Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.106485

Revised: May 5, 2025

Accepted: July 23, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 260 Days and 7.8 Hours

Managing left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO) and systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve can be challenging, especially in the context of circulatory shock and pulmonary edema post cardiac surgery.

We describe a case of an 80-year-old female patient with a history of severe aortic stenosis and hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy that underwent aortic valve replacement and myectomy. The patient presented with acute pulmonary edema and low blood pressure due to LVOTO and SAM post cardiac surgery in the intensive care unit. She was paced with an epicardial dual-chamber pacing system due to complete atrioventricular block and treated initially with nore

Vasopressin seems to be the preferred vasopressor for managing LVOTO and SAM post-cardiac surgery, because of its absence of inotropic effects. Echocardiography is crucial for early diagnosis and therapeutic management.

Core Tip: Left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction is a condition in which the LVOT is obstructed. Aortic valve stenosis and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy are the most common causes of LVOT obstruction. We report a case of severe aortic stenosis and hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy that underwent aortic valve replacement and myectomy. Management of patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy and systolic anterior motion remains a clinical challenge. Bedside echocardiogram guided therapeutic decisions has central role in such complex case patients to improve outcome. Vasopressin has been shown to reduce LVOT gradient and seems to be the vasoconstrictive drug of choice in such patients.

- Citation: Elaiopoulos D, Dimitriadis F, Tzatzaki E, Chronaki M, Kolonia K, Antonopoulos M, Konstantinou G, Kogerakis N, Dimopoulos S. Vasopressin role in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy post-cardiac surgery: A case report. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(4): 106485

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i4/106485.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.106485

Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO) and systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve (MV) are significant clinical manifestations of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM) that can lead to important hemodynamic compromise. LVOTO is characterized by the narrowing of the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) due to remarkable cardiac anatomical characteristics noticed in HOCM, such as a hypertrophied interventricular septum. Concurrently, structural abnormalities of the MV, along with altered papillary muscle positioning, may precipitate SAM, defined by the anterior movement of the MV during systole[1]. These phenomena are generally linked to HOCM but may also occur in other contexts, including post-cardiac surgery[2].

Post aortic valve replacement (AVR), dynamic LVOTO may arise from alterations in ventricular loading conditions, myocardial contractility, septal morphology, or systemic vascular resistance. Timely recognition and management of this complication is essential. These entities should be promptly suspected, as delayed or inadequate treatment may have catastrophic consequences for the patient[3]. In this article, we describe a case of an elderly female patient who ex

An 80-year-old female consulted a cardiac surgery ambulatory clinic with a history of deteriorating exertional dyspnea.

An 80-year-old female (height 168 cm; weight 72 kg) with a history of deteriorating exertional dyspnea due to severe aortic stenosis and HOCM (septum 14 mm, resting outflow gradient 70 mmHg) underwent AVR (Avalus Medtronic bioprosthesis, No. 21 mm) and septal myectomy. Perioperatively, reintroduction to cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and transfusion of blood products were necessary due to bleeding from the cannula insertion sites requiring surgical sutures, resulting in a CPB total time of 93 minutes.

The patient has a history of aortic stenosis and HOCM with regular echocardiographic follow-up.

Patient had no other personal or family history.

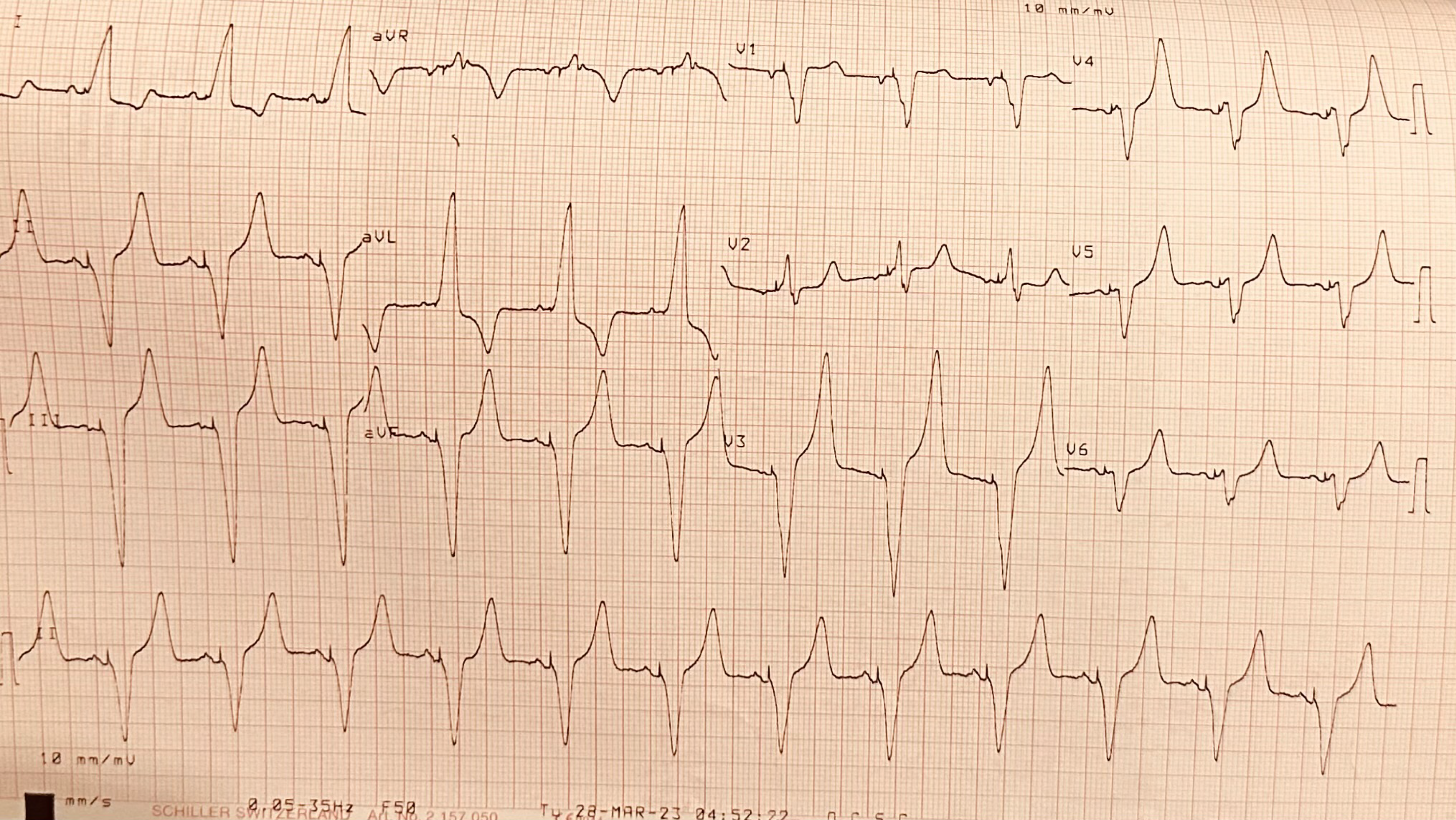

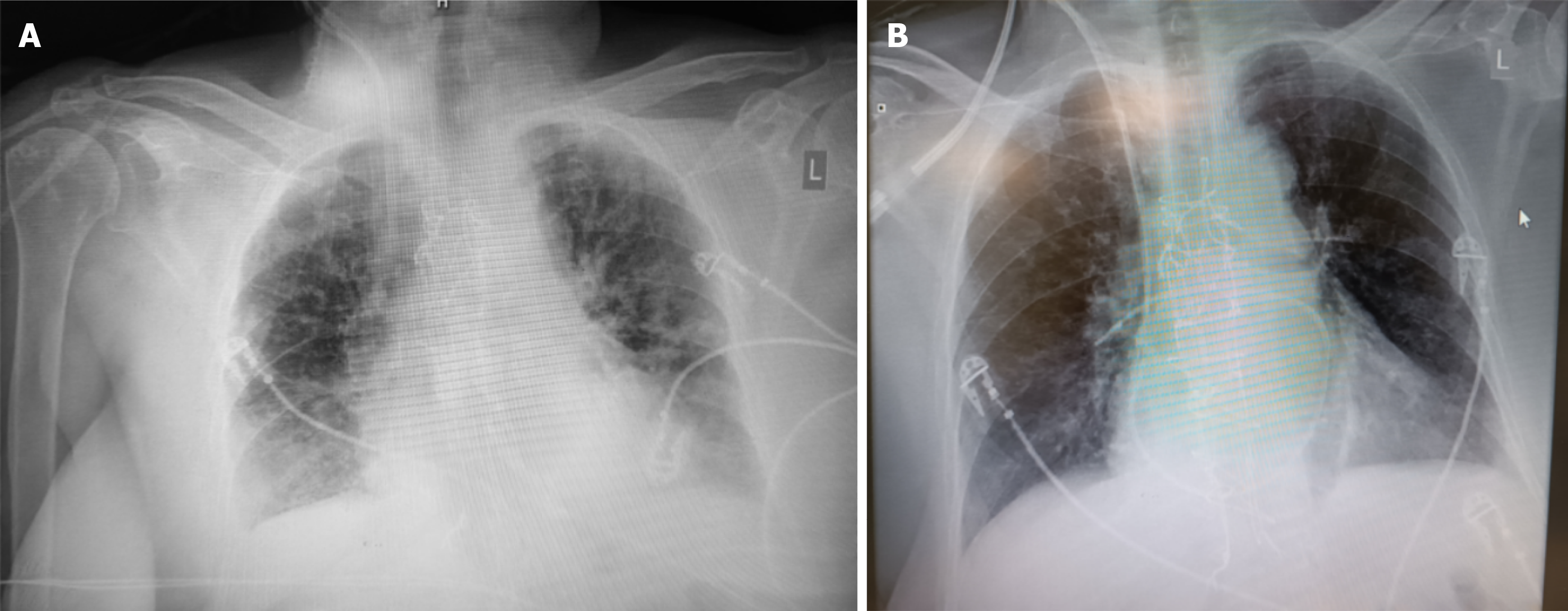

Upon admission to the ICU the patient had a norepinephrine infusion of 0.1 μg/kg/minute. MBP was 70 mmHg and UO ranged from 150 to 200 mL/hour. Atrioventricular sequential pacing was necessary due to complete atrioventricular block (Figure 1). HR and atrio-ventricular delay modifications didn’t result in significant alterations in BP or CO, and they were stabilized at 70 beats per minute and 180 milliseconds respectively. Six hours later she was successfully weaned from mechanical ventilation according to our institute’s protocol, despite a slight impairment of UO (80 mL/hour). Gradually, the patient started becoming hypoxemic, exhibiting pulmonary congestion on X-rays (Figure 2A). Intravenous furosemide was given and oliguria improved (> 150 mL/hour) but with no improvement of oxygenation and a concomitant drop of BP (systolic BP = 100 mmHg, MBP = 60 mmHg). Given the history of left ventricular hypertrophy and LVOTO, 500 mL of N/S 0.9% was initially administered, esmolol was started with titration up to 160 μg/kg/minute, and norepinephrine dosage rose at 0.18 μg/kg/minute, aiming for MBP > 65 mmHg. The interventions failed to restore hemodynamics and oxygenation, and the use of non-invasive mechanical ventilation was initiated to prevent re-intubation.

Laboratory findings were as follows: White blood cells (ADVIA 2120i, SIEMENS) = 22580 K/μL, C-reactive protein (Atellica® CH Revised C-Reactive Protein assay) = 202 mg/L, urea [Atellica® CH Urea Nitrogen (UN_c) assay] = 81 mg/dL, creatinine [Atellica® CH Enzymatic Creatinine_2 (ECre_2) assay] = 1.2 mg/dL, lactate = 3.2 mmol/L, lactate dehydrogenase (Atellica® CH Lactate Dehydrogenase L-P) = 1151 IU/L, temperature = 38.3 °C. The arterial blood gas analysis (ABL800 FLEX, RADIOMETER) revealed a pH = 7.41, PaO2 = 320 mmHg and PaO2/FiO2 > 250 mmHg, pCO2 = 39 mmHg, Ca2+ = 1.19 mmol/L and normal lactate levels (< 1.6 mmol/L). A standard four-lumen Swan-Ganz catheter (model 131F7, size 7F, length 110 cm, Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, United States) was placed at the bedside for tailored therapy. Initial measurements revealed a cardiac index of 1.7 L/minute/m2, a systemic vascular resistance index of 2115 dyn∙second∙m2/cm5, mean pulmonary artery pressure = 33 mmHg, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure = 18 mmHg and central venous pressure = 15 mmHg.

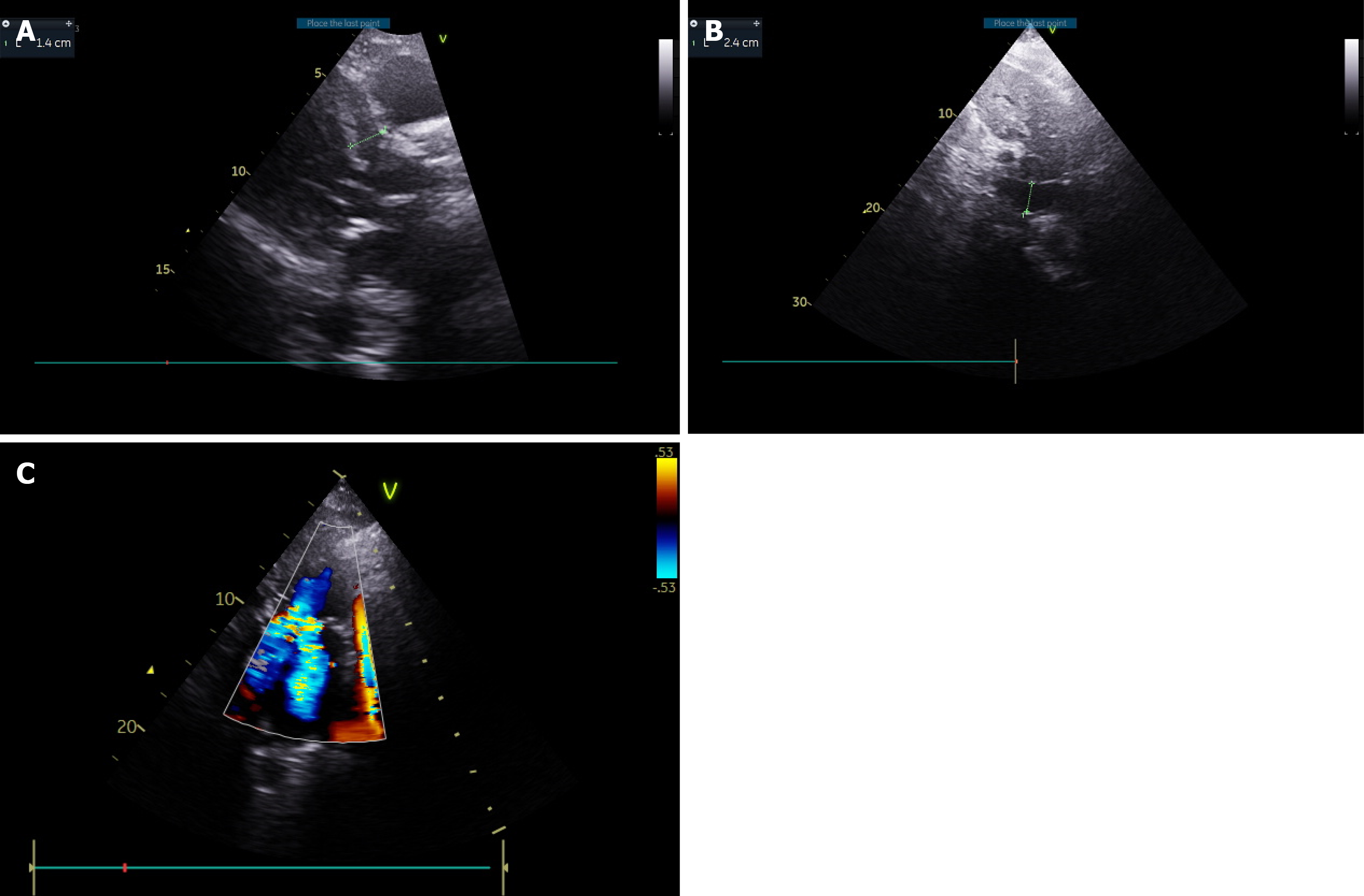

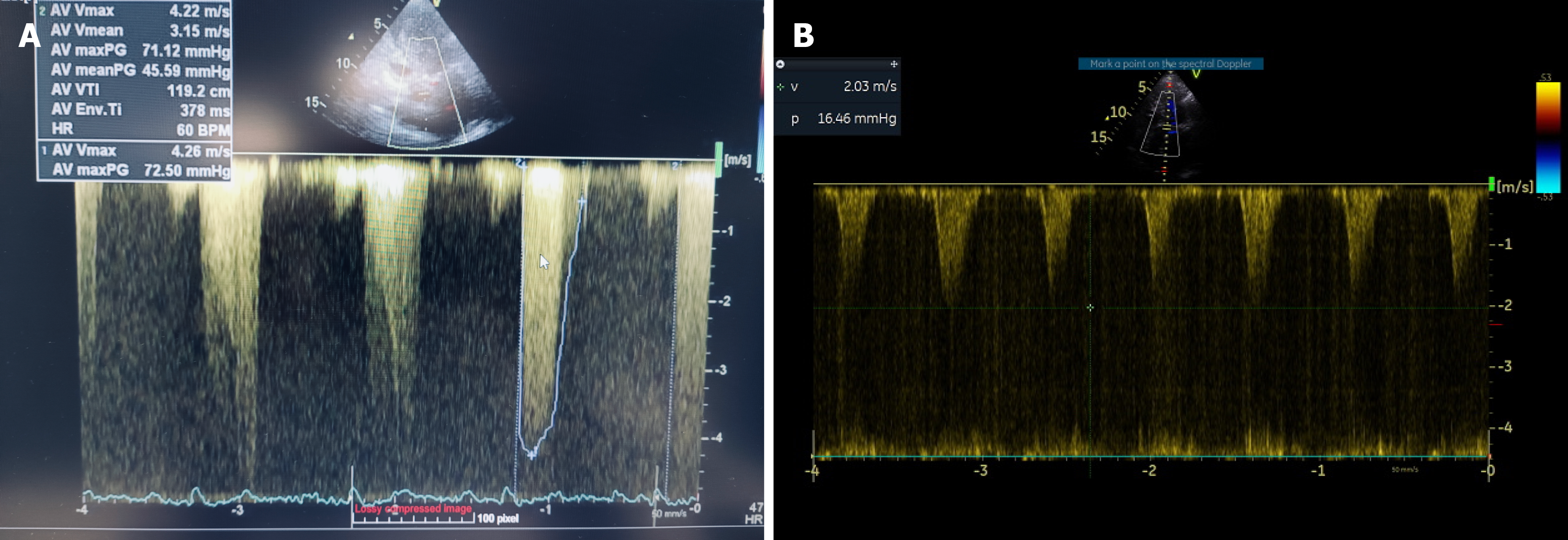

TTE revealed a hyperdynamic, hypertrophic left ventricle (LV) (Figure 3A, Video 1) SAM of the MV with severe regur

A multidisciplinary ICU team (including ICU cardiologists) discussed the case and confirmed diagnosis and treatment choice.

Finally, a hyperdynamic, hypertrophic LV (Figure 3A, Video 2) and SAM of the MV with severe regurgitation was diagnosed.

Furosemide continuous infusion was started (6 mg/hour), and norepinephrine was gradually substituted by vasopressin at an infusion rate of 0.05 U/minute.

During the following hours, the patient was stabilized, UO increased (200-300 mL/hour), the LVOT peak gradient decreased to 16 mmHg (Figure 4B) and pulmonary edema resolved (Figure 2B). Four days later he had been weaned off vasopressors, a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker was inserted due to persistent complete heart block, and the patient was transferred to the ward.

LVOTO is usually described in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, but it can occur in various clinical scenarios in the ICU, such as septic shock, apical ballooning syndrome, sigmoid septum, myocardial infarction, and post-cardiac surgery. Changes in preload, afterload, heart rhythm and rate, atrio-ventricular synchronization, inotropy, LV shape, and regional wall contractility can cause dynamic LVOTO in susceptible patients[4,5]. In our case, LVOT gradient was possibly provoked by afterload reduction, either due to CPB and subsequent systemic inflammatory response syndrome or to AVR itself[6]. In patients with aortic stenosis, surgical correction induces a dramatic decrease in afterload that may decrease the volume of an already small and hypertrophied ventricle. An abnormal LV gradient has been reported in as high as 14% of patients submitted to AVR[7].

A second mechanism could be positive inotropism due to the inotropic effect of norepinephrine and the sympathetic stimulation caused by surgery/pain[8]. Norepinephrine, although usually considered as a purely vasoconstrictive agent, has strong intrinsic inotropic properties that can provoke or augment LVOTO[9,10]. Preload reduction as a cause has to be excluded in our case, as there was a combination of significant inferior vena cava dilatation and pulmonary congestion[4]. In addition, administration of fluids failed to restore BP and worsened pulmonary congestion. There is no established guidance for fluid balance in the context of LVOTO and acute pulmonary edema, and ICU management should take into account several parameters like central venous pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, inferior vena cava diameter, B-lines, and predominantly echocardiographic follow-up of SAM and mitral regurgitation.

Complete heart block and atrioventricular dissociation are frequent complications of AVR or septal myectomy that can worsen LVOTO, but they were restored in our patient by dual-chamber atrioventricular pacing. Although asynchronous pacing of ventricles might be beneficial in LVOTO, and dual-chamber pacing may improve gradient, this wasn’t the case in our patient[11]. Beta blockade is essential in the management of LVOTO either due to HOCM or other causes[12,13]. Any tachyarrhythmia that exacerbates SAM-related obstruction should be promptly managed with ultra-short-acting beta-blockers, such as esmolol or landiolol. Long-acting agents are not recommended due to the rapidly changing hemodynamic conditions. Its use was somewhat delayed in our case due to concerns about complete heart block. Due to its very short half-life, esmolol is the preferred agent in such cases, as long as temporary pacing is available[12]. Never

Vasopressin has become very popular in the management of vasodilatory shock post cardiac surgery. Unlike norepinephrine, it lacks inotropic properties and vasoconstrictive action in the pulmonary vasculature, and its effects remain intact in hypoxic and acidotic conditions. Also known as antidiuretic hormone, it exerts its physiological effects via V1, V2, and V3 receptors. While its V2-mediated renal action promotes water reabsorption and may cause dilutional hyponatremia, its use in this context did not significantly reduce UO, likely due to preserved renal perfusion under adequate BP and CO[14].

Consequently, alpha-1 agonists such as norepinephrine, phenylephrine, and vasopressin are recommended to increase afterload, whereas vasodilators should be avoided[15]. Norepinephrine, although a potent vasoconstrictor, possesses modest beta-adrenergic activity that can enhance cardiac contractility and potentially worsen LVOTO, especially at higher doses. Phenylephrine is a pure alpha-agonist and lacks inotropic effects as well, but has pulmonary and renal vasoconstrictive properties. However, it may trigger reflex bradycardia and sudden fluctuations in hemodynamics, complicating management in frail cases[9]. These pharmacologic profiles render vasopressin as a more appropriate and safer choice in this specific clinical scenario. Indeed, vasopressin addition reduced LVOT gradient and mitral regurgitation in our patient too, reversing pulmonary edema and restoring hemodynamics[16]. Agents with nonselective arterial vasoconstrictive effects, like etilefrine, dopamine, dobutamine, and epinephrine should be avoided, as their positive inotropic and chronotropic actions through their action on beta-1 and beta-2 receptors can exacerbate LVOTO[15].

The clinical course of our patient is consistent with the phenomenon termed suicide LV (SLV), a rare yet critical postoperative complication. SLV occurs as a result of abrupt afterload reduction in a hypertrophied, hypercontractile LV, resulting in increased dynamic intraventricular gradients, SAM of the MV, and diminished CO[17,18]. While typically linked to aortic stenosis and AVR, isolated instances without aortic valve pathology have been reported, highlighting the significance of extreme left ventricular hypertrophy and sudden vasoplegia. Risk factors for SLV encompass small left ventricular cavity dimensions, septal hypertrophy, pre-existing SAM, and female gender[17-19]. Identifying SLV as an often-overlooked cause of postoperative cardiogenic shock is crucial for directing prompt diagnostic and treatment measures[17-19].

The management of SLV necessitates a comprehensive strategy focused on stabilizing hemodynamics and alleviating LVOT blockage. Therapeutic approaches focus on volume loading to enlarge the ventricular cavity, beta-blockade to decrease contractility and HR, and the administration of vasoconstrictors to elevate systemic vascular resistance without increasing myocardial oxygen consumption. Inotropes are generally contraindicated as they may exacerbate LVOTO. In refractory cases, procedural procedures such surgical myectomy or alcohol septal ablation are deemed appropriate[19,20]. Preventive techniques encompass meticulous preoperative TTE evaluation to identify high-risk patients, intra-procedural volume optimization, and, in specific instances, prophylactic septal reduction therapy to reduce the likelihood of SLV development[20]. Multidisciplinary perioperative care is essential for enhancing outcomes in these difficult scenarios.

Vasopressin seems to be the preferred vasopressor in instances of LVOTO and SAM post-cardiac surgery, likely due to its absence of inotropic effects relative to norepinephrine. Continuous bedside echocardiographic monitoring is crucial not only for early diagnosis and assessment, but also for guiding the selection and titration of vasopressor therapy.

| 1. | Guigui SA, Torres C, Escolar E, Mihos CG. Systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a narrative review. J Thorac Dis. 2022;14:2309-2325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ibrahim M, Rao C, Ashrafian H, Chaudhry U, Darzi A, Athanasiou T. Modern management of systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41:1260-1270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Makhija N, Magoon R, Balakrishnan I, Das S, Malik V, Gharde P. Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction following aortic valve replacement: A review of risk factors, mechanism, and management. Ann Card Anaesth. 2019;22:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Slama M, Tribouilloy C, Maizel J. Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in ICU patients. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016;22:260-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Evans JS, Huang SJ, McLean AS, Nalos M. Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction-be prepared! Anaesth Intensive Care. 2017;45:12-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Levy JH, Tanaka KA. Inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:S715-S720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 408] [Cited by in RCA: 415] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bartunek J, Sys SU, Rodrigues AC, van Schuerbeeck E, Mortier L, de Bruyne B. Abnormal systolic intraventricular flow velocities after valve replacement for aortic stenosis. Mechanisms, predictive factors, and prognostic significance. Circulation. 1996;93:712-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Moreno Garijo J, Ibáñez C, Perdomo JM, Abel MD, Meineri M. Preintervention imaging and intraoperative management care of the hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy patient. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2022;30:35-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Overgaard CB, Dzavík V. Inotropes and vasopressors: review of physiology and clinical use in cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2008;118:1047-1056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mampuya WM, Dumont J, Lamontagne F. Norepinephrine-associated left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and systolic anterior movement. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:e225879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Arnold AD, Howard JP, Chiew K, Kerrigan WJ, de Vere F, Johns HT, Churlilov L, Ahmad Y, Keene D, Shun-Shin MJ, Cole GD, Kanagaratnam P, Sohaib SMA, Varnava A, Francis DP, Whinnett ZI. Right ventricular pacing for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: meta-analysis and meta-regression of clinical trials. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2019;5:321-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ooi LG, O'Shea PJ, Wood AJ. Use of esmolol in the postbypass management of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Br J Anaesth. 1993;70:104-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pablo CR, David AO, Carlos V, Álvaro A, Williams H, Carolina I, Marta M, Leonor NM, Ignacio A, San Román A. Beta Blockers as Salvage Treatment in Refractory Septic Shock Complicated With Dynamic Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction: A Rare Case Presentation. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2021;9:23247096211056491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yimin H, Xiaoyu L, Yuping H, Weiyan L, Ning L. The effect of vasopressin on the hemodynamics in CABG patients. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;8:49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Monaco F, D'Amico F, Barucco G, Licheri M, Novellis P, Ciriaco P, Veronesi G. Mitral Valve Systolic Anterior Motion in Robotic Thoracic Surgery as the Cause of Unexplained Hemodynamic Shock: From a Case Report to Recommendations. J Clin Med. 2022;11:6044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Balik M, Novotny A, Suk D, Matousek V, Maly M, Brozek T, Tavazzi G. Vasopressin in Patients with Septic Shock and Dynamic Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2020;34:685-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lioufas PA, Kelly DN, Brooks KS, Marasco SF. Unexpected suicide left ventricle post-surgical aortic valve replacement requiring veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support despite gold-standard therapy: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2022;6:ytac020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Naseerullah FS, Wickramasinghe SR. Unusual case of post-operative suicide left ventricle in a patient with dynamic LVOT obstruction. J Cardiol Cases. 2022;26:236-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Romano S, D'Andrea E, Cozac DA, Savo MT, Cecchetto A, Baritussio A, Martini M, Napodano M, Bauce B, Pergola V. Silent Threats of the Heart: A Case Series and Narrative Review on Suicide Left Ventricle Post-Aortic Valve Replacement in Patients with Dynamic LVOT Obstruction and Aortic Stenosis. J Clin Med. 2024;13:5555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chraibi H, Bakamel L, Fellat R, Bendagha N, Moughil S. Conservative Management of Suicide Left Ventricle After Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement. Cureus. 2023;15:e42890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/