Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.106359

Revised: April 1, 2025

Accepted: May 29, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 277 Days and 6.1 Hours

Excessive noise in healthcare environments—commonly described as "unwanted sound"—has been linked to a range of negative impacts on both patients and staff. In clinical settings, elevated noise levels have been associated with sleep disruption, heightened cardiovascular stress, and an increased risk of delirium in patients. Among healthcare workers, noise can impair focus and cognitive perfor

To evaluate the effectiveness of educational and behavioural interventions in reducing noise levels within intensive care units (ICUs), recognizing their poten

A prospective interventional study in two Singaporean teaching hospitals compared peak and average sound levels between control and intervention groups. An educational and behavioural intervention comprising talks, posters, and self-audits by nurse champions was initiated in two ICUs in one hospital on November 18, 2023. Sound measurements were collected at 4 Locations within each ICU before and after intervention. Baseline measurements were taken from October 22, 2023 to October 29, 2023, and post-intervention measurements from December 21, 2023 to December 22, 2023. The hospitals served as the primary exposure variable, controlled for ICU type (medical vs surgical) and hour of the day.

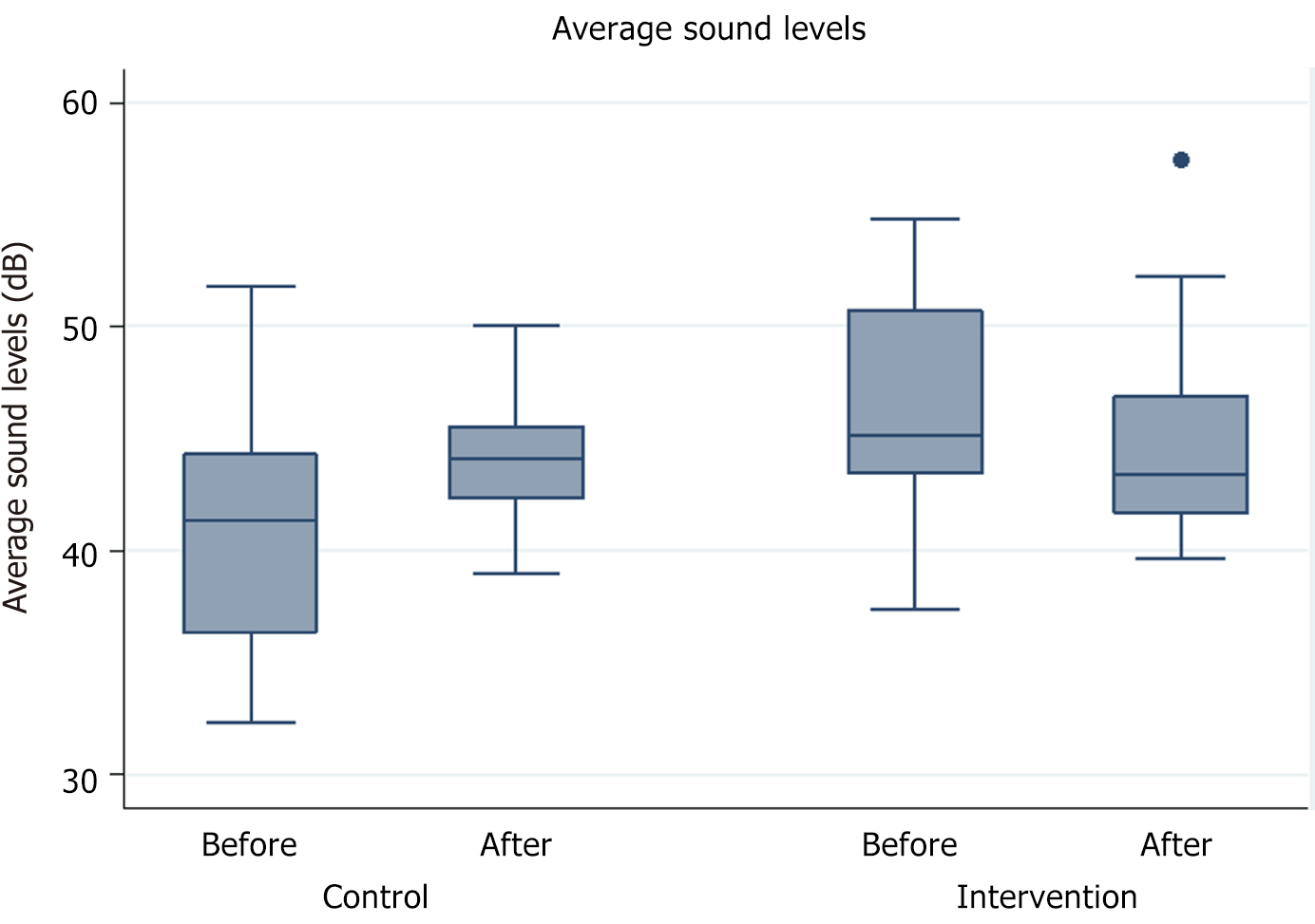

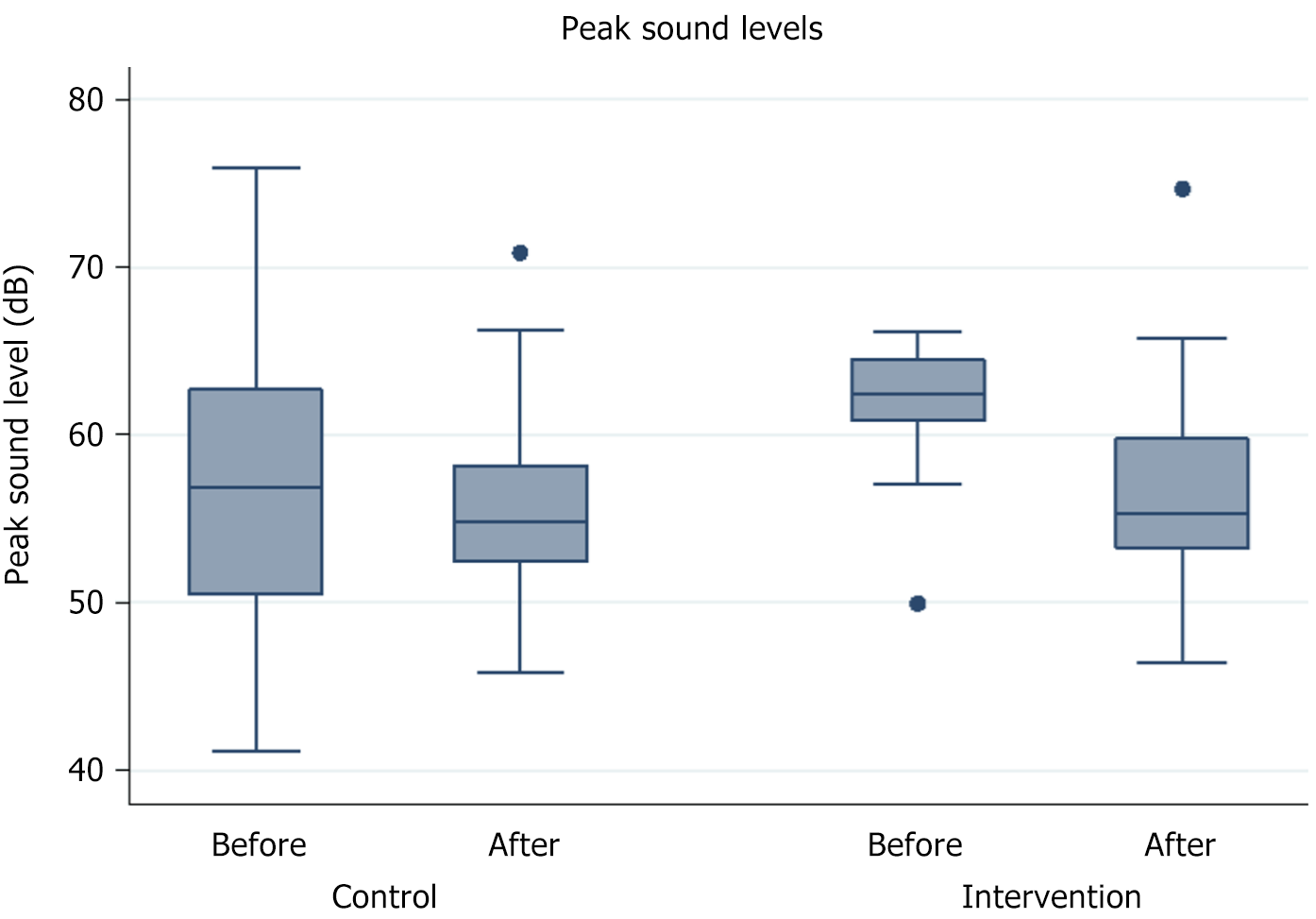

Our analysis generated 48 pairs of peak and average sound level readings for each unit (control n = 48 readings; intervention n = 48 readings). The effect of the intervention was associated with a significant 4.8 dB decrease in average sound level (P = 0.009) and a nonsignificant 4.3 dB decrease in peak sound level (P = 0.104), adjusted for hour of day and type of ICU.

Educational and behavioural interventions successfully reduced average sound levels, emphasizing their positive impact on noise control. These findings contribute valuable insights for optimizing noise reduction efforts in critical care settings. Future studies may explore additional systemic and environmental interventions to enhance noise management strategies.

Core Tip: Educational and behavioural interventions demonstrated success in reducing average sound levels, emphasizing their positive impact on noise control. These findings contribute valuable insights for optimizing noise reduction efforts in critical care settings.

- Citation: Ong B, See KC, Kim SS, Lau YH. Effectiveness of a noise reduction intervention in the intensive care unit: A prospective bicenter study. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(4): 106359

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i4/106359.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.106359

Noise, defined as any sound that may produce an undesired physiological or psychological effect in an individual or group[1] or simply as “unwanted sound”[2], has demonstrated detrimental effects on patient outcomes and healthcare effectiveness. Undesired consequences include increased cardiovascular risk[3], sleep disturbances[4], associations with delirium[5,6] in patients, as well as impedance in concentration and cognitive function[1,7] among healthcare workers.

Critically ill patients, particularly sensitive to noise-induced sleep disruption[1,8], often experience sound levels exceeding acceptable thresholds. Daytime sound pressures average around 60 A-weighted decibels (dBA), while nighttime levels reach 50 dBA[9,10], with peak levels above 90 dBA[9-11]. These significantly surpass the World Health Organization-recommended LAeq 30 for hospitals, leading to sleep disturbances during nighttime in hospital settings[2].

Prior studies have attempted to mitigate noise levels in the intensive care units (ICUs) through various interventions, demonstrating some success, albeit with varying effectiveness[12-15]. However, further research is necessary to expand upon these efforts due to the complexity of the ICU environment. Factors such as patient acuity, medical equipment, and staff activities contribute to noise levels, making interventions that are effective in one ICU setting potentially ineffective in another. Our study seeks to evaluate the effectiveness of educational and behavioural interventions in reducing noise levels in the ICU. We hypothesize that educational and behavioural interventions will result in a reduction in noise levels in the ICU.

This was a prospective interventional study conducted in the ICUs of two major teaching hospitals in Singapore: National University Hospital (NUH) and Tan Tock Seng Hospital (TTSH). The requirement for ethics approval was waived by the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (reference number 2023/00558).

Pre- and post-intervention sound measurements were taken at selected common areas (four per ICU) within the NUH Medical ICU (MICU), TTSH MICU, NUH Surgical ICU (SICU), and TTSH SICU. Baseline sound measurements were collected between October 22, 2023 and October 29, 2023 (two Sundays) and post-intervention sound measurements were taken on December 21, 2023 and December 22, 2023.

Educational sessions to address the adverse impact of noise were conducted in TTSH for MICU and SICU staff over 2 days in November 2023 These sessions included a 3-minute virtual presentation outlining the adverse effects of noise (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RhOvN7yoHAY, Figure 1), followed by a 5-minute question-and-answer session focusing on intervention logistics. Staff engagement was further encouraged through email access to presentation slides and posters, as well as a self-funded prize incentive of 100 USD worth of food items for ICUs showing significant noise reduction. Intervention reinforcement was achieved with prominently displayed posters in the ICUs and systematic self-audits of noise levels during each shift, overseen by a designated nurse champion.

The investigator measured noise levels at the selected ICU locations-for at least 10 seconds–at three time points: 0715 hours, 1415 hours, and 2015 hours. Doctor's ward rounds typically occurred from 0800 hours to 1100 hours, 1500 hours to 1600 hours and nursing shift changes took place from 0700 hours to 0800 hours, 1300 to 1400 hours, 2000 to 2100 hours. Four pre-selected locations were chosen to represent noise levels within the common areas of each ICU. The mea

The study's primary outcomes included changes in peak and average sound levels, before and after intervention. The main exposure variable was the comparison between the two hospitals. A difference-in-differences linear regression analysis was done using average or peak sound level as the dependent variable, phase (pre-intervention vs post-intervention) and hospital (NUH vs TTSH) as indicator variables, and (phase x hospital) as the interaction term, adjusted for hour of day and type of ICU (MICU/SICU). Two pairs of data were analyzed: Control groups (NUH MICU and SICU) where no interventions occurred, and interventional groups (TTSH MICU and SICU) where interventions were implemented. All p-values and confidence limits were calculated as two-sided. Statistical significance was taken as P < 0.05. The statistical analyses were done using Stata SE version 13.1.

Our analysis generated 48 pairs of peak and average sound level readings for each unit (Control n = 48 readings; Intervention n = 48 readings). The effect of intervention was associated with a significant 4.8 dB decrease in average sound level (P = 0.009) (Table 1, Figure 2), and a nonsignificant 4.3 dB decrease in peak sound level (P = 0.104) (Table 2, Figure 3), adjusted for hour of day and type of ICU.

Given the well-documented impact of noise on patient outcomes and healthcare worker well-being[4-9,12,16,17], there is a pressing need to optimize noise management strategies in ICU settings. This interventional study assessed baseline noise levels and implemented educational and behavioural interventions to mitigate noise within the ICU.

The substantial reduction of 4.8 dB in average sound levels post-intervention, surpassing the threshold of 3 dBA as outlined by Darbyshire et al[17] for clinical relevance, indicates the effectiveness of our approach. Referring to previous studies on education and training in general ICUs, three studies demonstrated a significant noise decrease of 0.9 dBA[13] to 9 dBA[12,15]. However, these studies were conducted in a general ICU without controlling for ICU type. Another study in a general ICU, focusing on training and staff awareness with noise warning devices, found no noise reduction[14]. Discrepancies between studies may arise from differences in ICU layout, patient case mix, and the specific interventions implemented. Future research should consider real-time monitoring of patient acuity and workload metrics to better account for these external influences.

The non-significant change in peak noise levels (P = 0.104) aligns with prior ICU studies, which found that while structural or behavioral modifications reduce background noise, transient peaks from alarms, staff communication, or patient distress remain difficult to control[11,18]. These events are often sudden, brief, and unpredictable, contributing to greater variability and requiring larger sample sizes for statistical significance. Future studies should explore targeted interventions, such as alarm management protocols or sound-absorbing materials, and utilize larger datasets or alternative statistical methods to improve sensitivity in detecting changes.

Education and noise warning devices have shown effectiveness as single-intervention strategies for short-term noise reduction[16,19-24]. However, since most disruptive noises in the ICU stem from staff and visitor behaviour, structural changes in behaviour are needed. Complex interventions with multiple interacting components have been proposed to gradually lower sound levels. Evidence from implementation science suggests that multicomponent strategies are more effective in changing professional behaviour in the long term[17,25]. Therefore, initiatives such as appointing a nurse champion, as demonstrated in our study, could offer sustained benefits by maintaining regular noise level surveillance and reminders to manage noise for future staff.

Our study's strengths include its prospective interventional design, rigorous sound measurement, and robust difference-in-differences analysis. However, limitations exist, and future research should address confounders, enhance patient stratification, and improve generalizability with larger, more diverse samples.

Environmental factors such as patient acuity, equipment use, and staff workload likely contributed to noise variability. Higher acuity necessitates more bedside interventions and alarms[26], while staff workload fluctuations impact noise through increased communication and movement[10]. Despite standardized measurement times and locations, residual confounding remains. Future studies should incorporate real-time workload metrics and patient severity indices to better isolate intervention effects.

Expanding data collection—such as 24-hour surveillance, intra-room sound levels, patient-provider interactions, and patient comfort—can provide deeper insights into ICU noise perception. Controlling for confounders like census, comorbidities, and staff variability is essential for reliability.

Conducted in two major Singaporean teaching hospitals, our findings may not be fully generalizable. ICU noise is shaped by institutional policies, staff practices, patient demographics, and ICU layouts, which vary across settings. While our structured approach provides a framework for future studies, further research in diverse ICUs is needed to confirm its broader applicability.

Behavioural and educational interventions, while effective in instigating change, are susceptible to the fadeout phenomenon[27], and represent only a subset of available methods[28]. Recognizing this, we recommend future studies explore diverse intervention methods and their cost, effectiveness, and duration. To assess noise level reduction efficacy comprehensively, future studies should enable a direct correlation with patient outcomes such as mood, length of stay and sleep quality. Integrating simultaneous data collection on parameters influenced by noise would offer more applicable insights into healthcare performance. Future interventions should be effective, practical, and cost-effective.

In summary, our educational and behavioral interventions significantly reduced average sound levels in the ICU. Moving forward, tailored strategies in diverse ICU environments and assessment of long-term effects on patients will be required to pave the way for more targeted and effective noise reduction measures in critical care settings.

| 1. | National Service Center for Environmental Publications (NSCEP). Noise Effects Handbooks: a Desk Reference to Health and Welfare Effects of Noise. Available from: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyNET.exe/9100OOAJ.TXT?ZyActionD=ZyDocument&Client=EPA&Index=1981+Thru+1985&Docs=&Query=&Time=&EndTime=&SearchMethod=1&TocRestrict=n&Toc=&TocEntry=&QField=&QFieldYear=&QFieldMonth=&QFieldDay=&IntQFieldOp=0&ExtQFieldOp=0&XmlQuery=&File=D%3A%5Czyfiles%5CIndex%20Data%5C81thru85%5CTxt%5C00000018%5C9100OOAJ.txt&User=ANONYMOUS&Password=anonymous&SortMethod=h%7C-&MaximumDocuments=1&FuzzyDegree=0&ImageQuality=r75g8/r75g8/x150y150g16/i425&Display=hpfr&DefSeekPage=x&SearchBack=ZyActionL&Back=ZyActionS&BackDesc=Results%20page&MaximumPages=1&ZyEntry=1&SeekPage=x&ZyPURL. |

| 2. | Berglund B, Lindvall T, Schiele DH; World Health Organization O; and Environmental Health T. Guidelines for community noise. 1999. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/66217. |

| 3. | Hahad O, Kröller-Schön S, Daiber A, Münzel T. The Cardiovascular Effects of Noise. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116:245-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Basner M, McGuire S. WHO Environmental Noise Guidelines for the European Region: A Systematic Review on Environmental Noise and Effects on Sleep. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 38.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hansell HN. The behavioral effects of noise on man: the patient with "intensive care unit psychosis". Heart Lung. 1984;13:59-65. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Wong IMJ, Thangavelautham S, Loh SCH, Ng SY, Murfin B, Shehabi Y. Sedation and Delirium in the Intensive Care Unit-A Practice-Based Approach. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2020;49:215-225. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Murthy VS, Malhotra SK, Bala I, Raghunathan M. Detrimental effects of noise on anaesthetists. Can J Anaesth. 1995;42:608-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gabor JY, Cooper AB, Crombach SA, Lee B, Kadikar N, Bettger HE, Hanly PJ. Contribution of the intensive care unit environment to sleep disruption in mechanically ventilated patients and healthy subjects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:708-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Simons KS, Verweij E, Lemmens PMC, Jelfs S, Park M, Spronk PE, Sonneveld JPC, Feijen HM, van der Steen MS, Kohlrausch AG, van den Boogaard M, de Jager CPC. Noise in the intensive care unit and its influence on sleep quality: a multicenter observational study in Dutch intensive care units. Crit Care. 2018;22:250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lim WY, Aung HT, See KC. Patterns and predictors of sound levels in hospital rooms. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2022;51:55-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Darbyshire JL, Young JD. An investigation of sound levels on intensive care units with reference to the WHO guidelines. Crit Care. 2013;17:R187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Taraghi Z, Zamani K, Asgharnia H, Yazdani J. The effect of staff training on the amount of sound pollution in the intensive care unit. J Nurs Midwifery Sci. 2018;5:130. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yıldırım Ar A, Turan G, Enez Alay E, Demiroluk Ö, Yiğit Kuplay Y, Karaca D. What can We Do for Noise Awareness in Intensive Care? tybd 2018; 16: 10-16. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Souza RCDS, Calache ALSC, Oliveira EG, Nascimento JCD, Silva NDD, Poveda VB. Noise reduction in the ICU: a best practice implementation project. JBI Evid Implement. 2022;20:385-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Duarte ST, Matos M, Tozo TC, Toso LC, Tomiasi AA, Duarte PA. [Practicing silence: educational intervention for reducing noise in the intensive care unit]. Rev Bras Enferm. 2012;65:285-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Redert R. Doplor: Artful warnings towards a more silent Intensive Care. 2018. Available from: https://delftdesignlabs.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/CJRedert_MasterThesis_4275683_Report-compressed.pdf. |

| 17. | Darbyshire JL, Duncan Young J. Variability of environmental sound levels: An observational study from a general adult intensive care unit in the UK. J Intensive Care Soc. 2022;23:389-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Busch-Vishniac IJ, West JE, Barnhill C, Hunter T, Orellana D, Chivukula R. Noise levels in Johns Hopkins Hospital. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;118:3629-3645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Delaney LJ, Currie MJ, Huang HC, Lopez V, Van Haren F. "They can rest at home": an observational study of patients' quality of sleep in an Australian hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Guisasola-Rabes M, Solà-Enriquez B, Vélez-Pereira AM, de Nadal M. Effectiveness of a visual noise warning system on noise levels in a surgical ICU: A quality improvement programme. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2019;36:857-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jousselme C, Vialet R, Jouve E, Lagier P, Martin C, Michel F. Efficacy and mode of action of a noise-sensor light alarm to decrease noise in the pediatric intensive care unit: a prospective, randomized study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12:e69-e72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Plummer NR, Herbert A, Blundell JE, Howarth R, Baldwin J, Laha S. SoundEar noise warning devices cause a sustained reduction in ambient noise in adult critical care. J Intensive Care Soc. 2019;20:106-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Casey L, Fucile S, Flavin M, Dow K. A two-pronged approach to reduce noise levels in the neonatal intensive care unit. Early Hum Dev. 2020;146:105073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wensing M, Grol R. Single and combined strategies for implementing changes in primary care: a literature review. Int J Qual Health Care. 1994;6:115-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M, and Davis D. Improving patient care: the implementation of change in health care. John Wiley and Sons, 2013. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Ryherd EE, Waye KP, Ljungkvist L. Characterizing noise and perceived work environment in a neurological intensive care unit. J Acoust Soc Am. 2008;123:747-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bailey DH, Duncan GJ, Cunha F, Foorman BR, Yeager DS. Persistence and Fade-Out of Educational-Intervention Effects: Mechanisms and Potential Solutions. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2020;21:55-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, Hardeman W, and Eccles M. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol. 2008;57:660-680. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/