Published online Feb 26, 2026. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.113358

Revised: September 28, 2025

Accepted: November 28, 2025

Published online: February 26, 2026

Processing time: 170 Days and 20.6 Hours

Sepsis, a common and severe infectious disease, remains one of the leading causes of mortality among patients, with myocardial injury representing a major con

To investigate the protective effects of melatonin on sepsis-induced myocardial injury and to elucidate the underlying mechanisms with a focus on the sirtuin 1/nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/glutathione peroxidase 4 pathway.

Male 57BL/6 mice were assigned to four groups: (1) The control group; (2) The lipopolysaccharide (LPS) group (15 mg/kg); (3) The LPS plus ferrostatin-1 group (ferroptosis inhibitor, 5 mg/kg); and (4) The LPS plus melatonin group (10 mg/kg). Cardiac function, myocardial injury, biochemical markers, and protein expression levels were evaluated using echocardiography, hematoxylin and eosin staining, biochemical assay kits, western blotting, and the cell counting kit-8 assay. To further investigate the effects of melatonin in vitro, HL-1 cardiomyocytes were subjected to the same treatment conditions.

Echocardiography and histological evaluation revealed significant impairments in cardiac function and marked myocardial tissue damage in the LPS group, whereas these pathological changes were alleviated in the LPS plus melatonin group. Treatment with melatonin significantly reduced serum levels of brain natriuretic peptide, lactate dehydrogenase, creatine kinase-MB, and cardiac troponin I, while improving myocardial reactive oxygen species and glutathione levels as well as su

The findings indicate that melatonin alleviates sepsis-induced myocardial injury by inhibiting ferroptosis through regulation of the sirtuin 1/nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/glutathione peroxidase 4 pathway, providing evidence supporting the potential use of melatonin in the treatment of sepsis-related myocardial injury.

Core Tip: Sepsis often results in myocardial injury, a major cause of death in affected patients. In this study, we demonstrated that melatonin, an endogenous hormone with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, protects against sepsis-induced myocardial injury. Using both a mouse model and HL-1 cardiomyocytes, we found that melatonin improved cardiac function, reduced oxidative stress, and inhibited ferroptosis by activating the sirtuin 1/nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/glutathione peroxidase 4 pathway. These findings provide novel mechanistic insights and highlight the therapeutic potential of melatonin for septic myocardial injury.

- Citation: Zeng M, Li Q, Li L, Xiang CF, Wang YJ. Melatonin regulates Sirt1/Nrf2/GPX4 pathway to inhibit ferroptosis and alleviate myocardial injury caused by sepsis. World J Cardiol 2026; 18(2): 113358

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v18/i2/113358.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.113358

Sepsis is a severe systemic condition caused by infection and is characterized by complex pathogenesis involving immune dysregulation, activation of inflammatory and coagulation systems, impaired pathogen recognition, alterations in gut microbiota, and multi-organ dysfunction[1]. These mechanisms interact and amplify each other, leading to poor clinical outcomes in patients with sepsis[2]. Among the various organ injuries associated with sepsis, myocardial injury is a major contributor to morbidity and mortality[3,4]. Septic myocardial injury is defined by both functional impairment and structural abnormalities of the heart, and despite continuous progress in clinical management, effective treatment strategies remain limited, thereby emphasizing the urgent need to explore new therapeutic approaches.

Melatonin is an endogenous hormone with a central role in regulating circadian rhythms, sleep-wake cycles, and antioxidant defense systems[5-7]. Beyond these physiological functions, it has been shown to possess anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and antioxidant properties[8,9]. Over the past decade, melatonin has attracted significant attention for its potential therapeutic benefits in various pathological conditions, especially cardiovascular diseases. Previous studies have demonstrated that melatonin attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by promoting mitochondrial fusion and mitophagy through activation of the AMPK-OPA1 pathway[10]; alleviates sepsis-induced myocardial injury by modulating the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway[11]; and reduces lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced cardiac injury by suppressing inflammatory responses and pyroptosis in cardiomyocytes[12]. These findings demonstrate that melatonin exerts cardioprotective effects through multiple mechanisms.

The pathophysiological processes underlying septic myocardial injury involve inflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction, which closely interact to drive myocardial damage[13,14]. Oxidative stress, defined as an imbalance between excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and insufficient antioxidant defenses, plays an important role in the onset and progression of septic myocardial injury[12,15]. Li et al[16] demonstrated that oxidative stress and inflammation exacerbate mitochondrial dysfunction, aggravating cellular damage and impairing cardiac function. Several molecular regulators are known to influence these processes. Sirtuin 1 (Sirt1), nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) are critical components of the antioxidant defense system, helping to maintain redox balance and mitochondrial integrity[17]. Clinical studies have suggested that Nrf2 expression in monocytes may predict prognosis in sepsis[18]. Collectively, these molecules exert protective effects by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation while preventing lipid peroxidation-induced cell death.

Although the cardioprotective properties of melatonin have been linked to several signaling pathways, the role of the Sirt1/Nrf2/GPX4 axis in septic myocardial injury has not been fully clarified. Sirtuin proteins are broadly involved in cellular aging, inflammation, and stress resistance, processes that are fundamental to myocardial health[19]. Previous evidence has shown that melatonin alleviates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity through activation of the Sirt1/Nrf2 pathway, thereby reducing oxidative stress, pyroptosis, and apoptosis[20]. Based on the central functions of Sirt1, Nrf2, and GPX4 in redox regulation and cell survival, it is plausible that melatonin may protect against septic myocardial injury through this signaling cascade.

Recent studies provide further support for this hypothesis. Melatonin has been reported to attenuate ferroptosis in sepsis-related organ injury by regulating the Nrf2/heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1)/GPX4 pathway, while Sirt1 activation has independently been recognized as cardioprotective under conditions of oxidative stress[21]. For example, melatonin was found to reduce septic acute kidney injury via Nrf2/HO-1/GPX4 signaling, and crosstalk between Sirt1 and Nrf2 has been identified as an important determinant of cardiac resilience[21]. However, whether melatonin regulates ferroptosis in septic cardiomyopathy specifically through the Sirt1/Nrf2/GPX4 pathway has not been established.

This study was designed to assess the effects of melatonin on cardiac function and myocardial injury in the LPS-induced mouse model of septic cardiomyopathy and to explore its protective mechanisms in HL-1 cardiomyocytes. We demonstrate, for the first time, that melatonin alleviates septic myocardial injury by activating the Sirt1/Nrf2/GPX4 pathway, thereby extending observations from other organ systems and providing new mechanistic evidence for cardioprotection in sepsis.

An acute sepsis-induced myocardial injury model was established in male C57BL/6 mice aged 6-8 weeks. Mice were allocated to four groups (n = 6 per group): (1) Control; (2) LPS; (3) LPS plus ferrostatin-1 (LPS + Fer-1); and (4) LPS plus melatonin (LPS + Mel). Control mice received an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of an equal volume of saline. The LPS group received LPS (15 mg/kg, i.p.). The LPS + Fer-1 group received LPS (15 mg/kg, i.p.) with Fer-1 (5 mg/kg, i.p.) administered 12 hours before LPS induction. The LPS + Mel group received LPS (15 mg/kg, i.p.) with melatonin (10 mg/kg, i.p.) administered 12 hours before LPS induction[22-24]. The in vivo melatonin dose (10 mg/kg) was selected based on published studies[22-24] and our preliminary data, with consideration of whole-organism metabolism and bioavailability relative to cell culture conditions. All procedures involving animals were reviewed and approved by the experimental animal Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial Medical Experimental Animal Center (No. D202404-12).

The mice were randomly assigned to groups using a computer-generated random sequence. Echocardiography acquisition and analysis, histopathology scoring, and biochemical and western blot quantification were performed by investigators blinded to group allocation. Cages were rotated and processed in random order to reduce batch effects.

HL-1 mouse cardiomyocytes were divided into the following treatment groups: (1) Control (standard culture); (2) LPS (5 μg/mL, L2880, Sigma) for 24 hours; (3) LPS + Fer-1 (pre-treatment with Fer-1, 5 μM, SML0583, Sigma, 24 hours, followed by LPS for 24 hours); (4) LPS + Mel (pre-treatment with melatonin, 10 μM, M5250, Sigma, 24 hours, followed by LPS for 24 hours); and (5) LPS + Mel + EX527 (pre-treatment with melatonin, 10 μM, and EX527, 10 μM, for 24 hours, followed by LPS for 24 hours).

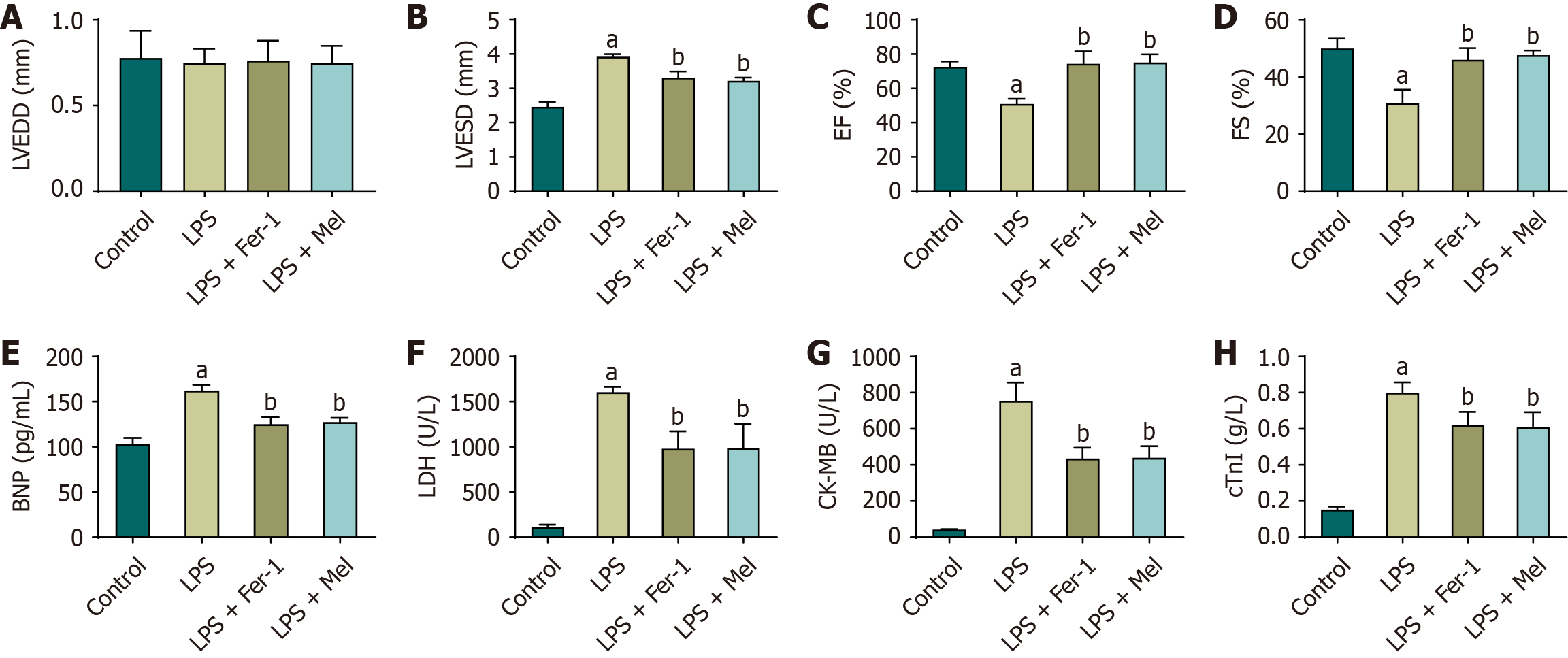

After 24 hours of LPS injection, cardiac function in each group of mice was assessed by measuring the left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD), ejection fraction (EF), and fractional shortening. Echocardiographic examinations were performed using a high-resolution imaging system equipped with a 15-MHz linear array transducer. Mice were anesthetized with 1%-2% isoflurane, and echocardiographic images were acquired in both parasternal long-axis and short-axis views. LVEDD was recorded at the end of diastole, while LVESD was measured at the end of systole. End-diastolic volume (EDV) and end-systolic volume (ESV) were calculated from left ventricular dimensions obtained from M-mode images at the mid-papillary muscle level, with EDV corresponding to the point of maximal LV filling and ESV corresponding to the point of maximal LV contraction.

EF was calculated using the formula: EF (%) = (EDV - ESV)/EDV × 100, and FS was calculated using the formula: FS (%) = (LVEDD - LVESD)/LVEDD × 100. All measurements were analyzed with specialized echocardiography software, ensuring accurate and reproducible quantification of cardiac function parameters.

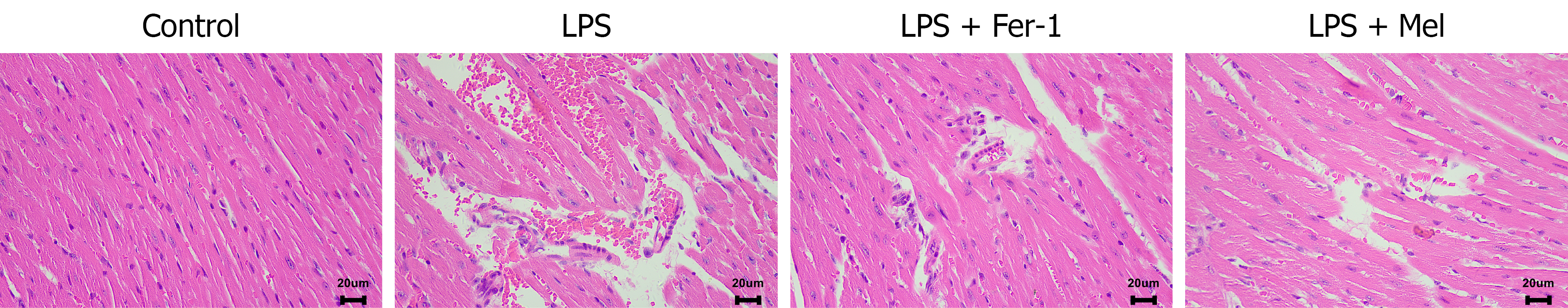

The heart tissues were collected from mice, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at a thickness of 4 μm, and mounted on glass slides. The slides were dried at 60 °C for 30 minutes and subsequently deparaffinized by immersion in xylene for 5 minutes, followed by two additional xylene changes. Rehydration was performed using a graded ethanol series (100%, 95%, and 70%) for 2 minutes each, after which the slides were rinsed in distilled water. Sections were stained with hematoxylin for 5 minutes and rinsed in running tap water for 5 minutes, followed by brief differentiation with 1% acid alcohol and another rinse in tap water. Bluing was achieved by immersion in 0.2% ammonia water for 1 minute. Counterstaining was performed with eosin for 2 minutes, after which the sections were dehydrated through graded ethanol (70%, 95%, and 100%), cleared in xylene, and mounted with coverslips. Pathological changes in myocardial tissue were then observed under a light microscope.

After echocardiography, the mice were euthanized with 2% pentobarbital sodium (120 mg/kg), and the samples were collected for subsequent western blotting and biochemical analyses. Serum and myocardial tissues from each group of mice, as well as HL-1 cells, were subjected to a series of assays to evaluate cardiovascular function and intracellular redox status. Serum levels of cardiovascular injury markers, including brain natriuretic peptide (YKW-20162, Youkewei, Shanghai), lactate dehydrogenase (EY-01H1701, Yiyan, Shanghai), creatine kinase-MB (YKW-20416, Youkewei, Shanghai), and cardiac troponin I (YKW-20425, Youkewei, Shanghai), were determined in the control, LPS, LPS + Fer-1, and LPS + Mel groups. To further evaluate oxidative stress, myocardial tissue and HL-1 cells were analyzed for malondialdehyde (MDA) (YKW-20605, Youkewei, Shanghai), glutathione (GSH) (YKW-20461, Youkewei, Shanghai), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) (YKW-20586, Youkewei, Shanghai) levels using commercial kits. In addition, total iron and ferrous iron (Fe2+) concentrations were measured in HL-1 cells to compare the effects of different treatments on cellular iron metabolism in the control, LPS, LPS + Fer-1, and LPS + Mel groups. Finally, MDA, GSH, total iron, and Fe2+ levels were also assessed in HL-1 cells from the control, LPS, LPS + Mel, and LPS + Mel + EX527 groups to investigate the influence of Sirt1 inhibition on melatonin’s regulatory effects.

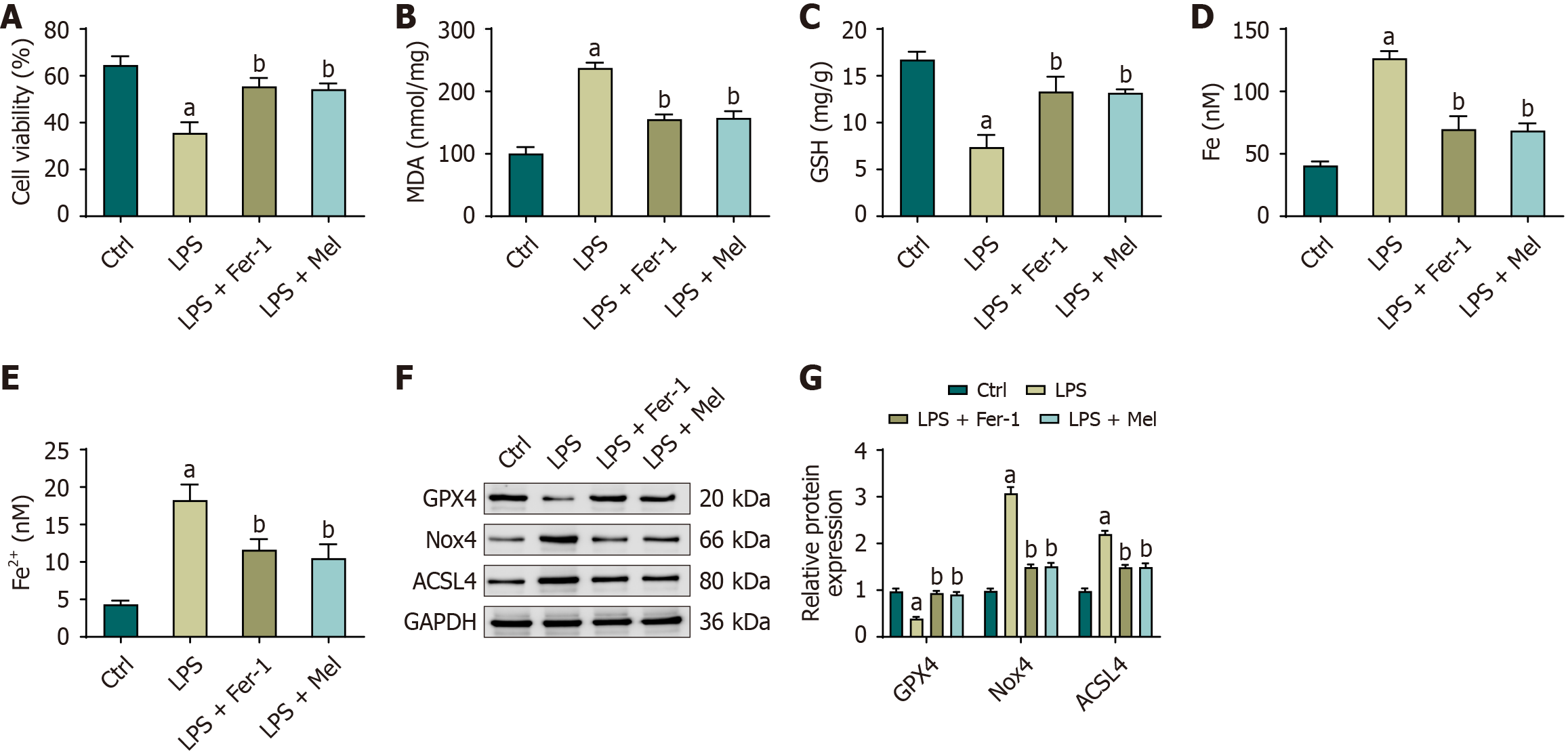

The cells were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2 until adherent growth was established. They were then divided into the control, LPS, LPS + Fer-1, LPS + Mel, and LPS + Mel + EX527 groups and treated with the respective solutions. After 24 hours of incubation, 10 μL of cell counting kit-8 solution (KGA317, KeyGen BioTECH) was added to each well, followed by a further incubation period of 2 hours. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader to evaluate cell viability. The experiment was performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

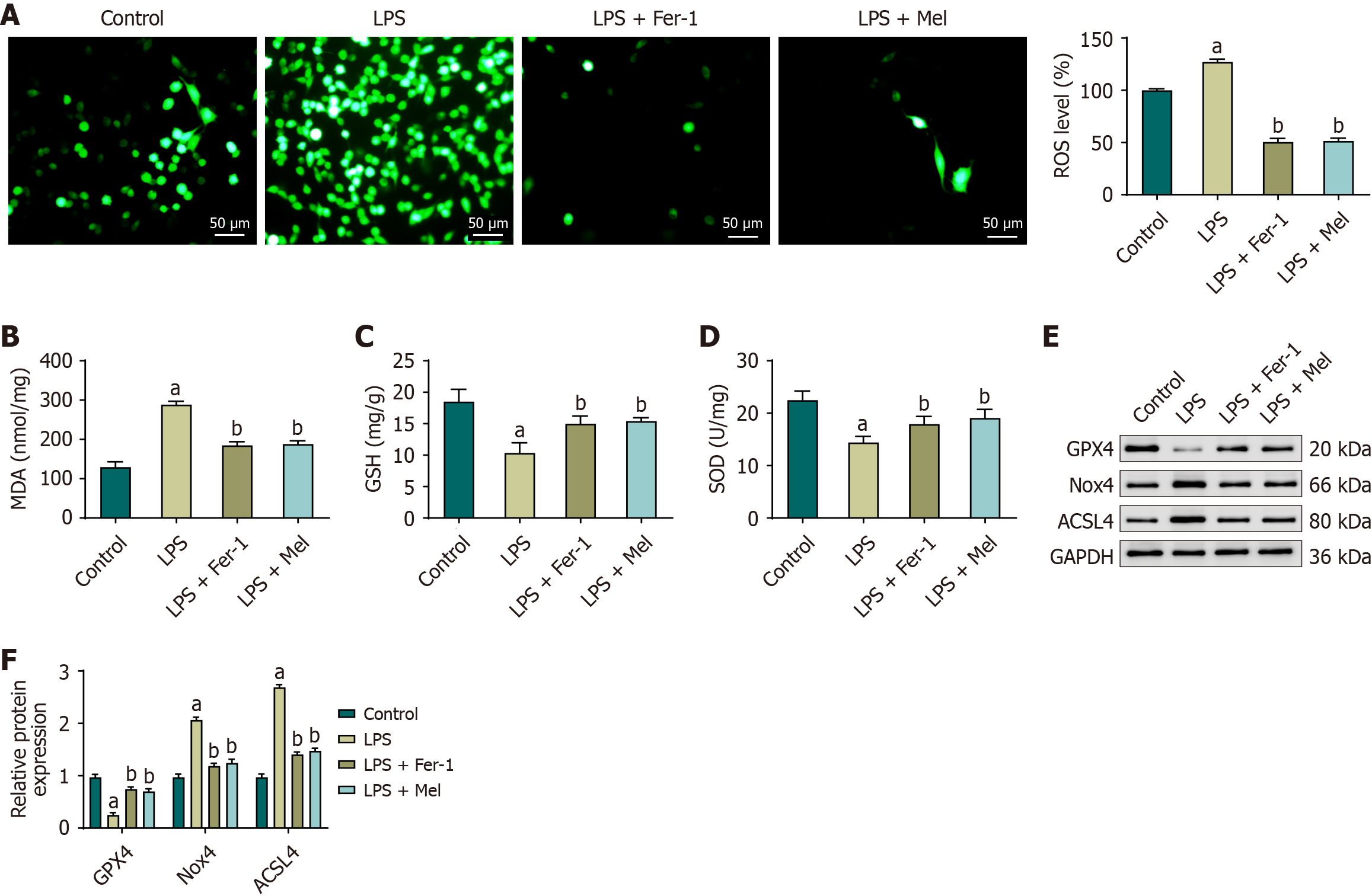

One day before detection, healthy cells were evenly seeded at an appropriate density into well plates and subjected to drug treatment according to the experimental protocol. The seeding density was adjusted according to the size and growth rate of the cells to ensure that confluence reached 50%-70% at the time of detection. Before staining, the culture medium was removed, and the cells were washed 1 time and 2 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer to minimize interference from serum and residual drugs. After washing, the buffer was aspirated, and an appropriate volume of 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (S0033S, Servicebio, China) was added. The plates were incubated at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator in the dark for 30 minutes. Following incubation, the working solution was removed, and the cells were washed 2 times and 3 times with PBS to remove excess probe. The cells were then covered with PBS. For ROS detection, labeled cells were mounted on glass slides, sealed with an anti-fluorescence quenching agent, and examined under a fluorescence or confocal microscope using an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 525 nm.

Cell and tissue lysates were first prepared, and protein concentrations were determined to ensure equal loading. Equal amounts of protein from each sample were mixed with loading buffer, denatured by heating, and then subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Electrophoresis was performed at 80 V for 10 minutes, followed by 120 V for 1.5 hours, to separate the proteins according to their molecular weight. The separated proteins were subsequently transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes at 120 V for 1.5 hours. To block nonspecific binding sites, the membranes were incubated with 5% skim milk in PBS-Tween at room temperature. After blocking, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against GPX4 (ab125066, Abcam, United Kingdom), NADPH oxidase 4 (Nox4, ab112414, Abcam, United Kingdom), acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4, ab155282, Abcam, United Kingdom), Sirt1 (ab110304, Abcam, United Kingdom), Nrf2 (ab62352, Abcam, United Kingdom), HO-1 (ab305290, Abcam, United Kingdom), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (ab8245, Abcam, United Kingdom), with GAPDH serving as the internal loading control. The membranes were then washed with PBS-Tween to remove unbound primary antibodies and incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies under appropriate conditions. After incubation with secondary antibodies, a second series of washes with PBS-Tween was performed to minimize background signal. Protein bands were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents, and images were acquired using a chemiluminescence detection system. Densitometric analysis was conducted with appropriate software to quantify relative protein expression levels normalized to GAPDH.

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and homogeneity of variance was assessed using Levene’s test. For comparisons among ≥ 3 groups, one-way analysis of variance was used, followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. Where data violated parametric assumptions, Kruskal-Wallis tests with Dunn’s multiple-comparison adjustment were applied. Two-group comparisons, when present, used Student’s t-test (parametric) or Mann-Whitney U test (non-parametric) as appropriate. The analyses were performed in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 26.0, and a two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ultrasound cardiography demonstrated that, compared with the control group, mice in the LPS group exhibited a significant reduction in EF and FS, accompanied by a significant increase in LVESD, while no significant difference was observed in LVEDD. When compared with the LPS group, both the LPS + Fer-1 and LPS + Mel groups showed significant improvements, with EF and FS markedly increased and LVESD significantly decreased, whereas LVEDD remained unchanged. No statistically significant differences were found between the LPS + Fer-1 and LPS + Mel groups (Figure 1A-D). Biochemical analyses further supported these findings. Compared to the control group, the serum levels of brain natriuretic peptide, lactate dehydrogenase, creatine kinase-MB, and cardiac troponin I were significantly elevated in the LPS group, reflecting the presence of myocardial injury. In contrast, treatment with either Fer-1 or melatonin significantly reduced these biomarkers compared with the LPS group, and no significant differences were detected between the LPS + Fer-1 and LPS + Mel groups (Figure 1E-H).

Histopathological evaluation by hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2) revealed pronounced differences in myocardial tissue morphology among the groups. The control group displayed normal myocardial tissue with intact architecture and no pathological changes. In contrast, the LPS group exhibited severe myocardial injury characterized by extensive interstitial edema, vascular congestion, hemorrhage, myofibrillar dissolution, and marked infiltration of inflammatory cells. Treatment with Fer-1 or melatonin markedly improved these pathological changes, with both interventions leading to reduced interstitial edema, decreased inflammatory infiltration, and better preservation of myofibrillar organization, thereby demonstrating their protective effects against LPS-induced myocardial damage.

In the cardiac tissue of mice in the LPS group, ROS levels were markedly elevated, with a corresponding increase in intracellular fluorescence intensity. In contrast, ROS levels were significantly reduced in the LPS + Fer-1 and LPS + Mel groups, and fluorescence signals were visibly diminished (Figure 3A). Consistent with these findings, levels of MDA were significantly elevated in the LPS group, whereas levels of GSH and SOD activity were markedly decreased. Treatment with Fer-1 or melatonin significantly reversed these changes, as evidenced by decreased MDA levels and increased GSH content and SOD activity compared with the LPS group. No statistically significant differences were observed between the LPS + Fer-1 and LPS + Mel groups (Figure 3B-D).

Western blot analysis further confirmed these trends. In cardiac tissue from the LPS group, GPX4 expression was significantly reduced, while Nox4 and ACSL4 expression levels were significantly upregulated compared with the control group. In contrast, both the LPS + Fer-1 and LPS + Mel groups showed significant increases in GPX4 expression, accompanied by significant decreases in Nox4 and ACSL4 expression relative to the LPS group. Again, no statistically significant differences were observed between the LPS + Fer-1 and LPS + Mel groups (Figure 3E and F).

The viability of HL-1 cells was markedly reduced in the LPS group compared with the control group. In contrast, pre-treatment with either Fer-1 or melatonin significantly improved cell viability in the LPS + Fer-1 and LPS + Mel groups relative to the LPS group, with no statistically significant differences observed between the two treatment groups. Consistent with these findings, HL-1 cells in the LPS group exhibited significantly increased levels of MDA, total iron, and Fe2+, accompanied by a significant reduction in GSH levels compared with the control group. Pre-treatment with Fer-1 or melatonin effectively reversed these alterations, as evidenced by decreased levels of MDA, total iron, and Fe2+ and increased GSH levels in both treatment groups. Again, no statistically significant differences were detected between the LPS + Fer-1 and LPS + Mel groups in these parameters. Collectively, these findings indicate that melatonin exerts a protective effect against LPS-induced oxidative stress (Figure 4A-E).

Western blot analysis further corroborated these results. In HL-1 cells exposed to LPS, GPX4 expression was significantly reduced, whereas Nox4 and ACSL4 expression levels were significantly elevated compared with the control group. However, in the LPS + Mel group, GPX4 expression was markedly increased, while Nox4 and ACSL4 expression levels were significantly decreased. These results suggest that melatonin alleviates oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation by upregulating GPX4 and downregulating Nox4 and ACSL4 expression (Figure 4F and G).

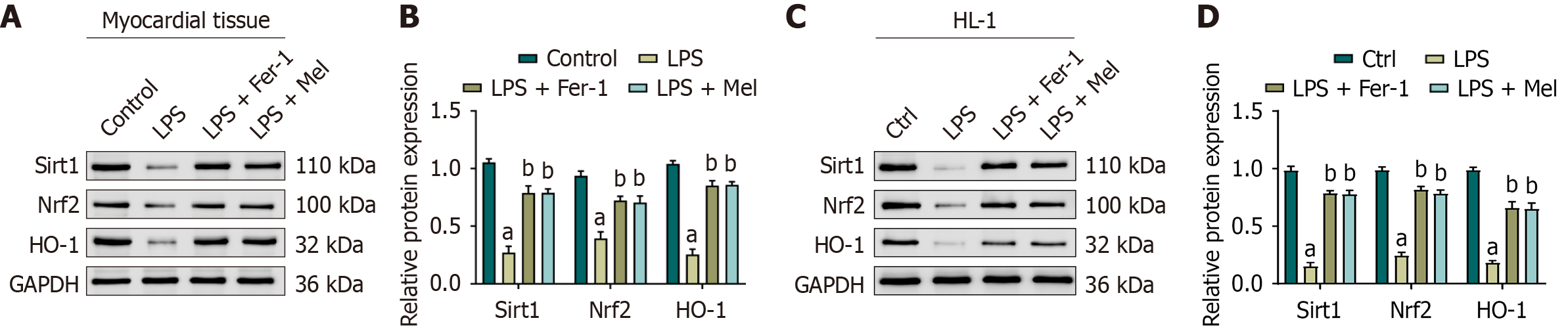

In the cardiac tissue of mice exposed to LPS, the protein expression levels of Sirt1, Nrf2, and HO-1 were significantly reduced compared to the control group. In contrast, treatment with either Fer-1 or melatonin significantly increased the expression of these proteins relative to the LPS group, and no statistically significant differences were detected between the LPS + Fer-1 and LPS + Mel groups (Figure 5A and B). Similar findings were observed in HL-1 cells, in which LPS exposure led to a significant reduction in Sirt1, Nrf2, and HO-1 expression compared with the control group. Treatment with Fer-1 or melatonin significantly restored the expression levels of these proteins, again with no significant difference between the two treatment groups (Figure 5C and D). Collectively, these results indicate that both in mouse cardiac tissue and in HL-1 cells, LPS suppresses the expression of Sirt1, Nrf2, and HO-1, whereas Fer-1 and melatonin counteract this effect, thereby enhancing protein expression that may contribute to antioxidant and anti-inflammatory protection.

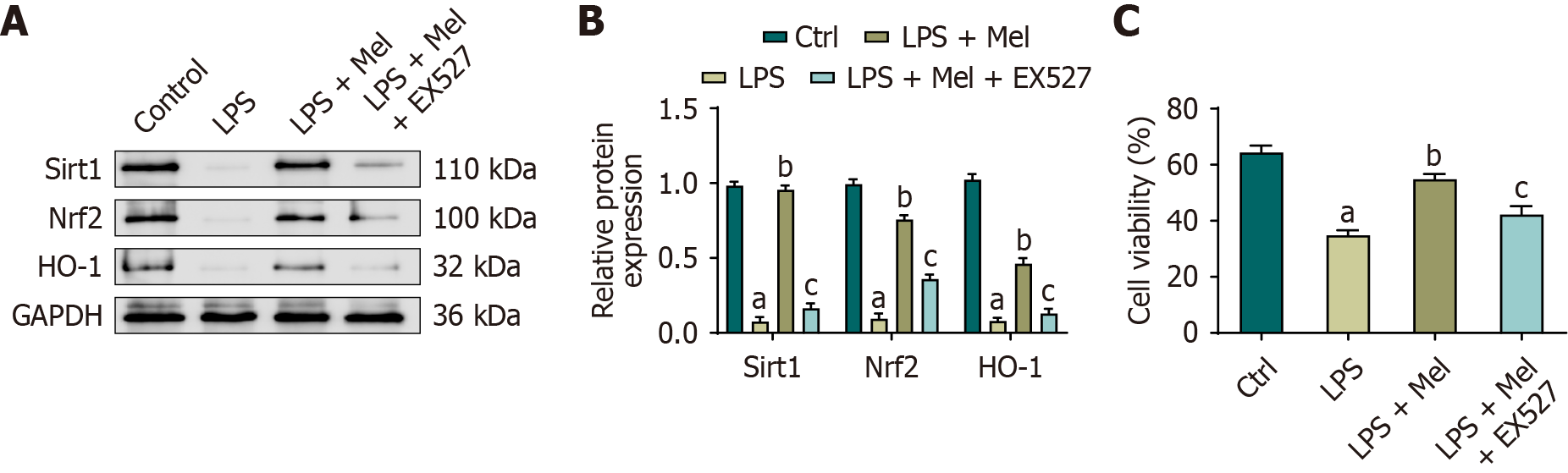

The protein expression levels of Sirt1, Nrf2, and HO-1 were significantly decreased in HL-1 cells exposed to LPS, accompanied by reduced cell viability. Melatonin treatment significantly restored the expression of Sirt1, Nrf2, and HO-1, along with a parallel improvement in cell viability. Upon addition of the Sirt1 inhibitor EX527, these melatonin-induced increases in Sirt1, Nrf2, and HO-1 expression were attenuated, and cell viability was correspondingly reduced (Figure 6A and B). Although GPX4 was not directly assessed under EX527 inhibition, our complementary in vivo and in vitro results (Figures 3 and 4) demonstrated consistent GPX4 upregulation with melatonin. Together, these findings indicate that melatonin enhances the Sirt1/Nrf2 axis, leading to the activation of downstream targets such as HO-1 and GPX4, thereby improving cell survival under LPS-induced injury (Figure 6C).

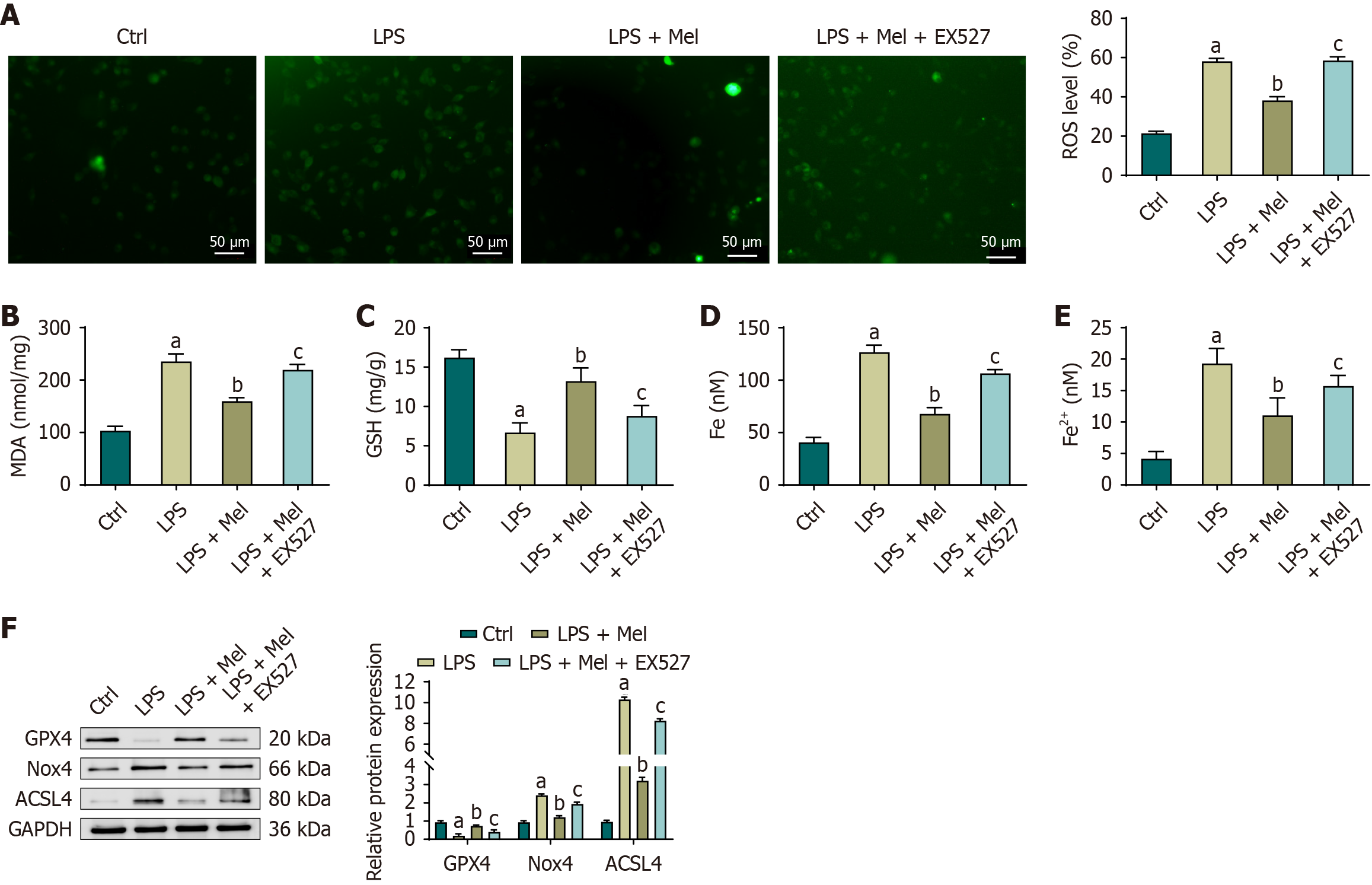

In HL-1 cells, LPS exposure led to a marked disturbance in redox homeostasis. Compared with the control group, levels of ROS, MDA, total iron, and Fe2+ were significantly increased, whereas GSH levels were significantly decreased. Treatment with melatonin effectively reversed these changes, as levels of MDA, total iron, and Fe2+ were significantly reduced and GSH levels were significantly elevated in the LPS + Mel group relative to the LPS group. However, the protective effect of melatonin was diminished when Sirt1 was inhibited. In the LPS + Mel + EX527 group, levels of ROS, MDA, total iron, and Fe2+ were significantly increased, while GSH levels were significantly decreased compared with the LPS + Mel group. Western blot analysis further confirmed these findings. Compared with the control group, LPS significantly reduced GPX4 expression while increasing Nox4 and ACSL4 expression in HL-1 cells. Treatment with melatonin restored GPX4 levels and reduced Nox4 and ACSL4 expression compared with the LPS group, consistent with its antioxidative and anti-lipid peroxidation effects. However, when Sirt1 activity was inhibited by EX527, GPX4 expression was significantly reduced, and Nox4 and ACSL4 expression levels were significantly increased compared with the LPS + Mel group. These results suggest that melatonin protects HL-1 cells from LPS-induced oxidative damage and lipid peroxidation primarily through a Sirt1-dependent mechanism (Figure 7).

Myocardial injury represents a leading cause of mortality in patients with sepsis[25]. In the early stages of sepsis, the body produces large amounts of inflammatory cytokines, which induce oxidative stress in cardiomyocytes, leading to membrane damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis, ultimately causing cardiac dysfunction and heart failure[26]. In this study, we found that melatonin markedly reduced sepsis-induced myocardial injury by regulating the Sirt1/Nrf2/GPX4 pathway, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis and improving cardiac function, providing new insight into the cardioprotective role of melatonin and indicating its potential as a therapeutic option for sepsis-related myocardial injury. From a clinical perspective, this suggests that melatonin could be developed as a treatment to improve outcomes in patients with septic myocardial injury, addressing an urgent need in the management of this serious condition.

Melatonin exerts a wide range of physiological functions in the human body, including the regulation of circadian rhythms, the reduction of oxidative stress, and the inhibition of inflammatory responses[26]. Thonusin et al[27] reported that melatonin exerts protective effects on the cardiovascular system and reduces myocardial injury caused by conditions such as ischemia-reperfusion injury, myocardial infarction, and heart failure. Similarly, Zhang et al[20] demonstrated that melatonin protects cardiomyocytes by regulating antioxidant and anti-inflammatory pathways, thereby reducing oxidative damage and inflammatory responses. Consistent with these reports, our experiments in mice and HL-1 cells confirmed that melatonin significantly reduced sepsis-induced myocardial injury and improved myocardial function. These results strengthen the understanding of the protective role of melatonin in the heart and provide a theoretical foundation for its potential clinical application in sepsis-induced myocardial injury.

In recent years, multiple strategies have been investigated to attenuate ferroptosis in septic cardiomyopathy and related conditions[28]. Fer-1, a canonical ferroptosis inhibitor, has been widely employed in preclinical studies[29] and was included as a positive control in our experiments, showing comparable cardioprotective effects to melatonin. Dexmedetomidine has also been reported to alleviate septic cardiomyopathy by activating Nrf2 and suppressing ferroptosis[30]. Compared with these synthetic or pharmacological agents, melatonin offers the unique advantage of being an endogenous hormone with established safety, pleiotropic effects on circadian regulation, and the capacity to modulate oxidative stress and inflammation simultaneously[5]. These properties may enhance its translational potential as a clinically applicable adjunct therapy. Nevertheless, challenges remain. The pharmacokinetics, optimal dosage, and timing of melatonin administration in septic patients are not fully defined. In particular, our study employed a preventive design with melatonin administered prior to LPS challenge, whereas clinical treatment usually begins after sepsis onset. Future studies should therefore investigate therapeutic administration schedules, dose-response relationships, and pharmacodynamic variability in septic patients to establish the clinical feasibility of melatonin as a ferroptosis-targeting therapy.

Further molecular biology experiments revealed that melatonin inhibited ferroptosis by regulating the Sirt1/Nrf2/GPX4 pathway, thereby protecting cardiomyocytes from oxidative stress damage. EX527, a Sirt1 inhibitor, reversed the improvements in cardiac function and oxidative stress markers observed with melatonin[31], indicating that the beneficial effects of melatonin are mediated, at least in part, through the Sirt1 pathway. In this inhibition setting, HO-1 was used as a representative Nrf2 target, and GPX4 was not directly quantified. While this limits definitive confirmation of the full Sirt1/Nrf2/GPX4 cascade under Sirt1 inhibition, our complementary results in vivo and in vitro (Figures 3, 4, and 7) demonstrated promising GPX4 upregulation with melatonin. Together, these findings support that melatonin acts through the Sirt1/Nrf2 pathway and converges on GPX4 to inhibit ferroptosis. It should also be noted that Fer-1, like melatonin, restored Sirt1/Nrf2/HO-1 expression. This raises an open question: Does Sirt1 activation occur upstream to inhibit ferroptosis, or downstream as a result of ferroptosis suppression? The present design cannot resolve this sequence, but our data do confirm that Sirt1 is essential for melatonin’s effects. Future studies could include direct GPX4 assessment under Sirt1 inhibition to further validate this mechanistic link and determine whether Sirt1 activation occurs upstream to suppress ferroptosis or downstream as a consequence of ferroptosis inhibition.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated the protective effects of melatonin in different models of cardiac injury. For example, it has been reported that melatonin alleviated arsenic-induced cardiotoxicity in rats by regulating the Sirt1/Nrf2 pathway, and that melatonin treatment, either alone or in combination with conventional antibiotics, protected the myocardium from sepsis-induced damage[32]. Building on these earlier observations, our study further emphasizes the importance of ferroptosis inhibition through the Sirt1/Nrf2/GPX4 pathway in the context of septic myocardial injury. Looking ahead, the mechanism of melatonin demonstrated in our work may provide a reference for the design and development of new drugs, particularly those that target the Sirt pathway, to treat cardiovascular diseases associated with oxidative stress and inflammation.

By employing rigorous animal and cellular experimental designs, together with echocardiography, biochemical assays, and protein expression analyses, we comprehensively evaluated the effects of melatonin on septic myocardial injury and identified a new mechanism involving regulation of the Sirt1/Nrf2/GPX4 pathway. Nonetheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, melatonin was administered 12 hours before LPS challenge, reflecting a preventive rather than therapeutic approach, which does not fully represent clinical practice. Future studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy of melatonin when administered after sepsis onset. Second, although we confirmed that melatonin increased Sirt1 expression in vivo, inhibition of Sirt1 was examined only in vitro using EX527 in HL-1 cells. In vivo validation through pharmacological inhibition or genetic knockout models will be required to more definitively establish the mechanistic role of Sirt1. Third, the findings of this study have not yet been tested in clinical patients, and further clinical trials are necessary to assess feasibility and safety in a clinical context. Lastly, the potential for combining melatonin with other therapeutic modalities was not investigated, and additional studies may identify more effective treatment strategies.

In summary, this study demonstrated that melatonin may offer protection against sepsis-induced myocardial injury by inhibiting ferroptosis through activation of the Sirt1/Nrf2/GPX4 pathway. Inhibition of Sirt1 attenuated the protective effects of melatonin, as reflected by reduced Nrf2 activity and diminished expression of its downstream targets, including HO-1 and GPX4. Although GPX4 was not directly examined under Sirt1 inhibition, our complementary experiments confirmed its upregulation by melatonin. Collectively, these results provide mechanistic evidence that melatonin exerts cardioprotective effects via the Sirt1/Nrf2/GPX4 axis and support its potential therapeutic significance in septic myocardial injury.

| 1. | Jacobi J. The pathophysiology of sepsis-2021 update: Part 1, immunology and coagulopathy leading to endothelial injury. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2022;79:329-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wiersinga WJ, van der Poll T. Immunopathophysiology of human sepsis. EBioMedicine. 2022;86:104363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Srzić I, Nesek Adam V, Tunjić Pejak D. Sepsis Definition: What's New in the Treatment Guidelines. Acta Clin Croat. 2022;61:67-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bleakley G, Cole M. Recognition and management of sepsis: the nurse's role. Br J Nurs. 2020;29:1248-1251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Boutin JA, Kennaway DJ, Jockers R. Melatonin: Facts, Extrapolations and Clinical Trials. Biomolecules. 2023;13:943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | de Carvalho JF, Skare TL. Melatonin supplementation improves rheumatological disease activity: A systematic review. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2023;55:414-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ahmad SB, Ali A, Bilal M, Rashid SM, Wani AB, Bhat RR, Rehman MU. Melatonin and Health: Insights of Melatonin Action, Biological Functions, and Associated Disorders. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2023;43:2437-2458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 39.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sarkar S, Das A, Mitra A, Ghosh S, Chattopadhyay S, Bandyopadhyay D. An integrated strategy to explore the potential role of melatonin against copper-induced adrenaline toxicity in rat cardiomyocytes: Insights into oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;120:110301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hosseinzadeh A, Pourhanifeh MH, Amiri S, Sheibani M, Irilouzadian R, Reiter RJ, Mehrzadi S. Therapeutic potential of melatonin in targeting molecular pathways of organ fibrosis. Pharmacol Rep. 2024;76:25-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Skeie JM, Nishimura DY, Wang CL, Schmidt GA, Aldrich BT, Greiner MA. Mitophagy: An Emerging Target in Ocular Pathology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021;62:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhen G, Liang W, Jia H, Zheng X. Melatonin relieves sepsis-induced myocardial injury via regulating JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Minerva Med. 2022;113:983-989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Su ZD, Wei XB, Fu YB, Xu J, Wang ZH, Wang Y, Cao JF, Huang JL, Yu DQ. Melatonin alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced myocardial injury by inhibiting inflammation and pyroptosis in cardiomyocytes. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9:413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Megha KB, Arathi A, Shikha S, Alka R, Ramya P, Mohanan PV. Significance of Melatonin in the Regulation of Circadian Rhythms and Disease Management. Mol Neurobiol. 2024;61:5541-5571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Xiao Z, Long J, Zhang J, Qiu Z, Zhang C, Liu H, Liu X, Wang K, Tang Y, Chen L, Lu Z, Zhao G. Administration of protopine prevents mitophagy and acute lung injury in sepsis. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1104185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ali SA, Bommaraju S, Patwa J, Khare P, Rachamalla M, Niyogi S, Datusalia AK. Melatonin Attenuates Extracellular Matrix Accumulation and Cardiac Injury Manifested by Copper. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2023;201:4456-4471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li S, Li X, Xie F, Bai Y, Ma J. Melatonin reduces myocardial cell damage in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion rats by inhibiting NLRP3 activation. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2023;69:259-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhang Y, Kong F, Li N, Tao L, Zhai J, Ma J, Zhang S. Potential role of SIRT1 in cell ferroptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2025;13:1525294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Li L, Zhang Q, Zhang X, Xu X, Wang X, Huang X, Wang T, Jiang Z, Xiao L, Zhang L, Sun L. Protective effects of Nrf2 against sepsis-induced hepatic injury. Life Sci. 2021;282:119807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ding YN, Wang HY, Chen XF, Tang X, Chen HZ. Roles of Sirtuins in Cardiovascular Diseases: Mechanisms and Therapeutics. Circ Res. 2025;136:524-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhang W, Wang X, Tang Y, Huang C. Melatonin alleviates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via inhibiting oxidative stress, pyroptosis and apoptosis by activating Sirt1/Nrf2 pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;162:114591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhang P, Liu W, Wang S, Wang Y, Han H. Ferroptosisand Its Role in the Treatment of Sepsis-Related Organ Injury: Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutic Approaches. Infect Drug Resist. 2024;17:5715-5727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhang J, Wang L, Xie W, Hu S, Zhou H, Zhu P, Zhu H. Melatonin attenuates ER stress and mitochondrial damage in septic cardiomyopathy: A new mechanism involving BAP31 upregulation and MAPK-ERK pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:2847-2856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhong J, Tan Y, Lu J, Liu J, Xiao X, Zhu P, Chen S, Zheng S, Chen Y, Hu Y, Guo Z. Therapeutic contribution of melatonin to the treatment of septic cardiomyopathy: A novel mechanism linking Ripk3-modified mitochondrial performance and endoplasmic reticulum function. Redox Biol. 2019;26:101287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yu LM, Dong X, Huang T, Zhao JK, Zhou ZJ, Huang YT, Xu YL, Zhao QS, Wang ZS, Jiang H, Yin ZT, Wang HS. Inhibition of ferroptosis by icariin treatment attenuates excessive ethanol consumption-induced atrial remodeling and susceptibility to atrial fibrillation, role of SIRT1. Apoptosis. 2023;28:607-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Frencken JF, van Smeden M, van de Groep K, Ong DSY, Klein Klouwenberg PMC, Juffermans N, Bonten MJM, van der Poll T, Cremer OL; MARS Consortium. Etiology of Myocardial Injury in Critically Ill Patients with Sepsis: A Cohort Study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022;19:773-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Reiter RJ, Sharma R, Chuffa LGA, Simko F, Dominguez-Rodriguez A. Mitochondrial Melatonin: Beneficial Effects in Protecting against Heart Failure. Life (Basel). 2024;14:88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Thonusin C, Nawara W, Arinno A, Khuanjing T, Prathumsup N, Ongnok B, Chattipakorn SC, Chattipakorn N. Effects of melatonin on cardiac metabolic reprogramming in doxorubicin-induced heart failure rats: A metabolomics study for potential therapeutic targets. J Pineal Res. 2023;75:e12884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Scarpellini C, Klejborowska G, Lanthier C, Hassannia B, Vanden Berghe T, Augustyns K. Beyond ferrostatin-1: a comprehensive review of ferroptosis inhibitors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2023;44:902-916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 46.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Li F, Hu Z, Huang Y, Zhan H. Dexmedetomidine ameliorates diabetic cardiomyopathy by inhibiting ferroptosis through the Nrf2/GPX4 pathway. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2023;18:223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Pi QZ, Wang XW, Jian ZL, Chen D, Zhang C, Wu QC. Melatonin Alleviates Cardiac Dysfunction Via Increasing Sirt1-Mediated Beclin-1 Deacetylation and Autophagy During Sepsis. Inflammation. 2021;44:1184-1193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Zhang L, Zou L, Jiang X, Cheng S, Zhang J, Qin X, Qin Z, Chen C, Zou Z. Stabilization of Nrf2 leading to HO-1 activation protects against zinc oxide nanoparticles-induced endothelial cell death. Nanotoxicology. 2021;15:779-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Yarmohammadi F, Barangi S, Aghaee-Bakhtiari SH, Hosseinzadeh H, Moosavi Z, Reiter RJ, Hayes AW, Mehri S, Karimi G. Melatonin ameliorates arsenic-induced cardiotoxicity through the regulation of the Sirt1/Nrf2 pathway in rats. Biofactors. 2023;49:620-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |