Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.107570

Revised: April 11, 2025

Accepted: May 27, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 247 Days and 21.4 Hours

Administration of thrombolytics for acute ischemic stroke (AIS) via telemedicine has expanded in recent years at institutions without on-site neurology specialists. This helped to improve the care of stroke patients in rural areas. However, it is uncertain if telemedicine-administered thrombolytics is as safe and effective as in-person evaluation by neurology specialists.

The authors conducted a meta-analysis evaluating stroke metrics, safety and outcomes of telemedicine compared to in-person evaluation by neurologist specialist in AIS patients receiving intravenous thrombolytics.

PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane were searched for randomized clinical trials and observational cohort studies. The Mantel-Haenszel method or inverse vari

Eleven retrospective cohort studies involving 2350 patients were included in the analysis. Of those, 34% (n = 794) received thrombolytics via telemedicine. Teleme

The available literature suggests that telemedicine is associated with longer DTN compared to in-person evaluation. This difference in stroke metric does not affect safety or outcome. Further studies are needed to understand and address the underlying factors of the longer DTN time.

Core Tip: In this meta-analysis, we compared telemedicine technology to in-person evaluation for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke, highlighting the differences in door-to-needle time (DTN) between the two modalities, and the impact of them on outcomes. The literature suggests that the stroke metric, in terms of DTN, is longer by telemedicine modality of evaluation. However, this difference does not translate in differences in safety and outcomes.

- Citation: Loggini A, Schwertman A, Hornik J, Dallow K, Hornik A. Stroke metrics, safety, and outcomes of telemedicine-administered thrombolytics for acute ischemic stroke: A meta-analysis. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(4): 107570

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i4/107570.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.107570

The utilization of telemedicine has revolutionized acute stroke care, particularly in remote and underserved areas where access to on-site specialists is limited[1-6]. Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) management, including the administration of thrombolytic therapy, centers on fast and precise decision-making to improve outcomes[7-9]. While telemedicine provides a promising solution to bridge the gap between specialized care and resource-limited settings and its benefit over acute stroke management without neurology consultation is well established, uncertainty persist regarding its effectiveness and safety compared to traditional in-person evaluations by neurologists[10,11]. This meta-analysis seeks to evaluate the stroke metrics, safety, and outcomes of thrombolytic therapy administered via telemedicine compared to in-person neurologist evaluation. By investigating as primary outcome such the door-to-needle time (DTN) and secondary outcomes as symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (sICH), mortality, and favorable short-term functional outcomes (mRS ≤ 2), this study aims to summarize the clinical implications of telemedicine in AIS care.

This meta-analysis was conducted and presented in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement[12,13]. Ethical approval was not required because data was extrapolated from previously published studies.

This meta-analysis aimed at evaluating the stroke metrics, safety and outcomes of telemedicine vs in-person evaluation of AIS patients treated with thrombolytics. The primary outcome examined was DTN. Additional outcomes were: (1) sICH; (2) Mortality; and (3) Favorable short-term outcome, defined as mRS ≤ 2 within 3 months.

Three major databases (PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane) were searched from inception to November 13, 2024 using the following keywords “telemedicine” or “telestroke” or “telehealth” in association with “stroke”. The search strategy is available in Supplementary material. Reference lists were searched manually for additional sources.

The articles that were identified from the literature search were screened by two authors (Andrea Loggini and Jonatan Hornik) independently, as per the following inclusion criteria: (1) Adult population with AIS receiving intravenous thrombolytics; (2) Intervention comparing telemedicine to in-person evaluation by neurology specialist; and (3) Outcomes focused on: (1) DTN; (2) Sich; (3) Mortality; and (4) Favorable short-term outcome. Favorable short-term outcome was defined as reported mRS ≤ 2 within 90 days from the stroke. Randomized clinical trials and observational cohort studies were included in the review. Detailed information on participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and types of studies are provided in Table 1. The relevance of the studies was assessed using a stepwise approach based on title, abstract, and full manuscript.

| Participants | Interventions | Comparison | Outcomes | Study types |

| Age > 18 years; acute stroke patients receiving intravenous thrombolytics | Intervention group: Telemedicine (audio and video) evaluation by neurology specialist | Control group: In-person evaluation by neurology specialist | Primary outcome: Door-to-needle time. Secondary outcomes: sICH; mortality; mRS ≤ 2; only studies evaluating one or more of these outcomes | RCT; observational cohort study |

Risk of bias was computed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) by two authors (Andrea Loggini and Jonatan Hornik), independently[12-14]. Disagreement between quality of the study was resolved by senior author (Alejandro Hornik).

For each included study, the following variables were extracted independently by two authors (Andrea Loggini and Jonatan Hornik): First author, publication date, study design, number of participants for the intervention group (telemedicine) and control group (in-person), DTN, events of sICH, mortality, and mRS ≤ 2 for each group. If any of the above variables were not available in the full text publication, further information was sought by correspondence with the lead author of the study.

The Mantel-Haenszel method was used to calculate the overall odds ratio (OR) estimate of telemedicine evaluation for each dichotomous outcome. The inverse variance method was analyzed to calculate the overall standard mean difference (SMD) for the continuous outcome (DTN). Random effect was applied when the definition of the index outcome was dissimilar among the studies. For continuous variables that were presented as median and interquartile range, conversion to mean and standard deviation was obtained by using the method for unknown non-normal distributions[15]. A Z test was carried out to assess the significance of overall OR or SMD for each outcome. The I2 was calculated by χ2 test to assess variability due to heterogeneity rather than chance. A substantial heterogeneity was assumed with I2 > 50%. 95% confidence interval (CI) for each outcome was calculated with the Wilson method and placed in forest plots. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.3[16].

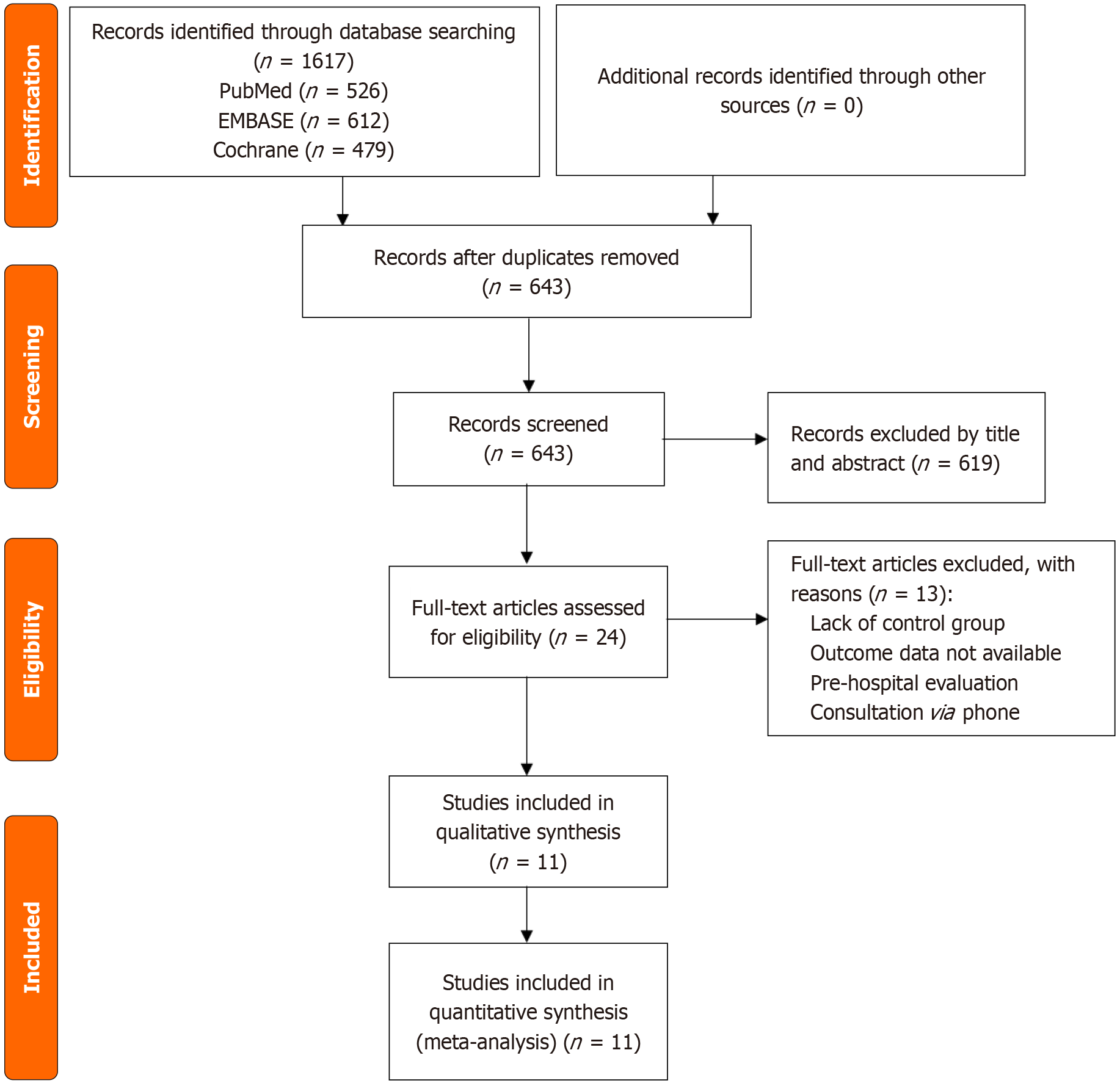

A total of 1617 studies were identified through database searching, including PubMed (n = 526) EMBASE (n = 612), and Cochrane (n = 479). After removing 974 duplicates, the remaining studies (n = 643) were screened for eligibility. A total of 619 records were excluded by title and by abstract. As a result, 24 studies were assessed with full-text review. Among those, 13 articles were excluded due to lack of a control group, lack of outcome data, pre-hospital evaluation, and consultation via phone. Eleven studies were included in the qualitative synthesis, and a meta-analysis was performed for each outcome measure[17-27]. The detailed PRISMA flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

The combined dataset of all studies included a total of 2350 AIS patients treated with thrombolytics, of whom 34% (n = 794) were evaluated via telemedicine. No randomized controlled trials were identified; all works were retrospective cohort studies[17-27]. Four studies were conducted in the United States[18,24,26,27], one study in Canada[23], one study in China[20], one study in France[19], one study in Germany[25], one study in Italy[21], one study in Taiwan[22], and one study in the United Kingdom[17]. The definition and use of telemedicine technology was homogeneous in all the studies, entailing double audio and video communication by the remote provider. One study included only stroke patients with large vessel occlusion[25]. Favorable outcome (defined as mRS ≤ 2) was evaluated at 90 days in six studies[17,19,21,22,26,27], at 30 days in one study[18], and at discharge in one study[25]. The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 2.

| Ref. | Country | Telemedicine | In-person | DTN, in minutes | sICH | Mortality | Favorable short-term outcome |

| Loggini et al[6], 2024 | United States | n = 142 | n = 97 | TM: 55 (43-73); IP: 42 (35-54) | TM: 3; IP: 3 | TM: 8; IP: 9 | TM: 98; IP: 60 |

| Ho et al[23], 2024 | Canada | n = 55 | n = 247 | TM: 35.5 ± 12.7; IP: 34 ± 15.9 | TM: 0; IP: 4 | TM: 7; IP: 40 | - |

| Riegler et al[25], 2023 | Germany | n = 50 | n = 42 | TM: 65 (43-78); IP: 37 (25-51) | TM: 10; IP: 10 | TM: 15; IP: 8 | TM: 4; IP: 15 |

| Lin et al[22], 2022 | Taiwan | n = 25 | n = 153 | TM: 62 (53-78); IP: 51 (41-65) | TM: 1; IP: 5 | TM: 4; IP: 14 | TM: 15; IP: 91 |

| Zhang et al[20], 2020 | China | n = 235 | n = 588 | TM: 62 ± 12; IP: 47 ± 8 | - | - | - |

| Sobhani et al[27], 2021 | United States | n = 55 | n = 77 | TM: 56.8; IP: 41.5 | - | - | TM: 29/44; IP: 27/57 |

| Asaithambi et al[24], 2017 | United States | n = 52 | n = 65 | TM: 54 (41-72); IP: 43 (35-55) | TM: 0; IP: 1 | TM: 2; IP: 1 | - |

| Nardetto et al[21], 2016 | Italy | n = 25 | n = 106 | TM: 73 (98-121); IP: 95 (82-125) | TM: 2; IP: 3 | - | TM: 12; IP: - |

| Raulot et al[19], 2015 | France | n = 27 | n = 70 | TM: 86 (63-94); IP: 55 (45-64) | TM: 1; IP: 5 | - | TM: 8; IP: 22 |

| Chowdhury et al[17], 2012 | United Kingdom | n = 45 | n = 52 | TM: 61; IP: 33 | TM: 2; IP: 4 | - | TM: 19 IP: 19 |

| Zaidi et al[26], 2011 | United States | n = 83 | n = 59 | TM: 89.9 ± 36.3; IP: 67.8 ± 26.1 | TM: 1; IP: 3 | TM: 18; IP: 26 | TM: 22; IP: 35 |

The summary of the risk of bias for each of the outcomes is listed in Supplementary Tables 1-4. Their overall quality was acceptable, ranging on the NOS from 7/9 to 9/9 (9/9 being the highest study quality). Specifically, five studies had moderate risk of bias for comparability of the cohorts[19-21,23,24] and one study had moderate risk of bias for follow up availability[27].

The presence of publication bias was visually assessment for asymmetry in funnel plots for each outcome, and no significant asymmetry was observed, indicating no significant risk of publication bias. (Supplementary Figures 1-4).

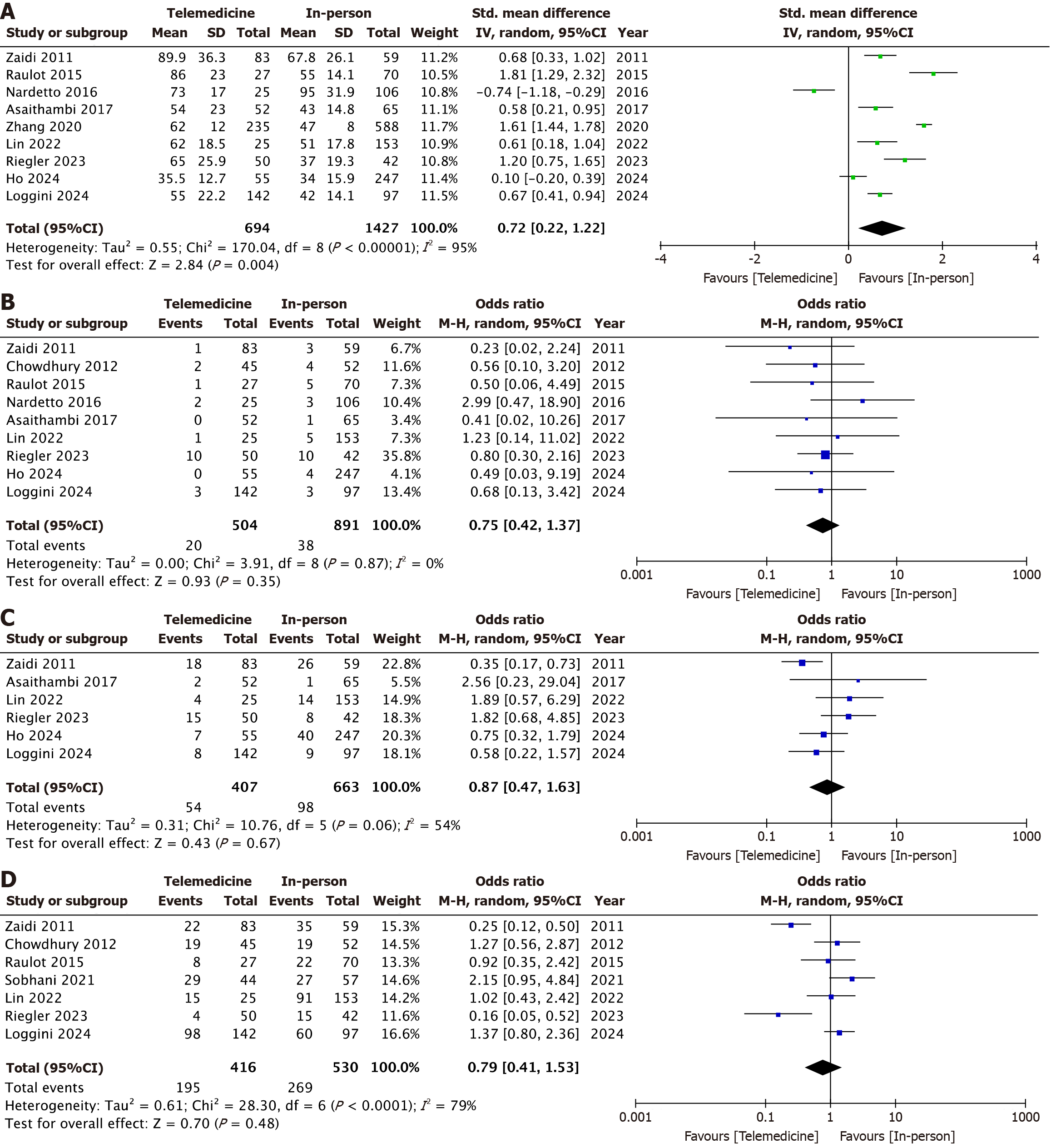

Telemedicine was associated with a significantly longer mean DTN compared to in-person evaluation (SMD: 0.72; 95%CI: 0.22-1.22; I2 = 95%, P < 0.01), a similar rate of sICH (3.9% vs 4.2%; OR: 0.75; 95%CI: 0.42-1.37; I2 = 0%, P = 0.35), similar rate of mortality (13.2% vs 14.7%; OR: 0.87; 95%CI: 0.47-1.63; I2 = 54%, P = 0.67), and comparable rate of favorable short-term functional outcome (46.8% vs 50.7%; OR: 0.79; 95%CI: 0.41-1.53; I2 = 79%, P = 0.48). Foster plots for each outcome are presented in Figure 2.

A sensitivity analysis on the DTN outcome was conducted by excluding studies one by one. After removing the study of Zhang et al[20], the heterogeneity was decreased (I2 = 91%) without affecting the result (SMD: 0.6, 95%CI: 0.18-1.03, P < 0.01).

In this meta-analysis, we summarized the available literature regarding the stroke metrics, safety, and outcomes of thrombolytics administered via telemedicine compared to in-person evaluation and found a significant longer DTN in thrombolytics administered via telemedicine, without differences in safety or outcome.

The majority of included studies have been published within the last three years, reflecting the rapid expansion of telemedicine technology in acute stroke care, and the growing interest in this area.

A recent meta-analysis on this similar topic found no significant difference in DTN between telemedicine and in-person evaluation, with comparable safety and outcomes measures[10]. However, two main limitations to their design. Primo, the telemedicine group included phone consultations. This rendered the group heterogeneous and did not directly measure the effect of telemedicine technology, which requires a two-way audio and video connection to be utilized. Secondo, the in-person evaluation was conducted, in some of their included studies, by non-neurology trained providers, introducing another element of variability and incomparability between the two groups. These factors likely confounded their results, as the impact of telemedicine technology with full audio-visual capabilities was not isolated. By addressing these issues, this meta-analysis applied stringent inclusion criteria to focus exclusively on telemedicine using two-way audio-video connections and in-person evaluations conducted by neurology specialists. As a result, this study offers a clearer perspective on the effects of telemedicine on stroke metrics.

The observed longer DTN with telemedicine evaluation was consistently robust across individual studies and significant in the pooled effect analysis. Surprisingly, more recent studies did not show a decreasing trend in this metric, as might be expected with improvements in technology and provider experience. This finding suggests that multiple factors may contribute to the observed delay. Before elaborating of possible explanations for this finding, it is necessary to establish a premise. Telemedicine is a promising novel technology, still at the embryonic stage of its development and potential. Its application in the acute stroke setting is mostly reserved in rural areas where on site neurology-trained specialists are not available. Bearing this in mind, the longer DTN, which translates to a longer patient evaluation - assuming the other variables included in the DTN constant - can be attributed to the technology itself, the experience of the provider, and the hospital system. The technology, connectivity, and resolution of the video by telemedicine could account for a longer patient evaluation. Provider familiarity and expertise in exploiting the technology at its best to conduct the neurological exam could play a role. Finally, hospital systems in rural areas, where telemedicine is predominantly used, may lack the infrastructure and ancillary support required to expedite the evaluation process. These limitations are not insurmountable, and it is conceivable that in the future, as the healthcare system as a whole gains experience with the telemedicine technology, the rapidity of the encounters will improve and eventually the gap in DTN time will be filled.

The rate of sICH and the outcome measures were found to be similar between the two modalities of evaluation. This is in line with the prior meta-analysis. It has to be remarked that the timeframe of functional outcome was heterogeneous among the studies. Intuitively, safety and outcomes of thrombolytics are influenced by the system of care rather than the modality of initial evaluation, barring when a non-neurology specialist is involved in the decision making process, which was not the case in the studies that entered our meta-analysis. Here, several variables play a more crucial role than the telemedicine technology. The hemorrhagic risk, in the absence of absolute contraindications to the administration of thrombolytics (which is established beforehand), is dependable on the bedside management of post-thrombolytic patients, influenced by bedside providers and nursing staff. Similarly, the functional outcome is dependent on the thrombolytic itself and the broader system of care. In many instances, patients who received thrombolytics via telemedicine are transferred to a center with on-site specialists. Hence, a true unconfounded comparison on safety and outcomes between the two modalities that are used for the urgent assessment of the patient in the emergency department is impracticable.

In summary, apart from the longer time of patients’ evaluation, this meta-analysis found no differences in safety or outcome between telemedicine-administered thrombolytics and in-person evaluation. This work supports the use of telemedicine in acute stroke patients and its continuous expansion, especially in underserved areas, to allow small and rural centers to maintain stroke care in line with centers with on-site neurological expertise.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the included studies are all retrospective in nature with the inherent biases related to a pooled analysis of this study design. Secondly, the timeframe of the studies span for over a decade. Arguably, the improvement of technology throughout the years may have rendered old studies outdated. Additionally, the timeframe of short-term outcome varied from hospital discharge to 90 days. We tried to mitigate this heterogeneity in outcome by applying a random effect model to the MH method. This meta-analysis was not prospectively registered on PROSPERO, which may affect protocol transparency; we acknowledge this as a methodological limitation. Additionally, the exclusion of Scopus may have limited the breadth of literature coverage, though major databases with substantial overlap were comprehensively searched. Finally, the main bulk of literature of telemedicine group comes from the United States and Western Europe, hence the results of this meta-analysis may not be completely generalizable to different healthcare settings and populations.

In conclusion, the available literature suggests that telemedicine evaluation is associated with longer DTN compared to in-person evaluation. This difference in stroke metric does not affect safety or outcome. Further studies are needed to understand the underlying factors of the longer DTN time and try to address this gap.

| 1. | Sood S, Mbarika V, Jugoo S, Dookhy R, Doarn CR, Prakash N, Merrell RC. What is telemedicine? A collection of 104 peer-reviewed perspectives and theoretical underpinnings. Telemed J E Health. 2007;13:573-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 337] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Johansson T, Mutzenbach SJ, Ladurner G. Telemedicine in acute stroke care: the TESSA model. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17:268-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mazighi M, Meseguer E, Labreuche J, Miroux P, Le Gall C, Roy P, Tubach F, Amarenco P. TRUST-tPA trial: Telemedicine for remote collaboration with urgentists for stroke-tPA treatment. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23:174-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Adcock AK, Choi J, Alvi M, Murray A, Seachrist E, Smith M, Findley S. Expanding Acute Stroke Care in Rural America: A Model for Statewide Success. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26:865-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Butzner M, Cuffee Y. Telehealth Interventions and Outcomes Across Rural Communities in the United States: Narrative Review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23:e29575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Loggini A, Hornik J, Henson J, Wesler J, Nelson M, Hornik A. Comparison of Telemedicine-Administered Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Ischemic Stroke by Neurology Subspecialty: A Cross-Sectional Study. Neurohospitalist. 2024;14:413-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, Biller J, Brown M, Demaerschalk BM, Hoh B, Jauch EC, Kidwell CS, Leslie-Mazwi TM, Ovbiagele B, Scott PA, Sheth KN, Southerland AM, Summers DV, Tirschwell DL. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50:e344-e418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1907] [Cited by in RCA: 4847] [Article Influence: 692.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581-1587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8192] [Cited by in RCA: 8207] [Article Influence: 264.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, Dávalos A, Guidetti D, Larrue V, Lees KR, Medeghri Z, Machnig T, Schneider D, von Kummer R, Wahlgren N, Toni D; ECASS Investigators. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317-1329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4614] [Cited by in RCA: 4949] [Article Influence: 274.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Mohamed A, Elsherif S, Legere B, Fatima N, Shuaib A, Saqqur M. Is telestroke more effective than conventional treatment for acute ischemic stroke? A systematic review and meta-analysis of patient outcomes and thrombolysis rates. Int J Stroke. 2024;19:280-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Baratloo A, Rahimpour L, Abushouk AI, Safari S, Lee CW, Abdalvand A. Effects of Telestroke on Thrombolysis Times and Outcomes: A Meta-analysis. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22:472-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ital J Public Health. 2009;6. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 52244] [Article Influence: 10448.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8858] [Cited by in RCA: 13669] [Article Influence: 854.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Cai S, Zhou J, Pan J. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from order statistics and sample size in meta-analysis. Stat Methods Med Res. 2021;30:2701-2719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cochrane Training. Review Manager (RevMan). Cochrane Collaboration. 2014. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/online-learning/core-software. |

| 17. | Chowdhury M, Birns J, Rudd A, Bhalla A. Telemedicine versus face-to-face evaluation in the delivery of thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke: a single centre experience. Postgrad Med J. 2012;88:134-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Loggini A, Hornik J, Henson J, Wesler J, Nelson M, Hornik A. Target door-to-needle time in acute stroke treatment via telemedicine versus in-person evaluation in a rural setting of the Midwest: a retrospective cohort study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2025;34:108141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Raulot L, Mione G, Hoffmann C, Bracard S, Braun M, Brunner A, Vezain A, Langard S, Lesage F, Durupt L, Richard S. Intravenous thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke via telemedicine compared with bedside treatment in an experienced stroke unit. Eur Res Telemed. 2015;4:119-125. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhang LL, Guo YJ, Lin YP, Hu RZ, Yu JP, Yang J, Wang X. Stroke Care in the First Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu Medical College during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Eur Neurol. 2020;83:630-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nardetto L, Dario C, Tonello S, Brunelli MC, Lisiero M, Carraro MG, Saccavini C, Scannapieco G, Giometto B. A one-to-one telestroke network: the first Italian study of a web-based telemedicine system for thrombolysis delivery and patient monitoring. Neurol Sci. 2016;37:725-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lin CH, Lee KW, Chen TC, Lin JH, Liaw KR, Hsiao PJ, Tsai WY, Sun MC. Quality and safety of Telemedicine in acute ischemic stroke: Early experience in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2022;121:314-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ho W, Fawcett AP. Outcomes in patients with acute stroke treated at a comprehensive stroke center using telemedicine versus in-person assessments. J Telemed Telecare. 2024;30:1487-1492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Asaithambi G, Castle AL, Sperl MA, Ravichandran J, Gupta A, Ho BM, Hanson SK. The Door to Needle Time Metric Can Be Achieved via Telestroke. Neurohospitalist. 2017;7:188-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Riegler C, Behrens JR, Gorski C, Angermaier A, Kinze S, Ganeshan R, Rocco A, Kunz A, Müller TJ, Bitsch A, Grüger A, Weber JE, Siebert E, Bollweg K, von Rennenberg R, Audebert HJ, Nolte CH, Erdur H. Time-to-care metrics in patients with interhospital transfer for mechanical thrombectomy in north-east Germany: Primary telestroke centers in rural areas vs. primary stroke centers in a metropolitan area. Front Neurol. 2022;13:1046564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zaidi SF, Jumma MA, Urra XN, Hammer M, Massaro L, Reddy V, Jovin T, Lin R, Wechsler LR. Telestroke-guided intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator treatment achieves a similar clinical outcome as thrombolysis at a comprehensive stroke center. Stroke. 2011;42:3291-3293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sobhani F, Desai S, Madill E, Starr M, Rocha M, Molyneaux B, Jovin T, Wechsler L, Jadhav A. Remote Longitudinal Inpatient Acute Stroke Care Via Telestroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021;30:105749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/