Published online Dec 24, 2025. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v16.i12.110351

Revised: July 5, 2025

Accepted: November 11, 2025

Published online: December 24, 2025

Processing time: 201 Days and 20.7 Hours

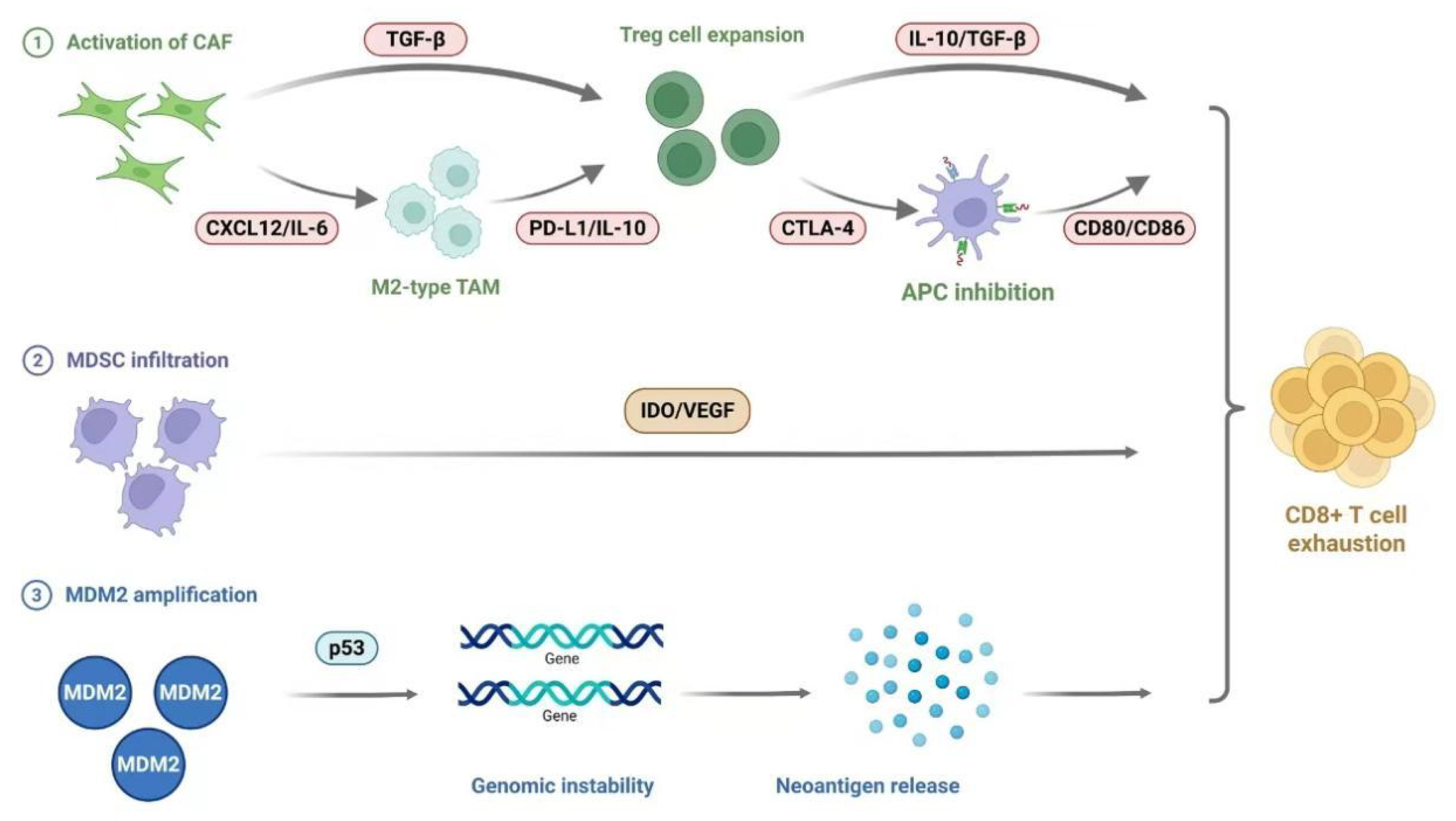

Programmed death receptor-1 inhibitors have significantly improved the prog

Core Tip: Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced hyperprogressive disease represents a paradoxical clinical phenomenon characterized by accelerated tumor progression mediated through complex immunosuppressive mechanisms involving regulatory T cells expansion, M2-type tumor-associated macrophages polarization, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells accumulation within the tumor microenvironment, coupled with oncogenic alterations such as MDM2 amplification and EGFR activation. Current predictive approaches integrate liquid biopsy profiling (e.g., circulating tumor DNA and blood tumor mutational burden dynamics) with systemic inflammatory markers (e.g., neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and lactate dehydrogenase ratios), while emerging therapeutic strategies focus on combinatorial approaches targeting immunosuppressive networks, metabolic reprogramming, and checkpoint inhibition. This multifaceted pathogenesis underscores the critical need for mechanistic elucidation and translational development of precision management algorithms to mitigate this life-threatening complication of cancer immunotherapy.

- Citation: Zhang XM, Zhao FY, Gao LF, Xu T, Yang F, Qian NS. Immune therapy-related hyperprogressive disease: Molecular mechanisms, biomarkers, and clinical strategies. World J Clin Oncol 2025; 16(12): 110351

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v16/i12/110351.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v16.i12.110351

Programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1) inhibitors, as a significant breakthrough in the field of cancer immunotherapy[1], have been approved globally for the treatment of various malignancies, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and melanoma[2,3]. Drugs such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab have significantly extended patient survival[4]. However, the emergence of hyperprogressive disease (HPD), a unique pattern of tumor progression during immunotherapy, has severely impacted clinical outcomes[5]. HPD is characterized by a dramatic increase in tumor volume by 20-30 times during the initial phase of treatment, a doubling of the tumor growth rate (TGR) within two months, and the rapid appearance of new metastatic lesions, leading to a sharp reduction in median survival to 3.4 months[6-8]. Although the diagnostic criteria for HPD are not yet fully standardized and its incidence varies widely across different tumor types, its association with poor patient prognosis has been widely confirmed[9]. A deeper understanding of the immunological mechanisms of HPD is not only crucial for the development of predictive biomarkers but also provides a theoretical basis for exploring combined targeted therapy strategies, thereby advancing cancer immunotherapy towards precision and personalization.

The diagnostic criteria for HPD demonstrate considerable diversity, with several widely accepted core standards currently based on three main aspects: (1) TGR increasing by > 50% compared to pretreatment levels[10]; (2) Time to treatment failure (TTF) of less than 2 months; and (3) Disease progression meeting Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours criteria accompanied by rapid clinical deterioration. Compared to the conventional method of calculating TGR based on tumor volume, the criterion of ≥ 2-fold increase in the sum of maximum diameters of target lesions (TGK) co

The significant fluctuation in HPD incidence under different criteria is attributed to factors such as the mathematical difference between TGK and TGR (e.g., TGK = 2 corresponds to TGR = 8) and whether new lesions or clinical deterioration indicators are included. Currently, the definitions of HPD have certain limitations. The lack of a unified definition is a major bottleneck in HPD research, leading to heterogeneity in incidence rates, risk factors, and prognostic conclusions[15]. In the future, it is essential to establish a cross-cancer-type universal framework that integrates imaging, clinical, and molecular biomarkers to dynamically assess accelerated tumor progression. This will guide immunotherapy decision-making and mitigate the risk of overtreatment. Table 1 summarizes the incidence rates, key studies, and high-risk factors of HPD across different cancer types[10,13,14,16-22].

| Ref. | Cancer type | HPD incidence | Proposed risk factors |

| Ferrara et al[16], 2018 | NSCLC | 13.8%-26% | EGFR mutation, LDH > 250 U/L, liver metastasis, ≥ 2 metastatic sites |

| Lo Russo et al[14], 2020 | |||

| Economopoulou et al[17], 2021 | HNSCC | 15.4% | 11q13 chromosomal amplification (CCND1/FGF3), local recurrence |

| Kim et al[18], 2022 | GC | 9.2%-29.4% | EGFR/FGF4, MDM2 amplification, liver metastasis, high tumor burden, advanced age |

| Aoki et al[19], 2024 | |||

| Hwang et al[22], 2020 | Urothelial carcinoma | 6.4%-8% | Elevated baseline NLR, high LDH levels |

| Abbas et al[10], 2019 | |||

| Yamada et al[13], 2018 | Melanoma | 6%-42% | Advanced age, elevated baseline inflammatory markers (CRP/NLR) |

| Zhou et al[20], 2025 | |||

| Şen et al[21], 2024 | Bladder cancer | 12.9% | Elevated baseline NLR, advanced age |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 4.8% |

In-depth elucidation of the mechanisms underlying HPD not only explains why immunotherapy produces counterproductive effects in some patients but, more importantly, provides a theoretical basis for clinical prevention and treatment. It offers new insights for optimizing existing immunotherapy regimens, guiding clinicians in avoiding treatment risks, and enhancing the safety and efficacy of immunotherapy. The key molecular and cellular mechanisms of HPD are systematically summarized in Table 2.

| Regulatory factor | Core mechanism | Clinical significance | Potential intervention strategies |

| Treg cells | Abnormal activation post PD-1 blockade; inhibits APC function via CTLA-4/CD80/CD86; secretes IL-10/TGF-β to suppress effector T cells | Significant Treg infiltration in HPD patients, negatively correlated with treatment efficacy | Target CTLA-4 or deplete Tregs (e.g., anti-CCR4 antibodies) |

| M2-type TAM | Fc receptor-mediated pro-tumor phenotype conversion by anti-PD-1; recruited via CCR2/CCL2 and maintained by CSF-1R signaling | Forms synergistic network with Tregs/MDSCs to drive HPD | Combine CSF-1R inhibitors with PD-1 blockade (e.g., pexidartinib) |

| MDSC | Suppresses T cell function via IDO/VEGF/MMP9; promotes angiogenesis | High MDSC levels predict poor ICI response and HPD risk | Target CXCR2 or arginine metabolism (e.g., CB-1158) |

| T cell exhaustion | Compensatory upregulation of TIM-3/CTLA-4 post PD-1 blockade, leading to “secondary exhaustion” | Enriched in HPD patients with lost anti-tumor function | Multi-checkpoint targeting (e.g., anti-TIM-3 + anti-PD-1) |

| CAF | Upregulates PD-L1 via IL-6/STAT3; recruits Tregs via CXCL12; promotes M2-TAM differentiation | Promotes immunosuppressive microenvironment, positively correlated with HPD progression | Target TGF-β signaling (e.g., galunisertib) or CAF reprogramming |

| Inflammatory dysregulation | IL-10 inhibits CD28 signaling; IFN-γ induces PD-L1 upregulation; IL-6/TNF-α activate STAT3/NF-κB to promote proliferation | Cytokine profile predicts HPD risk | JAK inhibitors (e.g., ruxolitinib) or IL-6R blockade (tocilizumab) |

| Metabolic reprogramming | Tregs utilize lactate/OXPHOS for survival; CD36 mediates fatty acid metabolism adaptation | Metabolic competition exacerbates T cell dysfunction | Lactate dehydrogenase inhibitors or CD36 blockade |

| Genetic alterations | MDM2/MDM4 amplification (p53 degradation); EGFR activation (PD-L1 modification); DNMT3A mutations (epigenetic dysregulation) | 11-gene mutation signature significantly associated with HPD | MDM2 inhibitors (e.g., idasanutlin) or EGFR-TKI combination therapy |

Studies have shown that the PD-1 signaling pathway plays a significant role in regulating the activity of regulatory T (Treg) cells[23]. Researchers such as Kamada et al[24] discovered through human and mouse models that PD-1 blockade or deficiency not only enhances the anti-tumor activity of conventional T cells (Tconv) but also promotes the activation of Treg) cells. Specifically, PD-1 blockade strengthens the transmission of TCR and CD28 signaling pathways in Treg cells, promoting their proliferation and suppressing the function of effector T cells (including CD4 T cells and CD8 T cells) through various mechanisms[25]. Therefore, the ultimate effect of PD-1 blockade therapy actually depends on the dynamic balance between Treg activation and Tconv activation which is influenced by factors such as tumor type and characteristics of the immune microenvironment. Multiple clinical studies on HPD have observed a significant increase in Treg cell infiltration in the tumor tissues of patients experiencing HPD[26]. Particularly in studies on gastric cancer immunotherapy, it was found that proliferative (Ki67+) effector Treg cells (eTreg) were markedly increased in the tumor tissues of HPD patients, while the opposite trend was observed in patients without HPD[24]. Further analysis revealed that PD-1-positive eTreg cells in both the circulatory system and tumor tissues of these patients were in a highly activated state, with their cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) expression levels significantly higher than those of PD-1-negative eTreg cells. These findings collectively suggest that abnormal activation of Treg cells and the enhancement of their immunosuppressive function may be one of the key mechanisms leading to HPD following immunotherapy. In clinical treatment, special attention should be paid to the dynamic changes of Treg cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME) and their impact on treatment outcomes[26].

In the model of HPD following: PD-1 blockade therapy, antigen-presenting cell (APC) cells play a crucial role[27]. The increased Treg cells after PD-1 blockade therapy, particularly PD-1+ Treg cells with high CTLA-4 expression, can establish a robust immunosuppressive network by modulating the function of APCs. Specifically, Treg cells with high CTLA-4 expression bind to the co-stimulatory molecules CD80/CD86 on the surface of APCs, leading to the downregulation of these key co-stimulatory molecules[24]. This not only directly inhibits the activation of APCs but, more importantly, blocks the pathway through which CD8+ T cells receive co-stimulatory signals via the CD28 receptor, significantly impairing the anti-tumor function of CD8+ T cells[28,29]. Furthermore, within the tumor tissue, this interaction may result in increased accumulation of Treg cells on APCs. Combined with the downregulated CD80/CD86 co-stimulatory molecules, this limits the access and activation of Tconv cells by APCs[30].

Macrophages are a crucial immune cell population mediating the occurrence of HPD[31]. Analysis of pre-treatment tumor specimens from NSCLC patients revealed a characteristic infiltration pattern of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in the tumor lesions of HPD patients. These macrophages exhibit a unique immune phenotype [CD163, CD33, programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)][32], display an epithelial-like morphology (similar to alveolar macrophages), and tend to form dense clusters within the tumor foci. Animal experiments using immunodeficient mouse models also confirmed this finding. In HPD tumor tissues, there was a significant increase in leukocyte infiltration, primarily manifested as a marked rise in the number of intratumoral macrophages (F4/80+), while the infiltration levels of B lymphocytes (CD45R/B220+), granulocytes (Gr-1+), and natural killer (NK) cells (NKp46+) were comparable to those in the control group. Multiple studies support this observation: In lung adenocarcinoma models, reducing M2-type TAM recruitment through C-C chemokine receptor type 2/C-C chemokine ligand (CCL) 2 signaling blockade inhibited tumor growth[33]; in hepatocellular carcinoma research, macrophages were found to directly suppress T cell responses, and blocking the colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1)/CSF-1 receptor (CSF-1R) pathway induced tumor rejection; pancreatic cancer models demonstrated that combining PD-1/CTLA-4 antibodies with CSF-1R blockade enhanced therapeutic efficacy[34].

Furthermore, researchers have discovered that the Fc domain of anti-PD-1 antibodies plays a critical role in the functional reprogramming of macrophages, and the signaling it mediates is a significant factor contributing to HPD[32]. Experiments revealed that using full-length antibodies to block the PD-1 receptor expressed on TAMs themselves promoted the acquisition of a pro-tumor phenotype, whereas using anti-PD-1 F(ab’)2 fragments lacking the Fc segment completely eliminated this pro-tumor effect. Researchers proposed the hypothesis that the interaction between Fc receptors and the immune phenotype specific to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) might trigger the aggregation of M2 TAMs[32], reprogramming them into a more aggressive pro-tumor phenotype. These findings suggest that HPD may occur in patients with specific genetic and immune characteristics, and the underlying mechanisms still require further elucidation.

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), as a heterogeneous population of immunosuppressive cells, play a pivotal role in the immune regulation of the TME[35]. These cells not only directly participate in promoting tumor angiogenesis, metastasis, and other malignant processes but are also closely associated with clinical outcomes in patients. Multiple clinical studies have confirmed a significant correlation between MDSC levels and treatment efficacy: In prostate cancer, breast cancer, and colorectal cancer patients, lower MDSC infiltration often predicts better overall survival[36].

In the field of ICI therapy, the regulatory role of MDSCs is particularly prominent. A significant finding by Meyer et al[37] demonstrated that melanoma patients with lower MDSC frequencies exhibited better responses to ipilimumab treatment, suggesting that MDSC levels may serve as a predictive biomarker for ICI efficacy. This finding has been validated in numerous other studies[38,39], which showed that MDSCs negatively impact survival rates and are inversely correlated with the presence of functional antigen-specific T cells in advanced melanoma patients. This further underscores the critical role of MDSCs in immunotherapy responses. Notably, in mouse models of renal cell carcinoma and Lewis lung cancer, strategies combining MDSC blockade with ICI therapy demonstrated more significant survival benefits compared to ICI monotherapy[40].

T cell exhaustion is a critical mechanism of tumor immune evasion, characterized by the persistent overexpression of multiple inhibitory receptors, including PD-1, lymphocyte activation gene-3, T cell immunoreceptor with ig and ITIM domains, and mucin domain-containing molecule 3[41,42]. In patients with HPD, T cell exhaustion is particularly pronounced. Studies have found that due to continuous exposure to high concentrations of tumor neoantigens, these exhausted T cells cannot restore their function like normal memory T cells but instead fall into a deeper state of functional suppression, becoming more significantly enriched in tumor tissues[43,44]. Specifically, PD-1 blockade therapy leads to a significant expansion of PD-1/CTLA-4 double-positive Treg cells, which secrete inhibitory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-10 and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). These cytokines not only directly suppress effector T cell function but may also cause T cell dysfunction. Although PD-1 blockade initially activates some Tconv, under the persistent suppression of Treg cells, these T cells often exhibit rapid exhaustion after short-term activation, ultimately losing their anti-tumor capabilities entirely. Notably, abnormal activation of the PD-1/PD-L2 pathway also plays a role: PD-L2 (primarily expressed on endothelial cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells) inhibits T cell function through an atypical pathway (independent of CD80)[45]. This multi-layered T cell dysfunction forms a critical basis for the occurrence of HPD and explains why ICI therapy in some patients not only fails to restore T cell function but may further worsen the immune state[46].

Additionally, a noteworthy phenomenon during ICI therapy is the compensatory upregulation of immune checkpoints. In NSCLC patients and lung adenocarcinoma mouse models, tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells exhibit excessive T cell immunoreceptor with ig and ITIM domains expression during tumor progression. Meanwhile, ovarian cancer models show that PD-1 blockade significantly upregulates CTLA-4 and lymphocyte activation gene-3 expression on CD8+ T cells[47]. This compensatory upregulation leads to severe consequences: Further reduction in cytokine production, severe impairment of proliferation and migration functions, and the formation of a “secondary exhaustion” state. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing intervention strategies targeting HPD.

M2-type TAMs play a pivotal role in the development and progression of HPD[48]. Multiple studies have shown that PD-1 antibody treatment leads to the characteristic expansion of M2-type TAMs, which exhibit a unique CD163+CD33+PD-L1+ immunophenotype and cluster-distributed epithelial-like morphological features. Mechanistically, M2-type TAMs are extensively recruited to the TME through the C-C chemokine receptor type 2/CCL2 signaling pathway[49,50] and exert potent immunosuppressive functions via CSF-1/CSF-1R interactions. Notably, the Fc segment of anti-PD-1 antibodies binding to Fc receptors triggers abnormal aggregation and functional reprogramming of M2-type TAMs[32,51], endowing them with a more pro-tumorigenic phenotype. These reprogrammed M2-type TAMs not only directly suppress T cell function[52] but also form a synergistic network with immunosuppressive cells such as Tregs and MDSCs[53], collectively promoting tumor immune evasion and the development of HPD.

Of particular significance, preclinical studies have confirmed that the combined use of PD-1/CTLA-4 antibodies and CSF-1R inhibitors significantly enhances anti-tumor efficacy, providing a potential therapeutic strategy to overcome HPD. Furthermore, the development of novel treatments that specifically eliminate or reprogram M2-type TAMs, as well as the exploration of their interaction networks with other immune cells, will open new avenues for the prevention and treatment of HPD (Figure 1).

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), as a critical component of the TME, contribute to the development and progression of HPD through multiple mechanisms[54]. These activated stromal cells expressing α-smooth muscle actinnot only directly promote tumor growth and metastasis but also establish an immunosuppressive microenvironment through a complex immune regulatory network. Studies have shown that CAFs can recruit monocytes and promote their differentiation into M2-type TAMs[55], significantly enhancing immunosuppressive effects. In liver cancer, CAFs induce neutrophil activation and IL-6 release, triggering the IL-6-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)-PD-L1 signaling pathway, ultimately leading to T cell suppression. Additionally, CAFs promote Treg cell differentiation through the TGF-β signaling pathway[56,57] while inhibiting the activation of cytotoxic T cells and NK cells[58]. Notably, CAFs can directly upregulate PD-L1 expression on tumor cells[59] and induce PD-1 expression on immune cells. These mechanisms collectively explain the pivotal role of CAFs in promoting HPD during ICI therapy.

In patients experiencing HPD, the TME exhibits characteristic dysregulation of inflammatory factors, forming a unique immunosuppressive network. IL-10, as a key inhibitory factor, promotes HPD through a dual mechanism: On one hand, it inhibits CD28 tyrosine phosphorylation[60], blocking T cell co-stimulatory signals; on the other hand, it induces T cell unresponsiveness in an IL-2-deficient environment. This effect is particularly pronounced in microenvironments with increased Treg cells. Simultaneously, abnormal activation of the CCL17/CCL22-CCR4/CCR8 axis promotes Treg cell expansion and IL-10 secretion through the STAT3-FoxP3 pathway, creating a positive feedback loop. The interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) pathway exhibits a paradoxical role[61]: While it enhances antigen presentation and T cell recruitment, persistent stimulation leads to tumor cells upregulating PD-L1 expression via the Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription and phosphoinositide 3-kinase-protein kinase b pathways, ultimately resulting in treatment resistance[62]. Notably, in the HPD microenvironment, pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-6[63,64] and tumor necrosis factor-alpha[65] are elevated alongside anti-inflammatory factors like IL-10 and TGF-β. These factors activate the STAT3/nuclear factor-kappa B signaling pathway, promoting tumor proliferation and recruiting immunosuppressive cells such as TAMs and MDSCs. Additionally, proliferating PD-1+ Treg cells rapidly consume IL-2, depriving tumor-reactive effector T cells of this critical cytokine. These changes collectively construct an immune environment conducive to tumor hyperprogression. Understanding the characteristics of these inflammatory factors in the TME is crucial for future efforts to predict and treat HPD-related inflammation.

Research has found that the TME of HPD patients exhibits significant metabolic and immunosuppressive abnormalities. In a hypoxic, glucose-deprived, and acidic TME, tumor cells rapidly consume oxygen and glucose through aerobic glycolysis, producing large amounts of lactate and creating a harsh environment unfavorable for the survival of conventional immune cells. However, Tregs undergo FoxP3-mediated metabolic reprogramming, inhibiting glycolysis and enhancing oxidative phosphorylation[66], enabling them to utilize lactate as an energy source to sustain their survival and immunosuppressive functions[67]. Additionally, Tregs upregulate the fatty acid transporter CD36, adapting to the hostile microenvironment by utilizing fatty acids released by tumor and stromal cells, and the efficacy of ICIs is further diminished in Treg-dominated tumors. This abnormal metabolic adaptation is closely linked to the synergistic effects of various immunosuppressive cells. Furthermore, CAFs recruit Tregs by secreting C-X-C chemokine ligand 12, IL-6, and release TGF-β to promote the differentiation of M2-type TAMs[68]. M2 TAMs further secrete CCL22 and IL-6, forming a positive feedback loop that enhances immunosuppression. Meanwhile, MDSCs inhibit the function of effector T cells by producing molecules such as IDO, VEGF, and MMP9[69], promoting tumor metastasis. These abnormal interactions among cells collectively construct the unique immunosuppressive network characteristic of HPD. The above studies indicate that the occurrence of HPD is closely related to the metabolic adaptation and abnormal interactions of immune cells in the TME. Suppressive cells like Tregs survive and function in the harsh environment through unique metabolic reprogramming, while the synergistic effects of CAFs, M2 TAMs, and MDSCs further strengthen the immunosuppressive microenvironment[54]. These findings provide a theoretical basis for developing combination therapeutic strategies targeting TME metabolism and cellular interactions, which may help prevent or reverse the occurrence of HPD. Future research should focus on how to disrupt this abnormal metabolic-immune network and restore anti-tumor immune responses.

Specific genomic alterations have been confirmed to be closely associated with the occurrence of HPD. Multiple studies have found that mutations or amplifications of certain key genes significantly increase the risk of HPD. The amplification of the mouse double minute 2 homolog (MDM2)/MDM4 gene family and mutations in the DNMT3A gene have been identified by several research teams as important molecular markers of HPD[8,70]. Mechanistic studies reveal that the MDM2 protein can directly bind to the p53 protein, promoting its degradation and thereby weakening p53’s tumor-suppressive function[71]. Additionally, the JAK-signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling pathway activated by ICIs upregulates the expression of interferon regulatory factor IRF-8, which in turn positively feedbacks to activate MDM2 transcription. MDM2 also participates in tumor angiogenesis and metastasis by regulating VEGF expression. The activation of another key gene, EGFR, not only promotes the expression of immune checkpoints such as CTLA-4, PD-1, and PD-L1, but its signaling pathway can also induce post-translational modifications of the PD-L1 protein[72,73]. Furthermore, Xiong et al[74] identified through whole-exome sequencing analysis that deleterious mutations in 11 genes, including TRPC4, POTEE, and FBN2, are significantly associated with HPD.

These changes collectively form the molecular basis of tumor immune evasion. These findings provide crucial insights into understanding the genetic mechanisms of HPD and also point the way for developing targeted predictive and intervention strategies.

Currently, the prediction research of HPD still faces significant challenges. Conventional imaging assessments exhibit notable delays, while existing molecular biomarkers such as PD-L1 demonstrate substantial limitations in predictive efficacy: Clinical data reveal insufficient accuracy (with only 40%-45% response rates in high-expression patients), compounded by multiple constraints including tumor spatial and temporal heterogeneity (30%-40% discrepancies between primary and metastatic lesions), standardization issues in detection (60%-70% concordance rates across different platforms), and complex microenvironmental regulation (e.g., the bypass effects of immunosuppressive cells like Tregs and MDSCs)[75,76]. These factors collectively hinder the ability to meet clinical demands for precise early warning. With advancements in genomics and liquid biopsy technologies, researchers are actively working to establish more sensitive and specific molecular prediction systems.

Liquid biopsy, as an emerging non-invasive detection technology, has demonstrated significant value in monitoring the efficacy of tumor immunotherapy and providing early warning of HPD. This technology comprehensively evaluates blood-based tumor mutation burden (bTMB) and tumor genomic instability characteristics by detecting circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and cell-free DNA in peripheral blood. Multiple clinical studies have confirmed that bTMB levels are significantly positively correlated with immunotherapy response[77,78], offering a new molecular marker for pre-treatment efficacy prediction. Notably, the dynamic changes in ctDNA exhibit higher sensitivity compared to traditional imaging examinations. For example, a study involving 125 melanoma patients showed that ctDNA levels in patients with pseudoprogression decreased significantly by 10-fold during treatment, while those in true progression patients continued to rise[79]. The Weiss team further discovered that cell-free DNA chromosomal instability scores could predict the occurrence of HPD 6-9 weeks before conventional imaging detection[80], a breakthrough finding that provides a valuable time window for clinical intervention.

In addition to liquid biopsy, routine inflammatory indicators and metabolic markers in peripheral blood also show promising predictive potential. In the analysis of immune cell subsets, the dynamic changes in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) are closely related to disease progression. Kiriu et al[81] found that patients with an NLR increase of more than 30% had significantly shorter TTF. However, it should be noted that research teams such as Ferrara et al[16] did not observe significant correlations between NLR, LDH, and HPD[67], a discrepancy that may stem from differences in study populations, detection methods, and evaluation criteria. Based on the current evidence, establishing a multi-parameter joint prediction model that integrates genomic features (ctDNA/bTMB), immune-inflammatory indicators (NLR), and metabolic markers (LDH) may be an important direction for improving the accuracy of HPD prediction. With advancements in detection technology and the development of large-scale studies in the future, the clinical application value of these biomarkers will be more clearly defined.

Based on the immunometabolic mechanisms of HPD, a variety of targeted therapeutic strategies have emerged in recent years. Firstly, targeting immunosuppressive cells is a crucial direction: Anti-CCR4/CCR8 antibodies can block Treg recruitment; CSF-1R inhibitors (such as pexidartinib) or CD47-targeting drugs can eliminate M2-type macrophages[82]; indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenaseinhibitors (such as epacadostat) or arginase inhibitors can reverse the immunosuppressive functions of MDSCs[83]. Secondly, drugs that intervene in metabolic abnormalities can disrupt the adaptive survival of Tregs. Additionally, combination immunomodulatory therapies may restore effector T cell function. Preclinical studies have shown that the combination of PD-1 inhibitors with the aforementioned targeted drugs can significantly delay HPD progression. Currently, multiple clinical trials are underway. In the future, it will be necessary to further optimize treatment timing and combination strategies, and to screen beneficiary populations through biomarkers to achieve precise intervention in HPD.

Combination therapy strategies represent a critical direction for enhancing the efficacy of ICIs and reducing the risk of HPD. In hepatocellular carcinoma treatment, the combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab has demonstrated significant advantages, with a lower incidence of HPD compared to sorafenib monotherapy, and the risk of poor prognosis being independent of the treatment approach. Studies indicate that tumor plasticity is a key mechanism of ICI-mediated HPD, where IFN-γ and PD-L1 promote malignant transformation of tumor cells by regulating CD44 expression and the MAPK/STAT3 signaling pathway. This provides new insights for predicting HPD (e.g., monitoring plasticity markers such as CD44) and treating it (targeting the IFN-γ/PD-L1 pathway). Furthermore, immune combination therapy models show potential: The combination of NK cells with ICIs may serve as an alternative option for HPD patients[84]; data from the CheckMate 227 trial confirmed that nivolumab combined with chemotherapy significantly reduces the risk of disease progression compared to its combination with ipilimumab[85]. These findings offer important evidence for optimizing combination therapy regimens to avoid HPD.

HPD, as a significant challenge in PD-1 inhibitor immunotherapy, involves multiple mechanisms, including abnormal activation of Treg cells, recruitment of M2-type macrophages and MDSCs, T cell exhaustion, and dysregulation of the inflammatory cytokine network within the TME. Clinically, HPD is characterized by accelerated tumor growth during the early stages of treatment, explosive emergence of new metastatic lesions, and extremely poor prognosis, with significant variations in incidence and risk factors across different cancer types. Currently, diagnostic criteria remain inconsistent, and future research should focus on establishing a universal diagnostic framework across cancer types to enable early warning and personalized intervention for HPD.

| 1. | Gao M, Shi J, Xiao X, Yao Y, Chen X, Wang B, Zhang J. PD-1 regulation in immune homeostasis and immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2024;588:216726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Liu Z, Yang Z, Wu J, Zhang W, Sun Y, Zhang C, Bai G, Yang L, Fan H, Chen Y, Zhang L, Jiang B, Liu X, Ma X, Tang W, Liu C, Qu Y, Yan L, Zhao D, Wu Y, He S, Xu L, Peng L, Chen X, Zhou B, Zhao L, Zhao Z, Tan F, Zhang W, Yi D, Li X, Gao Q, Zhang G, Wang Y, Yang M, Fu H, Guo Y, Hu X, Cai Q, Qi L, Bo Y, Peng H, Tian Z, She Y, Zou C, Zhu L, Cheng S, Zhang Y, Zhong W, Chen C, Gao S, Zhang Z. A single-cell atlas reveals immune heterogeneity in anti-PD-1-treated non-small cell lung cancer. Cell. 2025;188:3081-3096.e19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 51.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chen G, Huang AC, Zhang W, Zhang G, Wu M, Xu W, Yu Z, Yang J, Wang B, Sun H, Xia H, Man Q, Zhong W, Antelo LF, Wu B, Xiong X, Liu X, Guan L, Li T, Liu S, Yang R, Lu Y, Dong L, McGettigan S, Somasundaram R, Radhakrishnan R, Mills G, Lu Y, Kim J, Chen YH, Dong H, Zhao Y, Karakousis GC, Mitchell TC, Schuchter LM, Herlyn M, Wherry EJ, Xu X, Guo W. Exosomal PD-L1 contributes to immunosuppression and is associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature. 2018;560:382-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1806] [Cited by in RCA: 2202] [Article Influence: 275.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Stark MC, Joubert AM, Visagie MH. Molecular Farming of Pembrolizumab and Nivolumab. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:10045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kanjanapan Y, Guduguntla G, Varikara AK, Szajer J, Yip D, Cockburn J, Fadia M. Hyperprogressive Disease (HPD) in Solid Tumours Receiving Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in a Real-World Setting. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2023;22:15330338231209129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhang H, Fang X, Li D, Yang M, Yu L, Ding Y, Shen H, Yuan Y. Hyperprogressive disease in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Curr Probl Cancer. 2021;45:100688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Champiat S, Dercle L, Ammari S, Massard C, Hollebecque A, Postel-Vinay S, Chaput N, Eggermont A, Marabelle A, Soria JC, Ferté C. Hyperprogressive Disease Is a New Pattern of Progression in Cancer Patients Treated by Anti-PD-1/PD-L1. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:1920-1928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 703] [Cited by in RCA: 921] [Article Influence: 92.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kato S, Goodman A, Walavalkar V, Barkauskas DA, Sharabi A, Kurzrock R. Hyperprogressors after Immunotherapy: Analysis of Genomic Alterations Associated with Accelerated Growth Rate. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:4242-4250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 538] [Cited by in RCA: 711] [Article Influence: 79.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Thommen DS, Koelzer VH, Herzig P, Roller A, Trefny M, Dimeloe S, Kiialainen A, Hanhart J, Schill C, Hess C, Savic Prince S, Wiese M, Lardinois D, Ho PC, Klein C, Karanikas V, Mertz KD, Schumacher TN, Zippelius A. A transcriptionally and functionally distinct PD-1(+) CD8(+) T cell pool with predictive potential in non-small-cell lung cancer treated with PD-1 blockade. Nat Med. 2018;24:994-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 498] [Cited by in RCA: 906] [Article Influence: 113.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Abbas W, Rao RR, Popli S. Hyperprogression after immunotherapy. South Asian J Cancer. 2019;8:244-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Karabajakian A, Garrivier T, Crozes C, Gadot N, Blay JY, Bérard F, Céruse P, Zrounba P, Saintigny P, Mastier C, Fayette J. Hyperprogression and impact of tumor growth kinetics after PD1/PDL1 inhibition in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2020;11:1618-1628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rocha P, Ramal D, Ripoll E, Moliner L, Corbera A, Hardy-Werbin M, Orrillo M, Taus Á, Zuccarino F, Gibert J, Perera-Bel J, Casadevall D, Arriola E. Comparison of Different Methods for Defining Hyperprogressive Disease in NSCLC. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2021;2:100115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yamada S, Itai S, Kaneko MK, Kato Y. Detection of high PD-L1 expression in oral cancers by a novel monoclonal antibody L(1)Mab-4. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2018;13:123-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lo Russo G, Facchinetti F, Tiseo M, Garassino MC, Ferrara R. Hyperprogressive Disease upon Immune Checkpoint Blockade: Focus on Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2020;22:41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu J, Wu Q, Wu S, Xie X. Investigation on potential biomarkers of hyperprogressive disease (HPD) triggered by immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Clin Transl Oncol. 2021;23:1782-1793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ferrara R, Mezquita L, Texier M, Lahmar J, Audigier-Valette C, Tessonnier L, Mazieres J, Zalcman G, Brosseau S, Le Moulec S, Leroy L, Duchemann B, Lefebvre C, Veillon R, Westeel V, Koscielny S, Champiat S, Ferté C, Planchard D, Remon J, Boucher ME, Gazzah A, Adam J, Bria E, Tortora G, Soria JC, Besse B, Caramella C. Hyperprogressive Disease in Patients With Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated With PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors or With Single-Agent Chemotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1543-1552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 576] [Article Influence: 82.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Economopoulou P, Anastasiou M, Papaxoinis G, Spathas N, Spathis A, Oikonomopoulos N, Kotsantis I, Tsavaris O, Gkotzamanidou M, Gavrielatou N, Vagia E, Kyrodimos E, Gagari E, Giotakis E, Delides A, Psyrri A. Patterns of Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Association with Genomic and Clinical Features in Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC). Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kim CG, Hong M, Jeung HC, Lee G, Chung HC, Rha SY, Kim HS, Lee CK, Lee JH, Han Y, Kim JH, Lee SY, Kim H, Shin SJ, Baek SE, Jung M. Hyperprogressive disease during PD-1 blockade in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2022;172:387-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Aoki T, Kudo M, Ueshima K, Morita M, Chishina H, Takita M, Hagiwara S, Ida H, Minami Y, Tsurusaki M, Nishida N. Incidence of Hyper Progressive Disease in Combination Immunotherapy and Anti-Programmed Cell Death Protein 1/Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Monotherapy for Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2024;13:56-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhou L, Cao M, Zhu H, Chi Z, Cui C, Sheng X, Mao L, Lian B, Tang B, Yan X, Bai X, Wang X, Li S, Guo J, Sun YS, Si L. Predominance of hyperprogression in mucosal melanoma during anti-PD-1 monotherapy treatment. Oncologist. 2025;30:oyae211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Şen GA, Öztaş NŞ, Değerli E, Guliyev M, Can G, Turna H, Özgüroğlu M. Hyperprogressive disease in patients with advanced cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Clin Transl Oncol. 2024;26:3264-3271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hwang I, Park I, Yoon SK, Lee JL. Hyperprogressive Disease in Patients With Urothelial Carcinoma or Renal Cell Carcinoma Treated With PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2020;18:e122-e133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Asano T, Meguri Y, Yoshioka T, Kishi Y, Iwamoto M, Nakamura M, Sando Y, Yagita H, Koreth J, Kim HT, Alyea EP, Armand P, Cutler CS, Ho VT, Antin JH, Soiffer RJ, Maeda Y, Tanimoto M, Ritz J, Matsuoka KI. PD-1 modulates regulatory T-cell homeostasis during low-dose interleukin-2 therapy. Blood. 2017;129:2186-2197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kamada T, Togashi Y, Tay C, Ha D, Sasaki A, Nakamura Y, Sato E, Fukuoka S, Tada Y, Tanaka A, Morikawa H, Kawazoe A, Kinoshita T, Shitara K, Sakaguchi S, Nishikawa H. PD-1(+) regulatory T cells amplified by PD-1 blockade promote hyperprogression of cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:9999-10008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 401] [Cited by in RCA: 808] [Article Influence: 115.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kumagai S, Togashi Y, Kamada T, Sugiyama E, Nishinakamura H, Takeuchi Y, Vitaly K, Itahashi K, Maeda Y, Matsui S, Shibahara T, Yamashita Y, Irie T, Tsuge A, Fukuoka S, Kawazoe A, Udagawa H, Kirita K, Aokage K, Ishii G, Kuwata T, Nakama K, Kawazu M, Ueno T, Yamazaki N, Goto K, Tsuboi M, Mano H, Doi T, Shitara K, Nishikawa H. The PD-1 expression balance between effector and regulatory T cells predicts the clinical efficacy of PD-1 blockade therapies. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:1346-1358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 597] [Article Influence: 99.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wakiyama H, Kato T, Furusawa A, Okada R, Inagaki F, Furumoto H, Fukushima H, Okuyama S, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Treg-Dominant Tumor Microenvironment Is Responsible for Hyperprogressive Disease after PD-1 Blockade Therapy. Cancer Immunol Res. 2022;10:1386-1397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Schetters STT, Rodriguez E, Kruijssen LJW, Crommentuijn MHW, Boon L, Van den Bossche J, Den Haan JMM, Van Kooyk Y. Monocyte-derived APCs are central to the response of PD1 checkpoint blockade and provide a therapeutic target for combination therapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8:e000588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hassannia H, Ghasemi Chaleshtari M, Atyabi F, Nosouhian M, Masjedi A, Hojjat-Farsangi M, Namdar A, Azizi G, Mohammadi H, Ghalamfarsa G, Sabz G, Hasanzadeh S, Yousefi M, Jadidi-Niaragh F. Blockage of immune checkpoint molecules increases T-cell priming potential of dendritic cell vaccine. Immunology. 2020;159:75-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Harryvan TJ, Verdegaal EME, Hardwick JCH, Hawinkels LJAC, van der Burg SH. Targeting of the Cancer-Associated Fibroblast-T-Cell Axis in Solid Malignancies. J Clin Med. 2019;8:1989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tekguc M, Wing JB, Osaki M, Long J, Sakaguchi S. Treg-expressed CTLA-4 depletes CD80/CD86 by trogocytosis, releasing free PD-L1 on antigen-presenting cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:e2023739118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 328] [Article Influence: 65.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Indino S, Borzi C, Moscheni C, Sartori P, De Cecco L, Bernardo G, Le Noci V, Arnaboldi F, Triulzi T, Sozzi G, Tagliabue E, Sfondrini L, Gagliano N, Moro M, Sommariva M. The Educational Program of Macrophages toward a Hyperprogressive Disease-Related Phenotype Is Orchestrated by Tumor-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:15802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lo Russo G, Moro M, Sommariva M, Cancila V, Boeri M, Centonze G, Ferro S, Ganzinelli M, Gasparini P, Huber V, Milione M, Porcu L, Proto C, Pruneri G, Signorelli D, Sangaletti S, Sfondrini L, Storti C, Tassi E, Bardelli A, Marsoni S, Torri V, Tripodo C, Colombo MP, Anichini A, Rivoltini L, Balsari A, Sozzi G, Garassino MC. Antibody-Fc/FcR Interaction on Macrophages as a Mechanism for Hyperprogressive Disease in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Subsequent to PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:989-999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 40.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Fei L, Ren X, Yu H, Zhan Y. Targeting the CCL2/CCR2 Axis in Cancer Immunotherapy: One Stone, Three Birds? Front Immunol. 2021;12:771210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 30.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ao JY, Zhu XD, Chai ZT, Cai H, Zhang YY, Zhang KZ, Kong LQ, Zhang N, Ye BG, Ma DN, Sun HC. Colony-Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor Blockade Inhibits Tumor Growth by Altering the Polarization of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16:1544-1554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Blidner AG, Bach CA, García PA, Merlo JP, Cagnoni AJ, Bannoud N, Manselle Cocco MN, Pérez Sáez JM, Pinto NA, Torres NI, Sarrias L, Dalotto-Moreno T, Gatto SG, Morales RM, Giribaldi ML, Stupirski JC, Cerliani JP, Bellis SL, Salatino M, Troncoso MF, Mariño KV, Abba MC, Croci DO, Rabinovich GA. Glycosylation-driven programs coordinate immunoregulatory and pro-angiogenic functions of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Immunity. 2025;58:1553-1571.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Zhou QZ, Liu CD, Yang JK, Zhou JH, Bian J. [Changed percentage of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the peripheral blood of prostate cancer patients and its clinical implication]. Zhonghua Nankexue Zazhi. 2016;22:963-967. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 37. | Meyer C, Cagnon L, Costa-Nunes CM, Baumgaertner P, Montandon N, Leyvraz L, Michielin O, Romano E, Speiser DE. Frequencies of circulating MDSC correlate with clinical outcome of melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63:247-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 435] [Cited by in RCA: 468] [Article Influence: 39.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Sade-Feldman M, Kanterman J, Klieger Y, Ish-Shalom E, Olga M, Saragovi A, Shtainberg H, Lotem M, Baniyash M. Clinical Significance of Circulating CD33+CD11b+HLA-DR- Myeloid Cells in Patients with Stage IV Melanoma Treated with Ipilimumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:5661-5672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Martens A, Wistuba-Hamprecht K, Geukes Foppen M, Yuan J, Postow MA, Wong P, Romano E, Khammari A, Dreno B, Capone M, Ascierto PA, Di Giacomo AM, Maio M, Schilling B, Sucker A, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, Eigentler TK, Martus P, Wolchok JD, Blank C, Pawelec G, Garbe C, Weide B. Baseline Peripheral Blood Biomarkers Associated with Clinical Outcome of Advanced Melanoma Patients Treated with Ipilimumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:2908-2918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 379] [Cited by in RCA: 449] [Article Influence: 44.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Orillion A, Hashimoto A, Damayanti N, Shen L, Adelaiye-Ogala R, Arisa S, Chintala S, Ordentlich P, Kao C, Elzey B, Gabrilovich D, Pili R. Entinostat Neutralizes Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells and Enhances the Antitumor Effect of PD-1 Inhibition in Murine Models of Lung and Renal Cell Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:5187-5201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 35.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Gebhardt T, Park SL, Parish IA. Stem-like exhausted and memory CD8(+) T cells in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2023;23:780-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 45.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Sun L, Su Y, Jiao A, Wang X, Zhang B. T cells in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 623] [Article Influence: 207.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Wang J, Hong J, Yang F, Liu F, Wang X, Shen Z, Wu D. A deficient MIF-CD74 signaling pathway may play an important role in immunotherapy-induced hyper-progressive disease. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2023;39:1169-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Lee EJ, Choi JG, Han JH, Kim YW, Lim J, Chung HS. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Reveals Immuno-Oncology Characteristics of Tumor-Infiltrating T Lymphocytes in Photodynamic Therapy-Treated Colorectal Cancer Mouse Model. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:13913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Takehara T, Wakamatsu E, Machiyama H, Nishi W, Emoto K, Azuma M, Soejima K, Fukunaga K, Yokosuka T. PD-L2 suppresses T cell signaling via coinhibitory microcluster formation and SHP2 phosphatase recruitment. Commun Biol. 2021;4:581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Zheng J, Zhou X, Fu Y, Chen Q. Advances in the Study of Hyperprogression of Different Tumors Treated with PD-1/PD-L1 Antibody and the Mechanisms of Its Occurrence. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:1314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Huang RY, Francois A, McGray AR, Miliotto A, Odunsi K. Compensatory upregulation of PD-1, LAG-3, and CTLA-4 limits the efficacy of single-agent checkpoint blockade in metastatic ovarian cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1249561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 29.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kim CG, Kim C, Yoon SE, Kim KH, Choi SJ, Kang B, Kim HR, Park SH, Shin EC, Kim YY, Kim DJ, Chung HC, Chon HJ, Choi HJ, Lim HY. Hyperprogressive disease during PD-1 blockade in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2021;74:350-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 29.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Chang AL, Miska J, Wainwright DA, Dey M, Rivetta CV, Yu D, Kanojia D, Pituch KC, Qiao J, Pytel P, Han Y, Wu M, Zhang L, Horbinski CM, Ahmed AU, Lesniak MS. CCL2 Produced by the Glioma Microenvironment Is Essential for the Recruitment of Regulatory T Cells and Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Cancer Res. 2016;76:5671-5682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 508] [Article Influence: 50.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Hartwig T, Montinaro A, von Karstedt S, Sevko A, Surinova S, Chakravarthy A, Taraborrelli L, Draber P, Lafont E, Arce Vargas F, El-Bahrawy MA, Quezada SA, Walczak H. The TRAIL-Induced Cancer Secretome Promotes a Tumor-Supportive Immune Microenvironment via CCR2. Mol Cell. 2017;65:730-742.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Kim KS, Habashy K, Gould A, Zhao J, Najem H, Amidei C, Saganty R, Arrieta VA, Dmello C, Chen L, Zhang DY, Castro B, Billingham L, Levey D, Huber O, Marques M, Savitsky DA, Morin BM, Muzzio M, Canney M, Horbinski C, Zhang P, Miska J, Padney S, Zhang B, Rabadan R, Phillips JJ, Butowski N, Heimberger AB, Hu J, Stupp R, Chand D, Lee-Chang C, Sonabend AM. Fc-enhanced anti-CTLA-4, anti-PD-1, doxorubicin, and ultrasound-mediated blood-brain barrier opening: A novel combinatorial immunotherapy regimen for gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2024;26:2044-2060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Orecchioni M, Ghosheh Y, Pramod AB, Ley K. Macrophage Polarization: Different Gene Signatures in M1(LPS+) vs. Classically and M2(LPS-) vs. Alternatively Activated Macrophages. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 765] [Cited by in RCA: 1529] [Article Influence: 218.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Li Y, Yang B, Miao H, Liu L, Wang Z, Jiang C, Yang Y, Qiu S, Li X, Geng Y, Zhang Y, Liu Y. Nicotinamide N -methyltransferase promotes M2 macrophage polarization by IL6 and MDSC conversion by GM-CSF in gallbladder carcinoma. Hepatology. 2023;78:1352-1367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Koppensteiner L, Mathieson L, O'Connor RA, Akram AR. Cancer Associated Fibroblasts - An Impediment to Effective Anti-Cancer T Cell Immunity. Front Immunol. 2022;13:887380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Jain S, Rick JW, Joshi RS, Beniwal A, Spatz J, Gill S, Chang AC, Choudhary N, Nguyen AT, Sudhir S, Chalif EJ, Chen JS, Chandra A, Haddad AF, Wadhwa H, Shah SS, Choi S, Hayes JL, Wang L, Yagnik G, Costello JF, Diaz A, Heiland DH, Aghi MK. Single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics reveal cancer-associated fibroblasts in glioblastoma with protumoral effects. J Clin Invest. 2023;133:e147087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 47.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Lin SC, Liao YC, Chen PM, Yang YY, Wang YH, Tung SL, Chuang CM, Sung YW, Jang TH, Chuang SE, Wang LH. Periostin promotes ovarian cancer metastasis by enhancing M2 macrophages and cancer-associated fibroblasts via integrin-mediated NF-κB and TGF-β2 signaling. J Biomed Sci. 2022;29:109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Wu F, Yang J, Liu J, Wang Y, Mu J, Zeng Q, Deng S, Zhou H. Signaling pathways in cancer-associated fibroblasts and targeted therapy for cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 540] [Article Influence: 108.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Li T, Yi S, Liu W, Jia C, Wang G, Hua X, Tai Y, Zhang Q, Chen G. Colorectal carcinoma-derived fibroblasts modulate natural killer cell phenotype and antitumor cytotoxicity. Med Oncol. 2013;30:663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Pei L, Liu Y, Liu L, Gao S, Gao X, Feng Y, Sun Z, Zhang Y, Wang C. Roles of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in anti- PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy for solid cancers. Mol Cancer. 2023;22:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Kaviani E, Hosseini A, Mahmoudi Maymand E, Ramzi M, Ghaderi A, Ramezani A. Triggering of lymphocytes by CD28, 4-1BB, and PD-1 checkpoints to enhance the immune response capacities. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0275777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Angelicola S, Giunchi F, Ruzzi F, Frascino M, Pitzalis M, Scalambra L, Semprini MS, Pittino OM, Cappello C, Siracusa I, Chillico IC, Di Noia M, Turato C, De Siervi S, Lescai F, Ciavattini T, Lopatriello G, Bertoli L, De Jonge H, Iamele L, Altimari A, Gruppioni E, Ardizzoni A, Rossato M, Gelsomino F, Lollini PL, Palladini A. PD-L1 and IFN-γ modulate Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) cell plasticity associated to immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)-mediated hyperprogressive disease (HPD). J Transl Med. 2025;23:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Li G, Choi JE, Kryczek I, Sun Y, Liao P, Li S, Wei S, Grove S, Vatan L, Nelson R, Schaefer G, Allen SG, Sankar K, Fecher LA, Mendiratta-Lala M, Frankel TL, Qin A, Waninger JJ, Tezel A, Alva A, Lao CD, Ramnath N, Cieslik M, Harms PW, Green MD, Chinnaiyan AM, Zou W. Intersection of immune and oncometabolic pathways drives cancer hyperprogression during immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:304-322.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 38.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Liu C, Yang L, Xu H, Zheng S, Wang Z, Wang S, Yang Y, Zhang S, Feng X, Sun N, Wang Y, He J. Systematic analysis of IL-6 as a predictive biomarker and desensitizer of immunotherapy responses in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Med. 2022;20:187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Silva EM, Mariano VS, Pastrez PRA, Pinto MC, Castro AG, Syrjanen KJ, Longatto-Filho A. High systemic IL-6 is associated with worse prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Montfort A, Colacios C, Levade T, Andrieu-Abadie N, Meyer N, Ségui B. Corrigendum: The TNF Paradox in Cancer Progression and Immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Watson MJ, Vignali PDA, Mullett SJ, Overacre-Delgoffe AE, Peralta RM, Grebinoski S, Menk AV, Rittenhouse NL, DePeaux K, Whetstone RD, Vignali DAA, Hand TW, Poholek AC, Morrison BM, Rothstein JD, Wendell SG, Delgoffe GM. Metabolic support of tumour-infiltrating regulatory T cells by lactic acid. Nature. 2021;591:645-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 605] [Cited by in RCA: 906] [Article Influence: 181.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Kempkes RWM, Joosten I, Koenen HJPM, He X. Metabolic Pathways Involved in Regulatory T Cell Functionality. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Peng D, Fu M, Wang M, Wei Y, Wei X. Targeting TGF-β signal transduction for fibrosis and cancer therapy. Mol Cancer. 2022;21:104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 777] [Article Influence: 194.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Oh MH, Sun IH, Zhao L, Leone RD, Sun IM, Xu W, Collins SL, Tam AJ, Blosser RL, Patel CH, Englert JM, Arwood ML, Wen J, Chan-Li Y, Tenora L, Majer P, Rais R, Slusher BS, Horton MR, Powell JD. Targeting glutamine metabolism enhances tumor-specific immunity by modulating suppressive myeloid cells. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:3865-3884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 346] [Article Influence: 57.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Adashek JJ, Subbiah IM, Matos I, Garralda E, Menta AK, Ganeshan DM, Subbiah V. Hyperprogression and Immunotherapy: Fact, Fiction, or Alternative Fact? Trends Cancer. 2020;6:181-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Valentini S, Mele G, Attili M, Assenza MR, Saccoccia F, Sardina F, Rinaldo C, Massari R, Tirelli N, Pontecorvi A, Moretti F. Targeting the MDM2-MDM4 interaction interface reveals an otherwise therapeutically active wild-type p53 in colorectal cancer. Mol Oncol. 2025;19:2412-2430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Okuyama K, Naruse T, Yanamoto S. Tumor microenvironmental modification by the current target therapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2023;42:114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Shu X, Xu R, Xiong P, Liu J, Zhou Z, Shen T, Zhang X. Exploring the Effects and Potential Mechanisms of Hesperidin for the Treatment of CPT-11-Induced Diarrhea: Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and Experimental Validation. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:9309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Xiong D, Wang Y, Singavi AK, Mackinnon AC, George B, You M. Immunogenomic Landscape Contributes to Hyperprogressive Disease after Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy for Cancer. iScience. 2018;9:258-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Champiat S, Ferrara R, Massard C, Besse B, Marabelle A, Soria JC, Ferté C. Hyperprogressive disease: recognizing a novel pattern to improve patient management. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:748-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Tang Q, Chen Y, Li X, Long S, Shi Y, Yu Y, Wu W, Han L, Wang S. The role of PD-1/PD-L1 and application of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in human cancers. Front Immunol. 2022;13:964442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 387] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Wang Z, Duan J, Cai S, Han M, Dong H, Zhao J, Zhu B, Wang S, Zhuo M, Sun J, Wang Q, Bai H, Han J, Tian Y, Lu J, Xu T, Zhao X, Wang G, Cao X, Li F, Wang D, Chen Y, Bai Y, Zhao J, Zhao Z, Zhang Y, Xiong L, He J, Gao S, Wang J. Assessment of Blood Tumor Mutational Burden as a Potential Biomarker for Immunotherapy in Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer With Use of a Next-Generation Sequencing Cancer Gene Panel. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:696-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 377] [Article Influence: 53.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Lee JH, Long GV, Menzies AM, Lo S, Guminski A, Whitbourne K, Peranec M, Scolyer R, Kefford RF, Rizos H, Carlino MS. Association Between Circulating Tumor DNA and Pseudoprogression in Patients With Metastatic Melanoma Treated With Anti-Programmed Cell Death 1 Antibodies. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:717-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Weiss GJ, Beck J, Braun DP, Bornemann-Kolatzki K, Barilla H, Cubello R, Quan W Jr, Sangal A, Khemka V, Waypa J, Mitchell WM, Urnovitz H, Schütz E. Tumor Cell-Free DNA Copy Number Instability Predicts Therapeutic Response to Immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:5074-5081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Ji Z, Cui Y, Peng Z, Gong J, Zhu HT, Zhang X, Li J, Lu M, Lu Z, Shen L, Sun YS. Use of Radiomics to Predict Response to Immunotherapy of Malignant Tumors of the Digestive System. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e924671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Kiriu T, Yamamoto M, Nagano T, Hazama D, Sekiya R, Katsurada M, Tamura D, Tachihara M, Kobayashi K, Nishimura Y. The time-series behavior of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is useful as a predictive marker in non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0193018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Weaver JD, Stack EC, Buggé JA, Hu C, McGrath L, Mueller A, Wong M, Klebanov B, Rahman T, Kaufman R, Fregeau C, Spaulding V, Priess M, Legendre K, Jaffe S, Upadhyay D, Singh A, Xu CA, Krukenberg K, Zhang Y, Ezzyat Y, Saddier Axe D, Kuhne MR, Meehl MA, Shaffer DR, Weist BM, Wiederschain D, Depis F, Gostissa M. Differential expression of CCR8 in tumors versus normal tissue allows specific depletion of tumor-infiltrating T regulatory cells by GS-1811, a novel Fc-optimized anti-CCR8 antibody. Oncoimmunology. 2022;11:2141007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Fleming V, Hu X, Weber R, Nagibin V, Groth C, Altevogt P, Utikal J, Umansky V. Targeting Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells to Bypass Tumor-Induced Immunosuppression. Front Immunol. 2018;9:398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Teratake Y, Takashina T, Iijima K, Sakuma T, Yamamoto T, Ishizaka Y. Development of a protein-based system for transient epigenetic repression of immune checkpoint molecule and enhancement of antitumour activity of natural killer cells. Br J Cancer. 2020;122:823-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Hellmann MD, Paz-Ares L, Bernabe Caro R, Zurawski B, Kim SW, Carcereny Costa E, Park K, Alexandru A, Lupinacci L, de la Mora Jimenez E, Sakai H, Albert I, Vergnenegre A, Peters S, Syrigos K, Barlesi F, Reck M, Borghaei H, Brahmer JR, O'Byrne KJ, Geese WJ, Bhagavatheeswaran P, Rabindran SK, Kasinathan RS, Nathan FE, Ramalingam SS. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2020-2031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1360] [Cited by in RCA: 2111] [Article Influence: 301.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/