Published online Feb 26, 2026. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.113624

Revised: September 30, 2025

Accepted: January 5, 2026

Published online: February 26, 2026

Processing time: 163 Days and 16.8 Hours

The pathophysiology of coronary heart disease (CHD) is significantly influenced by oxidative stress and inflammation, which also modify atherosclerosis. A de

Core Tip: Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a disorder that arises when the heart's arteries are unable to adequately pump blood that is rich in oxygen to the heart. A biomarker is a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacological responses to a therapeutic intervention. Oxidative stress biomarkers include molecules that are altered by interactions with reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the microenvironment and antioxidant system molecules that are altered in response to elevated redox stress. There are many oxidative stress biomarkers in coronary artery disease. Targeting the causes and consequences of ROS by lifestyle changes and pharmacological approaches is part of controlling oxidative stress indicators in CHD.

- Citation: Hussain Rathore AW, Naveed H, Nadeem A, Ishaque A, Iqbal S, Ilyas U, Arooj T, Rafaqat S. Relationship between the oxidative stress biomarkers and coronary heart disease: Pathogenesis to therapeutic aspects. World J Cardiol 2026; 18(2): 113624

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v18/i2/113624.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.113624

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a disorder that arises when the heart's arteries are unable to adequately pump blood that is rich in oxygen to the heart. It is sometimes referred to as coronary artery disease (CAD) or ischemic heart disease (IHD). A leading cause of death globally, CHD is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the accumulation of fatty deposits in the coronary arteries. The incidence of CAD has been growing continuously despite improvements in therapy that have reduced the death rates from CAD[1,2].

The accumulation of plaques (fat, cholesterol, calcium, and other materials) in the walls of arteries throughout the body is known as atherosclerosis. This condition causes the arteries to narrow and harden, which reduces blood flow. Endothelial dysfunction is the first step in atherosclerosis, which is then followed by cholesterol buildup, inflammation, and plaque development. Untreated atherosclerosis can exacerbate arterial blockage, which can lead to myocardial infarction (MI) and IHD. Atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries is the direct cause of CHD[3-5].

A biomarker is a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological pro

Biomarkers that closely match the disease's pathophysiological process are the most promising. Oxidative stress is known to have a part in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease (CVD)[8,9]. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide pho

Oxidative stress biomarkers include molecules that are altered by interactions with ROS in the microenvironment and antioxidant system molecules that are altered in response to elevated redox stress. In vivo, excessive ROS can alter molecules such as proteins, carbohydrates, lipids (particularly phospholipids), and DNA[11].

Some of these changes are known to directly affect the molecule's function (for example, by inhibiting the activity of an enzyme), whereas others just indicate the level of oxidative stress present in the surrounding environment. One of the primary factors influencing the validity of the marker is the functional importance or causative effect of the oxidative alteration on cell, organ, and system function. A ROS biomarker's clinical applicability is also influenced by the assay's specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility in measuring the modification; the biomarker's stability under different storage conditions and specimen preparation procedures; and the ease of obtaining a suitable biological specimen[11].

There are many oxidative stress biomarkers in CHD. However, this article summarised the role of oxidative stress biomarkers such as paraoxonase (PON), nitrotyrosine (N-TYR), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), advanced glycation end-products (AGE), 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), myeloperoxidase, superoxide dismutase (SOD), malondialdehyde (MDA), isoprostanes, catalase (CAT), derivatives of reactive oxidative metabolites (DROMs) in the pathogenesis of CHD.

To conduct this literature review, multiple databases such as Google Scholar, PubMed, and Science Direct were searched. The search process was concluded on 20 August 2025. Various keywords, including ‘Coronary artery disease’, ‘Coronary heart disease’, ‘Oxidative stress’, ‘Biomarkers’, ‘Pathogenesis’ and ‘therapeutic approaches’ were employed. The selection of literature was guided by predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure the relevance and quality of the studies incorporated into this review.

Peer-reviewed original research articles, systematic reviews, editorials and meta-analyses published in English and available in full text through recognized databases were considered for inclusion. Although preference was given to more recent publications, no strict time restrictions were applied. The review primarily focused on studies investigating the role of oxidative stress biomarkers in the pathogenesis of CAD, particularly those addressing pathogenesis and thera

Non-peer-reviewed sources, such as commentaries or opinion pieces. Conference abstracts or case reports with insufficient data. Duplicate publications. Studies not directly related to the objectives of this review. The excluded criteria pertain to studies that specifically address different CVD.

The circulating levels of oxidative stress biomarkers in the pathogenesis of CHD are explained in Table 1. The leading cause of death globally is CAD. Atherosclerosis is a progressive, multifactorial, inflammatory disease of the artery wall that accounts for the majority of CAD cases. Atherosclerotic plaque rupture, the disease's last stage, can result in arterial blockage and potentially fatal acute coronary syndromes (ACS). When a patient has no other symptoms, atherosclerotic plaque rupture may be the initial sign of the condition. Consequently, predicting the degree of plaque instability may help avoid future cardiovascular events (CE) and improve healthcare for a large number of people[12].

| Oxidative stress biomarkers | Pathogenesis in CHD |

| Paraoxonase | ↓ |

| Nitrotyrosine | ↑ |

| Glutathione peroxidase | ↨ |

| Advanced glycation end products | ↑ |

| 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine | ↑ |

| Myeloperoxidase | ↑ |

| Extracellular superoxide dismutase | ↓ |

| SOD1, SOD2 | ↑ |

| Malondialdehyde | ↑ |

| F2-isoprostanes | ? |

| Catalase activity | ? |

| Derivatives of reactive oxidative metabolites | ↑ |

The primary pathophysiology of CAD is atherosclerosis, which is brought on by the immune system and cardio

The failure of free radical scavengers to enhance patient outcomes has led to the idea that other pathways may mediate clinically significant oxidative stress. Patel et al[16] investigated how new aminothiol indicators of oxidative stress caused by non-free radicals relate to clinical outcomes. In 1411 individuals undergoing coronary angiography, the plasma levels of reduced [cysteine and glutathione (GSH)] and oxidised (cysteine and GSH disulphide) aminothiols were measured using high-performance liquid chromatography. GSH (decreased) and cystine (oxidised) levels were linked to mortality risk both before and after controlling for variables. Compared to individuals who did not meet these limits, greater mortality was linked to both low GSH and high cystine levels. Additionally, mortality was strongly correlated with the cystine/GSH ratio, which was both independent of and additive to the level of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP)[16].

Other cardiovascular mortality outcomes, including combined death and MI, showed similar correlations. In indi

Boieriu et al[17] assessed the relationship between the degree of CAD and sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity. Oxidative stress and inflammation affect SNS activity was also investigated. The adults with severe CAD who were scheduled for coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. Furthermore, circulating NE levels were linked to oxidative stress compounds. SNS activation, as measured by plasma NE levels, was associated with oxidative stress and inflammatory indicators, as well as disease severity as determined by the SYNTAX I score, in CAD patients referred for CABG. This implies that oxidative stress, inflammation, and SNS activation are all parts of a network that are interdependent. To find patients who need a more aggressive strategy to reduce inflammation, oxidative stress, and SNS modulation, it may be interesting to create a score system that includes indicators of inflammation and oxidative stress[17].

The pathophysiology of CAD, particularly in young individuals lacking conventional risk factors for atherosclerosis, is significantly influenced by oxidative stress and inflammation, which also modify atherosclerosis. Gaber et al[18] investigated the possible relationship between the severity of coronary artery lesions in the Egyptian population and the function that certain inflammatory and oxidative stress indicators play in initiating ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) in young patients from Egypt.

Serum levels of oxidative stress indicators, including total antioxidant capacity, NO, lipid peroxide, and reduced GSH, were substantially different in patients compared to controls. According to the SYNTAX score, there is a substantial correlation between the severity of CAD and CRP, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and NO levels. Both inflammation and oxidative stress are associated with the severity of CAD lesions and are pathogenically linked to premature STEMI. The biomarkers under investigation are accessible by theranostic targeting and can be employed in risk stratification[18].

A decreased antioxidant defense and an increase in oxidative stress are factors in the development and progression of CAD. As a result of the resulting explosion of free radicals, lipoproteins, particularly oxidised low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL). If the treatment of CAD may be assessed in the context of oxidant/antioxidant balance with the use of novel markers, more research must be done. There was a correlation between MDA level and GSH level, and between MPO activity and PON activity. The results showed that PON and GSH were substantially lower in patients than in controls, and that oxLDL, MDA, and MPO were significantly higher in patients than in controls. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL), triglycerides, and total cholesterol were all noticeably elevated in CAD patients. There was a noteworthy inverse relationship between MDA and GSH levels and between MPO and PON levels. Patients with CAD were shown to have lower antioxidant status and higher oxidative stress[19].

A key factor in atherosclerosis, oxidative stress is linked to endothelial dysfunction, the development of coronary plaque, and instability. Therefore, early diagnosis and improved prognosis for CAD may be facilitated by the detection of oxidative stress in the vascular wall by trustworthy biomarkers. The present method is to measure stable products produced by the oxidation of macromolecules in plasma or urine due to the short half-life of ROS. Myeloperoxidase, oxLDL, and lipid peroxidation biomarkers, including MDA and F2-isoprostanes, are the most widely used indicators of oxidative stress. The majority of these biomarkers are raised in patients with ACS, are linked to the existence and severity of CAD, and may be able to predict outcomes without the use of conventional CAD risk factors[20].

There is conflicting evidence about the relationship between the risk of CHD and the activity of scavenging antioxidant enzymes. Another study evaluated the relationship between the risk of CHD and the activity of three antioxidant enzymes: CAT, GPx, and SOD. A 1-standard-deviation increase in GPx, SOD, and CAT activity levels was linked to CHD with pooled odds ratios (ORs) of 0.51 (95%CI: 0.35-0.75), 0.48 (95%CI: 0.32-0.72), and 0.32 (95%CI: 0.16-0.61), respectively. SOD, GPx, and CAT activity levels in the blood are inversely correlated with CHD[21].

The three different kinds of PON proteins are encoded by the PON1, PON2, and PON3 genes. High-density lipoprotein (HDL) is physically and functionally linked to the plasma enzymes PON1 and PON3; however, PON2 is distinguished by its intracellular location. Numerous PON polymorphisms have been found. The human body depends on all forms of PON, which have anti-inflammatory, anti-atherosclerotic, and antioxidant properties. The PON family prevents the initial step in the development of atherosclerosis, the oxidative alteration of LDL, and the conversion of monocytes into macrophages. Additionally, PON1 promotes cholesterol efflux from macrophages and inhibits the buildup of oxidised LDL. Researchers are now examining the connection between the PON family and lipids in both healthy individuals and patients with cardiovascular illnesses as a result of establishing these activities. PON1 polymorphism and HDL and LDL particles are related in a specific way[22].

PON1 on HDL is primarily responsible for its antioxidant action. PON1 may offer protection against atherosclerosis, according to studies conducted on transgenic PON1 knockout mice. Since HDL's effect on lowering LDL lipid pe

Atherosclerosis may be delayed by human serum PON, which hydrolyses oxidised lipids in LDL. Several case-control studies have supported this theory by demonstrating a correlation between the presence of CHD and polymorphisms at amino acid positions 55 and 192 of PON1, which is linked to a reduced ability of PON1 to shield LDL from the buildup of lipid peroxides. However, other studies have not. Nevertheless, the PON1 polymorphisms are just one element in

In patients with CAD, another study looked at how variations in PON-1 affected their long-term clinical results. Being an antioxidant and detoxifying esterase, PON-1 is a possible therapeutic target to further lower cardiovascular risk. Human cardiovascular risk is influenced by PON activity, and PON-1 knockout mice increase vulnerability to atherosclerosis. Variants in human genes control PON activity; however, it is still unknown how these variations affect recurrent CE in vascular disease. Two PON-1 isotypes (L55M, rs854560, and Q192R, rs662) that had previously been linked to PON activity had their genotypes determined. Methionine at codon 55 and the PON-1 glutamine isoform at codon 192 were linked to an increased risk of dying from IHD. For the glutamine isotype at codon 192, the hazard ratios (HR) per allele copy were 1.71 (95%CI: 1.0-2.8, P = 0.03), whereas for methionine at codon 55, they were 1.56 (95%CI: 1.1-2.3, P = 0.03). Prior research has linked both isotypes to decreased PON activity. There was no change in all-cause mortality. Though they did not affect all-cause mortality, PON-1 gene variations affect male patients' 10-year chance of dying from CAD complications[25].

A key player in the oxidation of LDL and the inhibition of coronary atherogenesis is PON1. In this regard, the PON1 gene's coding region polymorphisms, which determine the enzyme's activity, have gained attention as an atherogenesis marker. The association between the PON1 Q192R (rs662; A/G) polymorphism, the type of ACS, cardiovascular risk factors [dyslipidemia, smoking, diabetes mellitus (DM), and arterial hypertension], the degree and severity of coronary atherosclerosis, and the medium-term clinical follow-up was evaluated in a study and follow-up of 529 patients who experienced an acute coronary event. 245 patients (46.3%) had the QQ genotype, 218 patients (41.2%) had the QR genotype, and 66 patients (14.5%) had the RR genotype. There were no discernible changes between the QQ and QR/RR genotypes in terms of the angiographic variables, analytical data, or clinical features. The QQ and QR/RR genotypes did not significantly vary in terms of presenting with a new acute coronary event (P = 0.598), cardiac mortality (P = 0.701), stent thrombosis (P = 0.508), or stent re-stenosis (P = 0.598) during the course of the follow-up period (3.3 ± 2.2 years), according to Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. The probability of experiencing a new acute coronary event during the medium-term follow-up period was not influenced by the PON1 Q192R genotypes in individuals with ACS[26].

It is generally known that DM increases the risk of CAD. It is well known that the PON enzyme protects against lipid peroxidation. Another study looked into how PON activity levels changed during the course of DM and how it affected the development of CAD. Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), PON enzyme activity, and standard bioche

PON are three enzymes (PON1, PON2, and PON3) that contribute to the antioxidant system of the body; changes in these enzymes are linked to oxidative stress-related illnesses. An overview of the data linking PON to the aetiology of atherosclerosis and CAD was presented. Although there was no clear correlation between PON gene polymorphisms and CAD, the majority of research supports the idea that changes in PON1 enzymatic activity levels do affect the deve

Reactive nitrogen species cause the oxidative post-translational alteration known as N-TYR, or 3-N-TYR. Because N-TYR has low stoichiometric quantities in biological samples, it is difficult to identify N-TYR-modified proteins, despite the fact that it is a sign of oxidative stress and has been linked to inflammation, neurodegeneration, CVD, and cancer[29].

The primary contributor to CVD, which is the world's leading cause of premature mortality, is atherosclerosis. Foam cells are lipid-laden macrophages that build up in the lesion area's subendothelial region and help to create a persistent inflammatory state that releases oxidants produced from nitrogen and oxygen. Atherosclerotic lesions and plasma both include oxidatively altered proteins and lipids. One significant oxidative posttranslational protein alteration is the insertion of a nitro group, which is facilitated by oxidants originating from NO, into the hydroxyphenyl ring of tyrosine residues. Atherosclerotic patients' plasma and the lesion both included N-TYR-modified proteins.

Despite the low nitration yield, the immunogenic, proatherogenic, and prothrombotic properties of 3-N-TYR-modified proteins are consistent with epidemiological studies that demonstrate a strong relationship between the prevalence of CVD and the amount of nitration present in plasma proteins. This supports the utility of this biomarker in predicting the course of atherosclerotic disease and in making the right treatment decisions[30].

Atherosclerosis development and inflammation may be linked by the production of oxidants from NO. Human atherosclerotic lesions and LDL retrieved from human atheroma are high in N-TYR, a particular marker for protein mo

Another study examined the relationship between long-term survival and N-TYR levels in the ACS Registry Strategy (ERICO project), a prospective cohort that is now being used to research CHD. N-TYR levels were assessed in 342 individuals during the acute and subacute phases following the onset of MI and unstable angina, two signs of ACS. N-TYR levels, irrespective of ACS subtype, ranged from 3.09 nmol/L to 1500 nmol/L, with a median of 208.33 nmol/L. Over a 4-year follow-up period, we saw 44 (12.9%) fatalities. Survival days: 1353, 95%CI: 1320-1387 days; overall survival rate: 298 (87.1%) days. Up to four years, N-TYR levels have no correlation with death or survival rates. During the 4-year follow-up in the ERICO research, there was no correlation between N-TYR levels and death rates following ACS[32].

The pathologic function of immunity in atherosclerosis is supported by several lines of evidence. In atheromatous lesions in the bloodstream of patients with CAD, tyrosine-nitrated proteins, is a trace of oxidants derived from oxygen and nitrogen and produced by immune system cells, are more prevalent. However, no research has been done on the effects of potential immunological responses brought on by nitrated protein exposure in individuals with clinically confirmed atherosclerosis. Certain immunoglobulins that are capable of identifying 3-N-TYR epitopes have been found in human lesions and in the bloodstream of CAD patients. The circulating antibody levels against 3-N-TYR epitopes were measured in CAD patients (n = 374) and non-CAD controls (n = 313).

The mean amount of circulating immunoglobulins against protein-bound 3-N-TYR increased by a factor of 10 in CAD patients, and this increase was closely linked to angiographic indications of severe CAD. According to the findings of this cross-sectional study, oxidant production and immune system activation in CAD are related because posttranslational modification of proteins through nitration acts as a neo-epitope for the elaboration of immunoglobulins in atherosclerotic plaque-filled arteries and in circulation[33].

Though their levels in resistance arteries and their function as helpful indicators of endothelial dysfunction remain unknown, heat shock proteins (HSPs) have been proposed to be key players in the pathophysiology of CVD. Using isolated small subcutaneous arteries from both male and female patients with CHD, the authors examined the levels of HSP90, HSP70, HSP60, and HSP27 as well as the oxidative stress marker N-TYR and compared them with healthy controls. By using immunohistochemistry with streptavidin-biotin complex and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine staining, HSPs and NT levels were examined. Both male and female patients' arteries had lower levels of HSP90 than the healthy controls, while only male patients' arteries had lower levels of HSP70 than the controls. There was no discernible difference between the male and female groups' levels of HSP60 and HSP27. The arteries of female patients had greater levels of NT than those of controls[34].

GPx is indeed a valuable oxidative stress biomarker, primarily due to its role in detoxifying harmful ROS like hydrogen peroxide and lipid hydroperoxides. GPx utilises GSH to reduce these ROS, thus preventing cellular damage. When oxidative stress increases, the demand for GPx activity rises, making it a useful indicator of the body's antioxidant defence status. GPx3 is an antioxidant enzyme responsible for degrading hydrogen peroxide, plays a protective role against thrombosis. Mammalian cells' cytoplasm and mitochondria contain GPx1, a crucial cellular antioxidant enzyme. Similar to the majority of selenoenzymes, it contains a single redox-sensitive amino acid called selenocysteine, which is crucial for the enzymatic reduction of soluble lipid hydroperoxides and hydrogen peroxide. For its function, GSH serves as the source of reducing equivalents. The antioxidant enzyme GPx1 regulates the ratio of ROS that are beneficial to those that are detrimental[35].

The regulation of ROS is largely dependent on cellular antioxidant enzymes like SOD and GPx1. Although little is known about these enzymes' significance to human illness, in vitro data and research in animal models indicate that they may offer protection against atherosclerosis. While SOD activity was not associated with risk, GPx1 activity was one of the best univariate predictors of the risk of CE. An elevated risk of CE is independently linked to reduced red-cell GPx1 activity in individuals with CAD. Beyond the predictive significance of conventional risk variables, GPx1 activity may also be useful. Additionally, increasing GPx1 activity may reduce the incidence of heart attacks[36].

It has been suggested that GPX-1 activity is a valuable indicator for tracking CVD. However, the GPX-1 polymorphism has limited ability to accurately evaluate CAD in South Asian populations. Wickremasinghe et al[37] evaluated GPX-1 polymorphism and GPX-1 activity in patients with CAD who were verified to have coronary angiography results and in participants who appeared to be in good health. When it came to ruling out significant artery disease, the erythrocyte GPX-1 cutoff value of 23.9 U/gHb had a high sensitivity and negative predictive value, according to coronary angio

Given the increasing interest in the role of free radicals in the pathophysiology of myocardial ischemia, it was deemed important to investigate the alterations in lipid peroxides and GPx, an antioxidant enzyme, in IHD. When comparing acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients to controls, lipid peroxides such as MDA increased significantly (P < 0.001) (5.9 ± 0.7 mmol/L), and GPx decreased (24.6 ± 2.2 U/gmHb). MDA and GPx are relevant metrics in IHD, and their size depends on the length and/or severity of ischemia[38].

The GSH levels of the CHD patients and controls did not differ significantly. The significance of the antioxidant system in ACS is suggested by the increased GSH reductase activity in the serum of patients with unstable angina pectoris (SAP) and MI[39].

Only half of the morbidity and death from CHD can be attributed to traditional risk factors. There is strong evidence that the atherosclerotic process is significantly influenced by oxidative damage. Antioxidants may therefore prevent atherosclerosis from developing. An intracellular tripeptide with antioxidant qualities, GSH, could offer protection. Compared to control offspring, case offspring showed substantially reduced tGSH. LDL cholesterol, tGSH, HDL cholesterol, and total serum homocysteine (Hcy) all entered the model as significant predictors of parental CHD status in multiple logistic regression, which included age as a covariate and other CHD risk factors vying to enter as significant independent predictor variables. Along with increased LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol, and raised total serum Hcy concentrations, low tGSH in teenage boys is a strong independent predictor of parental CHD[40].

The main line of defence against oxidative stress is GPx, an antioxidant enzyme. In a group with ACS, the prognostic value of GPx is debatable. The influence of GPx levels on clinical outcomes following an ACS is determined in this study, which also examines the variation of GPx and its link to oxidative stress in acute and chronic coronary disease. In contrast to the stable and healthy groups, ACS patients had considerably higher plasma GPx and oxLDL levels. In order to ascertain the predictive importance of GPx activity, GPx activity was examined in 262 ACS patients at index admission. Compared to patients in the upper quartile, those with GPx activity in the lower quartile experienced a higher risk of adverse events. In contrast to a stable and healthy population, the ACS cohort had considerably higher levels of GPx and oxLDL. At one year, the ACS cohort's low levels of GPx activity were linked to a higher chance of adverse outcomes. Research on the factors causing GPx to be up-regulated in ACS is still underway[41].

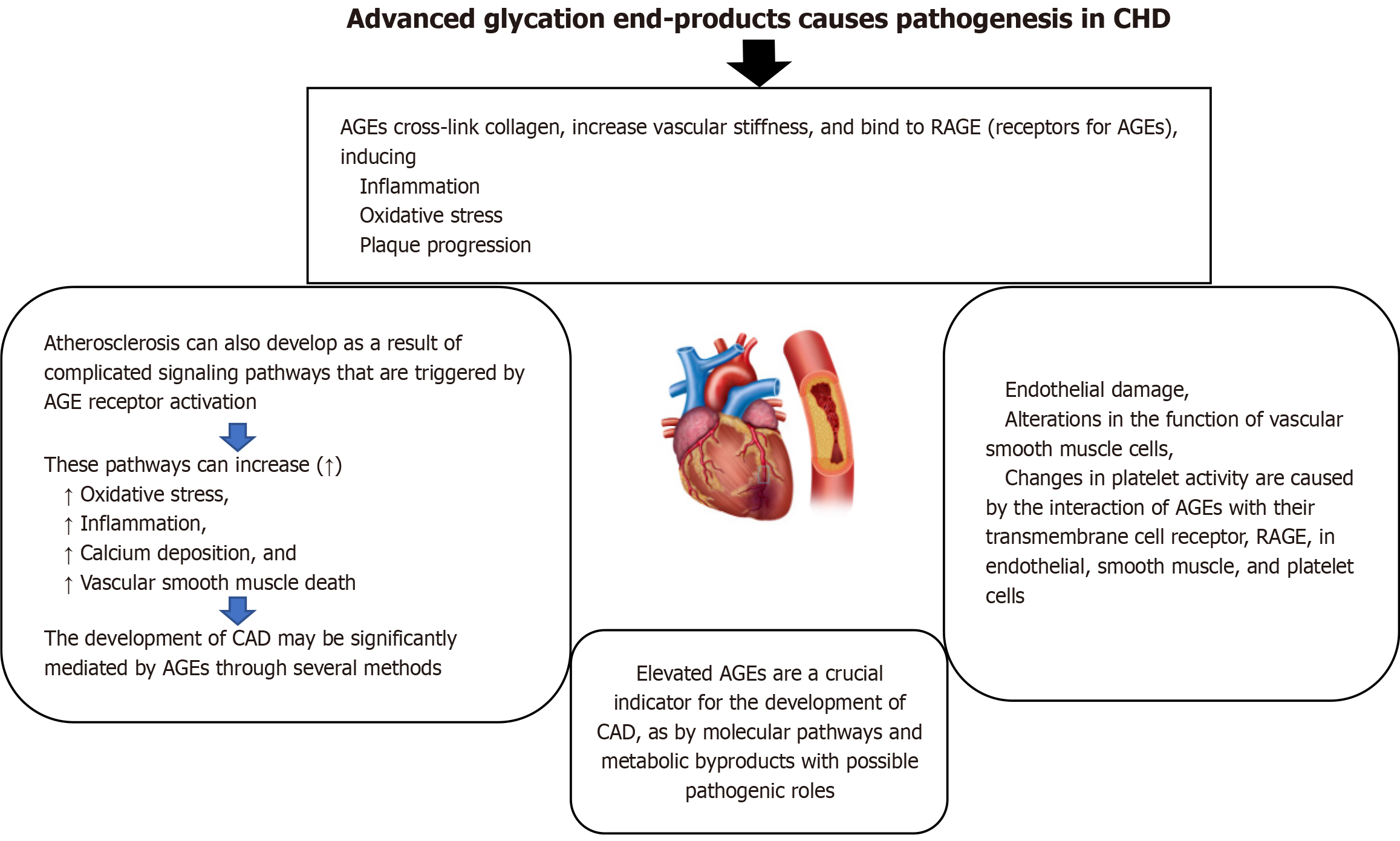

AGEs can be used as oxidative stress biomarkers because their formation is accelerated by oxidative stress and they, in turn, contribute to further oxidative damage. AGEs are formed through non-enzymatic glycation, where sugars like glucose react with proteins and lipids, and this process is exacerbated by oxidative stress. The interaction of AGEs with their receptor (RAGE) further amplifies oxidative stress, creating a vicious cycle. In the pathophysiology of diabetes and its related consequences, advanced glycation end products are a wide range of compounds produced by non-enzymatic glycosylation, and the receptor of advanced glycation end products is essential. The AGE-RAGE axis may hasten the development of cardiovascular disorders, such as arrhythmia, pulmonary hypertension, myocarditis, atherosclerosis, heart failure, and other associated disorders. Whatever its role in diabetes, the AGE-RAGE axis plays a complex role in the development and progression of cardiovascular illnesses. These processes include inflammation, autophagy flux changes, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial malfunction. On the other hand, the AGE-RAGE axis may be successfully disrupted by preventing AGE synthesis, preventing RAGE from attaching to its ligands, or suppressing RAGE expression, which would postpone or improve the aforementioned disorders. Both AGE and sRAGE, the soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products, may be new indicators of heart disease[42]. Figure 1 explains that the advanced glycation end products cause pathogenesis in CHD.

In adults with diabetes, CAD continues to be the major cause of death; nevertheless, it is also highly prevalent in persons without diabetes. In both situations, elevated AGEs are a crucial indicator for the development of CAD, as is the search for shared molecular pathways and metabolic byproducts with possible pathogenic roles. Endothelial damage, alterations in the function of vascular smooth muscle cells, and changes in platelet activity are caused by the interaction of AGEs with their transmembrane cell receptor, RAGE, in endothelial, smooth muscle, and platelet cells. Additionally, the existing therapeutic techniques for stent restenosis are impacted by tissue buildup of AGEs[43].

In patients with DM, CAD cannot be fully explained by traditional risk factors. Their receptors and AGE may be crucial to the onset and course of CAD. The defining characteristic of diabetes is hyperglycemia. It has been found that the longer the duration of hyperglycemia, the higher the frequency of both micro- and macrovascular consequences of diabetes. Even when glycemic control has been attained, this connection remains, pointing to an underlying "metabolic memory" mechanism. AGEs are glycated proteins that, because of their delayed turnover and increased synthesis in hyper

Since it has been demonstrated that patients with oxidative stress-associated diseases had higher levels of 8-OHdG in their serum or urine, this was one of the successful discoveries of the late 1980s. A well-known biomarker for oxidative DNA damage, 8-OHdG, illustrates how ROS affect cellular DNA[45].

The onset and advancement of CVD may be influenced by oxidative stress brought on by an excess of ROS. One indicator of the oxidative DNA damage brought on by ROS is 8-OHdG. Every case-control study demonstrated a strong positive correlation between 8-OHdG and CVD. A strong correlation between 8-OHdG and heart failure was found in two prospective investigations. Last but not least, one prospective investigation revealed a borderline significant connection between 8-OHdG concentrations and CAD patients experiencing a cardiac event, while two prospective studies discovered a substantial link between 8-OHdG and stroke. In summary, atherosclerosis and heart failure are linked to elevated blood and urine levels of 8-OHdG; nevertheless, more large prospective studies are required to examine 8-OHdG as a predictor of cardiovascular illnesses[46].

It is unclear if mitochondrial 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine, a biomarker of oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), has a role in the development of CAD in diabetic victims. Here, another study investigated the relationships between mtDNA 8-OHdG in leukocytes and cardiovascular biomarkers, coronary stenosis severity, obstructive CAD, and unfavourable outcomes one year following myocardial revascularisation in individuals with type 2 DM. The consequences of mtDNA oxidative damage in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) grown on high glucose were also seen in vitro. Cross-sectionally, after controlling for confounders, higher levels of mtDNA 8-OHdG were linked to higher odds of coronary stenosis [number of diseased vessels: OR = 1.29, 95%CI: 1.19-1.41; modified Gensini scores: OR = 1.28, 95%CI: 1.18-1.39], obstructive CAD (OR = 1.38, 95%CI: 1.24-1.52), and CRP[47].

Current smokers had the strongest correlation between mtDNA 8-OHdG and obstructive CAD, according to stratification by smoking status. To predict 1-year MACCEs following revascularisation, the adjusted hazards ratio per 1-SD rise in mtDNA 8-OHdG was 1.59 (95%CI: 1.33-1.90). Antimycin A, an inducer of mtDNA oxidative damage, caused detrimental changes in endothelia and mitochondrial function indicators in HUVECs. In individuals with type 2 diabetes, elevated mtDNA 8-OHdG in leukocytes may operate as a separate risk factor for CAD[47].

One heme peroxidase cyclooxygenase enzyme, MPO, is a 146 kDa homodimeric protein that is glycosylated and made up of two monomers. Each monomer is composed of a 58.5 kDa heavy glycosylated chain and a 14.5 kDa light chain. It has a calcium-binding site required for enzymatic activities as well as a prosthetic heme derivative[12,48]. MPO may be identified in neutrophils, macrophages, and monocytes that are positive for lymphocyte antigen 6C and are produced in the human promyelocytic cell line HL-60 and hematopoietic cells in bone marrow during myeloid lineage development[49-51].

To create an active monomeric proMPO, the synthesis begins with the transcription and translation of the MPO gene on the long arm of chromosome 17. This is followed by N-glycosylation, a brief interaction between the molecular chaperones calnexin and calreticurin, and incorporation with heme from protoporphytin IX. After being transported to the Golgi and transformed into a mature MPO, ProMPO is dimerised by the production of disulfide bonds and broken by proteolytic enzymes[52].

CAD is mostly caused by atherosclerosis. MI and other acute atherosclerosis complications are brought on by the rupture of susceptible atherosclerotic plaques, which are typified by thin, highly inflammatory, and collagen-poor fibrous caps. Numerous lines of evidence establish a mechanistic connection between inflammation, MPO, heme peroxidase, and both acute and chronic atherosclerosis symptoms. It has been demonstrated that MPO and MPO-derived oxidants have a role in the production of foam cells, endothelial dysfunction and death, latent matrix metalloproteinases activation, and tissue factor expression, all of which might encourage the creation of susceptible plaque[12].

The two biggest causes of mortality and disability in the world today are MI and CAD. Chronic arterial inflammation and oxidation lead to the development of atherosclerotic plaques in the coronary artery's intimal layer, which is the first step in CAD. An important pro-inflammatory and oxidative enzyme that contributes to the formation of susceptible coronary atherosclerotic plaques that are prone to rupture and can cause a MI is MPO, a mammalian hemoperoxidase enzyme that is mainly expressed in neutrophils and monocytes. Additionally, there is growing evidence that MPO has a pathogenic role in the inflammatory process that follows a MI, which is marked by the production of MPO and the rapid influx of active neutrophils into the injured myocardium. Adverse cardiac outcomes, reduced long-term cardiac function, and ultimately heart failure are caused by excessive and prolonged cardiac inflammation, which hinders normal cardiac recovery after MI. MPO is a key oxidative enzyme that plays a role in the improper inflammatory reactions that propel the development of CAD and poor heart repair following a MI[53].

Another study aims to improve diagnosis accuracy and treatment approaches by examining the relationship between MPO and genetic polymorphisms and CAD. Glucose, total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, creatinine, and troponin levels were among the clinical indicators that varied significantly. In addition, the mean platelet volume (MPV) and red cell distribution width (RDW%) were smaller in CAD patients than in controls. There was no significant difference in serum MPO levels between CAD patients and controls, and there was no association with any other clinical indicators other than total bilirubin, creatinine, and glucose. Lower MPO levels in CAD patients relative to controls reveal that serum MPO levels are not significantly associated with CAD patients. The potential of MPV and RDW% as indicators of extensive atherosclerosis in CAD is also highlighted. RDW%, MPV, and MPO levels in CAD require more study to confirm their diagnostic and prognostic use[54].

One potential mediator of atherosclerosis is myeloperoxidase, a leukocyte enzyme that promotes the oxidation of lipoproteins in atheroma. To ascertain if MPO levels and CAD prevalence are related. CAD risk is associated with MPO levels per milliliter of blood (blood-MPO) and MPO levels per milligram of neutrophil protein (leukocyte-MPO). Patients with CAD had considerably higher levels of leukocyte- and blood-MPO than controls (P < 0.001). MPO levels were substantially linked to the presence of CAD in multivariable models that controlled for white blood cell counts, the Framingham risk score, and traditional cardiovascular risk factors. The ORs for the highest and lowest quartiles of leukocyte-MPO and blood-MPO were 11.9 (95%CI: 5.5-25.5) and 20.4 (95%CI: 8.9-47.2), respectively. DM is linked to elevated blood and leukocyte MPO levels. The diagnosis of atherosclerosis and risk assessment may be affected by these findings, which further suggest that MPO may play a role in CAD as an inflammatory marker[55].

Another study assessed whether blood myeloperoxidase levels in people who appear to be in good health are linked to their chance of developing CAD in the future. Multiple proatherogenic actions are exhibited by MPO, an innate immune system enzyme. LDL and HDL cholesterol are oxidatively damaged, and plaque susceptibility is increased. MPO inde

In Cheng et al[57] study, the diagnostic and prognostic usefulness of myeloperoxidase, Hcy, and high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP) was evaluated in relation to the severity of CAD. The single vessel disease group (SVG), double vessel disease group (DVG), and multi vessel disease group (MVG) were further classifications of the patients based on the arteriography results. The three groups' Gensini scores were assessed using the Gensini score standard. Analysis was done on the relationships between the PG's Gensini score and the expression of MPO, Hcy, or hsCRP[57].

The predictive values of MPO, Hcy, and hsCRP with respect to major adverse CE (MACEs) were ascertained using receiver operating characteristic analysis, and the patients' MACEs were tracked over a period of six months and com

Individuals with multiple lesions had a considerably greater overall incidence of MACEs than individuals with single and double lesions. Both the SVG and the DVG groups had lower overall MACE incidences than the MVG group, but the DVG group had a higher overall MACE incidence than the SVG. MPO levels had a larger area under the curve (AUC) and sensitivity for predicting MACEs than did Hcy and hsCRP; however, there was no discernible difference between the AUC and sensitivity of Hcy and hsCRP for MACE prediction. When it came to predicting MACEs, hsCRP had a greater specificity than MPO and Hcy[57].

Although the findings are still preliminary, the MPO gene polymorphisms 463G/A and 129G/A have been linked to CAD. Strong evidence suggested a link between CAD and the MPO 463G/A polymorphism. According to the data, only the dominant model (dominant model: OR = 0.872, 95%CI: 0.77-0.99) was linked to CAD. The genotypes AA + AG and GG had a pooled OR of 0.906 (95%CI: 0.74-1.10) for the 129G/A gene polymorphism. The MPO 129G/A gene polymor

When inflammation occurs, the enzyme MPO, which is contained in the azurophilic granules of macrophages and polymorphonuclear neutrophils, is released into the extracellular fluid. Studying myeloperoxidase as a potential indicator of plaque instability and a practical clinical tool in the assessment of patients with CHD has been prompted by the discovery that it is implicated in oxidative stress and inflammation[59].

MPO disrupts endothelial functioning. In individuals with stable CAD (SCAD), another study looked at whether rising MPO and inflammatory marker concentrations caused progression and incident ACS. Lipids, MPO, lipoproteins [apo (apolipoprotein) AI, apoB, lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (LpPLA2) level], and inflammatory markers (hsCRP), TNF-α, and interleukin (IL)-6 concentration were thus measured. The 67 SCAD patients in this study were split into five groups: All patients, patients with MPO concentrations < 200 ng/mL, MPO concentrations 200-300 ng/mL, MPO concentrations > 300 ng/mL, and 15 controls[60].

The concentrations of TG, apoB, MPO, inflammatory markers, and TG/HDL-C, MPO/apoAI, and MPO/HDL-C ratios were significantly higher in the group with MPO 200-300 ng/mL, but HDL-C, apoAI level, and HDL-C/apoAI ratio were significantly lower. In the group with MPO 200-300 ng/mL, TC, LDL-C, nonHDL-C, LpPLA2 concentration, and TC/HDL-C, LDL-C/HDL-C ratios were insignificant. The levels of TC, LDL-C, non-HDL-C, apoAI, apoAII, LpPLA2, and MPO were not significant in the group of patients with MPO < 200 ng/mL, while HDL-C was reduced. However, inflammatory markers, apoB, TG, TG/HDL-C, MPO/apoAI, and MPO/HDL-C ratio were. TC, LDL-C, nonHDL-C, apoAII, LpPLA2, and LDL-C/HDL-C ratios were not significant in the group of patients with MPO > 300 ng/mL, whereas HDL-C and apoAI concentrations were considerably lower[60].

In comparison to the controls, there was a substantial rise in the concentrations of inflammatory markers, TG, apoB, and MPO, as well as in the ratios of TG to HDL-C, MPO to apoAI, and MPO to HDL-C. Comparing the group of patients with MPO < 200 ng/mL to the group with MPO and hsCRP, the apoAI concentration was considerably lower, and the MPO/apoAI and MPO/HDL-C ratios were significantly greater. In all patients, MPO concentration and MPO/apoAI and MPO/HDL-C ratios were positively correlated, as was MPO < 200 ng/mL and MPO 200-300 ng/mL. The concentration of MPO and the levels of hsCRP and IL-6 were positively correlated in patients with MPO > 300 ng/mL, whereas the MPO/apoAI ratio was negatively correlated with the levels of HDL-C, apoAI, and apoAII[60].

According to the findings, mild dyslipidemia and dyslipoproteinemia heighten inflammation, and inflammation gradually raises MPO levels, which lower apoAI and HDL-C levels and impair HDL function. Increasing MPO levels and MPO/HDL-C and MPO/apoAI ratios might help identify SCAD patients who are at risk for stroke and ACS[60].

High mortality and cardiovascular risk are linked to chronic kidney disease (CKD). Patients with mild-to-moderate CKD have had adverse effects associated with MPO. Janus et al[61] aimed to determine if MPO levels in CKD patients are linked to unfavourable outcomes. Following many corrections, individuals with a history of CAD who had doubled their MPO had a higher risk of heart failure [HR = 1.15 (1.01-1.30), P = 0.032], mortality [HR = 1.16 (1.05-1.30), P = 0.005], and the composite outcome of MI, peripheral artery disease, and cerebrovascular accident, and death [HR = 1.12 (1.01-1.25), P = 0.031]. All-cause mortality, incident heart attack, and a composite outcome are all independently correlated with MPO levels in this group of patients with mild to moderate CKD and CAD[61].

The main enzymatic defence against free radicals and common oxidants is said to be SOD. The only extracellular form of SOD that is seen in high concentration in vascular intima is extracellular SOD (EC-SOD). Clarifying the function of EC-SOD in CAD patients and assessing its correlation with inflammation, free radicals, and disease severity were the objectives of the current investigation[62].

Following cardiac catheterisation and coronariography, each subject's serum levels of peroxy radicals, high-sensitive IL-6 (hs-IL-6), high-sensitive TNF, hs-CRP, and serum EC-SOD activity were assessed. While there was no discernible difference between the patients and controls in terms of EC-SOD serum activity, there was a significant difference between the two groups in terms of peroxy radicals, hs-IL-6, and hs-CRP serum levels. Additionally, in severe disease (involving three or four coronary arteries; P < 0.05), elevated hs-IL-6 serum levels were also noted, and EC-SOD activity increased somewhat with the number of arteries affected. CRP levels and peroxy radicals were statistically substantially correlated with hs-IL-6 concentrations[62].

Endothelial dysfunction in individuals with CAD is a result of increased NO inactivation by oxygen-free radicals. As a result, it assessed the activity of the primary antioxidant enzyme system of the arterial wall, EC-SOD, and its relationship to flow-dependent endothelium-mediated dilatation (FDD) in CAD patients. The coronary arteries of ten CAD patients and ten normal persons were examined for SOD isoenzyme activity. Thirty-five CAD patients and fifteen control participants also had their radial artery FDD and endothelium-bound EC-SOD activity (eEC-SOD), which is released by heparin bolus injection, assessed. High-resolution ultrasonography was used to measure FDD at baseline, following intra-arterial infusions of vitamin C, N-monomethyl-L-arginine, and a combination of the two. Patients suffering from CAD had lower levels of EC-SOD activity in their coronary arteries and eEC-SOD activity in vivo. eEC-SOD activity was ad

Another study assessed the plasma levels of SOD1, SOD2, and SOD3 in order to ascertain whether these enzymes can serve as biomarkers for CAD. Patients with ACS (n = 49), patients with SAP (n = 33), and controls (n = 42) comprised the patient groups. CAD patients had greater plasma SOD1 and SOD2 values than healthy controls. There was no change in SOD3 levels between the control and CAD groups. SODs and coronary artery stenosis severity, age, and gender showed very weak associations. SOD1 and SOD2 plasma levels were higher in CAD patients and may be used as stand-in bio

One byproduct of the cells' peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids is MDA. A rise in free radicals leads to an excess of MDA. MDA levels are frequently used to assess the antioxidant state and oxidative stress in cancer patients[66]. The primary source of free oxygen radicals, which can lead to organ failure by oxidizing cellular macromolecules, including proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates, is the mitochondria. Either an excess of these species or a breakdown of the an

Based on the severity of their CAD, 133 patients were included in the research and divided into three groups: Mild (n = 71), moderate (n = 39), and severe (n = 23). The severity of CAD was substantially correlated with elevated serum MDA levels. In particular, MDA levels peaked at 459.91 ± 149.80 in the severe group, were 116.61 ± 41.95 in the mild group, and were 253.45 ± 180.29 in the moderate group. Higher MDA levels were associated with more severe CAD, as evidenced by the statistically significant differences in MDA levels between these groups (P < 0.01). Significant effects on MDA levels were also seen in variables including blood pressure, heart rate, body mass index, and smoking status[68]. The diagnostic accuracy of MDA for determining the severity of CAD was shown by receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, with AUC values of 0.81 for mild CAD and 0.94 for severe CAD. DM and other comorbid diseases were linked to higher MDA levels. A dependable, non-invasive biomarker for CAD severity prediction, elevated serum MDA may find use in clinical risk assessment and therapy plans. Early detection of individuals with high oxidative stress allows doctors to intervene promptly, which may delay the course of the disease and improve prognosis[68].

Lipid peroxidation levels in patients with CHD and control participants should be evaluated and compared. Among patients with CHD, MDA and lipid parameters were found to be considerably high, whereas HDL cholesterol was found to be significantly low. Compared to nonsmokers with CHD, smokers with the condition had considerably higher amounts of MDA. High blood levels of MDA show that oxygen-free radicals are being produced at a higher rate, which may contribute to atherogenesis and CHD[69].

CAD and oxidative changes of LDL are suggested but not shown to be related. Therefore, it was examined whether there was a correlation between ACS and stable CAD and plasma levels of oxidised LDL and MDA-modified LDL[70].

The plasma levels of oxidised LDL and MDA-modified LDL were considerably greater in CAD patients than in non-CAD patients, even after controlling for age, sex, and LDL and HDL cholesterol. Compared to people with stable CAD, patients with ACS had substantially greater plasma levels of MDA-modified LDL, which were linked to higher troponin I and CRP levels. Elevations of troponin I and CRP were not linked to plasma levels of oxidised LDL. CAD is linked to elevated oxidised LDL plasma levels. Patients with ACS may be identified by elevated plasma levels of MDA-modified LDL, which indicate plaque instability[70].

The polyunsaturated fatty acid arachidonic acid, which is found in the phospholipids of cell membranes, is peroxidised to produce the stable, prostaglandin-like molecules known as Isoprostanes (isoPs)[71]. The cyclooxygenase enzyme, which catalyses the synthesis of prostaglandins from arachidonic acid, is not necessary for the creation of IsoPs from arachidonic acid[72].

Oxidative stress may contribute to the onset and advancement of CVD. Evidence about its biochemical markers has been contentious, nevertheless. F2-isoprostanes, a marker for evaluating in vivo lipid oxidation, were evaluated in this paper as a potential biomarker for CVD, which includes peripheral artery disease, CAD, and stroke. Elevations of F2-isoprostanes in blood or urine might be a general sign of CVD. More population-based research is necessary, though. Furthermore, to reduce confounding and increase classification accuracy, multivariable analyses are necessary for future research[73]. Certain PUFA peroxidation products, such as F2-isoprostanes, are helpful biomarkers that may be used as CHD indicators[74].

The CAT gene, located on chromosome 11 in humans, encodes the enzyme CAT. Antioxidant defense systems are essential for reducing the harmful effects of ROS. One particularly notable enzymatic antioxidant is CAT. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a potentially hazardous byproduct of cellular metabolism, is effectively broken down by it into water and oxygen. Oxidative damage is avoided, and H2O2 is detoxified by this process. As a therapeutic antioxidant, CAT has been thoroughly investigated. It can be directly supplemented in oxidative stress-prone situations or used in gene therapy to increase endogenous CAT activity[75].

H2O2 may contribute to vasorelaxation during the uncoupling of NO production, according to Cosentino et al[76]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that H2O2 plays a crucial function as a signaling molecule for cardiac remodeling, most likely as a result of its higher permeability and stability when compared to other ROS. According to this, the antio

Another study examined how estrogen affected the modulation of coronary resistance by adjusting the levels of H2O2 and NO in female rats. Elevated levels of estrogen were linked to greater H2O2 levels, enhanced NO bioavailability, and decreased coronary resistance. Rats with ovariectomies showed no appreciable changes in coronary resistance when NO synthase inhibition by L-NAME was administered. Furthermore, it was discovered that CAT activity and NO levels were inversely related. The findings collectively imply that the modulation of coronary resistance appears to be more reliant on the H2O2 that is kept at low levels by elevated CAT activity when estrogen effect and, consequently, decreased NO bioa

The study reported that while SOD and GPX gene expression remained unaltered under elevated oxidative stress in patients with end-stage heart failure, CAT expression appeared to be selectively upregulated as a potential compensatory mechanism[78]. However, no significant association was observed between CAT expression and the development of CHD.

DROMs/d-ROMs are biomarkers used to measure the level of oxidative stress in biological samples, which results from an imbalance between the production of ROS and the body's ability to detoxify them. DROMs are measured by quantifying hydroperoxides, which are byproducts of ROS-induced lipid peroxidation. CVD are exacerbated and developed in part by oxidative stress. Rapidly measuring an imbalance in a person's reductive-oxidative status may enhance the evaluation and treatment of cardiovascular risk. One new biomarker of oxidative stress is d-ROMs, which may be measured in a matter of minutes using either a point-of-care test at the patient's bedside or regular biochemical analyzers. Data on the predictive efficacy of d-ROMs for CVD events and death in people with known and unknown CVD are evaluated in the present review. Measures of effect, including HR, risk ratio, OR, and mean differences, were employed to analyze outcome studies with both small and large cohorts. Elevated levels of d-ROM plasma were discovered to be a separate predictor of mortality and CVD events. Risk increases significantly over 400 UCARR and starts increasing at d-ROM levels greater than 340 UCARR. Low d-ROM plasma levels, on the other hand, are a reliable indicator of CVD events in individuals who have heart failure and CAD. Furthermore, d-ROMs may help promote a more accurate cardiovascular risk assessment when combined with other pertinent biomarkers that are often employed in clinical practice. In primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention, we conclude that d-ROMs are a new biomarker associated with oxidative stress that may improve risk stratification[79].

CAD development is linked to ROS. CAD does not, however, have a good ROS biomarker. Serum DROM were evaluated in 395 consecutive CAD patients who had coronary angiography. Additionally, 227 non-CAD patients were enrolled. Following risk factor and 1:1 pair matching, it conducted a case-control study and a follow-up research were conducted on these 395 CAD patients. In 59 CAD patients, DROM measurements were also made in the coronary sinus and aortic root as part of a subgroup analysis. Compared to risk factor-matched non-CAD patients (n = 163, 311 282-352.5, effect size = 0.33, P346 U.CARR), DROM was substantially greater in CAD patients [n = 163, median (interquartile range) = 338 (302-386)] than in the low-DROM group (≤ 346 U.CARR) (P = 0.001 log-rank test). In-DROM was found to be an independent predictor of CE by multivariate Cox hazard analysis (HR: 10.8, 95%CI: 2.76-42.4, P = 0.001). Patients with CAD had a substantially larger transcardiac gradient of DROM than patients without CAD (2.0 9.0-9.0 vs 8 8.0-28.3, effect size = 0.21, P = 0.04), suggesting that the development of CAD is linked to the generation of DROM in the coronary circulation. Patients with CAD had higher DROM, which is linked to subsequent CE. DROM may offer therapeutic advantages for CAD risk assessment[80].

Atherosclerosis and CAD have been linked to increased oxidative stress. Nevertheless, little is known about the predictive power of circulating oxidative stress indicators for CE in CAD patients. Another study evaluated the impact of reactive oxygen metabolites, which are calculated as an indicator of oxidative stress in blood samples using a commercial kit, on the MACE and mortality rate in CAD. Patients with increased ROM levels (> 75th percentile, or 481 AU) had the considerably poorest result according to the Kaplan-Meier survival estimates (log rank = 11, 7.5, 5.1; P < 0.001, P < 0.01, P < 0.05 for cardiac and all cause mortality and MACEs, respectively). Elevated oxidative stress was still a significant predictor of both cardiac and all-cause mortality in a multivariate Cox regression model [HR = 3.9, 95%CI: 1.4-11.1, P = 0.01; HR = 2.6, 95%CI: 1.1-6.2, P = 0.02; MACE (HR = 1.8, 95%CI: 1.1-3.1, P = 0.03)]. When evaluating CE in CAD patients, the calculation of ROMs could serve as an extra prognostic tool[81]. Oxidative stress biomarkers cause pathogenesis in CHD explained in Table 2.

| Oxidative stress biomarkers | Pathogenesis in CHD | Ref. |

| PON1 | Low PON activity reduces the ability of HDL to prevent LDL oxidation, enhancing foam cell formation and atherogenesis. A key player in the oxidation of LDL and the inhibition of coronary atherogenesis is PON1. There is a direct correlation between low serum PON1 activity and CHD | [23,26] |

| Nitrotyrosine | Elevated levels indicate endothelial dysfunction and vascular inflammation, contributing to plaque instability. Oxidant production and immune system activation in CAD are related because posttranslational modification of proteins through nitration acts as a neo-epitope for the elaboration of immunoglobulins in atherosclerotic plaque-filled arteries and in circulation | [30,33] |

| Advanced glycation end products | Explained in Figure 1 | |

| GPx | Reduced GPx activity weakens antioxidant defense, allowing oxidative damage to endothelial cells and vascular tissues | [35-37] |

| 8-OHdG | Elevated 8-OHdG reflects oxidative DNA injury in vascular cells, which might lead to apoptosis, impaired repair, and vascular remodeling | [45] |

| MPO | MPO promotes LDL oxidation, endothelial dysfunction, and plaque vulnerability. MPO and MPO-derived oxidants have a role in the production of foam cells, endothelial dysfunction and death, latent matrix metalloproteinases activation, and tissue factor expression, all of which might encourage the creation of susceptible plaque | [12] |

| SOD | Reduced SOD activity increases superoxide accumulation, impairing nitric oxide bioavailability, causing endothelial dysfunction. Endothelial dysfunction in CAD patients is exacerbated by decreased EC-SOD activity | [63] |

| MDA | Elevated MDA levels reflect oxidative damage to lipids, promoting LDL modification and atherosclerosis. High blood levels of malondialdehyde show that oxygen-free radicals are being produced at a higher rate, which may contribute to atherogenesis and coronary heart disease | [69] |

| F2-isoprostanes | Not determined | |

| Catalase activity | Not determined | |

| Derivatives of reactive oxidative metabolites | The development of CAD is linked to the generation of DROM in the coronary circulation. Patients with CAD had higher DROM, which is linked to subsequent cardiovascular events | [80] |

Because oxidative stress promotes endothelial dysfunction, vascular inflammation, lipid peroxidation, and atherogenesis, it is a key factor in the development and progression of CHD. To help with risk assessment, discover potential treatment targets, and gain a deeper understanding of disease pathogenesis, a number of oxidative stress indicators have been studied.

PON1 is an HDL-associated enzyme with potent antioxidant and anti-atherogenic properties. Reduced PON1 activity enhances LDL oxidation and contributes to the progression of CHD. Low circulating levels are strongly associated with an increased risk of ACS. N-TYR serves as a marker of peroxynitrite-mediated protein modification. Elevated concentrations are indicative of endothelial dysfunction and plaque instability, highlighting its role in the pathogenesis of CHD. GPx protects against hydrogen peroxide-induced vascular injury.

Reduced GPx activity has been identified as an independent predictor of recurrent CE, underscoring its prognostic value. Also, AGEs promote cross-linking of collagen and elastin, leading to increased vascular stiffness. By binding to their receptor (RAGE), AGEs further amplify oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, thereby accelerating endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis in CHD.

8-OHdG is a well-established indicator of oxidative DNA damage. Elevated levels in CHD patients are associated with disease progression and increased mortality, reflecting its role as a marker of cumulative oxidative injury. MPO is released from activated neutrophils, catalyzes LDL oxidation, and contributes to plaque destabilization. High MPO levels are strongly predictive of ACS and adverse clinical outcomes. SOD plays a central role in superoxide radical clearance. Reduced activity impairs antioxidant defenses and is linked with a worse prognosis in CHD. MDA is a product of lipid peroxidation, is consistently elevated in CHD patients. Its levels correlate with disease severity and atherosclerotic burden, and it serves as a useful biomarker for monitoring responses to antioxidant therapies. F2-isoprostanes are highly reliable markers of in vivo oxidative stress. They are strongly associated with endothelial dysfunction, plaque instability, and the prediction of adverse CE. CAT has emerged as a promising biomarker under investigation. Its activity reflects the capacity to neutralize hydrogen peroxide, and recent evidence suggests potential diagnostic and prognostic value in oxidative stress-related disorders. The evolving role of CAT highlights its importance in preventive strategies, personalized treatment approaches, and improved clinical outcomes. DROMs are also being explored for their therapeutic potential and may serve as valuable tools in risk assessment and management of CAD.

Numerous biomarkers that are raised in CHD, including MDA, F2-isoprostanes, and MPO, may help with early identification. Long-term consequences and unfavorable CE are predicted by the prognostic value of biomarkers, including MPO, 8-OHdG, and GPx activity. Oxidative damage indicators and antioxidant enzyme activity (SOD, GPx, and CAT) can be used to assess how well pharmaceutical treatments and lifestyle changes (statins, antioxidant supplements, etc.) are working. By integrating oxidative stress indicators with traditional risk variables, risk stratification may be evaluated, and the prediction accuracy for the onset and progression of CHD may be improved. Biomarkers for oxidative stress offer important information on the molecular processes underlying CHD. Although assay standardization and extensive validation are required before normal clinical adoption, they have the potential to be diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic tools.

The pathophysiology of CHD is significantly influenced by oxidative stress, which promotes inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, LDL oxidation, plaque instability, and myocardial damage. Targeting the causes and consequences of ROS by lifestyle changes and pharmacological approaches is part of controlling oxidative stress indicators in CHD. In CHD, antioxidant activity is essential because it fights oxidative stress, which causes atherosclerosis. The oxidation of LDLs, a crucial stage in the development of plaque, can be prevented by naturally occurring antioxidants such as carotenoids and vitamins C and E that are present in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. The clinical benefit of antioxidant vitamin supplements is mixed, with some showing potential benefits (like vitamin E) and others, like beta-carotene, demon

Globally, CAD and CVD are the main causes of mortality. The greatest death rate in Iran is caused by them. The conventional risk factors for CAD include DM, hyperlipidemia, smoking, obesity, hypertension, and family history. Ad

The relationship between the activity of scavenging antioxidant enzymes and the risk of CHD is controversial. A 1-standard-deviation increase in GPx, SOD, and CAT activity levels was linked to CHD with pooled ORs of 0.51 (95%CI: 0.35-0.75), 0.48 (95%CI: 0.32-0.72), and 0.32 (95%CI: 0.16-0.61), respectively. There was significant between-study heterogeneity (I2 > 90% for the three enzymes). The results of the sensitivity analysis showed remarkable robustness. SOD, GPx, and CAT activity levels in the blood are inversely correlated with CHD, which also highlights the need for further high-calibre prospective research[21].

Future treatments may target the formation of oxLDL, elevated MPO, and reduced PON, which are all additional risk factors for the development of CAD. Because they enhance antioxidant status and decrease oxidative stress, lifestyle changes and treatment approaches can lower the incidence of CAD[19].

Nevertheless, it is significant because genetic influences are unlikely to be confused by other factors associated with both CHD and decreased PON1 activity. A lot of research is being done on PON1, and it is hoped that new treatment strategies will be developed to boost its activity. If successful, clinical studies of these will not only offer a new way to prevent atherosclerosis but also a more satisfactory way to test the oxidant theory of atherosclerosis than antioxidant vitamin supplementation has[23]. These long-term results support functional data on PON-1 activity, highlight the pathway's importance in vascular illness, and support its suggested function as a target to alter and assess cardiovascular risk[25].

N-TYR levels are linked to CAD and seem to be influenced by statin medication. Atherosclerosis risk assessment and the monitoring of statins' anti-inflammatory effects may be affected by these findings, which point to a possible role for NO-derived oxidants as inflammatory mediators in CAD[31]. Drugs enhancing endogenous GPx reduce oxidative stress burden.

The AGE-RAGE axis may be successfully disrupted by preventing AGE synthesis, preventing RAGE from attaching to its ligands, or suppressing RAGE expression, which would postpone or improve the aforementioned disorders. Both AGE and sRAGE, the soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products, may be new indicators of heart disease[42]. Antioxidant therapies may reduce DNA oxidative damage. Lifestyle interventions (exercise, smoking cessation) lower 8-OHdG levels. Potential use in monitoring the efficacy of therapies targeting DNA oxidative injury.

Exercise, a diet rich in antioxidants, and statins can improve SOD activity. SOD modulation may prevent endothelial dysfunction and delay atherosclerosis progression.

The scientific community is very interested in the potential of CAT as an antioxidant therapeutic. However, there are a number of significant barriers to the widespread use of CAT in therapies, despite its potential to reduce oxidative stress. One major obstacle is the short half-life of CAT, its poor cellular absorption, and the intrinsic difficulty of delivering the enzyme into tissues and systems, such as the central nervous system, safely and efficiently[83].

Determining the ideal dose, creating effective delivery systems, and guaranteeing tissue specificity are the main challenges involved in using CAT in therapeutic contexts. Its broad use is further impeded by factors including manufacturing costs and moral dilemmas surrounding the source of the enzyme. Furthermore, a thorough grasp of the possible unforeseen repercussions in therapeutic scenarios is necessary due to the intricate interaction of CAT with endogenous systems[84].

Innovations in gene therapy, protein engineering, and nanotechnology are expected to propel major breakthroughs in the CAT enzyme. Through the use of gene-editing tools, protein engineering methods, and nanoparticle-based delivery systems, CAT's stability, bioavailability, and targeted administration for therapeutic reasons may all be significantly in

| Biomarkers | Therapeutic aspects in CHD | Ref. |

| PON1 | A lot of research is being done on PON1, and it is hoped that new treatment strategies will be developed to boost its activity. If successful, clinical studies of these will not only offer a new way to prevent atherosclerosis but also a more satisfactory way to test the oxidant theory of atherosclerosis than antioxidant vitamin supplementation has. PON-1 activity highlights the pathway's importance in vascular illness and supports its suggested function as a target to alter and assess cardiovascular risk. HDL-targeted therapies may improve PON activity | [23,25] |

| Nitrotyrosine | Nitrotyrosine levels are linked to CAD and seem to be influenced by statin medication. Atherosclerosis risk assessment and the monitoring of statins' anti-inflammatory effects may be affected by these findings, which point to a possible role for nitric oxide-derived oxidants as inflammatory mediators in CAD. Lowering nitrosative stress by antioxidants may reduce nitrotyrosine formation | [31] |

| AGE | The AGE-RAGE axis may be successfully disrupted by preventing AGE synthesis, preventing RAGE from attaching to its ligands, or suppressing RAGE expression, which would postpone or improve the aforementioned disorders. Both AGE and sRAGE, the soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products, may be new indicators of heart disease | [42] |

| MPO | Chaikijurajai and Tang[87] look at the pathophysiology of atherosclerotic CAD and the mechanistic information from a number of important therapeutic medication targets. The enzymatic activities of MPO are either directly or indirectly attenuated by prototype compounds, such as aminobenzoic acid hydrazide, ferulic acid derivative (INV-315), thiouracil derivatives (PF-1355 and PF-0628999), 2-thioxanthine derivative (AZM198), triazolopyrimidines, acetaminophen, N-acetyl lysyltyrosylcysteine (KYC), flavonoids, triazolopyrimidines, and alternative substrates like thiocyanate and nitroxide radicals. The cardiovascular advantages of direct systemic inhibition of MPO must be evaluated in future research to see if they exceed the danger of immunological dysfunction, which may be lower with other substrates or MPO inhibitors that specifically reduce MPO's atherogenic effects | [87] |

| SOD | Exercise, a diet rich in antioxidants, and statins can improve SOD activity. SOD modulation may prevent endothelial dysfunction and delay atherosclerosis progression | [62] |

| MDA | A dependable, non-invasive biomarker for CAD severity prediction, elevated serum MDA may find use in clinical risk assessment and therapy plans. Early detection of individuals with high oxidative stress allows doctors to intervene promptly, which may delay the course of the disease and improve prognosis. Elevated serum level MDA is a trustworthy, non-invasive biomarker for CAD severity prediction, and it may find use in clinical risk assessment and management plans. Clinicians may be able to decrease the course of the disease and improve outcomes by promptly implementing therapies for individuals with high oxidative stress | [66,68] |

| F2-isoprostanes | F2-isoprostanes are helpful biomarkers that may be used as CHD indicators | [74] |

| Catalase | Innovations in gene therapy, protein engineering, and nanotechnology are expected to propel major breakthroughs in the catalase enzyme's future. Through the use of gene-editing tools, protein engineering methods, and nanoparticle-based delivery systems, catalase's stability, bioavailability, and targeted administration for therapeutic reasons may all be significantly increased. Using computational models for predictive enzyme design, exploring possible synergy with other antioxidants, and tailoring catalase variations to meet particular therapeutic needs are all intriguing approaches to maximizing the therapeutic efficacy of catalase. A new area of study is examining the possible use of catalase as a prognostic or diagnostic biomarker in oxidative stress-related disorders. The complex and ever-changing future prospects of catalase highlight its vital role in advancing disease preventive techniques, advancing customized treatment initiatives, and eventually improving healthcare outcomes. In order to transform treatment interventions and provide comprehensive healthcare solutions for a range of patient groups, catalase is at the forefront of creative techniques by integrating cutting-edge technology and investigating novel applications | [85,86] |

| DROMs' | Furthermore, d-ROMs' clinical importance will be better understood by cross-comparison with other oxidative-stress biomarkers and their inclusion in sizable panels of biomarkers linked to CVD. Finally, to comprehend the potential use of d-ROMs in promoting more individualized therapeutic methods, additional research should be done on the effects of hereditary variables and pharmaceutical therapies on d-ROM levels. DROM may offer therapeutic advantages for CAD risk assessment | [79,80] |

In order to facilitate worldwide standardization of the test and a more thorough determination of appropriate cut-off values, more longitudinal clinical studies taking into account bigger cohorts and repeated samples, in conjunction with meta-analyses, are crucial. Furthermore, d-ROMs' clinical importance will be better understood by cross-comparison with other oxidative-stress biomarkers and their inclusion in sizable panels of biomarkers linked to CVD. Finally, to com

The development of atherosclerotic plaque and the instability of the fibrous cap are both influenced by myeloperoxidase, and both raise the risk of atherosclerotic CVD, particularly CAD. Chaikijurajai and Tang[87] look at the pathophysiology of atherosclerotic CAD and the mechanistic information from a number of important therapeutic medication targets. The enzymatic activities of MPO are either directly or indirectly attenuated by prototype compounds, such as aminobenzoic acid hydrazide, ferulic acid derivative (INV-315), thiouracil derivatives (PF-1355 and PF-0628999), 2-thioxanthine derivative (AZM198), triazolopyrimidines, acetaminophen, N-acetyl lysyltyrosylcysteine (KYC), flavonoids, triazolopyrimidines, and alternative substrates like thiocyanate and nitroxide radicals. The cardiovascular advantages of direct systemic inhibition of MPO must be evaluated in future research to see if they exceed the danger of immunological dysfunction, which may be lower with other substrates or MPO inhibitors that specifically reduce MPO's atherogenic effects[87].

As a result, MPO mass and activity detection, measurement, and imaging have proven valuable in cardiac risk stratification for both disease evaluation and identifying patients who are susceptible to plaque rupture. With an emphasis on new developments to measure and visualize MPO in plasma and atherosclerotic plaques, as well as its potential roles in plaque rupture, this outlines the state of understanding about MPO's involvement in CAD[12]. Additionally, it examines MPO as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of unstable CAD and cardiac injury following MI, as well as the suggested mechanisms behind its harmful activities[53].

In conclusion, the degree of CAD and the likelihood of MACEs were closely connected with higher plasma levels of MPO, Hcy, and hsCRP in CAD patients. MPO, Hcy, and hsCRP are also clinically significant in assessing the condition and enhancing the prognosis for CAD patients, and they may be able to predict MACEs[57].

The current study indicates that EC-SOD activity is not very helpful in preventing CAD, and it also validates hs-IL-6 as a valuable marker for both clinical characterisation of CAD and diagnostic prevention[62]. According to Horiuchi et al[65], EC-SOD may be crucial in preventing elevated oxidative stress during acute ischemic coronary episodes.

A dependable, non-invasive biomarker for CAD severity prediction, elevated serum MDA may find use in clinical risk assessment and therapy plans. Early detection of individuals with high oxidative stress allows doctors to intervene promptly, which may delay the course of the disease and improve prognosis[68].

Elevated serum level MDA is a trustworthy, non-invasive biomarker for CAD severity prediction, and it may find use in clinical risk assessment and management plans. Clinicians may be able to decrease the course of the disease and im

When the cardiovascular system's antioxidant capacity is inadequate to lower ROS and other free radicals, oxidative stress may result. Atherosclerosis and incident CAD have been related to oxidative stress. Due to this association, early observational studies showed a negative correlation between major adverse CE and dietary antioxidant consumption, including β-carotene, α-tocopherol, and ascorbic acid. Many randomized trials of specific antioxidants as primary and secondary prophylaxis to lower heart risk were supported by these findings; nevertheless, many of these studies showed disappointing results, with little to no apparent risk reduction in individuals treated with antioxidants. A number of reasonable arguments have been put out for these results, including poor antioxidant selection or dosage, using synthetic antioxidants instead of dietary ones as the intervention, and patient selection. All of these factors will need to be taken into account when planning future clinical studies. The modern data that underpin present knowledge of the function of antioxidants in preventing CVD will be the main emphasis[88].

Dietary guidelines for lowering the risk of CHD have mostly concentrated on dietary consumption of nutrients that influence known risk factors, such as body weight, blood pressure, and levels of lipoproteins and plasma lipids. Recent advances in knowledge of the ischemia event-causing variables and the atherosclerosis process have prompted researchers to examine dietary components that may change risk in various ways. Among them, antioxidants are prominent because they are thought to prevent a number of oxidative processes in the arterial wall that are proatherogenic and prothrombotic[89].

The evidence supporting the role of dietary antioxidants in disease prevention is briefly reviewed in this report, with a focus on human population studies. It also outlines several issues that need to be addressed before it would be wise to recommend the prophylactic use of antioxidant supplements[89]. According to epidemiologic research, eating more fruits, vegetables, and whole grains may reduce your risk of CHD. Uncertainty surrounds whether antioxidant vitamins or other factors are responsible for this connection. Once possible nondietary and dietary confounding variables were taken into account, dietary consumption of antioxidant vitamins was only marginally associated with a lower risk of CHD[90].