Published online Dec 28, 2025. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v17.i12.114595

Revised: October 13, 2025

Accepted: November 3, 2025

Published online: December 28, 2025

Processing time: 93 Days and 23.1 Hours

Developmental venous anomalies (DVAs) are benign congenital veins that collect normal brain drainage into a single outlet. Cerebral cavernous malformations (CMs) are clusters of thin-walled capillary cavities prone to bleeding. When both lesions coexist, the DVA’s altered venous pressure and flow can promote CM formation or rupture. Detecting a DVA abutting an otherwise unexplained intra

Core Tip: When developmental venous anomalies (DVAs) and cerebral cavernous malformations (CMs) coexist, the DVA’s altered venous pressure and flow can promote CM formation or rupture. Detecting a DVA next to an otherwise unexplained intracerebral hemorrhage can therefore raise suspicion of an occult CM as the underlying etiology. This finding can represent a clue that may be invaluable for daily clinical practice. This review aims to educate readers on the hallmark imaging ap

- Citation: Arkoudis NA, Siderakis M, Tsetsou I, Efthymiou E, Triantafyllou G, Chalmoukis D, Karachaliou A, Papadopoulos A, Prountzos S, Moschovaki-Zeiger O, Gouliopoulos N, Papakonstantinou O, Filippiadis D, Velonakis G. Developmental venous anomalies and cerebral cavernous malformations: Partners in crime. World J Radiol 2025; 17(12): 114595

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v17/i12/114595.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v17.i12.114595

Vascular malformations (VMs) of the brain are generally rare and are commonly classified according to their hemodynamics (typically as low- or high-flow) or according to the kind of blood vessel that can be found histologically[1]. Developmental venous anomalies (DVAs), cavernous malformations (CMs), and capillary telangiectasias all involve the venous circulation.

The term DVA, previously venous angioma, cerebral venous malformation, or cerebral venous medullary malformation, was introduced by Lasjaunias et al[2] to emphasize its role as a variation of the brain venous microarchitecture rather than a true VM[3]. DVAs form when radially-oriented veins converge into a collecting vein draining into the deep or super

DVAs are the most common VMs, accounting for approximately 50% of all malformations observed in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies[6]. Their incidence is estimated to be as high as 2.6% in older autopsy studies, while more recent, imaging-based studies have reported an even higher incidence of up to 6.4%[4,5,7]. They are often discovered incidentally during brain imaging, such as computed tomography (CT) and MRI.

DVAs collect blood from the surrounding normal parenchyma and may act as a compensatory venous channel[8]. They represent an alternative venous outflow in case of the absence of normal subependymal or pial veins[3]. There are reported fatal complications after the surgical removal of a DVA, probably due to their important role as compensatory channels[5,9]. DVAs are more often located in the supratentorial brain parenchyma (70%) rather than the infratentorial brain (14%-29%). Supratentorially, they are predominantly found in the frontal lobes (36%-56%), followed by the parietal (12%-24%), temporal (2%-19%), and occipital (4%) lobes. Infratentorially, they are located in the cerebellum (14%-29%) and brainstem (< 5%)[10-12]. They have a wide range in size, ranging from just a small volume of the brain parenchyma to a whole brain hemisphere[5].

Histologically, they lack malformed or neoplastic elements, consisting of mature venous walls without arterial or capillary components. They may show degeneration, such as hyalinized and thickened walls. Unlike “true” VMs, their walls contain normal structural proteins, whereas VMs express angiogenic growth factors and exhibit histological fragility[6]. “Arterialized” or “fistulized” DVAs, also known as mixed-type malformations or intracerebral venous angiomas with arterial supply, are VMs that combine a DVA with an arterial component. They retain the characteristic structure of a DVA while exhibiting arteriovenous shunting, which becomes apparent during the arterial phase of angiographic imaging[5,6].

Their etiology remains unclear. The prevailing hypothesis suggests that DVAs arise from errors in venous development during embryogenesis, involving aberrant formation of normal veins and their tributaries[13,14]. As a compensatory response, the brain develops alternative venous drainage pathways during gestation and early infancy. This adaptive process implies the occurrence of an underlying pathological event in utero. Reports on DVAs in neonates are much fewer than in adults[15,16]. Despite the widespread use of MRI (in utero) and cranial ultrasound (cUS), there is limited information on their prevalence in the pediatric population[17]. Their incidence increases with age, with Brinjikji et al[15] reporting a prevalence of 1.5%, 7.1%, 9.6%, and 9.6% in neonates, toddlers, children, and adults, respectively. This discrepancy may be due to underreporting, as they are considered benign. It also suggests that DVAs may either develop postnatally or remain dormant until required.

Before the widespread utilization of CT and MRI, DVAs were thought to cause major hemorrhagic events and seizures. Today, they are considered benign and asymptomatic. However, in a very small number of cases, they can lead to symptoms due to mechanical or flow-related complications[18]. Pereira et al[19], examining both adults and children, excluding cases with co-existing CMs, identified several mechanisms responsible for symptoms. These included thrombosis leading to infarction or hemorrhage, increased inflow, decreased outflow, mass effect, and parenchymal injury due to elevated venous pressure[19]. Most of the current evidence on symptomatic DVAs comes from case reports and series, making it difficult to determine their incidence and prevalence. When symptomatic, they may present with headache, seizures, focal deficits, dizziness, and ataxia, depending on their location and mechanism[19,20]. It is hypothesized that the brain parenchyma, which is drained by a DVA, shows less physiological reserves and is more vulnerable to injury. Since they constitute a less efficient drainage route, with time, they result in venous hypertension locally[11,14]. The venous congestion may result from stenosis or thrombosis of the collector veins or increased resistance in the vessel walls[21]. Demyelination, gliosis, ischemic changes, and neuronal degeneration have been observed in the brain parenchyma surrounding DVAs[11]. Thrombosis of the collecting vein is rare and can present in various ways, such as venous infarction, parenchymal hemorrhage, edema, or subarachnoid and intraventricular hemorrhage[20,21]. Current belief is that most hemorrhagic events result either from associated regional CMs or as a consequence of thrombosis of the DVA[5,22]. The annual hemorrhage risk of DVA-only lesions is 0%-1.28%, whereas most clinically significant hemor

While VMs are a known factor for epilepsy and seizures, there is limited evidence supporting DVAs as epileptogenic foci[23,25]. They may be identified during an epilepsy workup, but usually no direct correlation can be found. Some reports have mentioned seizures caused by DVA complications, such as thrombosis or hemorrhage, but direct links are rare[25]. In most cases, the seizures can be attributed to an accompanying cryptic VM or another epileptogenic lesion. DVAs can also be present in regions of malformed cortical development, such as focal cortical dysplasia, pachygyria, or polymicrogyria, which could point to a common developmental event[26]. For patients with seizures and an incidental DVA, a thorough evaluation is needed to identify any other potential causes[6].

In case of a headache, the presence of a DVA is usually an incidental finding during imaging, as most headaches resolve over time with no intervention[3,24]. However, a complicated DVA could lead to a headache[6]. Mass effect on surrounding structures can lead to various complications depending on the location of the DVA, such as cranial nerve compression or hydrocephalus[19]. There are reports of trigeminal neuralgia, tinnitus, and hemifacial spasm attributed to a DVA located in the cerebellopontine angle affecting the trigeminal and facial nerves, respectively[27-30].

DVAs have also been associated with atrophy of the surrounding parenchyma, likely due to altered venous outflow and chronic venous congestion[18]. Uchino et al[31] described a case with severe brain hemiatrophy in the context of a large DVA with enlarged, varicose drainage veins. Another reported finding is the presence of basal ganglia calcifications[18,32]. These calcifications may result from prior hemorrhage or venous congestion[5].

Understandably, any DVA that presents with neurological symptoms should prompt further investigations to exclude a cryptic accompanying VM or other lesion[6]. DVAs commonly coexist with other VMs, particularly CMs (as will be discussed below in detail). They can also coexist with sinus pericranii, a VM comprised of a communication between intracranial and extracranial veins via dilated venous channels[33]. Up to 50% of these lesions have been associated with DVAs and act as their draining channel[5,18]. Some authors support that sinus pericranii could represent an extraaxial DVA, suggesting they represent a variant anatomy[33,34]. DVAs are encountered in approximately 20% of patients with superficial venous malformations of the head and neck, which is higher than the general population[35,36]. When both a maxillofacial VM and a DVA are present, the criteria for cerebral venous metameric syndrome are met. This syndrome is a complex craniofacial disorder involving VMs in soft tissues, neural structures, and bones[37].

DVAs are also associated with lymphatic malformations of the orbital and periorbital regions[38]. DVAs can be observed in patients with blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, a rare neurocutaneous disorder characterized by multifocal venous VMs of the skin (hands and soles) and gastrointestinal tract[39]. Other rarer genetic syndromes linked to DVAs are constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome, Cowden syndrome, and diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas[18,40]. For example, a study found that 59.1% of patients with Cowden syndrome had at least one DVA, and 36.4% had multiple DVAs[41]. In addition, CMs (discussed below in detail) can also sometimes be found in individuals with Cowden syndrome[41,42]. While neither DVAs nor CMs are core diagnostic features of Cowden syndrome, their identification on brain MRI, along with other findings (i.e., dysplastic cerebellar gangliocytoma), can prompt genetic testing and a more comprehensive evaluation for the condition. Nonetheless, a diagnosis of Cowden syndrome will typically be based on a combination of clinical findings, including mucocutaneous lesions, macrocephaly, and cancer risks, along with confirmation through phosphatase and tensin homolog gene mutation analysis[41].

There is growing interest in exploring a potential association between DVAs and demyelinating diseases, particularly multiple sclerosis. Jung et al[43] have published a case report demonstrating focal demyelination around a cerebellar DVA. Additionally, Rogers et al[44] published a small case series with patients with multiple sclerosis and accompanying DVAs. However, current evidence is poor, and further research is required.

DVAs are usually encountered incidentally on post-contrast brain CT and MRI and on conventional and digital subtraction angiography (DSA)[45]. They can also be assessed using advanced techniques, typically performed for other reasons, such as cUS in neonates, single photon emission CT, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and perfusion studies, including arterial spin labeling (ASL) perfusion and bolus perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI)[46,47].

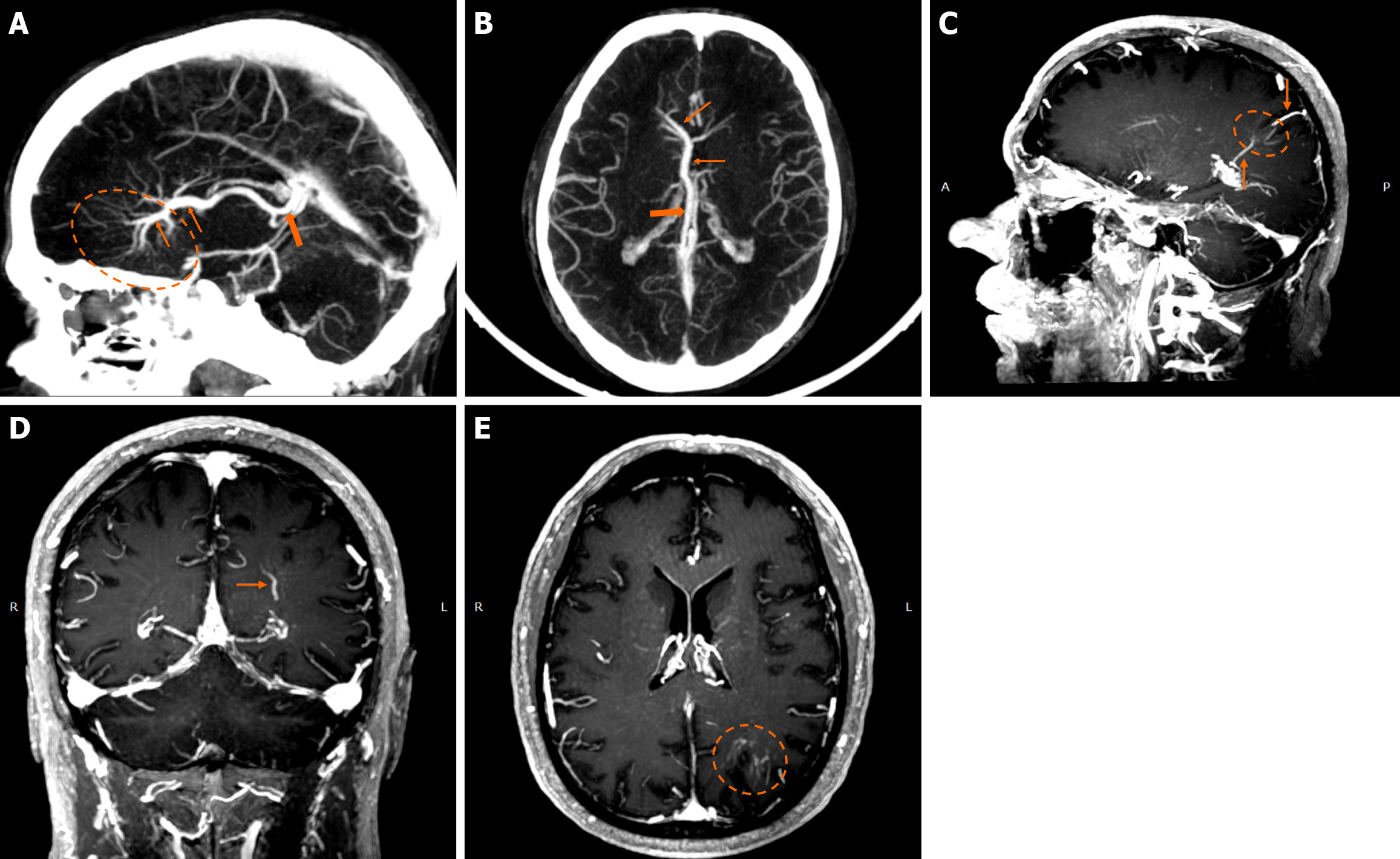

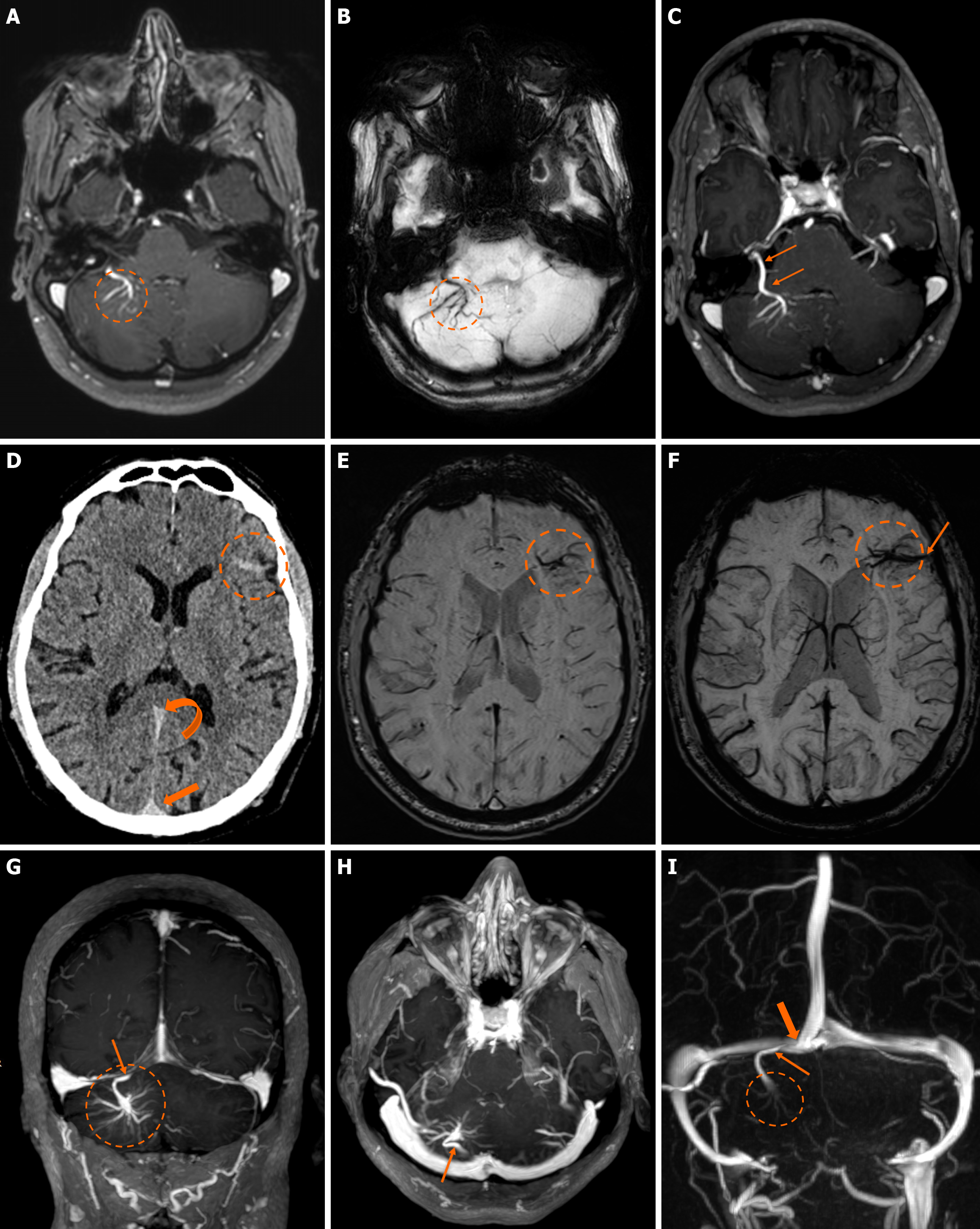

On non-contrast CT, smaller DVAs may not be visualized, while larger ones with a patent collecting vein may appear isodense or slightly hyperdense compared to the brain cortex. A thrombosed collecting vein may appear markedly hyperdense[45]. Non-contrast scans can also assess locoregional parenchymal abnormalities (i.e., calcifications) in the drainage territory[48]. Post-contrast brain CT, typically performed 2-3 minutes after contrast administration, provides clearer visualization of the characteristic “caput medusae” morphology and the collecting vein, both of which enhance[10]. A “caput medusae” morphology is defined as multiple radially oriented veins that converge centrally to the collecting channel[49]. Dedicated CT angiography, usually with bolus tracking, and/or venography with 50 second-delay can provide more information on the morphology of the DVA but are usually not necessary[3,5]. Some DVAs may show ampullary dilatation of their proximal portion at the convergence of the medullary veins[10]. Newer CT technologies with dynamic subtracted angiography provide more detailed morphological visualization[5].

Parenchymal changes surrounding a DVA are not a rare occurrence and can be seen in up to 65%, as reported by San Millán Ruíz et al[10]. According to their study, the most common finding was atrophy (29.7%), followed by white matter lesions (WML) (19.3%) and dystrophic calcifications (9.6%)[10]. Brain atrophy varies, ranging from focal enlargement of a sulcus or ventricle to atrophy of the entire drainage area or even a brain hemisphere[13,31,50]. WML can occasionally be assessed with CT, but is more frequently observed in MRI due to its higher sensitivity. They resemble leukoaraiosis from other causes, such as microvascular disease, and appear as well-circumscribed non-enhancing hypodensities around the DVA[10]. Dystrophic calcifications are not unique to DVAs and are also described in other VMs, such as dural arteriovenous fistulas and in Sturge-Weber syndrome[48]. They are often overlooked due to the benign nature of DVAs, but can be seen in the surrounding white matter or basal ganglia[10]. They are better appreciated in CT rather than MRI studies and are typically unilateral[48].

DVAs are often detectable across various MRI sequences but are most clearly visualized on post-contrast T1-weighted (T1w) and susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) sequences[7]. Smaller DVAs can be overlooked, even in post-contrast series. In a study by Gökçe et al[7], almost half of the DVAs were not visible on non-contrast sequences. The collecting vein is more easily visualized than the “caput”[12]. DVAs typically appear as flow voids on both T1w and T2w sequences and may demonstrate phase-shift artifact[3]. The radicles may sometimes have a high signal at fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images, which should not be confused with parenchymal changes[51]. They show homogeneous enhancement after gadolinium contrast administration. Their visualization is enhanced by three-dimensional (3D) gradient-echo (GE) T1w sequences, which provide high-resolution imaging and allow for multiplanar reconstructions[45]. Application of 3D sequences can also allow better morphological assessment, such as stenosis of the collecting vein[5]. MR venography and time-of-flight angiography are usually not necessary, and their role is to evaluate whether there are signs of arterial components[4]. Nonetheless, non-arterialized but large DVAs may also be visualized at time-of-flight images.

SWI is very sensitive in detecting pathologies that cause inhomogeneity of the magnetic field[45]. A DVA appears as a low-signal structure on SWI and T2* sequences. In phase imaging, its signal remains consistent with other veins but is inverted relative to that of calcifications[45]. SWI provides a more detailed assessment of the entire structure and has been shown to be more sensitive than conventional T2*-weighted imaging. SWI is not significantly affected by low velocities, making it very effective to assess low-flow lesions such as DVAs[52,53]. SWI in high and ultra-high field strengths (3T and 7T) can better visualize a DVA[54].

MRI is superior to CT in evaluating parenchymal abnormalities[3]. WML appears as high-signal areas on T2/FLAIR and low-signal areas in T1w sequences without diffusion restriction, mass effect, or contrast enhancement[5]. 3D FLAIR is more sensitive in detecting these lesions[51]. They can range from small foci to a large confluent lesion in the drainage territory[10]. Their incidence ranges from 11.6%-30.7% and tends to occur more frequently in older patients[10,11,55,56]. They likely represent edema, gliosis, ischemia, demyelination, or glial metaplasia[55,56]. A case series by Jung et al[56] evaluated the apparent diffusion coefficient values of the WML and showed increased values compared to normal parenchyma, possibly due to congestion. Takasugi et al[57] found hypointense foci on SWI within the drainage territory in 59% of cases, which were more common with WML, likely representing microhemorrhages or tiny CMs.

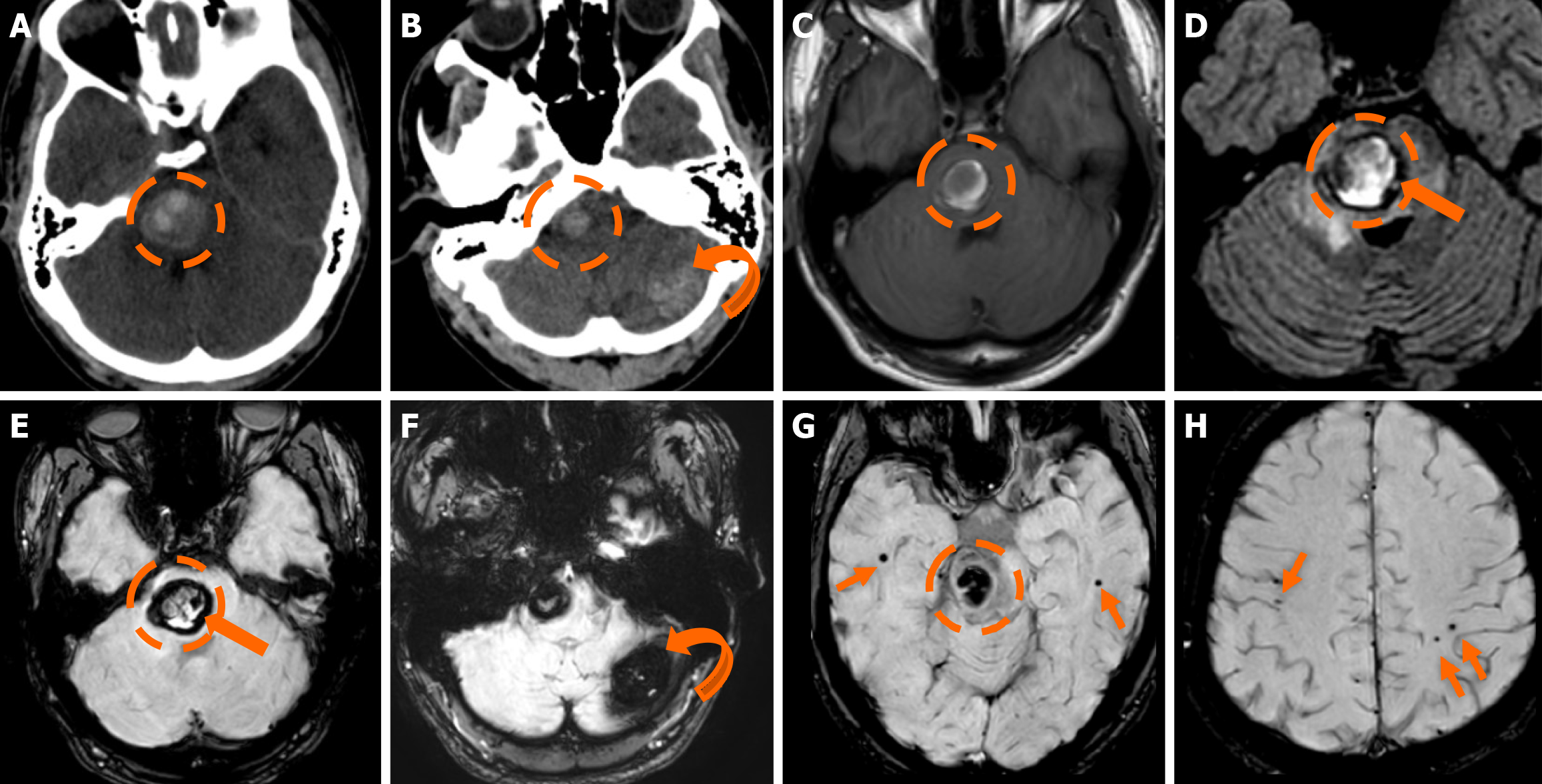

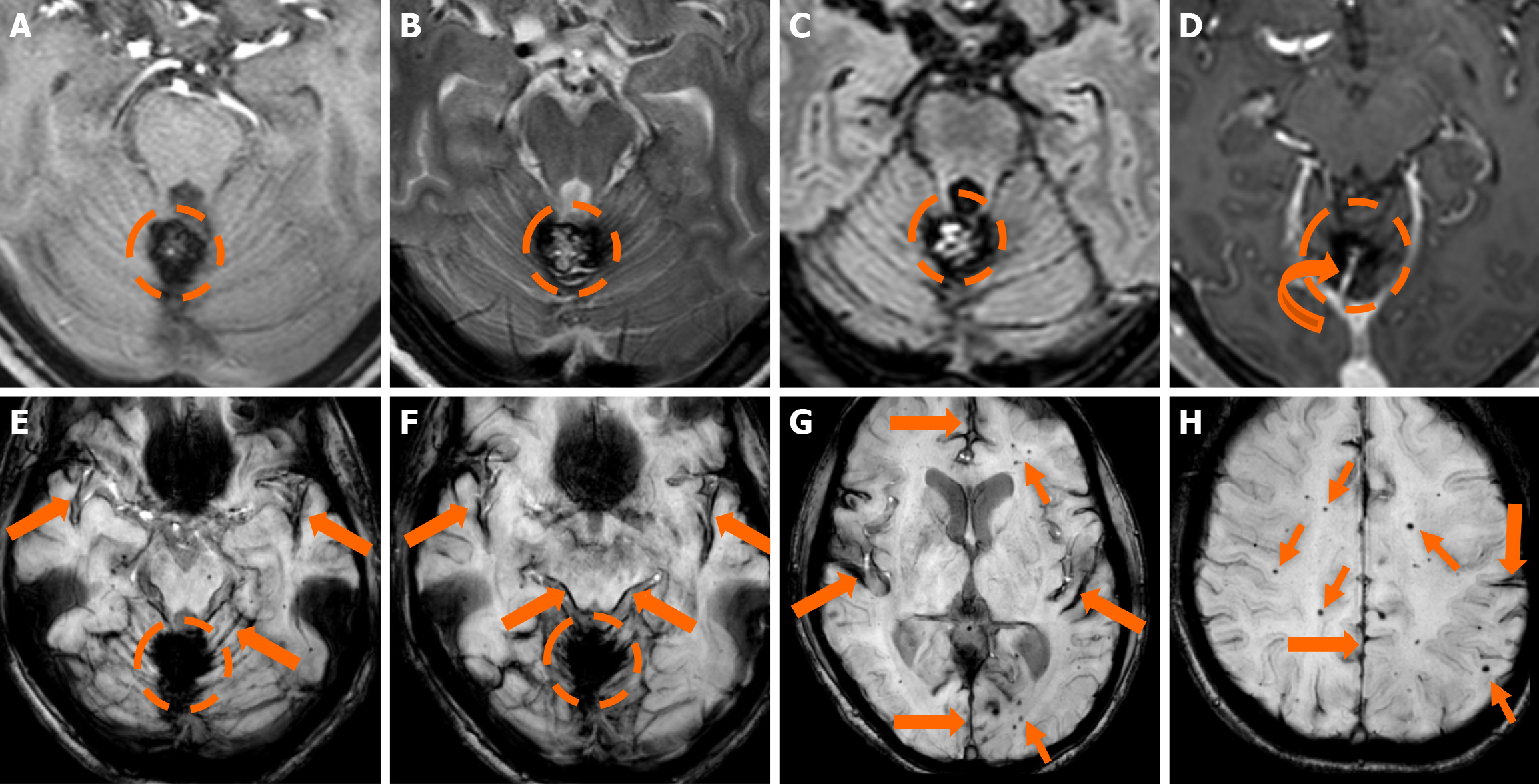

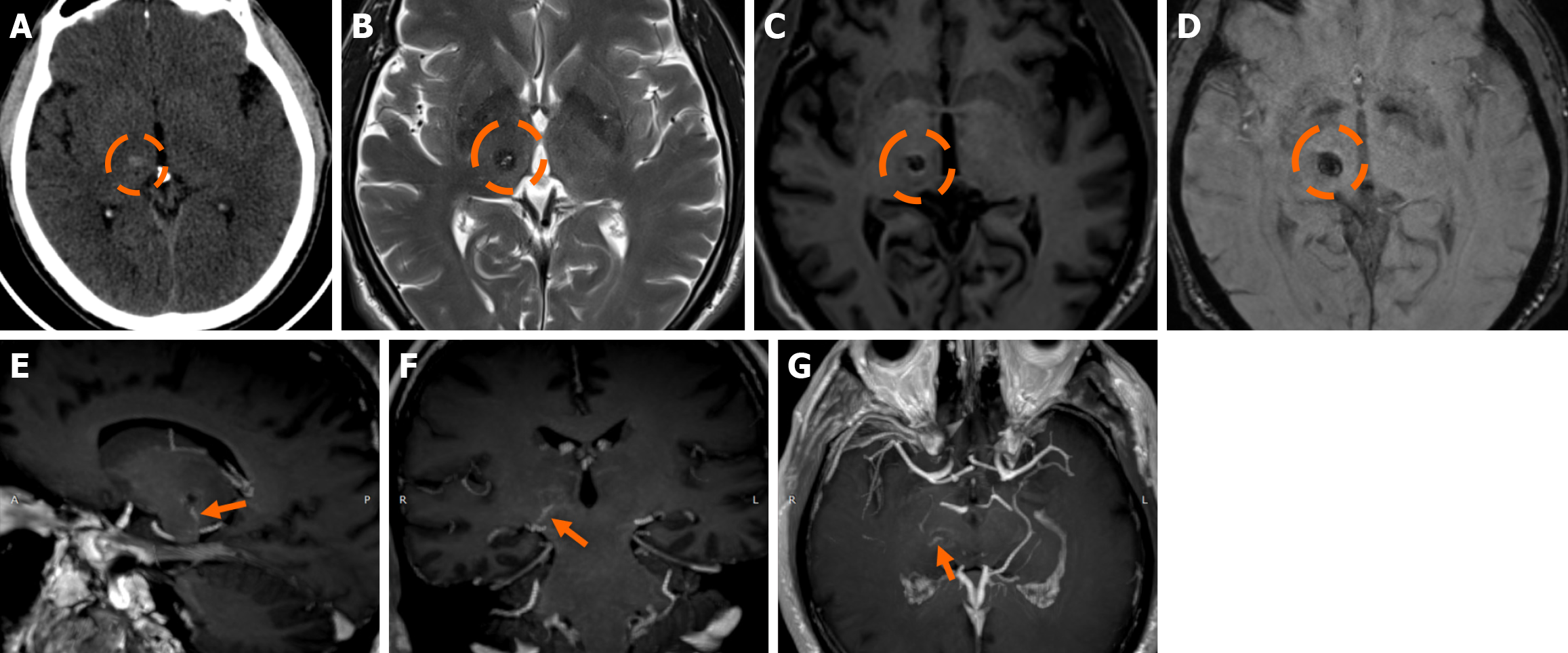

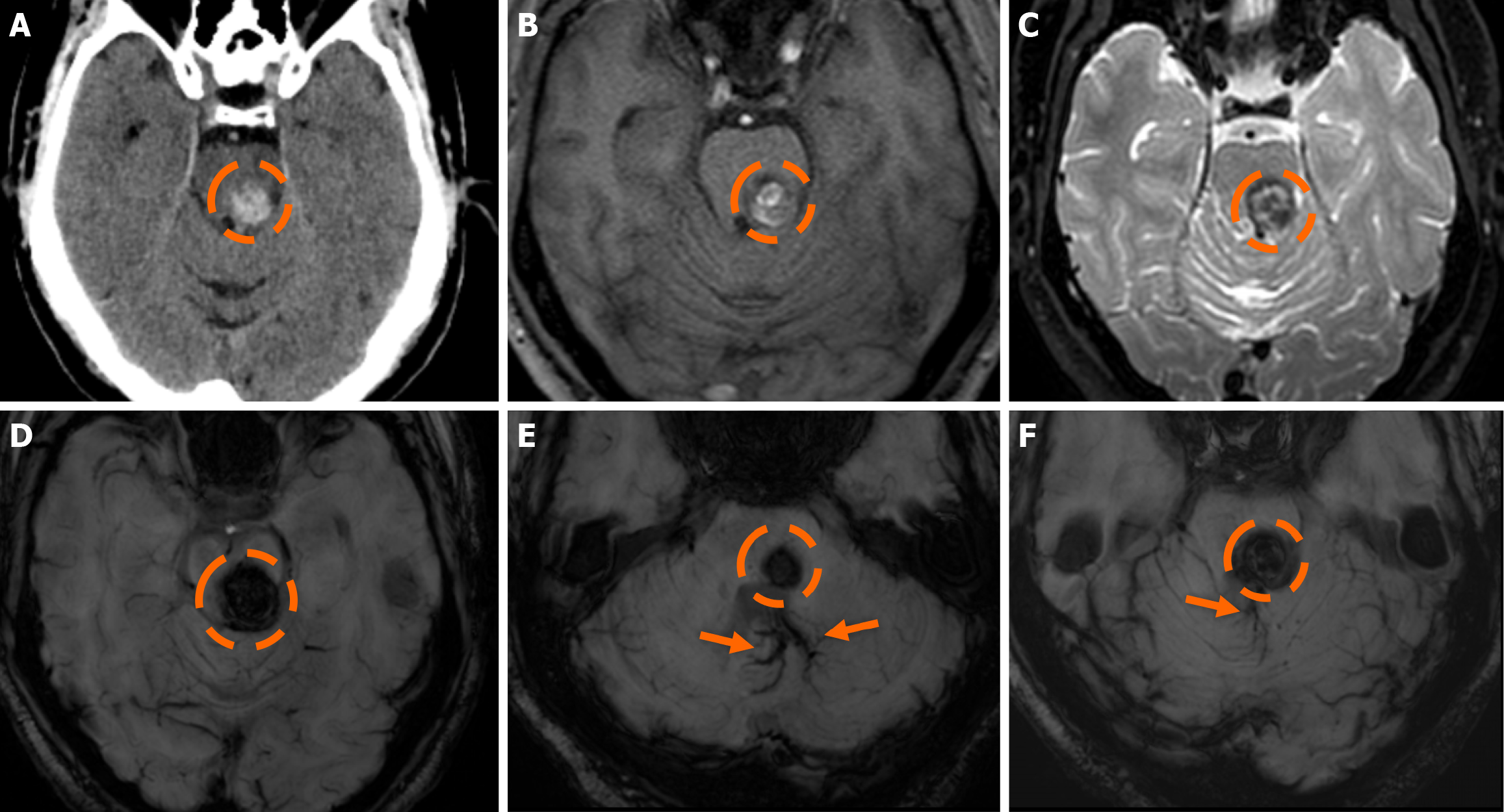

Functional MRI (fMRI) depends on blood oxygen level-dependent contrast, and changes are attributed to both extravascular tissue and local capillaries and veins. Theoretically, DVAs can contribute to the fMRI signal and can potentially lead to pseudoactivations during presurgical mapping[58]. Various examples of DVAs on CTs and MRIs are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Perfusion studies such as PWI, ASL, and CT have shown that the normal-looking parenchyma surrounding a DVA may show hemodynamic abnormalities, even in uncomplicated DVAs[47,59]. Hanson et al[47] performed CT perfusion studies and found increased cerebral blood volume (CBV), cerebral blood flow (CBF), and mean transit time (MTT) in the hemi

CT and/or MRI findings alone are adequate to characterize a VM as a DVA. Angiography has a role in symptomatic DVAs and those with atypical presentations, such as hemorrhage, in order to determine the true cause of bleeding[3,45]. A DVA opacifies at the same time as normal veins, although those located in the frontal lobes may opacify earlier, showing a capillary blush[59]. In case of hemorrhage, DSA clearly demonstrates the “caput medusae” in the area affected by hemorrhage with signs of venous obstruction, such as venous stasis, a missing collector (in case of thrombosis), and delayed washout[7]. DVAs with accompanying VMs, arteriovenous shunting, and “arterialized” DVAs demonstrate capillary blush during the arterial phase and early venous filling[5,7,45].

Horsch et al[16] described the imaging findings of DVAs in a case series using cUS. The vast majority demonstrated hyperechoic brain parenchyma surrounding a DVA, a finding that did not correlate with MRI findings in most cases[16,51]. Most of the DVAs exhibited venous waveforms on Doppler, while a few showed arterial-like form[16]. It is unknown whether those lesions represented “arterialized” DVAs.

In the vast majority of cases, DVAs do not require follow-up or treatment. In case of thrombosis, there are reports of successful anticoagulation therapy[20,63-65]. Current belief is to treat a thrombosed DVA similarly to cortical or dural venous sinus thrombosis and to screen for prothrombotic conditions[3,5]. However, there is not enough evidence to support it[3,14]. The decision to initiate anticoagulation should be carefully assessed, considering the potential risk of hemorrhage. Resection of a DVA is contraindicated, as they act as compensatory venous channels and previous resections have led to fatal complications due to venous infarction[1,5,9]. A neurosurgeon should be informed in advance to avoid accidental resection. If surgery is necessary due to a complication, such as hemorrhage or edema, careful preservation of the DVA’s collecting vein is crucial to prevent complications[6,20]. Hemorrhagic “arterialized” DVAs are believed to follow a more aggressive clinical course with higher hemorrhage risk[5,6]. They have been managed using surgery, proton beam radiosurgery, embolization, and gamma knife treatment[14,66-69]. Unintentional surgical removal of the DVA component led to acute deterioration, while gamma knife treatment targeting the DVA resulted in radiation necrosis, likely due to venous congestion[68,70]. Treating asymptomatic “arterialized” DVAs should be carefully considered on a case-by-case basis, targeting the arterial component.

CMs, also known as cavernous angiomas, cavernous hemangiomas, cryptic VMs, or cavernomas, are low-flow vascular lesions, mainly encountered in the supratentorial region (63%-81%) but could also be found in infratentorial white matter, mainly the pons and cerebellar hemispheres, as well as the spinal cord. Although relatively rare in the general population (0.4% to 0.8%), they represent the second most common cerebral VM, accounting for approximately 5%-15% of all vascular anomalies[71]. The majority of cases (85%) arise sporadically, while the remaining 15% are associated with familial inheritance or radiation exposure[71]. No gender differences have been reported[72]. CMs are occasionally found alongside a DVA, a condition known as a mixed VM. Recognizing the presence of an associated DVA on imaging is crucial, as it can assist in correct diagnosis and guide surgical decisions, since DVAs serve as essential venous drainage routes, and any disruption can lead to venous infarction or increased complications. The presence of a DVA is more commonly linked to the nongenetic familial variant of the disease[73]. Moreover, occasionally, CMs coexist with capillary telangiectasia, indicating that these lesions may be part of the same pathological entity[74,75].

In most cases, they are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally. Clinical manifestations include hemorrhage, epileptic seizures, and neurological deficits. Hemorrhagic risk is estimated between 2% to 6% per year and increases with a history of previous hemorrhage, brainstem location, as well as familial predilection[76,77]. Furthermore, factors such as age, female sex, deep white matter location, size, multiplicity, and the presence of associated DVAs have not been associated with increased hemorrhagic risk[77]. The annual incidence of seizures in individuals with CMs ranges between 1.5% and 2.4%[76].

They are composed of abnormally dilated, thin-walled capillary networks devoid of normal intervening brain paren

The sensitivity of CT in detecting CMs is limited, with a detection rate ranging between 30% and 50%[79]. Sensitivity decreases significantly in smaller lesions (< 1 cm)[74,75]. CMs do not exhibit distinct imaging characteristics; they typically appear as well-defined lesions that may be either hypodense or hyperdense, depending on the presence of calcifications and hemosiderin deposits. Following contrast administration, mild enhancement may be observed. Edema or mass effect is uncommon unless a recent hemorrhage has occurred[80]. CT is typically the initial and preferred imaging modality in acute settings to rule out hemorrhage[81].

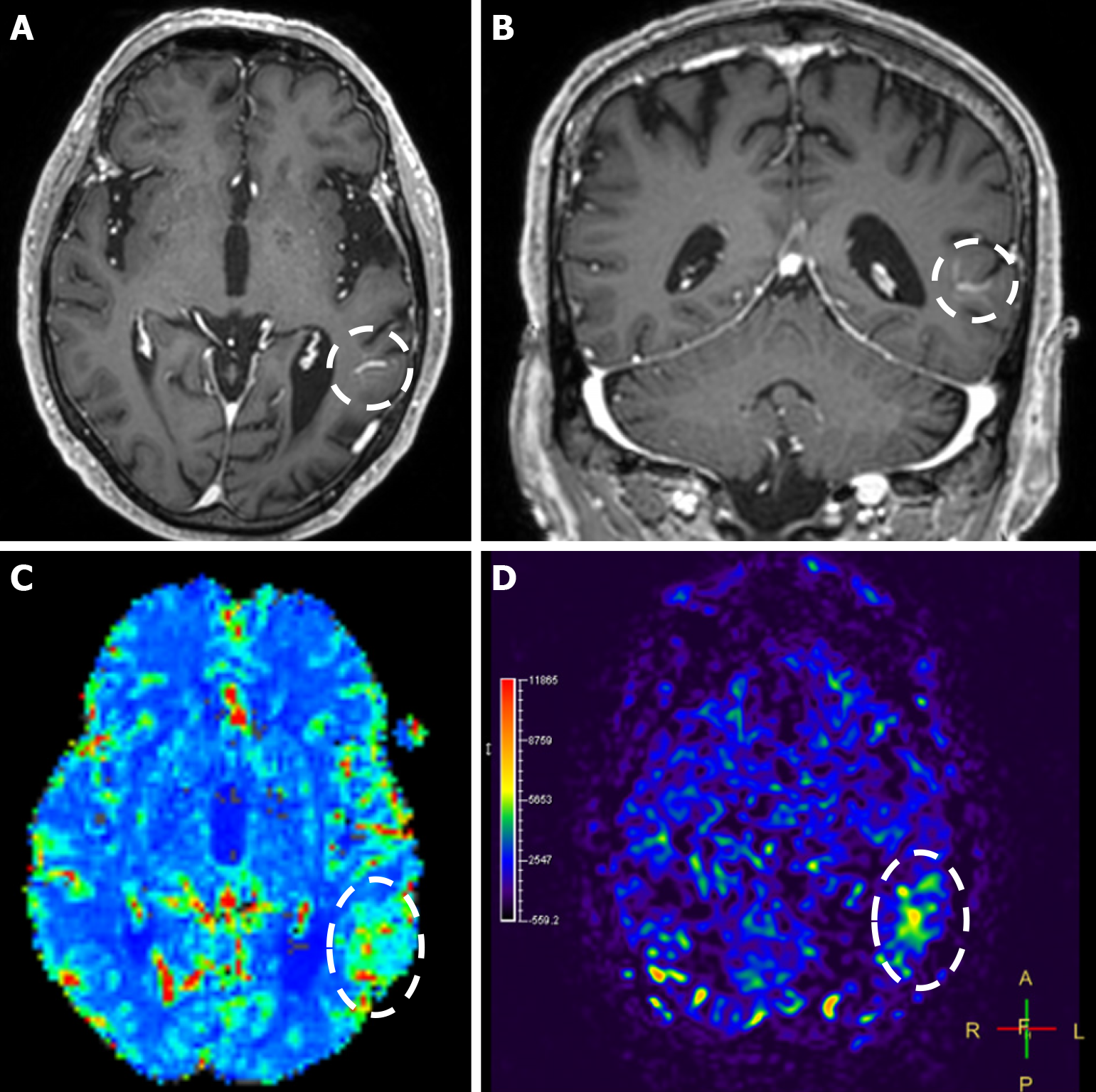

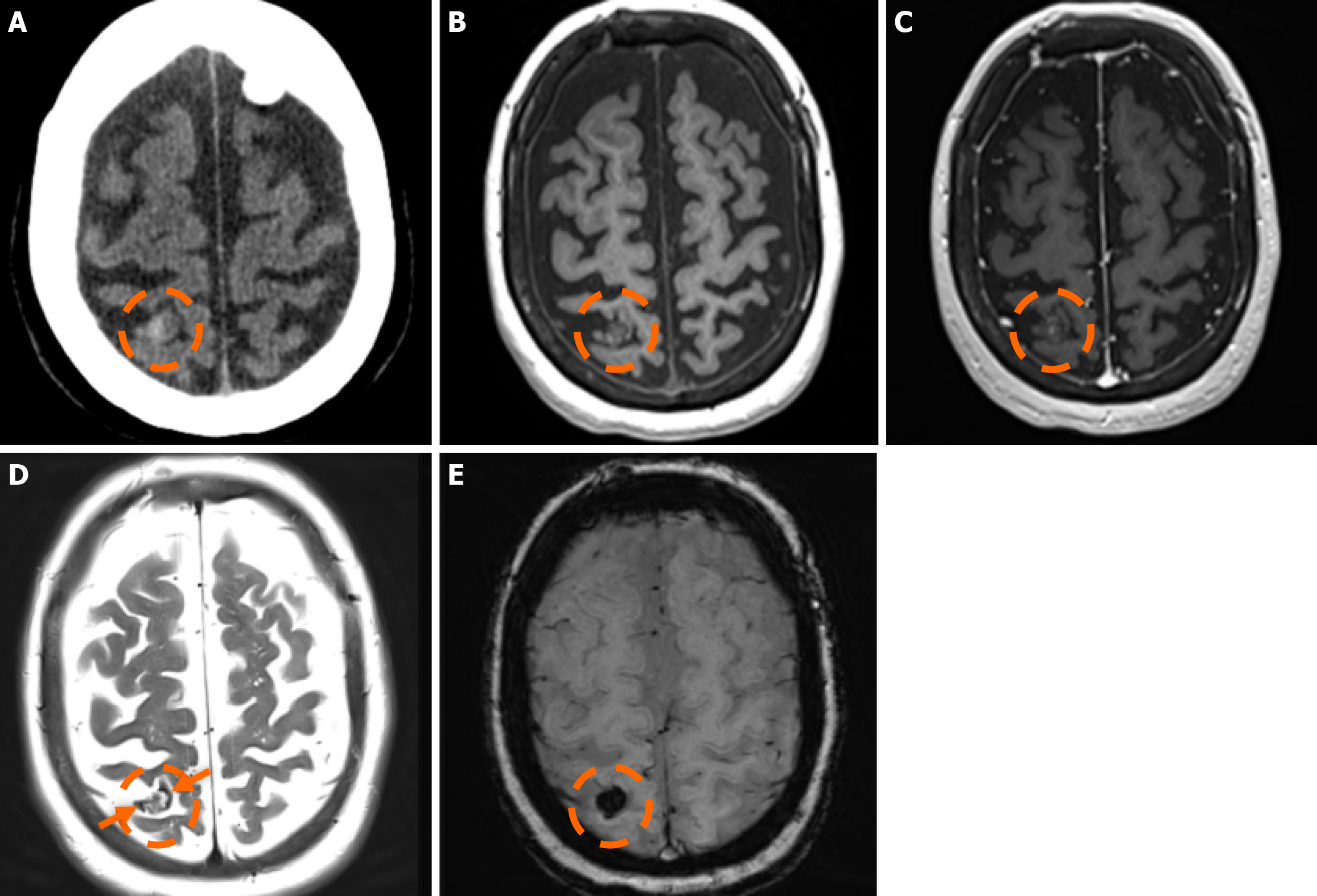

MRI remains the gold standard for detecting and further characterizing CMs[81]. Conventional MRI sequences, particularly T1w and T2w imaging, exhibit high sensitivity and specificity for identifying clinically symptomatic CMs[75]. Their signal characteristics on MRI vary depending on lesion size and hemorrhagic status. Small, punctate lesions typically appear hypointense on T2w imaging. In contrast, larger CMs exhibit a characteristic reticulated pattern of mixed hypo- and hyperintense signals, resembling the so-called “mulberry-like” or “popcorn” appearance on T2 and FLAIR sequences. Increased signal in T1 sequences reflects the presence of methemoglobin, indicative of subacute hemorrhage. A characteristic hypointense rim surrounding the lesion could also be noted. Usually, CMs lack prominent enhancement, while they could exhibit low to moderate enhancement, particularly if there is associated blood-brain barrier disruption, recent hemorrhage, or adjacent gliosis. Additionally, the presence of deoxyhemoglobin and hemosiderin results in susceptibility effects, leading to a decrease in signal intensity on T2w sequences. Thus, GE sequences and particularly T2*-weighted have proven valuable in the detection of CCMS. Multiple studies have demonstrated that T2w GE (GRE) imaging offers increased sensitivity compared to other MRI sequences for the detection of sporadic and familial cases of CM lesions[80].

SWI represents an advanced imaging technique particularly well-suited for the detection of VMs, owing to its high sensitivity to deoxyhemoglobin and iron deposition. SWI has demonstrated higher sensitivity compared to GRE imaging in the detection of CMs, especially in familial cases[82,83]. Moreover, SWI also provides enhanced sensitivity for the detection of associated venous anomalies and potential telangiectasias, especially in cases where contrast media is contraindicated[84]. Nevertheless, the hemosiderin-induced “blooming effect” could artifactually exaggerate the apparent size of the lesions; thus, both GRE and SWI sequences should be interpreted carefully[84]. Additionally, small hemor

In 1994, Zabramski et al[87] proposed an MRI-based classification system for CMs, based on their imaging characteristics, particularly on T1w, T2w, and susceptibility-sensitive sequences, which remains one of the most widely used methods for characterizing these lesions. The classification system is outlined in Table 1.

| T1 | T2 | GRE/SWI | Clinical manifestation | |

| I (subacute hemorrhagic lesions) | Hyperintense center | Hyper or hypointense center, surrounded by a hypointense (hemosiderin) rim | - | Usually symptomatic |

| II (classic “popcorn-like” lesions) | Heterogeneous signal | Heterogeneous and hypointense (hemosiderin) rim | Hypointense (hemosiderin) rim with blooming | The most prevalent type of cavernous malformation; recurrent asymptomatic or symptomatic episodes |

| III (chronic lesions) | Hypointense or isointense | Hypointense or isointense | Hypointense rim with blooming (marked hemosiderin deposition) | Clinically silent |

| IV (punctate lesions) | Poorly seen | Poorly seen | Small, punctate hypointense foci | Asymptomatic |

Type I lesions exhibit a hyperintense core on T1w imaging, indicative of subacute hemorrhage due to methemoglobin accumulation. The lesion’s size and intensity may fluctuate over time, reflecting the dynamic nature of the hemorrhagic process[88]; Type II lesions, considered the most prevalent type, exhibit the classic “popcorn-like” imaging, displaying a heterogeneous core with mixed signal intensities on both T1w and T2w sequences and a well-defined hypointense hemosiderin ring on T2-GRE or SWI images; Type III lesions represent chronic hemosiderotic lesions, appearing hypointense or isointense on T1w and T2w MRI, demonstrating ‘’blooming effect’’ on T2-GRE or SWI, indicating prior hemorrhagic activity; and Type IV lesions include small punctate lesions, mainly visualized on susceptibility-sensitive sequences (T2-GRE or SWI). Classifying lesions as type IV could be challenging, as their exact pathological nature has not been definitively determined[85].

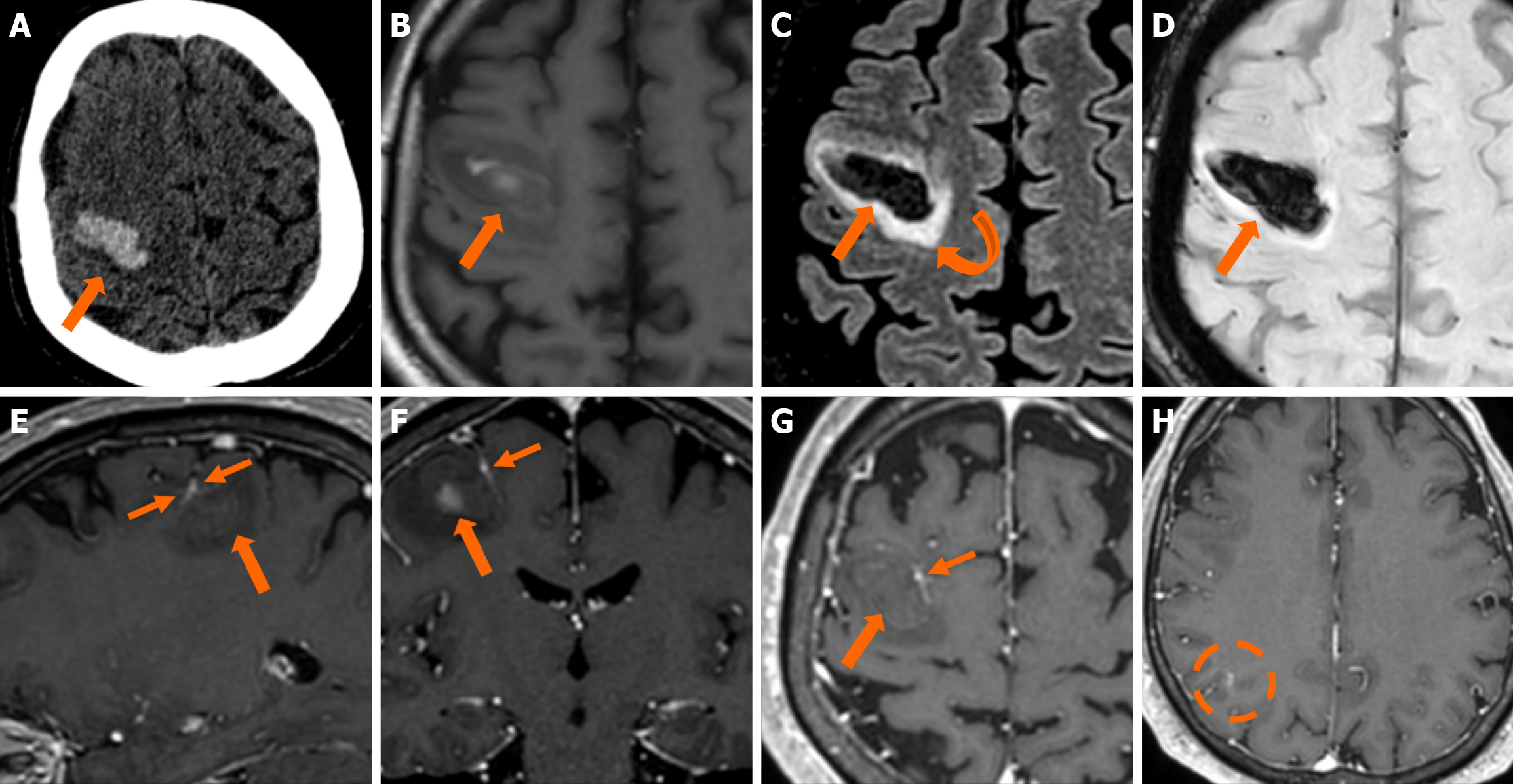

The clinical applicability of the Zabramski classification is still being investigated. A retrospective cohort study evaluating the imaging evolution and clinical trajectory of 255 untreated patients with sporadic CMs over a follow-up period of approximately five years provided evidence that the Zabramski classification may facilitate risk stratification and contribute to treatment planning, particularly in determining the necessity for surgical intervention[89]. Furthermore, a recent study by Saari et al[88] established an association between the radiological characteristics of the Zabramski classification and their clinical relevance, emphasizing that type I lesions have a higher likelihood of becoming symptomatic. Nikoubashman et al[90] suggested an additional category (type V lesions) accounting for cavernomas presenting with gross extralesional hemorrhage. Various examples of CMs on CTs and MRIs, including familial cerebral CM cases, are shown in Figures 4, 5 and 6.

DSA is not a routine tool for CMs, as they are angiographically occult. DSA has been proven particularly useful in cases with atypical imaging or clinical features, to exclude alternative VMs[81].

The imaging characteristics of CMs are relatively distinctive, with a narrow differential diagnosis. Nevertheless, acute or subacute hemorrhage could obscure their characteristic imaging features, thereby complicating accurate diagnosis. In the setting of recent hemorrhage, affected lesions often appear as well-circumscribed, space-occupying lesions, frequently associated with perilesional edema and mass effect. The differential diagnosis includes both neoplastic and non-neoplastic entities, such as gliomas, metastases, hemorrhagic stroke, and arteriovenous malformations. The diagnostic challenge increases when multiple punctate lesions are detected on SWI/GRE imaging, as their appearance overlaps with various other pathological entities, including hemorrhagic metastatic disease, hypertensive microangiopathy, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, and traumatic diffuse axonal injury[80]. Recurrent hemorrhagic episodes, the presence of a hypointense hemosiderin rim on T2-GRE or SWI, and well-defined lesion encapsulation are key imaging features that strongly support CM diagnosis. On the other hand, significant mass effect, homogeneous single-aged blood products, and expansile hemorrhage are quite uncommon in CMs and more indicative of other pathologies, including arteriovenous malformations[91].

The presence of T1 hyperintensity within perilesional edema surrounding a hemorrhagic lesion has proven to be a valuable diagnostic feature, aiding in the differentiation of CMs from other hemorrhagic lesions[92]. The same authors also reported a significantly higher occurrence of the hypointense signal or rim on T2-weighted images in CMs compared to neoplastic lesions[92]. In cases where CMs occur in atypical locations, such as the cavernous sinus or extraaxial regions, the differential diagnosis becomes more complex, as these lesions may mimic other vascular, neoplastic, or inflammatory lesions, necessitating careful imaging interpretation and, in some cases, additional diagnostic workup. In addition, identifying a DVA within the vicinity of a hemorrhagic brain lesion may strongly suggest an underlying CM as the incriminating etiology, further representing a clue that can assist in the differential diagnosis approach.

In asymptomatic cases, surgical resection may be an option for a solitary CM in a noneloquent area and easily accessible, aiming to decrease the risk of future hemorrhage. However, surgery is generally recommended for CMs associated with epilepsy, as well as for symptomatic, easily accessible lesions when the surgical risks are comparable to those of living with the condition for approximately two years[81]. Managing infratentorial: CMs are particularly challenging due to the high risk of early postoperative mortality and morbidity. In such cases, surgical intervention is typically reserved for patients who have experienced a second symptomatic hemorrhage[81]. Radiotherapy may serve as an alternative treatment for solitary CMs that have previously led to symptomatic hemorrhage, especially when the lesion is located in an eloquent brain region where the risks of surgical intervention are prohibitively high[81].

Over the past fifty years, the advancement of CT and the advent of MRI have enabled the work-up, diagnosis, and follow-up of patients with coexistent DVAs and CMs in the central nervous system (CNS). A series of studies have estimated the prevalence of DVA-CM coexistence to be up to 33% (Tables 2 and 3)[93-102]. Despite high-field MRI imaging, many authors, however, suggest that the prevalence of DVA-CM concurrence might have been underestimated because many small DVAs are missed on imaging and observed merely during operation time[101,103]. The location of the coexistent lesions, age of patients, and clinical presentation have been correlated with the concurrence of DVA-CM mixed malformations.

Abe et al[99] found that 83% of the DVA-CM lesions were infratentorial (25 out of 30 cases). In their retrospective analysis of 55 patients harboring CMs, Abdulrauf et al[100] observed a statistically significant difference between DVA-CM and CM-only cases; 67% of the mixed malformation cases were infratentorial, compared with 27% of the CM-only group. Interestingly, in a series of 86 patients who underwent resection of hemorrhagic brainstem CMs, all of them were associated with a DVA[104]. In a large study of 1689 individuals with DVAs, coexistence with CMs was observed in 6,9% (116/1689); DVA-CM lesions were more likely to be noticed in the brainstem than DVA alone (15.5% vs 3.2%) and basal ganglia or thalamus (6% vs 3.9%)[97]. The infratentorial location of a DVA increased the chance of coexistence with a CM, according to a large observational study by Meng et al[96], too. In 41 cases of cerebellar CMs, Zhang et al[102] observed 26.8% DVA-CM coexistence (11/41); no statistically significant difference was estimated regarding age, sex, size, and clinical presentation between patients with cerebellar CM alone and patients with DVA-CM coexistence in the cere

Brinjikji et al[97] observed a statistically significant correlation between age and DVA-CM coexistence. While the simultaneous presence of DVAs and CMs was noticed in < 1% of individuals under 10 years old and < 5% under 20 years old, concurrence was 12% in people older than 70 years old[97]. The authors concluded that DVA-CM lesions have a de novo formation basis rather than congenital, and age-related changes in the venous network could trigger the development of a CM in the vicinity of a DVA[97]. In a large MRI observational study of 1839 Chinese patients with DVAs, there was an association with CM in 205 of them (11.1%)[96]. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the DVA-CM concurrence in the four age groups studied (< 20, 20-39, 40-59, > 60 years old)[96].

In a retrospective review of 112 patients with CM, 81 were familial, and 18 were sporadic[105]. A DVA was associated with 44% of the sporadic CM cases (8/18) but only in 1/81 patients with familial-based CM[105]. Petersen et al[105] justified the lower percentage of DVA-CM prevalence in other studies by the mixed population, i.e., sporadic and familial. Moreover, the authors suggested a different pathogenetic mechanism for the sporadic CMs, linking their formation with a pre-existing DVA[105]. Zhang et al[102] observed multiple CMs in 16.7% of cases of cerebellar CMs without DVA present (5/30 cases) and in no case of cerebellar DVA-CM concurrence (0/11 cases), further supporting a different development mechanism for familial and sporadic cases of CMs, since multiplicity of CMs is related to a familial origin of them.

A symptomatic hemorrhagic event is the most common severe clinical manifestation of a DVA-CM concurrence in the CNS. Although not statistically significant due to the study’s small series, Abdulrauf et al[100] observed symptomatic hemorrhage in 62% of DVA-CM cases and 38% of cases with CM alone. Repeat symptomatic hemorrhage was also higher in the DVA-CM group than in the CM-only group: 23% vs 9.5%; 15% of DVA-CM cases were associated with focal neurological deficits, and another 15% were found during headache work-up or incidentally[100]. A higher annual hemorrhagic rate for DVA-CM cases was also observed by Porter et al[98] when compared with CM-only patients: 3.4% vs 0.4%. In their research with both supra- and infratentorial DVAs published the same year, Töpper et al[95] noticed that in all cases with symptomatic hemorrhage, a CM was in the vicinity of the DVA (5/5 cases).

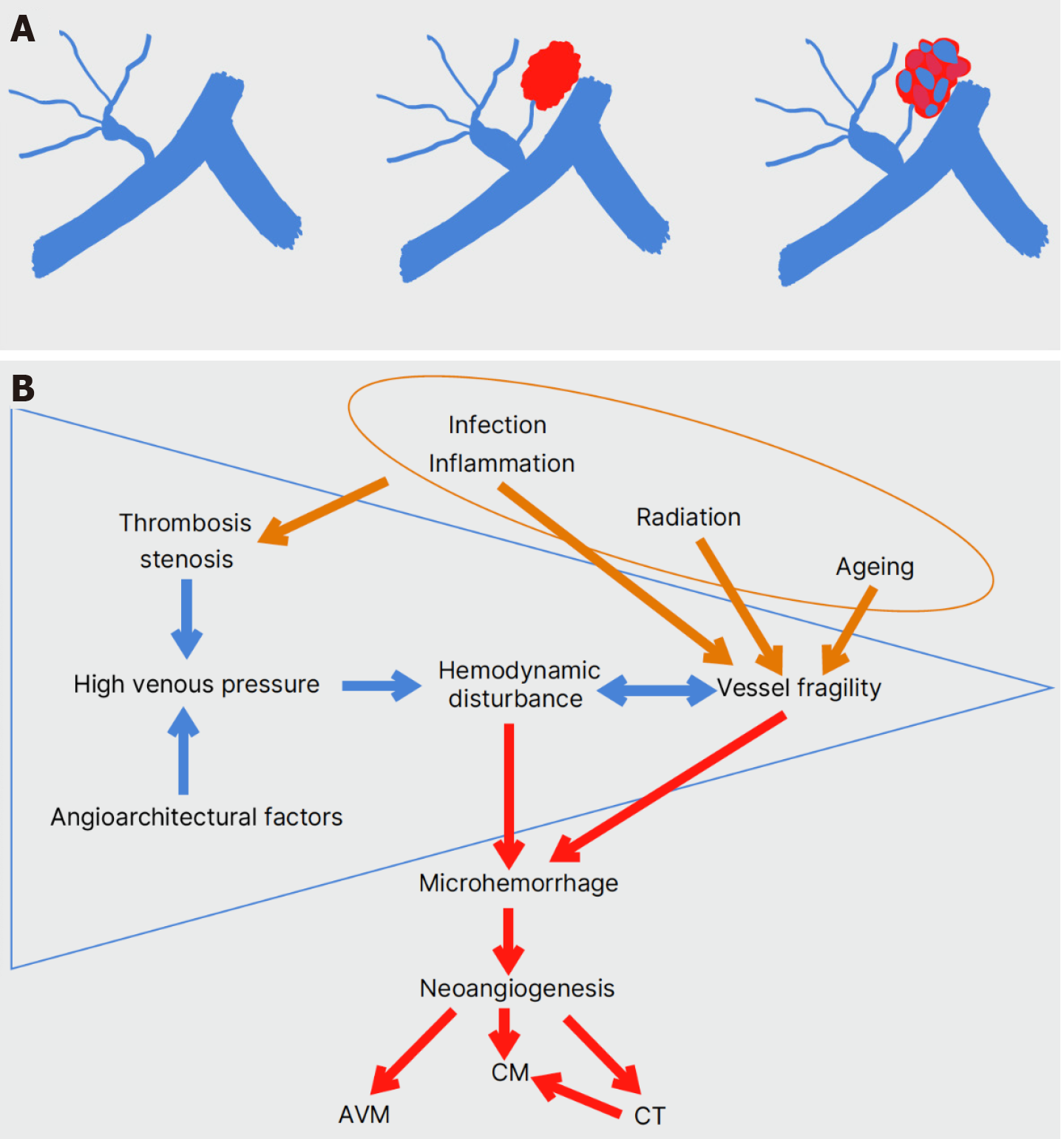

Over the last decades, the clinical impact of a hemorrhagic event by DVA-CM malformations has urged many researchers to explore their pathophysiological basis. Despite the classical McCormick classification of VMs into four main types (DVA, CM, arteriovenous malformation, and capillary telangiectasias), histopathology analyses reveal a continuum among the different subtypes with mixed malformations in all possible combinations[103,106,107]. CM-DVA coexistence is considered the most common mixed VM[95].

Since the 1990s, the mechanism of “hemorrhagic angiogenic proliferation” has been suggested[108]. Venous and capillary malformations cause microhemorrhage due to hemodynamic disturbance or vessel fragility, which in turn leads to reactive angiogenesis and the formation of CMs[108]. The expression of angiogenic factors has been verified in all types of CNS VMs[109]. In 1998, two studies on radiation therapy’s effect on CM development were published. Larson et al[110] noticed the formation of a CM in the irradiated brain field of 6 children with a CNS neoplasm. Histopathology of the resected lesions showed features of both CMs and CTs[110]. The radiation effect on the cerebral microcirculation could induce the formation of CTs and their evolution into CMs[110]. In the case of a 3-year-old boy with medulloblastoma, Maeder et al[111] observed a small hemorrhagic lesion close to a known DVA 3 years after irradiation of the neoplasm. Two years later, the lesion acquired imaging and histopathologic features of a CM[111]. Stenosis of the deep collector vein of the DVA, shown on T1w MR images, and the probable high venous pressure were held responsible for the CM formation[111]. Dillon et al[112] had already reported intraoperative high venous pressure within a DVA associated with recurrent cerebral hemorrhages. Obstruction of venous outflow was shown on CT angiography[112]. Radiation-induced CM formation supports the concept of “hemorrhagic angiogenic proliferation” proposed by Awad et al[108].

The concept of a DVA contributing to hemorrhage risk in an associated CM was further supported by Porter et al[104]. As previously noted, in their retrospective review of hemorrhagic brainstem CM resection in 86 patients, a DVA was found intraoperatively in all 86 of them[104]. Moreover, in 2 patients with relapse, post-operative MR imaging was clear for CM lesions, but DVAs were present[104]. Two case reports, in 2003 and 2005, described the de novo development of a CM adjacent to a pre-existing DVA without any apparent triggering factor, such as radiation. Cakirer reported the evolvement of a well-circumscribed cerebral hematoma close to a pre-existing DVA into a DVA-CM mixed malformation within 1 year[113]. The CM was verified histologically, but no DVA stenosis was revealed on angiography[113]. In the case report by Campeau et al[114], a cerebellar CM was formed in the vicinity of a pre-existing DVA in a patient with relapsing headache and dizziness.

Therefore, an important question arises: Could the abnormal draining vein of the DVA, which may be shared by or lie adjacent to the CM, be the main factor in inducing CM development? The frequency of DVA-CM malformations may have been underestimated in the literature. Many small venous anomalies become visible only intraoperatively and after the CM is resected[101]. Sasaki et al[115] noticed intraoperatively that small veins from a CM drained to the central, dilated medullary vein of the DVA. Wilson et al[116] proposed three possible causes of raised venous pressure in a venous malformation or its distal radicles: (1) Thrombosis; (2) Acute increase in intracranial pressure; and (3) Outflow restriction of the vein while entering the central vein or venous sinus.

Interestingly, in 3 DVA-CM relapses where the CM had been resected, and the large draining vein of the DVA had been left untouched, histology of the relapses revealed arteriovenous angiomas or CTs, not CMs[101]. These results supported the CNS VM continuum theory, suggesting that a DVA is the primary lesion and the other three VMs arise because of its dysfunctional venous drainage[101,103]. The next step was to try to comprehend the hemodynamic behavior and angioarchitectural structure of the DVA-CM lesions by zooming in. In 22/23 DVA-CM lesions, Hong et al[117] measured acute angulation (< 90°) of the distal medullary or draining vein. The CM was also found adjacent to the angulated draining vein in 22/23 of the mixed lesions[117]. The authors suggested that the turbulent flow caused mainly by these two angioarchitectural factors may lead to vessel injury, microhemorrhage, and neoangiogenesis[117].

In a multivariate analysis of 76 DVA-CM cases vs 503 DVA-only cases, six angioarchitectural factors were associated with DVA-CM concurrence: (1) Infratentorial location of the DVA; (2) Deep direction of the terminal or draining vein to which the caput medusae joins; (3) Torsion of the draining vein; (4) Presence of ≥ 5 medullary veins; (5) ≥ 54.68% stenosis rate of the medullary veins; and (6) Angle ≤ 10650 of the draining vein[118].

According to Shama et al[60], a local increase in venous pressure due to restricted venous drainage could also contribute to microhemorrhage and CM formation. In their prospective perfusion MRI study, 10 DVA-CM cases showed a greater prolongation of MTT and a lesser increase or even decrease of rCBF compared to 15 DVA-only cases[60]. Inte

The authors provided three probable mechanisms: (1) DVA thrombosis due to inflammation; (2) Angiogenesis induced by inflammation-enhanced vascular permeability; and (3) Implication of the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)[119]. Gram-negative bacteria activate TLR4 and increase CM formation in mice[120]. Additionally, polymorphisms that increase TLR4 expression levels have been linked with a higher number of CMs in humans[120]. Overall, the main patho

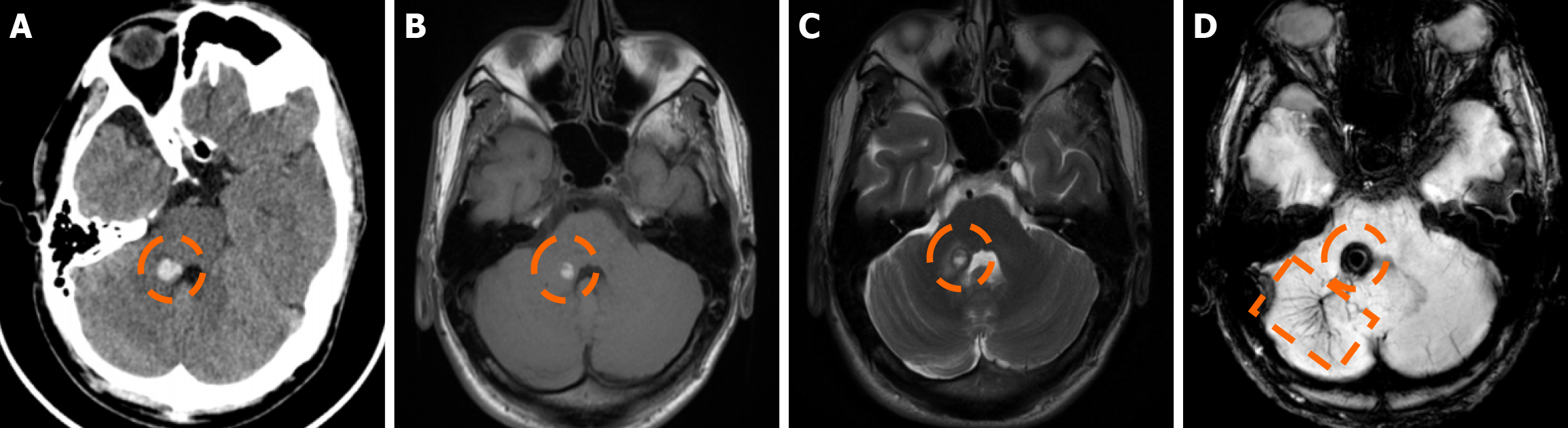

Imaging findings in coexistent DVAs and CMs will be the combination of those described for each malformation separately. Awareness of the possibility of their coexistence may prove invaluable in clinical practice. This is because recognition of a DVA close to a brain hemorrhage may raise suspicion for an underlying CM as the most likely etiology. Additional examinations and follow-up imaging following hematoma resolution will further enhance diagnostic confidence. Figures 8, 9, 10 and 11 illustrate clinical examples in which identifying the synchronous presence of a DVA adjacent to a brain hemorrhage (or suspected brain hemorrhage) enabled the diagnosis of a probable underlying CM as the most likely etiology, thereby avoiding unnecessary examinations or interventions.

Most of the debate on the management and treatment of mixed DVA-CM malformations has focused on two issues: Leave the DVA untouched while resecting a CM, or not? Does the presence of a DVA next to a CM increase its hemor

Association of a DVA with a CM has long been considered a risk factor for a more aggressive clinical course than a CM-only lesion[100,101,108]. In their retrospective multivariable analysis of 154 CM cases, Kashefiolasl et al[122] associated the age > 45 years old, the infratentorial location of the CM, and the presence of a DVA with a higher hemorrhagic risk. However, in a large single-center observational study with 731 non-familial, non-spinal DVA-CM cases, the presence of a DVA close to a CM was associated with a lower risk of presenting with intracerebral hemorrhage and equal risk of (re)-hemorrhage with CM-only cases[123]. The size of the hemorrhage did not relate to the presence of a DVA either[123]. Initial presentation with intracerebral hemorrhage and brainstem location of the mixed malformation were the only independent risk factors for (re)-hemorrhage[123]. These results seriously impact clinical counseling by questioning the argument that the presence of a DVA close to a CM constitutes an indication to resect the CM[123,124].

Cerebral VMs represent a heterogeneous group of entities with distinct pathophysiological mechanisms, imaging characteristics, and clinical implications. DVAs and CMs are the most common venous malformations, and when they coexist, the DVA’s altered venous pressure and flow can promote CM formation or rupture, causing a symptomatic hemorrhagic event, which is the most common severe clinical manifestation of a DVA-CM concurrence. Thus, detecting a DVA adjacent to an otherwise unexplained intracerebral hemorrhage may be the clue to an important diagnosis, as it can raise suspicion of an occult CM as the underlying etiology of the bleed. Recognizing the hallmark imaging appearances of DVAs and CMs, along with the sometimes subtle signs of their coexistence, can be invaluable for achieving an accurate and timely diagnosis, ensuring appropriately targeted management, and avoiding unnecessary interventions.

| 1. | Vollherbst DF, Bendszus M, Möhlenbruch MA. Vascular Malformations of the Brain and Its Coverings. J Neuroendovasc Ther. 2020;14:285-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lasjaunias P, Burrows P, Planet C. Developmental venous anomalies (DVA): the so-called venous angioma. Neurosurg Rev. 1986;9:233-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | San Millán Ruíz D, Gailloud P. Cerebral developmental venous anomalies. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26:1395-1406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mooney MA, Zabramski JM. Developmental venous anomalies. Handb Clin Neurol. 2017;143:279-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ruíz DS, Yilmaz H, Gailloud P. Cerebral developmental venous anomalies: current concepts. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:271-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rammos SK, Maina R, Lanzino G. Developmental venous anomalies: current concepts and implications for management. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:20-9; discussion 29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gökçe E, Acu B, Beyhan M, Celikyay F, Celikyay R. Magnetic resonance imaging findings of developmental venous anomalies. Clin Neuroradiol. 2014;24:135-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Brzegowy K, Kowalska N, Solewski B, Musiał A, Kasprzycki T, Herman-Sucharska I, Walocha JA. Prevalence and anatomical characteristics of developmental venous anomalies: an MRI study. Neuroradiology. 2021;63:1001-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Senegor M, Dohrmann GJ, Wollmann RL. Venous angiomas of the posterior fossa should be considered as anomalous venous drainage. Surg Neurol. 1983;19:26-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | San Millán Ruíz D, Delavelle J, Yilmaz H, Gailloud P, Piovan E, Bertramello A, Pizzini F, Rüfenacht DA. Parenchymal abnormalities associated with developmental venous anomalies. Neuroradiology. 2007;49:987-995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Linscott LL, Leach JL, Zhang B, Jones BV. Brain parenchymal signal abnormalities associated with developmental venous anomalies in children and young adults. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:1600-1607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee C, Pennington MA, Kenney CM 3rd. MR evaluation of developmental venous anomalies: medullary venous anatomy of venous angiomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:61-70. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Saito Y, Kobayashi N. Cerebral venous angiomas: clinical evaluation and possible etiology. Radiology. 1981;139:87-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Aoki R, Srivatanakul K. Developmental Venous Anomaly: Benign or Not Benign. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2016;56:534-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Brinjikji W, El-Rida El-Masri A, Wald JT, Lanzino G. Prevalence of Developmental Venous Anomalies Increases With Age. Stroke. 2017;48:1997-1999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Horsch S, Govaert P, Cowan FM, Benders MJ, Groenendaal F, Lequin MH, Saliou G, de Vries LS. Developmental venous anomaly in the newborn brain. Neuroradiology. 2014;56:579-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Geraldo AF, Messina SS, Tortora D, Parodi A, Malova M, Morana G, Gandolfo C, D'Amico A, Herkert E, Govaert P, Ramenghi LA, Rossi A, Severino M. Neonatal Developmental Venous Anomalies: Clinicoradiologic Characterization and Follow-Up. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020;41:2370-2376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rinaldo L, Lanzino G, Flemming KD, Krings T, Brinjikji W. Symptomatic developmental venous anomalies. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2020;162:1115-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pereira VM, Geibprasert S, Krings T, Aurboonyawat T, Ozanne A, Toulgoat F, Pongpech S, Lasjaunias PL. Pathomechanisms of symptomatic developmental venous anomalies. Stroke. 2008;39:3201-3215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Amuluru K, Al-Mufti F, Hannaford S, Singh IP, Prestigiacomo CJ, Gandhi CD. Symptomatic Infratentorial Thrombosed Developmental Venous Anomaly: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Interv Neurol. 2016;4:130-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kiroglu Y, Oran I, Dalbasti T, Karabulut N, Calli C. Thrombosis of a drainage vein in developmental venous anomaly (DVA) leading venous infarction: a case report and review of the literature. J Neuroimaging. 2011;21:197-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Agarwal N, Zuccoli G, Murdoch G, Jankowitz BT, Greene S. Developmental venous anomaly presenting as a spontaneous intraparenchymal hematoma without thrombosis. Neuroradiol J. 2016;29:465-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hon JM, Bhattacharya JJ, Counsell CE, Papanastassiou V, Ritchie V, Roberts RC, Sellar RJ, Warlow CP, Al-Shahi Salman R; SIVMS Collaborators. The presentation and clinical course of intracranial developmental venous anomalies in adults: a systematic review and prospective, population-based study. Stroke. 2009;40:1980-1985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Garner TB, Del Curling O Jr, Kelly DL Jr, Laster DW. The natural history of intracranial venous angiomas. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:715-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dussaule C, Masnou P, Nasser G, Archambaud F, Cauquil-Michon C, Gagnepain JP, Bouilleret V, Denier C. Can developmental venous anomalies cause seizures? J Neurol. 2017;264:2495-2505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hsu CC, Krings T. Symptomatic Developmental Venous Anomaly: State-of-the-Art Review on Genetics, Pathophysiology, and Imaging Approach to Diagnosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2023;44:498-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Samadian M, Bakhtevari MH, Nosari MA, Babadi AJ, Razaei O. Trigeminal Neuralgia Caused by Venous Angioma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2015;84:860-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Pelz DM, Vinuela F, Fox AJ. Unusual radiologic and clinical presentations of posterior fossa venous angiomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1983;4:81-84. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Ogul H, Unlu EN, Guclu D, Koksal A. Cerebellar Developmental Venous Anomaly Causing Tinnitus and Hemifacial Spasm: A Case Report. Ear Nose Throat J. 2025;104:553-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Grigoryan G, Sitnikov A, Grigoryan Y. Hemifacial spasm caused by the brainstem developmental venous anomaly: A case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2020;11:141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Uchino A, Sawada A, Takase Y, Abe M, Kudo S. Cerebral hemiatrophy caused by multiple developmental venous anomalies involving nearly the entire cerebral hemisphere. Clin Imaging. 2001;25:82-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sarp AF, Batki O, Gelal MF. Developmental Venous Anomaly With Asymmetrical Basal Ganglia Calcification: Two Case Reports and Review of the Literature. Iran J Radiol. 2015;12:e16753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Manjila S, Bazil T, Thomas M, Mani S, Kay M, Udayasankar U. A review of extraaxial developmental venous anomalies of the brain involving dural venous flow or sinuses: persistent embryonic sinuses, sinus pericranii, venous varices or aneurysmal malformations, and enlarged emissary veins. Neurosurg Focus. 2018;45:E9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Nomura S, Kato S, Ishihara H, Yoneda H, Ideguchi M, Suzuki M. Association of intra- and extradural developmental venous anomalies, so-called venous angioma and sinus pericranii. Childs Nerv Syst. 2006;22:428-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Boukobza M, Enjolras O, Guichard JP, Gelbert F, Herbreteau D, Reizine D, Merland JJ. Cerebral developmental venous anomalies associated with head and neck venous malformations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:987-994. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Brinjikji W, Hilditch CA, Tsang AC, Nicholson PJ, Krings T, Agid R. Facial Venous Malformations Are Associated with Cerebral Developmental Venous Anomalies. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39:2103-2107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Brinjikji W, Nicholson P, Hilditch CA, Krings T, Pereira V, Agid R. Cerebrofacial venous metameric syndrome-spectrum of imaging findings. Neuroradiology. 2020;62:417-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Bisdorff A, Mulliken JB, Carrico J, Robertson RL, Burrows PE. Intracranial vascular anomalies in patients with periorbital lymphatic and lymphaticovenous malformations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:335-41. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Ballieux F, Boon LM, Vikkula M. Blue bleb rubber nevus syndrome. Handb Clin Neurol. 2015;132:223-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Chhabda S, Sudhakar S, Mankad K, Jorgensen M, Carceller F, Jacques TS, Merve A, Aizpurua M, Chalker J, Garimberti E, D'Arco F. Constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (CMMRD) presenting with high-grade glioma, multiple developmental venous anomalies and malformations of cortical development-a multidisciplinary/multicentre approach and neuroimaging clues to clinching the diagnosis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2021;37:2375-2379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Dhamija R, Weindling SM, Porter AB, Hu LS, Wood CP, Hoxworth JM. Neuroimaging abnormalities in patients with Cowden syndrome: Retrospective single-center study. Neurol Clin Pract. 2018;8:207-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | McLean A, Alalade AF, Golash A, Gurusinghe N. De Novo Cavernoma Formation in a Patient With Cowden Syndrome and Lhermitte-Duclos Disease. World Neurosurg. 2020;143:308-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Jung G, Schröder R, Lanfermann H, Jacobs A, Szelies B, Schröder R. Evidence of acute demyelination around a developmental venous anomaly: magnetic resonance imaging findings. Invest Radiol. 1997;32:575-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 44. | Rogers DM, Peckham ME, Shah LM, Wiggins RH 3rd. Association of Developmental Venous Anomalies with Demyelinating Lesions in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39:97-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Nabavizadeh SA, Mamourian AC, Vossough A, Loevner LA, Hurst R. The Many Faces of Cerebral Developmental Venous Anomaly and Its Mimicks: Spectrum of Imaging Findings. J Neuroimaging. 2016;26:463-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Iv M, Fischbein NJ, Zaharchuk G. Association of developmental venous anomalies with perfusion abnormalities on arterial spin labeling and bolus perfusion-weighted imaging. J Neuroimaging. 2015;25:243-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Hanson EH, Roach CJ, Ringdahl EN, Wynn BL, DeChancie SM, Mann ND, Diamond AS, Orrison WW Jr. Developmental venous anomalies: appearance on whole-brain CT digital subtraction angiography and CT perfusion. Neuroradiology. 2011;53:331-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Dehkharghani S, Dillon WP, Bryant SO, Fischbein NJ. Unilateral calcification of the caudate and putamen: association with underlying developmental venous anomaly. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:1848-1852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Saba PR. The caput medusae sign. Radiology. 1998;207:599-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Huber G, Henkes H, Hermes M, Felber S, Terstegge K, Piepgras U. Regional association of developmental venous anomalies with angiographically occult vascular malformations. Eur Radiol. 1996;6:30-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Linscott LL, Leach JL, Jones BV, Abruzzo TA. Developmental venous anomalies of the brain in children -- imaging spectrum and update. Pediatr Radiol. 2016;46:394-406; quiz 391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | de Souza JM, Domingues RC, Cruz LC Jr, Domingues FS, Iasbeck T, Gasparetto EL. Susceptibility-weighted imaging for the evaluation of patients with familial cerebral cavernous malformations: a comparison with t2-weighted fast spin-echo and gradient-echo sequences. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:154-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Tsui YK, Tsai FY, Hasso AN, Greensite F, Nguyen BV. Susceptibility-weighted imaging for differential diagnosis of cerebral vascular pathology: a pictorial review. J Neurol Sci. 2009;287:7-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Dammann P, Barth M, Zhu Y, Maderwald S, Schlamann M, Ladd ME, Sure U. Susceptibility weighted magnetic resonance imaging of cerebral cavernous malformations: prospects, drawbacks, and first experience at ultra-high field strength (7-Tesla) magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;29:E5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Santucci GM, Leach JL, Ying J, Leach SD, Tomsick TA. Brain parenchymal signal abnormalities associated with developmental venous anomalies: detailed MR imaging assessment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1317-1323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Jung HN, Kim ST, Cha J, Kim HJ, Byun HS, Jeon P, Kim KH, Kim BJ, Kim HJ. Diffusion and perfusion MRI findings of the signal-intensity abnormalities of brain associated with developmental venous anomaly. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:1539-1542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Takasugi M, Fujii S, Shinohara Y, Kaminou T, Watanabe T, Ogawa T. Parenchymal hypointense foci associated with developmental venous anomalies: evaluation by phase-sensitive MR Imaging at 3T. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:1940-1944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Sundermann B, Pfleiderer B, Minnerup H, Berger K, Douaud G. Interaction of Developmental Venous Anomalies with Resting-State Functional MRI Measures. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39:2326-2331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Camacho DL, Smith JK, Grimme JD, Keyserling HF, Castillo M. Atypical MR imaging perfusion in developmental venous anomalies. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:1549-1552. [PubMed] |

| 60. | Sharma A, Zipfel GJ, Hildebolt C, Derdeyn CP. Hemodynamic effects of developmental venous anomalies with and without cavernous malformations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:1746-1751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Speck O, Chang L, DeSilva NM, Ernst T. Perfusion MRI of the human brain with dynamic susceptibility contrast: gradient-echo versus spin-echo techniques. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;12:381-387. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 62. | Larvie M, Timerman D, Thum JA. Brain metabolic abnormalities associated with developmental venous anomalies. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36:475-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Griffiths D, Newey A, Faulder K, Steinfort B, Krause M. Thrombosis of a developmental venous anomaly causing venous infarction and pontine hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:e653-e655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Merten CL, Knitelius HO, Hedde JP, Assheuer J, Bewermeyer H. Intracerebral haemorrhage from a venous angioma following thrombosis of a draining vein. Neuroradiology. 1998;40:15-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Peltier J, Toussaint P, Desenclos C, Le Gars D, Deramond H. Cerebral venous angioma of the pons complicated by nonhemorrhagic infarction. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:690-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Yanaka K, Hyodo A, Nose T. Venous malformation serving as the draining vein of an adjoining arteriovenous malformation. Case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2001;56:170-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 67. | Fok KF, Holmin S, Alvarez H, Ozanne A, Krings T, Lasjaunias PL. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage caused by an unusual association of developmental venous anomaly and arteriovenous malformation. Interv Neuroradiol. 2006;12:113-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Oran I, Kiroglu Y, Yurt A, Ozer FD, Acar F, Dalbasti T, Yagci B, Sirikci A, Calli C. Developmental venous anomaly (DVA) with arterial component: a rare cause of intracranial haemorrhage. Neuroradiology. 2009;51:25-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Kurita H, Sasaki T, Tago M, Kaneko Y, Kirino T. Successful radiosurgical treatment of arteriovenous malformation accompanied by venous malformation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:482-485. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Meyer B, Stangl AP, Schramm J. Association of venous and true arteriovenous malformation: a rare entity among mixed vascular malformations of the brain. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:141-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Smith ER. Cavernous Malformations of the Central Nervous System. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:1022-1028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 72. | Washington CW, McCoy KE, Zipfel GJ. Update on the natural history of cavernous malformations and factors predicting aggressive clinical presentation. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;29:E7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | da Cruz LCH, Pires CE. Miscellaneous Vascular Malformations (Cavernous Malformations, Developmental Venous Anomaly, Capillary Telangiectasia, Sinus Pericranii). In: Saba L, Raz E, editors. Neurovasc Imaging. New York, NY: Springer, 2016: 719-749. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 74. | Rigamonti D. Clinical features, imaging and diagnostic work-up. In: Cavernous Malformations of the Nervous System. Cambridge University Press, 2011: 49-102. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 75. | Rigamonti D, Johnson PC, Spetzler RF, Hadley MN, Drayer BP. Cavernous malformations and capillary telangiectasia: a spectrum within a single pathological entity. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:60-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Dulamea AO, Lupescu IC. Cerebral cavernous malformations - An overview on genetics, clinical aspects and therapeutic strategies. J Neurol Sci. 2024;461:123044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Gross BA, Du R. Hemorrhage from cerebral cavernous malformations: a systematic pooled analysis. J Neurosurg. 2017;126:1079-1087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Gault J, Sarin H, Awadallah NA, Shenkar R, Awad IA. Pathobiology of human cerebrovascular malformations: basic mechanisms and clinical relevance. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:1-16; discussion 16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Cortés Vela JJ, Concepción Aramendía L, Ballenilla Marco F, Gallego León JI, González-Spínola San Gil J. Cerebral cavernous malformations: spectrum of neuroradiological findings. Radiologia. 2012;54:401-9.. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Wang KY, Idowu OR, Lin DDM. Radiology and imaging for cavernous malformations. Handb Clin Neurol. 2017;143:249-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Akers A, Al-Shahi Salman R, A Awad I, Dahlem K, Flemming K, Hart B, Kim H, Jusue-Torres I, Kondziolka D, Lee C, Morrison L, Rigamonti D, Rebeiz T, Tournier-Lasserve E, Waggoner D, Whitehead K. Synopsis of Guidelines for the Clinical Management of Cerebral Cavernous Malformations: Consensus Recommendations Based on Systematic Literature Review by the Angioma Alliance Scientific Advisory Board Clinical Experts Panel. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:665-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 40.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Bulut HT, Sarica MA, Baykan AH. The value of susceptibility weighted magnetic resonance imaging in evaluation of patients with familial cerebral cavernous angioma. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:5296-5302. [PubMed] |

| 83. | Cooper AD, Campeau NG, Meissner I. Susceptibility-weighted imaging in familial cerebral cavernous malformations. Neurology. 2008;71:382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Campbell PG, Jabbour P, Yadla S, Awad IA. Emerging clinical imaging techniques for cerebral cavernous malformations: a systematic review. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;29:E6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Pinker K, Stavrou I, Szomolanyi P, Hoeftberger R, Weber M, Stadlbauer A, Noebauer-Huhmann IM, Knosp E, Trattnig S. Improved preoperative evaluation of cerebral cavernomas by high-field, high-resolution susceptibility-weighted magnetic resonance imaging at 3 Tesla: comparison with standard (1.5 T) magnetic resonance imaging and correlation with histopathological findings--preliminary results. Invest Radiol. 2007;42:346-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Schlamann M, Maderwald S, Becker W, Kraff O, Theysohn JM, Mueller O, Sure U, Wanke I, Ladd ME, Forsting M, Schaefer L, Gizewski ER. Cerebral cavernous hemangiomas at 7 Tesla: initial experience. Acad Radiol. 2010;17:3-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Zabramski JM, Wascher TM, Spetzler RF, Johnson B, Golfinos J, Drayer BP, Brown B, Rigamonti D, Brown G. The natural history of familial cavernous malformations: results of an ongoing study. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:422-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 679] [Cited by in RCA: 610] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 88. | Saari E, Koivisto T, Rauramaa T, Frösen J. Clinical and radiological presentation of cavernomas according to the Zabramski classification. J Neurosurg. 2025;142:1751-1762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Wang J, Yu QF, Huo R, Sun YF, Jiao YM, Xu HY, Zhang JZ, Zhao SZ, He QH, Wang S, Zhao JZ, Cao Y. Zabramski classification in predicting the occurrence of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage in sporadic cerebral cavernous malformations. J Neurosurg. 2024;140:792-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Nikoubashman O, Di Rocco F, Davagnanam I, Mankad K, Zerah M, Wiesmann M. Prospective Hemorrhage Rates of Cerebral Cavernous Malformations in Children and Adolescents Based on MRI Appearance. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36:2177-2183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Batra S, Lin D, Recinos PF, Zhang J, Rigamonti D. Cavernous malformations: natural history, diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5:659-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Yun TJ, Na DG, Kwon BJ, Rho HG, Park SH, Suh YL, Chang KH. A T1 hyperintense perilesional signal aids in the differentiation of a cavernous angioma from other hemorrhagic masses. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:494-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Ostertun B, Solymosi L. Magnetic resonance angiography of cerebral developmental venous anomalies: its role in differential diagnosis. Neuroradiology. 1993;35:97-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Wilms G, Bleus E, Demaerel P, Marchal G, Plets C, Goffin J, Baert AL. Simultaneous occurrence of developmental venous anomalies and cavernous angiomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:1247-54. [PubMed] |

| 95. | Töpper R, Jürgens E, Reul J, Thron A. Clinical significance of intracranial developmental venous anomalies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67:234-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Meng G, Bai C, Yu T, Wu Z, Liu X, Zhang J, zhao J. The association between cerebral developmental venous anomaly and concomitant cavernous malformation: an observational study using magnetic resonance imaging. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Brinjikji W, El-Masri AE, Wald JT, Flemming KD, Lanzino G. Prevalence of cerebral cavernous malformations associated with developmental venous anomalies increases with age. Childs Nerv Syst. 2017;33:1539-1543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Porter PJ, Willinsky RA, Harper W, Wallace MC. Cerebral cavernous malformations: natural history and prognosis after clinical deterioration with or without hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:190-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 372] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Abe T, Singer RJ, Marks MP, Norbash AM, Crowley RS, Steinberg GK. Coexistence of occult vascular malformations and developmental venous anomalies in the central nervous system: MR evaluation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:51-57. [PubMed] |

| 100. | Abdulrauf SI, Kaynar MY, Awad IA. A comparison of the clinical profile of cavernous malformations with and without associated venous malformations. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:41-6; discussion 46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Wurm G, Schnizer M, Fellner FA. Cerebral cavernous malformations associated with venous anomalies: surgical considerations. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:42-58; discussion 42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Zhang P, Liu L, Cao Y, Wang S, Zhao J. Cerebellar cavernous malformations with and without associated developmental venous anomalies. BMC Neurol. 2013;13:134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Perrini P, Lanzino G. The association of venous developmental anomalies and cavernous malformations: pathophysiological, diagnostic, and surgical considerations. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;21:e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |