine position, wore noise-reducing earplugs, and their heads were immobilized using foam padding. Functional imaging was performed using an echo planar imaging sequence with the following parameters: (1) Repetition time (TR): 2000 milliseconds; (2) Echo time (TE): 30 milliseconds; (3) 32 axial slices; (4) Slice thickness: 3.5 mm; (5) Flip angle: 90°; (6) Field of view (FOV): 224 × 224 mm²; and (7) 240 volumes acquired. Structural images were acquired using a T1-weighted three-dimensional magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo sequence with the parameters: (1) TR: 2530 milliseconds; (2) TE: 2.98 milliseconds; (3) 192 sagittal slices; (4) Slice thickness: 1.0 mm; (5) Flip angle: 7°; and (6) FOV: 256 × 256 mm².

Data processing

The rs-fMRI data were preprocessed using the Data Processing and Analysis of Brain Imaging (DPABI v8.2) toolbox in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA, United States). Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine format images were converted to Neuroimaging Informatics Technology Initiative format prior to preprocessing. The preprocessing pipeline included: (1) Removal of the first 10 time points to ensure data stability; (2) Slice timing correction to address inter-slice temporal discrepancies; (3) Realignment to correct head motion, excluding participants with framewise displacement > 2 mm or angular rotation > 2°; (4) Spatial normalization to the Montreal Neurological Institute template, followed by resampling to 3 mm × 3 mm × 3 mm; (5) Spatial smoothing using a 4 mm full-width at half-maximum Gaussian kernel; (6) Remove linear drift; (7) Control of covariates to exclude the effects of head movement, cerebrospinal fluid, and cerebral white matter signals; and (8) Filtering of the frequency band from 0.01 Hz to 0.08 Hz.

Functional connectivity analysis

Functional connectivity analysis was performed using DPABI v8.2 software based on MATLAB. For the definition of ROIs, we chose four subregions of the amygdala, namely, the left LA, the right LA, the left MeA, and the right MeA. First, the average time series of all voxels within the four subregions of the amygdala was calculated, and then Pearson correlation analysis was performed with the whole-brain voxel time series to obtain the value of the correlation coefficient r. Finally, the normality was improved by the Fisher r-to-z transformation.

Statistical analysis

For demographic data and clinically relevant scales, we used IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences statistics 27.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States) for statistical analysis. Quantitative information that followed a normal distribution was expressed as mean ± SD. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparisons between the three groups, and the Bonferroni test was used for post hoc two-by-two comparisons. Qualitative information was expressed in the form of percentages, and the χ2 test was used. Differences with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For the analysis of MRI data, we used the statistical module in DPABI v8.2. ANOVA was used to analyze the rsFC between the three groups, and head movement parameters, gender, age, and years of education were used as covariates. Subsequently, gaussian random field correction was performed on the brain regions with differences in rsFC between the three groups, with P < 0.001 at the voxel level and P < 0.05 at the cluster level, indicating statistically significant differences. Pearson's correlation test was performed for the brain regions and clinical scales where differences existed, and the differences were statistically significant when P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

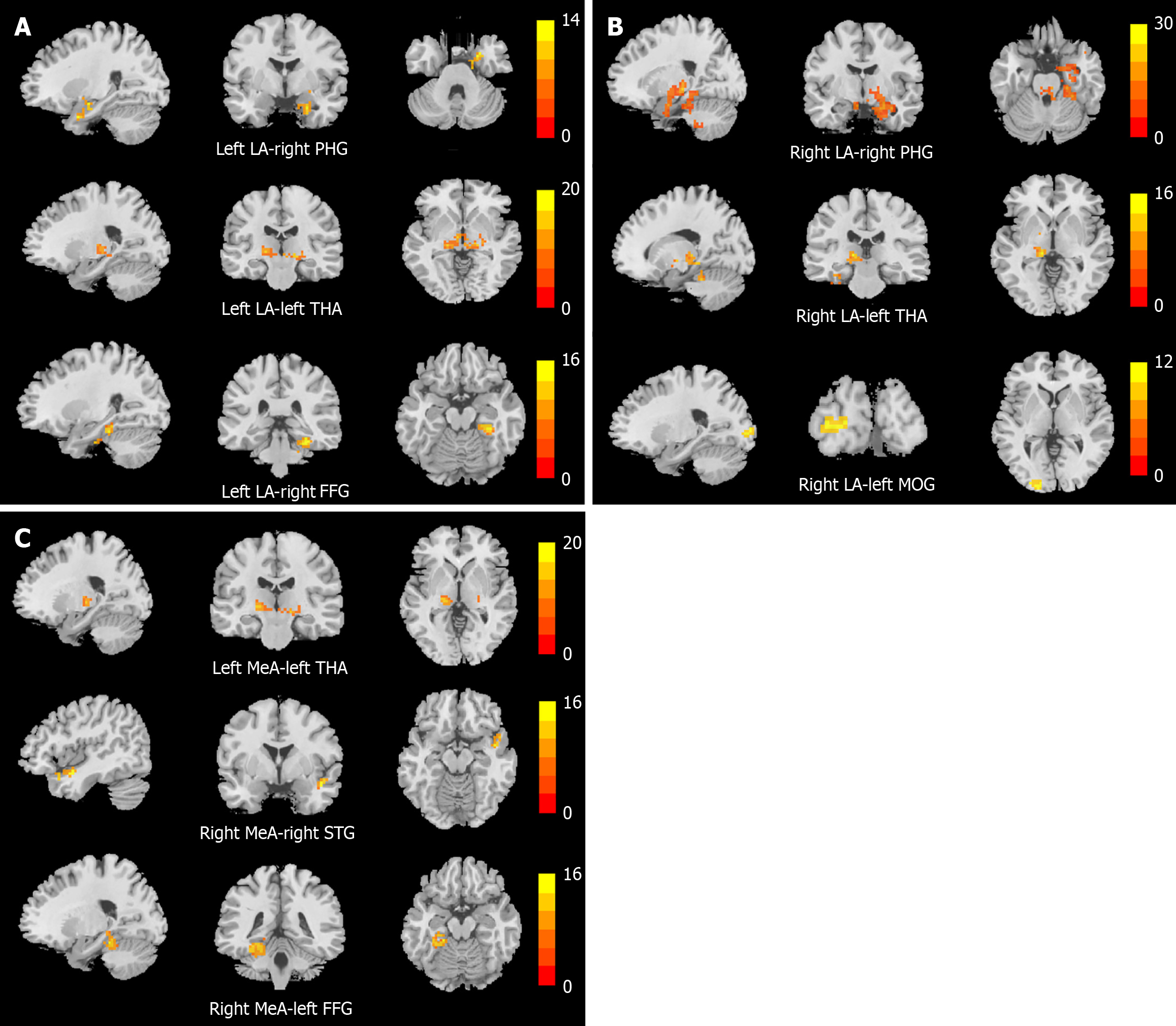

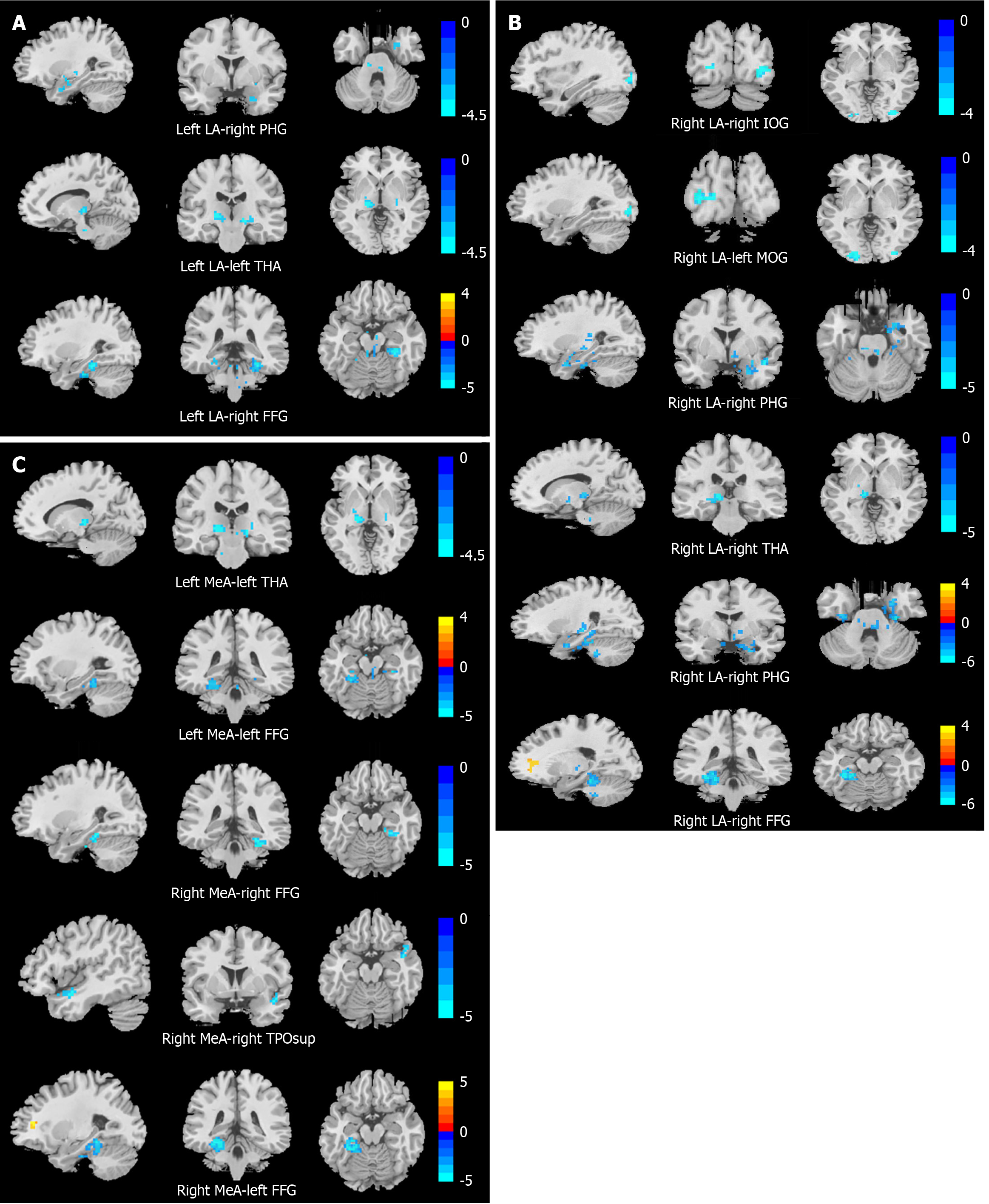

This study employed four amygdala subregions as ROIs to compare rsFC among adolescents with MDD with suicidal behavior, MDD without suicidal behavior, and HCs. Notably, the sMDD group exhibited altered rsFC between the right LA and both the right IOG and left MOG relative to the nsMDD group. Compared to HCs, the sMDD group demonstrated reduced rsFC between amygdala subregions and the right PHG, left THA, right FFG, and right TPOsup. Similarly, the nsMDD group showed diminished rsFC between amygdala subregions and the right FFG, left FFG, and right PHG. These findings suggest that rsFC dysregulation in subregions of the amygdala, especially dysregulated connectivity in occipital areas (IOG, MOG) associated with visual processing, may be a potential neural correlate of suicidal behavior in adolescents with MDD.

In the current study, the sMDD group exhibited reduced rsFC between the right LA and both the right IOG and left MOG compared to the nsMDD group. The IOG and MOG, located in the occipital lobe, are critical nodes in visual-emotional processing. The IOG is involved in the initial processing of visual information and is considered to be an important region for emotion regulation in patients with mood disorders[23]. The MOG is not only responsible for the visual information high-level processing, but it is also involved in inter-cortical information integration, especially in facial emotion perception[24]. Thus, aberrant functional changes in the IOG and MOG may impair emotional information processing and responsiveness in MDD. Previous research[25] reported dysregulated visual processing in suicidal individuals, marked by hypoactivation of occipital regions during facial emotion tasks. A functional MRI (fMRI) study[26] demonstrated attenuated blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) responses in the occipital cortex of adolescents with MDD during exposure to sad faces, indicating impaired inhibition of negative emotional stimuli. Additionally, dysfunction in the occipital lobe may contribute to a negative perceptual bias toward facial emotional stimuli and impair visual processing of negative stimuli in individuals with MDD, potentially increasing suicide risk[27]. Further research has demonstrated that individuals with MDD who have a history of suicide attempts exhibit abnormalities in the cortical hierarchical organization of the visual network, predominantly localized in the occipital lobe. This structural disruption predisposes patients to maintain prolonged attention on negative visual stimuli and display heightened sensitivity to such stimuli, thereby exerting a direct impact on the emotional processing system and potentially contributing to the emergence of suicidal behavior[28]. Notably, the occipital lobe not only contains the primary anatomical components of the visual cortex, which is responsible for detecting external stimuli and relaying this information to brain regions involved in emotional processing[29], but also constitutes a component of the frontal-subcortical circuit implicated in emotional regulation[30]. Given the functional integration of these regions in visual information processing and emotional regulation, the brain is capable of modulating an individual's emotional state through the coordinated processing of visual stimuli.

Several suicide-related MDD studies have found functional abnormalities in the IOG and MOG. For instance, one study[31] found that dynamic degree centrality values of the left IOG and dynamic voxel-mirrored homotopic connectivity values of the right IOG were lower in the MDD group with suicidal ideation than in the MDD group without suicidal ideation. Similarly, Chen et al[32] observed diminished functional connectivity strength in the right IOG in MDD patients with prior suicide attempts. Fan et al[33] further demonstrated that MDD patients with suicidal behavior exhibited reduced amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) in the left MOG relative to HCs. Notably, Yue et al[34] documented attenuated functional connectivity between the right amygdala and right MOG in MDD patients, which is similar to our findings. Collectively, our results suggest that diminished rsFC between the right LA and occipital regions (IOG/MOG) may impair the integration of visual-emotional information, thereby exacerbating deficits in emotional processing and cognitive regulation in MDD and heightening suicide risk. This finding provides a new perspective for understanding the neural mechanisms of suicide in depressed adolescents, and the potential role of the occipital cortex in the pathogenesis of suicide in depressed adolescents should be further explored in the future. This study uncovered abnormal rsFC in the right LA, right IOG, and left MOG within the sMDD group. Additionally, previous investigations have shown that structural and functional deficits in the occipital lobe of MDD patients are intricately linked to cognitive impairment. The occipital lobe could potentially be a viable candidate target for repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) therapy in MDD patients[35]. The study by Zhang et al[36] employed individualized rTMS targeting the visual cortex for the treatment of depression, and further corroborated that left occipital rTMS represents a safe, effective, and well-tolerated therapeutic option. Integrating the results of this study, it is proposed that the occipital lobe region might be a potential target for neuromodulation therapies.

Both the sMDD and nsMDD groups demonstrated reduced rsFC between the right LA and right PHG compared to HCs, suggesting overlapping neural mechanisms underlying depressive and suicidal symptomatology. The PHG is part of the limbic system, which is closely associated with functions such as memory, cognition, and emotion regulation[37]. An rsFC study on MDD found[38] that the PHG showed high discriminatory power in distinguishing depressed patients from healthy individuals, suggesting that abnormal functional connectivity in this brain region may be related to the impaired emotion-mediated memory formation exhibited by patients with MDD. Furthermore, previous studies have found that patients with MDD have reduced interhemispheric rsFC in the PHG, and that reduced functional connectivity between the PHG bilaterally may affect the coordination of this region in tasks, which may lead to emotional problems in patients with MDD[39]. Neuroimaging evidence has shown inactivation of regions of the PHG in individuals who have attempted suicide[40]. Kang et al[41], on the other hand, found a significant correlation between the intensity of suicidal ideation and the rsFC between the right amygdala and the right PHG in patients with MDD and suicide attempts. Similarly, a study on an adolescent population found[42] that rsFC from the amygdala to the right PHG was lower in MDD patients with destructive behaviors than in healthy subjects, which is similar to the results in the present study, in that suicidal behaviors are the internalization of emotional problems, while destructive behaviors are the externalization, but in essence, both are poor ways for individuals to cope with negative emotions, and both may stem from inefficient amygdala-PHG integration of negative emotional stimuli. Our findings indicate a positive correlation between the rsFC value of the left LA and the right PHG and the interpersonal relationship score on the ASLEC. It is reported that stressful life events constitute a significant psychosocial factor for suicide attempts among adolescents[43]. Interpersonal relationships significantly influence adolescents' cognitive, emotional, and personality development[44], while poor relationships can easily lead to depression and even suicide[45]. Therefore, we propose that neural circuits involving the amygdala and PHG may underlie interpersonal adaptation processes in adolescents with MDD, serving as a key function in regulating emotional responses to interpersonal stimuli. In summary, the abnormal connectivity of the amygdala to the PHG may exacerbate patients' depressive symptoms and increase susceptibility to suicidal behavior.

Our study identified reduced rsFC in the right MeA and right FFG in the sMDD group, and in the left LA and right FFG in the nsMDD group, compared with healthy individuals, further supporting the important role of the FFG in patients with MDD. The FFG, a hub for visual processing, social cognition, and face recognition, exhibits bidirectional connectivity with the amygdala during facial emotion processing[46]. Dysfunction in the FFG has been linked to impaired perception of emotional faces in adolescents with MDD[47]. Studies suggest that abnormal FFG activity and functional connectivity may play an important role in the development of adolescent MDD and suicide attempts. For instance, elevated ALFF in the right FFG was observed in MDD adolescents with suicide attempts[48], while Pan et al[49] reported significantly lower activity in the left FFG of depressed adolescents with suicide attempts than in depressed adolescents without suicide attempts during an emotional processing task. Additionally, Sacu et al[50] demonstrated reduced effective connectivity from the left amygdala to the right FFG in adult MDD patients, and adolescents with a family history of MDD showed similar diminished functional connectivity from the amygdala to the FFG[51]. Collectively, these results align with our findings, suggesting that disrupted amygdala-FFG connectivity may impair emotion perception and facial recognition in MDD.

Our findings revealed reduced rsFC between the bilateral LA, left MeA, and left THA in the sMDD group compared to HCs. The THA, a critical relay hub in the brain, mediates sensory-motor signal transmission and regulates emotion, cognition, and behavioral control[52]. Emotional stimuli are relayed to the amygdala via thalamic pathways[53], and thalamic dysfunction may impair this process. Prior meta-analyses of fMRI studies in adolescent MDD have demonstrated abnormal THA activation during emotional tasks[54]. Wang et al[55] reported diminished regional homogeneity in the right THA of suicidal MDD patients. Notably, abnormal functional connectivity between the THA and the amygdala plays an important role in emotion regulation[56]. An fMRI study showed[57] that the rsFC value between the right medial central amygdala and THA was reduced in patients with MDD compared to healthy subjects, which supports our findings. We hypothesize that attenuated amygdala-THA connectivity compromises the integration of negative emotional stimuli, impairing emotion regulation and exacerbating depressive symptoms.

We also found that the rsFC of the right MeA and right TPOsup was lower in the sMDD group than in the HC group. The temporal pole occupies the most anterior portion of the temporal lobe and is associated with higher cognitive processes, with the right temporal pole primarily implicated in emotional processing, social behavior, and situational memory[58]. The STG, a core cortical region of the social brain, integrates sensory information and contributes to social cognition[59]. Sun et al[60] identified reduced rsFC between the right amygdala and right STG in patients with alcohol-dependent MDD. One study[61] reported that BOLD signaling stability in the right TPOsup was significantly reduced in the MDD group compared to the HC group. Furthermore, structural neuroimaging studies revealed significantly decreased gray matter density in the bilateral temporal pole and right STG in MDD patients relative to HCs[62]. Previous studies[63] have demonstrated that adolescents with low self-esteem exhibit an increased susceptibility to developing depression. In the present study, the rsFC values of the right MeA and right TPOsup demonstrated a negative correlation with RSES scores, suggesting that abnormalities in this neural circuit may be related to the patients' impaired self-esteem. In conclusion, alterations in functional connectivity between the right MeA and right TPOsup may represent neural correlates of abnormalities in emotional processing and social cognition associated with MDD.

CONCLUSION

There are some limitations in the present study. First, cross-sectional designs cannot establish a causal relationship between rsFC abnormalities in amygdala subregions and depressive symptoms or suicidal behavior, making it difficult to understand how changes in functional connectivity in the relevant brain regions affect an individual's mood over time, as well as the specific relationship between these changes and suicidal behavior. Second, we found abnormal functional connectivity between the amygdala subregion and the whole brain through rsFC analysis, but the study's analytic method was relatively homogeneous. Future research may expand analytical methods, such as structural MRI and task-based fMRI, to conduct multimodal analyses, thereby enhancing the comprehensiveness and interpretability of research findings. Given the small sample size, although significant intergroup differences were observed, future multi-center, large-scale studies are needed to validate the reliability of these findings.

A key finding in the present study was that the sMDD group, relative to the nsMDD group, exhibited distinct functional connectivity patterns between the right LA and both the right IOG and left MOG. Additionally, the rsFC value between the right MeA and right TPO sup showed a negative correlation with RSES scores, while the rsFC value between the left LA and right PHG showed a positive correlation with interpersonal relationship scores on the ASLEC. Abnormal functional connectivity changes between the amygdala subregion and these brain regions may constitute a potential neural mechanism for suicide attempts in adolescents with MDD. Future studies may incorporate multimodal neuroimaging techniques to further explore the neurocircuitry underlying suicide behavior in adolescent MDD patients and provide a scientific basis for suicide risk assessment and early intervention in adolescent MDD patients.