Published online Oct 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i10.106312

Revised: April 21, 2025

Accepted: August 7, 2025

Published online: October 19, 2025

Processing time: 188 Days and 23.7 Hours

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that poses a substantial burden on patients' physical health, as well as on their psychological health and quality of life. This study specifically examines active disease phases (excluding spontaneous remission periods) to investigate the efficacy of continuous treat

To evaluate the effectiveness of continuous treatment strategies, including der

A retrospective cohort study was conducted on 120 atopic dermatitis patients treated at our hospital between June 2023 and May 2024. A total of 120 patients were randomly assigned into control and intervention groups (60 patients each). The control group underwent routine treatment, and the intervention group was treated using continuous treatment strategies, including personalized skin care plan, psychological counseling, patient education, and long-term follow-up. Quality of life and psychological status of patients were assessed using the dermatology life quality index and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

At 12 months post-intervention, the dermatology life quality index scores in the intervention group were significantly lower than those in the control group (P < 0.01), implying improved quality of life. The anxiety and depression symptoms were significantly lower in the intervention group when compared to the control group (P < 0.05) as per the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. In the intervention group, the rate of recurrence of skin symptoms was 15% compared to 35% in the control group, with a statistically significant difference between the two groups.

Continuous treatment for atopic dermatitis patients greatly improve their psychological state and quality of life, enhance disease-free survival, and offer new trains of thought for clinical treatment. Personalized integrated management over a prolonged time is important to improve quality of life in such patients.

Core Tip: This retrospective study demonstrates that continuous integrated treatment, including dermatological care, psychological counseling, patient education, and structured follow-up, significantly improves mental health and quality of life in patients with atopic dermatitis. Compared to routine care, the intervention group showed marked reductions in anxiety, depression, perceived stress, and sleep disturbances, along with improved treatment adherence and social functioning. These findings support a paradigm shift toward multidisciplinary, long-term management of atopic dermatitis that addresses both dermatological and psychological needs.

- Citation: Meng YB, Ma YH, Yang Y, Li DD, Zhang RX, Ren CM. Continuous treatment strategies improve psychological status and quality of life in patients with atopic dermatitis. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(10): 106312

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i10/106312.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i10.106312

Atopic dermatitis is not just a skin condition; it is a complex disorder with severe psychological implications that go far beyond visible skin symptoms. Chronic skin inflammation creates a vicious cycle between mind and body. This condition is known to involve a bidirectional communication between the skin and mind; hence, anxiety and depression have become leading psychological complications[1-4]. Epidemiological studies show a remarkable association between atopic dermatitis and psychological distress. The incidence of psychological distress in patients with atopic dermatitis is much higher than that in the general population, with recent meta-analyses suggesting that patients with atopic dermatitis have a 1.5- to 2-fold increased risk of developing clinical depression and anxiety disorders. These skin symptoms often have a persistent nature, establishing an ongoing cycle of psychological vulnerability in which physical symptoms affect the mental state[5-8].

The psychological component of atopic dermatitis is reflected in a variety of ways. Chronic itching with visible skin lesions causes social embarrassment, decreased self-esteem, and social isolation[9-11]. Skin itch is a common chronic skin condition which is associated with mental health issues such as depression, as well as sleep disturbances as a common consequence of chronic skin irritation. Overall, studies show that a considerable portion (up to 60%) of atopic dermatitis patients suffer from clinically significant sleep quality impairment, which is correlated to increased anxiety and depressive symptoms[12-16].

Conventional medical approaches have primarily focused on dermatological facets, but they have frequently overlooked the vital psychological components of the ailment. Such limited understanding misses the comprehensive demands of patients and exposes them to a continuous cycle of mental issues. This bidirectional relationship between skin symptoms and psychological distress indicates that a successful treatment should include steps to treat both physical and mental health aspects.

This study seeks to advance long-term, cumulative care for atopic dermatitis by developing a holistic continuous treatment that considers psychological burden. Combining dermatological therapy with psychological treatment, this study aims to: (1) Assess the prevalence and severity of anxiety and depression in patients with atopic dermatitis; (2) Develop and evaluate a continuous intervention model for psychological symptoms; and (3) Evaluate the impact of comprehensive mental health support in the management of the disease and the quality of life of patients. By elucidating and addressing the complex psychological dimensions of atopic dermatitis, this study may transform treatment paradigms, offering a more empathetic, holistic approach to patient treatment that considers the deep bond between skin health and mental health.

Using a retrospective cohort study design, this work examined the effect of continuous treatment strategies among patients with atopic dermatitis. The study was performed at the dermatology department of our hospital between June 2023 and May 2024, adhering to evidence-based principles while ensuring thorough patient evaluation. The study had rigorous inclusion and exclusion criteria for participant selection. The inclusion criteria were: (1) Definitive diagnostic confirmation of atopic dermatitis based on American Atopic Dermatitis Working Group diagnostic criteria; (2) Age range of 18-65 years (physiological consistency); (3) A minimum disease history of 6 months or longer (requiring chronic disease characteristics); and (4) Signs of voluntary participation/informed consent, and the ability to successfully complete the full follow-up and comprehensive assessment scales. The exclusion criteria included concurrent severe skin diseases, serious pre-existing mental/unanticipated cognitive health disorders, any systemic immunomodulatory treatments taken in the preceding 6 months, and any physical conditions which would render patients unsuitable for long-term medical follow-up, including pregnancy or lactation.

Patients were randomly assigned into control and intervention groups based on the treatments that they received. The control group underwent routine dermatological pharmacological therapy, skin care education, and follow-up. The intervention group received a more comprehensive approach, including skin care management personalized by patients, systematic psychological counseling, a comprehensive patient education program, and longer longitudinal follow-up, as well as a multidisciplinary integrated intervention approach. Cognitive behavioral therapy served as the primary intervention, specifically focusing on breaking the vicious cycle of skin itching-scratching-inflammation. This was supplemented by mindfulness-based stress reduction to help patients cope with stress and anxiety related to chronic skin disease, and disease-specific educational courses to enhance patients’ awareness of atopic dermatitis triggers and self-management abilities. The treatment frequency followed a stepped design: An initial phase consisting of weekly 90-minute cognitive behavioral therapy group sessions lasting 8 weeks; a stabilization phase with monthly 60-minute individual follow-up consultations continuing for 6 months; and a maintenance phase with quarterly check-ups combining dermatological assessment and 30-minute psychological counseling extending to 12 months. All psychological treatments were provided by clinical psychologists trained in psychodermatology, with each therapist responsible for no more than 10 patients to ensure personalized attention.

In this study, we developed a comprehensive psychologic and mental health evaluation system based on multi-dimensional-multi-level metrics to assess psychologic status and longitudinal changes in patients with atopic dermatitis. The assessment framework incorporated multiple domains including emotional state, quality of life, social functioning, and cognitive-behavioral patterns. The main instrument used to assess the emotional state was the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale[17,18]. This scale consists of 14 dimensions that measure anxiety and depression dimensions. Each dimension has 7 items, rated with a four-point scale (0-3), with total scores ranging from 0 to 21. For both the anxiety and the depression subscales, we used a cut-off point of 8 to determine the severity of emotional disturbance. Dynamic changes in emotional states were monitored at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months through regular assessment.

Quality of life assessment was performed according to the dermatology life quality index (DLQI), which is a dermatology-specific patient-reported outcome measure[19-21]. This instrument consists of 10 items covering six dimensions: Symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, work/school, personal relationships, and treatment. Each item is scored on a four-point scale (0-3), with total scores ranging from 0 to 30. The results were categorized into five levels: No effect on quality of life (0-1), small effect (2-5), moderate effect (6-10), very large effect (11-20), and extremely large effect (21-30).

Social functioning was evaluated using the Social Disability Screening Schedule (SDSS), which examines five dimensions: Work/study capability, family life/household duties, social activities, interests/hobbies, and interpersonal relationships. Each dimension is scored on a three-point scale (0-2), with total scores ranging from 0 to 10. Special attention was paid to patients’ performance in social activities and interpersonal relationships to assess the impact of the disease on social functioning.

Cognitive-behavioral assessment focused on patients’ disease cognition, coping strategies, and treatment adherence. We developed a structured cognitive assessment questionnaire covering disease knowledge, treatment expectations, self-management capabilities, and behavioral change readiness. Treatment adherence was measured using the 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8), with scores ranging from 0 to 8, where higher scores indicate better adherence[22,23].

Stress level assessment employed the perceived stress scale (PSS-10) to measure patients’ perceived stress levels over the past month. This 10-item scale uses a five-point scoring system (0-4), with total scores ranging from 0 to 40. Stress levels were categorized as low (0-13), moderate (14-26), and high (27-40)[24-26].

Sleep quality was evaluated using the Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI), which assesses seven components: Subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. Each component is scored from 0 to 3, with total scores ranging from 0 to 21, where higher scores indicate poorer sleep quality.

To ensure assessment reliability and validity, all scale evaluations were conducted by professionally trained psychological assessors. The assessment process strictly followed standardized operating procedures to ensure data accuracy and consistency. Assessment results were not only used for research analysis but also served as important references for treatment plan adjustments, helping clinicians better understand patients’ psychological states and provide personalized comprehensive treatment plans.

For data analysis, we employed repeated measures analysis of variance to evaluate temporal trends in psychological indicators and used multiple regression analysis to explore relationships between psychological factors and disease severity and treatment outcomes. We also examined psychological state differences across demographic characteristics and disease severity levels to provide more targeted intervention recommendations for clinical practice.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0 statistical software, employing a multi-layered analytical approach. Quantitative data are expressed as the mean ± SD, with intergroup comparisons performed using independent sample t-tests, while categorical data were analyzed via χ2 tests, with statistical significance set at P < 0.05. To ensure robust and nuanced data interpretation, the study utilized both parametric and non-parametric tests based on data distribution, conducted multivariate logistic regression for complex factor analysis, generated Kaplan-Meier survival curves, and performed multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis.

Among the 120 participants who completed the study, the intervention group (n = 60) and control group (n = 60) showed comparable baseline characteristics. The mean age was 42.3 ± 11.2 years in the intervention group and 41.8 ± 10.9 years in the control group. Gender distribution was similar between the two groups, with females accounting for 56.7% (34/60) in the intervention group and 55.0% (33/60) in the control group. The mean disease duration was 8.4 ± 3.6 years and 8.2 ± 3.8 years in the intervention and control groups, respectively. No statistically significant differences were observed in baseline demographic characteristics between the two groups (P > 0.05; Table 1).

| Characteristic | Intervention group (n = 60) | Control group (n = 60) | P value |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 42.3 ± 11.2 | 41.8 ± 10.9 | 0.78 |

| Gender (female/male) | 34/26 (56.7) | 33/27 (55.0) | 0.83 |

| Disease duration (years), mean ± SD | 8.4 ± 3.6 | 8.2 ± 3.8 | 0.82 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 24.5 ± 3.2 | 24.8 ± 3.5 | 0.67 |

| Smoking history | 15 (25.0) | 18 (30.0) | 0.56 |

| Alcohol consumption | 10 (16.7) | 12 (20.0) | 0.78 |

| Education level | 30 (50.0) | 32 (53.3) | 0.67 |

| Comorbid hypertension | 18 (30.0) | 20 (33.3) | 0.72 |

| Comorbid diabetes mellitus | 12 (20.0) | 14 (23.3) | 0.68 |

| Family history of cardiovascular disease | 10 (16.7) | 11 (18.3) | 0.85 |

| Baseline systolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean ± SD | 125 ± 15 | 127 ± 16 | 0.69 |

| Baseline diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean ± SD | 80 ± 10 | 81 ± 11 | 0.74 |

| Baseline heart rate (beats/minute), mean ± SD | 75 ± 10 | 76 ± 11 | 0.80 |

The intervention group demonstrated significantly greater improvement in clinical symptoms compared to the control group at both 6 months and 12 months. At the 12-month follow-up, the mean severity score decreased from 18.6 ± 4.2 to 7.3 ± 2.8 in the intervention group, compared to a reduction from 18.4 ± 4.1 to 11.2 ± 3.5 in the control group (P < 0.001). The intervention group also showed a lower disease recurrence rate (15.0% vs 35.0%, P < 0.01) and shorter duration of acute flares (4.2 ± 1.5 days vs 7.8 ± 2.3 days, P < 0.001; Table 2).

| Indicator | Intervention group (n = 60) | Control group (n = 60) | P value |

| Mean severity score at baseline | 18.6 ± 4.2 | 18.4 ± 4.1 | 0.85 |

| Mean severity score at 12 months | 7.3 ± 2.8 | 11.2 ± 3.5 | < 0.001 |

| Reduction in severity score | 11.3 ± 3.5 | 7.2 ± 3.2 | < 0.001 |

| Disease recurrence rate (%) | 15.0 | 35.0 | < 0.01 |

| Duration of acute flares (days) | 4.2 ± 1.5 | 7.8 ± 2.3 | < 0.001 |

| QoL | 85 ± 10 | 75 ± 12 | < 0.05 |

| Symptom improvement rate (%) | 80.0 | 50.0 | < 0.001 |

| Patient satisfaction score (%) | 90.0 | 70.0 | < 0.001 |

| Frequency of acute flares (times/month) | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | < 0.001 |

| Medication use reduction (%) | 60.0 | 30.0 | < 0.001 |

| Sleep quality score | 80 ± 10 | 70 ± 12 | < 0.05 |

| Physical activity level (MET-min/week) | 1500 ± 300 | 1000 ± 200 | < 0.05 |

Analysis of DLQI scores revealed substantial improvements in the intervention group. The mean DLQI score decreased from 16.8 ± 3.9 at baseline to 5.2 ± 2.1 at 12 months in the intervention group, while the control group showed a more modest reduction from 16.5 ± 3.8 to 9.6 ± 2.8 (P < 0.001). Notably, 75% of intervention group patients achieved a DLQI score ≤ 5 (indicating minimal impact on quality of life) by study end, compared to only 45% in the control group (Table 3).

| Indicator | Intervention group (n = 60) | Control group (n = 60) | P value |

| Mean DLQI score at baseline | 16.8 ± 3.9 | 16.5 ± 3.8 | 0.76 |

| Mean DLQI score at 12 months | 5.2 ± 2.1 | 9.6 ± 2.8 | < 0.001 |

| Reduction in DLQI score | 11.6 ± 3.2 | 6.9 ± 2.9 | < 0.001 |

| Percentage of patients with DLQI ≤ 5 at 12 months (%) | 75 | 45 | < 0.001 |

| Additional indicators | |||

| SF-36 PCS | 80 ± 10 | 70 ± 12 | < 0.05 |

| SF-36 MCS | 82 ± 11 | 72 ± 13 | < 0.05 |

| EQ-5D health state score | 0.85 ± 0.10 | 0.75 ± 0.12 | < 0.05 |

| Pain interference score (0-10 scale) | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 4.0 ± 1.5 | < 0.001 |

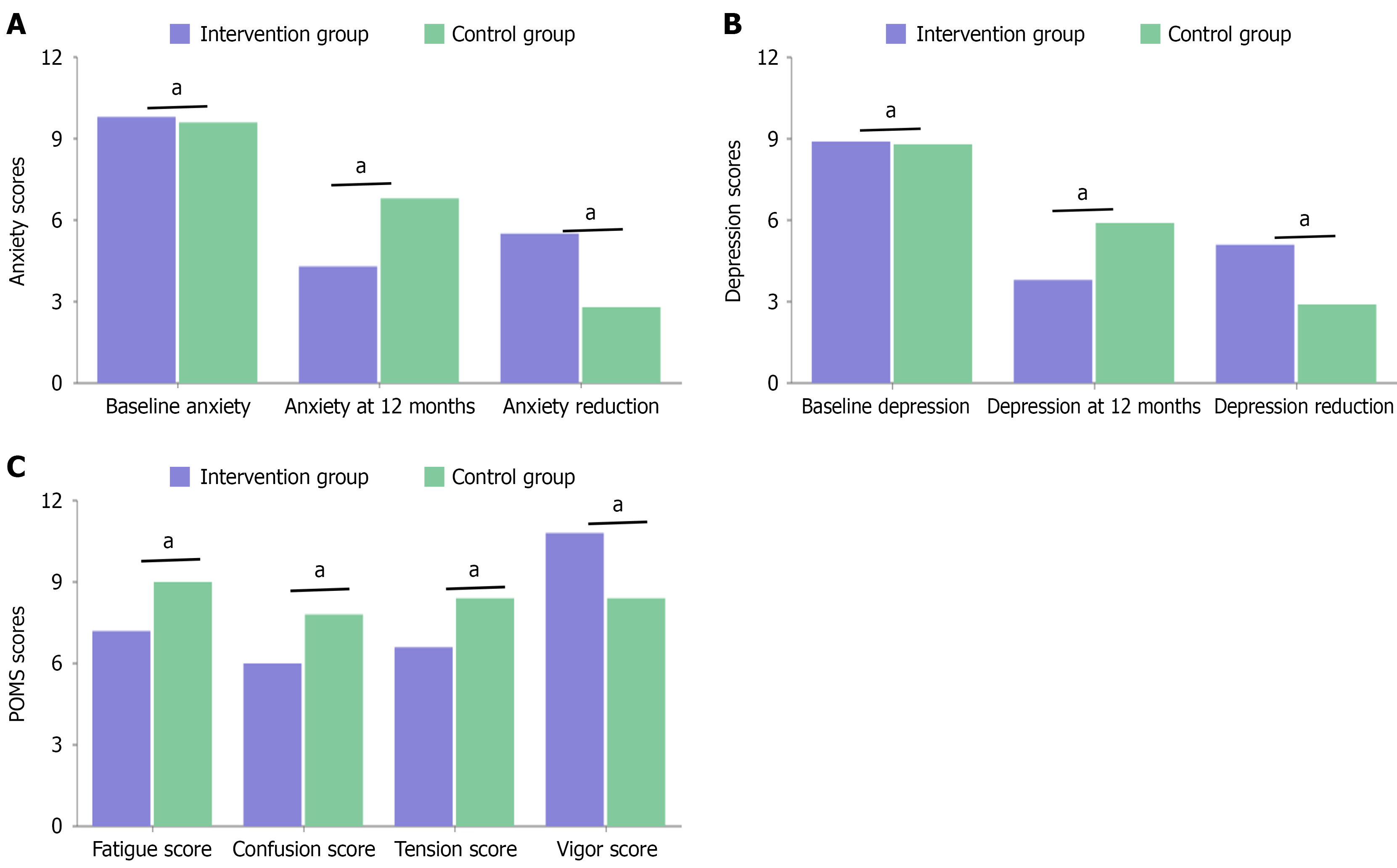

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale results showed significant improvements in both anxiety and depression scores in the intervention group. The mean anxiety score decreased from 9.8 ± 2.7 to 4.3 ± 1.9 in the intervention group, compared to 9.6 ± 2.8 to 6.8 ± 2.2 in the control group (P < 0.001). Similarly, depression scores improved from 8.9 ± 2.5 to 3.8 ± 1.7 in the intervention group vs 8.8 ± 2.6 to 5.9 ± 2.0 in the control group (P < 0.001; Figure 1).

Social functioning showed marked improvement in the intervention group as measured by the SDSS. The mean total SDSS score improved from 7.2 ± 1.8 to 2.8 ± 1.1 in the intervention group, compared to 7.1 ± 1.9 to 4.5 ± 1.4 in the control group (P < 0.001). Particularly notable improvements were observed in social activities and interpersonal relationships dimensions, with 82% of intervention group patients reporting improved social engagement compared to 55% in the control group (Table 4).

| Indicator | Intervention group (n = 60) | Control group (n = 60) | P value |

| Mean total SDSS score at baseline | 7.2 ± 1.8 | 7.1 ± 1.9 | 0.81 |

| Mean total SDSS score at 12 months | 2.8 ± 1.1 | 4.5 ± 1.4 | < 0.001 |

| Reduction in total SDSS score | 4.4 ± 1.5 | 2.6 ± 1.3 | < 0.001 |

| Percentage of patients with improved social engagement (%) | 82 | 55 | < 0.001 |

| Social activities score | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 5.0 ± 1.2 | < 0.001 |

| Interpersonal relationships score | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 4.0 ± 1.3 | < 0.001 |

| Work performance score | 2.8 ± 1.1 | 4.2 ± 1.4 | < 0.001 |

| Family life score | 2.7 ± 1.0 | 4.0 ± 1.2 | < 0.001 |

| Additional indicators | |||

| PMHS-C | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | < 0.001 |

| Social support score | 8.0 ± 1.5 | 6.5 ± 1.8 | < 0.001 |

| Community participation score | 7.5 ± 1.2 | 5.8 ± 1.5 | < 0.001 |

| Psychological resilience score | 8.2 ± 1.3 | 6.8 ± 1.6 | < 0.001 |

Treatment adherence rates, as measured by the MMAS-8, were significantly higher in the intervention group throughout the study period. The mean adherence score increased from 5.8 ± 1.4 to 7.4 ± 0.8 in the intervention group, while the control group showed a minimal change from 5.7 ± 1.3 to 6.1 ± 1.1 (P < 0.001). The intervention group also demonstrated superior self-management capabilities, with 85% of patients correctly implementing skin care protocols compared to 60% in the control group (Table 5).

| Indicator | Intervention group (n = 60) | Control group (n = 60) | P value |

| Mean MMAS-8 score at baseline | 5.8 ± 1.4 | 5.7 ± 1.3 | 0.74 |

| Mean MMAS-8 score at 12 months | 7.4 ± 0.8 | 6.1 ± 1.1 | < 0.001 |

| Increase in MMAS-8 score | 1.6 ± 1.0 | 0.4 ± 0.8 | < 0.001 |

| Percentage of patients with high adherence (MMAS-8 ≥ 6) | 85% | 60% | < 0.001 |

| Self-management of medications (%) | 90 | 70 | < 0.001 |

| Adherence to follow-up appointments (%) | 95 | 80 | < 0.001 |

| Implementation of lifestyle changes (%) | 80 | 55 | < 0.001 |

| Correct implementation of skin care protocols (%) | 85 | 60 | < 0.001 |

| Knowledge of disease management (%) | 88 | 65 | < 0.001 |

| Adherence to dietary recommendations (%) | 82 | 58 | < 0.001 |

| Engagement in regular physical activity (%) | 75 | 50 | < 0.001 |

Sleep quality, assessed using PSQI, showed significant improvement in the intervention group. The mean PSQI score decreased from 10.2 ± 2.9 to 4.8 ± 1.6 in the intervention group, compared to 10.1 ± 2.8 to 7.3 ± 2.1 in the control group (P < 0.001). Perceived stress levels, measured by PSS-10, also showed a greater reduction in the intervention group (from 25.4 ± 5.2 to 12.6 ± 3.8) compared to the control group (from 25.2 ± 5.1 to 18.4 ± 4.5, P < 0.001, Table 6).

| Indicator | Intervention group (n = 60) | Control group (n = 60) | P value |

| Mean PSQI score at baseline | 10.2 ± 2.9 | 10.1 ± 2.8 | 0.82 |

| Mean PSQI score at 12 months | 4.8 ± 1.6 | 7.3 ± 2.1 | < 0.001 |

| Reduction in PSQI score | 5.4 ± 2.3 | 2.8 ± 2.0 | < 0.001 |

| Mean PSS-10 score at baseline | 25.4 ± 5.2 | 25.2 ± 5.1 | 0.85 |

| Mean PSS-10 score at 12 months | 12.6 ± 3.8 | 18.4 ± 4.5 | < 0.001 |

| Reduction in PSS-10 score | 12.8 ± 4.1 | 6.8 ± 3.9 | < 0.001 |

| Percentage of patients with good sleep quality (PSQI ≤ 5) | 70% | 40% | < 0.001 |

| Percentage of patients with low stress levels (PSS-10 ≤ 10) | 65% | 35% | < 0.001 |

| Sleep latency (minutes) | 20 ± 10 | 35 ± 15 | < 0.001 |

| Sleep duration (hours) | 7.5 ± 0.8 | 6.2 ± 1.0 | < 0.001 |

Atopic dermatitis, as a chronic inflammatory skin condition, has impacts far beyond cutaneous symptoms, profoundly affecting patients’ psychological health and mental state. Research indicates that atopic dermatitis patients face significantly increased mental health risks, with anxiety and depression rates 1.5 times to 2 times higher than the general population. The formation of this psychological burden involves multiple complex factors and mechanisms[27-29].

First, chronic pruritus and visible skin lesions directly affect patients’ psychological state. Persistent itching not only causes physical discomfort but also leads to decreased sleep quality, irritability, and difficulty concentrating. Changes in skin appearance often trigger self-image concerns, resulting in lowered self-esteem and social avoidance tendencies. Studies have found that approximately 60% of atopic dermatitis patients report significant sleep problems, with this decline in sleep quality showing a close bidirectional association with anxiety and depressive symptoms[9,30,31].

Our research results demonstrate that an integrated continuous treatment approach significantly improved the psychological health of atopic dermatitis patients, highlighting the importance of addressing mental health in dermatological treatment. The intervention group showed significant reductions in both anxiety and depression scores (anxiety decreased from 9.8 ± 2.7 to 4.3 ± 1.9; depression from 8.9 ± 2.5 to 3.8 ± 1.7), while the control group showed limited improvement. These findings align with previous research reporting high rates of anxiety and depression in atopic dermatitis patients, while confirming that targeted psychological interventions can effectively alleviate these symptoms. The magnitude of improvement suggests that psychological symptoms are not merely secondary to skin manifestations but represent an independent therapeutic target that can be significantly improved through specialized intervention.

Quality of life assessment showed significant improvement in the intervention group, with DLQI scores decreasing from 16.8 ± 3.9 at baseline to 5.2 ± 2.1 at 12 months. Notably, 75% of patients in the intervention group achieved minimal impact on quality of life (DLQI ≤ 5), compared to only 45% in the control group. This improvement closely correlates with enhanced social functioning, as evidenced by SDSS score improvements (from 7.2 ± 1.8 to 2.8 ± 1.1). The significant increase in social engagement (82% vs 55%) indicates that addressing psychological issues enables patients to better overcome social barriers associated with visible skin conditions.

The unpredictability and recurrent nature of the disease create persistent psychological pressure for patients. Patients often live with constant worry about disease recurrence, and this long-term uncertainty leads to chronic stress states. Clinical observations have identified a clear vicious cycle between stress and disease exacerbation: Psychological stress can trigger or worsen skin symptoms, while symptom aggravation further intensifies psychological burden. Research data shows that during acute disease flares, patients’ stress levels and anxiety significantly increase, with PSS-10 scores reaching above 25[32].

Sleep quality and stress level improvements were particularly notable. The intervention group’s PSQI scores decreased from 10.2 ± 2.9 to 4.8 ± 1.6, and PSS-10 scores from 25.4 ± 5.2 to 12.6 ± 3.8, revealing the effectiveness of continuous treatment in breaking the bidirectional relationship between sleep disturbance and psychological distress. Seventy percent of patients in the intervention group achieved good sleep quality compared to 40% in the control group, indicating that psychological support plays a crucial role in breaking the vicious cycle of stress, poor sleep quality, and symptom exacerbation.

These results emphasize that psychological treatment should be a core component of standard atopic dermatitis treatment protocols, not an optional add-on. Comprehensive improvement across multiple psychological domains indicates that continuous integrated psychological support produces better treatment outcomes than conventional dermatological care alone. This improvement may be achieved through multiple mechanisms: Psychological support enhances emotional regulation, thereby reducing stress-induced inflammation; improved sleep quality promotes immune function and skin barrier repair; addressing psychological barriers improves self-care adherence; and reduced social anxiety leads to improved quality of life and disease management.

Although our research results show significant psychological improvement, several issues warrant further investigation: The long-term sustainability of psychological improvements beyond the 12-month study period; the potential role of specific psychological interventions in preventing disease recurrence; the cost-effectiveness of integrating psychological support in routine clinical practice; and identifying patient subgroups who might benefit most from intensive psychological support. These findings support a paradigm shift in atopic dermatitis treatment, emphasizing the necessity of integrated treatment in addressing both physical and psychological impacts of the disease. Future research should focus on optimizing psychological intervention protocols and identifying predictors of psychological treatment response.

This study provides new insights and empirical evidence for the comprehensive treatment of atopic dermatitis, emphasizing the central role of psychological intervention in disease management. This integrated treatment model not only improves patients’ psychological health but also enhances overall recovery, improves treatment outcomes, and ultimately achieves better clinical prognosis.

| 1. | Ahmad R, Khan S, Khan A, Arshad F, Naveed F. Critical insights on "Factors associated with comorbidity development in atopic dermatitis: a cross-section study". Arch Dermatol Res. 2025;317:345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Guttman-Yassky E, Katoh N, J Cork M, Jagdeo J, F Alexis A, Chen Z, A Levit N, B Rossi A. Dupilumab Treatment Improves Lichenification in Atopic Dermatitis in Different Age and Racial Groups. J Drugs Dermatol. 2025;24:167-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lv F, Chen Y, Xie H, Gao M, He R, Deng W, Chen W. Therapeutic potential of phloridzin carbomer gel for skin inflammatory healing in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2025;317:352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Napolitano M, Esposito M, Fargnoli MC, Girolomoni G, Romita P, Nicoli E, Matruglio P, Foti C. Infections in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis and the Influence of Treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2025;26:183-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Alessandrello C, Sanfilippo S, Minciullo PL, Gangemi S. An Overview on Atopic Dermatitis, Oxidative Stress, and Psychological Stress: Possible Role of Nutraceuticals as an Additional Therapeutic Strategy. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:5020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nielsen ML, Nymand LK, Pena AD, Du Jardin KG, Kasujee I, Thomsen SF, Egeberg A, Thein D. Psychological impact on flare patterns and severity of atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025;39:e644-e646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Singleton H, Hodder A, Almilaji O, Ersser SJ, Heaslip V, O'Meara S, Boyers D, Roberts A, Scott H, Van Onselen J, Doney L, Boyle RJ, Thompson AR. Educational and psychological interventions for managing atopic dermatitis (eczema). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024;8:CD014932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhao Q, Tominaga M, Toyama S, Komiya E, Tobita T, Morita M, Zuo Y, Honda K, Kamata Y, Takamori K. Effects of Psychological Stress on Spontaneous Itch and Mechanical Alloknesis of Atopic Dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2024;104:adv18685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lee HJ, Lee GN, Lee JH, Han JH, Han K, Park YM. Psychological Stress in Parents of Children with Atopic Dermatitis: A Cross-sectional Study from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Acta Derm Venereol. 2023;103:adv00844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lönndahl L, Abdelhadi S, Holst M, Lonne-Rahm SB, Nordlind K, Johansson B. Psychological Stress and Atopic Dermatitis: A Focus Group Study. Ann Dermatol. 2023;35:342-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lugović-Mihić L, Meštrović-Štefekov J, Pondeljak N, Dasović M, Tomljenović-Veselski M, Cvitanović H. Psychological Stress and Atopic Dermatitis Severity Following the COVID-19 Pandemic and an Earthquake. Psychiatr Danub. 2021;33:393-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hosono S, Fujita K, Nimura A, Ibara T, Akita K. Cervical Spine Range of Motion and Sleep Disturbances in Patients With Atopic Dermatitis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus. 2024;16:e75449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lim JA, Jamil A, Arumugam M, Kueh YC. Atopic dermatitis - Impact on sleep, work performance and its associated costs: A cross-sectional study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2024;1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Simpson EL, Hebert AA, Browning J, Serrao RT, Sofen H, Brown PM, Piscitelli SC, Rubenstein DS, Tallman AM. Tapinarof Improved Outcomes and Sleep for Patients and Families in Two Phase 3 Atopic Dermatitis Trials in Adults and Children. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2025;15:111-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sussex AK, Rencz F, Gaydon M, Lloyd A, Gallop K. Exploring the content validity of the EQ-5D-5L and four bolt-ons (skin irritation, self-confidence, sleep, social relationships) in atopic dermatitis and chronic urticaria. Qual Life Res. 2025;34:991-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yosipovitch G, de Bruin-Weller M, Wiseman M, Elberling J, Gutermuth J, Pierce E, Montmayeur S, Yang FE, Ding Y, Bardolet L, Chisolm S. Improved quality of life in patients treated with lebrikizumab monotherapy is mediated by improvements in itch and sleep: results from two phase III trials in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2025;50:1188-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Faltracco V, Pain D, Dalla Bella E, Riva N, Telesca A, Soldini E, Gandini G, Radici A, Poletti B, Lauria G, Consonni M. Mood disorders in patients with motor neuron disease and frontotemporal symptoms: Validation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale for use in motor neuron disease. J Neurol Sci. 2025;469:123378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Simão DO, Santos AVMP, Vieira VS, Reis FM, Cândido AL, Comim FV, Tosatti JAG, Gomes KB. Anxiety and Depression in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: An Analysis Using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in Women from a Low-Income Country. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2025;133:105-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dalimunthe DA, Hazlianda CP, Lubis FM, Sinaga RM, Salim S. Correlation of skin moisture and serum urea level with dermatology life quality index in patients with chronic kidney disease on hemodialysis: A cross-sectional study. Narra J. 2024;4:e967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jensen MB, Loft N, Zacheriae C, Skov L. Sex Differences in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) among Patients with Psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2024;104:adv42441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sanclemente G, Mora-Gaviria C, Aguirre-Acevedo DC. Rasch Analysis of the Dermatology Life Quality Index. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2025;116:349-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Al-Ani A, Al Suleimani Y, Ritscher S, Toennes SW, Al-Hashar A, Al-Zakwani I, Al Za'abi M, Al Hashmi K. Adherence to antihypertensive medications in Omani patients: a comparison of drug biochemical analysis and the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale. J Hypertens. 2025;43:205-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Isabelle A, Corina M, Kurt H, Michael O, Samuel A. The 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale translated in German and validated against objective and subjective polypharmacy adherence measures in cardiovascular patients. J Eval Clin Pract. 2024;30:582-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kornienko DS, Rudnova NA, Veraksa AN, Gavrilova MN, Plotnikova VA. Exploring the use of the perceived stress scale for children as an instrument for measuring stress among children and adolescents: a scoping review. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1470448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Schmalbach B, Ernst M, Brähler E, Petrowski K. Psychometric comparison of two short versions of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) in a representative sample of the German population. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1479701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zhang Z, Wang Q. Psychometric properties of the perceived stress scale (PSS-10) among pregnant women in China. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:1493341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Pink AE, Weidinger S, Chan G, Biswas P, Clibborn C, Güler E. Switching from Dupilumab to Abrocitinib in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis: A Post Hoc Analysis of Efficacy After Treatment With Dupilumab in JADE DARE. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2025;15:367-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | van der Rijst LP, Veldhuis N, van der Kamp S, Achten RE, van Luijk CM, Voskuil-Kerkhof ESM, Haeck IM, de Bruin-Weller MS, de Graaf M. Ocular surface disease in pediatric patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2025;36:e70040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | von Kobyletzki L, Svensson Å. Patient-reported outcome measures are urgently needed for patients with skin of colour who have atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2025;192:790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ali Z, Valk T, Isberg A, Szpirt M, Dutei AM, Thomsen SF, Eiken A, Allerup J, Bjerre-Christensen T, Derchansky M, Andersen AD, Zibert J. Exploring the association between voice biomarkers, psychological stress and disease severity in atopic dermatitis: A 12-week decentralized study using patients' own smartphones. Skin Res Technol. 2022;28:882-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Miniotti M, Ribero S, Mastorino L, Ortoncelli M, Gelato F, Bailon M, Trioni J, Stefan B, Quaglino P, Leombruni P. Long-term psychological outcome of patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis continuously treated with Dupilumab: Data up to 3 years. Exp Dermatol. 2023;32:852-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Quattrini L, Chiricozzi A, Gori N, DI Nardo L, D'Urso DF, Malvaso D, Cornacchia L, Catapano S, Peris K. The psychological burden during COVID-19 pandemic in a cohort of patients affected by moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab. Ital J Dermatol Venerol. 2023;158:365-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |