Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.107396

Revised: April 17, 2025

Accepted: May 27, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 251 Days and 11.1 Hours

Prolonged immobility during intensive care unit (ICU) admission has been a cause of muscle atrophy and worsening functional outcomes with longer recovery times. Prior research has demonstrated that mobilization within a week of ICU admission potentially benefits physical function in critically ill patients.

To evaluate the effects of initiating mobilization within 72 hours of ICU admission in critically ill patients through an updated systematic review and meta-analysis.

A systematic search was performed through MEDLINE, Scopus, and Cochrane Library from inception until September 2024 for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing early mobilization (EM) with usual or conventional care in critically ill adult patients. Primary outcomes included length of ICU (days) and ventilation duration (days). Secondary outcomes included muscle strength, functional status, adverse events, all-cause mortality, and quality of life (QOL). A random effects meta-analysis was performed for pooled effect estimates and to derive risk ratios (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Out of 3487 results, 16 RCTs were included with a population of 2385 patients (1195 receiving EM and 1190 with usual care.) A significant reduction in the length of ICU stays [mean difference (MD) = -1.02, 95%CI: -1.96 to -0.09; P = 0.03; I2 = 60%] and ventilation duration (MD = -1.07, 95%CI: -1.91 to -0.23, P = 0.01; I2 = 57%) was observed in the EM group compared to usual care. EM significantly improved muscle strength [standard MD (SMD) = 0.47, 95%CI: 0.18-0.75, P = 0.001; I2 = 79%] and functional status (SMD = 0.70, 95%CI: 0.40-1.00, P < 0.00001; I2 = 81%) in ICU patients. No statistically significant difference was observed in adverse events (RR = 1.72, 95%CI: 1.01-2.94, P = 0.05; I2 = 31%), all-cause mortality (RR = 1.10, 95%CI: 0.79-1.53, P = 0.57; I2 = 30%), and QOL (SMD = 0.04, 95%CI: -0.07-0.15, P = 0.50; I2 = 9%) between the two groups.

Initiating mobilization within 72 hours of ICU admission is associated with improved functional outcomes and reduced ICU length of stay and ventilation duration. These findings indicate that EM may be a safe option for ICU patients, contributing to lower recovery times and healthcare costs. Further extensive research is required to validate the long-term effects on survival and QOL.

Core Tip: This updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials involving 2385 intensive care unit (ICU) patients demonstrates that initiating early mobilization (EM) (within 72 hours of ICU admission) significantly reduces ICU length of stay and mechanical ventilation duration while improving muscle strength and functional status. EM does not increase adverse events or mortality, supporting its safety and efficacy as a routine ICU intervention.

- Citation: Khan SA, Moeed A, Mari T, Yousuf Z, Hanson A, Dong Y, Cornelius P, Anjum H, Ratnani I, Surani S. Safety and early mobilization in intensive care unit patients: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(4): 107396

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i4/107396.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.107396

Mechanically ventilated (MV) patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) often experience prolonged immobility, which can lead to severe complications such as ICU-acquired weakness (ICU-AW), muscle atrophy, and delirium[1,2]. Notably, more than 50% of ICU-AW cases are attributed to MV, significantly impacting patient recovery, and increasing healthcare burdens. ICU-AW is associated with extended hospitalization, delayed rehabilitation, and long-term functional impairment, ultimately reducing the quality of life (QOL) after discharge[2].

Current ICU rehabilitation protocols typically initiate mobilization approximately one week after admission to improve patient outcomes and reduce ICU stays[3]. However, studies indicate that 25%–65% of patients requiring MV for 5–7 days develop ICU-AW, suggesting that delayed mobilization may not be the most effective approach[2]. Emerging research highlights the potential benefits of early mobilization (EM), defined as initiating physical movement within 72 hours of ICU admission, in enhancing mobility, preserving functional status, and shortening hospital stays. EM is usually facilitated by occupational and physical therapists within 3–4 days of admission[4]. However, for sedated MV patients, active mobilization remains challenging and is often limited to passive interventions such as neuromuscular stimulation, passive range of motion exercises, and frequent position changes performed by nurses or physiotherapists[2]. While some studies support EM within the first 72 hours, the optimal timing and methodology for its implementation remain uncertain due to a lack of standardized guidelines[3].

Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have evaluated the effectiveness of EM in ICU patients. A clinical trial conducted at Toho University Omori Medical Center in Tokyo demonstrated that EM using mobile patient lifts significantly improved standing ability and physical function at discharge for patients on MV for more than 48 hours[4]. Similarly, a study at the National Taiwan University Hospital found that EM in patients with traumatic brain injury led to improved mobility scores, a reduction in MV duration by approximately 6.7 days, and earlier discharge rates[5]. Research from the Hospital of Chongqing Medical University also supports high-intensity EM, incorporating position changes, bed mobility exercises, and balance training, as beneficial for improving muscle strength, and mobility, and reducing the incidence of ICU-AW and delirium in patients on MV for more than 24 hours[2]. However, conflicting results exist, with some studies reporting no significant differences in patient outcomes between EM and standard mobilization protocols[6]. While evidence increasingly favors EM in critically ill patients, further research is required to establish the most effective timing, intensity, and methodology for its implementation.

This meta-analysis builds upon the prior work by Matsuoka et al[3] by incorporating recent large-scale RCTs and assessing additional safety and effectiveness outcomes in patients who began mobilization within 72 hours of ICU admission. To the best of our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive meta-analysis on this topic to date, providing robust evidence to guide the integration of EM into ICU protocols for MV patients.

This study is an updated systematic review and meta-analysis (SRMA) of a previous systematic review[3]. The objectives and methodology of this meta-analysis were predefined in a protocol following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocol 2009 guidelines[7]. The protocol was registered at PROSPERO on September 8, 2024, under CRD42024584286.

The scope of this meta-analysis was defined using the Patient, Intervention, Control, and Outcomes protocol. We focused on critically ill adult (≥ 18 years) male or female patients admitted to the ICU due to various acute and life-threatening conditions. The intervention being investigated was early mobility/rehabilitation, defined as starting physical movement or exercises within 72 hours of ICU admission or earlier than that conducted in the control group. This was compared to the control group which received usual or conventional care performed by physiotherapists, including sedation, hemodynamic support, mechanical ventilation, position changes, passive range of motion, and physiotherapy.

The primary outcomes assessed were length of ICU stay (total number of days the patients spent in the ICU) and ventilation duration (total number of days the patients required mechanical ventilation.) The secondary outcomes evaluated were muscle strength, functional status, adverse events, all-cause mortality, and QOL. We assessed muscle strength using the Medical Research Council (MRC) scores and grip strength, prioritizing the MRC when extracting data if both were measured. Functional status was evaluated using the ICU Mobility Scale (IMS), Functional Status Score ICU (FSS-ICU), and Barthel Index (a functional independence metric), prioritizing IMS followed by the Barthel Index if all were measured when extracting data. We evaluated muscle strength and functional status at ICU discharge, or hospital discharge if these factors were not assessed at ICU discharge. All adverse events found throughout each trial period were included in the category of adverse events. Mortality was measured 28-30 days after discharge. The Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey (SF-36) and EuroQol five-dimension questionnaire (EQ-5D) were used to assess QOL. QOL was measured approximately 6 months after hospital discharge. However, measures recorded closest to the 6-month point post-discharge were used in situations where results at the 6-month mark were not available.

RCTs published in peer-reviewed journals were included to achieve adequate sample size and robust conclusions. Non-RCTs, Cohorts, reviews, letters, case reports and series, and studies using only neuromuscular electrical stimulation or ergometers were excluded. Studies were excluded if the distinction between intervention and control groups was based on the intensity or frequency of rehabilitation (even if early rehabilitation was implemented), if both groups received early mobility, or if the study lacked relevant outcomes of interest. Additionally, we also excluded literature in languages other than English and Japanese and with animal subjects.

Our SRMA were performed via a comprehensive search through PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library from inception till September 2024 for all types of studies comparing EM and usual care for critically ill patients admitted in the ICU. The search strategy was not restricted by date of publication, ethnicity, or study design. No filters were applied. We used the following MeSH terms and keywords: “Early mobilization”, “early mobility”, “intensive care unit” and “critical care unit”. The detailed search strategy used for various databases is given in Supplementary Table 1.

The selection of relevant studies was conducted in a stepwise manner. First, the retrieved datasets were imported into the EndNote Reference library (Version X7.5; Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) and duplicates were resolved. Two independent investigators (Tahreem Mari and Abdul Moeed) conducted the selection process by screening keywords, titles, and abstracts of the references. A full-text review was conducted by the same authors to determine the relevance of the studies. After this, a third reviewer (Syed A Khan) was sought to resolve any discrepancies via consensus. To ensure maximum inclusivity, the reference lists of included articles were manually examined to identify relevant studies.

Two independent authors (Tahreem Mari and Abdul Moeed) extracted and verified study and baseline characteristics from texts, figures, and tables of the included articles onto Microsoft Excel (Office 365, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, United States) with a third author (Syed A Khan) being consulted for conflict resolution. Extracted data was organized according to author name, year of publication, study design, population type and size, intervention (early mobility), control (usual care), outcomes of each study, follow-up duration, general patient characteristics (age, gender, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, body mass index, and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score). Additionally, data was interconverted to standard units wherever applicable.

The Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool 2.0 (ROB 2.0) was used to evaluate the methodology quality of the included RCTs, according to which the following data was extracted and analyzed based on the following domains: Randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, selection of the reported result.

Meta-analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan version 5.4.1; Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020) under the “Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions”[8] and the PRISMA statement using a random-effects model. Risk ratios (RR) along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were derived for dichotomous outcomes using the Mantel-Haenszel test. For continuous variables, the mean difference (MD) was determined when integrating the same parameters, whereas the standard MD (SMD) was used when integrating different parameters using the inverse variance test. The findings were visualized via forest plots. A P-value lower than 0.05 was considered significant. Heterogeneity across the pooled studies was assessed using the Higgins I2 statistics. A value of I2 = 25 % to 50% was considered as mild, I2 = 50% to 75% as moderate, and I2 > 75% as significant heterogeneity. Studies with high heterogeneity were subjected to sensitivity analysis to observe the difference in the significance of the outcomes. Publication bias was assessed through visual inspection of funnel plots. These plots were generated to evaluate the symmetry of the distribution of effect sizes across studies. A symmetrical funnel plot suggests the absence of publication bias, while asymmetry may indicate that smaller or less significant studies are underrepresented.

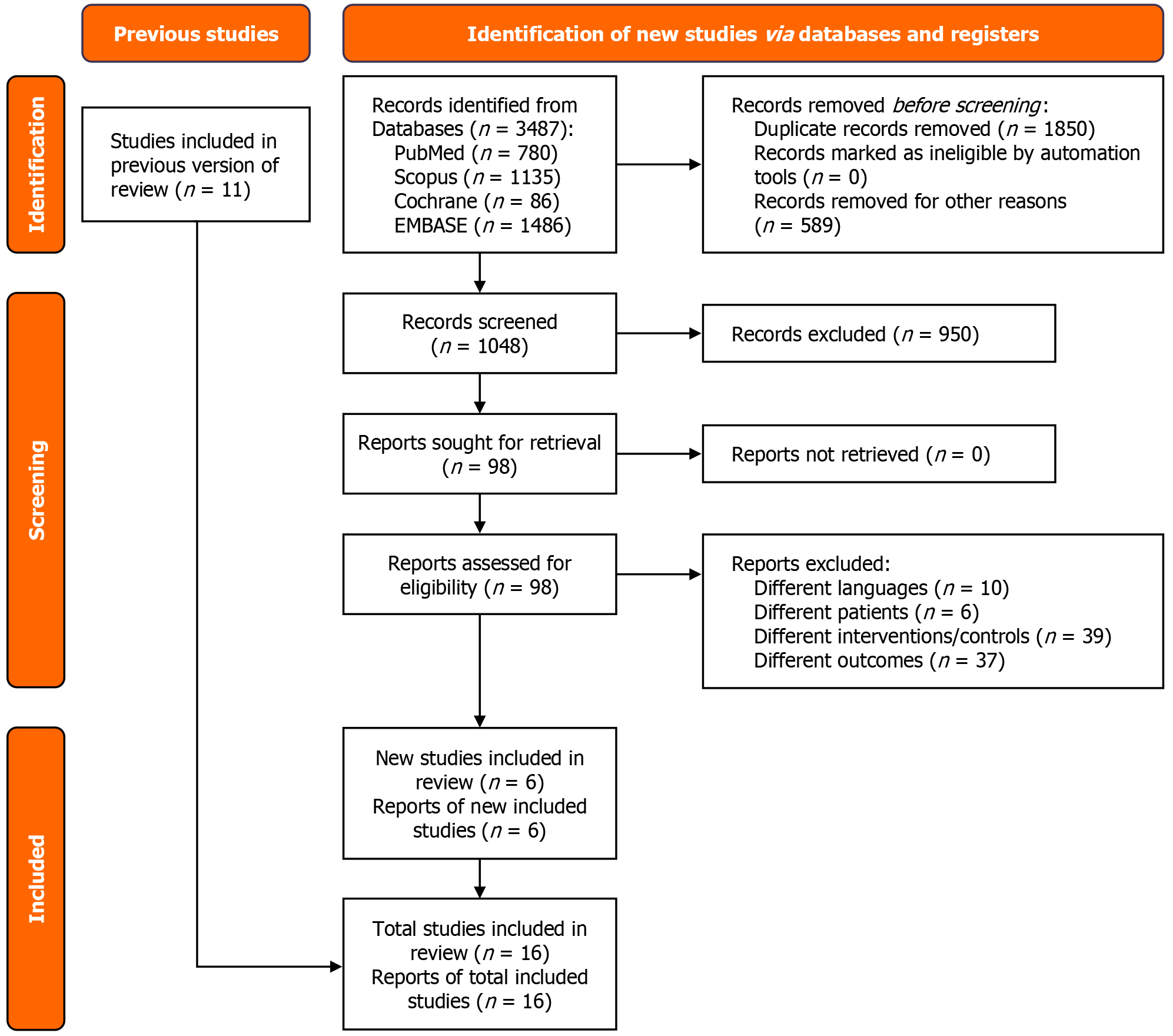

A total of 3487 studies were retrieved from the four databases. After eliminating duplicates and assessing each study for eligibility, 16 RCTs were selected for inclusion[1,2,4,6,9-20]. A detailed summary of the study selection process and the literature search methodology is provided in the PRISMA flowchart, as shown in Figure 1. Of those assessed in the previous SRMA[3], 10 RCTs were relevant to our study[6,12-20]. Six RCTs were newly included in our meta-analysis[1,2,4,9-11]. The included RCTs were published between 2009 and 2024. The patient cohort sizes across the studies displayed variation, ranging from 20 patients in both the intervention and comparison groups to larger trials involving 370 patients in each group. The sizes of the RCTs exhibited diversity. The meta-analysis was conducted on a combined sample of 2385 patients, with 1195 undergoing EM and 1190 receiving usual care. A comprehensive summary of the baseline characteristics for the included studies has been given in Table 1.

| Ref. | Study design | Time period | Intervention | Control | Total sample size (n) | Intervention (n) | Control (n) | Follow-up time (months) |

| Suzuki et al[4] | RCT | August 2021-March 2023 | Mobile patient lift | Usual care | 80 | 39 | 41 | 4 |

| Soto et al[1] | RCT | January 2018-July 2019 | Start to move protocol | Usual care | 69 | 33 | 36 | 1 |

| Zhang et al[2] | RCT | November 2020-February 2023 | EM | Usual care | 132 | 66 | 66 | 3 |

| Lin et al[9] | RCT | March 2021-October 2021 | EGDM | Usual care | 77 | 39 | 38 | 3 |

| de Paula et al[10] | RCT | October 2019-March 2021 | EM | Usual care | 85 | 40 | 45 | 30 days after hospital discharge |

| Hodgson et al[11] | RCT | Februarly 2018-November 2021 | EM | Usual care | 741 | 371 | 370 | 6 |

| Patel et al[12] | RCT | August 2011- October 2019 | EM | Usual care | 198 | 99 | 99 | 12 |

| Zhou et al[13] | RCT | September 2020-May 2021 | EM | Usual care | 100 | 50 | 50 | Till ICU discharge |

| ECMO-PT study investigators[14] | RCT | February 2018-May 2019 | EGDM | Usual care | 20 | 10 | 10 | 3 |

| Schujmann et al[15] | RCT | February 2017-February 2018 | Early progressive mobility program | Usual care | 135 | 68 | 67 | 3 |

| Hodgson et al[6] | RCT | September 2013-October 2014 | EGDM | Usual care | 50 | 29 | 21 | 6 |

| Schaller et al[16] | RCT | July 2011-November 2015 | EGDM | Usual care | 200 | 104 | 96 | 3 |

| Morris et al[17] | RCT | October 2009-November 2014 | EM | Usual care | 300 | 150 | 150 | 6 |

| Kayambu et al[18] | RCT | December 2010-August 2012 | EGDM | Usual care | 50 | 26 | 24 | 6 |

| Brummel et al[19] | RCT | February 2011-April 2012 | EM | Usual care | 44 | 22 | 22 | 3 |

| Schweickert et al[20] | RCT | June 2005-October 2007 | EM | Usual care | 104 | 49 | 55 | 6 |

The estimated average age of participants across the studies in both groups was 55.8 years, with an overall mean follow-up time of 4.38 months. Males constituted 58% of the patient population. Based on the available data, the average body mass index of the patients was 26.74 kg/m² with an average Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score of 20. Patient characteristics for the included studies have been given in Table 2.

| Ref. | Overall mean age (years) | Males | BMI (kg/m²) | APACHE II score | Type 2/type 1 diabetes | Sepsis | ||||||

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | |

| Suzuki et al[4] | 68.9 ± 13.0 | 67.1 ± 12.2 | 18 (46.2) | 30 (73.2) | 22.3 ± 7.1 | 22.8 ± 4.8 | 19.5 ± 7.2 | 19.1 ± 7.2 | 9 (23.1) | 11 (26.8) | ||

| Soto et al[1] | 60 ± 11.5 | 59.1 ± 12.5 | 8 (24.24) | 12 (33.33) | 22.0 ± 2.12 | 20.0 ± 3.06 | ||||||

| Zhang et al[2] | 60.5 ± 16.9 | 60.3 ± 18.7 | 37 (56.1) | 47 (71.2) | 22.5 ± 3.0 | 21.7 ± 2.4 | 22.4 ± 6.8 | 21.7 ± 6.8 | 24 (36.4) | 12 (18.2) | 20 (30.3) | 13 (19.7) |

| Lin et al[9] | 53.44 ± 12.06 | 52.32 ± 13.86 | 31 (79.5) | 28 (73.7) | 24.82 ± 3.73 | 24.83 ± 3.94 | 8 (20.5) | 7 (18.4) | ||||

| de Paula et al[10] | 57.3 ± 9.2 | 65.7 ± 6.0 | 21 (52.5) | 21 (46.7) | 24.8 ± 4.97 | 24.8 ± 3.18 | 11 (27.5) | 14 (31.1) | ||||

| Hodgson et al[11] | 60.5 ± 14.8 | 59.5 ± 15.2 | 243 (65.5) | 224 (60.5) | 29.9 ± 7.9 | 30.4 ± 7.8 | 18.2 ± 6.8 | 18 ± 6.9 | 87 (23.5) | 72 (19.5) | 246 (66.3) | 245 (66.2) |

| Patel et al[12] | 57.9 ± 8.5 | 54.5 ± 8.0 | 58 (58.5) | 55 (55.55) | 28.2 ± 4.68 | 29.8 ± 5.46 | 23.0 ± 3.06 | 23.0 ± 4.08 | 23 (23.2) | 26 (26.3) | 63 (63.6) | 56 (56.6) |

| Zhou et al[13] | 57.0 ± 15.3 | 57.3 ± 13.7 | 26 (52) | 30 (60) | 24.3 ± 3.6 | 23.9 ± 4.0 | 13.9 ± 5.1 | 14.0 ± 6.3 | 10 (20) | 6 (12) | ||

| ECMO-PT study investigators[14] | 49.3 ± 13.4 | 50.6 ± 17.1 | 8 (80) | 8 (80) | 24.4 ± 5.9 | 19.4 ± 4.8 | ||||||

| Schujmann et al[15] | 48 ± 15 | 55 ± 12 | 41 (60.2) | 44 (65.67) | 28 (56) | 21 (42) | ||||||

| Hodgson et al[6] | 64 ± 12 | 53 ± 15 | 21 (72.4) | 9 (42.85) | 19.8 ± 9.8 | 15.9 ± 6.9 | 19 (65) | 14 (66) | ||||

| Schaller et al[16] | 66.0 ± 9.8 | 64.0 ± 11.3 | 65 (63) | 61 (64) | 16.67 ± 7.41 | 16.67 ± 8.15 | 12 (12) | 16 (17) | 1 (1) | 0 | ||

| Morris et al[17] | 55 ± 17 | 58 ± 14 | 66 (44.0) | 68 (45.3) | 76 ± 26 | 75 ± 27 | ||||||

| Kayambu et al[18] | 62.5 ± 16.2 | 65.5 ± 18.6 | 18 (36) | 14 (28) | 27.9 ± 9.45 | 28.1 ± 5.57 | 28.0 ± 7.6 | 27.0 ± 6.8 | 1 (3.8) | 1 (4.2) | ||

| Brummel et al[19] | 62 ± 6.2 | 60 ± 5.7 | 13 (59) | 8 (36.36) | 23.43 ± 6.52 | 25.83 ± 7.20 | ||||||

| Schweickert et al[20] | 57.7 ± 11.0 | 54.4 ± 7.4 | 20 (40.8) | 32 (58.18) | 27.4 ± 2.89 | 28.0 ± 3.39 | 19.93 ± 5.53 | 18.97 ± 4.99 | 18 (37) | 18 (33) | 42 (86) | 45 (82) |

In the included studies, all RCTs demonstrated a low risk of bias. A detailed summary is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

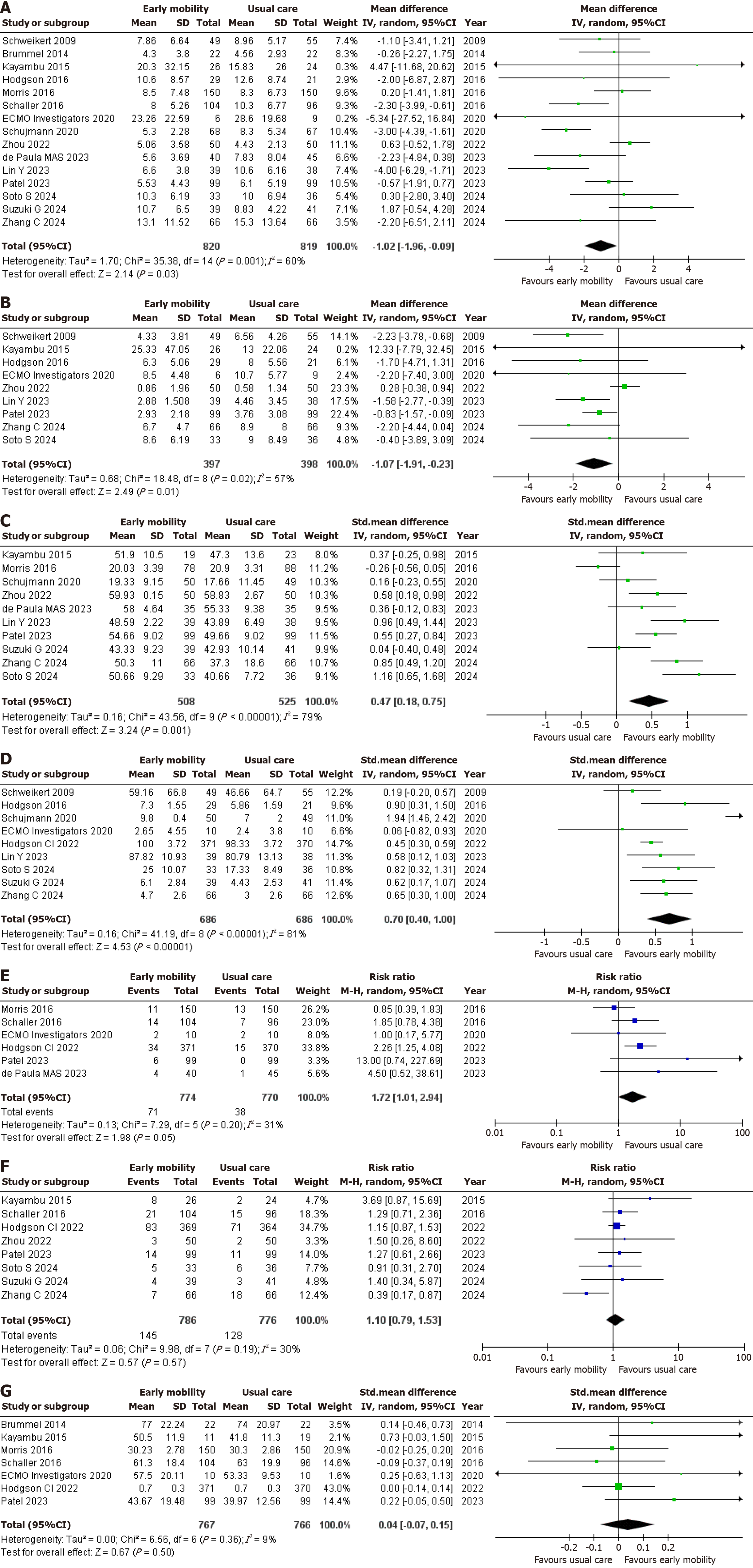

In evaluating the primary outcome of length of ICU stay (days), data from 15 studies[1,2,4,6,9,10,12-20] encompassing a total of 1639 patients were analyzed. Among these, 820 patients received EM, while 819 were treated with usual care. The random effects analysis indicated a statistically significant reduction in the length of ICU stay for the EM group compared to the usual care group (MD = -1.02, 95%CI: -1.96 to -0.09; P = 0.03; I2 = 60%) (Figure 2A). There was a hint of publication bias represented by the asymmetry of the funnel plot (Supplementary Figure 2).

For the assessment of ventilation duration (days), nine studies[1,2,6,9,12-14,18,20] involving 795 patients were reviewed. Of these, 397 patients received EM and 398 were treated with usual care. The random effects analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in ventilation duration between the two groups with the EM group requiring MV for a lesser number of days as compared to the usual care group (MD = -1.07, 95%CI: -1.91 to -0.23, P = 0.01; I2 = 57%) (Figure 2B).

10 RCTs[1,2,4,9,10,12,13,15,17,18] evaluated the effect of EM on muscle strength. Three studies measured grip strength[9,15,17] and seven reported MRC scores[1,2,4,10,12,13,18]. A total of 1033 patients were reviewed, 508 belonging to the EM group and 525 in the usual care group, The random effects meta-analysis showed that EM significantly increased muscle strength (SMD = 0.47, 95%CI: 0.18-0.75, P = 0.001; I2 = 79%) (Figure 2C). There was a hint of publication bias represented by the asymmetry of the funnel plot (Supplementary Figure 3).

An analysis of functional status was conducted across nine studies[1,2,4,6,9,11,14,15,20], with a total of 1372 patients (686 belonging to each group.) Five RCTs[2,4,6,14,15] reported IMS, three[9,11,20] measured Barthel Index and one RCT[1] reported FSS-ICU. The random effects analysis showed a significant statistical difference in functional status between EM and usual care suggesting that EM potentially improves functional status in ICU patients (SMD = 0.70, 95%CI: 0.40-1.00, P < 0.00001; I2 = 81%) (Figure 2D).

The secondary outcome of adverse events was examined through six studies[10-12,14,16,17] involving 1544 patients. Of these, 774 patients received EM, while 770 were treated with usual care. The random effects analysis demonstrated no statistically significant difference in adverse events between the two groups, indicating that EM doesn’t increase the incidence of adverse events (RR = 1.72, 95%CI: 1.01-2.94, P = 0.05; I2 = 31%) (Figure 2E).

For the assessment of all-cause mortality, eight studies[1,2,4,11-13,16,18] involving 1562 patients were reviewed. Of these, 786 patients received EM and 776 were treated with usual care. The random effects analysis revealed no statistically significant difference in mortality rates between the two groups (RR = 1.10, 95%CI: 0.79-1.53, P = 0.57; I2 = 30%) (Figure 2F).

Seven RCTs[11,12,14,16-19] evaluated the effects of EM on QOL. A total of 1533 patients were analyzed, with 767 receiving EM while 766 were treated with usual care. To measure QOL, four studies used the SF-36[12,16-18], two used the EQ-5D-5 L scale[11,14], and one used the EQ-5D visual analog scale[19]. The random effects analysis revealed no statistically significant difference in QOL between the two groups (SMD = 0.04, 95%CI: -0.07 to 0.15, P = 0.50; I2 = 9%) (Figure 2G).

For the outcomes of adverse events and all-cause mortality, an I2 value of 31% and 30% respectively indicated little heterogeneity between the studies, suggesting minimal variability and thereby eliminating the need for a sensitivity analysis. Moreover, an I2 value of 9%; for the outcome of QOL, also exhibited little heterogeneity among studies, which precluded the need for sensitivity analysis as well. This low level of variability meant that the differences observed in the studies were not substantial enough to warrant further investigation into their impact on the overall results.

A sensitivity analysis was performed to address the outcome of length of ICU stay, given the high heterogeneity indicated by an I2 value of 60%. This analysis involved identifying and excluding studies with low-quality assessment scores or notable demographic differences, as well as certain patient groups from both treatment groups. Excluding the study by Schujmann et al[15] led to a reduction in heterogeneity for the length of ICU stay, with the I2 value decreasing from 60% to 48% (Supplementary Figure 4). For the outcome of ventilation duration, removal of the study by Zhou et al[13] led to a significant reduction in heterogeneity from 57% to 0% (Supplementary Figure 5). Similarly, for the outcome of functional status, the removal of the study by Schujmann et al[15] led to a reduction in heterogeneity from 81% to 17% (Supplementary Figure 6.) The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis did not result in a decrease in heterogeneity for the outcome of muscle strength.

This updated SRMA, which includes 16 RCTs and over 2380 patients, provides the most comprehensive evidence to date on the efficacy and safety of EM in ICU patients. By incorporating six recently published RCTs that were not included in previous meta-analyses[1,2,4,9-11], this study strengthens the existing literature on EM by demonstrating its significant association with shorter ICU length of stay and reduced MV duration. Additionally, secondary outcomes such as functional status and muscle strength showed notable improvements, underscoring EM's role in preventing ICU-AW. Importantly, no significant differences were observed in adverse events, all-cause mortality, or QOL between EM and usual care, suggesting that EM does not increase the risk of complications. These findings support EM as a viable intervention for improving patient recovery while ensuring safety.

Compared to the previous SRMA by Matsuoka et al[3], which did not assess ICU length of stay or ventilation duration, our study provides greater insight into the effects of EM on overall treatment timelines. The significant reduction in ICU length of stay and MV duration aligns with findings from a large retrospective cohort study of 8609 ICU patients, which demonstrated that out-of-bed mobility was associated with shorter ventilation duration and hospital stays, with a dose-dependent relationship between increased mobility and better patient outcomes[21]. Similarly, a study by Lai et al[22] demonstrated that EM was significantly linked to shorter MV duration and ICU stay, consistent with previous clinical trials evaluating similar outcomes[23,24]. Given that prolonged ICU stays and extended MV duration are associated with worse patient outcomes, increased healthcare costs, and neuromuscular deterioration[25], these findings suggest that EM can be an effective strategy for optimizing ICU care. Additionally, Hodgson et al[6] emphasized the need for large-scale studies and estimated that a sample size of over 500 patients would be necessary to accurately differentiate the effects of EM from usual care on ICU length of stay. Our meta-analysis, which incorporates data from 1639 ICU patients, provides statistically robust insights into the impact of EM on hospitalization duration and MV dependency.

ICU survivors often experience significant muscle weakness and impaired functional capacity, which may persist for months or even years post-discharge due to ICU-AW[26,27]. Our findings indicate that EM significantly improves muscle strength, aligning with Matsuoka et al[3]. However, their meta-analysis evaluated functional status under the broader term “activities of daily living” and was limited by a small sample size of only 315 patients across three RCTs. In contrast, our updated analysis includes 1372 ICU patients, providing stronger evidence for EM’s beneficial impact on functional recovery. These findings are supported by Tipping et al[28], who reported that EM reduced ICU-AW incidence and improved muscle function at ICU discharge. Similarly, Fuke et al[29] demonstrated that early rehabilitation significantly enhanced short-term physical function in critically ill patients, findings that parallel those of Kayambu et al[30]. The observed improvements likely stem from EM counteracting the muscle wasting and neuromuscular deconditioning associated with prolonged bed rest[31]. However, a meta-analysis by Castro-Avila et al[32] did not find a significant association between EM and improved functional outcomes, likely due to heterogeneity in included studies, inconsistent intervention protocols, and the presence of early rehabilitation in control groups, which may have diluted the observed effects of EM.

Regarding safety outcomes, our findings indicate that EM does not significantly increase the incidence of adverse events or all-cause mortality, in agreement with Matsuoka et al[3] and other systematic reviews and meta-analyses[33,34]. This supports the overall safety of EM in critically ill patients; however, certain subpopulations may require additional monitoring. A study by Schaller et al[16] reported an increase in adverse events in patients receiving EM in a surgical ICU, suggesting that mobilization strategies may need to be modified for postoperative patients. Similarly, a post hoc analysis of the TEAM trial indicated that ICU patients with cardiovascular comorbidities had a higher risk of cardiopulmonary events during mobilization, emphasizing the importance of individualized risk stratification to determine the appropriate level of activity[35]. Moreover, Hodgson et al[11] and Patel et al[12] reported a higher rate of adverse events in the EM group, which the authors attributed to potential surveillance bias due to the unblinded nature of these trials. Patel et al[12] also observed a non-significant increase in mortality in the EM group, reinforcing the need for further research to explore the safest approaches for implementing EM in critically ill patients. Although some recent RCTs suggest potential risks, our overarching analysis suggests that EM can be implemented safely when appropriate precautions are taken, particularly in high-risk populations.

While the previous meta-analysis by Matsuoka et al[3] suggested that EM might improve QOL, our updated analysis found no significant difference between EM and usual care. The previous study assessed only 394 patients, whereas our analysis evaluated 1533 ICU patients, suggesting that prior conclusions may have been influenced by a limited sample size. Given the variability in QOL measurements across studies, future RCTs should incorporate standardized long-term QOL assessments to better understand the impact of EM on post-ICU life quality.

Based on the findings for both primary and secondary outcomes, this study supports the integration of EM into ICU care to improve patient recovery, reduce treatment timelines, and mitigate the adverse effects of prolonged immobility. The implementation of EM presents an effective approach to preventing ICU-AW by preserving muscle function and enhancing the ability to perform daily activities after hospital discharge. However, several aspects require further research, particularly regarding adverse events, muscle strength, ventilation duration, and ICU length of stay, as inconsistencies persist among recent RCTs and the findings of this meta-analysis. These discrepancies may arise from differences in patient populations, evaluation techniques, follow-up durations, and variations in how EM is implemented across different institutions. As more high-quality RCTs emerge, efforts should be made to establish standardized EM protocols to ensure consistent results and broad applicability across ICU settings.

There are several potential limitations to this meta-analysis that should be acknowledged. Publication bias was observed for the primary outcome of ICU length of stay and the secondary outcome of muscle strength, indicating some uncertainty in these results. These outcomes may require further evaluation as more RCTs investigate alternative ICU mobility protocols. Significant heterogeneity was noted for ICU length of stay and MV duration; however, sensitivity analyses reduced this variability by excluding Schujmann et al[15] and Zhou et al[13], which suggests that patient population differences may have influenced these findings. High heterogeneity was also observed for muscle strength, indicating variability in patient demographics and treatment implementation. Another limitation is the lack of standardized ICU mobilization protocols across different healthcare centers, which may have led to variations in treatment intensity and patient outcomes. Additionally, inconsistencies in follow-up durations across studies may have contributed to variations in reported effects, as some patients were evaluated months later than others. Moreover, the availability of specialized EM equipment, such as patient lifts, differs between institutions, which may impact the feasibility and effectiveness of EM[4].

The results of this meta-analysis point to the ability of EM to improve patient outcomes in MV ICU patients. Length of ICU stay and MV duration showed reductions in the EM groups, with muscle strength and functional status also demonstrating improvements over usual care. Moreover, these results are observed with no increase in adverse events or all-cause mortality, consistent with the previous meta-analysis. These positive effects of EM and its demonstrated safety advocate for its consideration in more ICU protocols.

| 1. | Soto S, Adasme R, Vivanco P, Figueroa P. Efficacy of the "Start to move" protocol on functionality, ICU-acquired weakness and delirium: A randomized clinical trial. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 2024;48:211-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhang C, Wang X, Mi J, Zhang Z, Luo X, Gan R, Mu S. Effects of the High-Intensity Early Mobilization on Long-Term Functional Status of Patients with Mechanical Ventilation in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care Res Pract. 2024;2024:4118896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Matsuoka A, Yoshihiro S, Shida H, Aikawa G, Fujinami Y, Kawamura Y, Nakanishi N, Shimizu M, Watanabe S, Sugimoto K, Taito S, Inoue S. Effects of Mobilization within 72 h of ICU Admission in Critically Ill Patients: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Clin Med. 2023;12:5888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Suzuki G, Kanayama H, Arai Y, Iwanami Y, Kobori T, Masuyama Y, Yamamoto S, Serizawa H, Nakamichi Y, Watanabe M, Honda M, Okuni I. Early Mobilization Using a Mobile Patient Lift in the ICU: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Crit Care Med. 2024;52:920-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yen HC, Chuang HJ, Hsiao WL, Tsai YC, Hsu PM, Chen WS, Han YY. Assessing the impact of early progressive mobilization on moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2024;28:172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hodgson CL, Bailey M, Bellomo R, Berney S, Buhr H, Denehy L, Gabbe B, Harrold M, Higgins A, Iwashyna TJ, Papworth R, Parke R, Patman S, Presneill J, Saxena M, Skinner E, Tipping C, Young P, Webb S; Trial of Early Activity and Mobilization Study Investigators. A Binational Multicenter Pilot Feasibility Randomized Controlled Trial of Early Goal-Directed Mobilization in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1145-1152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13930] [Cited by in RCA: 13826] [Article Influence: 813.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 8. | Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd Edition. Chichester (UK): John Wiley and Sons, 2019. |

| 9. | Lin Y, Liang T, Zhang X, Peng Y, Li S, Huang X, Chen L. Early goal-directed mobilization in patients with acute type A aortic dissection: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2023;37:1311-1321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | de Paula MAS, Carvalho EV, de Souza Vieira R, Bastos-Netto C, de Jesus LADS, Stohler CG, Arantes GC, Colugnati FAB, Reboredo MM, Pinheiro BV. Effect of a structured early mobilization protocol on the level of mobilization and muscle strength in critical care patients: A randomized clinical trial. Physiother Theory Pract. 2024;40:2004-2013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hodgson CL, Bailey M, Bellomo R, Brickell K, Broadley T, Buhr H, Gabbe BJ, Gould DW, Harrold M, Higgins AM, Hurford S, Iwashyna TJ, Serpa Neto A, Nichol AD, Presneill JJ, Schaller SJ, Sivasuthan J, Tipping CJ, Webb S, Young PJ; TEAM Study Investigators and the ANZICS Clinical Trials Group. Early Active Mobilization during Mechanical Ventilation in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1747-1758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 61.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Patel BK, Wolfe KS, Patel SB, Dugan KC, Esbrook CL, Pawlik AJ, Stulberg M, Kemple C, Teele M, Zeleny E, Hedeker D, Pohlman AS, Arora VM, Hall JB, Kress JP. Effect of early mobilisation on long-term cognitive impairment in critical illness in the USA: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11:563-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 45.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhou W, Yu L, Fan Y, Shi B, Wang X, Chen T, Yu H, Liu J, Wang X, Liu C, Zheng H. Effect of early mobilization combined with early nutrition on acquired weakness in critically ill patients (EMAS): A dual-center, randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0268599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | ECMO-PT Study Investigators; International ECMO Network. Early mobilisation during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was safe and feasible: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1057-1059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Schujmann DS, Teixeira Gomes T, Lunardi AC, Zoccoler Lamano M, Fragoso A, Pimentel M, Peso CN, Araujo P, Fu C. Impact of a Progressive Mobility Program on the Functional Status, Respiratory, and Muscular Systems of ICU Patients: A Randomized and Controlled Trial. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:491-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Schaller SJ, Anstey M, Blobner M, Edrich T, Grabitz SD, Gradwohl-Matis I, Heim M, Houle T, Kurth T, Latronico N, Lee J, Meyer MJ, Peponis T, Talmor D, Velmahos GC, Waak K, Walz JM, Zafonte R, Eikermann M; International Early SOMS-guided Mobilization Research Initiative. Early, goal-directed mobilisation in the surgical intensive care unit: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:1377-1388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 517] [Article Influence: 51.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Morris PE, Berry MJ, Files DC, Thompson JC, Hauser J, Flores L, Dhar S, Chmelo E, Lovato J, Case LD, Bakhru RN, Sarwal A, Parry SM, Campbell P, Mote A, Winkelman C, Hite RD, Nicklas B, Chatterjee A, Young MP. Standardized Rehabilitation and Hospital Length of Stay Among Patients With Acute Respiratory Failure: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315:2694-2702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kayambu G, Boots R, Paratz J. Early physical rehabilitation in intensive care patients with sepsis syndromes: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:865-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Brummel NE, Girard TD, Ely EW, Pandharipande PP, Morandi A, Hughes CG, Graves AJ, Shintani A, Murphy E, Work B, Pun BT, Boehm L, Gill TM, Dittus RS, Jackson JC. Feasibility and safety of early combined cognitive and physical therapy for critically ill medical and surgical patients: the Activity and Cognitive Therapy in ICU (ACT-ICU) trial. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:370-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, Nigos C, Pawlik AJ, Esbrook CL, Spears L, Miller M, Franczyk M, Deprizio D, Schmidt GA, Bowman A, Barr R, McCallister KE, Hall JB, Kress JP. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1874-1882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2077] [Cited by in RCA: 2207] [Article Influence: 129.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fazio SA, Cortés-Puch I, Stocking JC, Doroy AL, Black H, Liu A, Taylor SL, Adams JY. Early Mobility Index and Patient Outcomes: A Retrospective Study in Multiple Intensive Care Units. Am J Crit Care. 2024;33:171-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lai CC, Chou W, Chan KS, Cheng KC, Yuan KS, Chao CM, Chen CM. Early Mobilization Reduces Duration of Mechanical Ventilation and Intensive Care Unit Stay in Patients With Acute Respiratory Failure. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:931-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | McWilliams D, Weblin J, Atkins G, Bion J, Williams J, Elliott C, Whitehouse T, Snelson C. Enhancing rehabilitation of mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit: a quality improvement project. J Crit Care. 2015;30:13-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Needham DM, Korupolu R, Zanni JM, Pradhan P, Colantuoni E, Palmer JB, Brower RG, Fan E. Early physical medicine and rehabilitation for patients with acute respiratory failure: a quality improvement project. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:536-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 487] [Cited by in RCA: 510] [Article Influence: 31.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hunter A, Johnson L, Coustasse A. Reduction of intensive care unit length of stay: the case of early mobilization. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2014;33:128-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | TEAM Study Investigators; Hodgson C, Bellomo R, Berney S, Bailey M, Buhr H, Denehy L, Harrold M, Higgins A, Presneill J, Saxena M, Skinner E, Young P, Webb S. Early mobilization and recovery in mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU: a bi-national, multi-centre, prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2015;19:81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Damian MS, Wijdicks EFM. The clinical management of neuromuscular disorders in intensive care. Neuromuscul Disord. 2019;29:85-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Tipping CJ, Harrold M, Holland A, Romero L, Nisbet T, Hodgson CL. The effects of active mobilisation and rehabilitation in ICU on mortality and function: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:171-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 445] [Cited by in RCA: 426] [Article Influence: 47.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Fuke R, Hifumi T, Kondo Y, Hatakeyama J, Takei T, Yamakawa K, Inoue S, Nishida O. Early rehabilitation to prevent postintensive care syndrome in patients with critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kayambu G, Boots R, Paratz J. Physical therapy for the critically ill in the ICU: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1543-1554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 325] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Puthucheary ZA, Rawal J, McPhail M, Connolly B, Ratnayake G, Chan P, Hopkinson NS, Phadke R, Dew T, Sidhu PS, Velloso C, Seymour J, Agley CC, Selby A, Limb M, Edwards LM, Smith K, Rowlerson A, Rennie MJ, Moxham J, Harridge SD, Hart N, Montgomery HE. Acute skeletal muscle wasting in critical illness. JAMA. 2013;310:1591-1600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1118] [Cited by in RCA: 1430] [Article Influence: 110.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 32. | Castro-Avila AC, Serón P, Fan E, Gaete M, Mickan S. Effect of Early Rehabilitation during Intensive Care Unit Stay on Functional Status: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Okada Y, Unoki T, Matsuishi Y, Egawa Y, Hayashida K, Inoue S. Early versus delayed mobilization for in-hospital mortality and health-related quality of life among critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Intensive Care. 2019;7:57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Paton M, Chan S, Serpa Neto A, Tipping CJ, Stratton A, Lane R, Romero L, Broadley T, Hodgson CL. Association of active mobilisation variables with adverse events and mortality in patients requiring mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2024;12:386-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Broadley T, Serpa Neto A, Bailey M, Bellomo R, Brickell K, Buhr H, Gabbe BJ, Gould DW, Harrold M, Hurford S, Iwashyna TJ, Nichol AD, Presneill JJ, Schaller SJ, Sivasuthan J, Tipping CJ, Webb S, Young PJ, Higgins AM, Hodgson CL; TEAM Trial Investigators. Adverse events during and after early mobilisation: A post hoc analysis of the TEAM trial. Aust Crit Care. 2025;38:101156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/