Published online Dec 28, 2025. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v17.i12.115388

Revised: October 22, 2025

Accepted: December 3, 2025

Published online: December 28, 2025

Processing time: 71 Days and 22.6 Hours

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly being explored in radiology, including its potential role in emergency imaging settings. However, global perspectives on AI adoption, usefulness, and limitations among emergency radiologists remain underexplored.

To assess awareness, usage, perceived benefits, and limitations of AI tools among radiologists practicing emergency radiology worldwide.

A 16-question survey was distributed globally between October 24, 2024, and August 4, 2025, targeting radiologists working in academic, community, and private settings who practice emergency radiology as a primary or secondary subspecialty. The survey was disseminated via direct emails extracted using automated and manual methods from recent publications in major radiology journals. A total of 57 responses were collected.

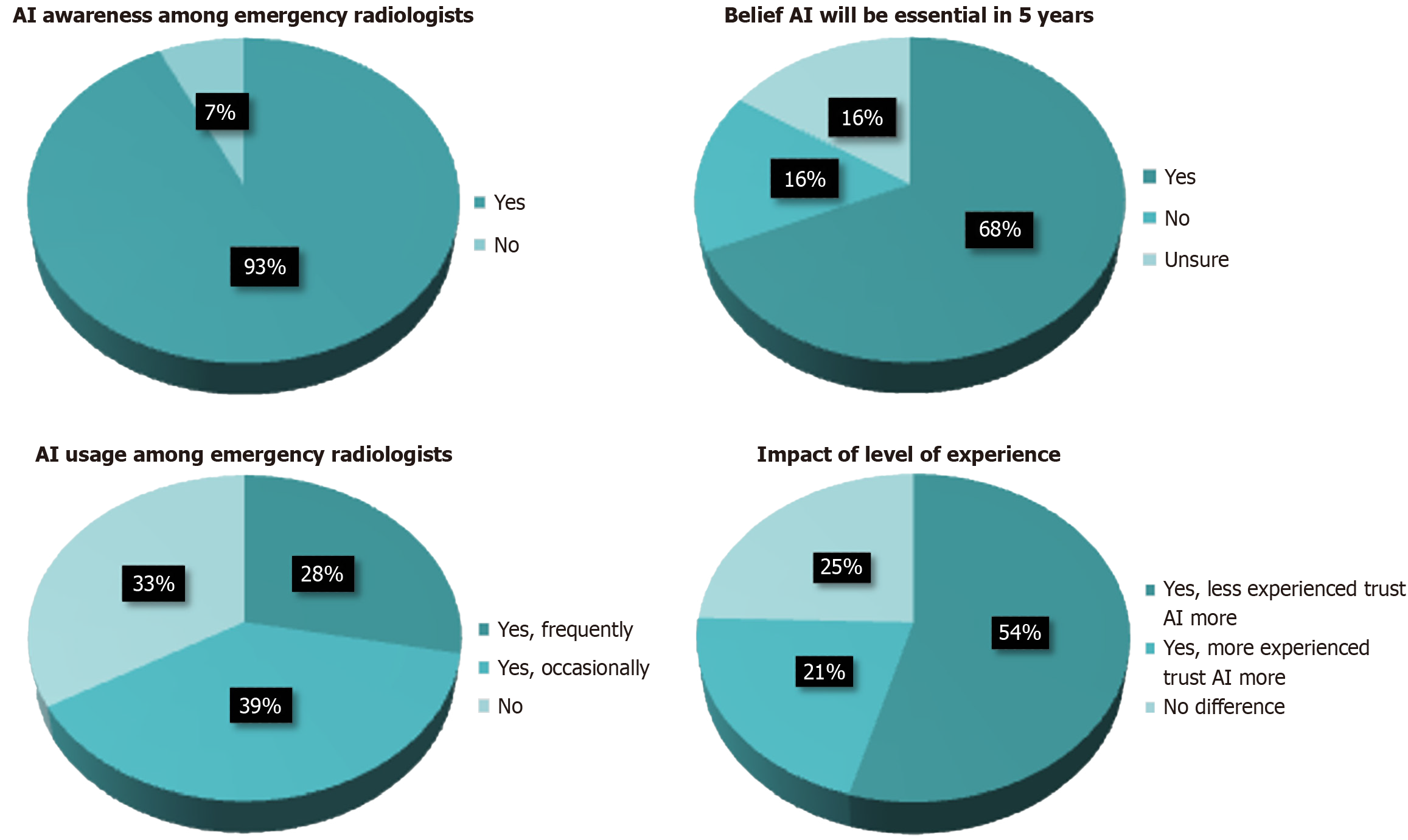

AI awareness was high (93%), but frequent clinical use was reported by only 28%. Daily use of AI in emergent imaging was limited to 23% of respondents. The majority anticipated AI becoming essential within five years (68%), and 51% believed AI would replace certain radiological tasks. Image interpretation and acquisition were the most common AI applications. Key perceived benefits included improved diagnostic accuracy and increased efficiency, while concerns included limited accuracy, integration difficulties, and cost. Trust in AI varied by experience, with less experienced radiologists viewed as more trusting.

While emergency radiologists globally recognize AI’s potential, significant barriers to its routine adoption remain. Addressing issues of trust, cost, accuracy, and workflow integration is essential to unlock AI's full utility in emergency radiology.

Core Tip: This study addresses the limited data on how emergency radiologists worldwide perceive, use, and trust artificial intelligence (AI) tools in clinical workflows, highlighting an unmet need for global insight. Surveying 57 emergency radiologists globally, we found high AI awareness (93%) but limited frequent use (28%), with the United States and Italy as leading respondent countries. Understanding emergency radiologists’ attitudes towards AI guides tailored implementation, improving diagnostic accuracy, workflow efficiency, and ultimately patient care in emergency imaging.

- Citation: Centini FR, Fedorov D, Perera Molligoda Arachchige AS. Radiologists’ perspectives on the use of artificial intelligence in emergency radiology: A pilot survey. World J Radiol 2025; 17(12): 115388

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v17/i12/115388.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v17.i12.115388

Artificial intelligence (AI) continues to gain traction in radiology, with applications spanning from image acquisition optimization to automated interpretation. Emergency radiology, with its demand for rapid, accurate, and high-volume image interpretation, represents a promising field for AI integration. Despite this promise, actual implementation in clinical workflows remains uneven[1].

Understanding how emergency radiologists perceive and utilize AI is essential to guiding future development, deployment, and policy. Although several studies have addressed AI in general radiology, data specific to emergency settings and on a global scale are limited. Previous surveys have primarily examined general radiology or national cohorts, often focusing on AI attitudes or ethics without emergency-specific insights[2,3]. Few have evaluated adoption barriers unique to emergency imaging, where time-critical interpretation and high case volumes magnify workflow constraints. This study differentiates itself by targeting emergency radiologists globally to capture cross-regional disparities in AI awareness, usage, and trust. Given unequal access to AI infrastructure across continents, understanding global variability in readiness and resource allocation is essential for equitable implementation. This study aimed to fill this gap by surveying radiologists worldwide to assess their awareness, usage patterns, perceived benefits, concerns, and suggestions for improving AI tools in emergent imaging[4].

A cross-sectional survey study was conducted between October 24, 2024 and August 4, 2025. The survey was designed in Google Forms and consisted of 16 questions, including multiple-choice, Likert-scale, and open-ended formats[5]. The questionnaire underwent pilot testing with five radiologists from different institutions to ensure clarity and content validity. Internal consistency of Likert-scale items was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, yielding a value of 0.84, indicating good reliability.

The target population included radiologists globally who practice emergency radiology either as a primary or secondary subspecialty. Eligibility was confirmed by self-report, requiring respondents to indicate emergency radiology as a declared primary or secondary subspecialty in the survey. Email contacts were gathered using automated Python-based extraction and manual verification from corresponding author sections of recent publications in prominent radiology journals (AJR, Radiology, La Radiologia Medica, European Radiology, JACR, Academic Radiology, Clinical Radiology, Emergency Radiology, Abdominal Radiology, and Japanese Journal of Radiology)[6,7]. Each journal yielded approximately 500 email addresses. Approximately 5000 invitation emails were distributed in total, yielding 57 complete responses, corresponding to an estimated response rate of 1.1%. This low rate aligns with other international radiology surveys and underscores the exploratory, pilot nature of the study.

The survey assessed AI awareness, frequency and context of use, perceived benefits and limitations, and demographic variables such as country, years of experience, and work setting. Data was collected into a Microsoft Excel file and after data curation the same tool was used for the analysis and generation of illustrations. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the responses[8]. Graphs and proportions were generated using Microsoft Excel 2024 (Microsoft 365), employing COUNTIF and pivot-table functions for frequency distributions. No inferential statistical tests were applied, consistent with the pilot design.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional review board approval was waived as the survey collected no identifiable personal data, and participation was voluntary and anonymous. Informed consent was implied upon survey completion.

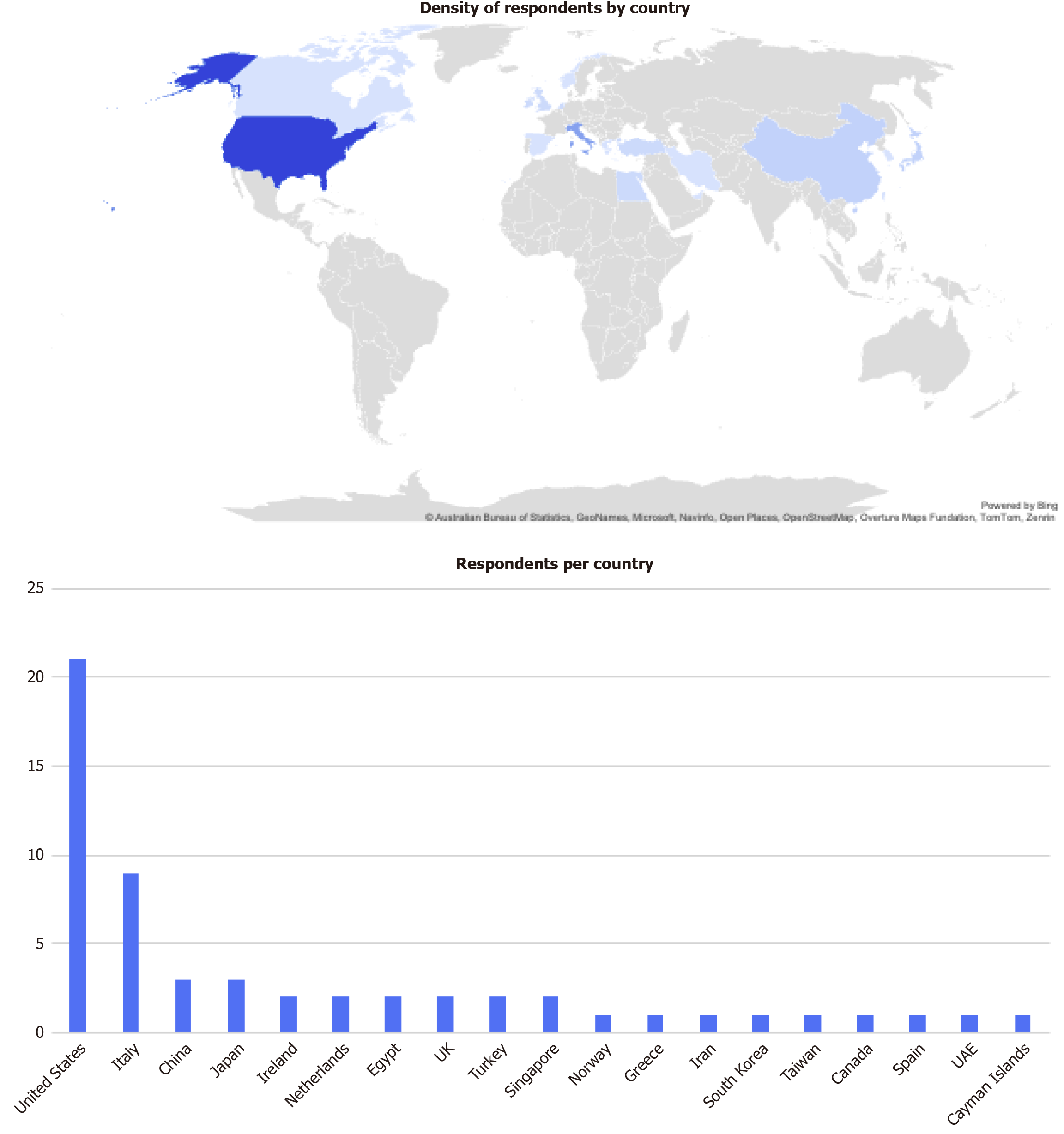

A total of 57 responses were received from radiologists across multiple regions, with the largest groups from the United States (36.84%), Italy (15.78%), China (5.26%), and Japan (5.26%). No responses were received from certain geographical regions such as Australia and South America (Figure 1).

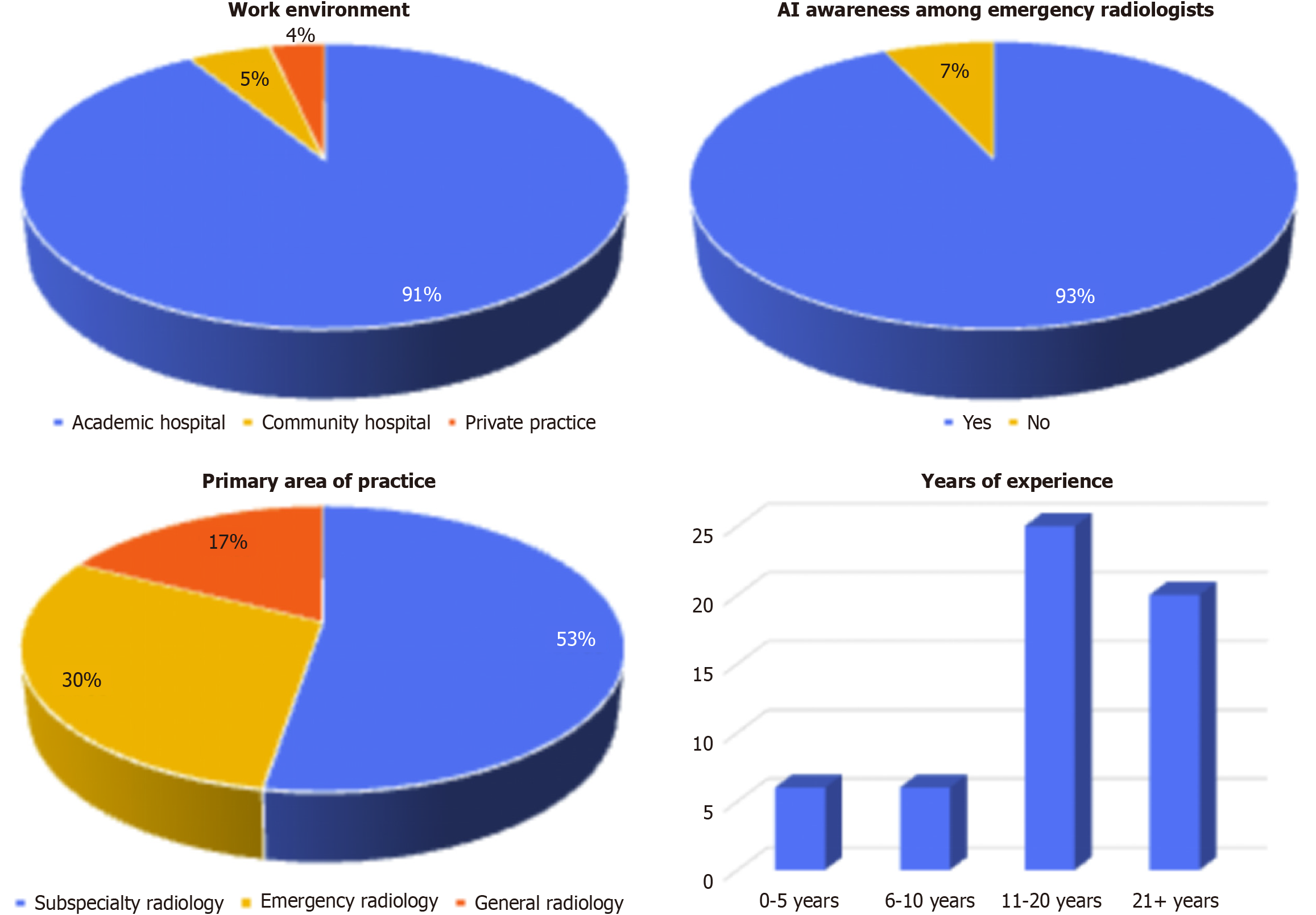

Most respondents worked in academic hospitals (91%), with fewer from community hospitals (5%) and private practices (4%). Subspecialty radiologists primarily practicing in a subspecialty other than emergency radiology made up 53% of the sample, while 30% were primarily emergency radiologists and 17% general radiologists. Awareness of AI tools was high (93%), but frequent use was limited (28%). Regarding experience, 44% had 11-20 years, 35% had over 21 years, and 21% had less than 10 years of experience (Figure 2).

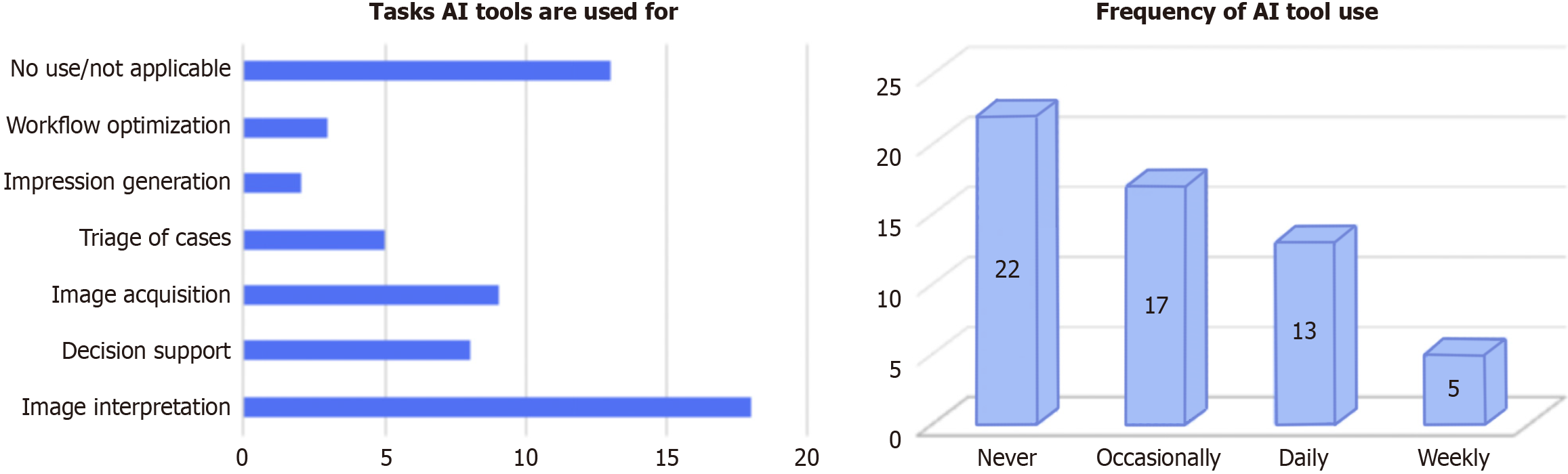

Specifically for emergency imaging, 39% never used AI, 30% used it occasionally, 23% used it daily, and 9% used it weekly. The most common AI uses included image interpretation (n = 18, 32%), image acquisition (n = 9, 16%), and decision support (n = 8, 14%). Case triage (n = 5), workflow optimization (n = 3), and impression generation (n = 2) were less commonly cited. Thirteen respondents (23%) reported no current use (Figure 3).

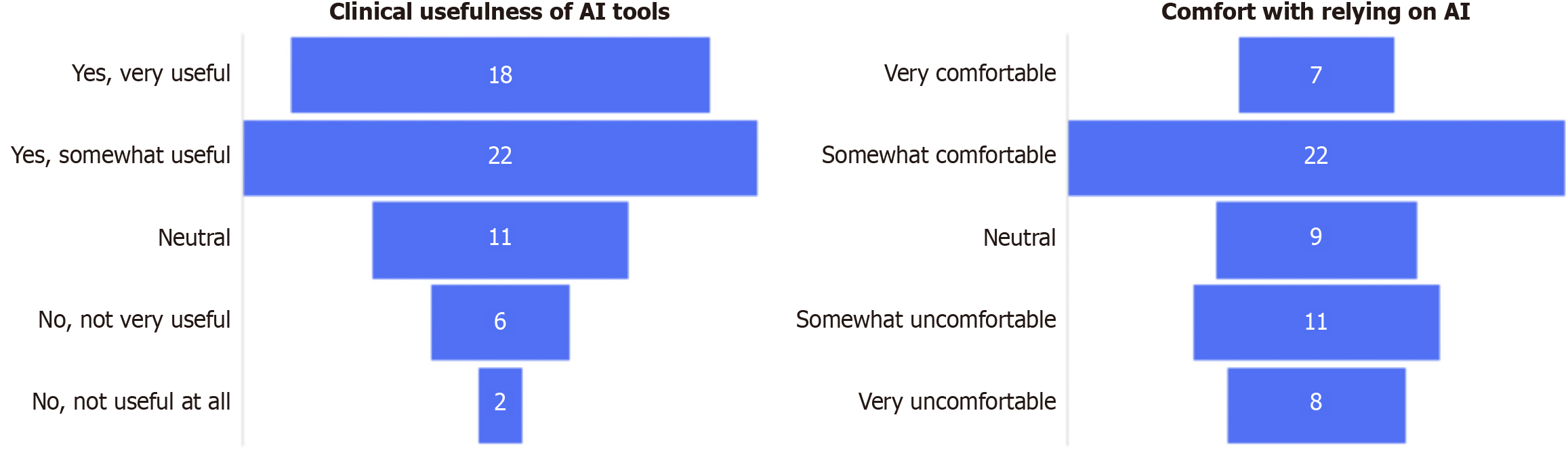

Regarding diagnostic confidence, 13% felt very comfortable relying on AI, while 39% were somewhat comfortable. A third (33%) were uncomfortable, and 16% were neutral. Similarly, 35% found AI very useful, 39% somewhat useful, 19% neutral, and 14% reported little to no utility (Figure 4).

Despite more than two thirds reporting the use of AI in their practice frequent use was limited to 28%. One-third (33%) reported no current use. Most respondents (68%) believed AI tools will become essential in emergency radiology in the next five years. Over half (51%) believed AI will replace certain tasks, while 33% disagreed and 16% were uncertain. 54% believed less experienced radiologists trust AI more, 21% believed more experienced radiologists do, and 25% saw no difference (Figure 5).

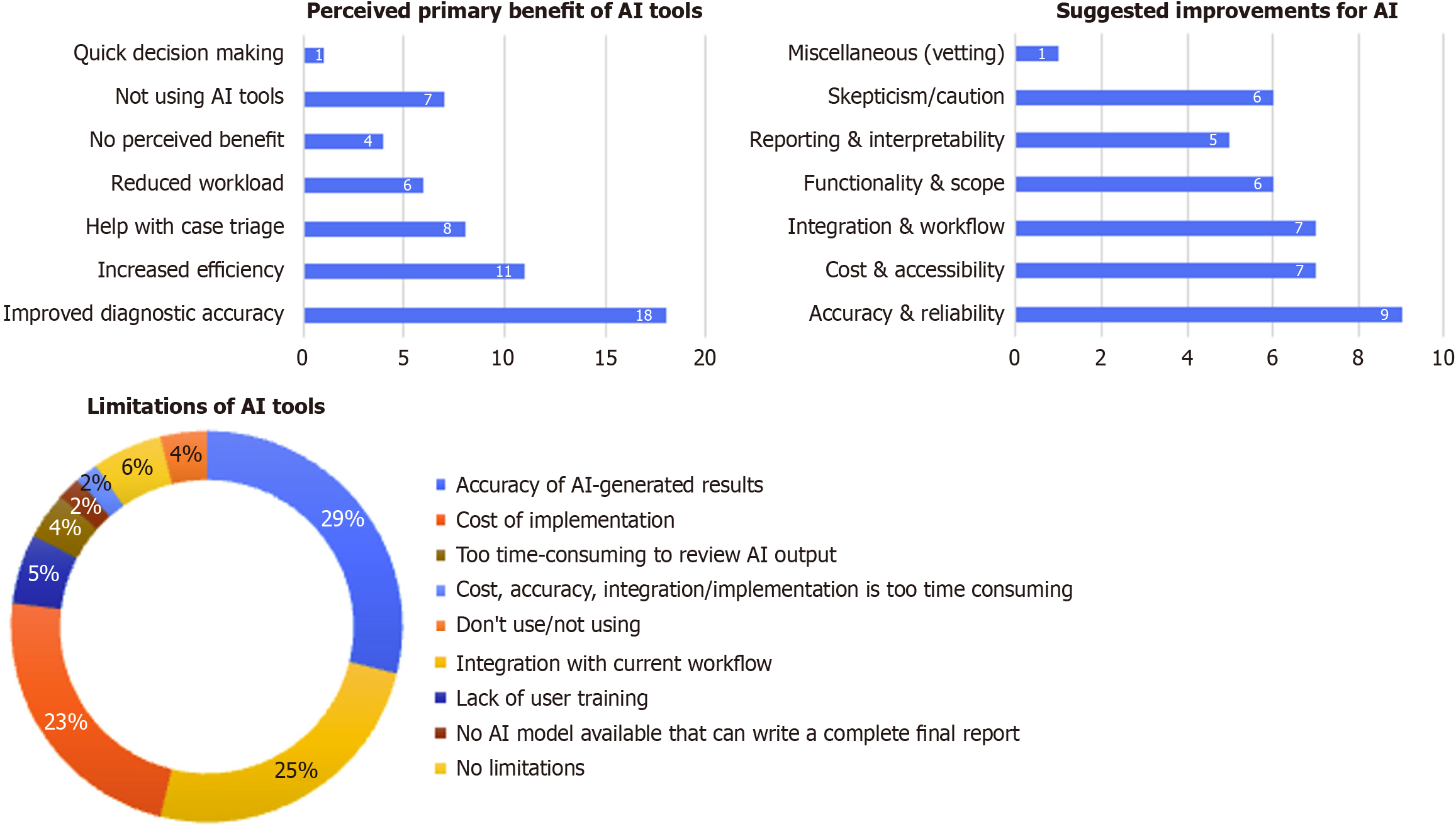

The most cited benefits were improved diagnostic accuracy (n = 18), increased efficiency (n = 11), and case triage assistance (n = 8). Other mentions included workload reduction (n = 6) and faster decision-making (n = 1). Four saw no benefit; seven were not using AI.

Major concerns included accuracy of results (n = 15), workflow integration (n = 13), and implementation cost (n = 12). Minor concerns included lack of training (n = 3), review time (n = 2), and incomplete report generation (n = 1). A few respondents reported no limitations or no use. Respondents highlighted the need to improve accuracy and reliability (n = 9), reduce cost and improve access (n = 7), integrate tools more effectively into clinical workflow (n = 7), expand functionality (n = 6), improve interpretability (n = 5), and address general skepticism (n = 6) (Figure 6).

This global survey provides valuable insights into the perceptions and use of AI among emergency radiologists. Despite high overall awareness (93%), only 28% of respondents reported frequent use of AI in clinical practice, with even fewer (23%) using AI daily in emergency imaging. This discrepancy between awareness and adoption suggests significant translational barriers that must be addressed before AI tools can be routinely implemented in emergent imaging workflows.

Accuracy and reliability were prominent concerns, cited by 26% of respondents. While 35% of radiologists found AI to be very useful, only 13% expressed strong diagnostic confidence when relying on AI, and a notable 33% were uncom

Workflow integration emerged as another major barrier, cited by 13 respondents. Although several participants reported using AI for image interpretation (32%) and acquisition (16%), adoption of tools for workflow optimization (5%) or impression generation (4%) was minimal. This suggests a fragmentation in how AI tools are being deployed - often siloed from broader reporting or triage systems. Such misalignment disrupts rather than enhances the radiologist’s workflow, contributing to underutilization. Furthermore, the fact that only a minority found AI useful for case triage (14%) - despite it being a major proposed benefit in emergency settings - indicates a need for better integration of AI into Picture Archiving and Communication System and Radiology Information System platforms, with real-time outputs and actionable insights[11,12].

Cost and accessibility were also cited as significant limitations (n = 12), particularly for institutions with limited financial or technical infrastructure. Although 91% of respondents were based in academic settings, the barriers they described are likely even more pronounced in community or private hospitals, which were underrepresented in the sample. Cloud-based solutions and modular, cost-effective tools could help overcome these obstacles, particularly in regions where radiology infrastructure is still developing. It's noteworthy that 33% of respondents reported no current AI use at all, underscoring the unequal global distribution of AI integration[13,14]. The geographic concentration of respondents in North America and Europe may partially explain the high awareness levels observed. To counteract this in future studies, targeted outreach to underrepresented regions such as Asia-Pacific, South America, and Africa through professional societies or radiology networks could yield more balanced insights into global readiness and infrastructure disparities.

The functionality and scope of current AI tools also appear too narrow to meet the full demands of emergency radiology. Although 68% of respondents believed AI will become essential in the next five years, only 23% use it daily for emergency imaging. The limited application to only a few use cases, such as image interpretation, likely restricts its perceived value. Comparable surveys in general radiology have reported daily AI use rates between 20%-40%, consistent with our 23% rate, supporting the notion that adoption barriers persist even in well-resourced environments[2,15]. For broader adoption, AI tools must evolve to support high-impact tasks—such as triaging critical trauma cases or segmenting acute findings across modalities. Expanding datasets to include more diverse pathologies and patient populations will be essential to support generalizability[16,17].

Experience and trust showed interesting variation: 54% of respondents believed less experienced radiologists are more trusting of AI. This generational divide in confidence and expectations suggests that AI literacy may be increasing among early-career radiologists, potentially accelerating future adoption. However, this trend may also reflect institutional factors rather than pure generational differences, as younger radiologists are often based in academic centers with earlier AI exposure. Future analyses stratifying by institution type could clarify this distinction. However, it also highlights the need for inclusive education strategies to bring senior radiologists onboard and avoid a bifurcated workforce where AI adoption is uneven[18,19].

Issues around interpretability and reporting were reflected in the minority uptake of AI for impression generation (n = 2). Many current tools provide only fragmented outputs, with limited integration into structured reporting. This undermines clinical utility, as radiologists must still manually reconcile AI findings with clinical impressions. Improved explainability - via techniques like heatmaps or layered confidence indicators - combined with auto-generated drafts that radiologists can review and edit, would help bridge this gap[20].

Finally, skepticism and caution remain widespread. Although 51% believed AI would eventually replace some tasks, a substantial 33% disagreed, and 16% were unsure. These attitudes reflect a broader ambivalence in the field - where enthusiasm for AI’s promise coexists with fear of over-automation, legal liability, and ethical uncertainty. Addressing these concerns will require not only technical improvements but also educational efforts and governance structures. For example, a hospital-level AI oversight committee that evaluates tools pre-deployment and monitors ongoing performance could build trust and ensure responsible use[21,22].

Taken together, these findings reinforce the importance of a phased roadmap for AI adoption in emergency imaging (Table 1), emphasizing foundational improvements in accuracy, workflow integration, and interpretability before expanding functionality or automation. Each phase of the proposed roadmap corresponds directly to themes identified in survey responses - for instance, phase 1 addresses accuracy and integration concerns (reported by 15 respondents and 13 respondents, respectively), while phase 2 aligns with calls for expanded functionality and triage capability. Despite a relatively modest sample size and overrepresentation of academic centers, the results offer a globally relevant snapshot of AI’s current and future role in emergency radiology.

| Phase | Focus | Objectives |

| Foundation | Accuracy, integration, and reporting | Clinical validation, real-time workflow integration, structured reporting, explainability |

| Expansion | Functionality and decision support | Broader coverage of emergent findings, triage tools, risk stratification, and follow-up tracking |

| Automation | Workflow optimization and customization | Automated notifications, user-defined outputs, prior study comparison, voice interface |

| Continuous learning | Adaptive integration and governance | Model updating, multi-modal data use, regulatory oversight, educational support |

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the sample size is relatively small, with 57 respondents, which limits the generalizability of the findings to the broader emergency radiology community. Second, the survey respondents were identified through academic publications in major radiology journals, resulting in a cohort primarily composed of academic radiologists. This may introduce a selection bias, as these individuals could have greater awareness and more positive attitudes toward AI compared to community or private practice radiologists. Third, the voluntary nature of survey participation may have led to a response bias, where radiologists with an interest or favorable opinion of AI were more likely to respond. Lastly, as a pilot study, these findings provide preliminary insights and should be validated in larger, more diverse populations across different practice settings to better understand global perspectives on AI in emergency radiology.

This pilot survey highlights both the enthusiasm and the persistent obstacles surrounding AI integration in emergency radiology. Despite strong perceived potential for improving diagnostic accuracy and efficiency, practical adoption remains limited by concerns about accuracy, cost, workflow integration, and trust. Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach involving rigorous validation, user-centered design, affordable and scalable solutions, and robust governance frameworks. By following a structured, phased development roadmap and emphasizing education and ethical oversight, AI tools can mature into reliable partners for radiologists, augmenting their expertise without compromising clinical judgment. Future multicenter collaborations involving professional radiology societies should focus on building standardized validation pipelines and AI literacy programs, ensuring that technological advances translate into measurable patient-care benefits.

| 1. | Perera Molligoda Arachchige AS, Svet A. Integrating artificial intelligence into radiology practice: undergraduate students' perspective. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:4133-4135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zanardo M, Visser JJ, Colarieti A, Cuocolo R, Klontzas ME, Pinto Dos Santos D, Sardanelli F; European Society of Radiology (ESR). Impact of AI on radiology: a EuroAIM/EuSoMII 2024 survey among members of the European Society of Radiology. Insights Imaging. 2024;15:240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Huisman M, Ranschaert E, Parker W, Mastrodicasa D, Koci M, Pinto de Santos D, Coppola F, Morozov S, Zins M, Bohyn C, Koç U, Wu J, Veean S, Fleischmann D, Leiner T, Willemink MJ. An international survey on AI in radiology in 1,041 radiologists and radiology residents part 1: fear of replacement, knowledge, and attitude. Eur Radiol. 2021;31:7058-7066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Perera Molligoda Arachchige AS, Stomeo N. Controversies surrounding AI-based reporting systems in echocardiography. J Echocardiogr. 2023;21:184-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sullivan GM, Artino AR Jr. Analyzing and interpreting data from likert-type scales. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:541-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1009] [Cited by in RCA: 1101] [Article Influence: 84.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Baek S, Yoon DY, Lim KJ, Cho YK, Seo YL, Yun EJ. The most downloaded and most cited articles in radiology journals: a comparative bibliometric analysis. Eur Radiol. 2018;28:4832-4838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Van Rossum G, Drake FL. Python 3 Reference Manual. CA: CreateSpace, 2009: 242. |

| 8. | Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel. [cited 15 October 2025]. Available from: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel. |

| 9. | Lakhani P, Sundaram B. Deep Learning at Chest Radiography: Automated Classification of Pulmonary Tuberculosis by Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Radiology. 2017;284:574-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 879] [Cited by in RCA: 827] [Article Influence: 91.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Oakden-Rayner L. The Rebirth of CAD: How Is Modern AI Different from the CAD We Know? Radiol Artif Intell. 2019;1:e180089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pesapane F, Codari M, Sardanelli F. Artificial intelligence in medical imaging: threat or opportunity? Radiologists again at the forefront of innovation in medicine. Eur Radiol Exp. 2018;2:35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 406] [Article Influence: 50.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jiang F, Jiang Y, Zhi H, Dong Y, Li H, Ma S, Wang Y, Dong Q, Shen H, Wang Y. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: past, present and future. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2017;2:230-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1189] [Cited by in RCA: 1620] [Article Influence: 180.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Kelly CJ, Karthikesalingam A, Suleyman M, Corrado G, King D. Key challenges for delivering clinical impact with artificial intelligence. BMC Med. 2019;17:195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1023] [Cited by in RCA: 1185] [Article Influence: 169.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Recht MP, Dewey M, Dreyer K, Langlotz C, Niessen W, Prainsack B, Smith JJ. Integrating artificial intelligence into the clinical practice of radiology: challenges and recommendations. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:3576-3584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cè M, Ibba S, Cellina M, Tancredi C, Fantesini A, Fazzini D, Fortunati A, Perazzo C, Presta R, Montanari R, Forzenigo L, Carrafiello G, Papa S, Alì M. Radiologists' perceptions on AI integration: An in-depth survey study. Eur J Radiol. 2024;177:111590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Litjens G, Kooi T, Bejnordi BE, Setio AAA, Ciompi F, Ghafoorian M, van der Laak JAWM, van Ginneken B, Sánchez CI. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med Image Anal. 2017;42:60-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5573] [Cited by in RCA: 5372] [Article Influence: 596.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Tang A, Tam R, Cadrin-Chênevert A, Guest W, Chong J, Barfett J, Chepelev L, Cairns R, Mitchell JR, Cicero MD, Poudrette MG, Jaremko JL, Reinhold C, Gallix B, Gray B, Geis R; Canadian Association of Radiologists (CAR) Artificial Intelligence Working Group. Canadian Association of Radiologists White Paper on Artificial Intelligence in Radiology. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2018;69:120-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Holzinger A, Langs G, Denk H, Zatloukal K, Müller H. Causability and explainability of artificial intelligence in medicine. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Data Min Knowl Discov. 2019;9:e1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 598] [Cited by in RCA: 493] [Article Influence: 70.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tjoa E, Guan C. A Survey on Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Toward Medical XAI. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2021;32:4793-4813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 371] [Cited by in RCA: 565] [Article Influence: 113.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Topol EJ. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2019;25:44-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2376] [Cited by in RCA: 3624] [Article Influence: 517.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 21. | Morley J, Machado CCV, Burr C, Cowls J, Joshi I, Taddeo M, Floridi L. The ethics of AI in health care: A mapping review. Soc Sci Med. 2020;260:113172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 50.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Amann J, Blasimme A, Vayena E, Frey D, Madai VI; Precise4Q consortium. Explainability for artificial intelligence in healthcare: a multidisciplinary perspective. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20:310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 496] [Cited by in RCA: 694] [Article Influence: 115.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/