INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the leading causes of death worldwide. According to GLOBOCAN (2022), it is the fifth most common cancer and the fifth leading cause of cancer-associated deaths in the world as well[1,2]. The incidence of GC shows geographical variation, and mortality has been in a declining trend over recent years[3-5]. However, in East Asian countries and countries with limited resources, the GC remains significantly higher. In developed countries such as the United States, nearly 26890 new cases of GC are expected to be diagnosed in 2024. Furthermore, it is more prevalent in males compared to females. The dietary habits together with genetic association, age, and infection with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) are associated risk factors for the development of GC[4]. Two histological forms of GS can be seen, such as the intestinal type and diffuse type[6]. Although the improved nutrition, availability of clean drinking water, and early identification and antimicrobial eradication treatment for H. pylori, the rate of distal GC that occurs in the antrum and body of the stomach has been reported to have declined dramatically, the rates of proximal GC and gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) cancers have been found in increasing frequency[7]. Furthermore, the overall rates of intestinal and diffuse GC have declined, and the decline is more marked for the intestinal type, which has been found more common in males, whereas the diffuse-type GC has been found equally in both sexes[7]. Despite several advancements in its diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, including surgical resection, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, GC remains a major clinical challenge worldwide, with fewer than 20% of patients surviving beyond 5 years after its diagnosis[8].

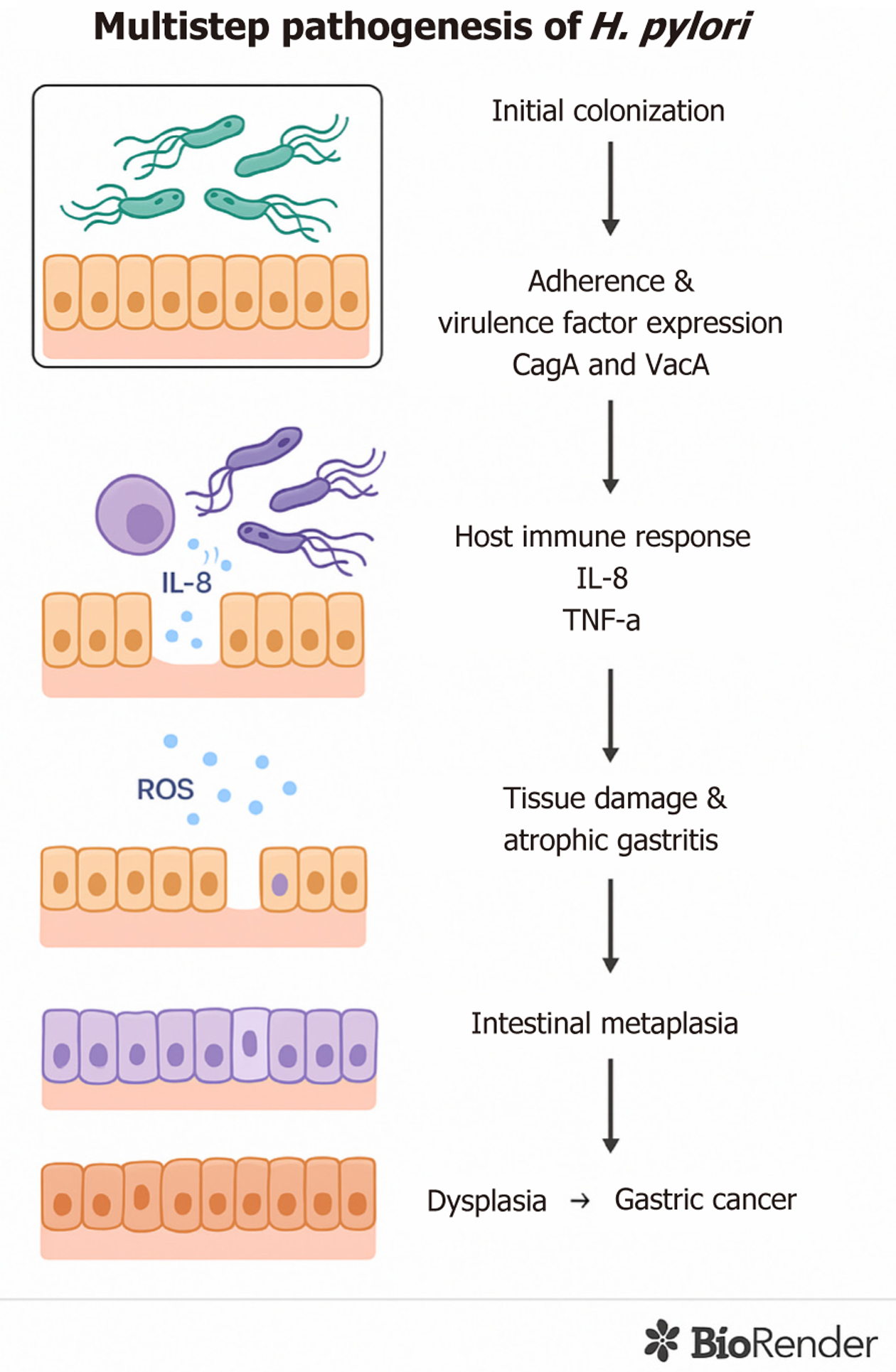

H. pylori naturally survives in the human stomach, leading to a persistent infection. It is estimated that the bacterium spreaded about 58000 years ago from East Africa to other parts of the world[9]. Thus, as an ancient microorganism, H. pylori is now widespread and estimated to colonize the gastric epithelium of at least 50% of the world’s population[10-12]. This bacterium has been recognized as a class I carcinogen and is considered the primary risk factor for the development of GC[13]. The colonization prevalence of H. pylori shows considerable geographic variation, with as high as 89.7% in Nigeria and as low as 8.9% in Yemen[10]. Socio-economic status, urbanization level, and sanitary habits during childhood have been found to affect the variation in colonization prevalence[11]. Once the bacterial colonization leading to the persistent infection is established, H. pylori causes chronic inflammation, elevating the risk of developing gastric complications such as gastritis, ulcers, GC, or gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma[14-16]. Figure 1 summarizes the multistep pathogenesis of H. pylori, highlighting the sequential events from colonization to gastric carcinogenesis. While the virulence mechanisms of H. pylori-notably CagA, VacA, BabA, and SabA, were characterized decades ago, important gaps remain. Understanding how epigenetic modifications (e.g., silencing of DNA repair genes MLH1, MGMT, and ERCC1) driven by infection contribute to gastric cancer is still at an early stage. Similarly, the significance of the gastric microbiome in promoting or inhibiting tumorigenesis is increasingly recognized but not yet comprehensively integrated. Moreover, the potential to leverage epigenetic or microbial biomarkers for risk stratification and early intervention has received insufficient attention. This review aims to provide an updated synthesis of molecular mechanisms by which H. pylori drives gastric carcinogenesis, with a focus on emerging host microbiome interactions, epigenetic dysregulation, and evolving therapeutic implications.

Figure 1 Multistep pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric cancer.

The diagram illustrates the progressive stages of Helicobacter pylori infection: From initial colonization and virulence factor expression (CagA and VacA) to activation of host immune responses (e.g., interleukin-8, tumor necrosis factor-alpha), chronic inflammation, tissue damage, atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and eventual dysplasia leading to gastric cancer. IL: Interleukin; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha; H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori.

A literature search was conducted using databases like PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar to identify relevant articles published between January 2010 and May 2025 on H. pylori, GC, CagA, VacA, programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), immune checkpoint inhibitors, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), genetic polymorphism, and single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). English-language articles were included, including peer-reviewed original research articles, meta-analyses, clinical trials, and narrative reviews. Non-peer-reviewed studies were excluded. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance and full-text assessment.

H. PYLORI COLONIZATION AND SURVIVAL IN THE STOMACH

Based on the epidemiological evidence, H. pylori infection is considered the greatest risk for the development of severe gastric complications, including GC and MALT lymphoma[7,17]. Although the exact transmission routes for H. pylori remains unclear, documented evidence suggests its transmission from person to person via fecal-oral or oral-oral routes, often occurring during childhood. Furthermore, these transmissions are regarded as the primary modes in developing countries[18,19]. Once the bacterium reaches the stomach, it localizes in the antrum and corpus regions and persists for life, establishing the chronic infection[20]. In the gastric niche, H. pylori faces a highly acidic environment. To survive, the bacterium produces urease and other adaptive mechanisms that neutralize the surrounding acid and generate an alkaline microenvironment, enabling its persistence in the stomach[21]. This adaptation mechanism of H. pylori to the adverse gastric pH involves several factors that includes bacterial properties such as urease production, recombinational repair of bacterial DNA damage, ferric uptake regulators, histidine kinase protein, helical bacterial shape, presence and the number of flagella; and gastric environmental factors such as urea, gastric mucus linings, and acidic pH have been implicated in the colonization and long-term survival of bacterial cells[22].

Urease production and the ability to harbor flagella are crucial for bacterial survival in acidic pH environments. Urease hydrolyses the urea in the stomach, resulting in the generation of ammonia and carbon dioxide, which leads to the synthesis of a neutral microenvironment for bacterial survival[22]. In addition to its optimal pH generation, urease activity has also been involved in the flagellar motility and immunological response modulation. The enzyme urease induces the release of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-8, which recruits immune cells and promotes inflammation that contributes to persistent and chronic inflammation leading to mucosal damage[23,24]. A recent article published in 2025 describes that the presence of a higher number of flagella in bacterial cells and low pH in the stomach is crucial for H. pylori survival[25]. In the article, the authors found that bacterial cells with a higher number of flagella move at a faster pace towards the low pH area that sensitizes the urea-responsive chemotactic activity, causing urea hydrolysis and creating a neutral pH around the bacterial cells[25]. The presence of flagella mediating bacterial motility facilitates bacterial penetration inside the gastric mucus, promoting colonization[26,27]. Other reports have also found the associated role of H. pylori flagella in the formation of biofilm that further protects the bacteria from antimicrobial killing in the stomach, further favoring the persistent infection[28]. Among several outer membrane proteins, BabA plays a central role in H. pylori’s adherence to the gastric epithelium, a crucial step for colonization and chronic inflammation[29,30]. Other adhesins, including SabA, OipA, and HopQ, also facilitate tight binding to the gastric mucosa, further enhancing persistence and pathogenicity[31].

Another bacterial component, 𝛾-glutamine transferase (gGT), catalyzes the hydrolysis of glutamine and glutathione, releasing metabolites such as glutamate, ammonia, and cysteinyl glycine that play an important role in the neutralization of acidic pH[32]. In a recently published article, H. pylori gGT has been found to exert a pivotal role in acid resistance, nitrogen metabolism, and iron acquisition, while its loss has been implicated in inducing several compensatory mechanisms to ensure bacterial colonization and persistence[33].

Previously, H. pylori was regarded as an extracellular organism; however, the bacterium has been found to colonize intracellularly, which could enhance its multiplication uninterruptedly. H. pylori infection has been found to induce the upregulation of progranulin (PGRN), which is a key player in various biological processes such as cell growth, survival, and inflammation. Reduction in cellular autophagy by upregulation of PGRN facilitates the survival and colonization of H. pylori inside the cells, promotes the proliferation of gastric epithelial cells, and carcinogenesis[34]. Furthermore, intracellular survival in gastric epithelial cells exhibits evasion from killing by the immune system or antimicrobial treatment, playing a major role in tumor progression[35].

VIRULENCE FACTORS OF H. PYLORI: MOLECULAR TOOLS OF PATHOGENICITY

Pathogenicity of GC development demands a complex etiology that includes the gastric environmental nature, host genetics, and microbial factors. Associated microbial factors include the virulence properties of H. pylori that are crucial and stand out as major risk factors for the development of gastric complications[11]. Numerous virulence factors are involved, starting from bacterial colonization, adaptation, and gastric survival, till the development of gastric complications. The virulence factors involved in colonization, adaptation, and survival in the gastric acidic environment have been discussed in the earlier section. The other virulence factors, such as the CagA, VacA, gene induced by contact with epithelium (iceA), and outer membrane proteins, are important for the gastric pathology[36].

The cag pathogenicity island consists of the 40kb gene cluster containing 31 open reading frames that encode the type 4 secretion system (T4SS) and the effector protein CagA that plays a key role in the development of GC and MALT lymphoma[37]. CagA consists of a 120-140 kD protein with a distinct amino-terminal region. During the gastric pathogenicity, CagA is translocated into the gastric epithelium via T4SS[38]. The CagA protein exists in two major variants: The East Asian type (EPIYA A, B, and D segments) and the Western type (EPIYA A, B, and one or multiple C segments). The East Asian variant is generally more cytotoxic and is frequently associated with regions of higher GC incidence[21].

VacA, a secreted pore-forming cytotoxin, plays a pivotal role in vacuolating gastric epithelial cells and modulating host immune responses, thereby contributing to persistent infection and carcinogenesis[39]. In addition, the protein has been found to inhibit T-cell development and proliferation, impair mitochondrial function and autophagy, and damage cell polarity[40,41]. Nearly all H. pylori strains isolated throughout the world possess vacA gene with its cytotoxic activity depending on the polymorphisms in the 3-regions namely the signal region (s) that contains 2 allele (s1 and s2), intermediate region (i) that contains 3 allele (i1, i2, and i3), and the middle region (m) that also contains 2-regions (m1 and m2)[42]. The various allelic combinations of vacA genotypes from different geographical regions influence the toxic nature of the VacA protein[43]. High vacuolization activity is found with the allelic combination of vacA s1m1, whereas moderate and minimal to absent vacuolization activity with the allelic combination of vacA s1m2 and vacA s2m2 has been found[41,44]. Additional studies have shown the association of specific vacA genotypes with an increased risk of GC development[45,46]. Furthermore, the development of intestinal-type adenocarcinoma has been associated with H. pylori with the genotype vacA i1, whereas the diffuse-type is associated with vacA d1[47]. The combination of VacA with other proteins, such as CagA, has also been found to promote the effective colonization and GC development through autophagy regulation[48,49].

Several additional virulence factors have been implicated in the progression of gastric complications. These include the high-temperature requirement serine protease (HtrA), which disrupts epithelial junctions[50], outer membrane vesicles that deliver bacterial components directly into host cells[51], and gGT, an enzyme linked to immune modulation and gastric epithelial damage. A recently published report in 2025 has suggested that the VacA protein can damage the gastric epithelia and lead to mitochondrial damage in mucus-secreting cells[52].

In a recently published report, the presence of another factor, Trx1 and RocF, has been reported to enhance the peptic ulcer and GC[53]. In the report, it was suggested that H. pylori expressing high trx1 can promote the occurrence and development of inflammation and GC by increasing the adhesion ability of the bacterium and could also enhance the activation of IL23A/NF-κB/IL17A, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), IL-6, and IL-8[53]. Protein Trx1 acts in stress response that can be excreted by the bacterium and post-translationally stimulates the arginase (RocF), and its activity is increased[54].

H. PYLORI IN GASTRIC CARCINOGENESIS

According to the published reports, GC is the fifth most diagnosed cancer worldwide, with the leading cause of cancer-related deaths[1]. H. pylori infection has been associated with 89% of non-cardia GC and has been documented as a major risk for developing GC[55]. The available report suggests that approximately 4.4 billion people are infected with this bacterium worldwide, making it the most common infection[10]. However, only a small number of infected individuals develop GC through the histological multi-step process of the “Correa Cascade”, from chronic inflammation to atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and finally adenocarcinoma[56,57]. Although the development of GC takes several years, more than 80% of GC cases are diagnosed at later stages only due to its asymptomatic nature, and despite several advancements in surgical resection, eradication, and chemotherapeutic treatments, the 5-year survival rate for GC remains below 20%-30%[9,13,58,59]. According to a report, over 1 million new cases of GC were diagnosed in 2020 alone, with approximately 770000 deaths worldwide. China contributes the highest proportion of GC cases, as nearly half of the global burden of GC is concentrated in China only, where 478000 new cases were reported[60]. Although H. pylori is documented as the major risk factor, the likelihood of GC progression depends on several other factors, such as the virulence potential of the bacterial strains, host genetic predispositions, environmental factors in the stomach influenced by diets, as well as the changes in stem cell populations and gastric microbiome populations.

H. pylori colonizes the gastric epithelium, and it produces the effector protein CagA, which is translocated inside the gastric epithelium via T4SS. Once the CagA is internalized in the gastric epithelium, it leads to a morphological alteration to the gastric epithelium known as “hummingbird phenomena”, characterized by the elongation of the cells[42]. The protein CagA undergoes its phosphorylation by host c-SRC and c-ABL tyrosine kinases at the specific regions, EPIYA-sequences[61]. The phosphorylated CagA through these EPIYA-sequences enables it to interact with SHP2, which triggers the downstream signaling cascades that possess multiple influencing effects on the host epithelial cells[62-64]. These effects include cytoskeletal rearrangements, epithelial cell apoptosis inhibition, disruption of intercellular junctions, and EMT leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation. Subsequently, several other studies have reported additional alterations to the host cells that include loss of cellular polarity[65], increased cell motility[66-68], cell scattering[68-70], cell proliferation[70,71], cell invasiveness[65], and disruption of epithelial barrier functions[21]. CagA, either in its phosphorylated or non-phosphorylated form, interacts with at least a dozen intracellular proteins inside host cells, leading to several effects of this H. pylori protein relevant for its oncogenic potential[72,73]. Additionally, CagA has been found to induce inflammatory signaling pathways resulting in the recruitment of inflammatory cells and an altered immune microenvironment, leading to the recognition of the oncogenic potential of CagA[74].

H. pylori producing the East Asian type of CagA has been found to demonstrate enhanced dysregulation of intracellular signaling, especially more severe intracellular hypoxia and higher levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS)[75]. Although the CagA with the EPIYA-C sequence is considered non-virulent or less virulent, as the number of EPIYA-C sequences increases, the virulent potential of CagA is also increased. In addition to these functional abilities of CagA protein, recently it has been elucidated that H. pylori CagA can induce upregulation of squalene epoxidase that promotes the progression of GC, leading to an enhanced effect on PD-L1 palmitoylation and an inhibiting effect on ubiquitination. These processes consequently lead to the inhibition of T-cell activity, facilitating the immune evasion mechanism within GC[76].

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are tumor-initiating cells that constitute a distinct population of cells residing within the tumor microenvironment. CSCs are characterized by the ability to self-renew and generate diverse tumor cells. These CSCs exhibit markedly enhanced carcinogenicity relative to non-CSCs, which play a pivotal role in facilitating the initiation and advancement of tumors[77]. A recent publication elucidates that the CagA proteins produced by H. pylori possess the potential to activate the PI3K/AKT pathway that leads to the transcriptional inactivation of intracellular FOXO3a phosphorylation and the induction of features resembling gastric CSCs[78]. The net effect leads to enhanced tumorigenesis with H. pylori infection.

Even after successful H. pylori eradication, a population of gastric epithelial cells with stem-like features-characterized by markers such as Lgr5, CD44, or CD166-may persist, fueled by activation of NF-κB, Wnt/β-catenin, Hippo/YAP, and STAT3 pathways that were triggered during infection and remain afterwards[79]. To reduce the risk of recurrence, novel strategies that target these residual CSCs are increasingly important. Experimental approaches include using smallmolecule inhibitors of these key pathways (e.g., blocking Wnt/β-catenin or NF-κB signaling) to impair CSC self-renewal, as well as autophagy inhibitors that have been shown to decrease CD44-positive spheres and reduce survival under stress[17]. In addition, targeted delivery systems such as nanoparticles, designed to recognize CSC markers or deliver modulators of stemness-related non-coding RNAs, are being explored to selectively eliminate residual CSCs[80]. Finally, emerging immune-based therapies-including CSC-focused vaccines, antibody-drug conjugates, and CAR-T cell constructs-show promise for enhancing immune clearance of these cell populations. Together, combining H. pylori eradication with CSC-directed therapies offers a more comprehensive approach to preventing GC relapse by eliminating the stem-cell “seeds” that may otherwise endure.

It has been reported that H. pylori infection can induce double-stranded breaks (DSBs) in gastric epithelial cells. This genotoxic capability is primarily attributed to the cag-PAI that encodes for T4SS and effector protein CagA[81]. The H. pylori-mediated DSBs can induce copy-number variation and transcriptional changes at GC driver genes that initiate GC tumorigenesis[82]. Acrolein, which is a highly reactive aldehyde, has been found to induce genomic stability[83]. In a recent report, the authors found that acrolein, a byproduct of spermine oxidase activity, in response to H. pylori infection, can induce DNA damage in gastric epithelial cells, leading to a carcinogenic potential[84].

H. pylori, through its CagA protein, has been shown to impair the epithelial barrier, targeting the epithelial junctional complexes and cell polarity[85]. In addition, this bacterium, producing a virulence factor HtrA, has been demonstrated to impair cell adhesion by cleaving the extracellular domains of tight junctional proteins occludin and claudin as well as adherence junctional protein E-cadherin[86,87].

In a recently published report, H. pylori has been demonstrated to decrease ion transport protein, Na and K-ATPase, activity and its abundance in gastric epithelial cells[64,88]. Na+/K+-ATPase, ion transport proteins which are critical for the generation of the ion gradient and for cell adhesion[89]. The inhibition or complete absence of Na and K-ATPase impairs the cellular barrier function in the stomach. H. pylori has been reported to induce reduced expression and activity in the cellular plasma membrane. The reduced Na+/K+-ATPase activity, together with other H. pylori virulence factors such as CagA and HtrA, might contribute to the damaging effect on the epithelial barrier, leading to the inflammation and erosion of the protective epithelial linings in the stomach[90].

Growth factor receptor-bound protein 7 (GRB7) has been reported to enhance oncogenic signals that promote cancer development[91-94]. Its upregulation has been well correlated with cancer development and has been found in breast cancer, bladder cancer, ovarian cancer, oesophageal cancer, and even in GC[91,93,95], H. pylori infection has been shown to induce STAT3 activation that leads to increased GRB7 expression, promoting the activation of the ERK pathway. The overall process results in increased cell proliferation, migration, and invasion that might lead to gastric carcinogenesis[96]. Numerous cellular signaling pathways are activated by persistent H. pylori infection, including TGF-β, Wnt, and Hippo pathways during the precancerous phase, inducing stem cell-like properties in gastric epithelial cells that fuel the gastric cell proliferation and tumorigenesis.

EMT is an important cellular process where the epithelial cells are fully or partially converted to mesenchymal-like cells, which occurs during embryogenesis or in response to tissue injury. EMT also plays a key role in cancer development and progression as well as in organ fibrosis[97]. The cleavage and degradation of E-cadherin at the plasma membrane, which is found during EMT, may lead to damage to cellular adhesion junctions in the gastric epithelia. Elevated levels of TGFβ1 have been reported to promote epithelial plasticity and the progression towards EMT during cancer progression[98]. A recent study has also suggested novel evidence that H. pylori induces the upregulation of TGFβ1 through hexokinase domain-containing 1, leading to progression towards EMT. The overall process thereby plays a crucial role in the pathogenicity of gastritis and GC[99].

Programmed cell death (PCD) is a genetically programmed suicidal mechanism, such as apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis, that leads to the killing of the targeted cells[93,100]. PCD plays a crucial role in maintaining the body’s cellular homeostasis, which keeps it in a stable state. However, certain infections, including H. pylori infection, can disrupt the normal process of PCD, leading to an unbalanced internal environment and probably an induced stimulation for gastric carcinogenesis[101]. H. pylori in its early stage of infection can induce the expression of PD-L1 on gastric epithelial cells, which interacts with programmed death 1 on the surface of cytotoxic T-cells, diminishing activation of PCD[102,103]. Diminished PCD leads to the survival of H. pylori-infected cells protected from the immune response and programmed death[104]. Furthermore, visible damage to both the superficial epithelial cells and the cells that form the pits and glands in the stomach can be triggered by bacterial or PCD-mediated mechanisms, leading to an irreversible loss of functional cellular architecture known as atrophy, which is thought to be an initial stage of GC development in the Correa cascade[101]. Furthermore, several intracellular signaling pathways such as MAPK, NF-κB, and PI3K are triggered by H. pylori infection, which in turn leads to proliferation, differentiation, and PCD, inducing a carcinogenic potential to the gastric epithelium[105,106]. It has been reported that the chronic inflammation-derived cytokines play a critical role in promoting the neoplastic proliferation within the GC microenvironment[107]. During chronic infection, H. pylori infection through its virulence factor CagA protein engages with gastric cell membrane receptors and activates the NLRP3 inflammasome, triggering the pyroptotic signalling cascades. The activated signaling cascade results in the substantial release of cytokines, including IL-18, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α, that collectively create a pro-tumorigenic microenvironment that promotes cancer cell proliferation and metastasis[108,109].

The oxygen level in the gastric territory has been found to correlate with carcinogenesis. The oxygen level with an oxygen partial pressure of 7.73 kPa is found in the stomach, whereas its level goes further beyond, and it becomes anaerobic in the gastrointestinal lumen[90,110,111]. A recent report highlights that prolonged exposure of gastric epithelia to H. pylori under a diminished oxygen environment may stimulate cellular proliferation, lower cellular apoptosis, and induce EMT. All these processes are promotive for H. pylori infection and induced gastric carcinogenesis[112].

Non-coding RNAs play a critical role in several biological processes. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are non-coding RNAs ranging from 17 to 25 nucleotides, and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a novel type of non-coding RNA that is longer than 200 bp[113]. These non-coding RNAs regulating protein-coding gene expression play a crucial role in the regulation of several cellular processes, including cell development and growth, the cellular cycle, and cancer metastasis[114]. Therefore, dysregulation of these non-coding RNAs (either miRNAs or lncRNAs) has been implicated in several human diseases[115]. An altered miRNA expression profile contributing to GC development has been correlated with H. pylori infection[116,117]. Moreover, various lncRNAs such as TERRA, HOXA11-AS, HOTAIR, PTENP1, and H19 are dysregulated in GC and have been suggested to be effective biomarkers for several gastrointestinal diseases, including GC[118,119]. H. pylori infection has been found to alter the expression of miRNAs and its involvement in gastric carcinogenesis[120]. Accumulated evidence from several studies has found the critical roles of miRNAs in carcinogenesis[121-123]. Similarly, the evidence has also suggested a direct correlation between lncRNAs expression and progression from inflammation to GC in patients with atrophic gastritis[120,124].

Emerging studies demonstrate that H. pylori infection disrupts multiple miRNAs. Upregulation of miR-155 via NF-κB suppresses anti-inflammatory mediators, while miR-21 promotes oncogenic pathways by inhibiting PDCD4 and PTEN. Conversely, downregulation of tumor-suppressive miRNAs like miR-146a and miR-140 is linked to increased inflammation and immune evasion through PD-L1 modulation. Exosomes carrying miR-362-5p have also been shown to promote proliferation and migration via TLE4 suppression-providing a mechanistic link between infection and tumor behavior[121,125]. Several lncRNAs-including H19 and MIR22HG-emerge as regulators of oncogenic signaling pathways such as Wnt and STAT3. These lncRNAs have correlations with tumor stage and prognosis in GC, and their infection-induced dysregulation suggests potential for use as predictive biomarkers or molecular targets in future therapies[125].

GENETIC AND EPIGENETIC LANDSCAPES

Genetic polymorphisms’ effects on immunological response

Several studies have examined the impact of host genetic polymorphisms on immune response molecules, such as pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), toll-like receptors (TLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and cytokines, during H. pylori infection.

TLRs

TLRs are a class of PRRs expressed on immune and epithelial cells, responsible for recognizing microbial products known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)[126]. These molecules are essential for initiating innate immune responses. H. pylori expresses various PAMPs recognized by TLRs. For instance, H. pylori lipopolysaccharide binds to the TLR2 receptor and induces chemokine expression in gastric epithelial cells. Heat shock protein 60 (HSP60), another PAMP, has been shown to stimulate IL-8 production via TLR2 and TLR4 pathways in gastric adenocarcinoma epithelial cells[127]. In response to infection, gastric epithelial tissues-particularly in children-upregulate TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, and TLR9, along with pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α.

Genetic polymorphisms in TLR genes have been linked to host susceptibility to H. pylori-associated GC. For example, a SNP in TLR4 (rs11536889) has been associated with an increased risk of gastric carcinogenesis[128]. A case-control study and meta-analysis identified individuals carrying the TLR4 rs11536889 T allele and the TLR2 -196 to -174 deletion allele as having significantly higher GC risk. In a Chinese population, minor alleles of TLR5 rs5744174, TLR9 rs1640827, and TLR9 rs17163737 were significantly associated with elevated GC risk[129]. These polymorphic variants may influence the host's inflammatory response and susceptibility to disease progression. For example, in a study among Indian Tamil patients, TLR5 rs2072493, TLR5 rs5744174, and TLR5 rs5744168 were not significantly associated with chronic H. pylori infection. However, the C allele of TLR5 rs5744174 was found to be linked to an increased risk of gastric atrophy and hyperchlorhydria in infected individuals[130]. Similarly, in a Mexican study involving 561 patients, the TLR9 2848A allele (corresponding to rs352140) was associated with a higher risk of duodenal ulcer formation, while no significant associations were identified for TLR5 polymorphisms in that population[131].

NLRs

NLRs are PRRs that activate innate immune responses via the cytosolic sensing of microbial components. There are over 20 members of the NLR family, and some respond to various PAMPs, non-PAMP particles, and cellular stress to trigger pro-inflammatory responses, including the secretion of IL-1β. NLRs are part of inflammasomes, which induce the maturation of inflammatory cytokines in response to infection. Two such NLR family members, including NOD1 and NOD2, are activated by molecules produced during bacterial peptidoglycan synthesis and degradation. They can activate NF-κB in response to peptidoglycan fragments[132,133]. Although H. pylori is known for its helical shape, the organism can also take on coccoid forms, and it has been demonstrated that AmiA, a N-acetylmuramoyl-alanine L- L-amidase, is necessary for both this morphological change and a modification of the cell wall peptidoglycan. This alteration in cell wall peptidoglycan makes it possible to evade immune system identification, a mechanism that may encourage persistent infection[133].

Cytokines

The production of IL-1β can be inhibited by the IL-1 receptor antagonist IL-1RN. Inflammation and GCs develop in transgenic mice that overproduce IL-1β[134]. IL-1β has three SNPs on chromosome 2q14, leading to its overexpression[135]. Research has indicated that pro-inflammatory IL-1 Loci had a higher chance of developing GC and a chronic hypochlorhydria reaction to H. pylori infection[135]. In Northern Portugal, individuals homozygous for the IL-1RN*2 allele have a substantially increased risk of gastric carcinoma. Studies have shown an association between IL-1β polymorphisms and GC susceptibility in Asian and Latin American populations[136]. A recent meta-analysis study suggested that the IL-1β-31 polymorphism increases susceptibility to GC in H. pylori infection. Susceptibility to GC is positively correlated with Asian ethnicity, H. pylori infection, and IL-1β-511 C/T SNP. In Brazilian communities, GC development in H. pylori-infected patients and chronic gastritis is linked to IL-1β-511 CC and CT gene polymorphisms[137].

The gastric mucosa of people with H. pylori infection has higher levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α. The expression of this cytokine is influenced by five biallelic SNPs located in its promoter region. Those who carry the TNF-α308A allele are more prone to develop gastric cirrhosis. However, no combination of TNF-α-308 and bacterial genotypes was shown to significantly enhance the risk for carcinogenicity. Noncardia gastric cirrhosis risk is doubled in those with pro-inflammatory TNF-α and IL-10 genotypes[138]. TNF-α-308/-238 GA/GG, AA/GG, and AA/GA genotypes were found to raise the incidence of stomach ulcers in a Chinese study. First-degree relatives of patients with gastric ulcers who had TNF-α G308 polymorphisms were more prone to developing gastric ulcers in comparison to second-degree relatives. Polymorphisms in TNF-α have also been associated with peptic ulcer disease, with high-producer alleles of TNF-α increasing the risk of both gastric ulcers and gastric cirrhosis compared to H. pylori-negative controls[139].

Genetic polymorphisms that alter the production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines likely mediate the immune response and development of gastritis after H. pylori infection. Studies have shown controversial results regarding the role of polymorphisms in IL-2. Some studies have found that the IL-2T-330G polymorphism is associated with an increased risk of gastric atrophy, a precursor of gastric ulcer disease induced by H. pylori infection. Others found that carriers of the IL-2-330T/G polymorphism had a decreased risk of infection and increased IL-2 and IFN-γ levels, suggesting that they might be protected against H. pylori infection in adulthood[140]. A case-control study in Chinese subjects found that the IL-6 rs1800796 CG genotype was associated with a decreased risk of GC in males[140].

Hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoters

GC is a type of human cancer in which abnormal methylation of the promoters of CpG islands is common[141]. Hypermethylation of CpG islands in the promoters of tumor suppressor genes (or tumor-related genes) is an important mechanism for gene inactivation, and it replaces the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes and cancer-related genes in human cancer, regardless of the tissue type[142]. Several studies have shown that increased hypermethylation in several CpG island locations in the gastric mucosa of H. pylori-infected patients is one of the mechanisms of gastric carcinogenesis[143]. During H. pylori infection, some proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8, are increased in the gastric mucosa and help initiate and regulate the inflammatory response to H. pylori infection[144]. IL-1β and IL-6 can increase the expression and activity of DNA methyltransferase 1, which is involved in transferring a group of methyl groups from S-adenosyl methionine to cytosine in CpG, hence regulating the CpG island's hypermethylation[145]. Several SNPs in these proinflammatory cytokine genes influence their expression. The IL-1B gene contains two diallelic SNPs in the promoter region at positions -511 and -31 base pairs from the transcriptional starting point, which modulate IL-1β levels in the gastric mucosa associated with H. pylori infection[146]. There is significant variability in the number of hypermethylated CpG island loci in patients with chronic gastritis who are H. pylori-positive. This variation may be influenced by several factors, including the virulence of the bacteria, duration of H. pylori infection, and genetic aspects of the host[120]. The IL-1β-511T/T allele was linked to increased hypermethylation across several CpG island loci, with higher methylation of CpG island loci per sample, which may lead to a higher likelihood of developing GC in those infected with H. pylori and possessing the IL-1β-511T/T allele[146].

Integration of bacterial virulence and host genetics

H. pylori poses a unique risk due to a two-way interaction between bacterial virulence and host susceptibility. Infected individuals with CagA-positive strains, particularly those carrying the oncogenic cag pathogenicity island, show stronger NF-κB activation and chronic inflammation[147]. This is further amplified in hosts with certain IL-1B polymorphisms, which boost IL-1β production, a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine linked to gastric epithelial hyperproliferation and tumor formation[148]. Combinations of SNPs across genes like IL-1B, PTPN11, and PGC significantly influence susceptibility to H. pylori infection. A case-control study found that certain interactions can shift risk depending on infection status, potentially turning protective effects into elevated cancer risk. This highlights how host genetic context can modify bacterial virulence impact[149]. This highlights how host genetic context can modify the impact of bacterial virulence.

Variants in TLR4, especially Asp299Gly and Thr399Ile, alter the receptor’s response to bacterial LPS and may impair proper immune activation. Meta-analyses report that minor alleles in TLR4 SNPs, including rs1057317, are associated with increased vulnerability to H. pylori-related GC, likely through dysregulated innate immunity and aberrant cytokine signaling[150]. The study indicates that infection outcomes and cancer risk are interconnected, with a pro-inflammatory bacterial strain in a genetically predisposed individual potentially leading to gastritis, atrophy, metaplasia, and ultimately malignancy, which could aid in identifying high-risk patients requiring aggressive surveillance or early eradication therapy.

Role of the gastric microbiome

Gastrointestinal microbial diversity and its populations (microbiomes) are crucial for maintaining homeostasis and disease development. The colon is a widely studied human microbial ecosystem, and the gastric microbiome plays a significant role in gastric carcinogenesis[151]. Using culture-dependent techniques, Veillonella, Lactobacillus, and Clostridium spp. were the most isolated bacteria from the human stomach[152]. Recent advances in technology, including next-generation sequencing, microarrays, and random shotgun sequencing, have led to the discovery of numerous bacterial species. Compared to the intestine (1010-1012 CFU/mL), the stomach has a substantially lower microbial burden (102-104 CFU/mL)[153]. Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Fusobacteria have been described as the most prevalent phyla in the stomach mucosa[153]. The mechanisms influencing the variations in gastric microbiome composition in different individuals are not yet fully understood. However, several factors, such as the method of delivery, age, gender, ethnicity, diet, lifestyle, location, consumption of antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), and H. pylori infection, can affect the microbiome composition. Healthy stomachs prevent bacterial over-proliferation, whereas long-term treatment reduces gastric acid secretion, leading to bacterial overgrowth. However, the organization of the stomach microbial population is unaffected by genetic background[154].

The ecology in the stomach can be altered by most H. pylori strains, which changes the habitat of the bacteria that reside there[155]. This change in stomach microbiota composition may increase the risk of GC. Patients who tested negative for H. pylori had a more varied stomach microbiome than those who tested positive, according to a barcoded pyrosequencing examination of patients with and without infection. According to an additional study, children with H. pylori infection exhibited lower alpha diversity than those without the infection[156,157]. Increased microbial diversity in the stomach has been associated with the elimination of H. pylori. Microbial diversity and H. pylori abundance are inversely correlated with the phases of gastric carcinogenesis. Though both patients with and without H. pylori had the same major phyla: Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Fusobacteria; their proportions differ between H. pylori-positive and H. pylori-negative patients[158]. H. pylori infection is associated with continuous inflammation of the gastric mucosa, alters the cell cycle of gastric epithelial cells, ultimately leading to intestinal metaplasia, gland atrophy, and GC. Despite the increasing number of studies investigating microbial dysbiosis (alterations in the content and function of the microbiome) during gastric carcinogenesis, there is still disagreement over the pattern of gastric microbiome alteration. According to certain studies, cancer and inflammatory illnesses significantly lower microbial diversity[159]. GC has been found to have varying bacterial richness and diversity, with some studies showing increased diversity in the advanced stage of GC compared to that in early stages. However, bacterial diversity decreases gradually from healthy controls to GC, with some studies showing increased diversity in the advanced stage[160]. Microbial diversity also varies between the early- and late-stage of GC, with some studies showing reduced diversity in tumor-associated tissues. Recent studies have revealed the microbial composition in different GC subtypes, with Fusobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Patescibacteria enriched in signet-ring cell carcinoma and Acidobacteria and Proteobacteria enriched in adenocarcinoma[161].

Microbiome homeostasis is determined by microbial interactions, which also affect the microenvironment linked to disease. The lower abundance of H. pylori is thought to be the reason for the decreased complexity of the microbial interaction network in GC[161,162]. According to other studies, a higher abundance of other microbes combined with a decrease in H. pylori abundance may be the cause of the more complicated interaction network in GC[163].

ANCESTRAL INTERACTIONS: HUMAN-MICROBIAL CO-EVOLUTION AND CANCER RISK

Approximately half of the world's population has H. pylori colonizing their gastric mucosa. Only a small percentage (< 1%) of infected individuals develop gastric adenocarcinoma, which accounts for 10% of all cancer-related deaths globally, despite all infected individuals having stomach inflammation[162]. The occurrence of severe clinical sequelae is typically not predicted by the prevalence of H. pylori infection in a population, indicating that genetic variations in the pathogen and host, as well as dietary and other environmental factors, are significant contributors. However, the heterogeneity in infection outcomes has not been sufficiently explained by these parameters when examined separately[163].

Chronic infections that are transmitted vertically or familially, such as H. pylori, are predicted to become less virulent over time according to both evolutionary theory and empirical comparisons[164]. Most of the H. pylori infections are well tolerated by people; in most adult carriers, they only cause mild inflammation and may even offer some protection against oesophageal diseases and asthma[17]. However, H. pylori can also spread horizontally, particularly in poorer nations where poverty is widespread[165]. Multiple-strain infections may be more prevalent in these circumstances than in industrialized nations. Because H. pylori is highly recombinogenic, infection with numerous strains can disrupt the selection for lower virulence by causing horizontal gene transfer of segments that have not co-evolved with their hosts. Therefore, the human and H. pylori connection may be less likely to reflect a co-adapted, reduced-virulence complex in areas where humans are highly admixed, such as South America. The study investigated human and pathogen ancestry in matched samples to determine whether their genetic variation influences the severity of premalignant lesions in two different Colombian communities with similar levels of H. pylori infection but varied occurrences of GC[166]. Spatial difference in clinical presentation was explained by the interaction between H. pylori African ancestry and Amerindian heritage. The study concluded that co-evolutionary relationships are important determinants of gastric disease risk and that the historical colonization of the Americas continues to influence health in modern American populations[165]. This study also suggested that the disruption of co-evolutionary relationships between humans and H. pylori may reflect the continued legacy of European colonization. The study concluded that human and H. pylori ancestry are associated with histopathology, and the relationship between human and H. pylori ancestry is complex[166]. As a result, co-evolution probably may have influenced disease risk, and the increased prevalence of stomach disorders in the mountain population can be explained by the disruption of the co-evolved human and H. pylori genomes[166].

According to Kodaman et al[165], the idea of host–microbe co-evolution shows that a higher risk of stomach cancer is linked to mismatches between host ancestry and H. pylori strain lineage. The balance between host tolerance and pathogen virulence is disrupted by this ancestral mismatch, which can accelerate neoplastic transformation[165]. The potential for ancestry-guided screening procedures to increase early detection rates in high-risk groups should be examined in future research. For instance, people with a high-risk mismatch profile who might profit from early endoscopy or H. pylori eradication techniques may be found using genetic ancestry profiling along with bacterial genotyping[166]. A promising path for stratified screening and prevention of stomach cancer is offered by the combination of evolutionary biology and precision medicine.

CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS AND PREVENTION

The prevention of GC, especially in areas with a high frequency of infection, depends heavily on the clinical management of H. pylori. A fundamental technique for lowering the burden of GC is early intervention targeting H. pylori, as it continues to be a prominent cause of cancer mortality worldwide[167]. In the general population or patients with early gastric neoplasia, screening for and treatment of H. pylori may lower the incidence and mortality rates of GC[168]. Non-invasive screening techniques provide an efficient and financially acceptable public health strategy in high-risk areas like East Asia, where the incidence of gastrointestinal cancer and H. pylori prevalence are both much higher. According to research, test-and-treat methods that use stool antigen testing or the urea breath test (UBT) in asymptomatic persons can lower the long-term risk of GC while still being affordable[168]. For example, a meta-analysis conducted by Lee et al[169], showed that eliminating H. pylori was linked to a noticeably decreased incidence of stomach cancer, especially when it was done as part of nationwide screening campaigns[169]. UBT or serological testing has already been incorporated into routine health examinations in nations like South Korea and Japan, which have implemented population-based screening policies. In light of these results, we advise that such test-and-treat approaches be considered in additional high-burden contexts; ideally, they should be incorporated into community-based health programs or primary care systems to optimize accessibility and impact[170]. Both stool antigen evaluation and the UBT are beneficial for diagnosis and monitoring following eradication treatment. The stool antigen test is more economical than the UBT while maintaining similar levels of sensitivity and specificity. Non-invasive methods are not capable of diagnosing complications associated with H. pylori infection[168].

Patients with H. pylori infections can currently receive treatment through various antibiotic combinations. The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines recommend standard triple therapy-comprising a PPI, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin administered for 10-14 days-as a first-line approach for H. pylori eradication. However, in recent years, increasing global rates of clarithromycin resistance have significantly reduced the effectiveness of this regimen[171]. While data on clarithromycin resistance in some populations are somewhat scarce, estimates suggest that resistance may reach as high as 50% or beyond in other populations[172]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for alternative treatment regimens to combat the growing resistance to clarithromycin. The sequential therapy regimen involves 5 days of PPI and amoxicillin, followed by 5 days of PPI with metronidazole and clarithromycin. This weakens the bacterial cell wall, allowing metronidazole and clarithromycin to act directly on the bacterial cell and prevent antimicrobial efflux. The newer therapeutic regimen for H. pylori infection includes a non-bismuth quadruple therapy, such as a PPI with amoxicillin, metronidazole, and clarithromycin (PAMC)[173]. The Cochrane database suggests 14 days therapy is ideal, resulting in higher eradication rates and a 0.66 relative risk of H. pylori persistence. Guidelines have been proposed to address global clarithromycin resistance, recommending 14 days of PAMC therapy or bismuth-based quadruple (PBMT; PPI, bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline) therapy[168]. Bismuth-based quadruple therapy offers improved efficacy in resistant strains but is often limited by side effects and poor patient adherence[168]. Although eradicating H. pylori still faces significant challenges due to clarithromycin resistance, recent focus has shifted to other treatments that might be able to overcome this barrier. Using silver ultra-nano clusters (SUNCs) along with metronidazole is one promising strategy[174]. By disrupting membranes and producing ROS, these tiny particles demonstrate antibacterial qualities that could potentially increase the effectiveness of traditional antibiotics. Crucially, a number of investigations have revealed that this combination exhibits significant efficacy against H. pylori strains that are both antibiotic-naïve and clarithromycin-resistant[169]. SUNCs and metronidazole together has been found to produce a higher eradication rate in vitro, even in strains that had been shown to be resistant to clarithromycin. This implies that in circumstances where medication is not working, SUNCs could be a useful supplement or alternative. Emerging therapies such as SUNCs in combination with metronidazole show in vitro efficacy against resistant H. pylori strains, but clinical data remain sparse[175]. Overall, the therapeutic landscape lacks a one-size-fits-all solution, highlighting the need for personalized treatment approaches guided by resistance profiling and host–pathogen interaction markers. Future studies are necessary to evaluate safety, the best dosage, and long-term results, especially in resistant groups, as clinical validation is still lacking[169]. Strong comparison evidence in both treatment-naïve and resistant cohorts will be necessary to incorporate such medicines into current guidelines[176].

A number of novel therapeutic modalities are being researched in addition to immunotherapy and well-established regimens. To combat the escalating problem of antibiotic resistance, these strategies include bacteriophage therapy, the use of antimicrobial peptides, and delivery methods based on nanoparticles. In vitro and in animal models, antimicrobial peptides like LL-37 and cathelicidin have demonstrated bactericidal action against H. pylori, and nanocarriers may enhance medication delivery and lessen damage to the stomach mucosa. Moreover, vaccine development is still a challenging but promising field[177]. Preclinical models have shown the immunogenicity of several experimental vaccines, such as DNA-based, live attenuated vector platforms, and recombinant subunit vaccines. However, inconsistent protection and a weak mucosal immune response have hindered human trials. Children in China who received an oral recombinant urease B subunit vaccination during a phase III study demonstrated a moderate level of protection; however, the results have not been consistently replicated[178]. Particularly in endemic areas, sustained investment in vaccine development may eventually provide a prophylactic measure[22].

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Molecular studies have revealed various molecular landscapes underlying GC development; however, the cellular diversity and intercellular interactions driven by H. pylori infection in the Correa cascade remain poorly understood. Single-cell transcriptomic profiling showed enhanced cell-cell interactions and activation of the TNF, secreted phosphoprotein 1, and thymus cell antigen 1 signaling pathways. Further research is needed to develop effective measures to prevent gastric carcinogenesis[179]. As our knowledge of these pathways grows, identifying individuals at a higher risk of developing stomach cancer should be the main focus of targeted treatment and prevention initiatives. Furthermore, genome-wide association studies have been demonstrated to be useful in locating the SNPs in H. pylori linked to GC. The risk of GC can be categorized based on H. pylori SNPs. However, further research is needed to understand how the detected high-risk SNPs affect stomach cancer development using functional studies[17]. The development of novel preventative methods, including immunization to avoid H. pylori infection and related GC, would be significantly impacted if this concept is validated. Future studies should focus on the following: (1) Clarifying the exact processes through which the virulence factors of H. pylori interact with host cells to cause carcinogenesis; (2) Examining how bacterial genotypes significantly affect the course of the disease and how well a treatment works; (3) Investigating the intricate relationships between H. pylori and the human immune system, particularly in the context of immunotherapies for cancer; (4) Using the molecular pathways that H. pylori dysregulates to develop new therapeutic targets and immunotherapies; and (5) Recent data indicate that H. pylori can cause PD-L1 expression in gastric epithelial cells, especially through its virulence component CagA, which helps tumor cells evade the immune system. This process offers a compelling justification for assessing immune checkpoint drugs that target the PD-1/PD-L1 axis in GC linked to H. pylori. Numerous immunotherapy trials demonstrate potential in this respect. The effectiveness of nivolumab, a PD-1 inhibitor, in conjunction with mFOLFOX6 chemotherapy, for instance, is being studied in the ongoing phase II clinical trial NCT04684459 in patients with advanced gastric or GEJ cancer. The study classifies patients based on H. pylori status, suggesting it could be a predictive biomarker for immunotherapy response. This underscores the need to explore H. pylori-driven immunosuppressive pathways for understanding pathophysiology and developing effective immunotherapeutic strategies[180]. Developing innovative preventive measures, such as more potent eradication treatments and immunization programs, to reduce the incidence of H. pylori-associated GC worldwide[180].

Future research on H. pylori-associated gastric carcinogenesis should use integrative multi-omics approaches like transcriptomics, epigenomics, and microbiome profiling to identify early molecular events and predict biomarkers. Single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics can reveal heterogeneity in host responses, while CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing and organoid models can validate key genes involved in tumor progression[181]. Longitudinal human cohort studies stratified by strain type, host genetic polymorphisms, and immune profiles will help understand disease trajectories. Machine learning algorithms can predict treatment outcomes and design personalized eradication or immunotherapy regimens.

CONCLUSION

This review summarizes the state of knowledge about the role H. pylori plays in the development of GC, emphasizing the intricate interactions among host immune responses, genetic predispositions, environmental variables, and bacterial virulence factors. Even though a lot has been discovered, there are still significant gaps between practical application and mechanistic findings. More than just a deeper understanding will be needed going forward to translate these findings into significant clinical outcomes; novel tools like organoid models, multi-omics integration, and biomarker-driven trials will be needed. Additionally, we see promising prospects in fields like immunotherapy and individualized treatment plans. The field can get closer to better prevention, early detection, and customized treatments for H. pylori-associated GC by concentrating future research efforts in these domains.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors want to thank the organizations that provided support and facilities.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: United Arab Emirates

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade A, Grade A, Grade B, Grade C

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: Al-Shimmary SMH, Assistant Professor, PhD, Iraq; Ren SQ, MD, China S-Editor: Liu H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang YL