Published online Dec 28, 2025. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v17.i12.116453

Revised: November 25, 2025

Accepted: December 10, 2025

Published online: December 28, 2025

Processing time: 44 Days and 21.3 Hours

The trigeminal nerve (TN) is frequently implicated in neurovascular conflicts, most commonly with the superior cerebellar artery (SCA), its predominant arterial counterpart in the cerebellopontine angle.

To examine the relationship between the SCA and TN utilizing high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging and evaluated whether particular anatomical configurations predispose to clinically significant contact.

Magnetic resonance imaging scans from 80 patients (160 sides) were retro

Eight distinct topographic patterns were identified. The SCA most commonly coursed superior (30.6%), lateral (18.8%), or superolateral (17.5%) to the TN. Medial configurations, although less frequent, were associated with the shortest artery-nerve distance (mean 1.85 ± 1.28 mm) and significantly higher contact rates (P < 0.001). Overall, SCA-TN contact was observed in 14.4% of sides, but only 20% of these patients reported ipsilateral facial numbness. Variations in SCA origin (basilar artery, posterior cerebral artery, or common origin) and duplication did not significantly influence the artery-nerve distance.

Although SCA-TN contact is relatively frequent, only particular medial and superior configurations seem to predispose individuals to symptomatic compression. These observations are consistent with cadaveric and surgical evidence highlighting the significance of root entry zone contact in trigeminal neuralgia. Vascular contact alone should not serve as a diagnostic criterion; instead, geometric configuration and related nerve alterations must also be incorporated into preoperative assessment.

Core Tip: This study examined the relationship between the superior cerebellar artery and trigeminal nerve utilizing high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging and evaluated whether particular anatomical configurations predispose to clinically significant contact. Eight distinct topographical patterns were identified. Medial configuration predisposed to shortest distance, significant higher contact rates, and in some cases, ipsilateral facial numbness. The proposed classification system could be used from anatomists, radiologists and neurosurgeons - for proper understanding of the relationship between these two structures.

- Citation: Triantafyllou G, Papadopoulos-Manolarakis P, Arkoudis NA, Moschovaki-Zeiger O, Velonakis G, Piagkou M. Magnetic resonance imaging-based classification of trigeminal nerve-superior cerebellar artery relationships. World J Radiol 2025; 17(12): 116453

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v17/i12/116453.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v17.i12.116453

The trigeminal nerve (TN, cranial nerve V) is the largest cranial nerve, with one of the broadest sensory distributions among the twelve cranial nerves. Its origin is situated in the lateral pons, and it traverses as the trigeminal root within the prepontine cistern[1]. Subsequently, in Meckel’s cave, it forms the trigeminal (Gasserian) ganglion. It trifurcates into three principal nerves, the ophthalmic (V1), maxillary (V2), and mandibular (V3) - each responsible for innervating facial and cranial territories, with motor fibers to the muscles of mastication carried in V3[1]. The primary (sensory) root of the TN is a typical locus of neuralgia, predominantly resulting from vascular compression[2].

The cerebellar arteries comprise three paired vessels that originate from the vertebrobasilar system and course in proximity to multiple cranial nerves[1]. An illustrative example is the superior cerebellar artery (SCA), which generally originates from the distal basilar artery (BA) and courses beneath the oculomotor and trochlear nerves[1]. However, Gray’s Anatomy does not explicitly detail the critical relationship of the SCA with the TN[1]. Numerous studies have documented the morphological variability of the SCA using imaging techniques[3,4]; however, only a limited number of cadaveric investigations have examined the neural relationships of the SCA[5,6]. Furthermore, numerous publications have documented the neurovascular relationship of the TN in patients with or without trigeminal neuralgia[7-10].

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the SCA-TN relationship using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. Based on earlier observations, our initial hypothesis was that this relationship varies and that their relative arrangement could influence potential contact between the neurovascular structures. We also hypothesized that specific configurations might be linked to clinical symptoms.

A retrospective analysis was conducted on a randomly selected archived cohort consisting of 80 patients (40 females and 40 males) who underwent MRI. The average age of the participants was 53.3 ± 17.8 years. Patients exhibiting pathological processes within the cerebellopontine angle or TN pathologies, such as atrophy, were excluded. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the General Hospital of Nikaia-Piraeus, approval No. 13.11.2024.

All examinations were conducted using a Philips 3T Achieva TX MRI scanner (Philips, Best, Netherlands) equipped with an 8-channel head coil. The imaging protocol included time-of-flight (TOF), T2-weighted, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, and T1-weighted sequences acquired both pre- and post-intravenous gadolinium contrast in three-dimensional (3D) datasets, along with diffusion-weighted imaging and susceptibility-weighted imaging. For this study, the images selected for further analysis comprised post-contrast T1- and T2-weighted sequences, as well as TOF. Image analysis was performed using Horos software (version 3.3.6), which facilitated multiplanar reconstruction (axial, coronal, and sagittal) and 3D volume rendering to ensure precise anatomical assessment.

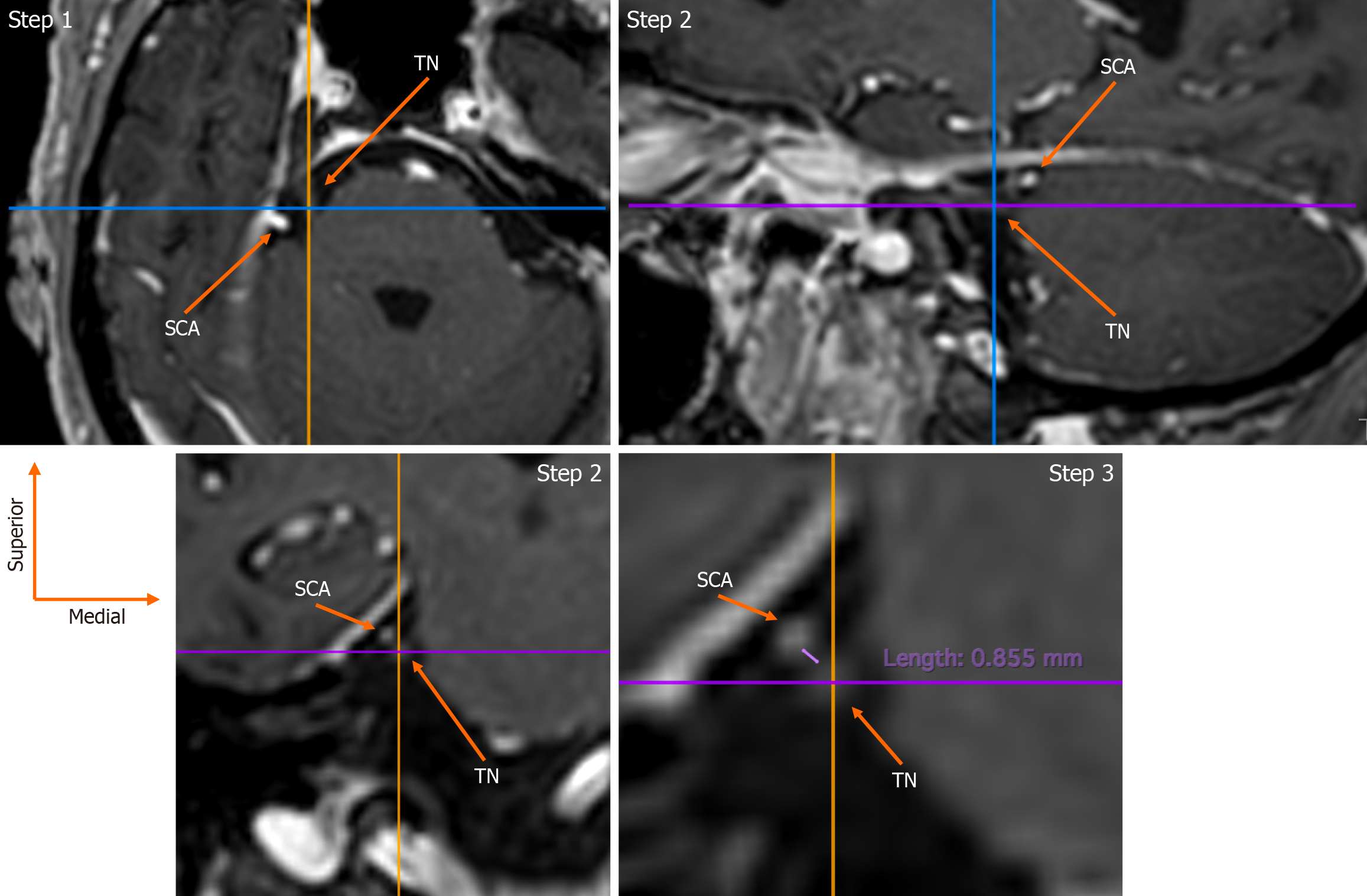

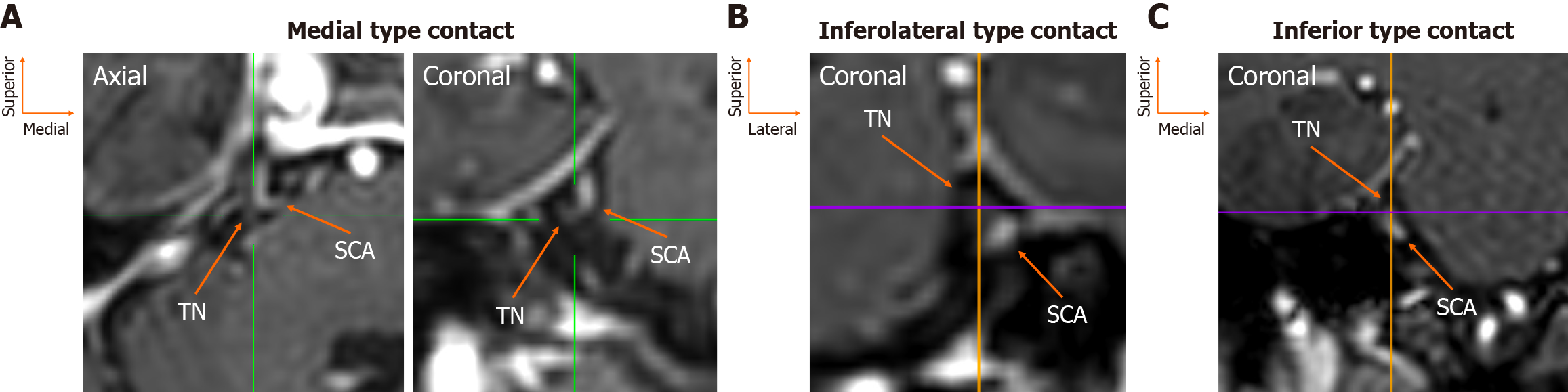

The assessment was conducted by an experienced anatomist (George Triantafyllou) and a neurosurgeon (Panagiotis Papadopoulos-Manolarakis), with any disagreements resolved through consultation with two seasoned neuroradiologists (Nikolaos-Achilleas Arkoudis, George Velonakis). The root entry zone (REZ) of the TN root was identified as originating from the lateral pons in axial slices (Figure 1). Utilizing multiplanar reconstruction, this was also observed in coronal and sagittal views (Figure 1). The spatial relationship, distance, and potential contact with the SCA were evaluated in coronal sections (Figure 1). Additionally, the origin of the SCA was documented in coronal slices via maximum intensity projection. Furthermore, the clinical history of the patients was examined in cases where contact between the SCA and the TN was present.

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for macOS, Version 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Graphical representations were generated with RStudio (version 4.3.2) utilizing the “ggplot2” package. Nominal data from unpaired observations were compared with the χ2 test, whereas McNemar’s test was applied to paired observations. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Continuous variables were analyzed based on their measurement type: Unpaired measurements were evaluated with an independent t-test if normality assumptions were met; otherwise, the Mann-Whitney U test was employed. Paired measurements were compared using a paired t-test when normality was satisfied. Mean differences across more than two groups were examined with one-way analysis of variants if the data followed a normal distribution; if not, the Kruskal-Wallis test was utilized. Results are presented as mean ± SD unless specified otherwise. A P value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

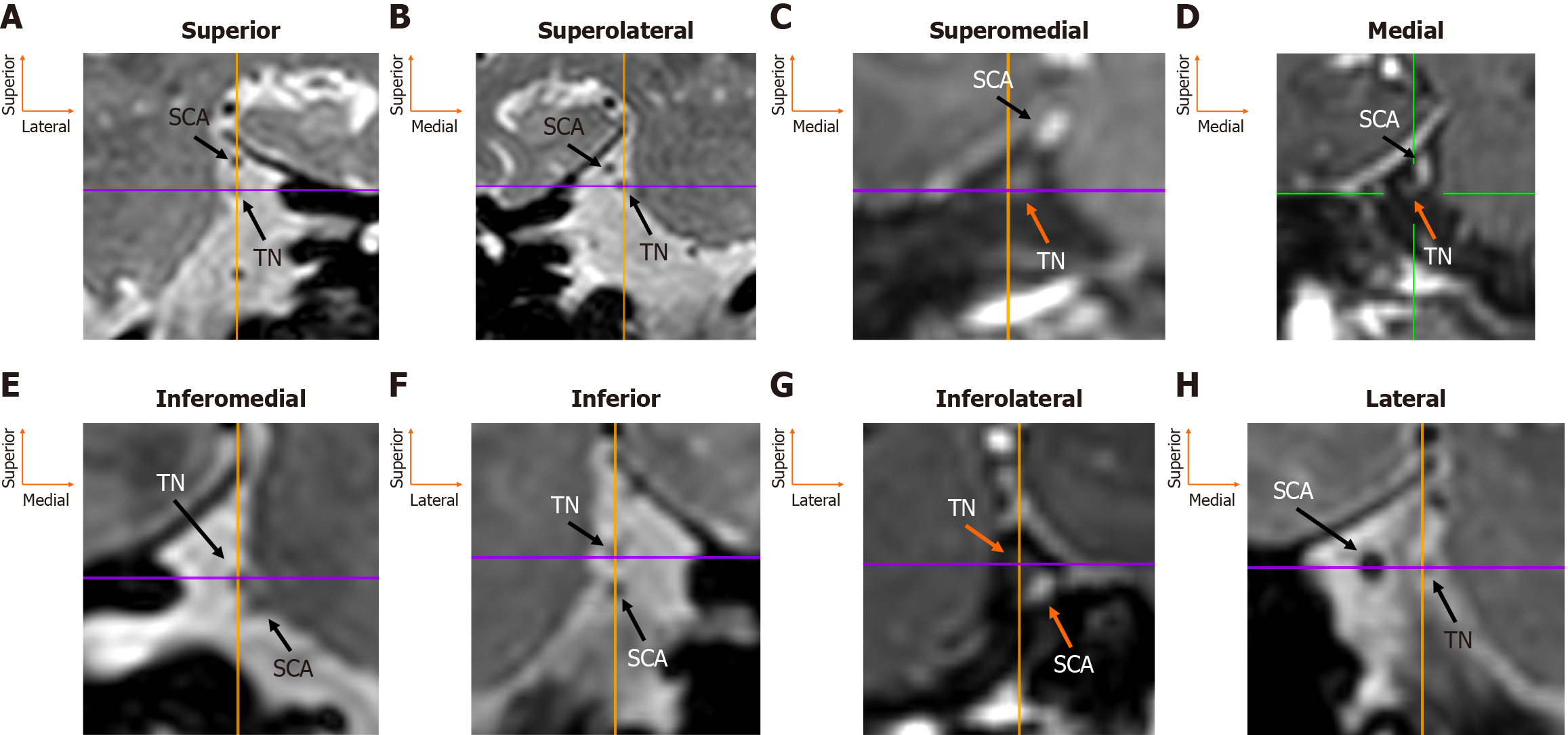

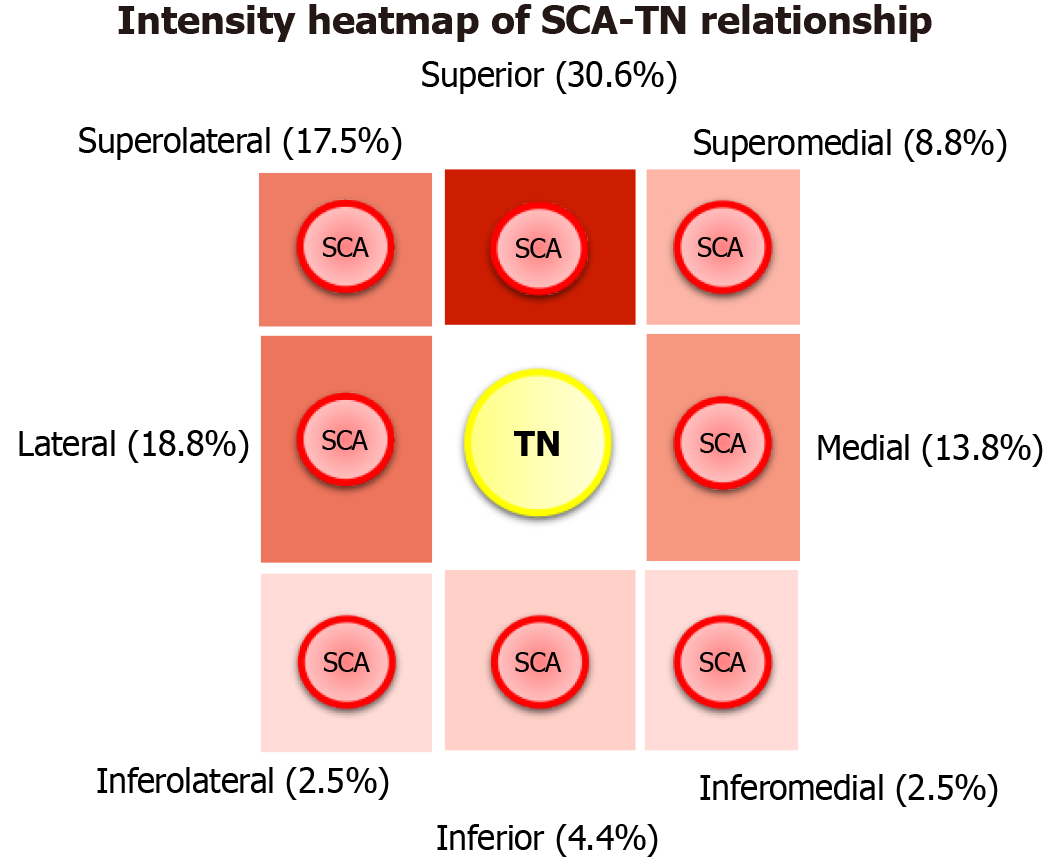

The TN root was identified arising from the lateral pons in all patients (160/160, 100%), whereas the SCA was absent on two sides (2/160, 1.3%). At the REZ, eight topographical possibilities were recorded. The most common position was the SCA superior to the TN in 49 sides (49/160, 30.6%). The second most common position was the SCA lateral to the TN in 30 sides (30/160, 18.8%), and the third most common was the artery superolateral to the nerve in 28 sides (28/160, 17.5%). The superomedial position of the SCA relative to the TN was observed in 14 sides (14/160, 8.8%). Less frequent topographical locations were inferior (7/160, 4.4%), inferolateral, and inferomedial (both 4/160, 2.5%) (Figure 2). Side (left vs right) and sex did not influence the relationship between the SCA-TN (P = 0.852 and P = 0.209, respectively) (Table 1). In total, 31 patients had symmetrical morphology (38.8%), and 49 patients had asymmetrical morphology (61.2%). Twelve patients had bilateral superior type, seven had symmetrical superolateral type, six had bilateral lateral type, four had symmetrical medial type, one had bilateral superomedial type, and one had symmetrical inferomedial type.

| SCA-TN relationship | Total (n = 160) | Left (n = 80) | Right (n = 80) | P value | Females (n = 80) | Males (n = 80) | P value |

| Superior | 49 (30.6) | 22 (27.5) | 27 (33.8) | 0.852 | 28 (35) | 21 (26.3) | 0.209 |

| Superolateral | 28 (17.5) | 14 (17.5) | 14 (17.5) | 10 (12.5) | 18 (22.5) | ||

| Superomedial | 14 (8.8) | 9 (11.3) | 5 (6.3) | 7 (8.8) | 7 (8.8) | ||

| Medial | 22 (13.8) | 9 (11.3) | 13 (16.3) | 7 (8.8) | 15 (18.8) | ||

| Lateral | 30 (18.8) | 17 (21.3) | 13 (16.3) | 17 (21.3) | 13 (16.3) | ||

| Inferior | 7 (4.4) | 3 (3.8) | 4 (5) | 3 (3.8) | 4 (5) | ||

| Inferomedial | 4 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) | 3 (3.8) | 1 (1.3) | ||

| Inferolateral | 4 (2.5) | 3 (3.8) | 1 (1.3) | 3 (3.8) | 1 (1.3) |

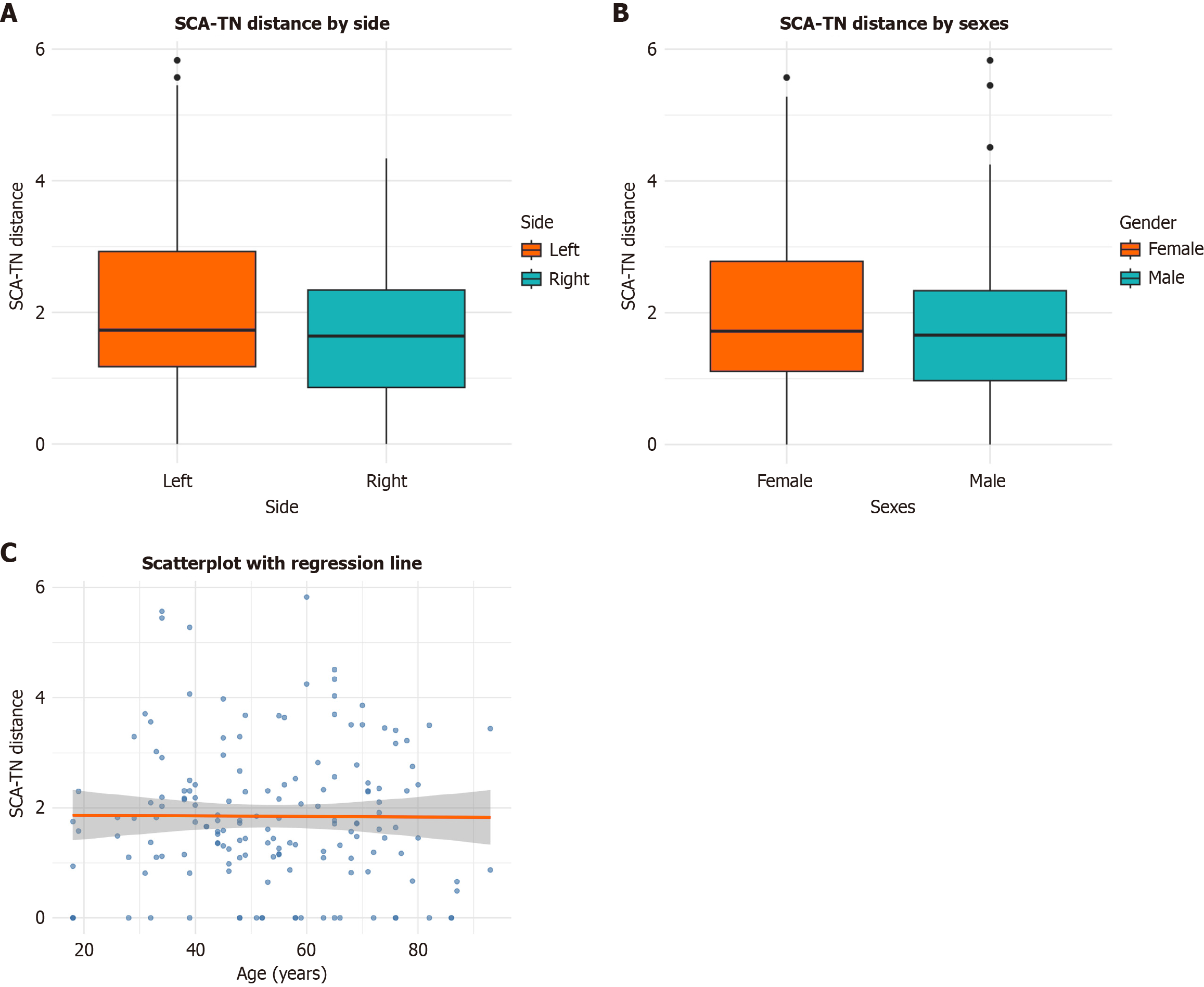

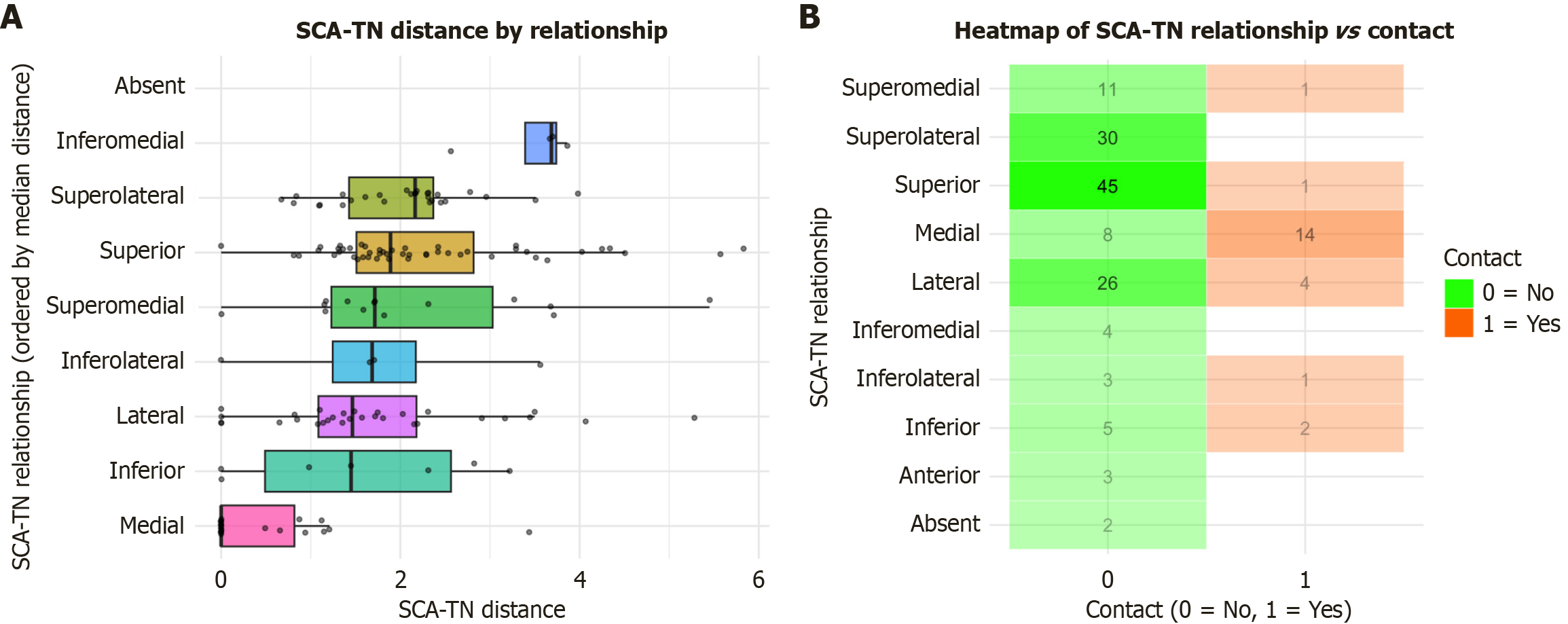

The mean distance between the SCA and the TN was 1.85 ± 1.28 mm. Laterality, sex, and age did not exert a significant influence on the distance between these structures (P = 0.173, P = 0.427, and P = 0.929, respectively) (Figure 3, Table 2). Nonetheless, the type of SCA-TN relationship significantly affected their distance (P < 0.001) (Figure 4, Table 3). Contact between the SCA and the TN was observed in 23 sides (23/160, 14.4%), with no significant effect of side or sex (P = 0.115 and P = 0.231, respectively) (Figure 5). The medial positioning of the SCA relative to the TN was associated with a significantly higher likelihood of contact compared to other configurations (Figure 4). In total, three patients exhibited bilateral contact, while 17 patients exhibited unilateral contact. Of the 20 patients with this variation, four (20%) reported numbness of the ipsilateral hemifacial region, which could be attributable to SCA-TN contact.

| SCA-TN distance | Total (n = 160) | Left (n = 80) | Right (n = 80) | P value | Females (n = 80) | Males (n = 80) | P value |

| Coronal distance | 1.85 (1.28) | 2.04 (1.37) | 1.65 (1.15) | 0.173 | 1.94 (1.27) | 1.76 (1.29) | 0.427 |

| SCA-TN relationship | SCA-TN distance |

| Superior | 2.29 (1.22) |

| Superolateral | 2.03 (0.78) |

| Superomedial | 2.15 (1.41) |

| Medial | 0.45 (0.81) |

| Lateral | 1.72 (1.25) |

| Inferior | 1.52 (1.45) |

| Inferomedial | 3.45 (0.60) |

| Inferolateral | 1.73 (1.45) |

| P value | < 0.0011 |

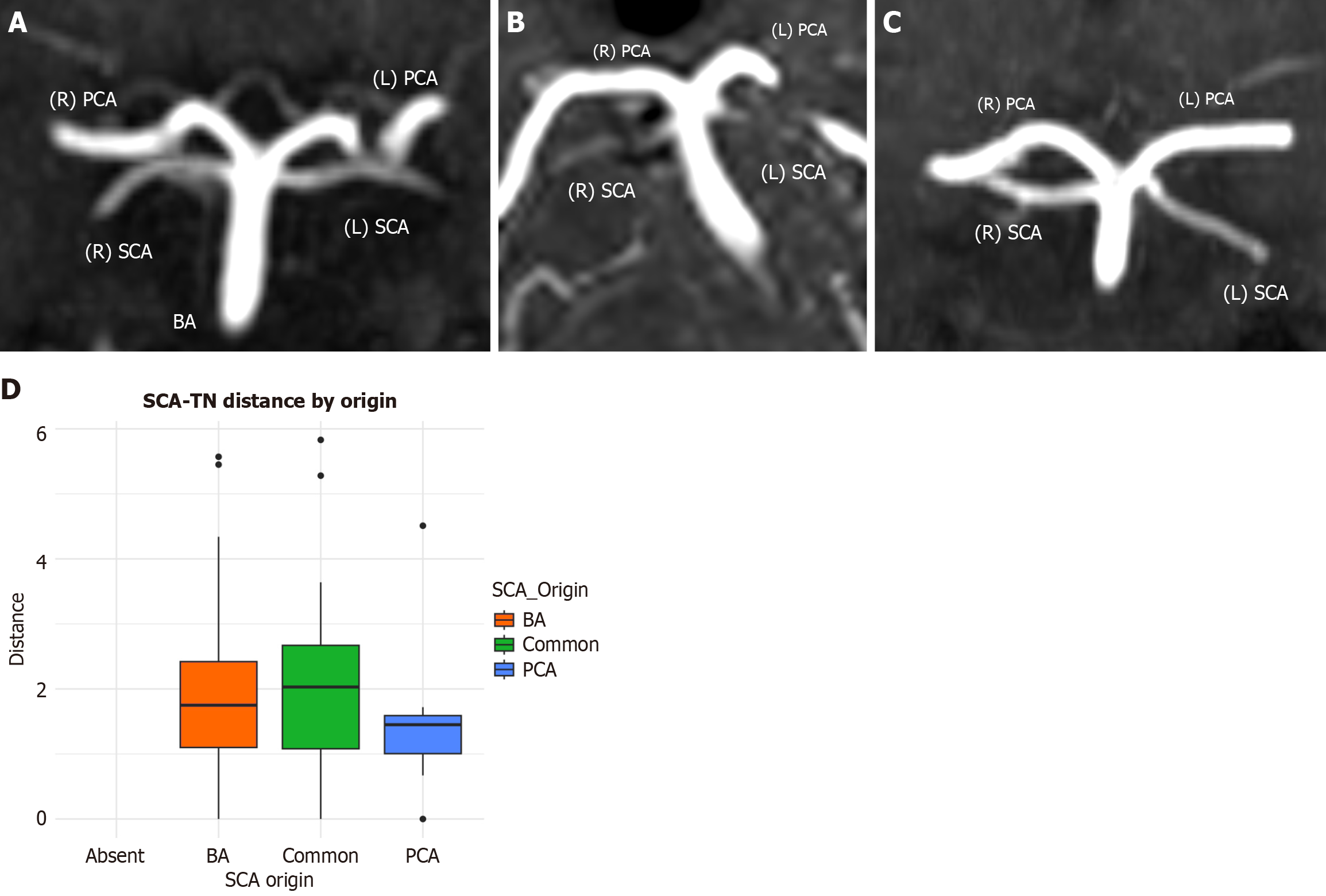

The SCA originated from the BA in 126 sides (126/160, 78.9%), shared a common origin with the PCA in 21 sides (21/160, 13.1%), and arose from the PCA in 11 sides (11/160, 6.9%) (Figure 6). We also observed six cases of duplication, two cases of early bifurcation, and two cases of absence. Neither side nor sex significantly influenced the SCA point of origin (P = 0.207 and P = 0.310, respectively). The SCA origin did not affect the distance between the artery and the TN (P = 0.431, Figure 6).

In this radio-anatomical study, we identified eight configurations for the relationship between the TN and the SCA (Figure 7). Additionally, the medial configuration was associated with the shortest distance between the structures and showed a higher frequency of contact.

Cadaveric studies consistently identify the SCA as the most stable arterial neighbor of the TN in the cerebellopontine angle, along with a dense venous network dominated by the petrosal veins complex. In a meticulous microsurgical series of 50 TNs derived from 25 adult heads, Hardy and Rhoton[11] observed contact between the SCA and the TN in 26 out of 50 sides (52%). The contact was predominantly along the superior or superomedial surface of the nerve. In six instances, contact occurred precisely at the REZ. They highlighted that a caudally projecting loop of the SCA, often the caudal trunk following the first bifurcation, was the typical anatomical configuration most associated with contact[11]. Furthermore, they documented cases of early bifurcation and even duplication of the SCA, which represent additional variants influencing the neurovascular interface[11]. The authors advised caution, noting that frequent arterial contact observed in elderly, more tortuous vessels might inflate contact rates in cadaveric studies compared with clinical imaging series.

Rusu et al[6] expanded the anatomical perspective by demonstrating that the SCA and the superior petrosal vein constitute a “supratrigeminal layer” positioned above the cisternal TN. The SCA is frequently divided into medial and lateral trunks as it traverses the nerve. Additionally, they identified rare variations, including a duplicated origin of the two SCA branches from the BA in one specimen, a radicular trigeminal artery arising from the BA in 5% of cases, interradicular arteries or veins at the REZ, and bony lamellae superior to the TN embedded within the tentorial-petroclinoid complex[6]. These lamellae may constrict relevant pathways and produce atypical neurovascular conflicts. Collectively, these findings suggest that both the branching pattern of the SCA and venous architecture, including petrosal and transverse pontine tributaries, are critical factors influencing the relationships of the TN in the superior, superolateral, and superomedial directions[6].

By synthesizing these anatomical data with our MRI observations, we infer that the SCA most commonly approaches the TN from above, with a tendency for superomedial or medial loops into the pons, exhibiting configurations that pre

Importantly, histological and imaging studies have emphasized that the most vulnerable site of TN compression is the transition zone between central and peripheral myelin, located approximately 2-4 mm from the brainstem surface. This reinforces that symptomatic neurovascular compression is more likely when contact occurs proximally, close to the transition zone, rather than along distal cisternal segments[12,13].

Radiological studies have enhanced our understanding of the TN-SCA relationship by assessing both symptomatic and asymptomatic groups using high-resolution MRI techniques. Several studies have demonstrated that vascular contact of the TN is common even in individuals without trigeminal neuralgia. Adamczyk et al[7] examined 120 TNs in 60 asymptomatic patients and reported arterial contact in 25%, most commonly by the SCA. Importantly, no cases showed nerve deformation except for one instance of mild atrophy, reinforcing that contact alone is often incidental. Lin et al[14] employed diffusion tensor imaging to examine twenty asymptomatic individuals with unilateral SCA compression. Their investigation revealed no evidence of demyelination or axonal injury when compared with control subjects, even though the SCA was implicated in 80% of cases[14]. Both studies suggest that neurovascular compression is not invariably pathological[7,14]. Moreover, in our cohort, 80% of patients with artery-nerve contact were asymptomatic.

In contrast, radiological studies of patients with classical trigeminal neuralgia consistently implicate the SCA as the most common offending vessel. Yousry et al[15] demonstrated with 3D-constructive interference in steady state and TOF-magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) that the SCA contacted the sensory root in nearly half of patients, and often the superior motor root as well, highlighting multiple potential sites of neurovascular interaction. Yamoto et al[10] employed 3D reconstructions across 34 surgical cases and demonstrated that medial courses of the SCA most frequently exert compression on the REZ. In contrast, cranial or lateral loops tend to compress more distal nerve segments. The morphology of the SCA (arch, inverted arch, or linear) affected the precise site of compression, with an arch-shaped SCA most often indenting the medial REZ[10]. More recently, Huang et al[8] demonstrated the diagnostic accuracy of advanced imaging. In a cohort of 240 patients undergoing microvascular decompression, the SCA was identified as the responsible vessel in approximately 62% of cases, either alone or in conjunction with veins or other arteries. The incorporation of magnetic resonance virtual endoscopy alongside 3D-TOF and 3D-fast imaging employing steady-state acquisition sequences enhanced diagnostic precision, notably in detecting venous conflicts, while also reaffirming the predominance of SCA involvement[8].

Our findings have several practical implications for the diagnosis and management of trigeminal neuralgia, as well as for pre-operative planning. First, classifying the SCA–TN geometry into discrete topographic types adds evidence-based context beyond a binary “contact/no contact”. The medial configurations in our cohort were associated with the shortest artery-nerve distances and the highest contact rates. This pattern mirrors microsurgical and imaging observations that symptomatic compression often occurs at the REZ on the superior/superomedial side of the nerve, precisely at the point where SCA loops tend to nestle between the pons and the medial edge of the trigeminal root[11]. This geometry matters surgically, because medial/superior SCA loops are the ones most often implicated during microvascular decompression and are frequently the target for transposition[5,11].

Second, our observation that only a subset of SCA-TN contacts was symptomatic aligns with the broader literature showing that neurovascular contact is common in people without neuralgia[7]. In asymptomatic volunteers, artery-REZ contact may be present in roughly a quarter of nerves, with minimal deformation or atrophy, underscoring why “contact alone” should not be equated with symptoms[7]. Consistently, a blinded case-control study with meta-analysis demonstrated that REZ contact plus anatomical nerve changes (dislocation/atrophy) had very high specificity. When REZ contact coexisted with atrophy, the positive predictive value for classical neuralgia reached 100%[16]. Thus, our “medial type” signal should be interpreted alongside REZ involvement and nerve deformation/atrophy.

Third, our data showed that variation in SCA origin (BA, common, or posterior cerebral artery) and branching variants (early bifurcation or duplication) did not influence SCA-TN distance. However, cadaveric series show that origin variants and duplications are frequent but do not, by themselves, predict whether a loop will impinge on the trigeminal root[11]. What does change the local mechanics is branching/bifurcation close to the nerve: Duplicated or early-bifurcating SCAs can create multi-point contacts or combined superior-superomedial topography, as also emphasized in detailed anatomic mapping of medial/Lateral SCA divisions around the trigeminal REZ[6]. Although these variations were not statistically significant in our sample, a larger cohort would better assess their impact. Recognizing these variants before surgery can help anticipate the need for multi-site transposition or customized pledget placement.

Fourth, veins and multi-vessel conflicts deserve explicit attention. Vein-only or vein-artery combinations can be clinically relevant and are easy to undercall on standard sequences[9]. In a large surgical cohort, adding magnetic resonance virtual endoscopy to 3D-fast imaging employing steady-state acquisition and 3D-TOF-MRA significantly improved the accuracy of identifying the responsible vessels, with the clearest gains for venous conflicts and multiple-vessel situations - particularly when vessels and nerves are isointense on heavily T2-weighted cisternal imaging[8]. Magnetic resonance virtual endoscopy with 3D intraluminal perspective can also unmask dual SCA branches compressing the nerve from above, a configuration we observed in our cohort and that has been illustrated with virtual endoscopy reconstructions[8].

Lastly, our results can be translated into a practical imaging-to-surgery workflow that includes: (1) Screening and localization with thin-slice, high-resolution T1/T2 in multiple planes to establish whether contact occurs at the REZ and whether a medial/superior configuration is present[2]; (2) Vessel characterization by fusing 3D-TOF-MRA to label arteries and adding magnetic resonance virtual endoscopy reconstructions when the relationship is ambiguous, venous involvement is suspected, or multiple vessels are seen, a combination that improves responsible-vessel identification and surgical planning[12]; and (3) Pathophysiologic weighting that prioritizes REZ location and nerve changes (indentation/displacement/atrophy) over mere contact to stratify surgical candidacy, as supported by meta-analytic evidence[16].

Although the current study presents novel findings, several limitations should be considered. Firstly, the sample size (n = 160 sides) was adequate for initial analysis; however, a larger sample would increase the representation of SCA variants. Secondly, a single-center design introduces selection bias and limits generalizability. Although 3T MRI with TOF and multiplanar reconstruction provides high-resolution images, small-caliber vessels and veins are often underrepresented, meaning that relevant neurovascular conflicts may have been underestimated. Moreover, the inferior cerebellar arteries and veins were not systematically assessed in the current study. Also, we did not explicitly measure the distance of contacts relative to the transition zone. Both aforementioned points will be a subject of future projects. Lastly, clinical correlations were restricted to retrospective chart review, and asymptomatic contacts are common, making it difficult to distinguish incidental from clinically meaningful findings.

In this MRI-based anatomical study, we identified eight distinct topographical relationships between SCA and TN. The medial configuration was associated with the closest artery-nerve distance and the highest likelihood of contact. Importantly, although SCA-TN contact was observed in approximately 14.4% of sides, only a minority of these patients reported trigeminal symptoms, underscoring that neurovascular contact is common but not necessarily pathological. Our results, therefore, suggest that preoperative assessment should go beyond simple detection of vascular contact and incorporate the geometry of the SCA-TN relationship, especially medial configurations and REZ involvement. Future studies integrating advanced sequences such as magnetic resonance virtual endoscopy, diffusion tensor imaging, and direct surgical correlation will be essential to validate these radiological predictors and to distinguish better incidental from symptomatic contacts.

| 1. | Standring S, Tunstall R. Gray's Anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice. 41st ed. London: Elsevier, 2015. |

| 2. | Tsutsumi S, Ono H, Yasumoto Y, Ishii H. The trigeminal root: an anatomical study using magnetic resonance imaging. Surg Radiol Anat. 2018;40:1397-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Davidoiu AM, Lazăr M, Vrapciu AD, Rădoi PM, Toader C, Rusu MC. An Update on the Superior Cerebellar Artery Origin Type. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59:2164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Papadopoulos-Manolarakis P, Triantafyllou G, Papanagiotou P, Tsakotos G, Christodoulou E, Piagkou M. Considerations regarding the morphological variability of the superior cerebellar artery. Neuroradiology. 2025;67:1997-2004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hardy DG, Peace DA, Rhoton AL Jr. Microsurgical anatomy of the superior cerebellar artery. Neurosurgery. 1980;6:10-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rusu MC, Ivaşcu RV, Cergan R, Păduraru D, Podoleanu L. Typical and atypical neurovascular relations of the trigeminal nerve in the cerebellopontine angle: an anatomical study. Surg Radiol Anat. 2009;31:507-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Adamczyk M, Bulski T, Sowińska J, Furmanek A, Bekiesińska-Figatowska M. Trigeminal nerve - artery contact in people without trigeminal neuralgia - MR study. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13 Suppl 1:38-43. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Huang Y, Huang Y, Xiao C, Huang Q, Chai X. Preoperative Evaluation of Neurovascular Relationship in Primary Trigeminal Neuralgia(PTN) by Magnetic Resonance Virtual Endoscopy(MRVE) Combined with 3D-FIESTA-c and 3D-TOF-MRA. J Pain Res. 2024;17:2561-2570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lang E, Naraghi R, Tanrikulu L, Hastreiter P, Fahlbusch R, Neundörfer B, Tröscher-Weber R. Neurovascular relationship at the trigeminal root entry zone in persistent idiopathic facial pain: findings from MRI 3D visualisation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1506-1509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yamoto T, Nishibayashi H, Ogura M, Nakao N. Three-dimensional morphology of the superior cerebellar artery running in trigeminal neuralgia. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;82:9-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hardy DG, Rhoton AL Jr. Microsurgical relationships of the superior cerebellar artery and the trigeminal nerve. J Neurosurg. 1978;49:669-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Haller S, Etienne L, Kövari E, Varoquaux AD, Urbach H, Becker M. Imaging of Neurovascular Compression Syndromes: Trigeminal Neuralgia, Hemifacial Spasm, Vestibular Paroxysmia, and Glossopharyngeal Neuralgia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37:1384-1392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cetković M, Antunović V, Marinković S, Todorović V, Vitošević Z, Milisavljević M. Vasculature and neurovascular relationships of the trigeminal nerve root. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2011;153:1051-7; discussion 1057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lin W, Chen YL, Zhang QW. Vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve in asymptomatic individuals: a voxel-wise analysis of axial and radial diffusivity. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2014;156:577-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yousry I, Moriggl B, Holtmannspoetter M, Schmid UD, Naidich TP, Yousry TA. Detailed anatomy of the motor and sensory roots of the trigeminal nerve and their neurovascular relationships: a magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:427-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Antonini G, Di Pasquale A, Cruccu G, Truini A, Morino S, Saltelli G, Romano A, Trasimeni G, Vanacore N, Bozzao A. Magnetic resonance imaging contribution for diagnosing symptomatic neurovascular contact in classical trigeminal neuralgia: a blinded case-control study and meta-analysis. Pain. 2014;155:1464-1471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/