Published online Jan 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i1.113104

Revised: October 21, 2025

Accepted: December 3, 2025

Published online: January 19, 2026

Processing time: 105 Days and 21.1 Hours

Ischemic stroke is one of the leading global causes of disability and death. Despite advances in modern medical technology that improve acute treatment and re

To systematically evaluate risk factors and early identification markers for PSD for more precise screening and intervention strategies in clinical practice.

This retrospective study analyzed clinical data from 112 patients with ischemic stroke admitted between January 2022 and December 2024. Based on assessments using the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAMA) and Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD) at 2 weeks (± 3 days) post-stroke, patients were classified into the PSD group (HAMA ≥ 7 and/or HAMD ≥ 7) and the non-PSD group (HAMA < 7 and HAMD < 7). Observation indicators included psychological assessment, demographic and clinical characteristics, stroke-related clinical indi

Of the 112 patients, 46 (41.1%) were diagnosed with PSD. Multivariate analysis identified five independent risk factors: Female gender [Odds ratio (OR) = 2.32, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.56-3.45], history of mental disorders prior to stroke (OR = 3.17, 95%CI: 1.89-5.32), infarct location in the frontal lobe or limbic system (OR = 2.86, 95%CI: 1.73-4.71), stroke severity with National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale ≥ 8 at admission (OR = 2.54, 95%CI: 1.62-3.99), and low social support (Social Support Rating Scale < 35, OR = 2.18, 95%CI: 1.42-3.36). Subgroup analysis showed that depression patients more commonly had left hemisphere lesions (68.4% vs 45.2%), while anxiety patients more frequently presented with right hemisphere lesions (59.5% vs 39.5%). The PSD group exhibited larger infarct volumes (8.7 cm3vs 5.3 cm3), more severe white matter hyperintensities, and more pronounced frontal lobe atrophy. Analysis of inflammatory markers showed significantly elevated levels of interleukin-6 (7.8 pg/mL vs 4.5 pg/mL) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (15.6 pg/mL vs 9.8 pg/mL) in the PSD group, while hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function assessment revealed higher cortisol levels (386.5 ± 92.3 nmol/L vs 328.7 ± 75.6 nmol/L) and flattened diurnal rhythm in the PSD group.

PSD is a complex neuropsychiatric consequence of stroke involving disruption of the frontal-limbic circuitry, neuroinflammatory responses, and dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

Core Tip: Post-stroke anxiety and depression are common but underrecognized complications after ischemic stroke, adversely affecting recovery and prognosis. This study integrates demographic, clinical, neuroimaging, inflammatory, and neuroendocrine indicators to identify independent risk factors and early biomarkers for post-stroke anxiety and depression. Female gender, prior mental disorders, frontal-limbic infarcts, severe stroke, and low social support were key predictors. Elevated interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and cortisol, alongside reduced insulin-like growth factor-1, showed strong diagnostic value, providing a multidimensional framework for early screening and targeted intervention in high-risk patients.

- Citation: Zhao JD, Qiu SW, Lin KY, Lin HY, Yu CW. Risk factors and early identification markers for post-ischemic stroke anxiety and depression. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(1): 113104

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i1/113104.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i1.113104

Ischemic stroke is a common neurological disease and one of the leading causes of disability and death globally. With advances in modern medical technology, acute treatment and rehabilitation measures for ischemic stroke have continuously improved, significantly increasing patient survival rates. However, post-stroke neuropsychiatric complications, especially anxiety and depression, do not receive sufficient attention[1-3]. Research indicates that approximately 30%-50% of patients with ischemic stroke develop symptoms of anxiety and depression, which not only seriously affect patients’ rehabilitation progress and treatment adherence but are also closely associated with longer hospital stays, higher risk of recurrence, and mortality[4,5]. The etiology of post-stroke anxiety and depression (PSD) is complex and may involve multiple factors related to neuroanatomy, neurobiochemistry, and psychosocial aspects. Brain vascular events causing damage to specific brain regions and related neurotransmitter systems, such as disruption of the frontal-limbic system circuit and dysfunction of monoamine neurotransmitters, form the biological basis for PSD[4-6]. Simultaneously, psychosocial stressors that patients face, including sudden illness, loss of function, uncertainty about the future, and changes in social support, further exacerbate the occurrence and development of anxiety and depressive emotions.

There is generally a delay in the clinical identification and intervention of PSD. On one hand, this is because its symptoms are often misidentified as manifestations of the stroke itself or normal reactions during the recovery process; on the other hand, cognitive impairment and language disorders, common in stroke patients, increase the difficulty of assessing anxiety and depression[7-9]. Therefore, identifying high-risk populations for PSD and establishing early identification marker systems are important for early intervention and improving prognosis. Although previous studies have explored some PSD-associated risk factors, such as gender, age, stroke severity, and history of psychiatric disorders, most research has focused on analyzing single risk factors and lack systematic and comprehensive risk assessment models[8,9]. With the recent development of molecular biology and neuroimaging, potential biomarkers such as inflammatory factors, neurotrophic factors, neuroendocrine hormones, and changes in functional connectivity of specific brain regions have begun to receive attention[10,11]. However, their clinical application value in the early identification of PSD requires further validation.

Through a retrospective analysis of 112 ischemic stroke patients, this study systematically evaluated the relationships between demographic characteristics, stroke-related clinical indicators, imaging features, serum biomarkers, and the occurrence of PSD. It aims to construct a multidimensional risk assessment system and explore early identification markers with high sensitivity and specificity, providing more precise screening and intervention strategies for clinical practice, ultimately improving the psychological health status and quality of life of ischemic stroke patients. In-depth understanding of risk factors and early identification markers for PSD not only helps clinicians identify high-risk patients early and provide targeted interventions but also provides a scientific basis for further exploration of the pathogenesis and individualized treatment strategies for PSD. This has important clinical significance and social value for improving the overall rehabilitation outcomes and long-term quality of life for stroke patients.

This retrospective study analyzed clinical data from patients with ischemic stroke admitted to the Department of Neurology at our hospital from January 2022 to December 2024. Patients meeting the inclusion criteria of age ≥ 18 years, diagnosis of ischemic stroke confirmed by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), time from stroke onset to admission ≤ 7 days, ability to complete neuropsychological assessment, and who provided informed consent were enrolled in the study. We excluded patients with history of severe psychiatric disorders requiring hospitalization before stroke, severe aphasia, cognitive impairment (Mini-Mental State Examination score < 20), consciousness disorders preventing reliable assessment, other neurological diseases potentially affecting mental state, severe systemic diseases with life expectancy < 6 months, use of medications known to significantly affect mood within 1 month before admission, and patients with transient ischemic attack without evidence of infarction on imaging.

Patients were assessed for anxiety and depression at 2 weeks (± 3 days) post-stroke using the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAMA) and Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD). Based on these standardized assessment tools, patients were classified into two groups: The PSD group (HAMA score ≥ 7 and/or HAMD score ≥ 7) and the non-PSD group (HAMA score < 7 and HAMD score < 7). The PSD group represented patients who developed anxiety and/or depression following ischemic stroke, while the non-PSD group served as the control for comparison.

Psychological assessment: At 2 weeks post-stroke, participants completed a battery of validated measures specific to psychological health. The 17-item HAMD was used to evaluate depressive symptoms. The addition of scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, a 17-item clinician-rated scale that assesses depression severity with questions about mood, guilty feelings, suicidal ideas, sleep disturbances, anxiety, and somatic symptoms. The score is calculated as a total of each item and ranges from 0 to 52, which was measured on a 3-point or 5-point scale. A score of 7-16 reflects mild depression, 17-23 developed depression, and ≥ 24 severe depression. The HAMA was used to assess anxiety symptoms. The 14-item scale measures both psychic (mental agitation, psychological distress) and somatic anxiety (physical complaints related to anxiety symptoms). Scores range from 0 to 56, with each item scored from 0 (none) to 4 (severe). Mild, moderate, and severe anxiety correspond to scores of 7-13, 14-20, and ≥ 21, respectively.

Other psychological measures: The Post-Stroke Depression Rating Scale, a scale specifically validated for the detection and assessment of depressive symptoms in stroke patients, which considers somatic symptoms, physical functioning, and confidence, was performed as a supplementary measure. The Beck Anxiety Inventory was utilized to support the HAMA and provide a self-reported patient measure of anxiety severity. Perceived social support that may have an effect on PSD occurrence was assessed using the Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS) on admission. The scale measures three dim

Demographic information, including age, gender, education level, marital status, and residence (urban/rural), was collected through patient interviews and medical records. Medical history comprising hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, coronary heart disease, previous stroke, and a history of mental disorders was documented. Lifestyle factors such as smoking (defined as smoking > 1 cigarette daily for > 1 year), alcohol consumption (defined as drinking > 50 g of alcohol daily for men or > 25 g for women for > 1 year), and physical activity (assessed by the International Phy

Stroke severity was assessed using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) at admission, with higher scores indicating more severe neurological deficits. Stroke location was classified based on imaging findings into frontal lobe, temporal lobe, parietal lobe, occipital lobe, basal ganglia, thalamus, cerebellum, brainstem, or multiple locations. Particular attention was paid to lesions in the frontal lobe and limbic system, given their established role in mood regulation. Stroke etiology was classified according to the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment criteria into large-artery atherosclerosis, cardioembolism, small-vessel occlusion, stroke of other determined etiology, and stroke of undetermined etiology. Functional status was evaluated using the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) and Barthel Index (BI) at 2 weeks post-stroke, with mRS measuring global disability [scores ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (death)] and BI assessing activities of daily living [scores ranging from 0 (completely dependent) to 100 (fully independent)].

All patients underwent brain CT or MRI scanning at admission. Infarct volume was calculated using the ABC/2 method for CT or semi-automated segmentation for MRI. White matter hyperintensities were graded using the Fazekas scale, with periventricular and deep white matter lesions scored separately from 0 to 3 (0 = absent, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe). Brain atrophy was assessed using visual rating scales, considering both global atrophy and regional atrophy patterns. Microbleeds were counted and localized when available from susceptibility-weighted imaging. Specific attention was given to lesions in mood-regulating neural circuits, including the prefrontal-subcortical circuit and the limbic system. Advanced diffusion-weighted imaging parameters, including apparent diffusion coefficient, were measured to assess tissue microstructural integrity, as altered water diffusion may reflect cellular damage affecting emotional regulatory circuits. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI perfusion parameters (wash-in rate, time to peak, wash-out rate) were obtained in a subset of patients to evaluate cerebrovascular hemodynamics, given emerging evidence that impaired neurovascular coupling and reduced metabolic support may contribute to mood dysregulation following stroke.

Blood samples were collected from all participants in the morning (7:00-9:00 AM) after overnight fasting at 2 weeks post-stroke. Inflammatory markers, including high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), were measured given their potential role in neuroinflammation associated with mood disorders. Neurotrophic factors such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) were assessed due to their involvement in neuroplasticity and mood regulation. Neuroendocrine indicators, including cortisol, adrenocorticotropic hormone, and 24-hour urinary free cortisol, were measured to evaluate hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis function, which is often dysregulated in mood disorders. Additionally, routine blood tests and biochemical indicators, including complete blood count, liver and kidney function tests, lipid profile, blood glucose, and glycosylated hemoglobin, were performed to assess general health status and potential confounding factors.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) and R software version 4.0.3. Normally distributed continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD and compared using Student’s t-test. Non-normally distributed continuous variables were presented as median [interquartile range (IQR)] and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were presented as n (%) and compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. To identify independent risk factors for PSD, variables with P < 0.1 in univariate analysis were included in multivariate logistic regression analysis using a forward stepwise method. Results were expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The diagnostic value of potential biomarkers for PSD was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. Correlations between continuous variables were assessed using Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation coefficient as appropriate. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 112 patients with ischemic stroke met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in this study. Based on the HAMA and HAMD assessment at 2 weeks post-stroke, 46 patients (41.1%) were diagnosed with post-stroke anxiety and/or depression (PSD group), while 66 patients (58.9%) showed no significant anxiety or depression symptoms (Non-PSD group). In the PSD group, 14 patients (12.5%) had depression only, 15 patients (13.4%) had anxiety only, and 17 patients (15.2%) presented with comorbid anxiety and depression. The demographic analysis revealed several significant differences between groups. Patients in the PSD group were more likely to be female (56.5% vs 39.4%, P = 0.003), had higher rates of history of mental disorders (17.4% vs 6.1%, P < 0.001), and reported lower levels of social support as measured by SSRS (31.6 ± 7.7 vs 38.8 ± 8.6, P < 0.001). These findings highlight the potential role of gender, psychiatric history, and social support systems in the development of post-stroke psychological complications. No significant differences were observed between the two groups regarding age (mean age: 64.5 ± 12.2 years vs 66.3 ± 11.9 years, P = 0.295), education level (primary school or below: 41.3% vs 39.4%; secondary school: 39.1% vs 40.9%; college or above: 19.6% vs 19.7%, P = 0.672), marital status (married: 82.6% vs 86.4%, P = 0.462), or residence type (urban: 58.7% vs 56.1%, P = 0.591) (Table 1).

| Characteristic | PSD group (n = 46) | Non-PSD group (n = 66) | P value |

| Gender (female) | 56.5 | 39.4 | 0.003 |

| Age (years) | 64.5 ± 12.2 | 66.3 ± 11.9 | 0.295 |

| Education level | 0.672 | ||

| Primary school or below | 41.3 | 39.4 | |

| Secondary school | 39.1 | 40.9 | |

| College or above | 19.6 | 19.7 | |

| Marital status (married) | 82.6 | 86.4 | 0.462 |

| Residence type (urban) | 58.7 | 56.1 | 0.591 |

| History of mental disorders | 17.4 | 6.1 | < 0.001 |

| Social support (SSRS Score) | 31.6 ± 7.7 | 38.8 ± 8.6 | < 0.001 |

| Smoking history | 28.3 | 25.8 | 0.657 |

| Alcohol history | 19.6 | 15.2 | 0.435 |

| History of hypertension | 65.2 | 62.1 | 0.723 |

| History of diabetes | 26.1 | 25.8 | 0.954 |

| History of dyslipidemia | 30.4 | 28.8 | 0.837 |

| History of atrial fibrillation | 13.0 | 10.6 | 0.678 |

Analysis of stroke-related clinical indicators revealed that patients in the PSD group had significantly higher NIHSS scores at admission compared to the non-PSD group (median: 8.0 vs 5.0, P < 0.001), indicating more severe neurological deficits. Regarding stroke location, infarcts involving the frontal lobe (32.0% vs 17.4%, P = 0.003) and limbic system (including anterior cingulate cortex and basal ganglia-thalamic regions) (28.1% vs 15.2%, P = 0.006) were significantly more common in the PSD group. Functional status assessment at 2 weeks post-stroke showed that patients in the PSD group had higher mRS scores (median: 3.0 vs 2.0, P < 0.001) and lower BI scores (median: 65.0 vs 80.0, P < 0.001), reflecting greater disability and dependence in daily living activities. No significant differences were found in stroke etiology according to the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment classification between the two groups (P = 0.327, Table 2).

| Stroke characteristic | PSD group (n = 46) | Non-PSD group (n = 66) | P value |

| NIHSS score at admission | 8.2 ± 2.3 | 5.1 ± 1.8 | < 0.001 |

| Stroke location | |||

| Frontal lobe infarct | 32.0 | 17.4 | 0.003 |

| Limbic system infarct (including anterior cingulate cortex and basal ganglia-thalamic regions) | 28.1 | 15.2 | 0.006 |

| Functional status at 2 weeks post-stroke | |||

| mRS score | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | < 0.001 |

| BI score | 65.0 ± 15.0 | 80.0 ± 10.0 | < 0.001 |

| TOAST classification | 0.327 | ||

| History of stroke recurrence | 15.2 | 9.1 | 0.345 |

| Time of stroke onset (hours) | 4.5 ± 1.2 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 0.023 |

| Systolic blood pressure at stroke onset (mmHg) | 160.0 ± 20.0 | 150.0 ± 15.0 | 0.047 |

| Blood glucose level at stroke onset (mmol/L) | 7.5 ± 1.5 | 6.8 ± 1.0 | 0.032 |

Separate multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed for pure anxiety, pure depression, comorbid anxiety-depression, and combined PSD. For pure depression (n = 14), the strongest independent predictors were history of mental disorders (OR = 4.12, 95%CI: 2.01-8.45, P < 0.001), left hemisphere lesions (OR = 3.28, 95%CI: 1.54-6.97, P = 0.002), and low social support (OR = 2.95, 95%CI: 1.38-6.31, P = 0.005). For pure anxiety (n = 15), key predictors included female gender (OR = 3.15, 95%CI: 1.42-6.98, P = 0.005), right hemisphere lesions (OR = 2.87, 95%CI: 1.31-6.29, P = 0.008), and NIHSS ≥ 8 (OR = 2.42, 95%CI: 1.09-5.37, P = 0.030). For comorbid anxiety-depression (n = 17), all five risk factors showed significant associations, with the highest ORs observed for history of mental disorders (OR = 4.56, 95%CI: 2.15-9.68, P < 0.001) and NIHSS ≥ 8 (OR = 3.82, 95%CI: 1.78-8.19, P < 0.001).

For the combined PSD group (n = 46), multivariate logistic regression analysis identified five independent risk factors for developing PSD: Female gender (OR = 2.32, 95%CI: 1.56-3.45, P < 0.001), history of mental disorders prior to stroke (OR = 3.17, 95%CI: 1.89-5.32, P < 0.001), infarct location in the frontal lobe or limbic system (OR = 2.86, 95%CI: 1.73-4.71, P < 0.001), stroke severity with NIHSS ≥ 8 at admission (OR = 2.54, 95%CI: 1.62-3.99, P < 0.001), and low social support defined as SSRS score < 35 (OR = 2.18, 95%CI: 1.42-3.36, P = 0.002). These findings highlight the multifactorial nature of PSD, with both shared risk factors across subtypes and distinct patterns differentiating pure anxiety, pure depression, and comorbid presentations. The combined PSD model provides practical clinical utility for initial screening of patients at risk for any post-stroke mood disturbance (Table 3).

| Risk factor | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | P value |

| Female gender | 2.32 | 1.56-3.45 | < 0.001 |

| History of mental disorders prior to stroke | 3.17 | 1.89-5.32 | < 0.001 |

| Infarct location in the frontal lobe or limbic system | 2.86 | 1.73-4.71 | < 0.001 |

| Stroke severity with NIHSS ≥ 8 at admission | 2.54 | 1.62-3.99 | < 0.001 |

| Low social support (SSRS score < 35) | 2.18 | 1.42-3.36 | 0.002 |

| Smoking history | 1.45 | 0.92-2.29 | 0.110 |

| Alcohol history | 1.32 | 0.81-2.16 | 0.265 |

| History of hypertension | 1.28 | 0.85-1.93 | 0.246 |

| History of diabetes | 1.54 | 0.98-2.42 | 0.062 |

This analysis demonstrates distinct neuroanatomical and clinical profiles across PSD subtypes, with hemispheric lateralization emerging as a key differentiating factor. Further analysis comparing patients with anxiety only, depression only, and comorbid anxiety-depression revealed distinct characteristics. Patients with depression only were more likely to have lesions in the left hemisphere (68.4% vs 45.2% in anxiety only, P = 0.037), particularly left frontal lesions. In contrast, patients with anxiety only showed a higher prevalence of right hemisphere lesions (59.5% vs 39.5% in depression only, P = 0.044). Patients with comorbid anxiety-depression had the highest NIHSS scores [median: 9.5 (IQR: 7.5-11.5) vs median: 7.0 (IQR: 5.5-8.5) in depression only and 6.5 (IQR: 5.0-8.0) in anxiety only, P = 0.013], and the poorest functional outcomes as measured by mRS and BI scores. These findings suggest potentially different pathophysiological mechanisms underlying post-stroke anxiety vs depression, with important implications for targeted therapeutic approaches (Table 4).

| Characteristic | Anxiety only (n = 15) | Depression only (n = 14) | Comorbid anxiety-depression (n = 17) | P value |

| Left hemisphere lesions | 45.2 | 68.4 | 58.8 | 0.037 |

| Right hemisphere lesions | 59.5 | 39.5 | 47.1 | 0.044 |

| NIHSS score at admission | 6.5 ± 1.5 | 7.0 ± 2.0 | 9.5 ± 2.5 | 0.013 |

| Functional status at 2 weeks post-stroke | ||||

| mRS score | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 3.5 ± 1.0 | < 0.001 |

| BI score | 75.0 ± 10.0 | 68.0 ± 12.0 | 60.0 ± 15.0 | < 0.001 |

| Social support score (SSRS) | 35.0 ± 5.0 | 32.0 ± 6.0 | 30.0 ± 7.0 | 0.021 |

| Time of stroke onset (hours) | 3.5 ± 1.0 | 4.0 ± 1.2 | 4.5 ± 1.5 | 0.034 |

| Systolic blood pressure at stroke onset (mmHg) | 155.0 ± 20.0 | 160.0 ± 22.0 | 165.0 ± 25.0 | 0.048 |

| Blood glucose level at stroke onset (mmol/L) | 7.0 ± 1.2 | 7.2 ± 1.3 | 7.8 ± 1.5 | 0.039 |

| Education level | 0.056 | |||

| Primary school or below | 40.0 | 50.0 | 64.7 | |

| Secondary school | 40.0 | 35.7 | 29.4 | |

| College or above | 20.0 | 14.3 | 5.9 | |

| Age (years) | 63.0 ± 10.0 | 65.0 ± 11.0 | 67.0 ± 12.0 | 0.234 |

Neuroimaging analysis revealed that infarct volume was significantly larger in the PSD group compared to the non-PSD group [median: 8.7 cm3 (IQR: 6.8-10.5) vs median: 5.3 cm3 (IQR: 4.2-6.8), P = 0.003]. White matter hyperintensities were more severe in the PSD group, with higher Fazekas scores for both periventricular [median: 2.0 (IQR: 1.0-3.0) vs median: 1.0 (IQR: 0-2.0), P = 0.012] and deep white matter lesions [median: 2.0 (IQR: 1.0-3.0) vs median: 1.0 (IQR: 0-2.0), P = 0.008]. Brain atrophy, particularly frontal lobe atrophy, was also more pronounced in the PSD group (P = 0.017). Advanced MRI parameters revealed reduced apparent diffusion coefficient values in the PSD group (0.82 ± 0.10 × 10-3 mm2/senced vs 0.89 ± 0.12 × 10-3 mm2/senced, P = 0.045), suggesting greater tissue microstructural damage in mood-regulatory regions. Perfusion imaging demonstrated altered cerebrovascular hemodynamics in PSD patients, with increased wash-in rate (50.33 ± 5.0 seconds-1vs 45.00 ± 4.5 seconds-1, P = 0.038), prolonged time to peak (120 ± 10 seconds vs 110 ± 8 seconds, P = 0.027), and elevated wash-out rate (30.00 ± 3.5 seconds-1vs 25.00 ± 3.0 seconds-1, P = 0.042), potentially reflecting impaired neurovascular coupling that may compromise metabolic support for emotional regulatory circuits. These findings suggest that both acute ischemic lesions and chronic cerebrovascular changes contribute to the development of PSD (Table 5).

| Neuroimaging feature | PSD group (n = 46) | Non-PSD group (n = 66) | P value |

| Infarct volume (cm³) | 8.7 ± 2.5 | 5.3 ± 1.8 | 0.003 |

| White matter hyperintensities (WMH) | |||

| Fazekas score (periventricular) | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.012 |

| Fazekas score (deep white matter) | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.008 |

| Brain atrophy | |||

| Frontal lobe atrophy (%) | 25.0 ± 5.0 | 10.6 ± 3.0 | 0.017 |

| Global brain atrophy (%) | 45.7 ± 7.0 | 33.3 ± 6.0 | 0.086 |

| Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) | 0.82 ± 0.10 × 10-3 mm2/second | 0.89 ± 0.12 × 10-3 mm2/second | 0.045 |

| Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI parameters | |||

| Wash-in rate (WIR) | 50.33 ± 5.0 seconds-1 | 45.00 ± 4.5 seconds-1 | 0.038 |

| Time to peak (TTP) | 120 ± 10 seconds | 110 ± 8 seconds | 0.027 |

| Wash-out rate (WOR) | 30.00 ± 3.5 seconds-1 | 25.00 ± 3.0 seconds-1 | 0.042 |

Analysis of inflammatory markers showed significantly elevated levels of IL-6 [median: 7.8 pg/mL (IQR: 6.5-9.2) vs median: 4.5 pg/mL (IQR: 3.8-5.5), P < 0.001] and TNF-α [median: 15.6 pg/mL (IQR: 13.2-18.1) vs median: 9.8 pg/mL (IQR: 8.2-11.5), P < 0.001] in the PSD group compared to the non-PSD group. Assessment of the HPA axis revealed dysregulation in the PSD group, characterized by higher morning serum cortisol levels (mean ± SD: 386.5 ± 92.3 nmol/L vs mean ± SD: 328.7 ± 75.6 nmol/L, P < 0.001) and flattened diurnal cortisol rhythm (reduced evening decline). These findings support the role of neuroinflammation and neuroendocrine dysfunction in PSD pathophysiology, consistent with our empirical observations of elevated inflammatory and stress markers in affected patients (Table 6).

| Indicator | PSD group (n = 46) | Non-PSD group (n = 66) | P value |

| Inflammatory markers | |||

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 7.8 ± 1.2 | 4.5 ± 0.8 | < 0.001 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 15.6 ± 2.3 | 9.8 ± 1.5 | < 0.001 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 12.5 ± 3.4 | 8.2 ± 2.1 | 0.002 |

| MCP-1 (pg/mL) | 450 ± 60 | 380 ± 50 | 0.010 |

| HPA axis function | |||

| Morning serum cortisol (nmol/L) | 386.5 ± 92.3 | 328.7 ± 75.6 | < 0.001 |

| Diurnal cortisol rhythm (evening decline) | Reduced | Normal | - |

| ACTH level (pg/mL) | 40.5 ± 7.8 | 35.2 ± 6.5 | 0.034 |

| Diurnal cortisol variation (%) | 25.0 ± 5.0 | 35.0 ± 6.0 | 0.001 |

| Cortisol awakening response (nmol/L) | 150.0 ± 30.0 | 180.0 ± 40.0 | 0.02 |

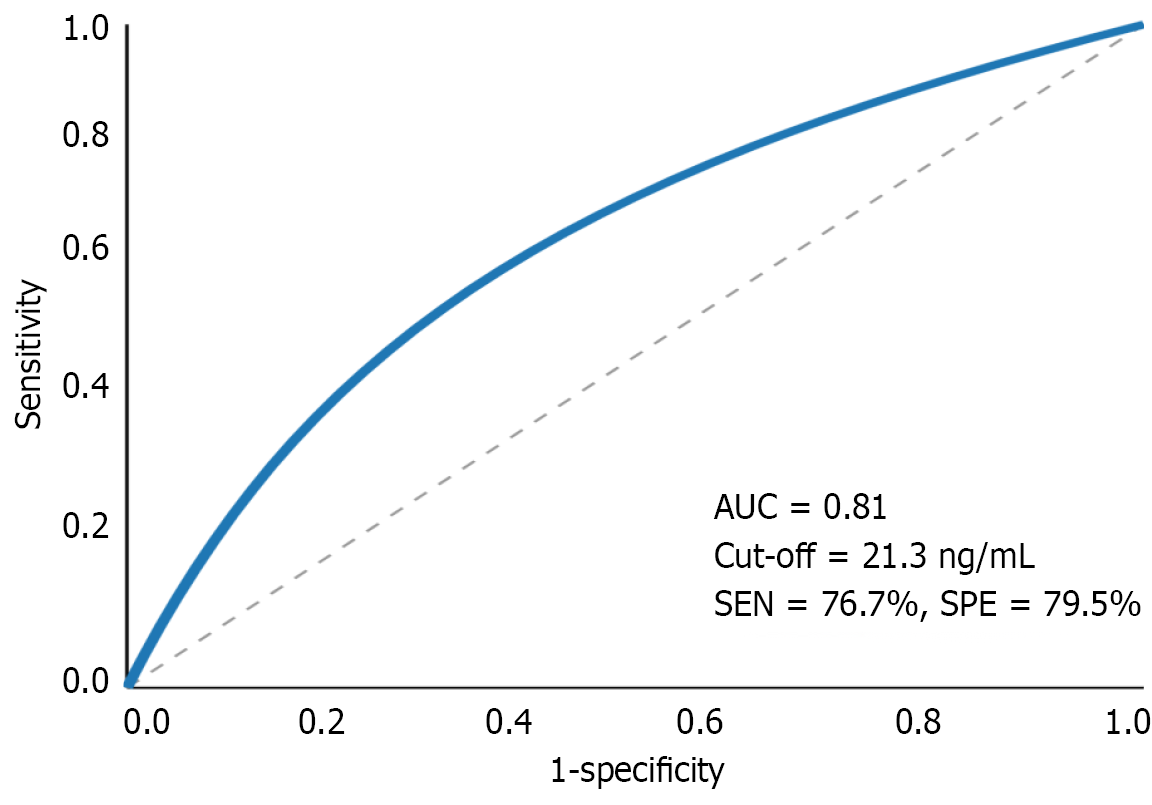

Subgroup analysis revealed that IGF-1 levels were particularly reduced in patients with depression (with or without anxiety) compared to those with anxiety only (P = 0.009). Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis demonstrated that IGF-1 had the highest diagnostic value for identifying post-stroke depression, with an area-under-the-curve of 0.81 (95%CI: 0.74-0.88), sensitivity of 76.7%, and specificity of 79.5% at the optimal cutoff value of 21.3 ng/mL (Figure 1).

Ischemic stroke remains one of the leading causes of disability and mortality worldwide. Despite significant advances in acute treatment and rehabilitation strategies that have improved survival rates, post-stroke neuropsychiatric complications - particularly anxiety and depression - often go unrecognized and undertreated[12-15]. These conditions, collectively referred to as PSD, affect approximately 30%-50% of stroke survivors and have profound implications for rehabilitation outcomes, treatment adherence, hospital stay duration, recurrence risk, and mortality[7,16,17]. The development of PSD involves a complex interplay of neuroanatomical, neurobiochemical, and psychosocial factors. Brain vascular events causing damage to specific regions and related neurotransmitter systems form the biological foundation for these conditions[6,18,19]. Neuroanatomically, the study demonstrated that infarcts involving the frontal lobe (32.0% vs 17.4%) and limbic system (28.1% vs 15.2%) were significantly more common in patients who developed PSD. This distribution supports the disruption of frontal-limbic circuits as a fundamental mechanism underlying post-stroke mood disorders, as these neural networks are critically involved in emotional regulation and stress response.

Intriguingly, hemispheric lateralization appears to play a distinct role in differentiating anxiety from depression[20]. Patients with depression predominantly exhibited left hemisphere lesions (68.4%), particularly in the left frontal region, while anxiety was more associated with right hemisphere damage (59.5%). This pattern suggests potentially different pathophysiological mechanisms for anxiety vs depression following stroke, with implications for both diagnosis and treatment approaches. The left hemisphere's involvement in depression aligns with the neurocircuitry hypothesis of mood disorders, which emphasizes the role of left frontal regions in positive affect regulation.

The immune response in the brain after a stroke is also one of the main causes of PSD. Inflammatory markers IL-6 (7.8 pg/mL vs 4.5 pg/mL) and TNF-α (15.6 pg/mL vs 9.8 pg/mL) were significantly higher in PSD patients. This chronic pro-inflammatory state might disrupt neurotransmitter metabolism and synaptic balance or rhythmic neural activity, hence disrupting overall brain neuroplasticity and thereby potentially limiting rehabilitation success and mood regulation. Inflammatory cytokines have been shown to alter serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine transmission, all important in the control of both anxiety and depression[21-23]. In addition, neuroinflammation can enhance excitotoxicity and oxidative stress in stressful circuits that may increase neuronal damage[23,24].

HPA axis dysfunction is another key biological pathway in PSD. As demonstrated by higher morning serum cortisol levels (386.5 ± 92.3 nmol/L vs 328.7 ± 75.6 nmol/L) and flattened diurnal cortisol rhythm, indicating a significant stress system dysregulation[25-27]. This pattern is similar to the neuroendocrine changes seen in primary anxiety and de

The clinical implications of these results are significant. Knowledge of the neurobiological basis for PSD provides potential targets for therapeutic interventions. Other techniques, including anti-inflammatory approaches, HPA axis modulators, and IGF-1-enhancing strategies, may also function in concert with traditional psychotherapy and antidepressant treatments. Ideally, specific symptom profiles of mixed anxiety and depression may also result from separate neuroanatomical correlates, which could imply that treatment should be targeted to this end. Furthermore, the detection of modifiable risk factors offers opportunities for preventive actions, especially in patients at high risk. Future research directions should be focused on the prospective validation of IGF-1 and other biomarkers in larger cohorts, targeted interventions designed to address specific neurobiological mechanisms that have potential for treatment development, the integration of biological and psychosocial components into personalized risk assessment tools, and examining, albeit not necessarily limited to, how PSD impacts longer-term trajectories of stroke recovery. The interaction between stroke, mental health, and recovery outcomes demonstrates the need for holistic or integrative approaches to post-stroke care, focusing on both physical and psychological aspects of recovery.

This study has several important limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the retrospective single-center design limits causal inference and may introduce selection bias, potentially affecting the generalizability of our findings to broader stroke populations. Second, the cross-sectional assessment of PSD at a single time point (2 weeks post-stroke) cannot capture the dynamic trajectory of mood symptoms or distinguish between transient adjustment reactions and persistent mood disorders. Longitudinal assessments with multiple time points are needed to understand the temporal evolution of PSD.

In conclusion, PSD represents a complex neuropsychiatric consequence of stroke with multifactorial etiology spanning neuroanatomical, neurobiochemical, and psychosocial domains. The identification of specific risk factors and potential biomarkers offers promising avenues for early detection and intervention.

| 1. | Chen R, Liu Z, Liao R, Liang H, Hu C, Zhang X, Chen J, Xiao H, Ye J, Guo J, Wei L. The effect of sarcopenia on prognosis in patients with mild acute ischemic stroke: a prospective cohort study. BMC Neurol. 2025;25:130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ullman NL, Vossough A, Beslow LA, Ichord RN, Shih EK. FLAIR Vascular Hyperintensities as Imaging Biomarker in Pediatric Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2025;56:1505-1515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yogendrakumar V, Campbell BCV, Johns HT, Churilov L, Ng FC, Sitton CW, Hassan AE, Abraham MG, Ortega-Gutierrez S, Hussain MS, Chen M, Kasner SE, Sharma G, Guha P, Pujara DK, Shaker F, Lansberg MG, Wechsler LR, Nguyen TN, Fifi JT, Hill MD, Ribo M, Parsons MW, Davis SM, Grotta JC, Albers GW, Sarraj A; SELECT2 Investigators. Association of Ischemic Core Hypodensity With Thrombectomy Treatment Effect in Large Core Stroke: A Secondary Analysis of the SELECT2 Randomized Controlled Trial. Stroke. 2025;56:1366-1375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Suñer-Soler R, Maldonado E, Rodrigo-Gil J, Font-Mayolas S, Gras ME, Terceño M, Silva Y, Serena J, Grau-Martín A. Sex-Related Differences in Post-Stroke Anxiety, Depression and Quality of Life in a Cohort of Smokers. Brain Sci. 2024;14:521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gu P, Ding Y, Ruchi M, Feng J, Fan H, Fayyaz A, Geng X. Post-stroke dizziness, depression and anxiety. Neurol Res. 2024;46:466-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Celikbilek A, Koysuren A, Konar NM. Correction to: Role of vitamin D in the association between prestroke sleep quality and post-stroke depression and anxiety. Sleep Breath. 2024;28:2323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schöttke H, Giabbiconi CM. Post-stroke depression and post-stroke anxiety: prevalence and predictors. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27:1805-1812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sadlonova M, Wasser K, Nagel J, Weber-Krüger M, Gröschel S, Uphaus T, Liman J, Hamann GF, Kermer P, Gröschel K, Herrmann-Lingen C, Wachter R. Health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression up to 12 months post-stroke: Influence of sex, age, stroke severity and atrial fibrillation - A longitudinal subanalysis of the Find-AF(RANDOMISED) trial. J Psychosom Res. 2021;142:110353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Randolph S, Lee Y, Nicholas ML, Connor LT. The mediating effect of anxiety on the association between residual neurological impairment and post-stroke participation among persons with and without post-stroke depression. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2024;34:181-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Elias S, Benevides ML, Pereira Martins AL, Martins GL, Sperb Wanderley Marcos AB, Nunes JC. In-Hospital Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety are Strong Risk Factors for Post-Stroke Depression 90 Days After Ischemic Stroke. Neurohospitalist. 2023;13:121-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Almhdawi KA, Alazrai A, Kanaan S, Shyyab AA, Oteir AO, Mansour ZM, Jaber H. Post-stroke depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms and their associated factors: A cross-sectional study. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2021;31:1091-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang J, Ding M, Luo L, Huang D, Li S, Chen S, Fan Y, Liu L, Xie H, Liu G, Yu K, Wu J, Xiao X, Wu Y. Intermittent theta-burst stimulation promotes neurovascular unit remodeling after ischemic stroke in a mouse model. Neural Regen Res. 2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yan H, Hua Y, Ni J, Wu X, Xu J, Zhang Z, Dong J, Xiong Z, Yang L, Yuan H. Acupuncture ameliorates inflammation by regulating gut microbiota in acute ischemic stroke. IBRO Neurosci Rep. 2025;18:443-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang L, Guan X, Zhou J, Hu H, Liu W, Wei Q, Huang Y, Sun W, Jin X, Li H. Measuring the health outcomes of Chinese ischemic stroke patients based on the data from a longitudinal multi-center study. Qual Life Res. 2025;34:1967-1977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sun S, Lomachinsky V, Smith LH, Newhouse JP, Westover MB, Blacker DL, Schwamm LH, Haneuse S, Moura LMVR. Benzodiazepine Initiation and the Risk of Falls or Fall-Related Injuries in Older Adults Following Acute Ischemic Stroke. Neurol Clin Pract. 2025;15:e200452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Marshall RS, Basilakos A, Williams T, Love-Myers K. Exploring the benefits of unilateral nostril breathing practice post-stroke: attention, language, spatial abilities, depression, and anxiety. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:185-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Broomfield NM, Quinn TJ, Abdul-Rahim AH, Walters MR, Evans JJ. Depression and anxiety symptoms post-stroke/TIA: prevalence and associations in cross-sectional data from a regional stroke registry. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Choo WT, Jiang Y, Chan KGF, Ramachandran HJ, Teo JYC, Seah CWA, Wang W. Effectiveness of caregiver-mediated exercise interventions on activities of daily living, anxiety and depression post-stroke rehabilitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78:1870-1882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cheng C, Fan W, Liu C, Liu Y, Liu X. Reminiscence therapy-based care program relieves post-stroke cognitive impairment, anxiety, and depression in acute ischemic stroke patients: a randomized, controlled study. Ir J Med Sci. 2021;190:345-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Horato N, Quagliato LA, Nardi AE. The relationship between emotional regulation and hemispheric lateralization in depression: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sah A, Singewald N. The (neuro)inflammatory system in anxiety disorders and PTSD: Potential treatment targets. Pharmacol Ther. 2025;269:108825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mohammadi S, Bashghareh A, Karimi-Zandi L, Mokhtari T. Understanding Role of Maternal Separation in Depression, Anxiety,and Pain Behaviour: A Mini Review of Preclinical Research With Focus on Neuroinflammatory Pathways. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2025;85:e70002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lu J, Liang W, Cui L, Mou S, Pei X, Shen X, Shen Z, Shen P. Identifying Neuro-Inflammatory Biomarkers of Generalized Anxiety Disorder from Lymphocyte Subsets Based on Machine Learning Approaches. Neuropsychobiology. 2025;84:74-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Frye BM, Negrey JD, Johnson CSC, Kim J, Barcus RA, Lockhart SN, Whitlow CT, Chiou KL, Snyder-Mackler N, Montine TJ, Craft S, Shively CA, Register TC. Mediterranean diet protects against a neuroinflammatory cortical transcriptome: Associations with brain volumetrics, peripheral inflammation, social isolation, and anxiety in nonhuman primates (Macaca fascicularis). Brain Behav Immun. 2024;119:681-692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Harris BN, Roberts BR, DiMarco GM, Maldonado KA, Okwunwanne Z, Savonenko AV, Soto PL. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity and anxiety-like behavior during aging: A test of the glucocorticoid cascade hypothesis in amyloidogenic APPswe/PS1dE9 mice. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2023;330:114126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Feng LS, Wang YM, Liu H, Ning B, Yu HB, Li SL, Wang YT, Zhao MJ, Ma J. Hyperactivity in the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis: An Invisible Killer for Anxiety and/or Depression in Coronary Artherosclerotic Heart Disease. J Integr Neurosci. 2024;23:222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Csabafi K, Ibos KE, Bodnár É, Filkor K, Szakács J, Bagosi Z. A Brain Region-Dependent Alteration in the Expression of Vasopressin, Corticotropin-Releasing Factor, and Their Receptors Might Be in the Background of Kisspeptin-13-Induced Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Activation and Anxiety in Rats. Biomedicines. 2023;11:2446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/