Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.108370

Revised: May 23, 2025

Accepted: August 5, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 230 Days and 22 Hours

Desmopressin (1-deamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin, DDAVP) is a synthetic analogue of arginine vasopressin, the body’s natural antidiuretic hormone. It acts selectively on V2 receptors, promoting renal water reabsorption and stimulating the release of von Willebrand factor (vWF) and factor VIII, while exerting minimal vasoconstrictive effects through V1 receptors. Developed in the late 1960s and introduced clinically in the early 1970s for the management of central diabetes insipidus, desmopressin was engineered to provide a longer duration of action and reduced cardiovascular side effects compared to native vasopressin. Its haemostatic potential was later recognized when it was observed to enhance endogenous levels of vWF and factor VIII, leading to its incorporation into the treatment of mild haemophilia A and von Willebrand disease (vWD). This unique combination of antidiuretic and prohemostatic properties has broadened its therapeutic role across various clinical settings. In critical care, desmopressin has emerged as a potentially valuable agent in managing complex scenarios such as uremic platelet dysfunction, trauma-associated coagulopathy, intracranial hemorrhage, vWD, and central diabetes insipidus. However, despite its mechanistic appeal and broad pharmacologic utility, the full scope of desmo

Core Tip: In recent years, desmopressin has emerged as a potentially valuable agent in managing complex scenarios such as uremic platelet dysfunction, trauma-associated coagulopathy, intracranial hemorrhage, von Willebrand disease, and central diabetes insipidus. These conditions may be particularly challenging to manage, especially in critically ill patients. Emerging evidence suggests that desmopressin use may improve surrogate outcomes such as bleeding time and transfusion reduction. However, its impact on long-term clinical outcomes remains under investigation. The primary safety concern is hypo

- Citation: Vinjamuri S, Tiwari E, Kataria S, Juneja D. Haemostasis and beyond: The expanding role of desmopressin in intensive care. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(4): 108370

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i4/108370.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.108370

Vasopressin, also known as antidiuretic hormone (ADH), is a naturally occurring peptide that regulates both water homeostasis and vascular tone through V2 and V1 receptor activation, respectively. Desmopressin (1-deamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin, or DDAVP) is a synthetic analogue of vasopressin specifically designed to selectively activate V2 receptors[1]. This selective activity enhances water reabsorption in the kidneys while minimizing vasoconstrictive effects, making desmopressin safer for clinical use in various settings. Initially developed to manage central diabetes insipidus and nocturnal enuresis, desmopressin has also been widely adopted for certain hematologic conditions, particularly mild haemophilia A and type 1 von Willebrand disease (vWD), where it stimulates the release of stored factor VIII and von Willebrand factor (vWF) from endothelial cells[1].

In recent years, desmopressin’s role has expanded significantly beyond its approved indications, particularly in critical care environments. It is now frequently used off-label for a variety of complex and emergent clinical conditions such as uremic platelet dysfunction, trauma-induced coagulopathy, spontaneous intracranial haemorrhage in patients taking antiplatelet agents, platelet dysfunction due to hepatic impairment, and bleeding following cardiopulmonary bypass[2,3]. Furthermore, it remains an essential therapeutic option in managing central diabetes insipidus arising from neurosurgical procedures or neurologic injuries[4].

However, despite its increasing application in intensive care units (ICUs), desmopressin use remains largely empirical in many of these off-label contexts. There is no universally accepted guidance on optimal dosing strategies, timing of administration, or patient selection. Clinicians often rely on limited evidence, expert consensus, or extrapolation from non-ICU settings, and therapeutic decisions are frequently guided by surrogate outcomes such as improvements in bleeding time or platelet function assays. Precise data on clinical endpoints—such as reductions in transfusion needs, improved survival, or enhanced neurological outcomes—are sparse. Moreover, desmopressin’s antidiuretic properties can lead to complications like water retention and hyponatremia, necessitating careful fluid management and monitoring.

This review examines the pharmacologic properties of desmopressin and its clinical applications in critical care. It synthesizes current evidence on indications, dosing strategies, efficacy, and safety across various ICU settings while identifying gaps in the literature and areas requiring further investigation.

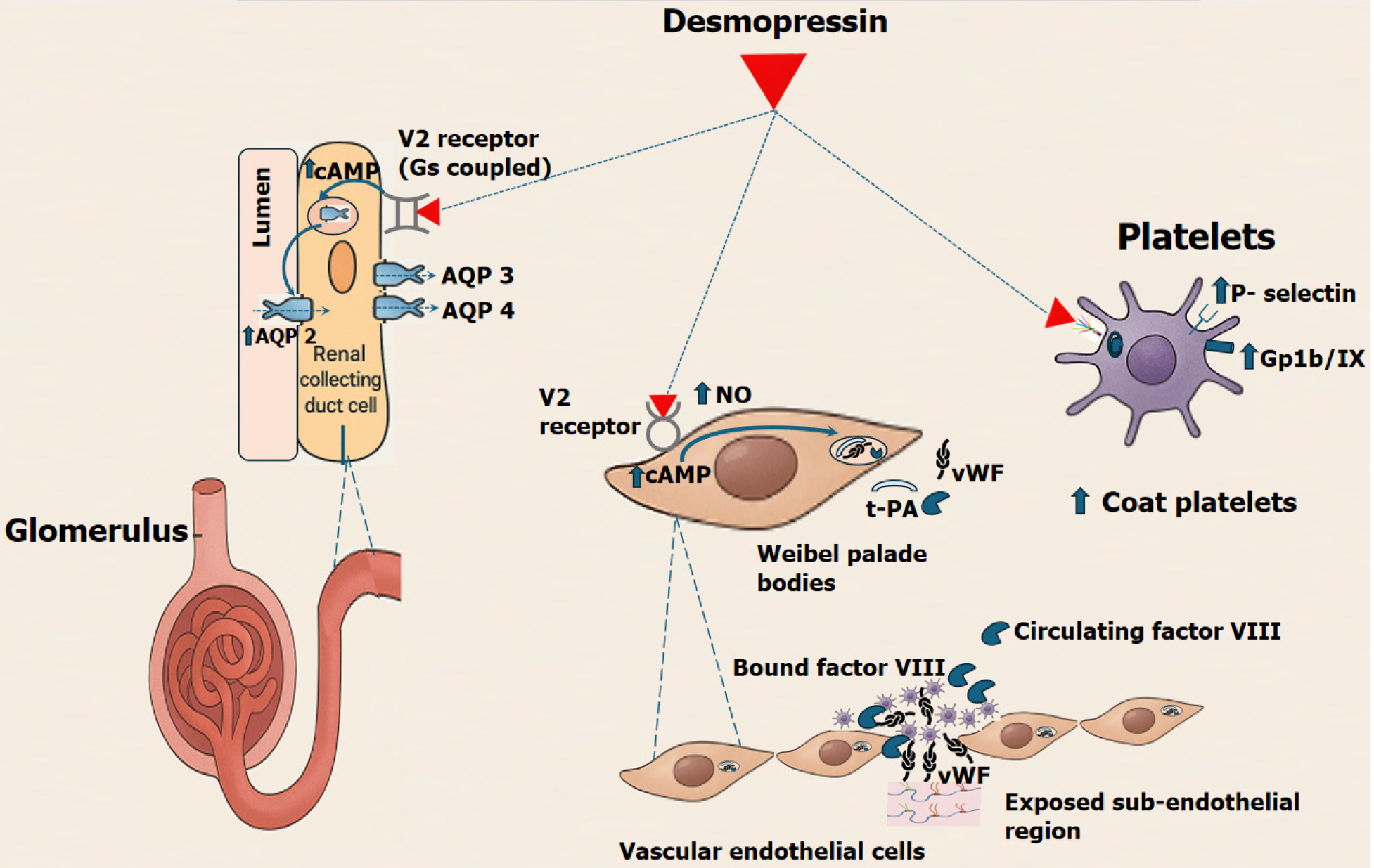

Desmopressin is a synthetic analogue of the endogenous hormone vasopressin, engineered to exhibit selective affinity for V2 receptors primarily located in the renal collecting ducts and vascular endothelium while demonstrating minimal activity at V1 receptors[5]. Structural modifications—expressly, the deamination of the N-terminal cysteine and substituting the eighth amino acid (L-arginine) with its stereoisomer D-arginine—enhance receptor selectivity and confer resistance to enzymatic degradation. These alterations prolong its biological half-life and enable a targeted pharmacologic profile characterized by potent antidiuretic and haemostatic effects with minimal vasopressor activity[6,7]. The antidiuretic-to-pressor activity ratio is estimated to be between 1:2000 and 1:3000, indicating a markedly reduced impact on systemic vascular resistance compared to native vasopressin[8]. This pharmacodynamic profile is especially beneficial in clinical scenarios where avoiding vasoconstriction is critical, such as in patients with hemodynamic instability or at elevated risk for cerebral ischemia. Moreover, it can promote vasodilation through selective endothelial V2 receptor activation, releasing nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclin.

In the kidneys, activation of V2 receptors leads to increased cyclic AMP levels, promoting the insertion of aquaporin-2 channels into the collecting duct membranes[4,5]. This enhances water reabsorption, making desmopressin effective for conditions like diabetes insipidus. In the vascular endothelium, stimulation of V2 receptors induces the release of stored vWF and factor VIII from Weibel-Palade bodies, improving platelet adhesion and clot stability. While it may also modestly enhance the release of tissue plasminogen activator, the pro-haemostatic effects of vWF and factor VIII dominate (Figure 1). Beyond endothelial effects, desmopressin directly modulates platelet function via V2 receptors expressed on platelets. V2-mediated cAMP signaling promotes the formation of collagen and thrombin-activated (COAT) platelets—a highly procoagulant subpopulation characterized by enhanced phosphatidylserine exposure, increased fibrin-binding capacity, and robust granule release[9]. COAT platelets play a critical role in stabilizing clot formation, particularly in conditions marked by impaired primary haemostasis, such as uraemia or antiplatelet drug exposure.

Desmopressin also increases surface expression of P-selectin and GPIIb/IIIa, facilitating platelet aggregation and adhesion. These effects have been corroborated by improvements in clot strength and platelet responsiveness in thromboelastography and platelet function assays. Importantly, desmopressin achieves this haemostatic augmentation without stimulating systemic vasoconstriction, making it a favorable option in critically ill patients at risk of bleeding but vulnerable to ischemic complications from vasopressors.

Collectively, these mechanisms enable desmopressin to enhance both coagulation factor availability and platelet function without requiring blood product transfusion, thereby offering a safe and effective adjunct in managing bleeding associated with mild factor deficiencies or qualitative platelet disorder.

Desmopressin is available in intravenous (IV), subcutaneous (SC), intranasal, and sublingual forms[5-7,10]. Desmopressin exhibits route-dependent pharmacokinetics, with intravenous administration offering the most rapid and predictable onset—typically within 15-30 minutes, with peak effect at 60-90 minutes. The haemostatic effect generally lasts 6-12 hours, while the antidiuretic action may persist longer depending on the route. The route of desmopressin administration is guided by clinical indication, urgency, and patient-specific factors (Table 1).

| Route | Typical dose | Time to peak effect | Half-life (healthy) | Half-life (renal impairment) | Clinical notes |

| Intravenous | 0.3 µg/kg over 20-30 min | 30-60 minutes | 2-4 hours | 8-10 hours | Preferred in ICU for bleeding control and acute DI |

| Subcutaneous | 0.3 µg/kg | 60-90 minutes | 2-4 hours | Approximately 8 hours | Practical alternative when IV access is unavailable |

| Intranasal | 150-300 µg (1-2 sprays) | 60-90 minutes | Approximately 3 hours | Extended | Often used for chronic bleeding disorders or enuresis |

| Sublingual melt | 120 µg (paediatric use) | 60-90 minutes | Approximately 3 hours | Extended | Suitable for children or outpatient settings |

IV administration ensures rapid systemic absorption, making it the preferred choice for acute management in intensive care. Intravenous delivery is optimal for rapid haemostatic or antidiuretic effects and is commonly used in acute care scenarios such as active bleeding or severe central diabetes insipidus. The typical IV dose is 0.3 µg/kg, with peak levels achieved within 30-60 minutes.

Subcutaneous administration, using the exact dosage of 0.3 µg/kg, provides a slower onset and is often used in non-urgent settings or when IV access is limited[11]. Intranasal spray formulations are preferred for long-term management of mild bleeding disorders or nocturnal enuresis. Dosing varies with body weight—patients under 50 kg generally require one spray (150 µg), while those over 50 kg may need two sprays (300 µg), typically administered every 12 to 24 hours.

Sublingual desmopressin, often used in paediatric populations, offers a convenient, non-invasive route. It is typically available as a 120 µg melt tablet that dissolves under the tongue for rapid absorption. This method is beneficial when intravenous or nasal routes are not feasible or preferred.

The drug is minimally metabolized hepatically and is primarily excreted unchanged by the kidneys, necessitating cautious dosing to mitigate risks (Table 2). In healthy individuals, the plasma half-life is approximately 3.5 hours, but this may be prolonged to 6-9 hours in renal impairment, increasing the risk of hyponatremia and fluid overload due to sustained antidiuretic activity[5,6]. Regardless of administration route, dosing should be individualized based on weight, renal function, and clinical response, with vigilant monitoring of serum sodium, fluid balance, and urine output.

| Clinical setting | eGFR | Recommended dose | Dosing interval | Key considerations |

| Mild-Moderate renal impairment | eGFR 30-60 mL/min | 0.15-0.2 µg/kg IV or SC | Every 24-48 hours | Monitor serum sodium every 6-12 hours; avoid free water intake |

| Severe renal impairment | eGFR < 30 mL/min | Avoid for antidiuresis | — | High risk of hyponatremia and water intoxication |

| End stage renal disease/hemodialysis (for bleeding only) | On dialysis | 0.3 µg/kg IV over 20-30 minutes | Single dose only; no repeat within 48-72 hours | Administer post-dialysis; enforce strict fluid restriction (≤ 1 L/day); monitor sodium every 6-8 hours |

| Hepatic dysfunction (e.g., Cirrhosis) | All stages | 0.3 µg/kg IV over 20-30 minutes | Single dose only | Use for variceal bleeding or pre-procedure; monitor for thrombosis; avoid repeat dosing |

Tachyphylaxis to desmopressin, due to depletion of endothelial vWF and factor VIII stores, limits its repeated use. To preserve haemostatic efficacy, doses should be spaced 12-24 hours apart, with no more than 2-3 doses over 72 hours. This effect is more related to dosing frequency than total dose. In critical care, careful scheduling is essential to maintain response for procedures or bleeding control while reducing risks like hyponatremia and fluid overload.

Uremic bleeding: Uremic bleeding represents a significant and often underrecognized complication in patients with acute kidney injury (AKI) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD). It typically manifests as mucocutaneous bleeding or haemorrhagic complications during invasive procedures and is primarily attributed to complex qualitative platelet dysfunction[12]. Contributing factors include the accumulation of uremic toxins, altered multimer distribution and function of vWF, chronic anaemia, and increased NO and prostacyclin levels. These factors impair platelet adhesion, aggregation, and interaction with the vascular endothelium, leading to prolonged bleeding times despite a normal platelet count. While dialysis can partially reduce circulating uremic toxins and improve haemostasis, it does not entirely correct platelet abnormalities. It may paradoxically increase bleeding risk due to anticoagulation and blood-surface interactions with dialysis membranes.

Desmopressin has emerged as an effective first-line agent for the acute management of uraemic bleeding. Des

In a prospective study of 23 uremic patients receiving antiplatelet therapy and requiring urgent interventions, administration of desmopressin (0.3 µg/kg IV) significantly shortened mean PFA-100 closure time from 252 ± 41 seconds to 145 ± 51 seconds (P < 0.001). No major bleeding or thrombotic complications were observed[15]. A separate randomized trial also demonstrated significant improvement in platelet function as measured by closure times using collagen/epinephrine (from 212 ± 58 to 152 ± 45 seconds, P = 0.01) and collagen/ADP (from 189 ± 78 to 147 ± 58 seconds, P = 0.012). These changes correlated with increases in FVIII levels (from 188 ± 66% to 252 ± 93%) and vWF levels (from 113 ± 9% to 121 ± 9%) post-infusion[16].

Despite this promising evidence, careful patient selection remains essential. The utility of bleeding time as a diagnostic tool for identifying uremic platelet dysfunction is limited. Although it was historically employed in early studies to evaluate treatment response, the bleeding time has fallen out of favour due to its poor reproducibility, high operator variability, and limited predictive value for actual bleeding risk. It is neither specific to uraemia nor sufficiently sensitive to guide therapy decisions[17]. In contrast, platelet function assays such as the PFA-100 provide a more standardized and reliable assessment of primary haemostasis and are better suited for identifying patients likely to benefit from desmopressin. In practice, the decision to administer desmopressin should be guided by clinical factors, including elevated urea levels, antiplatelet use, bleeding history, and procedural risk, rather than bleeding time alone.

For haemostatic purposes in uremic bleeding, desmopressin is typically administered as a single dose of 0.3-0.4 µg/kg intravenously over 20-30 minutes or subcutaneously (Table 3). This dosage is approximately tenfold higher than that used for antidiuretic indications. Clinical effects generally appear within 30 to 60 minutes of administration and last approximately 6 to 8 hours[10].

| Clinical Indication | Desmopressin dose and route | Frequency/duration | Monitoring/notes |

| Uremic bleeding (end-stage renal disease) | 0.3 µg/kg IV (approximately 20-30 µg) | Single dose; may repeat in 24 hours with caution | Check bleeding time or PFA-100 if available; effect begins in approximately 1 hour, lasts 6-8 hours. Implement fluid restriction for 12-24 hours post-dose |

| Antiplatelet-associated intracerebral hemorrhage | 0.4 µg/kg IV (max approximately 30 µg) | One-time dose at presentation | Administer promptly upon confirmation of hemorrhage. Monitor blood pressure during infusion (risk of hypotension). Reassess hematoma size on imaging. No routine repeat dosing |

| Trauma-induced coagulopathy (suspected platelet dysfunction/vWD) | 0.3 µg/kg IV | Single dose early during resuscitation | Indicated for patients on antiplatelet agents or with known vWD. Incorporate into massive transfusion protocols. Monitor bleeding parameters (e.g., TEG/ROTEM). Not for empirical use |

| Inherited von Willebrand disease (type 1 and select type 2) | 0.3 µg/kg IV/SC or 300 µg intranasal (150 µg/nostril) | Single dose; repeat in 12-24 hours if needed (max 2-3 doses) | Verify normal serum sodium before administration. Trial dose recommended to confirm responsiveness. Ineffective in Type 3 vWD—use vWF concentrate instead. Monitor vWF: FVIII levels if possible |

| Qualitative platelet dysfunction (e.g., CPB, liver disease) | 0.3 µg/kg IV | One-time dose as needed for diffuse bleeding | Use in microvascular bleeding when platelet count is adequate but function impaired. Observe bleeding control (e.g., chest drain output). Consider adjunctive use of TXA |

| Central diabetes insipidus | 1-2 µg IV/SC (fixed dose) | q8-12h; titrate based on clinical response | Monitor urine output hourly, urine specific gravity, and serum sodium every 4-6 hours. Adjust dose to maintain balanced output and stable sodium. Reduce or pause if sodium drops rapidly. Transition to oral/intranasal forms when stable |

Repeat dosing of desmopressin within 24 hours is not generally recommended due to tachyphylaxis, which is believed to result from depletion of endothelial vWF stores. If bleeding recurs or persists beyond the effective window, alternate therapies—such as cryoprecipitate or platelet transfusion—should be considered[10,18].

Desmopressin's rapid and transient pro-haemostatic action and ability to circumvent transfusion-related risks underscores its importance in managing uremic coagulopathy. As part of a comprehensive haemostatic strategy that includes dialysis optimization and correction of anaemia, desmopressin enhances procedural safety and supports hemodynamic stability.

Although primarily excreted via the kidneys, desmopressin’s antidiuretic activity is attenuated in advanced renal disease due to impaired urinary concentrating ability and reduced glomerular filtration. These physiological adaptations mitigate the risk of dilutional hyponatremia, particularly in anuric dialysis patients[10]. When used with appropriate fluid restriction and clinical monitoring, desmopressin remains safe and effective in this population despite its prolonged half-life (up to 10 hours).

In the absence of large randomized controlled trials evaluating complex clinical outcomes such as mortality or transfusion avoidance, the role of desmopressin in uremic bleeding remains supported by a growing body of observational evidence and long-standing clinical use. It continues to serve as a valuable adjunct in the acute management of bleeding in patients with AKI or ESRD, especially in perioperative and critical care settings. Future studies are warranted to refine dosing protocols, evaluate optimal timing, and better define patient selection criteria in the critically ill renal population.

Trauma-induced coagulopathy: Trauma-induced coagulopathy is a complex and acute condition arising after major trauma, characterized by impaired clot formation and uncontrolled bleeding. It develops through a combination of severe tissue injury, hypoperfusion, inflammation, and the compounding effects of hypothermia, acidosis, and haemodilution. These physiological insults disrupt normal coagulation pathways and can impair platelet function even when platelet counts remain within normal limits[19]. The presence of pre-injury antiplatelet medications such as aspirin or clopidogrel further exacerbates the risk of bleeding complications, particularly in cases involving traumatic brain injury.

Unlike antifibrinolytic agents such as tranexamic acid, which prevents clot breakdown, desmopressin acts on primary haemostasis by promoting the release of vWF and factor VIII, thereby enhancing platelet adhesion and aggregation. This mechanism of action makes it particularly useful in trauma patients with suspected or confirmed platelet dysfunction, such as those taking antiplatelet medications or those with inherited bleeding disorders[20]. Desmopressin’s role in trauma is, therefore, targeted rather than universal. It is not indicated for all trauma patients but is most beneficial in selected individuals with impaired platelet function.

The 2019 European Guidelines on the Management of Bleeding and Coagulopathy in Trauma recommended considering a single intravenous dose of desmopressin (0.3 µg/kg over 20-30 minutes) for actively bleeding patients with known antiplatelet therapy or diagnosed platelet dysfunction (Table 3), primarily to enhance platelet adhesion while minimizing the risk of hypotension. However, this recommendation was omitted from the 2023 update due to limited supporting evidence and a lack of robust clinical data[21,22].

Desmopressin typically takes effect within 30 minutes and temporarily enhances platelet activity for several hours. Repeat dosing is generally not advised due to the depletion of endothelial stores of vWF.

The advantages of desmopressin in trauma include its ability to rapidly improve primary haemostasis, its utility in reversing antiplatelet-induced dysfunction, and its potential to reduce the need for transfusions. Its rapid onset is particularly valuable in emergency settings where time-sensitive decisions are critical. However, limitations include its short duration of action, the potential for hyponatremia due to its antidiuretic properties, and the risk of hypotension if infused too rapidly[1]. Additionally, its benefit is confined to patients with demonstrable platelet-related haemostatic deficits. In those with normal platelet function or other coagulopathies, such as fibrinogen deficiency, desmopressin offers little to no benefit[23].

In summary, desmopressin represents a valuable adjunct in the management of trauma-induced coagulopathy when applied selectively. Its mechanism and effects complement other haemostatic interventions such as tranexamic acid and blood component therapy. Optimal outcomes depend on judicious patient selection, guided by clinical context and point-of-care coagulation testing. Through this individualized approach, desmopressin can significantly contribute to the broader strategy of bleeding control in critically injured patients.

Neurosurgical bleeding: Subarachnoid and intracerebral hemorrhage: Spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH) and subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) are neurologic emergencies frequently encountered in neurocritical care units. A significant proportion of patients with ICH present while on antiplatelet therapy, which has been associated with increased hematoma expansion, poor neurological outcomes, and elevated mortality[24]. The challenge of managing bleeding in these patients is compounded by the absence of definitive reversal agents for antiplatelet medications.

Although platelet transfusion has been explored, particularly in the Platelet transfusion vs standard care after acute stroke due to spontaneous cerebral haemorrhage associated with antiplatelet therapy (PATCH) trial, it failed to demonstrate benefit and was associated with potential harm[25]. This has led to interest in desmopressin as a pharmacological alternative capable of improving platelet function. By promoting the release of vWF and factor VIII, desmopressin enhances platelet adhesion and aggregation, thereby contributing to haemostasis in patients with antiplatelet-associated ICH. Notably, the DASH trial (a phase II randomized study) found that desmopressin was well tolerated, with no significant increase in adverse events such as hyponatremia or thrombotic complications[3]. Also, Recent evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis involving 598 patients with antiplatelet-associated intracranial haemorrhage further enhances clinical practice. This study found that desmopressin use was associated with a non-significant reduction in hematoma expansion and thrombotic events. However, it also reported a statistically significant increase in poor neurological outcomes (RR = 1.31), raising concerns about potential harm in certain patients[26].

In SAH, routine use of desmopressin is not standard practice. However, it may be considered in patients receiving antiplatelet agents prior to aneurysmal rupture or endovascular procedures. In such cases, a single dose of desmopressin may be administered to support haemostasis in preparation for surgical or procedural intervention[27].

Clinical guidelines from organizations such as the Neurocritical Care Society support the administration of a single intravenous dose of 0.4 µg/kg desmopressin in patients with ICH who are on antiplatelet therapy, particularly when emergency neurosurgical intervention is anticipated. This approach was supported by observational studies and early-phase trials demonstrating desmopressin's feasibility and relative safety in this setting[24].

In contrast, the 2022 AHA/ASA guidelines on spontaneous ICH do not recommend routine desmopressin use for patients not undergoing surgery, citing limited evidence of clinical benefit and a potential increase in adverse neurological outcomes. Similarly, platelet transfusions are discouraged unless required for emergent neurosurgical procedures[28].

From a practical standpoint, desmopressin should be administered as early as possible in ICH cases where antiplatelet use is suspected or confirmed. Repeat dosing is not recommended due to diminishing returns and the potential for hyponatremia.

In conclusion, the optimal dosing, timing, and patient selection criteria for desmopressin administration in antiplatelet-associated intracranial haemorrhage remain areas of the ongoing investigation. While concerns exist regarding potential thrombotic complications, the acute reversal of antiplatelet effects in the context of life-threatening intracranial haemorrhage generally presents a favourable risk-benefit profile in appropriately selected patients. It is suggested that, pending more robust clinical trials, the use of DDAVP in ICH patients should be considered on a case-by-case basis, weighing potential benefits against the risk of adverse neurological effects.

Bleeding in patients with liver disease: Patients with acute or chronic liver disease frequently exhibit complex and multifactorial coagulopathies arising from impaired hepatic synthesis of coagulation factors, thrombocytopenia, qualitative platelet dysfunction, and dysregulated fibrinolysis. Many patients maintain a precariously rebalanced haemostatic state despite prolonged conventional coagulation parameters such as elevated international normalized ratio (INR) or activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). This equilibrium is highly susceptible to disruption, particularly during invasive procedures or episodes of acute hepatic decompensation[29].

Prolonged bleeding time in patients with cirrhosis reflects a combination of quantitative and qualitative platelet abnormalities, reduced coagulation factor levels, and altered endothelial function[30]. DDAVP, through its capacity to stimulate the endothelial release of vWF and factor VIII, has been proposed as a potential therapeutic agent in this setting[30]. A seminal study by Burroughs et al[31] demonstrated that desmopressin administration in patients with chronic liver disease significantly elevated plasma vWF and factor VIII concentrations, alongside increased ristocetin cofactor activity. Additionally, randomised controlled trial in cirrhotic patients found a significant reduction in bleeding time following intravenous desmopressin, supporting its transient haemostatic efficacy[32]. In a double-blinded, placebo-controlled crossover study, subcutaneous desmopressin (0.3 µg/kg) significantly shortened bleeding time within one hour, although this effect diminished after four hours, suggesting a limited duration of action compared to intravenous infusion[33].

In procedural settings, such as liver biopsy, endoscopic variceal ligation, or surgery, desmopressin has been investigated as a prophylactic haemostatic agent. However, the evidence remains inconclusive. A multicentre, double-blinded trial conducted by the New Italian Endoscopic Club evaluated desmopressin in combination with terlipressin vs terlipressin alone in cirrhotic patients with acute variceal bleeding. The addition of desmopressin conferred no additional benefit, reinforcing the limited utility of DDAVP in this context[34]. Furthermore, a randomized controlled trial by Arshad et al[35] reported no significant improvement in primary haemostasis with desmopressin in cirrhotic patients, thereby questioning its routine peri-procedural use. In contrast, a clinical study demonstrated that intranasal desmo

The standard dose of desmopressin is 0.3 µg/kg administered intravenously over 15-30 minutes, with peak clinical effects observed within 30-60 minutes and lasting up to 6 hours.

Importantly, bleeding complications in cirrhosis are often multifactorial, dominated by portal hypertension, hypersplenism-induced thrombocytopenia, and synthetic dysfunction rather than primary defects in platelet adhesion[29]. Many cirrhotic patients paradoxically have elevated baseline levels of vWF and factor VIII, which diminishes the pharmacologic rationale for exogenous stimulation via desmopressin. Consequently, its use should only be considered in select patients with documented qualitative platelet dysfunction or in specific procedural scenarios.

In summary, while desmopressin may confer haemostatic benefit in a subset of patients with liver disease, current evidence does not support its routine use. Its role should be individualized, informed by the underlying patho

Preoperative haemostatic optimization and blood-sparing strategies: Desmopressin has been proposed as a perioperative haemostatic adjunct due to its ability to increase circulating levels of vWF and factor VIII, thereby enhancing platelet adhesion and aggregation[37]. This pharmacologic profile has prompted investigations into its potential as a blood-sparing agent in various surgical settings, particularly among patients with increased bleeding risk or those receiving antiplatelet therapy[38].

Initial enthusiasm stemming from early trials suggesting a significant reduction (approximately 30%) in bleeding and transfusion with desmopressin during cardiopulmonary bypass has not been consistently replicated[39]. While a meta-analysis indicated a modest average reduction of 9% in postoperative blood loss, with a more pronounced effect (up to 34%) in complex cardiac cases, the reduction in blood transfusion requirements did not reach statistical significance[40]. Notably, studies suggest a potential benefit in reducing perioperative bleeding in cardiac surgery patients on aspirin or clopidogrel, with one meta-analysis reporting a mean reduction of 0.5 units of packed red blood cells transfused intraoperatively[41]. However, the overall clinical utility of desmopressin in routine cardiac surgical practice remains questionable[40].

In procedures like total hip or knee arthroplasty, where mechanical bleeding often predominates, desmopressin has not demonstrated a clinically meaningful reduction in transfusion requirements[42].

Beyond the aforementioned settings, evidence supporting the use of desmopressin as a routine blood-sparing agent in non-cardiac surgeries in patients without underlying bleeding disorders is lacking. Broader literature reviews have similarly failed to demonstrate a significant benefit in reducing intraoperative blood loss or transfusion needs in the general surgical population[37,43,44].

Thus, the current evidence does not support the routine perioperative use of desmopressin as a blood-sparing agent across all surgical specialties. While it may have a role in highly selected cases, such as complex cardiac surgery in patients receiving antiplatelet therapy or in situations where qualitative platelet dysfunction is suspected, a careful assessment of individual patient risk, procedural bleeding potential, and the risk of adverse effects, particularly hyponatremia, is crucial[39,44]. Importantly, desmopressin holds a unique and indispensable role in the perioperative management of patients who refuse blood transfusions, such as Jehovah’s Witnesses[45]. In this population, where blood product use is not an option, DDAVP can provide a non-transfusional strategy to enhance endogenous haemostasis. Further large-scale, high-quality trials are warranted to more precisely define the role of desmopressin in specific surgical populations.

Haemophilia, vWD and Factor XI (FXI) deficiency: Haemophilia A is an X-linked recessive disorder characterized by a deficiency in FVIII, a critical component of the intrinsic coagulation pathway. It may present as a congenital or acquired condition, with congenital cases being significantly more common. The clinical severity correlates with residual FVIII activity: Mild (> 5%-< 40%), moderate (1%-5%), and severe (< 1%). DDAVP is an established therapeutic option in patients with mild haemophilia A, particularly during bleeding episodes or for prophylaxis in minor surgical procedures[46-49]. Its mechanism of action involves stimulating the release of FVIII and vWF from endothelial storage sites. Since its first documented use in 1977, DDAVP has consistently demonstrated efficacy in increasing FVIII levels and controlling mild bleeding in responsive patients[46].

Both intravenous and intranasal formulations are effective, with the latter offering the advantage of home administration (Table 4). In a large multicentre study of 333 patients with mild haemophilia A or vWD, DDAVP demonstrated over 90% efficacy across bleeding events, surgical interventions, and prophylactic scenarios[50]. A trial dose is recom

| Bleeding disorder | Indication | Utility |

| Mild congenital haemophilia A | Surgery, acute bleeding | Strong evidence; test dose recommended |

| Acquired haemophilia A | Minor bleeding, low inhibitor titres | Conditional use if FVIII > 5 IU/dL and inhibitor < 5 BU |

| Haemophilia B | Any bleeding | Not effective |

| Factor XI deficiency | Surgical prophylaxis, minor bleeding | Limited evidence; consider if response documented |

| Type 1 vWD | Surgical prophylaxis, mucosal bleeding | First-line agent; strong response in approximately 80% of patients |

| Type 2A vWD | Minor bleeding | Variable benefit; not preferred |

| Type 2B vWD | Any bleeding | Contraindicated - risk of thrombocytopenia |

| Type 2M/2N vWD | Minor bleeding | Limited or case-level evidence |

| Type 3 vWD | Any bleeding | Not effective – no vWF stores to mobilize |

Acquired haemophilia A is a rare autoimmune bleeding disorder caused by the development of neutralizing antibodies (inhibitors) against FVIII. It predominantly affects older adults and may occur spontaneously or in association with malignancy, autoimmune diseases, or pregnancy[1]. Patients often present with spontaneous bleeding and an isolated prolonged aPTT that does not correct with mixing studies.

Management involves controlling bleeding and suppressing inhibitor production. Bypassing agents like recombinant activated Factor VII or activated prothrombin complex concentrate are standard treatments. However, desmopressin may be beneficial in cases of low inhibitor titres (< 2-5 Bethesda Units) and residual FVIII activity > 5 IU/dL[52]. Clinical reports have shown that DDAVP can increase FVIII levels significantly and achieve haemostasis in minor bleeding episodes[53]. While not a first-line agent, DDAVP may be considered in select cases or resource-limited settings (Table 4).

Haemophilia B results from a deficiency of Factor IX and does not benefit from desmopressin therapy, as Factor IX is not stored in endothelial cells and cannot be mobilized by DDAVP[54]. Consequently, desmopressin has no therapeutic role in this disorder (Table 4).

vWD is the most prevalent inherited bleeding disorder and results from quantitative or qualitative defects in vWF[7]. It is classified into: Type 1: Partial quantitative deficiency; Type 2A/2B/2M/2N: Qualitative abnormalities; Type 3: Complete deficiency of vWF;

Desmopressin is considered first-line treatment in type 1 vWD, where endogenous vWF is reduced but functional (Table 3 and 4). It can significantly increase plasma vWF and FVIII levels, improving haemostasis during mucosal bleeding or minor surgical procedures. Most responders achieve a two to threefold increase in vWF within one hour, with sustained levels for 4-6 hours[55-58]. In critically ill patients, intravenous administration is preferred for reliable absorption and rapid onset during major bleeding episodes, such as gastrointestinal or CNS haemorrhage.

Factor XI (FXI) deficiency is a rare bleeding disorder with variable clinical presentation. While bleeding is often surgical or trauma-related, spontaneous haemorrhage is uncommon. Some reports suggest desmopressin may transiently elevate FXI levels, possibly via release from internal pools, though the precise mechanism remains unclear[59-61]. DDAVP may be considered for minor procedures in mild FXI deficiency if a test dose shows a measurable effect, but it should not replace FXI concentrate or antifibrinolytics in high-risk or major bleeding settings.

Central diabetes insipidus: Central diabetes insipidus (CDI), also known as neurogenic diabetes insipidus, is characterized by deficient secretion of AVP, leading to impaired renal water reabsorption. This hormonal deficiency causes excessive production of dilute urine, potentially resulting in dehydration and hypernatremia when fluid losses exceed intake[1,4]. In intensive care settings, CDI frequently develops secondary to neurological or neurosurgical conditions, including pituitary or hypothalamic surgery, traumatic brain injury, subarachnoid haemorrhage, or brain death. Clinically, patients exhibit polyuria (often exceeding 3-3.5 Liters/day), low urine osmolality (< 300 mOsm/kg), increasing serum sodium levels, and signs of volume depletion[62].

Desmopressin is the treatment of choice for managing CDI. As a synthetic analog of vasopressin with selective activity on renal V2 receptors, it facilitates water retention by promoting aquaporin channel insertion in the renal collecting ducts. This mechanism helps reduce urinary losses and correct hypernatremia[4,63,64]. In organ donor management, desmopressin is frequently used to stabilize haemodynamics and electrolyte levels, improving the quality and viability of transplantable organs.

It is essential to differentiate CDI from other causes of polyuria in the ICU, such as osmotic diuresis from hyperglycaemia or high-volume fluid administration. When the diagnosis is unclear, a diagnostic desmopressin challenge or measurement of AVP levels may help distinguish true CDI from other polyureic states.

In critically ill patients, IV or SC administration is preferred for rapid onset and reliable effect, particularly when oral or intranasal routes are impractical due to sedation or intubation[65]. A typical starting dose is 1-2 µg IV or IM, with the clinical response evaluated over 1-2 hours. Maintenance dosing typically ranges from 1-4 µg daily, divided into one or two administrations (e.g., 2 µg every 12 hours), and is titrated based on urine output and serum sodium levels (Table 3). Some centres may begin with lower doses (e.g., 0.5 µg IV) when partial DI is suspected to reduce the risk of iatrogenic hyponatremia due to overcorrection.

Managing CDI effectively in the ICU requires vigilant monitoring of fluid status, urine output, and electrolyte trends. Initial monitoring should include hourly urine volumes and urine specific gravity, with serum sodium levels assessed every 4-6 hours following desmopressin initiation[1,65].

In conscious patients with intact thirst mechanisms, oral fluid intake in combination with desmopressin often suffices. However, for sedated or unconscious patients, IV fluid therapy must be carefully adjusted to maintain fluid-electrolyte balance. The primary aim is to avoid both dehydration and water overload.

When serum sodium falls below the target range (typically 140-145 mmol/L), clinicians should consider withholding or reducing desmopressin and limiting hypotonic fluid intake. Conversely, persistent polyuria and hypernatremia may warrant increasing the dose or frequency of desmopressin (e.g., every 8 hours rather than every 12 hours).

A reduction in urine output indicates the effectiveness of desmopressin, increased urine osmolality (usually > 600 mOsm/kg), and stabilization of serum sodium within the normal range. Restoring water balance in neurocritical ill patients is crucial to prevent complications such as hypovolemia, hypotension, and further neurologic injury from hyperosmolar states.

Hyponatremia management: In addition to its established role in haemostasis, DDAVP has proven to be a valuable adjunct in the management of severe hyponatremia, particularly for mitigating the risk of osmotic demyelination syndrome (ODS). In the setting of chronic or profound hyponatremia, the brain undergoes adaptive loss of intracellular osmolytes to maintain osmotic equilibrium. A rapid increase in serum sodium—commonly defined as a rise exceeding 8 to 10 mmol/L within 24 hours—can disrupt this balance, leading to demyelinating injury, especially in high-risk populations such as those with alcoholism, liver disease, or malnutrition[66].

To address this, clinical guidelines emphasize the importance of controlled correction rates and close biochemical monitoring[67]. Observational data suggest that desmopressin use correlates with reduced urine output and increased urine osmolality, improving stability in sodium correction. In a propensity-matched cohort study, intranasal DDAVP was associated with safer correction of severe hyponatremia than conventional therapy[68]. Desmopressin is employed in two main therapeutic strategies: Reactive administration to arrest overcorrection once it begins, and prophylactic use to pre-empt large water diuresis that may accelerate sodium shifts.

In reactive use of DDAVP ("Rescue" strategy), desmopressin is administered when a patient’s serum sodium begins to rise more quickly than intended—often due to a sudden onset of aquaresis and dilute urine output. By stimulating V2 receptors in the renal collecting ducts, DDAVP promotes water reabsorption and suppresses free water excretion. This effect effectively "halts" ongoing sodium correction and allows clinicians to counterbalance the sodium rise with administration of hypotonic fluids, such as intravenous dextrose water[69].

For example, in a scenario where serum sodium increases from 112 to 125 mmol/L in under 12 hours, a 2 µg intravenous dose of desmopressin, combined with a calculated infusion of D5W, can help reverse and stabilize the correction. Both European and North American hyponatremia guidelines support this rescue strategy to mitigate ODS risk when sodium exceeds correction targets.

The proactive use of DDAVP ("DDAVP Clamp" strategy) involves scheduled administration of desmopressin (typically 1-2 µg IV or SC every 6-8 hours) at the onset of treatment for severe hyponatremia. This technique prevents spontaneous water diuresis by maintaining a steady antidiuretic state. It allows clinicians to control serum sodium rise tightly using tailored hypertonic saline dosing while eliminating fluctuations caused by renal free water clearance[69].

This strategy is especially indicated in patients at high risk for ODS—those with serum sodium < 105 mmol/L or underlying conditions such as cirrhosis, hypokalemia, or malnutrition. Serum sodium is measured every 2-4 hours during correction, with desmopressin continued until levels stabilize above 125 mmol/L. This method has shown efficacy in safely achieving correction targets, minimizing the likelihood of overshooting.

A growing body of literature supports the safety and effectiveness of both proactive and reactive desmopressin strategies. A randomized controlled trial comparing these approaches found no significant difference in overcorrection rates, reinforcing the clinical utility of DDAVP in either context when supported by close monitoring. Notably, no cases of ODS were reported in the study, highlighting the protective role of DDAVP against rapid osmotic shifts[70].

A typical regimen involves 1-2 µg IV or SC every 6-8 hours, corresponding to approximately 0.01-0.02 µg/kg. Treat

Tight control of fluid intake is essential during DDAVP therapy to avoid dilutional hyponatremia (Table 5). Administration of free water without concurrent DDAVP or monitoring can worsen hyponatremia. In this context, DDAVP essentially mimics a state of SIADH, temporarily suppressing renal water clearance to permit controlled sodium correction.

| Effect | How it happens | Clinical impact |

| Lowers sodium levels (hyponatremia risk) | Retains water, diluting sodium | Risk of dilutional hyponatremia if fluid intake is not controlled |

| Stabilizes sodium correction in SIADH | Slows rapid sodium rise by promoting water retention | Prevents osmotic demyelination syndrome |

| Does not directly alter sodium excretion | Primarily affects water balance, not sodium transport | Sodium levels change due to dilution effects |

Desmopressin has become an integral part of contemporary hyponatremia management protocols. Whether initiated prophylactically or in response to rapid sodium shifts, it offers a reliable means to arrest or slow correction. Its rapid onset, predictable duration, and well-characterized safety profile render it especially useful in critical care and perioperative settings. Success in applying DDAVP hinges on frequent biochemical monitoring and multidisciplinary coordination to prevent inadvertent fluid or electrolyte disturbances. Moreover, few reports indicate that desmopressin may lengthen the duration of hypertonic saline therapy without significantly altering ICU stay or overcorrection frequency, indicating that its broader benefits warrant further randomized evaluation[71].

Renal colic: Renal colic, characterized by acute and severe flank pain due to ureteric obstruction, often necessitates prompt and adequate analgesia. Desmopressin, a synthetic vasopressin analogue with antidiuretic properties, has emerged as a promising adjunct in this setting. Its primary mechanism in renal colic involves reducing urine output via V2 receptor activation, thereby lowering intrapelvic pressure and ureteral distension—key contributors to pain[72].

Clinical studies have demonstrated that intranasal or sublingual desmopressin can provide rapid analgesic relief, either alone or when used in combination with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or opioids[73,74]. Its non-invasive ad

The optimal dose and route of desmopressin for renal colic remain areas of ongoing investigation. Existing studies suggest potential analgesic benefits with various formulations; however, standardized dosing strategies are yet to be established[72].

Intranasal Route: A dose of 40 µg intranasally has been frequently used in clinical studies. This route offers rapid mucosal absorption and early onset of action, making it particularly useful in emergency settings for acute pain management.

Sublingual Route: Sublingual desmopressin has been administered in variable doses, adjusted based on clinical response and practitioner discretion. Its ease of use and non-invasive nature make it a practical option, especially in outpatient or resource-limited contexts.

Oral route: Although not routinely employed in renal colic, oral oro-dispersible formulations (60-120 µg) have been proposed as potentially effective. However, the current evidence base is limited, and further high-quality randomized trials are needed to validate the efficacy, safety, and ideal dosing of oral desmopressin in this setting.

The route and dose should be individualized in all cases, considering the patient's clinical status, comorbidities, and the setting where treatment is administered.

Hyponatremia represents one of the most significant adverse effects associated with desmopressin therapy in the ICU. The reported incidence of clinically significant hyponatremia (defined as serum sodium < 130 mmol/L) ranges from 7%-11% following desmopressin administration[75]. While hyponatremia is often asymptomatic, severe cases can lead to significant morbidity and potentially life-threatening complications.

A case report described a 60-year-old man who received desmopressin 60 μg orally as prophylaxis before a per

Several risk factors have been identified for desmopressin-induced hyponatremia, including[78]: Pre-existing low serum sodium levels; Impaired renal function (reduced eGFR); Elevated spot urine sodium; Unrestricted fluid intake during therapy; Advanced age; Use of psychotropic agents, thiazide diuretics, and anticancer drugs.

There is a rare but potential risk of arterial or venous thrombosis after desmopressin use, especially in patients with von Willebrand's disease or haemophilia A receiving factor VIII/VWF concentrates. Such patients may be at risk for clot formation[78,79]. Paradoxical thrombocytopenia may also be observed in patients with type 2B vWD[80]. In these cases, desmopressin should be avoided due to the risk of exacerbating thrombocytopenia and promoting further thrombotic events.

Given the potentially severe complications, proactive monitoring is essential in all critically ill patients receiving desmopressin. Recommended clinical surveillance includes:

Serum sodium: Measure at baseline, then recheck at 4-6 hours and 12 hours post-administration.

Coagulation parameters: Assess vWF: RCo and FVIII: C at 60-90 minutes if used for haemostatic effect. If vWF: RCo and FVIII: C are unavailable or delayed, the PFA-100/200 is a practical surrogate to assess desmopressin-induced haemostatic effect, especially in platelet dysfunction or mild vWD. Meanwhile, aPTT, thromboelastography, and clinical bleeding control remain useful adjuncts in critical care. Fluid balance and urine output: Track closely for 12-24 hours, especially in patients with AKI, elderly individuals, or those receiving repeated doses.

Desmopressin, while effective for both haemostatic and antidiuretic purposes, must be used with caution in critically ill patients due to its potential to cause serious complications such as hyponatremia, volume overload, or thrombotic events.

Pre-existing hyponatremia or risk of water retention: Desmopressin enhances free water reabsorption by stimulating V2 receptors in the renal collecting ducts, significantly increasing the risk of dilutional hyponatremia. This is particularly dangerous in patients with baseline low serum sodium or unrestricted fluid intake, potentially leading to seizures or cerebral edema.

Type IIB vWD: In this subtype, desmopressin exacerbates thrombocytopenia by releasing abnormal vWF multimers that promote platelet aggregation and clearance, worsening the bleeding risk. Thus, it is contraindicated in these patients.

Known hypersensitivity: Desmopressin is contraindicated in individuals with documented hypersensitivity to the drug or its excipients.

Cardiovascular disease: Patients with recent myocardial infarction, unstable angina, or advanced atherosclerosis may be at increased thrombotic risk due to DDAVP-induced elevations in vWF and factor VIII, despite the drug’s minimal vasopressor activity.

Renal impairment: As desmopressin is eliminated via the kidneys, impaired renal function can prolong its half-life and amplify the risk of water retention, hyponatremia, and delayed adverse effects.

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion: Because desmopressin mimics endogenous vasopressin activity, it may aggravate fluid overload and electrolyte imbalances in SIADH patients.

Heart failure and advanced cirrhosis: In conditions associated with baseline volume overload or impaired sodium handling, such as congestive heart failure or decompensated cirrhosis, DDAVP may precipitate worsening edema, ascites, or hyponatremia.

Agents potentiating antidiuretic effects: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g., fluoxetine, sertraline) can enhance desmopressin-induced water retention by promoting ADH activity or inducing SIADH, raising the risk of hyponatremia.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs inhibit renal prostaglandin synthesis, which antagonizes ADH. When combined with desmopressin, this potentiates antidiuretic effects, increasing the risk of water intoxication.

Carbamazepine and chlorpropamide: Both drugs sensitize renal tubules to ADH or enhance water reabsorption, magnifying desmopressin’s effects and elevating the risk of dilutional hyponatremia.

Other antidiuretic agents (e.g., Vasopressin, Oxytocin): Concurrent use may produce additive or unpredictable antidiuretic effects, compounding the risk of volume overload and electrolyte derangements.

Agents influencing haemostasis: Antiplatelet agents (e.g., Aspirin, Clopidogrel). Desmopressin is often used to counteract antiplatelet-related bleeding. However, its effectiveness can be variable and is dependent on timing and platelet receptor function. Functional platelet testing (e.g., aggregometry, thromboelastography) is advisable when co-administered.

Anticoagulants (e.g., Heparin, Warfarin, DOACs): Desmopressin does not reverse anticoagulant activity. It may provide adjunctive haemostatic benefit in mixed coagulopathies but should not replace standard reversal agents when clinically indicated.

Renal clearance interactions: Although desmopressin is not metabolized by hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes, its renal elimination makes it susceptible to interactions with nephrotoxic or nephro-modulating agents (e.g., aminoglycosides, calcineurin inhibitors). These agents may impair DDAVP clearance, enhancing the risk of adverse effects such as prolonged antidiuresis and hyponatremia.

Thus, when considering desmopressin in the ICU, clinicians must carefully evaluate the individual’s volume status, sodium balance, renal function, and concurrent medications. A structured risk-benefit analysis, close electrolyte monitoring, and consideration of drug interactions are essential to avoid complications.

Desmopressin’s future in critical care is shifting from broad applications to a more personalized, precision-based approach. Emerging strategies focus on optimizing patient selection, improving safety, and enhancing efficacy across diverse clinical scenarios.

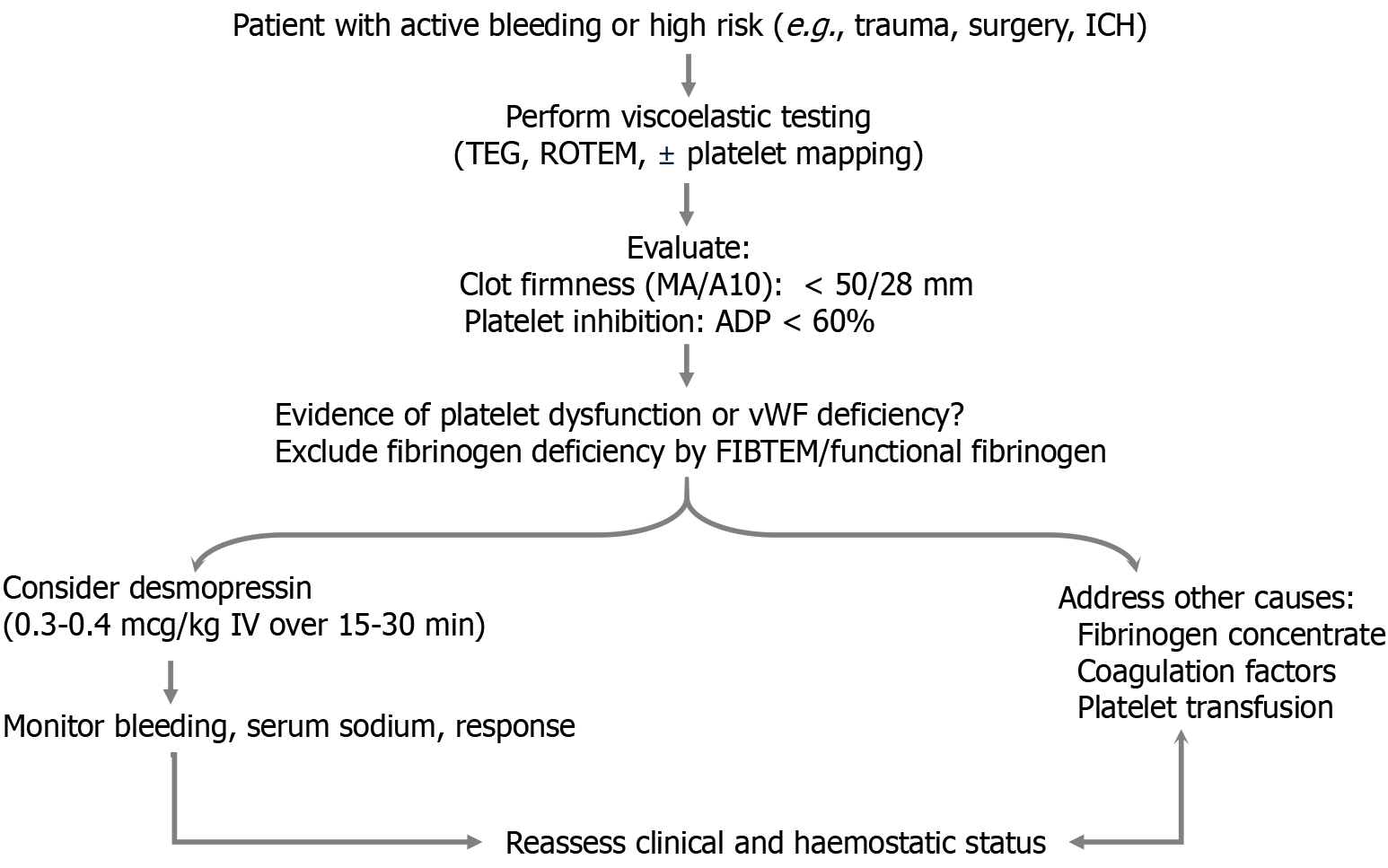

Point-of-care tests like thromboelastography, rotational thromboelastometry, and platelet function analysers enable individualized haemostatic assessment. Desmopressin can be integrated into goal-directed protocols for patients showing platelet dysfunction or prolonged closure times, particularly in trauma, surgery, or antiplatelet-related bleeding[80-83] (Figure 2).

Combining DDAVP with agents like tranexamic acid or platelet transfusions may enhance outcomes in bleeding patients[84]. Sequential or multimodal approaches are being explored, particularly for patients with complex coagulopathies.

The next frontier in desmopressin therapy lies in designing analogues that selectively enhance haemostatic activity while minimizing antidiuretic effects. This innovation could significantly reduce the risk of hyponatremia, particularly in critically ill patients. Additionally, emerging technologies such as sustained-release systems and nanoparticle-based delivery platforms can prolong therapeutic action, minimize dosing frequency, and improve safety. These advances may pave the way for more precise, effective, and individualized use of desmopressin in both haemostatic and endocrine applications.

Although desmopressin is widely used for its hemostatic benefits, its optimal role remains to be defined through direct comparative studies. Desmopressin is considerably more cost-effective and logistically simpler to administer than recombinant or plasma-derived vWF concentrates and carries fewer transfusion-related risks than cryoprecipitate, particularly in critically ill or volume-restricted patients. However, its transient effect and limited utility in major hemorrhage highlight the need for caution. Future research should focus on head-to-head trials assessing efficacy, safety, and cost across diverse clinical settings to guide personalized and evidence-based use of desmopressin in critical care.

Desmopressin is a valuable dual-purpose agent in critical care, serving as a haemostatic adjunct and a hormone replacement for central diabetes insipidus. Its ability to enhance vWF and factor VIII release effectively treats bleeding associated with platelet dysfunction, uraemia, vWD, and antiplatelet therapy. At lower doses, it safely restores water balance in neurogenic DI. While evidence supports improving surrogate outcomes like bleeding time and transfusion reduction, its impact on long-term clinical outcomes remains under investigation. The main safety concern—hypona

| 1. | Mohinani A, Patel S, Tan V, Kartika T, Olson S, DeLoughery TG, Shatzel J. Desmopressin as a hemostatic and blood sparing agent in bleeding disorders. Eur J Haematol. 2023;110:470-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Summers A, Singh J, Lai M, Schomer KJ, Martin R, Vitt JR, Derry KL, Box K, Chu F, Arias V, Minokadeh A, Stern-Nezer S, Groysman L, Lee BJ, Atallah S. A multicenter retrospective study evaluating the impact of desmopressin on hematoma expansion in patients with antiplatelet-associated intracranial hemorrhage. Thromb Res. 2023;222:96-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Desborough MJR, Al-Shahi Salman R, Stanworth SJ, Havard D, Woodhouse LJ, Craig J, Krishnan K, Brennan PM, Dineen RA, Coats TJ, Hepburn T, Bath PM, Sprigg N; DASH trial investigators. Desmopressin for patients with spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage taking antiplatelet drugs (DASH): a UK-based, phase 2, randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre feasibility trial. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22:557-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Baldeweg SE, Ball S, Brooke A, Gleeson HK, Levy MJ, Prentice M, Wass J; Society for Endocrinology Clinical Committee. SOCIETY FOR ENDOCRINOLOGY CLINICAL GUIDANCE: Inpatient management of cranial diabetes insipidus. Endocr Connect. 2018;7:G8-G11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Agersø H, Seiding Larsen L, Riis A, Lövgren U, Karlsson MO, Senderovitz T. Pharmacokinetics and renal excretion of desmopressin after intravenous administration to healthy subjects and renally impaired patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;58:352-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Glavaš M, Gitlin-Domagalska A, Dębowski D, Ptaszyńska N, Łęgowska A, Rolka K. Vasopressin and Its Analogues: From Natural Hormones to Multitasking Peptides. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:3068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ozgönenel B, Rajpurkar M, Lusher JM. How do you treat bleeding disorders with desmopressin? Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:159-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Slusarz MJ, Slusarz R, Ciarkowski J. Investigation of mechanism of desmopressin binding in vasopressin V2 receptor versus vasopressin V1a and oxytocin receptors: molecular dynamics simulation of the agonist-bound state in the membrane-aqueous system. Biopolymers. 2006;81:321-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Colucci G, Stutz M, Rochat S, Conte T, Pavicic M, Reusser M, Giabbani E, Huynh A, Thürlemann C, Keller P, Alberio L. The effect of desmopressin on platelet function: a selective enhancement of procoagulant COAT platelets in patients with primary platelet function defects. Blood. 2014;123:1905-1916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sica DA, Gehr TW. Desmopressin : safety considerations in patients with chronic renal disease. Drug Saf. 2006;29:553-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Köhler M, Hellstern P, Tarrach H, Bambauer R, Wenzel E, Jutzler GA. Subcutaneous injection of desmopressin (DDAVP): evaluation of a new, more concentrated preparation. Haemostasis. 1989;19:38-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kaw D, Malhotra D. Platelet dysfunction and end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2006;19:317-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mannucci PM, Remuzzi G, Pusineri F, Lombardi R, Valsecchi C, Mecca G, Zimmerman TS. Deamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin shortens the bleeding time in uremia. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:8-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 484] [Cited by in RCA: 375] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Watson AJ, Keogh JA. Effect of 1-deamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin on the prolonged bleeding time in chronic renal failure. Nephron. 1982;32:49-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim JH, Baek CH, Min JY, Kim JS, Kim SB, Kim H. Desmopressin improves platelet function in uremic patients taking antiplatelet agents who require emergent invasive procedures. Ann Hematol. 2015;94:1457-1461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lee HK, Kim YJ, Jeong JU, Park JS, Chi HS, Kim SB. Desmopressin improves platelet dysfunction measured by in vitro closure time in uremic patients. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;114:c248-c252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ho SJ, Gemmell R, Brighton TA. Platelet function testing in uraemic patients. Hematology. 2008;13:49-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Qiu Z, Pang X, Xiang Q, Cui Y. The Crosstalk between Nephropathy and Coagulation Disorder: Pathogenesis, Treatment, and Dilemmas. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023;34:1793-1811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Malve H, Goswami P, Asalkar A, More D. Role of Desmopressin in Bleeding Disorders: What Indian Physicians Need to Know? J Assoc Physicians India. 2025;73:58-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Barletta JF, Abdul-Rahman D, Hall ST, Mangram AJ, Dzandu JK, Frontera JA, Zach V. The Role of Desmopressin on Hematoma Expansion in Patients with Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Prescribed Pre-injury Antiplatelet Medications. Neurocrit Care. 2020;33:405-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Spahn DR, Bouillon B, Cerny V, Duranteau J, Filipescu D, Hunt BJ, Komadina R, Maegele M, Nardi G, Riddez L, Samama CM, Vincent JL, Rossaint R. The European guideline on management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma: fifth edition. Crit Care. 2019;23:98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 890] [Cited by in RCA: 797] [Article Influence: 113.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rossaint R, Afshari A, Bouillon B, Cerny V, Cimpoesu D, Curry N, Duranteau J, Filipescu D, Grottke O, Grønlykke L, Harrois A, Hunt BJ, Kaserer A, Komadina R, Madsen MH, Maegele M, Mora L, Riddez L, Romero CS, Samama CM, Vincent JL, Wiberg S, Spahn DR. The European guideline on management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma: sixth edition. Crit Care. 2023;27:80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 515] [Cited by in RCA: 377] [Article Influence: 125.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (20)] |

| 23. | Andersen LK, Hvas AM, Hvas CL. Effect of Desmopressin on Platelet Dysfunction During Antiplatelet Therapy: A Systematic Review. Neurocrit Care. 2021;34:1026-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Frontera JA, Lewin JJ 3rd, Rabinstein AA, Aisiku IP, Alexandrov AW, Cook AM, del Zoppo GJ, Kumar MA, Peerschke EI, Stiefel MF, Teitelbaum JS, Wartenberg KE, Zerfoss CL. Guideline for Reversal of Antithrombotics in Intracranial Hemorrhage: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals from the Neurocritical Care Society and Society of Critical Care Medicine. Neurocrit Care. 2016;24:6-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in RCA: 492] [Article Influence: 44.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Baharoglu MI, Cordonnier C, Al-Shahi Salman R, de Gans K, Koopman MM, Brand A, Majoie CB, Beenen LF, Marquering HA, Vermeulen M, Nederkoorn PJ, de Haan RJ, Roos YB; PATCH Investigators. Platelet transfusion versus standard care after acute stroke due to spontaneous cerebral haemorrhage associated with antiplatelet therapy (PATCH): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;387:2605-2613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 476] [Cited by in RCA: 512] [Article Influence: 51.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Shahzad F, Ahmed U, Muhammad A, Shahzad F, Naufil SI, Sukkari MW, Kamran AB, Murtaza S, Khalid MB, Shabbir H, Saeed S. Safety and efficacy of desmopressin (DDAVP) in preventing hematoma expansion in intracranial hemorrhage associated with antiplatelet drugs use: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Brain Behav. 2024;14:e3540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Francoeur CL, Roh D, Schmidt JM, Mayer SA, Falo MC, Agarwal S, Connolly ES, Claassen J, Elkind MSV, Park S. Desmopressin administration and rebleeding in subarachnoid hemorrhage: analysis of an observational prospective database. J Neurosurg. 2019;130:502-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Greenberg SM, Ziai WC, Cordonnier C, Dowlatshahi D, Francis B, Goldstein JN, Hemphill JC 3rd, Johnson R, Keigher KM, Mack WJ, Mocco J, Newton EJ, Ruff IM, Sansing LH, Schulman S, Selim MH, Sheth KN, Sprigg N, Sunnerhagen KS; American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. 2022 Guideline for the Management of Patients With Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2022;53:e282-e361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1189] [Cited by in RCA: 907] [Article Influence: 226.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kataria S, Juneja D, Singh O. Approach to thromboelastography-based transfusion in cirrhosis: An alternative perspective on coagulation disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:1460-1474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mannucci PM, Vicente V, Vianello L, Cattaneo M, Alberca I, Coccato MP, Faioni E, Mari D. Controlled trial of desmopressin in liver cirrhosis and other conditions associated with a prolonged bleeding time. Blood. 1986;67:1148-1153. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Burroughs AK, Matthews K, Qadiri M, Thomas N, Kernoff P, Tuddenham E, McIntyre N. Desmopressin and bleeding time in patients with cirrhosis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;291:1377-1381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Agnelli G, Parise P, Levi M, Cosmi B, Nenci GG. Effects of desmopressin on hemostasis in patients with liver cirrhosis. Haemostasis. 1995;25:241-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Cattaneo M, Tenconi PM, Alberca I, Garcia VV, Mannucci PM. Subcutaneous desmopressin (DDAVP) shortens the prolonged bleeding time in patients with liver cirrhosis. Thromb Haemost. 1990;64:358-360. [PubMed] |

| 34. | de Franchis R, Arcidiacono PG, Carpinelli L, Andreoni B, Cestari L, Brunati S, Zambelli A, Battaglia G, Mannucci PM. Randomized controlled trial of desmopressin plus terlipressin vs. terlipressin alone for the treatment of acute variceal hemorrhage in cirrhotic patients: a multicenter, double-blind study. New Italian Endoscopic Club. Hepatology. 1993;18:1102-1107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 35. | 35 Arshad F, Stoof SC, Leebeek FW, Ruitenbeek K, Adelmeijer J, Blokzijl H, van den Berg AP, Porte RJ, Kruip MJ, Lisman T. Infusion of DDAVP does not improve primary hemostasis in patients with cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2015;35:1809-1815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Stanca CM, Montazem AH, Lawal A, Zhang JX, Schiano TD. Intranasal desmopressin versus blood transfusion in cirrhotic patients with coagulopathy undergoing dental extraction: a randomized controlled trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:138-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Wang C, Lebedeva V, Yang J, Anih J, Park LJ, Paczkowski F, Roshanov PS. Desmopressin to reduce periprocedural bleeding and transfusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Perioper Med (Lond). 2024;13:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 38. | Crescenzi G, Landoni G, Biondi-Zoccai G, Pappalardo F, Nuzzi M, Bignami E, Fochi O, Maj G, Calabrò MG, Ranucci M, Zangrillo A. Desmopressin reduces transfusion needs after surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:1063-1076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Salzman EW, Weinstein MJ, Weintraub RM, Ware JA, Thurer RL, Robertson L, Donovan A, Gaffney T, Bertele V, Troll J. Treatment with desmopressin acetate to reduce blood loss after cardiac surgery. A double-blind randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:1402-1406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 413] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Cattaneo M, Harris AS, Strömberg U, Mannucci PM. The effect of desmopressin on reducing blood loss in cardiac surgery--a meta-analysis of double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Thromb Haemost. 1995;74:1064-1070. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Desborough MJ, Oakland KA, Landoni G, Crivellari M, Doree C, Estcourt LJ, Stanworth SJ. Desmopressin for treatment of platelet dysfunction and reversal of antiplatelet agents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15:263-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Desborough MJ, Oakland K, Brierley C, Bennett S, Doree C, Trivella M, Hopewell S, Stanworth SJ, Estcourt LJ. Desmopressin use for minimising perioperative blood transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD001884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Lim CC, Siow B, Choo JCJ, Chawla M, Chin YM, Kee T, Lee PH, Foo M, Tan CS. Desmopressin for the prevention of bleeding in percutaneous kidney biopsy: efficacy and hyponatremia. Int Urol Nephrol. 2019;51:995-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Wong AY, Irwin MG, Hui TW, Fung SK, Fan ST, Ma ES. Desmopressin does not decrease blood loss and transfusion requirements in patients undergoing hepatectomy. Can J Anaesth. 2003;50:14-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 45. | Beholz S, Liu J, Thoelke R, Spiess C, Konertz W. Use of desmopressin and erythropoietin in an anaemic Jehovah's Witness patient with severely impaired coagulation capacity undergoing stentless aortic valve replacement. Perfusion. 2001;16:485-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Venkateswaran L, Wilimas JA, Jones DJ, Nuss R. Mild hemophilia in children: prevalence, complications, and treatment. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1998;20:32-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Rodeghiero F, Castaman G, Mannucci PM. Prospective multicenter study on subcutaneous concentrated desmopressin for home treatment of patients with von Willebrand disease and mild or moderate hemophilia A. Thromb Haemost. 1996;76:692-696. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Chistolini A, Dragoni F, Ferrari A, La Verde G, Arcieri R, Ege Mohamud A, Mazzucconi MG. Intranasal DDAVP: biological and clinical evaluation in mild factor VIII deficiency. Haemostasis. 1991;21:273-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Lethagen S. Desmopressin in mild hemophilia A: indications, limitations, efficacy, and safety. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2003;29:101-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Leissinger C, Becton D, Cornell C Jr, Cox Gill J. High-dose DDAVP intranasal spray (Stimate) for the prevention and treatment of bleeding in patients with mild haemophilia A, mild or moderate type 1 von Willebrand disease and symptomatic carriers of haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2001;7:258-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Castaman G, Mancuso ME, Giacomelli SH, Tosetto A, Santagostino E, Mannucci PM, Rodeghiero F. Molecular and phenotypic determinants of the response to desmopressin in adult patients with mild hemophilia A. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:1824-1831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Kruse-Jarres R, Kempton CL, Baudo F, Collins PW, Knoebl P, Leissinger CA, Tiede A, Kessler CM. Acquired hemophilia A: Updated review of evidence and treatment guidance. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:695-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Franchini M, Lippi G. The use of desmopressin in acquired haemophilia A: a systematic review. Blood Transfus. 2011;9:377-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Preijers T, Schütte LM, Kruip MJHA, Cnossen MH, Leebeek FWG, van Hest RM, Mathôt RAA. Strategies for Individualized Dosing of Clotting Factor Concentrates and Desmopressin in Hemophilia A and B. Ther Drug Monit. 2019;41:192-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Connell NT, Flood VH, Brignardello-Petersen R, Abdul-Kadir R, Arapshian A, Couper S, Grow JM, Kouides P, Laffan M, Lavin M, Leebeek FWG, O'Brien SH, Ozelo MC, Tosetto A, Weyand AC, James PD, Kalot MA, Husainat N, Mustafa RA. ASH ISTH NHF WFH 2021 guidelines on the management of von Willebrand disease. Blood Adv. 2021;5:301-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 51.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Rodeghiero F, Castaman G, Mannucci PM. Clinical indications for desmopressin (DDAVP) in congenital and acquired von Willebrand disease. Blood Rev. 1991;5:155-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Phua CW, Berntorp E. A personalized approach to the management of VWD. Transfus Apher Sci. 2019;58:590-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |