Published online Oct 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i10.106679

Revised: June 17, 2025

Accepted: August 4, 2025

Published online: October 19, 2025

Processing time: 132 Days and 23.7 Hours

Anxiety and depression are common psychological reactions in teenagers with facial burns and have a significant impact on their rehabilitation and quality of life.

To analyze anxiety and depressive symptoms in teenagers with facial burns.

We selected 50 young patients with facial burns who were treated at our hospital between October 2023 and October 2024. The Hamilton Anxiety Scale and Beck Depression Inventory were used to evaluate anxiety and depressive symptoms. Additionally, we evaluated patients’ social support levels and self-esteem. Pear

The overall average Hamilton Anxiety Scale score was 23.4 ± 6.2, and 16 (32%) and 34 (68%) patients showed mild to moderate and moderate to severe anxiety, respectively. The overall average Beck Depression Inventory score was 18.7 ± 7.5, and 23 (46%) and 27 (54%) patients had mild to moderate and moderate to severe depression, respectively. Furthermore, Pearson’s correlation analysis showed a significant positive correlation between burn severity and anxiety (r = 0.48, P < 0.01) and depression (r = 0.42, P < 0.01) symptoms. Self-esteem scores and social support were significantly negatively correlated with anxiety (r = -0.55 and r = -0.40, respectively; P < 0.01) and depression (r = -0.60 and r = -0.38, respectively; P < 0.01 for both).

Adolescents with facial burns commonly experience anxiety and depressive symptoms, the severity of which is closely related to burn severity, social support, and self-esteem.

Core Tip: The aim of this study was to analyze the symptoms of anxiety and depression in adolescent facial burn patients and the factors affecting anxiety and depression to provide a reference for the psychological treatment of adolescent facial burns. Anxiety and depression are common psychological reactions in adolescents with facial burns. The severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adolescents with facial burns is strongly correlated with social support and self-esteem. These psychological problems have a significant impact on adolescent recovery and quality of life.

- Citation: Yu Z, Zhang H, Zhang Q, Wu QE. Analysis of anxiety and depression symptoms in adolescents with facial burns. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(10): 106679

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i10/106679.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i10.106679

Burns are typically induced by high-intensity currents, elevated temperatures, chemical exposures, and physical radiation[1]. The incidence of burns increases with the ongoing processes of mechanization and urbanization. Despite government initiatives aimed at preventing and treating burn-related mortality, the disability rate among burn patients has not shown a corresponding decline. The annual incidence of burns in China is approximately 2%[2], and burns are the second leading cause of mortality among accidents. Studies have shown that facial burns account for more than half of all burn incidents[3]. In addition, patients with burns often have mental health problems such as anxiety and depression[4-6]. As adolescence is a key stage in identity formation and self-esteem, facial burns in this age group have a far-reaching negative impact on self-esteem and social interaction, leading to mental health problems among adolescents. In addition, women with facial burns are more likely to develop depression[7,8]. Social support can affect anxiety and depressive symptoms in adolescent patients with facial burns[9,10].

The aim of this study was to analyze anxiety and depressive symptoms in adolescent patients with facial burns. We used the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA)[11] and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)[12] to evaluate anxiety and de

We retrospectively collected clinical data of 50 adolescent patients with facial burns who underwent treatment at our hospital between October 2023 and October 2024. Clinical data were collected over a minimum recovery period of three months. Information was gathered from hospitals’ electronic medical records and surveys.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Age between 12 and 18 years; (2) Hospitalization for facial burns; (3) Ability to communicate effectively in Chinese to answer or complete questionnaires; and (4) Clear consciousness and cognitive abilities.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Individuals diagnosed with acute diseases affecting the cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, or digestive systems, as well as those with severe infections, malignancies, significant electrolyte imbalances, or disorders of the immune and hematological systems; (2) Individuals with dementia, various psychiatric disorders, or those demonstrating noncompliance; and (3) Individuals with a history of substance or alcohol dependence, in addition to prior use of antidepressants or anxiolytic medication.

The research approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Baoji Central Hospital, approval No. BZYL2022-49. Informed consent was not required because the study was retrospective and did not involve disclosure of patient identities.

During hospitalization, trained researchers conducted face-to-face surveys with all participants. All measurements were obtained during the recovery period to assess the long-term effects of burns on mental health. Throughout the data collection process, the privacy of all participants and the confidentiality of the data were ensured.

The BDI was used to evaluate depressive symptoms with 21 items, each rated on a scale of 0 to 3, resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 63. Depression was classified as mild when the severity was ≤ 17 and moderate to severe when it was ≥ 18. Cronbach’s alpha for our sample was 0.90[13,14].

We used the HAMA to evaluate anxiety levels in adolescent patients with facial burns. The HAMA includes 14 items, each of which includes multiple symptoms, and is scored on a scale of 0 to 4, with 4 being the most serious. The mean total HAMA scores were 56. A score of ≤ 17 indicates mild anxiety, and a score of 18-30 indicates moderate to severe anxiety[15]. The HAMA adhered to psychometric standards, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93.

Social support was assessed with the Social Support Appraisals tool for children[16], featuring 30 items rated on a 6-point Likert scale from “fully agree” to “fully disagree”. The scores ranged from 30 to 180, with higher scores reflecting greater perceived social support. Scores of 30-90 indicate low social support, 91-135 indicate moderate support, and 136-180 indicate high support, respectively.

Self-esteem was evaluated using the Self-Esteem Scale, which classifies self-esteem into low, medium, and high categories[17]. Initially developed for adolescent populations, the scale comprises ten closed-ended items, with half of the items assessing the positive dimensions of self-image and self-worth and the remaining half addressing negative self-image and self-depreciation. Participants responded using a four-point Likert scale consisting of options. Higher scores on the Self-Esteem Scale reflected greater self-esteem, with scores ranging from 10 to 40: 10-20 points suggest low self-esteem, 21-30 points suggest moderate self-esteem, and 31-40 points suggest high self-esteem.

Burn severity[18]: We further classified burns into three categories based on the Abbreviated Burn Severity Index score, with mild burns scoring 2-3, moderate burns scoring 4-7, and severe burns scoring ≥ 8.

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26.0. Continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations, while categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages. Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to examine the relationships among the severity of burns, levels of social support, Self-Esteem Scores, and anxiety or depression symptoms. In the correlation analysis, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were determined, and the P value was corrected using the Benjamini-Hochberg method for multiple comparisons, ensuring a false discovery rate of < 0.05.

Fifty adolescents with facial burns were included in this study, ranging in age from 12 to 18 years, with an average age of 15.3 years. Of the participants, 58% (n = 29) were male and 42% (n = 21) were female. Burns were classified as mild in 9 cases (18.0%), moderate in 19 cases (38.0%), and severe in 22 cases (44.0%).

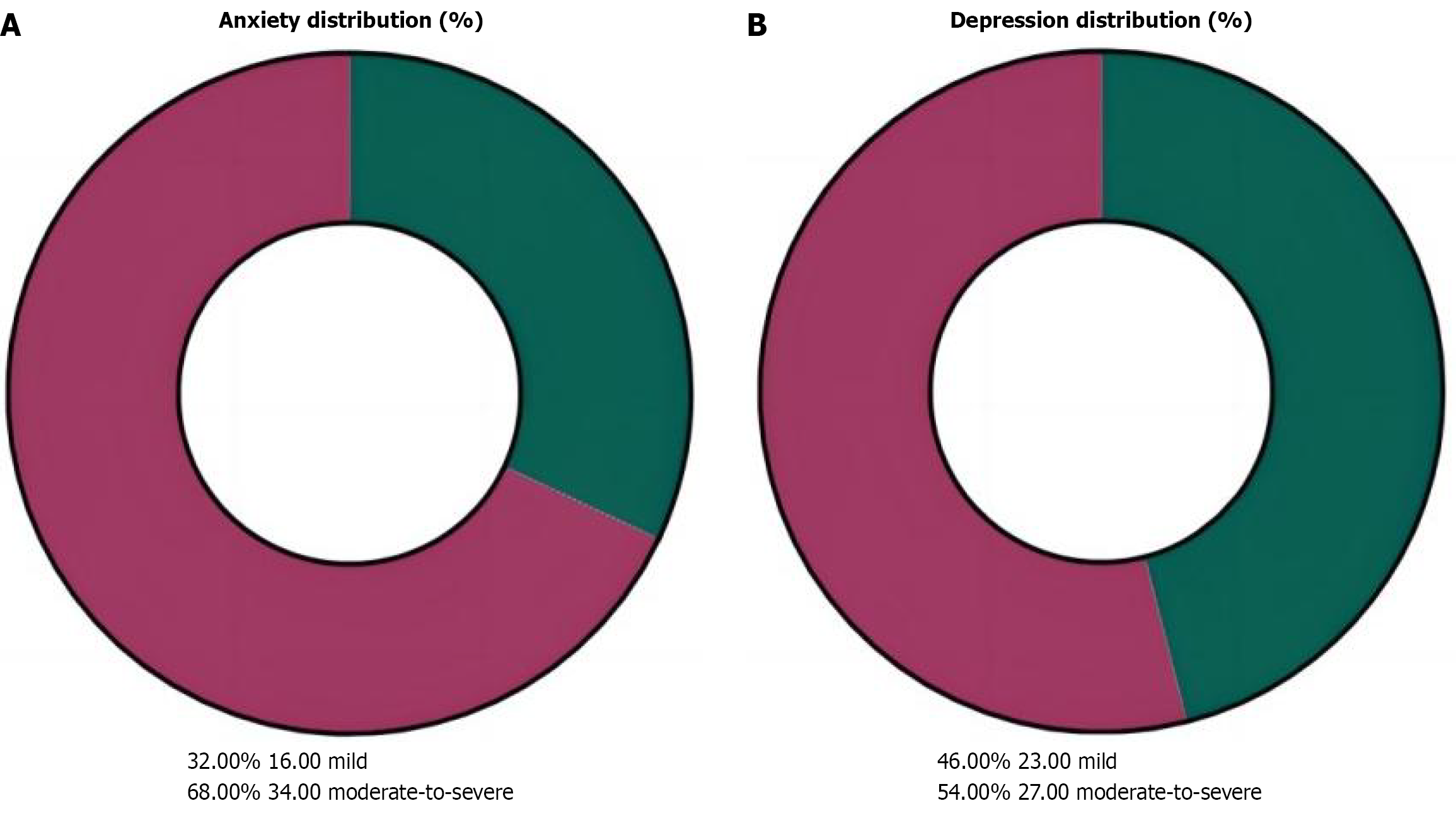

According to the HAMA scoring criteria, the average anxiety score among participants was 23.4 ± 6.2, with 16 cases (32%) exhibiting mild or lower anxiety symptoms, and 34 cases (68%) presenting with moderate to severe anxiety (score ≥ 18) (Figure 1A). The average BDI score was 18.7 ± 7.5, with 23 cases (46%) showing mild or lower depression symptoms, and 27 cases (54%) experiencing moderate to severe depression (score ≥ 18) (Figure 1B).

As shown in Table 1, there were significant statistical differences in burn severity among patients with varying degrees of depression (P < 0.05). Similarly, there were significant statistical differences in burn severity among patients with diffe

| Variable | Mild depression (n = 23) | Moderate-to-severe depression (n = 27) | P value |

| Burns | |||

| Mild burns | 6 (26.09) | 3 (11.11) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate burns | 13 (56.52) | 6 (22.22) | |

| Severe burns | 4 (17.39) | 18 (66.67) | |

| Variable | Mild anxiety (n = 16) | Moderate-to-severe anxiety (n = 34) | P value |

| Burns | |||

| Mild burns | 7 (43.75) | 2 (5.88) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate burns | 8 (50) | 11 (32.35) | |

| Severe burns | 1 (6.25) | 21 (61.76) | |

Assessment results for social support indicated an average score for patients’ social support of 112.5 ± 18.4. Individuals with reduced social support showed signs of anxiety and depression (P < 0.05). The average score for self-esteem assessment was 40.2 ± 9.3, with patients scoring lower showing significantly higher scores on the anxiety (P < 0.01) and depression (P < 0.01) scales, as shown in Tables 3 and 4.

| Variable | Mild depression (n = 23) | Moderate-to-severe depression (n = 27) | P value |

| Social support | |||

| Low support | 9 (39.13) | 15 (55.56) | 0.015 |

| Moderate support | 6 (26.09) | 7 (25.93) | |

| High support | 8 (34.78) | 5 (18.52) | |

| Self-esteem | |||

| Low self-esteem | 8 (34.78) | 18 (66.67) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate self-esteem | 7 (30.43) | 6 (22.22) | |

| High self-esteem | 8 (34.78) | 3 (11.11) | |

| Variable | Mild anxiety (n = 16) | Moderate-to-severe anxiety (n = 34) | P value |

| Social support | |||

| Low support | 6 (37.5) | 18 (52.94) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate support | 4 (25.0) | 9 (26.47) | |

| High support | 6 (37.5) | 7 (20.59) | |

| Self-esteem | |||

| Low self-esteem | 7 (43.75) | 21 (61.76) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate self-esteem | 4 (25.0) | 9 (26.47) | |

| High self-esteem | 5 (31.25) | 4 (11.76) | |

Furthermore, Pearson’s correlation analysis indicated that burn severity was positively correlated with depressive (r = 0.42, P < 0.01) and anxiety symptoms (r = 0.48, P < 0.01). Additionally, self-esteem scores showed a significant negative correlation with anxiety (r = -0.55, P < 0.01) and depression (r = -0.60, P < 0.01). Social support exhibited significant negative correlations with anxiety (r = -0.40, P < 0.01) and depression (r = -0.38, P < 0.01).

In this study, we assessed the anxiety and depressive symptoms in 50 adolescents with facial burn injuries. The results indicated that 68% of patients exhibited moderate-to-severe anxiety symptoms, while 54% showed moderate-to-severe depression. These findings are consistent with existing literature, suggesting that patients with burns are at a higher risk of depression and anxiety.

Notably, when stratifying by gender, our data revealed that female participants (42% of the cohort) had a trend towards higher mean scores on both the HAMA (25.1 ± 6.8) and BDI (20.3 ± 8.1) scales compared to males (HAMA: 22.2 ± 5.7; BDI: 17.4 ± 6.9), although this difference did not reach statistical significance (P > 0.05). This aligned with previous research indicating that women generally report more severe psychological distress following traumatic events, likely because of sociocultural factors influencing body image perception and emotional expression. Future studies with larger sample sizes should explore the sex-specific risk factors for depression in adolescent burn survivors. Therefore, special attention should be paid to the mental health of adolescents with facial burns. This was consistent with previous research[19].

The results showed that the severity of facial burns was significantly and positively correlated with anxiety (r = 0.48, P < 0.01) and depression (r = 0.42, P < 0.01). This was consistent with the findings of Ward et al[20]. The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying this association likely involve a complex interplay between physical pain, disfigurement, and social stigma. Adolescents with severe burns may experience prolonged hospitalization, intensive rehabilitation, and altered self-perception, all of which can exacerbate psychological distress. For example, patients with deep burns may require multiple reconstructive surgeries, which can lead to extended periods of physical discomfort and social isolation. Possible causes include pain during recovery and changes in appearance caused by burns, which can negatively impact the mental health of adolescents.

Finally, the results of this study also show that social support is negatively correlated with depression and anxiety (depression r = -0.38, P < 0.01; anxiety r = -0.40, P < 0.01). Specifically, patients with lower levels of social support were more likely to experience anxiety and depression symptoms, which aligns with existing literature[21]. O’ Brien et al[22] reported that mental health problems affect the trajectory of burn recovery by increasing the length of hospital stay for burn survivors. Therefore, a targeted intervention is required. Cognitive behavioral therapy has demonstrated efficacy in reducing anxiety and depression by addressing maladaptive thoughts and behaviors associated with burn injuries. In addition, group therapy programs tailored to adolescent burn survivors can provide a supportive community, foster social connectedness, and improve self-esteem. For instance, the “Burn Support Group Model” integrates peer coun

This study had several limitations. First, the use of self-reported questionnaires to understand patients’ basic conditions and assess their mental health is flawed and may lead to recall bias, which, in some cases, may not accurately reflect the extent of the patients’ mental status. As this was a retrospective study, we may have overlooked some potential confounding variables, such as the quality of family support and economic status, which may undermine the reliability of the findings. Second, this cross-sectional study could not establish causal links between variables, necessitating further research. Third, the role of family history as a confounding factor for anxiety symptoms requires further investigation. Additionally, burn classification (e.g., hot fluid, flame) was missing when retrospectively collecting baseline data from patients, which may have affected the interpretation of severity. Future studies should incorporate subgroup analyses by type of burn and psychological symptoms. Finally, because the study was conducted at a single hospital in China, the findings are limited to Chinese patients. Their representativeness is difficult to generalize, and future studies should involve larger-scale, multicenter, and more rigorous prospective studies to confirm these findings.

In summary, the results of this study indicated that some adolescents with facial burn injuries exhibited symptoms of depression and anxiety. Burn severity significantly and positively correlated with anxiety and depressive symptoms. Self-esteem and social support were negatively correlated with anxiety and depression, respectively. Therefore, comprehensive treatment plans for adolescents with facial burns should include mental health assessments and interventions to improve quality of life and psychological adaptability. Future research should further explore the correlation between interventions to help adolescent patients cope better with psychological challenges following burns.

| 1. | Peck MD. Epidemiology of burns throughout the world. Part I: Distribution and risk factors. Burns. 2011;37:1087-1100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 557] [Cited by in RCA: 710] [Article Influence: 47.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Brewin MP, Homer SJ. The lived experience and quality of life with burn scarring-The results from a large-scale online survey. Burns. 2018;44:1801-1810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Peck MD. Epidemiology of burns throughout the World. Part II: intentional burns in adults. Burns. 2012;38:630-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li J, Zhou L, Wang Y. The effects of music intervention on burn patients during treatment procedures: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17:158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Qin W, Li Y, Wang J, Qi X, Wang RK. In Vivo Monitoring of Microcirculation in Burn Healing Process with Optical Microangiography. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2016;5:332-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dunpath T, Chetty V, Van Der Reyden D. Acute burns of the hands - physiotherapy perspective. Afr Health Sci. 2016;16:266-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tagkalakis P, Demiri E. A fear avoidance model in facial burn body image disturbance. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2009;22:203-207. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Hoogewerf CJ, van Baar ME, Middelkoop E, van Loey NE. Impact of facial burns: relationship between depressive symptoms, self-esteem and scar severity. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:271-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Robert R, Blakeney P, Villarreal C, Meyer WJ 3rd. Anxiety: current practices in assessment and treatment of anxiety of burn patients. Burns. 2000;26:549-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Carrougher GJ, Ptacek JT, Honari S, Schmidt AE, Tininenko JR, Gibran NS, Patterson DR. Self-reports of anxiety in burn-injured hospitalized adults during routine wound care. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:676-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Liu S, Cheng Y, Xie Z, Lai A, Lv Z, Zhao Y, Xu X, Luo C, Yu H, Shan B, Xu L, Xu J. A Conscious Resting State fMRI Study in SLE Patients Without Major Neuropsychiatric Manifestations. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Klietz M, Schnur T, Drexel S, Lange F, Tulke A, Rippena L, Paracka L, Dressler D, Höglinger GU, Wegner F. Association of Motor and Cognitive Symptoms with Health-Related Quality of Life and Caregiver Burden in a German Cohort of Advanced Parkinson's Disease Patients. Parkinsons Dis. 2020;2020:5184084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | BECK AT, WARD CH, MENDELSON M, MOCK J, ERBAUGH J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23191] [Cited by in RCA: 23696] [Article Influence: 846.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Scherer A, Eberle N, Boecker M, Vögele C, Gauggel S, Forkmann T. The negative affect repair questionnaire: factor analysis and psychometric evaluation in three samples. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wu G, Jiang Z, Pu Y, Chen S, Wang T, Wang Y, Xu X, Wang S, Jin M, Yao Y, Liu Y, Ke S, Liu S. Serum short-chain fatty acids and its correlation with motor and non-motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease patients. BMC Neurol. 2022;22:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Alvarenga MGJ, Rebelo MAB, Lamarca GA, Paula JS, Vettore MV. The influence of protective psychosocial factors on the incidence of dental pain. Rev Saude Publica. 2022;56:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | AlHarbi N. Self-Esteem: A Concept Analysis. Nurs Sci Q. 2022;35:327-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Usmani A, Pipal DK, Bagla H, Verma V, Kumar P, Yadav S, Garima G, Rani V, Pipal RK. Prediction of Mortality in Acute Thermal Burn Patients Using the Abbreviated Burn Severity Index Score: A Single-Center Experience. Cureus. 2022;14:e26161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bhatti DS, Ul Ain N, Zulkiffal R, Al-Nabulsi ZS, Faraz A, Ahmad R. Anxiety and Depression Among Non-Facial Burn Patients at a Tertiary Care Center in Pakistan. Cureus. 2020;12:e11347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ward HW, Moss RL, Darko DF, Berry CC, Anderson J, Kolman P, Green A, Nielsen J, Klauber M, Wachtel TL. Prevalence of postburn depression following burn injury. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1987;8:294-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Thombs BD, Notes LD, Lawrence JW, Magyar-Russell G, Bresnick MG, Fauerbach JA. From survival to socialization: a longitudinal study of body image in survivors of severe burn injury. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:205-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | O'Brien KH, Lushin V. Examining the Impact of Psychological Factors on Hospital Length of Stay for Burn Survivors: A Systematic Review. J Burn Care Res. 2019;40:12-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pan W, Liu C, Yang Q, Gu Y, Yin S, Chen A. The neural basis of trait self-esteem revealed by the amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations and resting state functional connectivity. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2016;11:367-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/