©The Author(s) 2025.

World J Radiol. Dec 28, 2025; 17(12): 114595

Published online Dec 28, 2025. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v17.i12.114595

Published online Dec 28, 2025. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v17.i12.114595

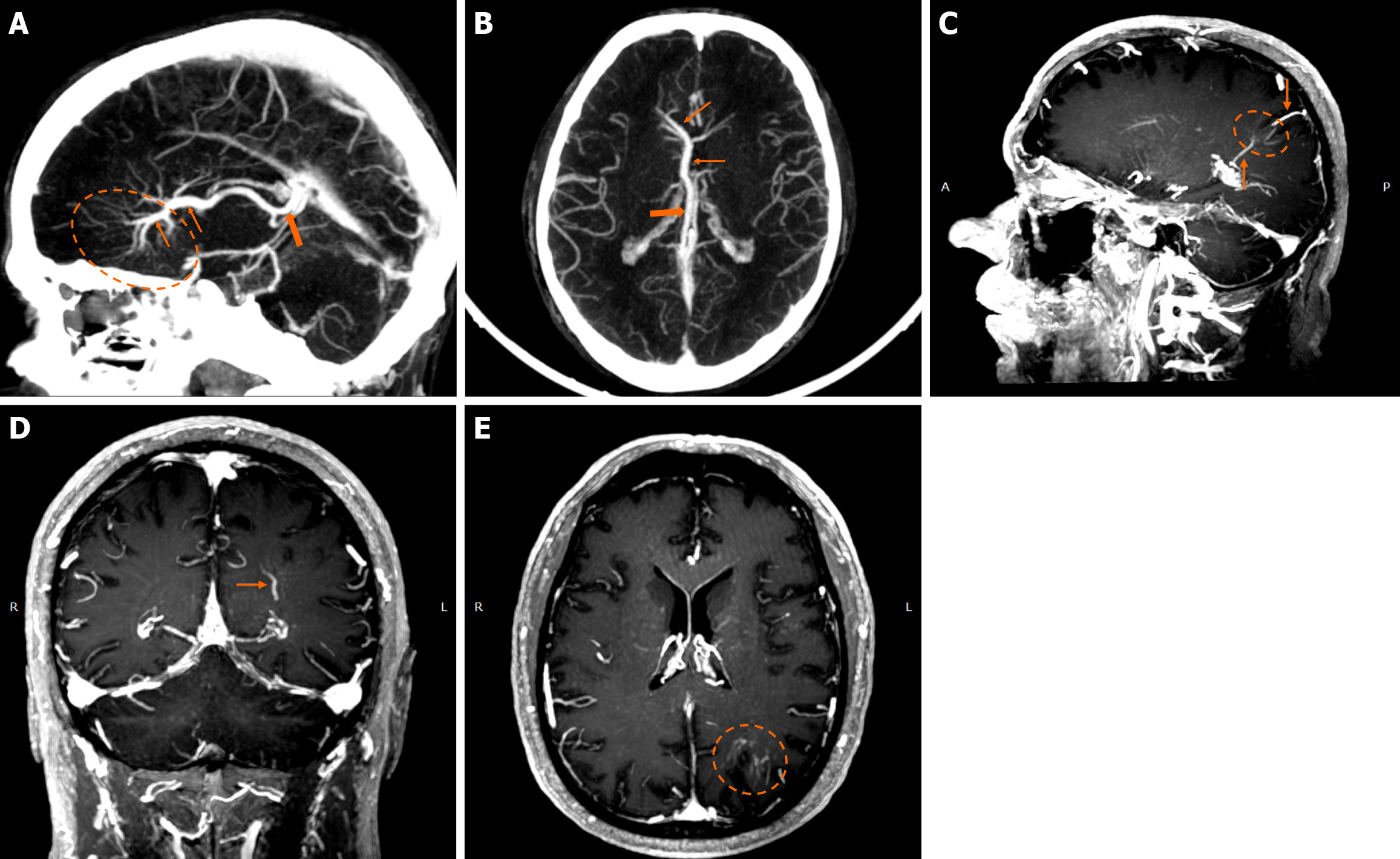

Figure 1 Developmental venous anomalies.

A and B: Sagittal (A) and axial (B) maximum intensity projection reconstruction of a contrast-enhanced computed tomography venography demonstrate a very large developmental venous anomaly in the right frontal lobe, evident by the “caput medusae” morphology (dashed oval) converging in collector veins (thin arrows) and draining in the right internal cerebral vein (thick arrow). Developmental venous anomalies are rarely this large and are usually not easily discernible in computed tomography scans; nonetheless, this example is provided for educational purposes due to its size and characteristic “caput medusae” morphology; C-E: Maximum intensity projection, of T1-weighted sagittal (C), coronal (D) and axial reconstruction images (E) following intravenous gadolinium administration demonstrate a developmental venous anomaly in the left parietal lobe, apparent by the characteristic “caput medusae” (dashed circle) and draining veins (arrows).

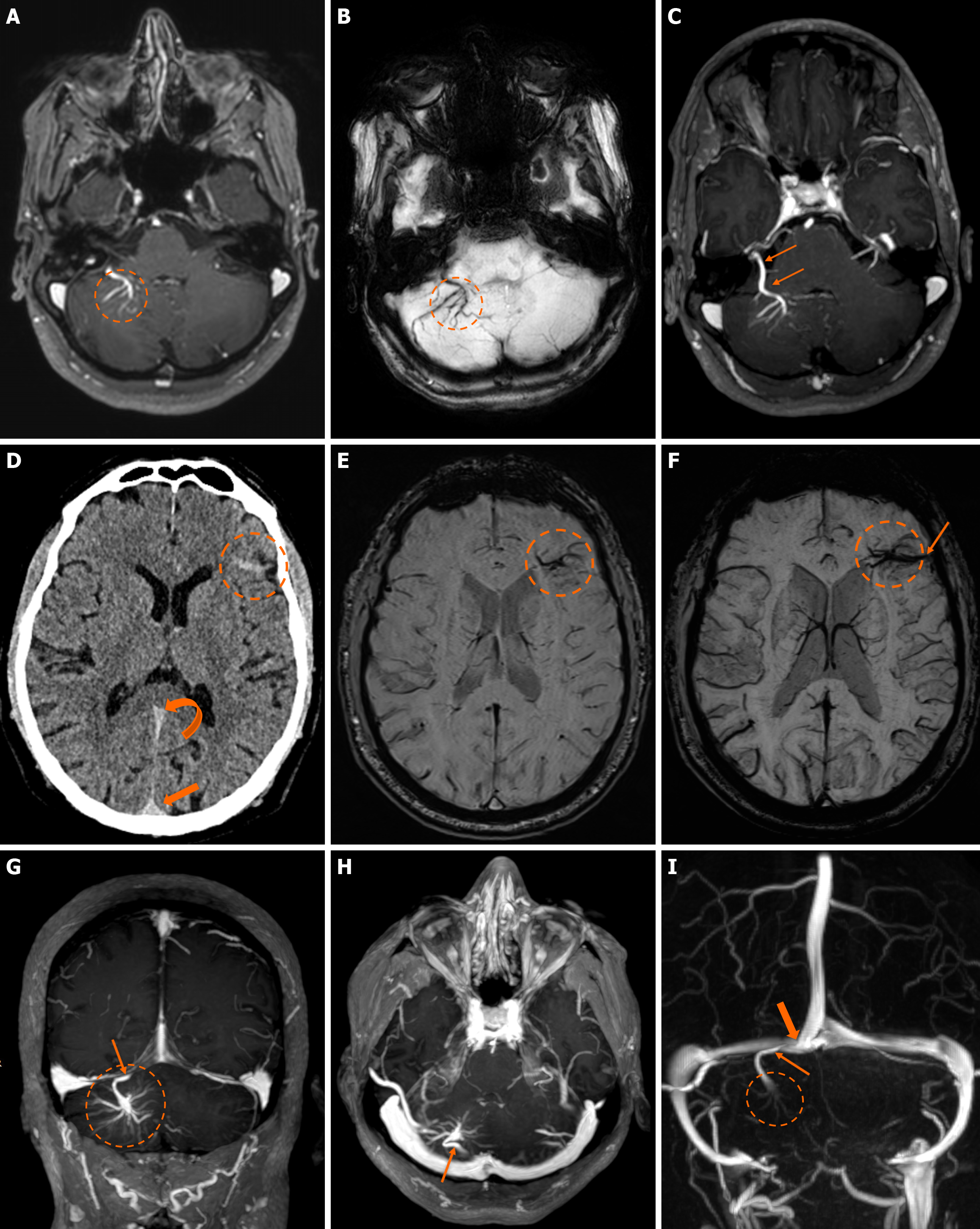

Figure 2 Developmental venous anomalies.

A and B: T1-weighted (T1w) axial (A) image following intravenous gadolinium administration, and (B) suscep

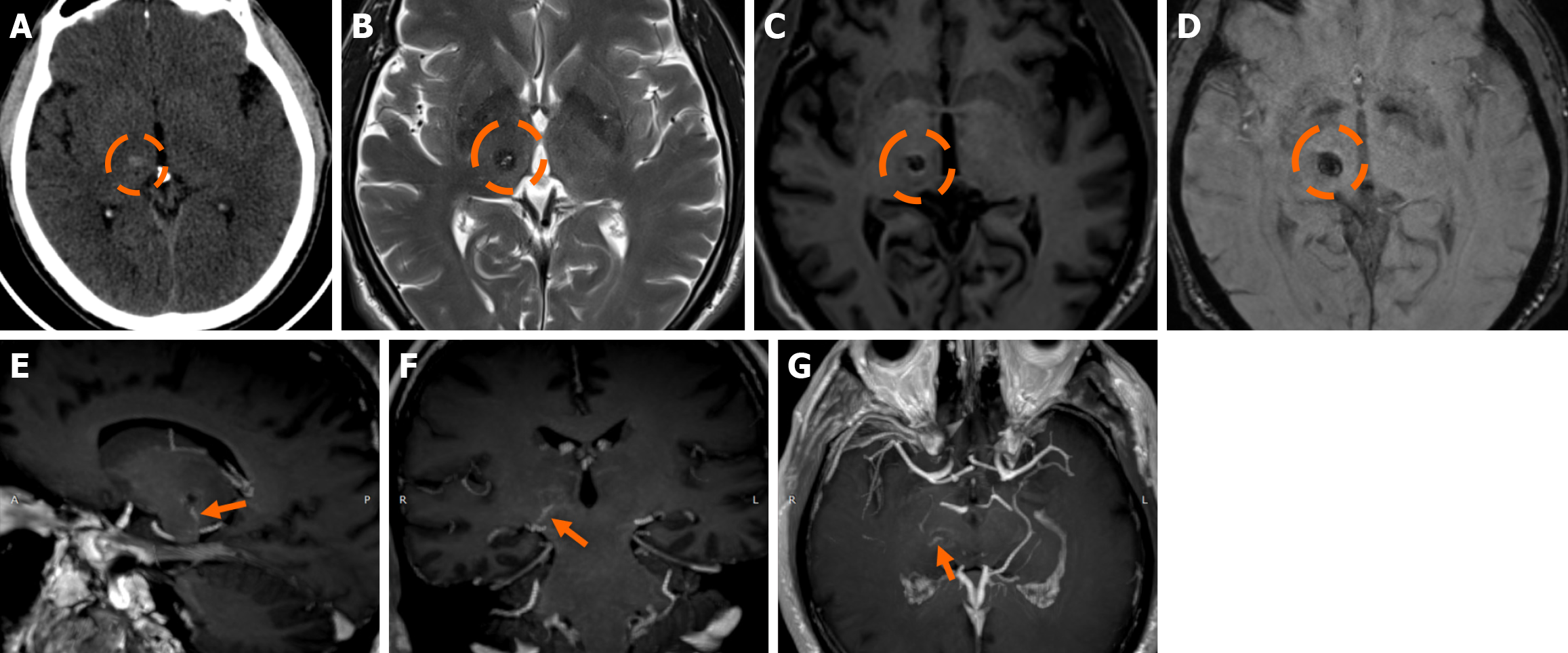

Figure 3 Developmental venous anomaly image.

A and B: T1-weighted axial (A) and coronal (B) images following intravenous gadolinium administration demonstrate a developmental venous anomaly in the left temporal lobe, evident by the characteristic “caput medusae” appearance and the draining vein (dashed circle); C and D: When compared to the contralateral side, dynamic susceptibility contrast magnetic resonance perfusion demonstrates increased relative cerebral blood volume (C), and arterial spin-labeling perfusion displays increased relative cerebral blood flow (D) (dashed oval) in the corresponding territory of the developmental venous anomaly.

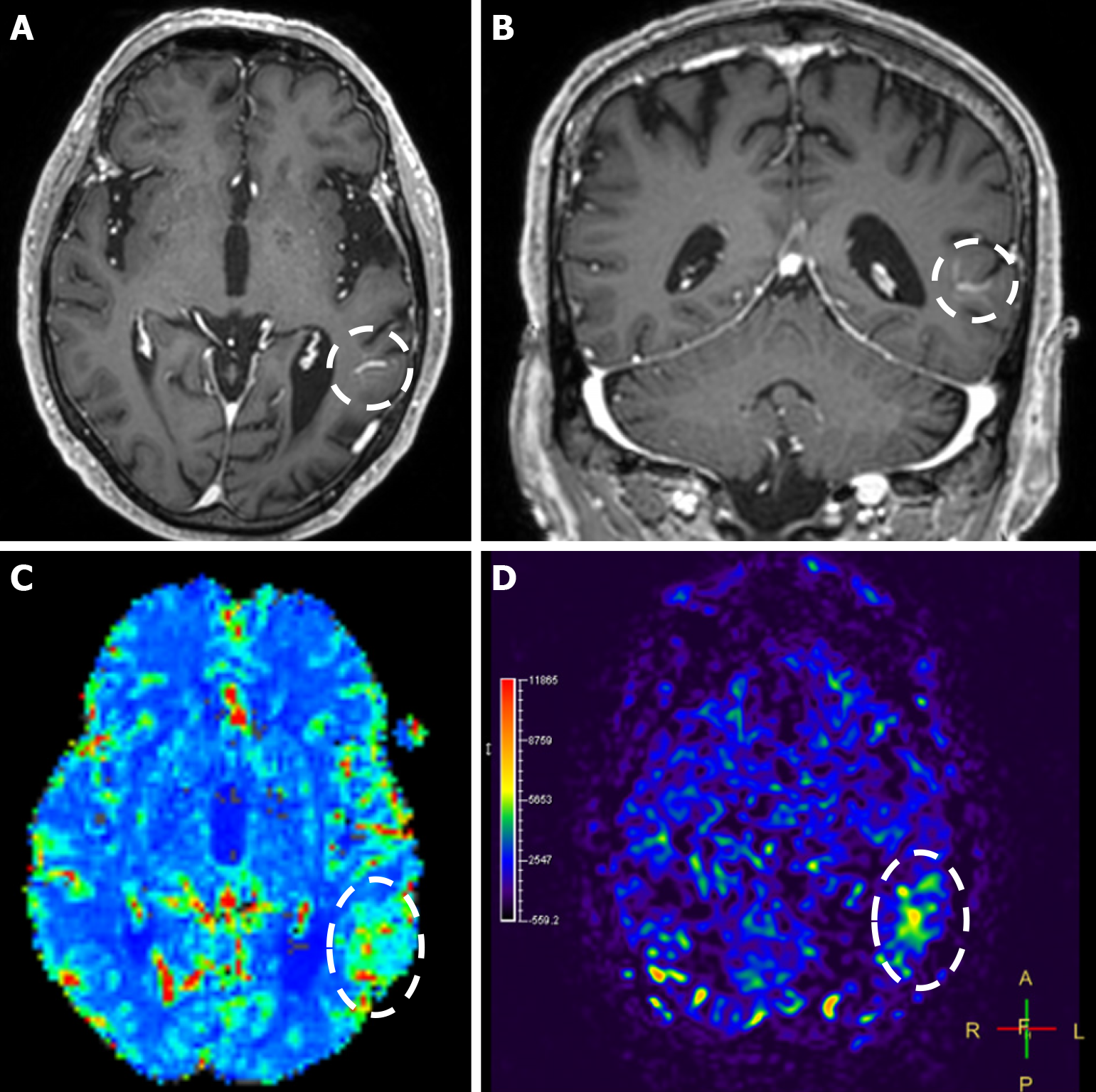

Figure 4 Cerebral cavernous malformation.

A: Computed tomography scan performed in a 65-year-old woman due to memory deficits displayed a mildly hyperdense lesion in the right parietal lobe (dashed circle), which raised suspicion for a hemorrhage; B and C: On the subsequent magnetic resonance imaging examination performed, the lesion (dashed circle) was hypointense on T1-weighted images (B), without significant or discernible contrast enhancement following intravenous gadolinium administration (C); D: On T2-weighted images, the lesion (dashed circle) displays a heterogeneously hyperintense center with a low signal periphery (arrows) compatible with a hemosiderin rim; E: Susceptibility-weighted imaging shows intense blooming of the lesion (dashed circle). The findings were consistent with a cerebral cavernous malformation diagnosis.

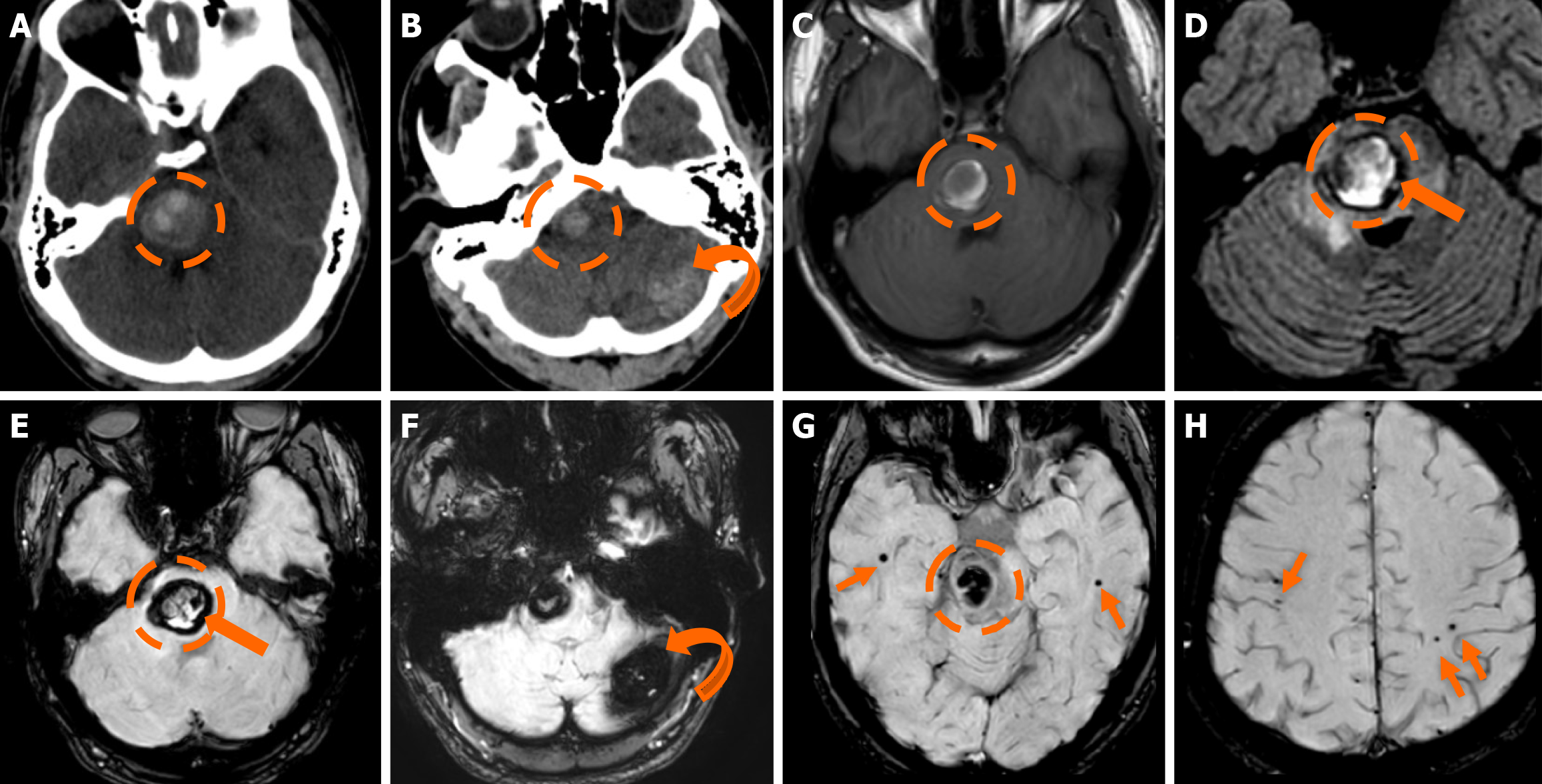

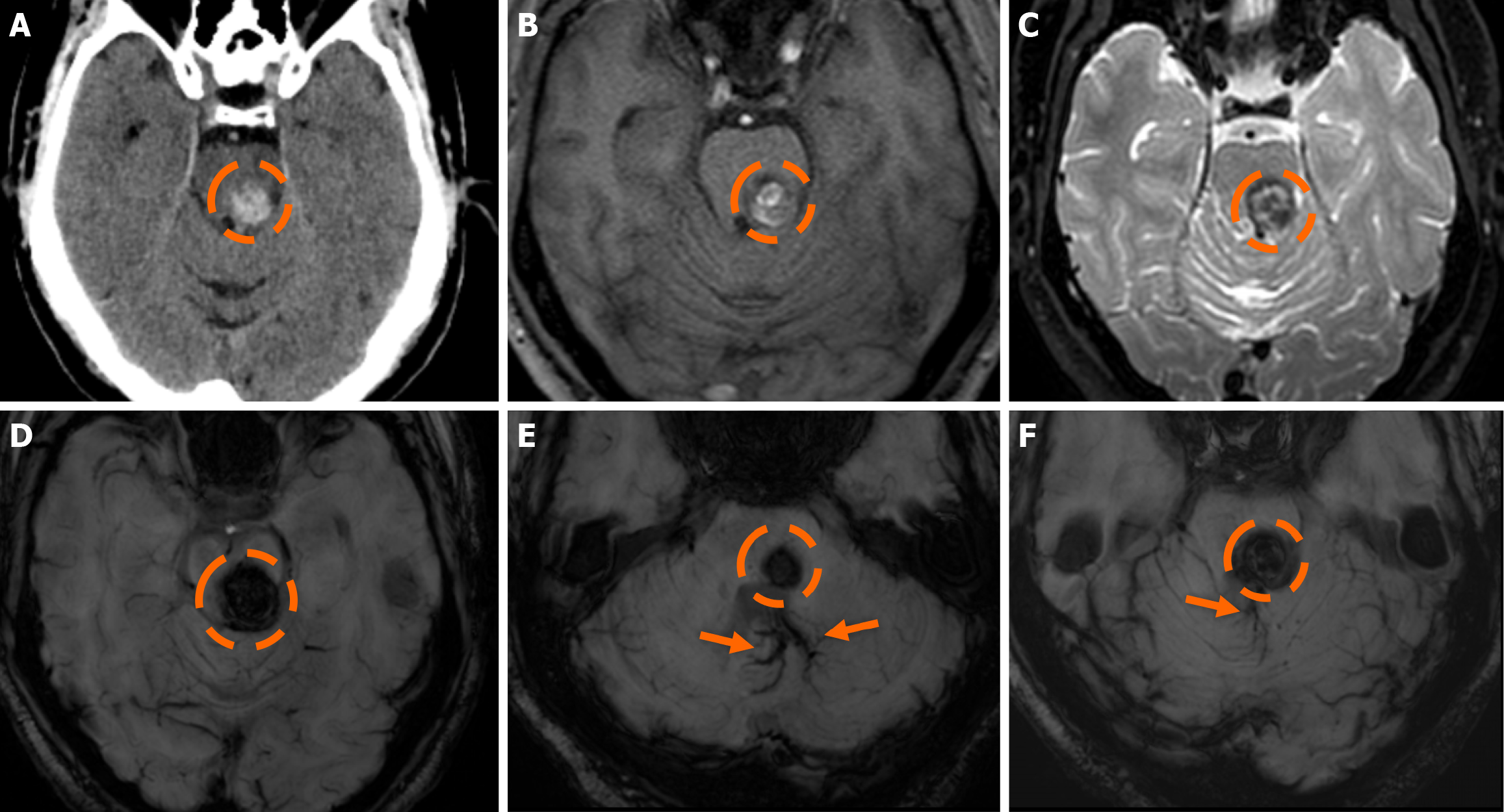

Figure 5 Familial cerebral cavernous malformation syndrome.

A and B: Computed tomography scan performed due to an acute onset headache in a 25-year-old man displayed a heterogeneously hyperdense hemorrhagic lesion in the pons (dashed circle) and an additional mildly hyperdense lesion in the left cerebellar hemisphere (curved arrow); C and D: On the subsequent magnetic resonance imaging examination performed, the pontine lesion (dashed circle) displays a hyperintense signal on T1-weighted (C) and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images (D) with a low-signal hemosiderin rim (thick arrow); D: Also note the hyperintense signal intensity surrounding the pontine lesion due to vasogenic edema; E-H: Susceptibility-weighted imaging verify the hemosiderin presence and rim (thick arrow) in the pontine lesion (dashed circle) and also display hemosiderin presence with blooming in the left cerebellar hemisphere lesion (curved arrow). Several additional bilateral hemispheric microbleeds are also noted on the susceptibility-weighted images (thin arrows). The findings are suggestive of a Zabramski type I cerebral cavernous malformation (CM) in the pons as indicated by the recent bleed (T1 central hyperintensity) and the surrounding vasogenic edema. The left cerebellar hemispheric lesion represented a Zabramski type II cerebral CM (hemosiderin rim; “popcorn” appearance; blooming; no evidence of recent bleed on the remaining examination). In this setting, the additional bilateral cerebral hemispheric lesions most likely represent Zabramski type IV cerebral CM. The constellation of all the above findings is highly suspicious for familial cerebral CM syndrome.

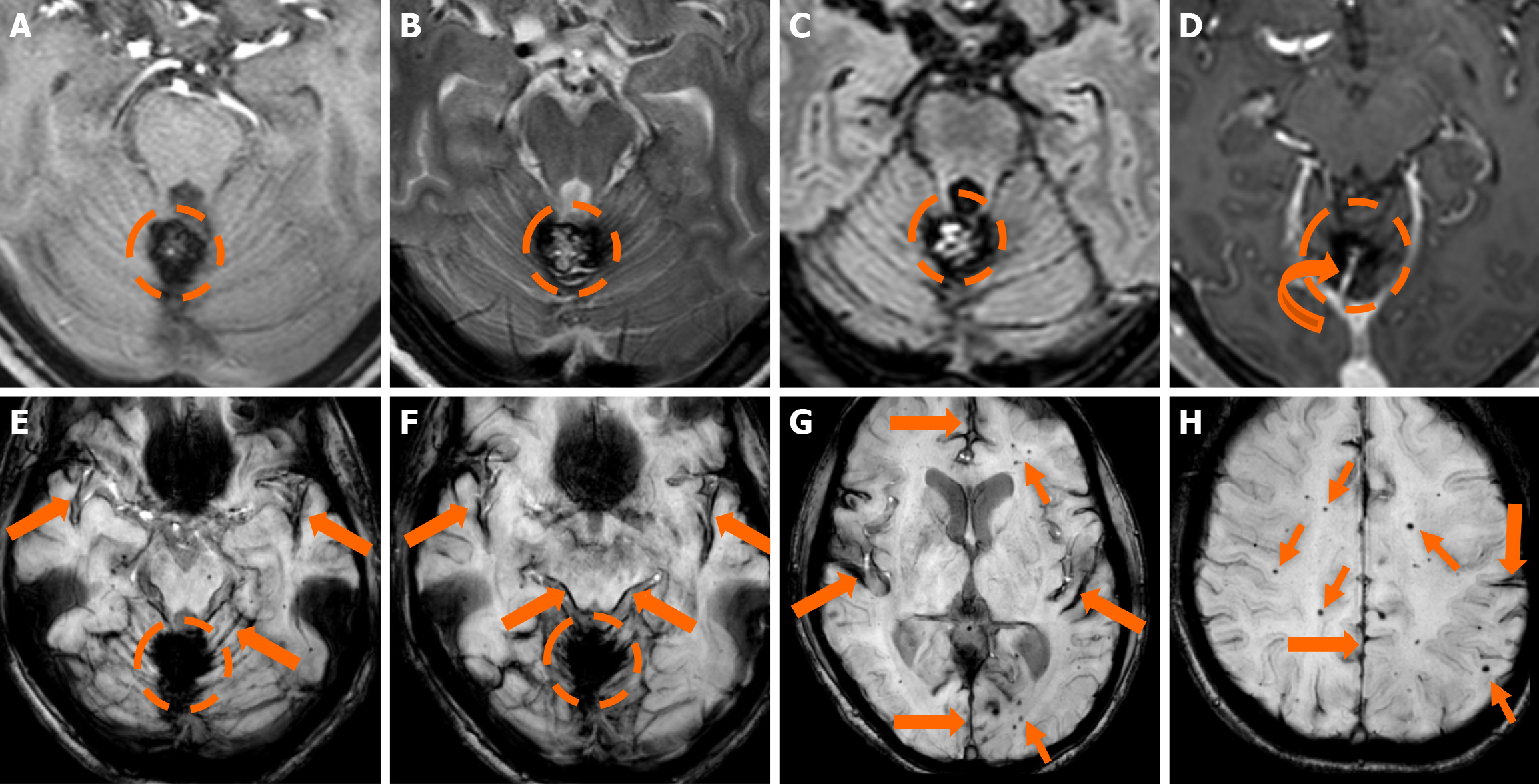

Figure 6 Familial cerebral cavernous malformation syndrome.

Magnetic resonance imaging examination performed due to dizziness in a 50-year-old woman. A-C: A lesion (dashed circle) centered between the cerebellar hemispheres and the scolex is demonstrated. The lesion displays a heterogeneous signal with a few areas of increased signal intensity centrally on T1-weighted images (A), while on T2-weighted (B) and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (C) images it demonstrates a characteristic “popcorn” appearance with a heterogeneous signal centrally and a low signal hemosiderin rim peripherally; D: T1-weighted axial image following intravenous gadolinium administration demonstrates no discernible enhancement and an ectopic draining vein (curved arrow); E-H: Susceptibility-weighted images verify the hemosiderin presence of the lesion. The findings are suggestive of a Zabramski type II cerebral cavernous malformation with a concomitant developmental venous anomaly (ectopic draining vein) (curved arrow). In addition, susceptibility-weighted images display hemosiderin deposition in the cortical surfaces of the cerebellar and cerebral hemisphere, the pons and midbrain (thick arrows), suggesting superficial siderosis from a prior hemorrhage with subarachnoid extension. Multiple bilateral microbleeds (thin arrows) are also noted, suggesting a diagnosis of familial cerebral cavernous malformation syndrome.

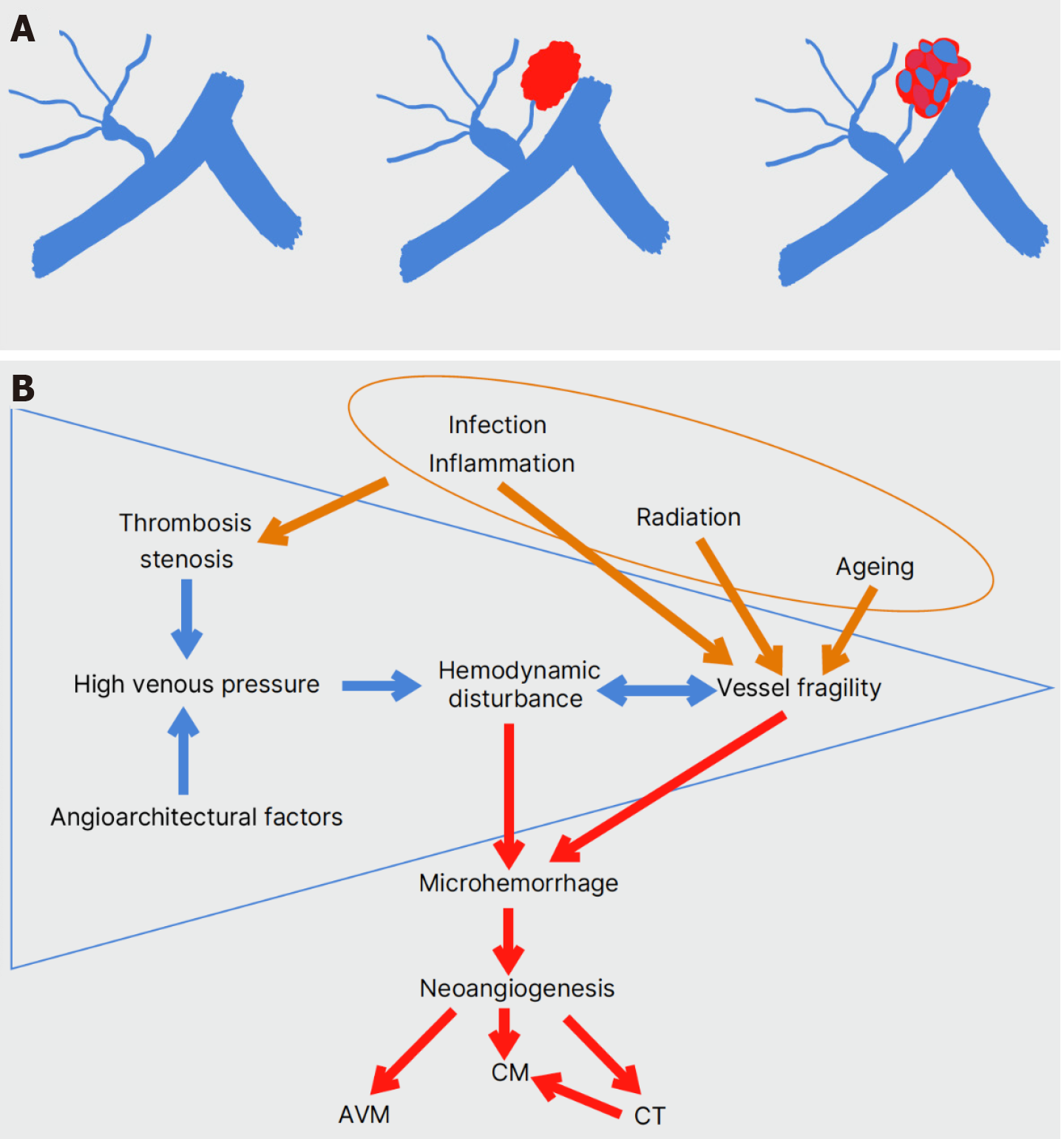

Figure 7 De novo formation of a developmental venous anomaly-associated sporadic cavernous malformation.

A: Events of temporary or permanent high venous pressure in a developmental venous anomaly (DVA) may induce hemodynamic instability and vessel fragility, leading to microhemorrhage in the adjacent parenchyma. The attraction of proliferative angiogenic factors can eventually lead to the formation of a sporadic cavernous malformation sharing the DVA’s venous drainage system; B: Thrombosis and stenosis or/and the presence of favoring angioarchitectural factors raise venous pressure within the DVA (blue arrows). The resulting hemodynamic disturbance and turbulent flow may affect the rigidity of venous walls, leading to microhemorrhage. Neoangiogenesis in the vicinity of the DVA produces new vascular malformations of a broad histologic spectrum, mainly cavernous malformations (red arrows). Environmental factors such as radiation therapy, inflammatory and infectious agents, and aging may also be associated with DVA thrombosis and increased vessel fragility (brown arrows).

Figure 8 Cerebral cavernous malformation and developmental venous anomaly.

A: Non-contrast computed tomography scan of a 40-year-old man presenting to the emergency department with an acute onset headache demonstrated a hyperdense-hemorrhagic lesion (dashed circle) in the right middle cerebellar peduncle, abutting the 4th ventricle; no contrast enhancement was shown. There was no relevant medical history or additional lesions; B and C: Magnetic resonance imaging examination performed a few days later demonstrates a central hyperintense signal intensity in T1-weighted images (B) and hyperintense signal centrally with a low signal hemosiderin rim on T2-weighted images (C), mild surrounding vasogenic edema was also noted on T2-weighted images. The findings were mostly suspicious of a Zabramski type I cerebral cavernous malformation with recent bleeding (T1 hyperintensity and mild surrounding vasogenic edema); D: On sus

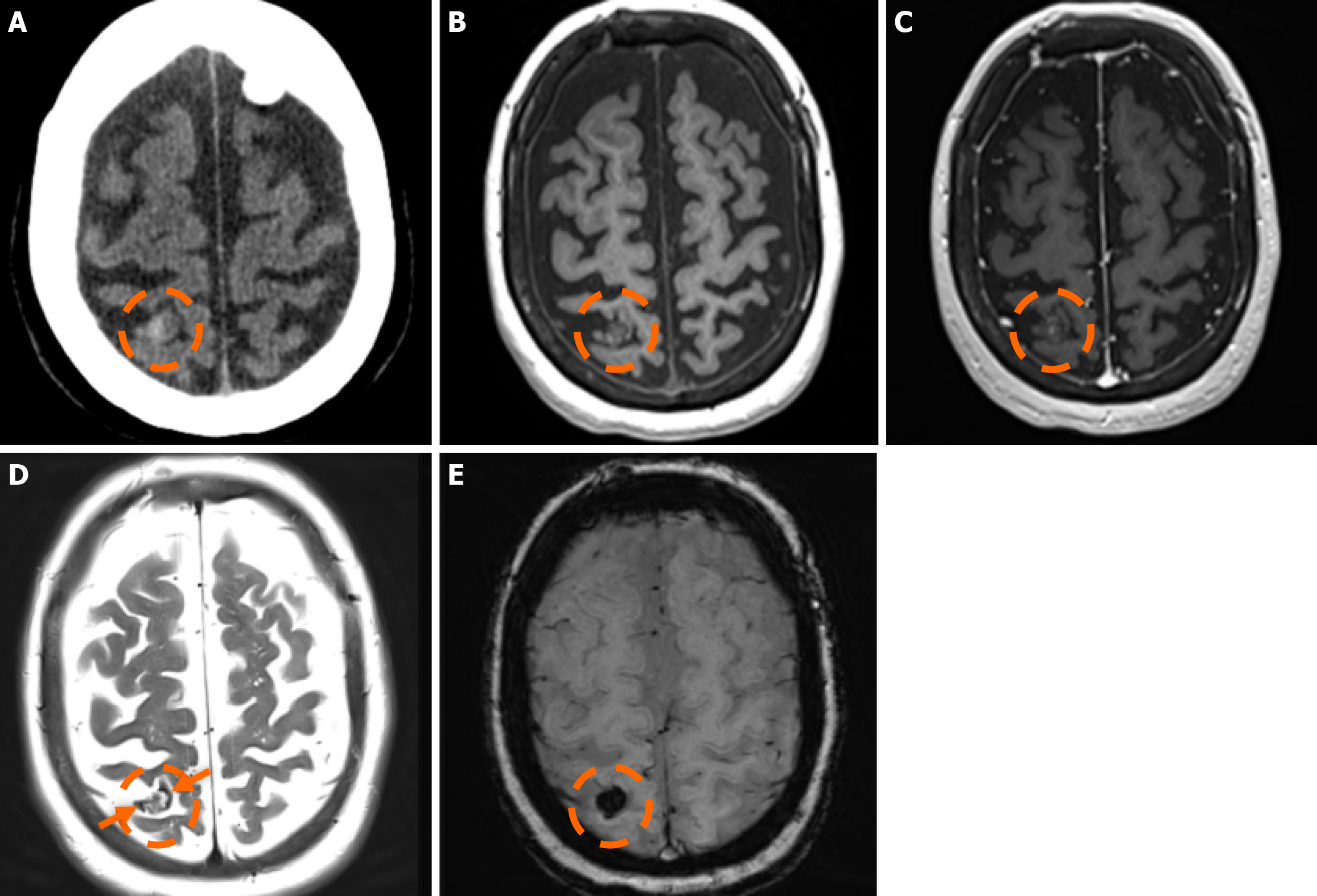

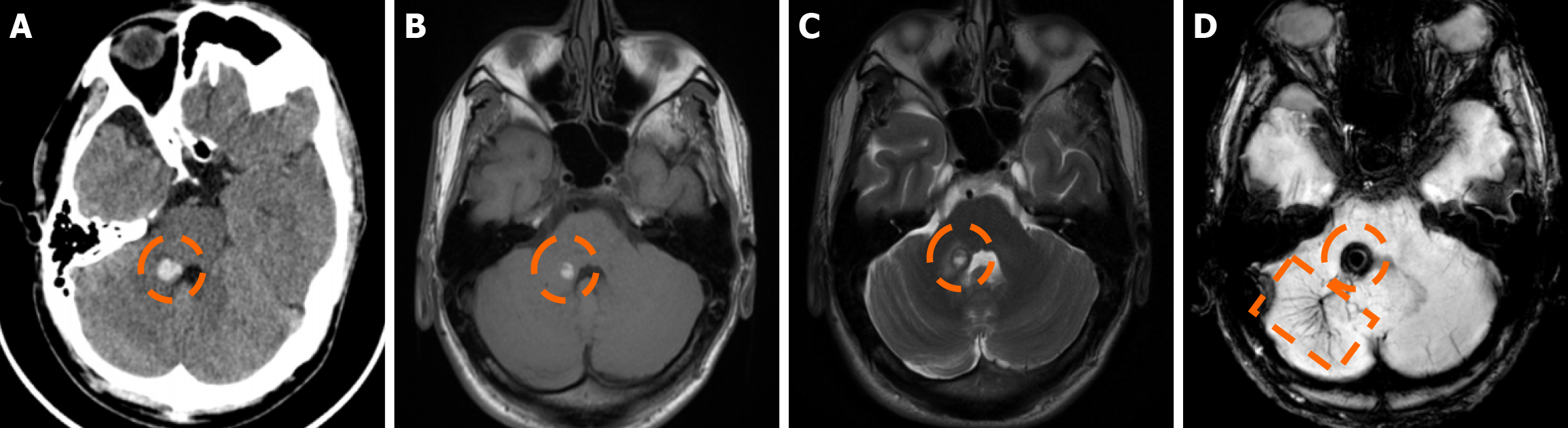

Figure 9 Cerebral cavernous malformation and developmental venous anomaly.

A: Non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography in a 60-year-old man presenting to the emergency department due to dizziness and a medical history of arterial hypertension. A mildly hyperdense lesion was depicted in the right thalamus (dashed circle). Considering the location of the lesion and the medical history of arterial hypertension, it was suspicious of a hypertensive bleed. The lesion remained unchanged in follow-up computed tomography examinations, and therefore, further magnetic resonance imaging was decided; B: On T2-weighted images, the lesion displayed heterogeneous signal intensity centrally with a “popcorn-like” appearance and a peripheral low-signal hemosiderin rim; C: On T1-weighted images, heterogeneous, mostly hypointense, signal was noted centrally with mildly increased T1 signal in the periphery; D: On susceptibility-weighted imaging, the lesion displayed intense blooming. The findings were suggestive of a Zabramski type II cerebral cavernous malformation rather than a hypertensive bleed; E-G: This scenario was further validated by the depiction of an adjacent ectopic draining vein (arrows) on T1-weighted sagittal (E), coronal (F) and axial (G) maximum intensity projection reconstructions following intravenous gadolinium administration, thus indicating the concomitant presence of a developmental venous anomaly.

Figure 10 Cerebral cavernous malformation and developmental venous anomaly.

A: Non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography obtained in a 67-year-old man presenting to the emergency department due to impaired balance shows a hyperdense lesion in the pons (dashed circle); B and C: On T1-weighted images the lesion displays a heterogeneous but mostly hyperintense signal, suggesting recent hemorrhage (B), while on T2-weighted images (C), a peripheral low-signal hemosiderin rim is noted, and a “popcorn-like” or “mulberry-like” appearance is depicted centrally; D-F: On susceptibility-weighted imaging, the lesion displayed intense blooming. The findings were mostly suggestive of a cerebral cavernous malformation (Zabramski type I or II, due to mixed findings of a “popcorn” appearance and recent bleed) as the underlying diagnosis, which was further verified by the depiction of a large adjacent developmental venous anomaly (arrows).

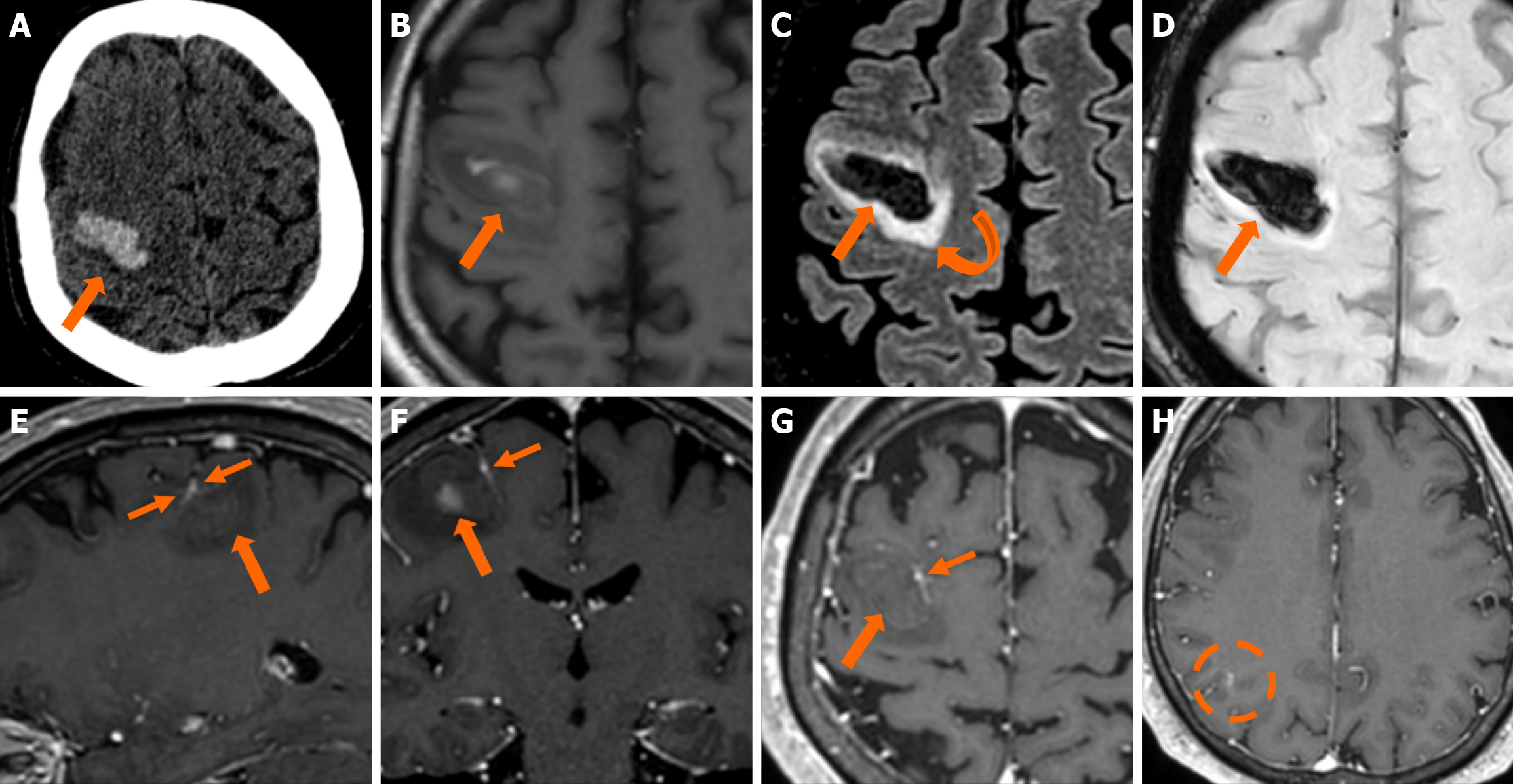

Figure 11 Cerebral cavernous malformation and developmental venous anomaly.

A: Non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography obtained in a 56-year-old man presenting to the emergency department with left-hand weakness shows an intracerebral hematoma in the right frontal lobe (thick arrow). The etiology remained unclear, as no helpful findings were depicted in the computed tomography angiography and venography study performed (not shown); B: On T1-weighted images, the hematoma displays a heterogeneous hyperintense signal due to the recent hemorrhage; C: On fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images, mild surrounding vasogenic edema is also noted (curved arrow); D: Hemosiderin presence is also verified on susceptibility-weighted imaging; E-G: On T1-weighted images sagittal (E), coronal (F) and axial (G) reconstructions following intravenous gadolinium administration, an ectopic vein with “caput medusae” morphology is noted immediately adjacent to the internal border of the hematoma (thin arrows), indicating the presence of a developmental venous anomaly and thus pointing towards an underlying recently bled cerebral cavernous malformation as the underlying etiology for the hematoma; H: An additional developmental venous anomaly was also noted on the same side in a more posterior location (dashed circle).

- Citation: Arkoudis NA, Siderakis M, Tsetsou I, Efthymiou E, Triantafyllou G, Chalmoukis D, Karachaliou A, Papadopoulos A, Prountzos S, Moschovaki-Zeiger O, Gouliopoulos N, Papakonstantinou O, Filippiadis D, Velonakis G. Developmental venous anomalies and cerebral cavernous malformations: Partners in crime. World J Radiol 2025; 17(12): 114595

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v17/i12/114595.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v17.i12.114595