Published online Feb 26, 2026. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.114265

Revised: October 2, 2025

Accepted: December 10, 2025

Published online: February 26, 2026

Processing time: 147 Days and 11.3 Hours

New-onset atrial fibrillation (NOAF) is observed in 2%-21% of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and is associated with adverse outcomes, including increased mortality, heart failure, and stroke. Despite guideline recommendations the long-term role of oral anticoagulant (OAC) therapy in this population remains unclear. Most randomized clinical trials evaluating anticoagulation excluded patients with NOAF following AMI, creating a gap in high-quality evidence. Whether long-term OAC therapy improves prognosis without excess bleeding risk in this setting remains uncertain. We hypothesized that OAC use reduces mortality in patients with NOAF complicating AMI.

To determine the efficacy and safety of long-term OAC therapy in patients with NOAF during AMI.

We conducted a systematic review of the PubMed and eLIBRARY databases through March 2025 following predefined patient, intervention, comparison, outcome criteria. Eligible observational studies included patients with AMI and newly detected atrial fibrillation during the index event who were prescribed OAC therapy with available outcome data. Methodological quality was evaluated using the Quality in Prognosis Studies tool. Pooled hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using a random-effects model. Primary outcomes were all-cause mortality, ischemic stroke, and major bleeding.

Four studies including 7158 patients with a follow-up range of 1.0-8.6 years were analyzed. Long-term OAC therapy significantly reduced all-cause mortality (25.3% vs 33.6%; HR = 0.75; 95%CI: 0.64-0.90; P = 0.001) with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). There was no significant reduction in ischemic stroke (3.5% vs 4.2%; HR = 0.82; 95%CI: 0.57-1.17; P = 0.26). Major or hospitalization-requiring bleeding was not increased (4.8% vs 4.1%; HR = 1.15; 95%CI: 0.89-1.47; P = 0.28). The cohorts largely reflected vitamin K antagonist-based therapy with clopidogrel. Stroke prevention benefit was not statistically significant, and data specific to direct OACs remain sparse.

Long-term OAC therapy after AMI with NOAF reduced mortality without consistent bleeding increase though findings mainly reflect warfarin-era practice and not direct OACs.

Core Tip: New-onset atrial fibrillation during acute myocardial infarction is a frequent and high-risk complication, yet evidence for optimal long-term management is limited due to exclusion from randomized trials. This meta-analysis of 7158 patients demonstrated that oral anticoagulant therapy reduced all-cause mortality by 25% without increasing major bleeding risk. The findings support guideline recommendations to consider anticoagulation in this population, particularly in patients with higher thromboembolic risk. Importantly, the results highlighted the urgent need for randomized trials focusing on direct oral anticoagulants and transient atrial fibrillation in the context of acute myocardial infarction.

- Citation: Pereverzeva KG, Glenza A, Yakushin SS. Oral anticoagulant therapy and outcomes in new-onset atrial fibrillation during acute myocardial infarction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Cardiol 2026; 18(2): 114265

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v18/i2/114265.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.114265

Among patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI), new-onset atrial fibrillation (NOAF) is observed in 2%-21% of cases[1-3]. The variability in reported incidence rates may be attributed to differences in study populations, follow-up periods, diagnostic methods, and definitions of NOAF. More recent investigations conducted within the framework of routine percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) strategies in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) report an incidence of 4%-5% (ranging from 3.6% to 5.3%)[4-6]. Approximately half of NOAF cases occur within 30 days of the index AMI[7]. Notably, the temporal distribution of NOAF is heterogeneous: 30% of cases develop during or within 2 days after AMI; 16% between 3 days and 30 days; and 54% manifest beyond 30 days with a gradual decline during long-term follow-up[7].

The prognostic impact of NOAF complicating AMI remains controversial. Several studies have demonstrated higher in-hospital mortality as well as increased 30-day and 1-year mortality rates[3,8]. In patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) complicated by NOAF, the risks of cardiogenic shock, congestive heart failure, and stroke are significantly elevated[9,10]. Conversely, other studies have failed to establish such associations[6], likely due to differences in follow-up duration and in the clinical characteristics of both atrial fibrillation (AF), including timing of onset, recurrence, duration of paroxysms, and symptom burden[11-13], and AMI itself, such as disease course, treatment strategies, and patient-related factors[14-16].

Nevertheless, the most recently published and (to the best of the authors’ knowledge) largest review on the prognostic significance of NOAF in AMI concluded that NOAF is associated with increased risks of stroke, higher mortality rates, heart failure, cardiogenic shock, ventricular arrhythmias, and major adverse cardiovascular events. NOAF is a marker of poorer in-hospital prognosis compared with patients with a history of prior AF. Both NOAF and pre-existing AF are strong predictors of ischemic stroke[17]. Importantly, this review did not differentiate between subtypes of NOAF, such as transient, recurrent, or persistent AF. In this context, it is noteworthy that transient AF leads to AF-related rehospitalization within the first year after AMI in 36.7%-37.2% of cases[10,18], often evolving into recurrent AF. Furthermore, transient AF in patients with AMI is associated with a worse prognosis[11,19,20], irrespective of subsequent AF recurrence[10]. The 2023 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on ACS emphasize that “patients with ACS and documented AF of any duration have worse short-term and long-term outcomes compared with those in sinus rhythm”[21].

However, to date, it remains unclear whether long-term anticoagulant therapy provides clinical benefit in patients with NOAF that develops during AMI. This uncertainty arises from the fact that in randomized clinical trials (RCTs), particularly those investigating direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), AF secondary to a reversible condition was generally an exclusion criterion, and AMI was explicitly listed among such conditions (e.g., in the rivaroxaban trial)[22]. In other cases, even when no explicit exclusion was stated, the inclusion criteria indirectly precluded AMI[23-25]. Similarly, in studies evaluating the efficacy of dual or triple antithrombotic therapy in patients with AF and AMI, NOAF was also considered an exclusion criterion[26-28].

Thus, at present there is no robust evidence supporting the use of long-term oral anticoagulant (OAC) therapy in patients with NOAF occurring in the setting of AMI. Nevertheless, the current clinical guidelines of the Russian Federation explicitly recommend that “in patients with non-ST-segment elevation (NSTE) ACS/STEMI[29,30], and NOAF during the acute phase of the disease, long-term OAC therapy should be considered, with comprehensive reassessment of the entire antithrombotic regimen depending on the risk of thromboembolic complications according to the CHA2DS2-VASc score and bleeding risk assessed by the HAS-BLED score (class IIa, level of evidence C)”.

Importantly, in the most recent version of the Russian clinical guidelines on NSTE-ACS/STEMI (2024)[29,30], NOAF occurring during the acute phase of AMI is addressed separately from other forms of AF. In contrast, the 2020 guidelines on NSTE-ACS and STEMI did not make such a distinction[31,32]. It is noteworthy that the recommendation stating “patients with NOAF during the acute phase of STEMI should receive long-term OAC therapy in accordance with thromboembolic risk assessed by the CHA2DS2-VASc score, while also considering concomitant antiplatelet therapy (class IIa, level of evidence C)” was first introduced in the 2017 ESC guidelines on STEMI[33]. In the years since then, the use of OAC in this patient population would be expected to become routine clinical practice. However, real-world data suggest that the prescription rate of OAC in such patients remains suboptimal[10].

In the most recent 2023 ESC guidelines on ACS, the recommendation is reiterated: “In patients with NOAF docu

In the 2025 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/American College of Emergency Physicians/National Association of Emergency Medical Services Physicians/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions guidelines on ACS, it is stated that in patients with non-STEMI or STEMI who require OAC, short-term triple antithrombotic therapy should be preferred, followed by transition to dual therapy. However, these guidelines do not provide specific considerations regarding NOAF[35].

In the absence of high-level evidence regarding the benefits and risks of long-term anticoagulation in NOAF associated with AMI, the present meta-analysis of observational studies was intended to address this critical gap in knowledge. Its purpose is to quantitatively assess the efficacy and safety of long-term OAC therapy in this patient population through synthesis of the available clinical data.

Two investigators independently conducted a systematic search of electronic databases up to March 2025. Relevant articles were identified in PubMed and eLIBRARY using the following search query: (“AMI” OR “acute myocardial infarction” OR “ACS” OR “acute coronary syndrome” OR “ST-elevation myocardial infarction” OR “STEMI” OR “non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction” OR “NSTEMI”) AND (“new-onset atrial fibrillation” OR “de novo atrial fibrillation” OR “first-time detected atrial fibrillation” OR “transient atrial fibrillation”).

In eLIBRARY, the search was performed within article and book titles, abstracts, and keywords without temporal restrictions and was carried out with morphological variations considered. In PubMed the search was restricted to articles published in English, whereas in eLIBRARY, studies not published in Russian or English were manually excluded.

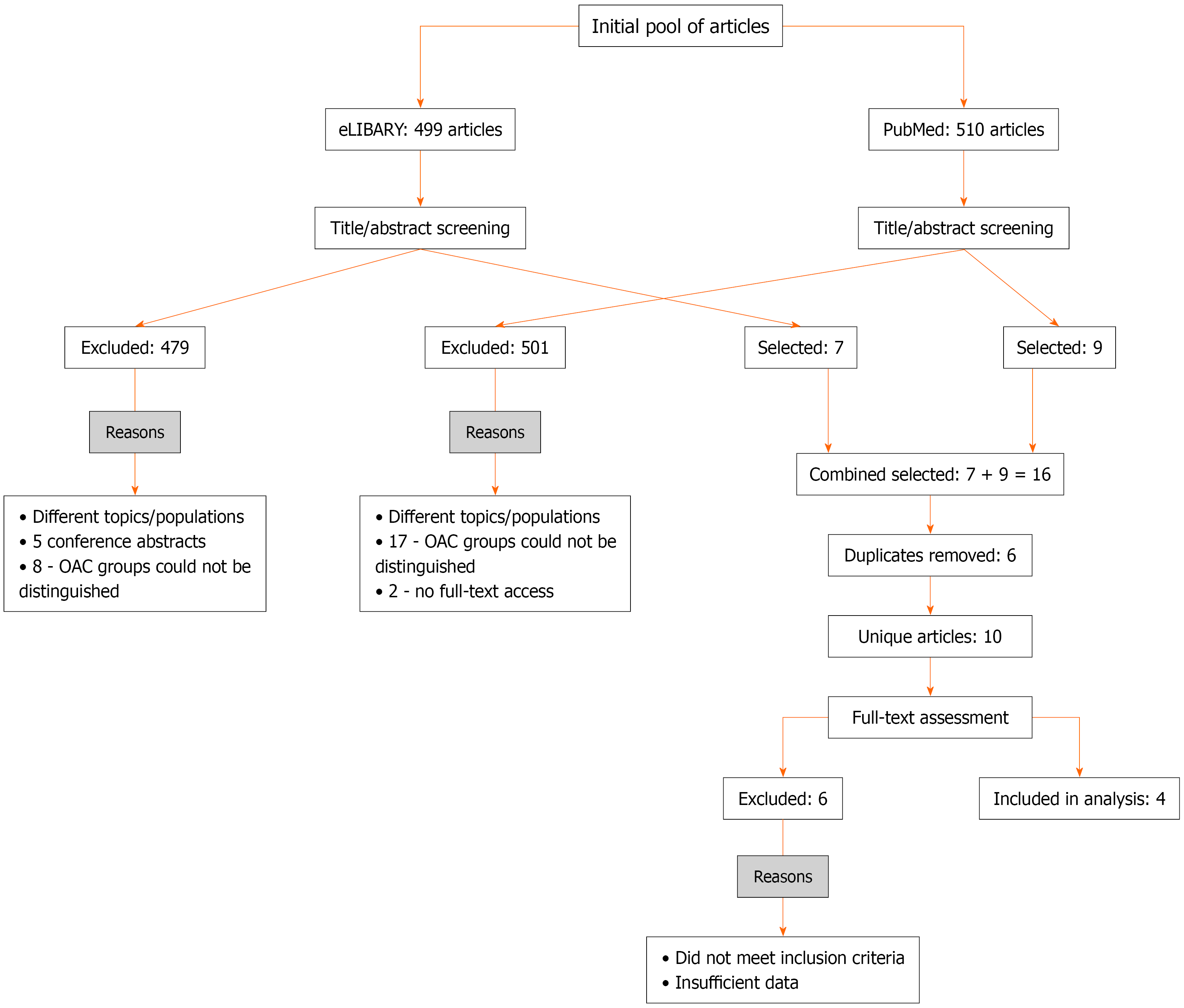

After screening titles and abstracts, two authors independently performed full-text assessments to determine whether the studies met the eligibility criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third investigator. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) AMI; (2) NOAF occurring during the index AMI; (3) Administration of anticoagulant therapy; (4) Availability of outcome data related to such treatment; and (5) Access to the full-text article. Definitions of NOAF varied across studies: Transient in-hospital AF; de novo AF at or during hospitalization; new AF within 30 days post-STEMI; and first-time AF in survivors of ACS. Follow-up began after discharge or after 30 days in most cohorts, thereby excluding acute-phase mortality. The study selection algorithm is presented in Figure 1. To focus on long-term outcomes, studies reporting only in-hospital mortality in the acute phase of myocardial infarction were excluded. For included studies analyses began after discharge or when available after the initial 30-day period.

Search results in eLIBRARY: During title and abstract screening, 499 articles were identified. Of these 479 addressed other topics and/or patient populations, and 5 were single-page abstracts. In eight studies it was not possible to differentiate patient groups receiving and not receiving OAC.

Search results in PubMed: During title and abstract screening, 510 articles were identified. Of these 482 addressed other topics and/or patient populations. In 17 studies it was not possible to differentiate patient groups receiving and not receiving OAC, and 2 full-text articles were inaccessible.

As a result, 7 articles from eLIBRARY and 9 articles from PubMed were initially eligible. Six of these (eLIBRARY + PubMed) were duplicates. After full-text assessment of 10 unique articles, 4 studies were ultimately included in the final analysis. The data from these studies are presented in Table 1.

| Kayapinar et al[40] | Hofer et al[38] | Madsen et al[39] | Petersen et al[41] | |

| Enrollment years | 2009-2014 | 1996-2009 | 1999-2016 | 2000-2018 |

| Study design | Retrospective single-center cohort study | Retrospective-prospective single-center cohort study | Retrospective single-center cohort study | Retrospective nationwide cohort study (Danish registry data) |

| Follow-up duration | 1 year | Median 8.6 years | 5.8 (3.6-9.3) | 1 year |

| Patients with NOAF (n) | 286 | 149 | 296 | 6427 |

| Incidence | 8.7% | 10.9% | 3.7% | 4.0% |

| Definition of NOAF | No AF at admission; AF episode during hospitalization, spontaneously converted or successfully cardioverted (pharmacological/electrical) before discharge without recurrence | New AF episode at admission or during AMI in patients without prior AF | AF diagnosed within 30 days after STEMI in patients without prior AF | AF diagnosed at admission with ACS in patients without prior AF |

| Forms of NOAF | 100% transient AF. Spontaneous rhythm restoration: 118 patients (41.3%). Pharmacological cardioversion: 121 patients (42.3%). Electrical cardioversion: 47 patients (16.4%) | Paroxysmal: 67.1% (100 of 149), AF episodes terminated before discharge. Persistent: 32.9% (49 of 149), AF persisted at discharge | Not reported | Not reported |

| Patients with STEMI | 100% | 59.1% | 100% | Not reported (AMI in 90.0%) |

| PCI | 100% | 50.3% | 100% | 26.3% |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 2.85 ± 1.8 | 4 (3-5) | CHA2DS2-VASc ≥ 2: 92.6% | 3 (2-5) |

| HAS-BLED score | 2.75 ± 1.3 | Not reported | ≥ 3 in 57.1% | 1 (0-2) |

| Patients on OAC | 40.6% | 52.3% | 38.2% | 38.9% |

| Anticoagulant therapy | Warfarin | Warfarin | Warfarin (74.3%), DOACs (25.7%) | Warfarin and DOACs (distribution not specified) |

| All-cause mortality and OAC effect | 18.9%; HR = 1.06 (95%CI: 0.52-1.95, P = 0.880) | Not reported | 44.3%; HR = 0.69 (95%CI: 0.47-1.00, P = 0.049) | 18.0%; HR = 0.72 (95%CI: 0.57-0.91) |

| Cardiovascular mortality and OAC effect | Not reported | 62.4%; triple antithrombotic therapy: HR = 0.86 (95%CI: 0.45-0.92, P = 0.012). Dual antithrombotic therapy: HR = 0.97 (95%CI: 0.65-1.57, P = 0.346). Estimated HR (warfarin): 0.90 (95%CI: 0.68-1.15) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Ischemic stroke and OAC effect | 10.1%; HR = 1.39 (95%CI: 0.57-3.18, P = 0.459) | Fatal cases only: 6.0% | 11.1%; HR = 0.70 (95%CI: 0.33-1.49, P = 0.35) | 1.9%; HR = 0.78 (95%CI: 0.41-1.47) |

| Major bleeding/bleeding requiring hospitalization and OAC effect | 2.8%; HR = 3.37 (95%CI: 1.76-10.04, P = 0.012) | 2.6%; not reported | 19.6%; HR = 1.31 (95%CI: 0.75-2.27, P = 0.34) | 5.7%; HR = 1.20 (95%CI: 0.87-1.65) |

| Minor bleeding and OAC effect | 7.0%; HR = 2.28 (95%CI: 1.78-5.81, P = 0.024) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

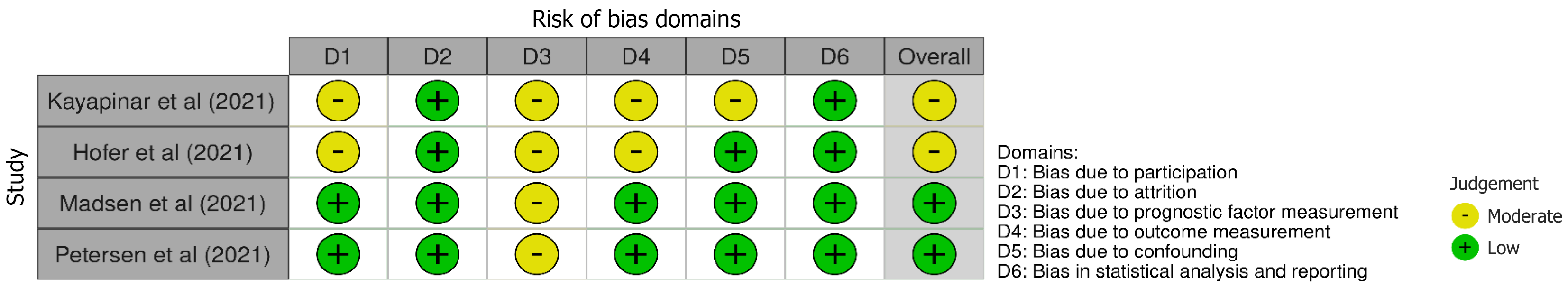

The validity and methodological quality of non-randomized studies were evaluated using the Quality in Prognosis Studies tool[36], which comprises six domains of potential bias: (1) Study participation; (2) Study attrition; (3) Prognostic factor measurement; (4) Outcome measurement; (5) Study confounding; and (6) Statistical analysis and reporting[37]. None of the included studies were excluded based on risk of bias; all were judged to have low or moderate risk of bias (Figure 2).

Statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager, version 5.4.1 (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020). Meta-analysis was conducted using a random-effects model with the inverse variance method. Statistical heterogeneity across studies was assessed using the χ2-based Q test and the I2 statistic. Interpretation of heterogeneity followed the Cochrane Collaboration’s recommendations: I2 = 0%-40% indicated insignificant heterogeneity; 30%-60% indicated moderate heterogeneity; 50%-90% indicated substantial heterogeneity; and 75%-100% indicated considerable heterogeneity.

For survival outcomes the natural logarithm of adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with corresponding SE was used as the input for meta-analysis. SE values were calculated according to the following formula: SE = {ln[upper bound 95% confidence interval (CI)] – ln(lower bound 95%CI)}/(2 × 1.96) in which upper bound and lower bound represent the upper and lower boundaries of the 95%CI for HR, and 1.96 is the critical t value for the 95%CI[37]. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In the study by Hofer et al[38], HRs comparing outcomes between patients receiving and not receiving OAC were not reported. However, HRs were provided for dual antithrombotic therapy (antiplatelet agent plus OAC) vs dual antiplatelet therapy and for triple antithrombotic therapy (two antiplatelets plus OAC) vs dual antiplatelet therapy. Based on these data the HR was calculated in Review Manager and was found to be 0.90 (95%CI: 0.68-1.15, P = 0.47).

A total of 7158 patients were included in the analysis with follow-up ranging from 1.0 year to 8.6 years.

Notably, there were differences in the definitions and diagnostic approaches to NOAF. In the study by Madsen et al[39], NOAF was defined as AF occurring within 30 days after STEMI in patients without a prior history of AF, whereas Kayapinar et al[40] included exclusively patients with STEMI and transient AF. The registries of Madsen et al[39] and Petersen et al[41] included both transient and persistent forms of AF in patients with AMI. The registry of Madsen et al[39] enrolled only STEMI patients while the study by Hofer et al[38] included approximately 59% of patients with STEMI and AF of varying duration.

The proportion of patients receiving OAC ranged from 36.4% to 52.3%. Most patients were treated with warfarin except in the registries of Madsen et al[39] and Petersen et al[41] in which DOACs were also partially utilized.

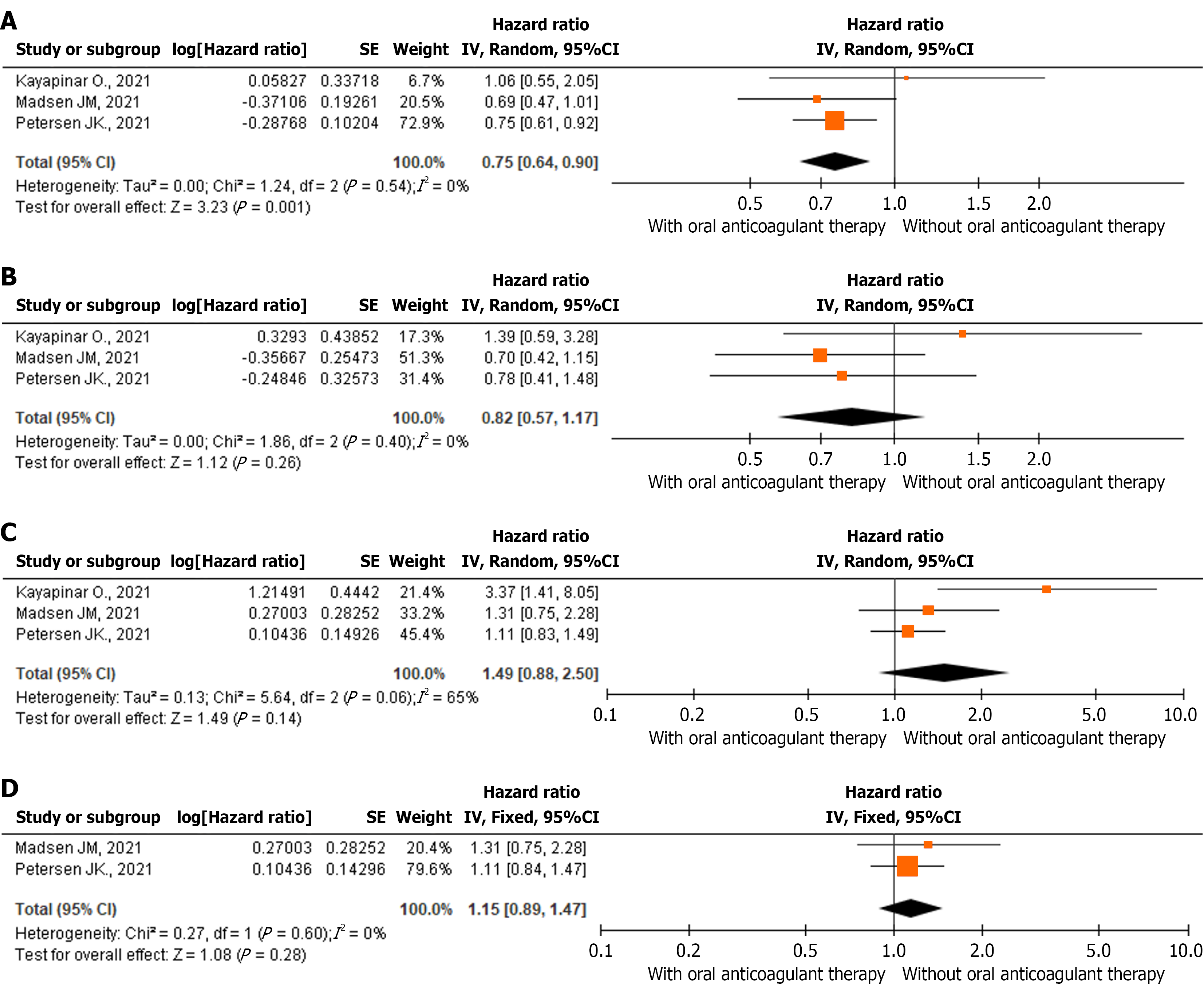

According to the forest plot (Figure 3A), OAC use was associated with a statistically significant 1.33-fold reduction in all-cause mortality risk among patients with NOAF and AMI compared with those not receiving OAC therapy (HR = 0.75, 95%CI: 0.64-0.90, P = 0.001). Cause-specific mortality (cardiovascular vs non-cardiovascular) was available only in Hofer et al[38], whereas the other studies reported all-cause mortality only. Antithrombotic regimens were largely vitamin K antagonists plus clopidogrel. Hofer et al[38] demonstrated lower cardiovascular mortality with triple therapy (vitamin K antagonists + aspirin + clopidogrel) in de novo AF, whereas Kayapinar et al[40] found increased bleeding without efficacy benefit for vitamin K antagonists plus dual antiplatelets in transient AF. Ticagrelor and prasugrel were not in use in these registries. The heterogeneity among included studies was low and statistically insignificant (I2 = 0%, P = 0.54).

According to the forest plot (Figure 3B), OAC use did not reduce the risk of ischemic stroke in patients with NOAF and AMI. The HR was 0.82 (95%CI: 0.57-1.17, P = 0.26). Stroke prevention benefits with OAC were inconsistent and not statistically significant across the cohorts, likely reflecting limited statistical power. Heterogeneity among the included studies was low and statistically insignificant (I2 = 0%, P = 0.40). The absence of a protective effect on ischemic stroke may be attributed to limited statistical power and relatively short follow-up duration.

According to the forest plot (Figure 3C), OAC use did not increase the risk of major bleeding or bleeding requiring hospitalization in patients with NOAF and AMI. The HR was 1.49 (95%CI: 0.88-2.50, P = 0.14). Heterogeneity among the included studies was substantial but statistically insignificant (I2 = 65%, P = 0.06).

The bleeding outcomes proved sensitive to the inclusion of the study by Kayapinar et al[40] in which the focus on transient AF and the low event rate may have overestimated the risk of bleeding. After excluding this study, which analyzed only transient AF, the pooled HR for major bleeding and bleeding requiring hospitalization was 1.15 (95%CI: 0.89-1.47, P = 0.28) with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.60; Figure 3D). In contrast Kayapinar et al[40] found a significant increase in both major and minor bleeding when warfarin was added to dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with transient AF after STEMI. These results highlighted that triple therapy may confer excess bleeding risk without a corresponding ischemic benefit in this specific subgroup. Excluding this study eliminated heterogeneity and strengthened the conclusion that OAC does not significantly increase the risk of bleeding. Thus, the findings confirm that OAC does not raise the risk of bleeding in mixed populations of patients with persistent and/or transient AF.

The present meta-analysis demonstrated that long-term OAC therapy in patients with NOAF and AMI was associated with a significant 25% reduction in mortality risk (HR = 0.75, 95%CI: 0.64-0.90, P = 0.001) without an increased risk of major bleeding or bleeding requiring hospitalization. This finding supports the rationale of the 2024 Russian guidelines on NSTE-ACS/STEMI[29,30], which recommend considering long-term OAC therapy in this patient population. Our findings reflected primarily warfarin-era practice as DOAC uptake was minimal and not analyzed separately. Thus, agent-specific effects could not be determined.

Of particular note, the meta-analysis revealed no significant impact of OAC on the risk of ischemic stroke (Figure 3B). This may be attributed to limited statistical power and relatively short follow-up in two of the three studies included in this outcome analysis. Another possible explanation is the overall low incidence of ischemic stroke as illustrated by the largest study included, Petersen et al[41], in which the rate was only 1.9%.

Interpretation of these results was complicated by the heterogeneity of patients with NOAF across the included studies. Several investigations focused solely on patients with STEMI while diagnostic criteria for AF varied (transient, persistent, timing of onset). The predominance of warfarin use (74%-100%) further limits the generalizability of findings to contemporary DOACs. Moreover, insufficient data were available to assess the impact of OAC on long-term outcomes beyond 5 years.

Nevertheless, in the absence of RCTs specifically addressing NOAF in AMI, the results of this meta-analysis support the clinical rationale for prescribing OAC to patients with NOAF and AMI, particularly in cases of recurrent or persistent AF and in patients with elevated CHA2DS2-VASc scores. Although the studies by Hofer et al[38], Madsen et al[39], and Petersen et al[41] did not allow for separate analysis of transient AF cohorts and Kayapinar et al[40] failed to demonstrate a benefit of OAC in this subgroup, we believe that despite the need for careful risk assessment OAC therapy should be considered in most patients with transient AF in routine clinical practice, particularly in those with a high CHA2DS2-VASc score (≥ 2 in males, ≥ 3 in females) and low bleeding risk (HAS-BLED). Discontinuation of anticoagulation may only be considered in selected cases, based on the brevity and timing of the arrhythmia episode together with individualized assessment of both thromboembolic (CHA2DS2-VASc) and hemorrhagic (HAS-BLED) risk. The antiplatelet background varied with only two studies comparing dual vs triple therapy, both clopidogrel-based. Outcomes stratified by CHA2DS2-VASc, left atrial size, or left ventricle ejection fraction were not reported. Timing of NOAF differed (in-hospital, ≤ 30 days, post-discharge), preventing harmonized stratified analyses.

Contemporary AF-PCI trials (PIONEER-AF, RE-DUAL PCI, AUGUSTUS)[27,28] showed that dual therapy with OAC plus clopidogrel significantly reduced bleeding compared with OAC-based triple therapy without loss of ischemic protection. These results reinforce guideline recommendations to minimize triple therapy and to prefer clopidogrel as the P2Y12 inhibitor of choice. However, these trials did not evaluate outcomes specifically in patients with NOAF during AMI. There is a clear need for dedicated RCTs comparing DOACs with placebo or antiplatelet therapy in patients with NOAF with stratification according to AF duration, timing of onset, AMI type, and concomitant antithrombotic regimens. Such trials are particularly warranted for transient NOAF and would provide crucial evidence to define the optimal composition and duration of antithrombotic therapy while minimizing iatrogenic risks.

Limitations of this meta-analysis included the small volume of available data (four studies with 7158 patients), reducing the statistical power and robustness of conclusions. Considerable clinical heterogeneity across studies, including variable definitions of NOAF (transient AF, AF within 30 days, AF at admission), differences in AMI subtypes, and follow-up duration ranging from 1.0 year to 8.6 years also limited our study. The predominance of warfarin use (74%-100%) limits extrapolation of findings to contemporary DOACs. There is also a risk of bias, particularly as an estimated HR was used for comparison of outcomes between OAC and non-OAC groups in the study by Hofer et al[38]. We were unable to stratify outcomes by DOAC vs warfarin, by CHA2DS2-VASc score, or by cardiac structural parameters. Cause-specific mortality was available in only one study. These limitations underscore the need for dedicated randomized trials in the DOAC era.

Long-term OAC therapy in patients with NOAF and AMI was associated with a significant 25% reduction in all-cause mortality without an increased risk of major bleeding or bleeding requiring hospitalization, supporting the rationale for OAC use in this patient population. The available evidence largely reflects warfarin-based treatment given together with clopidogrel and cannot be generalized to DOACs. Future RCTs are needed to clarify the role of modern OAC strategies, to determine the effects according to the timing of AF onset, and to assess outcomes across different stroke risk categories and cardiac structural characteristics.

| 1. | Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Boriani G, Castella M, Dan GA, Dilaveris PE, Fauchier L, Filippatos G, Kalman JM, La Meir M, Lane DA, Lebeau JP, Lettino M, Lip GYH, Pinto FJ, Thomas GN, Valgimigli M, Van Gelder IC, Van Putte BP, Watkins CL; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:373-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3176] [Cited by in RCA: 6867] [Article Influence: 1373.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Biccirè FG, Tanzilli G, Prati F, Sammartini E, Gelfusa M, Celeski M, Budassi S, Barillà F, Lip GYH, Pastori D. Prediction of new onset atrial fibrillation in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention using the C2HEST and mC2HEST scores: A report from the multicenter REALE-ACS registry. Int J Cardiol. 2023;386:45-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sadat B, Al Taii H, Sabayon M, Narayanan CA. Atrial Fibrillation Complicating Acute Myocardial Infarction: Prevalence, Impact, and Management Considerations. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2024;26:313-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rene AG, Généreux P, Ezekowitz M, Kirtane AJ, Xu K, Mehran R, Brener SJ, Stone GW. Impact of atrial fibrillation in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (from the HORIZONS-AMI [Harmonizing Outcomes With Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction] trial). Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:236-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lopes RD, Elliott LE, White HD, Hochman JS, Van de Werf F, Ardissino D, Nielsen TT, Weaver WD, Widimsky P, Armstrong PW, Granger CB. Antithrombotic therapy and outcomes of patients with atrial fibrillation following primary percutaneous coronary intervention: results from the APEX-AMI trial. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2019-2028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zeymer U, Annemans L, Danchin N, Pocock S, Newsome S, Van de Werf F, Medina J, Bueno H. Impact of known or new-onset atrial fibrillation on 2-year cardiovascular event rate in patients with acute coronary syndromes: results from the prospective EPICOR Registry. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2019;8:121-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jabre P, Jouven X, Adnet F, Thabut G, Bielinski SJ, Weston SA, Roger VL. Atrial fibrillation and death after myocardial infarction: a community study. Circulation. 2011;123:2094-2100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Saleh M, Coleman K, Fishbein J, Gandomi A, Yang B, Kossack A, Varrias D, Jauhar R, Lasic Z, Kim M, Mihelis E, Ismail H, Sugeng L, Singh V, Epstein LM, Kuvin J, Mountantonakis SE. In-hospital outcomes and postdischarge mortality in patients with acute coronary syndrome and atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2024;21:1658-1668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yu S, Li C, Guo H. Oral anticoagulant therapy for patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation following acute myocardial infarction: A narrative review. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:1046298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Petersen JK, Butt JH, Yafasova A, Torp-Pedersen C, Sørensen R, Kruuse C, Vinding NE, Gundlund A, Køber L, Fosbøl EL, Østergaard L. Prognosis and antithrombotic practice patterns in patients with recurrent and transient atrial fibrillation following acute coronary syndrome: A nationwide study. Int J Cardiol. 2024;407:132017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Podolecki T, Lenarczyk R, Kowalczyk J, Jedrzejczyk-Patej E, Swiatkowski A, Chodor P, Sedkowska A, Streb W, Mitrega K, Kalarus Z. Significance of Atrial Fibrillation Complicating ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120:517-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Asanin M, Vasiljevic Z, Matic M, Vujisic-Tesic B, Arandjelovic A, Marinkovic J, Ostojic M. Outcome of patients in relation to duration of new-onset atrial fibrillation following acute myocardial infarction. Cardiology. 2007;107:197-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Asanin MR, Vasiljevic ZM, Matic MD, Mrdovic IB, Perunicic JP, Matic DP, Vujisic-Tesic BD, Stankovic SD, Matic DM, Ostojic MC. The long-term risk of stroke in patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated with new-onset atrial fibrillation. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32:467-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang CL, Chen PC, Juang HT, Chang CJ. Adverse Outcomes Associated with Pre-Existing and New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Cardiol Ther. 2019;8:117-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ben Halima M, Yaakoubi W, Boudiche S, Rekik B, Zghal Mghaieth F, Ouali S, Mourali MS. New-onset atrial fibrillation after acute coronary syndrome: prevalence and predictive factors. Tunis Med. 2022;100:114-121. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Li J, Becker R, Rauch B, Schiele R, Schneider S, Riemer T, Diller F, Gohlke H, Gottwik M, Steinbeck G, Sabin G, Katus HA, Senges J; OMEGA Study Group. Usefulness of heart rate to predict one-year mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation and acute myocardial infarction (from the OMEGA trial). Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:811-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bazoukis G, Hui JMH, Saplaouras A, Efthymiou P, Vassiliades A, Dimitriades V, Hui CTC, Li SS, Jamjoom AO, Liu T, Letsas KP, Efremidis M, Tse G. The impact of new-onset atrial fibrillation in the setting of acute coronary syndrome. J Cardiol. 2025;85:186-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gundlund A, Kümler T, Bonde AN, Butt JH, Gislason GH, Torp-Pedersen C, Køber L, Olesen JB, Fosbøl EL. Comparative thromboembolic risk in atrial fibrillation with and without a secondary precipitant-Danish nationwide cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e028468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bishara R, Telman G, Bahouth F, Lessick J, Aronson D. Transient atrial fibrillation and risk of stroke after acute myocardial infarction. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106:877-884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Salerno N, Ielapi J, Cersosimo A, Leo I, Sabatino J, De Rosa S, Sorrentino S, Torella D. Incidence and outcomes of transient new-onset atrial fibrillation complicating acute coronary syndromes: results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2025;10:652-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, Barbato E, Berry C, Chieffo A, Claeys MJ, Dan GA, Dweck MR, Galbraith M, Gilard M, Hinterbuchner L, Jankowska EA, Jüni P, Kimura T, Kunadian V, Leosdottir M, Lorusso R, Pedretti RFE, Rigopoulos AG, Rubini Gimenez M, Thiele H, Vranckx P, Wassmann S, Wenger NK, Ibanez B; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:3720-3826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 2708] [Article Influence: 902.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, Breithardt G, Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Piccini JP, Becker RC, Nessel CC, Paolini JF, Berkowitz SD, Fox KA, Califf RM; ROCKET AF Investigators. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6519] [Cited by in RCA: 7042] [Article Influence: 469.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 23. | Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, Al-Khalidi HR, Ansell J, Atar D, Avezum A, Bahit MC, Diaz R, Easton JD, Ezekowitz JA, Flaker G, Garcia D, Geraldes M, Gersh BJ, Golitsyn S, Goto S, Hermosillo AG, Hohnloser SH, Horowitz J, Mohan P, Jansky P, Lewis BS, Lopez-Sendon JL, Pais P, Parkhomenko A, Verheugt FW, Zhu J, Wallentin L; ARISTOTLE Committees and Investigators. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:981-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6075] [Cited by in RCA: 6679] [Article Influence: 445.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 24. | Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, Murphy SA, Wiviott SD, Halperin JL, Waldo AL, Ezekowitz MD, Weitz JI, Špinar J, Ruzyllo W, Ruda M, Koretsune Y, Betcher J, Shi M, Grip LT, Patel SP, Patel I, Hanyok JJ, Mercuri M, Antman EM; ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 Investigators. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2093-2104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4144] [Cited by in RCA: 3907] [Article Influence: 300.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, Pogue J, Reilly PA, Themeles E, Varrone J, Wang S, Alings M, Xavier D, Zhu J, Diaz R, Lewis BS, Darius H, Diener HC, Joyner CD, Wallentin L; RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139-1151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7917] [Cited by in RCA: 8189] [Article Influence: 481.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gibson CM, Mehran R, Bode C, Halperin J, Verheugt FW, Wildgoose P, Birmingham M, Ianus J, Burton P, van Eickels M, Korjian S, Daaboul Y, Lip GY, Cohen M, Husted S, Peterson ED, Fox KA. Prevention of Bleeding in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing PCI. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2423-2434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1049] [Cited by in RCA: 1159] [Article Influence: 115.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Cannon CP, Bhatt DL, Oldgren J, Lip GYH, Ellis SG, Kimura T, Maeng M, Merkely B, Zeymer U, Gropper S, Nordaby M, Kleine E, Harper R, Manassie J, Januzzi JL, Ten Berg JM, Steg PG, Hohnloser SH; RE-DUAL PCI Steering Committee and Investigators. Dual Antithrombotic Therapy with Dabigatran after PCI in Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1513-1524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 910] [Cited by in RCA: 1005] [Article Influence: 111.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lopes RD, Heizer G, Aronson R, Vora AN, Massaro T, Mehran R, Goodman SG, Windecker S, Darius H, Li J, Averkov O, Bahit MC, Berwanger O, Budaj A, Hijazi Z, Parkhomenko A, Sinnaeve P, Storey RF, Thiele H, Vinereanu D, Granger CB, Alexander JH; AUGUSTUS Investigators. Antithrombotic Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndrome or PCI in Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1509-1524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 663] [Cited by in RCA: 832] [Article Influence: 118.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (13)] |

| 29. | Averkov OV, Harutyunyan GK, Duplyakov DV, Konstantinova EV, Nikulina NN, Shakhnovich RM, Yavelov IS, Yakovlev AN, Abugov SA, Alekyan BG, Aronov DM, Arkhipov MV, Barbarash OL, Boytsov SA, Bubnova MG, Vavilova TV, Vasilyeva EYu, Galyavich AS, Ganyukov VI, Gilyarevsky SR, Golubev EP, Golukhova EZ, Zateyshchikov DA, Karpov YuA, Kosmacheva ED, Lopatin YuM, Markov VA, Merkulov EV, Novikova NA, Panchenko EP, Pevzner DV, Pogosova NV, Prasol DM, Protopopov AV, Skrypnik DV, Tarasov RS, Tereshchenko SN, Ustyugov SA, Khripun AV, Tsebrovskaya EA, Shalaev SV, Shlyakhto EV, Shpektor AV, Yakushin SS. 2024 Clinical practice guidelines for Acute coronary syndrome without ST segment elevation electrocardiogram. Russ J Cardiol. 2025;30:6319. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Averkov OV, Harutyunyan GK, Duplyakov DV, Konstantinova EV, Konstantinova NN, Shakhnovich RM, Yavelov IS, Yakovlev AN, Abugov SA, Alekyan BG, Aronov DM, Arkhipov MV, Barbarash OL, Boytsov SA, Bubnova MG, Vavilova TN, Vasilyeva EY, Galyavich AS, Ganyukov VI, Gilyarevsky SR, Golubev EP, Golukhova EZ, Zateyshchikov DA, Karpov YA, Kosmacheva ED, Lopatin YM, Markov VA, Merkulov EV, Novikova NA, Panchenko EP, Pevzner DV, Pogosova NV, Prasol DM, Protopopov AV, Skrypnik DV, Tarasov RS, Tereshchenko SN, Ustyugov SA, Khripun AV, Tsebrovskaya EA, Shalaev SV, Shlyakhto EV, Shpektor AV, Yakushin SS. 2024 Clinical practice guidelines for Acute myocardial infarction with ST segment elevation electrocardiogram. Russ J Cardiol. 2025;30:6306. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 31. | Barbarash OL, Duplyakov DV, Zateischikov DA, Panchenko EP, Shakhnovich RM, Yavelov IS, Yakovlev AN, Abugov SA, Alekyan BG, Arkhipov MV, Vasilieva EY, Galyavich AS, Ganyukov VI, Gilyarevskyi SR, Golubev EP, Golukhova EZ, Gratsiansky NA, Karpov YA, Kosmacheva ED, Lopatin YM, Markov VA, Nikulina NN, Pevzner DV, Pogosova NV, Protopopov AV, Skrypnik DV, Tereshchenko SN, Ustyugov SA, Khripun AV, Shalaev SV, Shpektor VA, Yakushin SS. 2020 Clinical practice guidelines for Acute coronary syndrome without ST segment elevation. Russ J Cardiol. 2021;26:4449. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Russian Society of Cardiology. 2020 Clinical practice guidelines for Acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Russ J Cardiol. 2020;25:4103. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7073] [Cited by in RCA: 6884] [Article Influence: 860.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, Benjamin EJ, Chyou JY, Cronin EM, Deswal A, Eckhardt LL, Goldberger ZD, Gopinathannair R, Gorenek B, Hess PL, Hlatky M, Hogan G, Ibeh C, Indik JH, Kido K, Kusumoto F, Link MS, Linta KT, Marcus GM, McCarthy PM, Patel N, Patton KK, Perez MV, Piccini JP, Russo AM, Sanders P, Streur MM, Thomas KL, Times S, Tisdale JE, Valente AM, Van Wagoner DR; Peer Review Committee Members. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024;149:e1-e156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1133] [Cited by in RCA: 1439] [Article Influence: 719.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 35. | Rao SV, O'Donoghue ML, Ruel M, Rab T, Tamis-Holland JE, Alexander JH, Baber U, Baker H, Cohen MG, Cruz-Ruiz M, Davis LL, de Lemos JA, DeWald TA, Elgendy IY, Feldman DN, Goyal A, Isiadinso I, Menon V, Morrow DA, Mukherjee D, Platz E, Promes SB, Sandner S, Sandoval Y, Schunder R, Shah B, Stopyra JP, Talbot AW, Taub PR, Williams MS. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI Guideline for the Management of Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2025;151:e771-e862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 186.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, Côté P, Bombardier C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:280-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1713] [Cited by in RCA: 2439] [Article Influence: 187.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4738] [Cited by in RCA: 5080] [Article Influence: 267.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 38. | Hofer F, Kazem N, Hammer A, El-Hamid F, Koller L, Niessner A, Sulzgruber P. Long-term prognosis of de novo atrial fibrillation during acute myocardial infarction: the impact of anti-thrombotic treatment strategies. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2021;7:189-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Madsen JM, Jacobsen MR, Sabbah M, Topal DG, Jabbari R, Glinge C, Køber L, Torp-Pedersen C, Pedersen F, Sørensen R, Holmvang L, Engstrøm T, Lønborg JT. Long-term prognostic outcomes and implication of oral anticoagulants in patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation following st-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2021;238:89-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kayapinar O, Kaya A, Keskin M, Tatlisu MA. Antithrombotic Therapy and Outcomes of Patients With New-Onset Transient Atrial Fibrillation After ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Am J Ther. 2021;28:e30-e40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Petersen JK, Butt JH, Yafasova A, Torp-Pedersen C, Sørensen R, Kruuse C, Vinding NE, Gundlund A, Køber L, Fosbøl EL, Østergaard L. Incidence of ischaemic stroke and mortality in patients with acute coronary syndrome and first-time detected atrial fibrillation: a nationwide study. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:4553-4561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |