INTRODUCTION

Hypertension, also known as high blood pressure, is a major worldwide health issue, with an estimated 1.13 billion individuals affected globally, as reported by the World Health Organization[1]. Hypertension is regarded as a significant risk factor for cardiovascular diseases such as myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and heart failure[2]. Recent projections indicate that almost 9.4 million deaths every year are caused by complications of uncontrolled hypertension, with the majority these deaths occurring in low- and middle-income nations[3,4]. In the United States alone, almost 45% of adults have hypertension, with only and only 1 in 4 of patients having controlled blood pressure[5]. Therefore, the control of hypertension is essential to avoid these serious and lethal cardiovascular.

Pharmacological agents are often prescribed in the treatment of hypertension. One class of agents are thiazide diuretics[6], which increase sodium and water excretion within the kidney to reduce blood volume and, in turn, blood pressure[7]. Chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide are two of the most commonly used thiazide diuretic[8] and are recommended by international guidelines as the first-line treatment for primary hypertension. Yet, despite their administration, controversy exists within the literature regarding their relative efficacy in cardiovascular outcomes.

Chlorthalidone has traditionally been concluded as having greater efficacy compared to hydrochlorothiazide in hypertension, which is attributed to its long half-life, which enables 24-hour control of blood pressure[9]. According to Khenhrani et al[10] study, chlorthalidone was reported to have a greater efficacy of than hydrochlorothiazide in lowering systolic blood pressure by a mean of 4-5 mmHg among patients with hypertension. However, clinician favor the prescription of hydrochlorothiazide, due to its low side effect profile and greater cost-effectiveness, especially in patients who require moderate blood pressure control[11,12]. In addition, Racial differences in hypertension treatment are crucial because prevalence, underlying physiology, and drug response vary across populations. For example, Black patients often have higher rates of salt-sensitive, low-renin hypertension, which influences the efficacy of thiazide-type diuretics, including chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide[13,14]. Evidence shows that blood pressure reduction and adverse-effect profiles may differ by race, yet many major trials under-represent minority groups, limiting generalizability. Addressing these differences ensures that treatment recommendations are equitable, clinically relevant, and better tailored to diverse patient populations[13,15]. It is noted that the comparative safety and efficacy, between the two medications are unresolved in some clinical situations, as an example, chlorthalidone has been shown to have increased hypokalemia, potentially hazardous electrolyte disturbance, more than hydrochlorothiazide[15]. However, hydrochlorothiazide has been established to have lower rates of cardiovascular complications, albeit at the cost of possibly a lesser degree of blood pressure control, especially over long periods[16,17].

Recent research has evidenced that although both drugs lower blood pressure efficiently, their efficacy on cardiovascular events difference. For instance, Hripcsak et al[18] reported that chlorthalidone was associated with a decreased risk of MI in comparison to hydrochlorothiazide, although this finding was not consistent within in all patient subgroups. In addition, studies have varied on the influence of these drugs on stroke risk. For example, a meta-analysis by Khenhrani et al[10] did not detect a difference between the two medications in the prevention of stroke. However, Dorsch et al[19] study reported that chlorthalidone significantly decreased the risk of stroke risk among adults with comorbid conditions, such as diabetes compared to hydrochlorothiazide.

Given the ambiguity of the literature in the comparison of chlorthalidone to hydrochlorothiazide, this meta-analysis aims to systematically compare the efficacy and safety of hydrochlorothiazide and chlorthalidone in the management of primary hypertension. The primary aim is to assess the efficacy in reduction of systolic and diastolic blood pressure. The secondary aim is to assess the efficacy of the prevention of major adverse cardiovascular events such as MI, stroke, heart failure. Furthermore, we discuss the potential application of these drugs in regulating nocturnal blood pressure, a crucial determinant in the prevention of cardiovascular events.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

A literature search was conducted using the PubMed and Google Scholar databases up to March 30, 2025, to compare the efficacy and safety of chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide in patients with hypertension, with a particular focus on their effects on MI and stroke outcomes. Keywords such as “hydrochlorothiazide”, “chlorthalidone”, “hypertension”, “cardiovascular”, and “blood pressure” were utilized. Boolean operators, specifically the AND operation, were applied to refine the search results: (hydrochlorothiazide) AND (chlorthalidone) AND (hypertension) AND (cardiovascular) AND (blood pressure). Manual screening of reference lists from included studies and relevant reviews was also conducted to identify additional eligible studies.

Inclusion criteria

(1) Studies comparing chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide in patients with hypertension; (2) Articles reporting data on outcomes such as blood pressure control, MI, and stroke; (3) Randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, or clinical studies published in peer-reviewed journals; (4) Studies involving adult populations (≥ 18 years) diagnosed with primary hypertension; (5) Studies published in English; and (6) Articles published from 2005 to the March 30, 2025.

Exclusion criteria

(1) Review articles, editorials, case reports, and conference abstracts without original data; (2) Studies that did not include comparisons between chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide; (3) Articles lacking outcome data related to blood pressure, MI, or stroke; (4) Studies involving pediatric populations or patients with secondary causes of hypertension; and (5) Duplicate publications of the same study or studies with incomplete data.

Study selection and inclusion

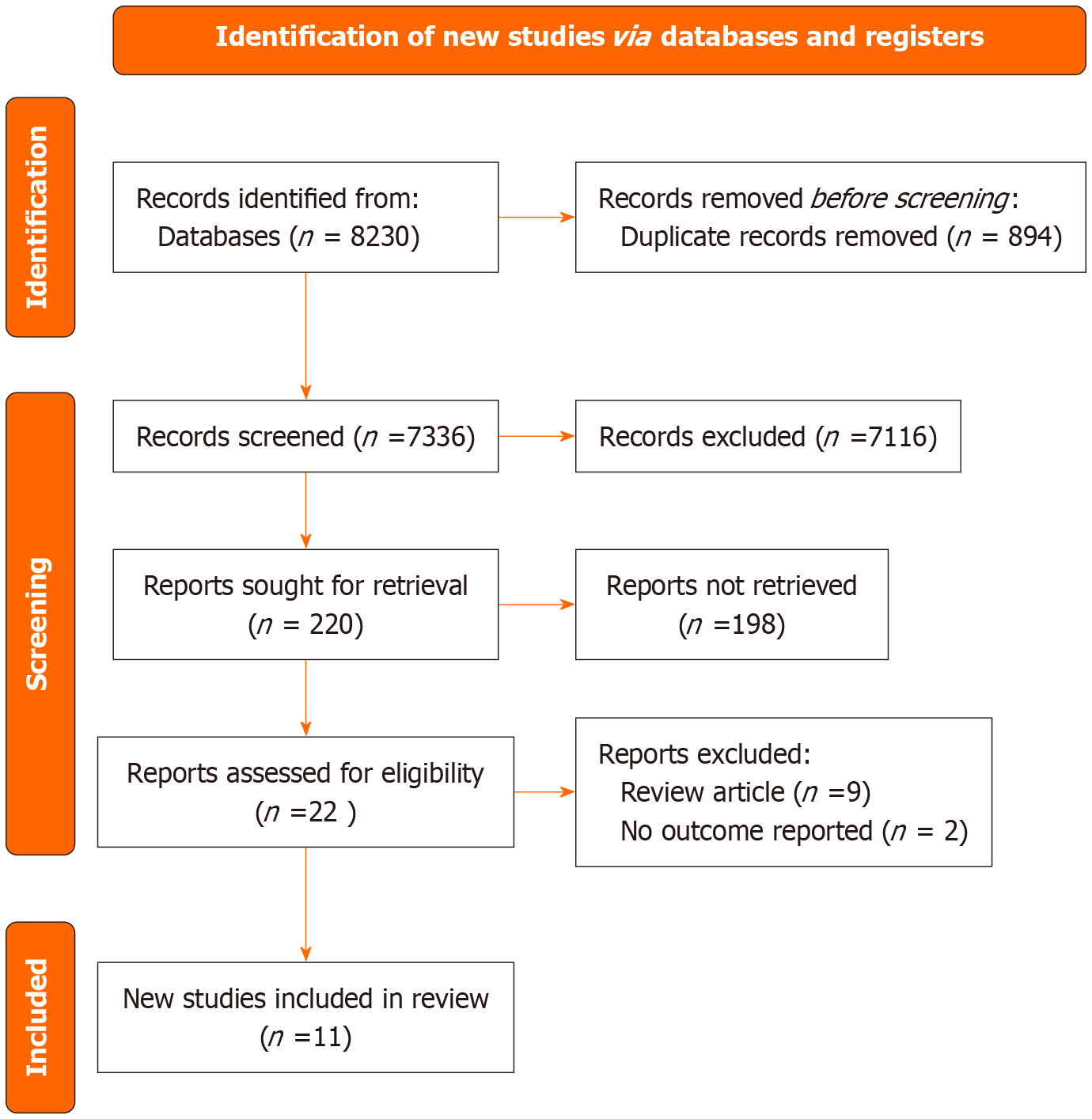

The initial search yielded 8230 records, comprising 80 from PubMed and 8150 from Google Scholar. Duplicate records (n = 894) were removed, leaving 7336 unique records for screening. After title and abstract screening, 7116 records were excluded based on the inclusion criteria. Subsequently, 220 full-text articles were sought for retrieval; however, 198 articles could not be accessed. Of 22 reports were assessed for eligibility, and 11 studies were finally included in the review, as illustrated in the Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis chart (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis flowchart representing the selection process inclusion of studies.

Adapted from Cochrane Methods Bias[20].

Data extraction and quality assessment

The following data was extracted: Study name, publication year, first author, study design, type of thiazide diuretic used, total participants, follow-up duration, dosage and frequency of intervention, outcomes related to efficacy (mortality rates, MI incidence, stroke incidence, blood pressure measurements), and safety (frequency of adverse events, type of adverse events) of the thiazides given, using a preformed standardized excel sheet. Not all included studies defined each extracted outcome the same, and these variations were considered in our interpretation and are reported in the limitations section of this paper. The quality assessment of the selected randomized controlled trials was performed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool[20]; while the Newcastle-Ottawa scale was employed to evaluate the quality of the included observational studies[21]. Each study was assessed individually, and the potential risk of bias for each outcome was summarized as low, high, or unclear. Biases were assessed in the following five domains: (1) Bias caused by randomization process; (2) Bias due to deviations from intended interventions; (3) Bias arising from missing outcome data; (4) Bias in the measurement of outcome; and (5) Bias in the selection of results. The risk of bias for each included study was assessed by two independent investigators. Any disagreements were settled by a third investigator.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was conducted on the studies, which were extracted according to the guidelines from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis group. We calculated the mean difference (MD) along with the 95% confidence interval (CI) to compare the effect of drugs on continuous outcome variables. For categorical outcomes, we calculated the hazard ratio with a 95%CI. A random effect model for meta-analysis was used because some degree of clinical and methodological heterogeneity was expected across the included studies (e.g., variation in patient populations, baseline characteristics, dosages, and follow-up durations). This approach provides a more conservative and generalizable estimate of the pooled effect, acknowledging that the true effect size may vary between studies rather than assuming a single common effect[22,23]. A random effect model for meta-analysis was used, and between-study heterogeneity was assessed using χ2 and I2 statistics. The statistical heterogeneity values of < 50%, 50%-75%, and > 75% were considered as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. Higher values of I2 and the χ2 statistic signified increasing levels of inconsistency between studies, and P < 0.001 was considered to provide evidence of significant heterogeneity. Statistical analysis was performed using the “meta” package of R-studio.

RESULTS

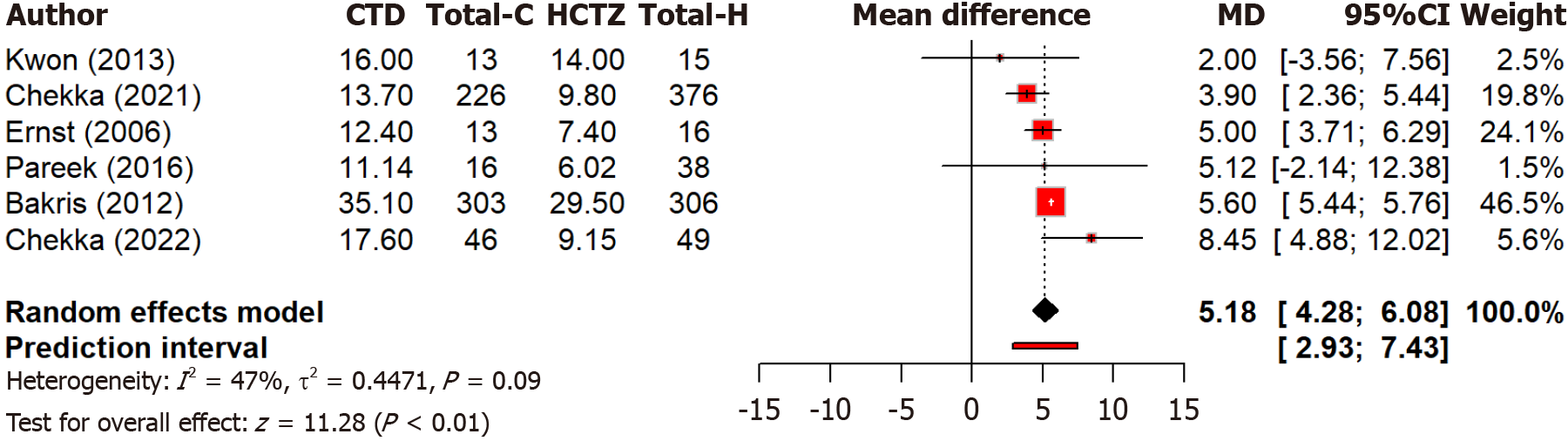

Our meta-analysis includes 11 studies, out of which six studies compare the reductions in systolic blood pressure between two drugs, chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide. Notably, it found that chlorthalidone leads to a significant (P < 0.0001) reduction in systolic blood pressure compared to hydrochlorothiazide, with a MD of 5.18 mmHg (95%CI: 4.28-6.08) (Figure 2). The tests for overall effects were strongly significant (P < 0.0001). Moderate heterogeneity is observed (I2 = 47.3%), although the between-study variance is low.

Figure 2 Forest plot comparing the effect of chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide on systolic blood pressure reduction.

CTD: Chlorthidone; HCTZ: Hydrochlorthiazide.

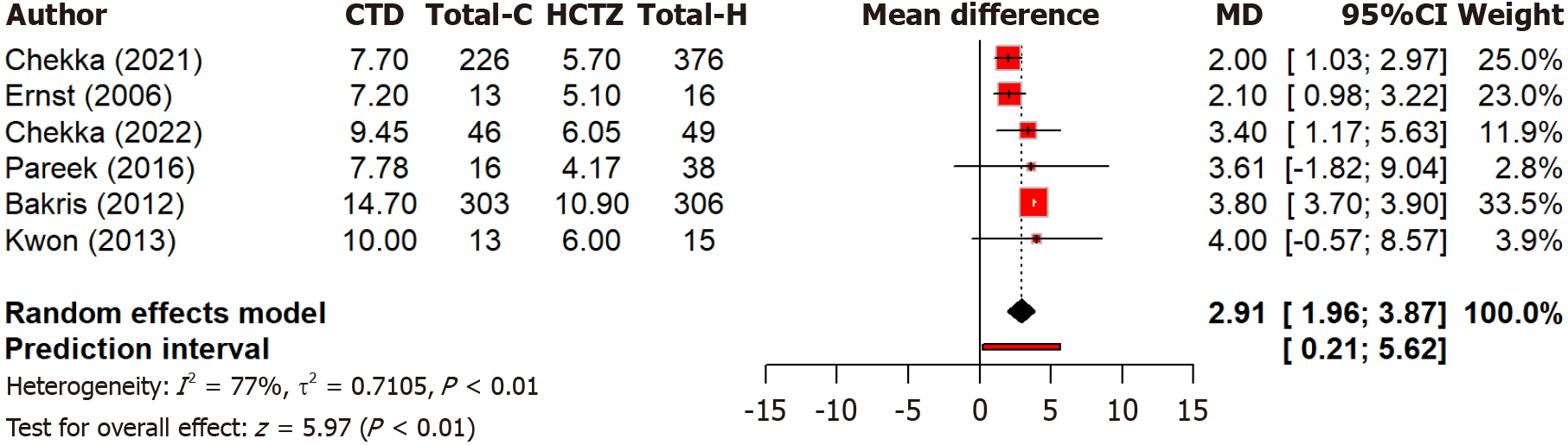

Moreover, a pooled analysis of six studies found that chlorthalidone led to a significantly (P < 0.0001) greater reduction in diastolic blood pressure compared to hydrochlorothiazide with a MD of 2.91 mmHg (95%CI: 1.96-3.87) (Figure 3). The overall effect was statistically significant (P < 0.0001). However, high heterogeneity is observed (I2 = 77.1%) across studies. This may reflect differences in study design, population characteristics, and dosing regimens. In the diastolic blood pressure analysis, high heterogeneity (I2 = 77.1%) may reflect differences in patient populations (e.g., race, baseline blood pressure), dosing regimens, and study designs.

Figure 3 Forest plot comparing the effect of chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide on diastolic blood pressure reduction.

CTD: Chlorthidone; HCTZ: Hydrochlorthiazide.

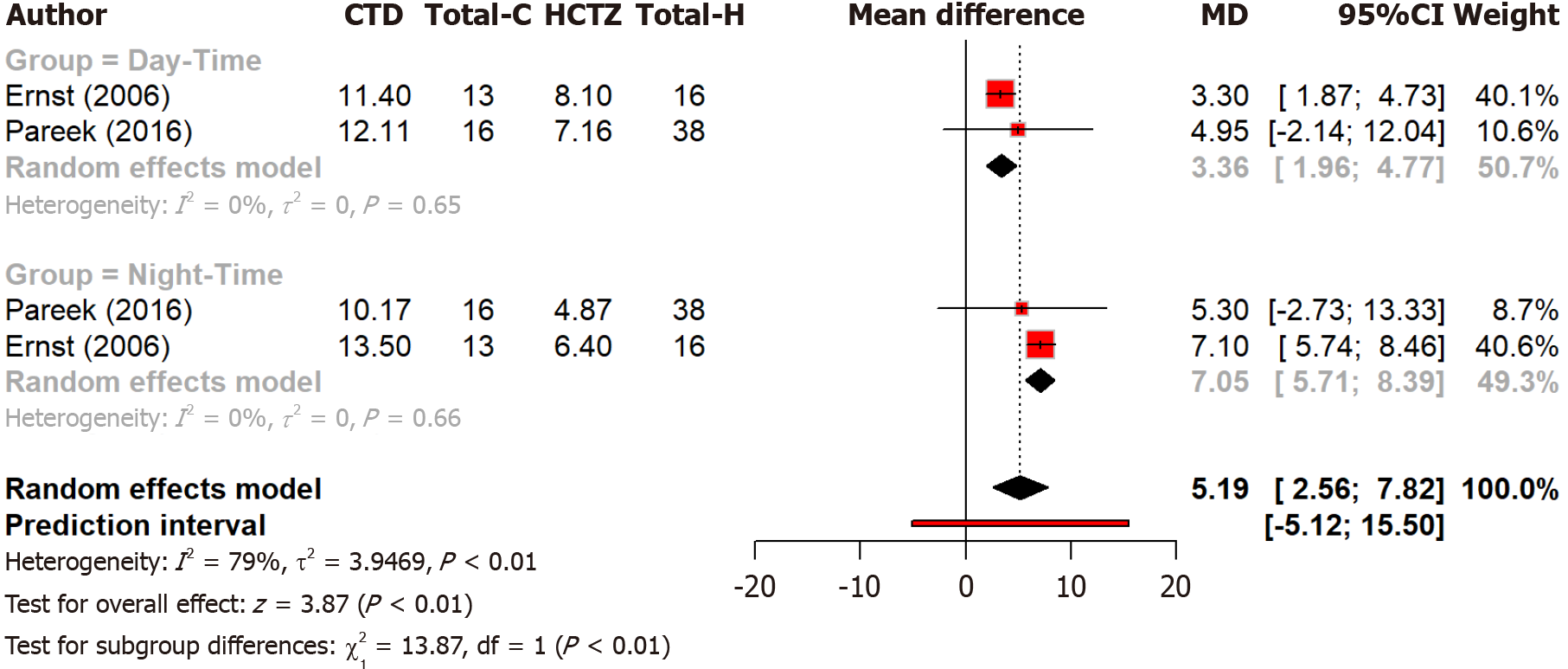

Analysis of two studies found that chlorthalidone’s lead to significantly greater reductions in overall blood pressure compared to hydrochlorothiazide’s (P = 0.0001). The reduction was greater at night than during the day, with subgroup differences being statistically significant (P = 0.0002). These findings suggest that chlorthalidone has a stronger blood pressure-lowering effect at night (Figure 4). Overall heterogeneity was high (I2 = 79%), while daytime and nighttime subgroups showed no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%), indicating consistent results within each subgroup.

Figure 4 Forest plot comparing the effect of chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide on day and nighttime blood pressure control.

CTD: Chlorthidone; HCTZ: Hydrochlorthiazide.

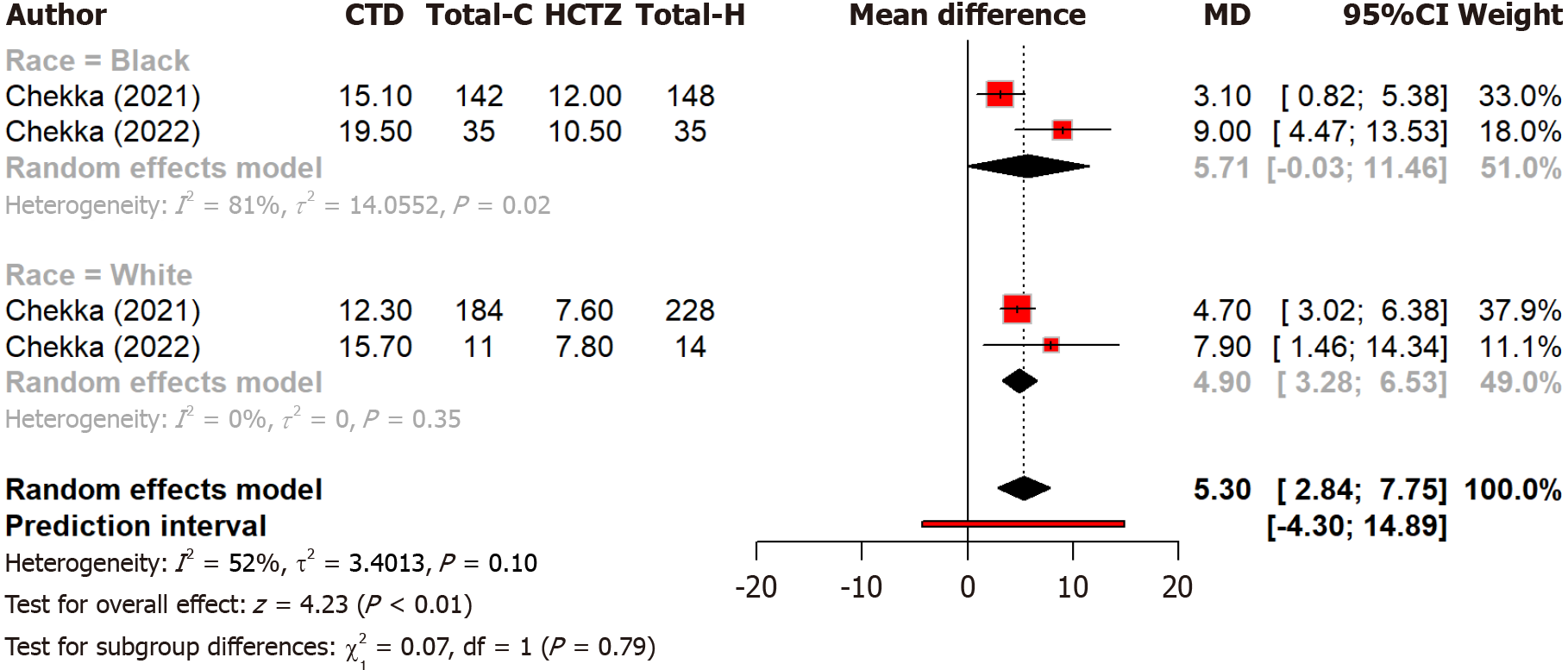

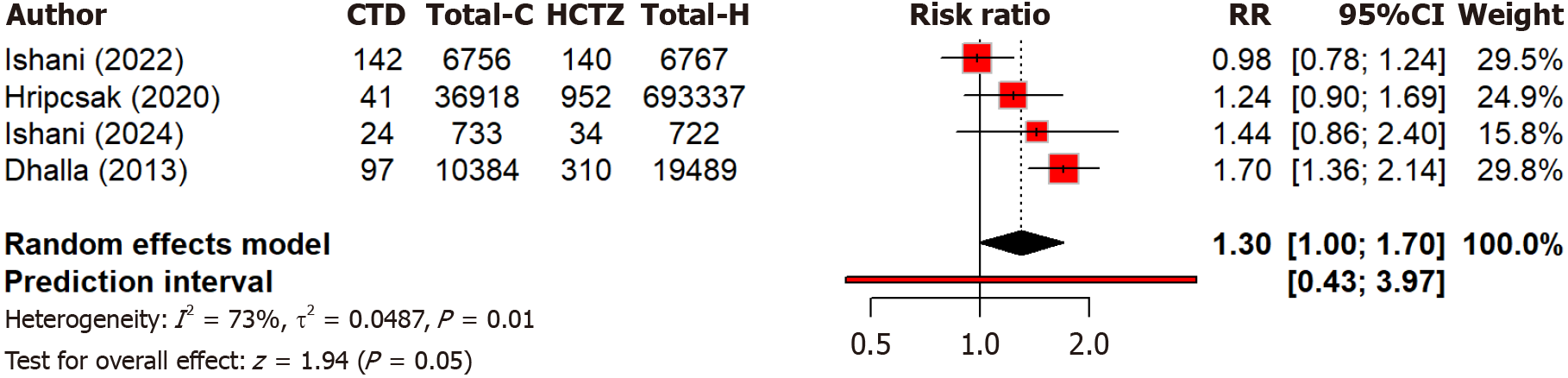

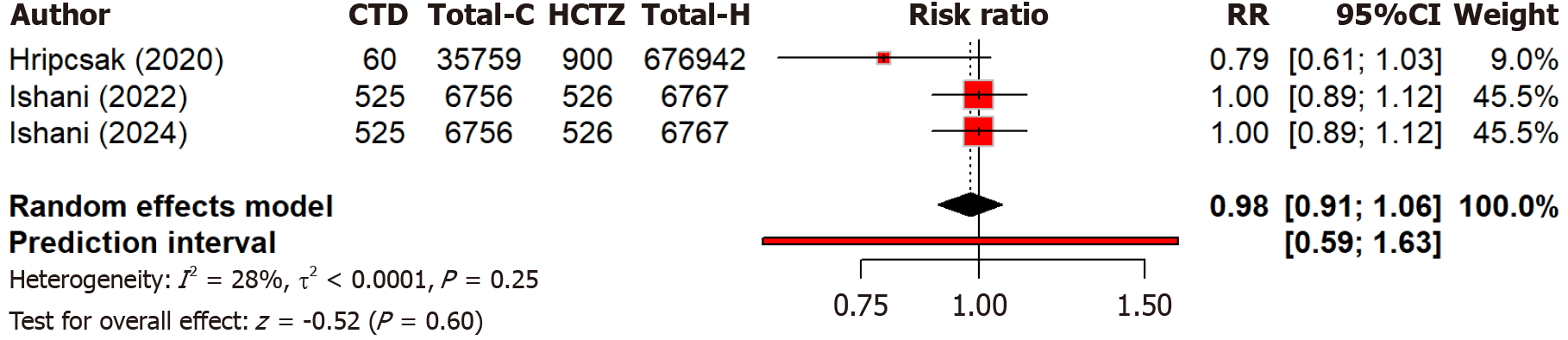

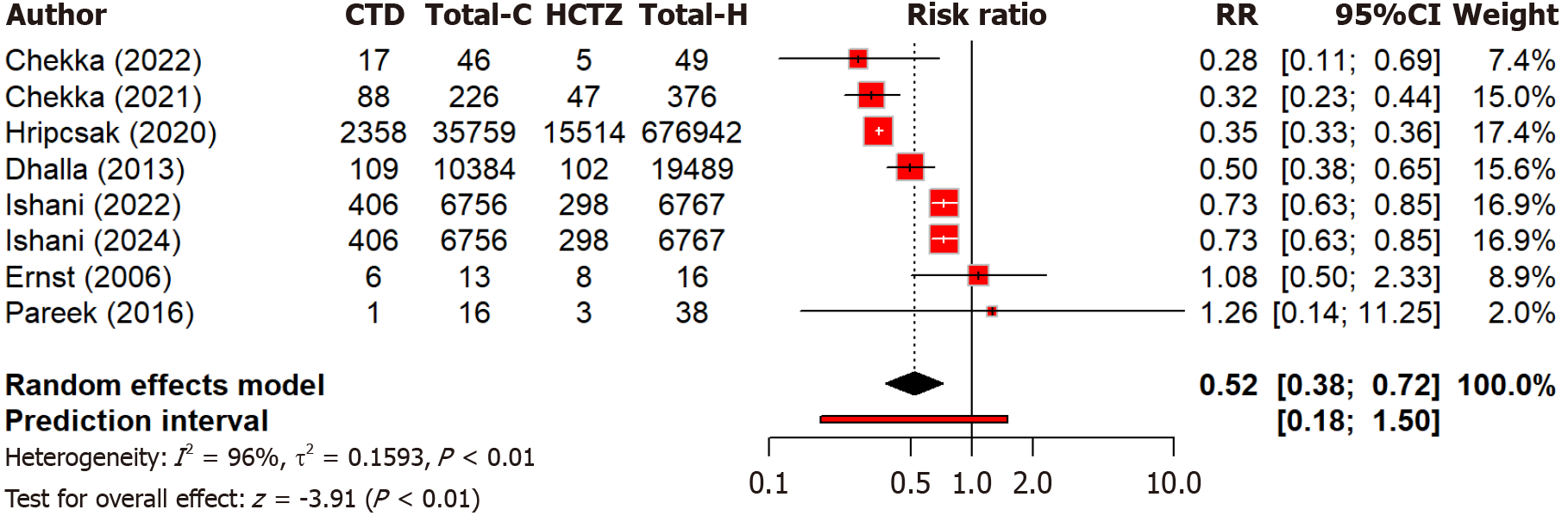

Two studies compare the effect of chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide on blood pressure control among different races. Notably, black patients showed more blood pressure reduction (MD: 5.71 mmHg) as compared to black patients with chlorthalidone than with hydrochlorothiazide (Figure 5). The subgroup difference was not significant (Q = 0.07, P = 0.791). Overall heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 52.3%). Four studies compared the risk of MI between two groups and found that hydrochlorothiazide was associated with a 30% higher risk of MI compared to chlorthalidone [relative risk (RR): 1.30, 95%CI: 1.00-1.70] but non-significant (P = 0.052) (Figure 6). Moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 73.4%) indicated variability across studies. Regarding heart failure, three studies found no significant (P = 0.60) difference in heart failure and hospitalization risk between chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide (RR: 0.98, 95%CI: 0.91-1.06) (Figure 7). Low heterogeneity (I2 = 28.2%) indicated minimal variability across studies. This suggests both drugs are equally safe regarding heart failure risk, with no strong evidence favoring one over the other based on this outcome alone. Eight studies found that hydrochlorothiazide had a significantly (P < 0.0001) lower risk of hypokalemia compared to chlorthalidone (RR: 0.52, 95%CI: 0.38-0.72), indicating a 52% lower risk with hydrochlorothiazide (Figure 8). However, heterogeneity (I2 = 96.2%) is very high across studies. This can again be attributed to discrepancies between the study design, population characteristics, and varying dosages.

Figure 5 Forest plot comparing the effect of chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide on blood pressure control among different races.

CTD: Chlorthidone; HCTZ: Hydrochlorthiazide.

Figure 6 Forest plot comparing the risk of myocardial infarction between the chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide group.

CTD: Chlorthidone; HCTZ: Hydrochlorthiazide; RR: Relative risk.

Figure 7 Forest plot comparing the risk of heart failure and hospitalization between the chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide groups.

CTD: Chlorthidone; HCTZ: Hydrochlorthiazide; RR: Relative risk.

Figure 8 Forest plot comparing the risk of hypokalemia between the chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide groups.

CTD: Chlorthidone; HCTZ: Hydrochlorthiazide; RR: Relative risk.

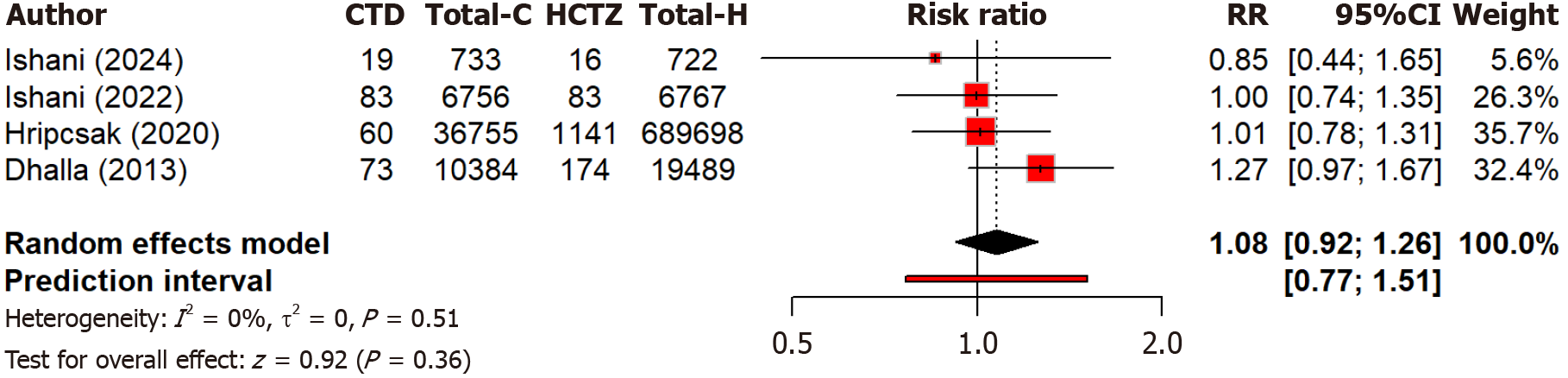

There is no significant difference (P = 0.36) in stroke risk between chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide (RR: 1.08, 95%CI: 0.92-1.26) as calculated by four studies. No heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%) indicated consistent findings across studies (Figure 9). This suggests both drugs have similar safety profiles regarding stroke risks, with no preference for stroke prevention based on current evidence. In the hypokalemia outcome (I2 = 96.2%), variability likely stems from inconsistent definitions of hypokalemia across studies and different follow-up durations.

Figure 9 Forest plot comparing the risk of stroke between the chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide groups.

CTD: Chlorthidone; HCTZ: Hydrochlorthiazide; RR: Relative risk.

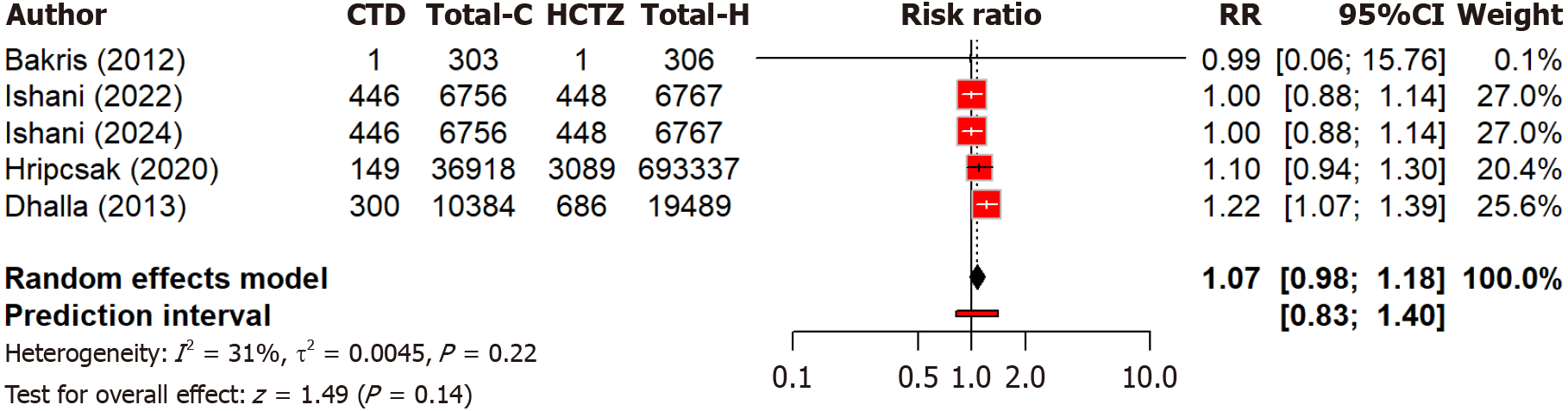

Regarding mortality, five studies found no significant (P = 0.14) difference in all-cause mortality risk between chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide (RR: 1.07, 95%CI: 0.98-1.18). Low heterogeneity (I2 = 30.8%) suggested some variability (Figure 10). These findings suggest that both drugs have comparable safety profiles in terms of overall mortality, with no clear preference evident based on current evidence.

Figure 10 Forest plot comparing the risk of all-cause mortality between chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide groups.

CTD: Chlorthidone; HCTZ: Hydrochlorthiazide; RR: Relative risk.

DISCUSSION

This meta-analysis highlighted that chlorthalidone had a greater reduction in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure in comparison to hydrochlorothiazide. Specifically, chlorthalidone had a MD of 5.18 mmHg (95%CI: 4.28-6.08) in systolic and 2.91 mmHg (95%CI: 1.96-3.87) in diastolic blood pressure. This finding corroborates with previous studies, that have shown chlorthalidone to have a greater impact in the reduction of blood pressure compared to other thiazide diuretics such as hydrochlorothiazide[10,15,24]. Although the mean blood pressure reduction was modest, the literature has evidenced that even small reductions of 5 mmHg in blood pressure significantly reduced the major adverse cardiovascular events, by a 14% lower risk of stroke and 9%-11% lower risk of ischemic heart disease[25]. Hence, when a pharmacological thiazide-diuretic class is selected by physicians for hypertension management, a preference of chlorthalidone is preferrable in the prevention of future cardiovascular events in patients.

The potential mechanism of the enhanced efficacy observed by chlorthalidone, may be attributed to its greater half-life in comparison to hydrochlorothiazide[8,26]. This allows for a longer antihypertensive effect in patients, in line with the literature, that has reported a prolonged blood pressure control by chlorthalidone. Therefore, it is more suitable for patients requiring 24-hour control[8,27,28]. Similarly, our nocturnal and diurnal analysis of blood pressure regulation revealed that chlorthalidone is superior to hydrochlorothiazide in regulating nocturnal blood pressure, which has been evidenced to significantly reduce cardiovascular risk. This finding highlights the importance of physicians to understand circadian rhythm in the treatment of hypertension, as adequate nocturnal blood pressure control is a method to lower the risk of cardiovascular events in patients[29].

Although our race-stratified subgroup analysis did not demonstrate statistically significant differences between chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide, these findings deserve careful interpretation. The subgroup with race information included few studies and participants, producing limited statistical power and wide prediction intervals despite an apparently greater point estimate of blood-pressure reduction in some groups; consequently, a true difference could be missed[13]. Biological factors - such as a higher prevalence of salt-sensitive, low-renin hypertension among many black patients and pharmacologic differences (chlorthalidone’s longer half-life and duration of action) plausibly modify response and adverse-effect profiles and may explain the direction of effects we observed. However, large trials and recent pooled analyses have reached mixed conclusions: Some pooled analyses report greater blood pressure lowering with chlorthalidone but more metabolic adverse effects in certain groups[13,30], while randomized outcome trials have not shown clear superiority for major cardiovascular endpoints[15]. In addition, under-representation of minority participants and inconsistent race reporting in primary studies limit generalizability and increase the risk of residual confounding[13,31]. Therefore, our subgroup results should be viewed as hypothesis-generating rather than definitive; future research should prioritize adequately powered, race-stratified analyses (or individual-participant data meta-analyses) and transparent race/ethnicity reporting to determine whether treatment choice between chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide should be tailored for specific populations.

Our meta-analysis highlighted that the relative risk (RR: 1.30, 95%CI: 1.00-1.70) of MI was higher in the hydrochlorothiazide group compared to the chlorthalidone group, but the finding was not significant (P = 0.052). This suggests that patients prescribed with hydrochlorothiazide may be at an increased cardiovascular risk, which could be explained by the reduced reduction in blood pressure compared to chlorthalidone, hence an increased risk of MI[32]. Similarly, chlorthalidone has been reported to reduce the risk of recurrent MI compared to hydrochlorothiazide, however further studies are required to evaluate the relationship between different thiazide diuretic agents and the risk of MI in different patient subgroups[33]. With regard to the risk of stroke, our findings were aligned with the literature, that both chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide offer equal protection against the risk of stroke. Hence, clinicians can support patients in their thiazide diuretics choice of either group, while reducing the risk of stroke in patients[10].

In relation to patient safety, one major side effect of thiazide diuretics is the increased risk of electrolyte imbalances[34]. Our review, revealed that hydrochlorothiazide has a significantly (P < 0.0001) lower risk of hypokalemia compared to chlorthalidone (RR: 0.52, 95%CI: 0.38-0.72). This is consistent with the pharmacological distinctions between the two medications, as chlorthalidone greater potency and duration of action may result in the greater excretion of potassium ions[35]. Hence, clinicians would require the close monitoring of potassium levels, particularly if they are to prescribe chlorthalidone, in order to mitigate this risk. Thus, patients who are at risk of hypokalemia are evidence by our study to have a lower risk of hypokalemia with the use of hydrochlorothiazide. It must be noted that clinicians must be careful with the prescription of any thiazide diuretic with consistent blood electrolyte testing for these patients. Interestingly, our findings did not show any difference in the risk of hospitalization or heart failure between hydrochlorothiazide and chlorthalidone (RR: 0.98, 95%CI: 0.91-1.06). This was in confirmation with previous studies, which mentioned that neither hydrochlorothiazide nor chlorthalidone was associated with a heightened risk of heart failure in patients with hypertension[36,37].

Limitations

Several limitations of this meta-analysis need to be acknowledged. Considerable methodological heterogeneity was observed in the included studies. The protocol and equipment of clinical outcomes: Blood pressure recordings, particularly in diastolic blood pressure and the analysis of hypokalemia may result in result bias and impact reliability for results. This could be mitigated by the inclusion of standardized protocols in clinical practice, which would improve the generalizability of the results. Variation existed in the definition of specific outcomes, such as MI, stroke, and hypokalemia could have introduced outcome misclassification bias. as the definitions of MI varied (e.g., some trials used enzymatic/electrocardiogram changes, while others required hospitalization). Stroke definitions ranged from clinical diagnosis to imaging-confirmed events. Such variation likely introduced outcome misclassification bias and contributed to heterogeneity in pooled results. The inclusion of observational studies results in limitations of generalizability, as patients selected may result in selection bias and heterogeneity of patient characteristics, misrepresenting specific population groups such as ethnicities. Additionally, though the meta-analysis provides significant evidence of the relative efficacy of medicine agents, the lack of differences between stroke and death hazards indicate that studies may have been underpowered and of a short duration, that would be improved by a large randomized controlled trials that evaluated the long-term impact of the different thiazide diuretic medication. Furthermore, scientific studies examining the implications of these medicines in different racial and ethnic categories would help illustrate likely subgroup contrasts with respect to treatment effect.

CONCLUSION

This meta-analysis shows strong evidence that chlorthalidone is more effective than hydrochlorothiazide in reducing both systolic and diastolic blood pressure. The two drugs share comparable safety profiles in terms of large cardiovascular events like stroke and death, but chlorthalidone may be linked to a higher risk of hypokalemia. Our findings highlight the importance of individualizing treatment to consider the differences in drug efficacy and safety profiles. Future studies must correct the shortcomings in our analysis, including the high heterogeneity reported in some outcomes and the need for long-term data on hard cardiovascular events.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American College of Chest Physician.

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade A

Novelty: Grade A

Creativity or Innovation: Grade A

Scientific Significance: Grade A

P-Reviewer: Elbarbary MA, Assistant Professor, Egypt S-Editor: Hu XY L-Editor: A P-Editor: Lei YY