INTRODUCTION

Hepatobiliary cancers like hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder cancer and pancreatic cancers are the most lethal malignancies worldwide, causing a disproportionate amount of malignancy[1]. These malignancies are usually diagnosed at terminal or advanced stages, leaving patients with limited treatment options. Despite improvements in surgical resection, palliative care and systemic therapies, the rate of survival is still poor, especially for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, where the chance of surviving 5 years is over 20%[2]. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancers cause severe and heterogeneous physical symptoms, such as abdominal pain, fatigue, obstructive jaundice and gastrointestinal dysfunction. These significantly impair daily functioning and intensify psychological morbidity. For instance, obstructive jaundice can cause visible yellowing of the skin and eyes, contributing to body image concerns and social isolation, while rapid weight loss causes profound demoralization. These physical symptoms create a shared path between physical and mental suffering. However, mental health in these malignancies remains underrecognized and undertreated. Beyond general oncological distress, hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies manifest distinct disease-specific psychological challenges that exacerbate emotional suffering[3]. These malignancies are characterized by rapid onset, poor prognosis and late-stage diagnosis, all of which generate severe existential anxiety, demoralization and loss of control. Biological processes, such as cytokine-driven neuroinflammation and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation intensify depressive symptoms, differentiating these malignancies from other solid tumors. Moreover, pancreatic malignancy patients frequently suffer from prodromal depression even before diagnosis, indicating a connection between mood dysregulation and tumor biology. In cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular patients, severe hepatic dysfunction causes cognitive slowing, fatigue and social withdrawal, resulting in cumulative psychological distress. Therefore, tailored psycho-oncology frameworks are essential to detect these disease-specific stressors rather than extrapolating from generic cancer models. Many depressed individuals experience suicidal thoughts, while the majority of those are either undiagnosed or not treated[4-6].

Patients with hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies face a clinical trajectory that makes the need for integrated mental health support especially critical. Compared to many other cancers, these malignancies have poor survival rates, a remarkably high symptom burden and rapid progression. These factors lead to disproportionately high rates of depression, anxiety and demoralization, which are consistently reported as the highest across all cancer types. Families also suffer from anticipatory grief earlier, given the shortened disease course. For these facts, systematic integrated approaches, such as routine psychological screening, timely intervention and caregiver support are particularly suited to this patient cohort, where both psychological and physical issues often unfold in parallel[6]. A recent study by Yu et al[7] reported that anxiety was detected in 62.5% of patients in the early-stage of the disease and increased to 82.7% in mid-stage disease, while depression went from 66.7% to 92.3%, compared to only 10% and 8% in normal controls. These findings show that psychological morbidity is not coincidental but strongly correlated with disease progression, underscoring the necessity for early comprehensive screening and prompt action. As the disease worsens and patients need to navigate the shift from active treatment to palliative care, the psychological effects intensify. Caregivers, usually family members, also suffer from severe anxiety, stress and depression as they manage complex treatment regimens, critical decision-making responsibilities and medical emergencies[8]. These untreated mental distresses negatively affect treatment adherence, symptom insight, and lifestyle quality and survival outcomes. Evidence-based interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, have shown results as effective supportive approaches[9]. This study emphasizes the significance of mental health screening and therapies in oncology care to improve disease outcomes and the psychological health of the patients.

FRAMING THE OVERLOOKED BURDEN

Psychological distress in hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies is often neglected despite compelling evidence that patients with these malignancies experience the highest levels of psychological turmoil among all cancer individuals. Studies found that, 20%-30% of cancer patients suffer from a higher level of psychological distress than average, which causes a great impact on prognosis and eventually leads to poor prognosis[10]. Depression, anxiety, demoralization, existential dread and post-traumatic stress-related symptoms are all aspects of the multifaceted term of distress, which interplay to break down patients' coping strength and resilience[10]. These conditions reduce adherence to therapy plans, lower postoperative results, weaken patients’ determination to take treatment and elevate the chance of committing suicide. Research found that, among 63.7% of cancer patients with psychological distress, there were almost 49.4% of pancreatic and 30.5% of hepatobiliary cancer patients and these numbers are higher than psychiatric patients with other malignancies due to the rapid movement and slower progression of pancreatic and hepatobiliary malignancies[11].

To analyze these challenges more systematically, Yu et al[7] used validated psychometric tools to evaluate emotional burden in patients with hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancer. The Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, consisting of twenty items on a 4-point Likert scale, identifies the intensity of anxiety symptoms. Scores above 50 suggest clinically significant anxiety, with higher values denoting elevated severity. The Self-Rating Depression Scale, also a twenty-item self-report tool, assesses psychoemotional signs, psychomotor impairments and somatic signs, a score of 53 or higher suggests depression. Similarly, the Life Event Scale was utilized to measure life events in various categories such as major disruptive incidents, neutral events and negative experiences. This integration allowed not only the identification of anxiety and depression but also the detection of external psychosocial factors like financial strain, social isolation, adverse effects of treatment and poor self-care. The application of these tools obtained critical information: Self-Rating Anxiety Scale and Self-Rating Depression Scale scores were significantly higher in intermediate-stage (IIA-IIIA) patients (56.82 ± 2.18 and 60.05 ± 4.83, respectively) compared to early-stage patients and normal controls (P < 0.05). Additionally, the Life Event Scale score was noticeably elevated in the observation group, ensuring that life event stressors exacerbate the emotional burden as the disease progresses[7].

Furthermore, patients can feel pressured by cultural and familial traditions to look optimistic, this can lead them to hide their existential anxiety or depression and delay acknowledging their needs for mental health[12]. The stigma associated with mental health in oncology is combined with inadequate training of clinicians and lack of resources, which causes systemic underdiagnosis[13]. The psychological distress is commonly stated as a normal response in cancer patients instead of detecting it as a curable condition that requires help and this normalization leads to lost chances for timely psychological care[6]. The paradigm of malignancy care needs to change to address this overlooked burden. Clinicians need to recognize the interplay of mental and physical health instead of ignoring it. Approaches, such as early mental health screening at diagnosis, including psycho-oncologists in integrative groups and institutional initiatives to eliminate mental stress. By establishing mental health care within hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancy, healthcare systems may ensure distress is understood and treated, which will improve adherence, decrease hospital resource use and ultimately will improve survival and life quality[14]. In addition to clinical under recognition, psychological therapy for hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies is significantly influenced by cultural and geographical factors. Low-income and middle-income settings frequently lack trained psycho-oncologists and operate under fragmented referral pathways, causing substantial disparities in access. Further suppressing psychological health help-seeking among patients and caregivers are cultural ideologies that promote stoicism or restrict emotional disclosure, particularly in South and East Asian countries[12]. Studies conducted in cross-regional oncology settings show that the stigma associated with psychiatric consultation is a major deterrent to early distress screening. Consequently, integrative psycho-oncology models need to be culturally adapted, employing family-inclusive counseling, community-based psychological health education and telepsychiatry platforms. This contextually sensitive adaptation confirms that evidence-based care remains both globally feasible and ethically inclusive[10].

EARLY-STAGE DIAGNOSIS: SHOCK AND UNCERTAINTY

When someone is diagnosed with hepatobiliary or pancreatic malignancy, the moment is usually devastating with extreme emotional turbulence. All of a sudden, patients are separated from their everyday lives into a world of medical jargon and emergency treatment decisions. The initial reaction is usually severe shock, disbelief and numbness. This gives a maelstrom of emotions, such as anxiety about the future, grief over the loss of normalcy and health. Their thoughts are filled with worries about the efficacy of therapies, suffering and the impact on their families and finances, these disable them and cause significant distress connected to diagnosis. Study shows that even at the early stage (IA-IB), 62.50% of patients suffer clinical anxiety and around 66.67% patients experience depression, indicating that psychological distress starts immediately upon diagnosis rather than developing later in the disease course[7]. Intervention is essential during this severe distress period. It is important to diagnose psychological distress on time and communicate clearly with the physician. The way of presenting information can have a significant impact on how efficiently a patient adapts psychologically. Approaches like the Setting, Perception, Invitation, Knowledge, Empathy, and Strategy/Summary protocol give a framework for conveying devastating news in a way that encourages understanding and a relationship with therapies[15]. Early mental support, such as counselling or a recommendation to a psycho-oncologist should be established, instead of providing an afterthought. Patients who take cognitive-behavioral therapy methods might benefit immediately by acquiring relaxation techniques to manage severe anxiety, detecting and fighting a catastrophic way of thinking and improving their ability to solve problems[16]. By providing early psychological health aid, it is destigmatized and treated as an important aspect of comprehensive cancer care, so it prepares the patient for future challenges instead of letting psychological complications worsen[17].

TREATMENT PHASE: COPING WITH PHYSICAL AND MENTAL STRAIN

Hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies possess an extended therapeutic phase, which is exhausting for both mental and physical health. Interventions are strong and have severe adverse effects that significantly influence the quality of life. Major surgical procedures, like pancreaticoduodenectomy or hepatectomy, include extensive operations, long hospitalization and an exhaustive healing process, which carries a high risk of difficulties such as infection, late gastric emptying or pancreatic fistula[18]. During pre-operative time, the anxiety level remains high and focused on enduring the actual surgical procedure, whereas the postoperative period can lead to depression connected to diminished independence, altered body shape and frustration with the slow rate of recovery process[19]. Various type of psychological challenges occurs with systemic treatments like targeted therapy, radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Patients endure a never-ending cycle of medication, recovery and side effects like nausea, neuropathy and severe fatigue, frequently during months on end. Malignancy-linked cognitive dysfunction can trigger frustration and a loss of self-identification[20]. The fear that the medication is not functioning properly is a major and prevalent reason of anxiety during this period. Between scans, patients experience an increased level of distress, hypervigilance about physical sensations and perceiving every pain as a warning of progression[21]. Report by Yu et al[7] demonstrates that treatment-linked psychological burdens intensify efficiently during intermediate disease stages (IIA-IIIA), with 78.85% of patients confirming treatment adverse effects as a significant stressor compared to 62.50% patients at early-stage, while poor self-care capability impacts 63.46% vs 31.25% in earlier stages. Decreasing this multidimensional burden needed a strong multidisciplinary team methodology. This multidisciplinary team is required to consist of specific support services along with radiologists, surgeons and medical oncologists. Cancer-specialized psychiatrists or psychologists can provide evidence-based treatments. When implemented early, instead of only at the end of life, palliative caregivers are skilled in treating severe physical symptoms like nausea and pain, which effectively alleviates a major cause of psychological distress[22]. Dietitians are important for managing and preventing cachexia, a major issue that impacts both mental and physical health. Social workers can help with financial and logistical stresses. This comprehensive care model confirms that the patient gets assistance at every stage, making the difficult treatment procedure easier to manage and decreasing the chances of getting late treatment or discontinuation because of undiagnosed psychosocial issues[23].

ADVANCED-STAGE AND PALLIATIVE CARE: EXISTENTIAL ANXIETY

When disease progression reaches the advanced or metastatic stage then the psychological condition changes dramatically. The concentration moves from healing to life extension and quality of life, allowing patients to face their death directly. The incidence of major depressive disorder and severe anxiety is commonly high during this stage[5]. Whenever patients suffer from the lack of future goals, the inability to perform civic duties and the awareness of approaching death, on that moment they usually face the emotion of despair, feeling worthless and depression. The physical strain also causes severe exhaustion, increased pain, ascites and bowel obstructions; each of these symptoms contributes to an endless cycle of mental distress[24]. At this point, the palliative psychiatry integration is not only beneficial but also essential. Palliative care manages the interface of palliative medicine and psychiatry, concentrating on the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric symptoms in patients with severe and terminal illnesses like cancer[7]. For patients who may have impaired metabolism due to liver dysfunction or cachexia, this involves the expert use of psychotropic medications like anxiolytics for acute anxiety and antidepressants for mood. Furthermore, psychotherapy has shown effectiveness by assisting patients in identifying a purpose despite their terminal illness, which reduces existential distress[25]. Spiritual care is another important aspect but it is usually overlooked. Existential anxiety questions about “Why me?” fear of what will happen after death and emotions of guilt or abandonment, these are mainly experienced by patients with an advanced stage of cancer. Certified psychologist with interdisciplinary support training can provide patients and families invaluable secular counseling to assist them go through these difficult complications, facilitating peace, forgiveness and reconciliation[26].

CAREGIVER BURDEN: THE INVISIBLE PATIENT

Hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies create an immense burden on the patient as well as their caregivers, such as spouses, friends or adult children. Caregivers are usually referred to as “invisible patients”, as they are placed into roles for which they are not prepared, like nursing, managing financial affairs, being an emotional supporter and care coordinator. These responsibilities are relentless, which leads to extremely high rates of depression, burnout, anxiety and compassion fatigue. As their world collapses to the boundaries of caregiving, they usually overlook their own health, miss their regular medications or appointments and suffer from insomnia and loneliness. They experience multifaceted mental issues, as they see their loved one’s health fall apart then they suffer from anticipatory despair. They feel very helpless, when they cannot help them to reduce their suffering. They keep their fears and anxieties inside themselves because they think that they need to be strong and positive for the patient, thus denying their own emotional storm. The financial burden associated with cancer care, it includes additional expenses and decreased income due to fewer working hours, which adds extreme stress that may have lifetime effects on the caregiver’s financial stability[27]. To provide comprehensive malignancy care, it is important to identify caregiver burden as a preventable contributor to risk. Healthcare providers need to implement routine screening for caregivers’ mental distress along with the patient screening. Support programs may also be effective, such as individual counseling to control anxiety and depression, peer support teams to whom caregivers can express their experiences and decrease the feelings of loneliness and psychoeducational teams, who instruct helpful caregiving skills and what can be expected from the malignant trajectory. Another essential but neglected resource is respite care services, which give temporary relaxation from the responsibilities of caregiving. Caregivers who get active support, they can provide higher quality care for increased periods, thereby decreasing or avoiding hospitalization and can improve patients’ quality of life, the healthcare team contributes indirectly to patients by doing these[8].

BRIDGING THE CLINICAL GAP

The significant gap between the low rates of systemic diagnosis and intervention and the high incidence rate of mental distress is an ongoing concern throughout all phases of disease. Research found that despite anxiety affecting 82.69% and depression impacting 92.31% of intermediate-stage patients, these conditions are substantially untreated or underdiagnosed in clinical oncology practice[7]. To bridge this gap, clinical practice needs to fundamentally alter to the routine involvement of mental health care. The initial and most essential step is to employ verified standardized screening techniques at all important clinical stages, such as diagnosis, the beginning of a new therapy line, progression and transition to palliative care[14]. Ultra-short and significant tools, such as the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for depression and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale can be simply incorporated into nursing intake processes or patient portals to detect patients who need further evaluation[28]. However, screening is meaningless without a clearly established referral procedure. Even after being on the front line of treatment, oncologists, surgeons and hepatologists frequently feel unable to manage severe mental conditions. This emphasizes the second requirement, which is to ensure that the entire hepatobiliary and pancreatic oncology team receives specialized training. This training will focus on increasing communication skills for counselling prognosis and psychological concerns; this will develop the skill to detect the clinical symptoms of depression and anxiety and will help to reduce the stigma linked with referrals for mental health[29]. The most impactful method for bridging this gap is the simultaneous presence of mental health specialists within the oncology practice. Integrating a clinical psychiatrist, psychologist or psychiatric nurse practitioner in the multidisciplinary care team will reduce the obstacles to access, normalize psychological health care as part of treatment for malignancy and will improve comfortable transitions and continuous communication between the patient’s physical and mental health treating professionals[30].

CALL TO ACTION

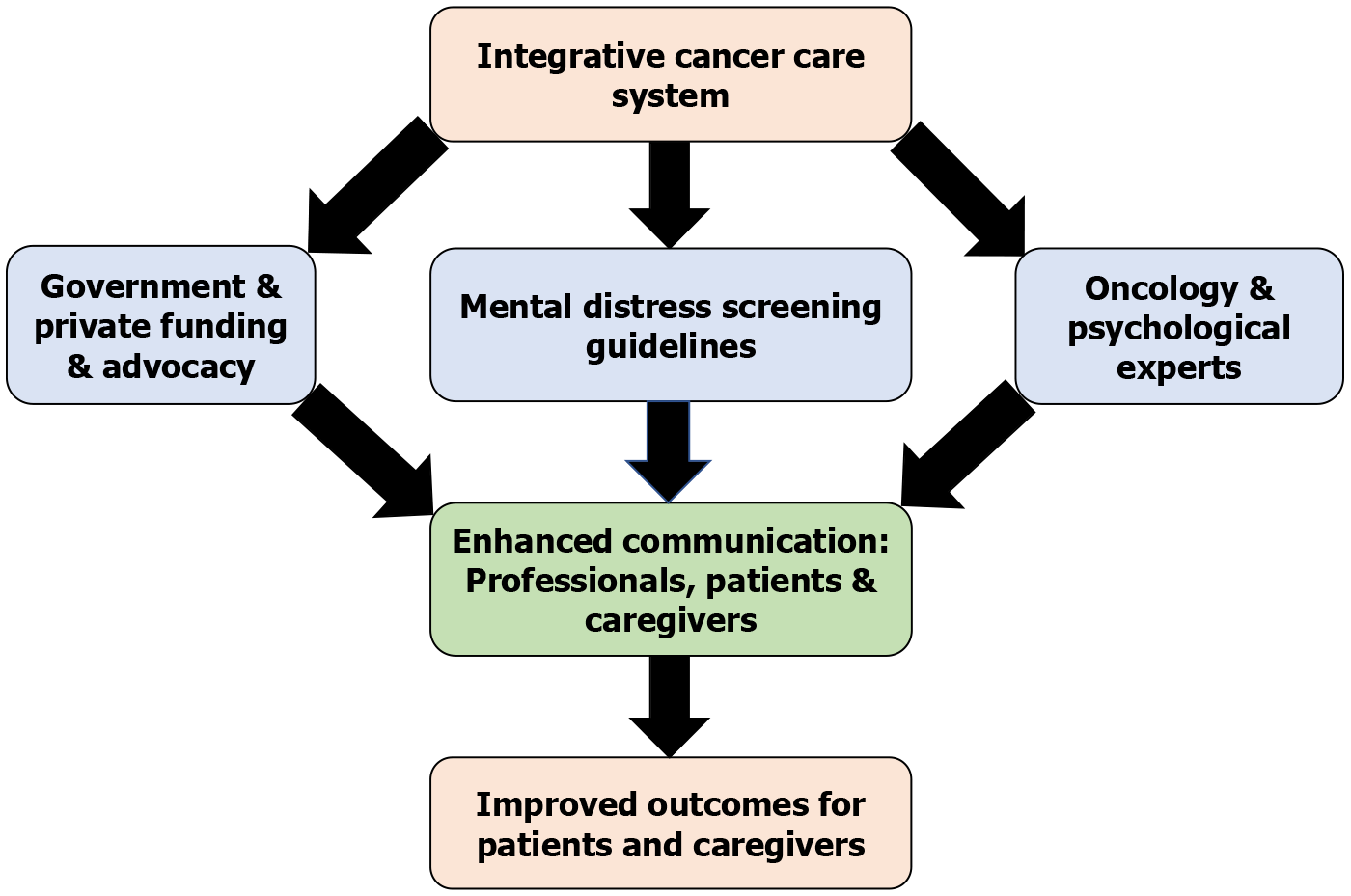

To address the hidden pandemic of anxiety and depression in hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancy treatment need for an integrated, evidence-based strategy that goes beyond the individual practitioner’s initiative to structural and policy-level implementation. Figure 1 illustrates the systematic model of an integrative cancer care system, emphasizing the roles of private and government funding, mental distress screening guidelines, psycho-oncology experts and the importance of enhanced communication among professionals, patients and caregivers to improve patient outcomes. This call to action’s initial pillar is that healthcare administration and cancer care leadership must formally detect psycho-oncology as an essential component of care rather than an additional service. To ensure this, dedicated funding must be allocated to establish, staff and sustain coordinated psychological support programs based on properly defined scientific protocols, assuring that psychological healthcare providers are core contributors of the clinical team and multidisciplinary cancer care[30].

Figure 1 Systematic model of the integrative cancer care system.

This model illustrates the interrelated elements of an integrative psycho-oncology paradigm for hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies. It highlights how structured distress screening, multidisciplinary cooperation between oncology and psychological specialists and coordinated governmental and private support improve communication among patients, caregivers and healthcare professionals, thereby improving treatment adherence and enhancing clinical and psychosocial outcomes.

Secondly, guidelines should be scientifically updated and standardized by professional cancer organizations, such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Rather than only suggesting screening, these guidelines should mandate routine mental health screening using validated tools like Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 or Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale at critical clinical objectives, such as therapy initiation, disease progression and transfer to palliative care. To ensure timely intervention and early detection, implementation methods should be designed to be measurable, reproducible and adaptable to a variety of clinical settings. Accrediting authorities can further support this by making integrated psychological treatment a criterion for high-quality cancer care certification[31]. Third, funding is needed for the research and advocacy. The belief that integrative therapy will treat the soul and mind with the exact urgency as the body and this is a right, not just a privilege, the patient advocacy team must promote this belief. Government and commercial funding agencies should prioritize research grants focused on creating and assessing innovative psychosocial therapies, particularly suited to each problem faced by patients with hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancy and their caregivers. Research initiatives ought to prioritize scientific methodology, showing efficacy and cost-benefit analyses, like an initial investment in psychological healthcare support can minimize the subsequent healthcare expenses by lowering emergency department visits, prolonged hospital admissions and inability to adhere to costly cancer treatments[32]. Funding and policy support are essential, but a practical knowledge of implementation science is required for translation into sustainable clinical practice. Major barriers, such as insufficient institutional infrastructure, limited psycho-oncology workforce capacity, irregular referral protocols and competing clinical priorities[30]. To address these challenges, a phased approach should be adopted, such as integration of psycho-oncology services in tertiary cancer centers as a pilot project to show cost-effectiveness and feasibility, implementing structured training modules for oncologists and nurses that highlight communication skills and distress-management approaches, incorporating digital psychological health platforms and telepsychiatry to reach remote patients and implementing an iterative assessment using measurable outcome detectors like caregiver well-being indices, adherence rates and patient-reported distress scores. Multisectoral cooperation that includes governmental organizations, non-governmental organizations and academic institutions can further develop sustainability and ensure equitable scale-up of the model across different healthcare systems[14]. Finally, potential implementation challenges, such as institutional resistance, workforce constraints and variability in healthcare infrastructure need to be anticipated and handled systematically. Suggested strategies may require adaptation according to variations in healthcare systems, economies and cultural perspectives toward mental health across regions and countries, assuring the model is practically feasible and globally relevant[10].

CONCLUSION

The journey of dealing with hepatobiliary or pancreatic malignancy is one of the most difficult paths a person can endure, which includes complicated medical challenges, severe physical symptoms and profound psychological distress. This article highlights the various mental health issues that arise during each stage of this journey, from the devastating effect of diagnosis through the difficult treatment and toward the fundamental realm of advanced illness and it also describes the simultaneous suffering of the caregivers who walk beside them. Studies demonstrate that psychological distress is not constant but increases significantly with disease progression, with anxiety rates rising from 62.50% to 82.69% within the same phase, while depression increases from 66.67% in early-stage disease to 92.31% in later-stage disease. The high rate of incidence of mental distress is not an untreatable adverse effect, it is an anticipated condition that requires a proactive, systemic and scientifically guided approach. To efficiently overcome this neglected pandemic, healthcare systems must implement routine mental health screening, integrate psycho-oncology professionals within multidisciplinary teams and provide support for caregivers. Policies should establish the role of mental health in oncology care, like standardized training programs, institutional guidelines and specialized funding. Furthermore, implementation approaches should consider potential barriers, like resource constraints and regional variations in healthcare infrastructure, economic circumstances and cultural norms, to ensure adaptability and feasibility across different settings. Research and advocacy should prioritize on innovative psychosocial interventions, showing both cost-effectiveness and clinical efficacy. Future implementation should also account for health-system integration and real-world feasibility. Evidence from large-scale cancer programs have shown that incorporating psycho-oncology protocols within standardized distress screening processes, electronic medical histories and multidisciplinary tumor boards efficiently improves patient satisfaction and compliance. Moreover, expanding these frameworks to primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare levels can enhance access to psychological health resources for all. Sustained monitoring and assessment informed by patient-reported outcome measures and longitudinal quality-of-life indices, will ensure accountability and continuous model refinement. This methodical integration develops the translation of psycho-oncological science into quantifiable impacts on public-health. By implementing these recommendations into action, cancer care can shift from reactive symptom management to a holistic, patient and family-centered model, improving quality of life, treatment adherence and survival rates. Incorporating scientifically guided psychological care beside physical treatment assures that both patients and caregivers are getting holistic support, regardless of systemic and geographic limitations.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country of origin: Bangladesh

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Novelty: Grade C, Grade C, Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade C, Grade C, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade C, Grade C, Grade C

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: Li YF, Associate Professor, China; Perez-Campos E, PhD, Professor, Mexico S-Editor: Zuo Q L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang CH