Published online Feb 26, 2026. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.114561

Revised: October 15, 2025

Accepted: December 18, 2025

Published online: February 26, 2026

Processing time: 139 Days and 18.2 Hours

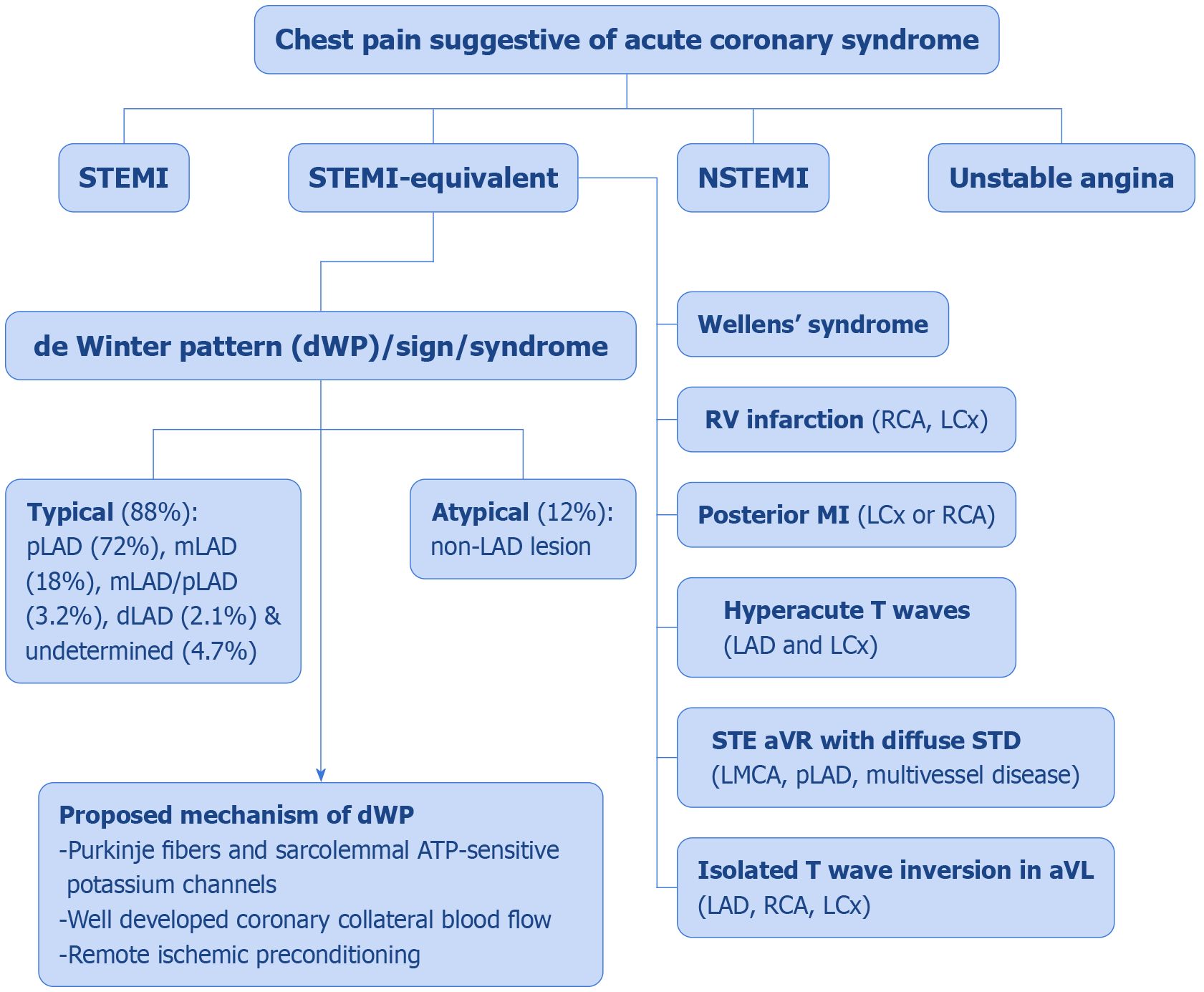

The de Winter (dW) pattern, sign, and syndrome is an ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) equivalent. The first two forms describe the electrocardiographic characteristics of this phenomenon, while dW syndrome additionally has symptoms indicative of acute coronary syndrome. Emerging evidence suggests that dW pattern precedes or alternates with STEMI patterns.

To improve the recognition of the dW pattern, dW sign, or dW syndrome, urge early aggressive treatment, and determine whether sex matters, by integrating contemporary knowledge through a systematic scoping review and data analysis.

A comprehensive search was conducted across PubMed/MEDLINE and Google Scholar (November 2008 to June 2025), and literature data were analyzed. This scoping review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews checklist.

A total of 322 patients presenting with dW pattern were identified. Most patients were young males. Risk factors were primarily smoking, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. Sixteen cardiac arrest events occurred during hospitalization. The main culprit vessel was the left anterior descending artery (LAD) at 88.5%. Compared with the younger group, older patients had more LAD (84% vs 80%) and right coronary artery involvement (4% vs 1.0%). Left main coronary artery occlusion was more prevalent in the younger group (5.0% vs 2.4%). The frequency of total or near-occlusion of LAD and left main coronary artery was similar in the two age groups. Males showed a higher rate of severe LAD stenosis than females did (45.2% vs 17.7%). dW pattern followed by STEMI was noted in 40 cases, STEMI followed by dW pattern in 8 cases, and simultaneous STEMI and dW pattern in 10 cases. The overall mortality rate was 3%.

dW pattern, dW sign, and dW syndrome are commonly used interchangeably describing the dW phenomenon. Patients presenting with this phenomenon have unique demographics, risk factors, pathophysiology, and angiographic characteristics (i.e., distinct culprit lesions and coronary artery involvement). Early identification with a high index of suspicion is crucial and necessitates urgent intervention.

Core Tip: The three forms of the de Winter (dW) phenomenon (dW pattern, dW sign, or syndrome) are used similarly in contemporary literature. This phenomenon has unique risk factors, pathophysiology, and angiographic characteristics. It should be managed as an indicator of ST-elevation myocardial infarction equivalent that requires urgent intervention. However, it is often underrecognized and therefore requires a high index of suspicion. Age and gender are associated with distinct culprit lesions and coronary artery involvement in this phenomenon. By integrating current evidence, prompt recognition and aggressive reperfusion strategies, such as those used in ST-elevation myocardial infarction protocols, are crucial for improving outcomes in this high-risk presentation.

- Citation: Elmenyar E, Abbara MA, Al-Ghoul Z, Al Mahmeed W, Cander B, Abdelrahman AS, Al-Thani H, El-Menyar A. Phenomenon of “de Winter” pattern, sign, or syndrome: A systematic scoping review and data analysis. World J Cardiol 2026; 18(2): 114561

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v18/i2/114561.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.114561

The de Winter (dW) pattern and “sign” indicate unique electrocardiographic (ECG) findings of the dW phenomenon, while dW syndrome additionally has symptoms indicative of acute coronary syndrome (ACS)[1]. Although dW pattern, dW sign, and dW syndrome are commonly used interchangeably in the literature, dW syndrome is preferable as it reflects the practical utility of this phenomenon and integrates ECG and clinical findings. In 1955, Pruitt described junctional ST-depression with tall symmetrical T waves in leads V3-V5 in a patient presenting with severe chest pain. In 2008, de Winter et al[1] revealed that an occlusion in the proximal left anterior descending (pLAD) coronary artery can occur in the absence of a clear ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) that was reported in 2% of anterior acute myocardial infarction (AMI)[2]. The ECG findings in dW pattern patients were obtained, on average, within 1.5 hours of symptom onset and were static[1]. In dW pattern, the ST segment displays a 1 mm to 3 mm upsloping depression at the J point in leads V1-V6, typically in V1-V4, which then progresses to tall, positive, symmetrical T waves[1].

When dW pattern is suspected, it should be considered a time-critical condition that requires treatment similar to that for STEMI, including coronary angiography (CAG) and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)[3]. If PCI is unavailable, then thrombolytic therapy can be administered if there are no contraindications[4]. Several reports have shown that dW pattern may be transient and subject to dynamic fluctuations, requiring serial ECG monitoring. The underlying risk factors of dW pattern are similar to those of ACS, and chest pain is the most common presenting symptom[5].

This review aims to integrate and evaluate the existing literature on the dW phenomenon, focusing on its up-to-date pathophysiology, diagnostic approaches, angiographic findings, treatment, and outcomes. By systematically reviewing and analyzing data from diverse studies, we will assess the clinical characteristics of dW pattern in males and females, define areas of uncertainty, and provide actionable recommendations for clinicians and researchers. Ultimately, this work would enhance understanding of the dW pattern and improve patient care through evidence-based recommendations.

The primary objective of this review is to investigate the prevalence, pathophysiology, ECG, and angiographic findings of dW pattern in males and females. It also aims to evaluate the pharmacological and interventional treatment and assess the clinical outcomes. This review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews checklist.

A systematic scoping review of peer-reviewed articles published between November 2008 and June 2025 was carried out. Additionally, an analysis of the selected data was conducted. A thorough search was performed using medical terms and combinations such as the following: “de Winter sign” OR “de Winter pattern” OR “de Winter electrocardiographic pattern” OR “de Winter syndrome” OR “STEMI equivalent” across databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, and Medical Subject Headings on the PubMed search engine. We also searched further among articles that fit the inclusion criteria, which were retrieved and included in the data.

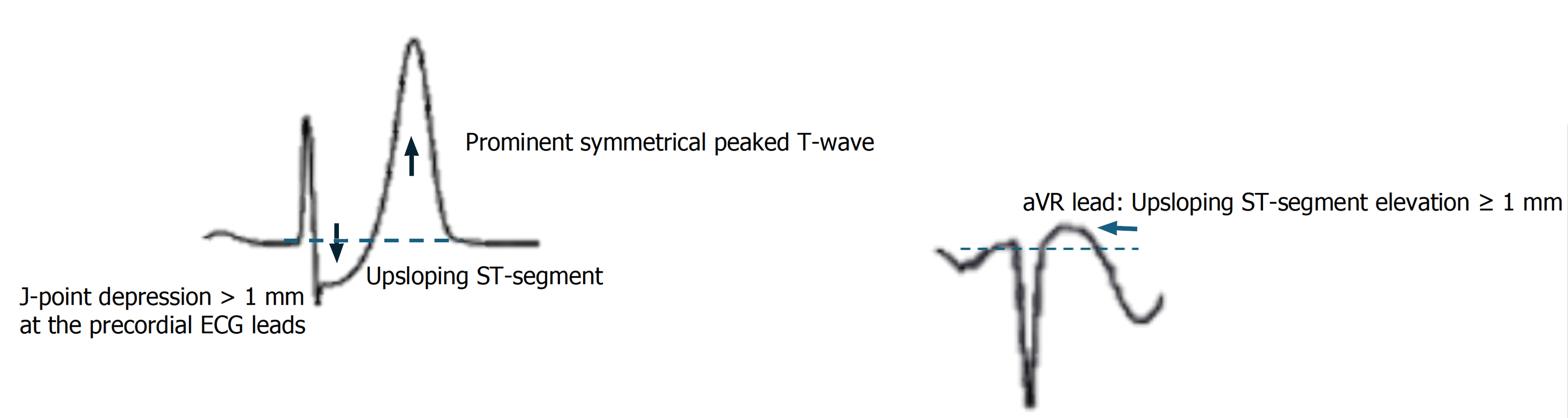

dW pattern or dW sign: The ECG findings suggestive of dW pattern are: (1) A 1-3 mm upsloping ST-segment depression (STD) at the J point in the precordial leads V1-V6; (2) Tall, symmetric peaked T waves; (3) A normal or mildly prolonged QRS complex; (4) Poor R wave progression; and (5) Mild ST-segment elevation in lead augmented vector right (aVR) of > 0.5 mm (Figure 1)[1].

The dW syndrome: dW syndrome describes dW pattern or signs and symptoms suggestive of ACS, along with coronary angiographic findings. Most of the literature used the terms “dW pattern” and “dW syndrome” without a distinguishable definition.

Eligibility criteria: Eligible studies were identified by conducting a comprehensive search strategy using keywords and text words that highlighted diagnostics, interventions, and treatment options.

Inclusion criteria: Data included prospective, retrospective, case reports, and case series. Abstracts that include full pertinent details can be included. All age groups, genders, and different forms of presentation were included.

Exclusion criteria: Articles written in languages other than English were excluded, unless the abstract was written in English and contained all the required information, and cases of ACS without the characteristics of dW pattern. We also excluded systematic reviews and meta-analyses in which relevant individual cases were not identified or data were missing.

Information sources and search methods: A comprehensive search was conducted across electronic databases, including PubMed/MEDLINE and Google Scholar, between November 2008 and June 2025.

Study selection: A systematic search was conducted using specific keywords.

Data collection process: A thorough manual search of eligible articles was conducted, and any duplicates were removed. Elmenyar E, Abbara MA, and Al-Ghoul Z independently searched, screened, and extracted the articles; all reached a consensus on eligibility, and the senior author reviewed the articles. The obtained information was categorized within tables that included the author(s), number of cases per article, gender, mean age, medical history, risk factors, presen

Risk of bias assessment at the individual and across-studies levels: The risk of bias assessment was not applicable, as all cases were collected from case reports, case series, and retrospective studies. However, the risk could generally be low. No structured, large-scale, prospective studies, or randomized controlled trials addressed the subject of this review.

Data were presented as n (%), means ± SD, and medians (interquartile ranges) as applicable. Age (cut-off at 55 years) and sex (males vs females) were analyzed. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test, while Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables. Statistical analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 21.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

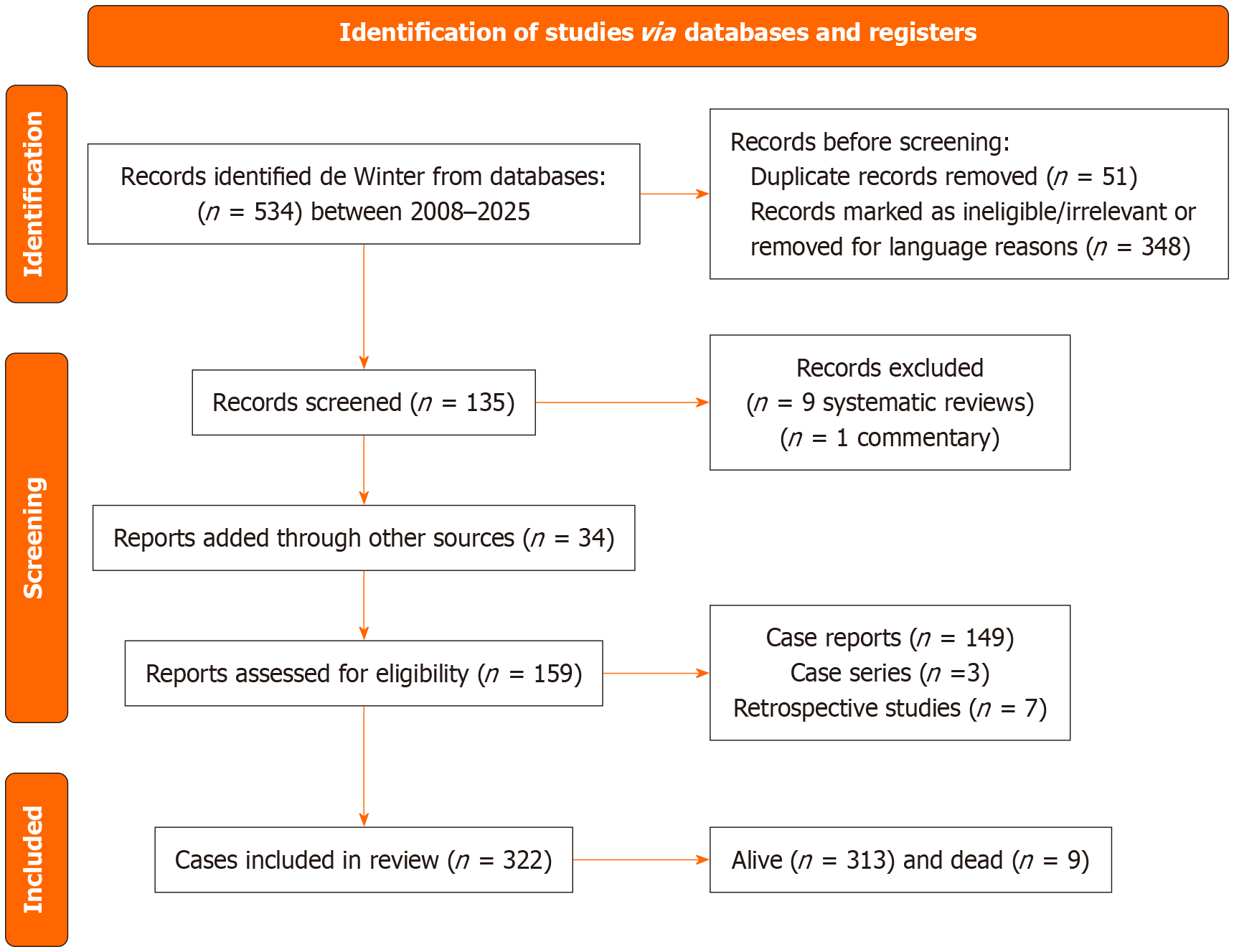

A total of 322 patients presenting with dW pattern on ECG were retrieved from 159 papers (Figure 2). Three articles (n = 22) were case series[6-8], 149 articles (n = 165) were case reports, and seven articles were retrospective studies[1,2,9-13]. Table 1 shows case series and retrospective studies.

| Ref. | Years | Study characteristics | Comments |

| de Winter et al[1] | 2008 | Retrospective; 30/1532 AMI (2%); mean age (52 years); male (94%) | (1) 76% isolated LAD disease; (2) Culprit pLAD, PCI done; (3) Wrap-around LAD (50%); and (4) Static status1: One died (3%) |

| Verouden et al[2] | 2009 | Retrospective; 35/1855 PCI of LAD | (1) Wrap-around LAD (57%); and (2) 67% had SVD |

| Xu et al[9] | 2018 | Retrospective; 15/449 AMI (3.4%); mean age (60 years); male (87%) | (1) 11/15 underwent PCI, 2 underwent successful thrombolysis, and 2 received conservative therapy; and (2) LAD was the culprit in 9 |

| Shahri et al[6] | 2022 | Case series; 11 with dW pattern; mean age (56 years); male (54%) | (1) The culprit vessel is LAD; and (2) 5 MVD |

| de Winter et al[10] | 2019 | Retrospective; 11/701 AMI (1.6%); mean age (65 years); male 91% | (1) Culprit pLAD or mLAD; and (2) PCI not in a timely fashion; 3 died (27%) |

| Fuji and Ikari[12] | 2024 | Retrospective; 2/641 ACS; mean age (69 years); male (100%) | (1) Culprit LAD; and (2) 1 patient received PCI and 1 underwent CABG |

| Tang et al[13] | 2024 | Retrospective; 12/1865 AMI; mean age (49 years); male (100%) | (1) The culprit vessel was pLAD in 7 and mLAD in 3, LMCA in 1, and 1 in the ramus intermedius artery; (2) 53% had MVD; (3) 3 developed cardiogenic shock; and (4) The median door-to-balloon time was 94.5 minutes |

| Alireza et al[11] | 2025 | Retrospective; 30/967 AMI; mean age (61 years); male (67%) | (1) Culprit pLAD treated with PCI within 90 minutes of arrival (100%); (2) Wrap-around LAD (67%); (3) MVD (60%); and (4) Mortality 3% |

| Chyu et al[7] | 2022 | Case series; 4 had STEMI equivalent, 1/4 with dW pattern | Total occlusion of LAD after the first septal branch treated with PCI |

| Ni[8] | 2022 | Case series of 10 patients (9 males) | All showed dynamic evolution (the explanation was unclear, as no full text was available) 9 had PCI |

The median age was 52 years, with an interquartile range of (42-62). Most patients presented with chest pain and tightness (82%) and shock or hemodynamic instability (5.2%). The main risk factors included smoking (50%), hypertension (32%), dyslipidemia (30%), diabetes mellitus (17.5%), and family history of ACS (16.8%). The median and interquartile range of the left ventricle ejection fraction were 45% (38-50). Positive troponin and creatine kinase myocardial band rates were 60% and 22%, respectively. Patients with dW pattern were divided into two age groups

| Variables | < 55 years old (55%) | ≥ 55 years old (45%) |

| Positive troponin | 55.0% | 44.0% |

| Mortality | 1.9% | 3.7% |

| Cardiac arrest | 6.8% | 4.9% |

| Severe LAD stenosis | 42.7% | 44.7% |

| Severe LCx | 4.8% | 7.3% |

| Severe RCA | 2.9% | 8.5% |

| Severe LMCA | 4.9% | 4.8% |

| Severe: ≥ 70% stenosis | ||

The male sex predominated (89%). Females had no culprit lesions in the LMCA or RCA unlike males. The prevalence of LAD as the culprit vessel was similar in females and males (82%). However, females showed a higher rate of culprit left circumflex (LCx) artery than males did (6% vs 3%). Total occlusion and near-occlusion of LAD were higher in males than in females (45.2 vs 17.7%).

The most common transformative ECG changes were STEMI[14-17], at 32.3%, of which 3.8% presented first with STEMI, then dW pattern[18-21], and 4.6% exhibited a precordial continuum of both patterns[22-25]. dW pattern followed by STEMI was noted in 40 cases, while STEMI followed by dW pattern was reported in 8 cases. STEMI following PCI for dW pattern was reported in 7 cases, STEMI following thrombolysis for dW pattern in 4 cases, and concomitant STEMI and dW pattern in 10 cases.

Wellens’ ECG pattern was observed in 5.3%[26-35]. Two cases reported the coexistence of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome with dW pattern[36,37]. Five patients had bundle branch block, and six patients had atrial arrhythmia.

In CAG, LAD was the culprit vessel in 277 patients (88%), with lesions located in the proximal region in 226 (72%), while 16 had no documentation beyond the ECG description. The other culprit vessels included LMCA (4.5%), diagonal branches (4.2%), LCx, and RCA (3.2% equally), and one case had an obtuse marginal (OM) artery and ramus intermedius stenosis[13]. The predominant site of occlusion within the LCx was the proximal region (10%). RCA stenosis was found in the proximal (5.3%) and middle segments (4.8%).

The medications used were dual antiplatelet therapy (38.8%), anticoagulant agents (19.6%), and nitroglycerin (15.3%). The overall use of thrombolytic treatment was 13%, Nineteen patients had efficient thrombolysis therapy, nine patients underwent PCI after stabilization, one underwent coronary artery bypass grafting, and the rest were safely discharged without further intervention. The following agents were used: Fibrin-specific tissue plasminogen activator (4.3%), streptokinase (4.7%), and prourokinase (1%). In four cases, the type of agent used was not specified. Three cases under

This work is an up-to-date, comprehensive review that includes 322 patients presenting with dW phenomenon in terms of dW pattern, dW sign, or dW syndrome. This review highlights the importance of the ECG recognition checklist, key differentials, management priorities, and pitfalls in diagnosing the dW phenomenon. A prior review on the same topic was published in 2024, including 66 patients with a limited analysis[40]. dW pattern was reported in 3.4% of patients with AMI, with a positive predictive value (PPV) of 95% to 100% for identifying an acute occlusion of the pLAD[9,41,42]. A subsequent study reported PPVs of 50% to 85.7% for dW pattern in predicting LAD occlusion[42]. However, the accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of dW pattern for predicting the angiographic findings cannot be confidently obtained until well-designed large studies have been conducted. Early identification of STEMI-equivalent conditions, including dW pattern, is crucial for ensuring timely intervention, limiting infarct size and myocardial necrosis, reducing arrhythmias, and improving patient survival. Notably, dW pattern is easily misdiagnosed and needs a high index of suspicion.

The dW phenomenon is more prevalent in males, with a mean age of 52 and a mortality rate of 3% during the index admission[2,10,11,17,43,44]. However, this rate could be underestimated. Diabetes mellitus, unlike other STEMI, is not among the top three risk factors. Moreover, 7.8% sustained cardiac arrest during early hospitalization. Notably, among the 16 cardiac arrest cases, seven exhibited dynamic ECG changes (Table 3)[4,11,13,22,45-54]. Around 9% of dW syndrome patients had threatening ventricular arrhythmia. This prevalence of arrhythmia is similar to what has been reported in patients with STEMI[55].

| Ref. | Years | Comment | Outcome |

| Ghazali et al[4] | 2020 | Chest pain > > dW pattern followed by cardiac arrest > > STEMI | Survived |

| Tomcsányi et al[22] | 2022 | Chest pain > > simultaneous dW pattern and STE > cardiac arrest > > Stenting | Survived |

| Missaoui et al[45] | 2020 | Chest pain > > dW pattern with STE aVR > > thrombolytic agent > > > cardiac arrest > > stenting | Survived |

| John et al[46] | 2020 | Chest pain > > dW pattern > > STEMI > > cardiac arrest > > PCI | Survived |

| Fernandez-Vega et al[47] | 2017 | Cardiac arrest > > dW pattern > > PCI | Survived |

| Carr et al[48] | 2016 | Chest pain > > STD > > ECG normalization > > cardiac arrest > > dW pattern > > PCI | Survived |

| Alhatemi et al[49] | 2024 | Chest pain > > hyperacute T waves > > cardiac arrest > > dW pattern > > PCI | Survived |

| Wismiyarso et al[50] | 2021 | Chest pain > > dW pattern > > cardiac arrest > > ECG normalized after defibrillation > > PCI | Survived |

| Plane et al[51] | 2019 | Cardiac arrest > > dW pattern > > CAG and thrombus aspiration | Survived |

| Shepherd and Furiato[52] | 2020 | Chest pain > > dW pattern > > cardiac arrest > > PCI | Survived |

| Liu and Wang[53] | 2020 | Chest pain > > cardiac arrest > > STEMI > > dW pattern > > PCI | Survived |

| Rujuta et al[54] | 2024 | Chest pain > > dW pattern > > cardiac arrest > > Q waves and accelerated idioventricular rhythm > > Cardiogenic shock > > IABP > > PCI | Survived |

| Wang et al[56] | 2022 | Chest pain > > cardiac arrest > > dW pattern > > cardiac arrest > > STEMI > > PCI | Survived |

| Tang et al[13] | 2024 | 2/12 dW pattern patients developed sudden cardiac arrest | Survived |

| Alireza et al[11] | 2025 | 2/967 (7%) dW pattern > > VF | Not mentioned |

The authors concluded that dW pattern is not an independent pattern but rather an early stage of STEMI that requires immediate intervention and reperfusion. However, timely thrombolysis can be successful when PCI is unavailable[9,17]. In dW pattern patients, the appearance of STD could be upsloping, horizontal, or down-sloping, and this is crucial in understanding the exact pathogenesis and prognosis[56]. Zhan et al[57] showed that a maximal STD pattern correlates with more critical ischemic changes within the subendocardial region in comparison to a non-upsloping STD. Maximal STD in dW pattern in lead V2 or V3 showed a PPV of 89% for all patients and 98% for those without an ST-segment elevation in V2 for identifying LAD as the culprit vessel[57]. Hence, upsloping STD > 1 mm at the J point with peaked T waves in the absence of ST-segment elevation in leads V2-V6 prompts urgent intervention in dW pattern patients[57,58]. This finding was supported by a retrospective study showing that STD upsloping is associated with higher rates of positive troponin levels, angiographic thrombus, in-hospital revascularization, overall mortality, and a lower ejection fraction compared with the non-upsloping STD group[59].

According to Zhan et al[57], pathological Q wave or poor R wave progression in leads V1-V4 was seen in 74% of dW pattern cases. Moreover, the reported rate of minimal ST-segment elevation in aVR was 100% in Verouden et al’s study[2], who proposed that widespread transmural ischemia results in ischemic current steering toward the aVR lead and away from the precordial leads. However, Wall et al[60] found that ST-segment elevation in aVR occurred in only 50% of patients with dW pattern. Notably, the more ST-segment elevation in the aVR lead, the more extensive myocardial ischemia and involvement of critical coronary arteries in dW pattern patients, such as LMCA[61].

It is theorized that dW pattern is likely caused by regional subendocardial ischemia, with myocardial protection occurring through various mechanisms, such as collateral blood flow, ischemic preconditioning, or maintained forward blood flow (Figure 2)[11,62,63]. Importantly, assessment of the ischemia vector direction helps identify the site of greater ischemia, and the amount of ST-segment elevation indicates its severity[64]. The proposed mechanism underlying the lack of ST-segment elevation in an LAD occlusion involves an anatomical deviation within the Purkinje fibers, resulting in delayed endocardial conduction[2]. Furthermore, ischemic adenosine triphosphate (ATP) depletion results in the inactivation of sarcolemmal ATP-sensitive potassium channels, precluding ST-segment elevation[2]. In support of this theory, Li et al[65] reported an animal study showing that mice deficient in ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP knockout) lacked ST elevation following LAD ligation.

As for the STD in dW pattern, it is due to the negative voltage difference between ischemic subendocardial and normal subepicardial action potentials during the plateau phase[62]. This difference, caused by subendocardial ischemia, aligns with the transmembrane action potential summation theory, which leads to STD on the surface ECG[62]. Potentially, the upsloping STD and tall, peaked T waves occur due to hypoxia-induced changes in ATP-sensitive potassium channels, which delay repolarization in the subendocardial region and alter the shape of the transmembrane action potential[66]. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging proposed an interplay of differential action potential expression and collateral circulation as a possible explanation of dW pattern[67].

The dW pattern has been regarded as a transient phenomenon rather than a static one, as it may progress to STEMI or start as STEMI and then progress to dW pattern[16]. This implies the importance of continuous ECG monitoring in patients with dW pattern. Such a dynamic ECG change is due to dW pattern reflecting subendocardial ischemia, but as it advances to transmural ischemia, the pattern evolves into a STEMI appearance[68]. Xu et al[9] reported an average time to ECG evolution from dW pattern to STEMI of approximately 114 minutes in 13 patients.

Our review revealed that 69 patients exhibited ECG transformation: 51 developed a STEMI following the initial ECG of dW pattern, 8 presented with a STEMI that later transformed into dW pattern, and 10 patients presented with concomitant ECG findings[11,22-25,69]. One case report, including a 31-year-old male, showed dW pattern as a transient event after LAD stenting (at the time of reperfusion)[70]. In this patient, the classic ST-segment elevation was observed in the initial ECG (as a total LAD occlusion) before and after reperfusion. At the same time, dW pattern appeared between (reflecting subtotal occlusion with spontaneous recanalization). Theoretically, Zhao et al[70] categorized dW pattern into two phenomena. The first category is static, in which the J-point depression remains until LAD patency is achieved; this category does not progress to STEMI. The second category is dynamic, in which STEMI pattern transformed into dW pattern, and vice versa, depending on the total LAD occlusion and spontaneous recanalization state transitions. Furthermore, Pica et al[71] reported a case of STEMI due to acute stent thrombosis following PCI therapy for dW pattern in the LAD. This patient was in a hyperglycemic state, which could lead to the non-opening of ATP-sensitive potassium channels, resulting in differences in ischemic ECG changes[71].

To further elaborate on cases showing ECGs with concomitant STEMI and dW pattern, Tomcsányi et al[22] reported two cases with an ECG showing ST-segment elevation in V1-V3, a transient isoelectric ST segment with a subsequent tall T wave in lead V4, and upsloping ST depression in leads V5-V6, followed by tall T waves. These patients were found to have type III LAD (a large wrap-around vessel). The coexistence of both patterns is not relevant to the inactivation of sarcolemmal ATP-sensitive potassium channels or anatomical atypia in the Purkinje fibers[22]. Instead, the different ischemic changes and their extent across the myocardial layers led to this ST segment continuum such that transmural ischemia occurs in the proximal anterior wall, which exhibits near-transmural ischemia as it extends distally. By contrast, in the most distal region, ischemia intensifies but remains limited to the subendocardium[22].

Simultaneous occlusion of two major vessels is a rare event that requires careful ECG interpretation, especially in hemodynamically unstable patients, as described by Tsuchida et al[25]. Their case report raised the following question: Is dW pattern an STD or merely a reciprocal change? ST-T deviation patterns can vary with the temporal sequence and anatomical dominance of the two infarct-related arteries (LAD and RCA) in a patient presenting with bradycardia, ST elevation in the inferior leads, and dW pattern.

Notably, 10 cases reported ECG evolution from dW pattern to Wellens syndrome. The ECG pattern in Wellens is mainly marked by deep inverted T waves in leads V1-V4, persisting for weeks after the resolution of chest pain, and is also considered a STEMI equivalent[29]. dW pattern patients exhibiting the Wellens pattern were found to have non-complete occlusion in the pLAD[30]. Wang et al[30] concluded that the sequential appearance of both patterns (dW pattern > > > Wellens) within a short time contributes to a higher diagnostic accuracy of non-complete or near-complete LAD occlusion. Ratzenböck et al[33] concluded that Wellens ECG could indicate myocardial reperfusion after successful stenting of LAD in a patient presenting with dW pattern. Moreover, the Wellens pattern may be related to vasospasm or the dissolution of a possible thrombus following medical therapy[33].

dW pattern on the ECG would be present in any ECG lead and would be associated with acute occlusion of any coronary artery. The precordial lead with upsloping STD holds significance in identifying LAD as the culprit artery in dW pattern patients. However, as more cases emerge in the literature, it has become apparent that dW pattern can occur when vessels other than the LAD are occluded. Hence, Rachmi et al[72] highlighted the importance of additional findings alongside the classic STD appearance, such as non-upsloping STD, STE, Q waves, and R/S ratio, in identifying the culprit vessel in dW pattern patients. According to our review, the LCx, RCA, LMCA, diagonal branches (D1 and D2), or OM occlusion can be the affected vessel in dW pattern patients.

Nine cases in the literature attribute dW pattern to LMCA stenosis[13,38,39,43,73-76]. Numerous studies have established the link between aVR ST-segment elevation and diffuse STD in patients with significant LMCA disease or extensive CAD[77-79].

Zhan et al[74] described an LMCA occlusion in a patient presenting with a dW pattern that resembled an LAD occlusion. However, the ECG illustrated global subendocardial ischemia, as leads V4-V5 showed maximal STD with T wave inversion in V5-V6, which warranted the possibility of an occlusion in the LMCA rather than LAD. Furthermore, they proposed that collateral circulation from the LAD and ischemic preconditioning prevented deterioration in the patients. Moreover, Sunbul et al[38] reported a dW pattern with LMCA occlusion, which was prominently visible in leads V3-V6. Kashou et al[75] reported severe LMCA stenosis followed by a complete LAD occlusion, which demonstrated dW pattern with maximal STD in lead V5. The proposed explanation for the involvement of the anterolateral leads is diffuse subendocardial ischemia within the corresponding ventricular walls and transmural ischemia in the basal interventricular septum due to the lack of collateral circulation from the LAD[75].

Six cases reported RCA to be the isolated-injury artery in dW pattern patients[25,80-84]. Typically, ST-segment changes within leads II, III, augmented voltage foot, and V4-V6 correlate with RCA occlusion[56]. Tsutsumi and Tsukahara[81] presented similar ECG findings in the inferolateral leads in dW pattern, which were also confirmed by an echocardiogram. Chen et al[80] described the presence of junctional rhythm resulting from absent blood flow to the sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes due to RCA occlusion in dW pattern.

LCx is involved almost concomitantly with LAD in most cases; however, six cases reported LCx as the culprit lesion[6,85-89]. STD at the J point with upsloping ST-segments and hyperacute T wave in the inferior and lateral wall leads is associated with acute LCX occlusion[85]. Manno et al[86] showed that an upright T wave in lead V1 is more common in patients with isolated LCx artery disease. An acute occlusion of the LCx artery causes a lack of blood supply to the inferobasal and lateral areas within the left ventricle, hence resulting in a posterolateral myocardial infarction[89]. Additionally, a peaked R wave, unlike S waves, in leads V1-V2 indicates the presence of a posterior infarct, as it is reflective of Q waves in posterior leads[72]. Rachmi et al[72] reported a case of a posterolateral myocardial infarction, characterized by prominent R waves in leads V1-V2 and ST-segment elevation in leads I and augmented voltage left arm, alongside the classic dW pattern. The post-procedural ECG further confirmed the LCx occlusion, as it revealed prominent ST-segment elevation in leads V5-V6. Additionally, echocardiography findings revealed hypokinesis in the basal-mid-apical anterolateral and inferolateral segments[72].

Xu et al[24] presented a rare dW pattern with an occluded OM artery; the ECG showed dW pattern and a STEMI in the posterior leads. Moreover, there are eight cases with the diagonal branch reported as the culprit vessel in dW pattern[9,32,90-95]. Montero Cabezas et al[92] reported the incidence of dW pattern due to a lesion in the D1 branch with a seemingly patent LAD. However, following reperfusion, the ECG illustrated a typical D1 infarct with a persistent ST-segment elevation in the anterolateral leads from V2-V6 with negative T waves and Q waves in lead I and augmented voltage left arm[92].

The ideal management of dW pattern/dW syndrome requires early revascularization with PCI, as it is a STEMI equivalent[96]. International guidelines do not yet recommend the use of thrombolytic agents for dW pattern[97,98]. However, thrombolytic agents have been reported to be effective, particularly in resource-limited settings. Six cases reported failed thrombolysis, necessitating the transfer of the patients to centers equipped with catheterization laboratories[9,45,55,99]. Among 11% of patients who were prescribed thrombolytic therapy in non-PCI centers, 82% had successful reperfusion[55]. This reperfusion rate in dW pattern patients was similar to that reported in STEMI patients[55]. Xu et al[9] reported successful resolution of a STEMI that developed after dW pattern in one patient after thrombolytic therapy without further revascularization. At the same time, two cases failed, and one patient experienced vessel blockage again[9]. Xiao et al[99] reported inefficient use of reteplase, leading to anterior STEMI that resolved only after PCI. In 2019, the Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute STEMI recommended that patients with dW syndrome need to be managed as a distinct STEMI subtype; however, in non-PCI centers, no clear guidance is available on whether intravenous thrombolytic therapy should be preferred for dW syndrome patients[99]. Large-scale studies are needed to evaluate the use of thrombolytic agents in dW pattern when PCI is unavailable or in cases of patient refusal, as their safe use remains controversial.

With regard to ECG evolution following reperfusion therapy, STEMI was observed in seven patients who underwent PCI for dW pattern, including five with LAD, one with LCx, and one with diagonal branch occlusions. The postprocedural ECG evolution from dW pattern to a STEMI, commonly in the anterior wall, can be attributed to microcirculatory impairment and progressive myocardial necrosis[100]. Another probable explanation is the rupture of plaque remnants, which embolize distally, or the akinesis of wall motion following intervention[101]. However, the evolution to STEMI with Q waves in leads I and aVR following reperfusion is a standard finding in a diagonal branch occlusion[98,102]. Furthermore, four of the patients who received primary thrombolytic therapy showed an evolving STEMI after reperfusion therapy, which necessitated PCI[9,99,103].

Several case reports in the literature described conditions associated with dW pattern, thereby expanding the range of presentations of this phenomenon (Table 4). For instance, acute stent thrombosis and myocarditis have been noted to present with dW pattern likely due to overlapping pathophysiological mechanisms, including the inactivation of sarcolemmal ATP-sensitive potassium channels or anatomical variants in the Purkinje fibers[104,105]. Molina-Lopez et al[106] described a patient who developed a dW pattern following aortic valve repair, which was attributed to severe aortic stenosis that resulted in elevated left ventricular pressure and ischemia, and was associated with the Bezold-Jarisch reflex. Chen et al[107] reported a dW pattern following chest pain in a patient at the end of an elective PCI procedure. The troponin level became positive, and no stenosis was detected on the CAG. The patient’s symptoms were alleviated, and dW pattern disappeared after treatment with diltiazem.

| Ref. | Years | Medical condition |

| García-Izquierdo et al[104] | 2018 | Myocarditis |

| Porciuncula et al[105] | 2019 | Acute stent thrombosis |

| Chen et al[107] | 2020 | After elective PCI (asymptomatic and no STEMI-equivalent on arrival) |

| Molina-Lopez et al[106] | 2024 | Post aortic stenosis repair |

| Ando et al[108] | 2020 | Vasospastic angina |

| Azdaki et al[44]; Hirase et al[91] | 2021; 2020 | Spontaneous coronary artery dissection |

| Dai et al[110] | 2021 | Kounis syndrome |

| Al-Assaf et al[5] | 2024 | Blunt chest trauma |

| Zhang et al[109] | 2022 | Type A aortic dissection |

| Daas et al[111] | 2025 | Coronary artery ectasia |

| Li et al[112] | 2025 | Pheochromocytoma |

| Wei et al[113] | 2022 | Stroke-heart syndrome |

Furthermore, Ando et al[108] reported a case of vasospastic angina with transient ischemic changes that possibly mimicked the dW pattern. A separate report by Zhang et al[109] described a dW pattern in a patient with type A aortic dissection, likely resulting from compression of the LMCA, LAD, and LCx. Al-Assaf et al[5] documented another interesting case with blunt chest trauma, in which they suggested that dW pattern was due to AMI caused by rupture of a pre-existing atherosclerotic plaque. Additionally, Dai et al[110] proposed that the ECG manifestations in Kounis syndrome may resemble those of the dW pattern, although this relationship requires further clarification.

Other reports have demonstrated that dW pattern can be caused by spontaneous coronary artery dissection in the diagonal branch in instances where a large diagonal branch occlusion is distributed parallel to the LAD[91]. This patient received no specific therapy and had an uneventful recovery. Another patient with extensive myocardial infarction due to spontaneous coronary artery dissection of the LAD was treated initially with a thrombolytic agent. The patient’s condition deteriorated; subsequently, the patient expired. Post-mortem examination confirmed the diagnosis, as CAG was not feasible[44].

dW pattern has also been seen in a patient who had congenital coronary artery ectasia in addition to a plaque rupture within the coronary artery. The mechanism that led to dW pattern is thought to be triggered by a plaque rupturing within the dilated coronary artery, causing a spontaneous dissection, which then results in a series of ischemic changes[111].

A patient with pheochromocytoma presented with ECG findings of dW pattern, attributed to coronary vasospasm due to increased catecholamine secretion from the tumor instead of it being a typical myocardial infarction[112].

Wei et al[113] described a patient who suffered from a cerebellar and pontine stroke, which induced a myocardial infarction manifesting as dW pattern on ECG. This collection of findings was classified as stroke-heart syndrome. It was hypothesized that autonomic dysregulation was caused by a stroke resulting in an uncontrolled catecholamine surge, which augments inflammation and leads to myocardial ischemia, causing the findings of dW pattern on the ECG[113].

In addition to the dW pattern/dW syndrome, STEMI-equivalent conditions include Wellens syndrome, posterior myocardial infarction, T wave precordial instability, and delayed activation wave[113]. Posterior MI is seen with STD in leads V1-V3, unlike dW pattern, where STD typically involves V1-V4 and with dominant R waves[114]. STD must measure more than 0.5 mm and may sometimes progress into leads V5-V6[59]. Also, posterior MIs are linked with an acute inferior or lateral myocardial infarction[114].

Wellens syndrome, which may signify an impending myocardial infarction, can appear on the ECG as two distinctive T wave changes. The first type is characterized by deeply inverted T waves in leads V2 and V3, while the second type presents with biphasic T waves in leads V2 and V3 after angina relief[30,115,116]. It is also worth mentioning that no Q waves can be seen in Wellens and that precordial R wave progression is absent[115], indicating that reperfusion is the underlying mechanism in a non-complete occluded vessel. Furthermore, acute occlusion of the LCx may sometimes develop a rare ECG pattern, known as the delayed activation wave[117]. This pattern is characterized by a notch-like appearance in the terminal QRS complex, known as the N wave, with a height of at least 2 mm relative to the PR segment[59]. These notches can appear on different leads, with reports stating that they appear on leads I, II, III, augmented voltage foot, and augmented voltage left arm[117].

Another STEMI equivalent is T wave precordial instability, also known as loss of precordial T wave balance. The key factor in this pattern is the T wave amplitude, which is greater in V1 than in V6, and an upright T wave is present in V1[59]. This pattern is critical to know, as not all patients’ ECGs presenting with it are suffering from coronary artery occlusion; it may be explained as ventricular early repolarization[118,119]. Figure 3 shows the typical and atypical ECG presentations of LAD stenosis, in addition to the types of STEMI equivalent.

The major pitfalls in managing dW syndrome/pattern include its frequent misdiagnosis as non-STEMI, leading to inappropriate patient triage, and the failure to recognize its dynamic ECG evolution, which results in critical delays in urgent revascularization.

Currently, the clinical management of dW syndrome/dW pattern primarily requires attention to: (1) Guidelines and consensus on the management of the dW phenomenon are needed; (2) ECG alone may fail to predict the angiographic finding in 30% of ACS cases; therefore, a differential diagnosis list and a high index of suspicion should be maintained to reduce time-to-treat and mortality; (3) Collaboration is necessary between primary care, the emergency department team, and cardiologists (interprofessional team); (4) A serial ECG is recommended whenever dW pattern is suspected; (5) dW pattern or dW syndrome should be considered a STEMI equivalent, although it is not explicitly detailed in the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines; (6) Continuous monitoring is needed as dW pattern can evolve into classic STEMI; (7) Early cardiologist consultation, optimized medications, and admission to a monitored intensive care unit are recommended; (8) CAG, timely revascularization using PCI, or, otherwise, thrombolytic therapy can be administered if there is no contraindication; and (9) The impact of dW pattern on the left ventricle function requires assessment.

The prevalence of dW pattern is low or underestimated, requiring a review of ECG databases in Department of Emergency and Cardiac Catheterization Units. Risk of bias assessment and study quality were not performed in this work, as we identified only a few retrospective studies with dW pattern subgroups, along with a few case series (159 papers yielded 322 cases). Follow-up of post-charge dW pattern patients was not documented. The individual culprit vessel was not specified for each patient’s age and gender in some retrospective studies. Comparisons by sex and age should be interpreted cautiously, as they are mainly based on scattered cases or case series. Given the small and uneven subgroups, statistical testing may yield misleading results and lead to overinterpretation. However, systematic reviews of case reports have shown considerable impact in reducing unfavorable outcomes for documenting clinical patterns and therapy outcomes in uncommon disorders[55]. The time to diagnose and intervene was not captured, as it was not specified in most cases. However, door-to-balloon was reported in three studies[10,11,13]. The time to evolution was rarely reported. The question now is, which of these three forms - dW pattern, dW sign, or dW syndrome - should be treated promptly? The literature did not differentiate among these three terms, which were often used interchangeably, and did not describe their silent form (silent pattern or sign). Therefore, this issue needs further elaboration and guidelines.

The three forms of the dW phenomenon (dW pattern, dW sign, and dW syndrome) are commonly used in most of the literature, with no consensus on the criteria for the chosen therapy. dW syndrome is preferable whenever associated clinical manifestations are present. This phenomenon has unique risk factors, pathophysiology, and angiographic characteristics. It should be managed as an indicator of a STEMI equivalent requiring urgent intervention. However, it is often underrecognized and therefore requires a high index of suspicion. Age and gender have distinct culprit lesions and coronary artery involvement in patients with dW pattern. Despite advances in understanding its dynamic nature and the clinical significance of STEMI equivalents, challenges persist in timely diagnosis and management. This review em

| 1. | de Winter RJ, Verouden NJ, Wellens HJ, Wilde AA; Interventional Cardiology Group of the Academic Medical Center. A new ECG sign of proximal LAD occlusion. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2071-2073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Verouden NJ, Koch KT, Peters RJ, Henriques JP, Baan J, van der Schaaf RJ, Vis MM, Tijssen JG, Piek JJ, Wellens HJ, Wilde AA, de Winter RJ. Persistent precordial "hyperacute" T-waves signify proximal left anterior descending artery occlusion. Heart. 2009;95:1701-1706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hayakawa A, Tsukahara K, Miyagawa S, Okajima Y, Takano K, Mitsuhashi T, Maejima N, Kosuge M, Tamura K, Kimura K. The reappearance of de Winter's pattern caused by acute stent thrombosis: A case report. J Cardiol Cases. 2022;25:404-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ghazali H, Mabrouk M, Ellouz M, Chermiti I, Keskes S, Souissi S. De Winter ST-T syndrome: an early sign of ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. PAMJ Clin Med. 2020;2:89. |

| 5. | Al-Assaf O, Abumuaileq L, Skikic E, Bahuleyan S. De Winter Syndrome Secondary to a Blunt Chest Trauma. Clinical Medicine Reviews and Case Reports. Clin Med Rev Case Rep. 2024;11:445. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Shahri B, Vojdanparast M, Keihanian F, Eshraghi A. De Winter presentations and considerations: a case series. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16:368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chyu KY, Shah PK. ECGs in Critical Care Cardiology: Do Not Miss That Myocardial Infarction. JACC Case Rep. 2022;4:1297-1305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ni NI. Analysis of clinical features and coronary angiography in 10 patients with de winter syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:ehab849.096. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Xu J, Wang A, Liu L, Chen Z. The de winter electrocardiogram pattern is a transient electrocardiographic phenomenon that presents at the early stage of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Clin Cardiol. 2018;41:1177-1184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | de Winter RW, Adams R, Amoroso G, Appelman Y, Ten Brinke L, Huybrechts B, van Exter P, de Winter RJ. Prevalence of junctional ST-depression with tall symmetrical T-waves in a pre-hospital field triage system for STEMI patients. J Electrocardiol. 2019;52:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Alireza M, Nader A, Alireza F, Babak B, Bahare G. Traces of cardioprotection behind the uncertainty of the de winter pattern. J Electrocardiol. 2025;92:154056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fujii T, Ikari Y. Clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndrome after presentation of unique electrocardiographic findings. J Electrocardiol. 2024;85:31-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tang W, Xu J, Cheng F, Liu T, Lin Z, Chen B, Chen J, Luo L. Coronary Angiographic Features of de Winter Syndrome: More Than Just Occlusion of the Left Anterior Descending Artery. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2024;29:e70029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Menaka WH, Samarajiwa GM. Case report of de Winter Syndrome and ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Sri Lanka J Health Res. 2022;2:116-119. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Lam RPK, Cheung ACK, Wai AKC, Wong RTM, Tse TS. The de Winter ECG pattern occurred after ST-segment elevation in a patient with chest pain. Intern Emerg Med. 2019;14:807-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lin YY, Wen YD, Wu GL, Xu XD. De Winter syndrome and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction can evolve into one another: Report of two cases. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:3296-3302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Xu W, Xu L, Peng J, Huang S. Thrombolytic therapy in a patient with chest pain with de Winter ECG pattern occurred after ST-segment elevation: A case report. J Electrocardiol. 2019;56:4-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Qayyum H, Hemaya S, Squires J, Adam Z. Recognising the de Winter ECG pattern - A time critical electrocardiographic diagnosis in the Emergency Department. J Electrocardiol. 2018;51:392-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Huang W, Mai L, Lu J, Li W, Huang Y, Hu Y. Evolutionary de Winter pattern: from STEMI to de Winter ECG-a case report. ESC Heart Fail. 2022;9:771-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ramakumar V, Panda A, Yadav S. A Rare Sequence of Events in Acute Coronary Syndrome. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:1391-1392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Andreou AY. Acute Coronary Syndrome Manifesting Dynamic Electrocardiographic Changes. Clin Case Rep. 2025;13:e70571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tomcsányi J, Littmann L. Precordial ST-segment continuum: A variant of the de Winter sign. J Electrocardiol. 2022;72:98-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wang S, Shen L. de Winter syndrome or inferior STEMI? BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021;21:614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Xu W, Zou H, Huang S. Junctional ST-depression and tall symmetrical T-waves with an obtuse marginal artery occlusion: A case report. J Electrocardiol. 2019;54:40-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tsuchida K, Nagai H, Oda H, Kashiwa A, Tanaka K, Hosaka Y, Ozaki K, Takahashi K. Acute coronary syndrome with simultaneous two-vessel occlusion De Winter ST-segment depression or reciprocal change? J Electrocardiol. 2023;81:70-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zhu Y, Luo S, Huang B. Evolution of de Winter Into Wellens on Electrocardiogram-What Happened? JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:1647-1649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhong Z, Chen J, Xu N, Qiu Z, Zhang J, Liu G, Zeng F. A Case of Wellens Syndrome Combined with De Winter Syndrome. Clin Med Res. 2022;11:36-41. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Noor Ashikin MS, Mohd Ridzuan MS. APCU 40 De winter syndrome: a rare but fatal entity often missed. Open Heart. 2025;12. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Arima N, Yamasaki N, Furushima T, Miyamoto Y, Moriki T, Miyagawa K, Noguchi T, Kubo T, Kitaoka H. Dynamic ECG change from de Winter to Wellens - Rare ECG change in acute coronary syndrome. J Cardiol Cases. 2025;31:93-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wang F, Zhang X, Pang H, Wang Y. Evolution of de Winter syndrome to Wellens syndrome: a case report and literature review. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1415306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Summers MR, Lavigne PM, Mahoney PD. Completion peripheral angiography in single-access, Impella-assisted, high-risk PCI: Using a buddy microcatheter sheath after MANTA closure for imaging and potential bailout. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;99:1778-1783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ahmed AS, Divani G, Ansari AH. Perplexing Electrocardiogram in a 50-Year-Old Male with Chest Pain. Am J Med. 2022;135:e4-e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ratzenböck E, Nestelberger T, Kühne M. The Winter Gets Well(ens)—A Rare Pattern of Left Anterior Descending Artery Occlusion. Cardiovasc Med. 2020;23:w02089. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | van Rensburg RJ, Schutte J, de Beenhouwer T. Chest pain: The importance of serial ECGs. Cleve Clin J Med. 2021;88:538-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ma X, Bao M. de Winter electrocardiogram pattern evolving into Wellens electrocardiogram pattern in post-percutaneous coronary intervention therapy: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2025;9:ytaf139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Ahmadi M, Khameneh-Bagheri R, Vojdanparast M, Jafarzadeh-Esfehani R. Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome and de Winter patterns; An implication for paying special attention to electrocardiogram. ARYA Atheroscler. 2019;15:201-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Chang Q, Xu Z, Liu R. Chest Pain in a Middle-Aged Man. JAMA Cardiol. 2025;10:199-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Sunbul M, Erdogan O, Yesildag O, Mutlu B. De Winter sign in a patient with left main coronary artery occlusion. Postepy Kardiol Interwencyjnej. 2015;11:239-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Umalkar GN, Gadkari C, Sahu G, Chavan G, Lohakare A. Timely lifesaving recanalization in two cases with De winters T wave: Case series. Med Sci. 2022;26:01-06. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Felicioni SP, de Alencar JN, Centemero MP, Lourenço UR, De Marchi MFN, Scheffer MK, Costa ACM, Fernandes RC, Uemoto VR, Baronetti R. The de Winter electrocardiographic pattern: A systematic review of case reports. J Electrocardiol. 2024;87:153821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Goebel M, Bledsoe J, Orford JL, Mattu A, Brady WJ. A new ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction equivalent pattern? Prominent T wave and J-point depression in the precordial leads associated with ST-segment elevation in lead aVr. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:287.e5-287.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Morris NP, Body R. The De Winter ECG pattern: morphology and accuracy for diagnosing acute coronary occlusion: systematic review. Eur J Emerg Med. 2017;24:236-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Liu CW, Zhang JX, Hu YC, Wang L, Zhang YY, Cong HL. The de Winter electrocardiographic pattern evolves to ST elevation in acute total left main occlusion: A case series. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2022;27:e12855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Azdaki N, Farzad M, Moezi S, Partovi N, Ashabyamin R. De Winter's pattern: an uncommon but very important electrocardiographic sign in the prompt recognition of spontaneous occlusive coronary artery dissection in young patients with chest pain (a case report). Pan Afr Med J. 2021;39:112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Missaoui E, Cherifa BC, Ahmed M, Naija M, Chebili N. The De Winter Dilemma: The Management and Outcome of a Patient with De Winter Electrocardiographic Pattern in the Pre-Hospital Setting. Med Case Rep. 2020;6:149. |

| 46. | John TJ, Pecoraro A, Weich H, Joubert L, Griffiths B, Herbst P. The de Winter's pattern revisited: a case series. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2020;4:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Fernandez-Vega A, Martínez-Losas P, Noriega FJ, Fernandez-Ortiz A, Biagioni C, Cruz-Utrilla A, Martinez-Vives P, Garcia-Arribas D, Viana-Tejedor A. Winter Is Coming After a Cardiac Arrest. Circulation. 2017;135:1977-1978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Carr MJ, O'Shea JT, Hinfey PB. Identification of the STEMI-equivalent de Winter Electrocardiogram Pattern After Ventricular Fibrillation Cardiac Arrest: A Case Report. J Emerg Med. 2016;50:875-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Alhatemi AQM, Hashim HT, Aziz EMH, Abdulhussain TK, Hashim AT. De Winter syndrome in action: Captured on defibrillator. Clin Case Rep. 2024;12:e8511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Wismiyarso DE, Adriana C, Mangkoesoebroto AP, Christiawan A, Sulma AN, Effendi LHDP, Ardhianto P. Total occlusion of coronary artery without ST-segment elevation a case series of ‘de Winter’ electrocardiogram pattern. Bali Med J. 2021;10:347-350. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Plane AF, Valette X, Blanchart K, Ardouin P, Beygui F, Roule V. Occluded or Not?: A Subtle Electrocardiographic Answer. JACC Case Rep. 2019;1:663-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Shepherd C, Furiato A. Evolving de Winter Presentation of Acute Myocardial Infarction. West Florida Division GME Research Day. 2020: 34 Available from: https://scholarlycommons.hcahealthcare.com/westflorida2020/34/. |

| 53. | Liu L, Wang D. A rare transitory change of the De Winter ST/T-wave complex in a patient with cardiac arrest: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e20133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Rujuta P, Pooja V, Ashish M, Jayal S, Saurabh D, Gaurav S. Reperfusion Therapies in ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction Equivalents. J Clin Prev Cardiol. 2023;12:127-129. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 55. | Parthiban N, Boland F, Sani H. Systematic Review of the Clinical Features of de Winter Syndrome and the Role of Thrombolytic Therapy in Resource-limited Settings. J Asian Pac Soc Cardiol. 2025;4:e08. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 56. | Wang X, Chen Y, Yang X, Yang L. Two successive electrocardiograms of an old male with acute myocardial infarction: What on earth was going on? Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2022;27:e12950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Zhan ZQ, Li Y, Han LH, Nikus KC, Birnbaum Y, Baranchuk A. The de Winter ECG pattern: Distribution and morphology of ST depression. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2020;25:e12783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Raja JM, Nanda A, Pour-Ghaz I, Khouzam RN. Is early invasive management as ST elevation myocardial infarction warranted in de Winter's sign?-a "peak" into the widow-maker. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7:412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Ete T, Jha P, Barman B, Mishra A, Kapoor M, Malviya A, Raphael V, Issar NK. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Lung Atypically Involving Heart: A Case Report With Literature Review. Cardiol Res. 2015;6:329-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Wall J, White LD, Lee A. Novel ECG changes in acute coronary syndromes. Would improvement in the recognition of 'STEMI-equivalents' affect time until reperfusion? Intern Emerg Med. 2018;13:243-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Fang Y, Zhang M, Wu J, Li Z. De Winter sign combined with pronounced aVR lead ST segment elevation and left anterior fascicular block: a case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2025;25:647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Gorenek B, Kudaiberdieva G. Atrial fibrillation detected by dual-chamber pacemakers and structural heart disease. J Electrocardiol. 2009;42:293-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Kinoshita S, Katoh T. Atrioventricular block with 4:2 conduction pattern: concealed electrotonic conduction as an alternative mechanism. J Electrocardiol. 2010;43:466-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Yang W, Liu H, Zhu M, Song Z. The de Winter electrocardiographic pattern of proximal left anterior descending occlusion. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35:937.e1-937.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Li RA, Leppo M, Miki T, Seino S, Marbán E. Molecular basis of electrocardiographic ST-segment elevation. Circ Res. 2000;87:837-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Fiol Sala M, Bayés de Luna A, Carrillo López A, García-Niebla J. The "De Winter Pattern" Can Progress to ST-segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2015;68:1042-1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Vilela EM, Braga JP. The de Winter ECG Pattern. 2024 Jan 31. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. [PubMed] |

| 68. | Chen Y, Chen B, Zhang L, Liao W, Wang M. The dynamic evolution of the de Winter ECG pattern that is easily overlooked and life-threatening: a case report and literature review. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2025;12:1574829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Zheng XB. Dressler - de Winter sign with acute inferoposterior STEMI: An ECG dilemma in artery localization. J Electrocardiol. 2024;86:153769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Zhao YT, Wang L, Yi Z. Evolvement to the de Winter electrocardiographic pattern. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:330-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Pica S, Ballestrero G, Pistis G, Crimi G. Acute stent thrombosis unveils two electrocardiogram patterns in a patient with 'De Winter T-waves' anterior myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Rachmi DA, Budi Mulia EP, Amrilla Fagi R. Atypical de Winter ECG: What is the Culprit? J Tehran Heart Cent. 2024;19:136-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Siow YK, Francis DD, Ruhani AI, Abidin SKZ, Khoo CS. de Winter pattern: An important electrocardiographic sign not to be missed. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2021;51:281-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Zhan ZQ, Li Y, Wu LH, Han LH. A de Winter electrocardiographic pattern caused by left main coronary artery occlusion: A case report. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060520927209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Kashou AH, LoCoco S, Asirvatham SJ, May AM, Noseworthy PA. A lateral lead variant of the de Winter pattern due to left main stenosis and left anterior descending artery occlusion. J Electrocardiol. 2020;61:77-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Xenogiannis I, Kolokathis F, Alexopoulos D, Rallidis LS. Myocardial infarction due to left main coronary artery total occlusion: A unique electrocardiographic presentation. J Electrocardiol. 2023;76:26-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Yamaji H, Iwasaki K, Kusachi S, Murakami T, Hirami R, Hamamoto H, Hina K, Kita T, Sakakibara N, Tsuji T. Prediction of acute left main coronary artery obstruction by 12-lead electrocardiography. ST segment elevation in lead aVR with less ST segment elevation in lead V(1). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1348-1354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Kashou AH, May AM, DeSimone CV, Deshmukh AJ, Asirvatham SJ, Noseworthy PA. Diffuse ST-segment depression despite prior coronary bypass grafting: An electrocardiographic-angiographic correlation. J Electrocardiol. 2019;55:28-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Gorgels AP, Vos MA, Mulleneers R, de Zwaan C, Bär FW, Wellens HJ. Value of the electrocardiogram in diagnosing the number of severely narrowed coronary arteries in rest angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72:999-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Chen CC, Cai BY, Qi XW. Uncommon Culprit Vessel of de Winter Electrocardiogram Pattern. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183:366-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Tsutsumi K, Tsukahara K. Is The Diagnosis ST-Segment Elevation or Non-ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction? Circulation. 2018;138:2715-2717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Ghaffari S, Pourafkari L, Nader ND. "de Winter" electrocardiogram pattern in inferior leads in proximal right coronary artery occlusion. Arch Cardiol Mex. 2021;91:366-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Karna S, Chourasiya M, Chaudhari T, Bakrenia S, Patel U. De Winter Sign in Inferior Leads: A Rare Presentation. Heart Views. 2019;20:25-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Mufti G, Shali SH, Ahmed AS. Answer: an uncommon electrocardiogram pattern in a case of acute chest pain. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2025;14:193-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Chen Q, Zou T, Pang Y, Ling Y, Zhu W. The De Winter-like electrocardiogram pattern in inferior and lateral leads associated with left circumflex coronary artery occlusion. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7:4301-4304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Manno BV, Hakki AH, Iskandrian AS, Hare T. Significance of the upright T wave in precordial lead V1 in adults with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983;1:1213-1215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Erdem AB, Tümer M. De Winter Wave with ST Segment Elevation Equivalent with Speech Disorder; A Case Report. J Emerg Med Case Rep. 2022;13:19-21. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Shehata K, Shrestha DB, Shtembari J, Khatiwada R, Khosla S. Left circumflex STEMI presenting as de Winter sign, an ECG Zebra that gives you the chills! A case report. J Electrocardiol. 2023;80:96-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Shao D, Yang N, Zhou S, Cai Q, Zhang R, Zhang Q, Wei Z, Li H, Zheng Y, Tong Q, Zhang Z. The "criminal" artery of de Winter may be the left circumflex artery: A CARE-compliant case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e20585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Lin TC, Lee WS, Kong CW, Chan WL. Congenital absence of the left circumflex coronary artery. Jpn Heart J. 2003;44:1015-1020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Hirase Y, Wake M, Hirata K. de Winter Electrocardiographic Pattern Caused by Diagonal Branch Lesion. JACC Case Rep. 2020;2:1451-1453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Montero Cabezas JM, Karalis I, Schalij MJ. De Winter Electrocardiographic Pattern Related with a Non-Left Anterior Descending Coronary Artery Occlusion. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2016;21:526-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Demarchi A, Frigerio L, Rordorf R, Cornara S, Somaschini A, De Martino S, De Ferrari GM. De Winter Pattern Caused by a Large Diagonal Branch Culprit Lesion. J Invasive Cardiol. 2021;33:E230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Ni H, Zhai C, Pan H. Uncommon culprit artery leading to atypical de winter electrocardiographic changes: a case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2024;24:524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Chen X, Sun Y, Xiang T. de Winter electrocardiographic pattern related to diagonal branch occlusion. Coron Artery Dis. 2021;32:593-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Alahmad Y, Sardar S, Swehli H. De Winter T-wave Electrocardiogram Pattern Due to Thromboembolic Event: A Rare Phenomenon. Heart Views. 2020;21:40-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7073] [Cited by in RCA: 6936] [Article Influence: 867.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 98. | Rao SV, O'Donoghue ML, Ruel M, Rab T, Tamis-Holland JE, Alexander JH, Baber U, Baker H, Cohen MG, Cruz-Ruiz M, Davis LL, de Lemos JA, DeWald TA, Elgendy IY, Feldman DN, Goyal A, Isiadinso I, Menon V, Morrow DA, Mukherjee D, Platz E, Promes SB, Sandner S, Sandoval Y, Schunder R, Shah B, Stopyra JP, Talbot AW, Taub PR, Williams MS. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI Guideline for the Management of Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2025;151:e771-e862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 226.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Xiao H, Mei Z, Feifei Z, Huiliang L, Shuren L. Poor efficacy of intravenous thrombolysis in de Winter pattern: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e36270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Samadov F, Akaslan D, Cincin A, Tigen K, Sarı I. Acute proximal left anterior descending artery occlusion with de Winter sign. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:110.e1-110.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Mehrpooya M, Salehi A, Sherafati A. Acute thrombotic occlusion of proximal left anterior descending artery without ST-elevation (de Winter sign) in electrocardiogram: A case report. Adv J Emerg Med. 2020;4:e93. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 102. | Bayés de Luna A, Cino JM, Pujadas S, Cygankiewicz I, Carreras F, Garcia-Moll X, Noguero M, Fiol M, Elosua R, Cinca J, Pons-Lladó G. Concordance of electrocardiographic patterns and healed myocardial infarction location detected by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:443-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Tiyantara MS, Herdianto D. The de Winter Pattern as Pre-Anterior ST-Elevation-Myocardial-Infarction. “An Evolution Sequence”: A Case Report. Indonesian J Cardiol. 2021;42:58-62. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 104. | García-Izquierdo E, Parra-Esteban C, Mirelis JG, Fernández-Lozano I. The de Winter ECG Pattern in the Absence of Acute Coronary Artery Occlusion. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34:209.e1-209.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Vidal Porciuncula E, Gonçalves Lyra F, Garoni Peternelli D, Carvalho AC, De Marqui Moraes PI. Alteração EletrocardiogrÁFica Incomum Por Oclusão De CoronÁRia Descendente Anterior: Padrão “De Winter”. Rev Soc Cardiol Estado de São Paulo. 2019;29:94-96. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 106. | Molina-Lopez VH, Ortiz-Mendiguren D, Diaz-Rodriguez PE, Ortiz-Troche S, Cordova-Perez F, Ortiz-Cartagena I. Unusual Presentation of De Winter's Sign Due to Bezold-Jarisch Reflex in a Patient With Severe Aortic Valve Stenosis. Cureus. 2024;16:e61563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Chen S, Wang H, Huang L. The presence of De Winter electrocardiogram pattern following elective percutaneous coronary intervention in a patient without coronary artery occlusion: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e18656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Ando H, Shimoda M, Ohashi H, Nakano Y, Takashima H, Amano T. de Winter Electrocardiogram Pattern Due to Vasospastic Angina. Circ J. 2020;84:1884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Zhang Q, Yang DD, Xu YF, Qiu YG, Zhang ZY. De Winter electrocardiogram pattern due to type A aortic dissection: a case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022;22:150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 110. | Dai W, Jiang Z, Zhong G. De Winter sign associated with roes-induced anaphylactic shock: a new electrocardiographic manifestation of Kounis syndrome. J Xiangya Med. 2021;6:9. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 111. | Daas MA, Almasaabi MA, Abdrabou EM, Elmahal M, Mahdi AO, Tello EA, Mahdi O, Alayyaf AE, Aladwani AJ, Ramadan MM. A case report of complex acute coronary syndrome presentation: Plaque rupture and mild coronary artery ectasia presenting as de Winter T-waves morphing into anterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction in a young adult male. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2025;13:2050313X251331733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Li Q, Cheng S, Chen Z, Hong X, Wang B, Ouyang M. Pheochromocytoma presenting with chest pain, heart failure and elevated pancreatic enzymes. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2025;2025:omae202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Wei W, Zhu R, Liu T. Huge Diagnostic and Treatment Challenges-A Confusing Coexistence. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:1095-1096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Prasad RM, Al-Abcha A, Elshafie A, Radwan YA, Baloch ZQ, Abela GS. The rare presentation of the de Winter's pattern: Case report and literature review. Am Heart J Plus. 2021;3:100013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Brady WJ, Erling B, Pollack M, Chan TC. Electrocardiographic manifestations: acute posterior wall myocardial infarction. J Emerg Med. 2001;20:391-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |