Published online Dec 24, 2025. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v16.i12.111601

Revised: August 30, 2025

Accepted: November 11, 2025

Published online: December 24, 2025

Processing time: 172 Days and 17.7 Hours

Online adaptive radiotherapy (oART) has demonstrated improved target volume coverage and enhanced sparing of surrounding pelvic organs through daily re-optimization based on pretreatment imaging. Recently, iterative cone-beam com

To investigate intra-fractional CTV and OARs variation and their impact on iCBCT guided daily oART for postoperative cervical and endometrial cancer.

Seventeen patients treated with daily postoperative iCBCT guided oART with rigorous bladder and rectal preparation protocols were enrolled. CTV and OARs were contoured on pre- and post-treatment iCBCT scans. The average surface distance (ASD), dice similarity coefficient (DSC), and 95% Hausdorff distance (HD) were utilized to evaluate the difference between pre- and post-treatment structures. Dosimetric outcomes for the pretreatment target volumes and OARs were recalculated using posttreatment contours to assess the impact of intra-fractional variation.

A total of 434 treatment fractions were analyzed, with an average interval time of 22 minutes between two iCBCT scans. Minimal variations were observed in the bladder, rectum, and CTV both pre- and post-treatment, with DSC exceeding 0.8. The vaginal CTV exhibited centroid deviations of 0.46 mm anteriorly, 0.11 mm laterally, and 0.58 mm superiorly, along with ASD of 1.69 mm and 95% HD of 6.42 mm. Weak correlations were observed bet

Daily iCBCT-guided oART with strict bladder and rectal preparation effectively compensates for intra-fractional variations, maintaining CTV coverage and OAR sparing across all treatment fractions.

Core Tip: By analyzing 434 treatment fractions with rigorous bladder and rectal preparation protocols, the study demonstrated that intra-fractional motion of clinical target volumes and organs at risk was minimal and had negligible impact on dosimetric outcomes of postoperative cervical and endometrial cancer. These findings provide robust clinical evidence supporting the reliability and precision of iterative cone-beam computed tomography-guided online adaptive radiotherapy in the postoperative pelvic setting.

- Citation: Wang GY, Chen YN, Sun YL, Zhou B, Zhang FQ, Yan JF, Hu K. Impact evaluation of intra-fractional variation on online adaptive radiotherapy for postoperative cervical and endometrial cancer. World J Clin Oncol 2025; 16(12): 111601

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v16/i12/111601.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v16.i12.111601

Postoperative radiotherapy for endometrial cancer and early-stage cervical cancer treated with surgery, consisting of hysterectomy, could increase locoregional control rates and improve survival for patients with adverse prognostic factors[1,2]. The clinical target volume (CTV) that includes the proximal vagina and any paravaginal tissue (CTV-V)[3], and the inter-fractional motion of the vagina could be up to 27.9 mm induced by variation in adjacent bladder and rectum filling[4,5]. Of note, larger planning target volume (PTV) margins and volumes may increase the risk of irradiation toxicity, as higher intestinal doses have been associated with the fall of small intestine into the space vacated by the true pelvis after hysterectomy[6,7]. Currently, online adaptive radiotherapy (oART), which adapts to pelvic anatomical changes by daily re-contouring of target volumes and organs at risk (OARs), could reduce the PTV margin[8,9] and has significant advantages in postoperative radiotherapy for endometrial and cervical cancer.

Preliminary studies suggested that oART techniques achieved superior dosimetric coverage for the target volume and significantly improved dosimetry of surrounding OARs in pelvic malignancies[10,11], and in clinical practice the oART is entirely based on pretreatment imaging for per-fraction treatment plan re-optimization and reports the dosimetric results. However, it is reasonable to expect that intra-fractional variation of the filling status of the rectum and bladder has an impact on the position and shape of the adjacent CTV-V and novel CTV (CTV-N), resulting in dosimetry differences. Ensuring rigorous bladder filling and rectal emptying before treatment may help mitigate this movement to some extent. Currently, there are no studies which have precisely evaluated the impact of intra-fractional variation.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the intra-fractional position variations of the CTVs and OARs for postoperative cervical and endometrial cancer and their impact on daily iterative cone-beam computed tomography (CT)-guided oART dosimetry.

This study included a cohort of 17 patients from October 2022 to March 2023 who underwent hysterectomy for cervical or endometrial cancer and required postoperative radiotherapy due to high-risk factors. Patients who had indications for radiotherapy in the inguinofemoral region and extended-field pelvic radiotherapy were not enrolled in this study. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Peking Union Medical College Hospital, and all patients gave informed consent for participation in the study.

Separate CTV-N and CTV-V were contoured according to the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Consensus Guidelines[3]. A PTV was expanded by an isotropic margin of 0.5 cm from the CTV, and a prescribed dose of 45 Gy or 50.4 Gy in 25 or 28 fractions was applied to the PTV.

All patients underwent rigorous bladder and rectal preparation before the simulation and each fraction, including informing the patients of the treatment time in advance, emptying the rectum in advance, and emptying the bladder 1 hour and 40 minutes before the appointment time, and then drinking 450-500 mL of water within 10 minutes according to height and weight, to ensure repeatability and avoid intra-fraction errors.

All patients received daily postoperative iterative cone-beam CT (iCBCT)-guided oART (Ethos, Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, United States). Each pretreatment iCBCT scan (iCBCT1) was acquired with a tube voltage of 125 kVp, tube current of 1080 mAs, and contiguous 2-mm slice thickness. The typical scan dose parameters were CTDIVOL 21.60 mGy and DLP 324.0 mGy·cm, with an average scan time of 36.7 seconds. All scans were performed under the standard Pelvis clinical protocol of the Varian Ethos system and iCBCT reconstruction algorithm was used. The “influencer” (bladder, rectum and bowel) and CTV structures were automatically generated by the Ethos adaptive platform in iCBCT1. The physician then reviewed and manually edited the above structures, the adapted plan (adaptive treatment plan re-optimized based on the anatomical structure of the day) and scheduled plan (reference plan recalculated after matching the PTV modified on that day to ensure the maximum dose coverage of the PTV) was generated and selected. When the treatment was completed, the posttreatment iCBCT scan (iCBCT2) was acquired immediately.

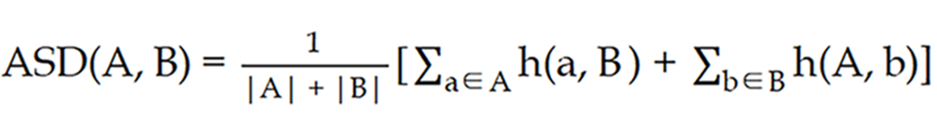

For all adaptive fractions from each patient, the posttreatment “influencer” and CTV structures were contoured on iCBCT2 by the same physician and verified by a second expert radiation oncologist. The centroid deviation of the above structures in three translation directions, posterior-anterior, left-right, and superior-inferior was measured to evaluate intra-fractional motion. In addition, the average surface distance (ASD), dice similarity coefficient (DSC), and 95% Hausdorff distance (HD) were used to evaluate the difference between pre- and posttreatment CTVs and "influencer". The ASD describes the difference between the boundaries of two structures and is used to compare the similarity of the contours of two structures[12]. The following formula was used:

Where A and B represent the pre- and posttreatment CTVs, respectively; the h (a, B) represents the minimum distance from a point a on contour A to contour B; the h (A, b) represents the minimum distance from a point b on contour B to contour A.

The DSC evaluates the similarity between the pre- and post-treatment CTVs by calculating the degree of overlap[13], using the following formula: DSC (A, B) = 2 |A∩B|/(|A| + |B|), where |A| represents the volume of pretreatment CTV contour, |B| represents the volume of posttreatment CTV contour, and |A∩B| represents the volume where the two contours overlap.

HD evaluates the similarity between the pre- and post-treatment CTV contours by calculating the distance between them[12,14], while 95% HD represents the distance value at the 95th percentile after all the aforementioned distances are sorted from small to large. And 95% HD could eliminate the influence of abnormal outliers and is more robust than HD, as shown in the following formula: HD (A, B) = max [h (A, B), h (B, A)], where h (A, B) represents the maximum value of the distances from all points on the pretreatment CTV contour A to the posttreatment CTV contour B. Similarly, h (B, A) represents the maximum value of the distances from all points on the posttreatment CTV contour B after treatment to the pretreatment CTV contour A.

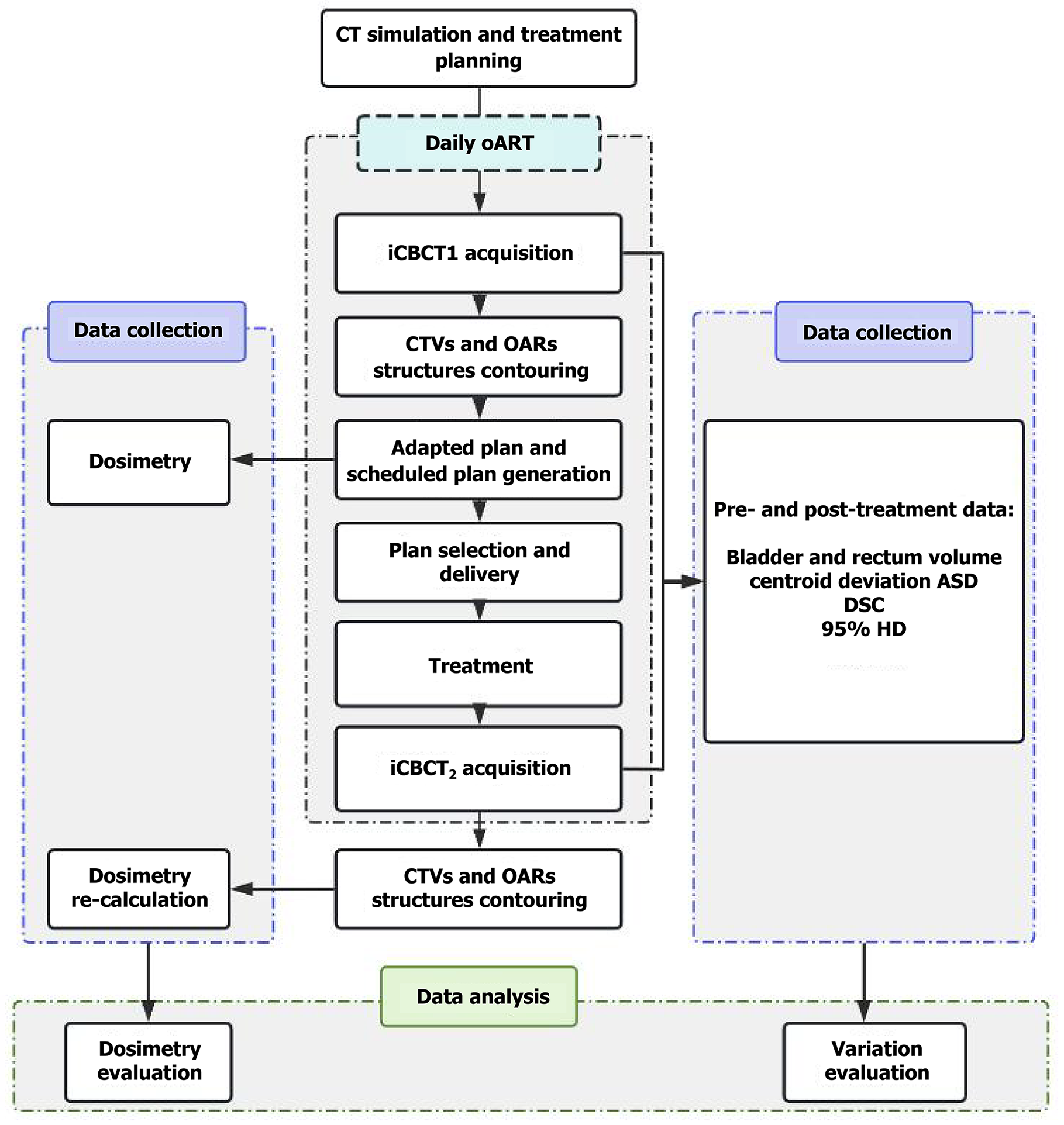

The V100% (volume of CTV-N and CTV-V receiving 100% of the prescribed dose), D99% (the dose to 99% volume of CTV-N and CTV-V), and the dose of OARs were recorded for each fraction. A comparison was made between the adapted and scheduled plans. To assess the impact of intra-fractional variation on target volumes and OARs, dosimetric outcomes for the pretreatment target volumes and OARs were recalculated using posttreatment contours. This was performed via a Python-based automated analysis program (Python 3.9), comparing two conditions: The adapted plan with posttreatment contours (adapted plan + iCBCT2), and the scheduled plan with posttreatment contours (scheduled plan + iCBCT2). These results were further compared to the pretreatment dosimetry, which included the adapted plan with pretreatment contours (adapted plan + iCBCT1) and the scheduled plan with pretreatment contours (scheduled plan + iCBCT1). The workflow of this study is shown in Figure 1.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 27.0 (IBM. Corp., New York, NY, United States). Given that the CTV-V is susceptible to daily change due to the pushing boundaries of the adjacent bladder and rectum, a least-square linear regression was used to analyze the correlation between CTV-V deviation and factors including average time, volume difference, volume increase rate, and centroid deviation of surrounding organs. r was calculated to assess the strength of these correlations. Additionally, the Mann-Whitney U test was applied to compare the intra-fractional CTV-V centroid deviations between fractions with average treatment times less than 25 minutes and those exceeding 25 minutes. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

All patients completed the anticipated daily oART, with a total of 434 fractions. The adapted plan was selected for all fractions, and the average time between iCBCT1 and iCBCT2 was 22 minutes (range: 17-32 minutes).

The mean bladder volumes before and after treatment measured from iCBCT1 and iCBCT2 were 353.9 ± 130.2 cm3 and 397.9 ± 138.7 cm3, respectively. The mean rectal volumes before and after treatment measured from iCBCT1 and iCBCT2 were 62.9 ± 33.5 cm3 and 61.9 ± 25.9 cm3, respectively. For the difference between pre- and post-treatment CTVs and "influencer", the overlap rates of CTV-N, CTV-V, bladder and rectum were high before and after treatment, with DSC values greater than 0.8, while the DSC value of bowel was 0.6. The centroid deviation of CTV-V was 0.46 ± 2.58 mm that indicated motion in the anterior direction, -0.11 ± 1.42 mm that indicated motion in the left direction, and -0.58 ± 7.27 mm that indicated motion in the superior direction. The detailed values for ASD, DSC, 95% HD and centroid deviation are shown in Table 1.

| Region | ASD (mm) | DSC | 95% HD (mm) | Posterior-anterior (mm) | Left-right (mm) | Superior-inferior (mm) |

| CTV-N | 0.83 ± 0.33 | 0.9 ± 0.09 | 3.94 ± 1.17 | 0.75 ± 1.05 | -0.14 ± 1.31 | -0.71 ± 6.69 |

| CTV-V | 1.69 ± 0.74 | 0.8 ± 0.11 | 6.42 ± 2.45 | 0.46 ± 2.58 | -0.11 ± 1.42 | -0.58 ± 7.27 |

| Bladder | 1.75 ± 1.02 | 0.91 ± 0.04 | 7.24 ± 3.92 | 0.34 ± 2.01 | -0.20 ± 1.09 | -1.02 ± 5.57 |

| Rectum | 1.71 ± 1.09 | 0.81 ± 0.08 | 7.67 ± 4.54 | 0.17 ± 2.09 | 0.27 ± 1.59 | 1.38 ± 8.12 |

| Bowel | 3.56 ± 1.79 | 0.6 ± 0.25 | 18.8 ± 14 | -3.99 ± 4.17 | 0.29 ± 6.07 | 1.47 ± 31.08 |

There was no significant correlation between the time from iCBCT1 to iCBCT2 and the centroid deviation of CTV-V in the posterior-anterior, left-right, and superior-inferior directions (P = 0.612, 0.092 and 0.092, respectively). Additionally, no significant difference in centroid deviation of CTV-V was observed between fractions with the treatment time of less than 25 minutes and those exceeding 25 minutes, across the above three directions (P = 0.773, 0.392 and 0.392, respectively; Supplementary Figure 1).

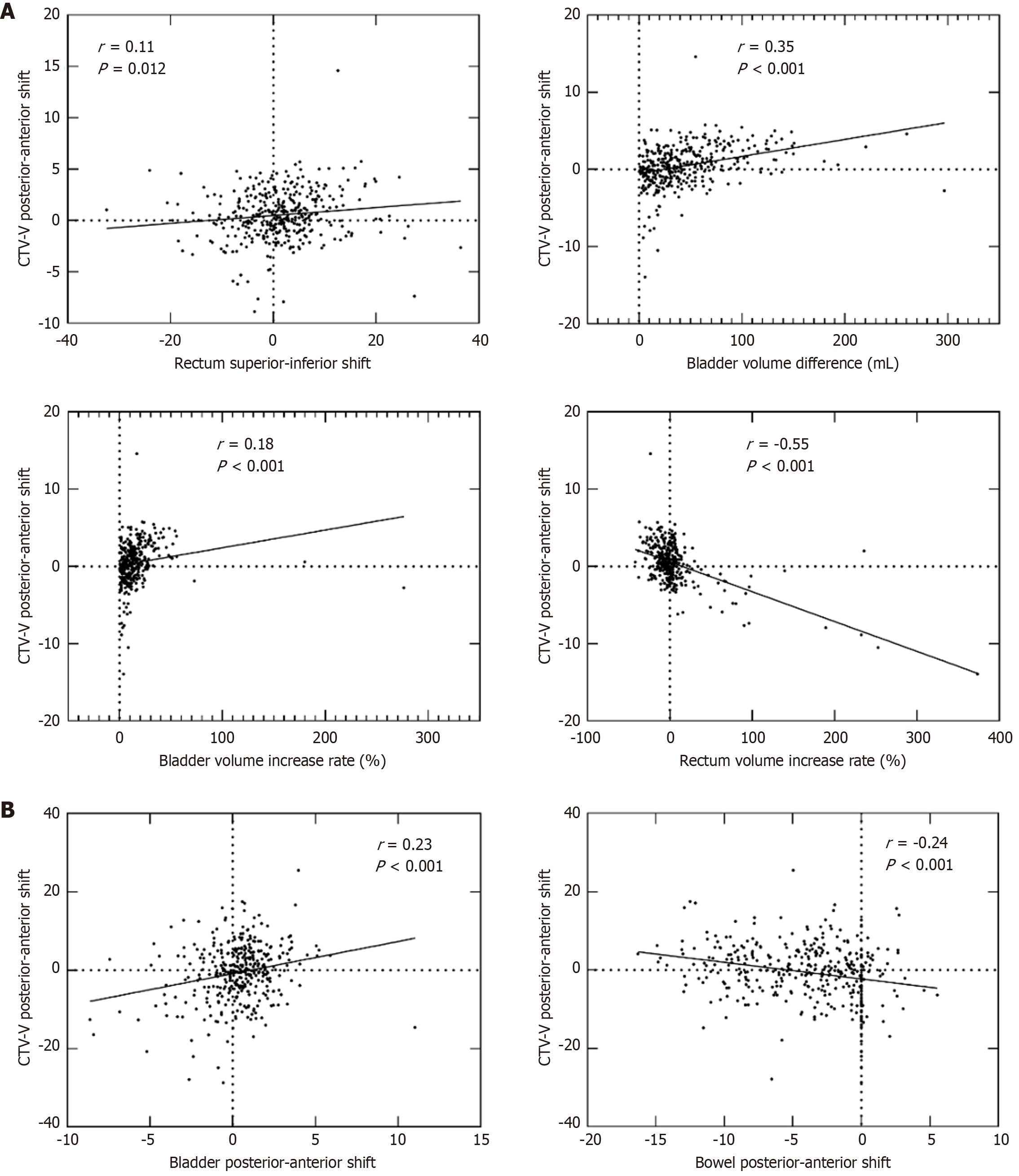

Organ motion and volume variation had a weak impact on CTV-V motion, as shown in Figure 2. A weak but statistically significant correlation was observed between the centroid deviation of CTV-V in the posterior-anterior direction (Figure 2A) and the rectal centroid deviation in the superior-inferior direction (P = 0.017, r = 0.11). Additionally, weak correlations were found with bladder volume differences (P < 0.001, r = 0.35), bladder volume increase rate (P < 0.001, r = 0.18), and rectum volume increase rate (P < 0.001, r = -0.55). The anterior shifts in the centroid deviations of the bladder and rectum, along with the posterior shift in the centroid deviation of the bowel (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, and P = 0.021, respectively; r = 0.59, 0.64, and 0.12, respectively), combined with variations in bladder and rectum volumes, collectively contributed to the anterior displacement of the CTV. In addition, the centroid deviations of the bladder and bowel in the posterior-anterior direction were weakly correlated with the CTV-V centroid deviations in the superior-inferior direction (both P < 0.001, r = 0.23 and -0.24, respectively). No significant correlation was identified between rectum or bladder volume difference or increased rate and the centroid deviations of CTV-V in the superior-inferior direction.

Pre- and post-treatment dosimetric outcomes for all 434 fractions were analyzed. The results of the pre- and post-treatment dosimetric outcomes showed that there was no significant difference in CTV-N coverage, with the adapted plan (99.94% vs 99.08% V100%; 100.87% vs 100.04% D99%) and scheduled plan (97.02% vs 96.40% V100%; 100.03% vs 99.36% D99%). Similar findings were observed for the pre- and post-treatment CTV-V, with the adapted plan (99.97% vs 98.66% V100%; 100.84% vs 99.07% D99%) and scheduled plan (96.11% vs 96.41% V100%; 92.97% vs 95.65% D99%). Additionally, minimal differences were noted in the pre- and post-treatment dosimetric outcomes for the OARs, including bladder, rectum, and bowel. The complete dosimetry comparisons are presented in Table 2.

| ROIs | Dosimetric metrics | Adapted plan + iCBCT1 | Adapted plan + iCBCT2 | Scheduled plan + iCBCT1 | Scheduled plan + iCBCT2 | P1 value | P2 value |

| CTV-N | V100% (%) | 99.94 ± 0.09 | 99.08 ± 8.88 | 97.02 ± 6.47 | 96.40 ± 10.72 | 0.45 | 0.34 |

| CTV-N | D99% (%) | 100.87 ± 0.20 | 100.04 ± 8.96 | 100.03 ± 1.41 | 99.36 ± 9.07 | 0.99 | 0.16 |

| CTV-V | V100% (%) | 99.97 ± 0.05 | 98.66 ± 9.02 | 96.11 ± 3.71 | 96.41 ± 9.80 | < 0.05 | 0.58 |

| CTV-V | D99% (%) | 100.84 ± 0.19 | 99.07 ± 10.57 | 92.97 ± 9.00 | 95.65 ± 11.15 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| Bladder | V40Gy (%) | 24.62 ± 4.54 | 26.22 ± 5.32 | 26.16 ± 5.80 | 27.35 ± 6.00 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| V30Gy (%) | 38.49 ± 5.93 | 40.25 ± 6.28 | 40.62 ± 6.96 | 41.80 ± 6.83 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | |

| V20Gy (%) | 59.72 ± 7.05 | 61.54 ± 7.01 | 63.13 ± 8.99 | 64.19 ± 8.37 | < 0.05 | 0.09 | |

| V10Gy (%) | 92.40 ± 3.78 | 92.91 ± 3.40 | 94.10 ± 3.91 | 94.19 ± 3.55 | < 0.05 | 0.75 | |

| Dmean (Gy) | 26.77 ± 1.95 | 27.38 ± 2.06 | 27.71 ± 2.55 | 28.10 ± 2.48 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | |

| Rectum | V40Gy (%) | 38.18 ± 9.26 | 37.36 ± 11.01 | 39.39 ± 14.46 | 37.74 ± 13.82 | 0.47 | 0.11 |

| V30Gy (%) | 56.53 ± 10.42 | 56.49 ± 11.36 | 59.77 ± 14.15 | 58.79 ± 13.53 | 0.06 | 0.33 | |

| V20Gy (%) | 74.13 ± 9.64 | 74.70 ± 9.79 | 79.11 ± 10.51 | 78.84 ± 10.04 | < 0.05 | 0.71 | |

| V10Gy (%) | 94.27 ± 4.61 | 94.42 ± 4.67 | 95.54 ± 4.01 | 95.71 ± 3.75 | < 0.05 | 0.55 | |

| Dmean (Gy) | 31.67 ± 3.39 | 31.61 ± 3.60 | 32.82 ± 4.29 | 32.48 ± 4.00 | 0.06 | 0.26 | |

| Bowel | V40Gy (%) | 12.48 ± 6.39 | 9.92 ± 5.44 | 12.93 ± 6.73 | 10.24 ± 5.83 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| V30Gy (%) | 23.83 ± 10.91 | 21.11 ± 10.38 | 25.38 ± 11.99 | 22.11 ± 11.36 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | |

| V20Gy (%) | 41.30 ± 17.02 | 39.45 ± 17.04 | 47.04 ± 19.78 | 44.79 ± 19.83 | < 0.05 | 0.11 | |

| V10Gy (%) | 60.24 ± 24.25 | 59.60 ± 24.74 | 69.08 ± 27.92 | 68.75 ± 28.37 | 0.36 | 0.88 | |

| Dmean (Gy) | 18.05 ± 7.33 | 17.23 ± 7.17 | 19.83 ± 8.12 | 18.93 ± 7.91 | 0.07 | 0.12 |

Currently, reported outcomes of adaptive radiotherapy have been based on pretreatment adjustments[15,16]. However, intra-fractional motion, including the dynamic changes in the position and shape of adjacent organs such as the bladder, rectum, and bowel, may influence the accuracy of dose delivery and target coverage. We designed the current prospective study in which iCBCT scans were obtained before and after treatment during daily pelvic oART to determine the impact of intra-fractional anatomical variations on target volume (CTV-N and CTV-V) positioning and dosimetry in postoperative cervical and endometrial cancer patients who were carefully instructed to fill bladders and empty rectums before simulation and intra-fraction iCBCT scans.

Previous research has predominantly focused on inter-fractional variations, which are driven by changes in bladder and rectal filling between treatment sessions. Jhingran et al[4] measured the vaginal cuff motion during pelvic intensity-modulated radiation therapy after hysterectomy, with patients instructed to fill their bladders in a standardized way. Their results indicated that the median maximum marker motion was 0.59 cm in the left-right direction, 1.46 cm in the anterior-posterior direction, and 1.2 cm in the superior-inferior direction. Jürgenliemk-Schulz et al[17] found that to achieve complete coverage of 95% of the inter-fractional vaginal volumes, an expansion of 2.3 cm was required in the anterior-posterior direction, 1.8 cm in the left-right direction, and 1.5 cm in the cranial direction. In contrast, daily oART has the advantage of adapting to the deforming postoperative bed and minimizing inter-fractional motion for each treatment session. In this study, the target volume and OARs were contoured both before and after treatment to accurately assess intra-fractional variation. The results demonstrated that the centroid of CTV-V shifted by 0.46 mm in the anterior-posterior direction, 0.11 mm in the left-right direction, and 0.58 mm in the superior-inferior direction. These shifts were significantly smaller than the previously reported inter-fractional variations, underscoring the importance of real-time adaptation in radiotherapy. In addition, image verification and registration were performed before each treatment fraction to correct deviations, and the results further confirmed that the 5 mm PTV margin used in this study was sufficient.

Intra-fractional variations are influenced by treatment time, as longer durations allow more time for organ motion, which affects contour accuracy. This is an important factor to consider due to its relevance to patient compliance and treatment efficacy[18]. Compared to the treatment times of up to 1 hour required for magnetic resonance-guided linear accelerator to adapt the CTV and OARs[19,20], iCBCT-guided oART allows for target contouring and plan re-optimization in a shorter time, with an average treatment time of approximately 22 minutes in this study. However, no significant correlation was found between treatment time and CTV-V centroid deviation in the three directions. Previous studies have shown that intra-fractional variations in rectal gas, compared to the entire rectum volume, are relatively small and remain stable for 20-25 minutes in cervical cancer patients[21]. Consequently, we compared CTV-V centroid deviation between fractions with treatment time shorter or longer than 25 minutes. However, our analysis revealed no significant difference in CTV-V centroid deviation between these two groups. This implied that no certain benefit of limiting the treatment time within 25 minutes was confirmed in this study. This may be attributed to the fact that the longest treatment time in this study was only 32 minutes, and relatively short differences in treatment durations likely resulted in reduced intra-fractional variations caused by bladder and rectal filling, as reflected by the DSC values being greater than 0.8.

In contrast, bowel motion is more unpredictable and may significantly impact dosimetry in pelvic radiotherapy[22-24]. Our findings showed that the lower DSC value for the bowel, at 0.6, indicated that bowel motion during treatment is more variable compared to that of the bladder and rectum. Importantly, a low DSC for the bowel does not necessarily indicate inadequate contouring. The bowel is highly mobile even within the same fraction due to peristalsis, which is a well-recognized phenomenon in the literature, especially when a bowel bag is included in the contouring. Although iCBCT provides slightly lower soft-tissue resolution than diagnostic CT, all contours in this study were delineated by experienced radiation oncologists and verified independently, ensuring contouring consistency. To complement the DSC, we also evaluated 95% HD, which is more sensitive to local deformation and boundary shifts. The combined use of DSC and 95% HD therefore supports that the observed variability reflects genuine bowel motion rather than technical inaccuracy. Several approaches have been explored to reduce intestinal inter-fractional changes, including pretreatment enemas and the use of oral antidiarrheal medications after chemotherapy to minimize intestinal movement. However, these approaches are primarily employed in brachytherapy with fewer fractions and are challenging to implement in external radiotherapy, which typically involves 25 to 28 fractions. Despite the large geometric variation of the bowel, the dosimetric impact in our study was minimal. This apparent discrepancy can be explained by the fact that a low DSC primarily reflects shape variability and random redistribution of bowel, rather than a systematic shift toward the high-dose region. Centroid analysis and bowel dosimetry (V40 Gy) also indicated nonspecific boundary fluctuations rather than persistent displacement into target volumes. In addition, anatomically, postoperative bowel loops are dispersed within the pelvis and less likely to remain adjacent to the high-dose isodose surfaces, with the sigmoid colon contributing more to dose proximity than the small bowel[25]. Furthermore, compared to conventional treatment planning, daily adaptive radiotherapy re-optimizes the dose distribution at each fraction to spare bowel, effectively mitigating the impact of unpredictable motion on dosimetry[26]. These findings are consistent with emerging evidence that adaptive workflows can improve the dosimetric results.

Previous studies have indicated a weak correlation between target volume shifts in the cervical region along the anterior-posterior axis and changes in rectal volume[27,28]. Our findings demonstrated a weak negative correlation between CTV-V centroid shifts and the rectum volume increase rate (P < 0.001, r = -0.55). This suggests that while bladder and rectal motion could affect CTV positioning, the extent of movement was limited, likely due to the bladder filling and rectal emptying protocols employed before treatment, which helped to reduce variability. In our study, the mean rectal volumes before and after treatment were nearly identical under conditions of advanced rectal emptying.

A notable observation from this study is that intra-fractional variations in bladder and rectum positioning were minimal and had no significant impact on dosimetric outcomes. This finding indicated that, with rigorous bladder-rectum preparation and within a specified timeframe, the structures contoured on the adapted images could be directly utilized for dosimetric representation. The overlap rates for CTV-N, CTV-V, bladder, and rectum remained high both before and after treatment, with DSC values exceeding 0.8 in most cases, indicating strong concordance between pre- and posttreatment volumes. Despite small centroid deviations in CTV-V, with 0.46 mm in the anterior direction and -0.58 mm along the superior–inferior axis that indicated a minor superior shift, these shifts did not result in clinically significant differences in CTV dosimetric coverage or OARs sparing. The adapted plan consistently maintained high CTV coverage before and after treatment, with V100% and D99% values for CTV-N and CTV-V differing by less than 1% between pre- and post-treatment dosimetric evaluations. This suggests that the daily adaptive radiotherapy workflow used in this study is robust, effectively compensating for minor anatomical changes within each treatment fraction.

The limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size, primarily due to the significant clinic resources required for its implementation. Although our study only included 17 patients, a total of 434 daily oART fractions were analyzed, with each posttreatment structure being re-contoured. Additionally, this study focused solely on iCBCT-guided oART. The limited image quality of iCBCT compared to diagnostic CT or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging may affect contouring accuracy, particularly for soft-tissue targets such as CTV-V. Also, the intra-fractional variation may have a different impact on dosimetric outcomes of MR-guided adaptive radiotherapy, which typically involves longer treatment durations. In addition, our cohort included only postoperative patients, for whom inguinal irradiation was not indicated. Incorporating patients requiring inguinal or para-aortic irradiation in future studies could enhance representativeness and provide further insights into intra-fractional variations. Future multi-center studies with larger cohorts are warranted to validate and generalize these findings.

This study demonstrated that intra-fractional position variations of the CTVs and OARs in daily iCBCT-based oART with a 5 mm PTV margin for postoperative endometrial and cervical cancer have minimal impact on the dosimetric outcomes. The bladder and rectum showed limited intra-fractional motion with rigorous preparation and rapid adaption, and the adaptive workflow effectively compensated for anatomical changes, ensuring adequate CTV coverage and sparing of OARs across all fractions.

The authors sincerely thank the radiation oncologists, therapists and medical physicists at our department for their technical support and assistance in data acquisition and patient care.

| 1. | Huang H, Feng YL, Wan T, Zhang YN, Cao XP, Huang YW, Xiong Y, Huang X, Zheng M, Li YF, Li JD, Chen GD, Li H, Chen YL, Ma LG, Yang HY, Li L, Yao SZ, Ye WJ, Tu H, Huang QD, Liang LZ, Liu FY, Liu Q, Liu JH. Effectiveness of Sequential Chemoradiation vs Concurrent Chemoradiation or Radiation Alone in Adjuvant Treatment After Hysterectomy for Cervical Cancer: The STARS Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:361-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ngu SF, Ngan HY, Chan KK. Role of adjuvant and post-surgical treatment in gynaecological cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;78:2-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Small W Jr, Bosch WR, Harkenrider MM, Strauss JB, Abu-Rustum N, Albuquerque KV, Beriwal S, Creutzberg CL, Eifel PJ, Erickson BA, Fyles AW, Hentz CL, Jhingran A, Klopp AH, Kunos CA, Mell LK, Portelance L, Powell ME, Viswanathan AN, Yacoub JH, Yashar CM, Winter KA, Gaffney DK. NRG Oncology/RTOG Consensus Guidelines for Delineation of Clinical Target Volume for Intensity Modulated Pelvic Radiation Therapy in Postoperative Treatment of Endometrial and Cervical Cancer: An Update. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;109:413-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jhingran A, Salehpour M, Sam M, Levy L, Eifel PJ. Vaginal motion and bladder and rectal volumes during pelvic intensity-modulated radiation therapy after hysterectomy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:256-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Agrawal R, Jafar S, Choudhary P, Anbalagan D, Singh D, Agarwal S. Assessment and implication of rectal filling on vaginal motion in postoperative carcinoma endometrium patients during image guided radiotherapy. J Cancer Res Ther. 2021;17:157-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Huscher A, Bignardi M, Magri E, Vitali E, Pasinetti N, Costa L, Frata P, Magrini SM. Determinants of small bowel toxicity in postoperative pelvic irradiation for gynaecological malignancies. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:4821-4826. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Klopp AH, Yeung AR, Deshmukh S, Gil KM, Wenzel L, Westin SN, Gifford K, Gaffney DK, Small W Jr, Thompson S, Doncals DE, Cantuaria GHC, Yaremko BP, Chang A, Kundapur V, Mohan DS, Haas ML, Kim YB, Ferguson CL, Pugh SL, Kachnic LA, Bruner DW. Patient-Reported Toxicity During Pelvic Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy: NRG Oncology-RTOG 1203. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2538-2544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 269] [Article Influence: 33.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang G, Wang Z, Guo Y, Zhang Y, Qiu J, Hu K, Li J, Yan J, Zhang F. Evaluation of PTV margins with daily iterative online adaptive radiotherapy for postoperative treatment of endometrial and cervical cancer: a prospective single-arm phase 2 study. Radiat Oncol. 2024;19:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang G, Wang Z, Zhang Y, Sun X, Sun Y, Guo Y, Zeng Z, Zhou B, Hu K, Qiu J, Yan J, Zhang F. Daily Online Adaptive Radiation Therapy of Postoperative Endometrial and Cervical Cancer With PTV Margin Reduction to 5 mm: Dosimetric Outcomes, Acute Toxicity, and First Clinical Experience. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2024;9:101510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | de Jong R, Visser J, van Wieringen N, Wiersma J, Geijsen D, Bel A. Feasibility of Conebeam CT-based online adaptive radiotherapy for neoadjuvant treatment of rectal cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2021;16:136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shelley CE, Bolt MA, Hollingdale R, Chadwick SJ, Barnard AP, Rashid M, Reinlo SC, Fazel N, Thorpe CR, Stewart AJ, South CP, Adams EJ. Implementing cone-beam computed tomography-guided online adaptive radiotherapy in cervical cancer. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2023;40:100596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Taha AA, Hanbury A. Metrics for evaluating 3D medical image segmentation: analysis, selection, and tool. BMC Med Imaging. 2015;15:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1293] [Cited by in RCA: 1264] [Article Influence: 114.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | La Macchia M, Fellin F, Amichetti M, Cianchetti M, Gianolini S, Paola V, Lomax AJ, Widesott L. Systematic evaluation of three different commercial software solutions for automatic segmentation for adaptive therapy in head-and-neck, prostate and pleural cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7:160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Huttenlocher DP, Klanderman GA, Rucklidge WJ. Comparing images using the Hausdorff distance. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Machine Intell. 1993;15:850-863. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Yen A, Zhong X, Lin MH, Nwachukwu C, Albuquerque K, Hrycushko B. Optimizing Online Adaptation Timing in the Treatment of Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2024;14:e159-e164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yen A, Choi B, Inam E, Yeh A, Lin MH, Park C, Hrycushko B, Nwachukwu C, Albuquerque K. Spare the Bowel, Don't Spoil the Target: Optimal Margin Assessment for Online Cone Beam Adaptive Radiation Therapy (OnC-ART) of the Cervix. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2023;13:e176-e183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jürgenliemk-Schulz IM, Toet-Bosma MZ, de Kort GA, Schreuder HW, Roesink JM, Tersteeg RJ, van der Heide UA. Internal motion of the vagina after hysterectomy for gynaecological cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2011;98:244-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Traeger L, Greer JA, Fernandez-Robles C, Temel JS, Pirl WF. Evidence-based treatment of anxiety in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1197-1205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | de Mol van Otterloo SR, Christodouleas JP, Blezer ELA, Akhiat H, Brown K, Choudhury A, Eggert D, Erickson BA, Faivre-Finn C, Fuller CD, Goldwein J, Hafeez S, Hall E, Harrington KJ, van der Heide UA, Huddart RA, Intven MPW, Kirby AM, Lalondrelle S, McCann C, Minsky BD, Mook S, Nowee ME, Oelfke U, Orrling K, Sahgal A, Sarmiento JG, Schultz CJ, Tersteeg RJHA, Tijssen RHN, Tree AC, van Triest B, Hall WA, Verkooijen HM. The MOMENTUM Study: An International Registry for the Evidence-Based Introduction of MR-Guided Adaptive Therapy. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Alongi F, Rigo M, Figlia V, Cuccia F, Giaj-Levra N, Nicosia L, Ricchetti F, Sicignano G, De Simone A, Naccarato S, Ruggieri R, Mazzola R. 1.5 T MR-guided and daily adapted SBRT for prostate cancer: feasibility, preliminary clinical tolerability, quality of life and patient-reported outcomes during treatment. Radiat Oncol. 2020;15:69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shortall J, Vasquez Osorio E, Cree A, Song Y, Dubec M, Chuter R, Price G, McWilliam A, Kirkby K, Mackay R, van Herk M. Inter- and intra-fractional stability of rectal gas in pelvic cancer patients during MRIgRT. Med Phys. 2021;48:414-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yen A, Zhong X, Lin MH, Nwachukwu C, Albuquerque K, Hrycushko B. Improved Dosimetry with Daily Online Adaptive Radiotherapy for Cervical Cancer: Waltzing the Pear. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2024;36:165-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yao L, Zhu L, Wang J, Liu L, Zhou S, Jiang S, Cao Q, Qu A, Tian S. Positioning accuracy during VMAT of gynecologic malignancies and the resulting dosimetric impact by a 6-degree-of-freedom couch in combination with daily kilovoltage cone beam computed tomography. Radiat Oncol. 2015;10:104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Meerschaert R, Nalichowski A, Burmeister J, Paul A, Miller S, Hu Z, Zhuang L. A comprehensive evaluation of adaptive daily planning for cervical cancer HDR brachytherapy. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2016;17:323-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Georg P, Georg D, Hillbrand M, Kirisits C, Pötter R. Factors influencing bowel sparing in intensity modulated whole pelvic radiotherapy for gynaecological malignancies. Radiother Oncol. 2006;80:19-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ghosh S, Gurram L, Kumar A, Mulye G, Mittal P, Chopra S, Kharbanda D, Hande V, Ghadi Y, Scaria L, Dheera A, Varghese GB, Kole S, Ansari S, Mahantshetty U, Agarwal JP. Clinical Implementation of "Plan of the Day" Strategy in Definitive Radiation Therapy of Cervical Cancer: Online Adaptation to Address the Challenge of Organ Filling Reproducibility. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2024;118:605-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | van de Bunt L, Jürgenliemk-Schulz IM, de Kort GA, Roesink JM, Tersteeg RJ, van der Heide UA. Motion and deformation of the target volumes during IMRT for cervical cancer: what margins do we need? Radiother Oncol. 2008;88:233-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Tan Mbbs Mrcp Frcr Md LT, Tanderup PhD K, Kirisits PhD C, de Leeuw PhD A, Nout Md PhD R, Duke Mbbs Frcr S, Seppenwoolde PhD Y, Nesvacil PhD N, Georg PhD D, Kirchheiner PhD K, Fokdal Md PhD L, Sturdza Md Frcpc A, Schmid Md M, Swamidas PhD J, van Limbergen Md PhD E, Haie-Meder Md C, Mahantshetty Md U, Jürgenliemk-Schulz Md PhD I, Lindegaard Dm DMSc JC, Pötter Md R. Image-guided Adaptive Radiotherapy in Cervical Cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2019;29:284-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/