Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.108638

Revised: May 13, 2025

Accepted: May 29, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 223 Days and 18.2 Hours

Sepsis is a life-threatening condition caused by a dysregulated host response to infection. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) are critical mediators of the immune response and may exhibit redox imbalance during sepsis. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are known to influence immune cell signaling, and exces

To assess intracellular ROS levels in PBMC subsets from septic patients and determine whether norepinephrine (NE) or N-acetylcysteine (NAC) modulate ROS levels following inflammatory stimulation in vitro.

PBMCs were isolated from Department of Emergency patients meeting SEP-1/SEP-2 sepsis criteria and from healthy controls without signs of infection. Intracellular ROS levels were measured using a total ROS detection assay and analyzed by flow cytometry. PBMCs were also stimulated in vitro with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), with or without co-treatment with NE or NAC.

ROS levels were significantly elevated in CD3+ and CD14+ cells from septic patients compared to controls. In vitro stimulation of control PBMCs with LPS or H2O2 increased ROS in CD3+ and CD14+ cells, which was attenuated by co-treatment with NE or NAC.

ROS levels are elevated in specific PBMC subsets in sepsis, particularly CD3+ T cells and CD14+ monocytes. NE and NAC reduced ROS accumulation in vitro, supporting their potential role as redox modulators. These findings warrant further mechanistic investigation into immune redox regulation in sepsis.

Core Tip: Sepsis is a life-threatening condition characterized by immune dysregulation, in which peripheral blood mono

- Citation: Thoppil J, Farrar JD, Sharma D, Kirby S, Mobley A, Courtney DM. Reactive oxygen species elevations in human immune cell subsets during sepsis are mitigated by norepinephrine and N-acetylcysteine. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(4): 108638

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i4/108638.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.108638

Sepsis is life-threatening syndrome characterized by a dysregulated immune response to infection that leads to organ dysfunction and death, making it a leading cause of mortality worldwide[1]. This dysregulated immune response contributes to the hyperinflammatory, and immunosuppressive phases seen with sepsis[2]. Peripheral blood mono

A major driver of PBMC dysfunction is thought to be the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Under physiologic conditions, ROS functions as second messengers in immune cell signaling, are essential for T-cell receptor activation, cytokine secretion and microbial killing[4,5]. However, in sepsis, the balance between ROS production and antioxidant defenses are disrupted, resulting in oxidative stress that impairs immune function[6]. In T cells, supra

Norepinephrine (NE) is the first-line vasopressor used in septic shock management, primarily for its hemodynamic effects[13]. However, growing evidence suggests that NE also modulates immune responses via adrenergic receptors expressed on leukocytes. NE signaling through β2-adrenergic receptors on immune cells can inhibit the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IL-6, while enhancing anti-inflammatory mediators like IL-10[14-16]. In vitro studies have shown that NE suppresses T-helper (Th) 1 cytokine responses, impairs monocyte activation and alters the balance between pro and anti-inflammatory polarization[17]. Furthermore, NE may influence mitochondrial activity and ROS production, thereby affecting redox balance and immune cell function[13,18,19]. These findings position NE as a potential immunomodulatory agent in sepsis beyond its cardiovascular role.

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is a thiol-containing antioxidant that serves as a precursor to glutathione, a key intracellular antioxidant critical for redox homeostasis. NAC directly scavenges free radicals and replenishes glutathione stores, which are often depleted during oxidative stress and during sepsis[20]. In preclinical models of sepsis, NAC has been shown to attenuate pro-inflammatory cytokine production, reduce oxidative damage and improve survival outcomes[21-23]. Abimannan et al[24] suggested that the oxidative microenvironment can alter cytokine responses in Th17 and Th1 cells in response to sepsis and that NAC could potentially mitigate these effects. In clinical studies, NAC administration has been associated with improvements in SOFA scores, and enhanced tissue oxygenation and improved multiple organ failure[25,26]. However, results have been variable due to heterogeneity in timing dosing and patient populations[26]. Despite mixed clinical findings, NAC remains a candidate for adjunctive therapy aimed at mitigating immune dysfunction via redox regulation[21].

Although the importance of oxidative stress in sepsis is well-acknowledged, the specific role of ROS in modulating immune cell subset dysfunction remains insufficiently characterized. It is unclear how elevated ROS levels contribute to functional impairments in distinct PBMC populations—such as T cells and monocyte subsets—and how therapeutic agents like NE and NAC may restore immune homeostasis. We hypothesized that excessive ROS production contributes to immune dysregulation in sepsis and that modulating ROS through pharmacologic intervention may reverse immune cell dysfunction. Therefore, we analyzed ROS levels in PBMCs isolated from Department of Emergency patients with sepsis and investigated the effects of NE and NAC on ROS modulation using flow cytometry. Our findings demonstrate that specific PBMC subsets exhibit elevated ROS in sepsis, and both NE and NAC have the capacity to attenuate these ROS levels, supporting their potential as immunomodulatory agents in the treatment of sepsis.

Written informed consent was obtained from all adult donors under protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Peripheral blood was collected by venipuncture from patients enrolled prospectively in the Department of Emergency. Patients were assigned to either the sepsis or control cohort. Patients in the sepsis cohort met SEP-1/SEP-2 criteria, which require the presence of at least two systemic inflammatory response syndrome features in the setting of suspected infection. All septic patients had radiographic confirmation of pulmonary infiltrates consistent with pneumonia based on chest X-ray or computed tomography imaging. Although SEP-3 criteria offer a more specific definition based on organ dysfunction and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scoring, SEP-1/SEP-2 definitions were used due to the practical challenges of calculating SOFA scores in real time in the Department of Emergency. Control patients were healthy individuals presenting without vital sign abnormalities and without any symptoms or complaints concerning for active infection. Sex was not considered as a biological variable in this study. The control cohort consisted of 13 patients (6 male, 7 female) with a mean age of 45.6 years and a median age of 42 years. The sepsis cohort consisted of 12 patients (6 male, 6 female) with a mean age of 46.6 years and a median age of 50 years. Patients were excluded if they were under 18 years of age, pregnant, incarcerated, clinically unstable requiring emergent interventions, receiving chemotherapy or other immunosuppressive medications, or tested positive for respiratory viral pathogens. Stimulation studies were conducted using PBMCs from seven patients in the control cohort. All seven were used in NE stimulation experiments, and three were used in experiments with NAC. Unstimulated ROS experiments were performed with PBMCs from 6 control and 6 septic patients. Plasma for cytokine analysis was obtained from all 13 control and all 12 sepsis patients. All stimulation and analysis conditions were performed in biological duplicates.

Whole blood was diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and layered over Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare) for density gradient centrifugation at room temperature. Isolated PBMCs were stained with trypan blue to assess viability, counted, aliquoted and cryopreserved until future use. Upon thawing, PBMCs were washed in Roswell Park Memorial Institute media and plated at 1 × 106 cells per well in 24-well plates. Cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 1 hour in the presence of the Total ROS Detection Reagent from the Total ROS Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) to label intracellular ROS. PBMCs were then stimulated with 100 ng/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS)[14], 10 μM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)[27], 5 mM NE, 14 mM or 10 mM NAC[28]. Where applicable, combined stimulations (e.g., LPS + NE or H2O2 + NAC) were also performed. These concentrations were selected based on prior studies that demonstrated physiologically relevant immunomodulatory effects in vitro. Following 16 hours of incubation, 100 × monensin (eBioscience) was added for an additional 2 hours to inhibit cytokine secretion. Cell viability was assessed using trypan blue exclusion prior to stimulation. All experiments were performed in duplicate.

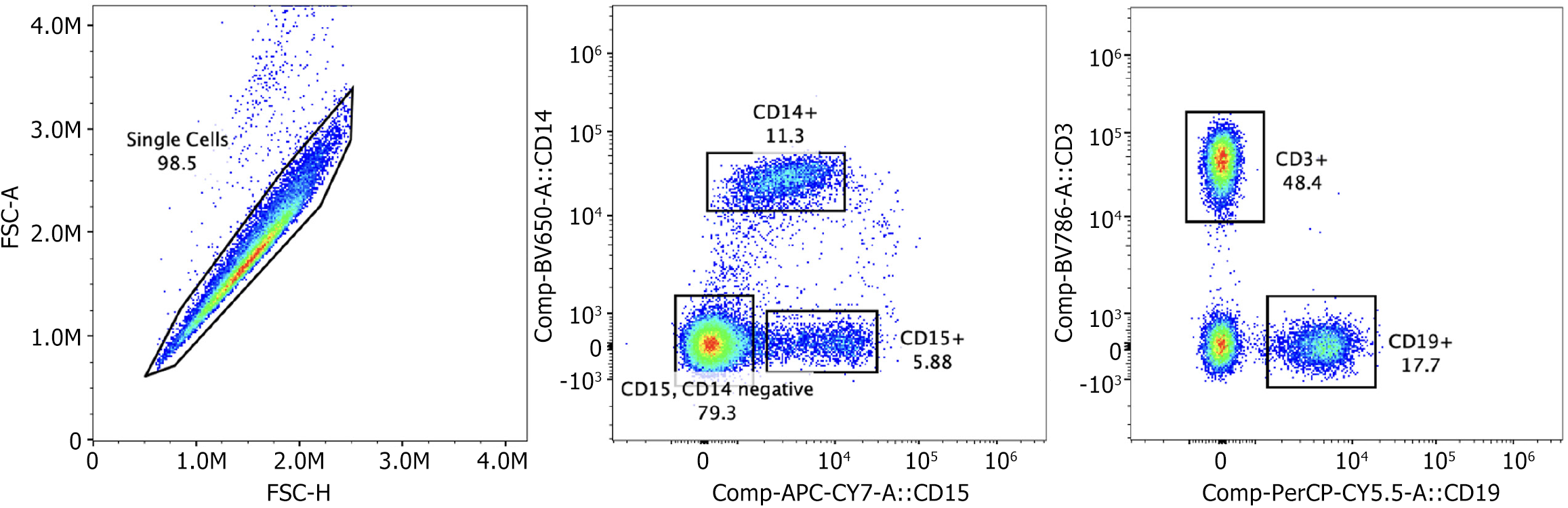

Following stimulation, cells were stained with fluorescently conjugated antibodies against surface markers at 4 °C for 30 minutes in the dark. Antibodies used included CD3 (BV786) for T cells, CD14 (BV605) for monocytes, CD19 (PerCP-Cy5.5) for B cells, and CD15 (APC/Cy7) for granulocytes. After surface staining, cells were fixed in 2.5% formalin at room temperature for 20 minutes, washed with PBS/bovine serum albumin (BSA), and permeabilized using 0.1% saponin in PBS/BSA. Intracellular ROS was then detected using fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled reagents included in the Total ROS Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). Cells were resuspended in PBS/BSA for acquisition. Flow cytometry was conducted using a Cytek Aurora spectral cytometer at the University of Texas Southwestern Flow Cytometry Core Facility. Compensation beads were used to establish compensation settings for each fluorochrome. Gating was based on forward and side scatter properties and doublet discrimination (Figure 1). CD3+ and CD14+ cell populations were analyzed for ROS signal intensity. CD19+ and CD15+ populations were also evaluated, but no significant ROS changes were observed.

Plasma samples were analyzed using a custom Luminex Human High Sensitivity Cytokine Premixed Kit (R and D Systems, Inc.) to quantify levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10. Assays were conducted on the MAGPIX Luminex platform within the University of Texas Southwestern Microarray and Immune Phenotyping Core Facility. All plasma samples were stored at −80 °C until analysis.

Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo v10 (BD Biosciences). Histogram plots were used to visualize fluorescence signal intensities. Statistical analysis and graph generation were performed using GraphPad Prism v9. Comparisons between two groups were assessed using unpaired two-tailed t-tests. For multiple group comparisons, two-way analysis of variance was performed with Bonferroni post hoc correction. A P value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ROS values were reported as percentages of total cell count for each condition.

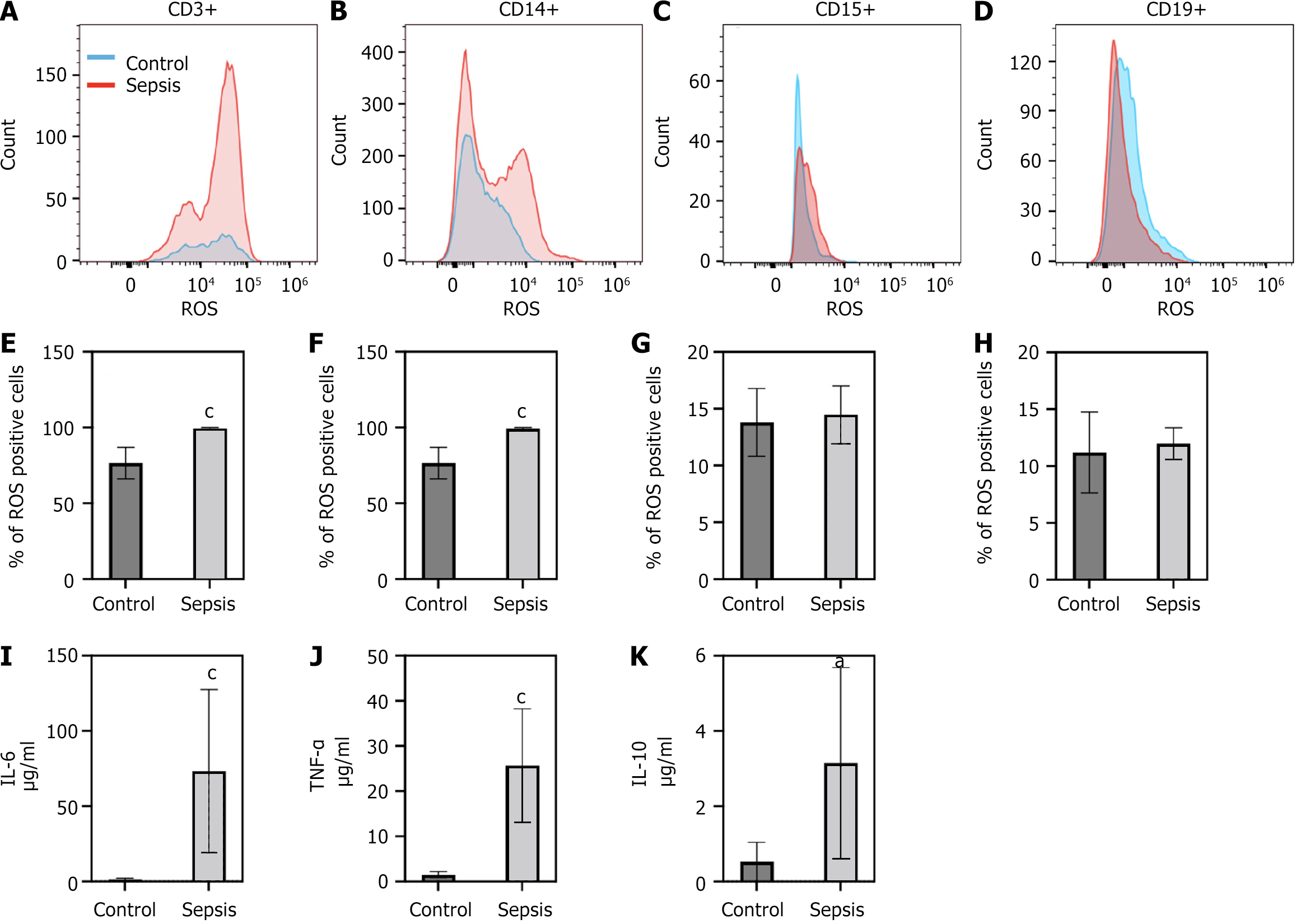

In the sepsis patient cohort, we found that there was an increase in signal of ROS in specific PBMCs populations as compared to our control patient cohort. We found that ROS signal was increased in CD3+ cells and CD14+ cells (Figure 2A, B, E and F). In contrast, no significant changes in ROS levels were noted in CD15+ or CD19+ cells (Figure 2C, D, G and H). Percent of ROS in cells was averaged from all patient samples (6 control patients and 6 sepsis patients) (Figure 2E-H) from gates defined in the methods (Figure 1). We also examined levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. TNF-α is one of the first pro-inflammatory cytokines released in response to infection. IL-6, another pro-inflammatory cytokine has been linked to sepsis disease severity. IL-10 levels have been correlated with sepsis-based immunosuppression. We found that in our septic cohort levels all three cytokines were significantly elevated as compared to our control patients (Figure 2I-K), indicating a mix of pro and anti-inflammation which is consistent with what would be expected in sepsis.

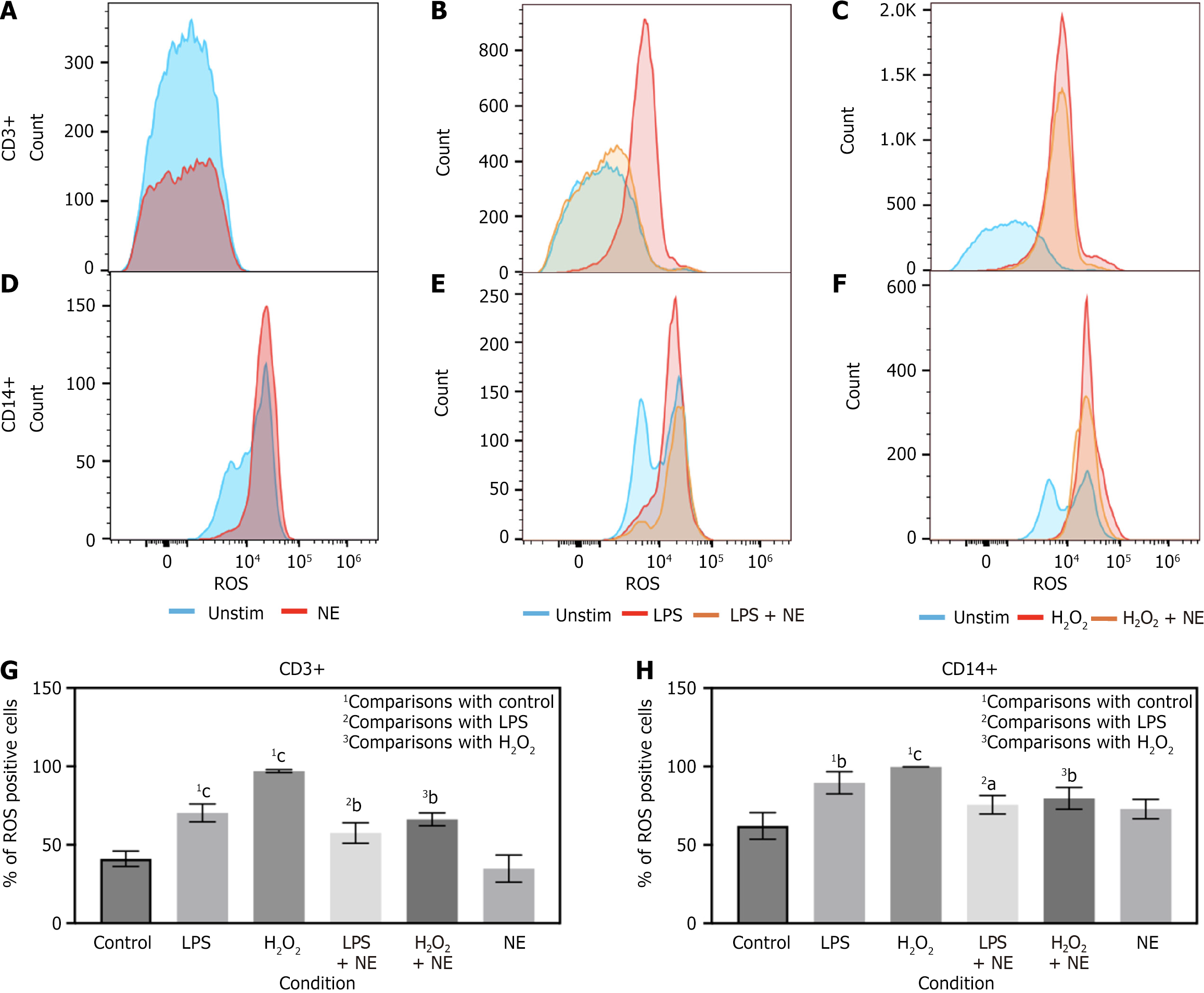

To further characterize this effect, we performed stimulation experiments with isolated PBMCs from our control cohort patients with LPS, H2O2, NE, LPS + NE or H2O2 + NE. LPS stimulation was utilized to pattern sepsis in an in vitro setting. H2O2 was utilized as a positive control to mimic the effects of ROS. NE was co-incubated separately in both stimulation conditions to evaluate its effects on PBMCs in these conditions. Cells were incubated in these conditions for 16 hours. We found that LPS and H2O2 both skewed towards greater levels of ROS in CD3+ and CD14+ cells, akin to what was seen to in our sepsis patient cohort (Figure 3B, C, E-H). Interestingly, NE blunted that effect in CD3+ cells and to a lesser degree in CD14+ cells (Figure 3B, C, E-H). In CD3+ cells NE stimulation alone trended toward reduced basal ROS levels which did not achieve statistical significance (Figure 3A and G). In contrast, NE had very little effect on basal levels of ROS in CD14+ cells (Figure 3D and H). Percent of ROS in cells was averaged from all tested patient samples and demonstrated significant reductions in CD3+ cells with NE in LPS and H2O2 treated cells, with less significant reductions in CD14+ cells (Figure 3G and H).

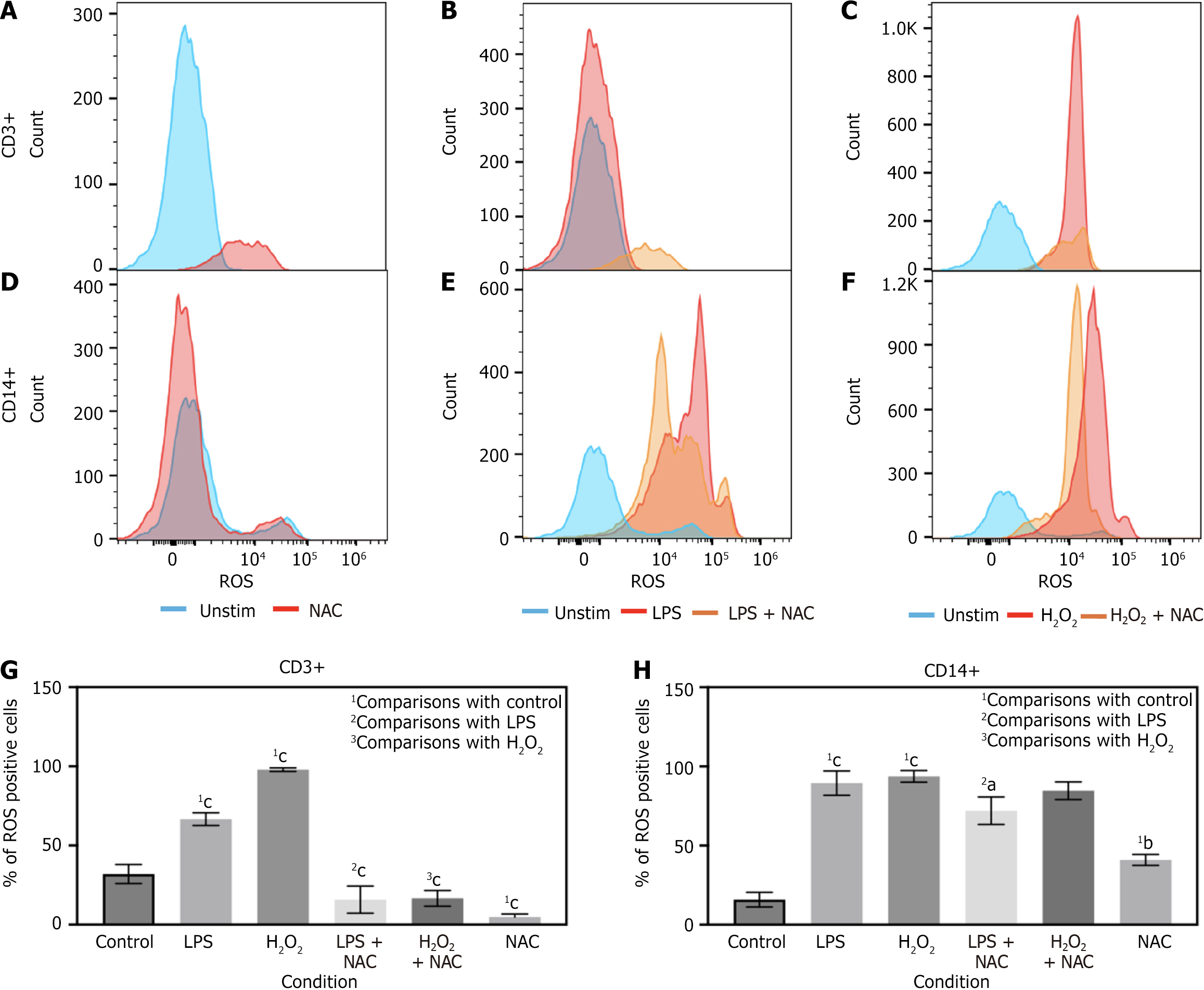

In a separate stimulation experiment, isolated PBMCs were similarly stimulated with LPS and H2O2, but this time utilizing NAC, LPS + NAC or H2O2 + NAC. We found that LPS and H2O2 both skewed towards greater levels of ROS in CD3+ and CD14+ cells (Figure 4B, C, E-H). NAC significantly blunted that effect in CD3+ cells in both the LPS and H2O2 conditions (Figure 4B, C and G). Interestingly, NAC decreased ROS levels in LPS treated cells and trended toward reductions in H2O2 treated CD14+ cells (Figure 4E, F and H). In CD3+ cells NAC stimulation alone trended toward reduced basal ROS levels which achieved statistical significance (Figure 4A and G). In contrast, NAC significantly increased basal ROS levels in CD14+ cells (Figure 4D and H). Percent of ROS in cells was averaged from all tested patient samples and demonstrated significant reductions in CD3+ cells with NAC in LPS and H2O2 treated cells, with less significant reductions in CD14+ cells with LPS+ NAC and non-significant reductions in H2O2 + NAC treated cells (Figure 4G and H) from the CD3 gate or the CD14 gate.

In this study, we observed significantly elevated levels of ROS in PBMCs from septic patients, with particularly notable increases in CD3+ T cells and CD14+ monocytes. Using in vitro stimulation models with LPS and H2O2, we replicated these ROS elevations in PBMCs from healthy controls, reinforcing the biological plausibility of our findings. These results suggest that sepsis is associated with increased oxidative stress in key immune cell subsets, a phenomenon that may contribute to the broader immune dysregulation observed in this condition, though direct causality remains to be determined.

T cells, essential for adaptive immunity, are particularly susceptible to oxidative damage, which can lead to reduced proliferation, impaired cytokine signaling, and eventual exhaustion[29]. Similarly, monocytes, while inherently equipped for oxidative responses during pathogen clearance, may experience dysfunction when overwhelmed by excessive ROS levels[16]. The more pronounced ROS increases observed in CD3+ cells compared to CD14+ cells may be due to higher basal ROS levels in monocytes or a greater oxidative susceptibility of T cells under septic conditions. These findings are consistent with previous studies linking mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS accumulation to immune suppression in sepsis[9].

On examination of serum cytokine levels are findings are consistent with the known literature[14,30]. TNF-α is one of the earliest pro-inflammatory cytokines released in response to infection and can also stimulate the release of IL-6, which is also elevated in our experimental model. IL-6 levels are also linked to sepsis disease severity[30,31]. IL-10, which is known for its anti-inflammatory role, is also elevated. This would indicate that IL-10 is being released in response to the pro-inflammatory phase initiated by the presence of TNF-α and IL-6. In sepsis, IL-10 have been correlated with sepsis-based immunosuppression[30,32].

Importantly, we show that both NE and NAC significantly reduce ROS levels in CD3+ and CD14+ PBMCs after LPS or H2O2 stimulation. We also examined NE and NAC treatment alone, which revealed baseline-modulating effects of both agents. These findings suggest that NE and NAC may act as immunomodulators through oxidative pathways, in addition to their known hemodynamic or antioxidant roles.

NE's role classically has been in the context of vasopressor support during septic shock. However, NE has been shown to modulate immune cell function through beta-adrenergic receptor signaling, which suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokines and enhances anti-inflammatory pathways such as IL-10 expression[13,14]. NE may also influence mitochon

In this study, NAC reduced ROS levels in T cells under both basal and stimulated conditions, supporting its thera

This study had several limitations. Our research strategy was to identify specific PBMC populations most affected by alterations in oxidative metabolism during sepsis. As this was an exploratory study, we utilized single cell markers to discriminate our global T-cell, monocyte, B-cell and neutrophil populations. This approach limited deeper insights into subpopulation-specific responses (e.g., Tregs, M1/M2 monocytes). We acknowledge this but, it did fulfill our goal in identifying specific populations affected by ROS levels. While we report changes in ROS levels, the underlying signaling pathways—including β-adrenergic signaling, mitochondrial metabolism, and redox-sensitive transcription factors—were not investigated in this study and will require future mechanistic exploration. Our results provide compelling evidence that oxidative stress is a key component of sepsis pathophysiology, and that NE and NAC represent promising agents for its mitigation. Targeting ROS production may offer a novel immunomodulatory strategy to restore immune homeostasis during sepsis.

This study demonstrates that intracellular ROS levels are elevated in CD3+ T cells and CD14+ monocytes from patients with sepsis, suggesting an altered redox environment in key immune cell subsets. These ROS elevations were replicated in vitro with LPS and H2O2 stimulation. Notably, co-treatment with NE or NAC reduced ROS accumulation in T cells and monocytes, supporting their potential as modulators of immune redox balance. While these results do not establish causality or therapeutic efficacy, they highlight potential of NE and NAC as adjunctive immunomodulatory agents that may restore redox balance in immune cells during sepsis. By targeting oxidative stress in specific PBMC subsets, NE and NAC could complement existing therapies and warrant further investigation in larger mechanistic and clinical studies.

This study has several important limitations. First, sepsis was defined using SEP-1/SEP-2 criteria, as real-time SOFA scoring was not feasible in the Department of Emergency setting. Second, our small sample size limited statistical power and generalizability of our findings. We did not perform formal power calculations, as this was an exploratory observational study. Future studies should include additional markers and a larger sample size to explore the effects of NE and NAC on other immune subsets and signaling pathways. Third, all patients in the sepsis cohort had pneumonia as the primary infection source, which may limit generalizability to other sepsis etiologies. Fourth, this study was also only observational and did not directly assess immune cell dysfunction or viability, nor did it evaluate in vivo outcomes. Furthermore, we did not quantify endogenous NE levels or examine patients with septic shock. Larger scale studies are needed to validate and expand upon these findings.

We would like to acknowledge the support of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Centers Flow Cytometry and Microarray and Immunology Phenotyping Core Laboratories.

| 1. | Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315:801-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15803] [Cited by in RCA: 18943] [Article Influence: 1894.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Hotchkiss RS, Moldawer LL, Opal SM, Reinhart K, Turnbull IR, Vincent JL. Sepsis and septic shock. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 919] [Cited by in RCA: 1119] [Article Influence: 111.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Venet F, Monneret G. Advances in the understanding and treatment of sepsis-induced immunosuppression. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14:121-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 665] [Article Influence: 73.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nathan C, Cunningham-Bussel A. Beyond oxidative stress: an immunologist's guide to reactive oxygen species. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:349-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 910] [Cited by in RCA: 1114] [Article Influence: 85.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Forrester SJ, Kikuchi DS, Hernandes MS, Xu Q, Griendling KK. Reactive Oxygen Species in Metabolic and Inflammatory Signaling. Circ Res. 2018;122:877-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1223] [Cited by in RCA: 1479] [Article Influence: 184.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bauer M, Wetzker R. The cellular basis of organ failure in sepsis-signaling during damage and repair processes. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2020;115:4-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sena LA, Li S, Jairaman A, Prakriya M, Ezponda T, Hildeman DA, Wang CR, Schumacker PT, Licht JD, Perlman H, Bryce PJ, Chandel NS. Mitochondria are required for antigen-specific T cell activation through reactive oxygen species signaling. Immunity. 2013;38:225-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 753] [Cited by in RCA: 1069] [Article Influence: 82.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Canton M, Sánchez-Rodríguez R, Spera I, Venegas FC, Favia M, Viola A, Castegna A. Reactive Oxygen Species in Macrophages: Sources and Targets. Front Immunol. 2021;12:734229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 57.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Delano MJ, Ward PA. The immune system's role in sepsis progression, resolution, and long-term outcome. Immunol Rev. 2016;274:330-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 606] [Article Influence: 67.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang Y, Tang B, Li H, Zheng J, Zhang C, Yang Z, Tan X, Luo P, Ma L, Wang Y, Long L, Chen Z, Xiao Z, Ma L, Zhou J, Wang Y, Shi C. A small-molecule inhibitor of Keap1-Nrf2 interaction attenuates sepsis by selectively augmenting the antibacterial defence of macrophages at infection sites. EBioMedicine. 2023;90:104480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang Z, Liu M, Ye D, Ye J, Wang M, Liu J, Xu Y, Zhang J, Zhao M, Feng Y, Xu S, Pan W, Luo Z, Li D, Wan J. Il12a Deletion Aggravates Sepsis-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction by Regulating Macrophage Polarization. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:632912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lozano-Rodríguez R, Avendaño-Ortíz J, Montalbán-Hernández K, Ruiz-Rodríguez JC, Ferrer R, Martín-Quirós A, Maroun-Eid C, González-López JJ, Fàbrega A, Terrón-Arcos V, Gutiérrez-Fernández M, Alonso-López E, Cubillos-Zapata C, Fernández-Velasco M, Pérez de Diego R, Pelegrin P, García-Palenciano C, Cueto FJ, Del Fresno C, López-Collazo E. The prognostic impact of SIGLEC5-induced impairment of CD8(+) T cell activation in sepsis. EBioMedicine. 2023;97:104841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Thoppil J, Mehta P, Bartels B, Sharma D, Farrar JD. Impact of norepinephrine on immunity and oxidative metabolism in sepsis. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1271098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ağaç D, Estrada LD, Maples R, Hooper LV, Farrar JD. The β2-adrenergic receptor controls inflammation by driving rapid IL-10 secretion. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;74:176-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Elenkov IJ, Wilder RL, Chrousos GP, Vizi ES. The sympathetic nerve--an integrative interface between two supersystems: the brain and the immune system. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:595-638. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Venet F, Demaret J, Gossez M, Monneret G. Myeloid cells in sepsis-acquired immunodeficiency. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2021;1499:3-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Austermann J, Roth J, Barczyk-Kahlert K. The Good and the Bad: Monocytes' and Macrophages' Diverse Functions in Inflammation. Cells. 2022;11:1979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Case AJ, Roessner CT, Tian J, Zimmerman MC. Mitochondrial Superoxide Signaling Contributes to Norepinephrine-Mediated T-Lymphocyte Cytokine Profiles. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Deo SH, Jenkins NT, Padilla J, Parrish AR, Fadel PJ. Norepinephrine increases NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells via α-adrenergic receptors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;305:R1124-R1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | De Flora S, Grassi C, Carati L. Attenuation of influenza-like symptomatology and improvement of cell-mediated immunity with long-term N-acetylcysteine treatment. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:1535-1541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chertoff J. N-Acetylcysteine's Role in Sepsis and Potential Benefit in Patients With Microcirculatory Derangements. J Intensive Care Med. 2018;33:87-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Peristeris P, Clark BD, Gatti S, Faggioni R, Mantovani A, Mengozzi M, Orencole SF, Sironi M, Ghezzi P. N-acetylcysteine and glutathione as inhibitors of tumor necrosis factor production. Cell Immunol. 1992;140:390-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Campos R, Shimizu MH, Volpini RA, de Bragança AC, Andrade L, Lopes FD, Olivo C, Canale D, Seguro AC. N-acetylcysteine prevents pulmonary edema and acute kidney injury in rats with sepsis submitted to mechanical ventilation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302:L640-L650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Abimannan T, Peroumal D, Parida JR, Barik PK, Padhan P, Devadas S. Oxidative stress modulates the cytokine response of differentiated Th17 and Th1 cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;99:352-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Aisa-Álvarez A, Pérez-Torres I, Guarner-Lans V, Manzano-Pech L, Cruz-Soto R, Márquez-Velasco R, Casarez-Alvarado S, Franco-Granillo J, Núñez-Martínez ME, Soto ME. Randomized Clinical Trial of Antioxidant Therapy Patients with Septic Shock and Organ Dysfunction in the ICU: SOFA Score Reduction by Improvement of the Enzymatic and Non-Enzymatic Antioxidant System. Cells. 2023;12:1330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pérez-Torres I, Aisa-Álvarez A, Casarez-Alvarado S, Borrayo G, Márquez-Velasco R, Guarner-Lans V, Manzano-Pech L, Cruz-Soto R, Gonzalez-Marcos O, Fuentevilla-Álvarez G, Gamboa R, Saucedo-Orozco H, Franco-Granillo J, Soto ME. Impact of Treatment with Antioxidants as an Adjuvant to Standard Therapy in Patients with Septic Shock: Analysis of the Correlation between Cytokine Storm and Oxidative Stress and Therapeutic Effects. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:16610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Malmberg KJ, Arulampalam V, Ichihara F, Petersson M, Seki K, Andersson T, Lenkei R, Masucci G, Pettersson S, Kiessling R. Inhibition of activated/memory (CD45RO(+)) T cells by oxidative stress associated with block of NF-kappaB activation. J Immunol. 2001;167:2595-2601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Magalhães LS, Melo EV, Damascena NP, Albuquerque ACB, Santos CNO, Rebouças MC, Bezerra MO, Louzada da Silva R, de Oliveira FA, Santos PL, da Silva JS, Lipscomb MW, da Silva ÂM, de Jesus AR, de Almeida RP. Use of N-acetylcysteine as treatment adjuvant regulates immune response in visceral leishmaniasis: Pilot clinical trial and in vitro experiments. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:1045668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Vardhana SA, Hwee MA, Berisa M, Wells DK, Yost KE, King B, Smith M, Herrera PS, Chang HY, Satpathy AT, van den Brink MRM, Cross JR, Thompson CB. Impaired mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation limits the self-renewal of T cells exposed to persistent antigen. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:1022-1033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 420] [Article Influence: 70.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | van der Poll T, van de Veerdonk FL, Scicluna BP, Netea MG. The immunopathology of sepsis and potential therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:407-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 746] [Cited by in RCA: 1340] [Article Influence: 148.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Jacob S, Jacob SA, Thoppil J. Targeting sepsis through inflammation and oxidative metabolism. World J Crit Care Med. 2025;14:101499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Padovani CM, Yin K. Immunosuppression in Sepsis: Biomarkers and Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators. Biomedicines. 2024;12:175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Atkinson MC. The use of N-acetylcysteine in intensive care. Crit Care Resusc. 2002;4:21-27. [PubMed] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/